The , ) (RM) or Royal Italian Navy was the

navy

A navy, naval force, military maritime fleet, war navy, or maritime force is the military branch, branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral z ...

of the

Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

() from 1861 to 1946. In 1946, with the

birth of the Italian Republic (''Repubblica Italiana''), the changed its name to ''

Marina Militare

The Italian Navy (; abbreviated as MM) is one of the four branches of Italian Armed Forces and was formed in 1946 from what remained of the '' Regia Marina'' (Royal Navy) after World War II. , the Italian Navy had a strength of 30,923 active pe ...

'' ("Military Navy").

Origins

The was established on 17 March 1861 following the proclamation of the formation of the

Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

. Just as the Kingdom was a unification of various states in the

Italian peninsula, so the was formed from the navies of those states, though the main constituents were the

navies

A navy, naval force, military maritime fleet, war navy, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operation ...

of the former kingdoms of

Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

and

Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

. The new Navy inherited a substantial number of ships, both sail- and steam-powered, and the long naval traditions of its constituents, especially those of Sardinia and Naples, but also suffered from some major handicaps.

Firstly, it suffered from a lack of uniformity and cohesion; the was a heterogeneous mix of equipment, standards and practice, and even saw hostility between the officers from the various former navies. These problems were compounded by the continuation of separate officer schools at

Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

and

Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

, and were not fully addressed until the opening of a unified

Naval Academy

A naval academy provides education for prospective naval officers.

List of naval academies

See also

* Military academy

{{Authority control

Naval academies,

Naval lists ...

at

Livorno

Livorno () is a port city on the Ligurian Sea on the western coast of the Tuscany region of Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Livorno, having a population of 152,916 residents as of 2025. It is traditionally known in English as Leghorn ...

in 1881.

Secondly,

unification occurred during a period of rapid advances in naval technology and tactics, as typified by the launch of by

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

in 1858, and later by the appearance of, and battle between, and in 1862. These innovations quickly made older warships obsolete. Italy did not possess the shipyards or infrastructure to build the modern ships required, but the then Minister for the Navy, Admiral

Carlo di Persano, launched a substantial programme to purchase warships from foreign yards.

Seven Weeks War

The new navy's baptism of fire came on 20 July 1866 at the

Battle of Lissa during the

Third Italian War of Independence (parallel to the

Seven Weeks War). The battle was fought against the

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

and occurred near the island of

Vis in the

Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

. That was one of the few fleet actions of the 19th century and as a major sea battle that involved

ramming

In warfare, ramming is a technique used in air, sea, and land combat. The term originated from battering ram, a siege engine used to bring down fortifications by hitting it with the force of the ram's momentum, and ultimately from male sheep. Thus ...

, it is often considered to have had a profound effect on subsequent warship design and tactics.

The Italian fleet, commanded by Admiral Persano, mustered 12

ironclad

An ironclad was a steam engine, steam-propelled warship protected by iron armour, steel or iron armor constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or ince ...

and 17 wooden-hulled ships, though only one, , was of the most modern

turret ship design. Despite a marked disadvantage in numbers and equipment, superior handling by the Austrians under Admiral

Wilhelm von Tegetthoff

Wilhelm von Tegetthoff (23 December 18277 April 1871) was an Austrian Empire, Austrian admiral. He commanded the fleet of the North Sea during the Second Schleswig War of 1864, and the Austro-Prussian War of 1866. He is often considered by some A ...

resulted in a severe defeat for Italy, which lost two armoured ships and 640 men.

Decline and resurgence

After the war, the passed through some difficult years as the naval budget was substantially reduced, thus impairing the fleet's efficiency and the pace of new construction; only in the 1870s, under

Simone Pacoret de Saint Bon's ministry, did the situation begin to improve. In 1881, the battleship was commissioned, followed in 1882 by the battleship ; at the time these were the most powerful warships in the world, and signalled the Italian fleet's renewed power. In 1896 the corvette ''Magenta'' completed a circumnavigation of the world. The following year the conducted experiments with

Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi, 1st Marquess of Marconi ( ; ; 25 April 1874 – 20 July 1937) was an Italian electrical engineer, inventor, and politician known for his creation of a practical radio wave-based Wireless telegraphy, wireless tel ...

in the use of radio communications. 1909 saw the first use of aircraft with the fleet. An Italian naval officer,

Vittorio Cuniberti, was the first in 1903 to envision in a published article the all-big gun battleship design, which would be later come to be known as

dreadnought

The dreadnought was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an effect when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her were referred to as "dreadnoughts", ...

.

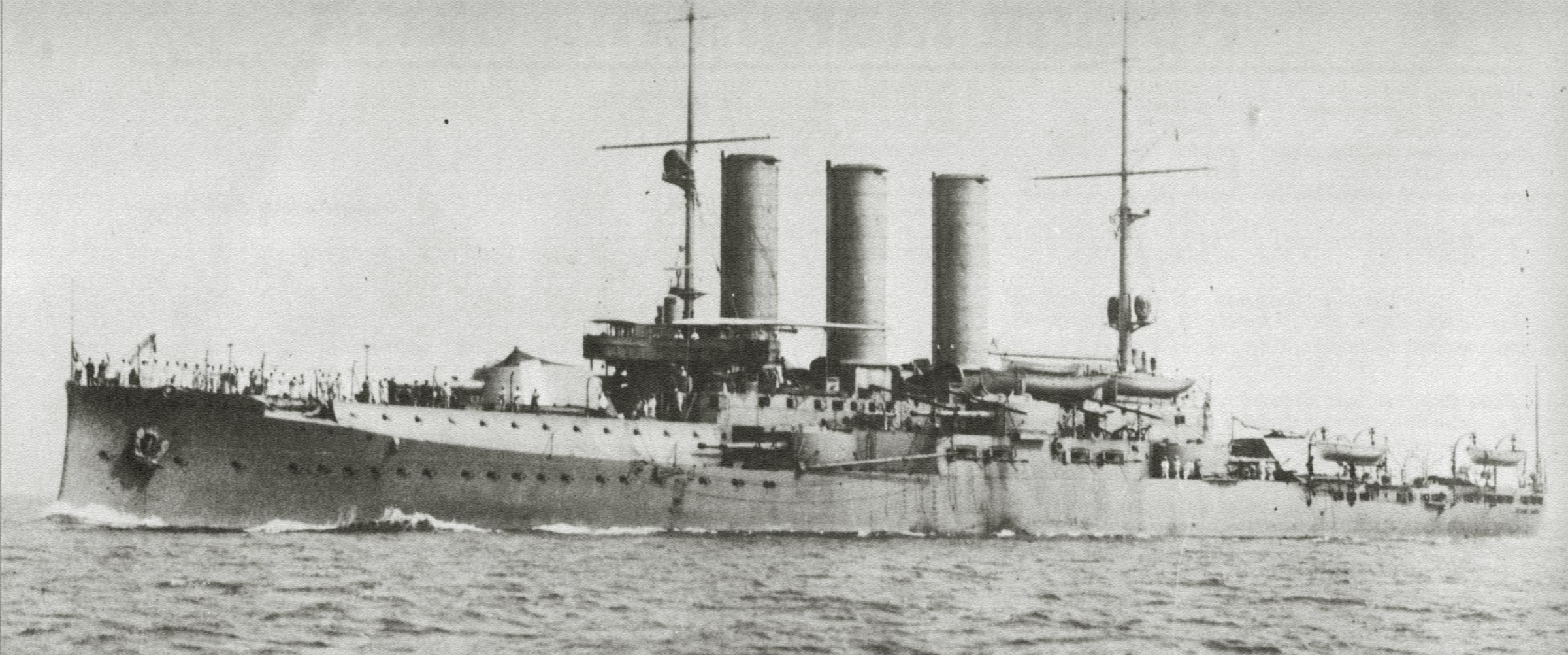

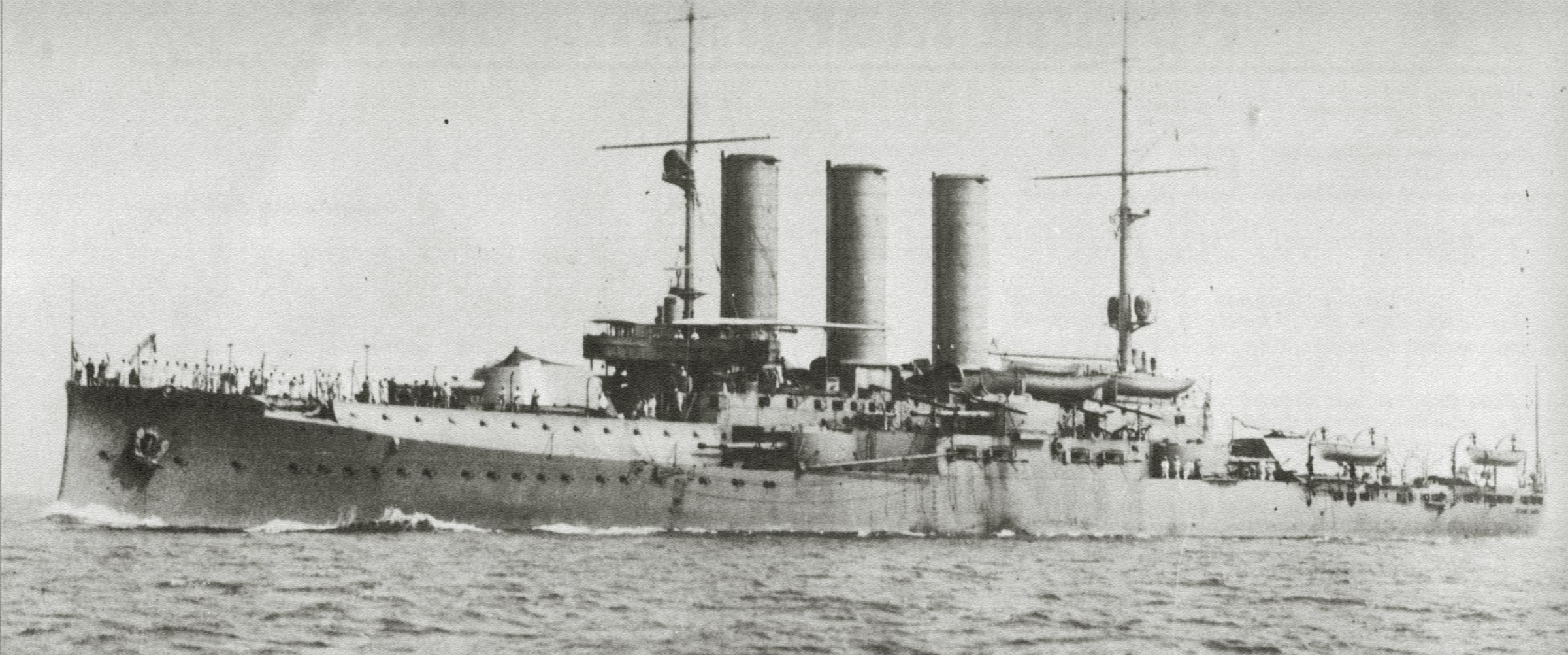

Italo-Turkish War

In 1911 and 1912, the was involved in the

Italo-Turkish War

The Italo-Turkish (, "Tripolitanian War", , "War of Libya"), also known as the Turco-Italian War, was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 29 September 1911 to 18 October 1912. As a result of this conflict, Italy captur ...

against forces of the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. As the majority of the

Ottoman Navy

The Ottoman Navy () or the Imperial Navy (), also known as the Ottoman Fleet, was the naval warfare arm of the Ottoman Empire. It was established after the Ottomans first reached the sea in 1323 by capturing Praenetos (later called Karamürsel ...

stayed behind the relative safety of the

Dardanelles

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey th ...

, the Italians dominated the Mediterranean during the conflict winning victories against Ottoman light units at the battles of

Preveza

Preveza (, ) is a city in the region of Epirus (region), Epirus, northwestern Greece, located on the northern peninsula of the mouth of the Ambracian Gulf. It is the capital of the Preveza (regional unit), regional unit of Preveza, which is the s ...

and

Beirut

Beirut ( ; ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, just under half of Lebanon's population, which makes it the List of largest cities in the Levant region by populatio ...

. In the Red Sea the Italian forces were vastly superior to those of the Ottomans who possessed only a squadron of gunboats there. These were destroyed while attempting to withdraw into the Mediterranean at the

Battle of Kunfuda Bay.

World War I

Before 1914, the Kingdom of Italy built six

dreadnought

The dreadnought was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an effect when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her were referred to as "dreadnoughts", ...

battleships: ( as a prototype; , and of the ; and and of the ), but they did not participate in any major naval actions in

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

.

During the war, the spent its minor efforts in the

Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

, opposing the

Austro-Hungarian Navy

The Austro-Hungarian Navy or Imperial and Royal War Navy (, in short ''k.u.k. Kriegsmarine'', ) was the navy, naval force of Austria-Hungary. Ships of the Austro-Hungarian Navy were designated ''SMS'', for ''Seiner Majestät Schiff'' (His Majes ...

. The resulting

Adriatic Campaign of World War I

The Adriatic Campaign of World War I was a naval campaign fought between the Central Powers and the Mediterranean squadrons of the Allies, specifically the United Kingdom, France, the Kingdom of Italy, Australia, and the United States.

Characte ...

consisted mainly of Austro-Hungarian coastal bombardments of Italy's Adriatic coast, and wider-ranging German/Austro-Hungarian submarine warfare into the Mediterranean. Allied forces mainly limited themselves to blockading the Austro-Hungarian navy inside the Adriatic, which was successful with regards to surface units, but failed for the submarines, which found safe harbours and easy passage into and out of the area for the whole of the war. Considered a relatively minor part of the

naval warfare of World War I

Naval warfare in World War I was mainly characterised by blockade. The Allied powers, with their larger fleets and surrounding position, largely succeeded in their blockade of Germany and the other Central Powers, whilst the efforts of the Cent ...

, it nonetheless tied down significant forces.

In December 1915, and January 1916, when the Serbian army was driven by the German forces under General von Mackensen toward the Albanian coast, 138,000 Serbian infantry and 11,000 refugees were ferried across the Adriatic and landed in Italy in 87 trips by the and other shps of the Italian Navy under the command of Admiral Conz. These ships also carried 13,000 cavalrymen and 10,000 horses of the Serbian army to Corfu in 13 crossings from the Albanian port of Vallons.

For most of the war the Italian navy avoided wherever possible the Austro-Hungarian navy. The Italian fleet lost the destroyer ''Turbine'' in 1915 to an Austro-Hungarian fleet sortie; the armoured cruiser ''Amalfi'' was sunk by Austrian submarine U-26 on 7 July 1915; the armoured cruiser ''Giuseppe Garibaldi'', sunk by Austrian submarine U-4 on 18 July 1915, the pre-dreadnought battleship at

Brindisi

Brindisi ( ; ) is a city in the region of Apulia in southern Italy, the capital of the province of Brindisi, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. Historically, the city has played an essential role in trade and culture due to its strategic position ...

(27 September 1915) and the dreadnought at

Taranto

Taranto (; ; previously called Tarent in English) is a coastal city in Apulia, Southern Italy. It is the capital of the province of Taranto, serving as an important commercial port as well as the main Italian naval base.

Founded by Spartans ...

(2 August 1916) due to a magazine explosion (although there were rumours of Austrian sabotage). The Austrians also sank the Italian armed merchant cruiser SS Principe Umberto on 8 June 1916. While transporting troops in the Adriatic, the ship was sunk by Austro-Hungarian U-boat U-5 with the loss of 1,926 men. It was the worst naval disaster of World War I in terms of human lives lost.

In the last part of the war, the Regia Marina developed the

MAS boats, that, by chance, managed to sink the Austro-Hungarian battleship in the

Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

on 10 June 1918; and an early type of

human torpedo

Human torpedoes or manned torpedoes are a type of diver propulsion vehicle on which the diver rides, generally in a seated position behind a fairing. They were used as secret naval weapons in World War II. The basic concept is still in use.

...

(codenamed ''

Mignatta'', or "leech") carrying two men, which entered the harbour of

Pola and planted two magnetic mines during the early hours of the morning which exploded sinking the

Austro-Hungarian

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military and diplomatic alliance, it consist ...

flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

, with considerable loss of life, on 1 November 1918, shortly after the entire navy had been turned over to the newly founded neutral State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. The battleship (sister of the former two) was handed over to Italy as a war prize in 1919.

Interwar years

During the interwar years the Italian government set about modernizing the in a way that could enable it to reach dominance over the Mediterranean Sea. Italian naval planners also wanted a force capable of taking on the

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

, especially after the

Fascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

takeover. The British response to the

Corfu incident left

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

and his military advisors convinced that Italy was "imprisoned in the Mediterranean" through British bases in

Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

, the

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

,

Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

, and

Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

. Italian naval construction was limited by the

Washington Naval Conference

The Washington Naval Conference (or the Washington Conference on the Limitation of Armament) was a disarmament conference called by the United States and held in Washington, D.C., from November 12, 1921, to February 6, 1922.

It was conducted out ...

. The 1922 treaty required a parity in naval forces between the Italian and French navies, with equality in total displacement in battleships and carriers. The treaty influenced the development of the Italian fleet over the years between the two world wars. Between the late twenties and early thirties a construction program began, focusing first on cruisers up to 10,000 tons, followed by the building of destroyers and submarines, and lastly the construction of the new

s; plans were also put in place to modernize the and

s. Much of these new naval units were responses to French naval constructions, as the

Marine nationale

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in the world recognised as being a blu ...

was seen until the mid-1930s as the most likely enemy in a hypothetical conflict.

The chose to build fast ships armed with longer ranged guns to give the Italian vessels the ability to minimize close contact with vessels of the Royal Navy, whose crews were more experienced. In theory this would allow them to engage or break off at their own choosing, and would allow them to hit the enemy when he could not yet hit back. New guns were developed with longer ranges than their British counterparts of similar caliber. Speed was emphasized in their new construction. Italian cruisers built in the 1920s, such as were built with a newly designed and relatively thin armour. This would have a decisive role in a number of naval battles, including the

Battle of Cape Spada. Later classes, such as the and classes, were built to a more balanced design with thicker armor.

The modernization work on the four Great War era battleships turned into a significant reconstruction project, with only 40% of the original structures being left. The ship's guns were upgraded in main armament, going from 13 guns of 305 mm diameter, to 10 guns of 320 mm diameter. The middle turret and the vessel's central tower were eliminated. To increase speed the coal-fired boilers were replaced with modern oil-fired boilers and ten meters were added to the ship's length to improve the

coefficient of fineness. Though the ships were improved, they still were not an equal match for the s and the s, both of which carried larger guns and heavier armour.

Though scientific research on tracking devices such as radar and sonar was being conducted in Italian universities and military laboratories by men such as

Ugo Tiberio and

Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi, 1st Marquess of Marconi ( ; ; 25 April 1874 – 20 July 1937) was an Italian electrical engineer, inventor, and politician known for his creation of a practical radio wave-based Wireless telegraphy, wireless tel ...

, the conservative Italian leadership had little interest in these new technologies, and did not use them to improve the effectiveness of the Italian vessels. This was mainly due to the influence of Admiral

Domenico Cavagnari, whom Mussolini appointed as Chief of Staff of the Navy in 1933, and whom he later promoted to Secretary of the Navy. Likewise technological advancement in radio range finders and gunnery control devices for night combat were not incorporated. Regarding such devices, Cavagnari emphasized "not wanting traps in your way". Writing to Admiral Iachino, he wrote "''procedere con estrema cautela nell'accettare brillanti novità tecniche che non siano ancora collaudate da una esperienza pratica sufficientemente lunga''", which can be translated to "proceed with extreme caution regarding brilliant technical innovations that have not yet been tested or with which there is no practical experience". Thus, the Italian navy entered the Second World War with a marked technical inferiority to the

British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

.

Albert Kesselring

Albert Kesselring (30 November 1885 – 16 July 1960) was a German military officer and convicted war crime, war criminal who served in the ''Luftwaffe'' during World War II. In a career which spanned both world wars, Kesselring reached the ra ...

, overall commander of Axis forces in the Mediterranean, observed that the Italian navy was "a good weather" force, unable to operate effectively at night or in heavy seas.

Two training ships were built during this period, in addition to the effort to modernize and re-equip the combat vessels of the navy. These were square rigged school ships the ordered in 1925. The sailing ships followed a design by Lieutenant Colonel

Francesco Rotundi of the Italian Navy Engineering Corps, reminiscent of

ships of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which involved the two column ...

from the

Napoleonic era

The Napoleonic era is a period in the history of France and history of Europe, Europe. It is generally classified as including the fourth and final stage of the French Revolution, the first being the National Assembly (French Revoluti ...

. The first of these two ships, , was put into service in 1928 and was used by the Italian Navy for training until 1943. After

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, this ship was handed over to the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

as part of

war reparation

War reparations are compensation payments made after a war by one side to the other. They are intended to cover damage or injury inflicted during a war. War reparations can take the form of hard currency, precious metals, natural resources, in ...

s and was shortly afterwards decommissioned. The second ship of the design was . The ship was built in 1930 at the (formerly Royal) Naval Shipyard of

Castellammare di Stabia (

Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

). She was launched on 22 February 1931, and was put into service in July of that year. She is still being used to this day.

In 1928, the unified command of the "''Armata Navale''" was abolished, and the fleet was divided in two

squadrons (''Squadre navali''), one based at La Spezia and the other based at Taranto.

Italo-Ethiopian War

The played a limited role in the

invasion of Ethiopia. While the

Ethiopian Empire

The Ethiopian Empire, historically known as Abyssinia or simply Ethiopia, was a sovereign state that encompassed the present-day territories of Ethiopia and Eritrea. It existed from the establishment of the Solomonic dynasty by Yekuno Amlak a ...

was landlocked, the navy was instrumental in delivering and supplying the invasion forces through

Somali and

Eritrea

Eritrea, officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa, with its capital and largest city being Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia in the Eritrea–Ethiopia border, south, Sudan in the west, and Dj ...

n ports.

Spanish Civil War

At the time of the Italian intervention in the

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

, the sent naval units in support of the Italian Corps of Volunteer Troops (''

Corpo Truppe Volontarie''). Approximately 58 Italian submarines took part in operations against the

Spanish Republican Navy. These submarines were organized in a Submarine Legion and complemented German

Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official military branch, branche ...

U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

operations as part of

Operation Ursula. At least two

Republican freighters, one

Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and another

Panamanian

Panamanians (; feminine ) are people identified with Panama, a country in Central America (which is the central section of the American continent), and with residential, legal, historical, or cultural connections with North America. For most Pan ...

were either sunk or forced to run aground by Italian destroyers near the

Strait of Sicily

The Strait of Sicily (also known as Sicilian Strait, Sicilian Channel, Channel of Sicily, Sicilian Narrows and Pantelleria Channel; or the ; or , ' or ') is the strait between Sicily and Tunisia. The strait is about wide and divides the Ty ...

. Two light cruisers took part in the shelling of

Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

and

Valencia

Valencia ( , ), formally València (), is the capital of the Province of Valencia, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, the same name in Spain. It is located on the banks of the Turia (r ...

in 1937, resulting in the deaths of more than 30 civilians.

Albania

In 1939, the supported the

invasion of Albania

The Italian invasion of Albania was a brief military campaign which was launched by Italy against Albania in 1939. The conflict was a result of the imperialistic policies of the Italian prime minister and dictator Benito Mussolini. Albania ...

. All ground forces involved in the invasion had to cross the

Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

from mainland Italy and the crossings were accomplished without incident.

World War II

On 10 June 1940, after the German

invasion of France,

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

declared war on

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and entered World War II. Italian dictator

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

saw the control of the

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

as an essential prerequisite for expanding his "New Roman Empire" into

Nice

Nice ( ; ) is a city in and the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative city limits, with a population of nearly one million[Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...]

,

Tunis

Tunis (, ') is the capital city, capital and largest city of Tunisia. The greater metropolitan area of Tunis, often referred to as "Grand Tunis", has about 2,700,000 inhabitants. , it is the third-largest city in the Maghreb region (after Casabl ...

and the

Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

. Italian naval building accelerated during his tenure. Mussolini described the Mediterranean as "

Mare Nostrum

In the Roman Empire, () was a term that referred to the Mediterranean Sea. Meaning "Our Sea" in Latin, it denoted the body of water in the context of borders and policy; Ancient Rome, Rome remains the only state in history to have controlled th ...

" (Our Sea).

[Mollo, p. 94]

Before the declaration of war, Italian ground and air forces had prepared to strike at the beaten French forces across the border in the

Italian invasion of France

The Italian invasion of France (10–25 June 1940), also called the Battle of the Alps, was the first major Fascist Italy, Italian engagement of World War II and the last major engagement of the Battle of France.

The Italian entry into the war ...

. By contrast, the prepared to secure the lines of communications between Italy,

Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

and the

East African colonies. The Italian High Command (''

Comando Supremo

''Comando Supremo'' (Supreme Command) was the highest command echelon of the Italian Armed Forces between June 1941 and May 1945. Its predecessor, the ''Stato Maggiore Generale'' (General Staff), was a purely advisory body with no direct control ...

'') did not approve of the plan devised by the Italian Naval Headquarters (''

Supermarina'') to occupy a weakly defended

Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

,

[Piekalkiewicz, p. 82] which proved a crucial mistake. British High Command, thinking that Malta could not be defended because of the proximity of

Regia Aeronautica air bases in

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

,

Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

, and

Libya

Libya, officially the State of Libya, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya border, the east, Sudan to Libya–Sudan border, the southeast, Chad to Chad–L ...

, had put little effort into bolstering the islands' defences. Thus, at the outset of the war there were only 42 anti-aircraft guns on the island and twelve

Gloster Sea Gladiators, half sitting in crates at the wharf.

[Taylor 1974, p. 181.]

Entering the war, the was operating under a number of limitations. Though significant assets were available to challenge the Royal Navy for control of the Mediterranean, there had been a lack of emphasis on the incorporation of technological advances such as

radar

Radar is a system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), direction ( azimuth and elevation angles), and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It is a radiodetermination method used to detect and track ...

and

sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigate, measure distances ( ranging), communicate with or detect objects o ...

. This meant that in night engagements or foul weather, the Italian ships were unable to detect the approach of their British adversaries. When engaged, they could only range their guns if they were able to visually locate their targets.

The had six battleships with which to contend for control of the Mediterranean, the four most modern of which were being re-fitted at the outbreak of the war. In addition to the six capital ships, the Italians had 19 cruisers, 59 destroyers, 67 torpedo boats, and 116 submarines. Though the had a number of fast new cruisers with good range in their gunnery, the older classes were lightly built and had inadequate defensive armor. Numerically the Italian fleet was formidable, but there were a large number of older vessels, and the service suffered in general from insufficient time at sea for crew training.

Italy's lack of raw materials meant that it would have great difficulty building new ships over the course of the war. Thus, the assets that it had were handled with caution by ''Supermarina''. Allied commanders at sea had a fair degree of autonomy and discretion to fight their vessels as circumstance allowed, but Italian commanders were required to confer with their headquarters before committing their forces in an engagement that might result in their loss. That led to delays in arriving at decisions and actions being avoided even when the Italians had a clear advantage. An example occurred during "

Operation Hats" in which the had superior forces but failed to commit them to take advantage of the opportunity.

A further key disadvantage in the convoy support and interception battles that dominated the

Battle of the Mediterranean

The Battle of the Mediterranean was the name given to the naval campaign fought in the Mediterranean Sea during World War II, from 10 June 1940 to 2 May 1945.

For the most part, the campaign was fought between the Kingdom of Italy, Italian Reg ...

was the intelligence advantage granted to the British in intercepting

German ''Ultra'' and, through this, the key information on Italian convoy routes, times of departure, time of arrival, and make up of the convoy.

The warships of the had a general reputation as being well-designed. Italian small attack craft lived up to expectations and were responsible for many successful actions in the Mediterranean. Though Italian warships lacked

radar

Radar is a system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), direction ( azimuth and elevation angles), and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It is a radiodetermination method used to detect and track ...

, that was partly offset in fair weather by good optical

rangefinder

A rangefinder (also rangefinding telemeter, depending on the context) is a device used to Length measurement, measure distances to remote objects. Originally optical devices used in surveying, they soon found applications in other fields, suc ...

and

fire-control

A fire-control system (FCS) is a number of components working together, usually a gun data computer, a Director (military), director and radar, which is designed to assist a ranged weapon system to target, track, and hit a target. It performs th ...

systems.

The Italian Navy lacked a fleet air arm. The High Command had reasoned that since the Italian navy would be operating solely in the Mediterranean, their vessels would never be far from an airfield and so the time and the resources needed to develop a naval air arm could be directed elsewhere. This proved problematic on a number of occasions. The Italians had the aircraft carriers and under construction at the start of the war, but neither was ever completed.

Lastly, the lack of natural oil reserves and subsequent shortage of oil precluded extensive fleet operations.

Mediterranean

The and the Royal Navy engaged in a two-and-a-half-year struggle for control of the Mediterranean. The 's primary goal was to support the Axis forces in

North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

while obstructing the supply route to

Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

and cutting off supplies to Malta. The Royal Navy's major effort was to maintain supply to the military forces and people of Malta, and secondarily to interdict convoy shipments to North Africa.

[Coggins p. 179] The first major action occurred on 11 November 1940 when the British aircraft carrier launched two waves of

Fairey Swordfish

The Fairey Swordfish is a retired biplane torpedo bomber, designed by the Fairey Aviation Company. Originating in the early 1930s, the Swordfish, nicknamed "Stringbag", was principally operated by the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy. It was a ...

torpedo-bombers in a

surprise raid against the Italian Fleet moored at the naval base of

Taranto

Taranto (; ; previously called Tarent in English) is a coastal city in Apulia, Southern Italy. It is the capital of the province of Taranto, serving as an important commercial port as well as the main Italian naval base.

Founded by Spartans ...

. The raid came in undetected, and three battleships were sunk. Another major defeat was inflicted on the at

Cape Matapan, where the Royal Navy and the

Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is the navy, naval branch of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The professional head of the RAN is Chief of Navy (Australia), Chief of Navy (CN) Vice admiral (Australia), Vice Admiral Mark Hammond (admiral), Ma ...

intercepted and destroyed three heavy cruisers (, and ; all of the same class) and two

s in a night ambush, with the loss of over 2,300 seamen. The Allies had

broken the Italian codes and the

Ultra intercepts uncovered the Italian movements and

radar

Radar is a system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), direction ( azimuth and elevation angles), and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It is a radiodetermination method used to detect and track ...

, which enabled them to locate the ships and range their weapons at distance and at night. The better air reconnaissance skills of the Royal Navy's

Fleet Air Arm

The Fleet Air Arm (FAA) is the naval aviation component of the United Kingdom's Royal Navy (RN). The FAA is one of five :Fighting Arms of the Royal Navy, RN fighting arms. it is a primarily helicopter force, though also operating the Lockhee ...

and their close collaboration with surface units were other major causes of the Italian debacle.

On 19 December 1941, the battleships and were damaged by

limpet mine

A limpet mine is a type of naval mine attached to a target by magnets. It is so named because of its superficial similarity to the shape of the limpet, a type of sea snail that clings tightly to rocks or other hard surfaces.

A swimmer or diver m ...

s planted by Italian

frogmen, knocking both out of the conflict for almost two years. This

action, coming on the heels of the loss of the ''Prince of Wales'' and ''Repulse'' in the South China Sea, significantly weakened the surface strength of the Royal Navy, making it difficult for them to challenge Italian control of the eastern Mediterranean.

On the night of 19 December,

Force K, comprising three cruisers and four destroyers based at

Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

, ran into an Italian minefield off

Tripoli. Three cruisers struck mines, with the

cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several operational roles from search-and-destroy to ocean escort to sea ...

lost, along with the

destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

. In addition, another destroyer was seriously damaged. All told 800 seamen were lost, and Force K, which had been effectively interdicting Axis convoys, was put out of action. This series of successes allowed the to achieve naval supremacy in the central Mediterranean. Coupled with an intensive bombing campaign against Malta, the Axis supply routes from southern Europe to North Africa were almost untouched by the Royal Navy or its allies for the next several months.

The Italian fleet went on the offensive, blocking or mauling three large Allied convoys bound for Malta. This led to a number of naval engagements, including the

Second Battle of Sirte in March 1942,

Operation Harpoon and

Operation Vigorous, (known as the "Battle of Mid-June") and

Operation Pedestal

Operation Pedestal (, Battle of mid-August), known in Malta as (), was a British operation to carry supplies to the island of Malta in August 1942, during the Second World War. British ships, submarines and aircraft from Malta attacked Axis p ...

(the "Battle of Mid-August"). All of these engagements ended favourably for the Axis. Despite this activity, the only real success of the Italian fleet was the surface attack on the Harpoon convoy, supported by Axis aerial forces. These attacks sank several Allied warships and damaged others. Only two transports of the original six in the convoy reached Malta. This was the only undisputed squadron-sized victory for Italian surface forces in World War II.

Despite the heavy losses suffered by the merchantmen and escorting forces of convoy Pedestal, the oil and supplies brought through allowed the near starving island of Malta to continue to hold out. With Allied landings in North Africa,

Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8–16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa whil ...

, in November 1942, the fortunes of war turned against the Italians. Their sea convoys were harassed day after day by the aerial and naval supremacy of the Allies. The maritime lane between Sicily and Tunisia became known as the "route of death". After years of back and forth, the Axis forces were forced to surrender in Tunisia, bringing the campaign for North Africa to a close.

The performed well and bravely in its North African convoy duties, but remained at a technical disadvantage. The Italian ships relied on speed but could easily be damaged by shell or torpedo, due to their relatively thin armour, as happened in the

Battle of Cape Spada. The fatal and final blow to the Italian Navy was a shortage of fuel, which forced its main units to remain at anchor for most of the last year of the Italian alliance with Germany.

Atlantic

From 10 June 1940, submarines of the took part in the

Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allies of World War II, ...

alongside the U-boats of

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

's ''

Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official military branch, branche ...

''. The Italian submarines were based in

Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( ; ; Gascon language, Gascon ; ) is a city on the river Garonne in the Gironde Departments of France, department, southwestern France. A port city, it is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the Prefectures in F ...

,

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

at the

BETASOM base. While more suited for the Mediterranean Sea than the

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

, the thirty-two Italian submarines that operated in the Atlantic sank 109 Allied ships for a total of 593,864 tons.

The even planned an attack on

New York Harbor

New York Harbor is a bay that covers all of the Upper Bay. It is at the mouth of the Hudson River near the East River tidal estuary on the East Coast of the United States.

New York Harbor is generally synonymous with Upper New York Bay, ...

with midget submarines for December 1942, but this plan was delayed for many reasons and was never carried out.

Red Sea

Initially, Italian forces enjoyed considerable success in East Africa. From 10 June 1940, the 's

Red Sea Flotilla, based at

Massawa

Massawa or Mitsiwa ( ) is a port city in the Northern Red Sea Region, Northern Red Sea region of Eritrea, located on the Red Sea at the northern end of the Gulf of Zula beside the Dahlak Archipelago. It has been a historically important port for ...

,

Eritrea

Eritrea, officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa, with its capital and largest city being Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia in the Eritrea–Ethiopia border, south, Sudan in the west, and Dj ...

, posed a potential threat to Allied shipping crossing the

Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

between the

Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

and the Mediterranean Sea. This threat increased in August 1940 with the

Italian conquest of British Somaliland, which allowed the Italians the use of the port of

Berbera

Berbera (; , ) is the capital of the Sahil, Somaliland, Sahil region of Somaliland and is the main sea port of the country, located approximately 160 km from the national capital, Hargeisa. Berbera is a coastal city and was the former capital of t ...

; in January 1941, however, British and

Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

forces launched a successful

counterattack

A counterattack is a tactic employed in response to an attack, with the term originating in "Military exercise, war games". The general objective is to negate or thwart the advantage gained by the enemy during attack, while the specific objecti ...

in East Africa and the threat posed by the Red Sea Flotilla disappeared.

Much of the Red Sea Flotilla was destroyed by hostile action during the first months of war or when the port of Massawa fell in April 1941. However, there were a few survivors. In February 1941, prior to the fall of Massawa, the colonial ship and the

auxiliary cruisers and broke out and sailed to

Kobe

Kobe ( ; , ), officially , is the capital city of Hyōgo Prefecture, Japan. With a population of around 1.5 million, Kobe is Japan's List of Japanese cities by population, seventh-largest city and the third-largest port city after Port of Toky ...

,

Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

. While ''Ramb I'' was sunk by the

Royal New Zealand Navy

The Royal New Zealand Navy (RNZN; ) is the maritime arm of the New Zealand Defence Force. The fleet currently consists of eight ships. The Navy had its origins in the Naval Defence Act 1913, and the subsequent acquisition of the cruiser , whi ...

cruiser off the

Maldives

The Maldives, officially the Republic of Maldives, and historically known as the Maldive Islands, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in South Asia located in the Indian Ocean. The Maldives is southwest of Sri Lanka and India, abou ...

, ''Eritrea'' and ''Ramb II'' made it to Kobe. As the port of Massawa was falling, four submarines—, , , and —sailed south from Massawa, rounded the

Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

and ultimately sailed to

German occupied Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( ; ; Gascon language, Gascon ; ) is a city on the river Garonne in the Gironde Departments of France, department, southwestern France. A port city, it is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the Prefectures in F ...

,

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

. One or two Italian merchant ships from the Red Sea Flotilla made it to

Vichy French-controlled

Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

.

On 10 June 1941, the British launched Operation Chronometer, landing a battalion of troops from the

British Indian Army

The Indian Army was the force of British Raj, British India, until Indian Independence Act 1947, national independence in 1947. Formed in 1895 by uniting the three Presidency armies, it was responsible for the defence of both British India and ...

at

Assab

Assab or Aseb (, ) is a port city in the Southern Red Sea Region of Eritrea. It is situated on the west coast of the Red Sea.

Languages spoken in Assab are predominantly Afar language, Afar, Tigrinya language, Tigrinya, and Arabic. After the Ita ...

, the last Italian-held harbour on the Red Sea. By 11 June, Assab had fallen. Two days later, on 13 June, the Indian trawler ''Parvati'' became the last naval casualty of the East African Campaign when it struck a moored mine near Assab.

Black Sea

In May 1942, at German request, the deployed four 24-ton torpedo motorboats (''Motoscafo Armato Silurante'',

MAS), six s, five torpedo motorboats, and five explosive motorboats to the

Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

. The vessels were transported overland to the

Danube River

The Danube ( ; see also other names) is the second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest south into the Black Sea. A large and historically important riv ...

at

Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

,

Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

, and then transported by water to

Constanța

Constanța (, , ) is a city in the Dobruja Historical regions of Romania, historical region of Romania. A port city, it is the capital of Constanța County and the country's Cities in Romania, fourth largest city and principal port on the Black ...

,

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

. The flotilla had an active and successful campaign, based at

Yalta

Yalta (: ) is a resort town, resort city on the south coast of the Crimean Peninsula surrounded by the Black Sea. It serves as the administrative center of Yalta Municipality, one of the regions within Crimea. Yalta, along with the rest of Crime ...

and

Feodosia.

After Italy quit the war, most of the Italian vessels on the Black Sea were transferred to

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

's ''

Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official military branch, branche ...

''. In early 1944, six MAS boats were transferred to the

Royal Romanian Navy. By August 1944, they were ultimately captured by Soviet forces when

Constanța

Constanța (, , ) is a city in the Dobruja Historical regions of Romania, historical region of Romania. A port city, it is the capital of Constanța County and the country's Cities in Romania, fourth largest city and principal port on the Black ...

was captured.

The five surviving midget submarines were transferred to the Royal Romanian Navy.

Lake Ladoga

The operated

a squadron of four MAS boats on

Lake Ladoga

Lake Ladoga is a freshwater lake located in the Republic of Karelia and Leningrad Oblast in northwestern Russia, in the vicinity of Saint Petersburg.

It is the largest lake located entirely in Europe, the second largest lake in Russia after Lake ...

during the

Continuation War

The Continuation War, also known as the Second Soviet–Finnish War, was a conflict fought by Finland and Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union during World War II. It began with a Finnish declaration of war on 25 June 1941 and ended on 19 ...

(1941–1944). As part of

Naval Detachment K, German, Italian, and Finnish vessels operated against Soviet gunboats, escorts and supply vessels during the

Siege of Leningrad

The siege of Leningrad was a Siege, military blockade undertaken by the Axis powers against the city of Leningrad (present-day Saint Petersburg) in the Soviet Union on the Eastern Front (World War II), Eastern Front of World War II from 1941 t ...

between 21 June and 21 October 1942. The Italian vessels were ultimately turned over to Finland.

Far East

The had a naval base in the

concession territory of

Tientsin in

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

. The primary Italian vessels based in China were the mine-layer ''

Lepanto'' and the gunboat . During World War II, Italian supply ships, auxiliary cruisers and submarines operated throughout the waters of the Far East, often in disguise. The Italians also utilized Japanese-controlled port facilities such as

Shanghai, China

Shanghai, Shanghainese: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: is a direct-administered municipality and the most populous urban area in China. The city is located on the Chinese shoreline on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the ...

, and

Kobe

Kobe ( ; , ), officially , is the capital city of Hyōgo Prefecture, Japan. With a population of around 1.5 million, Kobe is Japan's List of Japanese cities by population, seventh-largest city and the third-largest port city after Port of Toky ...

,

Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

.

Seven Italian submarines operating from France were converted by the Italians into "

transport submarines" in order to exchange rare or irreplaceable trade goods with Japan. The submarines , , , , , , and were converted for service with the ''

Monsun Gruppe'' ("Monsoon Group"). The name of ''Comandante Cappellini'' was changed to .

Twelve additional

R-class blockade running transport submarines were specifically designed for trade with the Far East, but only two of these vessels were completed before Italy quit the war. Both of these submarines were destroyed by Allied action almost as soon as they were launched.

Armistice of 1943

In 1943, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was deposed and the new Italian government agreed to an

armistice with the Allies. Under the terms of this armistice, the had to sail its ships to an Allied port. Most sailed to Malta, but a flotilla from

La Spezia

La Spezia (, or ; ; , in the local ) is the capital city of the province of La Spezia and is located at the head of the Gulf of La Spezia in the southern part of the Liguria region of Italy.

La Spezia is the second-largest city in the Liguria ...

headed towards

Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

. This was intercepted and attacked by German aircraft and the battleship was sunk by two hits from

Fritz X

Fritz X was a German guided anti-ship glide bomb used during World War II. Developed alongside the Henschel Hs 293, ''Fritz X'' was one of the first precision guided weapons deployed in combat. ''Fritz X'' was a nickname used both by Allied an ...

guided glide-bombs. Among the 1600 sailors killed on board ''Roma'' was the Italian Naval Commander-in-Chief, Admiral

Carlo Bergamini.

As vessels became available to the new Italian government, the

Italian Co-Belligerent Navy was formed to fight on the side of the Allies. Other ships were captured in port by the Germans or scuttled by their crews. Few crews chose to fight for Mussolini's new fascist regime in northern Italy, the

Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic (, ; RSI; , ), known prior to December 1943 as the National Republican State of Italy (; SNRI), but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò (, ), was a List of World War II puppet states#Germany, German puppe ...

(''Repubblica Sociale Italiana'', RSI). Mussolini's pro-German National Republican Navy (''Marina Nazionale Repubblicana'') hardly reached a twentieth the size attained by the co-belligerent Italian fleet. In the Far East, the Japanese occupied the Italian concession territory of Tiensin.

There was little use for the surrendered Italian battleships and there was doubt about the loyalties of the crews, so these ships were interned in Egypt. In June 1944, the less powerful battleships (''Andrea Doria'', ''Duilio'' and ''Giulio Cesare'') were allowed to return to

Augusta harbour in

Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

for training. The others, and ''Italia'' (ex-), remained at

Ismaïlia in the

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

until 1947. After the war, ''Giulio Cesare'' was passed to the Soviet Union.

In the Co-belligerency period, until

"VE" (Victory in Europe) Day, Italian light cruisers participated in the naval war in the Atlantic Ocean with patrols against German raiders. Smaller naval units (mainly submarines and torpedo boats) served in the Mediterranean Sea. In the last days of war, the issue of whether Italian battleships and cruisers should participate in the

Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

was debated by the Allied leaders.

There were also Italian naval units in the Far East in 1943 when the new Italian government agreed to an armistice with the Allies. The reactions of their crews varied greatly. In general, surface units, mainly supply ships and auxiliary cruisers, either surrendered at Allied ports (''Eritrea'' at

Colombo

Colombo, ( ; , ; , ), is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. The Colombo metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of 5.6 million, and 752,993 within the municipal limits. It is the ...

,

Ceylon

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

) or, if in Japanese controlled ports, they were scuttled by their own crew (''Conte Verde'', ''Lepanto'', and ''Carlotto'' at

Shanghai

Shanghai, Shanghainese: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: is a direct-administered municipality and the most populous urban area in China. The city is located on the Chinese shoreline on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the ...

). ''Ramb II'' was taken over by the Japanese in Kobe and renamed ''Calitea II''. Four Italian submarines were in the Far East at the time of the armistice, transporting rare goods to Japan and Singapore: , (), , and . The crew of ''Ammiraglio Cagni'' heard of the armistice and surrendered to the Royal Navy off

Durban

Durban ( ; , from meaning "bay, lagoon") is the third-most populous city in South Africa, after Johannesburg and Cape Town, and the largest city in the Provinces of South Africa, province of KwaZulu-Natal.

Situated on the east coast of South ...

,

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

. ''Comandante Cappellini'', ''Reginaldo Giuliani'', and ''Luigi Torelli'' and their crews were temporarily interned by the Japanese. The boats passed to German U-boat command and, with mixed German and Italian crews, they continued to fight against the Allies. The German navy assigned new officers to the three submarines. The three were renamed , and and took part in German war operations in the Pacific. ''Reginaldo Giuliani'' was sunk by the British submarine in February 1944. In May 1945, the other two vessels were taken over by the

Japanese Imperial Navy when Germany surrendered. About twenty Italian sailors continued to fight with the Japanese. ''Luigi Torelli'' remained active until 30 August 1945, when, in Japanese waters, this last Fascist Italian submarine shot down a

North American B-25 Mitchell

The North American B-25 Mitchell is an American medium bomber that was introduced in 1941 and named in honor of Brigadier General Billy Mitchell, William "Billy" Mitchell, a pioneer of U.S. military aviation. Used by many Allies of World War ...

bomber of the

United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

.

[Willmott, H P (2009). ''The Last Century of Sea Power: From Port Arthur to Chanak, 1894–1922''.

Indiana University Press, p. 276. ]

After World War II

After the end of hostilities, the started a long and complex rebuilding process. At the beginning of the war, the was the fourth largest navy in the world with a mix of modernised and new battleships. The important combat contributions of the Italian naval forces after the signing of the armistice with the Allies on 8 September 1943 and the subsequent cooperation agreement on 23 September 1943 left the in a poor condition. Much of its infrastructure and bases were unusable and its ports mined and blocked by sunken ships. However, a large number of its naval units had survived the war, albeit in a low efficiency state. This was due to the conflict and the age of many vessels.

The vessels that remained were:

* 2 incomplete and damaged aircraft carriers

* 5 battleships

* 9 cruisers

* 11 destroyers

* 22 frigates

* 19 corvettes

* 44 fast coastal patrol units

* 50 minesweepers

* 16 amphibious operations vessels

* 2 school ships

* 1 support ship and plane transport

* various submarine units

On 2 June 1946, the Italian monarchy was abolished by a popular referendum. The Kingdom of Italy (''Regno d'Italia'') ended and was replaced by the

Italian Republic

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

(''Repubblica Italiana''). The became the Navy of the Italian Republic (''Marina Militare'').

Peace treaty

On 10 February 1947, a

peace treaty

A peace treaty is an treaty, agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually country, countries or governments, which formally ends a declaration of war, state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice, which is an ag ...

was signed in

Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

between the Italian Republic and the victorious powers of World War II. The treaty was onerous for the Italian Navy. Apart from territorial and material losses, the following restrictions were imposed:

* A ban on owning, building or experimenting with atomic weapons, self-propulsion projectiles or related launchers

* A ban on owning battleships, aircraft carriers, submarines and amphibious assault units.

* A ban on operating military installations on the islands of

Pantelleria

Pantelleria (; ), known in ancient times as Cossyra or Cossura, is an Italian island and comune in the Strait of Sicily in the Mediterranean Sea, southwest of Sicily and east of the Tunisian coast. On clear days Tunisia is visible from the ...

and

Pianosa; and the

Pelagie Islands

The Pelagie Islands (; ), from the Greek , meaning "open sea", are the three small islands of Lampedusa, Lampione, and Linosa, located in the Mediterranean Sea between Malta and Tunisia, south of Sicily. To the northwest lie the island of Pa ...

.

* The total displacement, battleships excluded, of the future navy was not allowed to be greater than 67,500 tons, while the staff was capped at 25,000 men.

The treaty also ordered Italy to put the following ships at the disposals of the victorious nations

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, Soviet Union, Great Britain, France,

Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

,

Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

, and Albania as war compensation:

* 3 battleships: , , ;

* 5 cruisers: , , , and ;

* 7 destroyers; 5 of the , and ;

* 6 minesweepers;

* 8 submarines, including three of the ;

* 1 sailing school ship: .

The convoy escort ultimately became the Yugoslav Navy yacht . ''Galeb'' was used by the late

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

of the

Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (commonly abbreviated as SFRY or SFR Yugoslavia), known from 1945 to 1963 as the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as Socialist Yugoslavia or simply Yugoslavia, was a country ...

Marshal

Marshal is a term used in several official titles in various branches of society. As marshals became trusted members of the courts of Middle Ages, Medieval Europe, the title grew in reputation. During the last few centuries, it has been used fo ...

Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito ( ; , ), was a Yugoslavia, Yugoslav communist revolutionary and politician who served in various positions of national leadership from 1943 unti ...

on his numerous foreign trips and to entertain heads of state.

Ships

Pre–World War I

Battleships

World War I

Battleships

Cruisers

Destroyers

World War II

Aircraft carriers

* (modification of the liner ''Roma'', built but never used)

* (modification of the liner ''Augustus'', never completed)

Seaplane carriers

* (extensively converted merchant ship ''Città di Messina'' for the seaplane carrier role, commissioned as a seaplane transport by 1940)

Battleships

Heavy cruisers

Light cruisers

Aviation and transport cruisers

* ''Bolzano'' class: aviation and transport cruiser (as regular heavy cruiser, extensively damaged by submarine torpedoes and proposed for reconstruction to a hybrid carrier/transport design)

Destroyers

Torpedo boats

* : 30 vessels

**

**