Roman Mining on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The earliest metal manipulation was probably hammering (Craddock 1995, 1999), where copper ore was pounded into thin sheets. The ore (if there were large enough pieces of metal separate from mineral) could be beneficiated ('made better') before or after melting, where the prills of metal could be hand-picked from the cooled slag.

The earliest metal manipulation was probably hammering (Craddock 1995, 1999), where copper ore was pounded into thin sheets. The ore (if there were large enough pieces of metal separate from mineral) could be beneficiated ('made better') before or after melting, where the prills of metal could be hand-picked from the cooled slag.

Romans used many methods to create metal objects. Like

Romans used many methods to create metal objects. Like

From the formation of the Roman Empire, Rome was an almost completely closed

From the formation of the Roman Empire, Rome was an almost completely closed

Metals

A metal () is a material that, when polished or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electricity and heat relatively well. These properties are all associated with having electrons available at the Fermi level, as against no ...

and metal working

Metalworking is the process of shaping and reshaping metals in order to create useful objects, parts, assemblies, and large scale structures. As a term, it covers a wide and diverse range of processes, skills, and tools for producing objects on e ...

had been known to the people of modern Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

since the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

. By 53 BC, Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

had expanded to control an immense expanse of the Mediterranean. This included Italy and its islands, Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

, Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

, Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

and Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

; by the end of the Emperor Trajan

Trajan ( ; born Marcus Ulpius Traianus, 18 September 53) was a Roman emperor from AD 98 to 117, remembered as the second of the Five Good Emperors of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty. He was a philanthropic ruler and a successful soldier ...

's reign, the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

had grown further to encompass parts of Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, all of modern Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

west of the Rhine, Dacia, Noricum

Noricum () is the Latin name for the kingdom or federation of tribes that included most of modern Austria and part of Slovenia. In the first century AD, it became a province of the Roman Empire. Its borders were the Danube to the north, R ...

, Judea

Judea or Judaea (; ; , ; ) is a mountainous region of the Levant. Traditionally dominated by the city of Jerusalem, it is now part of Palestine and Israel. The name's usage is historic, having been used in antiquity and still into the pres ...

, Armenia

Armenia, officially the Republic of Armenia, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of West Asia. It is a part of the Caucasus region and is bordered by Turkey to the west, Georgia (country), Georgia to the north and Azerbaijan to ...

, Illyria

In classical and late antiquity, Illyria (; , ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; , ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyrians.

The Ancient Gree ...

, and Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

(Shepard 1993). As the empire grew, so did its need for metals.

Central Italy

Central Italy ( or ) is one of the five official statistical regions of Italy used by the National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), a first-level NUTS region with code ITI, and a European Parliament constituency. It has 11,704,312 inhabita ...

itself was not rich in metal ores, leading to necessary trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

Traders generally negotiate through a medium of cr ...

networks in order to meet the demand for metal. Early Italians had some access to metals in the northern regions of the peninsula in Tuscany

Tuscany ( ; ) is a Regions of Italy, region in central Italy with an area of about and a population of 3,660,834 inhabitants as of 2025. The capital city is Florence.

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, history, artistic legacy, and its in ...

and Cisalpine Gaul

Cisalpine Gaul (, also called ''Gallia Citerior'' or ''Gallia Togata'') was the name given, especially during the 4th and 3rd centuries BC, to a region of land inhabited by Celts (Gauls), corresponding to what is now most of northern Italy.

Afte ...

, as well as the islands Elba

Elba (, ; ) is a Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean island in Tuscany, Italy, from the coastal town of Piombino on the Italian mainland, and the largest island of the Tuscan Archipelago. It is also part of the Arcipelago Toscano National Park, a ...

and Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

. With the conquest of Etruria

Etruria ( ) was a region of Central Italy delimited by the rivers Arno and Tiber, an area that covered what is now most of Tuscany, northern Lazio, and north-western Umbria. It was inhabited by the Etruscans, an ancient civilization that f ...

in 275 BC and the subsequent acquisitions due to the Punic Wars

The Punic Wars were a series of wars fought between the Roman Republic and the Ancient Carthage, Carthaginian Empire during the period 264 to 146BC. Three such wars took place, involving a total of forty-three years of warfare on both land and ...

, Rome had the ability to stretch further into Transalpine Gaul

Gallia Narbonensis (Latin for "Gaul of Narbonne", from its chief settlement) was a Roman province located in Occitania (administrative region) , Occitania and Provence, in Southern France. It was also known as Provincia Nostra ("Our Prov ...

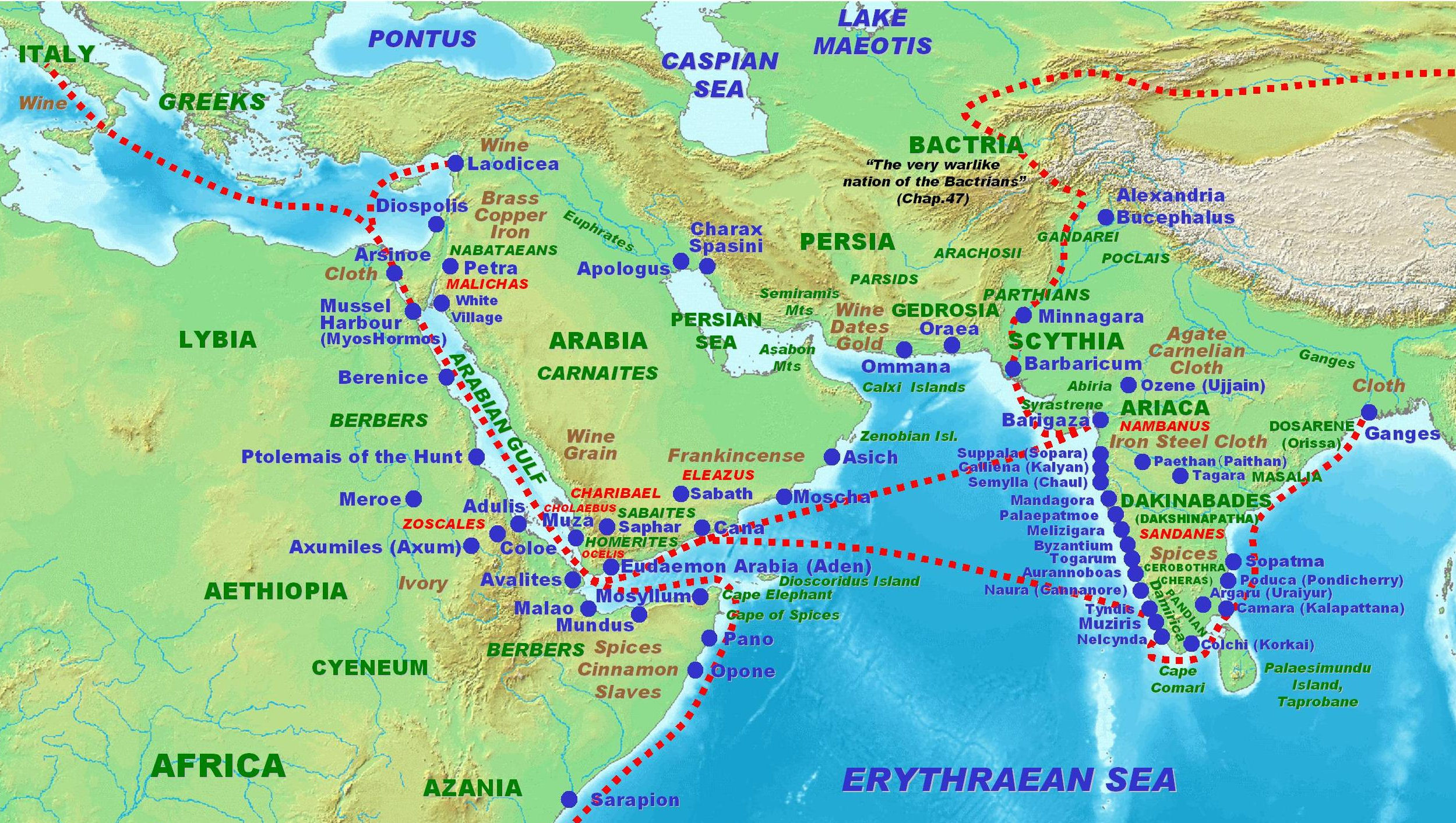

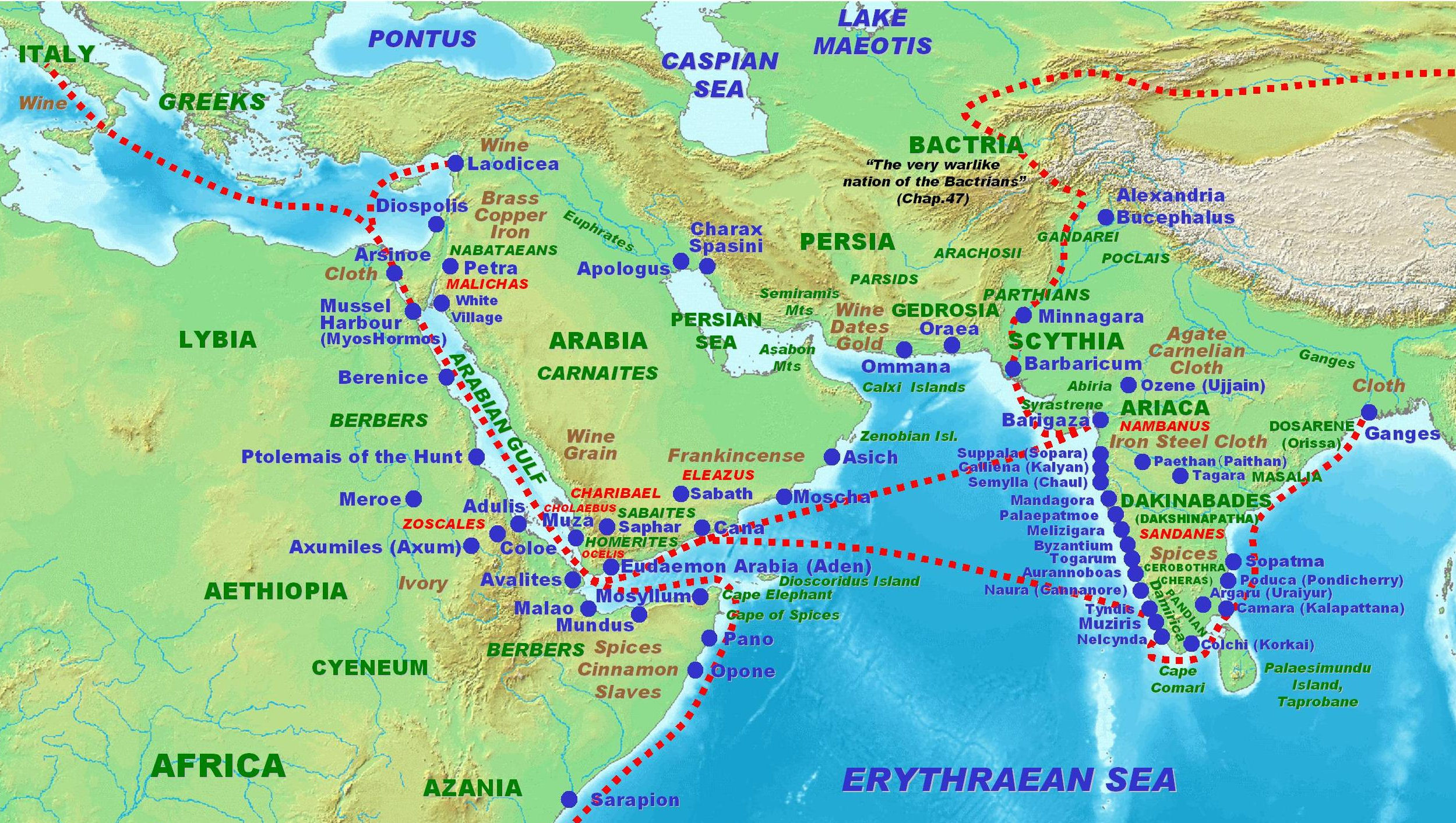

and Iberia, both areas rich in minerals. At the height of the Empire, Rome exploited mineral resources from Tingitana in north western Africa to Egypt, Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

to North Armenia, Galatia

Galatia (; , ''Galatía'') was an ancient area in the highlands of central Anatolia, roughly corresponding to the provinces of Ankara and Eskişehir in modern Turkey. Galatia was named after the Gauls from Thrace (cf. Tylis), who settled here ...

to Germania

Germania ( ; ), also more specifically called Magna Germania (English: ''Great Germania''), Germania Libera (English: ''Free Germania''), or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman provinces of Germania Inferior and Germania Superio ...

, and Britannia to Iberia, encompassing all of the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

coast. Britannia, Iberia, Dacia, and Noricum were of special significance, as they were very rich in deposits and became major sites of resource exploitation (Shepard, 1993).

There is evidence that after the middle years of the Empire there was a sudden and steep decline in

mineral extraction

Mining is the Resource extraction, extraction of valuable geological materials and minerals from the surface of the Earth. Mining is required to obtain most materials that cannot be grown through agriculture, agricultural processes, or feasib ...

. This was mirrored in other trades and industries.

One of the most important Roman sources of information is the ''Naturalis Historia

The ''Natural History'' () is a Latin work by Pliny the Elder. The largest single work to have survived from the Roman Empire to the modern day, the ''Natural History'' compiles information gleaned from other ancient authors. Despite the work' ...

'' of Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

. Several books (XXXIII–XXXVII) of his encyclopedia

An encyclopedia is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge, either general or special, in a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into article (publishing), articles or entries that are arranged Alp ...

cover metals and metal ores, their occurrence, importance and development.

Types of metal used

Many of the first metal artifacts that archaeologists have identified have beentools

A tool is an object that can extend an individual's ability to modify features of the surrounding environment or help them accomplish a particular task. Although many animals use simple tools, only human beings, whose use of stone tools dates ...

or weapons

A weapon, arm, or armament is any implement or device that is used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime (e.g., murder), law ...

, as well as objects used as ornaments such as jewellery

Jewellery (or jewelry in American English) consists of decorative items worn for personal adornment such as brooches, ring (jewellery), rings, necklaces, earrings, pendants, bracelets, and cufflinks. Jewellery may be attached to the body or the ...

. These early metal objects were made of the softer metals; copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

, gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

, and lead

Lead () is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Pb (from Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a Heavy metal (elements), heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale, soft and Ductility, malleabl ...

in particular, either as native metal

A native metal is any metal that is found pure in its metallic form in nature. Metals that can be found as native element mineral, native deposits singly or in alloys include antimony, arsenic, bismuth, cadmium, chromium, cobalt, indium, iron, ma ...

s or by thermal extraction from minerals, and softened by minimal heat (Craddock, 1995). While technology did advance to the point of creating surprisingly pure copper, most ancient metals are in fact alloys

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements of which in most cases at least one is a metallic element, although it is also sometimes used for mixtures of elements; herein only metallic alloys are described. Metallic alloys often have properties ...

, the most important being bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals (such as phosphorus) or metalloid ...

, an alloy of copper and tin

Tin is a chemical element; it has symbol Sn () and atomic number 50. A silvery-colored metal, tin is soft enough to be cut with little force, and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, a bar of tin makes a sound, the ...

. As metallurgical technology developed ( hammering, melting

Melting, or fusion, is a physical process that results in the phase transition of a substance from a solid to a liquid. This occurs when the internal energy of the solid increases, typically by the application of heat or pressure, which inc ...

, smelting

Smelting is a process of applying heat and a chemical reducing agent to an ore to extract a desired base metal product. It is a form of extractive metallurgy that is used to obtain many metals such as iron-making, iron, copper extraction, copper ...

, roasting

Roasting is a cooking method that uses dry heat where hot air covers the food, cooking it evenly on all sides with temperatures of at least from an open flame, oven, or other heat source. Roasting can enhance the flavor through caramelizat ...

, cupellation

Cupellation is a refining process in metallurgy in which ores or alloyed metals are treated under very high temperatures and subjected to controlled operations to separate noble metals, like gold and silver, from base metals, like lead, co ...

, moulding, smithing

A metalsmith or simply smith is a craftsperson fashioning useful items (for example, tools, kitchenware, tableware, jewelry, armor and weapons) out of various metals. Smithing is one of the oldest metalworking occupations. Shaping metal with a ...

, etc.), more metals were intentionally included in the metallurgical repertoire.

By the height of the Roman Empire, metals in use included: silver

Silver is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag () and atomic number 47. A soft, whitish-gray, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and reflectivity of any metal. ...

, zinc

Zinc is a chemical element; it has symbol Zn and atomic number 30. It is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodic tabl ...

, iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

, mercury, arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol As and atomic number 33. It is a metalloid and one of the pnictogens, and therefore shares many properties with its group 15 neighbors phosphorus and antimony. Arsenic is not ...

, antimony

Antimony is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Sb () and atomic number 51. A lustrous grey metal or metalloid, it is found in nature mainly as the sulfide mineral stibnite (). Antimony compounds have been known since ancient t ...

, lead, gold, copper, tin (Healy 1978). As in the Bronze Age, metals were used based on many physical properties: aesthetics, hardness

In materials science, hardness (antonym: softness) is a measure of the resistance to plastic deformation, such as an indentation (over an area) or a scratch (linear), induced mechanically either by Pressing (metalworking), pressing or abrasion ...

, colour, taste/smell (for cooking wares), timbre (instruments), resistance to corrosion

Corrosion is a natural process that converts a refined metal into a more chemically stable oxide. It is the gradual deterioration of materials (usually a metal) by chemical or electrochemical reaction with their environment. Corrosion engine ...

, weight (i.e., density), and other factors. Many alloys were also possible, and were intentionally made in order to change the properties of the metal; e.g. the alloy of predominately tin with lead would harden the soft tin, to create pewter

Pewter () is a malleable metal alloy consisting of tin (85–99%), antimony (approximately 5–10%), copper (2%), bismuth, and sometimes silver. In the past, it was an alloy of tin and lead, but most modern pewter, in order to prevent lead poi ...

, which would prove its utility as cooking and tableware

Tableware items are the dishware and utensils used for setting a table, serving food, and dining. The term includes cutlery, glassware, serving dishes, serving utensils, and other items used for practical as well as decorative purposes. The ...

.

Sources of ore

Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, compri ...

(modern Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

and Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

) was possibly the Roman province

The Roman provinces (, pl. ) were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was ruled by a Roman appointed as Roman g ...

richest in mineral ore

Ore is natural rock or sediment that contains one or more valuable minerals, typically including metals, concentrated above background levels, and that is economically viable to mine and process. The grade of ore refers to the concentration ...

, containing deposits of gold, silver, copper, tin, lead, iron, and mercury. From its acquisition after the Second Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of Punic Wars, three wars fought between Ancient Carthage, Carthage and Roman Republic, Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean Basin, Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For ...

to the Fall of Rome, Iberia continued to produce a significant amount of Roman metals.

Britannia was also very rich in metals. Gold was mined at Dolaucothi

The Dolaucothi Gold Mines (; ) (), also known as the Ogofau Gold Mine, are ancient Roman surface and underground mines located in the valley of the River Cothi, near Pumsaint, Carmarthenshire, Wales. The gold mines are located within the ...

in Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

, copper and tin in Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

, and lead in the Pennines

The Pennines (), also known as the Pennine Chain or Pennine Hills, are a range of highland, uplands mainly located in Northern England. Commonly described as the "Vertebral column, backbone of England" because of its length and position, the ra ...

, Mendip Hills

The Mendip Hills (commonly called the Mendips) is a range of limestone hills to the south of Bristol and Bath, Somerset, Bath in Somerset, England. Running from Weston-super-Mare and the Bristol Channel in the west to the River Frome, Somerset ...

and Wales. Significant studies have been made on the iron production of Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the territory that became the Roman province of ''Britannia'' after the Roman conquest of Britain, consisting of a large part of the island of Great Britain. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410.

Julius Caes ...

; iron use in Europe was intensified by the Romans, and was part of the exchange of ideas between the cultures through Roman occupation. It was the importance placed on iron by the Romans throughout the Empire which completed the shift from the few cultures still using primarily bronze into the Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

.

Noricum (modern Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

) was exceedingly rich in gold and iron, Pliny, Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-si ...

, and Ovid

Publius Ovidius Naso (; 20 March 43 BC – AD 17/18), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a younger contemporary of Virgil and Horace, with whom he i ...

all lauded its bountiful deposits. Iron was its main commodity, but alluvial

Alluvium (, ) is loose clay, silt, sand, or gravel that has been deposited by running water in a stream bed, on a floodplain, in an alluvial fan or beach, or in similar settings. Alluvium is also sometimes called alluvial deposit. Alluvium is ...

gold was also prospected. By 15 BC, Noricum was officially made a province

A province is an administrative division within a country or sovereign state, state. The term derives from the ancient Roman , which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire, Roman Empire's territorial possessions ou ...

of the Empire, and the metal trade saw prosperity well into the fifth century AD. Some scholars believe that the art of iron forging

Forging is a manufacturing process involving the shaping of metal using localized compression (physics), compressive forces. The blows are delivered with a hammer (often a power hammer) or a die (manufacturing), die. Forging is often classif ...

was not necessarily created, but well developed in this area and it was the population of Noricum which reminded Romans of the usefulness of iron. For example, of the three forms of iron (wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4.5%), or 0.25 for low carbon "mild" steel. Wrought iron is manufactured by heating and melting high carbon cast iron in an ...

, steel

Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon that demonstrates improved mechanical properties compared to the pure form of iron. Due to steel's high Young's modulus, elastic modulus, Yield (engineering), yield strength, Fracture, fracture strength a ...

, and soft), the forms which were exported were of the wrought iron (containing a small percentage of uniformly distributed slag

The general term slag may be a by-product or co-product of smelting (pyrometallurgical) ores and recycled metals depending on the type of material being produced. Slag is mainly a mixture of metal oxides and silicon dioxide. Broadly, it can be c ...

material) and steel (carbonised iron) categories, as pure iron is too soft to function like wrought or steel iron.

Dacia, located in the area of Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

, was conquered in 107 AD in order to capture the resources of the region for Rome. The amount of gold that came into Roman possession actually brought down the value of gold. Iron was also of importance to the region. The difference between the mines of Noricum and Dacia was the presence of a slave

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

population as a workforce.

Technology

The earliest metal manipulation was probably hammering (Craddock 1995, 1999), where copper ore was pounded into thin sheets. The ore (if there were large enough pieces of metal separate from mineral) could be beneficiated ('made better') before or after melting, where the prills of metal could be hand-picked from the cooled slag.

The earliest metal manipulation was probably hammering (Craddock 1995, 1999), where copper ore was pounded into thin sheets. The ore (if there were large enough pieces of metal separate from mineral) could be beneficiated ('made better') before or after melting, where the prills of metal could be hand-picked from the cooled slag. Melting

Melting, or fusion, is a physical process that results in the phase transition of a substance from a solid to a liquid. This occurs when the internal energy of the solid increases, typically by the application of heat or pressure, which inc ...

beneficiated metal also allowed early metallurgists to use moulds and casts to form shapes of molten metal

Melting, or Enthalpy of fusion, fusion, is a physical process that results in the phase transition of a chemical substance, substance from a solid to a liquid. This occurs when the internal energy of the solid increases, typically by the appli ...

(Craddock 1995). Many of the metallurgical skills developed in the Bronze Age were still in use during Roman times. Melting—the process of using heat to separate slag and metal, smelting—using a reduced oxygen heated environment to separate metal oxides into metal and carbon dioxide, roasting—process of using an oxygen rich environment to isolate sulphur oxide from metal oxide which can then be smelted, casting

Casting is a manufacturing process in which a liquid material is usually poured into a mold, which contains a hollow cavity of the desired shape, and then allowed to solidify. The solidified part is also known as a casting, which is ejected or ...

—pouring liquid metal into a mould to make an object, hammering—using blunt force to make a thin sheet which can be annealed or shaped, and cupellation—separating metal alloys to isolate a specific metal—were all techniques which were well understood (Zwicker 1985, Tylecote 1962, Craddock 1995). However, the Romans provided few new technological advances other than the use of iron and the cupellation and granulation

Granulation is the process of forming grains or granules from a powdery or solid substance, producing a granular material. It is applied in several technological processes in the chemical and pharmaceutical industries. Typically, granulation inv ...

in the separation of gold alloys (Tylecote 1962).

While native gold is common, the ore will sometimes contain small amounts of silver and copper. The Romans utilised a sophisticated system to separate these precious metals. The use of cupellation, a process developed before the rise of Rome, would extract copper from gold and silver, or an alloy called electrum

Electrum is a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver, with trace amounts of copper and other metals. Its color ranges from pale to bright yellow, depending on the proportions of gold and silver. It has been produced artificially and is ...

. In order to separate the gold and silver, however, the Romans would granulate the alloy by pouring the liquid, molten metal into cold water, and then smelt the granules with salt

In common usage, salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl). When used in food, especially in granulated form, it is more formally called table salt. In the form of a natural crystalline mineral, salt is also known as r ...

, separating the gold from the chemically altered silver chloride

Silver chloride is an inorganic chemical compound with the chemical formula Ag Cl. This white crystalline solid is well known for its low solubility in water and its sensitivity to light. Upon illumination or heating, silver chloride converts ...

(Tylecote 1962). They used a similar method to extract silver from lead.

While Roman production became standardised in many ways, the evidence for distinct unity of furnace types is not strong, alluding to a tendency of the peripheries continuing with their own past furnace technologies. In order to complete some of the more complex metallurgical techniques, there is a bare minimum of necessary components for Roman metallurgy: metallic ore, furnace of unspecified type with a form of oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

source (assumed by Tylecote to be bellows) and a method of restricting said oxygen (a lid or cover), a source of fuel

A fuel is any material that can be made to react with other substances so that it releases energy as thermal energy or to be used for work (physics), work. The concept was originally applied solely to those materials capable of releasing chem ...

(charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, ca ...

from wood

Wood is a structural tissue/material found as xylem in the stems and roots of trees and other woody plants. It is an organic materiala natural composite of cellulosic fibers that are strong in tension and embedded in a matrix of lignin t ...

or occasionally peat

Peat is an accumulation of partially Decomposition, decayed vegetation or organic matter. It is unique to natural areas called peatlands, bogs, mires, Moorland, moors, or muskegs. ''Sphagnum'' moss, also called peat moss, is one of the most ...

), moulds and/or hammers

A hammer is a tool, most often a hand tool, consisting of a weighted "head" fixed to a long handle that is swung to deliver an impact to a small area of an object. This can be, for example, to drive nail (fastener), nails into wood, to sh ...

and anvils for shaping, the use of crucibles for isolating metals (Zwicker 1985), and likewise cupellation hearths (Tylecote 1962).

Mechanisation

There is direct evidence that the Romans mechanised at least part of the extraction processes. They used water power fromwater wheels

A water wheel is a machine for converting the kinetic energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a large wheel (usually constructed from wood or metal), with numerous blade ...

for grinding grains and sawing timber or stone, for example. A set of sixteen such overshot wheels is still visible at Barbegal near Arles

Arles ( , , ; ; Classical ) is a coastal city and Communes of France, commune in the South of France, a Subprefectures in France, subprefecture in the Bouches-du-Rhône Departments of France, department of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Reg ...

and dates from the 1st century AD or possibly earlier, the water being supplied by the main aqueduct to Arles. It is likely that the mills supplied flour for Arles and other towns locally. Multiple grain mills also existed on the Janiculum

The Janiculum (; ), occasionally known as the Janiculan Hill, is a hill in western Rome, Italy. Although it is the second-tallest hill (the tallest being Monte Mario) in the contemporary city of Rome, the Janiculum does not figure among the pro ...

hill in Rome.

Ausonius

Decimius Magnus Ausonius (; ) was a Latin literature, Roman poet and Education in ancient Rome, teacher of classical rhetoric, rhetoric from Burdigala, Gallia Aquitania, Aquitaine (now Bordeaux, France). For a time, he was tutor to the future E ...

attests the use of a water mill for sawing stone in his poem '' Mosella'' from the 4th century AD. They could easily have adapted the technology to crush ore using tilt hammers, and just such is mentioned by Pliny the Elder in his ''Naturalis Historia'' dating to about 75 AD, and there is evidence for the method from Dolaucothi in South Wales

South Wales ( ) is a Regions of Wales, loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the Historic counties of Wales, historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire ( ...

. The Roman gold mines developed from c. 75 AD. The methods survived into the medieval period, as described and illustrated by Georgius Agricola

Georgius Agricola (; born Georg Bauer; 24 March 1494 – 21 November 1555) was a German Humanist scholar, mineralogist and metallurgist. Born in the small town of Glauchau, in the Electorate of Saxony of the Holy Roman Empire, he was b ...

in his '' De re metallica''.

They also used reverse overshot water-wheel

Frequently used in mines and probably elsewhere (such as agricultural drainage), the reverse overshot water wheel was a Roman innovation to help remove water from the lowest levels of underground workings. It is described by Vitruvius in his work ' ...

s for draining mines, the parts being prefabricated and numbered for ease of assembly. Multiple set of such wheels have been found in Spain at the Rio Tinto copper mines and a fragment of a wheel at Dolaucothi. An incomplete wheel from Spain is now on public show in the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

.

Output

The invention and widespread application ofhydraulic mining

Hydraulic mining is a form of mining that uses high-pressure jets of water to dislodge rock material or move sediment.Paul W. Thrush, ''A Dictionary of Mining, Mineral, and Related Terms'', US Bureau of Mines, 1968, p.560. In the placer mining of ...

, namely hushing

Hushing is an ancient and historic mining method using a flood or torrent of water to reveal mineral veins. The method was applied in several ways, both in prospecting for ores, and for their exploitation. Mineral veins are often hidden bel ...

and ground-sluicing, aided by the ability of the Romans to plan and execute mining operations on a large scale, allowed various base and precious metals to be extracted on a proto-industrial scale only rarely matched until the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

.

The most common fuel by far for smelting and forging operations, as well as heating purposes, was wood and particularly charcoal, which is nearly twice as efficient. In addition, coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other Chemical element, elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal i ...

was mined in some regions to a fairly large extent: almost all major coalfields in Roman Britain were exploited by the late 2nd century AD, and a lively trade along the English North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

coast developed, which extended to the continental Rhineland

The Rhineland ( ; ; ; ) is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly Middle Rhine, its middle section. It is the main industrial heartland of Germany because of its many factories, and it has historic ties to the Holy ...

, where bituminous coal

Bituminous coal, or black coal, is a type of coal containing a tar-like substance called bitumen or asphalt. Its coloration can be black or sometimes dark brown; often there are well-defined bands of bright and dull material within the coal seam, ...

was already used for the smelting of iron ore. The annual iron production at Populonia

Populonia or Populonia Alta ( Etruscan: ''Pupluna'', ''Pufluna'' or ''Fufluna'', all pronounced ''Fufluna''; Latin: ''Populonium'', ''Populonia'', or ''Populonii'') today is a of the ''comune'' of Piombino (Tuscany, central Italy). As of 2009 its ...

alone accounted for an estimated 2,000 to 10,000 tons. Wertime, Theodore A. (1983): "The Furnace versus the Goat: The Pyrotechnologic Industries and Mediterranean Deforestation in Antiquity", ''Journal of Field Archaeology'', Vol. 10, No. 4, pp. 445–452 (451); Williams, Joey (2009): "The Environmental Effects of Populonia's Metallurgical Industry: Current Evidence and Future Directions", ''Etruscan and Italic Studies'', Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 131–150 (134f.)

Production of objects

Romans used many methods to create metal objects. Like

Romans used many methods to create metal objects. Like Samian ware

Terra sigillata is a term with at least three distinct meanings: as a description of medieval medicinal earth; in archaeology, as a general term for some of the fine red ancient Roman pottery with glossy surface slips made in specific areas ...

, moulds were created by making a model of the desired shape (whether through wood, wax, or metal), which would then be pressed into a clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolinite, ). Most pure clay minerals are white or light-coloured, but natural clays show a variety of colours from impuriti ...

mould. In the case of a metal or wax model, once dry, the ceramic

A ceramic is any of the various hard, brittle, heat-resistant, and corrosion-resistant materials made by shaping and then firing an inorganic, nonmetallic material, such as clay, at a high temperature. Common examples are earthenware, porcela ...

could be heated and the wax or metal melted until it could be poured from the mould (this process utilising wax is called the “lost wax

Lost-wax castingalso called investment casting, precision casting, or ''cire perdue'' (; loanword, borrowed from French language, French)is the process by which a duplicate sculpture (often a metal, such as silver, gold, brass, or bronze) is cas ...

“ technique). By pouring metal into the aperture, exact copies of an object could be cast. This process made the creation of a line of objects quite uniform. This is not to suggest that the creativity of individual artisans did not continue; rather, unique handcrafted pieces were normally the work of small, rural metalworkers on the peripheries of Rome using local techniques (Tylecote 1962).

There is archaeological evidence throughout the Empire demonstrating the large scale excavations

In archaeology, excavation is the exposure, processing and recording of archaeological remains. An excavation site or "dig" is the area being studied. These locations range from one to several areas at a time during a project and can be condu ...

, smelting, and trade routes concerning metals. With the Romans came the concept of mass production

Mass production, also known as mass production, series production, series manufacture, or continuous production, is the production of substantial amounts of standardized products in a constant flow, including and especially on assembly lines ...

; this is arguably the most important aspect of Roman influence in the study of metallurgy. Three particular objects produced en masse and seen in the archaeological record

The archaeological record is the body of physical (not written) evidence about the past. It is one of the core concepts in archaeology, the academic discipline concerned with documenting and interpreting the archaeological record. Archaeological t ...

throughout the Roman Empire are brooches called fibulae, worn by both men and women (Bayley 2004), coins

A coin is a small object, usually round and flat, used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in order to facilitate trade. They are most often issued by ...

, and ingots

An ingot is a piece of relatively pure material, usually metal, that is cast into a shape suitable for further processing. In steelmaking, it is the first step among semi-finished casting products. Ingots usually require a second procedure of sh ...

(Hughes 1980). These cast objects can allow archaeologists

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

to trace years of communication

Communication is commonly defined as the transmission of information. Its precise definition is disputed and there are disagreements about whether Intention, unintentional or failed transmissions are included and whether communication not onl ...

, trade, and even historic/stylistic changes throughout the centuries of Roman power.

Social ramifications

Slavery

When the cost of producing slaves became too high to justify slavelabourers

A laborer ( or labourer) is a person who works in manual labor typed within the construction industry. There is a generic factory laborer which is defined separately as a factory worker. Laborers are in a working class of wage-earners in which ...

for the many mines throughout the empire

An empire is a political unit made up of several territories, military outpost (military), outposts, and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a hegemony, dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the ...

around the second century, a system of indentured servitude

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract called an " indenture", may be entered voluntarily for a prepaid lump sum, as payment for some good or s ...

was introduced for convicts

A convict is "a person found Guilt (law), guilty of a crime and Sentence (law), sentenced by a court" or "a person serving a sentence in prison". Convicts are often also known as "prisoners" or "inmates" or by the slang term "con", while a commo ...

. In 369 AD, a law was reinstated due to the closure of many deep mines; the emperor Hadrian

Hadrian ( ; ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. Hadrian was born in Italica, close to modern Seville in Spain, an Italic peoples, Italic settlement in Hispania Baetica; his branch of the Aelia gens, Aelia '' ...

had previously given the control of mines to private employers, so that workers were hired rather than working out of force. Through the institution of this system profits increased (Shepard 1993). In the case of Noricum, there is archaeological evidence of freemen labour in the metal trade and extraction through graffiti

Graffiti (singular ''graffiti'', or ''graffito'' only in graffiti archeology) is writing or drawings made on a wall or other surface, usually without permission and within public view. Graffiti ranges from simple written "monikers" to elabor ...

on mine walls. In this province, many men were given Roman citizenship

Citizenship in ancient Rome () was a privileged political and legal status afforded to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Citizenship in ancient Rome was complex and based upon many different laws, traditions, and cu ...

for their efforts contributing to the procurement of metal for the empire. Both privately owned and government run mines were in operation simultaneously (Shepard 1993).

Economy

From the formation of the Roman Empire, Rome was an almost completely closed

From the formation of the Roman Empire, Rome was an almost completely closed economy

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

, not reliant on imports

An importer is the receiving country in an export from the sending country. Importation and exportation are the defining financial transactions of international trade. Import is part of the International Trade which involves buying and receivin ...

although exotic goods from India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

(such as gems, silk

Silk is a natural fiber, natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be weaving, woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is most commonly produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoon (silk), c ...

and spices

In the culinary arts, a spice is any seed, fruit, root, Bark (botany), bark, or other plant substance in a form primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of pl ...

) were highly prized (Shepard 1993). Through the recovery of Roman coins

Roman currency for most of Roman history consisted of gold, silver, bronze, orichalcum#Numismatics, orichalcum and copper coinage. From its introduction during the Roman Republic, Republic, in the third century BC, through Roman Empire, Imperial ...

and ingots throughout the ancient world

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history through late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the development of Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient h ...

(Hughes 1980), metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the ...

has supplied the archaeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

with material culture

Material culture is culture manifested by the Artifact (archaeology), physical objects and architecture of a society. The term is primarily used in archaeology and anthropology, but is also of interest to sociology, geography and history. The fie ...

through which to see the expanse of the Roman world.

See also

*Georgius Agricola

Georgius Agricola (; born Georg Bauer; 24 March 1494 – 21 November 1555) was a German Humanist scholar, mineralogist and metallurgist. Born in the small town of Glauchau, in the Electorate of Saxony of the Holy Roman Empire, he was b ...

* Mining in Roman Britain

* Mining in ancient Rome

* Roman engineering

The ancient Romans were famous for their advanced engineering accomplishments. Technology for bringing running water into cities was developed in the east, but transformed by the Romans into a technology inconceivable in Greece. The architecture ...

* Roman technology

Ancient Roman technology is the collection of techniques, skills, methods, processes, and engineering practices which supported Roman civilization and made possible the expansion of the Roman economy, economy and Military of ancient Rome, milit ...

* Malvesa

References

Sources

; General * Aitchison, Leslie. 1960. A History of Metals. London: Macdonald & Evans Ltd. * Bayley, Justine; Butcher, Sarnia. 2004. Roman Brooches in Britain: A Technological and Typological Study based on the Richborough Collection. London: The Society of Antiquaries of London. * Craddock, Paul T. 1995. Early Metal Mining and Production. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. * Craddock, Paul T. 1999. Paradigms of Metallurgical Innovation in Prehistoric Europe in Hauptmann, A., Ernst, P., Rehren, T., Yalcin, U. (eds). The Beginnings of Metallurgy: Proceedings of the International Conference “The Beginnings of Metallurgy”, Bochum 1995. Hamburg * Davies, O. Roman Mines in Europe 1935., Oxford University Press * Hughes, M. J. 1980 The Analysis of Roman Tin and Pewter Ingots in Ody, W. A. (ed) Aspects of Early Metallurgy. Occasional Paper No 17. British Museum Occasional Papers. * Shepard, Robert. 1993. Ancient Mining. London: Elsevier Applied Science. * Sim, David. 1998. Beyond the Bloom: Bloom Refining and Iron Artifact Production in the Roman World. Ridge, Isabel (ed). BAR International Series 725. Oxford: Archaeopress. * Tylecote, R.F. 1962. Metallurgy in Archaeology: A Prehistory of Metallurgy in the British Isles. London: Edward Arnold (Publishers) Ltd. * Zwicker, U., Greiner, H., Hofmann, K-H., Reithinger, M. 1985. Smelting, Refining and Alloying of Copper and Copper Alloys in Crucible Furnaces During Prehistoric up to Roman Times in Craddock, P.T., Hughes, M.J. (eds) Furnaces and Smelting Technology in Antiquity. Occasional Paper No 48. London: British Museum Occasional Papers. * J. S., Hodgkinson. 2008. "The Wealden Iron Industry." (The History Press, Stroud). * Cleere, Henry. 1981. The Iron Industry of Roman Britain. Wealden Iron Research Group. ; Output * Callataÿ, François de (2005): "The Graeco-Roman Economy in the Super Long-Run: Lead, Copper, and Shipwrecks", ''Journal of Roman Archaeology'', Vol. 18, pp. 361–372 * Cech, Brigitte (2010): ''Technik in der Antike'', Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt, * Cleere, H. & Crossley, D. (1995): The Iron industry of the Weald. 2nd edition, Merton Priory Press, Cardiff, : republishing the 1st edition (Leicester University Press 1985) with a supplement. * Cleere, Henry. 1981. The Iron Industry of Roman Britain. Wealden Iron Research Group. p. 74-75 * Craddock, Paul T. (2008): "Mining and Metallurgy", in: Oleson, John Peter (ed.): ''The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World'', Oxford University Press, , pp. 93–120 * Healy, John F. (1978): ''Mining and Metallurgy in the Greek and Roman World'', Thames and Hudson, London, * Hong, Sungmin; Candelone, Jean-Pierre; Patterson, Clair C.; Boutron, Claude F. (1994): "Greenland Ice Evidence of Hemispheric Lead Pollution Two Millennia Ago by Greek and Roman Civilizations", ''Science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

'', Vol. 265, No. 5180, pp. 1841–1843

* Hong, Sungmin; Candelone, Jean-Pierre; Patterson, Clair C.; Boutron, Claude F. (1996): "History of Ancient Copper Smelting Pollution During Roman and Medieval Times Recorded in Greenland Ice", ''Science'', Vol. 272, No. 5259, pp. 246–249

* Patterson, Clair C. (1972): "Silver Stocks and Losses in Ancient and Medieval Times", ''The Economic History Review

''The Economic History Review'' is a peer-reviewed history journal published quarterly by Wiley-Blackwell on behalf of the Economic History Society. It was established in 1927 by Eileen Power and is currently edited by Sara Horrell, Jaime Reis a ...

'', Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 205–235

* Lewis, P. R. and G. D. B. Jones, ''The Dolaucothi gold mines, I: the surface evidence'', The Antiquaries Journal, 49, no. 2 (1969): 244-72.

* Lewis, P. R. and G. D. B. Jones, ''Roman gold-mining in north-west Spain'', Journal of Roman Studies 60 (1970): 169-85.

* Lewis, P. R., ''The Ogofau Roman gold mines at Dolaucothi'', The National Trust Year Book 1976-77 (1977).

* Settle, Dorothy M.; Patterson, Clair C. (1980): "Lead in Albacore: Guide to Lead Pollution in Americans", ''Science'', Vol. 207, No. 4436, pp. 1167–1176

* Sim, David; Ridge, Isabel (2002): ''Iron for the Eagles. The Iron Industry of Roman Britain'', Tempus, Stroud, Gloucestershire,

* Smith, A. H. V. (1997): "Provenance of Coals from Roman Sites in England and Wales", ''Britannia

The image of Britannia () is the national personification of United Kingdom, Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used by the Romans in classical antiquity, the Latin was the name variously appli ...

'', Vol. 28, pp. 297–324

* Wilson, Andrew (2002): "Machines, Power and the Ancient Economy", ''The Journal of Roman Studies

The Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies (The Roman Society) was founded in 1910 as the sister society to the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies.

The Society is the leading organisation in the United Kingdom for those intereste ...

'', Vol. 92, pp. 1–32

Further reading

*Butcher, Kevin, Matthew Ponting, Jane Evans, Vanessa Pashley, and Christopher Somerfield. ''The Metallurgy of Roman Silver Coinage: From the Reform of Nero to the Reform of Trajan''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. *Corretti,Benvenuti. "Beginning of iron metallurgy in Tuscany, with special reference to ''Etruria mineraria''." ''Mediterranean archaeology'' 14 (2001): 127–45. *Healy, John F. ''Mining and metallurgy in the Greek and Roman world''. London: Thames and Hudson, 1978. *Hobbs, Richard. ''Late Roman Precious Metal Deposits, C. AD 200-700: Changes Over Time and Space''. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2006. *Montagu, Jennifer. ''Gold, Silver, and Bronze: Metal Sculpture of the Roman Baroque''. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996. *Papi, Emanuele., and Michel Bonifay. ''Supplying Rome and the Empire: The Proceedings of an International Seminar Held At Siena-Certosa Di Pontignano On May 2-4, 2004, On Rome, the Provinces, Production and Distribution''. Portsmouth, RI: Journal of Roman Archaeology, 2007. *Rihll, T. E. ''Technology and Society In the Ancient Greek and Roman Worlds''. Washington, D.C.: American Historical Association, Society for the History of Technology, 2013. *Schrüfer-Kolb, Irene. ''Roman Iron Production In Britain: Technological and Socio-Economic Landscape Development Along the Jurassic Ridge''. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2004. * *Young, Suzanne M. M. ''Metals In Antiquity''. Oxford, England: Archaeopress, 1999. {{DEFAULTSORT:Roman Metallurgy History of metallurgyMetallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the ...

*