Rotunda Assembly Room on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Blackfriars Rotunda was a building in

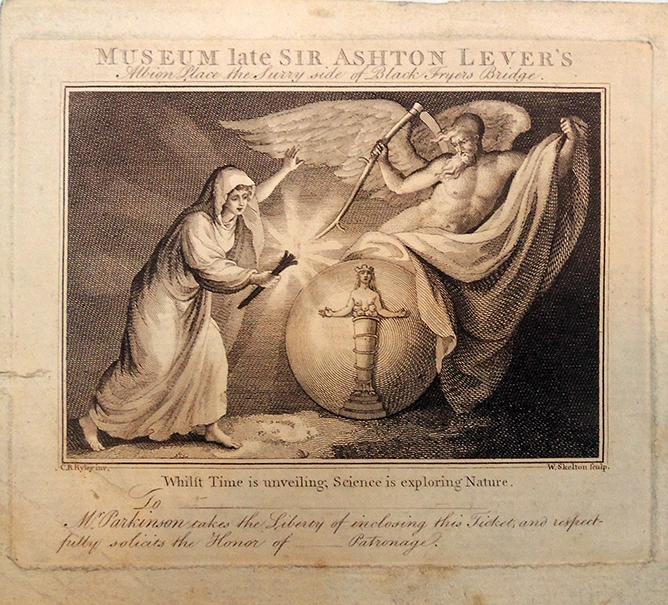

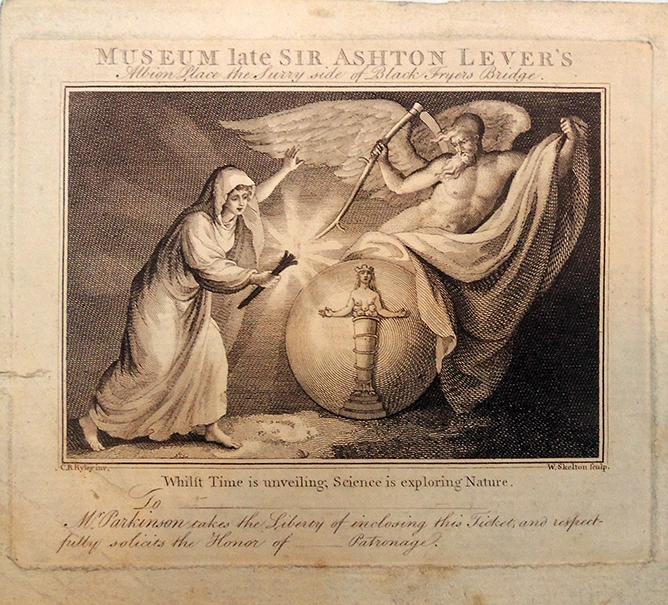

James Parkinson came into possession of the collection of Sir Ashton Lever quite by chance: Lever put it up as a lottery prize, Parkinson's wife bought two tickets, gave one away, and died before the time the lottery draw was carried out.

James Parkinson came into possession of the collection of Sir Ashton Lever quite by chance: Lever put it up as a lottery prize, Parkinson's wife bought two tickets, gave one away, and died before the time the lottery draw was carried out.

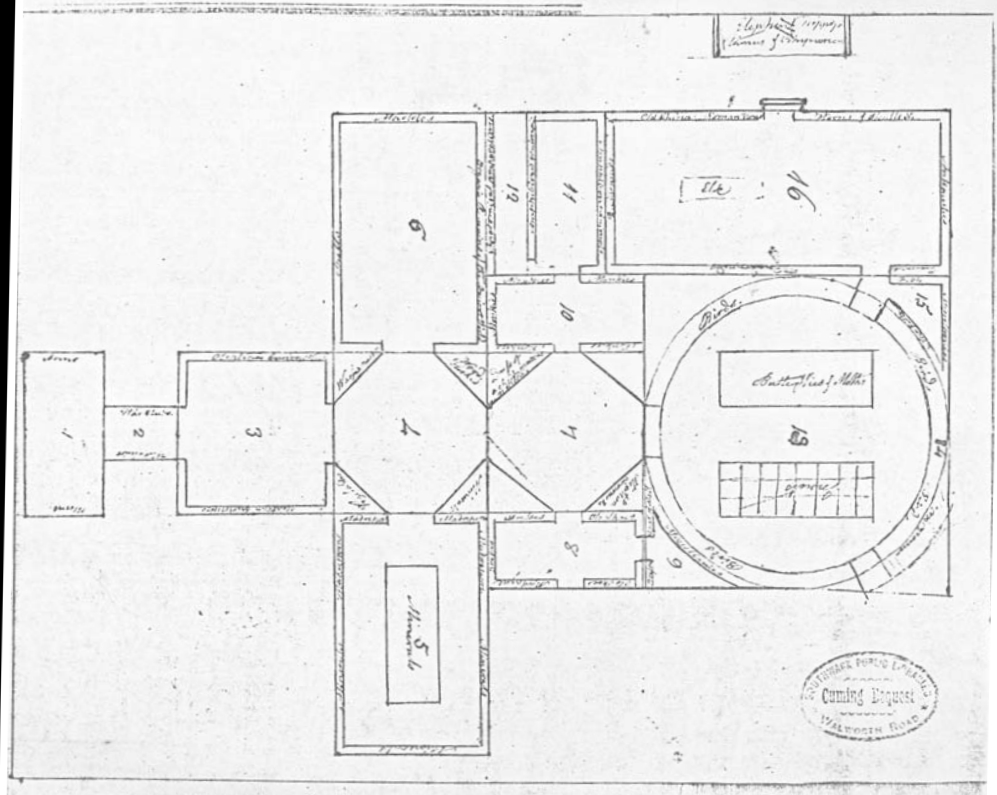

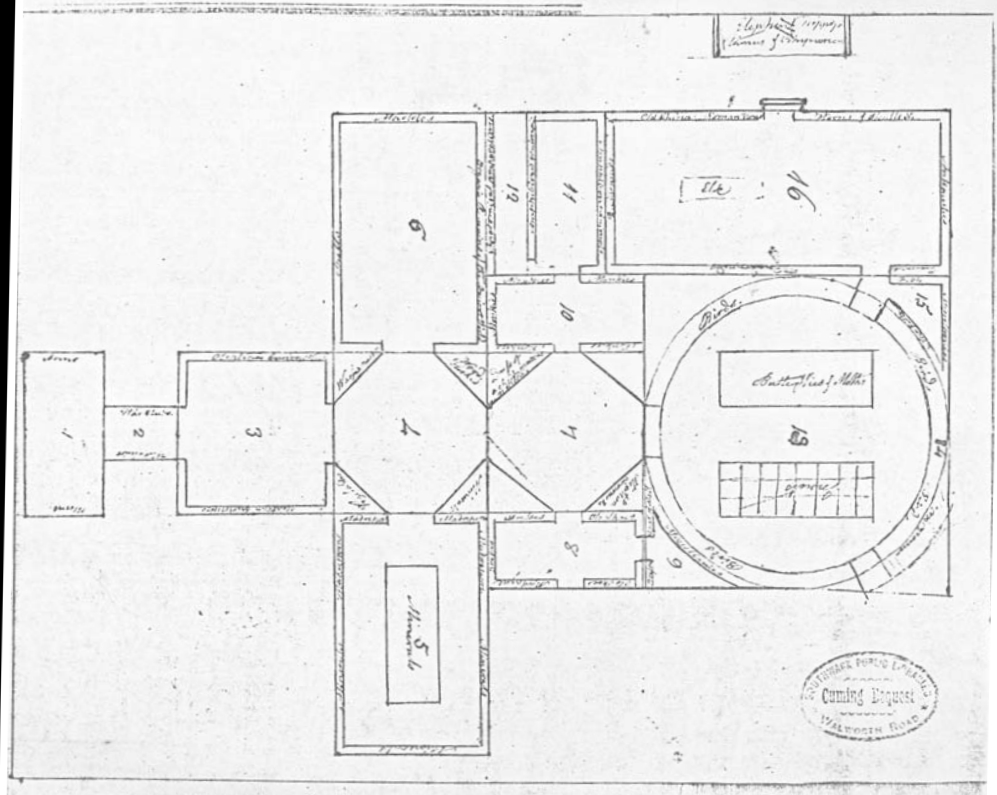

/ref>). The layout is believed to be documented only by a single surviving sketched floor plan. The Leverian collection was moved in from Leicester House in 1788. At the time the nearby buildings on Albion Place were industrial: the British Glass Warehouse by the side of the river (in business from 1773), and the Albion Mills over the street (burned down in 1791).

A catalogue and guide was printed in 1790. He also had George Shaw write an illustrated scientific work.

A catalogue and guide was printed in 1790. He also had George Shaw write an illustrated scientific work.

Parkinson had some success in getting naturalists to attend the museum, which was easier at the time to visit than the

Parkinson had some success in getting naturalists to attend the museum, which was easier at the time to visit than the

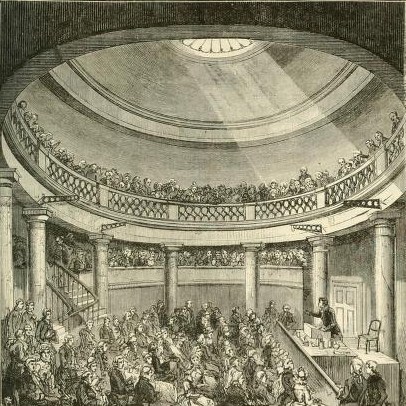

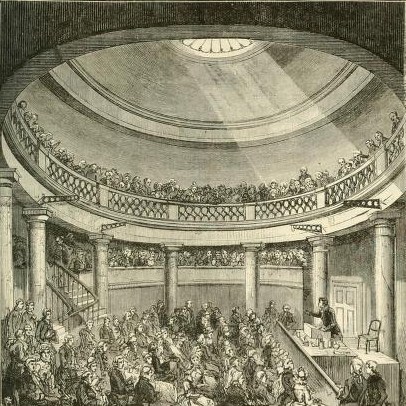

The building was adapted to public lectures, in a large theatre. There were other public rooms:

The building was adapted to public lectures, in a large theatre. There were other public rooms:

by Edward Walford (1878) pp. 368-383. It also hosted a In May or June 1830

In May or June 1830

Google Books

Google Books

PDF

Numerous identifications of purchasers from the Leverian collection sale. {{coord, 51.50791, N, 0.10476, W, type:landmark_region:GB, display=title Former buildings and structures in the London Borough of Southwark Radicalism (historical)

Southwark

Southwark ( ) is a district of Central London situated on the south bank of the River Thames, forming the north-western part of the wider modern London Borough of Southwark. The district, which is the oldest part of South London, developed ...

, near the southern end of Blackfriars Bridge

Blackfriars Bridge is a road and foot traffic bridge over the River Thames in London, between Waterloo Bridge and Blackfriars Railway Bridge, carrying the A201 road. The north end is in the City of London near the Inns of Court and Temple Chur ...

across the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the ...

in London, that existed from 1787 to 1958 in various forms. It initially housed the collection of the Leverian Museum

The Leverian collection was a natural history and ethnographic collection assembled by Ashton Lever. It was noted for the content it acquired from the voyages of Captain James Cook. For three decades it was displayed in London, being broken up ...

after it had been disposed of by lottery. For a period it was home to the Surrey Institution

The Surrey Institution was an organisation devoted to scientific, literary and musical education and research, based in London. It was founded by private subscription in 1807, taking the Royal Institution, founded in 1799, as a model.The Microcos ...

. In the early 1830s it notoriously was the centre for the activities of the Rotunda radicals

The Rotunda radicals, known at the time as Rotundists or Rotundanists, were a diverse group of social, political and religious radical reformers who gathered around the Blackfriars Rotunda, London, between 1830 and 1832, while it was under the mana ...

. Its subsequent existence was long but less remarkable.

James Parkinson and the Leverian collection

James Parkinson came into possession of the collection of Sir Ashton Lever quite by chance: Lever put it up as a lottery prize, Parkinson's wife bought two tickets, gave one away, and died before the time the lottery draw was carried out.

James Parkinson came into possession of the collection of Sir Ashton Lever quite by chance: Lever put it up as a lottery prize, Parkinson's wife bought two tickets, gave one away, and died before the time the lottery draw was carried out.

Construction of the Rotunda

After trying to run the museum in its old location inLeicester Square

Leicester Square ( ) is a pedestrianised square in the West End of London, England. It was laid out in 1670 as Leicester Fields, which was named after the recently built Leicester House, itself named after Robert Sidney, 2nd Earl of Leicester ...

, but finding the rent too much, Parkinson with other investors put up the Rotunda Building; it was of his own design (along with his architect son Joseph Parkinson), was constructed by James Burton

James Edward Burton (born August 21, 1939, in Dubberly, Louisiana) is an American guitarist. A member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame since 2001 (his induction speech was given by longtime fan Keith Richards), Burton has also been recognized ...

, and was opened in 1787.

The Rotunda building had a central circular gallery and in brick; the roof was conical and in slate.'The borough of Southwark: Introduction', A History of the County of Surrey: Volume 4 (1912), pp. 125-135. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=43041 Date accessed: 14 March 2012. It was located on the south side of the Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the ...

, and at the time was in the county of Surrey. The dimensions were later given as 120 feet by 132 feet, i.e. 1760 square yards; originally the area was under 1000 square yards, however. It was located on Great Surrey Street, fronting on the Georgian terrace there (and was only later properly known as 3 Blackfriars Road, the street name being changed in 1829British History Online: Sir Howard Roberts and Walter H. Godfrey (editors), ''Survey of London: volume 22: Bankside (the parishes of St. Saviour and Christchurch Southwark)'' (1950), pp. 115-121./ref>). The layout is believed to be documented only by a single surviving sketched floor plan. The Leverian collection was moved in from Leicester House in 1788. At the time the nearby buildings on Albion Place were industrial: the British Glass Warehouse by the side of the river (in business from 1773), and the Albion Mills over the street (burned down in 1791).

Parkinson as museum owner

Parkinson made serious efforts to promote the collection as a commercial venture. A catalogue and guide was printed in 1790. He also had George Shaw write an illustrated scientific work.

A catalogue and guide was printed in 1790. He also had George Shaw write an illustrated scientific work.

Parkinson had some success in getting naturalists to attend the museum, which was easier at the time to visit than the

Parkinson had some success in getting naturalists to attend the museum, which was easier at the time to visit than the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docume ...

. A visitor in 1799, Heinrich Friedrich Link, was complimentary. A description a visit to the museum for children can be found in '' The School-Room Party'' (1800).

Disposal of the collection

As well as trying to build it up as a business, Parkinson also tried to sell the contents at various times. One attempt, a proposed purchase by the government, was wrecked by the adverse opinion ofSir Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the 1766 natural-history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. He took part in Captain James ...

. In the end, for financial reasons, Parkinson sold the collection in lots by auction in 1806. Among the buyers were Edward Donovan

Edward Donovan (1768 – 1 February 1837) was an Anglo-Irish writer, natural history illustrator, and amateur zoologist. He did not travel, but collected, described and illustrated many species based on the collections of other naturalists. H ...

, Edward Stanley, 13th Earl of Derby

Edward Smith-Stanley, 13th Earl of Derby (21 April 1775 – 30 June 1851), KG, of Knowsley Hall in Lancashire (styled Lord Stanley from 1776 to 1832, known as Baron Stanley of Bickerstaffe from 1832-4), was a politician, peer, landowner, b ...

, and William Bullock; many items went to other museums, including the Imperial Museum of Vienna

The Natural History Museum Vienna (german: Naturhistorisches Museum Wien) is a large natural history museum located in Vienna, Austria. It is one of the most important natural history museums worldwide.

The NHM Vienna is one of the largest museum ...

.

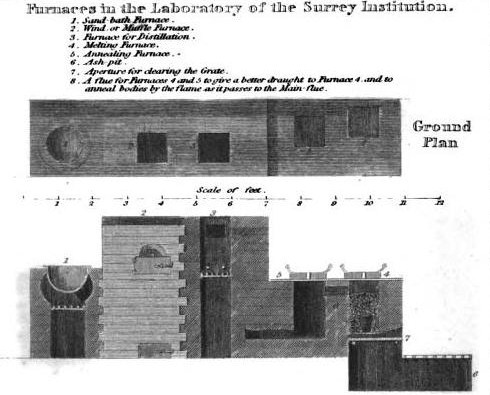

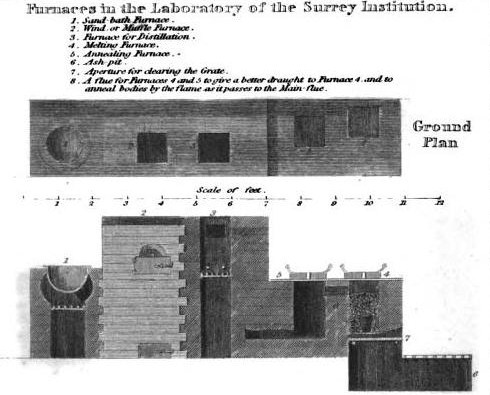

Adaptation for the Surrey Institution

When the Surrey Institution was being proposed, around 1807, the Rotunda Building (as it was then known) was adapted to the Institution's needs byJoseph T. Parkinson

Joseph T. Parkinson (1783 - May 1855, London) was an English architect.

He was the son of land agent and museum proprietor James Parkinson. He was articled to William Pilkington. He was a member of James Burton's Loyal British Artificers, a volu ...

, son of James Parkinson. The Institution ran into financial difficulties, and was closed down in 1823.

The building was adapted to public lectures, in a large theatre. There were other public rooms:

The building was adapted to public lectures, in a large theatre. There were other public rooms:

Adjoining the theatre and near the inclosed part appropriated to the lecturer, is the chemical laboratory, in which convenience, compactness, and elegance are united. Contiguous to it is the committee-room. On the other side of the theatre is the library, which is sixty feet in length, with a gallery on three sides, and an easy access to it by a flight of steps.

Later uses

The building from 1823 was used in a variety of ways until 1855, when it was put to ordinary business use, as the Royal Albion pub. In the 1820s it was a wine and concert room.British History Online, ''Old and New London: Volume 6''by Edward Walford (1878) pp. 368-383. It also hosted a

diorama

A diorama is a replica of a scene, typically a three-dimensional full-size or miniature model, sometimes enclosed in a glass showcase for a museum. Dioramas are often built by hobbyists as part of related hobbies such as military vehicle mode ...

(a peristrephic panorama as described at the time), and a book about its representation of the Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. The Greeks were later assisted ...

was published in 1828. Under the title Old Rotunda Assembly Rooms the Rotunda is also written into the early history of music hall, for the performances of variety acts offered there in 1829, including the extemporiser Charles Sloman

Charles Sloman (1808 – 22 July 1870) was an English comic entertainer, singer and songwriter, as well as a composer of ballads and sacred music. He was billed as "the only English ''Improvisatore''".

Biography

Born in Westminster into a J ...

.

In May or June 1830

In May or June 1830 Richard Carlile

Richard Carlile (8 December 1790 – 10 February 1843) was an important agitator for the establishment of universal suffrage and freedom of the press in the United Kingdom.

Early life

Born in Ashburton, Devon, he was the son of a shoemaker who ...

took over the Rotunda, and it became a centre for radical lectures and meetings. There were also waxworks and wild beasts. The Rotunda radicals

The Rotunda radicals, known at the time as Rotundists or Rotundanists, were a diverse group of social, political and religious radical reformers who gathered around the Blackfriars Rotunda, London, between 1830 and 1832, while it was under the mana ...

, known at the time as Rotundists or Rotundanists, were a diverse group of social, political and religious radical reformers who gathered there, between 1830 and 1832, during Carlile's tenure. During this period almost every well-known radical in London spoke there at meetings which were often rowdy. The Home Office regarded the Rotunda as a centre of violence, sedition and blasphemy, and regularly spied on its meetings. In 1831 it was described as the Surrey Rotunda on Albion Place (the area south of Blackfriars Bridge

Blackfriars Bridge is a road and foot traffic bridge over the River Thames in London, between Waterloo Bridge and Blackfriars Railway Bridge, carrying the A201 road. The north end is in the City of London near the Inns of Court and Temple Chur ...

, with the industrial buildings) leading to Albion Street.

From 1833 to 1838 it operated as the Globe Theatre; under John Blewitt it was called a "musick hall",Phyllis Hartnoll and Peter Found. "Rotunda, The." The Concise Oxford Companion to the Theatre. 1996. Encyclopedia.com. (March 14, 2012). http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1O79-RotundaThe.html and in 1838 the Rotunda was again a concert room. George Jacob Holyoake was teaching and lecturing there in 1843. At a later point it was the Britannia Music Hall. After an illegal cock fight was discovered, the Rotunda finally lost its entertainment licence, in 1886.

In 1912 the Rotunda was in use as a warehouse. The structure was damaged during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, and had been patched up by 1950. It was demolished in 1958.Parolin, p. 278Google Books

References

*Christina Parolin (2010), ''Radical Spaces: Venues of popular politics in London, 1790–c. 1845''Google Books

Notes

External links

*P. J. P. Whitehead, ''A Guide to the Dispersal of Zoological Material from Captain Cook's Voyages'', Pacific Studies, Vol 2, No 1 (1978)Numerous identifications of purchasers from the Leverian collection sale. {{coord, 51.50791, N, 0.10476, W, type:landmark_region:GB, display=title Former buildings and structures in the London Borough of Southwark Radicalism (historical)