Robert Owen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert Owen (; 14 May 1771 – 17 November 1858) was a Welsh textile manufacturer,

To test the viability of his ideas for self-sufficient working communities, Owen began experimenting with communal living in the

To test the viability of his ideas for self-sufficient working communities, Owen began experimenting with communal living in the

*A simple slate tomb for Owen was installed in St Mary's Churchyard in Newtown. In 1902 the co-operative movement erected

*A simple slate tomb for Owen was installed in St Mary's Churchyard in Newtown. In 1902 the co-operative movement erected

philanthropist

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives for the public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private good, focusing on material ...

, political philosopher

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and legitimacy of political institutions, such as states. This field investigates different forms of government, ranging from de ...

and social reformer, and a founder of utopian socialism

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern socialism and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Étienne Cabet, and Robert Owen. Utopian socialism is often de ...

and the co-operative movement. He strove to improve factory working conditions, promoted experimental socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

ic communities, sought a more collective approach to child-rearing, and 'believed in lifelong education, establishing an Institute for the Formation of Character and School for Children that focused less on job skills than on becoming a better person'. He gained wealth in the early 1800s from a textile mill

Textile manufacturing or textile engineering is a major industry. It is largely based on the conversion of fibre into yarn, then yarn into fabric. These are then dyed or printed, fabricated into cloth which is then converted into useful good ...

at New Lanark, Scotland. Having trained as a draper in Stamford, Lincolnshire

Stamford is a market town and civil parish in the South Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England. The population at the 2011 census was 19,701 and estimated at 20,645 in 2019. The town has 17th- and 18th-century stone buildings, older timber ...

he worked in London before relocating at age 18 to Manchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

and textile manufacturing. In 1824, he moved to America and put most of his fortune in an experimental socialistic community at New Harmony, Indiana, as a preliminary for his utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', which describes a fictiona ...

n society. It lasted about two years. Other Owenite communities also failed, and in 1828 Owen returned to London, where he continued to champion the working class

The working class is a subset of employees who are compensated with wage or salary-based contracts, whose exact membership varies from definition to definition. Members of the working class rely primarily upon earnings from wage labour. Most c ...

, lead in developing co-operative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, coöperative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democr ...

s and the trade union movement, and support child labour legislation and free co-educational schools.

Biography

Early life and family

Robert Owen was born in Newtown, a small market town inMontgomeryshire

Montgomeryshire ( ) was Historic counties of Wales, one of the thirteen counties of Wales that existed from 1536 until their abolishment in 1974. It was named after its county town, Montgomery, Powys, Montgomery, which in turn was named after ...

, Wales, on 14 May 1771, to Anne (Williams) and Robert Owen. His father was a saddle

A saddle is a supportive structure for a rider of an animal, fastened to an animal's back by a girth. The most common type is equestrian. However, specialized saddles have been created for oxen, camels and other animals.

It is not know ...

r, ironmonger and local postmaster; his mother was the daughter of a Newtown farming family. Young Robert was the sixth of the family's seven children, two of whom died at a young age. His surviving siblings were William, Anne, John and Richard.

Owen received little formal education, but he was an avid reader. He left school at the age of ten to be an apprentice draper in Stamford, Lincolnshire

Stamford is a market town and civil parish in the South Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England. The population at the 2011 census was 19,701 and estimated at 20,645 in 2019. The town has 17th- and 18th-century stone buildings, older timber ...

, for four years. He also worked in London drapery shops in his teenage years. (online version) At about the age of 18, Owen moved to Manchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

, where he spent the next twelve years of his life, employed initially at Satterfield's Drapery in Saint Ann's Square.

On a visit to Scotland, Owen met and fell in love with Ann (or Anne) Caroline Dale, daughter of David Dale, a Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

philanthropist and the proprietor of the large New Lanark Mills. After their marriage on 30 September 1799, the Owens set up a home in New Lanark, but later moved to Braxfield House in Lanark

Lanark ( ; ; ) is a town in South Lanarkshire, Scotland, located 20 kilometres to the south-east of Hamilton, South Lanarkshire, Hamilton. The town lies on the River Clyde, at its confluence with Mouse Water. In 2016, the town had a populatio ...

.Estabrook, p. 64.

Robert and Caroline Owen had eight children, the first of whom died in infancy. Their seven survivors were four sons and three daughters: Robert Dale (1801–1877), William (1802–1842), Ann (or Anne) Caroline (1805–1831), Jane Dale (1805–1861), David Dale (1807–1860), Richard Dale (1809–1890) and Mary (1810–1832). Owen's four sons, Robert Dale, William, David Dale and Richard, and his daughter Jane Dale, followed their father to the United States, becoming US citizens and permanent residents in New Harmony, Indiana. Owen's wife Caroline and two of their daughters, Anne Caroline and Mary, remained in Britain, where they died in the 1830s.Estabrook, p. 72.Pitzer, "Why New Harmony is World Famous," in ''Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History'', p. 11.

Textile mills

While in Manchester, Owen borrowed £100 from his brother William, to enter into a partnership to make spinning mules, a new invention for spinning cotton threads, but exchanged his business shares within a few months for six spinning mules that he worked in rented factory space. In 1792, when Owen was about 21 years old, mill-owner Peter Drinkwater made him manager of the Piccadilly Mill at Manchester. However, after two years with Drinkwater, Owen voluntarily gave up his contract of partnership and left the company, and went into partnership with other entrepreneurs to establish and later manage the Chorlton Twist Mills inChorlton-on-Medlock

Chorlton-on-Medlock is an inner city area of Manchester, England.

Historic counties of England, Historically in Lancashire, Chorlton-on-Medlock is bordered to the north by the River Medlock, which runs immediately south of Manchester city cen ...

.

By the early 1790s, Owen's entrepreneur

Entrepreneurship is the creation or extraction of economic value in ways that generally entail beyond the minimal amount of risk (assumed by a traditional business), and potentially involving values besides simply economic ones.

An entreprene ...

ial spirit and management skills and progressive moral views were emerging. In 1793, he was elected as a member of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, where the ideas of the Enlightenment were discussed. He also became a committee member of the Manchester Board of Health, instigated principally by Thomas Percival

Thomas Percival (29 September 1740 – 30 August 1804) was an English physician, health reformer, ethicist and author who wrote an early code of medical ethics. He drew up a pamphlet with the code in 1794 and wrote an expanded version in 180 ...

to press for improvements in the health and working conditions of factory workers.

In July 1799 Owen and his partners bought the New Lanark mill from David Dale, and Owen became its manager in January 1800. Encouraged by his management success in Manchester, Owen hoped to conduct the New Lanark mill on higher principles than purely commercial ones. It had been established in 1785 by David Dale and Richard Arkwright

Sir Richard Arkwright (23 December 1732 – 3 August 1792) was an English inventor and a leading entrepreneur during the early Industrial Revolution. He is credited as the driving force behind the development of the spinning frame, known as ...

. Its water power provided by the falls of the River Clyde

The River Clyde (, ) is a river that flows into the Firth of Clyde, in the west of Scotland. It is the eighth-longest river in the United Kingdom, and the second longest in Scotland after the River Tay. It runs through the city of Glasgow. Th ...

turned its cotton-spinning operation into one of Britain's largest. About 2,000 individuals were involved, 500 of them children brought to the mill at the age of five or six from the poorhouses and charities of Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

and Glasgow. Dale, known for his benevolence, treated the children well, but the general condition of New Lanark residents was unsatisfactory, despite efforts by Dale and his son-in-law Owen to improve their workers' lives.John F. C. Harrison, "Robert Owen's Quest for the New Moral World in America," in

Many of the workers were from the lowest social levels: theft, drunkenness and other vices were common and education and sanitation neglected. Most families lived in one room. More respectable people rejected the long hours and demoralising drudgery of the mills.

Until a series of Truck Acts (1831–1887) required employers to pay their employees in common currency, many operated a truck system, paying workers wholly or in part with tokens that had no monetary value outside the mill owner's "truck shop", which charged high prices for shoddy goods. Unlike others, Owen's truck store offered goods at prices only slightly above their wholesale cost, passing on the savings from bulk purchases to his customers and placing alcohol sales under strict supervision. These principles became the basis for Britain's co-operative shops, some of which continue trading in altered forms to this day.

American communal living experiments

To test the viability of his ideas for self-sufficient working communities, Owen began experimenting with communal living in the

To test the viability of his ideas for self-sufficient working communities, Owen began experimenting with communal living in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

in 1825. Among the most famous efforts was the one set up at New Harmony, Indiana. Of the 130 identifiable communitarian experiments in the United States before the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, at least 16 were Owenite or Owenite-influenced. New Harmony was Owen's earliest and most ambitious of these.

Owen and his son William sailed to the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

in October 1824 to establish an experimental community in Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

. In January 1825 Owen used a portion of his funds to purchase an existing town of 180 buildings and several thousand acres of land along the Wabash River in Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

. George Rapp's Harmony Society, the religious group that owned the property and that had founded the communal village of Harmony (or Harmonie) on the site in 1814, decided in 1824 to relocate to Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

. Owen renamed it New Harmony and made the village his preliminary model for a Utopian community.

Owen sought support for his socialist vision among American thinkers, reformers, intellectuals and public statesmen. On 25 February and 7 March 1825, Owen gave addresses to the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

in Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

and to others in the US government, outlining his vision for the Utopian community at New Harmony, and his socialist beliefs. The audience for his ideas included three former U.S. presidents – John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before Presidency of John Adams, his presidency, he was a leader of ...

, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

, and James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

– the outgoing US President James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American Founding Father of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. He was the last Founding Father to serve as presiden ...

, and the President-elect, John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diploma ...

. His meetings were perhaps the first discussions of socialism in the Americas; they were certainly a big step towards discussion of it in the United States. Owenism

Owenism is the utopian socialist philosophy of 19th-century social reformer Robert Owen and his followers and successors, who are known as Owenites. Owenism aimed for radical reform of society and is considered a forerunner of the cooperative ...

, among the first socialist ideologies active in the United States, can be seen as an instigator of the later socialist movement.

Owen convinced William Maclure

William Maclure (27 October 176323 March 1840) was an Americanized Scottish geologist, cartographer and philanthropist. He is known as the 'father of American geology'. As a social experimenter on new types of community life, he collaborated w ...

, a wealthy Scottish scientist and philanthropist living in Philadelphia to join him at New Harmony and become his financial partner. Maclure's involvement went on to attract scientists, educators and artists such as Thomas Say

Thomas Say (June 27, 1787 – October 10, 1834) was an American entomologist, conchologist, and Herpetology, herpetologist. His studies of insects and shells, numerous contributions to scientific journals, and scientific expeditions to Florida, Ge ...

, Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, and Madame Marie Duclos Fretageot. These helped to turn the New Harmony community into a centre for educational reform, scientific research and artistic expression. See also:

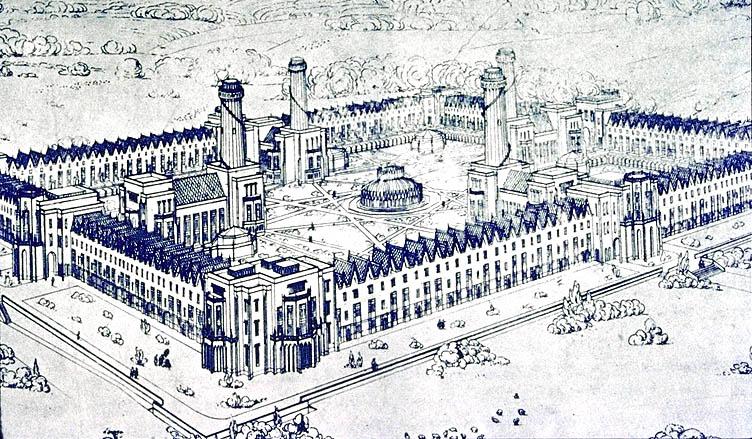

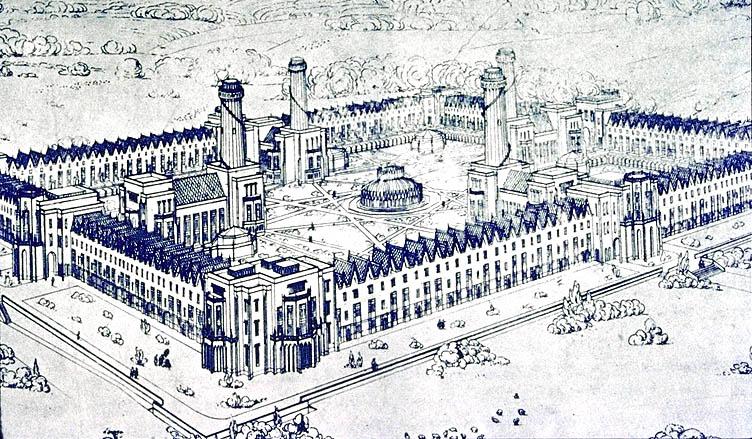

Although Owen sought to build a "Village of Unity and Mutual Cooperation" south of the town, his grand plan was never fully realised and he returned to Britain to continue his work. During his long absences from New Harmony, Owen left the experiment under the day-to-day management of his sons, Robert Dale Owen and William Owen, and his business partner, Maclure. However, New Harmony proved to be an economic failure, lasting about two years, although it had attracted over a thousand residents by the end of its first year. The socialistic society was dissolved in 1827, but many of its scientists, educators, artists and other inhabitants, including Owen's four sons, Robert Dale, William, David Dale, and Richard Dale Owen, and his daughter Jane Dale Owen Fauntleroy, remained at New Harmony after the experiment ended.

Other experiments in the United States included communal settlements at Blue Spring, near Bloomington, Indiana, at Yellow Springs, Ohio, and at Forestville Commonwealth at Earlton, New York, as well as other projects in New York, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

, and Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

. Nearly all of these had ended before New Harmony was dissolved in April 1827.

Owen's Utopian communities attracted a mix of people, many with the highest aims. They included vagrants, adventurers and other reform-minded enthusiasts. In the words of Owen's son David Dale Owen, they attracted "a heterogeneous collection of Radicals", "enthusiastic devotees to principle", and "honest latitudinarians, and lazy theorists", with "a sprinkling of unprincipled sharpers thrown in".

Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren (; June 26, 1798 – April 14, 1874) was an American Reformism (historical), social reformer, inventor, musician, businessman, and philosopher.

He is regarded as the first American Philosophical anarchism, philosophical anarchist ...

, a participant at New Harmony, asserted that it was doomed to failure for lack of individual sovereignty and personal property. In describing the community, Warren explained: "We had a world in miniature – we had enacted the French revolution over again with despairing hearts instead of corpses as a result ... It appeared that it was nature's inherent law of diversity that had conquered us ... our 'united interests' were directly at war with the individualities of persons and circumstances and the instinct of self-preservation". Warren's observations on the reasons for the community's failure led to the development of American individualist anarchism, of which he was its original theorist. Some historians have traced the demise of New Harmony to serial disagreements among its members.Estabrook, p. 68.

Social experiments also began in Scotland in 1825, when Abram Combe, an Owenite, attempted a utopian experiment at Orbiston, near Glasgow, but this failed after about two years. In the 1830s, additional experiments in socialistic co-operatives were made in Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

and Britain, the most important being at Ralahine, established in 1831 in County Clare

County Clare () is a Counties of Ireland, county in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster in the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern part of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, bordered on the west by the Atlantic Ocean. Clare County Council ...

, Ireland, and at Tytherley, begun in 1839 in Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Berkshire to the north, Surrey and West Sussex to the east, the Isle of Wight across the Solent to the south, ...

, England. The former proved a remarkable success for three-and-a-half years until the proprietor, having ruined himself by gambling, had to sell his interest. Tytherley, known as Harmony Hall or Queenwood College, was designed by the architect Joseph Hansom. This also failed. Another social experiment, Manea Colony in the Isle of Ely

The Isle of Ely () is a historic region around the city of Ely, Cambridgeshire, Ely in Cambridgeshire, England. Between 1889 and 1965, it formed an Administrative counties of England, administrative county.

Etymology

Its name has been said to ...

, Cambridgeshire, launched in the late 1830s by William Hodson, likewise an Owenite, but it failed in a couple of years and Hodson emigrated to the United States. The Manea Colony site has been excavated by the Cambridge Archaeology Unit (CAU) based at the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

.

Return to Great Britain

Although Owen made further brief visits to the United States, London became his permanent home and the centre of his work in 1828. After extended friction with William Allen and some other business partners, Owen relinquished all connections with New Lanark. He is often quoted in a comment by Allen at the time, "All the world is queer save thee and me, and even thou art a little queer". Having invested most of his fortune in the failed New Harmony communal experiment, Owen was no longer a wealthy capitalist. However, he remained the head of a vigorous propaganda effort to promote industrial equality, free education for children and adequate living conditions in factory towns, while delivering lectures in Europe and publishing a weekly newspaper to gain support for his ideas. In 1832 Owen opened the National Equitable Labour Exchange system, a time-based currency in which the exchange of goods was effected using labour notes; this system superseded the usual means of exchange and middlemen. The London exchange continued until 1833, with a Birmingham branch operating for just a few months until July 1833. Owen also became involved in trade unionism, briefly leading the Grand National Consolidated Trade Union (GNCTU) before its collapse in 1834. Socialism first became current in British terminology in discussions of the Association of all Classes of all Nations, which Owen formed in 1835 and served as its initial leader. Owen'ssecular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin , or or ), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. The origins of secularity can be traced to the Bible itself. The concept was fleshed out through Christian hi ...

views also gained enough influence among the working classes to cause the ''Westminster Review

The ''Westminster Review'' was a quarterly United Kingdom, British publication. Established in 1823 as the official organ of the Philosophical Radicals, it was published from 1824 to 1914. James Mill was one of the driving forces behind the libe ...

'' to comment in 1839 that his principles were the creed of many of them. However, by 1846, the only lasting result of Owen's agitation for social change, carried on through public meetings, pamphlets, periodicals, and occasional treatises, remained the Co-operative

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, coöperative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democr ...

movement, and for a time even that seemed to have collapsed.

As Owen grew older and more radical in his views, his influence began to decline.Estabrook, p. 68. Owen published his memoirs, ''The Life of Robert Owen'', in 1857, a year before his death.

Although he had spent most of his life in England and Scotland, Owen returned to his native town of Newtown at the end of his life. He died there on 17 November 1858 and was buried there on 21 November. He died penniless apart from an annual income drawn from a trust established by his sons in 1844.

Philosophy and influence

Owen tested his social and economic ideas at New Lanark, where he won his workers' confidence and continued to have success through improved efficiency at the mill. The community also earned an international reputation. Social reformers, statesmen and royalty, including the future TsarNicholas I of Russia

Nicholas I, group=pron (Russian language, Russian: Николай I Павлович; – ) was Emperor of Russia, List of rulers of Partitioned Poland#Kings of the Kingdom of Poland, King of Congress Poland, and Grand Duke of Finland from 18 ...

, visited New Lanark to study its methods. The opinions of many such visitors were favourable.Harrison, "Robert Owen's Quest for the New Moral World in America," in ''Robert Owen's American Legacy'', p. 37.

Some of Owen's schemes displeased his partners, forcing him to arrange for other investors to buy his share of the business in 1813, for the equivalent of US$800,000. The new investors, who included Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 4 February Dual dating, 1747/8 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. 5 February 1748 Old Style and New Style dates, N.S.– 6 June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of mo ...

and the well-known Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

William Allen, were content to accept a £5,000 return on their capital. The ownership change also provided Owen with a chance to broaden his philanthropy

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives for the Public good (economics), public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private goo ...

, advocating improvements in workers' rights

Labor rights or workers' rights are both legal rights and human rights relating to labor relations between workers and employers. These rights are codified in national and international labor and employment law. In general, ...

and child labour laws, and free education

Free education is education funded through government spending or charitable organizations rather than tuition funding. Primary school and other comprehensive or compulsory education is free in most countries (often not including primary textboo ...

for children.

Owen felt that human character is formed by conditions over which individuals have no control. Thus individuals could not be praised or blamed for their behaviour or situation in life. This principle led Owen to conclude that the correct formation of people's characters called for placing them under proper environmental influences – physical, moral and social – from their earliest years. These notions of inherent irresponsibility in humans and the effect of early influences on an individual's character formed the basis of Owen's system of education and social reform.

Relying on his observations, experiences and thoughts, Owen saw his view of human nature as original and "the most basic and necessary constituent in an evolving science of society".Curti, "Robert Owen in American Thought", in ''Robert Owen's American Legacy'', p. 61. His philosophy was influenced by Sir Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

's views on natural law, and his views resembled those of Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

, Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a prominent figure during th ...

, Claude Adrien Helvétius, William Godwin

William Godwin (3 March 1756 – 7 April 1836) was an English journalist, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism and the first modern proponent of anarchism. Godwin is most famous fo ...

, John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

, James Mill

James Mill (born James Milne; 6 April 1773 – 23 June 1836) was a Scottish historian, economist, political theorist and philosopher. He is counted among the founders of the Ricardian school of economics. He also wrote '' The History of Britis ...

, and Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 4 February Dual dating, 1747/8 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. 5 February 1748 Old Style and New Style dates, N.S.– 6 June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of mo ...

, among others. Owen did not have the direct influence of Enlightenment philosophers.

Owen hoped for a better and more harmonious environment that promoted mutual respect, love and moral values. He believed everyone would have a good education and better living condition to live righteously. He valued social and educational reforms for the middle class and rejected the capitalist power which elevated the powerful figures at the expense of others. Regardless of his adversaries' attacks, he remained persuasive of his goals. Owen funded kids' schools and advocated for free education, equal rights and freedom. He participated in legislation to improve labourers' wages and working conditions.

Owen believed compassion, kindness and solidarity

Solidarity or solidarism is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. True solidarity means moving beyond individual identities and single issue politics ...

corrected bad habits, encouraged self-discipline

Discipline is the self-control that is gained by requiring that rules or orders be obeyed, and the ability to keep working at something that is difficult. Disciplinarians believe that such self-control is of the utmost importance and enforce a ...

and enhanced a person's attitude. Force oppressed people and affected their mental health

Mental health is often mistakenly equated with the absence of mental illness. However, mental health refers to a person's overall emotional, psychological, and social well-being. It influences how individuals think, feel, and behave, and how t ...

. In his view, unless people were educated in a proper environment, obtained equal opportunities for jobs and maintained social norms, differences between labour classes, conflicts, and inequalities would persist just as in the British colonies. Without making any changes in the national institutions, he believed that even reorganizing the working classes would bring great benefits. So he opposed the views of radicals seeking to change in the public mentality by expanding voting rights.

Education

Owen's work at New Lanark continued to have significance in Britain and continental Europe. He was a "pioneer in factory reform, the father of distributive co-operation, and the founder of nursery schools". His schemes for educating his workers included opening an Institute for the Formation of Character at New Lanark in 1818. This and other programmes at New Lanark provided free education from infancy to adulthood. In addition, he zealously supported factory legislation that culminated in the Cotton Mills and Factories Act 1819. Owen also had interviews and communications with leading members of the British government, including its premier, Robert Banks Jenkinson,Lord Liverpool

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool (7 June 1770 – 4 December 1828) was a British Tory statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1812 to 1827. Before becoming Prime Minister he had been Foreign Secretary, ...

. He also met many of the rulers and leading statesmen of Europe.

Owen's biggest success was in support of youth education and early child care. As a pioneer in Britain, notably Scotland, Owen provided an alternative to the "normal authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in democracy, separation of powers, civil liberties, and ...

approach to child education". Supporters of the methods argued that the manners of children brought up under his system were more graceful, genial and unconstrained; health, plenty and contentment prevailed; drunkenness was almost unknown and illegitimacy extremely rare. Owen's relations with his workers remained excellent and operations at the mill proceeded in a smooth, regular and commercially successful way.

Perhaps one of Robert Owen's most memorable ideas was his silent monitor method. Owen was opposed to common corporal punishment; therefore, to have some form of discipline he developed the "silent monitor". In his mills, he would hang a four-sided block each displaying a different colour representing the behaviour of the employee.

Labor

Owen adopted new principles to raise the standard of goods his workers produced. A cube with faces painted in different colours was installed above each machinist's workplace. The colour of the face showed to all who saw it the quality and quantity of goods the worker completed. The intention was to encourage workers to do their best. Although it was no great incentive in itself, conditions at New Lanark for workers and their families were idyllic for the time. Owen raised the demand for an eight-hour day in 1810 and set about instituting the policy at New Lanark. By 1817 he had formulated the goal of an eight-hour working day with the slogan "eight hours labour, eight hours recreation, eight hours rest".Socialism

In 1813 Owen authored and published ''A New View of Society, or Essays on the Principle of the Formation of the Human Character'', the first of four essays he wrote to explain the principles behind his philosophy of socialistic reform. In this he writes: Owen had originally been a follower of the classical liberal,utilitarian

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for the affected individuals. In other words, utilitarian ideas encourage actions that lead to the ...

Jeremy Bentham, who believed that free market

In economics, a free market is an economic market (economics), system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of ...

s and ''laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

'', in particular the right of workers to move and choose their employers, would release workers from the excessive power of capitalists. However, Owen developed his own, pro-socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

outlook. In addition, Owen as a deist

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin term '' deus'', meaning "god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge and asserts that empirical reason and observation ...

, criticised organised religion, including the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

, and developed a belief system of his own.

Owen embraced socialism in 1817, a turning point in his life, in which he pursued a "New View of Society". He outlined his position in a report to the committee of the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

on the country's Poor Laws

The English Poor Laws were a system of poor relief in England and Wales that developed out of the codification of late-medieval and Tudor-era laws in 1587–1598. The system continued until the modern welfare state emerged in the late 1940s.

E ...

. As misery and trade stagnation after the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

drew national attention, the government called on Owen for advice on how to alleviate the industrial concerns. Although he ascribed the immediate misery to the wars, he saw it as the underlying cause of competition of human labour with machinery and recommended setting up self-sufficient communities.

Owen appealed to the self-interest of capitalists, pointing out that just as machines need proper care and treatment to guarantee they work smoothly and efficiently, so do humans.

Owen proposed that communities of some 1,200 people should settle on land from , all living in one building with a public kitchen and dining halls. (The proposed size may have been influenced by the size of the village of New Lanark.) Owen also proposed that each family have its private apartment and the responsibility for the care of its children up to the age of three. Thereafter children would be raised by the community, but their parents would have access to them at mealtimes and on other occasions. Owen further suggested that such communities be established by individuals, parishes, counties

A county () is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesL. Brookes (ed.) '' Chambers Dictionary''. Edinburgh: Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, 2005. in some nations. The term is derived from the Old French denoti ...

, or other governmental units. In each case, there would be effective supervision by qualified persons. Work and enjoyment of its results should be experienced communally. Owen believed his idea would be the best way to reorganise society in general, and called his vision the "New Moral World".

Owen's utopian model changed little in his lifetime. His developed model envisaged an association of 500–3,000 people as the optimum for a working community. While mainly agricultural, it would possess the best machinery, offer varied employment, and as far as possible be self-contained. Owen went on to explain that as such communities proliferated, "unions of them federatively united shall be formed in the circle of tens, hundreds and thousands", linked by a common interest.

Owen grew to be known as a utopian socialist and his works are considered to reflect this attitude. Although he could be considered a member of the bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted wi ...

his relationship with this class was often complicated. He fought to pass legislation that benefitted workers. He was an advocate for the Cotton Mills and Factories Act 1819. He supported socialist ideas so his views did not have an immediate impact in Britain or the United States.

Spiritualism

In 1817, Owen publicly claimed that all religions were false. In 1854, aged 83, Owen converted to spiritualism after a series of sittings with Maria B. Hayden, an American medium credited with introducing spiritualism to England. He made a public profession of his new faith in his publication ''The Rational Quarterly Review'' and in a pamphlet titled ''The Future of the Human Race; or great glorious and future revolution to be effected through the agency of departed spirits of good and superior men and women''. Owen claimed to have had medium contact with the spirits ofBenjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

and others. He explained that the purpose of these was to change "the present, false, disunited and miserable state of human existence, for a true, united and happy state... to prepare the world for universal peace, and to infuse into all the spirit of charity, forbearance and love."

Spiritualists claimed after Owen's death that his spirit had dictated to the medium Emma Hardinge Britten in 1871 the " Seven Principles of Spiritualism", used by their National Union as "the basis of its religious philosophy".

Legacy

Owen was a reformer, philanthropist, community builder, and spiritualist who spent his life seeking to improve the lives of others. An advocate of the working class, he improved working conditions for factory workers, which he demonstrated at New Lanark, Scotland, became a leader in trade unionism, promoted social equality through his experimental Utopian communities, and supported the passage of child labour laws and free education for children. In these reforms he was ahead of his time. He envisioned a communal society that others could consider and apply as they wished. In ''Revolution in the Mind and Practice of the Human Race'' (1849), he went on to say that character is formed by a combination of Nature or God and the circumstances of the individual's experience. Citing beneficial results at New Lanark, Scotland, during 30 years of work there, Owen concluded that a person's "character is not made ''by'', but ''for'' the individual," and that nature and society are responsible for each person's character and conduct. Owen's agitation for social change, along with the work of the Owenites and his children, helped to bring lasting social reforms in women's and workers' rights, establish free public libraries and museums, child care and public, co-educational schools, and pre-Marxian communism, and develop the Co-operative and trade union movements. New Harmony, Indiana, and New Lanark, Scotland, two towns with which he is closely associated, remain as reminders of his efforts. Owen's legacy of public service continued with his four sons, Robert Dale, William, David Dale, and Richard Dale, and his daughter, Jane, who followed him to America to live in New Harmony, Indiana: * Robert Dale Owen (1801–1877), an able exponent of his father's doctrines, managed the New Harmony community after his father returned to Britain in 1825. He wrote articles and co-edited with Frances Wright the ''New-Harmony Gazette'' in the late 1820s in Indiana and the ''Free Enquirer'' in the 1830s inNew York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

. Owen returned to New Harmony in 1833 and became active in Indiana politics. He was elected to the Indiana House of Representatives

The Indiana House of Representatives is the lower house of the Indiana General Assembly, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Indiana. The House is composed of 100 members representing an equal number of constituent districts. House mem ...

(1836–1839 and 1851–1853) and U.S. House of Representatives (1843–1847) and was appointed chargé d'affaires in Naples in 1853–1858. While serving as a member of Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

, he drafted and helped to secure passage of a bill founding the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

in 1846. He was elected a delegate to the Indiana Constitutional Convention in 1850,Estabrook, pp. 72–74. and argued in support of widows and married women's property and divorce rights. He also favoured legislation for Indiana's tax-supported public school system. Like his father, he believed in spiritualism, authoring two books on the subject: ''Footfalls on the Boundary of Another World'' (1859) and ''The Debatable Land Between this World and the Next'' (1872).

*William Owen (1802–1842) moved to the United States with his father in 1824. His business skill, notably his knowledge of cotton goods manufacturing, allowed him to remain at New Harmony after his father returned to Scotland, and serve as an adviser to the community. He organised New Harmony's Thespian Society in 1827 but died of unknown causes at the age of 40.

*Jane Dale Owen Fauntleroy (1805–1861) arrived in the United States in 1833 and settled in New Harmony. She was a musician and educator who set up a school in her home. In 1835 she married Robert Henry Fauntleroy, a civil engineer from Virginia living in New Harmony.

* David Dale Owen (1807–1860) moved to the United States in 1827 and resided at New Harmony for several years. He trained as a geologist and natural scientist and earned a medical degree. He was appointed a United States geologist in 1839. His work included geological surveys in the Midwest

The Midwestern United States (also referred to as the Midwest, the Heartland or the American Midwest) is one of the four census regions defined by the United States Census Bureau. It occupies the northern central part of the United States. It ...

, more specifically the states of Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

, Iowa

Iowa ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the upper Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west; Wisconsin to the northeast, Ill ...

, Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

, and Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

, as well as Minnesota Territory. His brother Richard succeeded him as state geologist of Indiana.Leopold, ''Robert Dale Owen, A Biography'', pp. 50–51.

* Richard Dale Owen (1810–1890) emigrated to the United States in 1827 and joined his siblings at New Harmony. He fought in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

in 1847, taught natural science at Western Military Institute in Tennessee from 1849 to 1859, and earned a medical degree in 1858. During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

he was a colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

in the Union army and served as a commandant of Camp Morton, a prisoner-of-war camp for Confederate soldiers at Indianapolis

Indianapolis ( ), colloquially known as Indy, is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Indiana, most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the county seat of Marion County, Indiana, Marion ...

, Indiana. After the war, Owen served as Indiana's second state geologist. In addition, he was a professor at Indiana University

Indiana University (IU) is a state university system, system of Public university, public universities in the U.S. state of Indiana. The system has two core campuses, five regional campuses, and two regional centers under the administration o ...

and chaired its natural science department from 1864 to 1879. He helped plan Purdue University

Purdue University is a Public university#United States, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in West Lafayette, Indiana, United States, and the flagship campus of the Purdue University system. The university was founded ...

and was appointed its first president in 1872–1874, but resigned before its classes began and resumed teaching at Indiana University. He spent his retirement years on research and writing.

Honours and tributes

*A simple slate tomb for Owen was installed in St Mary's Churchyard in Newtown. In 1902 the co-operative movement erected

*A simple slate tomb for Owen was installed in St Mary's Churchyard in Newtown. In 1902 the co-operative movement erected Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau ( ; ; ), Jugendstil and Sezessionstil in German, is an international style of art, architecture, and applied art, especially the decorative arts. It was often inspired by natural forms such as the sinuous curves of plants and ...

railings around the tomb as a monument to him.

*In 1956 a bronze statue of Owen by Gilbert Bayes was installed in a small garden dedicated to Owen in Newtown.

*The Welsh people donated a bust of Owen by Welsh sculptor Sir William Goscombe John to the International Labour Office library in Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

, Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

.

*In 1994 the Co-operative Bank installed a copy of the Newtown statue in front of its headquarters on Balloon Street, Manchester.

Criticism of Owen

Owen's project was considered unachievable because he did not establish a guideline that stipulated the administration of properties and the conditions of memberships. As a result, some critics found his plans unsatisfactory and ineffective because the overpopulation and shortage of supply created antagonism within the community. Owen's opponents view him as a dictator, and a blasphemer of Christianity because he rejected sacred beliefs and defied anyone who differed from his views. Owen perceived religion as a source of fear and ignorance. Therefore, people were unable to think rationally if they stayed attached to "fallacious testimonies" of religion. Other notable critics of Owen includeKarl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;"Engels"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.''Capital'', that it is the working class that is responsible for creating the unparalleled wealth in capitalist societies. Similarly, Owen also recognized that under the existing economic system, the working class did not automatically receive the benefits of that newly created wealth. Marx and Engels, differentiated, however, their scientific conception of socialism from Owen's societies. They argued that Owen's plan, to create a model socialist utopia to coexist with contemporary society and prove its superiority over time, was insufficient to create a new society. In their view, Owen's "socialism" was utopian, since to Owen and the other utopian socialists "socialism is the expression of absolute truth, reason and justice, and has only to be discovered to conquer all the world by its power." Marx and Engels believed that the overthrow of the capitalist system could only occur once the working class was organized into a revolutionary socialist political party of the working class that was completely independent of all capitalist class influence, whereas the utopians sought the assistance and the co-operation of the capitalists to achieve the transition to socialism.

A New View of Society and Other Writings

', introduction by G. D. H. Cole. London and New York: J. M. Dent & Sons, E. P. Dutton and Co., 1927 *''A New View of Society and Other Writings'', G. Claeys, ed. London and New York: Penguin Books, 1991 *''The Selected Works of Robert Owen'', G. Claeys, ed., 4 vols. London: Pickering and Chatto, 1993 Archival collections: *Robert Owen Collection, National Co-operative Archive, United Kingdom. *New Harmony, Indiana, Collection, 1814–1884, 1920, 1964, Indiana Historical Society, Indianapolis, Indiana, United States *New Harmony Series III Collection, Workingmen's Institute, New Harmony, Indiana, United States *Owen family collection, 1826–1967, bulk 1830–1890, Indiana University Archives, Bloomington, Indiana, United StatesThe collection includes the correspondence, speeches, and publications of Robert Owens and his descendants. See

online access

* * * * * * (online version) * * * * * * *

Robert Owen, the Founder of Socialism in England

' (London, 1869) *G. D. H. Cole,

Life of Robert Owen

'. London, Ernest Benn Ltd., 1925; second edition Macmillan, 1930 * Lloyd Jones.

The Life, Times, and Labours of Robert Owen

'. London, 1889 *A. L. Morton,

The Life and Ideas of Robert Owen

'. New York, International Publishers, 1969 *W. H. Oliver, "Robert Owen and the English Working-Class Movements", ''History Today'' (November 1958) 8–11, pp. 787–796 *F. A. Packard,

Life of Robert Owen

'. Philadelphia: Ashmead & Evans, 1866 * Frank Podmore,

Robert Owen: A Biography

'. London: Hutchinson and Company, 1906 *David Santilli, ''Life of the Mill Man''. London, B. T. Batsford Ltd, 1987 * William Lucas Sargant,

Robert Owen and his social philosophy

'. London, 1860 *Richard Tames, ''Radicals, Railways & Reform''. London, B. T. Batsford Ltd, 1986

Robert Owen: Aspects of his Life and Work

'. Humanities Press, 1971 * *Gregory Claeys, ''Citizens and Saints. Politics and Anti-Politics in Early British Socialism''. Cambridge University Press, 1989 * Gregory Claeys, ''Machinery, Money and the Millennium: From Moral Economy to Socialism 1815–1860''. Princeton University Press, 1987 *R. E. Davies,

The Life of Robert Owen, Philanthropist and Social Reformer, An Appreciation

'. Robert Sutton, 1907 *R. E. Davis and F. J. O'Hagan, ''Robert Owen''. London: Continuum Press, 2010 *I. Donnachie, ''Robert Owen. Owen of New Lanark and New Harmony''. 2000 * John F. C. Harrison, ''Robert Owen and the Owenites in Britain and America: Quest for the New Moral World''. New York, 1969 * Alexander Herzen, ''My Past and Thoughts'' (University of California Press, 1982). (One chapter is devoted to Owen.) * G. J. Holyoake,

The History of Co-operation in England: Its Literature and Its Advocates

' V. 1. London, 1906 *G. J. Holyoake, '' The History of Co-operation in England: Its Literature and Its Advocates'' V. 2. London, 1906 *The National Library of Wales,

A Bibliography of Robert Owen, The Socialist

'. 1914 * * Chris Rogers, "Robert Owen, utopian socialism and social transformation." ''Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences'' 54.4 (2018): 256-271

online

*O. Siméon,

Robert Owen's Experiment at New Lanark. From Paternalism to Socialism

'. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017 * Ophélie, Siméon. "Robert Owen: The Father of British Socialism?" ''Books and Ideas'' (2012)

online

at the Marxists Internet Archive

Brief biography at the New Lanark World Heritage Site

The Robert Owen Museum

Newtown, Wales

Video of Owen's wool mill

"Robert Owen and the Co-operative movement"

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Owen, Robert 1771 births 1858 deaths British cooperative organizers European democratic socialists Founders of utopian communities People from Newtown, Powys Owenites Utopian socialists Welsh agnostics Welsh humanists 19th-century Welsh businesspeople 18th-century Welsh businesspeople Welsh business theorists Welsh philanthropists Welsh socialists British social reformers Socialist economists British textile industry businesspeople

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.''Capital'', that it is the working class that is responsible for creating the unparalleled wealth in capitalist societies. Similarly, Owen also recognized that under the existing economic system, the working class did not automatically receive the benefits of that newly created wealth. Marx and Engels, differentiated, however, their scientific conception of socialism from Owen's societies. They argued that Owen's plan, to create a model socialist utopia to coexist with contemporary society and prove its superiority over time, was insufficient to create a new society. In their view, Owen's "socialism" was utopian, since to Owen and the other utopian socialists "socialism is the expression of absolute truth, reason and justice, and has only to be discovered to conquer all the world by its power." Marx and Engels believed that the overthrow of the capitalist system could only occur once the working class was organized into a revolutionary socialist political party of the working class that was completely independent of all capitalist class influence, whereas the utopians sought the assistance and the co-operation of the capitalists to achieve the transition to socialism.

Selected published works

*'' A New View of Society: Or, Essays on the Formation of Human Character, and the Application of the Principle to Practice'' (London, 1813). Retitled, ''A New View of Society: Or, Essays on the Formation of Human Character Preparatory to the Development of a Plan for Gradually Ameliorating the Condition of Mankind'', for the second edition, 1816 *'' Observations on the Effect of the Manufacturing System''. London, 1815 *'' Report to the Committee of the Association for the Relief of the Manufacturing and Labouring Poor'' (1817) *'' Two Memorials on Behalf of the Working Classes'' (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1818) *'' An Address to the Master Manufacturers of Great Britain: On the Present Existing Evils in the Manufacturing System'' (Bolton, 1819) *'' Report to the County of Lanark of a Plan for relieving Public Distress'' (Glasgow: Glasgow University Press, 1821) *'' An Explanation of the Cause of Distress which pervades the civilised parts of the world'' (London and Paris, 1823) *'' An Address to All Classes in the State''. London, 1832 *'' The Revolution in the Mind and Practice of the Human Race''. London, 1849 Collected works: *A New View of Society and Other Writings

', introduction by G. D. H. Cole. London and New York: J. M. Dent & Sons, E. P. Dutton and Co., 1927 *''A New View of Society and Other Writings'', G. Claeys, ed. London and New York: Penguin Books, 1991 *''The Selected Works of Robert Owen'', G. Claeys, ed., 4 vols. London: Pickering and Chatto, 1993 Archival collections: *Robert Owen Collection, National Co-operative Archive, United Kingdom. *New Harmony, Indiana, Collection, 1814–1884, 1920, 1964, Indiana Historical Society, Indianapolis, Indiana, United States *New Harmony Series III Collection, Workingmen's Institute, New Harmony, Indiana, United States *Owen family collection, 1826–1967, bulk 1830–1890, Indiana University Archives, Bloomington, Indiana, United StatesThe collection includes the correspondence, speeches, and publications of Robert Owens and his descendants. See

See also

*Cincinnati Time Store

The Cincinnati Time Store (1827–1830) was the first in a series of retail stores created by American individualist anarchist Josiah Warren to test his economic labor theory of value. The experimental store operated from May 18, 1827, until Ma ...

*José María Arizmendiarrieta

José María Arizmendiarrieta Madariaga (Markina-Xemein, Biscay, Spain, April 22, 1915 – Mondragón, Gipuzkoa, Spain, November 29, 1976) was a Spaniard, Spanish Catholic Church, Catholic priest and promoter of the cooperative companies of the ...

*Labour voucher

Labour vouchers (also known as labour cheques, labour notes, labour certificates and personal credit) are a device proposed to govern demand for goods in some models of socialism and to replace some of the tasks performed by currency under capi ...

*List of Owenite communities in the United States

This is a list of Owenite communities in the United States which emerged during a short-lived popular boom during the second half of the 1820s. Between 1825 and 1830 more than a dozen such colonies were established in the US, inspired by the ide ...

* Owenstown

*Owenism

Owenism is the utopian socialist philosophy of 19th-century social reformer Robert Owen and his followers and successors, who are known as Owenites. Owenism aimed for radical reform of society and is considered a forerunner of the cooperative ...

* William King

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Parris, Leah (2021). ''Robert Owen's Welsh Influence on the Scottish Industrial Community of New Lanark (1800 – 1825''). Student dissertation for The Open University module A329 The making of Welsh historonline access

* * * * * * (online version) * * * * * * *

Further reading

*Biographies of Owen

*A. J. Booth,Robert Owen, the Founder of Socialism in England

' (London, 1869) *G. D. H. Cole,

Life of Robert Owen

'. London, Ernest Benn Ltd., 1925; second edition Macmillan, 1930 * Lloyd Jones.

The Life, Times, and Labours of Robert Owen

'. London, 1889 *A. L. Morton,

The Life and Ideas of Robert Owen

'. New York, International Publishers, 1969 *W. H. Oliver, "Robert Owen and the English Working-Class Movements", ''History Today'' (November 1958) 8–11, pp. 787–796 *F. A. Packard,

Life of Robert Owen

'. Philadelphia: Ashmead & Evans, 1866 * Frank Podmore,

Robert Owen: A Biography

'. London: Hutchinson and Company, 1906 *David Santilli, ''Life of the Mill Man''. London, B. T. Batsford Ltd, 1987 * William Lucas Sargant,

Robert Owen and his social philosophy

'. London, 1860 *Richard Tames, ''Radicals, Railways & Reform''. London, B. T. Batsford Ltd, 1986

Other works about Owen

* Arthur Bestor, ''Backwoods Utopias''. The University of Pennsylvania Press, 1950, 2nd edition, 1970 *John Butt (ed).Robert Owen: Aspects of his Life and Work

'. Humanities Press, 1971 * *Gregory Claeys, ''Citizens and Saints. Politics and Anti-Politics in Early British Socialism''. Cambridge University Press, 1989 * Gregory Claeys, ''Machinery, Money and the Millennium: From Moral Economy to Socialism 1815–1860''. Princeton University Press, 1987 *R. E. Davies,

The Life of Robert Owen, Philanthropist and Social Reformer, An Appreciation

'. Robert Sutton, 1907 *R. E. Davis and F. J. O'Hagan, ''Robert Owen''. London: Continuum Press, 2010 *I. Donnachie, ''Robert Owen. Owen of New Lanark and New Harmony''. 2000 * John F. C. Harrison, ''Robert Owen and the Owenites in Britain and America: Quest for the New Moral World''. New York, 1969 * Alexander Herzen, ''My Past and Thoughts'' (University of California Press, 1982). (One chapter is devoted to Owen.) * G. J. Holyoake,

The History of Co-operation in England: Its Literature and Its Advocates

' V. 1. London, 1906 *G. J. Holyoake, '' The History of Co-operation in England: Its Literature and Its Advocates'' V. 2. London, 1906 *The National Library of Wales,

A Bibliography of Robert Owen, The Socialist

'. 1914 * * Chris Rogers, "Robert Owen, utopian socialism and social transformation." ''Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences'' 54.4 (2018): 256-271

online

*O. Siméon,

Robert Owen's Experiment at New Lanark. From Paternalism to Socialism

'. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017 * Ophélie, Siméon. "Robert Owen: The Father of British Socialism?" ''Books and Ideas'' (2012)

online

External links

at the Marxists Internet Archive

Brief biography at the New Lanark World Heritage Site

The Robert Owen Museum

Newtown, Wales

Video of Owen's wool mill

University of Evansville

The University of Evansville (UE) is a private university in Evansville, Indiana. It was founded in 1854 as Carnegie Hall of Moores Hill College, Moores Hill College. The university operates a satellite center, Harlaxton Manor, Harlaxton College ...

, Indiana"Robert Owen and the Co-operative movement"

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Owen, Robert 1771 births 1858 deaths British cooperative organizers European democratic socialists Founders of utopian communities People from Newtown, Powys Owenites Utopian socialists Welsh agnostics Welsh humanists 19th-century Welsh businesspeople 18th-century Welsh businesspeople Welsh business theorists Welsh philanthropists Welsh socialists British social reformers Socialist economists British textile industry businesspeople