Rhinesuchid on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Rhinesuchidae is a

Like most ancient amphibians, rhinesuchids had a pair of indentations at the rear edge of the skull known as

Like most ancient amphibians, rhinesuchids had a pair of indentations at the rear edge of the skull known as

Despite this support for an aquatic lifestyle, other pieces of evidence show that rhinesuchids were capable of some terrestrial movement. Although rhinesuchids did not possess any adaptations for digging, the poorly ossified juvenile specimen of ''Broomistega'' was found in a flooded burrow which was also inhabited by a ''

Despite this support for an aquatic lifestyle, other pieces of evidence show that rhinesuchids were capable of some terrestrial movement. Although rhinesuchids did not possess any adaptations for digging, the poorly ossified juvenile specimen of ''Broomistega'' was found in a flooded burrow which was also inhabited by a ''

Bystrow's paradox was finally resolved by a 2010 study, which found that grooved ceratobrachnial structures (components of the branchial arches) are correlated with internal gills. Ancient tetrapods which preserved grooved ceratobranchials, such as the dvinosaur ''

Bystrow's paradox was finally resolved by a 2010 study, which found that grooved ceratobrachnial structures (components of the branchial arches) are correlated with internal gills. Ancient tetrapods which preserved grooved ceratobranchials, such as the dvinosaur ''

The arrival of

The arrival of

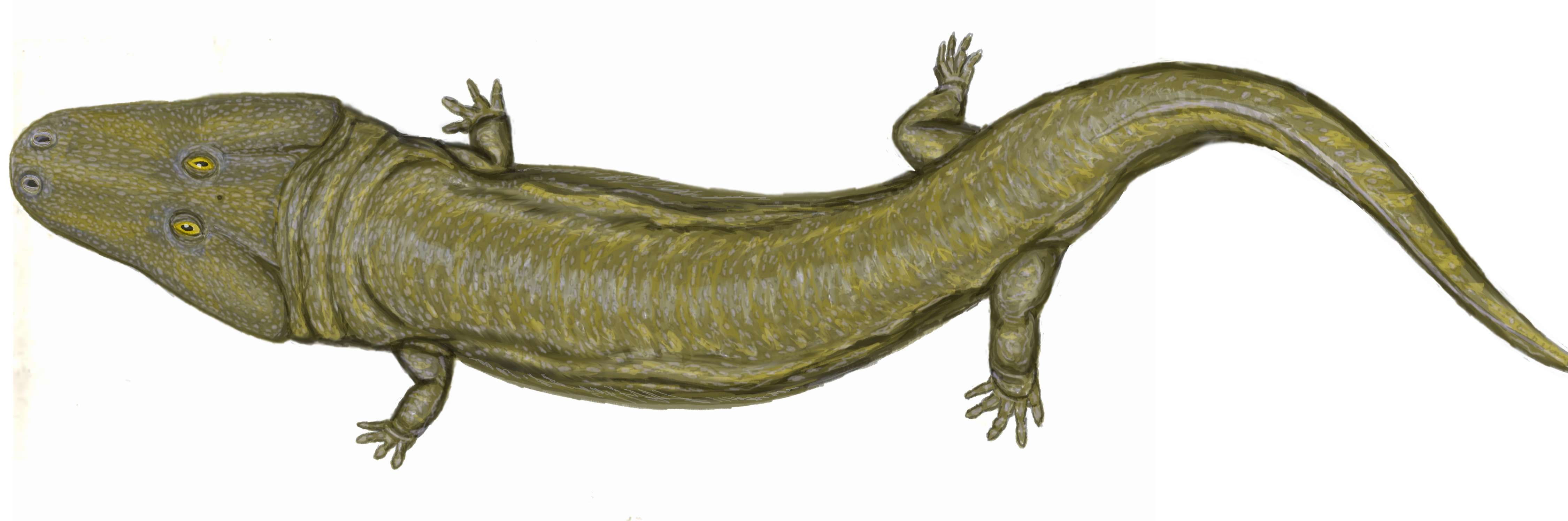

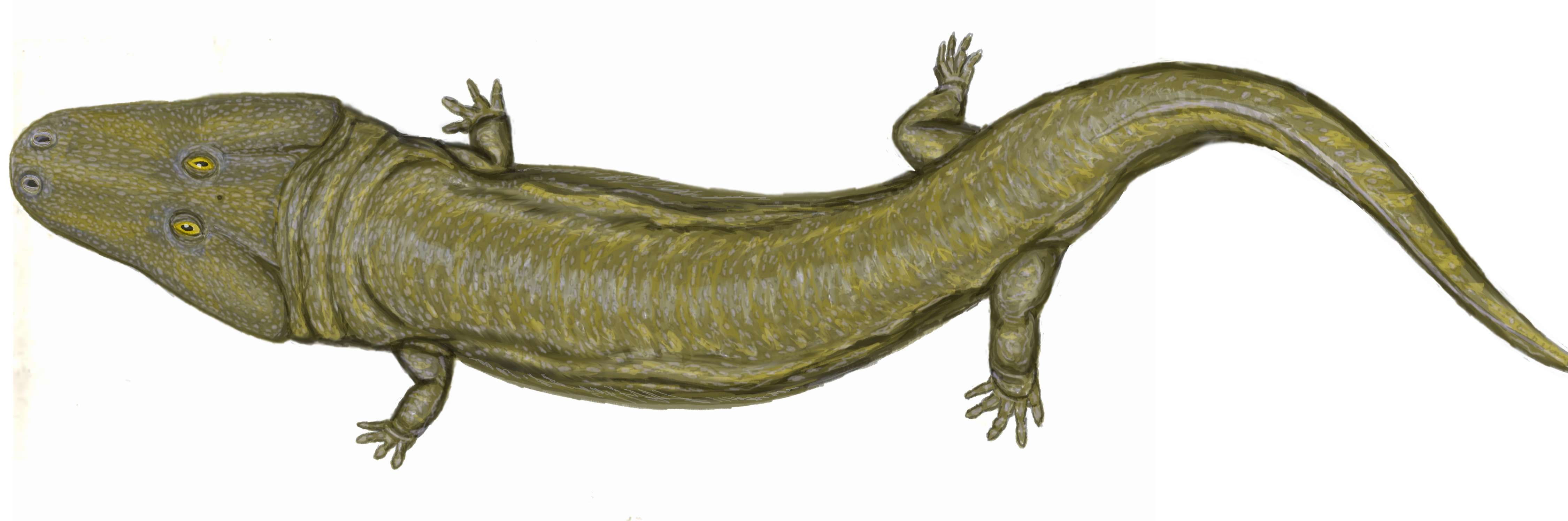

Rhinesuchus1DB.jpg, ''

family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

of tetrapods

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four- limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetrapoda (). Tetrapods include all extant and extinct amphibians and amniotes, with the lat ...

that lived primarily in the Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years, from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.902 Mya. It is the s ...

period. They belonged to the broad group Temnospondyli

Temnospondyli (from Greek τέμνειν, ''temnein'' 'to cut' and σπόνδυλος, ''spondylos'' 'vertebra') or temnospondyls is a diverse ancient order of small to giant tetrapods—often considered primitive amphibians—that flourished ...

, a successful and diverse collection of semiaquatic tetrapods which modern amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

s are probably descended from. Rhinesuchids can be differentiated from other temnospondyls by details of their skulls, most notably the interior structure of their otic notch

Otic notches are invaginations in the posterior margin of the skull roof, one behind each orbit. Otic notches are one of the features lost in the evolution of amniotes from their tetrapod ancestors.

The notches have been interpreted as part of an ...

es at the back of the skull. They were among the earliest-diverging members of the Stereospondyli

The Stereospondyli are a group of extinct temnospondyl amphibians that existed primarily during the Mesozoic period. They are known from all seven continents and were common components of many Triassic ecosystems, likely filling a similar ecologi ...

, a subgroup of temnospondyls with flat heads and aquatic habits. Although more advanced stereospondyls evolved to reach worldwide distribution in the Triassic period

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is the ...

, rhinesuchids primarily lived in the high-latitude environments of Gondwana

Gondwana ( ; ) was a large landmass, sometimes referred to as a supercontinent. The remnants of Gondwana make up around two-thirds of today's continental area, including South America, Africa, Antarctica, Australia (continent), Australia, Zea ...

(what is now South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

and Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

) during the Guadalupian

The Guadalupian is the second and middle Series (stratigraphy), series/Epoch (geology), epoch of the Permian. The Guadalupian was preceded by the Cisuralian and followed by the Lopingian. It is named after the Guadalupe Mountains of New Mexico an ...

and Lopingian

The Lopingian is the uppermost series/last epoch of the Permian. It is the last epoch of the Paleozoic. The Lopingian was preceded by the Guadalupian and followed by the Early Triassic.

The Lopingian is often synonymous with the informal te ...

epochs of the Permian. The taxonomy

image:Hierarchical clustering diagram.png, 280px, Generalized scheme of taxonomy

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme o ...

of this family has been convoluted, with more than twenty species having been named in the past; a 2017 review recognized only eight of them (distributed among seven genera) to be valid. While several purported members of this group have been reported to have lived in the Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

period, most are either dubious or do not belong to the group. However, at least one valid genus of rhinesuchid is known from the early Triassic, a small member known as ''Broomistega

''Broomistega'' is an extinct genus of temnospondyl in the family Rhinesuchidae. It is known from one species, ''Broomistega putterilli'', which was renamed in 2000 from ''Lydekkerina putterilli'' Broom 1930. Fossils are known from the Early Tri ...

''. The most recent formal definition of Rhinesuchidae, advocated by Mariscano ''et al''. (2017) is that of a stem-based clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

containing all taxa more closely related to ''Rhinesuchus whaitsi

''Rhinesuchus'' (meaning "rasp crocodile" for the ridged surface texture on its skull bones) is a large temnospondyl. Remains of the genus are known from the Permian of the South African Karoo Basin's ''Tapinocephalus'' and ''Cistecephalus'' as ...

'' than to '' Lydekkerina huxleyi'' or ''Peltobatrachus pustulatus

''Peltobatrachus'' (from Greek ''pelte'', meaning shield and batrakhos, meaning frog) is an extinct genus of temnospondyl amphibian from the late Permian period of Tanzania. The sole species, ''Peltobatrachus pustulatus'', is also the sole member ...

.'' A similar alternate definition is that Rhinesuchidae is a stem-based clade containing all taxa more closely related to '' Uranocentrodon senekalensis'' than to ''Lydekkerina huxleyi'', '' Trematosaurus brauni'', or '' Mastodonsaurus giganteus''.

Description

Rhinesuchids generally had a conventional body type for tetrapods, with four limbs and a moderately long tail. In addition, their bodies were also somewhat elongated and their limbs were small and weak but still rather well-developed. Some were very large, up to 3 meters (10 feet) in length. Like most stereospondyls, their skulls were flattened and triangular, with upward-pointing eyes. Most rhinesuchids had relatively short snouts, although the snout of ''Australerpeton

''Australerpeton'' is an extinct genus of stereospondylomorph temnospondyl currently believed to belong to the family Rhinesuchidae. When first named in 1998, the genus was placed within the new family Australerpetontidae. However, studies publ ...

'' was very long and thin. The only other giant long-snouted Permian amphibians were members of the family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

Archegosauridae

Archegosauridae is a family of relatively large and long snouted temnospondyls that lived in the Permian period. They were fully aquatic animals, and were metabolically and physiologically more similar to fish than modern amphibians.Florian Witzm ...

, such as ''Prionosuchus

''Prionosuchus'' is an extinct genus of large temnospondyl. A single species ''P. plummeri'', is recognized from the Early Permian (some time between 299 and 272 million years ago). Its fossils have been found in what is now northeastern Brazil.

...

'' and '' Konzhukovia''.

Otic notch

Like most ancient amphibians, rhinesuchids had a pair of indentations at the rear edge of the skull known as

Like most ancient amphibians, rhinesuchids had a pair of indentations at the rear edge of the skull known as otic notch

Otic notches are invaginations in the posterior margin of the skull roof, one behind each orbit. Otic notches are one of the features lost in the evolution of amniotes from their tetrapod ancestors.

The notches have been interpreted as part of an ...

es. While sometimes considered to have housed hearing organs such as a tympanum (eardrum), these notches are more likely to have held spiracles, fleshy holes used for breathing. Rhinesuchids can be characterized by a unique system of ridges and grooves within the inner cavity of each otic notch. The walls of the otic notch cavity (sometimes referred to as a tympanic cavity) are mainly made up of the ascending branch of the pterygoid bones. Nevertheless, the inside edge of each cavity is formed by a tabular bone The tabular bones are a pair of triangular flat bones along the rear edge of the skull which form pointed structures known as tabular horns in primitive Teleostomi.

References

Fish anatomy

Amphibian anatomy

{{vertebrate-anatomy-stub ...

. The tabular bones are a pair of triangular bones along the rear edge of the skull which form pointed structures known as tabular horns. The upper part of the outer wall of the cavity is also formed partly from the squamosal

The squamosal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians, and birds. In fishes, it is also called the pterotic bone.

In most tetrapods, the squamosal and quadratojugal bones form the cheek series of the skull. The bone forms an ancestra ...

bones, which mostly occupy the flat upper face of the skull. The portion of the squamosal which forms the cavity wall is separated by the portion outside of the cavity by a pronounced boundary known as a falciform crest.

The outer wall of the cavity has a long and pronounced groove, known as a stapedial groove, which extends lengthwise along the wall. The lower edge of the groove is formed by a ridge/crest known as an oblique ridge, although it has also been called a ''crista obliqua'', otic flange, or simply an oblique crest. The upper edge of the stapedial groove is formed by another ridge/crest bordering the squamosal bone, which Eltink ''et al.'' (2016) named the 'dorsal pterygoid crest'. However, Mariscano ''et al.'' (2017) preferred to use the name "''lamella''" for this structure so that it would not be confused with a different ridge present in lydekkerinids, which is sometimes termed an 'oblique crest of the pterygoid', but more commonly called a 'tympanic crest'. Confusingly enough, many rhinesuchids are also known to possess a tympanic crest. This ridge was positioned further back than the other ridges (near the intersection of the pterygoid, quadrate, and squamosal bones) and extends down along the rear face of the cheek. The inner edge of the outer wall of the cavity was formed by a ledge which most studies simply label 'membrane'. This convention exists as a result of the old and likely incorrect hypothesis that otic notches housed eardrums. Under this hypothesis, the inner ledge may have attached to a membrane stretching along the inner cavity of the ear.

This combination of otic cavity grooves and ridges is unique to rhinesuchids. The ''lamella'' and stapedial groove are unknown in any other groups, although they are present in practically every rhinesuchid (except ''Broomistega'', which lacks a ''lamella''). The tympanic crest is present in most rhinesuchids but absent in a few, and it is additionally present in lydekkerinids. The oblique ridge/crest and falciform crest are present in most other stereospondyls (although the former is less well-developed), while the 'membrane' ledge is present in practically every stereospondylomorph.

Palate and braincase

Various bones and openings comprised thepalate

The palate () is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity.

A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly sep ...

(roof of the mouth) in rhinesuchids, as in other amphibians. At the tip of the palate lied the vomer

The vomer (; ) is one of the unpaired facial bones of the skull. It is located in the midsagittal line, and articulates with the sphenoid, the ethmoid, the left and right palatine bones, and the left and right maxillary bones. The vomer forms ...

s, while the areas near the edge of the mouth were made of the palatine

A palatine or palatinus (Latin; : ''palatini''; cf. derivative spellings below) is a high-level official attached to imperial or royal courts in Europe since Roman Empire, Roman times.

and ectopterygoid bones. In the middle of the rear part of the mouth was a rectangular bone known as a parasphenoid

The parasphenoid is a bone which can be found in the cranium of many vertebrates. It is an unpaired dermal bone which lies at the midline of the roof of the mouth. In many reptiles (including birds), it fuses to the endochondral (cartilage-derived ...

. Most of the parasphenoid formed the lower face of the flattened braincase, although it also possesses a thin forward-projecting rod known as a cultriform process

A process is a series or set of activities that interact to produce a result; it may occur once-only or be recurrent or periodic.

Things called a process include:

Business and management

* Business process, activities that produce a specific s ...

, which extends down the midline of the skull to meet the vomers. Towards the back of the mouth, there were the multi-pronged pterygoid bones on each side of the skull. Each pterygoid had several branches, including the posterior branch which stretches back and to the side of the skull, the short medial branch which extends inwards and connects to the parasphenoid bone, an ascending branch which projects upwards to form the otic notch, and finally the anterior branch which extends forward along the palatine and ectopterygoid. The pterygoids of most rhinesuchids have very long anterior branches. In most members of this family, the anterior branch reaches as far forward as the vomers, although ''Australerpeton'' has relatively short anterior branches. A pair of large openings, known as interpterygoid vacuities, fill the areas between these bones, making the majority of the palate open space.

When seen from behind, the upper branches of the braincase

In human anatomy, the neurocranium, also known as the braincase, brainpan, brain-pan, or brainbox, is the upper and back part of the skull, which forms a protective case around the brain. In the human skull, the neurocranium includes the calv ...

(paroccipital processes) extends from side to side, partially concealing the ascending branch of the pterygoids. Each paroccipital process is also perforated by a small hole, known as post-temporal fenestra

A fenestra (fenestration; : fenestrae or fenestrations) is any small opening or pore, commonly used as a term in the biology, biological sciences. It is the Latin word for "window", and is used in various fields to describe a pore in an anatomy, ...

e. These holes are very thin in rhinesuchids. Above these paroccipital processes lie the otic notches as well as the tabular bones. The paroccipital processes also point backwards to some extent, forming horns which in some rhinesuchids are slightly longer than those of the tabulars. When seen from below, the most prominent portion of the braincase is the parasphenoid bone. The rear corners of the parasphenoid have small 'pockets' bordered by ridges (known as ''crista muscularis''). These ridges may have anchored muscles capable of maneuvering the head on the neck.

Other skull and jaw features

Many bones made up the upper side of the skull, although a particular pair of bones acquired a specific design in rhinesuchids. These bones were the elongatedjugal

The jugal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians and birds. In mammals, the jugal is often called the malar or zygomatic. It is connected to the quadratojugal and maxilla, as well as other bones, which may vary by species.

Anatomy ...

and prefrontal bones, which formed the front edge of the orbits

In celestial mechanics, an orbit (also known as orbital revolution) is the curved trajectory of an physical body, object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an satellite, artificia ...

(eye holes). In most rhinesuchids, the edge between the two bones possessed a 'stepped' shape, with a triangular outer extension of the prefrontal pushing the suture with the jugal towards a more lateral (outwards) position. However, the suture is more straight in ''Australerpeton'', like in other stereospondyls.

The lower jaw has a pair of holes only visible from the inside edge of the jaw. The larger hole at the rear part of the bone complex, known as a posterior Meckelian foramen, was thin and elongated in rhinesuchids. An additional hole on the underside of the jaw joint is only visible from below. This hole, the chorda tympani

Chorda tympani is a branch of the facial nerve that carries gustatory (taste) sensory innervation from the front of the tongue and parasympathetic ( secretomotor) innervation to the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands.

Chorda tymp ...

c foramen, was large in this family. On the upper side of the jaw joint, a thin groove known as an arcadian groove stretches towards the lingual (tongue) side of the jaw and separates other bony bumps located among the jaw joint. As a whole, the grooves and ridges of the jaw joint were poorly developed in rhinesuchids compared to that of many other stereospondyl groups, instead resembling the simple joint of archegosaurids such as '' Melosaurus''.

Paleobiology

Most rhinesuchids are only known from skull material, although a few members of the group (''Uranocentrodon'', ''Broomistega

''Broomistega'' is an extinct genus of temnospondyl in the family Rhinesuchidae. It is known from one species, ''Broomistega putterilli'', which was renamed in 2000 from ''Lydekkerina putterilli'' Broom 1930. Fossils are known from the Early Tri ...

'', and ''Australerpeton'', for example) include specimens preserving a significant portion of the rest of the skeleton. A juvenile specimen of ''Broomistega'' had ankles and vertebrae which were poorly ossified

Ossification (also called osteogenesis or bone mineralization) in bone remodeling is the process of laying down new bone material by cells named osteoblasts. It is synonymous with bone tissue formation. There are two processes resulting in t ...

, indicating that its joints had a large amount of cartilaginous

Cartilage is a resilient and smooth type of connective tissue. Semi-transparent and non-porous, it is usually covered by a tough and fibrous membrane called perichondrium. In tetrapods, it covers and protects the ends of long bones at the joints ...

material to supplement the low amount of bone. This trait is often correlated with an aquatic lifestyle. Features of the skull, such as upwards-pointing eyes, also support this hypothesis.

Despite this support for an aquatic lifestyle, other pieces of evidence show that rhinesuchids were capable of some terrestrial movement. Although rhinesuchids did not possess any adaptations for digging, the poorly ossified juvenile specimen of ''Broomistega'' was found in a flooded burrow which was also inhabited by a ''

Despite this support for an aquatic lifestyle, other pieces of evidence show that rhinesuchids were capable of some terrestrial movement. Although rhinesuchids did not possess any adaptations for digging, the poorly ossified juvenile specimen of ''Broomistega'' was found in a flooded burrow which was also inhabited by a ''Thrinaxodon

''Thrinaxodon'' is an extinct genus of cynodonts which lived in what are now South Africa and Antarctica during the Late Permian - Early Triassic. ''Thrinaxodon'' lived just before, during, and right after the Permian–Triassic mass extinction ...

''. Various conditions of the way these animals were preserved indicate that they co-inhabited the burrow peacefully, likely to survive a drought by aestivating (staying in a dormant state during hot and dry conditions). The fact that a ''Broomistega'' was able to enter the burrow of a terrestrial animal such as ''Thrinaxodon'' indicates that rhinesuchids were not exclusively aquatic.

In addition, it has been noted that larger temnospondyls generally have more well-ossified joints. For example, large specimens of ''Australerpeton'' possessed robust hips, several completely bony ankle bones, and ossified pleurocentra (part of the vertebrae). Nevertheless, these skeletons were not as strongly built as those of '' Eryops'' (a supposedly terrestrial temnospondyl), with smaller shoulder girdles and less prominent sites for muscle attachment. Dias & Schultz (2003) suggested that the lifestyle of ''Australerpeton'' (and presumably other rhinesuchids) was that of a semiaquatic piscivore

A piscivore () is a carnivorous animal that primarily eats fish. Fish were the diet of early tetrapod evolution (via water-bound amphibians during the Devonian period); insectivory came next; then in time, the more terrestrially adapted repti ...

(fish-eater), preferring to hunt in shallow bodies of freshwater yet retaining the ability to walk on land during droughts.

A Histological

Histology,

also known as microscopic anatomy or microanatomy, is the branch of biology that studies the microscopic anatomy of biological tissue (biology), tissues. Histology is the microscopic counterpart to gross anatomy, which looks at large ...

study of several indeterminate rhinesuchid fossils (referred to ''Rhinesuchus'') indicate that members of the family grew season

A season is a division of the year based on changes in weather, ecology, and the number of daylight hours in a given region. On Earth, seasons are the result of the axial parallelism of Earth's axial tilt, tilted orbit around the Sun. In temperat ...

ally, as in modern amphibians. Individuals also had fairly long life span, with one specimen being 30 to 35 years old at the time of its death based on the number of lines of arrested growth

Growth arrest lines, also known as Harris lines, are lines of increased bone density that represent the position of the growth plate at the time of insult to the organism and formed on long bones due to growth arrest. They are only visible by ra ...

(rings in the bone used to tell age, like tree rings) present in a hip fragment. Some lines of arrested growth were very narrow, indicating that the individuals could reduce their growth and metabolism

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the co ...

during times of hardship. This ability may be the reason why rhinesuchids were rather successful at the end of the Permian, as well as how a few small members of the group survived the Permian-Triassic extinction event.

Gills

Three rows of tiny bones (branchial ossicles) covered with thin tooth-like structures (branchial denticles) have been preserved near the neck of one specimen of ''Uranocentrodon''. These bones almost certainly attached to thebranchial arch

Branchial arches or gill arches are a series of paired bony/ cartilaginous "loops" behind the throat ( pharyngeal cavity) of fish, which support the fish gills. As chordates, all vertebrate embryos develop pharyngeal arches, though the eve ...

es of gill

A gill () is a respiration organ, respiratory organ that many aquatic ecosystem, aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow r ...

s while the animal was alive. Although such bones are rare among stereospondyls and unknown in any other rhinesuchids, this may simply be due to the fact that the bones of other genera were preserved in more rough-grained sediments where such delicate bones could be broken or difficult to find.

Although evidently ''Uranocentrodon'' had gills of some kind, it is difficult to determine what kind of gills they were. On the one hand, they could have been internal gills like those of fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

, which were hardly visible from the outside of the body. On the other hand, they could have been stalk-like external gills

External gills are the gills of an animal, most typically an amphibian, that are exposed to the environment, rather than set inside the pharynx and covered by gill slits, as they are in most fishes. Instead, the respiratory organs are set on a fri ...

like those of modern salamander

Salamanders are a group of amphibians typically characterized by their lizard-like appearance, with slender bodies, blunt snouts, short limbs projecting at right angles to the body, and the presence of a tail in both larvae and adults. All t ...

larvae or even neotenic

Neoteny (), also called juvenilization,Montagu, A. (1989). Growing Young. Bergin & Garvey: CT. is the delaying or slowing of the physiological, or somatic, development of an organism, typically an animal. Neoteny in modern humans is more signif ...

adult salamanders such as the mudpuppy or axolotl

The axolotl (; from ) (''Ambystoma mexicanum'') is a neoteny, paedomorphic salamander, one that Sexual maturity, matures without undergoing metamorphosis into the terrestrial adult form; adults remain Aquatic animal, fully aquatic with obvio ...

. External gills had to have evolved from internal gills sometime during amphibian evolution, although the precise location of this transition is controversial. The gill-supporting bones preserved in ancient amphibians show many similarities with those of fish gills and salamander gills. Paleontologists who prefer comparing ancient tetrapods to modern amphibians generally find many similarities between the fossil bones and modern salamander gill bones. On the other hand, paleontologists who compare fossil tetrapods to fossil fish consider the bones to correlate with internal gills. This conundrum, known as Bystrow's paradox, has made it difficult to assess gills in ancient amphibians such as ''Uranocentrodon,'' as different paleontologists come to different conclusions based on their field of study.

Bystrow's paradox was finally resolved by a 2010 study, which found that grooved ceratobrachnial structures (components of the branchial arches) are correlated with internal gills. Ancient tetrapods which preserved grooved ceratobranchials, such as the dvinosaur ''

Bystrow's paradox was finally resolved by a 2010 study, which found that grooved ceratobrachnial structures (components of the branchial arches) are correlated with internal gills. Ancient tetrapods which preserved grooved ceratobranchials, such as the dvinosaur ''Dvinosaurus

''Dvinosaurus'' is an extinct genus of amphibious Temnospondyli, temnospondyls localized to regions of western and central Russia during the Middle Permian, middle and late Permian, approximately 265-254 million years ago. Its discovery was first ...

'', probably only had internal gills as adults. Nevertheless, external gills have been directly preserved as soft tissue in some temnospondyls. However, these situations only occur in larval specimens or members of specialized groups such as the branchiosaurids

Branchiosauridae is an extinct family of small amphibamiform temnospondyls with external gills and an overall juvenile appearance. The family has been characterized by hundreds of well-preserved specimens from the Permo-Carboniferous of Middle Eu ...

. One living species of lungfish

Lungfish are freshwater vertebrates belonging to the class Dipnoi. Lungfish are best known for retaining ancestral characteristics within the Osteichthyes, including the ability to breathe air, and ancestral structures within Sarcopterygii, inc ...

('' Lepidosiren'') has external gills as larvae which transform into internal gills as adults. Despite adult dvinosaur specimens having skeletal features correlated with internal gills, some larval specimens of another dvinosaur, '' Isodectes'' preserved soft tissue external gills. Thus, the gill development of dvinosaurs (and presumably other temnospondyls, such as ''Uranocentrodon'') mirrored that of ''Lepidosiren''. Despite this feature likely being an example of convergent evolution (as other lungfish exclusively possessed internal gills), it still remains a useful gauge for how temnospondyl gills developed. The study's writers concluded that the gills of temnospondyls (including ''Uranocentrodon'' and other rhinesuchids which may have possessed gills) were probably internal (like those of a fish) as an adult, but external (like those of a salamander) as a larva.

Body armor

One ''Uranocentrodon'' skeleton also preserved large patches of bonyscute

A scute () or scutum (Latin: ''scutum''; plural: ''scuta'' "Scutum (shield), shield") is a bony external plate or scale overlaid with horn, as on the shell of a turtle, the skin of crocodilians, and the feet of Bird anatomy#Scales, birds. The ter ...

s or scales around the body. The scutes which would have been on the belly of the animal were arranged in parallel diagonal rows which converged at the midline of the body and diverged as the rows stretched towards the tail. Each scute had a ridge running down the middle, and the scutes further towards the midline overlapped the ones further out. Along the midline, a row of flat and wide scales stretched from the throat to the tail. While these belly scales were made of bone, scales on other parts of the body had less bone structure and were probably made of keratin

Keratin () is one of a family of structural fibrous proteins also known as ''scleroproteins''. It is the key structural material making up Scale (anatomy), scales, hair, Nail (anatomy), nails, feathers, horn (anatomy), horns, claws, Hoof, hoove ...

instead. The scales on the sides of the body were flatter and smaller than the bony belly scutes. The scutes on the back of the body were similar, although more rounded in shape, with a few larger scutes near the midline. The scales of the hind limbs and the underside of the hip region were similar to those of the back, although no integument

In biology, an integument is the tissue surrounding an organism's body or an organ within, such as skin, a husk, Exoskeleton, shell, germ or Peel (fruit), rind.

Etymology

The term is derived from ''integumentum'', which is Latin for "a coverin ...

was preserved on the forelimbs or tail. Thus, it is likely that at least the tail was unarmored and only covered with naked skin.

Scales have also been preserved in ''Australerpeton'' specimens. They are similar in distribution to those of ''Uranocentrodon'', but are generally rounder in shape. They also possessed a honeycomb-like internal structure and histological features which indicate that they were deeply embedded in skin. Therefore, it is unlikely that they would have been visible from the outside of the body. It cannot be determined whether the scales or scutes of rhinesuchids would have enabled or restricted cutaneous respiration

Cutaneous respiration, or cutaneous gas exchange (sometimes called skin breathing), is a form of respiration in which gas exchange occurs across the skin or outer integument of an organism rather than gills or lungs. Cutaneous respiration may be ...

(breathing through the skin as in modern amphibians). Other potential applications of the scales included protection against predators, retaining water during droughts, and possibly even for storing calcium

Calcium is a chemical element; it has symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar to it ...

when conditions are harsh (a technique used by female African crocodiles).This last hypothesis is the least likely, as rhinesuchids did not lay hard-shelled eggs, which is the reason female crocodiles need to store calcium.

Classification

When the family was first named in 1919, Rhinesuchidae was already recognized as a group of basal stereospondyls, a position which it retains even in the present day. Among the traits used to support this position include the fact that most rhinesuchids had long anterior branches of their pterygoids. More advanced stereospondyls had shorter anterior branches. In 1947,Alfred Romer

Alfred Sherwood Romer (December 28, 1894 – November 5, 1973) was an American paleontologist and biologist and a specialist in vertebrate evolution.

Biography

Alfred Romer was born in White Plains, New York, the son of Harry Houston Romer an ...

placed the family (which he believed only included ''Rhinesuchus'') in a broad superfamily which he called Rhinesuchoidea. Rhinesuchoidea was intended to be part of an evolutionary grade

A grade is a taxon united by a level of morphological or physiological complexity. The term was coined by British biologist Julian Huxley, to contrast with clade, a strictly phylogenetic unit.

Phylogenetics

The concept of evolutionary grades ...

of temnospondyls linking "primitive" rhachitomes such as '' Eryops'' to "advanced" stereospondyls such as metoposaurs and trematosaurs

Trematosauria is one of two major groups of temnospondyl amphibians that survived the Permian-Triassic extinction event, the other (according to Yates and Warren 2000) being the Capitosauria. The trematosaurs were a diverse and important group t ...

. This grade, termed "neorhachitomes", was separated into Capitosauroidea

The Mastodonsauroidea are an extinct superfamily of temnospondyl amphibians known from the Triassic. Fossils belonging to this superfamily have been found in North America, Greenland, Europe, Asia, and Australia. '' Ferganobatrachus'' from the ...

(which contained capitosaurs and " benthosuchids") and Rhinesuchoidea. Apart from containing Rhinesuchidae, Rhinesuchoidea also contained various genera as well as the families Lydekkerinidae, Sclerothoracidae, and finally Uranocentrodon

''Uranocentrodon'' is an extinct genus of temnospondyls in the family Rhinesuchidae. Known from a skull, ''Uranocentrodon'' was a large predator with a length up to . Originally named ''Myriodon'' by van Hoepen in 1911, it was transferred to a ...

tidae. Romer felt that certain taxa (i.e. ''Uranocentrodon'' and the possibly synonymous dubious genus "''Laccocephalus"'') often considered rhinesuchids were best placed in the separate family Uranocentrodontidae, while others (i.e. ''Rhinesuchoides

''Rhinesuchoides'' is an extinct genus of temnospondyls in the family Rhinesuchidae. It contains two species, ''R. tenuiceps'' and ''R. capensis'', both from the Karoo Supergroup of South Africa. The latter was formerly a species of ''Rhinesuchus ...

'') were not placed in any rhinesuchoid family in particular. Other families were later placed in this Rhinesuchoidea, such as Rhinecepidae in 1966 and Australerpeton

''Australerpeton'' is an extinct genus of stereospondylomorph temnospondyl currently believed to belong to the family Rhinesuchidae. When first named in 1998, the genus was placed within the new family Australerpetontidae. However, studies publ ...

idae in 1998.

The arrival of

The arrival of cladistics

Cladistics ( ; from Ancient Greek 'branch') is an approach to Taxonomy (biology), biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesiz ...

in the late 20th century has caused grades to fall out of favor in recent years, replaced by clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

s, which are defined by close relations rather than ancestral assemblages. However, the basic idea behind Rhinesuchoidea, which states that advanced stereospondyls descended from animals similar to rhinesuchids, is still considered valid. Rhinecepidae and Uranocentrodontidae were found to be synonymous with Rhinesuchidae according to a 2000 analysis by Schoch and Milner. One study placed Rhinesuchidae within the superfamily Capitosauroidea. However, this interpretation has not been followed by other studies which consider rhinesuchids to be more basal than capitosaurs. Australerpetonidae, a monotypic family only containing the genus ''Australerpeton'', has been more difficult to compare to Rhinesuchidae. Some studies place ''Australerpeton'' as a basal stereospondyl outside of Rhinesuchidae, while others consider it an archegosaurid outside of Stereospondyli entirely.Schoch, R. R., and Milner, A. R. 2000. Stereospondyli, stem-Stereospondyli, Rhinesuchidae, Rhytidostea, Trematosauroidea, Capitosauroidea. ''Handbuch der Paläoherpetologie'', Munich, 3b:1-203.

A comprehensive review of ''Australerpeton'' published by Eltink ''et al.'' (2016) favored the hypothesis that it was deeply nested within Rhinesuchidae. A phylogenetic study performed as part of the study split the family into two clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

s. One clade was a subfamily

In biological classification, a subfamily (Latin: ', plural ') is an auxiliary (intermediate) taxonomic rank, next below family but more inclusive than genus. Standard nomenclature rules end botanical subfamily names with "-oideae", and zo ...

termed Rhinesuchinae. Rhinesuchinae contains ''Rhinesuchus'' and ''Rhineceps

''Rhineceps'' is an extinct genus of temnospondyl amphibian in the family Rhinesuchidae. ''Rhineceps'' was found in Northern Malawi (formerly Nyasaland) in Southern Africa known only from its type species ''R. nyasaensis''. ''Rhineceps'' was a la ...

''. This subfamily is mainly characterized by features of the palate, such as an anterior branch of the pterygoid lacking ridges and palatine bones covered in tiny denticles. The other main clade of the family contained ''Uranocentrodon'' as well as another subfamily termed Australerpetinae. This clade is united by the presence of a tympanic crest and a foramen magnum (the hole for the spinal cord at the back of the braincase) which has a curved upper edge. Australerpetinae is a modified version of Australerpetonidae which has been reduced to subfamily status in order to fit within Rhinesuchidae. This subfamily contains ''Australerpeton'', ''Broomistega'', ''Laccosaurus

''Laccosaurus'' is an extinct monotypic genus of rhinesuchid temnospondyl, the type species being ''Laccosaurus watsoni''.

History of study

''Laccosaurus'' ''watsoni'' was named by paleontologist Sidney H. Haughton in 1925 on the basis of a ...

'', and ''Rhinesuchoides

''Rhinesuchoides'' is an extinct genus of temnospondyls in the family Rhinesuchidae. It contains two species, ''R. tenuiceps'' and ''R. capensis'', both from the Karoo Supergroup of South Africa. The latter was formerly a species of ''Rhinesuchus ...

''. Members of this subfamily had somewhat longer and more tapered snouts than other Rhinesuchids, although (according to Eltink ''et al.''.) their pterygoids had short anterior branches, letting the palatine bones contact the interpterygoid vacuities. The most parsimonious (evolutionarily simplest) tree found by Eltink ''et al.'' (2016) is seen below:

The structure of Rhinesuchidae following Eltink ''et al.'s'' study was challenged by a different study on rhinesuchids published less than a year later. This study, Mariscano ''et al.''. (2017), agreed that ''Australerpeton'' was a rhinesuchid, but considered it the most basal member of the family. They disagree with Eltink ''et al.'s'' recognition of short anterior pterygoid branches in multiple genera. According to their analysis, only ''Australerpeton'' possessed this trait, the main feature which separates it from the rest of Rhinesuchidae. Other traits which support this separation include the fact that other rhinesuchids have stepped jugal-prefrontal contact and toothless coronoid bones in the lower jaw. The rest of the family was poorly resolved in their phylogenetic analysis, although three clades did have moderate Bremer support values of 2.

Bremer support is gauged by counting the number of times analyzed traits are acquired, lost, or reacquired within a family tree. Some family trees include more of these transitions than others, meaning that some possible trees assumed that more than the bare minimum amount of evolution had taken place. The family tree with the fewest of these 'steps' (transitions) is likely to be the most accurate, based on the principal of occam's razor

In philosophy, Occam's razor (also spelled Ockham's razor or Ocham's razor; ) is the problem-solving principle that recommends searching for explanations constructed with the smallest possible set of elements. It is also known as the principle o ...

(the simplest answer is the most accurate). Bremer support is used to label how well-supported clades are by analyzing how they are distributed among more complex alternatives to the simplest (most parsimonious) tree. Clades which do not exist in a family tree which is only one total step more complex than the MPT (most parsimonious tree) have a Bremer support of 1, meaning that the clade's existence is very uncertain. Even if the MPT of the present analysis supports their existence, new data may make a competing family tree more parsimonious, dissolving clades which are only supported in the current MPT. Other clades may have much higher Bremer support values, indicating that more drastic assumptions have to be formulated to render the clade invalid. Rhinesuchidae as a whole, for example, has a Bremer support of 6 in Mariscano ''et al''. (2017), which is considered high support. A Bremer support of 2, as is the case with three specific clades in this analysis, is considered moderate. One of these clades included the two valid species of ''Rhinesuchoides'', while another clade connected ''Rhineceps'' and ''Uranocentrodon'', and the last contained ''Rhinesuchus'' and ''Laccosaurus''. The arrangement of these clades (as well as the placement of ''Broomistega'') could not be resolved with absolute confidence, with Bremer support values of only 1 regardless of where the three clades were placed among non-''Australerpeton'' Rhinesuchidae. The most parsimonious tree found by Mariscano ''et al.'' (2017) is seen below:

Gallery

Rhinesuchus whaitsi

''Rhinesuchus'' (meaning "rasp crocodile" for the ridged surface texture on its skull bones) is a large temnospondyl. Remains of the genus are known from the Permian of the South African Karoo Basin's ''Tapinocephalus'' and ''Cistecephalus'' as ...

'', of the middle

Middle or The Middle may refer to:

* Centre (geometry), the point equally distant from the outer limits.

Places

* Middle (sheading), a subdivision of the Isle of Man

* Middle Bay (disambiguation)

* Middle Brook (disambiguation)

* Middle Creek ...

to late Permian

Late or LATE may refer to:

Everyday usage

* Tardy, or late, not being on time

* Late (or the late) may refer to a person who is dead

Music

* ''Late'' (The 77s album), 2000

* Late (Alvin Batiste album), 1993

* Late!, a pseudonym used by Dave Groh ...

of South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

Australerpeton12DB.jpg, ''Australerpeton cosgriffi

''Australerpeton'' is an extinct genus of stereospondylomorph temnospondyl currently believed to belong to the family Rhinesuchidae. When first named in 1998, the genus was placed within the new family Australerpetontidae. However, studies publ ...

'', an unusually long-snouted rhinesuchid of the middle to late Permian of Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

Uranocentr10 copy.jpg, '' Uranocentrodon senekalensis'', of the late Permian of South Africa

Rhineceps nyasaensis.jpg, '' Rhineceps nyasaensis'', of the late Permian of Malawi

Malawi, officially the Republic of Malawi, is a landlocked country in Southeastern Africa. It is bordered by Zambia to the west, Tanzania to the north and northeast, and Mozambique to the east, south, and southwest. Malawi spans over and ...

Broomistega putterilli.jpg, ''Broomistega putterilli

''Broomistega'' is an extinct genus of temnospondyl in the family Rhinesuchidae. It is known from one species, ''Broomistega putterilli'', which was renamed in 2000 from ''Lydekkerina putterilli'' Broom 1930. Fossils are known from the Early Tri ...

'', of the early Triassic

The Early Triassic is the first of three epochs of the Triassic Period of the geologic timescale. It spans the time between 251.9 Ma and Ma (million years ago). Rocks from this epoch are collectively known as the Lower Triassic Series, which ...

of South Africa

References

{{Taxonbar, from=Q2566755 Stereospondyli Guadalupian first appearances Early Triassic extinctions Temnospondyl families