Sacks, Oliver on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

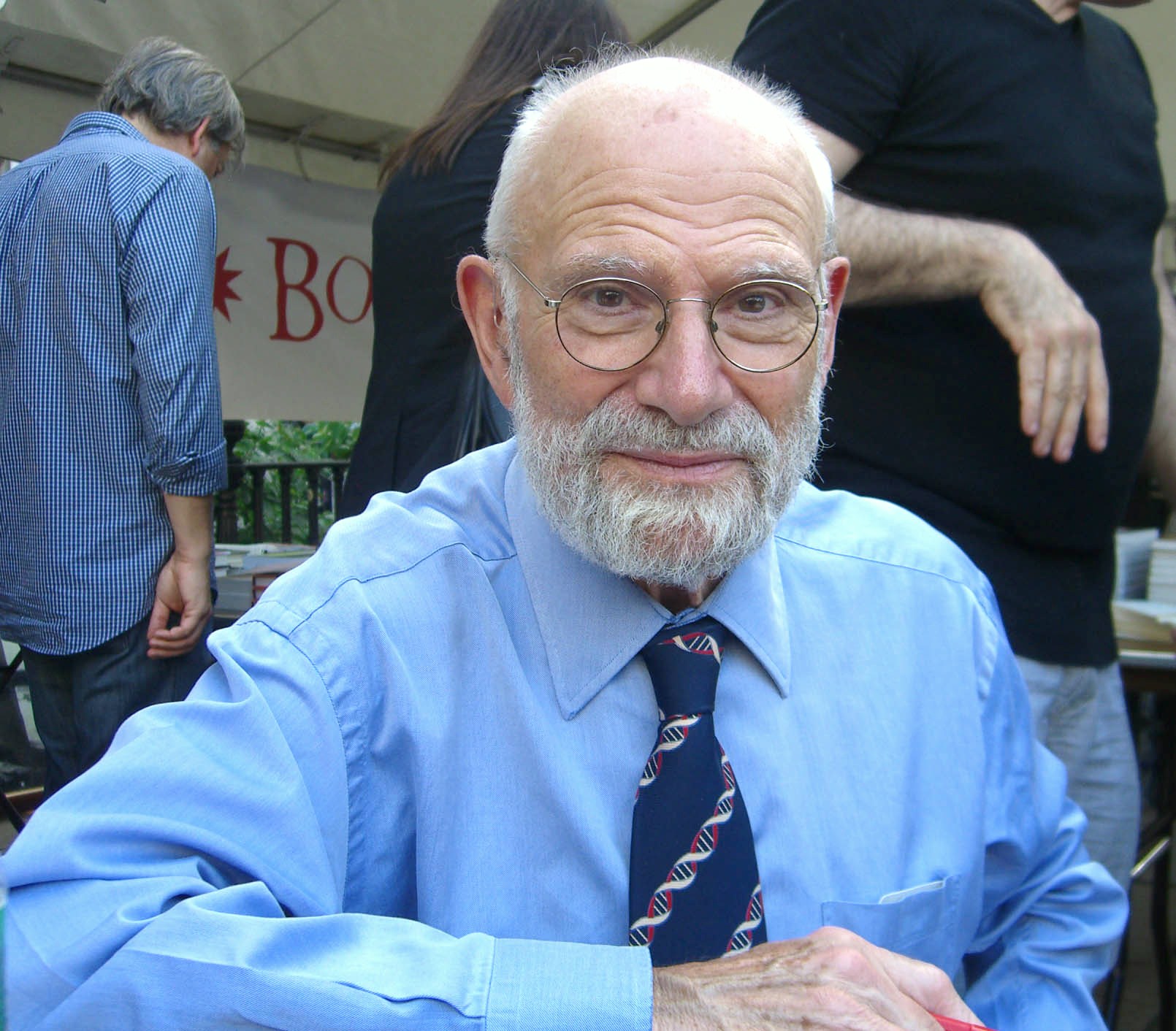

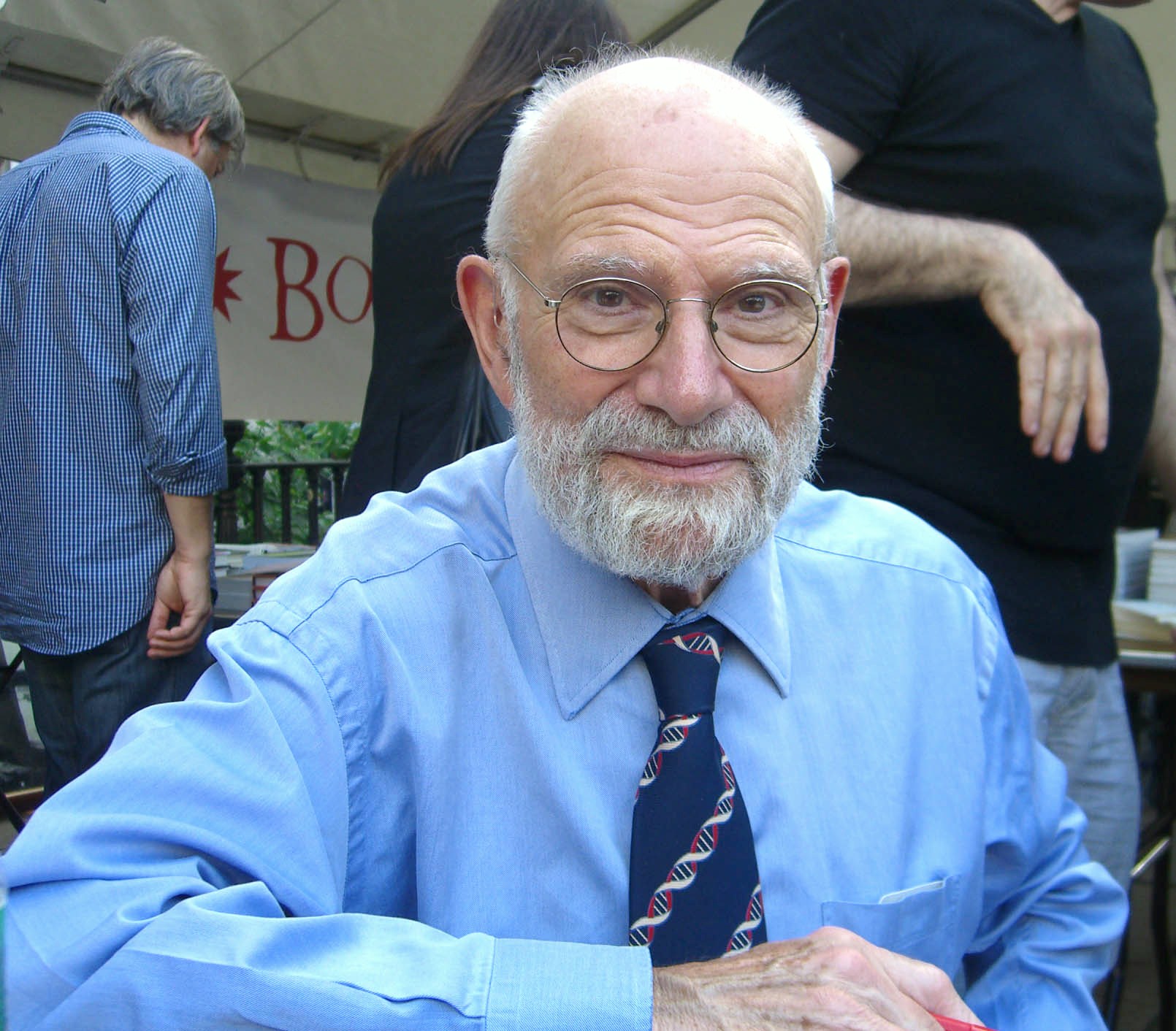

Oliver Wolf Sacks (9 July 1933 – 30 August 2015) was a British

Uncle Xenon: The Element of Oliver Sacks

''Moment Magazine'' This is detailed in his first autobiography, '' Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood''. Beginning with his return home at the age of 10, under his Uncle Dave's tutelage, he became an intensely focused amateur chemist. Later, he attended St Paul's School in London, where he developed lifelong friendships with

Sacks left Britain and flew to Montreal, Canada, on 9 July 1960, his 27th birthday. He visited the

Sacks left Britain and flew to Montreal, Canada, on 9 July 1960, his 27th birthday. He visited the

Sacks served as an instructor and later professor of clinical neurology at

Sacks served as an instructor and later professor of clinical neurology at

. Newswise.com. 13 September 2012. He returned to New York University School of Medicine in 2012, serving as a professor of neurology and consulting neurologist in the school's epilepsy centre. Sacks's work at Beth Abraham Hospital helped provide the foundation on which the

In his memoir ''A Leg to Stand On'' he wrote about the consequences of a near-fatal accident he had at age 41 in 1974, a year after the publication of ''Awakenings'', when he fell off a cliff and severely injured his left leg while

In his memoir ''A Leg to Stand On'' he wrote about the consequences of a near-fatal accident he had at age 41 in 1974, a year after the publication of ''Awakenings'', when he fell off a cliff and severely injured his left leg while

In 1996, Sacks became a member of the

In 1996, Sacks became a member of the

Sacks noted in a 2001 interview that severe shyness, which he described as "a disease", had been a lifelong impediment to his personal interactions. He believed his shyness stemmed from his

Sacks noted in a 2001 interview that severe shyness, which he described as "a disease", had been a lifelong impediment to his personal interactions. He believed his shyness stemmed from his

Oliver Sacks Biography and Interview on American Academy of AchievementThe Oliver Sacks Foundation

Ghostarchive

and th

Wayback Machine

Interview with Dempsey Rice, documentary filmmaker, about Oliver Sacks film

*, a documentary film by

neurologist

Neurology (from , "string, nerve" and the suffix -logia, "study of") is the branch of medicine dealing with the diagnosis and treatment of all categories of conditions and disease involving the nervous system, which comprises the brain, the ...

, naturalist

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

, historian of science, and writer.

Born in London, Sacks received his medical degree in 1958 from The Queen's College, Oxford

The Queen's College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford, England. The college was founded in 1341 by Robert de Eglesfield in honour of Philippa of Hainault, queen of England. It is distinguished by its predominantly neoclassi ...

, before moving to the United States, where he spent most of his career. He interned at Mount Zion Hospital in San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

and completed his residency in neurology and neuropathology

Neuropathology is the study of disease of nervous system tissue, usually in the form of either small surgical biopsies or whole-body autopsies. Neuropathologists usually work in a department of anatomic pathology, but work closely with the clini ...

at the University of California, Los Angeles

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California, United States. Its academic roots were established in 1881 as a normal school the ...

(UCLA). Later, he served as neurologist at Beth Abraham Hospital

Beth Abraham Center for Rehabilitation and Nursing is a medical facility in Bronx, New York, which was founded as the Beth Abraham Home for Incurables. It was originally a long-term residential care facility, but was later expanded to include ...

's chronic-care facility in the Bronx

The Bronx ( ) is the northernmost of the five Boroughs of New York City, boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It shares a land border with Westchester County, New York, West ...

, where he worked with a group of survivors of the 1920s sleeping sickness encephalitis lethargica

Encephalitis lethargica (EL) is an atypical form of encephalitis. Also known as "von Economo Encephalitis", "sleeping sickness" or "sleepy sickness" (distinct from tsetse fly–transmitted sleeping sickness), it was first described in 1917 by ne ...

epidemic, who had been unable to move on their own for decades. His treatment of those patients became the basis of his 1973 book ''Awakenings

''Awakenings'' is a 1990 American biographical drama film written by Steven Zaillian, directed by Penny Marshall, and starring Robert De Niro, Robin Williams, Julie Kavner, Ruth Nelson, John Heard, Penelope Ann Miller, Peter Stormare and Max ...

'', which was adapted into an Academy Award

The Academy Awards, commonly known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit in film. They are presented annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) in the United States in recognition of excellence ...

-nominated feature film

A feature film or feature-length film (often abbreviated to feature), also called a theatrical film, is a film (Film, motion picture, "movie" or simply “picture”) with a running time long enough to be considered the principal or sole present ...

, in 1990, starring Robin Williams

Robin McLaurin Williams (July 21, 1951August 11, 2014) was an American actor and comedian known for his improvisational skills and the wide variety of characters he created on the spur of the moment and portrayed on film, in dramas and comedie ...

and Robert De Niro

Robert Anthony De Niro ( , ; born August 17, 1943) is an American actor, director, and film producer. He is considered to be one of the greatest and most influential actors of his generation. De Niro is the recipient of List of awards and ...

.

His numerous other best-selling books were mostly collections of case studies

A case study is an in-depth, detailed examination of a particular case (or cases) within a real-world context. For example, case studies in medicine may focus on an individual patient or ailment; case studies in business might cover a particular fi ...

of people, including himself, with neurological disorder

Neurological disorders represent a complex array of medical conditions that fundamentally disrupt the functioning of the nervous system. These disorders affect the brain, spinal cord, and nerve networks, presenting unique diagnosis, treatment, and ...

s. He also published hundreds of articles (both peer-reviewed scientific articles and articles for a general audience), about neurological disorders, history of science, natural history, and nature. ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' called him a " poet laureate of contemporary medicine", and "one of the great clinical writers of the 20th century". Some of his books were adapted for plays by major playwrights, feature films, animated short films, opera, dance, fine art, and musical works in the classical genre. His book '' The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat'', which describes the case histories of some of his patients, became the basis of an opera of the same name.

Early life and education

Oliver Wolf Sacks was born inCricklewood

Cricklewood is a town in North London, England, in the London Boroughs of Camden, Barnet, and Brent. The Crown pub, now the Clayton Crown Hotel, is a local landmark and lies north-west of Charing Cross.

Cricklewood was a small rural hamlet ...

, London, England, the youngest of four children born to Jewish parents: Samuel Sacks, a Lithuanian Jewish

{{Infobox ethnic group

, group = Litvaks

, image =

, caption =

, poptime =

, region1 = {{flag, Lithuania

, pop1 = 2,800

, region2 =

{{flag, South Africa

, pop2 = 6 ...

doctor (died June 1990), and Muriel Elsie Landau, one of the first female surgeons in England (died 1972), who was one of 18 siblings. She would sometimes bring home deformed fetuses from work, where she would dissect them with her son as a way for him to learn about human anatomy. Sacks had an extremely large extended family of eminent scientists, physicians and other notable people, including the director and writer Jonathan Lynn

Jonathan Adam Lynn (born 3 April 1943) is an English film director, screenwriter, and actor. He directed the comedy films '' Clue'', '' Nuns on the Run'', '' My Cousin Vinny'', and '' The Whole Nine Yards''. He also co-created and co-wrote the ...

and first cousins the Israeli statesman Abba Eban

Abba Solomon Meir Eban (; ; born Aubrey Solomon Meir Eban; 2 February 1915 – 17 November 2002) was a History of the Jews in South Africa, South African-born Israeli diplomat and politician, and a scholar of the Arabic and Hebrew languages.

D ...

and the Nobel Laureate Robert Aumann

Robert John Aumann (Yisrael Aumann, ; born June 8, 1930) is an Israeli-American mathematician, and a member of the United States National Academy of Sciences. He is a professor at the Center for the Study of Rationality in the Hebrew University ...

.

In December 1939, when Sacks was six years old, he and his older brother Michael were evacuated from London to escape the Blitz

The Blitz (English: "flash") was a Nazi Germany, German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom, for eight months, from 7 September 1940 to 11 May 1941, during the Second World War.

Towards the end of the Battle of Britain in 1940, a co ...

, and sent to a boarding school

A boarding school is a school where pupils live within premises while being given formal instruction. The word "boarding" is used in the sense of "room and board", i.e. lodging and meals. They have existed for many centuries, and now extend acr ...

in the English Midlands

The Midlands is the central region of England, to the south of Northern England, to the north of southern England, to the east of Wales, and to the west of the North Sea. The Midlands comprises the ceremonial counties of Derbyshire, Herefordshi ...

where he remained until 1943. Unknown to his family, at the school, he and his brother Michael "subsisted on meager rations of turnips and beetroot and suffered cruel punishments at the hands of a sadistic headmaster."Nadine Epstein, (2008)Uncle Xenon: The Element of Oliver Sacks

''Moment Magazine'' This is detailed in his first autobiography, '' Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood''. Beginning with his return home at the age of 10, under his Uncle Dave's tutelage, he became an intensely focused amateur chemist. Later, he attended St Paul's School in London, where he developed lifelong friendships with

Jonathan Miller

Sir Jonathan Wolfe Miller CBE (21 July 1934 – 27 November 2019) was an English theatre and opera director, actor, author, television presenter, comedian and physician. After training in medicine and specialising in neurology in the late 19 ...

and Eric Korn.

Study of medicine

During adolescence he shared an intense interest in biology with these friends, and later came to share his parents' enthusiasm for medicine. He chose to study medicine at university and enteredThe Queen's College, Oxford

The Queen's College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford, England. The college was founded in 1341 by Robert de Eglesfield in honour of Philippa of Hainault, queen of England. It is distinguished by its predominantly neoclassi ...

in 1951. The first half studying medicine at Oxford is pre-clinical, and he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts

A Bachelor of Arts (abbreviated B.A., BA, A.B. or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is the holder of a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the liberal arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts deg ...

(BA) degree in physiology and biology in 1956.

Although not required, Sacks chose to stay on for an additional year to undertake research after he had taken a course by Hugh Macdonald Sinclair

Hugh Macdonald Sinclair, FRCP (4 February 1910 – 22 June 1990) was a medical doctor and researcher into human nutrition. He is most widely known for claiming that what he called " diseases of civilization" such as coronary heart disease, canc ...

. Sacks recalls, "I had been seduced by a series of vivid lectures on the history of medicine and nutrition, given by Sinclair... it was the history of physiology, the ideas and personalities of physiologists, which came to life." Sacks then became involved with the school's Laboratory of Human Nutrition under Sinclair. Sacks focused his research on the patent medicine

A patent medicine (sometimes called a proprietary medicine) is a non-prescription medicine or medicinal preparation that is typically protected and advertised by a trademark and trade name, and claimed to be effective against minor disorders a ...

Jamaica ginger

Jamaica ginger extract, known in the United States by the slang name Jake, was a late 19th-century patent medicine that provided a convenient way to obtain alcohol during the era of Prohibition in the United States, Prohibition, since it conta ...

, a toxic and commonly abused drug known to cause irreversible nerve damage. After devoting months to research he was disappointed by the lack of help and guidance he received from Sinclair. Sacks wrote up an account of his research findings but stopped working on the subject. As a result he became depressed: "I felt myself sinking into a state of quiet but in some ways agitated despair."

His tutor at Queen's and his parents, seeing his lowered emotional state, suggested he extricate himself from academic studies for a period. His parents then suggested he spend the summer of 1955 living on Israeli kibbutz

A kibbutz ( / , ; : kibbutzim / ) is an intentional community in Israel that was traditionally based on agriculture. The first kibbutz, established in 1910, was Degania Alef, Degania. Today, farming has been partly supplanted by other economi ...

Ein HaShofet

Ein HaShofet (, ''lit.'' Spring of the Judge) is a kibbutz in northern Israel. Located in the Menashe Heights region around 25 km southeast of the city of Haifa, close to Yokneam, it falls under the jurisdiction of Megiddo Regional Council ...

, where the physical labour would help him. Sacks later described his experience on the kibbutz as an "anodyne to the lonely, torturing months in Sinclair's lab". He said he lost from his previously overweight body as a result of the healthy, hard physical labour he performed there. He spent time travelling around the country with time spent scuba diving at the Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

port city of Eilat

Eilat ( , ; ; ) is Israel's southernmost city, with a population of , a busy port of Eilat, port and popular resort at the northern tip of the Red Sea, on what is known in Israel as the Gulf of Eilat and in Jordan as the Gulf of Aqaba. The c ...

, and began to reconsider his future: "I wondered again, as I had wondered when I first went to Oxford, whether I really wanted to become a doctor. I had become very interested in neurophysiology, but I also loved marine biology;... But I was 'cured' now; it was time to return to medicine, to start clinical work, seeing patients in London."

In 1956, Sacks began his study of clinical medicine at the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

and Middlesex Hospital Medical School

Middlesex Hospital was a teaching hospital located in the Fitzrovia area of London, England. First opened as the Middlesex Infirmary in 1745 on Windmill Street, it was moved in 1757 to Mortimer Street where it remained until it was finally clo ...

. For the next two-and-a-half years, he took courses in medicine, surgery, orthopaedics, paediatrics, neurology, psychiatry, dermatology, infectious diseases, obstetrics, and various other disciplines. During his years as a student, he helped home-deliver a number of babies. In 1958, he graduated with Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery

A Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (; MBBS, also abbreviated as BM BS, MB ChB, MB BCh, or MB BChir) is a medical degree granted by medical schools or universities in countries that adhere to the United Kingdom's higher education trad ...

(BM BCh) degrees, and, as was usual at Oxford, his BA was later promoted to a Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA or AM) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Those admitted to the degree have ...

(MA Oxon) degree.

Having completed his medical degree, Sacks began his pre-registration house officer

Pre-registration house officer (PRHO), commonly referred to as house officer and less commonly as houseman, is a former official term for a grade of junior doctor that was, until 2005, the only job open to medical graduates in the United Kingdom ...

rotations at Middlesex Hospital

Middlesex Hospital was a teaching hospital located in the Fitzrovia area of London, England. First opened as the Middlesex Infirmary in 1745 on Windmill Street, it was moved in 1757 to Mortimer Street where it remained until it was finally clos ...

the following month. "My eldest brother, Marcus, had trained at the Middlesex," he said, "and now I was following his footsteps." Before beginning his house officer post, he said he first wanted some hospital experience to gain more confidence, and took a job at a hospital in St Albans

St Albans () is a cathedral city in Hertfordshire, England, east of Hemel Hempstead and west of Hatfield, Hertfordshire, Hatfield, north-west of London, south-west of Welwyn Garden City and south-east of Luton. St Albans was the first major ...

where his mother had worked as an emergency surgeon during the war. He then did his first six-month post in Middlesex Hospital's medical unit, followed by another six months in its neurological unit. He completed his pre-registration year in June 1960, but was uncertain about his future.

Beginning life in North America

Sacks left Britain and flew to Montreal, Canada, on 9 July 1960, his 27th birthday. He visited the

Sacks left Britain and flew to Montreal, Canada, on 9 July 1960, his 27th birthday. He visited the Montreal Neurological Institute

The McGill University Health Centre (MUHC; ) is one of two major healthcare networks in the city of Montreal, Quebec. It is affiliated with McGill University and one of the largest medical complexes in Montreal. It is the largest hospital system i ...

and the Royal Canadian Air Force

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF; ) is the air and space force of Canada. Its role is to "provide the Canadian Forces with relevant, responsive and effective airpower". The RCAF is one of three environmental commands within the unified Can ...

(RCAF), telling them that he wanted to be a pilot. After some interviews and checking his background, they told him he would be best in medical research. But as he kept making mistakes, including losing data from several months of research, destroying irreplaceable slides, and losing biological samples, his supervisors had second thoughts about him. Dr. Taylor, the head medical officer, told him, "You are clearly talented and we would love to have you, but I am not sure about your motives for joining." He was told to travel for a few months and reconsider. He used the next three months to travel across Canada and deep into the Canadian Rockies, which he described in his personal journal, later published as ''Canada: Pause, 1960''.

In 1961 he arrived in the United States, completing an internship

An internship is a period of work experience offered by an organization for a limited period of time. Once confined to medical graduates, internship is used to practice for a wide range of placements in businesses, non-profit organizations and g ...

at Mt. Zion Hospital in San Francisco and a residency

Residency may refer to:

* Artist-in-residence, a program to sponsor the residence and work of visual artists, writers, musicians, etc.

* Concert residency, a series of concerts performed at one venue

* Domicile (law), the act of establishing or m ...

in neurology and neuropathology at UCLA

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California, United States. Its academic roots were established in 1881 as a normal school then known as the southern branch of the C ...

. While in San Francisco, Sacks became a lifelong close friend of poet Thom Gunn

Thomson William "Thom" Gunn (29 August 1929 – 25 April 2004) was an English poet who was praised for his early verses in England, where he was associated with Movement (literature), The Movement, and his later poetry in America, where he adop ...

, saying he loved his wild imagination, his strict control, and perfect poetic form. During much of his time at UCLA, he lived in a rented house in Topanga Canyon

Topanga (Tongva: ''Topaa'nga'') is an unincorporated community in western Los Angeles County, California, United States. Located in the Santa Monica Mountains, the community exists in Topanga Canyon and the surrounding hills. The narrow southern ...

and experimented with various recreational drugs

Recreation is an activity of leisure, leisure being discretionary time. The "need to do something for recreation" is an essential element of human biology and psychology. Recreational activities are often done for enjoyment, amusement, or plea ...

. He described some of his experiences in a 2012 ''New Yorker

New Yorker may refer to:

* A resident of New York:

** A resident of New York City and its suburbs

*** List of people from New York City

** A resident of the New York (state), State of New York

*** Demographics of New York (state)

* ''The New Yor ...

'' article, and in his book ''Hallucinations

A hallucination is a perception in the absence of an external stimulus that has the compelling sense of reality. They are distinguishable from several related phenomena, such as dreaming ( REM sleep), which does not involve wakefulness; pse ...

''. During his early career in California and New York City he indulged in:

He wrote that after moving to New York City, an amphetamine

Amphetamine (contracted from Alpha and beta carbon, alpha-methylphenethylamine, methylphenethylamine) is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant that is used in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), narcolepsy, an ...

-facilitated epiphany that came as he read a book by the 19th-century migraine

Migraine (, ) is a complex neurological disorder characterized by episodes of moderate-to-severe headache, most often unilateral and generally associated with nausea, and light and sound sensitivity. Other characterizing symptoms may includ ...

doctor Edward Liveing inspired him to chronicle his observations on neurological diseases and oddities; to become the "Liveing of our Time". Though he was a United States resident for the rest of his life, he never became a citizen. He told ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'' in a 2005 interview, "In 1961, I declared my intention to become a United States citizen, which may have been a genuine intention, but I never got round to it. I think it may go with a slight feeling that this was only an extended visit. I rather like the words 'resident alien'. It's how I feel. I'm a sympathetic, resident, sort of visiting alien."

Career

Sacks served as an instructor and later professor of clinical neurology at

Sacks served as an instructor and later professor of clinical neurology at Yeshiva University

Yeshiva University is a Private university, private Modern Orthodox Judaism, Orthodox Jewish university with four campuses in New York City.

's Albert Einstein College of Medicine

The Albert Einstein College of Medicine is a Private university, private medical school in New York City. Founded in 1953, Einstein is an independent degree-granting institution within the Montefiore Einstein Health System.

Einstein hosts Doc ...

from 1966 to 2007, and also held an appointment at the New York University School of Medicine

The New York University Grossman School of Medicine is a medical school of New York University, a private research university in New York City. It was founded in 1841 and is one of two medical schools of the university, the other being the NYU G ...

from 1992 to 2007. In July 2007 he joined the faculty of Columbia University Medical Center

Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC) is the academic medical center of Columbia University and the largest campus of NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital. The center's academic wing consists of Columbia's colleges and schools of Physicia ...

as a professor of neurology and psychiatry

Psychiatry is the medical specialty devoted to the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of deleterious mental disorder, mental conditions. These include matters related to cognition, perceptions, Mood (psychology), mood, emotion, and behavior.

...

. At the same time he was appointed Columbia University's first "Columbia University Artist" at the university's Morningside Heights

Morningside Heights is a neighborhood on the West Side of Upper Manhattan in New York City. It is bounded by Morningside Drive to the east, 125th Street to the north, 110th Street to the south, and Riverside Drive to the west. Morningsi ...

campus, recognising the role of his work in bridging the arts and sciences. He was also a visiting professor at the University of Warwick

The University of Warwick ( ; abbreviated as ''Warw.'' in post-nominal letters) is a public research university on the outskirts of Coventry between the West Midlands and Warwickshire, England. The university was founded in 1965 as part of ...

in the UK."NYU Langone Medical Center Welcomes Neurologist and Author Oliver Sacks, MD". Newswise.com. 13 September 2012. He returned to New York University School of Medicine in 2012, serving as a professor of neurology and consulting neurologist in the school's epilepsy centre. Sacks's work at Beth Abraham Hospital helped provide the foundation on which the

Institute for Music and Neurologic Function

The Institute for Music and Neurologic Function (IMNF) is a US nonprofit organization conducting research into and applying music therapy. It is located in Mount Vernon, New York.

Mission

The mission of the institute is to develop and apply mu ...

(IMNF) is built; Sacks was an honorary medical advisor. The Institute honoured Sacks in 2000 with its first ''Music Has Power Award''. The IMNF again bestowed a ''Music Has Power Award'' on him in 2006 to commemorate "his 40 years at Beth Abraham and honour his outstanding contributions in support of music therapy

Music therapy, an allied health profession, "is the clinical and evidence-based use of music interventions to accomplish individualized goals within a therapeutic relationship by a credentialed professional who has completed an approved music t ...

and the effect of music on the human brain and mind."

Sacks maintained a busy hospital-based practice in New York City. He accepted a very limited number of private patients, in spite of being in great demand for such consultations. He served on the boards of The Neurosciences Institute

The Neurosciences Institute (NSI) was a small, nonprofit scientific research organization that investigated basic issues in neuroscience.

Active mainly between 1981 and 2012, NSI sponsored theoretical, computational, and experimental work on cons ...

and the New York Botanical Garden

The New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) is a botanical garden at Bronx Park in the Bronx, New York City. Established in 1891, it is located on a site that contains a landscape with over one million living plants; the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory, ...

.

Writing

In 1967 Sacks first began to write of his experiences with some of his neurological patients. He burned his first such book, ''Ward 23'', during an episode of self-doubt. His books have been translated into over 25 languages. In addition, Sacks was a regular contributor to ''The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. It was founded on February 21, 1925, by Harold Ross and his wife Jane Grant, a reporter for ''The New York T ...

'', ''the New York Review of Books

''The New York Review of Books'' (or ''NYREV'' or ''NYRB'') is a semi-monthly magazine with articles on literature, culture, economics, science and current affairs. Published in New York City, it is inspired by the idea that the discussion of ...

'', ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'', ''London Review of Books

The ''London Review of Books'' (''LRB'') is a British literary magazine published bimonthly that features articles and essays on fiction and non-fiction subjects, which are usually structured as book reviews.

History

The ''London Review of Book ...

'' and numerous other medical, scientific and general publications. He was awarded the Lewis Thomas Prize for Writing about Science in 2001.

Sacks's work is featured in a "broader range of media than those of any other contemporary medical author" and in 1990, ''The New York Times'' wrote he "has become a kind of poet laureate of contemporary medicine".

Sacks considered his literary style to have grown out of the tradition of 19th-century "clinical anecdotes", a literary style that included detailed narrative case histories, which he termed novelistic. He also counted among his inspirations the case histories of the Russian neuropsychologist A. R. Luria, who became a close friend through correspondence from 1973 until Luria's death in 1977.Sacks, O. (2014). Luria and "Romantic Science". In A. Yasnitsky, R. Van der Veer & M. Ferrari (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of cultural-historical psychology

Cultural-historical psychology is a branch of psychological theory and practice associated with Lev Vygotsky and Alexander Luria and their Circle, who initiated it in the mid-1920s–1930s.Yasnitsky, A., van der Veer, R., & Ferrari, M. (Eds.) (20 ...

(517–528). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press After the publication of his first book ''Migraine'' in 1970, a review by his close friend W. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry is noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in tone, ...

encouraged Sacks to adapt his writing style to "be metaphorical, be mythical, be whatever you need."

Sacks described his cases with a wealth of narrative detail, concentrating on the experiences of the patient (in the case of his ''A Leg to Stand On'', the patient was himself). The patients he described were often able to adapt to their situation in different ways although their neurological conditions were usually considered incurable. His book ''Awakenings

''Awakenings'' is a 1990 American biographical drama film written by Steven Zaillian, directed by Penny Marshall, and starring Robert De Niro, Robin Williams, Julie Kavner, Ruth Nelson, John Heard, Penelope Ann Miller, Peter Stormare and Max ...

'', upon which the 1990 feature film of the same name is based, describes his experiences using the new drug levodopa

Levodopa, also known as L-DOPA and sold under many brand names, is a dopaminergic medication which is used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease (PD) and certain other conditions like dopamine-responsive dystonia and restless legs syndrome. ...

on post-encephalitic patients at the Beth Abraham Hospital, later Beth Abraham Center for Rehabilitation and Nursing, in New York. ''Awakenings'' was also the subject of the first documentary, made in 1974, for the British television series ''Discovery

Discovery may refer to:

* Discovery (observation), observing or finding something unknown

* Discovery (fiction), a character's learning something unknown

* Discovery (law), a process in courts of law relating to evidence

Discovery, The Discovery ...

''. Composer and friend of Sacks Tobias Picker

Tobias Picker (born July 18, 1954) is an American composer, pianist, and Conductor (music), conductor, noted for his orchestral works ''Old and Lost Rivers'', ''Keys To The City (orchestral work), Keys To The City'', and ''The Encantadas (orches ...

composed a ballet inspired by ''Awakenings'' for the Rambert Dance Company

Rambert (known as Rambert Dance Company before 2014) is a leading British dance company. Formed at the start of the 20th century as a classical ballet company, it exerted a great deal of influence on the development of dance in the United Kingd ...

, which was premiered by Rambert in Salford

Salford ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city in Greater Manchester, England, on the western bank of the River Irwell which forms its boundary with Manchester city centre. Landmarks include the former Salford Town Hall, town hall, ...

, UK in 2010; In 2022, Picker premiered an opera of Awakenings at Opera Theatre of Saint Louis

Opera Theatre of Saint Louis (OTSL) is an American summer opera festival held in St. Louis, Missouri. Typically four operas, all sung in English, are presented each season, which runs from late May to late June. Performances are accompanied by the ...

.

In his memoir ''A Leg to Stand On'' he wrote about the consequences of a near-fatal accident he had at age 41 in 1974, a year after the publication of ''Awakenings'', when he fell off a cliff and severely injured his left leg while

In his memoir ''A Leg to Stand On'' he wrote about the consequences of a near-fatal accident he had at age 41 in 1974, a year after the publication of ''Awakenings'', when he fell off a cliff and severely injured his left leg while mountaineering

Mountaineering, mountain climbing, or alpinism is a set of outdoor activities that involves ascending mountains. Mountaineering-related activities include traditional outdoor climbing, skiing, and traversing via ferratas that have become mounta ...

alone above Hardangerfjord

The Hardangerfjord () is the fifth longest fjord in the world, and the second longest fjord in Norway. It is located in Vestland county in the Hardanger region. The fjord stretches from the Atlantic Ocean into the mountainous interior of No ...

, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

.

In some of his other books, he describes cases of Tourette syndrome

Tourette syndrome (TS), or simply Tourette's, is a common neurodevelopmental disorder that begins in childhood or adolescence. It is characterized by multiple movement (motor) tics and at least one vocal (phonic) tic. Common tics are blinkin ...

and various effects of Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease (PD), or simply Parkinson's, is a neurodegenerative disease primarily of the central nervous system, affecting both motor system, motor and non-motor systems. Symptoms typically develop gradually and non-motor issues become ...

. The title article of '' The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat'' describes a man with visual agnosia

Visual agnosia is an impairment in recognition of visually presented objects. It is not due to a deficit in vision (acuity, visual field, and scanning), language, memory, or intellect. While cortical blindness results from lesions to primary visua ...

and was the subject of a 1986 opera by Michael Nyman

Michael Laurence Nyman, Order of the British Empire, CBE (born 23 March 1944) is an English composer, pianist, libretto, librettist, musicologist, and filmmaker. He is known for numerous film soundtrack, scores (many written during his lengthy ...

. The book was edited by Kate Edgar, who formed a long-lasting partnership with Sacks, with Sacks later calling her a “mother figure” and saying that he did his best work when she was with him, including ''Seeing Voices, Uncle Tungsten, Musicophilia, and Hallucinations.''

The title article of his book ''An Anthropologist on Mars

''An Anthropologist on Mars: Seven Paradoxical Tales'' is a 1995 book by neurologist Oliver Sacks consisting of seven medical case histories of individuals with neurological conditions such as autism and Tourette syndrome. ''An Anthropologist on ...

'', which won a Polk Award

The George Polk Awards in Journalism are a series of American journalism awards presented annually by Long Island University in New York in the United States. A writer for Idea Lab, a group blog hosted on the website of PBS, described the award ...

for magazine reporting, is about Temple Grandin

Mary Temple Grandin (born August 29, 1947) is an American academic, inventor, and ethologist. She is a prominent proponent of the humane treatment of livestock for slaughter and the author of more than 60 scientific papers on animal behavior. ...

, an autistic

Autism, also known as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by differences or difficulties in social communication and interaction, a preference for predictability and routine, sensory processing di ...

professor. He writes in the book's preface that neurological conditions such as autism "can play a paradoxical role, by bringing out latent powers, developments, evolutions, forms of life that might never be seen, or even be imaginable, in their absence". Sacks's 1989 book '' Seeing Voices'' covers a variety of topics in deaf studies

Deaf studies are academic disciplines concerned with the study of the deaf social life of human groups and individuals. These constitute an interdisciplinary field that integrates contents, critiques, and methodologies from anthropology, cultural ...

. The romantic drama film '' At First Sight'' (1999) was based on the essay "To See and Not See" in ''An Anthropologist on Mars''. Sacks also has a small role in the film as a reporter.

In his book '' The Island of the Colorblind'' Sacks wrote about an island where many people have achromatopsia

Achromatopsia, also known as rod monochromacy, is a medical syndrome that exhibits symptoms relating to five conditions, most notably monochromacy. Historically, the name referred to monochromacy in general, but now typically refers only to an aut ...

(total colourblindness, very low visual acuity and high photophobia

Photophobia is a medical symptom of abnormal intolerance to visual perception of light. As a medical symptom, photophobia is not a morbid fear or phobia, but an experience of discomfort or pain to the eyes due to light exposure or by presence o ...

). The second section of this book, titled ''Cycad Island'', describes the Chamorro people

The Chamorro people (; also Chamoru) are the Indigenous peoples of Oceania, Indigenous people of the Mariana Islands, politically divided between the Territories of the United States, United States territory of Guam and the encompassing Norther ...

of Guam

Guam ( ; ) is an island that is an Territories of the United States, organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. Guam's capital is Hagåtña, Guam, Hagåtña, and the most ...

, who have a high incidence of a neurodegenerative disease locally known as lytico-bodig disease

Lytico-Bodig (also Lytigo-bodig) disease, Guam disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-parkinsonism-dementia complex (ALS-PDC), and Western Pacific amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-parkinsonism-dementia complex is a rare, terminal neurodegenerative dis ...

(a devastating combination of ALS

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as motor neuron disease (MND) or—in the United States—Lou Gehrig's disease (LGD), is a rare, terminal neurodegenerative disorder that results in the progressive loss of both upper and low ...

, dementia

Dementia is a syndrome associated with many neurodegenerative diseases, characterized by a general decline in cognitive abilities that affects a person's ability to perform activities of daily living, everyday activities. This typically invo ...

and parkinsonism

Parkinsonism is a clinical syndrome characterized by tremor, bradykinesia (slowed movements), Rigidity (neurology), rigidity, and balance disorder, postural instability.

Both hypokinetic features (bradykinesia and akinesia) and hyperkinetic f ...

). Later, along with Paul Alan Cox

Paul Alan Cox is an American ethnobotanist whose scientific research focuses on discovering new medicines by studying patterns of wellness and illness among indigenous peoples. Cox was born in Salt Lake City in 1953.

Education

After receiving h ...

, Sacks published papers suggesting a possible environmental cause for the disease, namely the toxin beta-methylamino L-alanine (BMAA) from the cycad

Cycads are seed plants that typically have a stout and woody (ligneous) trunk (botany), trunk with a crown (botany), crown of large, hard, stiff, evergreen and (usually) pinnate leaves. The species are dioecious, that is, individual plants o ...

nut accumulating by biomagnification

Biomagnification, also known as bioamplification or biological magnification, is the increase in concentration of a substance, e.g a pesticide, in the tissue (biology), tissues of organisms at successively higher levels in a food chain. This inc ...

in the flying fox bat.

In November 2012 Sacks's book ''Hallucinations

A hallucination is a perception in the absence of an external stimulus that has the compelling sense of reality. They are distinguishable from several related phenomena, such as dreaming ( REM sleep), which does not involve wakefulness; pse ...

'' was published. In it he examined why ordinary people can sometimes experience hallucinations and challenged the stigma associated with the word. He explained: "Hallucinations don't belong wholly to the insane. Much more commonly, they are linked to sensory deprivation, intoxication, illness or injury." He also considers the less well known Charles Bonnet syndrome

Visual release hallucinations, also known as Charles Bonnet syndrome or CBS, are a type of psychophysical visual disturbance in which a person with partial or severe blindness experiences visual hallucinations.

First described by Charles Bonnet ...

, sometimes found in people who have lost their eyesight. The book was described by ''Entertainment Weekly

''Entertainment Weekly'' (sometimes abbreviated as ''EW'') is an American online magazine, digital-only entertainment magazine based in New York City, published by Dotdash Meredith, that covers film, television, music, Broadway theatre, books, ...

'' as: "Elegant... An absorbing plunge into a mystery of the mind."

Sacks sometimes faced criticism in the medical and disability studies communities. Arthur K. Shapiro

Arthur K. Shapiro, M.D., (January 11, 1923 – June 3, 1995) was an American psychiatrist and expert on Tourette syndrome. His "contributions to the understanding of Tourette syndrome completely changed the prevailing view of this disorder";Do ...

, for instance, an expert on Tourette syndrome

Tourette syndrome (TS), or simply Tourette's, is a common neurodevelopmental disorder that begins in childhood or adolescence. It is characterized by multiple movement (motor) tics and at least one vocal (phonic) tic. Common tics are blinkin ...

, said Sacks's work was "idiosyncratic" and relied too much on anecdotal evidence

Anecdotal evidence (or anecdata) is evidence based on descriptions and reports of individual, personal experiences, or observations, collected in a non- systematic manner.

The term ''anecdotal'' encompasses a variety of forms of evidence. This ...

in his writings. Researcher Makoto Yamaguchi thought Sacks's mathematical explanations, in his study of the numerically gifted savant twins (in ''The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat''), were irrelevant, and questioned Sacks's methods. Although Sacks has been characterised as a "compassionate" writer and doctor, others have felt that he exploited his subjects. Sacks was called "the man who mistook his patients for a literary career" by British academic and disability rights activist Tom Shakespeare

Sir Thomas William Shakespeare, 3rd Baronet, (born 11 May 1966) is an English sociologist and bioethicist. He has achondroplasia and uses a wheelchair.

Early life and education

Son of Sir William Geoffrey Shakespeare, 2nd Baronet, and Su ...

, and one critic called his work "a high-brow freak show

A freak show is an exhibition of biological rarities, referred to in popular culture as "Freak, freaks of nature". Typical features would be physically unusual Human#Anatomy and physiology, humans, such as those uncommonly large or small, t ...

". Sacks responded, "I would hope that a reading of what I write shows respect and appreciation, not any wish to expose or exhibit for the thrill... but it's a delicate business."

He also wrote '' The Mind's Eye'', ''Oaxaca Journal'' and '' On the Move: A Life'' (his second autobiography).

Before his death in 2015 Sacks founded the Oliver Sacks Foundation, a non-profit organization established to increase understanding of the brain through using narrative non-fiction and case histories, with goals that include publishing some of Sacks's unpublished writings, and making his vast amount of unpublished writings available for scholarly study. The first posthumous book of Sacks's writings, ''River of Consciousness'', an anthology of his essays, was published in October 2017. Most of the essays had been previously published in various periodicals or in science-essay-anthology books, but were no longer readily obtainable. Sacks specified the order of his essays in ''River of Consciousness'' prior to his death. Some of the essays focus on repressed memories and other tricks the mind plays on itself. This was followed by a collection of some of his letters. Sacks was a prolific handwritten-letter correspondent, and never communicated by e-mail.

Honours

In 1996, Sacks became a member of the

In 1996, Sacks became a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

The American Academy of Arts and Letters is a 300-member honor society whose goal is to "foster, assist, and sustain excellence" in American literature, Music of the United States, music, and Visual art of the United States, art. Its fixed number ...

(Literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

). He was named a Fellow

A fellow is a title and form of address for distinguished, learned, or skilled individuals in academia, medicine, research, and industry. The exact meaning of the term differs in each field. In learned society, learned or professional society, p ...

of the New York Academy of Sciences

The New York Academy of Sciences (NYAS), originally founded as the Lyceum of Natural History in January 1817, is a nonprofit professional society based in New York City, with more than 20,000 members from 100 countries. It is the fourth-oldes ...

in 1999. Also in 1999, he became an Honorary Fellow at the Queen's College, Oxford

The Queen's College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford, England. The college was founded in 1341 by Robert de Eglesfield in honour of Philippa of Hainault, queen of England. It is distinguished by its predominantly neoclassi ...

.

In 2000, Sacks received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement

The American Academy of Achievement, colloquially known as the Academy of Achievement, is a nonprofit educational organization that recognizes some of the highest-achieving people in diverse fields and gives them the opportunity to meet one ano ...

. In 2002, he became Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

(Class IV—Humanities and Arts, Section 4—Literature) and he was awarded the 2001 Lewis Thomas Prize

The Lewis Thomas Prize for Writing about Science, named for its first recipient, Lewis Thomas, is an annual literary prize awarded by The Rockefeller University to scientists or physicians deemed to have accomplished a significant literary achiev ...

by Rockefeller University

The Rockefeller University is a Private university, private Medical research, biomedical Research university, research and graduate-only university in New York City, New York. It focuses primarily on the biological and medical sciences and pro ...

. Sacks was also a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians

The Royal College of Physicians of London, commonly referred to simply as the Royal College of Physicians (RCP), is a British professional membership body dedicated to improving the practice of medicine, chiefly through the accreditation of ph ...

(FRCP).

Sacks was awarded honorary doctorates from Georgetown University

Georgetown University is a private university, private Jesuit research university in Washington, D.C., United States. Founded by Bishop John Carroll (archbishop of Baltimore), John Carroll in 1789, it is the oldest Catholic higher education, Ca ...

(1990), College of Staten Island

The College of Staten Island (CSI) is a public university in Staten Island, New York, United States. It is one of the 11 four-year senior colleges within the City University of New York system.

Programs in the liberal arts and sciences and pro ...

(1991), Tufts University

Tufts University is a private research university in Medford and Somerville, Massachusetts, United States, with additional facilities in Boston and Grafton, as well as Talloires, France. Tufts also has several Doctor of Physical Therapy p ...

(1991), New York Medical College

New York Medical College (NYMC or New York Med) is a Private university, private medical school in Valhalla, New York. Founded in 1860, it is a member of the Touro University System.

NYMC offers advanced degrees through its three schools: the ...

(1991), Medical College of Pennsylvania

Drexel University College of Medicine is the medical school of Drexel University, a private research university in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The medical school represents the consolidation of two medical schools: Hahnemann Medical College, orig ...

(1992), Bard College

Bard College is a private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. The campus overlooks the Hudson River and Catskill Mountains within the Hudson River Historic District ...

(1992), Queen's University at Kingston

Queen's University at Kingston, commonly known as Queen's University or simply Queen's, is a public university, public research university in Kingston, Ontario, Kingston, Ontario, Canada. Queen's holds more than of land throughout Ontario and ...

(2001), Gallaudet University

Gallaudet University ( ) is a private federally chartered university in Washington, D.C., for the education of the deaf and hard of hearing. It was founded in 1864 as a grammar school for both deaf and blind children. It was the first school ...

(2005), Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú

Pontifical Catholic University of Peru (, PUCP) is a private university in Lima, Peru. It was founded in 1917 with the support and approval of the Catholic church, being the oldest private institution of higher learning in the country.

The Peru ...

(2006) and Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) is a private, non-profit institution with research programs focusing on cancer, neuroscience, botany, genomics, and quantitative biology. It is located in Laurel Hollow, New York, in Nassau County, on ...

(2008).

Oxford University

The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the second-oldest continuously operating u ...

awarded him an honorary

An honorary position is one given as an honor, with no duties attached, and without payment. Other uses include:

* Honorary Academy Award, by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, United States

* Honorary Aryan, a status in Nazi Germany ...

Doctor of Civil Law

Doctor of Civil Law (DCL; ) is a degree offered by some universities, such as the University of Oxford, instead of the more common Doctor of Laws (LLD) degrees.

At Oxford, the degree is a higher doctorate usually awarded on the basis of except ...

degree in June 2005.

Sacks received the position "Columbia Artist" from Columbia University in 2007, a post that was created specifically for him and that gave him unconstrained access to the university, regardless of department or discipline.

On 26 November 2008, Sacks was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding valuable service in a wide range of useful activities. It comprises five classes of awards across both civil and military divisions, the most senior two o ...

(CBE), for services to medicine, in the Queen's Birthday Honours

The Birthday Honours, in some Commonwealth realms, mark the King's Official Birthday, reigning monarch's official birthday in each realm by granting various individuals appointment into Order (honour), national or Dynastic order of knighthood, dy ...

.

The minor planet 84928 Oliversacks, discovered in 2003, was named in his honour.

In February 2010, Sacks was named as one of the Freedom From Religion Foundation

The Freedom From Religion Foundation (FFRF) is an American nonprofit organization that advocates for atheism, atheists, agnosticism, agnostics, and nontheism, nontheists.

Formed in 1976, FFRF promotes the separation of church and state, and ch ...

's Honorary Board of distinguished achievers. He described himself as "an old Jewish atheist", a phrase borrowed from his friend Jonathan Miller

Sir Jonathan Wolfe Miller CBE (21 July 1934 – 27 November 2019) was an English theatre and opera director, actor, author, television presenter, comedian and physician. After training in medicine and specialising in neurology in the late 19 ...

.

Personal life

Sacks never married and lived alone for most of his life. He declined to share personal details until late in his life. He addressed hishomosexuality

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or Human sexual activity, sexual behavior between people of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexu ...

for the first time in his 2015 autobiography ''On the Move: A Life''.Sacks, O. ''On the Move: A Life''. Knopf (2015). Celibate for about 35 years since his forties, in 2008 he began a friendship with writer and ''New York Times'' contributor Bill Hayes. Their friendship slowly evolved into a committed long-term partnership that lasted until Sacks's death; Hayes wrote about it in the 2017 memoir '' Insomniac City: New York, Oliver, and Me''.

In Lawrence Weschler

Lawrence Weschler (born 1952 in Van Nuys, California) is an American author of works of creative nonfiction.

A graduate of Cowell College of the University of California, Santa Cruz (1974), Weschler was for over twenty years (1981–2002) a staff ...

's biography, ''And How Are You, Dr. Sacks?'', Sacks is described by a colleague as "deeply eccentric". A friend from his days as a medical resident mentions Sacks's need to violate taboos, like drinking blood mixed with milk, and how he frequently took drugs like LSD

Lysergic acid diethylamide, commonly known as LSD (from German ; often referred to as acid or lucy), is a semisynthetic, hallucinogenic compound derived from ergot, known for its powerful psychological effects and serotonergic activity. I ...

and speed

In kinematics, the speed (commonly referred to as ''v'') of an object is the magnitude of the change of its position over time or the magnitude of the change of its position per unit of time; it is thus a non-negative scalar quantity. Intro ...

in the early 1960s. Sacks himself shared personal information about how he got his first orgasm

Orgasm (from Greek , ; "excitement, swelling"), sexual climax, or simply climax, is the sudden release of accumulated sexual excitement during the sexual response cycle, characterized by intense sexual pleasure resulting in rhythmic, involu ...

spontaneously while floating in a swimming pool, and later when he was giving a man a massage. He also admits having "erotic fantasies of all sorts" in a natural history museum he visited often in his youth, many of them about animals, like hippos in the mud.

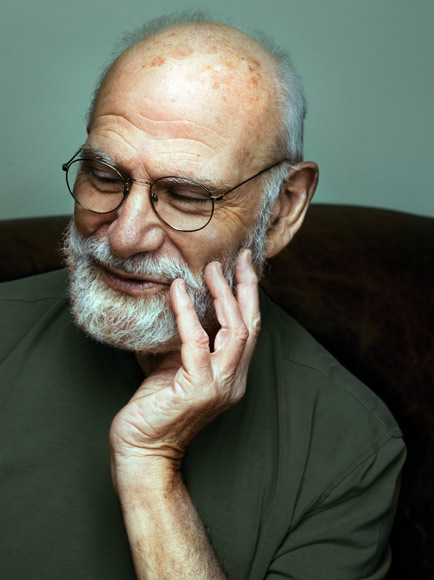

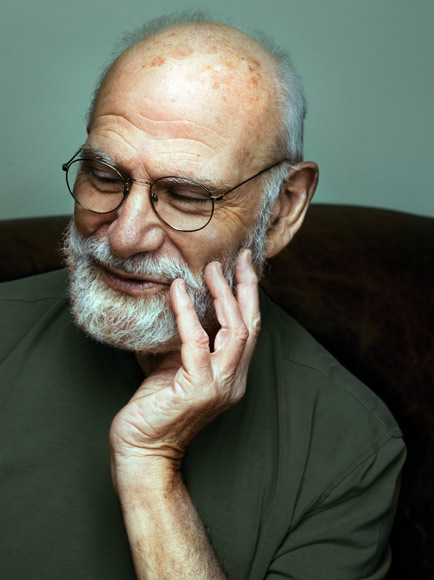

Sacks noted in a 2001 interview that severe shyness, which he described as "a disease", had been a lifelong impediment to his personal interactions. He believed his shyness stemmed from his

Sacks noted in a 2001 interview that severe shyness, which he described as "a disease", had been a lifelong impediment to his personal interactions. He believed his shyness stemmed from his prosopagnosia

Prosopagnosia, also known as face blindness, (" illChoisser had even begun tpopularizea name for the condition: face blindness.") is a cognitive disorder of face perception in which the ability to recognize familiar faces, including one's own f ...

, popularly known as "face blindness", a condition that he studied in some of his patients, including the titular man from his work '' The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat''. This neurological disability of his, whose severity and whose impact on his life Sacks did not fully grasp until he reached middle age, even sometimes prevented him from recognising his own reflection in mirrors.

Sacks swam almost daily for most of his life, beginning when his swimming-champion father started him swimming as an infant. He became well-known for open water swimming

Open water swimming is a swimming discipline which takes place in outdoor bodies of water such as open oceans, lakes, and rivers. Competitive open water swimming is governed by the International Swimming Federation, World Aquatics (formerly kno ...

when he lived in the City Island section of the Bronx

The Bronx ( ) is the northernmost of the five Boroughs of New York City, boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. It shares a land border with Westchester County, New York, West ...

, as he routinely swam around the island or swam vast distances away from the island and back.

He was also an avid powerlifter.

Sacks was a cousin of the Nobel Memorial Economics laureate Robert Aumann

Robert John Aumann (Yisrael Aumann, ; born June 8, 1930) is an Israeli-American mathematician, and a member of the United States National Academy of Sciences. He is a professor at the Center for the Study of Rationality in the Hebrew University ...

.

Illness

Sacks underwentradiation therapy

Radiation therapy or radiotherapy (RT, RTx, or XRT) is a therapy, treatment using ionizing radiation, generally provided as part of treatment of cancer, cancer therapy to either kill or control the growth of malignancy, malignant cell (biology), ...

in 2006 for a uveal melanoma

Uveal melanoma is a type of eye cancer in the uvea of the eye. It is traditionally classed as originating in the iris, choroid, and ciliary body, but can also be divided into class I (low metastatic risk) and class II (high metastatic risk). S ...

in his right eye. He discussed his loss of stereoscopic vision caused by the treatment, which eventually resulted in right-eye blindness, in an article and later in his book '' The Mind's Eye''.

In January 2015, metastases

Metastasis is a pathogenic agent's spreading from an initial or primary site to a different or secondary site within the host's body; the term is typically used when referring to metastasis by a cancerous tumor. The newly pathological sites, ...

from the ocular tumour were discovered in his liver. Sacks announced this development in a February 2015 ''New York Times'' op-ed piece and estimated his remaining time in "months". He expressed his intent to "live in the richest, deepest, most productive way I can". He added: "I want and hope in the time that remains to deepen my friendships, to say farewell to those I love, to write more, to travel if I have the strength, to achieve new levels of understanding and insight."

Death and legacy

Sacks died from cancer on 30 August 2015, at his home inManhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

at the age of 82, surrounded by his closest friends.

In his obituary in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' he was described as "a man of contradictions: candid and guarded, gregarious and solitary, clinical and compassionate, scientific and poetic, British and almost American. 'In 1961, I declared my intention to become a United States citizen, which may have been a genuine intention, but I never got round to it,' he told ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'' in 2005."

The 2019 documentary '' Oliver Sacks: His Own Life'' by Ric Burns

Ric Burns (Eric Burns, born 1955) is an American documentary filmmaker and writer. He has written, directed and produced historical documentaries since the 1990s, beginning with his collaboration on the celebrated PBS series '' The Civil War'' (1 ...

was based on "the most famous neurologist" Sacks; it noted that during his lifetime neurology resident applicants often said that they had chosen neurology after reading Sacks's works. The film includes documents from Sacks's archive.

In 2019, A. A. Knopf

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. () is an American publishing house that was founded by Blanche Knopf and Alfred A. Knopf Sr. in 1915. Blanche and Alfred traveled abroad regularly and were known for publishing European, Asian, and Latin American writers ...

signed a contract with the historian and biographer Laura J. Snyder

Laura J. Snyder (born 1964) is an American historian, philosopher, and writer. She is a Fulbright Scholar, is a Life Member of Clare Hall, Cambridge, was the firsLeon Levy/Alfred P. Sloan fellowaThe Leon Levy Center for Biographyat The Graduate C ...

to write a biography of Sacks based on exclusive access to his archive.

In 2024, the New York Public Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second-largest public library in the United States behind the Library of Congress a ...

announced that it had acquired Sacks's archive, including 35,000 letters, 7,000 photographs, manuscripts of his books, and journals and notebooks. In 2024, Alfred A. Knopf

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. () is an American publishing house that was founded by Blanche Knopf and Alfred A. Knopf Sr. in 1915. Blanche and Alfred traveled abroad regularly and were known for publishing European, Asian, and Latin American writers ...

published a collection of his letters, edited by Kate Edgar.

Bibliography

Books

* ''Migraine

Migraine (, ) is a complex neurological disorder characterized by episodes of moderate-to-severe headache, most often unilateral and generally associated with nausea, and light and sound sensitivity. Other characterizing symptoms may includ ...

'' (1970)

* ''Awakenings

''Awakenings'' is a 1990 American biographical drama film written by Steven Zaillian, directed by Penny Marshall, and starring Robert De Niro, Robin Williams, Julie Kavner, Ruth Nelson, John Heard, Penelope Ann Miller, Peter Stormare and Max ...

'' (1973)

* '' A Leg to Stand On'' (1984)

* '' The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat'' (1985)

* '' Seeing Voices: A Journey Into the World of the Deaf'' (1989)

* ''An Anthropologist on Mars

''An Anthropologist on Mars: Seven Paradoxical Tales'' is a 1995 book by neurologist Oliver Sacks consisting of seven medical case histories of individuals with neurological conditions such as autism and Tourette syndrome. ''An Anthropologist on ...

'' (1995)

* '' The Island of the Colorblind'' (1997)

* '' Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood'' (2001) (first autobiography)

* ''Oaxaca Journal'' (2002) ( travelogue of Sacks's ten-day trip with the American Fern Society

The American Fern Society was founded in 1893. Today, it has more than 1,000 members around the world, with various local chapters. Among its deceased members, perhaps the most famous is Oliver Sacks, who became a member in 1993.

Willard N. Clut ...

to Oaxaca

Oaxaca, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Oaxaca, is one of the 32 states that compose the political divisions of Mexico, Federative Entities of the Mexico, United Mexican States. It is divided into municipalities of Oaxaca, 570 munici ...

, Mexico, 2000)

* '' Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain'' (2007)

* '' The Mind's Eye'' (2010)

* ''Hallucinations

A hallucination is a perception in the absence of an external stimulus that has the compelling sense of reality. They are distinguishable from several related phenomena, such as dreaming ( REM sleep), which does not involve wakefulness; pse ...

'' (2012)

* '' On the Move: A Life'' (2015) (second autobiography)

* ''Gratitude'' (2015) (published posthumously)

* ''NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity'' by Steve Silberman

Stephen Louis Silberman (December 23, 1957 – August 29, 2024) was an American writer for ''Wired (magazine), Wired'' magazine and was an editor and contributor there for more than two decades. In 2010, Silberman was awarded the American Associ ...

(2015) (foreword by Sacks)

* ''Oliver Sacks: The Last Interview and Other Conversations'' (2016) (a collection of interviews)

* '' The River of Consciousness'' (2017)

* ''Everything in Its Place: First Loves and Last Tales'' (2019)

* ''Letters'' (2024)

Articles

* * Online version is titled "How Much a Dementia Patient Needs to Know" and is dated 25 February 2019.Notes

References

Further reading

*Simon Callow

Simon Phillip Hugh Callow (born 15 June 1949) is an English actor. Known as a character actor on stage and screen, he has received numerous accolades including an Olivier Award and Screen Actors Guild Award as well as nominations for two BAFT ...

, "Truth, Beauty, and Oliver Sacks" (review of Oliver Sacks, ''Everything in Its Place: First Loves and Last Tales'', Knopf, 2019, 274 pp.), ''The New York Review of Books

''The New York Review of Books'' (or ''NYREV'' or ''NYRB'') is a semi-monthly magazine with articles on literature, culture, economics, science and current affairs. Published in New York City, it is inspired by the idea that the discussion of ...

'', vol. LXVI, no. 10 (6 June 2019), pp. 4, 6, 8. Oliver Sacks wrote in his public farewell in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'': "Above all, I have been a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet, and that in itself has been an enormous privilege and adventure." (p. 8.)

* Bill Hayes: ''Insomniac city : New York, Oliver Sacks, and me'', London; Oxford; New York; New Delhi; Sydney : Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018,

External links

* * *Oliver Sacks Biography and Interview on American Academy of Achievement

Multimedia

* * * * * * * * *Archived aGhostarchive

and th

Wayback Machine

Interview with Dempsey Rice, documentary filmmaker, about Oliver Sacks film

*, a documentary film by

Ric Burns

Ric Burns (Eric Burns, born 1955) is an American documentary filmmaker and writer. He has written, directed and produced historical documentaries since the 1990s, beginning with his collaboration on the celebrated PBS series '' The Civil War'' (1 ...

Publications

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Sacks, Oliver 1933 births 2015 deaths 20th-century atheists 21st-century atheists 20th-century British Jews 21st-century British Jews 20th-century English LGBTQ people 21st-century English LGBTQ people 20th-century English medical doctors 21st-century English medical doctors 20th-century English memoirists 21st-century English memoirists 20th-century British naturalists 21st-century British naturalists Academics of the University of Warwick Albert Einstein College of Medicine faculty Alumni of the Queen's College, Oxford British neurologists Columbia University faculty Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Deaths from cancer in New York (state) Deaths from uveal melanoma English atheists English expatriates in the United States English male non-fiction writers English medical writers English neuroscientists English writers with disabilities Fellows of the Queen's College, Oxford British gay writers Jewish atheists Jewish physicians Gay Jews LGBTQ physicians British LGBTQ scientists English LGBTQ writers Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters Music psychologists New York University Grossman School of Medicine faculty People educated at The Hall School, Hampstead People from Cricklewood Scientists from London The New Yorker people University of California, Los Angeles fellows Writers from the London Borough of Barnet Writers from the London Borough of Brent Writers from the London Borough of Camden Yeshiva University faculty English people of Lithuanian-Jewish descent People from City Island, Bronx People from Greenwich Village Gay academics Gay scientists Jewish English writers British scientists with disabilities Physicians with disabilities LGBTQ writers with disabilities