Richard Leveson (admiral) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Richard Leveson (c. 1570 – 2 August 1605). was an important

/ref> :*Anne Corbet, the daughter of Sir Andrew Corbet of

/ref> in concert with the Levesons, they could dictate the representation of

Leveson took to the sea in his teenage years and his career was secured by marriage in 1587 to Margaret, the daughter of

Leveson took to the sea in his teenage years and his career was secured by marriage in 1587 to Margaret, the daughter of

/ref>

accessed 23 September 2013. Leveson must have seemed an obvious choice at the time and two of the prominent county gentry took the unusual step of countersigning the return to mark their approval: Vincent Corbet, Leveson's uncle, and Francis Newport. Newport's endorsement was significant: a former MP, and three times

For most of Richard Leveson's life he was heir to great estates, and in his later years he was forced to look on helpless as they were endangered and dissipated. He lived occasionally at Lilleshall, Trentham or Wolverhampton, but was on active service for long periods. Although his personal wealth was largely derived from his maritime activities, including his naval service,

For most of Richard Leveson's life he was heir to great estates, and in his later years he was forced to look on helpless as they were endangered and dissipated. He lived occasionally at Lilleshall, Trentham or Wolverhampton, but was on active service for long periods. Although his personal wealth was largely derived from his maritime activities, including his naval service,

Richard Leveson fell ill while staying in the home of a friend, Hugh Bunnell, next to St. Clement's, Temple Bar, on 22 July 1605. Initially he complained of

Richard Leveson fell ill while staying in the home of a friend, Hugh Bunnell, next to St. Clement's, Temple Bar, on 22 July 1605. Initially he complained of

accessed 23 September 2013. As Richard Leveson lay dying, her father wrote to Robert Cecil asking for her

There are three examples of a

There are three examples of a Royal naval exhibition, 1891: the illustrated handbook and souvenir

/ref> the head of the Leveson-Gower family. Probably this painting was of the

Elizabethan

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The Roman symbol of Britannia (a female per ...

Navy officer, politician and landowner. His origins were in the landed gentry

The landed gentry, or the gentry (sometimes collectively known as the squirearchy), is a largely historical Irish and British social class of landowners who could live entirely from rental income, or at least had a country estate. It is t ...

of Shropshire

Shropshire (; abbreviated SalopAlso used officially as the name of the county from 1974–1980. The demonym for inhabitants of the county "Salopian" derives from this name.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West M ...

and Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation ''Staffs''.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England. It borders Cheshire to the north-west, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, ...

. A client and son-in-law of Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was ...

, he became Vice-Admiral

Vice admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to lieutenant general and air marshal. A vice admiral is typically senior to a rear admiral and junior to an admiral.

Australia

In the Royal Australian Navy, the rank of vic ...

under him. He served twice as MP for Shropshire

Shropshire (; abbreviated SalopAlso used officially as the name of the county from 1974–1980. The demonym for inhabitants of the county "Salopian" derives from this name.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West M ...

in the English parliament

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised th ...

. He was ruined by the burden of debt built up by his father.

Family background

Richard Leveson's parents were :* Sir Walter Leveson (1551-1602) ofLilleshall

Lilleshall is a village and civil parish in the Telford and Wrekin borough of Shropshire, England.

It lies between the towns of Telford and Newport, on the A518, in the Wrekin constituency. There is one school in the centre of the village. ...

, Shropshire

Shropshire (; abbreviated SalopAlso used officially as the name of the county from 1974–1980. The demonym for inhabitants of the county "Salopian" derives from this name.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West M ...

, son of Sir Richard Leveson (d.1560) and Mary Fitton (1529–1591). The family name is pronounced , and could be rendered in many ways in the 16th century, including Lewson, Luson and Lucen. In the late Middle Ages, the Levesons were important wool merchants and minor landowners based in the Wolverhampton

Wolverhampton ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands (county), West Midlands of England. Located around 12 miles (20 km) north of Birmingham, it forms the northwestern part of the West Midlands conurbation, with the towns of ...

area. They became major landowners in Shropshire and Staffordshire mainly through the acquisition of former church lands by Walter's grandfather, James Leveson, after the Dissolution of the Lesser Monasteries. The most important estates were at Lilleshall

Lilleshall is a village and civil parish in the Telford and Wrekin borough of Shropshire, England.

It lies between the towns of Telford and Newport, on the A518, in the Wrekin constituency. There is one school in the centre of the village. ...

, where James Leveson had bought first the Abbey and then the entire manor, and at Trentham, where James bought the lands of the dissolved priory

A priory is a monastery of men or women under religious vows that is headed by a prior or prioress. They were created by the Catholic Church. Priories may be monastic houses of monks or nuns (such as the Benedictines, the Cistercians, or t ...

. Walter was initially an enclosing

Enclosure or inclosure is a term, used in English landownership, that refers to the appropriation of "waste" or "common land", enclosing it, and by doing so depriving commoners of their traditional rights of access and usage. Agreements to enc ...

and improving landlord, raising the family's profile still further, and serving as MP for Shropshire three times.History of Parliament Online: Members 1558-1603 - LEVESON, Walter (1551-1602) - Author: J.J.C./ref> :*Anne Corbet, the daughter of Sir Andrew Corbet of

Moreton Corbet

Moreton Corbet is a village and former civil parish, now in the parish of Moreton Corbet and Lee Brockhurst, in the Shropshire district, in the ceremonial county of Shropshire, England. The village's toponym refers to the Corbet family, the ...

, who was vice-president of the powerful Council of Wales and the Marches

The Council of Wales and the Marches () or the Council of the Marches, officially the Court of the Council in the Dominion and Principality of Wales, and the Marches of the same was a regional administrative body founded in Shrewsbury.

...

. The Corbets were very important landowners in Shropshire, supplying knights of the shire

Knight of the shire () was the formal title for a member of parliament (MP) representing a county constituency in the British House of Commons, from its origins in the medieval Parliament of England until the Redistribution of Seats Act 1885 en ...

through much of the reign of Queen Elizabeth Queen Elizabeth, Queen Elisabeth or Elizabeth the Queen may refer to:

Queens regnant

* Elizabeth I (1533–1603; ), Queen of England and Ireland

* Elizabeth II (1926–2022; ), Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms

* Queen B ...

:History of Parliament Online: Constituencies 1558-1603 - Shropshire - Author: P. W. Hasler./ref> in concert with the Levesons, they could dictate the representation of

Shropshire

Shropshire (; abbreviated SalopAlso used officially as the name of the county from 1974–1980. The demonym for inhabitants of the county "Salopian" derives from this name.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West M ...

in the English parliament

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised th ...

.

The Leveson and Corbet families were the most powerful of the landed gentry

The landed gentry, or the gentry (sometimes collectively known as the squirearchy), is a largely historical Irish and British social class of landowners who could live entirely from rental income, or at least had a country estate. It is t ...

families in Shropshire, a county without a resident aristocracy. Both underwent a crisis in the late Elizabethan and Jacobean periods as a result of overspending and succession problems, coupled with unwise exposure to the vagaries of the State. In Richard Leveson's case, the problems stemmed almost entirely from his father's impulsive and irrational behaviour, stemming apparently from a serious mental illness.

Naval career

Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was ...

, who had been appointed Lord High Admiral in 1585.

In 1588 Leveson served as a volunteer on board the ''Ark Royal'' against the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (often known as Invincible Armada, or the Enterprise of England, ) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by Alonso de Guzmán, Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aristocrat without previous naval ...

, and in 1596 had a command in the expedition against Cadiz, on which occasion he was knighted. In 1597 he is said to have commanded the ''Hope'' in 'the Islands' voyage' under Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex (; 10 November 1565 – 25 February 1601) was an English nobleman and a favourite of Queen Elizabeth I. Politically ambitious, he was placed under house arrest following a poor campaign in Ireland during th ...

, though other lists describe him as commanding the ''Nonpareil''. It is possible that he moved from one ship to the other during the expedition. In 1599 he commanded the ''Lion'' in the fleet fitted out, under Lord Thomas Howard

Lord Thomas Howard (1511 – 31 October 1537) was an English courtier at the court of King Henry VIII. He is chiefly known for his marriage (later invalidated by Henry) to Lady Margaret Douglas (1515–1578), the daughter of Henry VIII's si ...

, in expectation of a Spanish attempt at invasion. In 1600, with the style of 'admiral of the narrow seas

The Admiral of the Narrow Seas also known as the Admiral for the guard of the Narrow Seas was a senior Royal Navy appointment. The post holder was chiefly responsible for the command of the English navy's Narrow Seas Squadron also known as the ...

,' he commanded a squadron sent towards the Azores to look out for the Spanish treasure-ships. Great care was taken to keep their destination secret; but the Spaniards, warned by experience, changed the route of their ships, and so escaped. In October 1601 he was appointed ''captain-general and admiral of certain of her Majesty's ships to serve against the Spaniards lately landed in Ireland.'' (Cal. State Papers, Ireland), and in the early days of December fought a battle off Castlehaven and forced his way into the harbour of Kinsale

Kinsale ( ; ) is a historic port and fishing town in County Cork, Ireland. Located approximately south of Cork (city), Cork City on the southeast coast near the Old Head of Kinsale, it sits at the mouth of the River Bandon, and has a populatio ...

, where, after a severe action, he destroyed the whole of the enemy's shipping under Pedro de Zubiaur

Pedro de Zubiaur, Zubiaurre or Çubiaurre (1540 – 3 August 1605) was a Spanish naval officer and engineer, general of the Spanish Navy, distinguished for his achievements in the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604).

Biography

Born into a seafari ...

.

Early in 1602 Leveson was appointed to command a powerful fleet of nine English and twelve Dutch ships, which were ''to infest the Spanish coast.'' The Dutch ships were, however, late in joining, and Leveson, leaving his vice-admiral Sir William Monson, to wait for them, put to sea with only five ships on 19 March 1602. Within two or three days the queen sent Monson orders to sail at once to join his admiral, for she had word that 'the silver ships were arrived at Terceira.' They had, in fact, arrived and left again; and before Monson could join him Leveson fell in with them. With his very small force he could do nothing. 'If the Hollanders,' wrote Monson, 'had kept touch, according to promise, and the queen's ships had been fitted out with care, we had made her majesty mistress of more treasure than any of her progenitors ever enjoyed.' It was not till the end of May that the two English squadrons met with each other, and on 1 June, being then off Lisbon, they had news of a large carrack and eleven galleys in Cezimbra bay. Some of the English ships had been sent home as not seaworthy; others had separated; there were only five with Leveson when, on the morning of the 3rd, he found the Spanish ships both under the command of Federico Spinola

Federico Spinola (1571–1603) was an Italian naval commander in Spanish Habsburg service during the Dutch Revolt.

Life

Spinola was born in Genoa in 1571 and studied at the University of Salamanca in preparation for an intended ecclesiastical c ...

and Álvaro de Bazán Álvaro or Álvar (, , ) is a Spanish, Galician and Portuguese male given name and surname of Germanic Visigothic origin.

The patronymic surname derived from this name is Álvarez.

Given name Artists

* Álvaro Carrillo, Afro-Mexican songwrit ...

strongly posted under the guns of the castle. At ten o'clock he stood into the bay, and after a fight which lasted till five in the evening, two of the galleys were burnt, and the rest, with the carrack

A carrack (; ; ) is a three- or four- masted ocean-going sailing ship that was developed in the 14th to 15th centuries in Europe, most notably in Portugal and Spain. Evolving from the single-masted cog, the carrack was first used for Europea ...

, ''Saõ Valentinho'' capitulated and were taken to England. The prize money from the carrack worth £3,000 was awarded by Queen Elizabeth.

In 1603, during the last sickness and after the death of the queen, Leveson commanded the fleet in the narrow seas, to prevent any attempt to disturb the peace of the country or to influence the succession being made from France or the Netherlands. This was his last service at sea. On 7 April 1604 he was appointed jointly ''Lieutenant of the Admiralty

The Lieutenant of the Admiralty is a now honorary office generally held by a senior retired Royal Navy admiral. He is the official deputy to the Vice-Admiral of the United Kingdom. He is appointed by the Sovereign on the nomination of the First ...

of England,'' and Vice-Admiral of England

Vice-Admiral of the United Kingdom is an honorary office generally held by a senior Royal Navy admiral. The title holder is the official deputy to the Lord High Admiral, an honorary (although once operational) office which was vested in the S ...

for life (ib. Dom.), and in the following year was marshal of the embassy to Spain for the conclusion of the peace. Shortly after his return he died in London.

Member of Parliament

The parliament of 1589

Richard Leveson was elected a member of the English parliament for the first time on 7 November 1588, sitting in the 1589 parliament. He was one of two members for the county ofShropshire

Shropshire (; abbreviated SalopAlso used officially as the name of the county from 1974–1980. The demonym for inhabitants of the county "Salopian" derives from this name.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West M ...

, the other being his own father, Walter. In the previous election, in October 1586, Walter had been paired with Richard Corbet, his brother-in-law, and the two families had decisive influence over the choice of MP for several decades. At the time of his election he was only 18 years old, unusual but not unique in this period. The parliament lasted only from 4 February 1589 until 29 March. Leveson was not a prominent and the journals for the 1589 Parliament mention that he asked for leave of absence.History of Parliament Online: Members 1558-1603 - LEVESON, Richard (1570-1605) - Author: J.J.C., accessed 26 September 2013/ref>

The parliament of 1604

The summoning of the first parliament ofJames I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

* James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

* James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

* James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334� ...

found Leveson at the height of his prestige. His capture of the Portuguese carrack was still fresh in the memory. At the funeral of Elizabeth I, he had acted as a knight of the canopy. On his arrival in London in May 1603, James I made Leveson a gentleman of the Privy chamber

A privy chamber was the private apartment of a royal residence in England.

The Gentlemen of the Privy Chamber were noble-born servants to the Crown who would wait and attend on the King in private, as well as during various court activities, f ...

. Later that year, he was given the task of taking Thomas Grey, 15th Baron Grey de Wilton

Thomas Grey, 15th Baron Grey de Wilton (died 1614) was an English aristocrat, soldier and conspirator. He was convicted of involvement in the Bye Plot against James I of England.

Early life

The son of Arthur Grey, 14th Baron Grey of Wilton, b ...

to Winchester

Winchester (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs N ...

for trial as a participant in the Bye Plot

The Bye Plot of 1603 was a conspiracy, by Priesthood (Catholic Church), Roman Catholic priests and Puritans aiming at toleration, tolerance for their respective denominations, to kidnap the new English king, James I of England. It is referred to ...

.

Throughout Elizabeth's reign, Shropshire had been represented by eight families, mainly based in the north of the county, of which the Levesons were one. Andrew Thrush and John P. Ferris (editors): History of Parliament Online: Constituencies 1604-1629 - Shropshire - Author: Simon Healyaccessed 23 September 2013. Leveson must have seemed an obvious choice at the time and two of the prominent county gentry took the unusual step of countersigning the return to mark their approval: Vincent Corbet, Leveson's uncle, and Francis Newport. Newport's endorsement was significant: a former MP, and three times

High Sheriff of Shropshire

This is a list of sheriffs and high sheriffs of Shropshire

The high sheriff, sheriff is the oldest secular office under the Crown. Formerly the high sheriff was the principal law enforcement officer in the county but over the centuries most of t ...

, he knew Leveson's difficulties well, as the Privy Council had sent him to arrest three of Sir Walter's servants in 1593. The second member was Robert Needham, a cousin of Leveson and Corbet whose family estates were mainly around Cranage

Cranage is a village and civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire East and the ceremonial county of Cheshire, England. According to the 2001 UK Census, the population of the civil parish was 1,131 which had risen to 1,184 by the 2011 c ...

in Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in North West England. It is bordered by Merseyside to the north-west, Greater Manchester to the north-east, Derbyshire to the east, Staffordshire to the south-east, and Shrop ...

but whose seat was Shavington Hall in Shropshire.

When the parliament assembled on 19 March 1604, Leveson was one of those deputed to administer the Oath of Supremacy

The Oath of Supremacy required any person taking public or church office in the Kingdom of England, or in its subordinate Kingdom of Ireland, to swear allegiance to the monarch as Supreme Governor of the Church. Failure to do so was to be trea ...

to the rest of the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

, He was soon nominated to two committees directly concerned with family affairs of his patron, the Earl of Nottingham. One was the committee to deal with the naturalization

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-national of a country acquires the nationality of that country after birth. The definition of naturalization by the International Organization for Migration of the ...

of Nottingham's wife. Leveson's mother-in-law had died shortly before the queen. The earl then married a Scottish woman, about fifty years his junior, Margaret Stuart, a daughter of the so-called "Bonny Earl", James Stewart, 2nd Earl of Moray

James Stewart, 2nd Lord Doune, ''jure uxoris'' 2nd Earl of Moray (c. 1565 – 7 February 1592), was a Scottish nobleman. He was murdered by George Gordon, Earl of Huntly as the culmination of a vendetta. Known as the Bonnie Earl for his good ...

. The second committee dealt with provision for Leveson's sister-in-law, Frances Howard, known as Lady Kildare, as she was the widow of Henry FitzGerald, 12th Earl of Kildare

Henry FitzGerald, 12th Earl of Kildare (1562 – 30 September 1597) was an Irish peer and soldier.

Background

Kildare was the second son of Gerald FitzGerald, 11th Earl of Kildare and Mabel Browne. cites His eldest brother died in 1580, and He ...

. Her second husband, Henry Brooke, 11th Baron Cobham

Henry Brooke, 11th Baron Cobham (22 November 1564 – 24 January 1618 (Old Style and New Style dates, Old Style)/3 February 1618 (New Style), lord of the manor, lord of the Manor of Cobham, Kent, was an English peer who was implicated in the M ...

had been condemned to death in November 1603 for his part in the Main Plot

The Main Plot was an alleged conspiracy of July 1603 by English courtiers to remove King James I from the English throne and to replace him with his cousin Lady Arbella Stuart. The plot was supposedly led by Lord Cobham and funded by the Spani ...

to install Lady Arbella Stuart

Lady Arbella Stuart (also Arabella, or Stewart; 1575 – 25 September 1615) was an English noblewoman who was considered a possible successor to Queen Elizabeth I of England. During the reign of King James VI and I (her first cousin), she marrie ...

on the throne. He was not executed but held in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

until his health broke down in 1617. As proposed by the committee, Parliament granted Cobham's lands to Lady Kildare.

Parliament also drew on Leveson's professional expertise. He was named to a committee dealing with the relief of soldiers and sailors who had served in the Irish war and to another on a bill to prohibit the export of iron artillery

Artillery consists of ranged weapons that launch Ammunition, munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, and l ...

. The latter was one of a series of measures proposed by the highly experienced MP Robert Wroth, who had sought to set the agenda for the parliament by bringing forward a list of seven "grievances" or reform proposals around which he hoped to focus debate. The most important was a proposal to sweep away the abuses of the wardship

In law, a ward is a minor or incapacitated adult placed under the protection of a legal guardian or government entity, such as a court. Such a person may be referenced as a "ward of the court".

Overview

The wardship jurisdiction is an ancient ju ...

system, but he also wanted reform of the Exchequer

In the Civil Service (United Kingdom), civil service of the United Kingdom, His Majesty's Exchequer, or just the Exchequer, is the accounting process of central government and the government's ''Transaction account, current account'' (i.e., mon ...

and elements of religious and social reform. Leveson was nominated to a committee to look at the whole programme proposed by Wroth, as well as to some of the committees on specific proposals. However, Wroth was a puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

, the last of the Marian exiles

The Marian exiles were English Protestants who fled to continental Europe during the 1553–1558 reign of the Catholic monarchs Queen Mary I and King Philip.Christina Hallowell Garrett (1938) ''Marian Exiles: A Study in the Origins of Elizabet ...

to serve in the House of Commons. His approach was not universally popular and there were powerful interests opposed to him in the Court and in the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

, as well as cracks in his relationship with his patron, Robert Cecil. In the end, none of Wroth's program was carried.

Leveson was nominated to a committee to consider Union between the kingdoms of Scotland and England; another proposal that came to nothing at this stage. On 2 May there was a complaint the House's proceedings were not accurately reported to the king by those who had access to him. As a gentleman of the privy chamber, Leveson felt impelled to reply and stood up to do so. However, the puritan Sir Francis Hastings

Sir Francis Hastings (c. 1546–1610) was an English Puritan politician.

Hastings was a skilful parliamentarian, and excellent committee man, and schooled in the importance of religion in political discourse. A published author, highly ...

rose at the same time to press home the complaint. The House ruled in favour of Hastings and Leveson was forced to sit down. However, on 5 June he did address the House on a bill for the continuance and repeal of expiring statutes.

The Parliament was not dissolved and was to last until 1611. However, Leveson died before the next session was held in 1606. He was replaced as MP after a by-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, or a bypoll in India, is an election used to fill an office that has become vacant between general elections.

A vacancy may arise as a result of an incumben ...

by the immensely wealthy Shrewsbury lawyer and businessman Sir Roger Owen.

Finances

privateering

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since Piracy, robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sover ...

and trade, he was appointed to some of the offices appropriate to the Staffordshire and Shropshire landed gentry

The landed gentry, or the gentry (sometimes collectively known as the squirearchy), is a largely historical Irish and British social class of landowners who could live entirely from rental income, or at least had a country estate. It is t ...

. By 1594, at latest, he was a justice of the peace in both counties. In 1596 he was made Custos Rotulorum of Shropshire, the senior position in the civil administration of the county, and an important honour.

It was his father, Sir Walter Leveson, who placed the Leveson patrimony in great danger, as he was accused of piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and valuable goods, or taking hostages. Those who conduct acts of piracy are call ...

in 1587, and later of sorcery

Sorcery commonly refers to:

* Magic (supernatural), the application of beliefs, rituals or actions employed to manipulate natural or supernatural beings and forces

** Goetia, ''Goetia'', magic involving the evocation of spirits

** Witchcraft, the ...

. Initially he took rational measures to increase his income but gradually declined mentally. From 1598 Sir Walter was incarcerated in the Fleet Prison

Fleet Prison was a notorious London prison by the side of the River Fleet. The prison was built in 1197, was rebuilt several times, and was in use until 1844. It was demolished in 1846.

History

The prison was built in 1197 off what is now ...

. Although his great estates were still largely intact, they were endangered by the massive debts he incurred as a result of the compensation and fines he was ordered to pay. The debt grew from about £10,500 in 1591 to £12,000 a decade later. By this stage, Richard's mother, Anne Corbet, had died and Walter had married Susan Vernon, a cousin of Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex (; 10 November 1565 – 25 February 1601) was an English nobleman and a favourite of Queen Elizabeth I. Politically ambitious, he was placed under house arrest following a poor campaign in Ireland during th ...

. Walter wrote to Essex asking that he or one of the Vernons be appointed trustee of the family estates. However, Walter was in the grip of a persecutory delusion

A persecutory delusion is a type of delusional condition in which the affected person believes that harm is going to occur to oneself by a persecutor, despite a clear lack of evidence. The person may believe that they are being targeted by an ...

. He claimed that he was the victim of a plot connected to jealousy of his second marriage. When Richard made suggestions, his father accused him of plotting with a man with the surname Ethell to ruin him. Convinced that the death of his daughter-in-law would somehow solve his problems, he grew poisonous plants at Lilleshall and made an attempt on her life.

Essex referred the Leveson case to Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton

Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton (25 February 154015 June 1614) was an English aristocrat and courtier. He was suspected throughout his life of being Roman Catholic, and went through periods of royal disfavour, in which his reputation ...

, who engineered an agreement in June 1601. Richard Leveson was to take on his father's assets and liabilities in return for an annuity of £580, a generous allowance, as Sir John Leveson later valued the estates at only £600 a year. However, Sir Walter had to guarantee that there were no hidden liabilities. The agreement was never implicated because Richard suspected Sir Walter was plotting to transfer assets to his sister, Mary Curzon - a suspicion confirmed by Susan Vernon. He also foiled an attempt to transfer assets to his illegitimate half-sister, Penelope, by intercepting one of his father's servants. Writing to Robert Cecil in December 1601, Leveson pointed out that

:"the miserable wrecks of my father's torn estate are well-known. His want of care, and my want of credit with him to take up loose ends before they ravelled into extremities, are the cause that my lands are now by forfeitures brought into the hands of strangers....What land soever I may discover in the Queen's service upon a foreign coast, I am never likely to see any profit of my own lands at home"

Not until 1602 did Leveson inherit the estates on the death of his father, imprisoned to the last in the Fleet

Fleet may refer to:

Vehicles

* Fishing fleet

*Naval fleet

* Fleet vehicles, a pool of motor vehicles

* Fleet Aircraft, the aircraft manufacturing company

Places

Canada

* Fleet, Alberta, Canada, a hamlet

England

* The Fleet Lagoon, at Chesil Be ...

. This did not end his problems, but only added to them, as he was now responsible for his father's vast debts. In 1603 he and his step-mother faced legal action from Sir Julius Caesar

Sir Julius Caesar (1557/155818 April 1636) was an English lawyer, judge and politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1589 and 1622. He was also known as Julius Adelmare.

Early life and education

Caesar was born near T ...

, who was trying to recover £800. Caesar was a dangerous opponent as he was a powerful and wealthy judge and government minister. The capture of the Portuguese carrack

A carrack (; ; ) is a three- or four- masted ocean-going sailing ship that was developed in the 14th to 15th centuries in Europe, most notably in Portugal and Spain. Evolving from the single-masted cog, the carrack was first used for Europea ...

gave considerable relief, but the £3000 Leveson was awarded was far from sufficient to clear his debts. Worse, still it was later to create further financial difficulties.

By this time the wreck of Leveson's finances was complete, and he was forced to put the estates into the hands of trustees, headed by his first cousin, Sir John Leveson of Halling, Kent

Halling is a village on the North Downs in the northern part of Kent, England. Consisting of Lower Halling, Upper Halling and North Halling, it is scattered over some along the River Medway parallel to the Pilgrims' Way which runs through Kent ...

. Sir John Leveson made progress, but little was achieved before the death of Sir Richard Leveson, less than three years later.

Rumours then began to circulate that Sir Richard had actually been fabulously wealthy as a result of his seafaring profits. In 1607 Leveson's cabin steward, Walter Grey, claimed that Leveson had concealed and stolen vast quantities of calico

Calico (; in British usage since 1505) is a heavy plain-woven textile made from unbleached, and often not fully processed, cotton. It may also contain unseparated husk parts. The fabric is far coarser than muslin, but less coarse and thick than ...

and pearl

A pearl is a hard, glistening object produced within the soft tissue (specifically the mantle (mollusc), mantle) of a living Exoskeleton, shelled mollusk or another animal, such as fossil conulariids. Just like the shell of a mollusk, a pear ...

s from the carrack - goods which did not form part of his share but rightly belonged to the queen. He alleged that Leveson had a vast cache of pearls in a barn at Sheriffhales

Sheriffhales is a dispersed settlement, scattered village in Shropshire, England, north-east of Telford, north of Shifnal and south of Newport, Shropshire, Newport. The name derives from Halh (Anglican) and scīr-rēfa (Old English) which i ...

, near his Lilleshall estate. Altogether, it was calculated, Leveson had defrauded the queen of goods to the value of £40,000. This was an overwhelming problem for Sir John Leveson, who had no hope of extracting such a vast sum from the estates. He investigated further and was able to undermine trust in Grey's story by bringing witnesses to testify that he had ended on bad terms with Leveson. He then uncovered further evidence that Grey had been given a deed promising £450 out of any fine connected with the carrack affair. The deed had been drawn up by Thomas Sackville, 1st Earl of Dorset

Thomas Sackville, 1st Earl of Dorset (153619 April 1608) was an English statesman, poet, and dramatist. He was the son of Richard Sackville, a cousin to Anne Boleyn. He was a Member of Parliament and Lord High Treasurer.

Biography Early lif ...

, the Lord High Treasurer

The Lord High Treasurer was an English government position and has been a British government position since the Acts of Union of 1707. A holder of the post would be the third-highest-ranked Great Officer of State in England, below the Lord H ...

and a Scottish courtier called Sir James Creighton. Dorset had an interest in exerting leverage on the Leveson estate, as his grandson Edward Sackville was engaged to marry Richard Leveson's cousin, Mary Curzon: the daughter of the Mary Curzon who had earlier conspired with Sir Walter, and heiress of Sir George Curzon of Croxall Hall

Croxall Hall is a restored and extended 16th century manor house situated in the small village of Croxall, Staffordshire (close to the southeastern border with Derbyshire and historically part of it). It is a Grade II* listed building.

The man ...

, Derbyshire. Discovery of the deed meant that Sir John was able to discredit Grey, who had a financial interest in perjuring himself, but doubts lingered and he was up against the most powerful faction in government. He was still faced by a large fine, albeit reduced to £5000.

After Sir John's death in 1615, his widow, Christian, took up the challenge of stabilising the Leveson family finances. After numerous further setbacks, she paid off the debts in 1623. This allowed the estates to pass later that year to Sir Richard Leveson's designated heir, the son of Sir John and Christian, and another Sir Richard Leveson.

Death and succession

fever

Fever or pyrexia in humans is a symptom of an anti-infection defense mechanism that appears with Human body temperature, body temperature exceeding the normal range caused by an increase in the body's temperature Human body temperature#Fever, s ...

. This was complicated by constant diarrhoea

Diarrhea (American English), also spelled diarrhoea or diarrhœa (British English), is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements in a day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration d ...

and he died on 2 August 1605. He was buried on 2 September in St Peter's Collegiate Church

St Peter's Collegiate Church is located in central Wolverhampton, England. For many centuries it was a Chapel Royal, chapel royal and from 1480 a royal peculiar, independent of the Diocese of Lichfield and even the Province of Canterbury. The ...

, Wolverhampton

Wolverhampton ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands (county), West Midlands of England. Located around 12 miles (20 km) north of Birmingham, it forms the northwestern part of the West Midlands conurbation, with the towns of ...

.

Leveson had made his will on 17 March 1605. In it he chose to characterise life in terms of the travails of landholding:

:"calling to mind the uncertainty of all earthly things, and that we hold and enjoy ourselves together with all our temporal blessings but as tenants at will to our good God that gave them." Always alive to the possibility of death on active service, on 23 March he had also drawn up a deed conveying all his property to a group of trustee

Trustee (or the holding of a trusteeship) is a legal term which, in its broadest sense, refers to anyone in a position of trust and so can refer to any individual who holds property, authority, or a position of trust or responsibility for the ...

s headed by his friend and distant relative, Sir Robert Harley

''Sir'' is a formal honorific address in English for men, derived from Sire in the High Middle Ages. Both are derived from the old French "" (Lord), brought to England by the French-speaking Normans, and which now exist in French only as part ...

, who were responsible for raising £10,000 to settle his debts. A second deed on the same date named his heirs.

As he had no male issue, he left the bulk of his property to his godson and third cousin, Richard Leveson (1598–1661), son of Sir John Leveson (d.1615), who had once shared in his privateering

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since Piracy, robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sover ...

activities. However, also named as heir was Leveson's illegitimate daughter, Anne Fitton, who he hoped would marry the young Richard Leveson. Richard Leveson went on to become a Member of Parliament and a prominent royalist soldier in the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

. However, he married Katherine Dudley, leaving his benefactor's plan in tatters. Leveson's will also awarded £1000 to Penelope, his illegitimate half-sister, whom he had previously managed to exclude from inheriting from his father's property.

Marriage and family

At the age of 17, Leveson married by licence, dated 13 December 1587, Margaret, daughter of theCharles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was ...

and Catherine Carey

Catherine Carey, after her marriage Catherine Knollys and later known as both Lady Knollys and Dame Catherine Knollys, ( – 15 January 1569), was chief Lady of the Bedchamber to Queen Elizabeth I, who was her first cousin.

Biography

Cather ...

. The couple had one child, who died while young. Margaret later suffered increasingly from a mental disorder

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness, a mental health condition, or a psychiatric disability, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. A mental disorder is ...

, allegedly because of the loss of her child, although she also suffered at least one attempt on her life by father-in-law. Andrew Thrush and John P. Ferris (editors): History of Parliament Online: Members 1604-1629 - LEVESON, Sir Richard (1570-1605), of Lilleshall Lodge, Salop; Trentham and Parton, Staffs. and Bethnal Green, Mdx. - Author: Andrew Thrushaccessed 23 September 2013. As Richard Leveson lay dying, her father wrote to Robert Cecil asking for her

wardship

In law, a ward is a minor or incapacitated adult placed under the protection of a legal guardian or government entity, such as a court. Such a person may be referenced as a "ward of the court".

Overview

The wardship jurisdiction is an ancient ju ...

.

:''"I am very sorry to have such a subject to write of, which is that my son Lewson is most dangerously sick and to be much doubted of his recovery. For he is the weakest man that ever I saw and is still in the extremity of the burning fever and now in a very great looseness. There is little hope of him. And as you know my poor daughter, his wife, in what case of weakness she is; and I know how ready men are to seek after such things at his Majesty's hands, and because I know it chiefly concerns your offer, although I know her state is not so weak as by law she can be found so imperfect, yet I would be loth it should come in question being my daughter. Therefore in your love to me prevent it and let me have the custody of my own daughter, that her imperfection which it has pleased God to lay on her may not be so known to my great grief in the end of my years. It is well known what she was till God called her only child away, which her nature and weak spirit could not resist; and with all that, which you know of, her bad father-in-law's dealing with her, whom God forgive for it. If God call him, the King shall lose a worthy servant and myself one that I accounted rather my natural son than a son-in-law. Good my lord, you are a father and therefore you best know my case in this.—Chelse, 2 August."''

The wardship was instead granted to her brother, William Howard, 3rd Baron Howard of Effingham

William Howard, 3rd Baron Howard of Effingham (27 December 1577 – 28 November 1615) was an English nobleman, the eldest son of Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham (who as Lord Howard of Effingham famously led the English fleet against the S ...

. Margaret's wardship finally passed to her father after Effingham's death in 1615.

In the final years of his life, Leveson set up home at Perton

Perton is a large estate and civil parish located in the South Staffordshire District, Staffordshire, England. It lies 3 miles to the south of Codsall and 4 miles west of Wolverhampton, where part of the estate is conjoined to the estate ...

, near Wolverhampton, with the noted courtesan Mary Fitton

Mary Fitton (or Fytton) (baptised 25 June 1578 – 1647) was an Elizabethan gentlewoman who became a maid of honour to Queen Elizabeth. She is noted for her scandalous affairs with William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke, Vice-Admiral Sir Richar ...

, the daughter of Sir Edward Fitton

Sir Edward Fitton the Elder (31 March 1527 – 3 July 1579), was Lord President of Connaught and Thomond and Vice-Treasurer of Ireland.

Biography

Fitton was the eldest son of Sir Edward Fitton of Gawsworth (d. 1548) and Mary Harbottle, daughter ...

of Gawsworth

Gawsworth is a civil parish and village in the unitary authority of Cheshire East and the ceremonial county of Cheshire, England. The population of the civil parish at the 2011 census was 1,705. It is one of the eight ancient parishes of Mac ...

, Cheshire (1548-1606) and Alice Holcroft (d.1627). They were second cousins

A cousin is a relative who is the child of a parent's sibling; this is more specifically referred to as a first cousin. A parent of a first cousin is an aunt or uncle.

More generally, in the kinship system used in the English-speaking world, c ...

: Leveson's paternal grandmother was also called Mary Fitton. They had a daughter, Anne, for whom Leveson sought to provide in his will. Mary Fitton continued to reside at Perton after Leveson's death, marrying another naval officer, Captain William Polewhele. The affair with Mary Fitton appears to have had no effect on Leveson's personal or political relations with Lord Howard, who continued to write of him as a son.

In January 1605 Leveson talked to one of the royal physicians, and had courtiers praise Mary Fitton's sister Anne Newdigate to the pregnant Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I. She was List of Scottish royal consorts, Queen of Scotland from their marriage on 20 August 1589 and List of English royal consorts, Queen of Engl ...

in an unsuccessful attempt to get her made nurse to Princess Mary.

Portraiture

There are three examples of a

There are three examples of a portrait miniature

A portrait miniature is a miniature portrait painting from Renaissance art, usually executed in gouache, Watercolor painting, watercolor, or Vitreous enamel, enamel. Portrait miniatures developed out of the techniques of the miniatures in illumin ...

of Leveson by the Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

artist Isaac Oliver

Isaac Oliver ( – bur. 2 October 1617) or Olivier was an English portrait miniature painter.

Life and work

Born in Rouen around 1565, he moved to London in 1568 with his Huguenot parents Peter and Epiphany Oliver to escape the Wars of Reli ...

, apparently all painted personally by Oliver towards 1600, one of which is held by the Wallace Collection

The Wallace Collection is a museum in London occupying Hertford House in Manchester Square, the former townhouse (Great Britain), townhouse of the Seymour family, Marquess of Hertford, Marquesses of Hertford. It is named after Sir Richard Wall ...

. They are regarded as typical of the style of Oliver, who studied under Nicholas Hilliard

Nicholas Hilliard ( – before 7 January 1619) was an English goldsmith and limner best known for his portrait miniatures of members of the courts of Elizabeth I and James I of England. He mostly painted small oval miniatures, but also some l ...

, the leading English miniaturist of the period. Oliver went on to become the official miniaturist to Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I. She was List of Scottish royal consorts, Queen of Scotland from their marriage on 20 August 1589 and List of English royal consorts, Queen of Engl ...

.

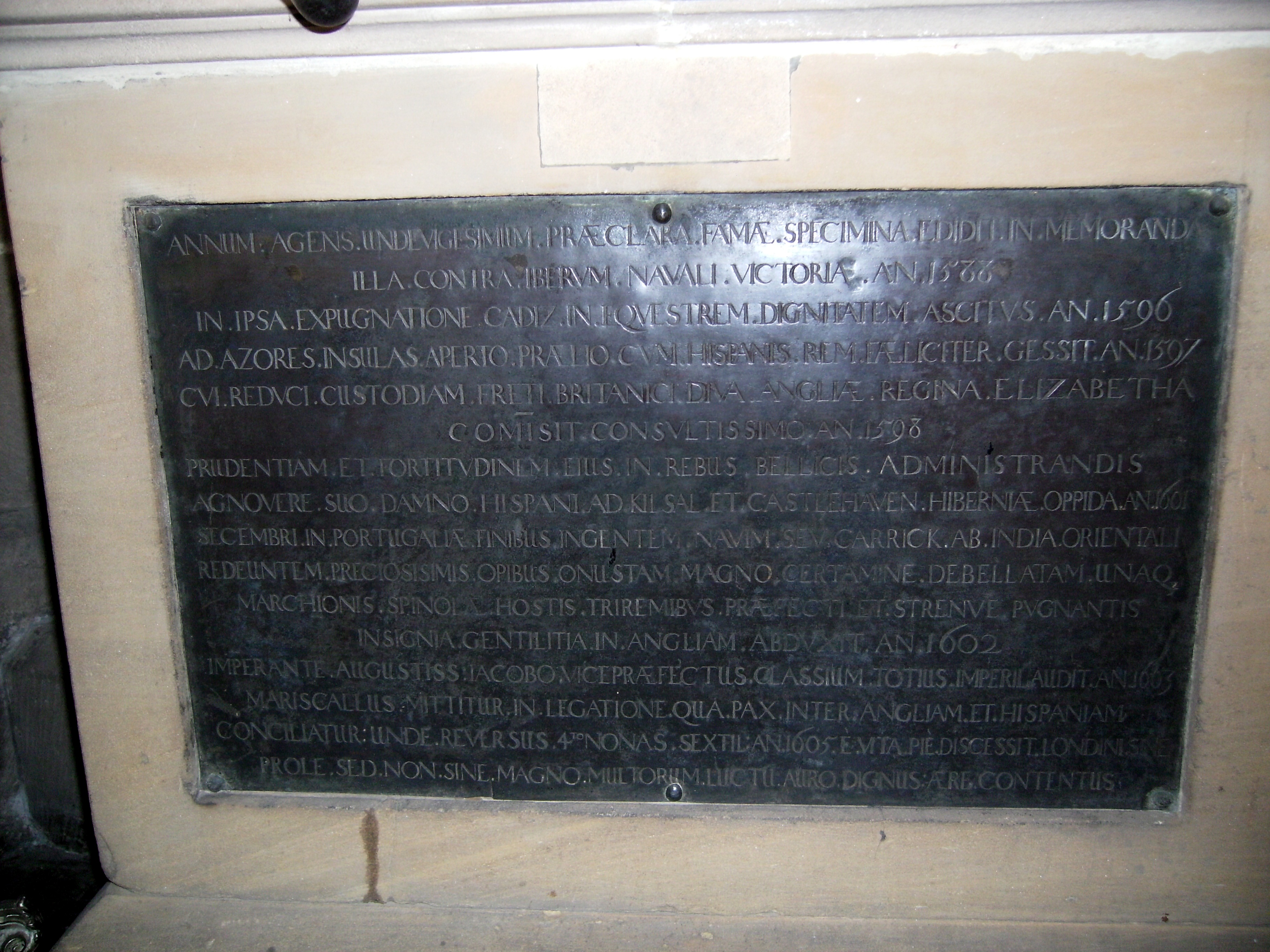

St Peter's Collegiate Church

St Peter's Collegiate Church is located in central Wolverhampton, England. For many centuries it was a Chapel Royal, chapel royal and from 1480 a royal peculiar, independent of the Diocese of Lichfield and even the Province of Canterbury. The ...

has a striking statue and monument to Leveson. The bronze statue is by Hubert Le Sueur

Hubert Le Sueur (; – 1658) was a French people, French sculpture, sculptor with the contemporaneous reputation of having trained in Giambologna's Florence, Florentine workshop. He assisted Giambologna's foreman, Pietro Tacca, in Paris, in finis ...

, another Huguenot artist who made a career in England. It originally formed part of a family group in the chancel. After damage during the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

, it was detached and reassembled in the lady chapel

A Lady chapel or lady chapel is a traditional British English, British term for a chapel dedicated to Mary, mother of Jesus, particularly those inside a cathedral or other large church (building), church. The chapels are also known as a Mary chape ...

. A bronze plaque now recites Leveson's main naval achievements, while another gives details of his family connections. Le Sueur went on to work for Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

, producing a well-known equestrian statue

An equestrian statue is a statue of a rider mounted on a horse, from the Latin ''eques'', meaning 'knight', deriving from ''equus'', meaning 'horse'. A statue of a riderless horse is strictly an equine statue. A full-sized equestrian statue is a ...

of him now at Charing Cross

Charing Cross ( ) is a junction in Westminster, London, England, where six routes meet. Since the early 19th century, Charing Cross has been the notional "centre of London" and became the point from which distances from London are measured. ...

.

A portrait of Sir Richard Leveson, said to be by Anthony van Dyck

Sir Anthony van Dyck (; ; 22 March 1599 – 9 December 1641) was a Flemish Baroque painting, Flemish Baroque artist who became the leading court painter in England after success in the Spanish Netherlands and Italy.

The seventh child of ...

, belongs to the Duke of Sutherland,/ref> the head of the Leveson-Gower family. Probably this painting was of the

Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gove ...

Member of Parliament, Sir Richard Leveson. This later Sir Richard was the uncle of Lady Christian (Leveson) Temple who had married the Duke of Buckingham and Chandos's ancestor, Sir Peter Temple

Peter Temple (10 March 1946 – 8 March 2018) was an Australian crime fiction writer, mainly known for his ''Jack Irish'' novel series. He won several awards for his writing, including the Gold Dagger in 2007, the first for an Australian. He w ...

. This portrait was purchased for £65 02s 00p from the sale of the possessions of the Dukes of Buckingham and Chandos held at Stowe House, Buckinghamshire in 1848. It was described in the sale catalogue as by Van Dyck (whereas other paintings are described as 'after Van Dyck' or a 'copy of Van Dyck'). The catalogue records that Sir Richard is shown 'in a black dress, with a frill'and that the painting was 'bought 'after a very active competition.'Henry Rumsey Forster, The Stowe Catalogue Priced and Annotated 1848, London, David Bogue, Fleet Street, p.178, Item 318

References

*External links

* http://www.nearestplacetoheaven.co.uk/Ownership.html {{DEFAULTSORT:Leveson, Richard 1570s births 1605 deaths Richard Leveson (1570-1605), Vice-Admiral, MP 16th-century Royal Navy personnel 17th-century Royal Navy personnel English MPs 1589 English MPs 1604–1611 English admirals English people of the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604)