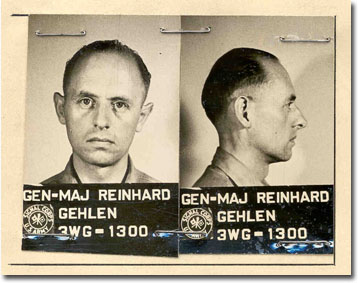

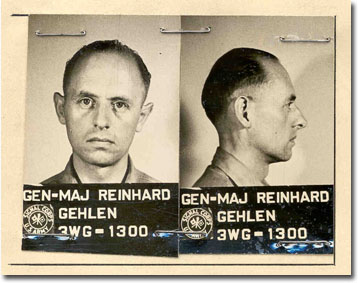

Reinhard Gehlen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Reinhard Gehlen (3 April 1902 – 8 June 1979) was a German military and

In spring of 1942, Lieutenant Colonel Gehlen assumed command of the Foreign Armies East (FHO) after the dismissal of Colonel Kinzel. Prior to that he had little intelligence experience, though he did have interactions with military intelligence, the ''

In spring of 1942, Lieutenant Colonel Gehlen assumed command of the Foreign Armies East (FHO) after the dismissal of Colonel Kinzel. Prior to that he had little intelligence experience, though he did have interactions with military intelligence, the ''

On 22 May 1945, Gehlen surrendered to the Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) of the U.S. Army in

On 22 May 1945, Gehlen surrendered to the Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) of the U.S. Army in

On 1 April 1956, 11 years after World War II had ended, the U.S. Government and the CIA formally transferred the Gehlen Organization to the authority of what was by then the Federal Republic of Germany, under Chancellor

On 1 April 1956, 11 years after World War II had ended, the U.S. Government and the CIA formally transferred the Gehlen Organization to the authority of what was by then the Federal Republic of Germany, under Chancellor

"The Secret Treaty of Fort Hunt."

''CovertAction Information Bulletin''. * Reese, Mary Ellen. ''General Reinhard Gehlen: The CIA Connection''. Fairfax, Vir.: George Mason University. 1990 * United States National Archives, Washington, D.C. NARA Collection of Foreign Records Seized, Microfilm T-77, T-78 * Tim Weiner, Weiner, Tim (2008). ''Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA''. Anchor Books, pp. 10–190. . *

"Disclosure" newsletter, Information promulgated by the U.S. National Archives & Records Administration

CIA declassified documents on the Gehlen Organization. * iarchive:GehlenReinhard, Reinhard Gehlen's CIA file on the Internet Archive. {{DEFAULTSORT:Gehlen, Reinhard 1902 births 1979 deaths Cold War history of Germany Cold War spymasters German anti-communists German Army generals of World War II German people of Flemish descent Grand Crosses with Star and Sash of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Lieutenant generals of the German Army Major generals of the German Army (Wehrmacht) Military personnel from Erfurt Military personnel from the Province of Saxony People of the Federal Intelligence Service Recipients of the Iron Cross (1939), 2nd class Recipients of the War Merit Cross Spies for the Federal Republic of Germany Spymasters World War II spies for Germany

intelligence officer

An intelligence officer is a member of the intelligence field employed by an organization to collect, compile or analyze information (known as intelligence) which is of use to that organization. The word of ''officer'' is a working title, not a r ...

, later dubbed "Hitler's Super Spy," who served the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic, officially known as the German Reich, was the German Reich, German state from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclai ...

, Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

, and West Germany

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republi ...

, and also worked for the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

during the early years of the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

. He led the Gehlen Organization, which worked with the CIA from its founding, employing former SS and Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

officers, and later became the first head of West Germany's Federal Intelligence Service (BND). In years prior, he was in charge of German military intelligence on the Eastern Front during World War II and later became one of the founders of the West German armed forces, the Bundeswehr

The (, ''Federal Defence'') are the armed forces of the Germany, Federal Republic of Germany. The is divided into a military part (armed forces or ''Streitkräfte'') and a civil part, the military part consists of the four armed forces: Germ ...

.

The son of an army officer and World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

veteran, in 1920 Gehlen joined the Reichswehr

''Reichswehr'' (; ) was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first two years of Nazi Germany. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshaped ...

, the truncated army of the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic, officially known as the German Reich, was the German Reich, German state from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclai ...

, and was an operations staff officer in an infantry division during the invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

in 1939. After that he was appointed to the staff of General Franz Halder, the Chief of the Army High Command (OKH), and quickly became one of his main assistants. Gehlen had a significant role in planning the German operations in Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

, Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

, and the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. When the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

continued to fight after the initial German success during Operation Barbarossa, in the spring of 1942 Gehlen was appointed by Halder as director of Foreign Armies East (FHO), the military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis List of intelligence gathering disciplines, approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist Commanding officer, commanders in decision making pr ...

service of the OKH tasked with analyzing the Soviet armed forces. He achieved the rank of major general before he was dismissed by Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

in April 1945 because of the FHO's alleged "defeatism" and accurate but pessimistic intelligence reports about Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

military superiority.

Following the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Gehlen surrendered to the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

. While in a POW camp, Gehlen offered FHO's microfilmed and secretly buried archives about the USSR and his own services to the U.S. intelligence community. Following the start of the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, the U.S. military (G-2 Intelligence) accepted Gehlen's offer and assigned him to establish the Gehlen Organization, an espionage service focusing on the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and Soviet Bloc. Beginning with his time as head of the Gehlen Organization, Gehlen favored both Atlanticism and close cooperation between what would become West Germany, the U.S. intelligence community, and the other members of the NATO military alliance

A military alliance is a formal Alliance, agreement between nations that specifies mutual obligations regarding national security. In the event a nation is attacked, members of the alliance are often obligated to come to their defense regardless ...

. The organization employed hundreds of former members of the Nazi Party and former Wehrmacht military intelligence officers.

After West Germany regained its sovereignty, Gehlen became the founding president of the Federal Intelligence Service (''Bundesnachrichtendienst'', BND) of West Germany

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republi ...

(1956–68). Gehlen obeyed a direct order from West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer

Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer (5 January 1876 – 19 April 1967) was a German statesman and politician who served as the first Chancellor of Germany, chancellor of West Germany from 1949 to 1963. From 1946 to 1966, he was the first leader of th ...

, and also hired former counterintelligence

Counterintelligence (counter-intelligence) or counterespionage (counter-espionage) is any activity aimed at protecting an agency's Intelligence agency, intelligence program from an opposition's intelligence service. It includes gathering informati ...

officers of the ''Schutzstaffel

The ''Schutzstaffel'' (; ; SS; also stylised with SS runes as ''ᛋᛋ'') was a major paramilitary organisation under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany, and later throughout German-occupied Europe during World War II.

It beg ...

'' (SS) and the '' Sicherheitsdienst'' (SD), in response to an alleged avalanche of covert ideological subversion hitting West Germany from the intelligence services behind the Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political and physical boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. On the east side of the Iron Curtain were countries connected to the So ...

.

Gehlen was instrumental in negotiations to establish an official West German intelligence service based on the Gehlen Organization of the early 1950s. In 1956, the Gehlen Organization was transferred to the West German government and formed the core of the Federal Intelligence Service (BND), the Federal Republic of Germany's official foreign intelligence service, with Gehlen serving as its first president until his retirement in 1968. While this was a civilian office, he was also a lieutenant-general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was normall ...

in the Reserve forces of the Bundeswehr

The (, ''Federal Defence'') are the armed forces of the Germany, Federal Republic of Germany. The is divided into a military part (armed forces or ''Streitkräfte'') and a civil part, the military part consists of the four armed forces: Germ ...

, the highest-ranking reserve-officer in the military of West Germany.

Early life and career

Gehlen was born 1902 into a Protestant family inErfurt

Erfurt () is the capital (political), capital and largest city of the Central Germany (cultural area), Central German state of Thuringia, with a population of around 216,000. It lies in the wide valley of the Gera (river), River Gera, in the so ...

and had two brothers and a sister. His father was Walther Gehlen, an officer in the Imperial German Army

The Imperial German Army (1871–1919), officially referred to as the German Army (), was the unified ground and air force of the German Empire. It was established in 1871 with the political unification of Germany under the leadership of Kingdom o ...

during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, and his mother, Katharina Margaret Gehlen (), was a Flemish noblewoman. He grew up in Breslau, where his father, a former army officer, was a publisher for the Ferdinand-Hirt-Verlag, a publishing house specializing in school books. In his youth, Gehlen's main interests were mathematics and horses.

He wanted to follow his father's path and become an army officer, despite the recent defeat of Germany in World War I and the reduction in the size of the army. In 1920, at the age of eighteen, Gehlen completed his Abitur

''Abitur'' (), often shortened colloquially to ''Abi'', is a qualification granted at the end of secondary education in Germany. It is conferred on students who pass their final exams at the end of ISCED 3, usually after twelve or thirteen year ...

and joined the Reichswehr

''Reichswehr'' (; ) was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first two years of Nazi Germany. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army () was dissolved in order to be reshaped ...

. In 1921 he was posted to the 6th Light Artillery Regiment (later the 3rd Prussian Artillery Regiment) in Schweidnitz, a town in Silesia

Silesia (see names #Etymology, below) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at 8, ...

near the Polish border, and 1923 he became a lieutenant. He graduated from the infantry and artillery schools. Gehlen received an assignment at the cavalry school in Hanover

Hanover ( ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the States of Germany, German state of Lower Saxony. Its population of 535,932 (2021) makes it the List of cities in Germany by population, 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-l ...

in 1926, where he spent two years before requesting a transfer, and in 1928 he was sent to back to his original unit in Schweidnitz. There he met a secretary working for the military, Herta von Seydlitz-Kurzbach, and they married in 1931. She was a member of an aristocratic Prussian military family.

After Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

rose to power in 1933 there was an expansion of the Reichswehr, including more opportunities for officers to receive promotions. That same year in October, Gehlen began attending the "Commander Assistants Training," the equivalent of the German staff college during the Weimar Republic, and in June 1935 he graduated as second in his class. The following month he was promoted to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

and assigned to the "Troop Office," or what was renamed the German General Staff

The German General Staff, originally the Prussian General Staff and officially the Great General Staff (), was a full-time body at the head of the Prussian Army and later, the Imperial German Army, German Army, responsible for the continuous stu ...

in 1936. During his early years on the General Staff, in October 1936 he was assigned to the Operations Section, and in the following year he was reassigned to the Fortifications Section. In November 1938 Gehlen was again posted to an artillery regiment.

Second World War

At the time of the Germany'sinvasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

in September 1939, Gehlen was a major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

and an operations staff officer in the 213th Infantry Division. It was mobilized for the Polish campaign but did not see any action, being held in reserve. He was still awarded the Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, the German Empire (1871–1918), and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). The design, a black cross pattée with a white or silver outline, was derived from the in ...

, second class. In late 1939 he was transferred to the staff of General Franz Halder, the Chief of the ''Oberkommando des Heeres

The (; abbreviated OKH) was the high command of the Army of Nazi Germany. It was founded in 1935 as part of Adolf Hitler's rearmament of Germany. OKH was ''de facto'' the most important unit within the German war planning until the defeat ...

'' (OKH), the Army High Command. In his early work, Gehlen was once again planning the construction of fortifications, both along the Soviet border and in the west. Halder increasingly relied on Gehlen during the spring of 1940 and he became one of Halder's main assistants. Gehlen was sent as his liaison officer to several German units that were involved in the Battle of France

The Battle of France (; 10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign (), the French Campaign (, ) and the Fall of France, during the Second World War was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembour ...

in May 1940 (the 16th Army and the Panzer Group), and in October of that year he was assigned to the Eastern Group of the Operations Section, led by Colonel Adolf Heusinger. Heusinger—who incidentally would later work with Gehlen after the war, as the first head of the West German Bundeswehr

The (, ''Federal Defence'') are the armed forces of the Germany, Federal Republic of Germany. The is divided into a military part (armed forces or ''Streitkräfte'') and a civil part, the military part consists of the four armed forces: Germ ...

—also recognized Gehlen's talent as a staff officer.

From late 1940 Gehlen worked on operational planning for Germany's movement east. That included the invasion and occupation of Greece and Yugoslavia, as well as the preparations for Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along ...

. In February 1941 Gehlen was described in a report by his superiors as "a fine example of a general staff officer ... Great operational ability and a great deal of foresight in his thinking." He was also noted to be very hardworking. His role in Barbarossa was mainly planning for the difficulties of bringing reserves up to the front, separating the areas of the army groups and armies in the invasion, and arranging transportation. For this work Gehlen was awarded the War Merit Cross, first and second classes, in the spring of 1941.

As Operation Barbarossa began and the Red Army continued to fight despite its losses, Halder became upset at his intelligence department for not informing him of the true extent of Soviet military capabilities. In late 1941 Gehlen was being considered to replace Colonel Eberhard Kinzel as the head of Foreign Armies East (''Fremde Heere Ost'', FHO), the Army Staff section responsible for analyzing the Soviet Union, on the recommendation of Colonel Heusinger. Halder was dissatisfied with Kinzel's performance and was looking for a replacement, though he thought that the 40-year old Gehlen was too young for such an important role and had no previous intelligence background. Heusinger believed that Gehlen was a good manager, and on his advice, Gehlen was appointed the head of FHO on 1 April 1942.

Head of FHO

Abwehr

The (German language, German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', though the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context) ) was the German military intelligence , military-intelligence service for the ''Reichswehr'' and the ...

'', during his earlier work at the Army High Command, to the point where he received a warning for meddling too much in the affairs of that agency.

Before the Wehrmacht disasters in the Battle of Stalingrad (23 August 1942 – 2 February 1943), a year into the German war against the Soviet Union, Gehlen understood that the FHO required fundamental re-organization, and secured a staff of army linguists and geographers, anthropologists, lawyers, and junior military officers who would improve the FHO as a military-intelligence organization despite the Nazi ideology of Slavic inferiority.

As leader of the FHO, Gehlen relied heavily on reports from the Max Network from the Klatt Bureau which provided over 10,000 highly accurate reports on Soviet troop movements.

Dismissal, 1945

Gehlen's cadre of FHO intelligence-officers produced accurate field-intelligence about the Red Army that frequently contradictedNazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

ideological perceptions of the eastern battle front. Hitler dismissed the gathered information as defeatism and philosophically harmful to the war effort against " Judeo-Bolshevism" in Russia. In April 1945, despite the accuracy of the intelligence, Hitler dismissed Gehlen, soon after his promotion to major general.

Preparation for Post-War

The FHO collection of both military and political intelligence from captured Red Army soldiers assured Gehlen's post–WWII survival as a Western anticommunist spymaster, with networks of spies and secret agents in the countries of Soviet-occupied Europe. During the German war against the Soviet Union in 1941 to 1945, Gehlen's FHO collected much tacticalmilitary intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis List of intelligence gathering disciplines, approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist Commanding officer, commanders in decision making pr ...

about the Red Army, and much strategic political intelligence about the Soviet Union. Understanding that the Soviet Union would defeat and occupy the Third Reich

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictat ...

, Gehlen ordered the FHO intelligence files copied to microfilm; the FHO files proper were stored in watertight drums and buried in various locations in the Austrian Alps.

They amounted to fifty cases of German intelligence about the Soviet Union, which were at Gehlen's disposal as a bargaining tool with the intelligence services of the Western Allies. Meanwhile, as of 1946, when Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

consolidated his absolute power and control over Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe as agreed at the Potsdam Conference of 1945 and demarcated with what became known as the Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political and physical boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. On the east side of the Iron Curtain were countries connected to the So ...

, the Western Allies of World War II

The Allies, formally referred to as the United Nations from 1942, were an international Coalition#Military, military coalition formed during World War II (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis powers. Its principal members were the "Four Policeme ...

, the U.S, Britain, and France had no sources of covert information within the countries in which the occupying Red Army had vanquished the Wehrmacht.

Cold War

On 22 May 1945, Gehlen surrendered to the Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) of the U.S. Army in

On 22 May 1945, Gehlen surrendered to the Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) of the U.S. Army in Bavaria

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a States of Germany, state in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the list of German states by area, largest German state by land area, comprising approximately 1/5 of the total l ...

and was taken to Camp King, near Oberursel, and interrogated by Captain John R. Boker. The American Army recognised his potential value as a spymaster with great knowledge of Soviet forces and anticommunist intelligence contacts in the Soviet Union. In exchange for his own liberty and the release of his former subordinates (also prisoners of the US Army), Gehlen offered the Counter Intelligence Corps access to the FHO's intelligence archives and to his intelligence gathering abilities aimed at the Soviet Union, known later as the Gehlen Organization. Boker removed his name and those of his Wehrmacht command from the official lists of German prisoners of war, and transferred seven former FHO senior officers to join Gehlen.

The FHO archives were unearthed and secretly taken to Camp King, ostensibly without the knowledge of the camp commander. By the end of summer 1945, Captain Boker had the support of Brigadier General Edwin Sibert, the senior G2 (intelligence) officer of the U.S. Twelfth Army Group,Simpson, pp. 41–42. who arranged the secret transport of Gehlen, his officers and the FHO intelligence archives, authorized by his superiors in the chain of command, General Walter Bedell Smith

General (United States), General Walter Bedell "Beetle" Smith (5 October 1895 – 9 August 1961) was a senior officer (armed forces), officer of the United States Army who served as General Dwight D. Eisenhower's chief of staff at Allied Forc ...

(chief of staff for General Eisenhower), who worked with William Donovan (former OSS chief) and Allen Dulles (OSS chief), who also was the OSS station-chief in Bern

Bern (), or Berne (), ; ; ; . is the ''de facto'' Capital city, capital of Switzerland, referred to as the "federal city".; ; ; . According to the Swiss constitution, the Swiss Confederation intentionally has no "capital", but Bern has gov ...

. On 20 September 1945, Gehlen and three associates were flown from the American Zone of Occupation in Germany to the US, to become spymasters for the Western Allies.

In July 1946, the US officially released Gehlen and returned him to occupied Germany. On 6 December 1946, he began espionage operations against the Soviet Union, by establishing what was known to US intelligence as the Gehlen Organization or "the Org", a secret intelligence service composed of former intelligence officers of the Wehrmacht and members of the SS and the SD, which was headquartered first at Oberursel, near Frankfurt, then at Pullach, near Munich. The organization's cover-name was the South German Industrial Development Organization. Gehlen initially selected 350 ex-Wehrmacht military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis List of intelligence gathering disciplines, approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist Commanding officer, commanders in decision making pr ...

officers as his staff; eventually, the organization recruited some 4,000 anticommunist secret agents.

Gehlen Organization, 1947–56

After he started working for the U.S. Government, Gehlen was subordinate to US Army G-2 (Intelligence). He resented this arrangement and in 1947, the year after his Organization was established, Gehlen arranged for a transfer to theCentral Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

(CIA). The agency kept close control of the Gehlen Organization, because during the early years of the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

of 1945–91, Gehlen's agents were providing the United States Federal Government with more than 70% of its intelligence on the Soviet armed forces

The Armed Forces of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, also known as the Armed Forces of the Soviet Union, the Red Army (1918–1946) and the Soviet Army (1946–1991), were the armed forces of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republi ...

.

Early in 1948, Gehlen Org Spymasters began receiving detailed reports from their sources throughout the Soviet Zone of covert East German remilitarization long before any West German politicians had even thought of such a thing. Further operations by the Gehlen Org produced detailed reports about Soviet construction and testing of the MiG-15 jet-propelled aircraft, which United States airmen flying F-86 fighters would soon to face in aerial combat during the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

.

Between 1947 and 1955, the Gehlen Organization also debriefed every German PoW who returned to West Germany from captivity in the Soviet GULAG

The Gulag was a system of Labor camp, forced labor camps in the Soviet Union. The word ''Gulag'' originally referred only to the division of the Chronology of Soviet secret police agencies, Soviet secret police that was in charge of runnin ...

. The network employed hundreds of former Wehrmacht military intelligence and some SS officers, and also recruited many other agents from within the massive anti-Communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when th ...

ethnic German, Soviet, and East European refugee communities throughout Western Europe. They were accordingly able to develop detailed maps of the railroad systems, airfields, and ports of the USSR, and the Org's field agents even infiltrated the Baltic Soviet Republics and the Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as the Ukrainian SSR, UkrSSR, and also known as Soviet Ukraine or just Ukraine, was one of the Republics of the Soviet Union, constituent republics of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. ...

.

Among the Org's earliest counterespionage successes was Operation Bohemia, which began in March 1948 after Božena Hájková, the sister in law of Czechoslovak military intelligence officer Captain Vojtěch Jeřábek, defected to the American Zone and applied for political asylum in the United States. After learning from Hájková that Captain Jeřábek was secretly expressing anti-communist opinions to his family, the Org dispatched a Czech refugee and veteran field agent codenamed "Ondřej" to make contact with the Captain and his family in Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

. During the night of 8-9 November 1948, after being warned by "Ondřej" of an imminent Stalinist witch hunt for " rootless cosmopolitans" within the Czechoslovak officer corps, Captain Jeřábek and two other senior military intelligence officers crossed the border into the American Zone and defected to the West. In addition to several lists of Czechoslovakian spies in West Germany, Captain Jeřábek also carried the keys to breaking Czechoslovakian intelligence's codes. The results were nothing less than devastating for Czechoslovakian espionage and led to multiple arrests and convictions.

The security and efficacy of the Gehlen Organization were compromised by East German and Soviet moles within it, such as Johannes Clemens, Erwin Tiebel and Heinz Felfe who were feeding information while in the Org and later, while in the BND that was headed by Gehlen. All three were eventually discovered and convicted in 1963.

There were also Communists and their sympathizers within the CIA and the SIS ( MI6), especially Kim Philby and the Cambridge Spies. As such information appeared, Gehlen, personally, and the Gehlen Organization, officially, were attacked by the governments of the Western powers. The British government was especially hostile towards Gehlen, and the politically Left wing British press ensured full publicisation of the existence of the Gehlen Organization, which further compromised the operation.

Federal Intelligence Service (BND), 1956–1968

On 1 April 1956, 11 years after World War II had ended, the U.S. Government and the CIA formally transferred the Gehlen Organization to the authority of what was by then the Federal Republic of Germany, under Chancellor

On 1 April 1956, 11 years after World War II had ended, the U.S. Government and the CIA formally transferred the Gehlen Organization to the authority of what was by then the Federal Republic of Germany, under Chancellor Konrad Adenauer

Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer (5 January 1876 – 19 April 1967) was a German statesman and politician who served as the first Chancellor of Germany, chancellor of West Germany from 1949 to 1963. From 1946 to 1966, he was the first leader of th ...

(1949–63). By way of that transfer of geopolitical sponsorship, the anti–Communist Gehlen Organization became the nucleus of the Bundesnachrichtendienst

The Federal Intelligence Service (, ; BND) is the foreign intelligence agency of Germany, directly subordinate to the Federal Chancellery of Germany, Chancellor's Office. The Headquarters of the Federal Intelligence Service, BND headquarters is ...

(BND, Federal Intelligence Service).

Gehlen was the president of the BND as an espionage service until his retirement in 1968. The end of Gehlen's career as a spymaster resulted from a confluence of events in West Germany: the exposure of a KGB

The Committee for State Security (, ), abbreviated as KGB (, ; ) was the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991. It was the direct successor of preceding Soviet secret police agencies including the Cheka, Joint State Polit ...

mole, Heinz Felfe, (a former SS lieutenant) working at BND headquarters; political estrangement from Adenauer, in 1963, which aggravated his professional problems; and the inefficiency of the BND consequent to Gehlen's poor leadership and continual inattention to the business of counter-espionage as national defence.

According to ''Der Spiegel

(, , stylized in all caps) is a German weekly news magazine published in Hamburg. With a weekly circulation of about 724,000 copies in 2022, it is one of the largest such publications in Europe. It was founded in 1947 by John Seymour Chaloner ...

'' journalists Heinz Höhne and Hermann Zolling, the premature end of the German colonial empire

The German colonial empire () constituted the overseas colonies, dependencies, and territories of the German Empire. Unified in 1871, the chancellor of this time period was Otto von Bismarck. Short-lived attempts at colonization by Kleinstaat ...

in 1918 placed West Germany's new foreign intelligence service, the Bundesnachrichtendienst

The Federal Intelligence Service (, ; BND) is the foreign intelligence agency of Germany, directly subordinate to the Federal Chancellery of Germany, Chancellor's Office. The Headquarters of the Federal Intelligence Service, BND headquarters is ...

at a considerable advantage in dealing with the newly independent governments of post-colonial Africa, Asia, and the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

. This is why many Third World

The term Third World arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, the Southern Cone, NATO, Western European countries and oth ...

military and foreign intelligence services were largely trained by BND military advisor

Military advisors or combat advisors are military Military personnel, personnel deployed to advise on military matters. The term is often used for soldiers sent to foreign countries to aid such countries' militaries with their military education ...

s. This made it possible for the BND to easily receive accurate intelligence in these regions which the CIA and former colonialist intelligence services could not acquire without recruiting local spy rings. BND covert activities in the Third World also laid the groundwork for friendly relations that Gehlen attempted to use to steer local governments into taking an anti-Soviet and pro-NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

stance during the ongoing Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

and further assisted the West German economic miracle by both encouraging and favoring West German trade and corporate investment.

Gehlen's refusal to correct reports with questionable content strained the organization's credibility, and dazzling achievements became an infrequent commodity. A veteran agent remarked at the time that the BND pond then contained some sardines, though a few years earlier the pond had been alive with sharks.

The fact that the BND could score certain successes despite East German Stasi

The Ministry for State Security (, ; abbreviated MfS), commonly known as the (, an abbreviation of ), was the Intelligence agency, state security service and secret police of East Germany from 1950 to 1990. It was one of the most repressive pol ...

interference, internal malpractice, inefficiencies and infighting, was primarily due to select members of the staff who took it upon themselves to step up and overcome then existing maladies. Abdication of responsibility by Reinhard Gehlen was the malignancy; bureaucracy and cronyism remained pervasive, even nepotism (at one time Gehlen had 16 members of his extended family on the BND payroll).Höhne & Zolling, p. 245 Only slowly did the younger generation then advance to substitute new ideas for some of the bad habits caused mainly by Gehlen's semi-retired attitude and frequent holiday absences.

Gehlen was forced out of the BND due to "political scandal within the ranks", according to one source, He retired in 1968 as a civil servant of West Germany, classified as a ''Ministerialdirektor'', a senior grade with a generous pension. His successor, Bundeswehr

The (, ''Federal Defence'') are the armed forces of the Germany, Federal Republic of Germany. The is divided into a military part (armed forces or ''Streitkräfte'') and a civil part, the military part consists of the four armed forces: Germ ...

Brigadier General Gerhard Wessel, immediately called for a program of modernization and streamlining.

Honors

*Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, the German Empire (1871–1918), and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). The design, a black cross pattée with a white or silver outline, was derived from the in ...

second class

* War Merit Cross second and first class with swords

*German Cross in silver (1945)

*Grand Cross of the Order pro Merito Melitensi of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta (1948)

*Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (1968)

*Good Conduct Medal (United States)

Criticism

Several publications have criticized the fact that Gehlen allowed former Nazis to work for the agencies. The authors of the book ''A Nazi Past: Recasting German Identity in Postwar Europe'' (2015) stated that Reinhard Gehlen simply did not want to know the backgrounds of the men whom the BND hired in the 1950s. The American National Security Archive states that "he employed numerous former Nazis and known war criminals". An article in ''The Independent'' on 29 June 2018 made this statement about BND employees:"Operating until 1956, when it was superseded by the BND, the Gehlen Organization was allowed to employ at least 100 former Gestapo or SS officers.... Among them were Adolf Eichmann’s deputy Alois Brunner, who would go on to die of old age despite having sent more than 100,000 Jews to ghettos or internment camps, and ex-SS major Emil Augsburg.... Many ex-Nazi functionaries including Karl Silberbauer, Silberbauer, the captor of Anne Frank, transferred over from the Gehlen Organization to the BND.... Instead of expelling them, the BND even seems to have been willing to recruit more of them – at least for a few years".On the other hand, Gehlen himself was cleared by the CIA's James H. Critchfield, who worked with the Gehlen Organization from 1949 to 1956. In 2001, he said that "almost everything negative that has been written about Gehlen, [as an] ardent ex-Nazi, one of Hitler's war criminals ... is all far from the fact," as quoted in the ''Washington Post''. Critchfield added that Gehlen hired the former Sicherheitsdienst (Security Service of the Reichsführer-SS) men "reluctantly, under pressure from German Chancellor

Konrad Adenauer

Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer (5 January 1876 – 19 April 1967) was a German statesman and politician who served as the first Chancellor of Germany, chancellor of West Germany from 1949 to 1963. From 1946 to 1966, he was the first leader of th ...

to deal with 'the avalanche of subversion hitting them from East Germany'".

Legacy

Gehlen's memoirs were published in 1977 by World Publishers, New York. In the same year another book was published about him, ''The General Was a Spy,'' by Heinz Hoehne and Herman Zolling, Coward, McCann and Geoghegan, New York. A review of the latter, published by the CIA in 1996, calls it a "poor book" and goes on to allege that "so much of it is sheer garbage" because of many errors. The CIA review also discusses another book, ''Gehlen, Spy of the Century'', by E. H. Cookridge, Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1971, and claims that it is "chock full of errors". The CIA review is kinder when speaking of Gehlen's memoirs but makes this comment:"Gehlen's descriptions of most of his so-called successes in the political intelligence field are, in my opinion, either wishful thinking or self-delusion.... Gehlen was never a good clandestine operator, nor was he a particularly good administrator. And therein lay his failures. The Gehlen Organization/BND always had a good record in the collection of military and economic intelligence on East Germany and the Soviet forces there. But this information, for the most part, came from observation and not from clandestine penetration".Upon Gehlen's retirement in 1968, a CIA note on Gehlen describes him as "essentially a military officer in habits and attitudes". He was also characterized as "essentially a conservative", who refrained from entertaining and drinking, was fluent in English, and was at ease among senior American officials.

In popular culture

In the 2023 political thriller TV series ''Bonn (TV series), Bonn'' (German: ''Bonn – Alte Freunde, neue Feinde''), set in Germany in 1954 and aired in Das Erste, Gehlen is played by Martin Wuttke.References

Bibliography and sources

* * Cookridge, E. H. (1971). ''Gehlen: Spy of the Century''. London: Hodder & Stoughton; New York: Random House (1972). * James H. Critchfield, Critchfield, James H. (2003). ''Partners at Creation: The Men Behind Postwar Germany's Defense and Intelligence Establishments''. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. . * * Burton Hersh, Hersh, Burton (1992). ''The Old Boys: The American Elite and the Origins of the CIA''. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, Scribner's. * * Kross, Peter. "Intelligence" in ''Military Heritage'', October 2004, pp. 26–30 * Carl Oglesby, Oglesby, Carl (Fall 1990)"The Secret Treaty of Fort Hunt."

''CovertAction Information Bulletin''. * Reese, Mary Ellen. ''General Reinhard Gehlen: The CIA Connection''. Fairfax, Vir.: George Mason University. 1990 * United States National Archives, Washington, D.C. NARA Collection of Foreign Records Seized, Microfilm T-77, T-78 * Tim Weiner, Weiner, Tim (2008). ''Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA''. Anchor Books, pp. 10–190. . *

Literature

* John Douglas-Gray in his thriller ''The Novak Legacy'' * WEB Griffin, in his post-World War II novel ''Top Secret'' * Charles Whiting, ''Germany's Master Spy'' (1972)External links

"Disclosure" newsletter, Information promulgated by the U.S. National Archives & Records Administration

CIA declassified documents on the Gehlen Organization. * iarchive:GehlenReinhard, Reinhard Gehlen's CIA file on the Internet Archive. {{DEFAULTSORT:Gehlen, Reinhard 1902 births 1979 deaths Cold War history of Germany Cold War spymasters German anti-communists German Army generals of World War II German people of Flemish descent Grand Crosses with Star and Sash of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Lieutenant generals of the German Army Major generals of the German Army (Wehrmacht) Military personnel from Erfurt Military personnel from the Province of Saxony People of the Federal Intelligence Service Recipients of the Iron Cross (1939), 2nd class Recipients of the War Merit Cross Spies for the Federal Republic of Germany Spymasters World War II spies for Germany