Rocket 455 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A rocket (from , and so named for its shape)

A rocket (from , and so named for its shape)

In China,

In China,  The

The  The

The  In 1920, Professor

In 1920, Professor  In 1921, the

In 1921, the

Rocket engines employ the principle of jet propulsion. The rocket engines powering rockets come in a great variety of different types; a comprehensive list can be found in the main article,

Rocket engines employ the principle of jet propulsion. The rocket engines powering rockets come in a great variety of different types; a comprehensive list can be found in the main article,

Rocket propellant is mass that is stored, usually in some form of

Rocket propellant is mass that is stored, usually in some form of

The first

The first

Some military weapons use rockets to propel

Some military weapons use rockets to propel

Rockets were used to propel a line to a stricken ship so that a

Rockets were used to propel a line to a stricken ship so that a

When launching a spacecraft to orbit, a "" is a guided, powered turn during ascent phase that causes a rocket's flight path to deviate from a "straight" path. A dogleg is necessary if the desired launch azimuth, to reach a desired orbital inclination, would take the

When launching a spacecraft to orbit, a "" is a guided, powered turn during ascent phase that causes a rocket's flight path to deviate from a "straight" path. A dogleg is necessary if the desired launch azimuth, to reach a desired orbital inclination, would take the

Rocket exhaust generates a significant amount of acoustic energy. As the

Rocket exhaust generates a significant amount of acoustic energy. As the

The

The  In a closed chamber, the pressures are equal in each direction and no acceleration occurs. If an opening is provided in the bottom of the chamber then the pressure is no longer acting on the missing section. This opening permits the exhaust to escape. The remaining pressures give a resultant thrust on the side opposite the opening, and these pressures are what push the rocket along.

The shape of the nozzle is important. Consider a balloon propelled by air coming out of a tapering nozzle. In such a case the combination of air pressure and viscous friction is such that the nozzle does not push the balloon but is ''pulled'' by it. Using a convergent/divergent nozzle gives more force since the exhaust also presses on it as it expands outwards, roughly doubling the total force. If propellant gas is continuously added to the chamber then these pressures can be maintained for as long as propellant remains. Note that in the case of liquid propellant engines, the pumps moving the propellant into the combustion chamber must maintain a pressure larger than the combustion chamber—typically on the order of 100 atmospheres.

As a side effect, these pressures on the rocket also act on the exhaust in the opposite direction and accelerate this exhaust to very high speeds (according to

In a closed chamber, the pressures are equal in each direction and no acceleration occurs. If an opening is provided in the bottom of the chamber then the pressure is no longer acting on the missing section. This opening permits the exhaust to escape. The remaining pressures give a resultant thrust on the side opposite the opening, and these pressures are what push the rocket along.

The shape of the nozzle is important. Consider a balloon propelled by air coming out of a tapering nozzle. In such a case the combination of air pressure and viscous friction is such that the nozzle does not push the balloon but is ''pulled'' by it. Using a convergent/divergent nozzle gives more force since the exhaust also presses on it as it expands outwards, roughly doubling the total force. If propellant gas is continuously added to the chamber then these pressures can be maintained for as long as propellant remains. Note that in the case of liquid propellant engines, the pumps moving the propellant into the combustion chamber must maintain a pressure larger than the combustion chamber—typically on the order of 100 atmospheres.

As a side effect, these pressures on the rocket also act on the exhaust in the opposite direction and accelerate this exhaust to very high speeds (according to

The general study of the

The general study of the

A typical rocket engine can handle a significant fraction of its own mass in propellant each second, with the propellant leaving the nozzle at several kilometres per second. This means that the

A typical rocket engine can handle a significant fraction of its own mass in propellant each second, with the propellant leaving the nozzle at several kilometres per second. This means that the

The

The

Almost all of a launch vehicle's mass consists of propellant. Mass ratio is, for any 'burn', the ratio between the rocket's initial mass and its final mass. Everything else being equal, a high mass ratio is desirable for good performance, since it indicates that the rocket is lightweight and hence performs better, for essentially the same reasons that low weight is desirable in sports cars.

Rockets as a group have the highest

Almost all of a launch vehicle's mass consists of propellant. Mass ratio is, for any 'burn', the ratio between the rocket's initial mass and its final mass. Everything else being equal, a high mass ratio is desirable for good performance, since it indicates that the rocket is lightweight and hence performs better, for essentially the same reasons that low weight is desirable in sports cars.

Rockets as a group have the highest

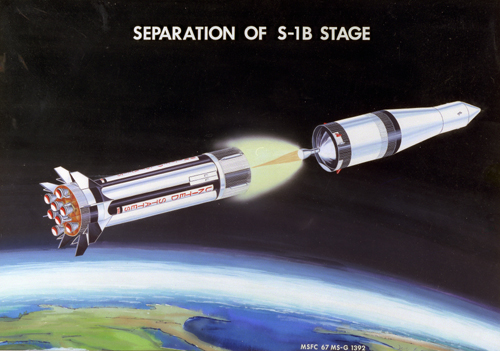

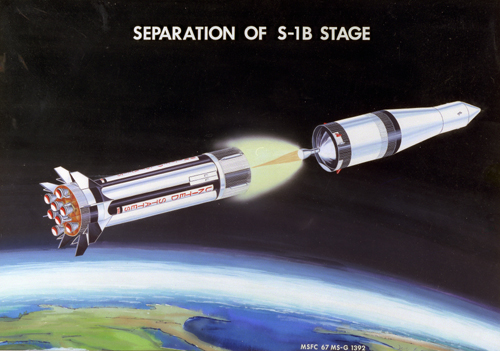

Thus far, the required velocity (delta-v) to achieve orbit has been unattained by any single rocket because the

Thus far, the required velocity (delta-v) to achieve orbit has been unattained by any single rocket because the

The energy density of a typical rocket propellant is often around one-third that of conventional hydrocarbon fuels; the bulk of the mass is (often relatively inexpensive) oxidizer. Nevertheless, at take-off the rocket has a great deal of energy in the fuel and oxidizer stored within the vehicle. It is of course desirable that as much of the energy of the propellant end up as kinetic or

The energy density of a typical rocket propellant is often around one-third that of conventional hydrocarbon fuels; the bulk of the mass is (often relatively inexpensive) oxidizer. Nevertheless, at take-off the rocket has a great deal of energy in the fuel and oxidizer stored within the vehicle. It is of course desirable that as much of the energy of the propellant end up as kinetic or  From these principles it can be shown that the propulsive efficiency for a rocket moving at speed with an exhaust velocity is:

And the overall (instantaneous) energy efficiency is:

For example, from the equation, with an of 0.7, a rocket flying at Mach 0.85 (which most aircraft cruise at) with an exhaust velocity of Mach 10, would have a predicted overall energy efficiency of 5.9%, whereas a conventional, modern, air-breathing jet engine achieves closer to 35% efficiency. Thus a rocket would need about 6x more energy; and allowing for the specific energy of rocket propellant being around one third that of conventional air fuel, roughly 18x more mass of propellant would need to be carried for the same journey. This is why rockets are rarely if ever used for general aviation.

Since the energy ultimately comes from fuel, these considerations mean that rockets are mainly useful when a very high speed is required, such as

From these principles it can be shown that the propulsive efficiency for a rocket moving at speed with an exhaust velocity is:

And the overall (instantaneous) energy efficiency is:

For example, from the equation, with an of 0.7, a rocket flying at Mach 0.85 (which most aircraft cruise at) with an exhaust velocity of Mach 10, would have a predicted overall energy efficiency of 5.9%, whereas a conventional, modern, air-breathing jet engine achieves closer to 35% efficiency. Thus a rocket would need about 6x more energy; and allowing for the specific energy of rocket propellant being around one third that of conventional air fuel, roughly 18x more mass of propellant would need to be carried for the same journey. This is why rockets are rarely if ever used for general aviation.

Since the energy ultimately comes from fuel, these considerations mean that rockets are mainly useful when a very high speed is required, such as

The reliability of rockets, as for all physical systems, is dependent on the quality of engineering design and construction.

Because of the enormous chemical energy in

The reliability of rockets, as for all physical systems, is dependent on the quality of engineering design and construction.

Because of the enormous chemical energy in

by John Walker. September 27, 1993. Most of the takeoff mass of a rocket is normally propellant. However propellant is seldom more than a few times more expensive than gasoline per kilogram (as of 2009 gasoline was about or less), and although substantial amounts are needed, for all but the very cheapest rockets, it turns out that the propellant costs are usually comparatively small, although not completely negligible. With liquid oxygen costing and liquid hydrogen , the

Excerpt online

/ref>:File:LEOonthecheap.pdf, U.S. Air Force Research Report No. AU-ARI-93-8: LEO On The Cheap. Retrieved April 29, 2011. For most rockets except reusable ones (shuttle engines) the engines need not function more than a few minutes, which simplifies design. Extreme performance requirements for rockets reaching orbit correlate with high cost, including intensive quality control to ensure reliability despite the limited safety factors allowable for weight reasons. Components produced in small numbers if not individually machined can prevent amortization of R&D and facility costs over mass production to the degree seen in more pedestrian manufacturing. Amongst liquid-fueled rockets, complexity can be influenced by how much hardware must be lightweight, like pressure-fed engines can have two orders of magnitude lesser part count than pump-fed engines but lead to more weight by needing greater tank pressure, most often used in just small maneuvering thrusters as a consequence. To change the preceding factors for orbital launch vehicles, proposed methods have included mass-producing simple rockets in large quantities or on large scale, or developing reusable launch system, reusable rockets meant to fly very frequently to amortize their up-front expense over many payloads, or reducing rocket performance requirements by constructing a non-rocket spacelaunch system for part of the velocity to orbit (or all of it but with most methods involving some rocket use). The costs of support equipment, range costs and launch pads generally scale up with the size of the rocket, but vary less with launch rate, and so may be considered to be approximately a fixed cost. Rockets in applications other than launch to orbit (such as military rockets and JATO, rocket-assisted take off), commonly not needing comparable performance and sometimes mass-produced, are often relatively inexpensive.

FAA Office of Commercial Space Transportation

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)

National Association of Rocketry (US)

Tripoli Rocketry Association

Asoc. Coheteria Experimental y Modelista de Argentina

United Kingdom Rocketry Association

IMR – German/Austrian/Swiss Rocketry Association

Canadian Association of Rocketry

Indian Space Research Organisation

Information sites * Encyclopedia Astronautica �

Rocket and Missile Alphabetical Index

* Gunter's Space Page �

Complete Rocket and Missile Lists

Relativity Calculator – Learn Tsiolkovsky's rocket equations

Robert Goddard – America's Space Pioneer

{{Authority control Articles containing video clips Rockets and missiles, Chinese inventions Gunpowder Rocket-powered aircraft Rocketry, Space launch vehicles

A rocket (from , and so named for its shape)

A rocket (from , and so named for its shape)vehicle

A vehicle () is a machine designed for self-propulsion, usually to transport people, cargo, or both. The term "vehicle" typically refers to land vehicles such as human-powered land vehicle, human-powered vehicles (e.g. bicycles, tricycles, velo ...

that uses jet propulsion to accelerate

In mechanics, acceleration is the rate of change of the velocity of an object with respect to time. Acceleration is one of several components of kinematics, the study of motion. Accelerations are vector quantities (in that they have magnit ...

without using any surrounding air

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosph ...

. A rocket engine

A rocket engine is a reaction engine, producing thrust in accordance with Newton's third law by ejecting reaction mass rearward, usually a high-speed Jet (fluid), jet of high-temperature gas produced by the combustion of rocket propellants stor ...

produces thrust by reaction

Reaction may refer to a process or to a response to an action, event, or exposure.

Physics and chemistry

*Chemical reaction

*Nuclear reaction

*Reaction (physics), as defined by Newton's third law

* Chain reaction (disambiguation)

Biology and ...

to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely from propellant

A propellant (or propellent) is a mass that is expelled or expanded in such a way as to create a thrust or another motive force in accordance with Newton's third law of motion, and "propel" a vehicle, projectile, or fluid payload. In vehicle ...

carried within the vehicle; therefore a rocket can fly in the vacuum

A vacuum (: vacuums or vacua) is space devoid of matter. The word is derived from the Latin adjective (neuter ) meaning "vacant" or "void". An approximation to such vacuum is a region with a gaseous pressure much less than atmospheric pressur ...

of space. Rockets work more efficiently in a vacuum and incur a loss of thrust due to the opposing pressure of the atmosphere.

Multistage rocket

A multistage rocket or step rocket is a launch vehicle that uses two or more rocket ''stages'', each of which contains its own engines and propellant. A ''tandem'' or ''serial'' stage is mounted on top of another stage; a ''parallel'' stage is ...

s are capable of attaining escape velocity

In celestial mechanics, escape velocity or escape speed is the minimum speed needed for an object to escape from contact with or orbit of a primary body, assuming:

* Ballistic trajectory – no other forces are acting on the object, such as ...

from Earth and therefore can achieve unlimited maximum altitude. Compared with airbreathing engines, rockets are lightweight and powerful and capable of generating large acceleration

In mechanics, acceleration is the Rate (mathematics), rate of change of the velocity of an object with respect to time. Acceleration is one of several components of kinematics, the study of motion. Accelerations are Euclidean vector, vector ...

s. To control their flight, rockets rely on momentum

In Newtonian mechanics, momentum (: momenta or momentums; more specifically linear momentum or translational momentum) is the product of the mass and velocity of an object. It is a vector quantity, possessing a magnitude and a direction. ...

, airfoils

An airfoil (American English) or aerofoil (British English) is a streamlined body that is capable of generating significantly more lift than drag. Wings, sails and propeller blades are examples of airfoils. Foils of similar function designed ...

, auxiliary reaction engines, gimballed thrust

Gimbaled thrust is the system of thrust vectoring used in most rockets, including the Space Shuttle program, Space Shuttle, the Saturn V lunar rockets, and the Falcon 9.

Operation

In a gimbaled thrust system, the engine or just the exhaust nozz ...

, momentum wheels, deflection of the exhaust stream, propellant flow, spin

Spin or spinning most often refers to:

* Spin (physics) or particle spin, a fundamental property of elementary particles

* Spin quantum number, a number which defines the value of a particle's spin

* Spinning (textiles), the creation of yarn or thr ...

, or gravity

In physics, gravity (), also known as gravitation or a gravitational interaction, is a fundamental interaction, a mutual attraction between all massive particles. On Earth, gravity takes a slightly different meaning: the observed force b ...

.

Rockets for military and recreational uses date back to at least 13th-century China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

. Significant scientific, interplanetary and industrial use did not occur until the 20th century, when rocketry was the enabling technology for the Space Age

The Space Age is a period encompassing the activities related to the space race, space exploration, space technology, and the cultural developments influenced by these events, beginning with the launch of Sputnik 1 on October 4, 1957, and co ...

, including setting foot on the Moon. Rockets are now used for fireworks

Fireworks are Explosive, low explosive Pyrotechnics, pyrotechnic devices used for aesthetic and entertainment purposes. They are most commonly used in fireworks displays (also called a fireworks show or pyrotechnics), combining a large numbe ...

, missile

A missile is an airborne ranged weapon capable of self-propelled flight aided usually by a propellant, jet engine or rocket motor.

Historically, 'missile' referred to any projectile that is thrown, shot or propelled towards a target; this ...

s and other weapon

A weapon, arm, or armament is any implement or device that is used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime (e.g., murder), law ...

ry, ejection seat

In aircraft, an ejection seat or ejector seat is a system designed to rescue the aircraft pilot, pilot or other aircrew, crew of an aircraft (usually military) in an emergency. In most designs, the seat is propelled out of the aircraft by an exp ...

s, launch vehicle

A launch vehicle is typically a rocket-powered vehicle designed to carry a payload (a crewed spacecraft or satellites) from Earth's surface or lower atmosphere to outer space. The most common form is the ballistic missile-shaped multistage ...

s for artificial satellite

A satellite or an artificial satellite is an object, typically a spacecraft, placed into orbit around a celestial body. They have a variety of uses, including communication relay, weather forecasting, navigation ( GPS), broadcasting, scienti ...

s, human spaceflight

Human spaceflight (also referred to as manned spaceflight or crewed spaceflight) is spaceflight with a crew or passengers aboard a spacecraft, often with the spacecraft being operated directly by the onboard human crew. Spacecraft can also be ...

, and space exploration

Space exploration is the process of utilizing astronomy and space technology to investigate outer space. While the exploration of space is currently carried out mainly by astronomers with telescopes, its physical exploration is conducted bo ...

.

Chemical rocket

A rocket engine is a reaction engine, producing thrust in accordance with Newton's third law by ejecting reaction mass rearward, usually a high-speed jet of high-temperature gas produced by the combustion of rocket propellants stored inside th ...

s are the most common type of high power rocket, typically creating a high speed exhaust by the combustion

Combustion, or burning, is a high-temperature exothermic redox chemical reaction between a fuel (the reductant) and an oxidant, usually atmospheric oxygen, that produces oxidized, often gaseous products, in a mixture termed as smoke. Combustion ...

of fuel

A fuel is any material that can be made to react with other substances so that it releases energy as thermal energy or to be used for work (physics), work. The concept was originally applied solely to those materials capable of releasing chem ...

with an oxidizer

An oxidizing agent (also known as an oxidant, oxidizer, electron recipient, or electron acceptor) is a substance in a redox chemical reaction that gains or " accepts"/"receives" an electron from a (called the , , or ''electron donor''). In ot ...

. The stored propellant can be a simple pressurized gas or a single liquid fuel

Liquid fuels are combustible or energy-generating molecules that can be harnessed to create mechanical energy, usually producing kinetic energy; they also must take the shape of their container. It is the fumes of liquid fuels that are flammable ...

that disassociates in the presence of a catalyst (monopropellant

Monopropellants are propellants consisting of chemicals that release energy through exothermic chemical decomposition. The molecular bond energy of the monopropellant is released usually through use of a catalyst. This can be contrasted with biprop ...

), two liquids that spontaneously react on contact (hypergolic propellant

A hypergolic propellant is a rocket propellant combination used in a rocket engine, whose components spontaneously ignite when they come into contact with each other.

The two propellant components usually consist of a fuel and an oxidizer. The ...

s), two liquids that must be ignited to react (like kerosene (RP1) and liquid oxygen, used in most liquid-propellant rocket

A liquid-propellant rocket or liquid rocket uses a rocket engine burning liquid rocket propellant, liquid propellants. (Alternate approaches use gaseous or Solid-propellant rocket , solid propellants.) Liquids are desirable propellants because th ...

s), a solid combination of fuel with oxidizer (solid fuel

Solid fuel refers to various forms of solid material that can be burnt to release energy, providing heat and light through the process of combustion. Solid fuels can be contrasted with liquid fuels and gaseous fuels. Common examples of solid fu ...

), or solid fuel with liquid or gaseous oxidizer ( hybrid propellant system). Chemical rockets store a large amount of energy in an easily released form, and can be very dangerous. However, careful design, testing, construction and use minimizes risks.

History

In China,

In China, gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

-powered rockets evolved in medieval China under the Song dynasty

The Song dynasty ( ) was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 960 to 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song, who usurped the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty and went on to conquer the rest of the Fiv ...

by the 13th century. They also developed an early form of multiple rocket launcher

A multiple rocket launcher (MRL) or multiple launch rocket system (MLRS) is a type of rocket artillery system that contains multiple rocket launcher, launchers which are fixed to a single weapons platform, platform, and shoots its rocket (weapon ...

during this time. The Mongols adopted Chinese rocket technology and the invention spread via the Mongol invasions

The Mongol invasions and conquests took place during the 13th and 14th centuries, creating history's largest contiguous empire, the Mongol Empire (1206–1368), which by 1260 covered large parts of Eurasia. Historians regard the Mongol devastati ...

to the Middle East and to Europe in the mid-13th century. According to Joseph Needham, the Song navy used rockets in a military exercise

A military exercise, training exercise, maneuver (manoeuvre), or war game is the employment of military resources in Military education and training, training for military operations. Military exercises are conducted to explore the effects of ...

dated to 1245. Internal-combustion rocket propulsion is mentioned in a reference to 1264, recording that the "ground-rat", a type of firework

Fireworks are Explosive, low explosive Pyrotechnics, pyrotechnic devices used for aesthetic and entertainment purposes. They are most commonly used in fireworks displays (also called a fireworks show or pyrotechnics), combining a large numbe ...

, had frightened the Empress-Mother Gongsheng at a feast held in her honor by her son the Emperor Lizong

Emperor Lizong of Song (26 January 1205 – 16 November 1264), personal name Zhao Yun, was the 14th emperor of the Song dynasty of China and the fifth emperor of the Southern Song dynasty. He reigned from 1224 to 1264.

His original name was ...

. Subsequently, rockets are included in the military treatise ''Huolongjing

The ''Huolongjing'' (; Wade-Giles: ''Huo Lung Ching''; rendered in English as ''Fire Drake Manual'' or ''Fire Dragon Manual''), also known as ''Huoqitu'' (“Firearm Illustrations”), is a Chinese military treatise compiled and edited by Jiao ...

'', also known as the Fire Drake Manual, written by the Chinese artillery officer Jiao Yu

Jiao Yu () was a Chinese military general, philosopher, and writer of the Yuan dynasty and early Ming dynasty under Zhu Yuanzhang, who founded the dynasty and became known as the Hongwu Emperor. He was entrusted by Zhu as a leading artillery ...

in the mid-14th century. This text mentions the first known multistage rocket

A multistage rocket or step rocket is a launch vehicle that uses two or more rocket ''stages'', each of which contains its own engines and propellant. A ''tandem'' or ''serial'' stage is mounted on top of another stage; a ''parallel'' stage is ...

, the 'fire-dragon issuing from the water' (Huo long chu shui), thought to have been used by the Chinese navy.Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 510.

Medieval and early modern rockets were used militarily as incendiary weapons

Incendiary weapons, incendiary devices, incendiary munitions, or incendiary bombs are weapons designed to start fires. They may destroy structures or sensitive equipment using fire, and sometimes operate as anti-personnel weapon, anti-personnel ...

in siege

A siege () . is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or by well-prepared assault. Siege warfare (also called siegecrafts or poliorcetics) is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict charact ...

s. Between 1270 and 1280, Hasan al-Rammah wrote ''al-furusiyyah wa al-manasib al-harbiyya'' (''The Book of Military Horsemanship and Ingenious War Devices''), which included 107 gunpowder recipes, 22 of them for rockets. In Europe, Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (; or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the Scholastic accolades, scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English polymath, philosopher, scientist, theologian and Franciscans, Franciscan friar who placed co ...

mentioned firecrackers made in various parts of the world in the ''Opus Majus

The (Latin for "Greater Work") is the most important work of Roger Bacon. It was written in Medieval Latin, at the request of Pope Clement IV, to explain the work that Bacon had undertaken. The 878-page treatise ranges over all aspects of natur ...

'' of 1267. Between 1280 and 1300, the Liber Ignium gave instructions for constructing devices that are similar to firecrackers based on second hand accounts. Konrad Kyeser

Konrad Kyeser (26 August 1366 – after 1405) was a German military engineer and the author of '' Bellifortis'' (), a book on military technology that was popular throughout the 15th century. Originally conceived for King Wenceslaus, Kye ...

described rockets in his military treatise ''Bellifortis

''Bellifortis'' (, 'War Fortifications') is the first fully illustrated manual of military technology, written by Konrad Kyeser and dating from the start of the 15th century. It summarises material from classical writers on military technolog ...

'' around 1405. Giovanni Fontana, a Paduan engineer in 1420, created rocket-propelled animal figures.

The name "rocket" comes from the Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

''rocchetta'', meaning "bobbin" or "little spindle", given due to the similarity in shape to the bobbin or spool used to hold the thread from a spinning wheel. Leonhard Fronsperger and Conrad Haas

Conrad Haas (1509–1576) was an Austrian or Transylvanian Saxon military engineer.

He was a pioneer of rocket propulsion. His designs include a three-stage rocket and a manned rocket.

Haas was possibly born in Dornbach (now part of Hernal ...

adopted the Italian term into German in the mid-16th century; "rocket" appears in English by the early 17th century. ''Artis Magnae Artilleriae pars prima'', an important early modern work on rocket artillery

Rocket artillery is artillery that uses rockets as the projectile. The use of rocket artillery dates back to medieval China where devices such as fire arrows were used (albeit mostly as a psychological weapon). Fire arrows were also used in mult ...

, by Casimir Siemienowicz, was first printed in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , ; ; ) is the capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, largest city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It has a population of 933,680 in June 2024 within the city proper, 1,457,018 in the City Re ...

in 1650.

The

The Mysorean rockets

Mysorean rockets were an Indian military weapon. The iron-cased rockets were successfully deployed for military use. They were the first successful iron-cased rockets, developed in the late 18th century in the Kingdom of Mysore (part of prese ...

were the first successful iron-cased rockets, developed in the late 18th century in the Kingdom of Mysore

The Kingdom of Mysore was a geopolitical realm in southern India founded in around 1399 in the vicinity of the modern-day city of Mysore and prevailed until 1950. The territorial boundaries and the form of government transmuted substantially ...

(part of present-day India) under the rule of Hyder Ali

Hyder Ali (''Haidar'alī''; ; 1720 – 7 December 1782) was the Sultan and ''de facto'' ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore in southern India. Born as Hyder Ali, he distinguished himself as a soldier, eventually drawing the attention of Mysore's ...

.

The

The Congreve rocket

The Congreve rocket was a type of rocket artillery designed by British inventor Sir William Congreve, 2nd Baronet, Sir William Congreve in 1808.

The design was based upon Mysorean rockets, the rockets deployed by the Kingdom of Mysore against ...

was a British weapon designed and developed by Sir William Congreve in 1804. This rocket was based directly on the Mysorean rockets, used compressed powder and was fielded in the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

. It was Congreve rockets to which Francis Scott Key

Francis Scott Key (August 1, 1779January 11, 1843) was an American lawyer, author, and poet from Frederick, Maryland, best known as the author of the poem "Defence of Fort M'Henry" which was set to a popular British tune and eventually became t ...

was referring, when he wrote of the "rockets' red glare" while held captive on a British ship that was laying siege to Fort McHenry

Fort McHenry is a historical American Coastal defense and fortification, coastal bastion fort, pentagonal bastion fort on Locust Point, Baltimore, Locust Point, now a neighborhood of Baltimore, Maryland. It is best known for its role in the War ...

in 1814. Together, the Mysorean and British innovations increased the effective range of military rockets from .

The first mathematical treatment of the dynamics of rocket propulsion is due to William Moore (1813). In 1814, Congreve published a book in which he discussed the use of multiple rocket launching apparatus. In 1815 Alexander Dmitrievich Zasyadko

Alexander Dmitrievich Zasyadko (; ; 1779 – ) was a Russian general of Cossack origin. A military engineer, he played an important role in the development of rocket artillery in Russia.

Biography

Zasyadko was born into a Cossack (his fath ...

constructed rocket-launching platforms, which allowed rockets to be fired in salvo

A salvo is the simultaneous discharge of artillery or firearms including the firing of guns either to hit a target or to perform a salute. As a tactic in warfare, the intent is to cripple an enemy in many blows at once and prevent them from f ...

s (6 rockets at a time), and gun-laying devices. William Hale in 1844 greatly increased the accuracy of rocket artillery. Edward Mounier Boxer Edward Mounier Boxer (c. 1822-1898) was an English people, English inventor.

Biography

Edward M. Boxer was a colonel of the Royal Artillery.

In 1855 he was appointed Superintendent of the ''Royal Laboratory'' of the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich.

...

further improved the Congreve rocket in 1865.

William Leitch first proposed the concept of using rockets to enable human spaceflight in 1861. Leitch's rocket spaceflight description was first provided in his 1861 essay "A Journey Through Space", which was later published in his book ''God's Glory in the Heavens'' (1862). Konstantin Tsiolkovsky

Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovsky (; rus, Константин Эдуардович Циолковский, p=kənstɐnʲˈtʲin ɪdʊˈardəvʲɪtɕ tsɨɐlˈkofskʲɪj, a=Ru-Konstantin Tsiolkovsky.oga; – 19 September 1935) was a Russi ...

later (in 1903) also conceived this idea, and extensively developed a body of theory that has provided the foundation for subsequent spaceflight development.

The British Royal Flying Corps

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was the air arm of the British Army before and during the First World War until it merged with the Royal Naval Air Service on 1 April 1918 to form the Royal Air Force. During the early part of the war, the RFC sup ...

designed a guided rocket during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. Archibald Low

Archibald Montgomery Low (17 October 1888 – 13 September 1956) developed the first powered drone aircraft. He was an English consulting engineer, research physicist and inventor, and author of more than 40 books.

Low has been called the "f ...

stated "...in 1917 the Experimental Works designed an electrically steered rocket… Rocket experiments were conducted under my own patents with the help of Cdr. Brock." The patent "Improvements in Rockets" was raised in July 1918 but not published until February 1923 for security reasons. Firing and guidance controls could be either wire or wireless. The propulsion and guidance rocket eflux emerged from the deflecting cowl at the nose.

In 1920, Professor

In 1920, Professor Robert Goddard

Robert Hutchings Goddard (October 5, 1882 – August 10, 1945) was an American engineer, professor, physicist, and inventor who is credited with creating and building the world's first liquid-fueled rocket, which was successfully lau ...

of Clark University

Clark University is a private research university in Worcester, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1887 with a large endowment from its namesake Jonas Gilman Clark, a prominent businessman, Clark was one of the first modern research uni ...

published proposed improvements to rocket technology in ''A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes

Robert Hutchings Goddard (October 5, 1882 – August 10, 1945) was an American engineer, professor, physicist, and inventor who is credited with creating and building the world's first liquid-fueled rocket, which was successfully lau ...

''. In 1923, Hermann Oberth

Hermann Julius Oberth (; 25 June 1894 – 28 December 1989) was an Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian-born German physicist and rocket pioneer of Transylvanian Saxons, Transylvanian Saxon descent. Oberth supported Nazi Germany's war effort and re ...

(1894–1989) published ''Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen

Die, as a verb, refers to death, the cessation of life.

Die may also refer to:

Games

* Die, singular of dice, small throwable objects used for producing random numbers

Manufacturing

* Die (integrated circuit), a rectangular piece of a semicondu ...

'' (''The Rocket into Planetary Space''). Modern rockets originated in 1926 when Goddard attached a supersonic

Supersonic speed is the speed of an object that exceeds the speed of sound (Mach 1). For objects traveling in dry air of a temperature of 20 °C (68 °F) at sea level, this speed is approximately . Speeds greater than five times ...

(de Laval

Karl Gustaf Patrik de Laval (; 9 May 1845 – 2 February 1913) was a Swedish engineer and inventor who made important contributions to the design of steam turbines and centrifugal separation machinery for dairy.

Life

Gustaf de Laval was born a ...

) nozzle to a high pressure combustion chamber

A combustion chamber is part of an internal combustion engine in which the air–fuel ratio, fuel/air mix is burned. For steam engines, the term has also been used for an extension of the Firebox (steam engine), firebox which is used to allow a mo ...

. These nozzles turn the hot gas from the combustion chamber into a cooler, hypersonic

In aerodynamics, a hypersonic speed is one that exceeds five times the speed of sound, often stated as starting at speeds of Mach 5 and above.

The precise Mach number at which a craft can be said to be flying at hypersonic speed varies, since i ...

, highly directed jet of gas, more than doubling the thrust and raising the engine efficiency from 2% to 64%. His use of liquid propellant

The highest specific impulse chemical rockets use liquid propellants (liquid-propellant rockets). They can consist of a single chemical (a monopropellant) or a mix of two chemicals, called bipropellants. Bipropellants can further be divided into ...

s instead of gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

greatly lowered the weight and increased the effectiveness of rockets.

In 1921, the

In 1921, the Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

research and development laboratory Gas Dynamics Laboratory

Gas Dynamics Laboratory (GDL) () was the first Soviet research and development laboratory to focus on rocket technology. Its activities were initially devoted to the development of Solid-propellant rocket, solid propellant rockets, which becam ...

began developing solid-propellant rocket

A solid-propellant rocket or solid rocket is a rocket with a rocket engine that uses solid propellants (fuel/ oxidizer). The earliest rockets were solid-fuel rockets powered by gunpowder. The inception of gunpowder rockets in warfare can be c ...

s, which resulted in the first launch in 1928, which flew for approximately 1,300 metres. These rockets were used in 1931 for the world's first successful use of rockets for jet-assisted takeoff

JATO (acronym for jet-assisted take-off) is a type of assisted take-off for helping overloaded aircraft into the air by providing additional thrust in the form of small rockets. The term ''JATO'' is used interchangeably with the (more specific ...

of aircraft and became the prototypes for the Katyusha rocket launcher

The Katyusha ( rus, Катю́ша, p=kɐˈtʲuʂə, a=Ru-Катюша.ogg) is a type of rocket artillery first built and fielded by the Soviet Union in World War II. Multiple rocket launchers such as these deliver explosives to a target area m ...

, which were used during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

In 1929, Fritz Lang

Friedrich Christian Anton Lang (; December 5, 1890 – August 2, 1976), better known as Fritz Lang (), was an Austrian-born film director, screenwriter, and producer who worked in Germany and later the United States.Obituary ''Variety Obituari ...

's German science fiction film ''Woman in the Moon

''Woman in the Moon'' (German language, German ''Frau im Mond'') is a German science fiction silent film that premiered 15 October 1929 at the UFA-Palast am Zoo cinema in Berlin to an audience of 2,000. It is often considered to be one of the f ...

'' was released. It showcased the use of a multi-stage rocket

A multistage rocket or step rocket is a launch vehicle that uses two or more rocket ''stages'', each of which contains its own engines and propellant. A ''tandem'' or ''serial'' stage is mounted on top of another stage; a ''parallel'' stage is ...

, and also pioneered the concept of a rocket launch pad

A launch pad is an above-ground facility from which a rocket-powered missile or space vehicle is vertically launched. The term ''launch pad'' can be used to describe just the central launch platform (mobile launcher platform), or the entire c ...

(a rocket standing upright against a tall building before launch having been slowly rolled into place) and the rocket-launch countdown

A countdown is a sequence of backward counting to indicate the time remaining before an event is scheduled to occur. NASA commonly employs the terms "L-minus" and "T-minus" during the preparation for and anticipation of a rocket launch, and eve ...

clock."The Directors (Fritz Lang)"Sky Arts

Sky Arts (originally launched as Artsworld) is a British free-to-air television channel offering 24 hours a day of programmes dedicated to highbrow arts, including theatrical performances, films, documentaries and music (such as opera perfor ...

. Season 1, episode 6. 2018 ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'' film critic Stephen Armstrong states Lang "created the rocket industry". Lang was inspired by the 1923 book ''The Rocket into Interplanetary Space'' by Hermann Oberth, who became the film's scientific adviser and later an important figure in the team that developed the V-2 rocket. The film was thought to be so realistic that it was banned by the Nazis when they came to power for fear it would reveal secrets about the V-2 rockets.

In 1943 production of the V-2 rocket

The V2 (), with the technical name ''Aggregat (rocket family), Aggregat-4'' (A4), was the world's first long-range missile guidance, guided ballistic missile. The missile, powered by a liquid-propellant rocket engine, was developed during the S ...

began in Germany. It was designed by the Peenemünde Army Research Center

The Peenemünde Army Research Center (, HVP) was founded in 1937 as one of five military proving grounds under the German Army Weapons Office (''Heereswaffenamt''). Several German guided missiles and rockets of World War II were developed by ...

with Wernher von Braun

Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun ( ; ; 23 March 191216 June 1977) was a German–American aerospace engineer and space architect. He was a member of the Nazi Party and '' Allgemeine SS'', the leading figure in the development of ...

serving as the technical director. The V-2 became the first artificial object to travel into space by crossing the Kármán line

The Kármán line (or von Kármán line ) is a conventional definition of the Outer space#Boundary, edge of space; it is widely but not universally accepted. The international record-keeping body Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, FAI ( ...

with the vertical launch of MW 18014

MW 18014 was a German A-4 test rocket launched on 20 June 1944, at the Peenemünde Army Research Center in Peenemünde. It was the first man-made object to reach outer space, attaining an apogee of , well above the Kármán line that was estab ...

on 20 June 1944. Doug Millard, space historian and curator of space technology at the Science Museum, London

The Science Museum is a major museum on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, London. It was founded in 1857 and is one of the city's major tourist attractions, attracting 3.3 million visitors annually in 2019.

Like other publicly funded ...

, where a V-2 is exhibited in the main exhibition hall, states: "The V-2 was a quantum leap of technological change. We got to the Moon using V-2 technology but this was technology that was developed with massive resources, including some particularly grim ones. The V-2 programme was hugely expensive in terms of lives, with the Nazis using slave labour to manufacture these rockets". In parallel with the German guided-missile programme, rockets were also used on aircraft

An aircraft ( aircraft) is a vehicle that is able to flight, fly by gaining support from the Atmosphere of Earth, air. It counters the force of gravity by using either Buoyancy, static lift or the Lift (force), dynamic lift of an airfoil, or, i ...

, either for assisting horizontal take-off (RATO

Rato is a village in the Cornillon commune in the Croix-des-Bouquets Arrondissement, Ouest department of Haiti

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jama ...

), vertical take-off (Bachem Ba 349

The Bachem Ba 349 Natter () is a World War II German point-defence rocket-powered interceptor aircraft, interceptor, which was to be used in a very similar way to a manned surface-to-air missile. After a vertical take-off, which eliminated the n ...

"Natter") or for powering them ( Me 163, see list of World War II guided missiles of Germany

During World War II, Nazi Germany developed many missiles and precision-guided munition systems.

These included the first cruise missile, the first short-range ballistic missile, the first guided surface-to-air missiles, and the first anti-ship m ...

). The Allies' rocket programs were less technological, relying mostly on unguided missiles like the Soviet Katyusha rocket

The Katyusha ( rus, Катю́ша, p=kɐˈtʲuʂə, a=Ru-Катюша.ogg) is a type of rocket artillery first built and fielded by the Soviet Union in World War II. Multiple rocket launchers such as these deliver explosives to a target area m ...

in the artillery role, and the American anti tank bazooka

The Bazooka () is a Man-portable anti-tank systems, man-portable recoilless Anti-tank warfare, anti-tank rocket launcher weapon, widely deployed by the United States Army, especially during World War II. Also referred to as the "stovepipe", th ...

projectile. These used solid chemical propellants.

The Americans captured a large number of German rocket scientist

A rocket (from , and so named for its shape) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using any surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely ...

s, including Wernher von Braun, in 1945, and brought them to the United States as part of Operation Paperclip

The Operation Paperclip was a secret United States intelligence program in which more than 1,600 German scientists, engineers, and technicians were taken from former Nazi Germany to the US for government employment after the end of World War I ...

. After World War II scientists used rockets to study high-altitude conditions, by radio telemetry

Telemetry is the in situ collection of measurements or other data at remote points and their automatic transmission to receiving equipment (telecommunication) for monitoring. The word is derived from the Greek roots ''tele'', 'far off', an ...

of temperature and pressure of the atmosphere, detection of cosmic rays

Cosmic rays or astroparticles are high-energy particles or clusters of particles (primarily represented by protons or atomic nuclei) that move through space at nearly the speed of light. They originate from the Sun, from outside of the Solar ...

, and further techniques; note too the Bell X-1

The Bell X-1 (Bell Model 44) is a rocket engine–powered aircraft, designated originally as the XS-1, and was a joint National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics– U.S. Army Air Forces– U.S. Air Force supersonic research project built by B ...

, the first crewed vehicle to break the sound barrier

The sound barrier or sonic barrier is the large increase in aerodynamic drag and other undesirable effects experienced by an aircraft or other object when it approaches the speed of sound. When aircraft first approached the speed of sound, th ...

(1947). Independently, in the Soviet Union's space program research continued under the leadership

Leadership, is defined as the ability of an individual, group, or organization to "", influence, or guide other individuals, teams, or organizations.

"Leadership" is a contested term. Specialist literature debates various viewpoints on the co ...

of the chief designer Sergei Korolev

Sergei Pavlovich Korolev (14 January 1966) was the lead Soviet Aerospace engineering, rocket engineer and spacecraft designer during the Space Race between the United States and the Soviet Union in the 1950s and 1960s. He invented the R-7 Sem ...

(1907–1966).

During the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

rockets became extremely important militarily with the development of modern intercontinental ballistic missiles

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range (aeronautics), range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more Thermonuclear weapon, thermonuclear warheads). Conven ...

(ICBMs). The 1960s saw rapid development of rocket technology, particularly in the Soviet Union (Vostok

Vostok () refers to east in Russian but may also refer to:

Spaceflight

* Vostok programme, Soviet human spaceflight project

* Vostok (spacecraft), a type of spacecraft built by the Soviet Union

* Vostok (rocket family), family of rockets derived ...

, Soyuz

Soyuz is a transliteration of the Cyrillic text Союз (Russian language, Russian and Ukrainian language, Ukrainian, 'Union'). It can refer to any union, such as a trade union (''profsoyuz'') or the Soviet Union, Union of Soviet Socialist Republi ...

, Proton

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , Hydron (chemistry), H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' (elementary charge). Its mass is slightly less than the mass of a neutron and approximately times the mass of an e ...

) and in the United States (e.g. the X-15

The North American X-15 is a Hypersonic speed, hypersonic rocket-powered aircraft which was operated by the United States Air Force and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) as part of the List of X-planes, X-plane series of ...

). Rockets came into use for space exploration

Space exploration is the process of utilizing astronomy and space technology to investigate outer space. While the exploration of space is currently carried out mainly by astronomers with telescopes, its physical exploration is conducted bo ...

. American crewed programs (Project Mercury

Project Mercury was the first human spaceflight program of the United States, running from 1958 through 1963. An early highlight of the Space Race, its goal was to put a man into Earth orbit and return him safely, ideally before the Soviet Un ...

, Project Gemini

Project Gemini () was the second United States human spaceflight program to fly. Conducted after the first American crewed space program, Project Mercury, while the Apollo program was still in early development, Gemini was conceived in 1961 and ...

and later the Apollo programme) culminated in 1969 with the first crewed landing on the Moon – using equipment launched by the Saturn V

The Saturn V is a retired American super heavy-lift launch vehicle developed by NASA under the Apollo program for human exploration of the Moon. The rocket was human-rated, had multistage rocket, three stages, and was powered by liquid-propel ...

rocket.

Types

;Vehicle configurations Rocket vehicles are often constructed in the archetypal tall thin "rocket" shape that takes off vertically, but there are actually many different types of rockets including: * tiny models such asballoon rocket

A balloon rocket is a rubber balloon filled with air or other gases. Besides being simple toys, balloon rockets are widely used as a teaching device to demonstrate basic physics.

How it works

To launch a simple rocket, the untied opening of an ...

s, water rocket

A water rocket is a type of model rocket using water as its reaction mass. The water is forced out by a pressurized gas, typically compressed air. Like all rocket engines, it operates on the principle of Newton's third law, Newton's third law o ...

s, skyrocket

A skyrocket, also known as a rocket, is a type of firework that uses a solid-fuel rocket to rise quickly into the sky; a bottle rocket is a small skyrocket. At the apex of its ascent, it is usual for a variety of effects (stars, bangs, crackl ...

s or small solid rockets that can be purchased at a hobby store

A hobby shop (or hobby store) sells recreational items for hobbyists.

Types Modelling

Classical hobby stores specialize in modelling and craft supplies and specialty magazines for model airplanes (military craft, private airplanes and airliners ...

* missile

A missile is an airborne ranged weapon capable of self-propelled flight aided usually by a propellant, jet engine or rocket motor.

Historically, 'missile' referred to any projectile that is thrown, shot or propelled towards a target; this ...

s

* space rockets such as the enormous Saturn V

The Saturn V is a retired American super heavy-lift launch vehicle developed by NASA under the Apollo program for human exploration of the Moon. The rocket was human-rated, had multistage rocket, three stages, and was powered by liquid-propel ...

used for the Apollo program

The Apollo program, also known as Project Apollo, was the United States human spaceflight program led by NASA, which Moon landing, landed the first humans on the Moon in 1969. Apollo followed Project Mercury that put the first Americans in sp ...

* rocket cars

* rocket bike

* rocket-powered aircraft

A rocket-powered aircraft or rocket plane is an aircraft that uses a rocket engine for propulsion, sometimes in addition to airbreathing jet engines. Rocket planes can achieve much higher speeds than similarly sized jet aircraft, but typicall ...

(including rocket-assisted takeoff of conventional aircraft – RATO

Rato is a village in the Cornillon commune in the Croix-des-Bouquets Arrondissement, Ouest department of Haiti

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jama ...

)

* rocket sled

A rocket sled is a test platform that slides along a track (e.g. set of rails), propelled by rockets.

A rocket sled differs from a rocket car in not using wheels; at high speeds wheels would spin to pieces due to the extreme centrifugal forces ...

s

* rocket trains

* rocket torpedoes

* rocket-powered jet pack

A jet pack, rocket belt, rocket pack or flight pack is a device worn as a backpack which uses jets to propel the wearer through the air. The concept has been present in science fiction for almost a century and the first working experimental d ...

s

* rapid escape systems such as ejection seat

In aircraft, an ejection seat or ejector seat is a system designed to rescue the aircraft pilot, pilot or other aircrew, crew of an aircraft (usually military) in an emergency. In most designs, the seat is propelled out of the aircraft by an exp ...

s and launch escape system

A launch escape system (LES) or launch abort system (LAS) is a crew-safety system connected to a space capsule. It is used in the event of a critical emergency to quickly separate the capsule from its launch vehicle in case of an emergency requiri ...

s

* space probe

Uncrewed spacecraft or robotic spacecraft are spacecraft without people on board. Uncrewed spacecraft may have varying levels of autonomy from human input, such as remote control, or remote guidance. They may also be autonomous, in which th ...

s

Design

A rocket design can be as simple as a cardboard tube filled withblack powder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

, but to make an efficient, accurate rocket or missile involves overcoming a number of difficult problems. The main difficulties include cooling the combustion chamber, pumping the fuel (in the case of a liquid fuel), and controlling and correcting the direction of motion.

Components

Rockets consist of apropellant

A propellant (or propellent) is a mass that is expelled or expanded in such a way as to create a thrust or another motive force in accordance with Newton's third law of motion, and "propel" a vehicle, projectile, or fluid payload. In vehicle ...

, a place to put propellant (such as a propellant tank

A propellant tank is a container which is part of a vehicle, where propellant is stored prior to use. Propellant tanks vary in construction, and may be a fuel tank in the case of many aircraft.

In rocket vehicles, propellant tanks are fairly sophi ...

), and a nozzle

A nozzle is a device designed to control the direction or characteristics of a fluid flow (specially to increase velocity) as it exits (or enters) an enclosed chamber or pipe (material), pipe.

A nozzle is often a pipe or tube of varying cross ...

. They may also have one or more rocket engine

A rocket engine is a reaction engine, producing thrust in accordance with Newton's third law by ejecting reaction mass rearward, usually a high-speed Jet (fluid), jet of high-temperature gas produced by the combustion of rocket propellants stor ...

s, directional stabilization device(s) (such as fins

A fin is a thin component or appendage attached to a larger body or structure. Fins typically function as foil (fluid mechanics), foils that produce lift (force), lift or thrust, or provide the ability to steer or stabilize motion while travelin ...

, vernier engines or engine gimbal

A gimbal is a pivoted support that permits rotation of an object about an axis. A set of three gimbals, one mounted on the other with orthogonal pivot axes, may be used to allow an object mounted on the innermost gimbal to remain independent of ...

s for thrust vectoring

Thrust vectoring, also known as thrust vector control (TVC), is the ability of an aircraft, rocket or other vehicle to manipulate the direction of the thrust from its engine(s) or motor(s) to Aircraft flight control system, control the Spacecra ...

, gyroscope

A gyroscope (from Ancient Greek γῦρος ''gŷros'', "round" and σκοπέω ''skopéō'', "to look") is a device used for measuring or maintaining Orientation (geometry), orientation and angular velocity. It is a spinning wheel or disc in ...

s) and a structure (typically monocoque

Monocoque ( ), also called structural skin, is a structural system in which loads are supported by an object's external skin, in a manner similar to an egg shell. The word ''monocoque'' is a French term for "single shell".

First used for boats, ...

) to hold these components together. Rockets intended for high speed atmospheric use also have an aerodynamic

Aerodynamics () is the study of the motion of atmosphere of Earth, air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dynamics and its subfield of gas dynamics, and is an ...

fairing such as a nose cone

A nose cone is the conically shaped forwardmost section of a rocket, guided missile or aircraft, designed to modulate oncoming fluid dynamics, airflow behaviors and minimize aerodynamic drag. Nose cones are also designed for submerged wat ...

, which usually holds the payload.

As well as these components, rockets can have any number of other components, such as wings (rocketplane

A rocket-powered aircraft or rocket plane is an aircraft that uses a rocket engine for propulsion, sometimes in addition to airbreathing jet engines. Rocket planes can achieve much higher speeds than similarly sized jet aircraft, but typically ...

s), parachute

A parachute is a device designed to slow an object's descent through an atmosphere by creating Drag (physics), drag or aerodynamic Lift (force), lift. It is primarily used to safely support people exiting aircraft at height, but also serves va ...

s, wheels ( rocket cars), even, in a sense, a person ( rocket belt). Vehicles frequently possess navigation systems and guidance system

A guidance system is a virtual or physical device, or a group of devices implementing a controlling the movement of a ship, aircraft, missile, rocket, satellite, or any other moving object. Guidance is the process of calculating the changes in pos ...

s that typically use satellite navigation

A satellite navigation or satnav system is a system that uses satellites to provide autonomous geopositioning. A satellite navigation system with global coverage is termed global navigation satellite system (GNSS). , four global systems are ope ...

and inertial navigation system

An inertial navigation system (INS; also inertial guidance system, inertial instrument) is a navigation device that uses motion sensors (accelerometers), rotation sensors (gyroscopes) and a computer to continuously calculate by dead reckoning th ...

s.

Engines

Rocket engines employ the principle of jet propulsion. The rocket engines powering rockets come in a great variety of different types; a comprehensive list can be found in the main article,

Rocket engines employ the principle of jet propulsion. The rocket engines powering rockets come in a great variety of different types; a comprehensive list can be found in the main article, Rocket engine

A rocket engine is a reaction engine, producing thrust in accordance with Newton's third law by ejecting reaction mass rearward, usually a high-speed Jet (fluid), jet of high-temperature gas produced by the combustion of rocket propellants stor ...

. Most current rockets are chemically powered rockets (usually internal combustion engines

An internal combustion engine (ICE or IC engine) is a heat engine in which the combustion of a fuel occurs with an oxidizer (usually air) in a combustion chamber that is an integral part of the working fluid flow circuit. In an internal comb ...

, but some employ a decomposing monopropellant

Monopropellants are propellants consisting of chemicals that release energy through exothermic chemical decomposition. The molecular bond energy of the monopropellant is released usually through use of a catalyst. This can be contrasted with biprop ...

) that emit a hot exhaust gas

Exhaust gas or flue gas is emitted as a result of the combustion of fuels such as natural gas, gasoline (petrol), diesel fuel, fuel oil, biodiesel blends, or coal. According to the type of engine, it is discharged into the atmosphere through ...

. A rocket engine can use gas propellants, solid propellant

A propellant (or propellent) is a mass that is expelled or expanded in such a way as to create a thrust or another motive force in accordance with Newton's third law of motion, and "propel" a vehicle, projectile, or fluid payload. In vehicles, th ...

, liquid propellant

The highest specific impulse chemical rockets use liquid propellants (liquid-propellant rockets). They can consist of a single chemical (a monopropellant) or a mix of two chemicals, called bipropellants. Bipropellants can further be divided into ...

, or a hybrid mixture of both solid and liquid. Some rockets use heat or pressure that is supplied from a source other than the chemical reaction

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the chemistry, chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. When chemical reactions occur, the atoms are rearranged and the reaction is accompanied by an Gibbs free energy, ...

of propellant(s), such as steam rocket

A steam rocket (also known as a hot water rocket) is a thermal rocket that uses water held in a pressure vessel at a high temperature, such that its saturated vapor pressure is significantly greater than ambient pressure. The water is allowed to e ...

s, solar thermal rocket

A solar thermal rocket is a theoretical spacecraft propulsion system that would make use of solar power to directly heat reaction mass, and therefore would not require an electrical generator, like most other forms of solar-powered propulsion do. ...

s, nuclear thermal rocket

A nuclear thermal rocket (NTR) is a type of thermal rocket where the heat from a nuclear reaction replaces the chemical energy of the rocket propellant, propellants in a chemical rocket. In an NTR, a working fluid, usually liquid hydrogen, is ...

engines or simple pressurized rockets such as water rocket

A water rocket is a type of model rocket using water as its reaction mass. The water is forced out by a pressurized gas, typically compressed air. Like all rocket engines, it operates on the principle of Newton's third law, Newton's third law o ...

or cold gas thruster

A cold gas thruster (or a cold gas propulsion system) is a type of rocket engine which uses the expansion of a (typically inert) pressurized gas to generate thrust. As opposed to traditional rocket engines, a cold gas thruster does not house any co ...

s. With combustive propellants a chemical reaction is initiated between the fuel

A fuel is any material that can be made to react with other substances so that it releases energy as thermal energy or to be used for work (physics), work. The concept was originally applied solely to those materials capable of releasing chem ...

and the oxidizer

An oxidizing agent (also known as an oxidant, oxidizer, electron recipient, or electron acceptor) is a substance in a redox chemical reaction that gains or " accepts"/"receives" an electron from a (called the , , or ''electron donor''). In ot ...

in the combustion

Combustion, or burning, is a high-temperature exothermic redox chemical reaction between a fuel (the reductant) and an oxidant, usually atmospheric oxygen, that produces oxidized, often gaseous products, in a mixture termed as smoke. Combustion ...

chamber, and the resultant hot gases accelerate out of a rocket engine nozzle

A rocket engine nozzle is a propelling nozzle (usually of the de Laval type) used in a rocket engine to expand and accelerate combustion products to high supersonic velocities.

Simply: propellants pressurized by either pumps or high pressure ...

(or nozzle

A nozzle is a device designed to control the direction or characteristics of a fluid flow (specially to increase velocity) as it exits (or enters) an enclosed chamber or pipe (material), pipe.

A nozzle is often a pipe or tube of varying cross ...

s) at the rearward-facing end of the rocket. The acceleration

In mechanics, acceleration is the Rate (mathematics), rate of change of the velocity of an object with respect to time. Acceleration is one of several components of kinematics, the study of motion. Accelerations are Euclidean vector, vector ...

of these gases through the engine exerts force ("thrust") on the combustion chamber and nozzle, propelling the vehicle (according to Newton's third law

Newton's laws of motion are three physical laws that describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it. These laws, which provide the basis for Newtonian mechanics, can be paraphrased as follows:

# A body re ...

). This actually happens because the force (pressure times area) on the combustion chamber wall is unbalanced by the nozzle opening; this is not the case in any other direction. The shape of the nozzle also generates force by directing the exhaust gas along the axis of the rocket.

Propellant

Rocket propellant is mass that is stored, usually in some form of

Rocket propellant is mass that is stored, usually in some form of propellant

A propellant (or propellent) is a mass that is expelled or expanded in such a way as to create a thrust or another motive force in accordance with Newton's third law of motion, and "propel" a vehicle, projectile, or fluid payload. In vehicle ...

tank or casing, prior to being used as the propulsive mass that is ejected from a rocket engine

A rocket engine is a reaction engine, producing thrust in accordance with Newton's third law by ejecting reaction mass rearward, usually a high-speed Jet (fluid), jet of high-temperature gas produced by the combustion of rocket propellants stor ...

in the form of a fluid

In physics, a fluid is a liquid, gas, or other material that may continuously motion, move and Deformation (physics), deform (''flow'') under an applied shear stress, or external force. They have zero shear modulus, or, in simpler terms, are M ...

jet to produce thrust

Thrust is a reaction force described quantitatively by Newton's third law. When a system expels or accelerates mass in one direction, the accelerated mass will cause a force of equal magnitude but opposite direction to be applied to that ...

. For chemical rockets often the propellants are a fuel such as liquid hydrogen

Liquid hydrogen () is the liquid state of the element hydrogen. Hydrogen is found naturally in the molecule, molecular H2 form.

To exist as a liquid, H2 must be cooled below its critical point (thermodynamics), critical point of 33 Kelvins, ...

or kerosene

Kerosene, or paraffin, is a combustibility, combustible hydrocarbon liquid which is derived from petroleum. It is widely used as a fuel in Aviation fuel, aviation as well as households. Its name derives from the Greek (''kērós'') meaning " ...

burned with an oxidizer such as liquid oxygen

Liquid oxygen, sometimes abbreviated as LOX or LOXygen, is a clear cyan liquid form of dioxygen . It was used as the oxidizer in the first liquid-fueled rocket invented in 1926 by Robert H. Goddard, an application which is ongoing.

Physical ...

or nitric acid

Nitric acid is an inorganic compound with the formula . It is a highly corrosive mineral acid. The compound is colorless, but samples tend to acquire a yellow cast over time due to decomposition into nitrogen oxide, oxides of nitrogen. Most com ...

to produce large volumes of very hot gas. The oxidiser is either kept separate and mixed in the combustion chamber, or comes premixed, as with solid rockets.

Sometimes the propellant is not burned but still undergoes a chemical reaction, and can be a 'monopropellant' such as hydrazine

Hydrazine is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a simple pnictogen hydride, and is a colourless flammable liquid with an ammonia-like odour. Hydrazine is highly hazardous unless handled in solution as, for example, hydraz ...

, nitrous oxide

Nitrous oxide (dinitrogen oxide or dinitrogen monoxide), commonly known as laughing gas, nitrous, or factitious air, among others, is a chemical compound, an Nitrogen oxide, oxide of nitrogen with the Chemical formula, formula . At room te ...

or hydrogen peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide is a chemical compound with the formula . In its pure form, it is a very pale blue liquid that is slightly more viscosity, viscous than Properties of water, water. It is used as an oxidizer, bleaching agent, and antiseptic, usua ...

that can be catalytically decomposed to hot gas.

Alternatively, an inert propellant can be used that can be externally heated, such as in steam rocket

A steam rocket (also known as a hot water rocket) is a thermal rocket that uses water held in a pressure vessel at a high temperature, such that its saturated vapor pressure is significantly greater than ambient pressure. The water is allowed to e ...

, solar thermal rocket

A solar thermal rocket is a theoretical spacecraft propulsion system that would make use of solar power to directly heat reaction mass, and therefore would not require an electrical generator, like most other forms of solar-powered propulsion do. ...

or nuclear thermal rocket

A nuclear thermal rocket (NTR) is a type of thermal rocket where the heat from a nuclear reaction replaces the chemical energy of the rocket propellant, propellants in a chemical rocket. In an NTR, a working fluid, usually liquid hydrogen, is ...

s.

For smaller, low performance rockets such as attitude control thruster

Spacecraft attitude control is the process of controlling the orientation of a spacecraft (vehicle or satellite) with respect to an inertial frame of reference or another entity such as the celestial sphere, certain fields, and nearby objects, ...

s where high performance is less necessary, a pressurised fluid is used as propellant that simply escapes the spacecraft through a propelling nozzle.

Pendulum rocket fallacy

The first

The first liquid-fuel rocket

A liquid-propellant rocket or liquid rocket uses a rocket engine burning liquid propellants. (Alternate approaches use gaseous or solid propellants.) Liquids are desirable propellants because they have reasonably high density and their combustio ...

, constructed by Robert H. Goddard

Robert Hutchings Goddard (October 5, 1882 – August 10, 1945) was an American engineer, professor, physicist, and inventor who is credited with creating and building the world's first liquid-fueled rocket, which was successfully lau ...

, differed significantly from modern rockets. The rocket engine

A rocket engine is a reaction engine, producing thrust in accordance with Newton's third law by ejecting reaction mass rearward, usually a high-speed Jet (fluid), jet of high-temperature gas produced by the combustion of rocket propellants stor ...

was at the top and the fuel tank at the bottom of the rocket, based on Goddard's belief that the rocket would achieve stability by "hanging" from the engine like a pendulum

A pendulum is a device made of a weight suspended from a pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate i ...

in flight. However, the rocket veered off course and crashed away from the launch site

A spaceport or cosmodrome is a site for launching or receiving spacecraft, by analogy to a seaport for ships or an airport for aircraft. The word ''spaceport''—and even more so ''cosmodrome''—has traditionally referred to sites capable of ...

, indicating that the rocket was no more stable than one with the rocket engine at the base.

Uses

Rockets or other similar reaction devices carrying their own propellant must be used when there is no other substance (land, water, or air) or force (gravity

In physics, gravity (), also known as gravitation or a gravitational interaction, is a fundamental interaction, a mutual attraction between all massive particles. On Earth, gravity takes a slightly different meaning: the observed force b ...

, magnetism

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that occur through a magnetic field, which allows objects to attract or repel each other. Because both electric currents and magnetic moments of elementary particles give rise to a magnetic field, ...

, light

Light, visible light, or visible radiation is electromagnetic radiation that can be visual perception, perceived by the human eye. Visible light spans the visible spectrum and is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400– ...

) that a vehicle