Robert Seyfarth on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

and the Secretary of State for James Garfield">United States Secretary of State">Secretary of State for James Garfield and Chester A. Arthur] and Julius Rosenwald.

Robert Seyfarth ( ) was an American architect based in

f the nineteenth century/nowiki> by returning to fundamental architectural principles. The ideals this architecture sought to express were the very ones the most inventive Chicago architects were trying to embody in their own work - order, harmony, and repose ...". As a result, the conception of modern architecture was anything but a static event. "Architects and critics engaged in lively debates concerning the definition of modern architecture and the future direction of building design. This discourse reflected the development of diverse architectural ideologies and forms that ranged from Beaux-Arts classicism to streamlining."

Robert Seyfarth grew up as a member of a prominent local family. His grandfather William Seyfarth had come to the United States in 1848 from Schloss Tonndorf in what is now the state of

Robert Seyfarth grew up as a member of a prominent local family. His grandfather William Seyfarth had come to the United States in 1848 from Schloss Tonndorf in what is now the state of

Edward Seyfarth was active in community affairs on many levels. Not only did he own and operate the local hardware store, but in 1874 he was a charter member of the Blue Island Ancient Free and Accepted Masons and in 1890 was one of the founders of the Calumet State Bank. He served as village treasurer from 1880–1886 and as village trustee from 1886–1889 and again from 1893-1895. Over the years other members of the family were also active in the community - they were involved in banking, the board of education, and the Current Topics Club (later the Blue Island Woman's Club), who was largely responsible for the founding of the Blue Island Public Library. Charles A. Seyfarth was one of the founding members of the Blue Island

From the time his grandparents arrived in 1848 to the time Robert Seyfarth left Blue Island in about 1910 for Highland Park, the village had grown from being a pioneering hamlet of about 200 persons to a prosperous industrial suburb with a population of nearly 11,000, which the noted publisher and historian Alfred T. Andreas had called "...a quiet, though one among the prettiest little suburban towns in the West". It was in this atmosphere that Seyfarth grew up, attended primary school, married his first wife Nell Martin (1878–1928), and built their first home.

Seyfarth began his architectural education at the Chicago Manual Training School, which was founded by the Commercial Club (after 1907 The Commercial Club of Chicago) out of a concern for the quality of the education of skilled labor in the Chicago region. The school had opened its doors on January 4, 1884 with four teachers and seventy-four pupils and the support of the sixty members of the club who had "pledged themselves to found a manual training school, and guaranteed for its construction, equipment and support

Seyfarth began his architectural education at the Chicago Manual Training School, which was founded by the Commercial Club (after 1907 The Commercial Club of Chicago) out of a concern for the quality of the education of skilled labor in the Chicago region. The school had opened its doors on January 4, 1884 with four teachers and seventy-four pupils and the support of the sixty members of the club who had "pledged themselves to found a manual training school, and guaranteed for its construction, equipment and support

Although it was to take him in a totally different direction, Chicago Manual Training School, with its focus on the industrial arts, was a logical choice for the secondary education of the oldest son of a hardware dealer, especially in an age when primogeniture was considered important. Besides his classes in drawing Seyfarth studied mathematics, English, French, Latin, history, physics, chemistry, foundry and forgework, machine shopwork, woodwork, political economy and civil government. He attended classes and graduated in 1895 with the son of Dankmar Adler, the son and the nephew of

Despite the fact that it was 17 miles away, Seyfarth enjoyed the advantage of the school's convenient location. The railway depot that marked the beginning of his trip was a two-block walk from his home at Grove Street and Western Avenue, with the end of the ride being at the Illinois Central's Twelfth Street Station, which was located directly across the stree

from the school

The ride would have taken him directly over the

The education of an architect in the early years of the 20th century was quite different from what it is today, and the ambitious prospective architect could take many avenues to acquire it. In April 1905, for example, Seyfarth attended his first meeting as a member of the Chicago Architectural Club, which had been founded in 1885 as the Chicago Architectural Sketch Club by James H. Carpenter, a prominent Chicago draftsman, with the support of the magazine ''

The education of an architect in the early years of the 20th century was quite different from what it is today, and the ambitious prospective architect could take many avenues to acquire it. In April 1905, for example, Seyfarth attended his first meeting as a member of the Chicago Architectural Club, which had been founded in 1885 as the Chicago Architectural Sketch Club by James H. Carpenter, a prominent Chicago draftsman, with the support of the magazine '' ts/nowiki> ever-changing and ever-extending boundary lines." As the Chicago architect

Because of his association with the Chicago Architectural Club, Seyfarth would have ample opportunity to become acquainted with the major players of Chicago's progressive architectural community, a large number of whom were active members. These were relationships that Maher would doubtless have encouraged. Notables among the list included Charles B. Atwood,

The club's headquarters for many years was located in the former mansion of the piano manufacturer William W. Kimball at 1801 Prairie Ave. in Chicago. It ceased to operate as an active organization in 1940 and was dissolved in 1967, but exists again today after it was re-formed in 1979.

Robert Seyfarth graduated from the Chicago Manual Training School in 1895, and literature published by the school shows his position upon graduation to be that of a "Draughtsman" for the Chicago architect August Fiedler. Fiedler was born in Germany and came to the United States in 1869, establishing himself first in New York City and then in Chicago as a much sought-after designer of high-end residential interiors, later becoming an architect. He designed some of the woodwork and other decoration for the Samuel Nickerson House (1879–1883) on Erie Street in Chicago (now the Driehaus Museum), and the interiors of the

Robert Seyfarth graduated from the Chicago Manual Training School in 1895, and literature published by the school shows his position upon graduation to be that of a "Draughtsman" for the Chicago architect August Fiedler. Fiedler was born in Germany and came to the United States in 1869, establishing himself first in New York City and then in Chicago as a much sought-after designer of high-end residential interiors, later becoming an architect. He designed some of the woodwork and other decoration for the Samuel Nickerson House (1879–1883) on Erie Street in Chicago (now the Driehaus Museum), and the interiors of the

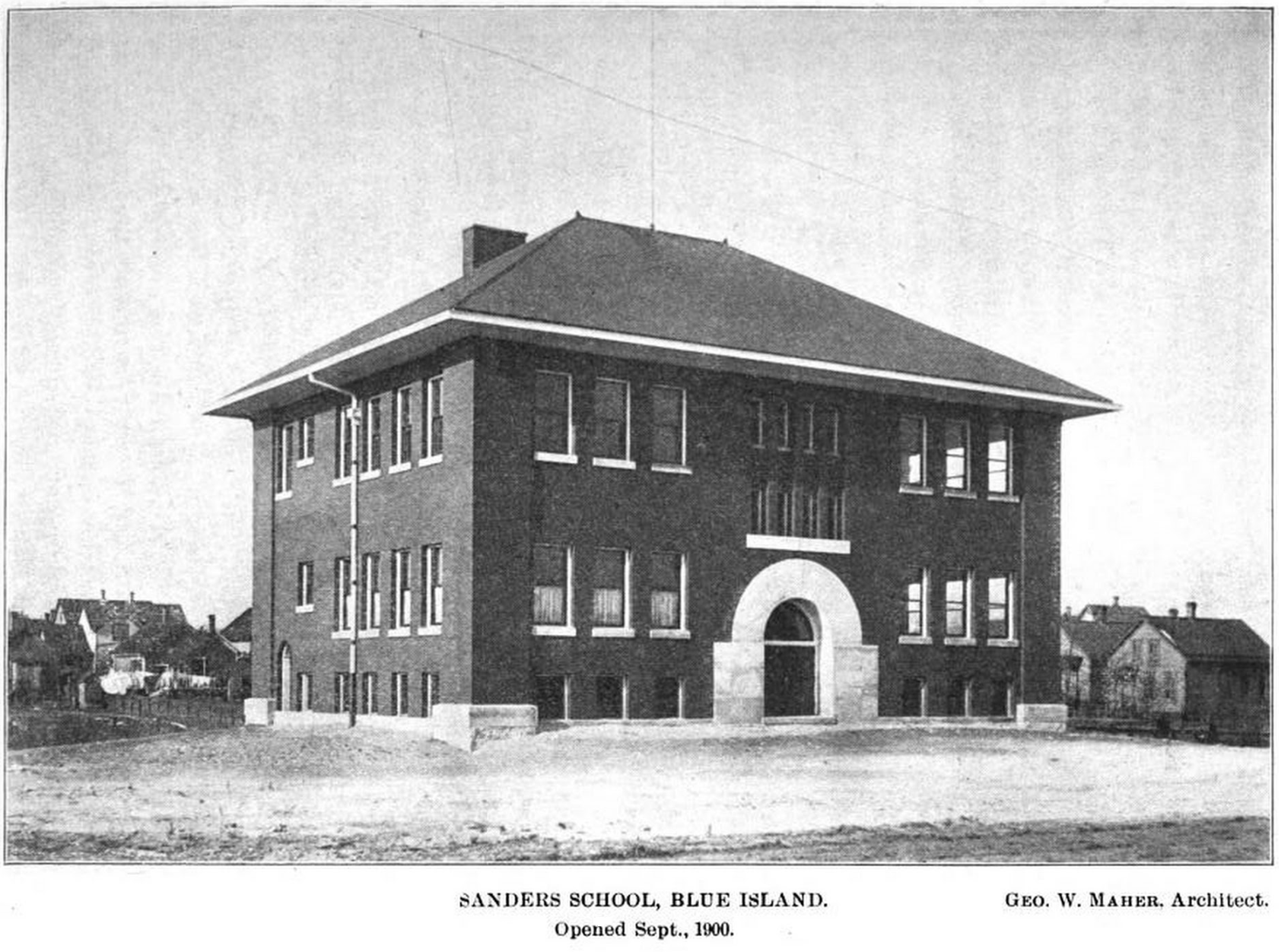

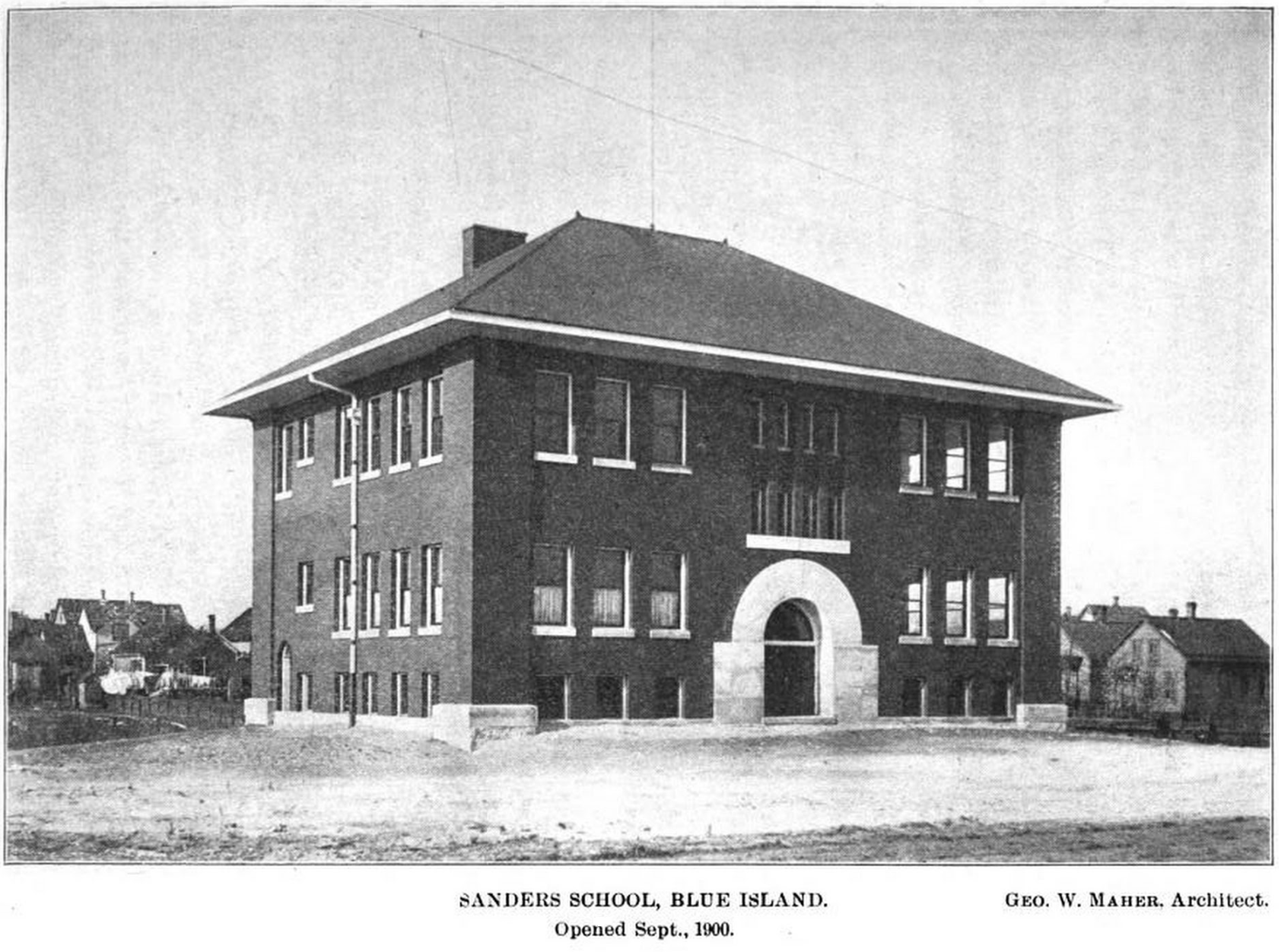

Maher was an influential architect associated with the /nowiki>Frank Lloyd

The beginning of Maher's life, however, wasn't quite so auspicious. He was born in

The beginning of Maher's life, however, wasn't quite so auspicious. He was born in

How long Maher worked for Bauer and his partners is not known, but by the 1880s he was working in the office of /nowiki>its inherent

Toward the end of his life, when he was chairman of the Municipal Arts and Town Planning Committee of the Illinois Chapter of the

It is likely that Robert Seyfarth was introduced to Maher through family connections. Because Edward Seyfarth was an important local businessman, he would almost certainly have been familiar with the established architect's work that was being built in Blue Island.

Robert Seyfarth began to offer his services as an independent architect almost immediately after his graduation from Chicago Manual Training School. A late 19th century directory of Blue Island, published while he was most likely still working for the Chicago school board, contained a listing for "Robert Seyfarth, Architect" that showed the Seyfarth building (demolished 1992) as his address. After he began working in Maher's office his independent work began to show the influences of Maher and other Prairie School architects, and his earliest known independently attributed work comes at this time. In 1905 a "Neat Little Dwelling House" was published with plans, bills of material and estimate of costs in the May edition of ''The National Builder'' magazine.

Robert Seyfarth began to offer his services as an independent architect almost immediately after his graduation from Chicago Manual Training School. A late 19th century directory of Blue Island, published while he was most likely still working for the Chicago school board, contained a listing for "Robert Seyfarth, Architect" that showed the Seyfarth building (demolished 1992) as his address. After he began working in Maher's office his independent work began to show the influences of Maher and other Prairie School architects, and his earliest known independently attributed work comes at this time. In 1905 a "Neat Little Dwelling House" was published with plans, bills of material and estimate of costs in the May edition of ''The National Builder'' magazine.

Seyfarth earned his architectural license from the state of Illinois in October 1908 and continued to work for Maher until about 1909, at which time he opened his own practice. In the early years the office was located in the Corn Exchange Bank Building (1908,

In 1911 Robert Seyfarth designed and built a

, the Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hung ...Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

, Illinois. He spent the formative years of his professional career working for the noted Prairie School architect George Washington Maher. A member of the influential Chicago Architectural Club, Seyfarth was a product of the Chicago School of Architecture.

Influences of style

Although his early independent projects directly reflected Maher's stylistic influences, as his own style developed Seyfarth's work became distinguished more as a distillation of prevailing revivalist architecture, characterized not by the frequent devotion to detail that typified the movement but by strong geometry, a highly refined sense of proportion, and the selective, discriminating use of historical references. Although any use of these references was condemned by many of the proponents of what was seen as "modern" architecture in the ensuing years, "the neoclassical impulse ... was an effort to purge American architecture of the wilder excesses of historical revivalismJoseph Hudnut

Joseph F. Hudnut (March 27, 1886 – January 16, 1968) was an American architect scholar and professor who was the first dean of Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. He was responsible for bringing the German modernist architects Wa ...

, the first dean of Harvard University's School of Design and a noted proponent of modern architecture, recognized the emotional limitations of houses that expressed their design using the typical modern vocabulary of glass, concrete and steel: "They have often interesting aesthetic qualities, they arrest us by their novelty and their drama, but too often they have very little to say to us".

The case for the use of historic references in modern architecture was made by no less than William Adams Delano

William Adams Delano (January 21, 1874 – January 12, 1960) was an American architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs, and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection wi ...

(1874-1960), who was considered to be one among the "new generation of architects hoshaped and developed American taste, producing a style leavened with erudite abstraction and sparing composition". Delano argued that if a project was "handled with freedom and ... answered the needs of our present day clients, it will be really expressive of our own time". Seyfarth opted to take his career down this divergent path, and in doing so created a legacy of architecture that "speaks of good breeding with an independent spirit."

Background

Robert Seyfarth grew up as a member of a prominent local family. His grandfather William Seyfarth had come to the United States in 1848 from Schloss Tonndorf in what is now the state of

Robert Seyfarth grew up as a member of a prominent local family. His grandfather William Seyfarth had come to the United States in 1848 from Schloss Tonndorf in what is now the state of Thuringia

Thuringia (; officially the Free State of Thuringia, ) is one of Germany, Germany's 16 States of Germany, states. With 2.1 million people, it is 12th-largest by population, and with 16,171 square kilometers, it is 11th-largest in area.

Er ...

, Germany, with the intention of opening a tavern (what would now be considered an inn) in Chicago. Advised to locate outside of the city, he settled with his wife Louise in Blue Island, which a couple of years earlier had begun to experience an influx of immigration from what was then known as the German Confederation

The German Confederation ( ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, which had been dissolved ...

.

William purchased a building that was standing at the south-west corner of Grove Street and Western Avenue and opened his business. The location was a good one - it was on what was then called the Wabash Road a day's journey

A day's journey in pre-modern literature, including the Bible and ancient geographers and ethnographers such as Herodotus, is a measurement of distance.

In the Bible, it is not as precisely defined as other Biblical measurements of distance; the ...

from Chicago, which guaranteed the tavern a steady supply of prospective customers for many years. At about the same time he purchased a stone quarry about a mile south-west of the settlement (where Robbins, Illinois

Robbins is a village and southwest suburb of Chicago in Cook County, Illinois, United States. The population was 4,629 at the 2020 census. It is the second oldest African American incorporated town in the north following Brooklyn, Illinois, an ...

now stands) and operated it concurrently with the inn, although apparently without as much success. He was a member of the school board when Blue Island built its first brick schoolhouse in 1856, and served as clerk and later as assessor for the township of Worth from 1854 until he died in 1860. William and Louise had five sons, including Edward, who was the father of the architect.Edward Seyfarth was active in community affairs on many levels. Not only did he own and operate the local hardware store, but in 1874 he was a charter member of the Blue Island Ancient Free and Accepted Masons and in 1890 was one of the founders of the Calumet State Bank. He served as village treasurer from 1880–1886 and as village trustee from 1886–1889 and again from 1893-1895. Over the years other members of the family were also active in the community - they were involved in banking, the board of education, and the Current Topics Club (later the Blue Island Woman's Club), who was largely responsible for the founding of the Blue Island Public Library. Charles A. Seyfarth was one of the founding members of the Blue Island

Elks

The Embeddable Linux Kernel Subset (ELKS), formerly known as Linux-8086, is a Linux-like operating system kernel. It is a subset of the Linux kernel, intended for 16-bit computers with limited processor and memory resources such as machines pow ...

in 1916. (The architect was himself apparently a person of catholic interests - he was an active member of the Poultry Fancier's Association during the time that Blue Island was the headquarters for the Northeastern Illinois Fancier's Association in the early years of the 20th century). From the time his grandparents arrived in 1848 to the time Robert Seyfarth left Blue Island in about 1910 for Highland Park, the village had grown from being a pioneering hamlet of about 200 persons to a prosperous industrial suburb with a population of nearly 11,000, which the noted publisher and historian Alfred T. Andreas had called "...a quiet, though one among the prettiest little suburban towns in the West". It was in this atmosphere that Seyfarth grew up, attended primary school, married his first wife Nell Martin (1878–1928), and built their first home.

Education and career

Chicago Manual Training School

ith

The Ith () is a ridge in Germany's Central Uplands which is up to 439 m high. It lies about 40 km southwest of Hanover and, at 22 kilometers, is the longest line of crags in North Germany.

Geography

Location

The Ith is i ...

the sum of one hundred thousand dollars". The club, which was founded in 1877, was a group of the city's most influential leaders that included Marshall Field

Marshall Field (August 18, 1834January 16, 1906) was an American entrepreneur and the founder of Marshall Field's, Marshall Field and Company, the Chicago-based department stores. His business was renowned for its then-exceptional level of qua ...

, George Pullman

George Mortimer Pullman (March 3, 1831 – October 19, 1897) was an American engineer and industrialist. He designed and manufactured the Pullman (car or coach), Pullman sleeping car and founded a Pullman, Chicago, company town in Chicago for t ...

, Edson Keith, Cyrus McCormick

Cyrus Hall McCormick (February 15, 1809 – May 13, 1884) was an American inventor and businessman who founded the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company, which became part of the International Harvester Company in 1902. Originally from the Blue ...

and George Armour

George Armour (24 April 1812 – 13 June 1881) was a Scottish American businessman and philanthropist known for his contributions to the global distribution process for commodities. He was credited with developing the grain elevator system, es ...

. The club's successor, The Commercial Club of Chicago

The Commercial Club of Chicago is a nonprofit 501(c)(4) social welfare organization founded in 1877 with a mission to promote the social and economic vitality of the metropolitan area of Chicago.

History

The Commercial Club was founded in 187 ...

would later sponsor Daniel Burnham

Daniel Hudson Burnham (September 4, 1846 – June 1, 1912) was an American architect and urban designer. A proponent of the ''Beaux-Arts architecture, Beaux-Arts'' movement, he may have been "the most successful power broker the American archi ...

and Edward H. Bennett

Edward Herbert Bennett (1874–1954) was an architect and city planner best known for his co-authorship of the 1909 Plan of Chicago.

Biography

Bennett was born in Bristol, England on May 12, 1874,Plan of Chicago

The Burnham Plan is a popular name for the 1909 ''Plan of Chicago'' coauthored by Daniel Burnham and Edward H. Bennett and published in 1909. It recommended an integrated series of projects including new and widened streets, parks, new railr ...

'' (1909), which is widely regarded as one of the most important public planning documents ever created.

Chicago Manual Training School was a private secondary school and was designed to graduate its students three years from the time they entered. The student body, which was all male, was required to spend an hour each day in the drafting room and two hours a day in the shop, in addition to the time spent in classrooms studying the conventional high school curriculum. In 1891 the tuition averaged $100.00 per year "to those able to pay it". In 1903 the institution became part of the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools, operating out of CMTS (later Belfield) Hall.Although it was to take him in a totally different direction, Chicago Manual Training School, with its focus on the industrial arts, was a logical choice for the secondary education of the oldest son of a hardware dealer, especially in an age when primogeniture was considered important. Besides his classes in drawing Seyfarth studied mathematics, English, French, Latin, history, physics, chemistry, foundry and forgework, machine shopwork, woodwork, political economy and civil government. He attended classes and graduated in 1895 with the son of Dankmar Adler, the son and the nephew of

Henry Demarest Lloyd

Henry Demarest Lloyd (May 1, 1847 – September 28, 1903) was an American journalist and political activist who was a prominent muckraker during the Progressive Era. He is best known for his exposés of Standard Oil which were written before Ida ...

and with Henry Horner

Henry Horner (November 30, 1878 – October 6, 1940) was an American politician. Horner served as the 28th Governor of Illinois, serving from January 1933 until his death in October 1940. Horner was noted as the first Jewish governor of Illinois. ...

(1878-1940) who was the governor of Illinois from 1933 until the time of his death.Despite the fact that it was 17 miles away, Seyfarth enjoyed the advantage of the school's convenient location. The railway depot that marked the beginning of his trip was a two-block walk from his home at Grove Street and Western Avenue, with the end of the ride being at the Illinois Central's Twelfth Street Station, which was located directly across the stree

from the school

The ride would have taken him directly over the

Midway Plaisance

The Midway Plaisance, known locally as the Midway, is a Chicago parks, public park on the Neighborhoods of Chicago#South side, South Side of Chicago, Illinois. It is one mile long by 220 yards wide and extends along 59th and 60th streets, joini ...

of the World's Columbian Exposition, where he would have a clear view to the west of the great Ferris Wheel

A Ferris wheel (also called a big wheel, giant wheel or an observation wheel) is an amusement ride consisting of a rotating upright wheel with multiple passenger-carrying components (commonly referred to as passenger cars, cabins, tubs, gondola ...

and to the east of the Beaux Arts majesty of the main body of the Fair. It is difficult to imagine that to a boy from small-town America in the early 1890s this would not have created an impression and provided him with enormous inspiration, as it did the architectural world at large for the next forty years. In her book ''A Poet's Life - Seventy Years in a Changing World'', the writer, founder of the magazine Poetry

Poetry (from the Greek language, Greek word ''poiesis'', "making") is a form of literature, literary art that uses aesthetics, aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meaning (linguistics), meanings in addition to, or in ...

and social critic Harriet Monroe

Harriet Monroe (December 23, 1860 – September 26, 1936) was an American editor, scholar, literary critic, poet, and patron of the arts. She was the founding publisher and long-time editor of ''Poetry'' magazine, which she established in 1912 ...

succinctly noted forty-five years after the closing of the Fair that "... like all great achievements of beauty, it has become an incalculably inspiring force which lasted into the next 'age'."

The Chicago Architectural Club

Inland Architect

Inland may refer to:

Places Sweden

* Inland Fräkne Hundred, a hundred of Bohuslän in Sweden

* Inland Northern Hundred, a hundred of Bohuslän in Sweden

* Inland Southern Hundred, a hundred of Bohuslän in Sweden

* Inland Torpe Hundred, a hundred ...

'', whose first issue had been published in February 1883. The club was formed in Chicago during a period when architecture there was in its ascendancy - after the Great Fire of 1871 a large population of some of the country's best architectural talent had come to rebuild a modern city using the most advanced and progressive techniques of the day. Even so, the community was taxed trying to perform all of the work that was necessary to keep up with the task. Chicago was developing at a rate that astounded anyone who was paying attention to its growth, such that "one unfamiliar with the city would find ... fresh subject for astonishment, daily, in John Wellborn Root

John Wellborn Root (January 10, 1850 – January 15, 1891) was an American architect who was based in Chicago with Daniel Burnham. He was one of the founders of the Chicago School style. Two of his buildings have been designated National Hist ...

recalled years later: "The conditions attending the development of architecture in the West have been, in almost every respect, without precedent. At no time in the history of the world has a community covering such vast and yet homogeneous territory developed with such amazing rapidity, and under conditions of civilization so far advanced. Few times in history have ever presented so impressive a sight as this resistless wave of progress, its farthermost verge crushing down primeval obstacles in nature and desperate resistance from the inhabitants; its deeper and calmer waters teeming with life and full of promise more significant than has ever yet been known."The club was an effort to help develop the talents of the city's many draftsmen so that they could become qualified architects themselves, at a time when a formal education for architects was generally unavailable and not required. (The first architectural school in the United States was founded by architect

William Robert Ware

William Robert Ware (May 27, 1832 – June 9, 1915), born in Cambridge, Massachusetts into a family of the Unitarian clergy, was an American architect, author, and founder of two important American architectural schools.

He received his o ...

at MIT

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Established in 1861, MIT has played a significant role in the development of many areas of modern technology and sc ...

in 1868 with nine students, and even by 1896, the year after Seyfarth's graduation, there were only nine schools in the country with a combined student body of 273.) Seyfarth joined during the time he worked for Maher, who over the years was an active member of the club as a speaker, writer, exhibitor and judge in its annual competitions. Seyfarth is known to have entered his work at two of these exhibitions - the first time in 1903 (before he became a member), when his submission was listed as a "Library", and again in 1905, where the subject of the entry was his own house in Blue Island. The preface to the catalogue of the 1905 exhibition was devoted to what the noted architect Elmer Grey

Elmer Grey, FAIA (April 29, 1872 – November 14, 1963) was an Americans, American architect and artist based in Pasadena, California. Grey designed many noted landmarks in Southern California, including the Beverly Hills Hotel, the Huntingto ...

(1872–1963) called "Inventive and Indigeonous Architecture", a phrase which perfectly reflected Seyfarth's design for this particular house and may have been one of the reasons why images of it were included.Because of his association with the Chicago Architectural Club, Seyfarth would have ample opportunity to become acquainted with the major players of Chicago's progressive architectural community, a large number of whom were active members. These were relationships that Maher would doubtless have encouraged. Notables among the list included Charles B. Atwood,

Daniel Burnham

Daniel Hudson Burnham (September 4, 1846 – June 1, 1912) was an American architect and urban designer. A proponent of the ''Beaux-Arts architecture, Beaux-Arts'' movement, he may have been "the most successful power broker the American archi ...

, Dankmar Adler

Dankmar Adler (July 3, 1844 – April 16, 1900) was a German-born American architect and civil engineer. He is best known for his fifteen-year partnership with Louis Sullivan, during which they designed influential skyscrapers that boldly addr ...

, Louis Sullivan

Louis Henry Sullivan (September 3, 1856 – April 14, 1924) was an American architect, and has been called a "father of skyscrapers" and "father of modernism". He was an influential architect of the Chicago school (architecture), Chicago ...

, Howard Van Doren Shaw

Howard Van Doren Shaw American Institute of Architects, AIA (May 7, 1869 – May 7, 1926) was an architect in Chicago, Illinois. Shaw was a leader in the American Craftsman movement, best exemplified in his 1900 remodel of Second Presbyteria ...

, William Le Baron Jenney

William Le Baron Jenney (September 25, 1832 – June 14, 1907) was an American architect and engineer known for building the first skyscraper in 1884.

In 1998, Jenney was ranked number 89 in the book ''1,000 Years, 1,000 People: Ranking th ...

and Frank Lloyd Wright. The club's headquarters for many years was located in the former mansion of the piano manufacturer William W. Kimball at 1801 Prairie Ave. in Chicago. It ceased to operate as an active organization in 1940 and was dissolved in 1967, but exists again today after it was re-formed in 1979.

Influences and early career

Robert Seyfarth graduated from the Chicago Manual Training School in 1895, and literature published by the school shows his position upon graduation to be that of a "Draughtsman" for the Chicago architect August Fiedler. Fiedler was born in Germany and came to the United States in 1869, establishing himself first in New York City and then in Chicago as a much sought-after designer of high-end residential interiors, later becoming an architect. He designed some of the woodwork and other decoration for the Samuel Nickerson House (1879–1883) on Erie Street in Chicago (now the Driehaus Museum), and the interiors of the

Robert Seyfarth graduated from the Chicago Manual Training School in 1895, and literature published by the school shows his position upon graduation to be that of a "Draughtsman" for the Chicago architect August Fiedler. Fiedler was born in Germany and came to the United States in 1869, establishing himself first in New York City and then in Chicago as a much sought-after designer of high-end residential interiors, later becoming an architect. He designed some of the woodwork and other decoration for the Samuel Nickerson House (1879–1883) on Erie Street in Chicago (now the Driehaus Museum), and the interiors of the Hegeler Carus Mansion

The Hegeler Carus Mansion, located at 1307 Seventh Street in La Salle, Illinois is one of the Midwest's great Second Empire structures. Completed in 1876 for Edward C. Hegeler, a partner in the nearby Matthiessen Hegeler Zinc Company, the man ...

( William W. Boyington,1874–1876) in LaSalle, Illinois

LaSalle or La Salle is a city in LaSalle County, Illinois, United States, located at the intersection of Interstates 39 and 80. It is part of the Ottawa, IL Micropolitan Statistical Area. Originally platted in 1837 over , the city's boundaries ...

. In an 1881 letter to a colleague, one of Fiedler's contemporaries commented on the quality of Fiedler's design work for Nickerson by saying that "...it would be hard to comprehend its beauty without seeing it". From 1893 to 1896 he was the chief architect for the Board of Education for the city of Chicago (being the first to assume the position upon the creation of the building department on January 18, 1893), for whom he designed and/or supervised the construction of fifty-eight school buildings, and he was responsible for the design of thirty-eight buildings (thirty-six in the German Village alone

) at the World's Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition, also known as the Chicago World's Fair, was a world's fair held in Chicago from May 5 to October 31, 1893, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492. The ...

. Seyfarth began his career as an architect at the age of 17 working for Fiedler during the time the latter was architect to the board of education, and records show his position at the time he was hired to be "messenger" (although, as noted above, his graduation notice suggested something more than that), for which he was compensated with a salary of $6.00 per week (about $219.76 in 2023). Fiedler operated out of offices in Adler and Sullivan's Schiller (later Garrick Theater) Building (1891, demolished 1961), and Seyfarth was almost certainly introduced to him through his uncle Henry Biroth, who was one of the earliest pharmacists in Chicago and served at various times as the secretary and president of the Illinois Pharmaceutical Association, which occupied offices down the hall from Fiedler. The Seyfarth family had been acquainted with Fiedler for several years before Seyfarth began to attend Chicago Manual Training School. Henry Biroth was an active member of Chicago's large ethnic German community, and in 1887, Fiedler (with his partner John Addison) had designed a house for him in Blue Island. How long the young Seyfarth worked for Fiedler and the board of education is not known (Fiedler separated from the board of education late in 1896, and was replaced by Normand Patton), but by 1900 he was working for George Washington Maher

George Washington Maher (December 25, 1864 – September 12, 1926) was an American architect during the first quarter of the 20th century. He is considered part of the Prairie School-style and was known for blending traditional architecture wit ...

on the renovation of the interior of the Nickerson mansion for Lucius Fisher. Here, according to the Historic American Buildings Survey

The asterisk ( ), from Late Latin , from Ancient Greek , , "little star", is a Typography, typographical symbol. It is so called because it resembles a conventional image of a star (heraldry), heraldic star.

Computer scientists and Mathematici ...

, he designed and carved the woodwork for the rare book room. Maher was an influential architect associated with the

Prairie School

Prairie School is a late 19th and early 20th-century architectural style, most common in the Midwestern United States. The style is usually marked by horizontal lines, flat or hipped roofs with broad overhanging eaves, windows grouped i ...

movement. According to H. Allen Brooks, professor emeritus of fine arts at the University of Toronto

The University of Toronto (UToronto or U of T) is a public university, public research university whose main campus is located on the grounds that surround Queen's Park (Toronto), Queen's Park in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It was founded by ...

"His influence on the Midwest was profound and prolonged and, in its time, was certainly as great as was Mill Creek, West Virginia

Mill Creek is a town in Randolph County, West Virginia, United States, along the Tygart Valley River. The population was 563 at the 2020 census.

The town takes its name from nearby Mill Creek.

Geography

Mill Creek is located at (38.731748, - ...

, and at about the age of five, due to the adverse economic conditions in Mill Creek at the time, his family moved to New Albany, Indiana

New Albany is a city in New Albany Township, Floyd County, Indiana, United States, situated along the Ohio River, opposite Louisville, Kentucky. The population was 37,841 as of the 2020 census. The city is the county seat of Floyd County. It ...

. There Maher attended primary school, but by the time he was in his early teens the family was on the move again, this time to Chicago. They went there to take advantage of the prosperity that had come to the city after the Great Fire of 1871, and in 1878 George was sent to apprentice with the Chicago architect Augustus Bauer (after 1881 in partnership with Henry Hill who, with Arthur Woltersdorf would build St. Benedict Church in Blue Island in 1895) by his parents who, as was not unusual at the time, needed to augment the family income with the earnings that this type of employment would provide.

As history would show, this turn of events proved to be fortunate for Maher. Bauer was considered to be one among "the city's prominent social and cultural arbiters." He had come to the United States in 1853 having been a part of the wave of German immigration that had brought Robert Seyfarth's grandfather to the United States, and he and his various partners, who were also of German extraction, played an important role in providing architectural services for the large German community in Chicago during the second half of the 19th century. In 1869 Bauer designed the first German school in Chicago at 1352 S. Union Street for Zion Lutheran Church, and in 1872-73 Bauer and Löebnitz designed Concert Hall, Chicago Turngemeinde (demolished) at Clark Street and Chicago Avenue. The output of the Bauer partnerships included many distinguished projects, including Old St. Patrick's Church at 700 W. Adams Street (1856, renovated and restored 1992-1999, which ''Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

'' magazine ranked among the 40 most important buildings in Chicago ), the Rosenberg Fountain in Grant Park (dedicated October 16, 1893, restored 2004), and Tree Studios at 601-623 N. State Street (1894–1913, with Parfitt Brothers, renovated 2004). Bauer is credited with the invention of the isolated footing foundation system, which allows for a longer span between vertical supports. This innovation among other things permits the broad expanses of glass that have become a standard feature of modern architecture. Maher was not Bauer's only notable protégé - at the beginning of the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

and again at the end of it, Bauer employed Dankmar Adler

Dankmar Adler (July 3, 1844 – April 16, 1900) was a German-born American architect and civil engineer. He is best known for his fifteen-year partnership with Louis Sullivan, during which they designed influential skyscrapers that boldly addr ...

(1844–1900), who would later work with Louis Sullivan

Louis Henry Sullivan (September 3, 1856 – April 14, 1924) was an American architect, and has been called a "father of skyscrapers" and "father of modernism". He was an influential architect of the Chicago school (architecture), Chicago ...

on buildings that would come to be regarded as important contributions to the Chicago School of architecture, notably the Chicago Stock Exchange Building (1893, demolished 1972) and the Auditorium Building

The Auditorium Building is a structure at the northwest corner of South Michigan Avenue (Chicago), Michigan Avenue and Ida B. Wells Drive in the Chicago Loop, Loop community area of Chicago, Illinois, United States. Completed in 1889, it is o ...

(1889) (now the home of Roosevelt University

Roosevelt University is a private university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Founded in 1945, the university was named in honor of United States President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. The university enrolls arou ...

).How long Maher worked for Bauer and his partners is not known, but by the 1880s he was working in the office of

Joseph Lyman Silsbee

Joseph Lyman Silsbee (November 25, 1848 – January 31, 1913) was a significant American architect during the 19th and early 20th centuries. He was well known for his facility of drawing and gift for designing buildings in a variety of styles. His ...

, who before he became an architect had been professor of architecture at the new College of Fine Arts at Syracuse University

Syracuse University (informally 'Cuse or SU) is a Private university, private research university in Syracuse, New York, United States. It was established in 1870 with roots in the Methodist Episcopal Church but has been nonsectarian since 1920 ...

. Silsbee was a talented architect who designed in the latest architectural fashion. He was noted for his Shingle style

The shingle style is an American architectural style made popular by the rise of the New England school of architecture, which eschewed the highly ornamented patterns of the Eastlake style in Queen Anne architecture. In the shingle style, Engli ...

buildings and "... was a master of the Queen Anne style, and in gaining the romantic effect admired by his clients he depended less upon Palmer

Palmer may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Palmer (pilgrim), a medieval European pilgrim to the Holy Land

* Palmer (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Palmer (surname), including a list of people and f ...

's fantastic castle

A castle is a type of fortification, fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by Military order (monastic society), military orders. Scholars usually consider a ''castle'' to be the private ...

at 1350 N. Lake Shore Drive (built 1881-1885, demolished 1950, Henry Ives Cobb

Henry Ives Cobb (August 19, 1859 – March 27, 1931) was an architect from the United States. Based in Chicago in the last decades of the 19th century, he was known for his designs in the Richardsonian Romanesque and Gothic revival, Victori ...

(1859–1931) and Charles Sumner Frost

Charles Sumner Frost (May 31, 1856 – December 11, 1931) was an American architect. He is best known as the architect of Navy Pier and for designing over 100 buildings for the Chicago and North Western Railway.

Biography

Born in Lewiston, Main ...

(1856–1931) architects), and stayed to design several important projects for the city, including the Lincoln Park Conservatory

The Lincoln Park Conservatory (1.2 ha / 3 acres) is a conservatory and botanical garden in Lincoln Park in Chicago, Illinois. The conservatory is located at 2391 North Stockton Drive just south of Fullerton Avenue, west of Lake Shore Drive, and ...

(1890–1895) and the West Virginia Building and the Moving Sidewalk for the World's Columbian Exposition (1893). While he worked for Silsbee, Maher worked alongside George Grant Elmslie

George Grant Elmslie (February 20, 1869 – April 23, 1952) was an American Prairie School architect whose works are is mostly found in the Midwestern United States. He worked with Louis Sullivan and later with William Gray Purcell as a partne ...

(1869–1952), Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright Sr. (June 8, 1867 – April 9, 1959) was an American architect, designer, writer, and educator. He designed List of Frank Lloyd Wright works, more than 1,000 structures over a creative period of 70 years. Wright played a key ...

(1867–1959) and Irving Gill

Irving John Gill (April 26, 1870 – October 7, 1936), was an American architect, known professionally as Irving J. Gill. He did most of his work in Southern California, especially in San Diego and Los Angeles. He is considered a pioneer of the ...

(1870–1936), who would each later become prominent architects, although with decidedly different architectural styles. In 1888 Maher established his own office with Charles Corwin, a relationship that lasted until about 1893. He briefly enjoyed a professional relationship with Northwestern University in Evanstion, Illinois, where in 1909 (during Seyfarth's tenure in his office) he designed Swift Hall and the first Patten Gymnasium (demolished 1940). These buildings were bold expressions of his unique design philosophy and were to have been integral parts of his master plan for the campus, which the board of trustees had commissioned through a competition in 1911 but failed to execute. This prompted one commentator in later years to lament "It's probably the most regrettable loss in Northwestern architectural history: the unique Prairie School campus that never was". Frank Lloyd Wright would have predicted the outcome. What follows is point 13 in his list of advice given "To the young man in architecture": "Enter no Architectural competition under any circumstances except as a novice. No competition ever gave to the world anything worth having in Architecture. The jury itself is a picked average. The first thing done by the jury is to go through all the designs and throw out the best and the worst ones so as an average, it can average upon an average. The net result of any competition is an average by the average of averages.".

Toward the end of his life, when he was chairman of the Municipal Arts and Town Planning Committee of the Illinois Chapter of the

American Institute of Architects

The American Institute of Architects (AIA) is a professional organization for architects in the United States. It is headquartered in Washington, D.C. AIA offers education, government advocacy, community redevelopment, and public outreach progr ...

, Maher became the driving force behind the restoration of the former Palace of Fine Arts, then a crumbling ruin which was by then the only major building that remained from the World's Columbian Exposition. In an article that appeared in ''The American Architect'' in 1921, Maher made the following observation, which indicates a predilection for classical architecture despite the conclusion one might otherwise come to upon examining his existing body of work: "For slightly over a million and a half dollars, Chicago could have, in perpetuity, one of the most beautiful specimens of architecture in the world ... It is universally agreed among architects, artists and critics, that the building is unequalled as a pure example of classical architecture. It is the last remaining memorial of one of Chicago's greatest achievements, the Columbian exposition." Maher didn't live to see what he had begun come to fruition, but during the Century of Progress

A Century of Progress International Exposition, also known as the Chicago World's Fair, was a world's fair held in the city of Chicago, Illinois, United States, from 1933 to 1934. The fair, registered under the Bureau International des Exposit ...

in 1933 the Museum of Science and Industry opened in the newly restored building, a project which was funded largely with a $5 million gift from the philanthropist Julius Rosenwald

Julius Rosenwald (August 12, 1862 – January 6, 1932) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He is best known as a part-owner and leader of Sears, Roebuck and Company, and for establishing the Rosenwald Fund, which donated millions i ...

(1862–1932), who was president of Sears, Roebuck and Company

Sears, Roebuck and Co., commonly known as Sears ( ), is an American chain of department stores and online retailer founded in 1892 by Richard Warren Sears and Alvah Curtis Roebuck and reincorporated in 1906 by Richard Sears and Julius Rosen ...

. It is likely that Robert Seyfarth was introduced to Maher through family connections. Because Edward Seyfarth was an important local businessman, he would almost certainly have been familiar with the established architect's work that was being built in Blue Island.

Independent practice

Seyfarth earned his architectural license from the state of Illinois in October 1908 and continued to work for Maher until about 1909, at which time he opened his own practice. In the early years the office was located in the Corn Exchange Bank Building (1908,

Shepley, Rutan, and Coolidge

Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge was a successful American architectural firm based in Boston. As the successor to the studio of Henry Hobson Richardson, they completed his unfinished work before developing their own practice, and had extensive commissi ...

, demolished 1985) at 134 S. LaSalle Street, which was a short walk from the Chicago Stock Exchange Building. Seyfarth was likely drawn to establish his office there thru the influence of his Blue Island neighbor Benjamin C. Sammons (1866-1916), who was the president of the Bankers Club of Chicago and a long-time vice-president of the Corn Exchange National Bank. Seyfarth later moved into the newly completed Tribune Tower

The Tribune Tower is a , 36-floor Gothic Revival architecture, neo-Gothic skyscraper located at 435 Magnificent Mile, North Michigan Avenue in Chicago, Illinois, United States. The early 1920s international design competition for the tower bec ...

(1925, John Mead Howells

John Mead Howells ( ; August 14, 1868 – September 22, 1959) was an American architect.

Early life and education

Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the son of author William Dean Howells, he earned an undergraduate degree from Harvard Univ ...

and Raymond Hood

Raymond Mathewson Hood (March 29, 1881 – August 14, 1934) was an American architect who worked in the Gothic Revival architecture, Neo-Gothic and Art Deco styles. He is best known for his designs of the Tribune Tower, American Radiator Building ...

), where he had an office on the twenty-first floor until 1934 when the Depression forced the move of his business to his home in the North Shore community of Highland Park. His was a small office - he did the design, drafting and supervision work himself, and for many years was assisted by Miss Eldridge, who typed specifications and generally kept the office running. After the office was moved to his home, he took as his assistant Edward Humrich (1901–1991), who himself became a noted architect after he left Seyfarth's employ shortly before the advent of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Humrich enjoyed a distinguished career designing and building houses in the Usonian

Usonia () is a term that was used by the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright to refer to the United States in general (in preference over ''America''), and more specifically to his vision for the landscape of the country, including the planni ...

style of Frank Lloyd Wright. He earned his architectural license in 1968. In a series of interviews with the Art Institute of Chicago

The Art Institute of Chicago, founded in 1879, is one of the oldest and largest art museums in the United States. The museum is based in the Art Institute of Chicago Building in Chicago's Grant Park (Chicago), Grant Park. Its collection, stewa ...

in 1986, he summed up Seyfarth's appeal: "He had an excellent sense of proportion and scale. His houses were all true to the North Shore ..., and they're outstanding. He had a knack, kind of a freshness to it, and it was good."In 1911 Robert Seyfarth designed and built a

gambrel

A gambrel or gambrel roof is a usually symmetrical two-sided roof with two slopes on each side. The upper slope is positioned at a shallow angle, while the lower slope is steep. This design provides the advantages of a sloped roof while maxim ...

roofed Shingle Style

The shingle style is an American architectural style made popular by the rise of the New England school of architecture, which eschewed the highly ornamented patterns of the Eastlake style in Queen Anne architecture. In the shingle style, Engli ...

house for his family on Sheridan Road

Sheridan Road is a major north-south street that leads from Diversey Parkway (Chicago), Diversey Parkway in Chicago, Illinois, north to the Illinois-Wisconsin border and beyond to Racine, Wisconsin, Racine. Throughout most of its run, it is the ...

in Highland Park, across the street from Frank Lloyd Wright's Ward Willets house (1901), and it marked a change in the direction of his design work - for the rest of his career his would design in an eclectic style combining Colonial Revival

The Colonial Revival architectural style seeks to revive elements of American colonial architecture.

The beginnings of the Colonial Revival style are often attributed to the Centennial Exhibition of 1876, which reawakened Americans to the arch ...

, Tudor and Continental Provincial elements with strong geometric forms. During his career Seyfarth would design 73 houses in Highland Park alone, where his output began before the time of his arrival as a resident and lasted until shortly before his death. Here he elected to ignore the notion that in later years was famously offered to young architects by the Sage of Taliesin

Taliesin ( , ; 6th century AD) was an early Britons (Celtic people), Brittonic poet of Sub-Roman Britain whose work has possibly survived in a Middle Welsh manuscript, the ''Book of Taliesin''. Taliesin was a renowned bard who is believed to ...

"... go as far away as possible from home to build your first buildings. The physician can bury his mistakes—but the Architect can only advise his client to plant vines.". Almost exclusively a residential architect with the majority of his work in the Chicago area, he also designed projects in Michigan

Michigan ( ) is a peninsular U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, Upper Midwestern United States. It shares water and land boundaries with Minnesota to the northwest, Wisconsin to the west, ...

, Wisconsin

Wisconsin ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest of the United States. It borders Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake Michigan to the east, Michig ...

, Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

, Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

and Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

. By the end of his career, he had designed over two hundred houses.

One of his more important works is the Samuel Holmes House designed in 1926 and listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government's official United States National Register of Historic Places listings, list of sites, buildings, structures, Hist ...

. A shingle style

The shingle style is an American architectural style made popular by the rise of the New England school of architecture, which eschewed the highly ornamented patterns of the Eastlake style in Queen Anne architecture. In the shingle style, Engli ...

house overlooking Lake Michigan

Lake Michigan ( ) is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is the second-largest of the Great Lakes by volume () and depth () after Lake Superior and the third-largest by surface area (), after Lake Superior and Lake Huron. To the ...

, its landscaping was designed by Jens Jensen.

Robert Seyfarth continued to live and work in Highland Park until his death on March 1, 1950.

The Chicago History Museum

Chicago History Museum is the museum of the Chicago Historical Society (CHS). The CHS was founded in 1856 to study and interpret Chicago's history. The museum has been located in Lincoln Park since the 1930s at 1601 North Clark Street (Chicago) ...

Research Center has an archive consisting of drawings for 70 of Seyfarth's projects dating after 1932.

Client base

Seyfarth is sometimes considered to be a "society architect", and an examination of the body of his known work will bear this out, but only to a certain extent. One client of this class, Willoughby G. Walling (1878–1938), of Winnetka, IL, is known to have mingled with Europeanroyalty

Royalty may refer to:

* the mystique/prestige bestowed upon monarchs

** one or more monarchs, such as kings, queens, emperors, empresses, princes, princesses, etc.

*** royal family, the immediate family of a king or queen-regnant, and sometimes h ...

and with at least one President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

in his capacity as the acting director general of the Department of Civilian Relief and as Vice-Chairman of the Central Committee of the American Red Cross

The American National Red Cross is a Nonprofit organization, nonprofit Humanitarianism, humanitarian organization that provides emergency assistance, disaster relief, and disaster preparedness education in the United States. Clara Barton founded ...

. His brother William English Walling

William English Walling (March 18, 1877 – September 12, 1936) ...

was recognized by W.E.B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relativel ...

as the founder of the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

, and Willoughby himself "...became a major spokesman for the Chicago movement". Here he worked alongside the noted social reformer Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860May 21, 1935) was an American Settlement movement, settlement activist, Social reform, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, philosopher, and author. She was a leader in the history of s ...

and some of Chicago's wealthiest and most influential citizens, including Mrs. Cyrus McCormick, Mrs. Emmons Blaine hose father-in-law James G. Blaine was variously a United States Senator">Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or Legislative chamber, chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the Ancient Rome, ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior ... Other wealthy clients exported Seyfarth's talents when they built houses outside the Chicago area. Norman W. Harris (of Chicago's

Other wealthy clients exported Seyfarth's talents when they built houses outside the Chicago area. Norman W. Harris (of Chicago's Harris Bank

BMO Bank, N.A. (colloquially BMO; ) is a U.S. national bank headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. It is a subsidiary of the Canadian multinational investment bank and financial services company Bank of Montreal, which owns it through the holding ...

), whose intown residence was also in Winnetka, raised Arabian horses at Kemah Farm in Williams Bay, Wisconsin

Williams Bay is a village in Walworth County, Wisconsin, United States. It is one of three municipalities on Geneva Lake. The population was 2,953 at the 2020 census. On June 22, 2024 the town was hit by an EF-1 tornado, there were no injuri ...

where his family lived in a "white cottage ..., one of the charming, low, rambling houses for which Robert Seyfarth, its architect, is famous.". Another such client was Jessie Sykes Beardsley, who returned to her husband's farm in Freedom Township near Ravenna, Ohio

Ravenna is a city in Portage County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. The population was 11,323 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. It is located east of Akron, Ohio, Akron. Formed from portions of Ravenna Township, Portage Co ...

in 1918 the year after his death and built a large house (locally known as the Manor House) which was designed by Seyfarth that she had commissioned, presumably while she was still in Chicago. Here she operated the Beardsley Dairy for a number of years. Her husband Orasmus Drake Beardsley had been the secretary and treasurer of her father's Chicago-based company, The Sykes Steel Roofing Company, which made a variety of products including roofing materials and pool tables. While there, according to the 1908 edition of ''The Chicago Blue Book of Selected Names'', the Beardsleys lived at 4325 Grand Boulevard (now King Drive) on a street that today contains one of the most intact collections of residences built in the late 19th century for Chicago's elite. The same book also shows that Orasmus Beardsley was a member of various prestigious clubs, including The Chicago Athletic Association (where William Wrigley Jr.

William Mills Wrigley Jr. (September 30, 1861 – January 26, 1932) was an American chewing gum industrialist. He founded the Wm. Wrigley Jr. Company in 1891.

Biography

William Mills Wrigley Jr. was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvani ...

and L. Frank Baum

Lyman Frank Baum (; May 15, 1856 – May 6, 1919) was an American author best known for his children's fantasy books, particularly '' The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'', part of a series. In addition to the 14 ''Oz'' books, Baum penned 41 other novels ...

were members) and the South Shore Country Club (now the South Shore Cultural Center

The South Shore Cultural Center, in Chicago, Illinois, is a cultural facility located at 71st Street and South Shore Drive, in the city's South Shore neighborhood. It encompasses the club facility, grounds, and beach of the former South Shore C ...

), where he associated with the likes of Clarence Buckingham, John G. Shedd, John J. Glessner, Martin Ryerson, Clarence Darrow

Clarence Seward Darrow (; April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was an American lawyer who became famous in the 19th century for high-profile representations of trade union causes, and in the 20th century for several criminal matters, including the ...

, Joy Morton

Joy Sterling Morton (September 27, 1855 – May 10, 1934) was an American businessman and entrepreneur best known for founding Morton Salt and establishing the Morton Arboretum in Lisle, Illinois.

Biography

Morton was born on September 27, 1855, ...

and Willoughby Walling. The Beardsley's Freedom Township house was later owned by Ohio State Senator James P. Jones. Another among Seyfarth's clients of this type was the mail-order innovator Aaron Montgomery Ward

Aaron Montgomery Ward (February 17, 1843 – December 7, 1913) was an American entrepreneur based in Chicago who made his fortune through the use of mail order for retail sales of general merchandise to rural customers. In 1872 he founded Montg ...

(1843–1913), who was briefly a neighbor after Seyfarth moved to Highland Park c. 1910. All of this notwithstanding, however, a careful analysis will show that Seyfarth served a broad-based clientele, and although he has a number of small houses to his credit the largest percentage of his work was done for what would be considered upper middle-class

In sociology, the upper middle class is the social group constituted by higher status members of the middle class. This is in contrast to the term ''lower middle class'', which is used for the group at the opposite end of the middle-class strat ...

clients.

Marketing

Glencoe, Illinois

Glencoe () is a lakefront village in northeastern Cook County, Illinois, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 8,849. Glencoe is part of Chicago's North Shore and one of the wealthiest communities in Illinois. According to t ...

) and Herbert Croly

Herbert David Croly (January 23, 1869 – May 17, 1930) was an intellectual leader of the progressive movement as an editor, political philosopher and a co-founder of the magazine ''The New Republic'' in early twentieth-century America. His polit ...

of the ''Architectural Record

''Architectural Record'' is a US-based monthly magazine dedicated to architecture and interior design. Its editor in chief is Josephine Minutillo. ''The Record'', as it is sometimes colloquially referred to, is widely-recognized as an important ...

'' ("The Local Feeling in Western Country Houses", October, 1914, which discusses the Kozminski and McBride houses in Highland Park at 521 Sheridan Road and 2130 Linden, respectively) survive to give us some idea of how Seyfarth's work was received during the time he was practicing. (Croly would later go on to become the founding editor of ''The New Republic

''The New Republic'' (often abbreviated as ''TNR'') is an American magazine focused on domestic politics, news, culture, and the arts from a left-wing perspective. It publishes ten print magazines a year and a daily online platform. ''The New Y ...

'' magazine.) Additionally, photographs of houses he designed appeared in ''The Western Architect'' magazine a number of times in the 1920s. Also surviving are copies of advertisements from the Arkansas Soft Pine Bureau (see image, right), the California Redwood Association (again with the McBride House), the Pacific Lumber Company (featuring the Churchill house in Highland Park at 1375 Sheridan Road), The Creo-Dipt Company (see image, left), the White Pine Bureau, the American Face Brick Association and the Stewart Iron Works Company of Cincinnati (with a picture of the H. C. Dickinson house at 7150 S. Yale in Chicago). In 1908, his Prairie-style house for Dickinson was published in ''House Beautiful

''House Beautiful'' is an interior decorating magazine that focuses on decorating and the domestic arts. First published in 1896, it is currently published by the Hearst Corporation, who began publishing it in 1934. It is the oldest still-publi ...

'' magazine. In 1918, the Arkansas Soft Pine Bureau released a 32 page portfolio featuring houses built from Seyfarth's designs. Included were photographs, floor plans, bills of material, an estimate of the costs, and a brief description of important features. Entitled ''The Home You Longed For'', the booklet was announced in ''Building Age Magazine'' under the heading "New Catalogs of Interest to the Trade". Although generally unavailable today, it must have enjoyed a wide circulation in its time. It was acquired the following year for the collection of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

The Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh is the public library system in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Its main branch is located in the Oakland neighborhood of Pittsburgh, and it has 19 branch locations throughout the city. Like hundreds of other Carne ...

, and referred to that same year in an illustrated article that appeared in ''Printers' Ink Monthly'' entitled "The Loose-Leaf Portfolio - an Aid to Reader Interest", where it was described as "...a very attractive loose-leaf portfolio" and as a successful example of its type of publication. The last known example of Seyfarth's work to be published during his lifetime appeared in the September, 1948 edition of ''Good Housekeeping'' magazine. The "Little Classic" was an expandable ranch that the magazine had commissioned which it noted featured "...a cornice

hat

A hat is a Headgear, head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorpor ...

is pure sculpture - no jackscrews of mingled mouldings oconfuse its clean profile." The illustrated article also pointed out that "...the porch at the head of the garden is reached through paired French doors from both the living and dining rooms." - even in this late example of Seyfarth's work the abstracted design and covered exterior living space continued to be important elements of the composition.With a long history of having his work published, Seyfarth was following the example of George Washington Maher, who was widely published during his career. Articles by Maher and about him appeared regularly in publications that included ''Western Architect'', ''Inland Architect'', ''Architectural Record'' and ''Arts and Decoration''.

Selected projects

Greater Grand Crossing, Chicago

Greater Grand Crossing is one of the 77 community areas of Chicago, Illinois. It is located on the city's South Side.

History

Etymology

The name "Grand Crossing" comes from an 1853 right-of-way feud between the Lake Shore and Michigan Sout ...

, 1908

File:Bullard House Maywood.JPG, 4. Kenneth Bullard House, 218 N. 2nd Ave., Maywood, Illinois

Maywood is a village in Cook County, Illinois, United States, in the Chicago metropolitan area. It was founded on April 6, 1869, and organized October 22, 1881. The population was 23,512 at the 2020 census.

History

There was limited European-Am ...

, c.1908

File:10400 Seeley.jpg, 5. H.S. Crane house - 10400 S. Seeley Ave., Beverly Hills

Beverly Hills is a city located in Los Angeles County, California, United States. A notable and historic suburb of Los Angeles, it is located just southwest of the Hollywood Hills, approximately northwest of downtown Los Angeles. Beverly Hil ...

, Chicago, 1909

File:Maurice Kozminski house - 521 sheridan.jpg, 6. Maurice Kozminski house - 521 Sheridan Road, Highland Park, Illinois, c.1909

File:Robert Seyfarth House two.JPG, 7. The second Robert Seyfarth house - 1498 Sheridan Road, Highland Park, Illinois, c.1910

File:4840 S. Woodlawn.JPG, 8. Daniel and Maude Eisendrath house - 4840 S. Woodlawn Ave., Kenwood, Chicago

Kenwood, one of Chicago's 77 community areas, is on the shore of Lake Michigan on the South Side of the city. Its boundaries are 43rd Street, 51st Street, Cottage Grove Avenue, and the lake. Kenwood was originally part of Hyde Park Township, ...

, 1910

File:10451 S Seeley Ave Thomason House-1-.jpg, 9. Samuel E. Thomason house - 10451 S. Seeley Ave., Beverly Hills, Chicago, 1910

File:1442 Forest Ave Highland Park Stewart House.JPG, 10. Alexander Stewart house - 1442 Forest Ave., Highland Park, Illinois, 1913

File:Seyfarth 2064 Pratt.jpg, 11. William J. McDonald house - 2064 W. Pratt Blvd., West Ridge, Chicago

West Ridge is one of 77 Chicago community areas. It is a middle-class neighborhood located on the far North Side of the City of Chicago. It is located in the 50th ward and the 40th ward.

Today West Ridge is one of Chicago's better off communi ...

, 1914

File:Lawrence Howe House Winnetka.jpg, 12. Lawrence Howe house - 175 Chestnut St., Winnetka, Illinois

Winnetka () is a village in Cook County, Illinois, United States, north of downtown Chicago. The population was 12,475 as of the 2020 census. The village is one of the wealthiest places in the United States in terms of household income. It was ...

c.1916

File:700 Greenwood Ave., Wilmette.JPG, 13. 700 Greenwood Ave., Wilmette, Illinois

Wilmette is a village in Cook County, Illinois, United States. Bordering Lake Michigan, Kenilworth, Winnetka, Skokie, Northfield, Glenview, and Evanston, Illinois, it is located north of Chicago's downtown district. Wilmette had a populatio ...

, c. 1926

File:Abel Davis House 600 Sheridan Glencoe.jpg, 14. Abel Davis house - 600 Sheridan Road, Glencoe, Illinois, c. 1926

File:145 Montgomery Glencoe.jpg, 15. Mayfield house - 145 Montgomery St., Glencoe, Illinois

Glencoe () is a lakefront village in northeastern Cook County, Illinois, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 8,849. Glencoe is part of Chicago's North Shore and one of the wealthiest communities in Illinois. According to t ...

, c. 1926

File:E Gifford Upjohn house - 2230 Glenwood.jpg, 16. E. Gifford Upjohn

The Upjohn Company was an American pharmaceutical manufacturing firm (est. 1886) in Hastings, Michigan, by Dr. William E. Upjohn, an 1875 graduate of the University of Michigan medical school. The company was originally formed to make ''friable ...

house - 2230 Glenwood, Kalamazoo, Michigan

Kalamazoo ( ) is a city in Kalamazoo County, Michigan, United States, and its county seat. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, Kalamazoo had a population of 73,598. It is the principal city of the Kalamazoo–Portage metropolitan are ...

, 1926

File:Krueger Funeral Home.JPG, 17. The Krueger Funeral Home - 13050 S. Greenwood Ave., Blue Island Illinois, 1927

File:Wagstaff House Glencoe.jpg, 18. Wagstaff house - 181 Hawthorn, Glencoe, Illinois, c. 1927

File:Harry Adamson house - 2219 Egandale Rd.jpg, 19. Harry Adamson house - 2219 Egandale Road, Highland Park, Illinois, c.1927

File:20 Maple Hill Road - Aspley House Glencoe.JPG, 20. J.C. Aspley house - 20 Maple Hill Road, Glencoe, Illinois, 1928-1929

File:Arthur Seyfarth House.JPG, '21. Arthur Seyfarth house - 12844 S. Greenwood Ave., Blue Island Illinois, 1929

File:Seyfarth Page House.JPG, 22. Roscoe Page house - 2424 Lincoln St., Evanston, Illinois

Evanston is a city in Cook County, Illinois, United States, situated on the North Shore (Chicago), North Shore along Lake Michigan. A suburb of Chicago, Evanston is north of Chicago Loop, downtown Chicago, bordered by Chicago to the south, Skok ...

, c.1934

File:Freeman House 2418 Lincoln Ave..jpg, 23. Freeman house - 2418 Lincoln St., Evanston, Illinois, 1935

File:700 Fair Oaks Ave.JPG, 24. Ashley Smith house - 700 Fair Oaks Ave., Oak Park, Illinois

Oak Park is a village in Cook County, Illinois, United States, adjacent to Chicago. It is the List of municipalities in Illinois, 26th-most populous municipality in Illinois, with a population of 54,318 as of the 2020 census. Oak Park was first se ...

, c.1938.

File:Seyfarth 2730 Broadway Ave.JPG, 25. Russell E. Q. Johnson house - 2730 Broadway Ave., Evanston, Illinois c. 1949, built 1956

Notes on the pictures

* 1.) The first Robert Seyfarth house. This simple Prairie School house was built while Seyfarth was still working for George Washington Maher. The older architect's influence is clearly evident here, down to the use of a Maher hallmark, the lion's head, which appear here as brackets to "support" the second floorsleeping porch

A sleeping porch is a Deck (building), deck or balcony, sometimes screened or otherwise enclosed with screened windows,Lake Forest College

Lake Forest College is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Lake Forest, Illinois. Founded in 1857 as Lind University by a group of Presbyterian ministers, the college has been coeducatio ...

shows this house with the apertures of the sleeping porch only screened in the manner of the front porch of his second house in Highland Park, suggesting that Seyfarth also intended this building's now-enclosed counterpart on the Ellis house in Beverly to be open to the weather, as was the sleeping porch on the Dickenson house in the Chicago neighborhood of Greater Grand Crossing (see item #2 below). The photo also shows Seyfarth's use of a striated pattern in the shingles on the roof that Maher would use in 1907 on the Henry Schultz house

Henry may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Henry (given name), including lists of people and fictional characters

* Henry (surname)

* Henry, a stage name of François-Louis Henry (1786–1855), French baritone

Arts and entertainment ...

in Winnetka, Illinois and the Kenilworth Club (in Kenilworth, Illinois

Kenilworth is a village in Cook County, Illinois, United States, north of downtown Chicago. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census it had a population of 2,514. It is the newest of the nine suburban North Shore (Chicago), North Shore c ...

), and on occasional other projects over the years.

The house could be a study for the Ernest J. Magerstadt house which Maher built at 4930 S. Greenwood Avenue in the Kenwood neighborhood of Chicago in c.1908. It appeared in the background of establishing shot

An establishing shot in filmmaking and television production sets up, or establishes, the context for a scene by showing the relationship between its important figures and objects. It is generally a long or extreme-long shot at the beginning of ...

s in the 2011 New Line Cinema

New Line Productions, Inc., Trade name, doing business as New Line Cinema, is an American film production, film and television production company that is a subsidiary of Warner Bros. Motion Picture Group, a division of the Major film studios, ...

film '' The Rite'', which starred Anthony Hopkins