Roman Elections on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In the

In the

Elections customarily took place around the same time each year in the centuriate and tribal assemblies under similar procedures. After

Elections customarily took place around the same time each year in the centuriate and tribal assemblies under similar procedures. After

The campaign itself was called the . The main source on Roman campaigning is the '' Commentariolum Petitionis'' which is attributed to

The campaign itself was called the . The main source on Roman campaigning is the '' Commentariolum Petitionis'' which is attributed to

The Social War, fought between the Romans and their Italian allies, saw the Italian allies mostly put down their arms when the republic, through the '' lex Julia de civitate'' and ''

The Social War, fought between the Romans and their Italian allies, saw the Italian allies mostly put down their arms when the republic, through the '' lex Julia de civitate'' and ''

In the

In the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

, elections were held annually for every major magistracy. They were conducted before two assemblies (): the centuriate and tribal assemblies. The centuriate assembly, made up of centuries divided by wealth and age, elected the senior magistrates: those with (the consuls

A consul is an official representative of a government who resides in a foreign country to assist and protect citizens of the consul's country, and to promote and facilitate commercial and diplomatic relations between the two countries.

A consu ...

and the praetors

''Praetor'' ( , ), also ''pretor'', was the title granted by the government of ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected ''magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to discha ...

) and the censors. The tribal assembly, made up of tribe

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide use of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. The definition is contested, in part due to conflict ...

s grouped by geography, elected all other magistrates. Plebeian tribunes and aediles were also elected by the tribal assembly although in a slightly different form.

The formal electoral process started with an announcement by the prospective presiding magistrate of an election day, typically in July. Candidates then professed their candidacy to that magistrate. On the day of the election, the voting unit – centuries or tribes – would be called to give their votes. Citizens voted in person for their candidate and the unit registered one vote for each open post (eg, for the two consuls, a century would vote for two candidates). Once a candidate received a majority, 97 centuries or 18 tribes, he won and was removed from the contest. Once all posts were filled, elections ended and all centuries or tribes that had not voted were dismissed. If nightfall came before elections were complete, the entire process had to restart, typically on the next legislative day.

There were no political parties in the republic. Candidates campaigned largely on their own personal virtue, personal or family reputation, or gifts distributed to voters. Reflecting the unpredictability of elections, bribes given to voters in the form of money, food, and games were a common and burdensome campaign expense. Regardless, those with a family reputation in politics (ie the ''nobiles

The ''nobiles'' ( ''nobilis'', ) were members of a social rank in the Roman Republic indicating that one was "well known". This may have changed over time: in Cicero's time, one was notable if one descended from a person who had been elected con ...

'') – and a family name that could be recognised by the voters – regularly dominated electoral results.

Roman elections, while extremely important for political life because no legislation could be passed without the initiative

Popular initiative

A popular initiative (also citizens' initiative) is a form of direct democracy by which a petition meeting certain hurdles can force a legal procedure on a proposition.

In direct initiative, the proposition is put direct ...

of a magistrate, were not representative of the citizenry. The malapportionment

Apportionment is the process by which seats in a legislative body are distributed among administrative divisions, such as states or parties, entitled to representation. This page presents the general principles and issues related to apportionmen ...

of the weighted the 193 centuries, each of which received one vote, strongly towards the old and rich. The gave each of the 35 tribes the same vote even if the number of voters within them was wildly different. Moreover, because all public affairs were conducted in person, poorer people from the countryside unable to take the time off to travel to Rome were unable to exercise their rights. And even though all freed slaves

A freedman or freedwoman is a person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, slaves were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their owners), emancipation (granted freedom as part of a larger group), or self- ...

became citizens on manumission, they were confined to the four "urban" tribes regardless of actual residence, limiting their voice in politics. Scholars have estimated that, in the late republic, turnout could not have been more than about 10 per cent.

After the fall of the republic and the establishment of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, elections – thoroughly dominated by the emperor's influence – initially continued. However, during the reign of Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus ( ; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was Roman emperor from AD 14 until 37. He succeeded his stepfather Augustus, the first Roman emperor. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC to Roman politician Tiberius Cl ...

, the power of nomination was transferred to the senate. Then on, with a short interlude under Caligula

Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August 12 – 24 January 41), also called Gaius and Caligula (), was Roman emperor from AD 37 until his assassination in 41. He was the son of the Roman general Germanicus and Augustus' granddaughter Ag ...

, all magistrates were nominated in a list that was then inevitably confirmed by an assembly. After some time, this too was abolished. Elections at the municipal level, conducted under bylaws which were generally modelled on the republican constitution, however, continued well into the first and second centuries AD.

Procedure

Elections customarily took place around the same time each year in the centuriate and tribal assemblies under similar procedures. After

Elections customarily took place around the same time each year in the centuriate and tribal assemblies under similar procedures. After Sulla's constitutional reforms

The constitutional reforms of Sulla were a series of laws enacted by the Roman dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla between 82 and 80 BC, reforming the constitution of the Roman Republic in a revolutionary way.

In the decades before Sulla had bec ...

, this was normally in July (then called Quintilis

In the ancient Roman calendar, Quintilis or Quinctilis was the month following Junius (June) and preceding Sextilis (August). ''Quintilis'' is Latin for "fifth": it was the fifth month (''quintilis mensis'') in the earliest calendar attributed t ...

). A proclamation was issued by the magistrate who would oversee the elections in a public meeting – a ''contio'' – which was memorialised in writing and posted publicly.

Roman religion

Religion in ancient Rome consisted of varying imperial and provincial religious practices, which were followed both by the people of Rome as well as those who were brought under its rule.

The Romans thought of themselves as highly religious, ...

permeated this process and elections could not be held on days which were reserved for religious business (such as the , unlucky days, reserved for purification). After the ''lex Caecilia Didia

The ''lex Caecilia Didia'' was a law put into effect by the consuls Q. Caecilius Metellus Nepos and Titus Didius in the year 98 BC. This law had two provisions. The first was a minimum period between proposing a Roman law and voting on it, and th ...

'' in 98 BC, a – three market days (market days occurred every eight days) – was observed between the announcement and taking place of elections. Prior to the election itself, auguries also had to be taken to screen for inauspicious omens. Moreover, all elections had to be conducted within a single day prior to nightfall.

After a public prayer calling on the support of the gods for the Roman people and those who were to be elected, the magistrate instructed the citizens to divide () and to vote (). Citizens then reported to their relevant division and presented themselves to officials who would record their vote.

The '' comitia centuriata'' elected the

consuls

A consul is an official representative of a government who resides in a foreign country to assist and protect citizens of the consul's country, and to promote and facilitate commercial and diplomatic relations between the two countries.

A consu ...

, praetor

''Praetor'' ( , ), also ''pretor'', was the title granted by the government of ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected ''magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to disch ...

s, and censors. There were 193 voting blocks, called ''centuries'', which always convened outside Rome on the . Citizens were assigned to centuries based on their age and wealth, with the old and wealthy receiving more centuries as a proportion of the population. Reforms intervened in the third century BC to link the number of centuries to the number of tribes. Specifically, the first census class which had eighty centuries was reduced to seventy; this created one junior and senior century – members divided by age – for each of the thirty-five tribes. However, the resulting division of centuries for the second through fifth classes (their number did not change) is not known. Regardless, even after these reforms, the centuries remained malapportioned heavily in favour of older and wealthier citizens.

Prior to those reforms, when the consul ordered the centuries to divide and vote, the eighteen equestrian centuries were first to vote. After the reforms, the first to vote was the , selected by lot from the junior centuries of the first class. This century's result was immediately announced and was widely seen as an omen on the election: Cicero notes that this result secured the election of at least one of the consuls. Roman religion regularly interpreted chance emerging from lot as divining the will of the gods. The result from the prerogative century had religious significance; it also served a political purpose by randomising results – minimising divisions within the oligarchy – and nudging the remaining centuries to vote accordingly.

After the prerogative century, the remaining junior centuries of the first class voted, followed by the first class' senior centuries and the eighteen equestrian centuries. After those eighty-eight (88) centuries voted, the second class was called. Because the first class, equestrians, and second class made up a majority of voting units, if they all agreed on who should be elected, all posts would now be filled and voting would then end. Only when upper divisions disagreed did the lower classes, called in rank order, vote. Substantial debate has been had over whether elections continued into the lower classes due to divisions in the upper ones; views range from rare extension into the third class to elections regularly extension into the fourth.

The '' comitia tributa'' elected all other magistrates, including the

aedile

Aedile ( , , from , "temple edifice") was an elected office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings () and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to enforce public orde ...

s, plebeian tribune

Tribune of the plebs, tribune of the people or plebeian tribune () was the first office of the Roman state that was open to the plebeians, and was, throughout the history of the Republic, the most important check on the power of the Roman Senate ...

s, quaestor

A quaestor ( , ; ; "investigator") was a public official in ancient Rome. There were various types of quaestors, with the title used to describe greatly different offices at different times.

In the Roman Republic, quaestors were elected officia ...

s, and military tribune

A military tribune () was an officer of the Roman army who ranked below the legate and above the centurion. Young men of Equestrian rank often served as military tribunes as a stepping stone to the Senate. The should not be confused with the ...

s. While there has been made a distinction between a called by the normal magistrates that includes patricians and a called by plebeian tribunes of plebeians

In ancient Rome, the plebeians or plebs were the general body of free Roman citizens who were not Patrician (ancient Rome), patricians, as determined by the Capite censi, census, or in other words "commoners". Both classes were hereditary.

Et ...

only, it is not clear whether this distinction mattered. Regardless, both operated under the same procedure and were differentiated only by the presiding magistrate.

The assembly had, by 241 BC, thirty-five voting blocks called tribes (). Citizens were assigned to tribes based on where they resided. Four of the thirty-five tribes were assigned to the city of Rome itself and called "urban" tribes. These tribes too were malapportioned since there was no guarantee that each tribe would have an at all similar number of voters. The rest of the tribes, termed "rural", could also encompass territory extremely distant from Rome, which, due to the requirement that all votes had to be given at Rome, has led to many scholars viewing those voters as effectively disenfranchised. Whether this was actually the case, however, is debated.

The traditional meeting place of an electoral tribal assembly was the Forum

Forum or The Forum may refer to:

Common uses

*Forum (legal), designated space for public expression in the United States

*Forum (Roman), open public space within a Roman city

**Roman Forum, most famous example

* Internet forum, discussion board ...

– near the rostra

The Rostra () was a large platform built in the city of Rome that stood during the republican and imperial periods. Speakers would stand on the rostra and face the north side of the Comitium towards the senate house and deliver orations to t ...

and comitium

The Comitium () was the original open-air public meeting space of Ancient Rome, and had major religious and prophetic significance. The name comes from the Latin word for "assembly". The Comitium location at the northwest corner of the Roman Foru ...

– or the summit of the Capitoline Hill

The Capitolium or Capitoline Hill ( ; ; ), between the Roman Forum, Forum and the Campus Martius, is one of the Seven Hills of Rome.

The hill was earlier known as ''Mons Saturnius'', dedicated to the god Saturn (mythology), Saturn. The wo ...

near the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus

The Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, also known as the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus (; ; ), was the most important temple in Ancient Rome, located on the Capitoline Hill. It was surrounded by the ''Area Capitolina'', a precinct where numer ...

. It is not known when exactly these electoral assemblies were moved to the , but it was certainly after the tribunate of Tiberius Gracchus

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus (; 163 – 133 BC) was a Roman politician best known for his agrarian reform law entailing the transfer of land from the Roman state and wealthy landowners to poorer citizens. He had also served in the ...

in 133 BC. After the move, the voters were there divided into their tribes by wooden fencing and rope.

The first tribe to be called, the , was selected by lot among the thirty-one rural tribes. Prior to the move to the , the tribes then voted in a sequence set by lot. However, after the move, the tribes then all voted simultaneously. It it not known whether there was an sequence of voters within each tribe. While all tribes voted simultaneously, their results were announced in an order determined by lot: this continued until a candidate received the votes of 18 tribes, a majority. Once the number of candidates corresponding to the number of open offices had been elected, all remaining votes were discarded.

Elections, however, to the post of pontifex maximus were different. He was not elected by the whole Roman people. Under the presidency of a , seventeen tribes – one less than a majority – selected by lot then voted under the same procedure. Between 104 and the dictatorship

A dictatorship is an autocratic form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, who hold governmental powers with few to no Limited government, limitations. Politics in a dictatorship are controlled by a dictator, ...

of Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (, ; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman of the late Roman Republic. A great commander and ruthless politician, Sulla used violence to advance his career and his co ...

, and then after 63 BC, this was also extended to all priesthoods.

After the election

The presiding magistrate had the power to reject electoral results both of the election as a whole and of any one voting block. Magistrates were elected for a specific term. Winners of elections which took place before that term started became magistrates-designate; winners of elections within the term itself assumed office immediately either because elections could not have been held previously or because the previous officeholder was dead. Most magistracies took office at the start of the new year which after 153 BC was set to be 1 January. However, before they could take office, a trial for electoral bribery could intervene. This was instituted some time by 115 BC, when the first known trial – that ofGaius Marius

Gaius Marius (; – 13 January 86 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. Victor of the Cimbrian War, Cimbric and Jugurthine War, Jugurthine wars, he held the office of Roman consul, consul an unprecedented seven times. Rising from a fami ...

in praetorian elections – was held. By the late republic, a permanent court ('' quaestio'') was established for such cases and allegations of electoral bribery were extremely common. In some cases, the whole slates of victors could be prosecuted, as in the consular elections of 65 BC. That year, the two consuls-designate were convicted and the results were thrown out, with elections held anew. The corrupt winners were removed from the senate and disqualified from office for ten years. Legislation in the late republic made such penalties more severe, with exile being decreed the punishment after the ''lex Tullia'' in 63 BC and further penalties also extended to those who assisted candidates in distributing those bribes.

Moreover, for those magistrates with ''imperium

In ancient Rome, ''imperium'' was a form of authority held by a citizen to control a military or governmental entity. It is distinct from '' auctoritas'' and '' potestas'', different and generally inferior types of power in the Roman Republic a ...

'', a further vote was customary before the '' comitia curiata''. During the republican period, this assembly, which was theoretically made up of thirty curiae into which all Roman citizens were assigned, was a pro forma affair. Instead, the entire people were symbolically represented by thirty lictor

A lictor (possibly from Latin language, Latin ''ligare'', meaning 'to bind') was a Ancient Rome, Roman civil servant who was an attendant and bodyguard to a Roman magistrate, magistrate who held ''imperium''. Roman records describe lictors as hav ...

s who would in all cases ritually vote through a ''lex curiata de imperio'' bestowing the power of command on the magistrate as it had been in the days of the kings.

Candidature

According to Polybius, candidates had to have served ten years military service. This military service requirement, however, was largely ignored by the late republic. Candidates also were required to not have been convicted of any crimes, not currently be the subject of pending legal proceedings, and show three generations of free (non-slave) ancestors. Candidates also had to be eligible, of course, for the office they were standing for. This took the form of a specific and sequential order of posts, the ("course of honours") which was prescribed by law with minimum age requirements. The first version of a law to that effect was the by Lucius Villius dated by Livy to 180 BC. This first law required that someone wait, at a minimum, two years between magistracies and set minimum ages for the consulship and praetorship. Requirements were restated by Sulla's in 81 BC, setting minimum ages for the quaestorship, praetorship, and consulship at 30, 39, and 42 years, respectively. Candidature was professed to the prospective presiding magistrate () some time before the election. Under the it seems this was immediately after the elections were announced. The had to be in person at Rome, though for candidates this was merely the start of the official campaign: candidates regularly started their campaigns well earlier to build support when the time came. If the candidate convinced the presiding magistrate that all requirements were met he was added to the list of candidates. There was a deadline for candidacy and after the list was finalised it could not be changed. There were also no write-in ballots: a vote for a person not on the list of candidates was discarded.Campaigning

The campaign itself was called the . The main source on Roman campaigning is the '' Commentariolum Petitionis'' which is attributed to

The campaign itself was called the . The main source on Roman campaigning is the '' Commentariolum Petitionis'' which is attributed to Quintus Tullius Cicero

Quintus Tullius Cicero ( , ; 102 BC – 43 BC) was a Roman statesman and military leader, as well as the younger brother of Marcus Tullius Cicero. He was born into a family of the equestrian order, as the son of a wealthy landowner in Arpinum, so ...

(younger brother of the orator and consul of 63). The main subject of Roman campaigns were personal factors relating to a candidate's personal merits and public image with comparison to negative traits of rival candidates. Politicians also cultivated the favour of various groups from different parts of society and made attempts to curry undecided voters.

At consular elections, because Roman elections were highly weighted towards the wealthy (ie timocratic), campaigns largely revolved around the elite and the top two or three census classes. However, candidates did seek the favour of less well-off citizens since they could serve to influence patrons in the higher census classes. Indeed, candidates (who were mostly members of the aristocracy) were expected to come to the Forum

Forum or The Forum may refer to:

Common uses

*Forum (legal), designated space for public expression in the United States

*Forum (Roman), open public space within a Roman city

**Roman Forum, most famous example

* Internet forum, discussion board ...

or other public areas, greeting prospective voters of all classes in person.

However, there were no political parties: "it is common knowledge nowadays that ''populares

''Optimates'' (, ; Latin for "best ones"; ) and ''populares'' (; Latin for "supporters of the people"; ) are labels applied to politicians, political groups, traditions, strategies, or ideologies in the late Roman Republic. There is "heated ...

'' did not constitute a coherent political group or 'party' (even less so than their counterparts, ''optimates

''Optimates'' (, ; Latin for "best ones"; ) and ''populares'' (; Latin for "supporters of the people"; ) are labels applied to politicians, political groups, traditions, strategies, or ideologies in the late Roman Republic. There is "heated ...

'')". Ideological campaigns were generally frowned upon – the ''Commentariolum Petitionis'' in fact recommends avoiding state affairs entirely – but did occur sporadically: candidates occasionally proposed policies when standing for the plebeian tribunate

Tribune of the plebs, tribune of the people or plebeian tribune () was the first office of the Roman state that was open to the plebeians, and was, throughout the history of the Republic, the most important check on the power of the Roman Senate ...

or expressed opinions on military affairs as candidates for the consulship.

Successful candidates attempted to build name recognition from the start of their careers. One avenue for this was prosecutions in the courts. Politicians also attempted to have themselves elected aedile

Aedile ( , , from , "temple edifice") was an elected office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings () and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to enforce public orde ...

so to sponsor extravagant public games and spectacles to curry favour with the voting public. During the campaign itself, candidates wore a bright white toga

The toga (, ), a distinctive garment of Ancient Rome, was a roughly semicircular cloth, between in length, draped over the shoulders and around the body. It was usually woven from white wool, and was worn over a tunic. In Roman historical tra ...

() and met voters in person in the forum while accompanied by large groups of supporters to build prestige. Without the right to call rallies or public meetings, which was the exclusive prerogative of the sitting magistrates, candidates would instead host political banquets providing food to the public or give away tickets to games or shows.

Endorsements were also of value. These came from family, personal friends, political allies (called "friends"; ), and clients. Allies were those who shared outlooks and expected to collaborate on shared matters in the senate and other parts of public life; however, these alliances were many times short and fluid. Clients could sometimes be won, as in the case of Cicero, by defence in the courts. The role of family and ancestry was also very important: those with consular ancestors made reference thereto. While men like Sallust, Cicero, and Marius expressed some bitterness about the old aristocracy's advantages, the Roman voters and the electoral results – which returned the scions of a small number of powerful and prestigious families to the most senior posts – evidently reflected their importance.

Corruption

Fundraising was necessary since Roman campaigns were extremely expensive: candidates drew from their own fortunes, received support from friends or political allies, and also borrowed huge sums to finance their campaigns. There were no controls over political donations or fundraising in republican times. There were, however, limitations on what campaign funds could be used for: especially campaign events thought to be too luxurious. Laws were also passed to prohibit electoral bribery () but this was not a prohibition of gifts or bribes per se; only gifts which cut across existing client-patron relationships were regulated. Some scholars paint a picture of an effective market for votes where the fact that a single elector could vote in multiple elections in succession, "two consular candidates, eight praetorian candidates, and two curule aediles, not to mention quaestors and lebeian magistrates. This is a picture of cash bribes from candidates to voters – in 54 BC the was supposedly promised ten million sesterces if it would vote for two certain candidates – accumulating in the pocket of a voter after some twelve successive bribes along with free banquets, shows, event tickets, and food handouts paid from multiple candidates all paid for at each candidate's personal expense. Many series of restrictions on candidates' expenses came into effect through the late republic. This included restrictions on the size of banquets, the number of campaign staff, and the value of gifts. However, it was possible in the late republic to evade many of these restrictions by having a supposed third-party distribute the gifts on a candidate's behalf. Moreover, consistent with patronage relations at Rome, it was relatively accepted for candidates to distribute gifts – such as tickets to gladiatorial shows and banquets – to members of their own electoral tribe and within pre-existing patronage relationships.History and development

The development of Roman elections is not very clear, as is much of early Roman history. Sources on this early period, which were written by and for the (a class of elites defined by their repeated election to the highest magistracies), are anachronistic and unclear. Nor is it clear that the early republic had elections: the early republic in the fifth century might not have had any central state organisation to which magisterial elections could have meaningfully applied; nor is it concretely known whether Rome was governed in this early period by consuls or whether the divide between plebs and patricians so emphasised in the annalistic accounts was as absolute as commonly claimed.Early elections and acclamation

TheLatin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

vocabulary for elections and voting implies early voting was largely acclamatory, where the purpose of elections was to affirm popular consent for elite leadership choices. The earliest Roman assemblies were those of the which acclaimed the kings, predating the republic, by swearing an oath to obey the monarch and possibly banging weapons to signal their assent. The formal procedure of Roman elections reflects this archaic procedure and it is likely that during the early republic the magistrates merely designated successors and called assemblies so that the people could voice their approval.

This historical context meant that the power of the presiding magistrate over an electoral assembly was vast. Even after competitive elections with multiple candidates were introduced, magistrates had the ability to throw out voting results (though this was exercised rarely due to protest; a magistrate acting without support usually gave way). Moreover, the early republic saw the ability of the senate to interfere in elections: decisions of the assemblies required approval of the senate and it was not until the third century which required the senate to approve elections ''prior'' to their taking place rather than ''after'' their results were in.

While the Romans recognised three different popular assemblies, the , , and , only the last two had much relevance under the classical constitution. All of the various were believed to date back into the regal period. Competitive elections, marked by the creation of the combined patrician and plebeian elite which defined its self-worth in terms of repeated election to the magistracies (the ), developed some time between 367–287 BC with the close of the struggle of the orders

The Conflict of the Orders or the Struggle of the Orders was a political struggle between the plebeians (commoners) and patricians (aristocrats) of the ancient Roman Republic lasting from 500 BC to 287 BC in which the plebeians sought political ...

.

Reform in the middle and late republics

The number of magistrates to be elected annually increased over time as the number of praetors, quaestors, and other minor magistrates rose. By the late republic, there were some forty-four senior magistrates elected every year. There were also major reforms in the way the elections were run. The was reformed some time between 241 and 216 BC, though probably also before 221 BC. The original Servian distribution of the centuries, where beyond the eighteen equestrian and five supernumerary centuries, the first class had eighty centuries while the remaining classes had twenty (except the fifth class with thirty) was abolished. Replacing it was a system which aligned the centuries to tribes, assigning two centuries for each tribe to the first class; the total number of centuries however remained the same. The other classes also likely received tribally-designed centuries but specific mechanism for how the 280 centuries of the second through fifth classes were transformed into 100 voting centuries is not known. One suggestion, brought byTheodor Mommsen

Christian Matthias Theodor Mommsen (; ; 30 November 1817 – 1 November 1903) was a German classical scholar, historian, jurist, journalist, politician and archaeologist. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest classicists of the 19th ce ...

and suggested by the , is that each lower class received seventy centuries which were then combined by lot or custom into those 100 total voting centuries.

The rationale for the reform has been variously explained. Some have suggested that it was intended to more equitably distribute the centuries among the people; Others have denied its impacts. The most insipid explanation, however, would be an ''increase'' in the ruling class' voting power by taking its control of the tribes – where rural magnates enjoyed a substantial advantage – and mapping it directly onto the centuries as well.

The passage of the in 180 fixed minimum ages at which men became eligible to certain offices. By imposing a higher age requirement on the consulship, it also formally placed it at the top of the Roman magisterial order and likely reflected the full development of the ("course of honours").

The passed in 139 BC required that votes in elections, which had previously been oral, be inscribed in small wax tablets. This replaced oral tallying done by election officials, who then on counted the tablets and tallied the votes afterwards. Concerns about pressure on voters seems to have remained regular through the 2nd century BC with legislation brought by Gaius Gracchus

Gaius Sempronius Gracchus ( – 121 BC) was a reformist Roman politician and soldier who lived during the 2nd century BC. He is most famous for his tribunate for the years 123 and 122 BC, in which he proposed a wide set of laws, i ...

and Gaius Marius

Gaius Marius (; – 13 January 86 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. Victor of the Cimbrian War, Cimbric and Jugurthine War, Jugurthine wars, he held the office of Roman consul, consul an unprecedented seven times. Rising from a fami ...

, 123–22 BC and 119 BC respectively, mandating secret ballot

The secret ballot, also known as the Australian ballot, is a voting method in which a voter's identity in an election or a referendum is anonymous. This forestalls attempts to influence the voter by intimidation, blackmailing, and potential vote ...

in courts and the physical separation of voters and crowds. Secret ballot was phased in to all assembly business by incremental legislation after 139 BC: the of 137 brought it to non-capital trials; the of 131 brought it to legislative ; and the of 106 brought it to capital trials. In 104 BC, secret ballot was also introduced for election to priesthoods

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

. The successive introduction of secret ballot had the effect of making it more difficult to gain votes by bribery while also giving assemblies more political independence, further splintering political consensus within the republic. Secret ballot's introduction, qua anticorruption measure, has also been connected to legislation that came into effect in this period establishing permanent courts to try allegations of electoral bribery.

The period also saw, however, an expansion in the extent of political violence. The first instance was the death of the plebeian tribune Tiberius Gracchus

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus (; 163 – 133 BC) was a Roman politician best known for his agrarian reform law entailing the transfer of land from the Roman state and wealthy landowners to poorer citizens. He had also served in the ...

in 133 BC while he was standing for re-election, followed by the killing of his brother Gaius

Gaius, sometimes spelled Caius, was a common Latin praenomen; see Gaius (praenomen).

People

* Gaius (biblical figure) (1st century AD)

*Gaius (jurist) (), Roman jurist

* Gaius Acilius

* Gaius Antonius

* Gaius Antonius Hybrida

* Gaius Asinius Gal ...

and Marcus Flaccus in 122 BC at the decree of the Senate. Urban violence continued, with two candidates at the elections of 100 BC, Lucius Appuleius Saturninus

Lucius Appuleius Saturninus (died late 100 BC) was a Roman populist and tribune. He is most notable for introducing a series of legislative reforms, alongside his associate Gaius Servilius Glaucia and with the consent of Gaius Marius, during t ...

and Gaius Servilius Glaucia

Gaius Servilius Glaucia (died late 100 BC) was a Roman politician who served as praetor in 100 BC. He is most well known for being an illegal candidate for the consulship of 99 BC. He was killed during riots and political violence i ...

, murdering one of their electoral competitors. Order was again restored by a decree of the Senate but the two were killed by a mob after their capture. The reforms initiated from the 130s onward, along with the normalisation of violence in the political sphere, have been read as implying a widespread recognition of the need for reform and dissatisfaction with republican political institutions.

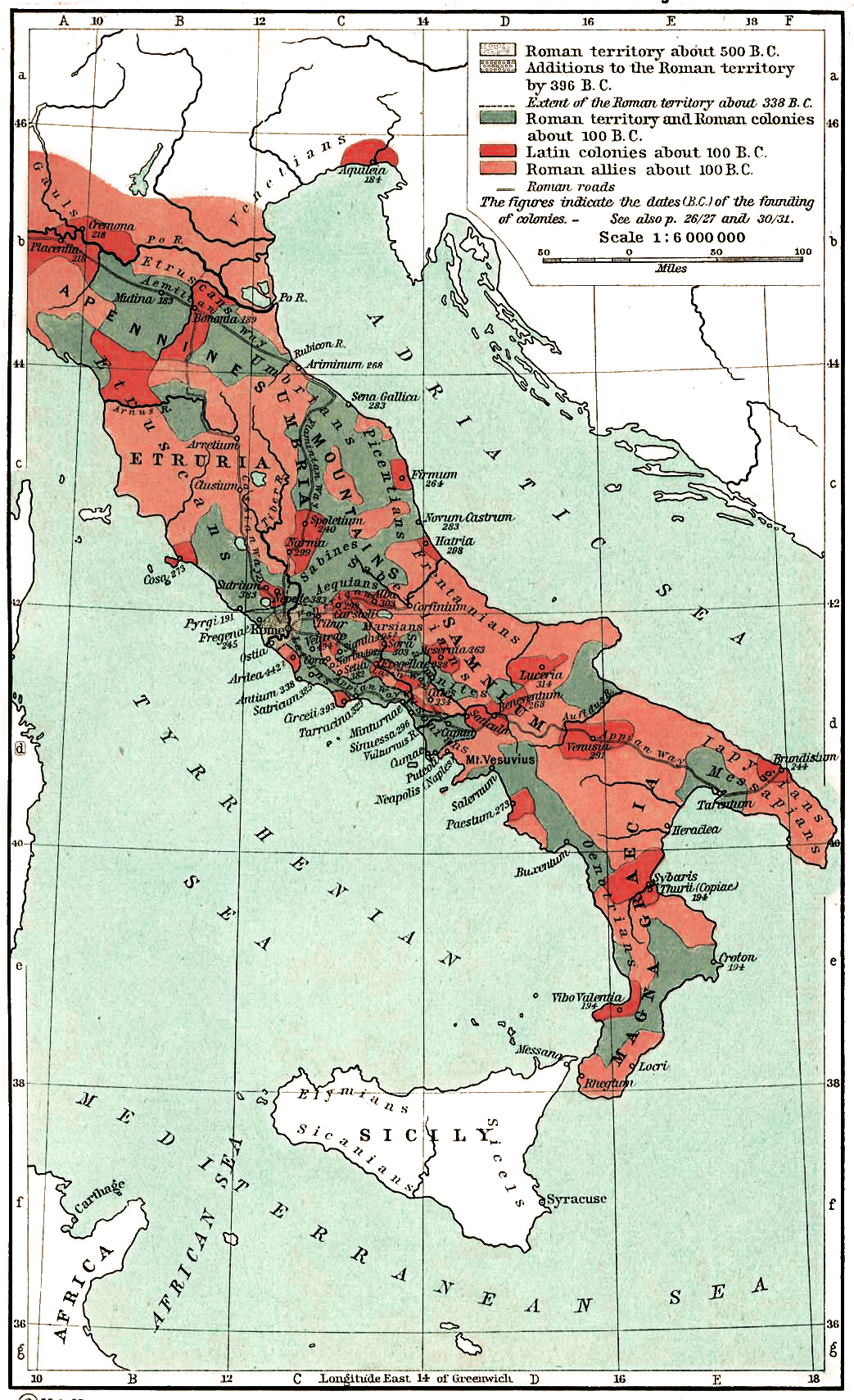

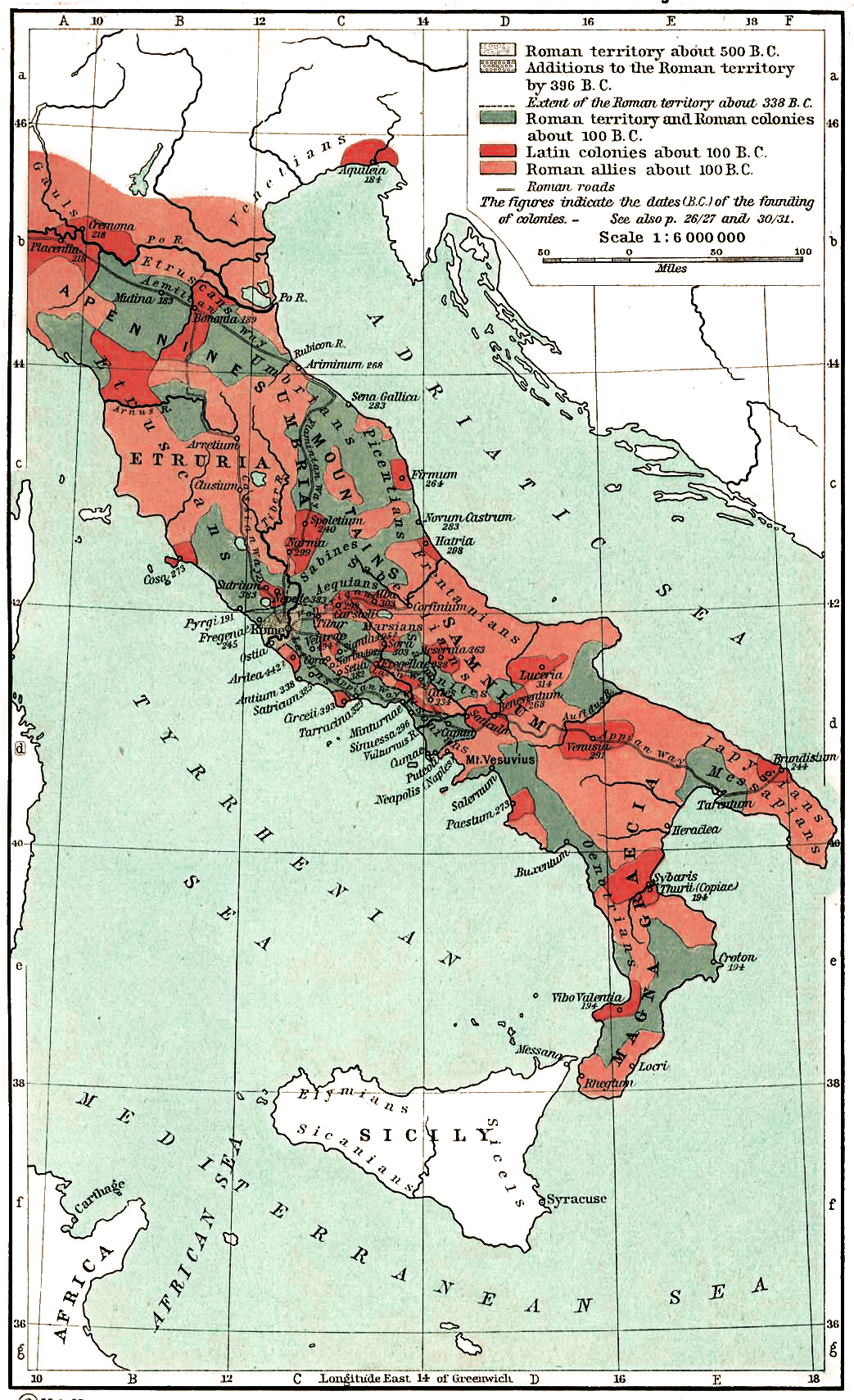

Enfranchisement of Italy

The Social War, fought between the Romans and their Italian allies, saw the Italian allies mostly put down their arms when the republic, through the '' lex Julia de civitate'' and ''

The Social War, fought between the Romans and their Italian allies, saw the Italian allies mostly put down their arms when the republic, through the '' lex Julia de civitate'' and ''lex Plautia Papiria

The was a Roman plebiscite enacted amidst the Social War in 89 BCE. It was proposed by the plebeian tribunes Marcus Plautius Silvanus and Gaius Papirius Carbo. The law further extended Roman citizenship to Italian communities – expanding the ...

'', extended Roman citizenship

Citizenship in ancient Rome () was a privileged political and legal status afforded to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Citizenship in ancient Rome was complex and based upon many different laws, traditions, and cu ...

to those allies. The two laws immediately started a row over how the new citizens were to be distributed within the centuries and tribes. The initial plan was to confine the new citizens into a limited number of new tribes. Under those laws, the entire mass of new citizens were to be confined to a limited number of tribes (ten new ones per Appian

Appian of Alexandria (; ; ; ) was a Greek historian with Roman citizenship who prospered during the reigns of the Roman Emperors Trajan, Hadrian, and Antoninus Pius.

He was born c. 95 in Alexandria. After holding the senior offices in the pr ...

, eight existing ones per Velleius

Marcus Velleius Paterculus (; ) was a Roman historian, soldier and senator. His Roman history, written in a highly rhetorical style, covered the period from the end of the Trojan War to AD 30, but is most useful for the period from the death o ...

). These attempts to contain the Italians' political influence continued through the immediately following census of 89 BC, where the presiding censors may have deliberately botched the religious aspects of the census so to delay the new citizens' enrolment. The question of new tribes was settled after 86 BC when the senate – intimidated by Lucius Cornelius Cinna

Lucius Cornelius Cinna (before 130 BC – early 84 BC) was a four-time consul of the Roman republic. Opposing Sulla's march on Rome in 88 BC, he was elected to the consulship of 87 BC, during which he engaged in an armed conf ...

's troops after a short civil conflict

The Civil Conflict (sometimes styled as the conFLiCT) was the name given by former UConn Huskies football head coach Bob Diaco to Connecticut's annual matchup against the UCF Knights football team of the University of Central Florida. The team ...

– decreed that no new tribes were to be created and that the new citizens be enrolled into the existing thirty-one rural tribes; however, actual enrolment into the tribes and centuries would take at least until the census of 70 BC. Even when Lucius Cornelius Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (, ; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman of the late Roman Republic. A great commander and ruthless politician, Sulla used violence to advance his career and his co ...

returned from the east to start a civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, he was forced to give assurances that he would not disturb the new citizens' assignment.

The expansion of citizenship to Italy contributed greatly to the approximate doubling of the citizenry between 86 and 70 BC, from 463,000 to 910,000 male citizens. The new citizens, even before their full registration, were mobilised for political interests: Cinna, by linking his victory in civil conflict with support for Italian enrolment in the existing tribes, was able to mobilise an army sufficient to defeat and overawe his consular colleague and much of the senate. Late republican documents such as the '' Commentariolum Petitionis'' indicate the importance the new citizens and a candidate's need to maintain good relations with the Italian magnates in the upper centuries. Sulla, in victory, also recruited many new senators from the Italian municipalities; however, many other victims of his proscriptions and their descendants were also disqualified from office. Ambitious men from Italian towns had opportunities opened to them at Rome, to become candidates and victors in contests for magistracies. These new men increased the competitiveness of elections and, amid an expanded electorate, found themselves within a more opaque electorate; they responded to these competitive pressures with greater bribery and violence, which complicated and raised the stakes of politics. The greater numbers of citizens also further reduced the representativeness of assemblies, who now represented men who would likely never exercise their suffrage rights.

End of elections

Caesar's civil war

Caesar's civil war (49–45 BC) was a civil war during the late Roman Republic between two factions led by Julius Caesar and Pompey. The main cause of the war was political tensions relating to Caesar's place in the Republic on his expected ret ...

, which started in January 49 BC, triggered a disruption in competitive elections. For much of Caesar's war in the provinces against his enemies, elections were held late or irregularly. They also were heavily stage-managed, with Caesar presenting and commending only a few candidates who invariably were declared victorious. The circumcision of the Roman people's choice, backlash among the aristocracy which defined their self-worth in winning such electoral contests, and the decline in expenditures by candidates – cutting off voters from candidates' largesse – were factors which led to Caesar's growing unpopularity before his eventual assassination in 44 BC. In the aftermath of Caesar's death, his selections for offices years into the future were regardless retained. And in the war that followed the next year, elections were decided not by votes but by the intimidation of soldiers. In the triumviral period that followed, the results of elections were set by political expediency rather than by any kind of popular choice.

The putative "restoration of the republic" which Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

began in 28 BC saw him elected consul through to 23 BC while exercising substantial control over elections; his abandonment of the consulship in 23 saw a return to robust electioneering and competition at Rome. The attempt in 19 BC, by a urban pleb uprising, to secure the consulship for Marcus Egnatius Rufus, was suppressed by the lone consul and the senate with force. Following those elections and Egnatius' death, news of public electoral competition for the consulship largely disappears. Through the most of Augustus' reign, however, he continued to exert influence through broadly traditional republican means by campaigning for his men before the people.

A law in AD 5, the ''lex Valeria Cornelia'', gave certain centuries of senators and equites – originally ten, later expanded by AD 23 to 20, – who would meet before the formal elections to select preferred candidates termed ''destinati''. Their preferred candidates were announced and immediately afterwards the rest of the comitia voted. The most convincing explanation for its purpose was to ensure orderly elections by showing the ''auctoritas'' (social influence) of the senate and equites while minimising public electoral canvassing, bribery, and riots. Regardless, at various times during Augustus' reign, riots or other disorders showed the emperor's domination of the state more clearly: in 19 BC he created a consul and amid failed elections in AD 7 appointed all the magistrates directly. These actions may have been scrupulously ratified by law but showed the limited freedom of choice available to electors.

Shortly after Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus ( ; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was Roman emperor from AD 14 until 37. He succeeded his stepfather Augustus, the first Roman emperor. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC to Roman politician Tiberius Cl ...

' accession to the throne, candidates for the praetorship would be selected by the emperor and by the senate: the emperor would select four with the senate selecting the others. The candidates were then submitted en bloc to the for ratification. By transferring these nominations to the senate, aristocratic competition became unmoored from popular support. Accordingly, prospective candidates cut back on expenditures for the expensive games and other festivals that had previously been necessary to win such support. For a short period under Caligula

Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August 12 – 24 January 41), also called Gaius and Caligula (), was Roman emperor from AD 37 until his assassination in 41. He was the son of the Roman general Germanicus and Augustus' granddaughter Ag ...

, the elections for praetor were transferred back to the people, to their benefit, as candidates again paid them attention and the people benefited from their electoral largesse. The added expenses proved unpopular with the senatorial elite, who forced a return to Tiberius' en bloc approach after Caligula's death.

By the later Roman empire, the in Rome was irrelevant. The ''saepta Julia

The Saepta Julia was a building in the Campus Martius of Rome, where citizens gathered to cast votes. The building was conceived by Julius Caesar and dedicated by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa in 26 BC. The building replaced an older structure, called t ...

'' in Rome had by this point long lost any electoral capacity – it was opened in 26 BC by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa

Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa (; BC – 12 BC) was a Roman general, statesman and architect who was a close friend, son-in-law and lieutenant to the Roman emperor Augustus. Agrippa is well known for his important military victories, notably the B ...

and was shortly thereafter converted into a shopping centre – and the ability to appoint magistrates had long been transferred to the emperor. The formerly republican state of affairs was not forgotten, however. For example, one of the consuls of AD 379, Ausonius

Decimius Magnus Ausonius (; ) was a Latin literature, Roman poet and Education in ancient Rome, teacher of classical rhetoric, rhetoric from Burdigala, Gallia Aquitania, Aquitaine (now Bordeaux, France). For a time, he was tutor to the future E ...

, in a speech thanked the emperor Gratian

Gratian (; ; 18 April 359 – 25 August 383) was emperor of the Western Roman Empire from 367 to 383. The eldest son of Valentinian I, Gratian was raised to the rank of ''Augustus'' as a child and inherited the West after his father's death in ...

, remarking:

At the municipal level, rather than that of the Roman state, elections continued. Many communities had local bylaws modelled on the republican system with local senates, magistrates (the highest usually titled ''duoviri''), and voting blocks. Archaeological evidence from Pompeii

Pompeii ( ; ) was a city in what is now the municipality of Pompei, near Naples, in the Campania region of Italy. Along with Herculaneum, Stabiae, and Villa Boscoreale, many surrounding villas, the city was buried under of volcanic ash and p ...

also indicates that into the Flavian period elections at this level were still vigorously contested before the local citizens. This state of affairs continued at least into the late second century AD.

Popular participation

Elections were extremely important in terms of converting political initiative to policy. While the assemblies had plenary legislative authority, they had no right of initiative, meaning they were dominated entirely by the executive magistrates. Because of this structure, the election of magistrates was the only means through which popular demands could be translated into state action. By the middle of the 20th century and especially afterRonald Syme

Sir Ronald Syme, (11 March 1903 – 4 September 1989) was a New Zealand-born historian and classicist. He was regarded as the greatest historian of ancient Rome since Theodor Mommsen and the most brilliant exponent of the history of the Roma ...

's ''Roman Revolution

''The Roman Revolution'' (1939) is a scholarly study of the final years of the ancient Roman Republic and the creation of the Roman Empire by Caesar Augustus. The book was the work of Sir Ronald Syme (1903–1989), a noted Tacitean scholar, and w ...

'' (1939), scholars had largely settled on an oligarchic framework for understanding republican politics. The oligarchic conception of republican politics is predicated on the dominance of the aristocracy over the voting population; in the early 20th century the mechanism for this dominance was generally thought to be interlocking system of client–patron relationships emanating from factions of powerful noble families in the political centre. By the mid-20th century later scholars had refined the oligarchic view and discarded its reliance on permanent family-based factions and patronage to control voters. Regardless, in this view, the natural conservatism of Roman voters – conditioned to vote for the scions of famous families – along with personal cultivation of popular support, were then mainly arrayed to contest aristocratic interests such as military commands and legitimate aristocratic control of the state. There some reasons to believe republican politics was essentially oligarchic. While all Roman citizens were afforded the theoretical right to vote, the Roman tribes and centuries wildly malapportioned those votes. Compounding this difficulty, the Romans made no attempts to increase turnout, requiring that all public business occur within or nearby Rome, an expensive and special difficulty for citizens who lived in Italy or even further afield, such as in Cisalpine Gaul (modern northern Italy). Both factors trend towards most eligible voters, who lived far from Rome, declining to participate due to the costs involved in going to Rome to express a vote that had little value anyway. These incentives therefore implied a small and pliant electorate ready to uphold the aristocracy by bestowing legitimacy in consensus rituals.

The "Roman democracy" thesis was proposed in the 1980s by Fergus Millar

Sir Fergus Graham Burtholme Millar, (; 5 July 1935 – 15 July 2019) was a British ancient historian and academic. He was Camden Professor of Ancient History at the University of Oxford between 1984 and 2002. He is among the most influentia ...

and others, emphasising the importance of the voters in Roman assemblies and challenging the then-widespread oligarchic view as a "frozen waste". Millar instead argued that the republic's popular institutions were significant and allowed for citizens' initiatives to be transformed, if in a variable and imperfect way, to real political change at Rome.See, for overview, . Against senatorial domination of the state, Millar stressed the independence of plebeian tribunes and their use of the assemblies to enact legislation against the will of the broader aristocracy. Republican politicians' rhetorical themes of popular liberty () and ability to commit politically damaging gaffes suggests that winning and keeping large parts of society on side was a necessary skill in the highly competitive, or at least unpredictable, electoral environment. The enormous sums spent by campaigns on banquets and games for common people also suggests their influence in electoral outcomes. The large number of candidates in the late republic also had the effect of splitting votes, meaning that elections at least for the praetorship more readily involved the poorer voting classes. Such democratic interpretations also accord well with claims of high turnout, driven likely by organised local or political interest groups travelling to Rome en masse or individuals simply participating in civic ritual to "feel Roman".

There is, however, no hard evidence of turnout at Roman elections or legislative assemblies; what evidence is available is unrevealing because it is largely impressionistic. The limitations of the evidence are sufficient that it is not possible to prove or disprove that Roman elections saw high or low turnout. Evidence of low turnout is generally taken from the size of the voting spaces, which would imply total turnout of less than 60,000 if all voters had to fit within; whether this was a meaningful limit – for example, if voters could wait elsewhere until called to give their votes – is not known. If binding, such spaces imply turnout in the post-Social war era at most of 8% with turnout more likely in the range 0.66–1.85%. Even if not binding, it is difficult to countenance more than 10% of citizens participating. Under such circumstances, there has emerged a more compromise position which stresses both the importance of the popular element in electoral and political competition while also recognising considerable practical and cultural limits on popular pressure, especially when the ruling class was united. Such views place the electorate more as arbiters between factional alternatives within the ruling class (itself rarely united) rather than as a truly independent source of political initiative.

References

Bibliography

Modern sources

* ** ** * ** ** * ** ** * * * * * * * * * * Reprinted 2009. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Ancient sources

* * (Nine volumes.) *Further reading

* * *External links

* * {{Cite web , last=Devereaux , first=Bret , date=2023-07-28 , title=How to Roman Republic 101, part II: Romans, assemble! , url=https://acoup.blog/2023/07/27/collections-how-to-roman-republic-101-part-ii-romans-assemble/ , access-date=2025-05-18 , website=A Collection of Unmitigated PedantryRoman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

Elections in Europe

Government of the Roman Republic