Russian Battleship Sevastopol (1911) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Sevastopol'' () was the first ship completed of the s of the

''Sevastopol'' was long at the waterline and long overall. She had a beam of and a

''Sevastopol'' was long at the waterline and long overall. She had a beam of and a

Specifications

{{DEFAULTSORT:Sevastopol (1911) Gangut-class battleships World War I battleships of Russia 1911 ships Ships built at the Baltic Shipyard Maritime incidents in 1915 Maritime incidents in 1916 Maritime incidents in 1929 Maritime incidents in November 1941

Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until being dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution and the declaration of ...

, built before World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. The ''Gangut''s were the first class

Class, Classes, or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used d ...

of Russian dreadnought

The dreadnought was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an effect when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her were referred to as "dreadnoughts", ...

s. She was named after the Siege of Sevastopol during the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

. She was completed during the winter of 1914–1915, but was not ready for combat until mid-1915. Her role was to defend the mouth of the Gulf of Finland

The Gulf of Finland (; ; ; ) is the easternmost arm of the Baltic Sea. It extends between Finland to the north and Estonia to the south, to Saint Petersburg—the second largest city of Russia—to the east, where the river Neva drains into it. ...

against the Germans, who never tried to enter, so she spent her time training and providing cover for minelaying operations. Her crew joined the general mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military or a crew) to oppose, change, or remove superiors or their orders. The term is commonly used for insubordination by members of the military against an officer or superior, ...

of the Baltic Fleet

The Baltic Fleet () is the Naval fleet, fleet of the Russian Navy in the Baltic Sea.

Established 18 May 1703, under Tsar Peter the Great as part of the Imperial Russian Navy, the Baltic Fleet is the oldest Russian fleet. In 1918, the fleet w ...

after the February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

and joined the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

s later that year. She was laid up in 1918 for lack of manpower, but her crew joined the Kronstadt rebellion

The Kronstadt rebellion () was a 1921 insurrection of Soviet sailors, Marines, naval infantry, and civilians against the Bolsheviks, Bolshevik government in the Russian port city of Kronstadt. Located on Kotlin Island in the Gulf of Finland, ...

of 1921. She was renamed ''Parizhskaya Kommuna'' after the rebellion was crushed to commemorate the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (, ) was a French revolutionary government that seized power in Paris on 18 March 1871 and controlled parts of the city until 28 May 1871. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard (France), Nation ...

and to erase the ship's betrayal of the Communist Party.

She was recommissioned in 1925, and refitted in 1928 in preparation for her transfer to the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

the following year. ''Parizhskaya Kommuna'' and the cruiser ''Profintern'' ran into a severe storm in the Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay ( ) is a gulf of the northeast Atlantic Ocean located south of the Celtic Sea. It lies along the western coast of France from Point Penmarc'h to the Spanish border, and along the northern coast of Spain, extending westward ...

that severely damaged ''Parizhskaya Kommuna''s false bow. They had to put into Brest for repairs, but reached Sevastopol

Sevastopol ( ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea and a major port on the Black Sea. Due to its strategic location and the navigability of the city's harbours, Sevastopol has been an important port and naval base th ...

in January 1930. ''Parizhskaya Kommuna'' was comprehensively reconstructed in two stages during the 1930s that replaced her boilers, upgraded her guns, augmented her anti-aircraft armament, modernized her fire-control systems and gave her anti-torpedo bulges. During World War II she provided gunfire support during the Siege of Sevastopol and related operations until she was withdrawn from combat in April 1942 when the risk from German aerial attack became too great. She was retained on active duty after the war until she became a training ship in 1954. She was broken up in 1956–1957.

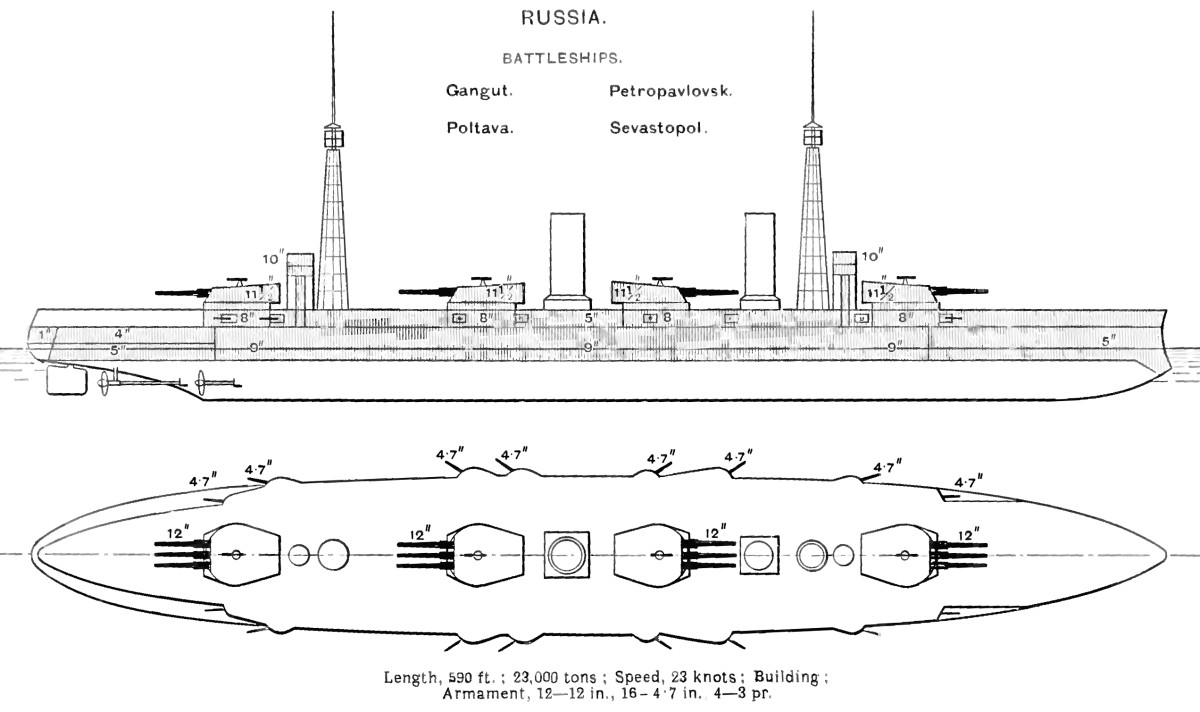

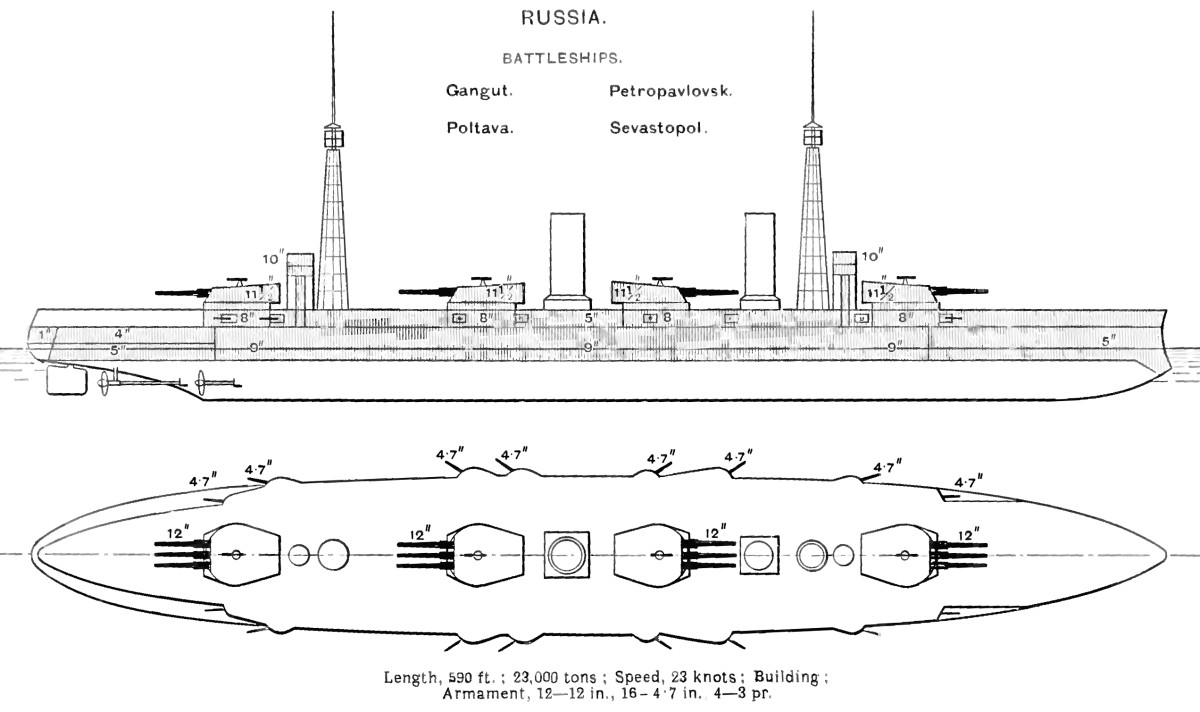

Design and description

''Sevastopol'' was long at the waterline and long overall. She had a beam of and a

''Sevastopol'' was long at the waterline and long overall. She had a beam of and a draft

Draft, the draft, or draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a v ...

of , more than designed. Her displacement was at load, over more than her designed displacement of .

''Sevastopol''s machinery was built by the Baltic Works. Ten Parsons-type steam turbine

A steam turbine or steam turbine engine is a machine or heat engine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work utilising a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Sir Charles Par ...

s drove the four propellers. The engine rooms were located between turrets three and four in three transverse compartments. The outer compartments each had a high-pressure ahead and reverse turbine for each wing propeller shaft. The central engine room had two each low-pressure ahead and astern turbines as well as two cruising turbines driving the two center shafts. The engines had a total designed output of , but they produced during her sister

A sister is a woman or a girl who shares parents or a parent with another individual; a female sibling. The male counterpart is a brother. Although the term typically refers to a familial relationship, it is sometimes used endearingly to ref ...

s full-speed trials on 21 November 1915 and gave a top speed of . Twenty-five Yarrow boiler

Yarrow boilers are an important class of high-pressure water-tube boilers. They were developed by

Yarrow Shipbuilders, Yarrow & Co. (London), Shipbuilders and Engineers and were widely used on ships, particularly warships.

The Yarrow boiler desi ...

s provided steam to the engines at a designed working pressure of . Each boiler was fitted with Thornycroft

Thornycroft was an English vehicle manufacturer which built coaches, buses, and trucks from 1896 until 1977.

History

In 1896, naval engineer John Isaac Thornycroft formed the Thornycroft Steam Carriage and Van Company which built its f ...

oil sprayers for mixed oil/coal burning. They were arranged in two groups. The forward group consisted of two boiler rooms in front of the second turret, the foremost of which had three boilers while the second one had six. The rear group was between the second and third turrets and comprised two compartments, each with eight boilers. At full load she carried of coal and of fuel oil

Fuel oil is any of various fractions obtained from the distillation of petroleum (crude oil). Such oils include distillates (the lighter fractions) and residues (the heavier fractions). Fuel oils include heavy fuel oil (bunker fuel), marine f ...

and that provided her a range of at a speed of .

The main armament of the ''Gangut''s consisted of a dozen 52-caliber

In guns, particularly firearms, but not #As a measurement of length, artillery, where a different definition may apply, caliber (or calibre; sometimes abbreviated as "cal") is the specified nominal internal diameter of the gun barrel Gauge ( ...

Obukhovskii Pattern 1907 guns mounted in four triple turrets distributed the length of the ship. The Russians did not believe that superfiring

Superfiring armament is a naval design technique in which two or more turrets are located one behind the other, with the rear turret located above ("super") the one in front so that it can fire over the first. This configuration meant that both ...

turrets offered any advantage, discounting the value of axial fire and believing that superfiring turrets could not fire while over the lower turret because of muzzle blast

A muzzle blast is an explosive shockwave created at the muzzle of a firearm during shooting. Before a projectile leaves the gun barrel, it obturates the bore and "plugs up" the pressurized gaseous products of the propellant combustion behind ...

problems. They also believed that distributing the turrets, and their associated magazine

A magazine is a periodical literature, periodical publication, print or digital, produced on a regular schedule, that contains any of a variety of subject-oriented textual and visual content (media), content forms. Magazines are generally fin ...

s, over the length of the ship improved the survivability of the ship. Sixteen 50-caliber Pattern 1905 guns were mounted in casemate

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armoured structure from which guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to antiquity, the term "casemate wall" ...

s as the secondary battery intended to defend the ship against torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

s. The ships were completed with only a single 30-caliber ''Lender'' anti-aircraft (AA) gun mounted on the quarterdeck. Other AA guns were probably added during the course of World War I, but details are lacking.McLaughlin, pp. 220–21 Budzbon says that four were added to the roofs of the end turrets during the war. Four submerged torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s were mounted with three torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

es for each tube.

Service

''Sevastopol'' was built by the Baltic Works inSaint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

. Her keel was laid down on 16 June 1909 and she was launched on 10 July 1911. She was commissioned on 30 November 1914 and reached Helsingfors late the next month where she was assigned to the First Battleship Brigade of the Baltic Fleet

The Baltic Fleet () is the Naval fleet, fleet of the Russian Navy in the Baltic Sea.

Established 18 May 1703, under Tsar Peter the Great as part of the Imperial Russian Navy, the Baltic Fleet is the oldest Russian fleet. In 1918, the fleet w ...

. ''Sevastopol'' and her sister

A sister is a woman or a girl who shares parents or a parent with another individual; a female sibling. The male counterpart is a brother. Although the term typically refers to a familial relationship, it is sometimes used endearingly to ref ...

provided distant cover for minelaying operations south of Liepāja

Liepāja () (formerly: Libau) is a Administrative divisions of Latvia, state city in western Latvia, located on the Baltic Sea. It is the largest city in the Courland region and the third-largest in the country after Riga and Daugavpils. It is an ...

on 27 August, the furthest that any Russian dreadnought ventured out of the Gulf of Finland

The Gulf of Finland (; ; ; ) is the easternmost arm of the Baltic Sea. It extends between Finland to the north and Estonia to the south, to Saint Petersburg—the second largest city of Russia—to the east, where the river Neva drains into it. ...

during World War I. She ran aground on 10 September and was under repair for two months. On 17 October a half-charge of powder was dropped and ignited when it impacted the floor of the forward magazine. Flooding the magazine prevented an explosion, but the fire killed two men and burned a number of others. She saw no action of any kind during 1916, but hit underwater rocks twice that year, suffering minor damage each time. Her crew joined the general mutiny of the Baltic Fleet on 16 March 1917, after the idle sailors received word of the February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

in Saint Petersburg. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Soviet Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria), by which Russia withdrew from World War I. The treaty, whi ...

required the Soviets to evacuate their base at Helsinki in March 1918 or have them interned by newly independent Finland

Finland, officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It borders Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bothnia to the west and the Gulf of Finland to the south, ...

, even though the Gulf of Finland

The Gulf of Finland (; ; ; ) is the easternmost arm of the Baltic Sea. It extends between Finland to the north and Estonia to the south, to Saint Petersburg—the second largest city of Russia—to the east, where the river Neva drains into it. ...

was still frozen over. ''Sevastopol'' and her sisters led the first group of ships out on 12 March and reached Kronstadt

Kronstadt (, ) is a Russian administrative divisions of Saint Petersburg, port city in Kronshtadtsky District of the federal cities of Russia, federal city of Saint Petersburg, located on Kotlin Island, west of Saint Petersburg, near the head ...

five days later in what became known as the 'Ice Voyage'.

The crew of the ''Sevastopol'' joined the Kronstadt rebellion

The Kronstadt rebellion () was a 1921 insurrection of Soviet sailors, Marines, naval infantry, and civilians against the Bolsheviks, Bolshevik government in the Russian port city of Kronstadt. Located on Kotlin Island in the Gulf of Finland, ...

of March 1921. She returned fire when the Bolsheviks began to bombard Kronstadt Island and was hit by three 12-inch shells that killed or wounded 102 sailors. After the rebellion was bloodily crushed, she was renamed ''Parizhskaya Kommuna'' after the Paris Commune

The Paris Commune (, ) was a French revolutionary government that seized power in Paris on 18 March 1871 and controlled parts of the city until 28 May 1871. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard (France), Nation ...

on 31 March 1921. She was refitted several times before she was recommissioned on 17 September 1925. She was refitted again in 1928 at the Baltic Shipyard, in preparation for her transfer to the Black Sea Fleet

The Black Sea Fleet () is the Naval fleet, fleet of the Russian Navy in the Black Sea, the Sea of Azov and the Mediterranean Sea. The Black Sea Fleet, along with other Russian ground and air forces on the Crimea, Crimean Peninsula, are subordin ...

. Her forward funnel was raised and the upper part was angled aft in an attempt to keep the exhaust gases out of the control and gunnery spaces, while three 3-inch 'Lender' AA guns were added to the roofs of the fore and aft turrets. She received some additional rangefinder

A rangefinder (also rangefinding telemeter, depending on the context) is a device used to Length measurement, measure distances to remote objects. Originally optical devices used in surveying, they soon found applications in other fields, suc ...

s and she was given a false bow to improve her sea-keeping ability. She sailed for the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

on 22 November 1929, in company of the cruiser ''Profintern'', encountering a bad storm in the Bay of Biscay. The open-topped bow lacked enough drainage and tended to trap a lot of water which badly damaged both the false bow and the supporting structure. ''Parizhskaya Kommuna'' was forced to put into Brest for repairs, which included the removal of the bulwark that retained so much water. Both ships arrived at Sevastopol

Sevastopol ( ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea and a major port on the Black Sea. Due to its strategic location and the navigability of the city's harbours, Sevastopol has been an important port and naval base th ...

on 18 January 1930 and ''Parizhskaya Kommuna'' became the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

of the Black Sea Fleet.

Reconstruction

She temporarily mounted an importedHeinkel

Heinkel Flugzeugwerke () was a German aircraft manufacturing company founded by and named after Ernst Heinkel. It is noted for producing bomber aircraft for the Luftwaffe in World War II and for important contributions to high-speed flight, wit ...

aircraft catapult

An aircraft catapult is a device used to help fixed-wing aircraft gain enough airspeed and lift for takeoff from a limited distance, typically from the deck of a ship. They are usually used on aircraft carrier flight decks as a form of assist ...

atop the third turret between 1930 and 1933. It was transferred to the cruiser when the battleship began the first stage of her reconstruction in November 1933. This was based on that done for her sister ''Oktyabrskaya Revolyutsiya'', but was even more extensive. Her rear superstructure was enlarged and a new structure was built just forward of it which required the repositioning of the mainmast forward. This did not leave enough room for a derrick

A derrick is a lifting device composed at minimum of one guyed mast, as in a gin pole, which may be articulated over a load by adjusting its Guy-wire, guys. Most derricks have at least two components, either a guyed mast or self-supporting tower ...

, as was fitted in ''Marat'', and two large booms were fitted to handle aircraft while the existing boat cranes remained in place. The mast had to be reinforced by two short legs to handle the weight of the booms and their loads. Her false bow was reworked into a real forecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck (ship), deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is t ...

like those fitted to her sisters. All twenty-five of her old boilers were replaced by a dozen oil-fired boilers originally intended for the s. The space saved was used to add another inboard longitudinal watertight bulkhead that greatly improved her underwater protection.

Her turrets were modified to use a fixed loading angle of 6° and fitted with more powerful elevating motors which increased their rate of fire to two rounds per minute. Their maximum elevation was increased to 40° which extended their range to and they were redesignated as MK-3-12 Mod. She landed her old 'Lender' AA guns and replaced them with six semi-automatic ''21-K'' AA guns, three atop the fore and aft turrets. Three 34-K each were mounted on platforms on the fore and aft superstructures as well as a total of twelve DShK

The DShK M1938 (Cyrillic: ДШК, for ) is a Soviet heavy machine gun. The weapon may be vehicle mounted or used on a tripod or wheeled carriage as a heavy infantry machine gun. The DShK's name is derived from its original designer, Vasily Degtya ...

M machine guns. Her fire-control system was completely revised with a pair of KDP-6 fire control director, equipped with two Zeiss rangefinder

A rangefinder (also rangefinding telemeter, depending on the context) is a device used to Length measurement, measure distances to remote objects. Originally optical devices used in surveying, they soon found applications in other fields, suc ...

s positioned atop both superstructures.McLaughlin, p. 345 Her original Pollen Argo Clock mechanical fire-control computer was replaced with a copy of a Vickers Ltd fire-control computer, designated AKUR by the Soviets, as well as a copy of a Sperry stable vertical gyroscope

A gyroscope (from Ancient Greek γῦρος ''gŷros'', "round" and σκοπέω ''skopéō'', "to look") is a device used for measuring or maintaining Orientation (geometry), orientation and angular velocity. It is a spinning wheel or disc in ...

. She also received the first stabilized anti-aircraft directors in the Soviet fleet, SVP-1s that were fitted on each side of the forward superstructure. They were manually stabilized and less than satisfactory as the men manning them had difficulties keeping their sights on the horizon while the ship's motions were violent.

''Parizhskaya Kommuna'' finished the first stage of her reconstruction in January 1938 with unresolved stability issues derived from all of the additional topweight. The options to cure this were discussed at length until Marshal Voroshilov, the People's Commissar for Defense approved the addition of anti-torpedo bulges in 1939 which would increase the ship's underwater protection and rectify her stability problem. The second part of the reconstruction was carried out between December 1939 and July 1940. A pair of bulges were fitted that extended from the forward magazine to the rear magazine that increased the ship's beam by . They had an unusual form that consisted of an outer void compartment intended to weaken the explosive force of the torpedo backed by a relatively narrow section immediately adjacent to the original hull that extended from above the waterline to the bottom of the bilge

The bilge of a ship or boat is the part of the hull that would rest on the ground if the vessel were unsupported by water. The "turn of the bilge" is the transition from the bottom of a hull to the sides of a hull.

Internally, the bilges (us ...

. This was divided into two compartments; the lower of which was kept full of either fuel oil or water to absorb splinters and fragments from the explosion while the upper compartment was filled with small watertight tubes intended to preserve the ship's waterplane area and minimize flooding from gunfire hits around the waterline. The underwater torpedo tubes were incompatible with the bulges and were removed at this time. The bulges increased her standard displacement to , increased her metacentric height

The metacentric height (GM) is a measurement of the initial static stability of a floating body. It is calculated as the distance between the centre of gravity of a ship and its '' metacentre''. A larger metacentric height implies greater initial ...

to and reduced her speed to . The Soviets took advantage of her extra stability to reinforce her deck armor by completely replacing her middle deck armor with cemented armor plates originally intended for s. These were not ideal as they were harder than desirable for deck plates, but they did have the prime virtue of being free. At some point, the exact date is unknown, her 45 mm guns were removed and sixteen ''70-K'' automatic AA guns were added, three each on the fore and aft turret tops and twelve in the superstructures.

World War II

Four of ''Parizhskaya Kommunas 120 mm guns were landed shortly before 22 June 1941.McLaughlin, p. 407 When the Germans invaded she was in Sevastopol,Rohwer, pp. 111, 119 and she was initially kept in reserve during the Soviet attack on the Romanian port of Constanța. She was evacuated toNovorossiysk

Novorossiysk (, ; ) is a city in Krasnodar Krai, Russia. It is one of the largest ports on the Black Sea. It is one of the few cities designated by the Soviet Union as a Hero City. The population was

History

In antiquity, the shores of the ...

on 30 October after the Germans breached Soviet defensive lines near the Perekop Isthmus. During 28–29 November she bombarded German and Romanian troops south of Sevastopol with 146 12-inch and 299 120 mm shells. On 29 November, three crew were washed overboard in a storm at Sevastopol and died. They were the only crew lost during the war. ''Parizhskaya Kommuna'' ran aground but was quickly refloated. She steamed into Sevastopol's South Bay on 29 December and fired 179 and 265 120 mm shells at German troops before embarking 1,025 wounded and departing in company with the cruiser on the 31st.McLaughlin, p. 402 She bombarded German positions south of Feodosiya

Feodosia (, ''Feodosiia, Teodosiia''; , ''Feodosiya''), also called in English Theodosia (from ), is a city on the Crimean coast of the Black Sea. Feodosia serves as the administrative center of Feodosia Municipality, one of the regions into w ...

on the evening of 4–5 January 1942 and on 12 January. ''Parizhskaya Kommuna'' provided gunfire support during Soviet landings behind German lines along the southern coast of the Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

three days later. She bombarded German positions west and north of Feodosiya on the nights of 26–28 February in support of an offensive by the 44th Army. She fired her last shots of the war at targets near Feodosiya during the nights of 20–22 March 1942 before returning to Poti

Poti ( ka, ფოთი ; Mingrelian language, Mingrelian: ფუთი; Laz language, Laz: ჶაში/Faşi or ფაში/Paşi) is a port city in Georgia (country), Georgia, located on the eastern Black Sea coast in the mkhare, region of ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

, to have her worn-out 12-inch guns relined. By the time this was finished the Soviets were unwilling to expose such a prominent ship to German air attacks, which had already sunk a number of cruisers and destroyers. She returned to her original name on 31 May 1943, but remained in Poti until late 1944 when she led the surviving major units of the Black Sea Fleet back to Sevastopol on 5 November. Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (),3,000 Hurricanes and >4,000 other aircraft)

* 28 naval vessels:

** 1 Battleship. (HMS Royal Sovereign (05), HMS Royal Sovereign)

* ...

British Type 290 and 291 air-warning radars were fitted during the war. She was awarded the Order of the Red Banner

The Order of the Red Banner () was the first Soviet military decoration. The Order was established on 16 September 1918, during the Russian Civil War by decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee. It was the highest award of S ...

on 8 July 1945.

She was reclassified as a 'school battleship' on 24 July 1954 and stricken on 17 February 1956. She was scrap

Scrap consists of recyclable materials, usually metals, left over from product manufacturing and consumption, such as parts of vehicles, building supplies, and surplus materials. Unlike waste, scrap can have monetary value, especially recover ...

ped at Sevastopol in 1956–1957.McLaughlin, p. 227

Notes

Footnotes

Bibliography

* * * * *External links

Specifications

{{DEFAULTSORT:Sevastopol (1911) Gangut-class battleships World War I battleships of Russia 1911 ships Ships built at the Baltic Shipyard Maritime incidents in 1915 Maritime incidents in 1916 Maritime incidents in 1929 Maritime incidents in November 1941