Roger Bacon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Roger Bacon (; or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English

In 1237 or at some point in the following decade, he accepted an invitation to teach at the

In 1237 or at some point in the following decade, he accepted an invitation to teach at the  As a private scholar, his whereabouts for the next decade are uncertain but he was likely in Oxford –1251, where he met Adam Marsh, and in Paris in 1251. He seems to have studied most of the known

As a private scholar, his whereabouts for the next decade are uncertain but he was likely in Oxford –1251, where he met Adam Marsh, and in Paris in 1251. He seems to have studied most of the known

Medieval European philosophy often relied on appeals to the authority of

Medieval European philosophy often relied on appeals to the authority of

Bacon's 1267 ''Greater Work'', the ', contains treatments of

Bacon's 1267 ''Greater Work'', the ', contains treatments of

Vol. IIIPt. I

"The Affinity of Philosophy with Theology" ('), & (1900)

Vol. IIIPt. II

"On the Usefulness of Grammar" ('), & (1900)

Vol. IIIPt. III

"The Usefulness of Mathematics in Physics" ('), " On the Science of Perspective" ('), "On Experimental Knowledge" ('), and "A Philosophy of Morality" (').

It was not intended as a complete work but as a "persuasive preamble" ('), an enormous proposal for a reform of the

File:Roger Bacon-2.jpg, alt=, Spine of a 1750 edition of ''Opus majus''

File:Bacon - Opus maius, 1750 - 4325246.tif, alt=, Title page of 1750 edition of ''Opus majus''

File:Roger Bacon-1.jpg, alt=, First page of 1750 edition of ''Opus majus''

A passage in the ' and another in the ' are usually taken as the first European descriptions of a mixture containing the essential ingredients of

A passage in the ' and another in the ' are usually taken as the first European descriptions of a mixture containing the essential ingredients of

Bacon has been credited with a number of alchemical texts.

The ''Letter on the Secret Workings of Art and Nature and on the Vanity of Magic'' ('), also known as ''On the Wonderful Powers of Art and Nature'' ('), a likely-forged letter to an unknown "William of Paris," dismisses practices such as

Bacon has been credited with a number of alchemical texts.

The ''Letter on the Secret Workings of Art and Nature and on the Vanity of Magic'' ('), also known as ''On the Wonderful Powers of Art and Nature'' ('), a likely-forged letter to an unknown "William of Paris," dismisses practices such as

Bacon states that his ''Lesser Work'' (') and ''Third Work'' (') were originally intended as summaries of the ' in case it was lost in transit. Easton's review of the texts suggests that they became separate works over the course of the laborious process of creating a fair copy of the ', whose half-million words were copied by hand and apparently greatly revised at least once.

Other works by Bacon include his "Tract on the Multiplication of Species" ('), "On Burning Lenses" ('), the ' and ', the "Compendium of the Study of Philosophy" and "of Theology" (' and '), and his ''Computus''. The "Compendium of the Study of Theology", presumably written in the last years of his life, was an anticlimax: adding nothing new, it is principally devoted to the concerns of the 1260s.

Bacon states that his ''Lesser Work'' (') and ''Third Work'' (') were originally intended as summaries of the ' in case it was lost in transit. Easton's review of the texts suggests that they became separate works over the course of the laborious process of creating a fair copy of the ', whose half-million words were copied by hand and apparently greatly revised at least once.

Other works by Bacon include his "Tract on the Multiplication of Species" ('), "On Burning Lenses" ('), the ' and ', the "Compendium of the Study of Philosophy" and "of Theology" (' and '), and his ''Computus''. The "Compendium of the Study of Theology", presumably written in the last years of his life, was an anticlimax: adding nothing new, it is principally devoted to the concerns of the 1260s.

Bacon was largely ignored by his contemporaries in favour of other scholars such as

Bacon was largely ignored by his contemporaries in favour of other scholars such as

Bk. VII, Ch. xvii, §7.

Greene's Bacon spent seven years creating a brass head that would speak "strange and uncouth aphorisms" to enable him to encircle

volume I

*

volume II

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * . * . * .

"Roger Bacon" – In Our Time 2017

* * *

1901–1906 Jewish Encyclopedia: Bacon, Roger

Roger Bacon Quotes

a

Convergence

*

* * [https://i.pinimg.com/736x/e2/ba/0e/e2ba0e78be05d6431464050bb5609867--medieval-philosophy-roger-bacon.jpg classic wood engraving of Roger Bacon's visage, appears in Munson and Taylor's "Jane's History of Aviation" c.1972] * {{DEFAULTSORT:Bacon, Roger 1220 births 1292 deaths 13th-century alchemists 13th-century astrologers 13th-century astronomers 13th-century English mathematicians 13th-century English philosophers 13th-century English Roman Catholic theologians 13th-century English scientists 13th-century translators 13th-century writers in Latin Alumni of the University of Oxford Catholic clergy scientists Catholic philosophers Christian Hebraists Empiricists English alchemists English Friars Minor English male non-fiction writers English music theorists English philosophers of language English philosophers of science English Roman Catholic writers English translators Grammarians of Latin Medieval Arabists Medieval English astrologers Medieval English astronomers Medieval occultists Medieval orientalists Metaphysicians Natural philosophers People from Ilchester, Somerset Philosophers of literature Philosophers of mind Scholastic philosophers

polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

, philosopher, scientist

A scientist is a person who Scientific method, researches to advance knowledge in an Branches of science, area of the natural sciences.

In classical antiquity, there was no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, philosophers engag ...

, theologian

Theology is the study of religious belief from a religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of ...

and Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent Religious institute, religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor bei ...

friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders in the Catholic Church. There are also friars outside of the Catholic Church, such as within the Anglican Communion. The term, first used in the 12th or 13th century, distinguishes the mendi ...

who placed considerable emphasis on the study of nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

through empiricism

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological view which holds that true knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience and empirical evidence. It is one of several competing views within epistemology, along ...

. Intertwining his Catholic faith with scientific thinking, Roger Bacon is considered one of the greatest polymaths of the medieval period

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

.

In the early modern era, he was regarded as a wizard and particularly famed for the story of his mechanical

Mechanical may refer to:

Machine

* Machine (mechanical), a system of mechanisms that shape the actuator input to achieve a specific application of output forces and movement

* Mechanical calculator, a device used to perform the basic operations o ...

or necromantic brazen head. He is credited as one of the earliest European advocates of the modern scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has been referred to while doing science since at least the 17th century. Historically, it was developed through the centuries from the ancient and ...

, along with his teacher Robert Grosseteste

Robert Grosseteste ( ; ; 8 or 9 October 1253), also known as Robert Greathead or Robert of Lincoln, was an Kingdom of England, English statesman, scholasticism, scholastic philosopher, theologian, scientist and Bishop of Lincoln. He was born of ...

. Bacon applied the empirical method of Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham (Latinization of names, Latinized as Alhazen; ; full name ; ) was a medieval Mathematics in medieval Islam, mathematician, Astronomy in the medieval Islamic world, astronomer, and Physics in the medieval Islamic world, p ...

(Alhazen) to observations in texts attributed to Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

. Bacon discovered the importance of empirical testing when the results he obtained were different from those that would have been predicted by Aristotle.

His linguistic work has been heralded for its early exposition of a universal grammar, and 21st-century re-evaluations emphasise that Bacon was essentially a medieval thinker, with much of his "experimental" knowledge obtained from books in the scholastic tradition. He was, however, partially responsible for a revision of the medieval university

A medieval university was a corporation organized during the Middle Ages for the purposes of higher education. The first Western European institutions generally considered to be universities were established in present-day Italy, including the K ...

curriculum, which saw the addition of optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of optical instruments, instruments that use or Photodetector, detect it. Optics usually describes t ...

to the traditional '.

Bacon's major work, the , was sent to Pope Clement IV in Rome in 1267 upon the pope's request. Although gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

was first invented and described in China, Bacon was the first in Europe to record its formula.

Life

Roger Bacon was born in Ilchester inSomerset

Somerset ( , ), Archaism, archaically Somersetshire ( , , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel, Gloucestershire, and Bristol to the north, Wiltshire to the east ...

, England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, in the early 13th century. His birth is sometimes narrowed down to 1210, 1213 or 1214, 1215 or 1220. The only source for his birth date is a statement from his 1267 ' that "forty years have passed since I first learned the '". The latest dates assume this referred to the alphabet

An alphabet is a standard set of letter (alphabet), letters written to represent particular sounds in a spoken language. Specifically, letters largely correspond to phonemes as the smallest sound segments that can distinguish one word from a ...

itself, but elsewhere in the ' it is clear that Bacon uses the term to refer to rudimentary studies, the trivium

The trivium is the lower division of the seven liberal arts and comprises grammar, logic, and rhetoric.

The trivium is implicit in ("On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury") by Martianus Capella, but the term was not used until the Carolin ...

or quadrivium that formed the medieval curriculum. His family appears to have been well off.

Bacon studied at Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

. While Robert Grosseteste

Robert Grosseteste ( ; ; 8 or 9 October 1253), also known as Robert Greathead or Robert of Lincoln, was an Kingdom of England, English statesman, scholasticism, scholastic philosopher, theologian, scientist and Bishop of Lincoln. He was born of ...

had probably left shortly before Bacon's arrival, his work and legacy almost certainly influenced the young scholar and it is possible Bacon subsequently visited him and William of Sherwood in Lincoln. Bacon became a Master at Oxford, lecturing on Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

. There is no evidence he was ever awarded a doctorate. (The title ' was a posthumous scholastic accolade.) A caustic cleric named Roger Bacon is recorded speaking before the king at Oxford in 1233.

In 1237 or at some point in the following decade, he accepted an invitation to teach at the

In 1237 or at some point in the following decade, he accepted an invitation to teach at the University of Paris

The University of Paris (), known Metonymy, metonymically as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, from 1150 to 1970, except for 1793–1806 during the French Revolution. Emerging around 1150 as a corporation associated wit ...

. While there, he lectured on Latin grammar

Latin is a heavily inflected language with largely free word order. Nouns are inflected for number and case; pronouns and adjectives (including participles) are inflected for number, case, and gender; and verbs are inflected for person, numbe ...

, Aristotelian logic

In logic and formal semantics, term logic, also known as traditional logic, syllogistic logic or Aristotelian logic, is a loose name for an approach to formal logic that began with Aristotle and was developed further in ancient history mostly b ...

, arithmetic

Arithmetic is an elementary branch of mathematics that deals with numerical operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. In a wider sense, it also includes exponentiation, extraction of roots, and taking logarithms.

...

, geometry

Geometry (; ) is a branch of mathematics concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. Geometry is, along with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. A mathematician w ...

, and the mathematical aspects of astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

and music

Music is the arrangement of sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm, or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Music is generally agreed to be a cultural universal that is present in all hum ...

. His faculty colleagues included Robert Kilwardby, Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus ( 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great, Albert of Swabia, Albert von Bollstadt, or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop, considered one of the great ...

, and Peter of Spain, who may later become Pope as Pope John XXI

Pope John XXI (, , ; – 20 May 1277), born Pedro Julião (), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 September 1276 to his death in May 1277. He is the only ethnically Portuguese pope in history.Richard P. McBrien, ...

. The Cornishman Richard Rufus was a scholarly opponent. In 1247 or soon after, he left his position in Paris.

As a private scholar, his whereabouts for the next decade are uncertain but he was likely in Oxford –1251, where he met Adam Marsh, and in Paris in 1251. He seems to have studied most of the known

As a private scholar, his whereabouts for the next decade are uncertain but he was likely in Oxford –1251, where he met Adam Marsh, and in Paris in 1251. He seems to have studied most of the known Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

and Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

works on optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of optical instruments, instruments that use or Photodetector, detect it. Optics usually describes t ...

(then known as "perspective", '). A passage in the ' states that at some point he took a two-year break from his studies.

By the late 1250s, resentment against the king's preferential treatment of his émigré Poitevin relatives led to a coup and the imposition of the Provisions of Oxford

The Provisions of Oxford ( or ''Oxoniae'') were constitutional reforms to the government of late medieval England adopted during the Oxford Parliament of 1258 to resolve a dispute between Henry III of England and his barons. The reforms were de ...

and Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

, instituting a baron

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often Hereditary title, hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than ...

ial council and more frequent parliaments. Pope Urban IV absolved the king of his oath in 1261 and, after initial abortive resistance, Simon de Montfort led a force, enlarged due to recent crop failures, that prosecuted the Second Barons' War

The Second Barons' War (1264–1267) was a civil war in Kingdom of England, England between the forces of barons led by Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, Simon de Montfort against the royalist forces of Henry III of England, King Hen ...

. Bacon's own family were considered royal partisans: De Montfort's men seized their property and drove several members into exile.

In 1256 or 1257, he became a friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders in the Catholic Church. There are also friars outside of the Catholic Church, such as within the Anglican Communion. The term, first used in the 12th or 13th century, distinguishes the mendi ...

in the Franciscan Order

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent Religious institute, religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor bei ...

in either Paris or Oxford, following the example of scholarly English Franciscans such as Grosseteste and Marsh

In ecology, a marsh is a wetland that is dominated by herbaceous plants rather than by woody plants.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p More in genera ...

. After 1260, Bacon's activities were restricted by a statute prohibiting the friars of his order from publishing books or pamphlets without prior approval. He was likely kept at constant menial tasks to limit his time for contemplation and came to view his treatment as an enforced absence from scholarly life.

By the mid-1260s, he was undertaking a search for patrons who could secure permission and funding for his return to Oxford. For a time, Bacon was finally able to get around his superiors' interference through his acquaintance with Guy de Foulques, bishop of Narbonne, cardinal of Sabina, and the papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the Pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title '' legatus'') is a personal representative of the Pope to foreign nations, to some other part of the Catho ...

who negotiated between England's royal and baronial factions.

In 1263 or 1264, a message garbled by Bacon's messenger, Raymond of Laon, led Guy to believe that Bacon had already completed a summary of the sciences. In fact, he had no money to research, let alone copy, such a work and attempts to secure financing from his family were thwarted by the Second Barons' War. However, in 1265, Guy was summoned to a conclave at Perugia

Perugia ( , ; ; ) is the capital city of Umbria in central Italy, crossed by the River Tiber. The city is located about north of Rome and southeast of Florence. It covers a high hilltop and part of the valleys around the area. It has 162,467 ...

that elected him . William Benecor, who had previously been the courier between Henry III and the pope, now carried the correspondence between Bacon and Clement. Clement's reply of 22 June 1266 commissioned "writings and remedies for current conditions", instructing Bacon not to violate any standing "prohibitions" of his order but to carry out his task in utmost secrecy.

While faculties of the time were largely limited to addressing disputes on the known texts of Aristotle, Clement's patronage permitted Bacon to engage in a wide-ranging consideration of the state of knowledge in his era. In 1267 or '68, Bacon sent the Pope his ', which presented his views on how to incorporate Aristotelian logic

In logic and formal semantics, term logic, also known as traditional logic, syllogistic logic or Aristotelian logic, is a loose name for an approach to formal logic that began with Aristotle and was developed further in ancient history mostly b ...

and science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

into a new theology, supporting Grosseteste's text-based approach against the "sentence method" then fashionable.

Bacon also sent his ', ', ', an optical lens, and possibly other works on alchemy

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

and astrology

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions ...

. The entire process has been called "one of the most remarkable single efforts of literary productivity", with Bacon composing referenced works of around a million words in about a year.

Pope Clement died in 1268 and Bacon lost his protector. The Condemnations of 1277 banned the teaching of certain philosophical doctrines, including deterministic astrology. Some time within the next two years, Bacon was apparently imprisoned or placed under house arrest

House arrest (also called home confinement, or nowadays electronic monitoring) is a legal measure where a person is required to remain at their residence under supervision, typically as an alternative to imprisonment. The person is confined b ...

. This was traditionally ascribed to Franciscan Minister General Jerome of Ascoli, probably acting on behalf of the many clergy, monks, and educators attacked by Bacon's 1271 '.

Modern scholarship, however, notes that the first reference to Bacon's "imprisonment" dates from eighty years after his death on the charge of unspecified "suspected novelties" and finds it less than credible. Contemporary scholars who do accept Bacon's imprisonment typically associate it with Bacon's "attraction to contemporary prophesies", his sympathies for "the radical 'poverty' wing of the Franciscans", interest in certain astrological doctrines, or generally combative personality rather than from "any scientific novelties which he may have proposed".

Sometime after 1278, Bacon returned to the Franciscan House at Oxford, where he continued his studies and is presumed to have spent most of the remainder of his life. His last dateable writing—the '—was completed in 1292. He seems to have died shortly afterwards and been buried at Oxford.

Works

Medieval European philosophy often relied on appeals to the authority of

Medieval European philosophy often relied on appeals to the authority of Church Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical peri ...

such as St Augustine, and on works by Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

and Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

only known at second hand or through Latin translations. By the 13th century, new works and better versions – in Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

or in new Latin translations from the Arabic – began to trickle north from Muslim Spain

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

. In Roger Bacon's writings, he upholds Aristotle's calls for the collection of facts before deducing scientific truths, against the practices of his contemporaries, arguing that "thence cometh quiet to the mind".

Bacon also called for reform with regard to theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

. He argued that, rather than training to debate minor philosophical distinctions, theologians should focus their attention primarily on the Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

itself, learning the languages of its original sources thoroughly. He was fluent in several of these languages and was able to note and bemoan several corruptions of scripture, and of the works of the Greek philosophers that had been mistranslated or misinterpreted by scholars working in Latin. He also argued for the education of theologians in science ("natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

") and its addition to the medieval curriculum.

''Opus Majus''

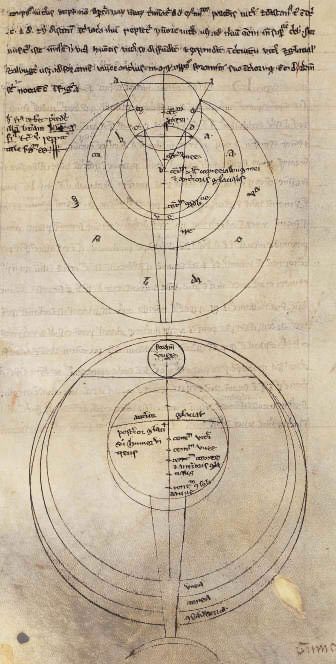

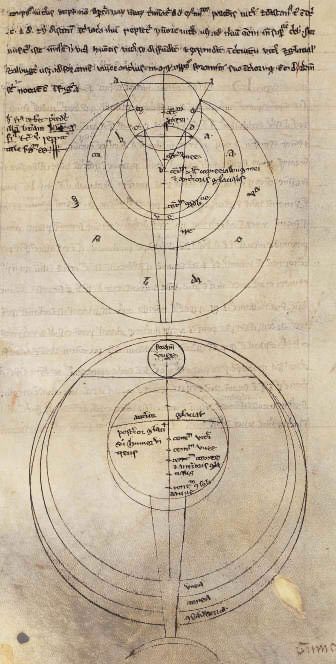

Bacon's 1267 ''Greater Work'', the ', contains treatments of

Bacon's 1267 ''Greater Work'', the ', contains treatments of mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of optical instruments, instruments that use or Photodetector, detect it. Optics usually describes t ...

, alchemy

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

, and astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

, including theories on the positions and sizes of the celestial bodies

An astronomical object, celestial object, stellar object or heavenly body is a naturally occurring physical entity, association, or structure that exists within the observable universe. In astronomy, the terms ''object'' and ''body'' are of ...

. It is divided into seven sections: "The Four General Causes of Human Ignorance" ('), & (1900)Vol. III

Vol. III

Vol. III

medieval university

A medieval university was a corporation organized during the Middle Ages for the purposes of higher education. The first Western European institutions generally considered to be universities were established in present-day Italy, including the K ...

curriculum and the establishment of a kind of library or encyclopedia, bringing in experts to compose a collection of definitive texts on these subjects. The new subjects were to be "perspective" (i.e., optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of optical instruments, instruments that use or Photodetector, detect it. Optics usually describes t ...

), "astronomy" (inclusive of astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

proper, astrology

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions ...

, and the geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

necessary to use them), "weights" (likely some treatment of mechanics

Mechanics () is the area of physics concerned with the relationships between force, matter, and motion among Physical object, physical objects. Forces applied to objects may result in Displacement (vector), displacements, which are changes of ...

but this section of the ' has been lost), alchemy

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

, agriculture

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created ...

(inclusive of botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

and zoology

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

), medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

, and "experiment

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome occurs whe ...

al science", a philosophy of science

Philosophy of science is the branch of philosophy concerned with the foundations, methods, and implications of science. Amongst its central questions are the difference between science and non-science, the reliability of scientific theories, ...

that would guide the others. The section on geography was allegedly originally ornamented with a map

A map is a symbolic depiction of interrelationships, commonly spatial, between things within a space. A map may be annotated with text and graphics. Like any graphic, a map may be fixed to paper or other durable media, or may be displayed on ...

based on ancient and Arabic computations of longitude and latitude, but has since been lost. His (mistaken) arguments supporting the idea that dry land formed the larger proportion of the globe were apparently similar to those which later guided Columbus.

In this work Bacon criticises his contemporaries Alexander of Hales and Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus ( 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great, Albert of Swabia, Albert von Bollstadt, or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop, considered one of the great ...

, who were held in high repute despite having only acquired their knowledge of Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

at second hand during their preaching careers. Albert was received at Paris as an authority equal to Aristotle, Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( – 22 June 1037), commonly known in the West as Avicenna ( ), was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian peoples, Iranian ...

and Averroes

Ibn Rushd (14 April 112611 December 1198), archaically Latinization of names, Latinized as Averroes, was an Arab Muslim polymath and Faqīh, jurist from Al-Andalus who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astron ...

, a situation Bacon decried: "never in the world adsuch monstrosity occurred before."

In Part I of the ''Opus Majus'' Bacon recognises some philosophers as the ''Sapientes'', or gifted few, and saw their knowledge in philosophy and theology as superior to the ''vulgus philosophantium'', or common herd of philosophers. He held Islamic thinkers between 1210 and 1265 in especially high regard calling them "both philosophers and sacred writers" and defended the integration of philosophy from apostate philosopher of the Islamic world into Christian learning.Calendrical reform

In Part IV of the ', Bacon proposed a calendrical reform similar to the latersystem

A system is a group of interacting or interrelated elements that act according to a set of rules to form a unified whole. A system, surrounded and influenced by its open system (systems theory), environment, is described by its boundaries, str ...

introduced in 1582 under Pope Gregory XIII

Pope Gregory XIII (, , born Ugo Boncompagni; 7 January 1502 – 10 April 1585) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 May 1572 to his death in April 1585. He is best known for commissioning and being the namesake ...

. Drawing on ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

and medieval Islamic astronomy recently introduced to western Europe via Spain, Bacon continued the work of Robert Grosseteste

Robert Grosseteste ( ; ; 8 or 9 October 1253), also known as Robert Greathead or Robert of Lincoln, was an Kingdom of England, English statesman, scholasticism, scholastic philosopher, theologian, scientist and Bishop of Lincoln. He was born of ...

and criticised the then-current Julian calendar

The Julian calendar is a solar calendar of 365 days in every year with an additional leap day every fourth year (without exception). The Julian calendar is still used as a religious calendar in parts of the Eastern Orthodox Church and in parts ...

as "intolerable, horrible, and laughable".

It had become apparent that Eudoxus and Sosigenes's assumption of a year of 365¼ days was, over the course of centuries, too inexact. Bacon charged that this meant the computation of Easter had shifted forward by 9 days since the First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea ( ; ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I. The Council of Nicaea met from May until the end of July 325.

This ec ...

in 325. His proposal to drop one day every 125 years and to cease the observance of fixed equinox

A solar equinox is a moment in time when the Sun appears directly above the equator, rather than to its north or south. On the day of the equinox, the Sun appears to rise directly east and set directly west. This occurs twice each year, arou ...

es and solstice

A solstice is the time when the Sun reaches its most northerly or southerly sun path, excursion relative to the celestial equator on the celestial sphere. Two solstices occur annually, around 20–22 June and 20–22 December. In many countries ...

s was not acted upon following the death of Pope Clement IV in 1268. The eventual Gregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It went into effect in October 1582 following the papal bull issued by Pope Gregory XIII, which introduced it as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian cale ...

drops one day from the first three centuries in each set of 400 years.

Optics

In Part V of the ', Bacon discusses physiology of eyesight and the anatomy of theeye

An eye is a sensory organ that allows an organism to perceive visual information. It detects light and converts it into electro-chemical impulses in neurons (neurones). It is part of an organism's visual system.

In higher organisms, the ey ...

and the brain

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

, considering light

Light, visible light, or visible radiation is electromagnetic radiation that can be visual perception, perceived by the human eye. Visible light spans the visible spectrum and is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400– ...

, distance, position, and size, direct and reflected

Reflection is the change in direction of a wavefront at an interface between two different media so that the wavefront returns into the medium from which it originated. Common examples include the reflection of light, sound and water waves. The ...

vision, refraction

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one transmission medium, medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium. Refraction of light is the most commo ...

, mirror

A mirror, also known as a looking glass, is an object that Reflection (physics), reflects an image. Light that bounces off a mirror forms an image of whatever is in front of it, which is then focused through the lens of the eye or a camera ...

s, and lenses

A lens is a transmissive optical device that focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements''), ...

. His treatment was primarily oriented by the Latin translation of Alhazen

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham ( Latinized as Alhazen; ; full name ; ) was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the princ ...

's ''Book of Optics

The ''Book of Optics'' (; or ''Perspectiva''; ) is a seven-volume treatise on optics and other fields of study composed by the medieval Arab scholar Ibn al-Haytham, known in the West as Alhazen or Alhacen (965–c. 1040 AD).

The ''Book ...

''. He also draws heavily on Eugene of Palermo's Latin translation of the Arabic translation of Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

's ''Optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of optical instruments, instruments that use or Photodetector, detect it. Optics usually describes t ...

''; on Robert Grosseteste

Robert Grosseteste ( ; ; 8 or 9 October 1253), also known as Robert Greathead or Robert of Lincoln, was an Kingdom of England, English statesman, scholasticism, scholastic philosopher, theologian, scientist and Bishop of Lincoln. He was born of ...

's work based on Al-Kindi's ''Optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of optical instruments, instruments that use or Photodetector, detect it. Optics usually describes t ...

''; and, through Alhazen (Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham (Latinization of names, Latinized as Alhazen; ; full name ; ) was a medieval Mathematics in medieval Islam, mathematician, Astronomy in the medieval Islamic world, astronomer, and Physics in the medieval Islamic world, p ...

), on Ibn Sahl's work on dioptrics.

Gunpowder

A passage in the ' and another in the ' are usually taken as the first European descriptions of a mixture containing the essential ingredients of

A passage in the ' and another in the ' are usually taken as the first European descriptions of a mixture containing the essential ingredients of gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

. Partington

Partington is a town and civil parish in the Metropolitan Borough of Trafford, Greater Manchester, England. It is sited south-west of Manchester city centre. Within the boundaries of the Historic counties of England, historic county of Ches ...

and others have come to the conclusion that Bacon most likely witnessed at least one demonstration of Chinese firecracker

A firecracker (cracker, noise maker, banger) is a small explosive device primarily designed to produce a large amount of noise, especially in the form of a loud bang, usually for celebration or entertainment; any visual effect is incidental to ...

s, possibly obtained by Franciscans—including Bacon's friend William of Rubruck—who visited the Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire was the List of largest empires, largest contiguous empire in human history, history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Euro ...

during this period. The most telling passage reads:

We have an example of these things (that act on the senses) in he sound and fire ofthat children's toy which is made in many iverseparts of the world; i.e. a device no bigger than one's thumb. From the violence of that salt called saltpetre ogether with sulphur and willow charcoal, combined into a powderso horrible a sound is made by the bursting of a thing so small, no more than a bit of parchment ontaining it that we find he ear assaulted by a noiseexceeding the roar of strong thunder, and a flash brighter than the most brilliant lightning.At the beginning of the 20th century, Henry William Lovett Hime of the

Royal Artillery

The Royal Regiment of Artillery, commonly referred to as the Royal Artillery (RA) and colloquially known as "The Gunners", is one of two regiments that make up the artillery arm of the British Army. The Royal Regiment of Artillery comprises t ...

published the theory that Bacon's ' contained a cryptogram

A cryptogram is a type of puzzle that consists of a short piece of encrypted text. Generally the cipher used to encrypt the text is simple enough that the cryptogram can be solved by hand. Substitution ciphers where each letter is replaced by ...

giving a recipe for the gunpowder he witnessed. The theory was criticised by Thorndike in a 1915 letter to ''Science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

'' and several books, a position joined by Muir, John Maxson Stillman, Steele, and Sarton. Needham et al. concurred with these earlier critics that the additional passage did not originate with Bacon and further showed that the proportions supposedly deciphered (a 7:5:5 ratio of saltpetre

Potassium nitrate is a chemical compound with a sharp, salty, bitter taste and the chemical formula . It is a potassium salt of nitric acid. This salt consists of potassium cations and nitrate anions , and is therefore an alkali metal nitrate ...

to charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, ca ...

to sulphur) as not even useful for firecrackers, burning slowly with a great deal of smoke and failing to ignite inside a gun barrel. The ~41% nitrate

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion with the chemical formula . salt (chemistry), Salts containing this ion are called nitrates. Nitrates are common components of fertilizers and explosives. Almost all inorganic nitrates are solubility, soluble in wa ...

content is too low to have explosive properties.

''Secret of Secrets''

Bacon attributed the ''Secret of Secrets'' ('), the Islamic "Mirror of Princes" (), toAristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

, thinking that he had composed it for Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

. Bacon produced an edition of Philip of Tripoli's Latin translation, complete with his own introduction and notes; and his writings of the 1260s and 1270s cite it far more than his contemporaries did. This led Easton and others, including Robert Steele, to argue that the text spurred Bacon's own transformation into an experimentalist. (Bacon never described such a decisive impact himself.) The dating of Bacon's edition of the ''Secret of Secrets'' is a key piece of evidence in the debate, with those arguing for a greater impact giving it an earlier date; but it certainly influenced the elder Bacon's conception of the political aspects of his work in the sciences.

Alchemy

Bacon has been credited with a number of alchemical texts.

The ''Letter on the Secret Workings of Art and Nature and on the Vanity of Magic'' ('), also known as ''On the Wonderful Powers of Art and Nature'' ('), a likely-forged letter to an unknown "William of Paris," dismisses practices such as

Bacon has been credited with a number of alchemical texts.

The ''Letter on the Secret Workings of Art and Nature and on the Vanity of Magic'' ('), also known as ''On the Wonderful Powers of Art and Nature'' ('), a likely-forged letter to an unknown "William of Paris," dismisses practices such as necromancy

Necromancy () is the practice of Magic (paranormal), magic involving communication with the Death, dead by Evocation, summoning their spirits as Ghost, apparitions or Vision (spirituality), visions for the purpose of divination; imparting the ...

but contains most of the alchemical formulae attributed to Bacon, including one for a philosopher's stone

The philosopher's stone is a mythic alchemical substance capable of turning base metals such as mercury into gold or silver; it was also known as "the tincture" and "the powder". Alchemists additionally believed that it could be used to mak ...

and another possibly for gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

. It also includes several passages about hypothetical flying machines and submarines

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or info ...

, attributing their first use to Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

. ''On the Vanity of Magic'' or ''The Nullity of Magic'' is a debunking of esoteric claims in Bacon's time, showing that they could be explained by natural phenomena.

He wrote on the medicine of Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (; September 129 – AD), often Anglicization, anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Ancient Rome, Roman and Greeks, Greek physician, surgeon, and Philosophy, philosopher. Considered to be one o ...

, referring to the translations of Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( – 22 June 1037), commonly known in the West as Avicenna ( ), was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian peoples, Iranian ...

. He believed that the medicine of Galen belonged to an ancient tradition passed through Chaldea

Chaldea () refers to a region probably located in the marshy land of southern Mesopotamia. It is mentioned, with varying meaning, in Neo-Assyrian cuneiform, the Hebrew Bible, and in classical Greek texts. The Hebrew Bible uses the term (''Ka� ...

ns, Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

and Arab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

s. Although he provided a negative image of Hermes Trismegistus

Hermes Trismegistus (from , "Hermes the Thrice-Greatest") is a legendary Hellenistic period figure that originated as a syncretic combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth.A survey of the literary and archaeological eviden ...

, his work was influenced by the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

Hermetic thought. Bacon's endorsement of Hermetic philosophy is evident, as his citations of the alchemical literature known as the Secretum Secretorum made several appearances in the Opus Majus. The Secretum Secretorum contains knowledge about the Hermetic Emerald Tablet, which was an integral component of alchemy, thus proving that Bacon's version of alchemy was much less secular, and much more spiritual than once interpreted. The importance of Hermetic philosophy in Bacon's work is also evident through his citations of classic Hermetic literature such as the Corpus Hermeticum. Bacon's citation of the Corpus Hermeticum, which consists of a dialogue between Hermes and the pagan deity Asclepius

Asclepius (; ''Asklēpiós'' ; ) is a hero and god of medicine in ancient Religion in ancient Greece, Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology. He is the son of Apollo and Coronis (lover of Apollo), Coronis, or Arsinoe (Greek myth), Ars ...

, proves that Bacon's ideas were much more in line with the spiritual aspects of alchemy rather than the scientific aspects. However, this is somewhat paradoxical as what Bacon was specifically trying to prove in the Opus Majus and subsequent works, was that spirituality and science were the same entity. Bacon believed that by using science, certain aspects of spirituality such as the attainment of "Sapientia" or "Divine Wisdom" could be logically explained using tangible evidence. Bacon's Opus Majus was first and foremost, a compendium of sciences which he believed would facilitate the first step towards "Sapientia". Bacon placed considerable emphasis on alchemy and even went so far as to state that alchemy was the most important science. The reason why Bacon kept the topic of alchemy vague for the most part, is due to the need for secrecy about esoteric topics in England at the time as well as his dedication to remaining in line with the alchemical tradition of speaking in symbols and metaphors.

Linguistics

Bacon's early linguistic and logical works are the ''Overview of Grammar'' ('' Summa Grammatica''), ', and the ' or '. These are mature but essentially conventional presentations of Oxford and Paris's terminist and pre- modist logic and grammar. His later work in linguistics is much more idiosyncratic, using terminology and addressing questions unique in his era.. In his ''Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

'' and '' Hebrew Grammars'' (' and '), in his work "On the Usefulness of Grammar" (Book III of the '), and in his ''Compendium of the Study of Philosophy'', Bacon stresses the need for scholars to know several languages. Europe's vernacular languages are not ignored—he considers them useful for practical purposes such as trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

Traders generally negotiate through a medium of cr ...

, proselytism

Proselytism () is the policy of attempting to convert people's religious or political beliefs. Carrying out attempts to instill beliefs can be called proselytization.

Proselytism is illegal in some countries. Some draw distinctions between Chris ...

, and administration

Administration may refer to:

Management of organizations

* Management, the act of directing people towards accomplishing a goal: the process of dealing with or controlling things or people.

** Administrative assistant, traditionally known as a se ...

—but Bacon is mostly interested in his era's languages of science and religion: Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

, Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

and Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

..

Bacon is less interested in a full practical mastery of the other languages than on a theoretical understanding of their grammatical rules, ensuring that a Latin reader will not misunderstand passages' original meaning. For this reason, his treatments of Greek and Hebrew grammar are not isolated works on their topic but contrastive grammars treating the aspects which influenced Latin or which were required for properly understanding Latin texts.. He pointedly states, "I want to describe Greek grammar for the benefit of Latin speakers". It is likely only this limited sense which was intended by Bacon's boast that he could teach an interested pupil a new language within three days.

Passages in the ''Overview'' and the Greek grammar have been taken as an early exposition of a universal grammar underlying all human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

language

Language is a structured system of communication that consists of grammar and vocabulary. It is the primary means by which humans convey meaning, both in spoken and signed language, signed forms, and may also be conveyed through writing syste ...

s.. The Greek grammar contains the tersest and most famous exposition:

However, Bacon's lack of interest in studying a literal grammar

In linguistics, grammar is the set of rules for how a natural language is structured, as demonstrated by its speakers or writers. Grammar rules may concern the use of clauses, phrases, and words. The term may also refer to the study of such rul ...

underlying the languages known to him and his numerous works on linguistics and comparative linguistics has prompted Hovdhaugen to question the usual literal translation of Bacon's ' in such passages. She notes the ambiguity in the Latin term, which could refer variously to the structure of language, to its description, and to the science underlying such descriptions: i.e., linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of language. The areas of linguistic analysis are syntax (rules governing the structure of sentences), semantics (meaning), Morphology (linguistics), morphology (structure of words), phonetics (speech sounds ...

..

Other works

Bacon states that his ''Lesser Work'' (') and ''Third Work'' (') were originally intended as summaries of the ' in case it was lost in transit. Easton's review of the texts suggests that they became separate works over the course of the laborious process of creating a fair copy of the ', whose half-million words were copied by hand and apparently greatly revised at least once.

Other works by Bacon include his "Tract on the Multiplication of Species" ('), "On Burning Lenses" ('), the ' and ', the "Compendium of the Study of Philosophy" and "of Theology" (' and '), and his ''Computus''. The "Compendium of the Study of Theology", presumably written in the last years of his life, was an anticlimax: adding nothing new, it is principally devoted to the concerns of the 1260s.

Bacon states that his ''Lesser Work'' (') and ''Third Work'' (') were originally intended as summaries of the ' in case it was lost in transit. Easton's review of the texts suggests that they became separate works over the course of the laborious process of creating a fair copy of the ', whose half-million words were copied by hand and apparently greatly revised at least once.

Other works by Bacon include his "Tract on the Multiplication of Species" ('), "On Burning Lenses" ('), the ' and ', the "Compendium of the Study of Philosophy" and "of Theology" (' and '), and his ''Computus''. The "Compendium of the Study of Theology", presumably written in the last years of his life, was an anticlimax: adding nothing new, it is principally devoted to the concerns of the 1260s.

Apocrypha

'' The Mirror of Alchimy'' ('), a short treatise on the origin and composition of metals, is traditionally credited to Bacon. It espouses the Arabian theory of mercury and sulphur forming the other metals, with vague allusions to transmutation. Stillman opined that "there is nothing in it that is characteristic of Roger Bacon's style or ideas, nor that distinguishes it from many unimportant alchemical lucubrations of anonymous writers of the thirteenth to the sixteenth centuries", and Muir and Lippmann also considered it a pseudepigraph. The cryptic Voynich manuscript has been attributed to Bacon by various sources, including by its first recorded owner, buthistorians of science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal. Protoscience, early sciences, and natural philosophies such as al ...

Lynn Thorndike

Lynn Thorndike (24 July 1882, in Lynn, Massachusetts, US – 28 December 1965, New York City) was an American historian of History of science in the Middle Ages, medieval science and alchemy. He was the son of a clergyman, Edward R. Thorndike, an ...

and George Sarton dismissed these claims as unsupported, and the vellum

Vellum is prepared animal skin or membrane, typically used as writing material. It is often distinguished from parchment, either by being made from calfskin (rather than the skin of other animals), or simply by being of a higher quality. Vellu ...

of the manuscript has since been dated to the 15th century.

Legacy

Bacon was largely ignored by his contemporaries in favour of other scholars such as

Bacon was largely ignored by his contemporaries in favour of other scholars such as Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus ( 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great, Albert of Swabia, Albert von Bollstadt, or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop, considered one of the great ...

, Bonaventure

Bonaventure ( ; ; ; born Giovanni di Fidanza; 1221 – 15 July 1274) was an Italian Catholic Franciscan bishop, Cardinal (Catholic Church), cardinal, Scholasticism, scholastic theologian and philosopher.

The seventh Minister General ( ...

, and Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

, although his works were studied by Bonaventure, John Pecham, and Peter of Limoges, through whom he may have influenced Raymond Lull. He was also partially responsible for the addition of optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of optical instruments, instruments that use or Photodetector, detect it. Optics usually describes t ...

(') to the medieval university

A medieval university was a corporation organized during the Middle Ages for the purposes of higher education. The first Western European institutions generally considered to be universities were established in present-day Italy, including the K ...

curriculum

In education, a curriculum (; : curriculums or curricula ) is the totality of student experiences that occur in an educational process. The term often refers specifically to a planned sequence of instruction, or to a view of the student's experi ...

.

By the early modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

, the English considered him the epitome of a wise and subtle possessor of forbidden knowledge, a Faust

Faust ( , ) is the protagonist of a classic German folklore, German legend based on the historical Johann Georg Faust (). The erudite Faust is highly successful yet dissatisfied with his life, which leads him to make a deal with the Devil at a ...

-like magician who had tricked the devil

A devil is the mythical personification of evil as it is conceived in various cultures and religious traditions. It is seen as the objectification of a hostile and destructive force. Jeffrey Burton Russell states that the different conce ...

and so was able to go to heaven

Heaven, or the Heavens, is a common Religious cosmology, religious cosmological or supernatural place where beings such as deity, deities, angels, souls, saints, or Veneration of the dead, venerated ancestors are said to originate, be throne, ...

. Of these legends, one of the most prominent was that he created a talking brazen head which could answer any question. The story appears in the anonymous 16th-century account of ''The Famous Historie of Fryer Bacon'', in which Bacon speaks with a demon but causes the head to speak by "the continuall fume of the six hottest Simples",. testing his theory that speech is caused by "an effusion of vapors".

Around 1589, Robert Greene adapted the story for the stage as '' The Honorable Historie of Frier Bacon and Frier Bongay'', one of the most successful Elizabethan comedies. As late as the 1640s, Thomas Browne

Sir Thomas Browne ( "brown"; 19 October 160519 October 1682) was an English polymath and author of varied works which reveal his wide learning in diverse fields including science and medicine, religion and the esoteric. His writings display a d ...

was still complaining that "Every ear is filled with the story of Frier Bacon, that made a brazen head to speak these words, ''Time is''". Browne, '' Pseud. Epid.''Bk. VII, Ch. xvii, §7.

Greene's Bacon spent seven years creating a brass head that would speak "strange and uncouth aphorisms" to enable him to encircle

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

with a wall of brass that would make it impossible to conquer.

Unlike his source material, Greene does not cause his head to operate by natural forces but by " nigromantic charms" and "the enchanting forces of the devil

A devil is the mythical personification of evil as it is conceived in various cultures and religious traditions. It is seen as the objectification of a hostile and destructive force. Jeffrey Burton Russell states that the different conce ...

": i.e., by entrapping a dead spirit or hobgoblin

A hobgoblin is a household spirit, appearing in English folklore, once considered helpful, but which since the spread of Christianity has often been considered mischievous. Shakespeare identifies the character of Puck in his '' A Midsummer Nigh ...

. Bacon collapses, exhausted, just before his device comes to life and announces "Time is", "Time was", and "Time is Past" before being destroyed in spectacular fashion: the stage direction

In theatre, blocking is the precise staging of actors to facilitate the performance of a play, ballet, film or opera. Historically, the expectations of staging/blocking have changed substantially over time in Western theater. Prior to the movem ...

instructs that "''a lightening flasheth forth, and a hand appears that breaketh down the Head with a hammer''".

A necromantic head was ascribed to Pope Sylvester II as early as the 1120s, but Browne considered the legend to be a misunderstanding of a passage in Peter the Good's '' Precious Pearl'' where the negligent alchemist misses the birth of his creation and loses it forever. The story may also preserve the work by Bacon and his contemporaries to construct clockwork armillary spheres. Bacon had praised a "self-activated working model of the heavens" as "the greatest of all things which have been devised".

As early as the 16th century, natural philosophers

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the developme ...

such as Bruno

Bruno may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Bruno (name), including lists of people and fictional characters with either the given name or surname

* Bruno, Duke of Saxony (died 880)

* Bruno the Great (925–965), Archbishop of Cologn ...

, Dee and Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...

were attempting to rehabilitate Bacon's reputation and to portray him as a scientific pioneer who had avoided the petty bickering of his contemporaries to attempt a rational understanding of nature. By the 19th century, commenters following Whewell considered that "Bacon ... was not appreciated in his age because he was so completely in advance of it; he is a 16th- or 17th-century philosopher, whose lot has been by some accident cast in the 13th century". His assertions in the ' that "theories supplied by reason should be verified by sensory data, aided by instruments, and corroborated by trustworthy witnesses" were (and still are) considered "one of the first important formulations of the scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has been referred to while doing science since at least the 17th century. Historically, it was developed through the centuries from the ancient and ...

on record".

This idea that Bacon was a modern experimental scientist reflected two views of the period: that the principal form of scientific activity is experimentation and that 13th-century Europe still represented the " Dark Ages". This view, which is still reflected in some 21st-century popular science

Popular science (also called pop-science or popsci) is an interpretation of science intended for a general audience. While science journalism focuses on recent scientific developments, popular science is more broad ranging. It may be written ...

books, portrays Bacon as an advocate of modern experimental science who emerged as a solitary genius in an age hostile to his ideas. Based on Bacon's apocrypha

Apocrypha () are biblical or related writings not forming part of the accepted canon of scripture, some of which might be of doubtful authorship or authenticity. In Christianity, the word ''apocryphal'' (ἀπόκρυφος) was first applied to ...

, he is also portrayed as a visionary who predicted the invention of the submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

, aircraft

An aircraft ( aircraft) is a vehicle that is able to flight, fly by gaining support from the Atmosphere of Earth, air. It counters the force of gravity by using either Buoyancy, static lift or the Lift (force), dynamic lift of an airfoil, or, i ...

, and automobile

A car, or an automobile, is a motor vehicle with wheels. Most definitions of cars state that they run primarily on roads, Car seat, seat one to eight people, have four wheels, and mainly transport private transport#Personal transport, peopl ...

. Consistent with this view of Bacon as a man ahead of his time, H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells (21 September 1866 – 13 August 1946) was an English writer, prolific in many genres. He wrote more than fifty novels and dozens of short stories. His non-fiction output included works of social commentary, politics, hist ...

's '' Outline of History'' attributes this prescient passage to him:Machines for navigating are possible without rowers, so that great ships suited to river or ocean, guided by one man, may be borne with greater speed than if they were full of men. Likewise, cars may be made so that without a draught animal they may be moved ''cum impetu inaestimabili'', as we deem the scythed chariots to have been from which antiquity fought. And flying machines are possible, so that a man may sit in the middle turning some device by which artificial wings may beat the air in the manner of a flying bird.Wells, H. G., ''The Outline of History'', Vol. 2, Ch. 33, §6, p. 638 (New York 1971) ("updated" by Raymond Postgate and G. P. Wells).However, in the course of the 20th century, Husserl,

/ref>

Heidegger

Martin Heidegger (; 26 September 1889 – 26 May 1976) was a German philosopher known for contributions to phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. His work covers a range of topics including metaphysics, art, and language.

In April ...

and others emphasised the importance to the modern science of Cartesian and Galilean projections of mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

over sensory perceptions of nature; Heidegger, in particular, noted the lack of such an understanding in Bacon's works. Although Crombie, Kuhn and continued to argue for Bacon's importance to the development of "qualitative" areas of modern science, Duhem, Thorndike, Carton

A carton is a box or container usually made of liquid packaging board, paperboard and sometimes of corrugated fiberboard.

Many types of cartons are used in packaging. Sometimes a carton is also called a box.

Types of cartons

Folding cartons

...

and Koyré emphasised the essentially medieval nature of Bacon's '.

Research also established that Bacon was not as isolated—and probably not as persecuted—as was once thought. Many medieval sources of and influences on Bacon's scientific activity have been identified. In particular, Bacon often mentioned his debt to the work of Robert Grosseteste

Robert Grosseteste ( ; ; 8 or 9 October 1253), also known as Robert Greathead or Robert of Lincoln, was an Kingdom of England, English statesman, scholasticism, scholastic philosopher, theologian, scientist and Bishop of Lincoln. He was born of ...