S-50 (Manhattan Project) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The S-50 Project was the

The liquid thermal diffusion process was based on the discovery by Carl Ludwig in 1856 and later Charles Soret in 1879, that when a temperature gradient is maintained in an originally homogeneous

The liquid thermal diffusion process was based on the discovery by Carl Ludwig in 1856 and later Charles Soret in 1879, that when a temperature gradient is maintained in an originally homogeneous

Sites at Watts Bar Dam,

Sites at Watts Bar Dam,

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

's effort to produce enriched uranium

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (23 ...

by liquid thermal diffusion during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. It was one of three technologies for uranium enrichment pursued by the Manhattan Project.

The liquid thermal diffusion process was not one of the enrichment technologies initially selected for use in the Manhattan Project, and was developed independently by Philip H. Abelson and other scientists at the United States Naval Research Laboratory

The United States Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) is the corporate research laboratory for the United States Navy and the United States Marine Corps. Located in Washington, DC, it was founded in 1923 and conducts basic scientific research, appl ...

. This was primarily due to doubts about the process's technical feasibility, but inter-service rivalry between the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

and United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

also played a part.

Pilot plants were built at the Anacostia Naval Air Station and the Philadelphia Navy Yard, and a production facility at the Clinton Engineer Works in Oak Ridge, Tennessee

Oak Ridge is a city in Anderson County, Tennessee, Anderson and Roane County, Tennessee, Roane counties in the East Tennessee, eastern part of the U.S. state of Tennessee, about west of downtown Knoxville, Tennessee, Knoxville. Oak Ridge's po ...

. This was the only production-scale liquid thermal diffusion plant ever built. It could not enrich uranium sufficiently for use in an atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear expl ...

, but it could provide slightly enriched feed for the Y-12 calutron

A calutron is a mass spectrometer originally designed and used for separating the isotopes of uranium. It was developed by Ernest Lawrence during the Manhattan Project and was based on his earlier invention, the cyclotron. Its name was derive ...

s and the K-25 gaseous diffusion

Gaseous diffusion is a technology that was used to produce enriched uranium by forcing gaseous uranium hexafluoride (UF6) through microporous membranes. This produces a slight separation (enrichment factor 1.0043) between the molecules containi ...

plants. It was estimated that the S-50 plant had sped up production of enriched uranium used in the Little Boy

Little Boy was a type of atomic bomb created by the Manhattan Project during World War II. The name is also often used to describe the specific bomb (L-11) used in the bombing of the Japanese city of Hiroshima by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ...

bomb employed in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima by a week.

The S-50 plant ceased production in September 1945, but it was reopened in May 1946, and used by the United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

Nuclear Energy for the Propulsion of Aircraft (NEPA) project. The plant was demolished in the late 1940s.

Background

The discovery of theneutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , that has no electric charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. The Discovery of the neutron, neutron was discovered by James Chadwick in 1932, leading to the discovery of nucle ...

by James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick (20 October 1891 – 24 July 1974) was an English nuclear physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1935 for his discovery of the neutron. In 1941, he wrote the final draft of the MAUD Report, which inspired t ...

in 1932, followed by that of nuclear fission

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radioactiv ...

in uranium

Uranium is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Ura ...

by the German chemists Otto Hahn

Otto Hahn (; 8 March 1879 – 28 July 1968) was a German chemist who was a pioneer in the field of radiochemistry. He is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry and discoverer of nuclear fission, the science behind nuclear reactors and ...

and Fritz Strassmann

Friedrich Wilhelm Strassmann (; 22 February 1902 – 22 April 1980) was a German chemist who, with Otto Hahn in December 1938, identified the element barium as a product of the bombardment of uranium with neutrons. Their observation was the key ...

in 1938, and its theoretical explanation (and naming) by Lise Meitner

Elise Lise Meitner ( ; ; 7 November 1878 – 27 October 1968) was an Austrian-Swedish nuclear physicist who was instrumental in the discovery of nuclear fission.

After completing her doctoral research in 1906, Meitner became the second woman ...

and Otto Robert Frisch

Otto Robert Frisch (1 October 1904 – 22 September 1979) was an Austrian-born British physicist who worked on nuclear physics. With Otto Stern and Immanuel Estermann, he first measured the magnetic moment of the proton. With his aunt, Lise M ...

soon after, opened up the possibility of a nuclear chain reaction

In nuclear physics, a nuclear chain reaction occurs when one single nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more subsequent nuclear reactions, thus leading to the possibility of a self-propagating series or "positive feedback loop" of thes ...

with uranium. Fears that a German atomic bomb project would develop nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear exp ...

s, especially among scientists who were refugees from Nazi Germany and other fascist countries, were expressed in the Einstein-Szilard letter. This prompted preliminary research in the United States in late 1939.

Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (, ; ; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish theoretical physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and old quantum theory, quantum theory, for which he received the No ...

and John Archibald Wheeler

John Archibald Wheeler (July 9, 1911April 13, 2008) was an American theoretical physicist. He was largely responsible for reviving interest in general relativity in the United States after World War II. Wheeler also worked with Niels Bohr to e ...

applied the liquid drop model

In nuclear physics, the semi-empirical mass formula (SEMF; sometimes also called the Weizsäcker formula, Bethe–Weizsäcker formula, or Bethe–Weizsäcker mass formula to distinguish it from the Bethe–Weizsäcker process) is used to approxima ...

of the atomic nucleus

The atomic nucleus is the small, dense region consisting of protons and neutrons at the center of an atom, discovered in 1911 by Ernest Rutherford at the Department_of_Physics_and_Astronomy,_University_of_Manchester , University of Manchester ...

to explain the mechanism of nuclear fission. As the experimental physicists studied fission, they uncovered puzzling results. George Placzek asked Bohr why uranium seemed to fission with both fast and slow neutrons. Walking to a meeting with Wheeler, Bohr had an insight that the fission at low energies was due to the uranium-235

Uranium-235 ( or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exists in nat ...

isotope

Isotopes are distinct nuclear species (or ''nuclides'') of the same chemical element. They have the same atomic number (number of protons in their Atomic nucleus, nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemica ...

, while at high energies it was mainly due to the far more abundant uranium-238

Uranium-238 ( or U-238) is the most common isotope of uranium found in nature, with a relative abundance of 99%. Unlike uranium-235, it is non-fissile, which means it cannot sustain a chain reaction in a thermal-neutron reactor. However, it i ...

isotope. The former makes up 0.714 percent of the uranium atoms in natural uranium, about one in every 140; natural uranium is 99.28 percent uranium-238. There is also a tiny amount of uranium-234

Uranium-234 ( or U-234) is an isotope of uranium. In natural uranium and in uranium ore, 234U occurs as an indirect decay product of uranium-238, but it makes up only 0.0055% (55 parts per million, or 1/18,000) of the raw uranium because its half ...

, 0.006 percent.

At the University of Birmingham

The University of Birmingham (informally Birmingham University) is a Public university, public research university in Birmingham, England. It received its royal charter in 1900 as a successor to Queen's College, Birmingham (founded in 1825 as ...

in Britain, the Australian physicist Mark Oliphant

Sir Marcus Laurence Elwin Oliphant, (8 October 1901 – 14 July 2000) was an Australian physicist and humanitarian who played an important role in the first experimental demonstration of nuclear fusion and in the development of nuclear weapon ...

assigned two refugee physicists—Frisch and Rudolf Peierls

Sir Rudolf Ernst Peierls, (; ; 5 June 1907 – 19 September 1995) was a German-born British physicist who played a major role in Tube Alloys, Britain's nuclear weapon programme, as well as the subsequent Manhattan Project, the combined Allied ...

—the task of investigating the feasibility of an atomic bomb, ironically because their status as enemy aliens precluded their working on secret projects like radar

Radar is a system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), direction ( azimuth and elevation angles), and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It is a radiodetermination method used to detect and track ...

. Their March 1940 Frisch–Peierls memorandum indicated that the critical mass

In nuclear engineering, critical mass is the minimum mass of the fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction in a particular setup. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specific ...

of uranium-235 was within an order of magnitude

In a ratio scale based on powers of ten, the order of magnitude is a measure of the nearness of two figures. Two numbers are "within an order of magnitude" of each other if their ratio is between 1/10 and 10. In other words, the two numbers are ...

of 10 kg, which was small enough to be carried by a bomber

A bomber is a military combat aircraft that utilizes

air-to-ground weaponry to drop bombs, launch aerial torpedo, torpedoes, or deploy air-launched cruise missiles.

There are two major classifications of bomber: strategic and tactical. Strateg ...

of the day. Research into how uranium isotope separation (uranium enrichment

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (23 ...

) could be achieved assumed enormous importance. Frisch's first thought about how this could be achieved was with liquid thermal diffusion.

Liquid thermal diffusion

The liquid thermal diffusion process was based on the discovery by Carl Ludwig in 1856 and later Charles Soret in 1879, that when a temperature gradient is maintained in an originally homogeneous

The liquid thermal diffusion process was based on the discovery by Carl Ludwig in 1856 and later Charles Soret in 1879, that when a temperature gradient is maintained in an originally homogeneous salt

In common usage, salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl). When used in food, especially in granulated form, it is more formally called table salt. In the form of a natural crystalline mineral, salt is also known as r ...

solution, after a time, a concentration gradient will also exist in the solution. This is known as the Soret effect. David Enskog in 1911 and Sydney Chapman in 1916 independently developed the Chapman–Enskog theory, which explained that when a mixture of two gases passes through a temperature gradient, the heavier gas tends to concentrate at the cold end and the lighter gas at the warm end. This was experimentally confirmed by Chapman and F. W. Dootson in 1916.

Since hot gases tend to rise and cool ones tend to fall, this can be used as a means of isotope separation

Isotope separation is the process of concentrating specific isotopes of a chemical element by removing other isotopes. The use of the nuclides produced is varied. The largest variety is used in research (e.g. in chemistry where atoms of "marker" n ...

. This process was first demonstrated by Klaus Clusius and Gerhard Dickel in Germany in 1938, who used it to separate isotopes of neon

Neon is a chemical element; it has symbol Ne and atomic number 10. It is the second noble gas in the periodic table. Neon is a colorless, odorless, inert monatomic gas under standard conditions, with approximately two-thirds the density of ...

. They used an apparatus called a "column", consisting of a vertical tube with a hot wire down the center. In the United States, Arthur Bramley at the United States Department of Agriculture

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is an executive department of the United States federal government that aims to meet the needs of commercial farming and livestock food production, promotes agricultural trade and producti ...

improved on this design by using concentric tubes with different temperatures.

Research and development

Philip H. Abelson was a young physicist who had been awarded hisPhD

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, DPhil; or ) is a terminal degree that usually denotes the highest level of academic achievement in a given discipline and is awarded following a course of graduate study and original research. The name of the deg ...

from the University of California

The University of California (UC) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university, research university system in the U.S. state of California. Headquartered in Oakland, California, Oakland, the system is co ...

on 8 May 1939. He was among the first American scientists to verify nuclear fission, reporting his results in an article submitted to the Physical Review

''Physical Review'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal. The journal was established in 1893 by Edward Nichols. It publishes original research as well as scientific and literature reviews on all aspects of physics. It is published by the Ame ...

in February 1939, and collaborated with Edwin McMillan

Edwin Mattison McMillan (September 18, 1907 – September 7, 1991) was an American physicist credited with being the first to produce a transuranium element, neptunium. For this, he shared the 1951 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Glenn Seaborg.

...

on the discovery of neptunium

Neptunium is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Np and atomic number 93. A radioactivity, radioactive actinide metal, neptunium is the first transuranic element. It is named after Neptune, the planet beyond Uranus in the Solar Syste ...

. Returning to the Carnegie Institution in Washington, D.C., where he had a position, he became interested in isotope separation. In July 1940, Ross Gunn from the United States Naval Research Laboratory

The United States Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) is the corporate research laboratory for the United States Navy and the United States Marine Corps. Located in Washington, DC, it was founded in 1923 and conducts basic scientific research, appl ...

(NRL) showed him a 1939 paper on the subject by Harold Urey

Harold Clayton Urey ( ; April 29, 1893 – January 5, 1981) was an American physical chemist whose pioneering work on isotopes earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1934 for the discovery of deuterium. He played a significant role in the ...

, and Abelson became intrigued by the possibility of using the liquid thermal diffusion process. He began experiments with the process at the Department of Terrestrial Magnetism at the Carnegie Institution. Using potassium chloride

Potassium chloride (KCl, or potassium salt) is a metal halide salt composed of potassium and chlorine. It is odorless and has a white or colorless vitreous crystal appearance. The solid dissolves readily in water, and its solutions have a sa ...

(KCl), potassium bromide

Potassium bromide ( K Br) is a salt, widely used as an anticonvulsant and a sedative in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with over-the-counter use extending to 1975 in the US. Its action is due to the bromide ion ( sodium bromide is equa ...

(KBr), potassium sulfate

Potassium sulfate (US) or potassium sulphate (UK), also called sulphate of potash (SOP), arcanite, or archaically potash of sulfur, is the inorganic compound with formula K2SO4, a white water-soluble solid. It is commonly used in fertilizers, prov ...

() and potassium dichromate

Potassium dichromate is the inorganic compound with the formula . An orange solid, it is used in diverse laboratory and industrial applications. As with all hexavalent chromium compounds, it is chronically harmful to health. It is a crystalline ...

(), he was able to achieve a separation factor of 1.2 (20 percent) of the potassium-39 and potassium-41 isotopes.

The next step was to repeat the experiments with uranium. He studied the process with aqueous solutions of uranium salts, but found that they tended to be hydrolyzed in the column. Only uranium hexafluoride

Uranium hexafluoride, sometimes called hex, is the inorganic compound with the formula . Uranium hexafluoride is a volatile, white solid that is used in enriching uranium for nuclear reactors and nuclear weapons.

Preparation

Uranium dioxide is co ...

() seemed suitable. In September 1940, Abelson approached Ross Gunn and Lyman J. Briggs, the director of the National Bureau of Standards

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is an agency of the United States Department of Commerce whose mission is to promote American innovation and industrial competitiveness. NIST's activities are organized into physical sc ...

, who were both members of the National Defense Research Committee

The National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) was an organization created "to coordinate, supervise, and conduct scientific research on the problems underlying the development, production, and use of mechanisms and devices of warfare" in the U ...

(NDRC) Uranium Committee. The NRL agreed to make $2,500 available to the Carnegie Institution to allow Abelson to continue his work, and in October 1940, Briggs arranged for it to be moved to the Bureau of Standards, where there were better facilities.

Uranium hexafluoride was not readily available, so Abelson devised his own method of producing it in quantity at the NRL, through fluorination of the more easily produced uranium tetrafluoride

Uranium tetrafluoride is the inorganic compound with the formula UF4. It is a green solid with an insignificant vapor pressure and low solubility in water. Uranium in its tetravalent ( uranous) state is important in various technological process ...

at . Initially, this small plant supplied uranium hexafluoride for the research at Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

, the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia, United States. It was founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson and contains his The Lawn, Academical Village, a World H ...

and the NRL. In 1941, Gunn and Abelson placed an order for uranium hexafluoride with the Harshaw Chemical Company in Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Cuyahoga County. Located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is situated across the Canada–United States border, Canada–U.S. maritime border ...

, using Abelson's process. In early 1942, the NDRC awarded Harshaw a contract to build a pilot plant to produce of uranium hexafluoride per day. By the spring of 1942, Harshaw's pilot uranium hexafluoride plant was operational, and DuPont

Dupont, DuPont, Du Pont, duPont, or du Pont may refer to:

People

* Dupont (surname) Dupont, also spelled as DuPont, duPont, Du Pont, or du Pont is a French surname meaning "of the bridge", historically indicating that the holder of the surname re ...

also began experiments with using the process. Demand for uranium hexafluoride soon rose sharply, and Harshaw and DuPont increased production to meet it.

Abelson erected eleven columns at the Bureau of Standards, all approximately in diameter, but ranging from high. Test runs were carried out with potassium salts, and then, in April 1941, with uranium hexafluoride. On 1 June 1941, Abelson became an employee of the NRL, and he moved to the Anacostia Naval Air Station. In September 1941, he was joined by John I. Hoover, who became his deputy. They constructed an experimental plant there with columns. Steam was provided by a gas-fired boiler. They were able to separate isotopes of chlorine

Chlorine is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate between ...

, but the apparatus was ruined in November by the decomposition products of the carbon tetrachloride

Carbon tetrachloride, also known by many other names (such as carbon tet for short and tetrachloromethane, also IUPAC nomenclature of inorganic chemistry, recognised by the IUPAC), is a chemical compound with the chemical formula CCl4. It is a n ...

. The next run indicated 2.5% separation, and it was found that the optimal spacing of the columns was between . Abelson regarded a run on 22 June with a 9.6% result as the first successful test of liquid thermal diffusion with uranium hexafluoride. In July, he was able to achieve 21%.

Relations with the Manhattan Project

The NRL authorized a pilot plant in July 1942, which commenced operation on 15 November. This time they used fourteen columns, with a separation of between them. The pilot plant ran without interruption from 3 to 17 December 1942.Colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

Leslie R. Groves, Jr., who had been designated to take charge of what would become known as the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

(but would not do so for another two days), visited the pilot plant with the Deputy District Engineer of the Manhattan District, Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth D. Nichols on 21 September, and spoke with Gunn and Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a flag officer rank used by English-speaking navies. In most European navies, the equivalent rank is called counter admiral.

Rear admiral is usually immediately senior to commodore and immediately below vice admiral. It is ...

Harold G. Bowen, Sr., the director the NRL. Groves left with the impression that the project was not being pursued with sufficient urgency. The project was expanded, and Nathan Rosen

Nathan Rosen (; March 22, 1909 – December 18, 1995) was an American and Israeli physicist noted for his study on the structure of the hydrogen molecule and his collaboration with Albert Einstein and Boris Podolsky on entangled wave functions and ...

joined the project as a theoretical physicist. Groves visited the pilot plant again on 10 December 1942, this time with Warren K. Lewis, a professor of chemical engineering

Chemical engineering is an engineering field which deals with the study of the operation and design of chemical plants as well as methods of improving production. Chemical engineers develop economical commercial processes to convert raw materials ...

from MIT

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Established in 1861, MIT has played a significant role in the development of many areas of modern technology and sc ...

, and three DuPont employees. In his report Lewis recommended that the work be continued.

The S-1 Executive Committee superseded the Uranium Committee on 19 June 1942, dropping Gunn from its membership in the process. It considered Lewis' report, and passed on its recommendation to Vannevar Bush

Vannevar Bush ( ; March 11, 1890 – June 28, 1974) was an American engineer, inventor and science administrator, who during World War II, World War II headed the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), through which almo ...

, the director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development

The Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) was an agency of the United States federal government created to coordinate scientific research for military purposes during World War II. Arrangements were made for its creation during May ...

(OSRD), of which the S-1 Executive Committee was a part. The relationship between the OSRD and the NRL was not good; Bowen criticised it for diverting funds from the NRL. Bush was mindful of a 17 March 1942 directive from the president, Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

, albeit on his advice, that the navy was to be excluded from the Manhattan Project. He preferred to work with the more congenial Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

, Henry Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and Demo ...

, over whom he had more influence.

James B. Conant

James Bryant Conant (March 26, 1893 – February 11, 1978) was an American chemist, a transformative President of Harvard University, and the first United States Ambassador to West Germany, U.S. Ambassador to West Germany. Conant obtained a ...

, the chairman of the NDRC and the S-1 Executive Committee, was concerned that the navy was running its own nuclear project, but Bush felt that it did no harm. He met with Gunn at Anacostia on 14 January 1943, and explained the situation to him. Gunn responded that the navy was interested in nuclear marine propulsion

Nuclear marine propulsion is Marine propulsion, propulsion of a ship or submarine with heat provided by a nuclear reactor. The power plant heats water to produce steam for a turbine used to turn the ship's propeller through a Transmission (mechani ...

for nuclear submarine

A nuclear submarine is a submarine powered by a nuclear reactor, but not necessarily nuclear-armed.

Nuclear submarines have considerable performance advantages over "conventional" (typically diesel-electric) submarines. Nuclear propulsion ...

s. Liquid thermal diffusion was a viable means of producing enriched uranium, and all he needed was details about nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a Nuclear fission, fission nuclear chain reaction. They are used for Nuclear power, commercial electricity, nuclear marine propulsion, marine propulsion, Weapons-grade plutonium, weapons ...

design, which he knew was being pursued by the Metallurgical Laboratory in Chicago. He was unaware that it had already built Chicago Pile-1

Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1) was the first artificial nuclear reactor. On 2 December 1942, the first human-made self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was initiated in CP-1 during an experiment led by Enrico Fermi. The secret development of the react ...

, a working nuclear reactor. Bush was unwilling to provide the requested data, but arranged with Rear Admiral William R. Purnell, a fellow member of the Military Policy Committee that ran the Manhattan Project, for Abelson's efforts to receive additional support.

The following week, Briggs, Urey, and Eger V. Murphree from the S-1 Executive Committee, along with Karl Cohen and W. I. Thompson from Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company was a Trust (business), corporate trust in the petroleum industry that existed from 1882 to 1911. The origins of the trust lay in the operations of the Standard Oil of Ohio, Standard Oil Company (Ohio), which had been founde ...

, visited the pilot plant at Anacostia. They were impressed with the simplicity of the process, but disappointed that no enriched uranium product had been withdrawn from the plant; production had been calculated by measuring the difference in concentration. They calculated that a liquid thermal diffusion plant capable of producing 1 kg per day of uranium enriched to 90% uranium-235 would require 21,800 columns, each with a separation factor of 30.7%. It would take 18 months to build, assuming the use of the Manhattan Project's overriding priority for materials. This included of scarce copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

for the outer tubes and nickel

Nickel is a chemical element; it has symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive, but large pieces are slo ...

for the inner, which would be required to resist corrosion by the steam and uranium hexafluoride respectively.

The estimated cost of such a plant was around $32.6 million to build and $62,600 per day to run. What killed the proposal was that the plant would require 600 days to reach equilibrium, by which time $72 million would have been spent, which the S-1 Executive Committee rounded up to $75 million. Assuming that work started immediately, and the plant worked as designed, no enriched uranium could be produced before 1946. Murphree suggested that a liquid thermal diffusion plant producing uranium enriched to 10% uranium-235 might be a substitute for the lower stages of a gaseous diffusion

Gaseous diffusion is a technology that was used to produce enriched uranium by forcing gaseous uranium hexafluoride (UF6) through microporous membranes. This produces a slight separation (enrichment factor 1.0043) between the molecules containi ...

plant, but the S-1 Executive Committee decided against this. Between February and July 1943 the Anacostia pilot plant produced of slightly enriched uranium hexafluoride, which was shipped to the Metallurgical Laboratory. In September 1943, the S-1 Executive Committee decided that no more uranium hexafluoride would be allocated to the NRL, although it would exchange enriched uranium hexafluoride for regular uranium hexafluoride. Groves turned down an order from the NRL for additional uranium hexafluoride in October 1943. When it was pointed out that the navy had developed the production process for uranium hexafluoride in the first place, the army reluctantly agreed to fulfil the order.

Philadelphia pilot plant

Abelson's studies indicated that in order to reduce the equilibrium time, he needed to have a much greater temperature gradient. The NRL considered building it at the Naval Engineering Experiment Station inAnnapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland. It is the county seat of Anne Arundel County and its only incorporated city. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east ...

, but this was estimated to cost $2.5 million, which the NRL regarded as too expensive. Other sites were canvassed, and it was decided to build a new pilot plant at the Naval Boiler and Turbine Laboratory (NBTL) at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, where there was space, steam and cooling water, and, perhaps most important of all, engineers with experience with high-pressure steam. The cost was estimated at $500,000. The pilot plant was authorized by Rear Admiral Earle W. Mills, the Assistant Chief of the Bureau of Ships

The United States Navy's Bureau of Ships (BuShips) was established by Congress on 20 June 1940, by a law which consolidated the functions of the Bureau of Construction and Repair (BuC&R) and the Bureau of Engineering (BuEng). The new bureau was ...

on 17 November 1943. Construction commenced on 1 January 1944, and was completed in July. The NBTL was responsible for the design, construction and operation of the steam and cooling water systems, while the NRL dealt with the columns and subsidiary equipment. Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

Thorvald A. Solberg from the Bureau of Ships was project officer.

The Philadelphia pilot plant occupied of space on a site one block west of Broad Street, near the Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and is the longest free-flowing (undammed) river in the Eastern United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock, New York, the river flows for a ...

. The plant consisted of 102 columns, known as a "rack", arranged into a cascade of seven stages. The plant was intended to be able to produce one gram per day of uranium enriched to 6% uranium-235. The outer copper tubes were cooled by water flowing between them and the external 4-inch steel pipes. The inner nickel tubes were heated by high pressure steam at and . Each column therefore held about of uranium hexafluoride. This was driven by vapor pressure; the only working parts were the water pumps. In operation, the rack consumed 11.6 MW of power. Each column was connected to a reservoir of of uranium hexafluoride. Because of the dangers involved in handling uranium hexafluoride, all work with it, such as replenishing the reservoirs from the shipping cylinders, was accomplished in a transfer room. The columns at the Philadelphia plant were operated in parallel instead of in series, so the Philadelphia pilot plant eventually produced over of uranium hexafluoride enriched to 0.86 percent uranium-235, which was handed over to the Manhattan Project. The Philadelphia pilot plant was disposed of in September 1946, with salvageable equipment being returned to the NRL, while the rest was dumped at sea.

Construction

In early 1944, news of the Philadelphia pilot plant reachedRobert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (born Julius Robert Oppenheimer ; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist who served as the director of the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II. He is often ...

, the director of the Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret scientific laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and overseen by the University of California during World War II. It was operated in partnership with the United State ...

. Oppenheimer wrote to Conant on 4 March 1944, and asked for the reports on the liquid thermal diffusion project, which Conant forwarded. Like nearly everyone else, Oppenheimer had been thinking of uranium enrichment in terms of a process to produce weapons grade uranium suitable for use in an atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear expl ...

, but now he considered another option. If the columns at the Philadelphia plant were operated in parallel instead of in series, then it might produce 12 kg per day of uranium enriched to 1 percent. This could be valuable because an electromagnetic enrichment process that could produce one gram of uranium enriched to 40 percent uranium-235 from natural uranium, could produce two grams per day of uranium enriched to 80 percent uranium-235 if the feed was enriched to 1.4 percent uranium-235, double the 0.7 percent of natural uranium. On 28 April, he wrote to Groves, pointing out that "the production of the Y-12 plant could be increased by some 30 or 40 percent, and its enhancement somewhat improved, many months earlier than the scheduled date for K-25 production."

Groves obtained permission from the Military Policy Committee to renew contact with the navy, and on 31 May 1944 he appointed a review committee consisting of Murphree, Lewis, and his scientific advisor, Richard Tolman

Richard Chace Tolman (March 4, 1881 – September 5, 1948) was an American mathematical physicist and physical chemist who made many contributions to statistical mechanics and theoretical cosmology. He was a professor at the California In ...

, to investigate. The review committee visited the Philadelphia pilot plant the following day. They reported that while Oppenheimer was fundamentally correct, his estimates were optimistic. Adding an additional two racks to the pilot plant would take two months, but would not produce enough feed to meet the requirements of the Y-12 electromagnetic plant at the Clinton Engineer Works. They therefore recommended that a full-scale liquid thermal diffusion plant be built. Groves therefore asked Murphree on 12 June for a costing of a production plant capable of producing 50 kg of uranium enriched to between 0.9 and 3.0 percent uranium-235 per day. Murphree, Tolman, Cohen and Thompson estimated that a plant with 1,600 columns would cost $3.5 million. Groves approved its construction on 24 June 1944, and informed the Military Policy Committee that it would be operational by 1 January 1945.

Sites at Watts Bar Dam,

Sites at Watts Bar Dam, Muscle Shoals

Muscle Shoals is the largest city in Colbert County, Alabama, United States. It is located on the left bank of the Tennessee River in the northern part of the state and, as of the 2010 census, its population was 13,146. The estimated popula ...

and Detroit

Detroit ( , ) is the List of municipalities in Michigan, most populous city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is situated on the bank of the Detroit River across from Windsor, Ontario. It had a population of 639,111 at the 2020 United State ...

were considered, but it was decided to build it at the Clinton Engineer Works, where water could be obtained from the Clinch River

The Clinch River is a river that flows southwest for more than through the Great Appalachian Valley in the U.S. states of Virginia and Tennessee, gathering various tributaries, including the Powell River, before joining the Tennessee River in ...

and steam from the K-25 powerhouse. The thermal diffusion project was codenamed S-50. An S-50 Division was created at the Manhattan District headquarters in June under Lieutenant Colonel Mark C. Fox, with Major Thomas J. Evans, Jr., as his assistant with special authority for plant construction. Groves selected the H. K. Ferguson Company of Cleveland

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is situated across the Canada–U.S. maritime border and approximately west of the Ohio-Pennsylvania st ...

, Ohio, as the prime construction contractor on its record of finishing jobs on time, notably the Gulf Ordnance Plant in Mississippi, on a cost plus fixed fee contract. The H. A. Jones Construction Company would build the steam plant, with H. K. Ferguson as engineer-architect. Although his advisors had estimated that it would take six months to build the plant, Groves gave H. K. Ferguson just four, and he wanted operations to commence in just 75 days.

Groves, Tolman, Fox, and Wells N. Thompson from H. K. Ferguson, collected blueprints of the Philadelphia pilot from there on 26 June. The production plant would consist of twenty-one 102-column racks, arranged in three groups of seven, a total of 2,142 columns. Each rack was a copy of the Philadelphia pilot plant. The columns had to be manufactured to fine tolerances; ± for the diameter of the inner nickel tubes, and ± between the inner nickel tubes and the outer copper tubes. The first orders for columns were placed on 5 July. Twenty-three companies were approached, and the Grinnell Company of Providence, Rhode Island

Providence () is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Rhode Island, most populous city of the U.S. state of Rhode Island. The county seat of Providence County, Rhode Island, Providence County, it is o ...

, and the Mehring and Hanson Company of Washington, D.C., accepted the challenge.

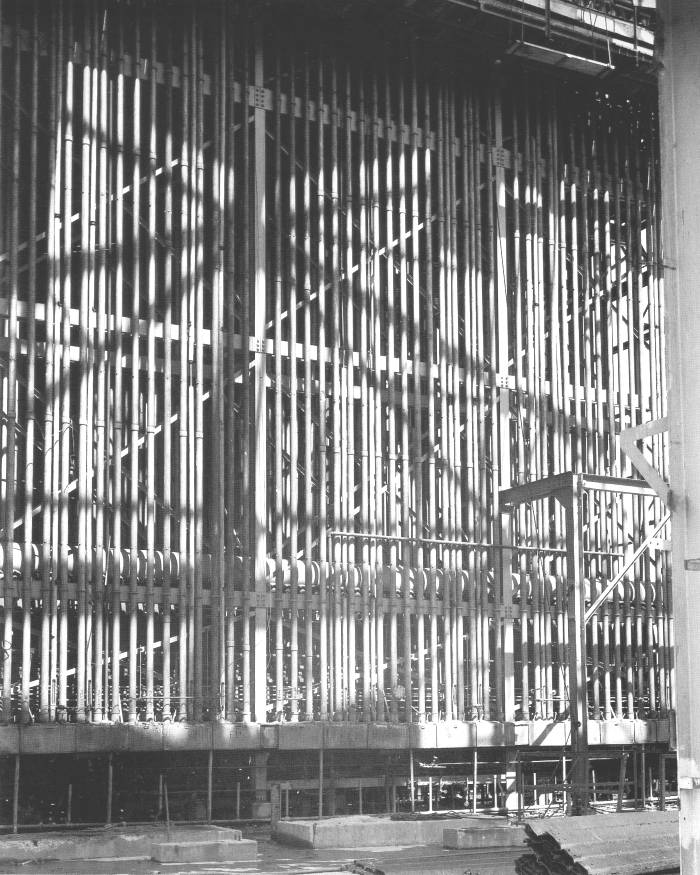

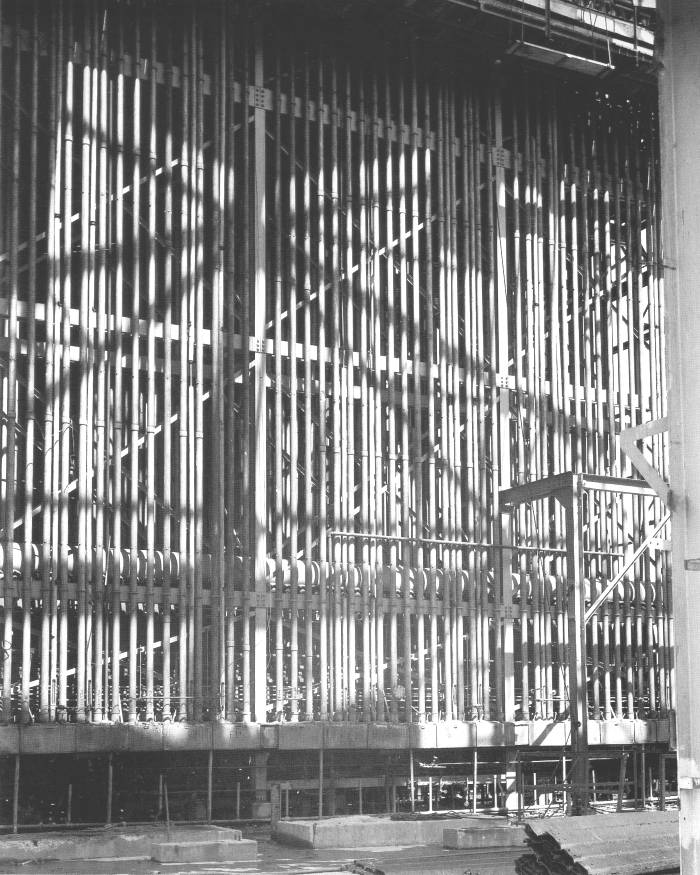

Ground was broken at the site on 9 July 1944. By 16 September, with about a third of the plant complete, the first rack had commenced operation. Testing in September and October revealed problems with leaking pipes that required further welding. Nonetheless, all racks were installed and ready for operations in January 1945. The construction contract was terminated on 15 February, and the remaining insulation and electrical work was assigned to other firms in the Oak Ridge area. They also completed the auxiliary buildings, including the new steam plant. The plant became fully operational in March 1945. Construction of the new boiler plant was approved on 16 February 1945. The first boiler was started on 5 July 1945, and operations commenced on 13 July. Work was completed on 15 August 1945.

The Thermal Diffusion Process Building (F01) was a black structure long, wide, and high. There was one control room and one transfer room for each pair of racks, except for the final one, which had its own control and transfer rooms for training purposes. Four pumps drew per minute of cooling water from the Clinch River. Steam pumps were specially designed by Pacific Pumps Inc. The plant was designed to use the entire output of the K-25 powerhouse, but as K-25 stages came online there was competition for this. It was decided to build a new boiler plant. Twelve surplus boilers originally intended for destroyer escort

Destroyer escort (DE) was the United States Navy mid-20th-century classification for a warship designed with the endurance necessary to escort mid-ocean convoys of merchant marine ships.

Development of the destroyer escort was promoted by th ...

s were acquired from the navy. The lower hot wall temperature due to the reduced steam pressure ( instead of the of the pilot plant) was compensated for by the ease of operation. Because they were oil-fired, a oil tank farm was added, with sufficient storage to operate the plant for 60 days. In addition to the Thermal Diffusion Process Building (F01) and the new steam plant (F06) buildings, structures in the S-50 area included the pumping station

Pumping stations, also called pumphouses, are public utility buildings containing pumps and equipment for pumping fluids from one place to another. They are critical in a variety of infrastructure systems, such as water supply, Land reclamation, ...

(F02), laboratories, a cafeteria, machine shop (F10), warehouses, a gas station, and a water treatment plant (F03).

Production

For security reasons, Groves wanted H. K. Ferguson to operate the new plant, but it was aclosed shop

A pre-entry closed shop (or simply closed shop) is a form of union security agreement under which the employer agrees to hire union members only, and employees must remain members of the union at all times to remain employed. This is different fr ...

, and security regulations at the Clinton Engineer Works did not allow trade union

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

s. To get around this, H. K. Ferguson created a wholly owned subsidiary

A subsidiary, subsidiary company, or daughter company is a company (law), company completely or partially owned or controlled by another company, called the parent company or holding company, which has legal and financial control over the subsidia ...

, the Fercleve Corporation (from Ferguson of Cleveland), and the Manhattan District contracted it to operate the plant for $11,000 a month. Operating personnel for the new plant were initially trained at the Philadelphia pilot plant. In August 1944, Groves, Conant and Fox asked ten enlisted men of the Special Engineer Detachment (SED) at Oak Ridge for volunteers, warning that the job would be dangerous. All ten volunteered. Along with four Fercleve employees, they were sent to Philadelphia to learn about the plant's operation.

On 2 September 1944, SED Private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* "In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorded ...

Arnold Kramish, and two civilians, Peter N. Bragg, Jr., an NRL chemical engineer, and Douglas P. Meigs, a Fercleve employee, were working in a transfer room when a cylinder of uranium hexafluoride exploded, rupturing nearby steam pipes. The steam reacted with the uranium hexafluoride to create hydrofluoric acid

Hydrofluoric acid is a solution of hydrogen fluoride (HF) in water. Solutions of HF are colorless, acidic and highly corrosive. A common concentration is 49% (48–52%) but there are also stronger solutions (e.g. 70%) and pure HF has a boiling p ...

, and the three men were badly burned. Private John D. Hoffman ran through the toxic cloud to rescue them, but Bragg and Meigs died from their injuries. Another eleven men, including Kramish and four other soldiers, were injured but recovered. Hoffman, who suffered burns, was awarded the Soldier's Medal, the United States Army's highest award for an act of valor in a non-combat situation, and the only one awarded to a member of the Manhattan District. Bragg was posthumously awarded the Navy Meritorious Civilian Service Award

The Navy Meritorious Civilian Service Award is awarded to civilian employees in the United States Department of the Navy for meritorious service or contributions resulting in high value or benefits for the Navy or the Marine Corps. It is conferre ...

on 21 June 1993.

Colonel Stafford L. Warren, the chief of the Manhattan District's Medical Section, removed the internal organs of the dead and sent them back to Oak Ridge for analysis. They were buried without them. An investigation found that the accident was caused by the use of steel cylinders with nickel linings instead of seamless nickel cylinders because the army had pre-empted nickel production. The Navy Hospital did not have procedures for the treatment of people exposed to uranium hexafluoride, so Warren's Medical Section developed them. Groves ordered a halt to training at the Philadelphia pilot plant, so Abelson and 15 of his staff moved to Oak Ridge to train personnel there.

There were no fatal accidents at the production plant, although it had a higher accident rate than other Manhattan Project production facilities due to the haste to get it into operation. When the crews attempted to start the first rack there was a loud noise and a cloud of vapor due to escaping steam. This would normally have resulted in a shutdown, but under the pressure to get the plant operational, the Fercleve plant manager had no choice but to press on. The plant produced just of 0.852% uranium-235 in October. Leaks limited production and forced shutdowns over the next few months, but in June 1945 it produced . In normal operation, of product was drawn from each circuit every 285 minutes. With four circuits per rack, each rack could produce per day. By March 1945, all 21 production racks were operating. Initially the output of S-50 was fed into Y-12, but starting in March 1945 all three enrichment processes were run in series. S-50 became the first stage, enriching from 0.71% to 0.89%. This material was fed into the gaseous diffusion process in the K-25 plant, which produced a product enriched to about 23%. This was, in turn, fed into Y-12, which boosted it to about 89%, sufficient for nuclear weapons. Total S-50 production was . It was estimated that the S-50 plant had sped up production of enriched uranium used in the Little Boy

Little Boy was a type of atomic bomb created by the Manhattan Project during World War II. The name is also often used to describe the specific bomb (L-11) used in the bombing of the Japanese city of Hiroshima by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ...

bomb employed in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima by a week. "If I had appreciated the possibilities of thermal diffusion," Groves later wrote, "we would have gone ahead with it much sooner, taken a bit more time on the design of the plant and made it much bigger and better. Its effect on our production of U-235 in June and July 1945 would have been appreciable."

Post-war years

Soon after the war ended in August 1945, Lieutenant Colonel Arthur V. Peterson, the Manhattan District officer with overall responsibility for the production offissile

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material that can undergo nuclear fission when struck by a neutron of low energy. A self-sustaining thermal Nuclear chain reaction#Fission chain reaction, chain reaction can only be achieved with fissil ...

material, recommended that the S-50 plant be placed on stand-by. The Manhattan District ordered the plant shut down on 4 September 1945. It was the only production-scale liquid thermal diffusion plant ever built, but its efficiency could not compete with that of a gaseous diffusion plant. The columns were drained and cleaned, and all employees were given two weeks' notice of impending termination of employment

Termination of employment or separation of employment is an employee's departure from a job and the end of an employee's duration with an employer. Termination may be voluntary on the employee's part ( resignation), or it may be at the hands of t ...

. All production had ceased by 9 September, and the last uranium hexafluoride feed was shipped to K-25 for processing. Layoff

A layoff or downsizing is the temporary suspension or permanent termination of employment of an employee or, more commonly, a group of employees (collective layoff) for business reasons, such as personnel management or downsizing an organization ...

s began on 18 September. By this time, voluntary resignations had reduced the Fercleve payroll from its wartime peak of 1,600 workers to around 900. Only 241 remained at the end of September. Fercleve's contract was terminated on 31 October, and responsibility for the S-50 plant buildings was transferred to the K-25 office. Fercleve laid off the last employees on 16 February 1946.

Starting May 1946, the S-50 plant buildings were utilised, not as a production facility, but by the United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

' Nuclear Energy for the Propulsion of Aircraft (NEPA) project. Fairchild Aircraft

Fairchild was an American aircraft and aerospace manufacturing company based at various times in Farmingdale, New York; Hagerstown, Maryland; and San Antonio, Texas.

History Early aircraft

The company was founded by Sherman Fairchild in 19 ...

conducted a series of experiments there involving beryllium

Beryllium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Be and atomic number 4. It is a steel-gray, hard, strong, lightweight and brittle alkaline earth metal. It is a divalent element that occurs naturally only in combination with ...

. Workers also fabricated blocks of enriched uranium and graphite

Graphite () is a Crystallinity, crystalline allotrope (form) of the element carbon. It consists of many stacked Layered materials, layers of graphene, typically in excess of hundreds of layers. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable ...

. NEPA operated until May 1951, when it was superseded by the joint Atomic Energy Commission-United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Air force, air service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is one of the six United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Tracing its ori ...

Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion project. The S-50 plant was disassembled in the late 1940s. Equipment was taken to the K-25 powerhouse area, where it was stored before being salvaged or buried.

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * {{Portal bar, History of Science, Nuclear technology, United States Buildings and structures in Roane County, Tennessee History of the Manhattan Project Isotope separation facilities of the Manhattan Project Oak Ridge, Tennessee