SM UB-5 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SM ''UB-5'' was a German Type UB I

After work on ''UB-5'' was complete at the Germaniwerft yard, ''UB-5'' was readied for rail shipment. The process of shipping a UB I boat involved breaking the submarine down into what was essentially a knock down kit. Each boat was broken into approximately fifteen pieces and loaded onto eight railway

After work on ''UB-5'' was complete at the Germaniwerft yard, ''UB-5'' was readied for rail shipment. The process of shipping a UB I boat involved breaking the submarine down into what was essentially a knock down kit. Each boat was broken into approximately fifteen pieces and loaded onto eight railway

After ''UB-5''s sister boat pioneered a route around past British

After ''UB-5''s sister boat pioneered a route around past British

submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

or U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

in the Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the ''Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial Navy) was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for ...

() during World War I. She sank five ships during her career and was broken up in Germany in 1919.

''UB-5'' was ordered in October 1914 and was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one ...

at the Germaniawerft

Friedrich Krupp Germaniawerft (often just called Germaniawerft, "Germania (personification), Germania shipyard") was a German shipbuilding company, located in the harbour at Kiel, and one of the largest and most important builders of U-boats for ...

shipyard in Kiel

Kiel ( ; ) is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein. With a population of around 250,000, it is Germany's largest city on the Baltic Sea. It is located on the Kieler Förde inlet of the Ba ...

in November. ''UB-5'' was a little more than in length and displaced between , depending on whether surfaced or submerged. She carried two torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

es for her two bow torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s and was also armed with a deck-mounted machine gun. ''UB-5'' was broken into sections and shipped by rail to Antwerp

Antwerp (; ; ) is a City status in Belgium, city and a Municipalities of Belgium, municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of Antwerp Province, and the third-largest city in Belgium by area at , after ...

for reassembly. She was launched and commission

In-Commission or commissioning may refer to:

Business and contracting

* Commission (remuneration), a form of payment to an agent for services rendered

** Commission (art), the purchase or the creation of a piece of art most often on behalf of anot ...

ed there as SM ''UB-5'' in March 1915."SM" stands for "Seiner Majestät" () and combined with the ''U'' for ''Unterseeboot'' would be translated as ''His Majesty's Submarine''.

''UB-5'' was initially assigned to the Flanders Flotilla in March 1915 and sank five British ships of under the command of Wilhelm Smiths. The U-boat was assigned to the Baltic Flotilla in October 1915, and relegated to a training role from September 1916. At the end of the war, ''UB-5'' was deemed unseaworthy and unable to surrender at Harwich

Harwich is a town in Essex, England, and one of the Haven ports on the North Sea coast. It is in the Tendring district. Nearby places include Felixstowe to the north-east, Ipswich to the north-west, Colchester to the south-west and Clacton-o ...

with the rest of Germany's U-boat fleet. She remained in Germany where she was broken up by Dräger at Lübeck

Lübeck (; or ; Latin: ), officially the Hanseatic League, Hanseatic City of Lübeck (), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 220,000 inhabitants, it is the second-largest city on the German Baltic Sea, Baltic coast and the second-larg ...

, Germany, in 1919.

Design and construction

After theGerman Army

The German Army (, 'army') is the land component of the armed forces of Federal Republic of Germany, Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German together with the German Navy, ''Marine'' (G ...

's rapid advance along the North Sea coast in the earliest stages of World War I, the Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the ''Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial Navy) was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for ...

found itself without suitable submarines that could be operated in the narrow and shallow environment off Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

.Miller, pp. 46–47.Karau, p. 48. Project 34, a design effort begun in mid-August 1914, produced the Type UB I design: a small submarine that could be shipped by rail to a port of operations and quickly assembled. Constrained by railroad size limitations, the UB I design called for a boat about long and displacing about with two torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s.A further refinement of the design—replacing the torpedo tubes with mine chutes but changing little else—evolved into the Type UC I coastal minelaying submarine. See: Miller, p. 458. ''UB-5'' was part of the initial allotment of eight submarines—numbered to —ordered on 15 October from Germaniawerft

Friedrich Krupp Germaniawerft (often just called Germaniawerft, "Germania (personification), Germania shipyard") was a German shipbuilding company, located in the harbour at Kiel, and one of the largest and most important builders of U-boats for ...

of Kiel

Kiel ( ; ) is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein. With a population of around 250,000, it is Germany's largest city on the Baltic Sea. It is located on the Kieler Förde inlet of the Ba ...

, just shy of two months after planning for the class began.Williamson, p. 12.

''UB-5'' was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one ...

by Germaniawerft in Kiel on 22 November. As built, ''UB-5'' was long, abeam, and had a draft

Draft, the draft, or draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a v ...

of . She had a single Daimler 4-cylinder diesel engine

The diesel engine, named after the German engineer Rudolf Diesel, is an internal combustion engine in which Combustion, ignition of diesel fuel is caused by the elevated temperature of the air in the cylinder due to Mechanics, mechanical Compr ...

for surface travel, and a single Siemens-Schuckert

Siemens-Schuckert (or Siemens-Schuckertwerke) was a German electrical engineering company headquartered in Berlin, Erlangen and Nuremberg that was incorporated into the Siemens AG in 1966.

Siemens Schuckert was founded in 1903 when Siemens & H ...

electric motor

An electric motor is a machine that converts electrical energy into mechanical energy. Most electric motors operate through the interaction between the motor's magnetic field and electric current in a electromagnetic coil, wire winding to gene ...

for underwater travel, both attached to a single propeller shaft

A drive shaft, driveshaft, driving shaft, tailshaft (Australian English), propeller shaft (prop shaft), or Cardan shaft (after Girolamo Cardano) is a component for transmitting mechanical power, torque, and rotation, usually used to connect o ...

. Her top speeds were , surfaced, and , submerged. At more moderate speeds, she could sail up to on the surface before refueling, and up to submerged before recharging her batteries. Like all boats of the class, ''UB-5'' was rated to a diving depth of , and could completely submerge in 33 seconds.

''UB-5'' was armed with two torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

es in two bow torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s. She was also outfitted for a single machine gun on deck. ''UB-5''s standard complement consisted of one officer and thirteen enlisted men.Karau, p. 49.

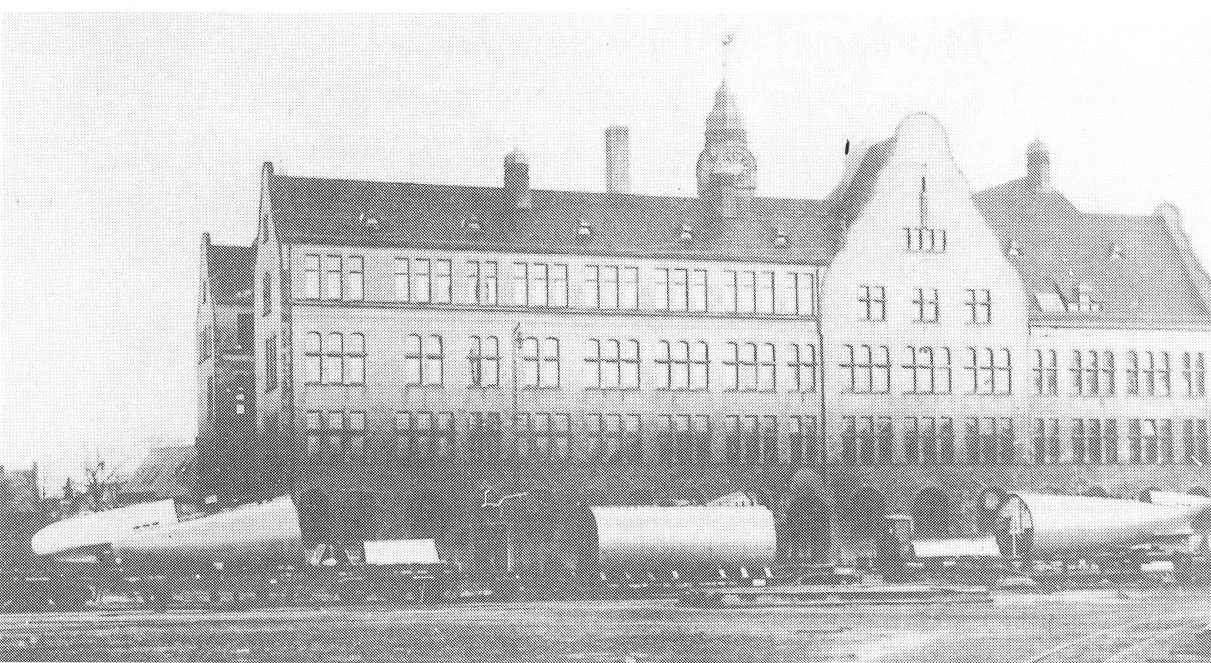

After work on ''UB-5'' was complete at the Germaniwerft yard, ''UB-5'' was readied for rail shipment. The process of shipping a UB I boat involved breaking the submarine down into what was essentially a knock down kit. Each boat was broken into approximately fifteen pieces and loaded onto eight railway

After work on ''UB-5'' was complete at the Germaniwerft yard, ''UB-5'' was readied for rail shipment. The process of shipping a UB I boat involved breaking the submarine down into what was essentially a knock down kit. Each boat was broken into approximately fifteen pieces and loaded onto eight railway flatcar

A flatcar (US) (also flat car, or flatbed) is a piece of rolling stock that consists of an open, flat deck mounted on trucks (US) or bogies (UK) at each end. Occasionally, flat cars designed to carry extra heavy or extra large loads are mounted ...

s. In early 1915, the sections of ''UB-5'' were shipped to Antwerp

Antwerp (; ; ) is a City status in Belgium, city and a Municipalities of Belgium, municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of Antwerp Province, and the third-largest city in Belgium by area at , after ...

for assembly in what was typically a two- to three-week process. After ''UB-5'' was assembled and launched sometime in March, she was loaded on a barge and taken through canals to Bruges

Bruges ( , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the province of West Flanders, in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is in the northwest of the country, and is the sixth most populous city in the country.

The area of the whole city amoun ...

where she underwent trials.

Service career

The submarine wascommission

In-Commission or commissioning may refer to:

Business and contracting

* Commission (remuneration), a form of payment to an agent for services rendered

** Commission (art), the purchase or the creation of a piece of art most often on behalf of anot ...

ed into the German Imperial Navy as SM ''UB-5'' on 25 March under the command of Oberleutnant zur See

(''OLt zS'' or ''OLZS'' in the German Navy, ''Oblt.z.S.'' in the ''Kriegsmarine'') is traditionally the highest rank of Lieutenant in the German Navy. It is grouped as Ranks and insignia of officers of NATO Navies, OF-1 in NATO.

The rank was ...

Wilhelm Smiths, a 28-year-old first-time U-boat commander.Smiths was in the Navy's April 1906 cadet class with 34 other future U-boat captains, including Wilhelm Marschall, Matthias Graf von Schmettow, Max Viebeg, and Erwin Waßner Erwin may refer to:

People Given name

* Erwin Chargaff (1905–2002), Austrian biochemist

* Erwin Chemerinsky (born 1953), American legal scholar

* Erwin Dold (1919–2012), German concentration camp commandant in World War 2

* Erwin Hauer (1926 ...

. See:

''UB-5'' soon joined the other UB I boats then comprising the Flanders Flotilla (), which had been organized on 29 March. When ''UB-5'' joined the flotilla, Germany was in the midst of its first submarine offensive, begun in February. During this campaign, enemy vessels in the German-defined war zone (), which encompassed all waters around the United Kingdom (including the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

), were to be sunk. Vessels of neutral countries were not to be attacked unless they definitively could be identified as enemy vessels operating under a false flag

A false flag operation is an act committed with the intent of disguising the actual source of responsibility and pinning blame on another party. The term "false flag" originated in the 16th century as an expression meaning an intentional misrep ...

.Tarrant, p. 14.

The UB I boats of the Flanders Flotilla were initially limited to patrols in the Hoofden, the southern portion of the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

between the United Kingdom and the Netherlands.Karau, p. 50. ''UB-4'' made the first sortie of the flotilla on 9 April, and ''UB-5'' departed on her first patrol soon after. On 15 April, from the North Hinder lightship, ''UB-5'' scored her first success when she torpedoed and sank the British steamer ''Ptarmigan''. The information on the website is extracted from The 784 GRT steamer was carrying a general cargo from Rotterdam

Rotterdam ( , ; ; ) is the second-largest List of cities in the Netherlands by province, city in the Netherlands after the national capital of Amsterdam. It is in the Provinces of the Netherlands, province of South Holland, part of the North S ...

to London when she went down with the loss of eight crewmen.

After ''UB-5''s sister boat pioneered a route around past British

After ''UB-5''s sister boat pioneered a route around past British anti-submarine net

An anti-submarine net or anti-submarine boom is a boom placed across the mouth of a harbour or a strait for protection against submarines. Net laying ships would be used to place and remove the nets. The US Navy used anti-submarine nets in the ...

s and mines in the Straits of Dover

The Strait of Dover or Dover Strait, historically known as the Dover Narrows, is the strait at the narrowest part of the English Channel, marking the boundary between the Channel and the North Sea, and separating Great Britain from continental ...

in late June, boats of the flotilla began to patrol the western English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

.Karau, p. 51. , ''UB-5'', and soon followed with patrols in the Channel, but were hampered by fog and bad weather.Gibson and Prendergast, p. 50. Even though none of the boats sank any ships, by successfully completing their voyages they helped further prove the feasibility of defeating the British countermeasures in the Straits of Dover.

On 13 and 14 August, while patrolling in Lowestoft

Lowestoft ( ) is a coastal town and civil parish in the East Suffolk (district), East Suffolk district of Suffolk, England.OS Explorer Map OL40: The Broads: (1:25 000) : . As the List of extreme points of the United Kingdom, most easterly UK se ...

–Cromer

Cromer ( ) is a coastal town and civil parish on the north coast of the North Norfolk district of the county of Norfolk, England. It is north of Norwich, northwest of North Walsham and east of Sheringham on the North Sea coastline.

The local ...

area, ''UB-5'' sank four British fishing smacks with a combined tonnage of just over , the largest being ''Sunflower'' and ''J.W.F.T.'', each of ., , , Retrieved on 6 March 2009. All four of the smacks—sailing vessels traditionally rigged with red ochre

Ochre ( ; , ), iron ochre, or ocher in American English, is a natural clay earth pigment, a mixture of ferric oxide and varying amounts of clay and sand. It ranges in colour from yellow to deep orange or brown. It is also the name of the col ...

sails—were stopped, boarded by crewmen from ''UB-5'', and sunk with explosives. The information on the website is extracted from These were the last ships ''UB-5'' sank during the war.

Germany's submarine offensive was suspended on 18 September by the chief of the '' Admiralstab'', Admiral Henning von Holtzendorff

Henning Rudolf Adolf Karl von Holtzendorff (9 January 1853 – 7 June 1919) was a German admiral during World War I, who became famous for his December 1916 memo about unrestricted submarine warfare against the United Kingdom. He was a recipient ...

, In response to American demands after the sinking of the Cunard Line

The Cunard Line ( ) is a British shipping and an international cruise line based at Carnival House at Southampton, England, operated by Carnival UK and owned by Carnival Corporation & plc. Since 2011, Cunard and its four ships have been r ...

steamer in May 1915 and other high-profile sinkings in August and September. Holtzendorff's directive from ordered all U-boats out of the English Channel and the South-Western Approaches and required that all submarine activity in the North Sea be conducted strictly along prize regulations.Tarrant, pp. 21–22. Shortly after this cessation, ''UB-5'' was transferred to the Baltic Flotilla () on 9 October.

Boats of the Baltic flotilla were based at either Kiel, Danzig, or Libau,Tarrant, p. 34. but where ''UB-5'' was stationed during this time is not reported in sources. On 21 September 1916, ''UB-5'' was transferred to training duties. According to authors R.H. Gibson and Maurice Prendergast, submarines assigned to training duties were "war-worn craft" unfit for service.Gibson and Prendergast, p. 57. At the end of the war, the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

required all German U-boats to be sailed to Harwich

Harwich is a town in Essex, England, and one of the Haven ports on the North Sea coast. It is in the Tendring district. Nearby places include Felixstowe to the north-east, Ipswich to the north-west, Colchester to the south-west and Clacton-o ...

for surrender. ''UB-5'' was one of eight U-boats deemed unseaworthy and allowed to remain in Germany.Gibson and Prendergast, pp. 331–32.The other seven boats were , , , , and three fellow Type UB I boats, , , and . ''UB-5'' was broken up by Dräger at Lübeck

Lübeck (; or ; Latin: ), officially the Hanseatic League, Hanseatic City of Lübeck (), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 220,000 inhabitants, it is the second-largest city on the German Baltic Sea, Baltic coast and the second-larg ...

in 1919.

Summary of raiding history

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Ub005 German Type UB I submarines Ships built in Kiel Ships built in Belgium 1915 ships U-boats commissioned in 1915 World War I submarines of Germany