Réseau AGIR on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Réseau AGIR ( en, Network for ACTION) was a World War II espionage group founded by French wartime resister Michel Hollard that provided decisive

Daudemard, an AGIR railway engineer at

Daudemard, an AGIR railway engineer at

human intelligence

Human intelligence is the intellectual capability of humans, which is marked by complex cognitive feats and high levels of motivation and self-awareness. High intelligence is associated with better outcomes in life.

Through intelligence, humans ...

on V-1 flying bomb facilities

To carry out the planned V-1 "flying bomb" attacks on the United Kingdom, Germany built a number of military installations including launching sites and depots. Some of the installations were huge concrete fortifications.

The Allies became aware ...

in the North of France. Thanks to Hollard's reports and information from his agents of the Réseau AGIR, the V1 launch sites located across North-Eastern Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

to the Strait of Dover

The Strait of Dover or Dover Strait (french: Pas de Calais - ''Strait of Calais''), is the strait at the narrowest part of the English Channel, marking the boundary between the Channel and the North Sea, separating Great Britain from contine ...

, were systematically bombed during Operation Crossbow

''Crossbow'' was the code name in World War II for Anglo-American operations against the German long range reprisal weapons (V-weapons) programme.

The main V-weapons were the V-1 flying bomb and V-2 rocket – these were launched against Brita ...

.

Creation and organisation

The Réseau AGIR was created by Michel Hollard in 1941. The espionage network had no contact with otherFrench resistance

The French Resistance (french: La Résistance) was a collection of organisations that fought the German occupation of France during World War II, Nazi occupation of France and the Collaborationism, collaborationist Vichy France, Vichy régim ...

groups and reported directly to the British Secret Intelligence Service

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6 ( Military Intelligence, Section 6), is the foreign intelligence service of the United Kingdom, tasked mainly with the covert overseas collection and analysis of human intellige ...

(S.I.S.).

During the war, the network was codenamed "''Z 165''" after the codename given to Hollard himself by the ''Intelligence Service''. ''AGIR'' or ''Réseau AGIR'' only emerged after Hollard's return from the Liberation of France

The liberation of France in the Second World War was accomplished through diplomacy, politics and the combined military efforts of the Allied Powers, Free French forces in London and Africa, as well as the French Resistance.

Nazi Germany inv ...

.

Early 1941, Hollard became the concessionaire for the Seine department for the "Maison ''Gazogène Autobloc''", headquartered in Dijon, that, among other things, produced wood gas generators for automobiles and supplied its clients with charcoal. Hollard was allowed to travel in search of wood nationwide and purchase wood to turn it into charcoal to preserve the increasingly scarce fuel in occupied France.

In 1941, Hollard traveled to the French Free Zone and crossed the Swiss border for the first time to offer his services as a spy to the British embassy in Bern. He was greeted icily despite intelligence about France's wartime automotive manufacturing capabilities that he had brought with him to show his goodwill. When he came back a month later, the second meeting was much warmer since the British military attaché had made the necessary checks about him. Hollard was tasked to report the position and description of the German forces in the French Occupied Zone

Military occupation, also known as belligerent occupation or simply occupation, is the effective military control by a ruling power over a territory that is outside of that power's sovereign territory.Eyāl Benveniśtî. The international law ...

, especially the armored divisions. He committed to delivering intelligence every three weeks.

His job enabled him to travel around France using his job as a cover. Mostly traveling by train, he primarily established contacts with railway employees who, due to their work, had knowledge of the occupying forces' activities or knew how to obtain it.

From the very beginning, Hollard insisted that all actions should be organized through personal contacts only and that the exchange of researched material should only be forwarded or handed over to him personally. He distrusted the means of communication, such as the telephone or even radio, and saw in it a source of vulnerability for the network for the enemy. AGIR used signals with basic code like e.g. an open barn door indicated a Swiss border clear of soldiers. Entirely self-sufficient, the network did not rely on parachute drops or wireless transmitters. Intelligence was collected and sent to Switzerland every 3 weeks.

Hollard paid for the AGIR expenses, out of his pocket, until the British intelligence recognized the importance of the information collected by the network and offered to finance it. The network could rely on safe houses to cross the Swiss border and a safe place near Compiègne

Compiègne (; pcd, Compiène) is a commune in the Oise department in northern France. It is located on the river Oise. Its inhabitants are called ''Compiégnois''.

Administration

Compiègne is the seat of two cantons:

* Compiègne-1 (with 19 ...

s disguised as a peat-based fuel factory next to a bog

A bog or bogland is a wetland that accumulates peat as a deposit of dead plant materials often mosses, typically sphagnum moss. It is one of the four main types of wetlands. Other names for bogs include mire, mosses, quagmire, and muskeg; a ...

in the marshes of the river Oise.

Early 1942, Hollard had recruited a total of 6 agents, distributed throughout the Occupied Zone, to report the movement of German forces as requested by the British. All of them were personally financed by Hollard. The network could also rely on volunteers to gather information on German facilities like aerodromes and factories. Railway employees and station masters

The station master (or stationmaster) is the person in charge of a railway station, particularly in the United Kingdom and many other countries outside North America. In the United Kingdom, where the term originated, it is now largely historica ...

also played an important to report changes in enemy positions. When the ''Zone libre

The ''zone libre'' (, ''free zone'') was a partition of the French metropolitan territory during World War II, established at the Second Armistice at Compiègne on 22 June 1940. It lay to the south of the demarcation line and was administered ...

'' was placed under German military administration in November 1942, the network needed to grow to gather information in the whole of France. Hollard recruited hotel personnel and domestic worker

A domestic worker or domestic servant is a person who works within the scope of a residence. The term "domestic service" applies to the equivalent occupational category. In traditional English contexts, such a person was said to be "in service ...

s working in requisitioned hotels or private houses to cater to German troops.

On 30 juin 1942, Réseau AGIR member Olivier Giran was captured in Dijon, later transferred to the Fresnes prison and executed in April 1943 in Angers

Angers (, , ) is a city in western France, about southwest of Paris. It is the prefecture of the Maine-et-Loire department and was the capital of the province of Anjou until the French Revolution. The inhabitants of both the city and the pr ...

.

Hollard smuggled information from Occupied France

The Military Administration in France (german: Militärverwaltung in Frankreich; french: Occupation de la France par l'Allemagne) was an interim occupation authority established by Nazi Germany during World War II to administer the occupied zo ...

first to the British military attaché

A military attaché is a military expert who is attached to a diplomatic mission, often an embassy. This type of attaché post is normally filled by a high-ranking military officer, who retains a commission while serving with an embassy. Oppo ...

in Bern, Switzerland and later, to his handler of the Intelligence Service in Lausanne

Lausanne ( , , , ) ; it, Losanna; rm, Losanna. is the capital and largest city of the Swiss French speaking canton of Vaud. It is a hilly city situated on the shores of Lake Geneva, about halfway between the Jura Mountains and the Alps, and fac ...

. He made a total of ninety-eight crossings of the Swiss border from 1941 through February 1944 when he was betrayed and arrested on 5 February 1944. Michel Hollard and 4 other AGIR agents (including Henri Dujarier and Jules Mailly) were arrested during a cafe meeting on the Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis

The Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis is a street in the 10th arrondissement of Paris. It crosses the arrondissement from north to south, linking the Porte Saint-Denis to La Chapelle Métro station and passing the Gare du Nord.

History

The Rue du F ...

. Hollard was tortured and subjected to waterboarding

Waterboarding is a form of torture in which water is poured over a cloth covering the face and breathing passages of an immobilized captive, causing the person to experience the sensation of drowning. In the most common method of waterboard ...

five times by the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one or ...

and the Milice

The ''Milice française'' (French Militia), generally called ''la Milice'' (literally ''the militia'') (), was a political paramilitary organization created on 30 January 1943 by the Vichy regime (with German aid) to help fight against the F ...

, and imprisoned first at Fresnes prison

Fresnes Prison (''French Centre pénitentiaire de Fresnes'') is the second largest prison in France, located in the town of Fresnes, Val-de-Marne, south of Paris. It comprises a large men's prison (''maison d'arrêt'') of about 1200 cells, a small ...

and in June 1944 as a forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of e ...

er at the main Neuengamme concentration camp. Jules Mailly died in Mauthausen concentration camp

Mauthausen was a Nazi concentration camp on a hill above the market town of Mauthausen (roughly east of Linz), Upper Austria. It was the main camp of a group with nearly 100 further subcamps located throughout Austria and southern Germany ...

.

The network was composed of about two hundred agents and informants at its peak, among which French poet Robert Desnos

Robert Desnos (; 4 July 1900 – 8 June 1945) was a French poet who played a key role in the Surrealist movement of his day.

Biography

Robert Desnos was born in Paris on 4 July 1900, the son of a licensed dealer in game and poultry at the '' H ...

. Arrested by the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one or ...

on 22 February 1944, Desnos provided information collected during his job at the journal ''Aujourd'hui

''Aujourd'hui'' (, ''Today'') was a daily newspaper which styled itself as "independent" and which was created in August 1940 by Henri Jeanson, to replace '' le Canard enchaîné'' under agreement with the Germans.

The first issue appeared o ...

'' and made false identity papers.

In total, 20 agents and informants of Réseaux AGIR were arrested, 4 executed and 17 died in or as a result of deportation.

V-1 espionage

Daudemard, an AGIR railway engineer at

Daudemard, an AGIR railway engineer at Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine in northern France. It is the prefecture of the region of Normandy and the department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe, the population ...

reported in July 1943 unusual constructions in Upper Normandy

Upper Normandy (french: Haute-Normandie, ; nrf, Ĥâote-Normaundie) is a former administrative region of France. On 1 January 2016, Upper and Lower Normandy merged becoming one region called Normandy.

History

It was created in 1956 from two de ...

. Michel Hollard's report of September 1943 to the British Secret Intelligence Service

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6 ( Military Intelligence, Section 6), is the foreign intelligence service of the United Kingdom, tasked mainly with the covert overseas collection and analysis of human intellige ...

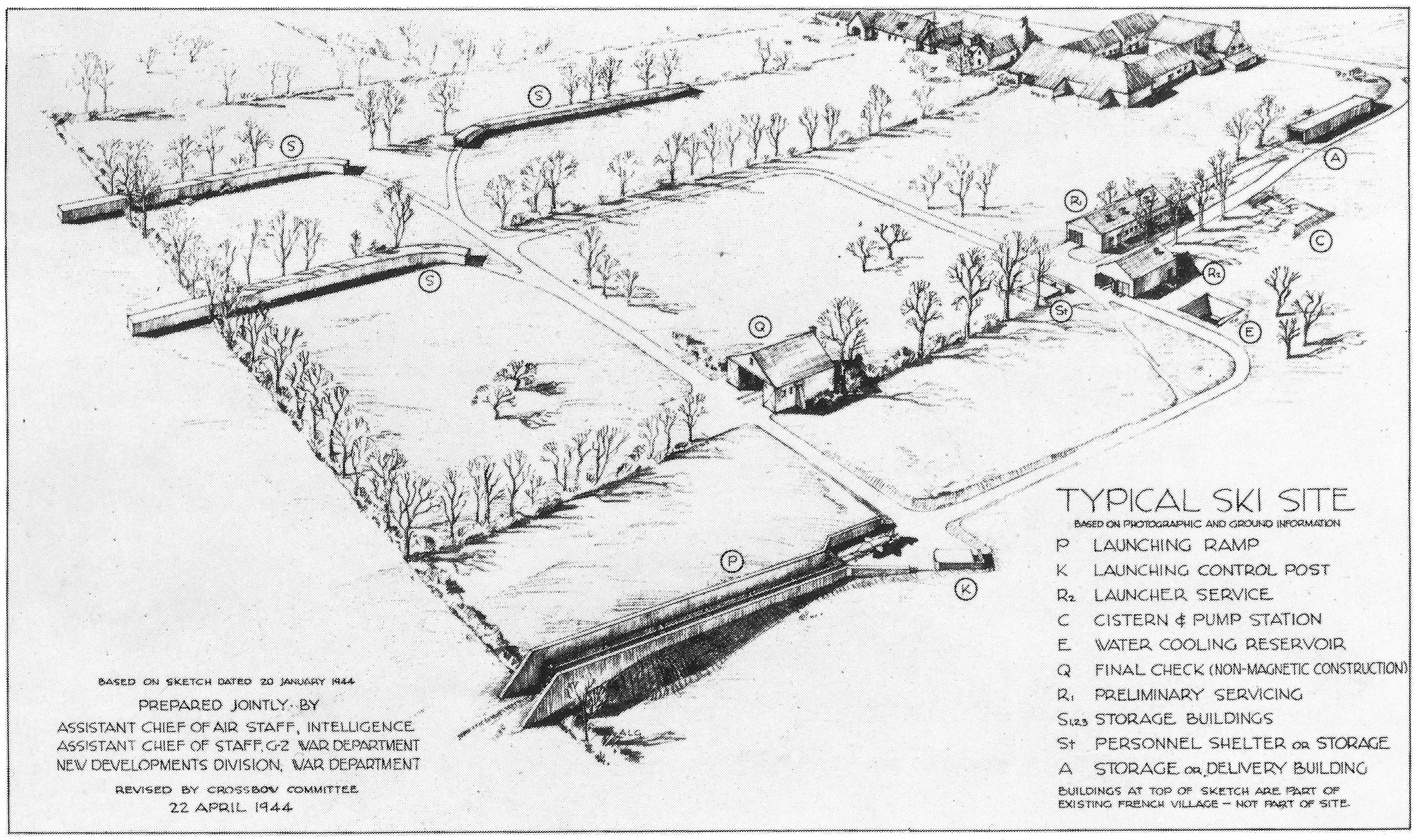

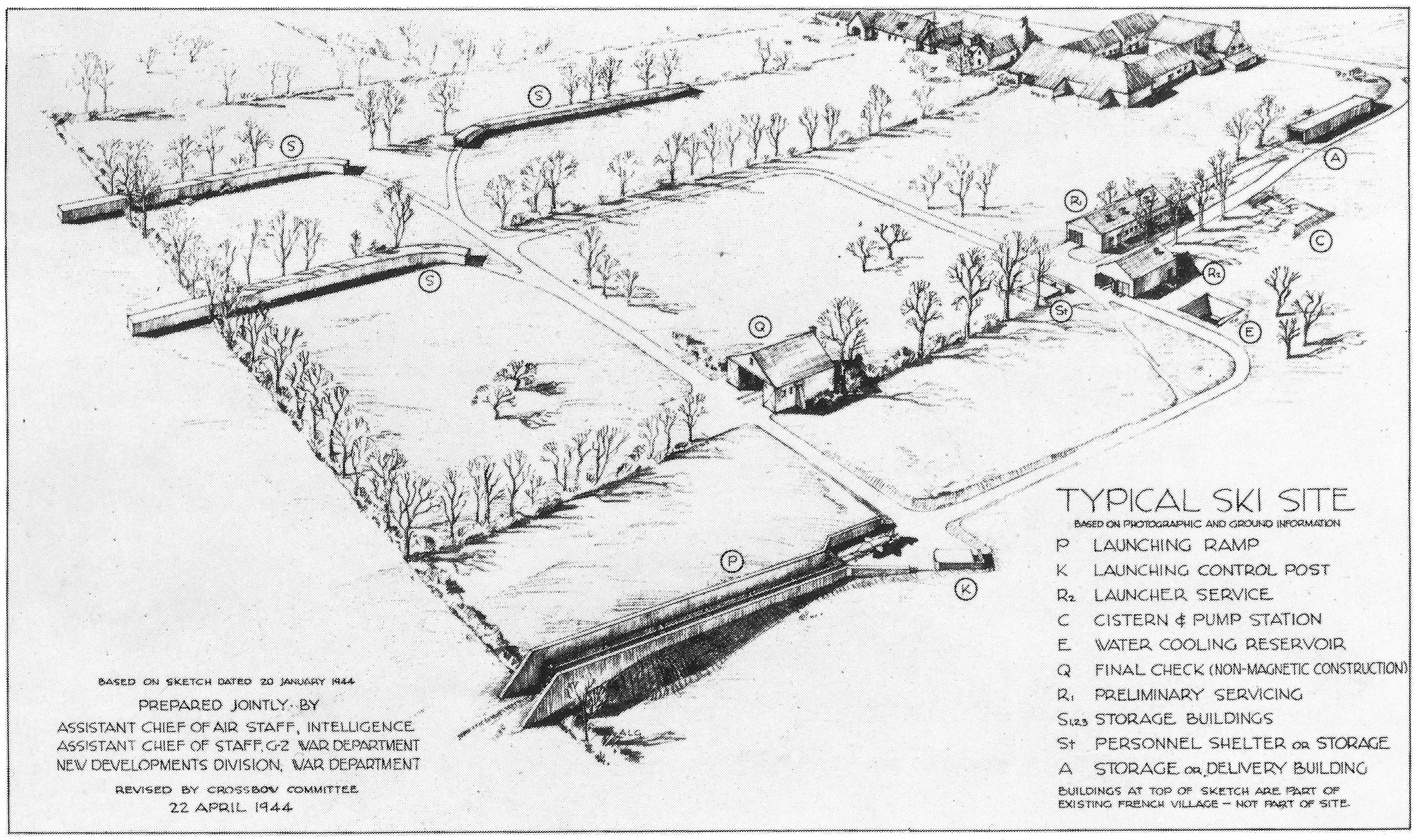

identified six V-1 flying bomb facilities

To carry out the planned V-1 "flying bomb" attacks on the United Kingdom, Germany built a number of military installations including launching sites and depots. Some of the installations were huge concrete fortifications.

The Allies became aware ...

: ", , Totes

Totes Isotoner Corporation, stylized totes»ISOTONER and often abbreviated to Totes, is an international umbrella, footwear, and cold weather accessory supplier, headquartered in Cincinnati, Ohio, USA. Totes is regularly billed in press reports as ...

, Ribeaucourt, Maison Ponthieu and Bois Carré".

AGIR prepared a more detailed report in October about Bois Carré, which is located 1.4 km east of Yvrench

Yvrench is a commune in the Somme department in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

Geography

Yvrench is situated 9 miles(15 km) northeast of Abbeville, on the D108 road, the route of the old Roman road, the Chaussée Brunehaut.

Populatio ...

, that claimed it had "a concrete platform with the center axis pointing directly to London". AGIR reconnoitered 104 V-1 facilities and helped pinpointing the Watten bunker, the first V-2 launching site.

AGIR also provided sketches of V-1 launching sites such as one by André Comps of Bois-Carré. It was labeled "''Yvrench

Yvrench is a commune in the Somme department in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

Geography

Yvrench is situated 9 miles(15 km) northeast of Abbeville, on the D108 road, the route of the old Roman road, the Chaussée Brunehaut.

Populatio ...

'' ''B2''" to deceive the Germans. "B" stands for "Bois" in French and "2" stands for the square root

In mathematics, a square root of a number is a number such that ; in other words, a number whose ''square'' (the result of multiplying the number by itself, or ⋅ ) is . For example, 4 and −4 are square roots of 16, because .

...

which in French is "Carré", hence Bois-Carré. Hollard had the site infiltrated by Comps, who worked as a drafter

A drafter (also draughtsman / draughtswoman in British and Commonwealth English, draftsman / draftswoman or drafting technician in American and Canadian English) is an engineering technician who makes detailed technical drawings or plans f ...

and copied "the blueprints"— a copy of the compass swinging building blueprint and the Bois-Carré sketch were published in 1978.

At the same time, André Bouguet, SNCF station director and AGIR informant, noticed transports that led north via Rouen. The destination of these transports was the Auffay train station. With the help of René Bourdon, the station manager there, and his assistant Pierre Carteron, Hollard was able to penetrate a shed of the local sugar factory in which the transported V-1 were stored, hidden under a tarpaulin and made precise dimensional sketches of the devices. The S.I.S. found an astonishing resemblance to Danish Lt-Colonel Hasager Christiansen's sketch that he had made of an aircraft that crashed on Bornholm

Bornholm () is a Danish island in the Baltic Sea, to the east of the rest of Denmark, south of Sweden, northeast of Germany and north of Poland.

Strategically located, Bornholm has been fought over for centuries. It has usually been ruled by ...

on 22 August 1943.

Thanks to Hollard's reports and information from his agents of the Réseau AGIR, the V1 launch sites located in the North of France, across North-Eastern Normandy to the Strait of Dover, were systematically bombed by the Royal Air Force between mid-December 1943 and March-end 1944, as a part of the Operation Crossbow

''Crossbow'' was the code name in World War II for Anglo-American operations against the German long range reprisal weapons (V-weapons) programme.

The main V-weapons were the V-1 flying bomb and V-2 rocket – these were launched against Brita ...

. Nine V1 sites were destroyed, 35 badly damaged and partially damaged another 25 out of the 104. As a result, the Germans changed their strategy and started building lighter and more camouflaged positions.

In his book Crusade in Europe General Eisenhower wrote that had the Germans been able to develop their weapons six months earlier and to target Britain's south coast, Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the Norm ...

would have been near impossible, or not at all possible. Winston Churchill, in '' Triumph and Tragedy'' also paid tribute to the sources of the British intelligence and reckoned that "''Our intelligence had played a vital part. The size and performance and the intended scale of attack were known to us in excellent time ..The launching sites and the storage caverns were found, enabling our fighters to delay the attack and mitigate its violence."''

Post-war

AGIR agents received various British and French military awards (including Hollard's DSO for V-1 espionage, secondCroix de Guerre

The ''Croix de Guerre'' (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awa ...

and Légion d'honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon B ...

), and Hollard's biographies provide AGIR history. Decorated with the Légion d'honneur, the French Croix de Guerre

The ''Croix de Guerre'' (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awa ...

and the British King's Medal for Courage

The King's Medal for Courage in the Cause of Freedom is a British medal for award to foreign nationals who aided the Allied effort during the Second World War.

Eligibility

Instituted on 23 August 1945, the medal was a reward to foreign nationals ...

, Joseph Brocard was the last surviving AGIR agent and died in 2009.

The flag of the AGIR network is on display at the Imperial War Museum

Imperial War Museums (IWM) is a British national museum organisation with branches at five locations in England, three of which are in London. Founded as the Imperial War Museum in 1917, the museum was intended to record the civil and military ...

, London.

References

Bibliography

;Primary sources * * * * ;Secondary sources * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Reseau Agir Spy rings French Resistance networks and movements Operation Crossbow World War II espionage