Safed El Battikh on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Safed (), also known as Tzfat (), is a city in the Northern District of  Safed has a large

Safed has a large

accessed 9 December 2016 Safed is mentioned in the

''Farewell Espana: The World of the Sephardim Remembered,''

Random House, 2013 p. 190. In the estimation of modern historian Havré Barbé, the ''castellany'' of Safed comprised approximately . According to Barbé, its western boundary straddled the domains of Acre, including the fief of St. George de la Beyne, which included

152

/ref> Saladin ultimately allowed its residents to relocate to Tyre. He granted Safed and Tiberias as an ''

Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

. Located at an elevation of up to , Safed is the highest city in the Galilee

Galilee (; ; ; ) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon consisting of two parts: the Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and the Lower Galilee (, ; , ).

''Galilee'' encompasses the area north of the Mount Carmel-Mount Gilboa ridge and ...

and in Israel.

Safed has been identified with (), a fortified town in the Upper Galilee

The Upper Galilee (, ''HaGalil Ha'Elyon''; , ''Al Jaleel Al A'alaa'') is a geographical region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Part of the larger Galilee region, it is characterized by its higher elevations and mountainous terra ...

mentioned in the writings of the Roman Jewish historian Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; , ; ), born Yosef ben Mattityahu (), was a Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing '' The Jewish War'', he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Roman province of Judea—to a father of pr ...

. The Jerusalem Talmud

The Jerusalem Talmud (, often for short) or Palestinian Talmud, also known as the Talmud of the Land of Israel, is a collection of rabbinic notes on the second-century Jewish oral tradition known as the Mishnah. Naming this version of the Talm ...

mentions Safed as one of five elevated spots where fires were lit to announce the New Moon

In astronomy, the new moon is the first lunar phase, when the Moon and Sun have the same ecliptic longitude. At this phase, the lunar disk is not visible to the naked eye, except when it is silhouetted against the Sun during a solar eclipse. ...

and festivals during the Second Temple period

The Second Temple period or post-exilic period in Jewish history denotes the approximately 600 years (516 BCE – 70 CE) during which the Second Temple stood in the city of Jerusalem. It began with the return to Zion and subsequent reconstructio ...

. Safed attained local prominence under the Crusaders

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding ...

, who built a large fortress there in 1168. It was conquered by Saladin

Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known as Saladin, was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from a Kurdish family, he was the first sultan of both Egypt and Syria. An important figure of the Third Crusade, h ...

20 years later, and demolished by his grandnephew al-Mu'azzam Isa

() (1176 – 1227) was the Ayyubid Kurdish emir of Damascus from 1218 to 1227. The son of Sultan al-Adil I and nephew of Saladin, founder of the dynasty, al-Mu'azzam was installed by his father as governor of Damascus in 1198 or 1200. After his f ...

in 1219. After reverting to the Crusaders in a treaty in 1240, a larger fortress was erected, which was expanded and reinforced in 1268 by the Mamluk

Mamluk or Mamaluk (; (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural); translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave") were non-Arab, ethnically diverse (mostly Turkic, Caucasian, Eastern and Southeastern European) enslaved mercenaries, slave-so ...

sultan Baybars

Al-Malik al-Zahir Rukn al-Din Baybars al-Bunduqdari (; 1223/1228 – 1 July 1277), commonly known as Baibars or Baybars () and nicknamed Abu al-Futuh (, ), was the fourth Mamluk sultan of Egypt and Syria, of Turkic Kipchak origin, in the Ba ...

, who developed Safed into a major town and the capital of a new province spanning the Galilee. After a century of general decline, the stability brought by the Ottoman conquest in 1517 ushered in nearly a century of growth and prosperity in Safed, during which time Jewish immigrants from across Europe developed the city into a center for wool and textile production and the mystical Kabbalah

Kabbalah or Qabalah ( ; , ; ) is an esoteric method, discipline and school of thought in Jewish mysticism. It forms the foundation of Mysticism, mystical religious interpretations within Judaism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal ...

movement. It became known as one of the Four Holy Cities

In Judaism, the "Four Holy Cities" are Jerusalem, Hebron, Tiberias, and Safed. Revered for their significance to Jewish history, they began to again serve as major centres of Jewish life after the Ottoman conquest of the Levant.

According to '' ...

of Judaism. As the capital of the Safad Sanjak

Safed Sanjak (; ) was a '' sanjak'' (district) of Damascus Eyalet ( Ottoman province of Damascus) in 1517–1660, after which it became part of the Sidon Eyalet (Ottoman province of Sidon). The sanjak was centered in Safed and spanned the Galil ...

, it was the main population center of the Galilee, with large Muslim and Jewish communities. Besides during the fortunate governorship of Fakhr al-Din II

Fakhr al-Din Ma'n (; 6 August 1572 13 April 1635), commonly known as Fakhr al-Din II or Fakhreddine II (), was the paramount Druze emir of Mount Lebanon from the Ma'n dynasty, an Ottoman Empire, Ottoman sanjak-bey, governor of Sidon-Beirut Sanj ...

in the early 17th century, the city underwent a general decline and by the mid-18th century was eclipsed by Acre

The acre ( ) is a Unit of measurement, unit of land area used in the Imperial units, British imperial and the United States customary units#Area, United States customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one Chain (unit), ch ...

. Its Jewish residents were targeted in Druze

The Druze ( ; , ' or ', , '), who Endonym and exonym, call themselves al-Muwaḥḥidūn (), are an Arabs, Arab Eastern esotericism, esoteric Religious denomination, religious group from West Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic ...

and local Muslim raids in the 1830s, and many perished in an earthquake

An earthquakealso called a quake, tremor, or tembloris the shaking of the Earth's surface resulting from a sudden release of energy in the lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from those so weak they ...

in that same decade – through the philanthropy of Moses Montefiore

Sir Moses Haim Montefiore, 1st Baronet, (24 October 1784 – 28 July 1885) was a British financier and banker, activist, Philanthropy, philanthropist and Sheriffs of the City of London, Sheriff of London. Born to an History ...

, its Jewish synagogues and homes were rebuilt.

Safed's population reached 24,000 toward the end of the 19th century; it was a mixed city

In Israel, the mixed cities (, ) or mixed towns are the eight cities with a significant number of both Israeli Jews and Arab citizens of Israel, Israeli Arabs. The eight mixed Jewish-Arab cities, defined by the Israel Central Bureau of Statisti ...

, divided roughly equally between Jews and Muslims with a small Christian community. Its Muslim merchants played a key role as middlemen in the grain trade

The grain trade refers to the local and international trade in cereals such as wheat, barley, maize, rice, and other food grains. Grain is an important trade item because it is easily stored and transported with limited spoilage, unlike other agri ...

between the local farmers and the traders of Acre, while the Ottomans promoted the city as a center of Sunni

Sunni Islam is the largest branch of Islam and the largest religious denomination in the world. It holds that Muhammad did not appoint any successor and that his closest companion Abu Bakr () rightfully succeeded him as the caliph of the Mu ...

jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, also known as theory of law or philosophy of law, is the examination in a general perspective of what law is and what it ought to be. It investigates issues such as the definition of law; legal validity; legal norms and values ...

. Safed's conditions improved considerably in the late 19th century, a municipal council was established along with a number of banks, though the city's jurisdiction was limited to the Upper Galilee. By 1922, Safed's population had dropped to around 8,700, roughly 60% Muslim, 33% Jewish and the remainder Christians. Amid rising ethnic tension throughout Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine was a British Empire, British geopolitical entity that existed between 1920 and 1948 in the Palestine (region), region of Palestine, and after 1922, under the terms of the League of Nations's Mandate for Palestine.

After ...

, Safed's Jews were attacked in an Arab riot in 1929. The city's population had risen to 13,700 by 1948, overwhelmingly Arab, though the city was proposed to be part of a Jewish state in the 1947 UN Partition Plan

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a proposal by the United Nations to partition Mandatory Palestine at the end of the British Mandate. Drafted by the U.N. Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) on 3 September 1947, the Pl ...

. During the 1948 war

The 1948 Palestine war was fought in the territory of what had been, at the start of the war, British-ruled Mandatory Palestine. During the war, the British withdrew from Palestine, Zionist forces conquered territory and established the Stat ...

, Arab factions attacked and besieged the Jewish quarter which held out until Jewish paramilitary forces captured the city after heavy fighting, precipitating British forces to withdraw. Most of the city's predominantly Palestinian-Arab population fled or were expelled as a result of attacks by Jewish forces and the nearby Ein al-Zeitun massacre

The Ein al Zeitun massacre occurred on May 1, 1948, during the 1948 Palestine war, when forces of the Palmach attacked the Palestinian village of Ein al-Zeitun, then part of the British Mandatory Palestine, Mandate for Palestine. 70+ villagers wer ...

, and were not allowed to return after the war, such that today the city has an almost exclusively Jewish population. That year, the city became part of the then-newly established state of Israel.

Haredi

Haredi Judaism (, ) is a branch of Orthodox Judaism that is characterized by its strict interpretation of religious sources and its accepted (Jewish law) and traditions, in opposition to more accommodating values and practices. Its members are ...

community and remains a center for Jewish religious studies. Safed today hosts the Ziv Hospital as well as the Zefat Academic College. Safed is a major subject in Israeli art, it hosts an Artists' Quarter

The Artists' Quarter (a.k.a. the AQ) was a well-known musician-owned and operated jazz club in the Minneapolis-Saint Paul, Twin Cities.

History

The club opened in the early 1970s in Minneapolis, Minnesota at 26th Street and Nicollet Avenue South. ...

. Several prominent art movements played a role in the city, most notably the École de Paris

The School of Paris (, ) refers to the French and émigré artists who worked in Paris in the first half of the 20th century.

The School of Paris was not a single art movement or institution, but refers to the importance of Paris as a centre o ...

. However the Artists' quarter

The Artists' Quarter (a.k.a. the AQ) was a well-known musician-owned and operated jazz club in the Minneapolis-Saint Paul, Twin Cities.

History

The club opened in the early 1970s in Minneapolis, Minnesota at 26th Street and Nicollet Avenue South. ...

has declined since its golden age in the second half of the 20th century. Due to its high elevation, the city has warm summers and cold, often snowy winters. Its mild climate and scenic views have made Safed a popular holiday resort frequented by Israelis and foreign visitors. In it had a population of .

Biblical reference

Legend has it that Safed was founded by a son ofNoah

Noah (; , also Noach) appears as the last of the Antediluvian Patriarchs (Bible), patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5–9), the Quran and Baháʼí literature, ...

after the Great Flood

A flood myth or a deluge myth is a myth in which a great flood, usually sent by a deity or deities, destroys civilization, often in an act of divine retribution. Parallels are often drawn between the flood waters of these myths and the primeva ...

. According to the Book of Judges

The Book of Judges is the seventh book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. In the narrative of the Hebrew Bible, it covers the time between the conquest described in the Book of Joshua and the establishment of a kingdom in the ...

(), the area where Safed is located was assigned to the tribe of Naphtali

The Tribe of Naphtali () was one of the northernmost of the twelve tribes of Israel. It is one of the ten lost tribes.

Biblical narratives

In the biblical account, following the completion of the conquest of Canaan by the Israelites, Joshua a ...

.

It has been suggested that Jesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

' assertion that "a city that is set on a hill cannot be hidden" referred to Safed.

History

Antiquity

Safed has been identified with ''Sepph,'' a fortified town in theUpper Galilee

The Upper Galilee (, ''HaGalil Ha'Elyon''; , ''Al Jaleel Al A'alaa'') is a geographical region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Part of the larger Galilee region, it is characterized by its higher elevations and mountainous terra ...

mentioned in the writings of the Roman-Jewish historian Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; , ; ), born Yosef ben Mattityahu (), was a Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing '' The Jewish War'', he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Roman province of Judea—to a father of pr ...

.Geography of Israel: Safedaccessed 9 December 2016 Safed is mentioned in the

Jerusalem Talmud

The Jerusalem Talmud (, often for short) or Palestinian Talmud, also known as the Talmud of the Land of Israel, is a collection of rabbinic notes on the second-century Jewish oral tradition known as the Mishnah. Naming this version of the Talm ...

as one of five elevated spots where fires were lit to announce the New Moon

In astronomy, the new moon is the first lunar phase, when the Moon and Sun have the same ecliptic longitude. At this phase, the lunar disk is not visible to the naked eye, except when it is silhouetted against the Sun during a solar eclipse. ...

and festivals during the Second Temple period

The Second Temple period or post-exilic period in Jewish history denotes the approximately 600 years (516 BCE – 70 CE) during which the Second Temple stood in the city of Jerusalem. It began with the return to Zion and subsequent reconstructio ...

.

Crusader era

Pre-Crusader village and tower

There is scarce information about Safed before theCrusader

Crusader or Crusaders may refer to:

Military

* Crusader, a participant in one of the Crusades

* Convair NB-36H Crusader, an experimental nuclear-powered bomber

* Crusader tank, a British cruiser tank of World War II

* Crusaders (guerrilla), a C ...

conquest.Drory 2004, p. 163. A document from the Cairo Geniza

The Cairo Geniza, alternatively spelled the Cairo Genizah, is a collection of some 400,000 Judaism, Jewish manuscript fragments and Fatimid Caliphate, Fatimid administrative documents that were kept in the ''genizah'' or storeroom of the Ben Ezra ...

, composed in 1034, mentions a transaction made in Tiberias in 1023 by a certain Jew, Musa ben Hiba ben Salmun with the ''nisba

The Arabic language, Arabic word nisba (; also transcribed as ''nisbah'' or ''nisbat'') may refer to:

* Arabic nouns and adjectives#Nisba, Nisba, a suffix used to form adjectives in Arabic grammar, or the adjective resulting from this formation

**c ...

'' (Arabic descriptive suffix) "al-Safati" (of Safed), indicating the presence of a Jewish community living alongside Muslims in Safed in the 11th century.Barbé 2016, p. 63. According to the Muslim historian Ibn Shaddad (d. 1285), at the beginning of the 12th century, a "flourishing village" beneath a tower called Burj Yatim had existed at the site of Safed on the eve of the Crusaders' capture of the area in 1101–1102 and that "nothing" about the village was mentioned in "the early Islamic history books".Ellenblum 2007, p. 179, note 15. Although Ibn Shaddad mistakenly attributes the tower's construction to the Knights Templar

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, mainly known as the Knights Templar, was a Military order (religious society), military order of the Catholic Church, Catholic faith, and one of the most important military ord ...

, the modern historian Ronnie Ellenblum

Ronnie Ellenblum (; born June 21, 1952, Haifa, Israel; died January 7, 2021, Jerusalem, Israel) was an Israeli professor at the department of geography at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and a member of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Human ...

asserts that the tower was likely built during the early Muslim period (mid-7th–11th centuries).

First Crusader period

The Frankish chroniclerWilliam of Tyre

William of Tyre (; 29 September 1186) was a Middle Ages, medieval prelate and chronicler. As Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Tyre, archbishop of Tyre, he is sometimes known as William II to distinguish him from his predecessor, William I of Tyr ...

noted the presence of a ''burgus

A ''burgus'' (Latin, plural ''burgi '') or ''turris'' ("tower") is a small fortified tower, tower-like castra, castrum of late antiquity, which was sometimes protected by an outwork and surrounding ditch (fortification), ditches. Timothy Da ...

'' (tower) in Safed, which he called "Castrum Saphet" or "Sephet", in 1157.Ellenblum 2007, p. 179, note 16. Safed was the seat of a ''castellan

A castellan, or constable, was the governor of a castle in medieval Europe. Its surrounding territory was referred to as the castellany. The word stems from . A castellan was almost always male, but could occasionally be female, as when, in 1 ...

y'' (area governed by a castle) by at least 1165, when its ''castellan'' (appointed castle governor) was Fulk, constable of Tiberias

Tiberias ( ; , ; ) is a city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee in northern Israel. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's Four Holy Cities, along with Jerusalem, Heb ...

. The castle of Safed was purchased from Fulk by King Amalric of Jerusalem

Amalric (; 113611 July 1174), formerly known in historiography as , was the king of Jerusalem from 1163 until his death. He was, in the opinion of his Muslim adversaries, the bravest and cleverest of the crusader kings.

Amalric was the younger ...

in 1168. He subsequently reinforced the castle and transferred it to the Templars in the same year. Theoderich the Monk, describing his visit to the area in 1172, noted that the expanded fortification of the castle of Safed was meant to check the raids of the Turks (the Turkic Zengid dynasty

The Zengid or Zangid dynasty, also referred to as the Atabegate of Mosul, Aleppo and Damascus (Arabic: أتابكة الموصل وحلب ودمشق), or the Zengid State (Old Anatolian Turkish: , Modern Turkish: ; ) was initially an '' Atabegat ...

ruled the area east of the Kingdom). Testifying to the considerable expansion of the castle, the chronicler Jacques de Vitry

Jacques de Vitry (''Jacobus de Vitriaco'', 1160/70 – 1 May 1240) was a medieval France, French canon regular who was a noted theology, theologian and chronicler of his era.

He was elected Latin Catholic Diocese of Acre, bishop of Acre in 1 ...

(d. 1240) wrote that it was practically built anew. The remains of Fulk's castle can now be found under the citadel excavations, on a hill above the old city.Howard M. Sacha''Farewell Espana: The World of the Sephardim Remembered,''

Random House, 2013 p. 190. In the estimation of modern historian Havré Barbé, the ''castellany'' of Safed comprised approximately . According to Barbé, its western boundary straddled the domains of Acre, including the fief of St. George de la Beyne, which included

Sajur

Sajur (; ) is a Druze town ( local council) in the Galilee region of northern Israel, with an area of 3,000 dunams (3 km2). It achieved recognition as an independent local council in 1992. In it had a population of .

History

Sajur is iden ...

and Beit Jann

Bayt Jann (; ) is a Druze village on Mount Meron in northern Israel. At 940 meters above sea level, Bayt Jann is one of the highest inhabited locations in the country. In it had a population of .

Etymology

Guérin noted that the village was ...

, and the fief of Geoffrey le Tor, which included Akbara

Akbara () is an Arab village in the Israel, Israeli municipality of Safed, which included in 2010 more than 200 families.

It is 2.5 km south of Safed City. The village was rebuilt in 1977, close to the old village destroyed in 1948 during ...

and Hurfeish

Hurfeish (; ; lit. " milk thistle"Vilnay, 1964, p501/ref> or possibly from "snake" Palmer, 1881, p72/ref>) is a Druze town in the Northern District of Israel. In it had a population of .

History

The town is situated on an ancient site, where m ...

, and in the southwest ran north of Maghar and Sallama

Sallama (; ) is a Bedouin village in northern Israel. Located in the Galilee near the Tzalmon Stream, it falls under the jurisdiction of Misgav Regional Council. In its population was . The village was recognized by the state in 1976.

History

...

. Its northern boundary was marked by the Nahal Dishon (Wadi al-Hindaj) stream, its southern boundary was likely formed near Wadi al-Amud, separating it from the fief of Tiberias, while its eastern limits were the marshes of the Hula Valley

The Hula Valley () is a valley and fertile agricultural region in northern Israel with abundant fresh water that used to be Lake Hula before it was drained. It is a major stopover for birds migrating along the Great Rift Valley between Africa ...

and upper Jordan Valley. There were several Jewish communities in the ''castellany'' of Safed, as testified in the accounts of Jewish pilgrims and chroniclers between 1120 and 1293. Benjamin of Tudela

Benjamin of Tudela (), also known as Benjamin ben Jonah, was a medieval Jewish traveler who visited Europe, Asia, and Africa in the twelfth century. His vivid descriptions of western Asia preceded those of Marco Polo by a hundred years. With his ...

, who visited the town in 1170, does not record any Jews living in Safed proper.

Ayyubid interregnum

Safed was captured by theAyyubids

The Ayyubid dynasty (), also known as the Ayyubid Sultanate, was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni Muslim of Kurdish ori ...

led by Sultan Saladin

Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known as Saladin, was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from a Kurdish family, he was the first sultan of both Egypt and Syria. An important figure of the Third Crusade, h ...

in 1188 after a month-long siege, following the Battle of Hattin

The Battle of Hattin took place on 4 July 1187, between the Crusader states of the Levant and the forces of the Ayyubid sultan Saladin. It is also known as the Battle of the Horns of Hattin, due to the shape of the nearby extinct volcano of ...

in 1187.Sharon 2007, p152

/ref> Saladin ultimately allowed its residents to relocate to Tyre. He granted Safed and Tiberias as an ''

iqta

An iqta () and occasionally iqtaʿa () was an Islamic practice of farming out tax revenues yielded by land granted temporarily to army officials in place of a regular wage; it became common in the Muslim empire of the Caliphate. Iqta has been defi ...

'' (akin to a fief) to Sa'd al-Din Mas'ud ibn Mubarak (d. 1211), the son of his niece, after which it was bequeathed to Sa'd al-Din's son Ahmad.Drory 2004, p. 164. Samuel ben Samson

Samuel ben Samson (also Samuel ben Shimshon) was a rabbi who lived in France and made a pilgrimage to Palestine in 1210, visiting a number of villages and cities there, including Jerusalem. Amongst his companions were Jonathan ben David ha-Cohen, ...

, who visited the town in 1210, mentions the existence of a Jewish community of at least fifty there. He also noted that two Muslims guarded and maintained the cave tomb of a rabbi, Hanina ben Horqano, in Safed. The ''iqta'' of Safed was taken from the family of Sa'd al-Din by the Ayyubid emir of Damascus

Damascus ( , ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in the Levant region by population, largest city of Syria. It is the oldest capital in the world and, according to some, the fourth Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. Kno ...

, al-Mu'azzam Isa

() (1176 – 1227) was the Ayyubid Kurdish emir of Damascus from 1218 to 1227. The son of Sultan al-Adil I and nephew of Saladin, founder of the dynasty, al-Mu'azzam was installed by his father as governor of Damascus in 1198 or 1200. After his f ...

, in 1217.Luz 2014, p. 34. Two years later, during the Crusader siege of Damietta, al-Mu'azzam Isa had the Safed castle demolished to prevent its capture and reuse by potential future Crusaders.

Second Crusader period

As an outcome of the treaty negotiations between the Crusader leaderTheobald I of Navarre

Theobald I (, ; 30 May 1201 – 8 July 1253), also called the Troubadour and the Posthumous, was Count of Champagne (as Theobald IV) from birth and King of Navarre from 1234. He initiated the Barons' Crusade, was famous as a trouvère, and was the ...

and the Ayyubid al-Salih Ismail, Emir of Damascus

Al-Malik al-Salih Imad al-Din Ismail bin Saif al-Din Ahmad better known as al-Salih Ismail () was the Ayyubid sultan based in Damascus. He reigned twice, once in 1237 and then again from 1239 to 1245.

In 1237, al-Salih Ismail's brother,Abulafia a ...

, in 1240 Safed once again passed to Crusader control. Afterward, the Templars were tasked with rebuilding the Citadel of Safed

The Citadel of Safed is a now-defunct fortress castle situated on the peak of the mountain housing the modern city of Safed. Furthermore, fortifications existed during the late period of the Second Temple period, Second Temple as well as the Roma ...

, with efforts spearheaded by Benedict of Alignan, Bishop of Marseille

The Archdiocese of Marseille (Latin: ''Archidioecesis Massiliensis''; French: ''Archidiocèse de Marseille'') is a Latin Church ecclesiastical jurisdiction or archdiocese of the Catholic Church in France. The rebuilding is recorded in a short treatise, ''

The Ayyubids of Egypt had been supplanted by the

The Ayyubids of Egypt had been supplanted by the

xii

/ref> one of seven ''mamlakas'' (provinces), whose governors were typically appointed from The geographer

The geographer

The Ottomans conquered Mamluk Syria following their victory at the

The Ottomans conquered Mamluk Syria following their victory at the

pp. 95–96

/ref> In 1553/54, the population consisted of 1,121 Muslim households, 222 Muslim bachelors, 54 Muslim religious leaders, 716 Jewish households, 56 Jewish bachelors, and 9 disabled persons. At least in the 16th century, Safed was the only ''kasaba'' (city) in the sanjak and in 1555 was divided into nineteen ''mahallas'' (quarters), seven Muslim and twelve Jewish.Rhode 1979, p. 34. The total population of Safed rose from 926 households in 1525–26 to 1,931 households in 1567–1568. Among these, the Jewish population rose from a mere 233 households in 1525 to 945 households in 1567–1568.Petersen (2001), Gazetteer 6, s,v

Ṣafad

/ref> The Muslim quarters were Sawawin, located west of the fortress; Khandaq (the moat); Ghazzawiyah, which had likely been settled by Gazans; Jami' al-Ahmar (the Red Mosque), located south of the fortress and named for the local mosque; al-Akrad, which dated to the Middle Ages and continued to exist through the 19th century,Ebied and Young 1976, p. 7. and whose inhabitants mainly were

By the early part of the 17th century, Safed was a small town. In 1602, the paramount chief of the Druze in Mount Lebanon,

By the early part of the 17th century, Safed was a small town. In 1602, the paramount chief of the Druze in Mount Lebanon,

256

destroyed all fourteen of its synagogues and prompted the flight of 600

Ottoman rule was restored across the Levant in 1840. The Empire-wide

Ottoman rule was restored across the Levant in 1840. The Empire-wide  In 1878 the municipal council of Safed was established. In 1888 the Acre Sanjak, including the Safed Kaza, became part of the new province of

In 1878 the municipal council of Safed was established. In 1888 the Acre Sanjak, including the Safed Kaza, became part of the new province of

188

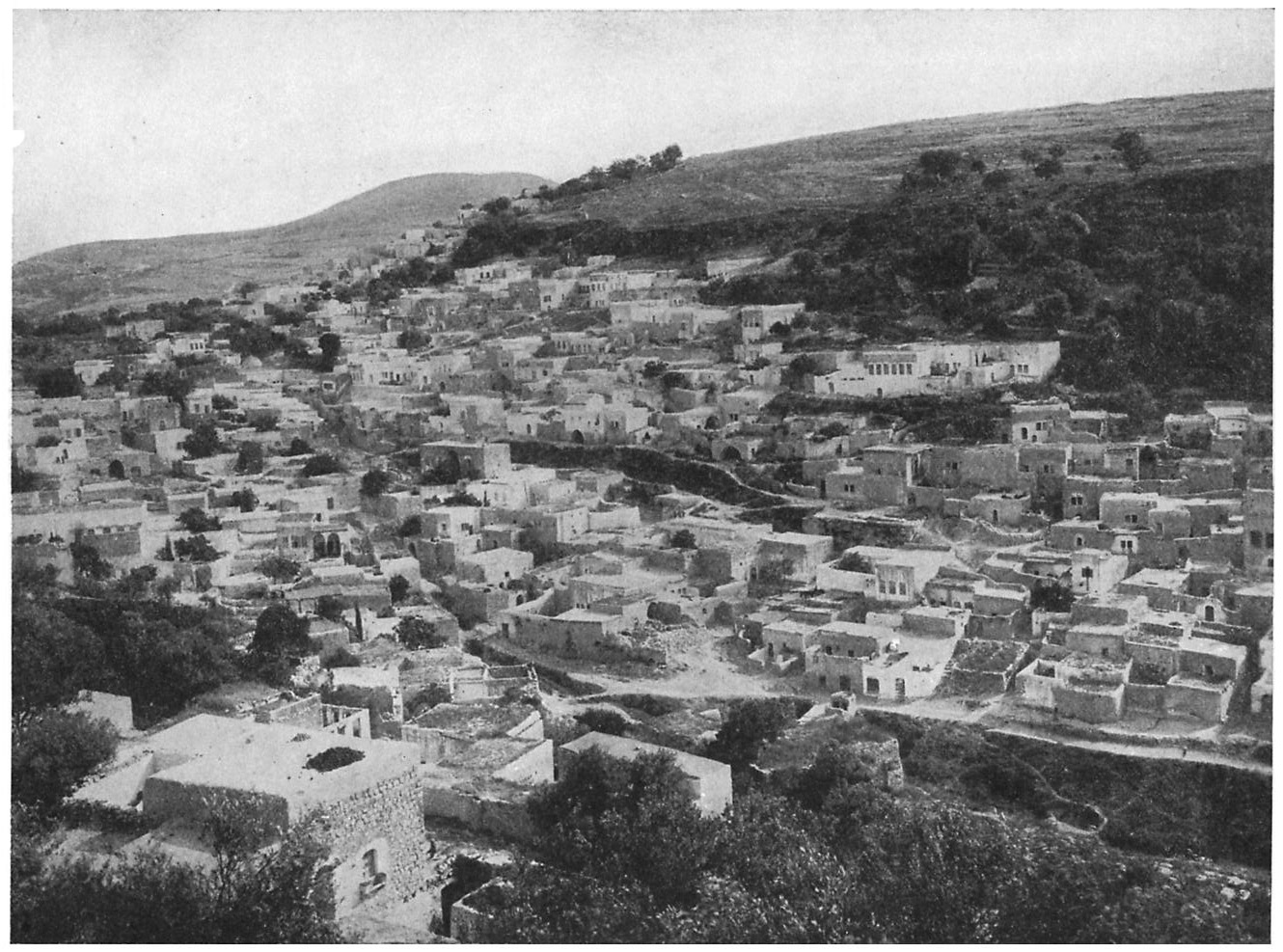

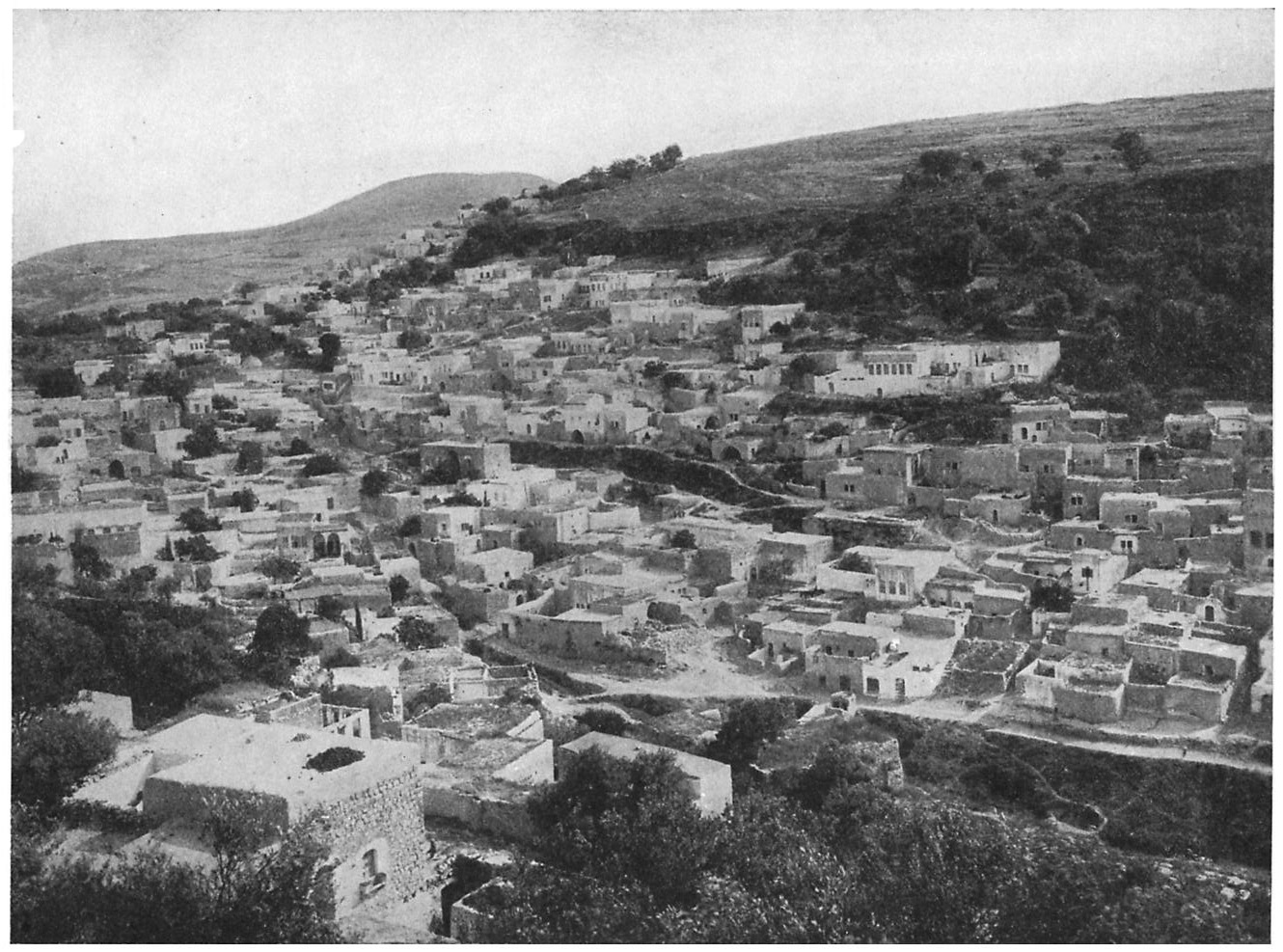

/ref> The entire Jewish population lived in the Gharbieh (western) quarter. Safed's population reached over 15,000 in 1879, 8,000 of whom were Muslims and 7,000 Jews. A population list from about 1887 showed that Safad had 24,615 inhabitants; 2,650 Jewish households, 2,129 Muslim households and 144 Roman Catholic households. Arab families in Safed whose social status rose as a result of the Tanzimat reforms included the Asadi, whose presence in Safed dated to the 16th century, Hajj Sa'id, Hijazi, Bisht, Hadid, Khouri, a Christian family whose progenitor moved to the city from Mount Lebanon during the 1860 civil war, and Sabbagh, a long-established Christian family in the city related to Zahir al-Umar's fiscal adviser Ibrahim al-Sabbagh; many members of these families became officials in the civil service, local administrations or businessmen. When the Ottomans established a branch of the Agricultural Bank in the city in 1897, all of its board members were resident Arabs, the most influential of whom were Husayn Abd al-Rahim Effendi, Hajj Ahmad al-Asadi, As'ad Khouri and Abd al-Latif al-Hajj Sa'id. The latter two also became board members of the Chamber of Commerce and Agriculture branch opened in Safed in 1900. In the last decade of the 19th century, Safed contained 2,000 houses, four mosques, three churches, two public bathhouses, one caravanserai, two public '' sabils'', nineteen mills, seven olive oil presses, ten bakeries, fifteen coffeehouses, forty-five stalls and three shops.

6

/ref> Safed remained a mixed city during the

File:Zoltan Kluger. Safed.jpg, Safad 1937

File:Safed iv.jpg, Mandate Police station at Mount Canaan, above Safed (1948)

File:Safed 1948.jpg, Safed (1948)

File:Safed citadel.jpg, Safed Citadel (1948)

File:Safad v.jpg, Safad Municipal Police Station after the battle (1948)

File:Safad i.jpg, Bussel House, Safad, 11 April 1948:

access date: 24/1/2018

/ref>

;Citadel Hill

The Citadel Hill, in Hebrew HaMetzuda, rises east of the Old City and is named after the huge Crusader and then Mamluk castle built there during the 12th and 13th centuries, which continued in use until being totally destroyed by the 1837 earthquake. Its ruins are still visible. On the western slope beneath the ruins stands the former British police station, still pockmarked by bullet holes from the 1948 war.

;Old Jewish Quarter

;Citadel Hill

The Citadel Hill, in Hebrew HaMetzuda, rises east of the Old City and is named after the huge Crusader and then Mamluk castle built there during the 12th and 13th centuries, which continued in use until being totally destroyed by the 1837 earthquake. Its ruins are still visible. On the western slope beneath the ruins stands the former British police station, still pockmarked by bullet holes from the 1948 war.

;Old Jewish Quarter

Before 1948, most of Safed's Jewish population used to live in the northern section of the old city. Currently home to 32 synagogues, it is also referred to as the synagogue quarter and includes synagogues named after prominent rabbis of the town: the Abuhav, Alsheich, Karo and two named for Rabbi

Before 1948, most of Safed's Jewish population used to live in the northern section of the old city. Currently home to 32 synagogues, it is also referred to as the synagogue quarter and includes synagogues named after prominent rabbis of the town: the Abuhav, Alsheich, Karo and two named for Rabbi

File:Meron 181.jpg, Monument to the Israeli soldiers who fought in the

City Council website

zefat.net

Nefesh B' Nefesh Community Guide for Tzfat

* Survey of Western Palestine, Map 4

IAAWikimedia commons

Safed on the PEF Map {{Authority control Holy cities Cities in Northern District (Israel) Jewish pilgrimage sites Crusader castles Castles and fortifications of the Kingdom of Jerusalem Castles and fortifications of the Knights Templar Castles in Israel Ancient Jewish settlements of Galilee Ottoman clock towers Clock towers in Israel Holy cities of Judaism

De constructione castri Saphet

''De constructione castri Saphet'' ("On the Construction of the Castle of Ṣafad") is a short anonymous Latin account of the re-building of the fortress of Ṣafad by the Knights Templar between 1241 and 1244. There is no other account of its k ...

'', from the early 1260s. The reconstruction was completed at the considerable expense of 40,000 bezant

In the Middle Ages, the term bezant (, from Latin ) was used in Western Europe to describe several gold coins of the east, all derived ultimately from the Roman . The word itself comes from the Greek Byzantion, the ancient name of Constantinop ...

s in 1243.Amitai-Preiss 1995, p. 757. The new fortress was larger than the original, with a capacity for 2,200 soldiers in time of war, and with a resident force of 1,700 in peacetime. The garrison's goods and services were provided by the town or large village growing rapidly beneath the fortress, which, according to Benoit's account, contained a market, "numerous inhabitants" and was protected by the fortress. The settlement also benefited from trade with travelers on the route between Acre

The acre ( ) is a Unit of measurement, unit of land area used in the Imperial units, British imperial and the United States customary units#Area, United States customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one Chain (unit), ch ...

and the Jordan Valley, which passed through Safed.

Mamluk period

The Ayyubids of Egypt had been supplanted by the

The Ayyubids of Egypt had been supplanted by the Mamluks

Mamluk or Mamaluk (; (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural); translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave") were non-Arab, ethnically diverse (mostly Turkic, Caucasian, Eastern and Southeastern European) enslaved mercenaries, slave-sold ...

in 1250 and the Mamluk sultan Baybars

Al-Malik al-Zahir Rukn al-Din Baybars al-Bunduqdari (; 1223/1228 – 1 July 1277), commonly known as Baibars or Baybars () and nicknamed Abu al-Futuh (, ), was the fourth Mamluk sultan of Egypt and Syria, of Turkic Kipchak origin, in the Ba ...

entered Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

with his army in 1261. Thereafter, he led a series of campaigns over several years against Crusader strongholds across the Syrian coastal mountains. Safed, with its position overlooking the Jordan River and allowing the Crusaders early warnings of Muslim troop movements in the area, had been a consistent aggravation for the Muslim regional powers. After a six-week siege,Luz 2014, p. 35. Baybars captured Safed in July 1266, after which he had nearly the entire garrison killed.Amitai-Preiss 1995, p. 758. The siege occurred during a Mamluk military campaign to subdue Crusader strongholds in Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

and followed a failed attempt to capture the Crusaders' coastal stronghold of Acre. Unlike the Crusader fortresses along the coastline, which were demolished upon their capture by the Mamluks, Baybars spared the fortress of Safed.Drory 2004, p. 165. He likely preserved it because of the strategic value stemming from its location on a high mountain and its isolation from other Crusader fortresses. Moreover, Baybars determined that in the event of a renewed Crusader invasion of the coastal region, a strongly fortified Safed could serve as an ideal headquarters to confront the Crusader threat. In 1268, he had the fortress repaired, expanded and strengthened. He commissioned numerous building works in the town of Safed, including caravanserai

A caravanserai (or caravansary; ) was an inn that provided lodging for travelers, merchants, and Caravan (travellers), caravans. They were present throughout much of the Islamic world. Depending on the region and period, they were called by a ...

s, markets

Market is a term used to describe concepts such as:

*Market (economics), system in which parties engage in transactions according to supply and demand

*Market economy

*Marketplace, a physical marketplace or public market

*Marketing, the act of sat ...

and baths, and converted the town's church into a mosque.Drory 2004, p. 166. The mosque, called Jami al-Ahmar (the Red Mosque), was completed in 1275. By the end of Baybars's reign, Safed had developed into a prosperous town and fortress.

Baybars assigned fifty-four mamluk

Mamluk or Mamaluk (; (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural); translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave") were non-Arab, ethnically diverse (mostly Turkic, Caucasian, Eastern and Southeastern European) enslaved mercenaries, slave-so ...

s, at the head of whom was Emir Ala al-Din Kandaghani, to oversee the management of Safed and its dependencies.Barbé 2016, pp. 71–72. From the time of its capture, the city was made the administrative center of Mamlakat Safad,Sharon, 1997, pxii

/ref> one of seven ''mamlakas'' (provinces), whose governors were typically appointed from

Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

, which made up Mamluk Syria

The Mamluk Sultanate (), also known as Mamluk Egypt or the Mamluk Empire, was a state that ruled medieval Egypt, Egypt, the Levant and the Hejaz from the mid-13th to early 16th centuries, with Cairo as its capital. It was ruled by a military c ...

. Initially, its jurisdiction corresponded roughly with the Crusader ''castellany''. After the fall of the Montfort Castle

Montfort (, Mivtzar Monfor; , ''Qal'at al-Qurain'' or ''Qal'at al-Qarn'' - "Castle of the Little Horn" or "Castle of the Horn"; German: ''Burg Starkenberg'') is a ruined Crusader castle in the Upper Galilee region in northern Israel, about n ...

to the Mamluks in 1271, the castle and its dependency, the Shaghur district, were incorporated into Mamlakat Safad. The territorial jurisdiction of the ''mamlaka'' eventually spanned the entire Galilee and the lands further south down to Jenin

Jenin ( ; , ) is a city in the West Bank, Palestine, and is the capital of the Jenin Governorate. It is a hub for the surrounding towns. Jenin came under Israeli occupied territories, Israeli occupation in 1967, and was put under the administra ...

.

The geographer

The geographer al-Dimashqi The Arabic '' nisbah'' (attributive title) Al-Dimashqi () denotes an origin from Damascus, Syria.

Al-Dimashqi may refer to:

* Al-Dimashqi (geographer): a medieval Arab geographer.

* Abu al-Fadl Ja'far ibn 'Ali al-Dimashqi: 12th-century Muslim merc ...

, who died in Safed in 1327, wrote around 1300 that Baybars built a "round tower and called it Kullah ..." after leveling the old fortress. The tower was built in three stories, and provided with provisions, halls, and magazine

A magazine is a periodical literature, periodical publication, print or digital, produced on a regular schedule, that contains any of a variety of subject-oriented textual and visual content (media), content forms. Magazines are generally fin ...

s. Under the structure, a cistern

A cistern (; , ; ) is a waterproof receptacle for holding liquids, usually water. Cisterns are often built to catch and store rainwater. To prevent leakage, the interior of the cistern is often lined with hydraulic plaster.

Cisterns are disti ...

collected enough rainwater to regularly supply the garrison. The governor of Safed, Emir Baktamur al-Jukandar (the Polomaster; ), built a mosque later called after him in the northeastern section of the city. The geographer Abu'l Fida (1273–1331), the ruler of Hama

Hama ( ', ) is a city on the banks of the Orontes River in west-central Syria. It is located north of Damascus and north of Homs. It is the provincial capital of the Hama Governorate. With a population of 996,000 (2023 census), Hama is one o ...

, described Safed as follows:afedwas a town of medium size. It has a very strongly built castle, which dominates the Lake of TabariyyahThe native ''ea of Galilee Electronic Arts Inc. (EA) is an American video game company headquartered in Redwood City, California. Founded in May 1982 by former Apple employee Trip Hawkins, the company was a pioneer of the early home computer game industry and promote ...There are underground watercourses, which bring drinking-water up to the castle-gate...Its suburbs cover three hills... Since the place was conquered by Al Malik Adh Dhahiraybars Aybars is a Turkish forename meaning either "gray/yellow leopard" or "leopard of the moon", related to Turkic mythology. The stem of the name comes from " ''ay''" ('moon' in Turkic) and " ''bars''" ('leopard' in Turkic). However, according to Pr ...from the Franks rusaders it has been made the central station for the troops who guard all the coast-towns of that district."

qadi

A qadi (; ) is the magistrate or judge of a Sharia court, who also exercises extrajudicial functions such as mediation, guardianship over orphans and minors, and supervision and auditing of public works.

History

The term '' was in use from ...

'' (Islamic head judge) of Safed, Shams al-Din al-Uthmani, composed a text about Safed called ''Ta'rikh Safad'' (the History of Safed) during the rule of its governor Emir Alamdar (). The extant parts of the work consisted of ten folios largely devoted to Safed's distinguishing qualities, its dependent villages, agriculture, trade and geography, with no information about its history. His account reveals the city's dominant features were its citadel, the Red Mosque and its towering position over the surrounding landscape. He noted Safed lacked "regular urban planning", ''madrasa

Madrasa (, also , ; Arabic: مدرسة , ), sometimes Romanization of Arabic, romanized as madrasah or madrassa, is the Arabic word for any Educational institution, type of educational institution, secular or religious (of any religion), whet ...

s'' (schools of Islamic law), ''ribat

A ribāṭ (; hospice, hostel, base or retreat) is an Arabic term, initially designating a small fortification built along a frontier during the first years of the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb to house military volunteers, called ''murabitun' ...

s'' (hostels for military volunteers) and defensive walls, and that its houses were clustered in disarray and its streets were not distinguishable from its squares. He attributed the city's shortcomings to the dearth of generous patrons.Luz 2014, p. 180. A device for transporting buckets of water called the ''satura'' existed in the city mainly to supply the soldiers of the citadel; surplus water was distributed to the city's residents. Al-Uthmani praised the natural beauty of Safed, its therapeutic air, and noted that its residents took strolls in the surrounding gorges and ravines.

The Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

brought about a decline in the population in Safed from 1348 onward. There is little available information about the city and its dependencies during the last century of Mamluk rule (), though travelers' accounts describe a general decline precipitated by famine, plagues, natural disasters and political instability.

Ottoman era

Sixteenth-century prosperity

The Ottomans conquered Mamluk Syria following their victory at the

The Ottomans conquered Mamluk Syria following their victory at the Battle of Marj Dabiq

The Battle of Marj Dābiq (, meaning "the meadow of Dābiq"; ), a decisive military engagement in Middle Eastern history, was fought on 24 August 1516, near the town of Dabiq, 44 km north of Aleppo (modern Syria). The battle was part of t ...

in northern Syria in 1516.Rhode 1979, p. 18. Safed's inhabitants sent the keys of the town citadel to Sultan Selim I

Selim I (; ; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute (), was the List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire, sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite lasting only eight years, his reign is ...

after he captured Damascus.Layish 1987, p. 67. No fighting was recorded around Safed, which was bypassed by Selim's army on the way to Mamluk Egypt. The sultan had placed the district of Safed under the jurisdiction of the Mamluk governor of Damascus, Janbirdi al-Ghazali

Janbirdi al-Ghazali (; died 1521) was the first governor of Damascus Province under the Ottoman Empire from February 1519 until his death in February 1521.

Career Viceroy of Hama and Governor of Damascus

Al-Ghazali was originally the '' na'ib'' ...

, who defected to the Ottomans. Rumors in 1517 that Selim was slain by the Mamluks precipitated a revolt against the newly appointed Ottoman governor by the townspeople of Safed, which resulted in wide-scale killings, many of which targeted the city's Jews, who were viewed as sympathizers of the Ottomans. Safed became the capital of the Safed Sanjak

Safed Sanjak (; ) was a ''sanjak'' (district) of Damascus Eyalet ( Ottoman province of Damascus) in 1517–1660, after which it became part of the Sidon Eyalet (Ottoman province of Sidon). The sanjak was centered in Safed and spanned the Galilee, ...

, roughly corresponding with Mamlakat Safad but excluding most of the Jezreel Valley and the area of Atlit Atlit or Athlit may refer to:

Places

* Atlit, an historical fortified town in Israel, also known as Château Pèlerin

* Atlit (modern town), a nearby town in Israel

Media

*Athlit (album), ''Athlit'' (album), an ambient music album by Oöphoi

*Atli ...

, part of the larger province of Damascus Eyalet

Damascus Eyalet (; ) was an eyalet of the Ottoman Empire. Its reported area in the 19th century was . It became an eyalet after the Ottomans took it from the Mamluks following the 1516–1517 Ottoman–Mamluk War. By Gábor Ágoston, Bruce Alan ...

.Abbasi 2003, p. 50.

In 1525/26, the population of Safed consisted of 633 Muslim families, 40 Muslim bachelors, 26 Muslim religious persons, nine Muslim disabled, 232 Jewish families, and 60 military families. In 1549, under Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I (; , ; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the Western world and as Suleiman the Lawgiver () in his own realm, was the List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman sultan between 1520 a ...

, a wall was constructed and troops were garrisoned to protect the city.Abraham David, 2010pp. 95–96

/ref> In 1553/54, the population consisted of 1,121 Muslim households, 222 Muslim bachelors, 54 Muslim religious leaders, 716 Jewish households, 56 Jewish bachelors, and 9 disabled persons. At least in the 16th century, Safed was the only ''kasaba'' (city) in the sanjak and in 1555 was divided into nineteen ''mahallas'' (quarters), seven Muslim and twelve Jewish.Rhode 1979, p. 34. The total population of Safed rose from 926 households in 1525–26 to 1,931 households in 1567–1568. Among these, the Jewish population rose from a mere 233 households in 1525 to 945 households in 1567–1568.Petersen (2001), Gazetteer 6, s,v

Ṣafad

/ref> The Muslim quarters were Sawawin, located west of the fortress; Khandaq (the moat); Ghazzawiyah, which had likely been settled by Gazans; Jami' al-Ahmar (the Red Mosque), located south of the fortress and named for the local mosque; al-Akrad, which dated to the Middle Ages and continued to exist through the 19th century,Ebied and Young 1976, p. 7. and whose inhabitants mainly were

Kurds

Kurds (), or the Kurdish people, are an Iranian peoples, Iranic ethnic group from West Asia. They are indigenous to Kurdistan, which is a geographic region spanning southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northeastern Syri ...

; al-Wata (the lower), the southernmost quarter of Safed and situated below the city; and al-Suq, named after the market or mosque located within the quarter.Rhode 1979, pp. 34–35. The Jewish quarters were all situated west of the fortress. Each quarter was named for the place of origin of its inhabitants: Purtuqal (Portugal), Qurtubah ( Cordoba), Qastiliyah ( Castille), Musta'rib (Jews of local, Arabic-speaking origin), Magharibah (northwestern Africa), Araghun ma' Qatalan (Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and ; ) is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces of Spain, ...

and Catalonia

Catalonia is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationalities and regions of Spain, nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia of 2006, Statute of Autonomy. Most of its territory (except the Val d'Aran) is situate ...

), Majar (Hungary), Puliah (Apulia

Apulia ( ), also known by its Italian language, Italian name Puglia (), is a Regions of Italy, region of Italy, located in the Southern Italy, southern peninsular section of the country, bordering the Adriatic Sea to the east, the Strait of Ot ...

), Qalabriyah (Calabria

Calabria is a Regions of Italy, region in Southern Italy. It is a peninsula bordered by the region Basilicata to the north, the Ionian Sea to the east, the Strait of Messina to the southwest, which separates it from Sicily, and the Tyrrhenian S ...

), Sibiliyah (Seville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

), Taliyan (Italian) and Alaman (German).

In the 15th and 16th centuries there were several well-known Sufis

Sufism ( or ) is a mystic body of religious practice found within Islam which is characterized by a focus on Islamic purification, spirituality, ritualism, and asceticism.

Practitioners of Sufism are referred to as "Sufis" (from , ), and ...

(mystics) of ibn Arabi

Ibn Arabi (July 1165–November 1240) was an Andalusian Sunni

Sunni Islam is the largest branch of Islam and the largest religious denomination in the world. It holds that Muhammad did not appoint any successor and that his closest com ...

living in Safed. The Sufi sage Ahmad al-Asadi (1537–1601) established a ''zawiya'' (Sufi lodge) called Sadr Mosque in the city. Safed became a center of Kabbalah

Kabbalah or Qabalah ( ; , ; ) is an esoteric method, discipline and school of thought in Jewish mysticism. It forms the foundation of Mysticism, mystical religious interpretations within Judaism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal ...

(Jewish mysticism) during the 16th century.

After the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492, many prominent rabbi

A rabbi (; ) is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi—known as ''semikha''—following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of t ...

s found their way to Safed, among them the Kabbalists Isaac Luria

Isaac ben Solomon Ashkenazi Luria (; #FINE_2003, Fine 2003, p24/ref>July 25, 1572), commonly known in Jewish religious circles as Ha'ari, Ha'ari Hakadosh or Arizal, was a leading rabbi and Jewish mysticism, Jewish mystic in the community of Saf ...

and Moses ben Jacob Cordovero

Moses ben Jacob Cordovero ( ''Moshe Kordovero'' ; 1522–1570) was a central figure in the historical development of Kabbalah, leader of a mystical school in the Ottoman Empire in 16th-century Safed, located in the modern State of Israel. H ...

; Joseph Caro

Joseph ben Ephraim Karo, also spelled Yosef Caro, or Qaro (; 1488 – March 24, 1575, 13 Nisan 5335 A.M.), was a prominent Sephardic Jewish rabbi renowned as the author of the last great codification of Jewish law, the ''Beit Yosef'', and its ...

, the author of the ''Shulchan Aruch

The ''Shulhan Arukh'' ( ),, often called "the Code of Jewish Law", is the most widely consulted of the various legal codes in Rabbinic Judaism. It was authored in the city of Safed in what is now Israel by Joseph Karo in 1563 and published in ...

''; and Solomon Alkabetz

Solomon ha-Levi Alkabetz (; – 1584) was a rabbi, kabbalist and poet. He is perhaps best known for his composition of the song ''Lekha Dodi''.

Biography

Solomon Alkabetz was likely born around 1505 into a Sephardic family in the Ottoman ci ...

, composer of the Shabbat

Shabbat (, , or ; , , ) or the Sabbath (), also called Shabbos (, ) by Ashkenazi Hebrew, Ashkenazim, is Judaism's day of rest on the seventh day of the seven-day week, week—i.e., Friday prayer, Friday–Saturday. On this day, religious Jews ...

hymn "Lekha Dodi

Lekha Dodi () is a Hebrew-language Jewish liturgical song recited Friday at dusk, usually at sundown, in synagogue to welcome the Sabbath prior to the evening services. It is part of Kabbalat Shabbat.

The refrain of ''Lekha Dodi'' means "Let ...

".

The influx of Sephardic Jews

Sephardic Jews, also known as Sephardi Jews or Sephardim, and rarely as Iberian Peninsular Jews, are a Jewish diaspora population associated with the historic Jewish communities of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) and their descendant ...

—reaching its peak under the rule of sultans Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I (; , ; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the Western world and as Suleiman the Lawgiver () in his own realm, was the List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman sultan between 1520 a ...

and Selim II

Selim II (; ; 28 May 1524 – 15 December 1574), also known as Selim the Blond () or Selim the Drunkard (), was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1566 until his death in 1574. He was a son of Suleiman the Magnificent and his wife Hurrem Sul ...

—made Safed a global center for Jewish learning and a regional center for trade throughout the 15th and 16th centuries. Sephardi Jews and other Jewish immigrants by then outnumbered Musta'arabi Jews

Musta'arabi Jews ( al-Mustaʿribīn " Mozarabs"; ''Mustaʿravim'') were the Arabic-speaking Jews, largely Mizrahi Jews and Maghrebi Jews, who lived in the Middle East and North Africa prior to the arrival and integration of Ladino-speaking Seph ...

in the city.

During this period, the Jewish community developed the textile industry in Safed, transforming the town into an important and lucrative wool production and textile manufacturing centre. There were more than 7,000 Jews in Safed in 1576 when Murad III

Murad III (; ; 4 July 1546 – 16 January 1595) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1574 until his death in 1595. His rule saw battles with the Habsburg monarchy, Habsburgs and exhausting wars with the Safavid Iran, Safavids. The long-inde ...

proclaimed the forced deportation of 1,000 wealthy Jewish families to Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

to boost the island's economy. There is no evidence that the edict or a second one issued the following year for removing 500 families, was enforced. In 1584, there were 32 synagogue

A synagogue, also called a shul or a temple, is a place of worship for Jews and Samaritans. It is a place for prayer (the main sanctuary and sometimes smaller chapels) where Jews attend religious services or special ceremonies such as wed ...

s registered in the town.

A Hebrew printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in whi ...

, the first in West Asia, was established in Safed in 1577 by Eliezer ben Isaac Ashkenazi of Prague and his son, Isaac.

Political decline, attacks and natural disasters

By the early part of the 17th century, Safed was a small town. In 1602, the paramount chief of the Druze in Mount Lebanon,

By the early part of the 17th century, Safed was a small town. In 1602, the paramount chief of the Druze in Mount Lebanon, Fakhr al-Din II

Fakhr al-Din Ma'n (; 6 August 1572 13 April 1635), commonly known as Fakhr al-Din II or Fakhreddine II (), was the paramount Druze emir of Mount Lebanon from the Ma'n dynasty, an Ottoman Empire, Ottoman sanjak-bey, governor of Sidon-Beirut Sanj ...

of the Ma'n dynasty

The Ma'n dynasty (, alternatively spelled ''Ma'an''), also known as the Ma'nids; (), were a family of Druze chiefs of Arab stock based in the rugged Chouf District, Chouf area of southern Mount Lebanon who were politically prominent in the 15th� ...

, was appointed the sanjak-bey

''Sanjak-bey'', ''sanjaq-bey'' or ''-beg'' () was the title given in the Ottoman Empire to a bey (a high-ranking officer, but usually not a pasha) appointed to the military and administrative command of a district (''sanjak'', in Arabic '' liwa’' ...

(district governor) of Safed, in addition to his governorship of neighbouring Sidon-Beirut Sanjak

Sidon-Beirut Sanjak was a ''sanjak'' (district) of Sidon Eyalet (Province of Sidon) of the Ottoman Empire. Prior to 1660, the Sidon-Beirut Sanjak had been part of Damascus Eyalet, and for brief periods in the 1590s, Tripoli Eyalet.

Territory and ...

to the north. In the preceding years, the Safed Sanjak had entered a state of ruin and desolation and was often the scene of conflict between the local Druze and Shia Muslim peasants and the Ottoman authorities. By 1605, Fakhr al-Din had established peace and security in the sanjak, with highway brigandage and Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu ( ; , singular ) are pastorally nomadic Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia (Iraq). The Bedouin originated in the Sy ...

raids having ceased under his watch. Trade and agriculture consequently thrived and the population prospered. He formed close relations with the city's Sunni Muslim

Sunni Islam is the largest branch of Islam and the largest religious denomination in the world. It holds that Muhammad did not appoint any successor and that his closest companion Abu Bakr () rightfully succeeded him as the caliph of the Musli ...

ulama

In Islam, the ''ulama'' ( ; also spelled ''ulema''; ; singular ; feminine singular , plural ) are scholars of Islamic doctrine and law. They are considered the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious knowledge in Islam.

"Ulama ...

(religious scholars), particularly the mufti

A mufti (; , ) is an Islamic jurist qualified to issue a nonbinding opinion ('' fatwa'') on a point of Islamic law (''sharia''). The act of issuing fatwas is called ''iftāʾ''. Muftis and their ''fatāwa'' have played an important role thro ...

, al-Khalidi al-Safadi of the Hanafi school

The Hanafi school or Hanafism is the oldest and largest Madhhab, school of Islamic jurisprudence out of the four schools within Sunni Islam. It developed from the teachings of the Faqīh, jurist and theologian Abu Hanifa (), who systemised the ...

of fiqh

''Fiqh'' (; ) is the term for Islamic jurisprudence.Fiqh

Encyclopædia Britannica ''Fiqh'' is of ...

(Islamic jurisprudence), who became his practical court historian.

The Ottomans drove Fakhr al-Din into European exile in 1613, but his son Ali became governor in 1615. Fakhr al-Din returned to his domains in 1618 and five years later regained the governorship of Safed, which the Encyclopædia Britannica ''Fiqh'' is of ...

Ma'n dynasty

The Ma'n dynasty (, alternatively spelled ''Ma'an''), also known as the Ma'nids; (), were a family of Druze chiefs of Arab stock based in the rugged Chouf District, Chouf area of southern Mount Lebanon who were politically prominent in the 15th� ...

had lost, after his victory against the governor of Damascus at the Battle of Anjar

The Battle of Anjar was fought on 1 November 1623 between the army of Fakhr al-Din II and an coalition army led by the List of rulers of Damascus#Ottoman walis, governor of Damascus Mustafa Pasha.

Background

In 1623, Harfush dynasty, Yunus al-H ...

. In , the orientalist Franciscus Quaresmius

Francisco Quaresmio or Quaresmi (4 April 1583 – 25 October 1650), better known by his Latinisation of names, Latin name Franciscus Quaresmius, was an Italian writer and oriental studies, Orientalist.

Life

Quaresmius was born at Lodi, Lomb ...

spoke of Safed being inhabited "chiefly by Hebrews, who had their synagogues and schools, and for whose sustenance contributions were made by the Jews in other parts of the world." According to the historian Louis Finkelstein, the Jewish community of Safed was plundered by the Druze under Mulhim ibn Yunus, nephew of Fakhr al-Din.Finkelstein 1960, p. 63. Five years later, Fakhr al-Din was routed by the Ottoman governor of Damascus, Mulhim abandoned Safed, and its Jewish residents returned.

The Druze again attacked the Jews of Safed in 1656. During the power struggle between Fakhr al-Din's heirs (1658–1667), each faction attacked Safed. In the intra-communal turmoil among the Druze following the death of Mulhim, the 1660 destruction of Safed

The 1660 destruction of Safed occurred during the Druze power struggle in Mount Lebanon, at the time of the rule of Ottoman sultan Mehmed IV. The towns of Safed and nearby Tiberias, with substantial Jewish communities, were destroyed in the tu ...

targeted the Jews there and in Tiberias; only a few of the former Jewish residents returned to the city before 1662.Joel Rappel. ''History of Eretz Israel from Prehistory up to 1882'' (1980), Vol.2, p.531. "In 1662 Sabbathai Sevi __NOTOC__

Shabtai ( or ) is a Jewish name, Jewish masculine name, masculine given name derived from the Hebrew word Shabbat, and is traditionally given to boys born on that day. Alternative transliterations into English include Sabbatai, Sabbathai, ...

arrived to Jerusalem. It was the time when the Jewish settlements of Galilee were destroyed by the Druze: Tiberias was completely desolate and only a few of former Safed residents had returned..."Barnai, Jacob. ''The Jews in Palestine in the Eighteenth Century: under the patronage of the Istanbul Committee of Officials for Palestine'' (University of Alabama Press 1992) ; p. 14 Survivors relocated mainly to Sidon

Sidon ( ) or better known as Saida ( ; ) is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located on the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean coast in the South Governorate, Lebanon, South Governorate, of which it is the capital. Tyre, Lebanon, Tyre, t ...

or Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

.

Safed Sanjak

Safed Sanjak (; ) was a ''sanjak'' (district) of Damascus Eyalet ( Ottoman province of Damascus) in 1517–1660, after which it became part of the Sidon Eyalet (Ottoman province of Sidon). The sanjak was centered in Safed and spanned the Galilee, ...

and the neighbouring Sidon-Beirut Sanjak

Sidon-Beirut Sanjak was a ''sanjak'' (district) of Sidon Eyalet (Province of Sidon) of the Ottoman Empire. Prior to 1660, the Sidon-Beirut Sanjak had been part of Damascus Eyalet, and for brief periods in the 1590s, Tripoli Eyalet.

Territory and ...

to the north were administratively separated from Damascus in 1660 to form the Sidon Eyalet

The Eyalet of Sidon (; ) was an eyalet (also known as a ''beylerbeylik'') of the Ottoman Empire. In the 19th century, the eyalet extended from the border with Egypt to the Bay of Kisrawan, including parts of modern Israel and Lebanon.

Depending ...

, of which Safed was briefly the capital.Salibi 1988, p. 66. The province was created by the imperial government to check the power of the Druze of Mount Lebanon, as well as the Shia of Jabal Amil

Jabal Amil (; also spelled Jabal Amel and historically known as Jabal Amila) is a cultural and geographic region in Southern Lebanon largely associated with its long-established, predominantly Twelver Shia Muslim inhabitants. Its precise bounda ...

.

As nearby Tiberias remained desolate for several decades, Safed gained a key position among Galilean

Generically, a Galilean (; ; ; ) is a term that was used in classical sources to describe the inhabitants of Galilee, an area of northern Israel and southern Lebanon that extends from the northern coastal plain in the west to the Sea of Galile ...

Jewish communities. In 1665, the Sabbatai Sevi

Sabbatai Zevi (, August 1, 1626 – ) was an Ottoman Jewish mystic and ordained rabbi from Smyrna (now İzmir, Turkey). His family were Romaniote Jews from Patras. His two names, ''Shabbethay'' and ''Ṣebi'', mean Saturn and mountain gazelle, r ...

movement arrived in Safed. In the 1670s, the account of the Turkish traveller Evliya Çelebi

Dervish Mehmed Zillî (25 March 1611 – 1682), known as Evliya Çelebi (), was an Ottoman Empire, Ottoman explorer who travelled through his home country during its cultural zenith as well as neighboring lands. He travelled for over 40 years, rec ...

recorded that Safed contained three caravanserai

A caravanserai (or caravansary; ) was an inn that provided lodging for travelers, merchants, and Caravan (travellers), caravans. They were present throughout much of the Islamic world. Depending on the region and period, they were called by a ...

s, several mosque

A mosque ( ), also called a masjid ( ), is a place of worship for Muslims. The term usually refers to a covered building, but can be any place where Salah, Islamic prayers are performed; such as an outdoor courtyard.

Originally, mosques were si ...

s, seven zawiyas, and six hammam

A hammam (), also often called a Turkish bath by Westerners, is a type of steam bath or a place of public bathing associated with the Islamic world. It is a prominent feature in the culture of the Muslim world and was inherited from the model ...

s. The Red Mosque was restored by Safed's governor Salih Bey in 1671/72, at which point it measured about , had all masonry interior, a cistern to collect rainwater in the winter for drinking and a tall minaret

A minaret is a type of tower typically built into or adjacent to mosques. Minarets are generally used to project the Muslim call to prayer (''adhan'') from a muezzin, but they also served as landmarks and symbols of Islam's presence. They can h ...

over its southern entrance; the minaret had been destroyed before the end of the 17th century.

The Tiberias-based sheikh Zahir al-Umar

Zahir al-Umar al-Zaydani, alternatively spelled Dhaher el-OmarDAAHL Site Rec ...

of the local Arab Zaydan clan, whose father Umar al-Zaydani

Umar al-Zaydani (died 1706) was the ''mutasallim, multazem'' (tax farmer) of Safad and Tiberias, and surrounding villages, between 1697 and 1706 and the ''sanjak-bey'' (district governor) of Safad between 1701 and 1706.Joudah 1987, pp. 20-21. He wa ...

had been the governor and tax farmer of Safed in 1702–1706, wrested control of Safed and its tax farm

Farming or tax-farming is a technique of financial management in which the management of a variable revenue stream is assigned by contract, legal contract to a third party and the holder of the revenue stream receives fixed periodic rents from t ...

from its native strongman, Muhammad Naf'i, through military pressure and diplomacy by 1740. The Naf'i, Shahin, and Murad families continued to farm the taxes of Safed and its countryside into the 1760s as Zahir's subordinates. By the 1760s, Zahir entrusted Safed to his son Ali, who made the town his headquarters. After Zahir was killed by Ottoman imperial forces, the governor of Sidon, Jazzar Pasha

Ahmed Pasha al-Jazzar (, c. 1720–30s7 May 1804) was the Acre-based Bosniak Ottoman governor of Sidon Eyalet from 1776 until his death in 1804 and the simultaneous governor of Damascus Eyalet in 1785–1786, 1790–1795, 1798–1799, and 1803 ...

, moved to oust Zahir's sons from their Galilee strongholds. Ali made a final, unsuccessful stand against Jazzar Pasha from Safed, which was afterward captured and garrisoned by the governor. The simultaneous rise of Acre, established by Zahir as his capital in 1750 and which served as the capital of the Sidon Eyalet under Jazzar Pasha (1775–1804) and his successors, Sulayman Pasha al-Adil

Sulayman Pasha al-Adil ( – August 1819; given name also spelled ''Suleiman'' or ''Sulaiman'') was the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman governor of Sidon Eyalet between 1805 and 1819, ruling from his Acre, Israel, Acre headquarters. He also simultaneously ...

(1805–1819) and Abdullah Pasha (1820–1831), contributed to the political decline of Safed. It became a subdistrict center with limited local influence, belonging to the Acre Sanjak

The Sanjak of Acre (; ), often referred as Late Ottoman Galilee, was a prefecture (sanjak) of the Ottoman Empire, located in modern-day northern Israel. The city of Acre was the Sanjak's capital.

Acre was captured by the Ottoman Sultan Selim I in ...

.

Underdevelopment and a series of natural disasters further contributed to Safed's decline during the 17th–mid-19th centuries. An outbreak of plague decimated the population in 1742 and the Near East earthquakes of 1759

The 1759 Near East earthquakes shook a large portion of the Levant in October and November of that year. This geographical crossroads in the Eastern Mediterranean were at the time under the rule of the Ottoman Empire (includes portions of what a ...

left the city in ruins, killing 200 residents. An influx of Russian Jew

The history of the Jews in Russia and areas historically connected with it goes back at least 1,500 years. Jews in Russia have historically constituted a large religious and ethnic diaspora; the Russian Empire at one time hosted the largest po ...

s in 1776 and 1781, and of Lithuanian Jew

{{Infobox ethnic group

, group = Litvaks

, image =

, caption =

, poptime =

, region1 = {{flag, Lithuania

, pop1 = 2,800

, region2 =

{{flag, South Africa

, pop2 = 6 ...

s of the Perushim

The ''perushim'' () were Jewish disciples of the Vilna Gaon, Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, who left Lithuania at the beginning of the 19th century to settle in the Land of Israel, which was then part of Ottoman Syria. They were from the section o ...

movement in 1809 and 1810, reinvigorated the Jewish community. In 1812, another plague killed 80% of the Jewish population.Franco 1916, p. 633. Following Abdullah Pasha of Acre's ordered killing of his Jewish vizier Haim Farhi

Haim Farhi (, ; , also known as Haim "El Mu'allim", lit. "The Teacher"), (1760 – August 21, 1820) was a Jewish adviser to the governors of the Galilee in the days of the Ottoman Empire, until his assassination in 1820.

Farhi was a chief advis ...

, who served the same post under Jazzar and Sulayman, the governor imprisoned the Jewish residents of Safed on 12 August 1820, accusing them of tax evasion under the concealment of Farhi; they were released upon paying a ransom. The war between Abdullah Pasha and the influential Farhi brothers in Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

and Damascus in 1822–1823 prompted Jewish flight from the Galilee in general, though by 1824 Jewish immigrants were steadily moving to the city.

The forces of Muhammad Ali of Egypt

Muhammad Ali (4 March 1769 – 2 August 1849) was the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Albanians, Albanian viceroy and governor who became the ''de facto'' ruler of History of Egypt under the Muhammad Ali dynasty, Egypt from 1805 to 1848, widely consi ...

wrested control of the Levant from the Ottomans in 1831 and in the same year many Jews who had fled the Galilee, including Safed, under Abdullah Pasha returned as a result of Muhammad Ali's liberal policies toward Jews. Safed was raided by Druze in 1833 at the approach of Ibrahim Pasha, the Egyptian governor of the Levant. In the following year, the Muslim notables of the city, led by Salih al-Tarshihi, opposed to the Egyptian policy of conscription, joined the peasants' revolt in Palestine

The Peasants' Revolt was a rebellion against Egyptian conscription and taxation policies in Palestine between May and August 1834. While rebel ranks consisted mostly of the local peasantry, urban notables and Bedouin tribes also formed an inte ...

. During the revolt, rebels plundered the city for over thirty days. Emir Bashir Shihab II

Bashir Shihab II (, also spelled Bachir Chehab II; 2 January 1767–1850) was a Lebanese people, Lebanese emir who ruled the Mount Lebanon Emirate, Emirate of Mount Lebanon in the first half of the 19th century. Born to a branch of the Shihab dy ...

of Mount Lebanon and his Druze fighters entered its environs in support of the Egyptians and compelled Safed's leaders to surrender. The Galilee earthquake of 1837

The Galilee earthquake of 1837, often called the Safed earthquake, shook the Galilee on January 1 and is one of a number of moderate to large events that have occurred along the Dead Sea Transform fault system that marks the boundary of two tecto ...

killed about half of Safed's 4,000-strong Jewish community,Lieber 1992, p256

destroyed all fourteen of its synagogues and prompted the flight of 600

Perushim

The ''perushim'' () were Jewish disciples of the Vilna Gaon, Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, who left Lithuania at the beginning of the 19th century to settle in the Land of Israel, which was then part of Ottoman Syria. They were from the section o ...

for Jerusalem; the surviving Sephardic and Hasidic Jews mostly remained. Among the 2,158 residents of Safed who had died, 1,507 were Ottoman subjects, the rest foreign citizens. The Jewish quarter was situated on the hillside and was particularly hard hit; the southern and Muslim section of the town experienced considerably less damage. The following year, in 1838, Druze rebels and local Muslims raided Safed for three days.

Tanzimat reforms and revival

Ottoman rule was restored across the Levant in 1840. The Empire-wide

Ottoman rule was restored across the Levant in 1840. The Empire-wide Tanzimat

The (, , lit. 'Reorganization') was a period of liberal reforms in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Edict of Gülhane of 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 1876. Driven by reformist statesmen such as Mustafa Reşid Pash ...