Robert Christy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Robert Frederick Christy (May 14, 1916 – October 3, 2012) was a Canadian-American

Christy could have graduated in 1940, but could not then be a teaching assistant, and this would have left him jobless and without income. In 1941, Oppenheimer found him a post at the physics department at

Christy could have graduated in 1940, but could not then be a teaching assistant, and this would have left him jobless and without income. In 1941, Oppenheimer found him a post at the physics department at

After the war ended, Christy accepted an

After the war ended, Christy accepted an  During a sabbatical year at

During a sabbatical year at

1983 Audio Interview with Robert Christy by Martin Sherwin

Voices of the Manhattan Project *

Interview with Robert F. Christy

Caltech Oral Histories, Caltech Archives, California Institute of Technology. {{DEFAULTSORT:Christy, Robert 1916 births 2012 deaths American astrophysicists 20th-century American astronomers Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Presidents of the California Institute of Technology Manhattan Project people University of Chicago faculty University of British Columbia Faculty of Science alumni UC Berkeley College of Letters and Science alumni Fellows of the American Physical Society Canadian emigrants to the United States

theoretical physicist

Theoretical physics is a branch of physics that employs mathematical models and abstractions of physical objects and systems to rationalize, explain, and predict natural phenomena. This is in contrast to experimental physics, which uses experi ...

and later astrophysicist who was one of the last surviving people to have worked on the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. He briefly served as acting president of California Institute of Technology

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech) is a private research university in Pasadena, California, United States. The university is responsible for many modern scientific advancements and is among a small group of institutes ...

(Caltech).

A graduate of the University of British Columbia

The University of British Columbia (UBC) is a Public university, public research university with campuses near University of British Columbia Vancouver, Vancouver and University of British Columbia Okanagan, Kelowna, in British Columbia, Canada ...

(UBC) in the 1930s where he studied physics, he followed George Volkoff

George Michael Volkoff, (February 23, 1914 – April 24, 2000) was a Russian-Canadian physicist and academic who helped, with J. Robert Oppenheimer, predict the existence of neutron stars before they were discovered.

Early life

He was born ...

, who was a year ahead of him, to the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

, where he was accepted as a graduate student by Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (born Julius Robert Oppenheimer ; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist who served as the director of the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II. He is often ...

, the leading theoretical physicist in the United States at that time. Christy received his doctorate in 1941 and joined the physics department of Illinois Institute of Technology

The Illinois Institute of Technology, commonly referred to as Illinois Tech and IIT, is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Tracing its history to 1890, the present name was adopted upon the m ...

.

In 1942 he joined the Manhattan Project at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, or UChi) is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Its main campus is in the Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, Chic ...

, where he was recruited by Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian and naturalized American physicist, renowned for being the creator of the world's first artificial nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1, and a member of the Manhattan Project ...

to join the effort to build the first nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a Nuclear fission, fission nuclear chain reaction. They are used for Nuclear power, commercial electricity, nuclear marine propulsion, marine propulsion, Weapons-grade plutonium, weapons ...

, having been recommended as a theory resource by Oppenheimer. When Oppenheimer formed the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret scientific laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and overseen by the University of California during World War II. It was operated in partnership with the United State ...

in 1943, Christy was one of the early recruits to join the Theory Group. Christy is generally credited with the insight that a solid sub-critical mass of plutonium could be explosively compressed into supercriticality, a great simplification of earlier concepts of implosion requiring hollow shells. For this insight the solid-core plutonium model is often referred to as the " Christy pit".

After the war, Christy briefly joined the University of Chicago Physics department before being recruited to join the Caltech faculty in 1946 when Oppenheimer decided it was not practical for him to resume his academic activities. He stayed at Caltech for his academic career, serving as Department Chair, Provost and Acting President. In 1960 Christy turned his attention to astrophysics, creating some of the first practical computation models of stellar oscillations. For this work Christy was awarded the Eddington Medal

The Eddington Medal is awarded by the Royal Astronomical Society for investigations of outstanding merit in theoretical astrophysics. It is named after Sir Arthur Eddington. First awarded in 1953, the frequency of the prize has varied over the ye ...

of the Royal Astronomical Society

The Royal Astronomical Society (RAS) is a learned society and charitable organisation, charity that encourages and promotes the study of astronomy, planetary science, solar-system science, geophysics and closely related branches of science. Its ...

in 1967. In the 1980s and 1990s Christy participated in the National Research Council's Committee on Dosimetry, an extended effort to better understand the actual radiation exposure due to the bombs dropped on Japan, and on the basis of that learning, better understand the medical risks of radiation exposure.

Early life

Robert Frederick Cohen was born on May 14, 1916, inVancouver, British Columbia

Vancouver is a major city in Western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the List of cities in British Columbia, most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the cit ...

, the son of Moise Jacques Cohen, an electrical engineer, and his wife Hattie Alberta née Mackay, a school teacher. He was named Robert after his maternal great uncle Robert Wood, and Frederick after Frederick Alexander Christy, the second husband of his maternal grandmother. He had an older brother, John, who was born in 1913. Moise changed the family surname to Christy by deed poll

A deed poll (plural: deeds poll) is a legal document binding on a single person or several persons acting jointly to express an intention or create an obligation. It is a deed, and not a contract, because it binds only one party.

Etymology

Th ...

on August 31, 1918. On November 4, Moise was accidentally electrocuted at work. Hattie died after goitre

A goitre (British English), or goiter (American English), is a swelling in the neck resulting from an enlarged thyroid gland. A goitre can be associated with a thyroid that is not functioning properly.

Worldwide, over 90% of goitre cases are ...

surgery in 1926. Christy and his brother were then cared for by Robert Wood, their grandmother Alberta Mackay, and their great aunt Maud Mackay.

Christy was educated at Magee High School, and graduated in 1932 with the highest examination score in the province of British Columbia

British Columbia is the westernmost Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada. Situated in the Pacific Northwest between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains, the province has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that ...

. He was awarded the Governor General's Academic Medal, and, importantly in view of his family's limited ability to pay, free tuition to attend the University of British Columbia

The University of British Columbia (UBC) is a Public university, public research university with campuses near University of British Columbia Vancouver, Vancouver and University of British Columbia Okanagan, Kelowna, in British Columbia, Canada ...

(UBC). At the award dinner he met the second-place winner, Dagmar Elizabeth von Lieven, whom he dated while at UBC. He received his Bachelor of Arts

A Bachelor of Arts (abbreviated B.A., BA, A.B. or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is the holder of a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the liberal arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts deg ...

(BA) degree in mathematics and physics with first class honors in 1935, and his Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA or AM) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Those admitted to the degree have ...

(MA) degree in 1937, writing a thesis on "Electron attachment and negative ion formation in oxygen".

George Volkoff

George Michael Volkoff, (February 23, 1914 – April 24, 2000) was a Russian-Canadian physicist and academic who helped, with J. Robert Oppenheimer, predict the existence of neutron stars before they were discovered.

Early life

He was born ...

, a friend of Christy who was a year ahead of him at UBC, was accepted as a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

, by Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (born Julius Robert Oppenheimer ; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist who served as the director of the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II. He is often ...

, who led the most active school of theoretical physics in the United States at that time. This inspired Christy to apply to the University of California as well. He was accepted, and was awarded a fellowship for his first year. At Berkeley he shared an apartment with Volkoff, Robert Cornog, Ken McKenzie and McKenzie's wife Lynn McKenzie. For his thesis, Oppenheimer had him look at mesotrons, subatomic particles called muons today, that had recently been found in cosmic ray

Cosmic rays or astroparticles are high-energy particles or clusters of particles (primarily represented by protons or atomic nuclei) that move through space at nearly the speed of light. They originate from the Sun, from outside of the ...

s. They were so-called because they were more massive than electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

s but less massive than proton

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , Hydron (chemistry), H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' (elementary charge). Its mass is slightly less than the mass of a neutron and approximately times the mass of an e ...

s. With the help of Shuichi Kusaka he performed detailed calculations of the particle's spin

Spin or spinning most often refers to:

* Spin (physics) or particle spin, a fundamental property of elementary particles

* Spin quantum number, a number which defines the value of a particle's spin

* Spinning (textiles), the creation of yarn or thr ...

. He published two papers on mesotrons with Kusaka in the Physical Review

''Physical Review'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal. The journal was established in 1893 by Edward Nichols. It publishes original research as well as scientific and literature reviews on all aspects of physics. It is published by the Ame ...

, which formed the basis of his 1941 Doctor of Philosophy

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, DPhil; or ) is a terminal degree that usually denotes the highest level of academic achievement in a given discipline and is awarded following a course of Postgraduate education, graduate study and original resear ...

(PhD) thesis

Manhattan Project

Christy could have graduated in 1940, but could not then be a teaching assistant, and this would have left him jobless and without income. In 1941, Oppenheimer found him a post at the physics department at

Christy could have graduated in 1940, but could not then be a teaching assistant, and this would have left him jobless and without income. In 1941, Oppenheimer found him a post at the physics department at Illinois Institute of Technology

The Illinois Institute of Technology, commonly referred to as Illinois Tech and IIT, is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Tracing its history to 1890, the present name was adopted upon the m ...

(IIT). In May 1941, he married Dagmar von Lieven. They had two sons: Thomas Edward (Ted), born in 1944, and Peter Robert, born in 1946. IIT paid Christy $200 per month to teach 27 hours per week for 11 months per annum. To keep abreast of developments in physics, he attended seminars at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, or UChi) is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Its main campus is in the Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, Chic ...

. This brought him to the attention of Eugene Wigner

Eugene Paul Wigner (, ; November 17, 1902 – January 1, 1995) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who also contributed to mathematical physics. He received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1963 "for his contributions to the theory of th ...

, who hired him for the same money that IIT was paying him but as a full-time research assistant, commencing in January 1942.

Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian and naturalized American physicist, renowned for being the creator of the world's first artificial nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1, and a member of the Manhattan Project ...

and his team from Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

arrived at the University of Chicago in January 1942 as part of an effort to concentrate the Manhattan Project's reactor work at the new Metallurgical Laboratory. Fermi arranged with Wigner for Christy to join his group, which was building a nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a Nuclear fission, fission nuclear chain reaction. They are used for Nuclear power, commercial electricity, nuclear marine propulsion, marine propulsion, Weapons-grade plutonium, weapons ...

, which Fermi called a "pile", in the squash court under Stagg Field

Amos Alonzo Stagg Field is the name of two successive football fields for the University of Chicago. Beyond sports, the first Stagg Field (1893–1957), named for famed coach, Alonzo Stagg, is remembered for its role in a landmark scientific ac ...

at the University of Chicago. Construction began on November 6, 1942, and Christy was present when Chicago Pile-1

Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1) was the first artificial nuclear reactor. On 2 December 1942, the first human-made self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was initiated in CP-1 during an experiment led by Enrico Fermi. The secret development of the react ...

went critical

Critical or Critically may refer to:

*Critical, or critical but stable, medical states

**Critical, or intensive care medicine

* Critical juncture, a discontinuous change studied in the social sciences.

*Critical Software, a company specializing i ...

on December 2.

In early 1943, Christy joined Oppenheimer's Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret scientific laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and overseen by the University of California during World War II. It was operated in partnership with the United State ...

in New Mexico, where he became an American citizen in 1943 or 1944. Hans Bethe

Hans Albrecht Eduard Bethe (; ; July 2, 1906 – March 6, 2005) was a German-American physicist who made major contributions to nuclear physics, astrophysics, quantum electrodynamics and solid-state physics, and received the Nobel Prize in Physi ...

, the head of T (Theoretical) Division, detailed his physicists to assist with the projects at the laboratory. With his knowledge of reactors, Christy's assignment was to help Donald W. Kerst's Water Boiler group. The Water Boiler was an aqueous homogeneous reactor

Aqueous homogeneous reactors (AHR) is a two (2) chamber reactor consisting of an interior reactor chamber and an outside cooling and moderating jacket chamber. They are a type of nuclear reactor in which soluble nuclear salts (usually uranium su ...

intended as a laboratory instrument to test critical mass

In nuclear engineering, critical mass is the minimum mass of the fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction in a particular setup. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specific ...

calculations and the effect of various tamper materials. It was the first reactor to use enriched uranium

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (23 ...

as a fuel, and the first to use liquid fuel in the form of soluble uranium sulfate dissolved in water. Christy estimated that it would require of pure uranium-235

Uranium-235 ( or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exists in nat ...

, a figure he subsequently revised to . When the reactor went critical on May 9, 1944, with , the accuracy of Christy's figures raised the laboratory's confidence in T Division's calculations.

The discovery by Emilio Segrè

Emilio Gino Segrè ( ; ; 1 February 1905 – 22 April 1989) was an Italian-American nuclear physicist and radiochemist who discovered the elements technetium and astatine, and the antiproton, a subatomic antiparticle, for which he was award ...

's group in April and May 1944 of high levels of plutonium-240

Plutonium-240 ( or Pu-240) is an isotope of plutonium formed when plutonium-239 captures a neutron. The detection of its spontaneous fission led to its discovery in 1944 at Los Alamos and had important consequences for the Manhattan Project.

...

in reactor-produced plutonium meant that an implosion-type nuclear weapon

Nuclear weapons design are physical, chemical, and engineering arrangements that cause the physics package of a nuclear weapon to detonate. There are three existing basic design types:

# Pure fission weapons are the simplest, least technically de ...

was required, but studies indicated that this would be extremely difficult to achieve. By August 1944, the calculations had been made of how an ideal spherical implosion would work; the problem was how to make it work in the real world where jets and spall

Spall are fragments of a material that are broken off a larger solid body. It can be produced by a variety of mechanisms, including as a result of projectile impact, corrosion, weathering, cavitation, or excessive rolling pressure (as in a ba ...

ing were a problem. Christy worked in Rudolf Peierls

Sir Rudolf Ernst Peierls, (; ; 5 June 1907 – 19 September 1995) was a German-born British physicist who played a major role in Tube Alloys, Britain's nuclear weapon programme, as well as the subsequent Manhattan Project, the combined Allied ...

's T-1 Group, which studied the theory of implosion. He suggested the possibility of using a solid plutonium core that would form a critical mass when compressed. This was an ultra-conservative design that solved the problem of jets by brute force. It became known as the " Christy pit" or "Christy gadget", "gadget" being the laboratory euphemism for a bomb. However the solid pit was intrinsically less efficient than a hollow pit, and it required a modulated neutron initiator

A modulated neutron initiator is a neutron source capable of producing a burst of neutrons on activation. It is a crucial part of some nuclear weapons, as its role is to "kick-start" the chain reaction at the optimal moment when the configuration i ...

to start the chain reaction. Christy worked with Klaus Fuchs

Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs (29 December 1911 – 28 January 1988) was a German theoretical physicist and atomic spy who supplied information from the American, British, and Canadian Manhattan Project to the Soviet Union during and shortly a ...

, Paul Stein and Hans Bethe to develop a suitable initiator design, which became known as an "urchin". The Gadget

Trinity was the first detonation of a nuclear weapon, conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. MWT (11:29:21 GMT) on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was of an implosion-design plutonium bomb, or "gadg ...

used in the Trinity nuclear test and the Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) was the design of the nuclear weapon the United States used for seven of the first eight nuclear weapons ever detonated in history. It is also the most powerful design to ever be used in warfare.

A Fat Man ...

used in the atomic bombing of Nagasaki

On 6 and 9 August 1945, the United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively, during World War II. The aerial bombings killed between 150,000 and 246,000 people, most of whom were civili ...

used Christy pits.

Later in life, Christy agreed to give a number of both oral history

Oral history is the collection and study of historical information from

people, families, important events, or everyday life using audiotapes, videotapes, or transcriptions of planned interviews. These interviews are conducted with people who pa ...

and video interviews in which he discussed his role in the Manhattan Project and latter interests.

Later life

After the war ended, Christy accepted an

After the war ended, Christy accepted an assistant professor

Assistant professor is an academic rank just below the rank of an associate professor used in universities or colleges, mainly in the United States, Canada, Japan, and South Korea.

Overview

This position is generally taken after earning a doct ...

ship at the University of Chicago, at a salary of $5,000 per annum, twice what he had been making before the war. He moved back to Chicago in February 1946, but suitable housing was hard to find in the immediate post-war period, and Christy and his family shared a mansion with Edward Teller

Edward Teller (; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian and American Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist and chemical engineer who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" and one of the creators of ...

and his family.

Before the war, Oppenheimer had spent part of each year teaching at California Institute of Technology

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech) is a private research university in Pasadena, California, United States. The university is responsible for many modern scientific advancements and is among a small group of institutes ...

(Caltech). Christy was one of Oppenheimer's Berkeley students who made the trip down to Pasadena, California

Pasadena ( ) is a city in Los Angeles County, California, United States, northeast of downtown Los Angeles. It is the most populous city and the primary cultural center of the San Gabriel Valley. Old Pasadena is the city's original commerci ...

, each year to continue studying with Oppenheimer. After the war, Oppenheimer decided that with his additional responsibilities he could no longer continue this arrangement. The head of the W. K. Kellogg Radiation Laboratory at Caltech, Charles Lauritsen therefore asked Oppenheimer for the name of a theoretical physicist that he would recommend as a replacement. Oppenheimer recommended Christy. Willy Fowler then approached Christy with an offer of a full-time position at Caltech at $5,400 per annum, and Christy accepted. He remained at Caltech for the rest of his academic career. The drawback to working at Caltech was that neither Lauritsen nor Fowler was a theoretical physicist, so a heavy workload fell on Christy. This was recognised by a pay raise to $10,000 per annum in 1954.

Christy joined Oppenheimer, Lauritsen and Robert Bacher

Robert Fox Bacher (August 31, 1905November 18, 2004) was an American nuclear physics, nuclear physicist and one of the leaders of the Manhattan Project. Born in Loudonville, Ohio, Bacher obtained his undergraduate degree and doctorate from the U ...

, who joined the faculty at Caltech in 1949, in Project Vista

Project Vista was a top secret study conducted by prominent physicists, researchers, military officers, and staff at California Institute of Technology from April 1 to December 1, 1951. The project got its name from the Vista del Arroyo Hotel i ...

, a detailed 1951 study on how Western Europe could be defended against the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. Christy was distraught at the outcome of the 1954 Oppenheimer security hearing

Over four weeks in 1954, the United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) explored the background, actions, and associations of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the American scientist who directed the Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II as part of t ...

. When he encountered Teller, who had testified against Oppenheimer, at Los Alamos in 1954, Christy publicly refused to shake Teller's hand. "I viewed Oppenheimer as a god", he later recalled, "and I was sure that he was not a treasonable person." Asked about his relationship with Teller in 2006, Christy said:

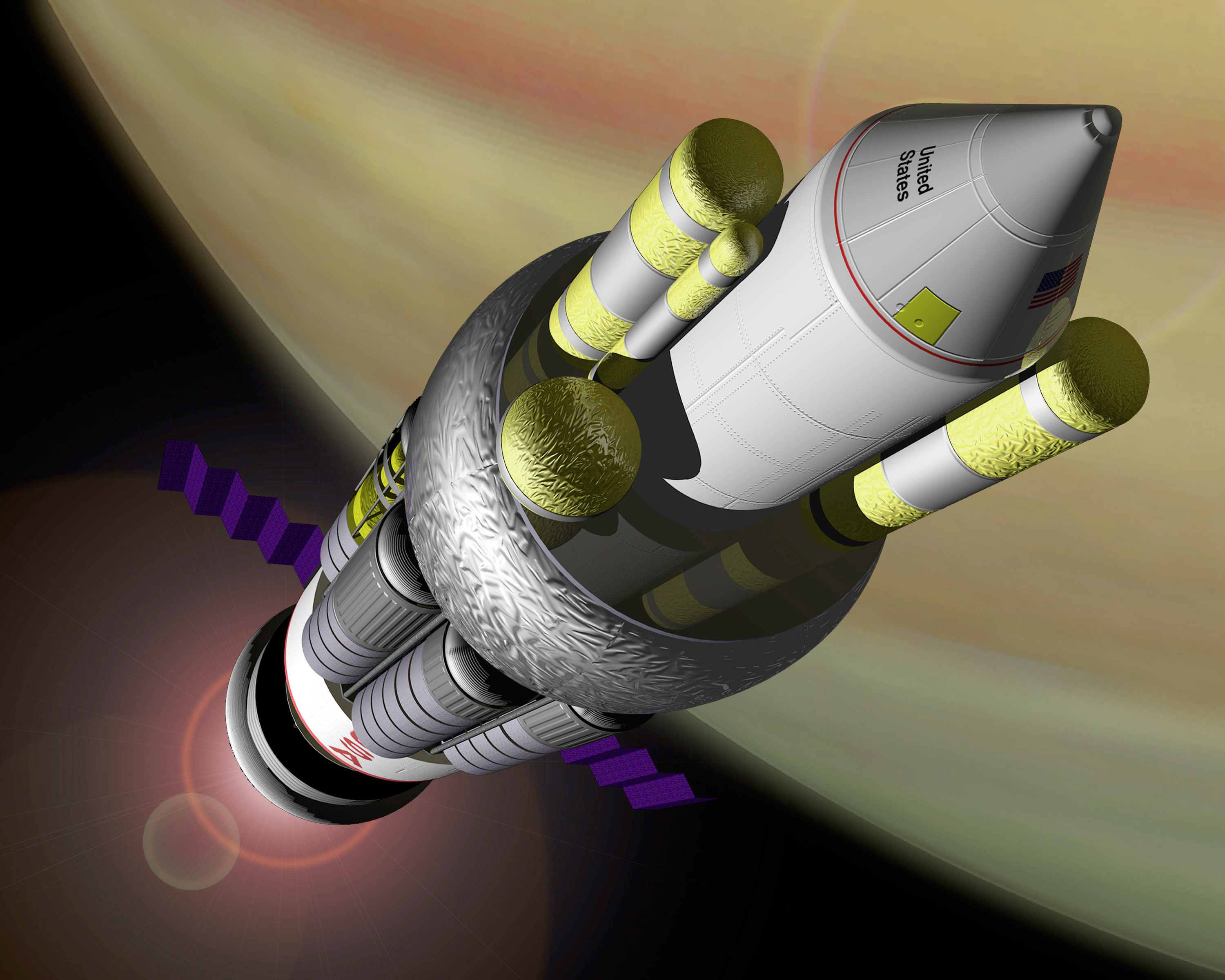

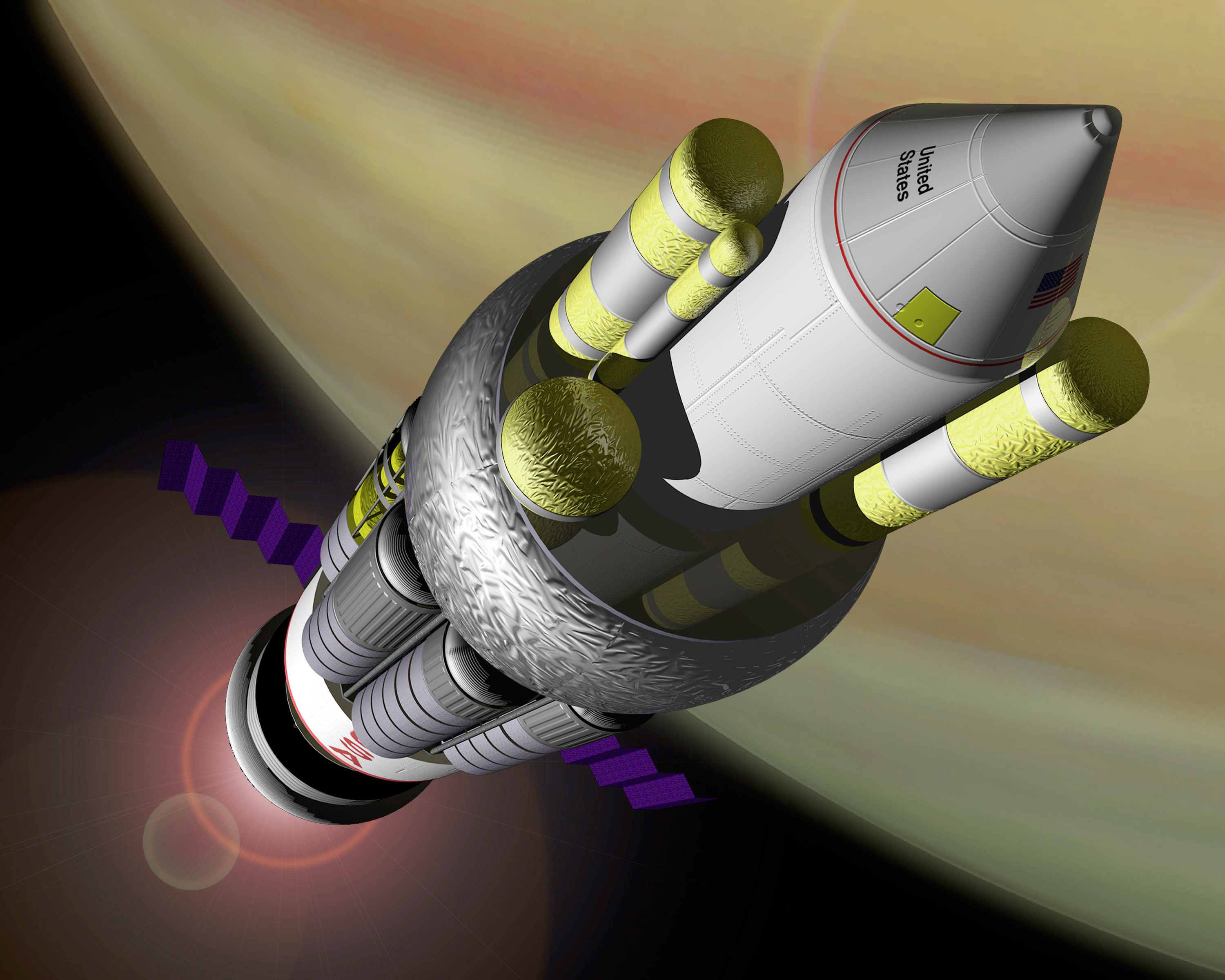

In 1956, Christy was one of a number of scientists from Caltech who publicly called for a ban on atmospheric nuclear testing. The 1963 Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty

The Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT), formally known as the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, prohibited all nuclear weapons testing, test detonations of nuclear weapons except for those co ...

that Christy advocated put an end to one of his most unusual projects. He worked with Freeman Dyson

Freeman John Dyson (15 December 1923 – 28 February 2020) was a British-American theoretical physics, theoretical physicist and mathematician known for his works in quantum field theory, astrophysics, random matrix, random matrices, math ...

on Project Orion, the design of a spacecraft propelled by atomic bombs.

During a sabbatical year at

During a sabbatical year at Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial ...

in 1960, Christy began an investigation of Cepheid variable

A Cepheid variable () is a type of variable star that pulsates radially, varying in both diameter and temperature. It changes in brightness, with a well-defined stable period (typically 1–100 days) and amplitude. Cepheids are important cosmi ...

s and the smaller RR Lyrae variable

RR Lyrae variables are periodic variable stars, commonly found in globular clusters. They are used as standard candles to measure (extra) galactic distances, assisting with the cosmic distance ladder. This class is named after the prototype a ...

s, classes of luminous variable stars

A variable star is a star whose brightness as seen from Earth (its apparent magnitude) changes systematically with time. This variation may be caused by a change in emitted light or by something partly blocking the light, so variable stars are ...

. At the time it was a mystery as to why they varied. He used the knowledge of the hydrodynamics

In physics, physical chemistry and engineering, fluid dynamics is a subdiscipline of fluid mechanics that describes the flow of fluids – liquids and gases. It has several subdisciplines, including (the study of air and other gases in ...

of implosion gained at Los Alamos during the war to explain this phenomenon. This earned him the Royal Astronomical Society

The Royal Astronomical Society (RAS) is a learned society and charitable organisation, charity that encourages and promotes the study of astronomy, planetary science, solar-system science, geophysics and closely related branches of science. Its ...

's Eddington Medal

The Eddington Medal is awarded by the Royal Astronomical Society for investigations of outstanding merit in theoretical astrophysics. It is named after Sir Arthur Eddington. First awarded in 1953, the frequency of the prize has varied over the ye ...

for contributions to theoretical astrophysics in 1967.

Christy was appointed vice president and Provost of Caltech in 1970. Under Christy and President Harold Brown Caltech expanded its humanities

Humanities are academic disciplines that study aspects of human society and culture, including Philosophy, certain fundamental questions asked by humans. During the Renaissance, the term "humanities" referred to the study of classical literature a ...

and added economics

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

to allow (or perhaps to compel—undergrads were required to take 25% of their units in "humanities") students to broaden their education. He had David Morrisroe appointed as vice president for Financial Affairs, and they steered Caltech through the financially stringent 1970s. The first women were admitted as undergraduates in Fall 1970.

When Jenijoy La Belle, who had been hired in 1969 but refused tenure in 1974, filed suit with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is a federal agency that was established via the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to administer and enforce civil rights laws against workplace discrimination. The EEOC investigates discrimination ...

, Christy pressed for the case to be settled and La Belle to be given tenure. The EEOC ruled against Caltech in 1977, adding that she had been paid less than male colleagues. La Belle received tenure in 1979.

In 1970 he became romantically involved with Inge-Juliana Sackman, a fellow physicist 26 years his junior. He divorced Dagmar in early 1971, and married Juliana on August 4, 1973. They had two daughters, Illia Juliana Lilly Christy, born in 1974, and Alexandra Roberta (Alexa) Christy, born in 1976.

Christy briefly became acting President of Caltech in 1977 when Brown left to become Secretary of Defense. Christy returned to teaching after Marvin L. Goldberger became president in 1978. He became Institute Professor of Theoretical Physics in 1983, and Institute Professor Emeritus in 1986.

Christy died on October 3, 2012. He was survived by his wife Juliana, their two daughters, Illia and Alexa, and his two sons, Peter and Ted. He was buried at Mountain View Cemetery in Altadena, California

Altadena () is an unincorporated area, and census-designated place in the San Gabriel Valley and the Verdugos regions of Los Angeles County, California. Directly north of Pasadena, California, Pasadena, it is located approximately from Downtow ...

.

Notes

References

* * *External links

1983 Audio Interview with Robert Christy by Martin Sherwin

Voices of the Manhattan Project *

Interview with Robert F. Christy

Caltech Oral Histories, Caltech Archives, California Institute of Technology. {{DEFAULTSORT:Christy, Robert 1916 births 2012 deaths American astrophysicists 20th-century American astronomers Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Presidents of the California Institute of Technology Manhattan Project people University of Chicago faculty University of British Columbia Faculty of Science alumni UC Berkeley College of Letters and Science alumni Fellows of the American Physical Society Canadian emigrants to the United States