Richard Price on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Richard Price (23 February 1723 – 19 April 1791) was a British moral philosopher, Nonconformist minister and mathematician. He was also a political reformer and

Born on 23 February 1723, Richard Price was the son of Rhys Price, a dissenting minister. His mother was Catherine Richards, his father's second wife. Richard was born at Tyn Ton, a farmhouse in the village of Llangeinor,

Born on 23 February 1723, Richard Price was the son of Rhys Price, a dissenting minister. His mother was Catherine Richards, his father's second wife. Richard was born at Tyn Ton, a farmhouse in the village of Llangeinor,

Others acknowledged their debt to Price, such as the Unitarian theologians William Ellery Channing and Theophilus Lindsey. When Lindsey resigned his living and moved to London to create an avowedly Unitarian congregation Price played a role in finding and securing the premises for what became Essex Street Chapel. At the end of the 1770s Price and Lindsey were concerned about the contraction of dissent, at least in the London area. With Andrew Kippis and others, they established the Society for Promoting Knowledge of the Scriptures in 1783.

Price and Priestley took diverging views on morals and

Others acknowledged their debt to Price, such as the Unitarian theologians William Ellery Channing and Theophilus Lindsey. When Lindsey resigned his living and moved to London to create an avowedly Unitarian congregation Price played a role in finding and securing the premises for what became Essex Street Chapel. At the end of the 1770s Price and Lindsey were concerned about the contraction of dissent, at least in the London area. With Andrew Kippis and others, they established the Society for Promoting Knowledge of the Scriptures in 1783.

Price and Priestley took diverging views on morals and

Both Price and Priestley, who were millennialists, saw the French Revolution of 1789 as fulfilment of prophecy. On the 101st anniversary of the

Both Price and Priestley, who were millennialists, saw the French Revolution of 1789 as fulfilment of prophecy. On the 101st anniversary of the

commemorates Price in multiple ways.

Royal Society certificate of election

Readable version of Price's ''Review of the Principal Questions of Morals''

Price's ''Observations on Civil Liberty and the Justice and Policy of the War with America''

*

Price's ''Observations on reversionary payments on schemes for providing annuities for widows, and for persons in old age; on the method of calculating the values of assurances on lives; and on the national debt : to which are added four essays ... also an appendix ...'', published in 1771

{{DEFAULTSORT:Price, Richard 1723 births 1791 deaths 18th-century British philosophers 18th-century English male writers 18th-century Unitarian clergy 18th-century Welsh educators 18th-century Welsh writers Anti-monarchists Burials at Bunhill Fields 18th-century English philosophers English Unitarians Enlightenment philosophers Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Fellows of the Royal Society People from Bridgend County Borough Welsh actuaries Welsh philosophers Welsh statisticians Welsh Unitarians International members of the American Philosophical Society

pamphleteer

A pamphleteer is a historical term used to describe someone who creates or distributes pamphlets, unbound (therefore inexpensive) booklets intended for wide circulation.

Context

Pamphlets were used to broadcast the writer's opinions: to articu ...

, active in radical, republican, and liberal causes such as the French and American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

s. He was well-connected and fostered communication between many people, including Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

, John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before Presidency of John Adams, his presidency, he was a leader of ...

, George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

, Mirabeau and the Marquis de Condorcet

Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis of Condorcet (; ; 17 September 1743 – 29 March 1794), known as Nicolas de Condorcet, was a French Philosophy, philosopher, Political economy, political economist, Politics, politician, and m ...

. According to the historian John Davies, Price was "the greatest Welsh thinker of all time".

Born in Llangeinor, near Bridgend

Bridgend (; or just , meaning "the end of the bridge on the Ogmore") is a town in the Bridgend County Borough of Wales, west of Cardiff and east of Swansea. The town is named after the Old Bridge, Bridgend, medieval bridge over the River Og ...

, Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

, Price spent most of his adult life as minister of Newington Green Unitarian Church, then on the outskirts of London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

. He edited, published and developed the Bayes–Price theorem and the field of actuarial science

Actuarial science is the discipline that applies mathematics, mathematical and statistics, statistical methods to Risk assessment, assess risk in insurance, pension, finance, investment and other industries and professions.

Actuary, Actuaries a ...

. He also wrote on issues of demography

Demography () is the statistical study of human populations: their size, composition (e.g., ethnic group, age), and how they change through the interplay of fertility (births), mortality (deaths), and migration.

Demographic analysis examine ...

and finance

Finance refers to monetary resources and to the study and Academic discipline, discipline of money, currency, assets and Liability (financial accounting), liabilities. As a subject of study, is a field of Business administration, Business Admin ...

, and was a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the Fellows of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

.

Early life

Born on 23 February 1723, Richard Price was the son of Rhys Price, a dissenting minister. His mother was Catherine Richards, his father's second wife. Richard was born at Tyn Ton, a farmhouse in the village of Llangeinor,

Born on 23 February 1723, Richard Price was the son of Rhys Price, a dissenting minister. His mother was Catherine Richards, his father's second wife. Richard was born at Tyn Ton, a farmhouse in the village of Llangeinor, Glamorgan

Glamorgan (), or sometimes Glamorganshire ( or ), was Historic counties of Wales, one of the thirteen counties of Wales that existed from 1536 until their abolishment in 1974. It is located in the South Wales, south of Wales. Originally an ea ...

. He was educated privately, then at Neath

Neath (; ) is a market town and Community (Wales), community situated in the Neath Port Talbot, Neath Port Talbot County Borough, Wales. The town had a population of 50,658 in 2011. The community of the parish of Neath had a population of 19,2 ...

and Pen-twyn. He studied under Vavasor Griffiths at Chancefield, Talgarth

Talgarth is a market town, community (Wales), community and electoral ward in southern Powys, Mid Wales, about north of Crickhowell, north-east of Brecon and south-east of Builth Wells. Notable buildings in the town include the 14th-century ...

, Powys

Powys ( , ) is a Principal areas of Wales, county and Preserved counties of Wales, preserved county in Wales. It borders Gwynedd, Denbighshire, and Wrexham County Borough, Wrexham to the north; the English Ceremonial counties of England, ceremo ...

.

He then moved to London, where he spent the rest of his life. He studied with John Eames and the dissenting academy in Moorfields, London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

. Leaving the academy in 1744, Price became chaplain and companion to George Streatfield at Stoke Newington

Stoke Newington is an area in the northwest part of the London Borough of Hackney, England. The area is northeast of Charing Cross. The Manor of Stoke Newington gave its name to Stoke Newington (parish), Stoke Newington, the ancient parish. S ...

, then a village just north of London. He also held the lectureship at Old Jewry, where Samuel Chandler was minister. Streatfield's death and that of an uncle in 1757 improved Price's circumstances, and on 16 June 1757 he married Sarah Blundell, originally of Belgrave in Leicestershire

Leicestershire ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It is bordered by Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire to the north, Rutland to the east, Northamptonshire to the south-east, Warw ...

..

Newington Green congregation

In 1758, Price moved to Newington Green, and took up residence in No. 54 the Green, in the middle of a terrace that was even then a hundred years old. (The building still survives as London's oldest brick terrace, dated 1658.) Price became minister to the Newington Green meeting-house, a church that continues today as Newington Green Unitarian Church. Among the congregation were Samuel Vaughan and his family. Price had Thomas Amory as preaching colleague from 1770. When, in 1770, Price became morning preacher at the Gravel Pit Chapel in Hackney, he continued his afternoon sermons at Newington Green. He also accepted duties at the meeting house in Old Jewry.Friends and associates

Newington Green neighbours

A close friend of Price was Thomas Rogers, father of Samuel Rogers, a merchant turned banker who had married into a long-established Dissenting family and lived at No. 56 the Green. More than once, Price and the elder Rogers rode on horseback to Wales. Another was the Rev. James Burgh, author of ''The Dignity of Human Nature'' and ''Thoughts on Education'', who opened his Dissenting Academy on the Green in 1750 and sent his pupils to Price's sermons. Price, Rogers, and Burgh formed a dining club, eating at each other's houses in rotation. Price and Rogers joined the Society for Constitutional Information.Bowood circle

The "Bowood circle" was a group of liberal intellectuals aroundLord Shelburne

William Petty Fitzmaurice, 1st Marquess of Lansdowne (2 May 17377 May 1805), known as the Earl of Shelburne between 1761 and 1784, by which title he is generally known to history, was an Anglo-Irish Whig statesman who was the first home secr ...

, and named after Bowood House, his seat in Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated to Wilts) is a ceremonial county in South West England. It borders Gloucestershire to the north, Oxfordshire to the north-east, Berkshire to the east, Hampshire to the south-east, Dorset to the south, and Somerset to ...

. Price met Shelburne in or shortly after 1767, or was introduced by his wife Elizabeth Montagu, a leader of the Blue Stocking intellectual women, after the publication of his ''Four Dissertations'' in that year.Holland, p. 48.

In 1771, Price had Shelburne employ Thomas Jervis. Another member of the circle was Benjamin Vaughan. In 1772, Price recruited Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, Unitarian, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher, English Separatist, separatist theologian, Linguist, grammarian, multi-subject educator and Classical libera ...

, who came to work for Shelburne as librarian from 1773.

"Club of Honest Whigs"

The group thatBenjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

christened the "Club of Honest Whigs" was an informal dining group around John Canton. It met originally in St Paul's Churchyard, at the London Coffee House; in 1771 it moved to Ludgate Hill

Ludgate Hill is a street and surrounding area, on a small hill in the City of London, England. The street passes through the former site of Ludgate, a city gate that was demolished – along with a gaol attached to it – in 1760.

Th ...

. Price and Sir John Pringle were members, as were Priestley and Benjamin Vaughan.

Visitors

Price was visited by Franklin,Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

, and Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In ...

; other American politicians such as John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before Presidency of John Adams, his presidency, he was a leader of ...

, who later became the second president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

, and his wife Abigail; and British politicians such as Lord Lyttleton, Lord Stanhope (known as "Citizen Stanhope"), and William Pitt the Elder. He knew also the philosophers David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

and Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

. Among activists, the prison reformer John Howard counted Price as a close friend; also there were John Horne Tooke, and John and Ann Jebb.Thorncroft, p. 15.

Theologians

Others acknowledged their debt to Price, such as the Unitarian theologians William Ellery Channing and Theophilus Lindsey. When Lindsey resigned his living and moved to London to create an avowedly Unitarian congregation Price played a role in finding and securing the premises for what became Essex Street Chapel. At the end of the 1770s Price and Lindsey were concerned about the contraction of dissent, at least in the London area. With Andrew Kippis and others, they established the Society for Promoting Knowledge of the Scriptures in 1783.

Price and Priestley took diverging views on morals and

Others acknowledged their debt to Price, such as the Unitarian theologians William Ellery Channing and Theophilus Lindsey. When Lindsey resigned his living and moved to London to create an avowedly Unitarian congregation Price played a role in finding and securing the premises for what became Essex Street Chapel. At the end of the 1770s Price and Lindsey were concerned about the contraction of dissent, at least in the London area. With Andrew Kippis and others, they established the Society for Promoting Knowledge of the Scriptures in 1783.

Price and Priestley took diverging views on morals and metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

. In 1778 appeared a published correspondence, ''A Free Discussion on the Doctrines of Materialism and Philosophical Necessity''. Price maintained, in opposition to Priestley, the free agency of man and the unity and immateriality of the human soul. Price's opinions were Arian, Priestley's were Socinian.

Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft moved her fledgling school for girls fromIslington

Islington ( ) is an inner-city area of north London, England, within the wider London Borough of Islington. It is a mainly residential district of Inner London, extending from Islington's #Islington High Street, High Street to Highbury Fields ...

to Newington Green in 1784, with patron Mrs Burgh, widow of Price's friend James Burgh. Wollstonecraft, originally an Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

, attended Price's services, where believers of all kinds were welcomed.Tomalin, p. 60. The Rational Dissenters appealed to Wollstonecraft: they were hard-working, humane, critical but uncynical, and respectful towards women, and proved kinder to her than her own family. Price is believed to have helped her with money to go to Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

, Spain, to see her close friend Fanny Blood.

Wollstonecraft was then unpublished: through Price she met the radical publisher Joseph Johnson. The ideas Wollstonecraft ingested from the sermons at Newington Green pushed her towards a political awakening. She later published '' A Vindication of the Rights of Men'' (1790), a response to Burke's denunciation of the French Revolution and attack on Price; and '' A Vindication of the Rights of Woman'' (1792), extending Price's arguments about equality to women: Tomalin argues that just as the Dissenters were "excluded as a class from education and civil rights by a lazy-minded majority", so too were women, and the "character defects of both groups" could be attributed to this discrimination. Price appears 14 times in the diary of William Godwin

William Godwin (3 March 1756 – 7 April 1836) was an English journalist, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism and the first modern proponent of anarchism. Godwin is most famous fo ...

, Wollstonecraft's later husband.

American Revolution

The support Price gave to the colonies ofBritish North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestown, ...

in the American War of Independence made him famous. In early 1776, he published the pamphlet ''Observations on the Nature of Civil Liberty, the Principles of Government, and the Justice and Policy of the War with America''. Sixty thousand copies of this pamphlet were sold within days; and a cheap edition was issued which sold twice as many copies. Plumb, J. H., ''England in the Eighteenth Century'' (Middlesex: Penguin Books Ltd, 1950). It commended Shelburne's proposals for the colonies, and attacked the Declaratory Act. Additionally, he denounced the "cruel, wicked and diabolical" slave trade while highlighting the contradictions in Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

's Declaration of Independence, stating, “if there are any men whom they have a right to hold in slavery, there may be others who have a right to hold them in slavery.” Among its critics were Adam Ferguson, William Markham, John Wesley

John Wesley ( ; 2 March 1791) was an English cleric, Christian theology, theologian, and Evangelism, evangelist who was a principal leader of a Christian revival, revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism. The societies ...

, and Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January ew Style, NS1729 – 9 July 1797) was an Anglo-Irish Politician, statesman, journalist, writer, literary critic, philosopher, and parliamentary orator who is regarded as the founder of the Social philosophy, soc ...

; and Price rapidly became one of the best known men in England. He was presented with the freedom of the city of London, and it is said that his pamphlet had a part in determining the Americans to declare their independence. A second pamphlet, ''Additional observations on the nature and value of civil liberty, and the war with America'', followed. Price was a consistent critic of war in general and the corrupting effects of growing government debt.

Price's name became identified with the cause of American independence. Franklin was a close friend; Price corresponded with Turgot; and in the winter of 1778 Price was invited by the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislature, legislative bodies, with some executive function, for the Thirteen Colonies of British America, Great Britain in North America, and the newly declared United States before, during, and after ...

to go to America and assist in the financial administration of the states, an offer he turned down. In 1781 he, solely with George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

, received the degree of Doctor of Laws from Yale College

Yale College is the undergraduate college of Yale University. Founded in 1701, it is the original school of the university. Although other Yale schools were founded as early as 1810, all of Yale was officially known as Yale College until 1887, ...

. He preached to crowded congregations, and, when Lord Shelburne became Prime Minister in 1782, he was offered the post of his private secretary. The same year he was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

. In 1785, Price was elected an international member of the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS) is an American scholarly organization and learned society founded in 1743 in Philadelphia that promotes knowledge in the humanities and natural sciences through research, professional meetings, publicat ...

.

Price wrote also ''Observations on the importance of the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

and the means of rendering it a benefit to the World'' (1784). Well received by Americans, it suggested that the greatest problem facing Congress was its lack of central powers.

French Revolution controversy

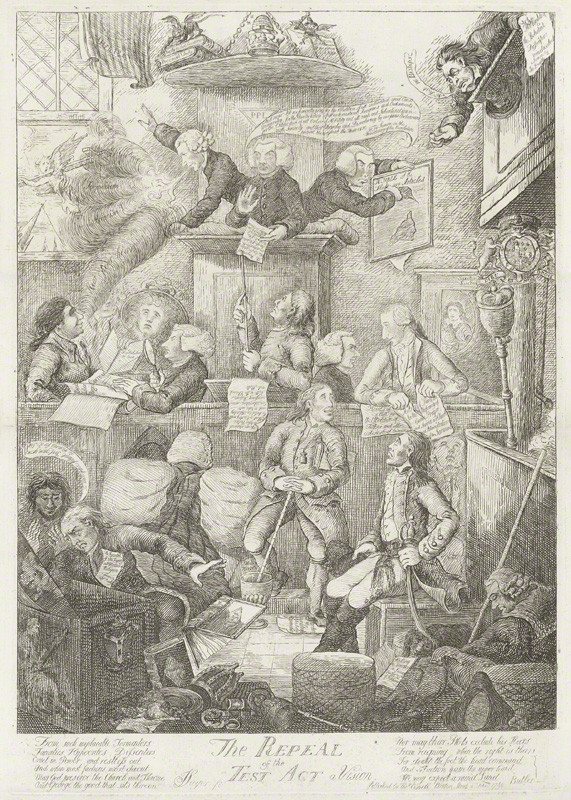

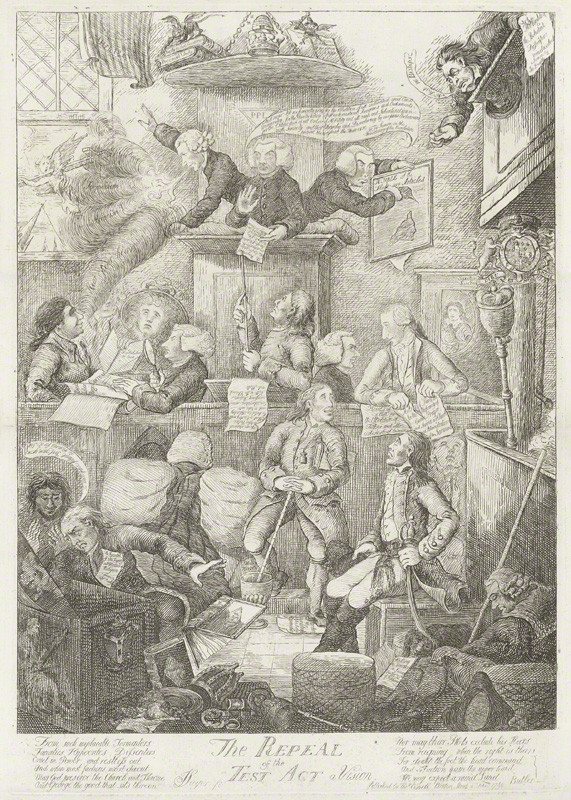

Both Price and Priestley, who were millennialists, saw the French Revolution of 1789 as fulfilment of prophecy. On the 101st anniversary of the

Both Price and Priestley, who were millennialists, saw the French Revolution of 1789 as fulfilment of prophecy. On the 101st anniversary of the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also known as the Revolution of 1688, was the deposition of James II and VII, James II and VII in November 1688. He was replaced by his daughter Mary II, Mary II and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange ...

, 4 November 1789, Price preached a sermon

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present context ...

entitled '' A Discourse on the Love of Our Country'', and ignited the pamphlet war known as the Revolution Controversy, on the political issues raised by the French Revolution. Price drew a bold parallel between the Glorious Revolution of 1688 (the one celebrated by the London Revolution Society dinner) and the French Revolution of 1789, arguing that the former had spread enlightened ideas and paved the way for the second one. Price exhorted the public to divest themselves of national prejudices and embrace "universal benevolence", a concept of cosmopolitanism that entailed support for the French Revolution and the progress of "enlightened" ideas. It has been called "one of the great political debates in British history". At the dinner of the London Revolution Society that followed, Price also suggested that the Society should send an address to the National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repr ...

in Paris. This was the start of a correspondence with many Jacobin clubs in Paris and elsewhere in France. Though the London Revolution Society and the Jacobin clubs agreed on basic tenets, their correspondence displayed a sense of growing misunderstanding as the French Jacobins grew more radical and their British correspondents, including Price, were not prepared to condone political violence. The Society's Committee of Correspondence, which included Michael Dodson, took up the contact that was made with French Jacobins

The Society of the Friends of the Constitution (), renamed the Society of the Jacobins, Friends of Freedom and Equality () after 1792 and commonly known as the Jacobin Club () or simply the Jacobins (; ), was the most influential List of polit ...

, though Price himself withdrew. At the same time, the Revolution Society joined with the Society for Constitutional Information in December 1789, at Price's insistence, in condemning the Test Act and Corporation Act as defacing the British polity, with their restrictions on Dissenters.

Burke's rebuttal in '' Reflections on the Revolution in France'' (1790) attacked Price, whose friends Paine and Wollstonecraft leapt into the fray to defend their mentor; William Coxe was another opponent, disagreeing with Price on interpretation of "our country". In 1792 Christopher Wyvill published ''Defence of Dr. Price and the Reformers of England'', a plea for reform and moderation.

Later life

In 1767 Price received the honorary degree of D.D. from theUniversity of Aberdeen

The University of Aberdeen (abbreviated ''Aberd.'' in List of post-nominal letters (United Kingdom), post-nominals; ) is a public university, public research university in Aberdeen, Scotland. It was founded in 1495 when William Elphinstone, Bis ...

, and in 1769 another from the University of Glasgow

The University of Glasgow (abbreviated as ''Glas.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals; ) is a Public university, public research university in Glasgow, Scotland. Founded by papal bull in , it is the List of oldest universities in continuous ...

. In 1786 Sarah Price died, and there had been no children by the marriage.

In the same year Price with other Dissenters founded Hackney New College. On 19 April 1791 Price died. He was buried at Bunhill Fields, where his funeral sermon was preached by Joseph Priestley.

His extended family included William Morgan, the actuary, and his brother George Cadogan Morgan (1754–1798), dissenting minister and scientist, both sons of Richard Price's sister Sarah by William Morgan, a surgeon of Bridgend

Bridgend (; or just , meaning "the end of the bridge on the Ogmore") is a town in the Bridgend County Borough of Wales, west of Cardiff and east of Swansea. The town is named after the Old Bridge, Bridgend, medieval bridge over the River Og ...

, Glamorganshire.

Publications

In 1744 Price published a volume of sermons. It was, however, as a writer on financial and political questions that Price became widely known. Price rejected traditional Christian notions oforiginal sin

Original sin () in Christian theology refers to the condition of sinfulness that all humans share, which is inherited from Adam and Eve due to the Fall of man, Fall, involving the loss of original righteousness and the distortion of the Image ...

and moral punishment, preaching the perfectibility of human nature, and he wrote on theological questions. He also wrote on finance

Finance refers to monetary resources and to the study and Academic discipline, discipline of money, currency, assets and Liability (financial accounting), liabilities. As a subject of study, is a field of Business administration, Business Admin ...

, economics

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

, probability

Probability is a branch of mathematics and statistics concerning events and numerical descriptions of how likely they are to occur. The probability of an event is a number between 0 and 1; the larger the probability, the more likely an e ...

, and life insurance

Life insurance (or life assurance, especially in the Commonwealth of Nations) is a contract

A contract is an agreement that specifies certain legally enforceable rights and obligations pertaining to two or more parties. A contract typical ...

.

Thomas Bayes

Price was asked to becomeliterary executor

The literary estate of a deceased author consists mainly of the copyright and other intellectual property rights of published works, including film rights, film, translation rights, original manuscripts of published work, unpublished or partially ...

of Thomas Bayes

Thomas Bayes ( , ; 7 April 1761) was an English statistician, philosopher and Presbyterian minister who is known for formulating a specific case of the theorem that bears his name: Bayes' theorem.

Bayes never published what would become his m ...

, the mathematician.Holland, pp. 46–47. He edited Bayes's major work ''An Essay Towards Solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances

"An Essay Towards Solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances" is a work on the mathematical theory of probability by Thomas Bayes, published in 1763, two years after its author's death, and containing multiple amendments and additions due to his ...

'' (1763), which appeared in ''Philosophical Transactions

''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society'' is a scientific journal published by the Royal Society. In its earliest days, it was a private venture of the Royal Society's secretary. It was established in 1665, making it the second journ ...

'', and contains Bayes' Theorem

Bayes' theorem (alternatively Bayes' law or Bayes' rule, after Thomas Bayes) gives a mathematical rule for inverting Conditional probability, conditional probabilities, allowing one to find the probability of a cause given its effect. For exampl ...

, one of the fundamental results of probability theory

Probability theory or probability calculus is the branch of mathematics concerned with probability. Although there are several different probability interpretations, probability theory treats the concept in a rigorous mathematical manner by expre ...

. Price wrote an introduction to the paper, which provides some of the philosophical basis of Bayesian statistics

Bayesian statistics ( or ) is a theory in the field of statistics based on the Bayesian interpretation of probability, where probability expresses a ''degree of belief'' in an event. The degree of belief may be based on prior knowledge about ...

. In 1765, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in recognition of his work on the legacy of Bayes.

Demographer

From about 1766 Price worked with the Society for Equitable Assurances. In 1769, in a letter toBenjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

, he made some observations on life expectancy

Human life expectancy is a statistical measure of the estimate of the average remaining years of life at a given age. The most commonly used measure is ''life expectancy at birth'' (LEB, or in demographic notation ''e''0, where '' ...

, and the population of London, which were published in the ''Philosophical Transactions'' of that year. Price's views included the detrimental effects of large cities, and the need for some constraints on commerce and movement of population.

In particular, Price took an interest in the figures of Franklin and Ezra Stiles on the colonial population in America, thought in some places to be doubling every 22 years. A debate on the British population had begun in the 1750s (with William Brakenridge, Richard Forster, Robert Wallace who pointed to manufacturing and smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

as factors reducing population, and William Bell), but was inconclusive in the face of a lack of sound figures. The issue was of interest to European writers generally. The quantitative form of Price's theory on the contrasting depopulation in England and Wales amounted to an approximate drop in population of 25 per cent since 1688. It was disputed numerically by Arthur Young in his ''Political Arithmetic'' (1774), which took in also criticism of the physiocrats.

In May 1770 Price presented to the Royal Society a paper on the proper method of calculating the values of contingent reversions. His book ''Observations on Reversionary Payments'' (1771) became a classic, in use for about a century, and providing the basis for financial calculations of insurance and benefit societies, of which many had recently been formed. The "Northampton table", a life table compiled by Price with data from Northampton

Northampton ( ) is a town and civil parish in Northamptonshire, England. It is the county town of Northamptonshire and the administrative centre of the Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority of West Northamptonshire. The town is sit ...

, became standard for about a century in actuarial work. It was used by life insurance companies such as Scottish Widows and Clerical Medical. It, too, overestimated mortality. In consequence, it was good for the insurance business, and adverse for those purchasing annuities. Price's nephew William Morgan was an actuary

An actuary is a professional with advanced mathematical skills who deals with the measurement and management of risk and uncertainty. These risks can affect both sides of the balance sheet and require investment management, asset management, ...

, and became manager of the Equitable in 1775. He later wrote a memoir of Price's life.

Price wrote a further ''Essay on the Population of England'' (2nd edition, 1780), which influenced Thomas Robert Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English economist, cleric, and scholar influential in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book ''An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

. Price's continuing claim in it on British depopulation was challenged by John Howlett in 1781. Investigation of actual causes of ill-health began at this period, in a group of radical physicians around Priestley, including Price but centred on the Midlands and north-west: with John Aikin, Matthew Dobson, John Haygarth and Thomas Percival

Thomas Percival (29 September 1740 – 30 August 1804) was an English physician, health reformer, ethicist and author who wrote an early code of medical ethics. He drew up a pamphlet with the code in 1794 and wrote an expanded version in 180 ...

. Of these Haygarth and Percival supplied Price with figures, to supplement those he had collected himself in Northampton parishes.

Public finance

In 1771 Price published his ''Appeal to the Public on the Subject of the National Debt'' (ed. 1772 and 1774). This pamphlet excited considerable controversy, and is supposed to have influencedWilliam Pitt the Younger

William Pitt (28 May 1759 – 23 January 1806) was a British statesman who served as the last prime minister of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain from 1783 until the Acts of Union 1800, and then first Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, p ...

in re-establishing the sinking fund for the extinction of the national debt, created by Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford (; 26 August 1676 – 18 March 1745), known between 1725 and 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole, was a British Whigs (British political party), Whig statesman who is generally regarded as the ''de facto'' first Prim ...

in 1716 and abolished in 1733. The means proposed for the extinction of the debt are described by Lord Overstone as "a sort of hocus-pocus machinery," supposed to work "without loss to any one," and consequently unsound. Price's views were attacked by John Brand in 1776. When Brand returned to finance and fiscal matters, ''Alteration of the Constitution of the House of Commons and the Inequality of the Land Tax'' (1793), he used work of Price, among others.

Moral philosophy

The ''Review of the Principal Questions in Morals'' (1758, 3rd ed. revised 1787) contains Price's theory ofethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

. The work is supposedly a refutation of Francis Hutcheson. Price represented a different tradition, deontological ethics

In moral philosophy, deontological ethics or deontology (from Greek: and ) is the normative ethical theory that the morality of an action should be based on whether that action itself is right or wrong under a series of rules and principles, ...

rather than the virtue ethics

Virtue ethics (also aretaic ethics, from Greek []) is a philosophical approach that treats virtue and moral character, character as the primary subjects of ethics, in contrast to other ethical systems that put consequences of voluntary acts, pri ...

of Hutcheson, going back to Samuel Clarke

Samuel Clarke (11 October 1675 – 17 May 1729) was an English philosopher and Anglican cleric. He is considered the major British figure in philosophy between John Locke and George Berkeley. Clarke's altered, Nontrinitarian revision of the 1 ...

and John Balguy. The book is divided into ten chapters, the first of which gives his main ethical theory, allied to that of Ralph Cudworth. Other chapters show his relation to Joseph Butler

Joseph Butler (18 May 1692 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. – 16 June 1752 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) was an English Anglican bishop, Christian theology, theologian, apologist, and philosopher, born in Wantage in the English count ...

and Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

. Philosophically and politically Price had something in common with Thomas Reid

Thomas Reid (; 7 May (Julian calendar, O.S. 26 April) 1710 – 7 October 1796) was a religiously trained Scotland, Scottish philosophy, philosopher best known for his philosophical method, his #Thomas_Reid's_theory_of_common_sense, theory of ...

. As a moralist Price is now regarded as a precursor to the rational intuitionism of the 20th century. He drew, among other sources, on Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

and Panaetius, and has been labelled a "British Platonist".

J. G. A. Pocock comments that Price was a moralist first, putting morality well ahead of democratic attachments. Price was widely criticised for that and for an absence of interest in civil society. As well as Burke, John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before Presidency of John Adams, his presidency, he was a leader of ...

, Adam Ferguson and Josiah Tucker wrote against him. James Mackintosh wrote that Price was attempting to revive moral obligation. Théodore Simon Jouffroy preferred Price to Cudworth, Reid and Dugald Stewart. See also William Whewell's ''History of Moral Philosophy in England''; Alexander Bain (philosopher), Alexander Bain's ''Mental and Moral Sciences''; and Thomas Fowler (academic), Thomas Fowler's monograph on Shaftesbury and Hutcheson.

For Price, right and wrong belong to actions in themselves, and he rejects consequentialism. This ethical value is perceived by reason or understanding, which intuitively recognizes fitness or congruity between actions, agents and total circumstances. Arguing that ethical judgment is an act of discrimination, he endeavours to invalidate moral sense theory. He admits that right actions must be "grateful" to us; that, in fact, moral approbation includes both an act of the understanding and an emotion of the heart. Still it remains true that reason alone, in its highest development, would be a sufficient guide. In this conclusion he is in close agreement with Kant; reason is the arbiter, and right is

# not a matter of the emotions and

# no relative to imperfect human nature.

Price's main point of difference with Cudworth is that while Cudworth regards the moral criterion as a νόημα or modification of the mind, existing in germ and developed by circumstances, Price regards it as acquired from the contemplation of actions, but acquired necessarily, immediately intuitively. In his view of disinterested action (ch. iii.) he follows Butler. Happiness he regards as the only end, conceivable by us, of divine Providence, but it is a happiness wholly dependent on rectitude. Virtue tends always to happiness, and in the end must produce it in its perfect form.

Other works

Price also wrote ''Fast-day Sermons'', published respectively in 1779 and 1781. Throughout the American War, he preached sermons on fast-days and took the opportunity to attack Britain's coercive policies toward the colonies. A complete list of his works was given as an appendix to Priestley's ''Funeral Sermon''.Commemoration

Spray paint and laser cut stencil images of Price created by the artist Stewy were installed on the exterior wall of the John Percival Building at Cardiff University in 2022 in anticipation of the 300th anniversary of Price's birth. In February 2023, an English Heritage blue plaque in honour of Price was installed on a wall at 54 Newington Green, where he lived, and close to the Newington Green Nonconformist chapel where he was a pastor. The plaque was unveiled by newsreader and journalist Huw Edwards. A series of events to celebrate Price's tercentenary in 2023 has been organised in Llangeinor, his place of birth, around Wales and in London.The Richard Price Societycommemorates Price in multiple ways.

See also

* Liberalism * Contributions to liberal theoryNotes

Attribution *References

* * *Further reading

* * * * Lyndall Gordon, Gordon, Lyndall (2005). ''Vindication: A Life of Mary Wollstonecraft''. Little, Brown. . * Jacobs, Diane (2001). ''Her Own Woman: The Life of Mary Wollstonecraft''. Simon & Schuster. . * * * Barbara Taylor (historian), Taylor, Barbara (2003). ''Mary Wollstonecraft and the Feminist Imagination''. Cambridge University Press. . * * * Thorncroft, Michael (1958). ''Trust in Freedom: The Story of Newington Green Unitarian Church, 1708–1958''. Trustees of the Unitarian Church. * *External links

*Royal Society certificate of election

Readable version of Price's ''Review of the Principal Questions of Morals''

Price's ''Observations on Civil Liberty and the Justice and Policy of the War with America''

*

Price's ''Observations on reversionary payments on schemes for providing annuities for widows, and for persons in old age; on the method of calculating the values of assurances on lives; and on the national debt : to which are added four essays ... also an appendix ...'', published in 1771

{{DEFAULTSORT:Price, Richard 1723 births 1791 deaths 18th-century British philosophers 18th-century English male writers 18th-century Unitarian clergy 18th-century Welsh educators 18th-century Welsh writers Anti-monarchists Burials at Bunhill Fields 18th-century English philosophers English Unitarians Enlightenment philosophers Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Fellows of the Royal Society People from Bridgend County Borough Welsh actuaries Welsh philosophers Welsh statisticians Welsh Unitarians International members of the American Philosophical Society