Reid Hall on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Reid Hall is a complex of academic facilities owned and operated by

Reid Hall is a complex of academic facilities owned and operated by

By 1893, The Keller Institute was forced to close its doors, and the complex was purchased by the

By 1893, The Keller Institute was forced to close its doors, and the complex was purchased by the

"The American Girls' Club in Paris: The Propriety and Imprudence of Art Students, 1890-1914" Vol. 26, No. 1 (Spring - Summer, 2005), pp. 32-37

Official Reid Hall websiteColumbia Programs websiteReid Hall Website at Columbia's Website

{{Coord, 48.8419, 2.3317, type:landmark_region:FR, display=title Office buildings in Paris Columbia University campus Buildings and structures in the 6th arrondissement of Paris

Reid Hall is a complex of academic facilities owned and operated by

Reid Hall is a complex of academic facilities owned and operated by Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

that is located in the Montparnasse

Montparnasse () is an area in the south of Paris, France, on the left bank of the river Seine, centred at the crossroads of the Boulevard du Montparnasse and the Rue de Rennes, between the Rue de Rennes and boulevard Raspail. It is split betwee ...

quartier of Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

. It houses the Columbia University Institute for Scholars in addition to various graduate and undergraduate divisions of over a dozen Anglophone college

A college (Latin: ''collegium'') may be a tertiary educational institution (sometimes awarding degrees), part of a collegiate university, an institution offering vocational education, a further education institution, or a secondary sc ...

s and universities

A university () is an educational institution, institution of tertiary education and research which awards academic degrees in several Discipline (academia), academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase , which roughly ...

. For over a century, Reid Hall has served as a link between the academic communities of the United States and France.

In 1964, the property was bequeathed to Columbia University, and has since seen lectures by such notable French intellectuals as structuralist

Structuralism is an intellectual current and methodological approach, primarily in the social sciences, that interprets elements of human culture by way of their relationship to a broader system. It works to uncover the structural patterns tha ...

critic Roland Barthes

Roland Gérard Barthes (; ; 12 November 1915 – 25 March 1980) was a French literary theorist, essayist, philosopher, critic, and semiotician. His work engaged in the analysis of a variety of sign systems, mainly derived from Western popu ...

, deconstructionalist philosopher Jacques Derrida

Jacques Derrida (; ; born Jackie Élie Derrida;Peeters (2013), pp. 12–13. See also 15 July 1930 – 9 October 2004) was a French Algerian philosopher. He developed the philosophy of deconstruction, which he utilized in a number of his texts, ...

, existentialist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir

Simone Lucie Ernestine Marie Bertrand de Beauvoir (, ; ; 9 January 1908 – 14 April 1986) was a French existentialist philosopher, writer, social theorist, and feminist activist. Though she did not consider herself a philosopher, nor was she ...

, cinema critic Michel Ciment, and Edwy Plenel

Hervé Edwy Plenel (; born 31 August 1952) is a French far-left political journalist.

Biography

Early life

Plenel spent his childhood in Martinique and his youth in Algiers, Algeria. He studied at the Institut d'Études Politiques de Paris.

Ca ...

, former editor-in-chief of ''Le Monde

(; ) is a mass media in France, French daily afternoon list of newspapers in France, newspaper. It is the main publication of Le Monde Group and reported an average print circulation, circulation of 480,000 copies per issue in 2022, including ...

''. In addition to Columbia University, it currently houses undergraduate and graduate divisions of over a dozen institutions, including:

* American Graduate School in Paris

* Barnard College

Barnard College is a Private college, private Women's colleges in the United States, women's Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college affiliated with Columbia University in New York City. It was founded in 1889 by a grou ...

* City University of New York

The City University of New York (CUNY, pronounced , ) is the Public university, public university system of Education in New York City, New York City. It is the largest urban university system in the United States, comprising 25 campuses: eleven ...

* Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College ( ) is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Hanover, New Hampshire, United States. Established in 1769 by Eleazar Wheelock, Dartmouth is one of the nine colonial colleges chartered before the America ...

* Hamilton College

Hamilton College is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Clinton, Oneida County, New York, Clinton, New York. It was established as the Hamilton-Oneida Academy in 1793 and received its c ...

* Sarah Lawrence College

Sarah Lawrence College (SLC) is a Private university, private liberal arts college in Yonkers, New York, United States. Founded as a Women's colleges in the United States, women's college in 1926, Sarah Lawrence College has been coeducational ...

* Smith College

Smith College is a Private university, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts Women's colleges in the United States, women's college in Northampton, Massachusetts, United States. It was chartered in 1871 by Sophia Smit ...

* Tulane University

The Tulane University of Louisiana (commonly referred to as Tulane University) is a private research university in New Orleans, Louisiana, United States. Founded as the Medical College of Louisiana in 1834 by a cohort of medical doctors, it b ...

* The University of Delaware

The University of Delaware (colloquially known as UD, UDel, or Delaware) is a privately governed, state-assisted land-grant research university in Newark, Delaware, United States. UD offers four associate's programs, 163 bachelor's programs ...

* University of Florida

The University of Florida (Florida or UF) is a public university, public land-grant university, land-grant research university in Gainesville, Florida, United States. It is a senior member of the State University System of Florida and a preem ...

* Vassar College

Vassar College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Poughkeepsie, New York, United States. Founded in 1861 by Matthew Vassar, it was the second degree-granting institution of higher education for women in the United States. The college be ...

* Wesleyan University

Wesleyan University ( ) is a Private university, private liberal arts college, liberal arts university in Middletown, Connecticut, United States. It was founded in 1831 as a Men's colleges in the United States, men's college under the Methodi ...

* University of Kent Paris School of Arts and Culture

Over the years, Reid Hall has also hosted lectures and events featuring some of the most prominent French intellectuals. Among them are:

* Roland Barthes

Roland Gérard Barthes (; ; 12 November 1915 – 25 March 1980) was a French literary theorist, essayist, philosopher, critic, and semiotician. His work engaged in the analysis of a variety of sign systems, mainly derived from Western popu ...

: A renowned structuralist

Structuralism is an intellectual current and methodological approach, primarily in the social sciences, that interprets elements of human culture by way of their relationship to a broader system. It works to uncover the structural patterns tha ...

critic and semiotician

Semiotics ( ) is the systematic study of sign processes and the communication of meaning. In semiotics, a sign is defined as anything that communicates intentional and unintentional meaning or feelings to the sign's interpreter.

Semiosis is an ...

, Barthes is best known for his works such as “Mythologies” and "The Death of the Author". His lectures at Reid Hall delved into the intricacies of language, literature, and cultural symbols.

* Jacques Derrida

Jacques Derrida (; ; born Jackie Élie Derrida;Peeters (2013), pp. 12–13. See also 15 July 1930 – 9 October 2004) was a French Algerian philosopher. He developed the philosophy of deconstruction, which he utilized in a number of his texts, ...

: The father of deconstruction

In philosophy, deconstruction is a loosely-defined set of approaches to understand the relationship between text and meaning. The concept of deconstruction was introduced by the philosopher Jacques Derrida, who described it as a turn away from ...

, Derrida’s philosophy challenged traditional notions of meaning and interpretation. His influential works include “Of Grammatology” and "Writing and Difference". Derrida’s presence at Reid Hall brought profound insights into the nature of texts and the act of reading.

* Simone de Beauvoir

Simone Lucie Ernestine Marie Bertrand de Beauvoir (, ; ; 9 January 1908 – 14 April 1986) was a French existentialist philosopher, writer, social theorist, and feminist activist. Though she did not consider herself a philosopher, nor was she ...

: A leading existentialist

Existentialism is a family of philosophical views and inquiry that explore the human individual's struggle to lead an authentic life despite the apparent absurdity or incomprehensibility of existence. In examining meaning, purpose, and value ...

philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

and feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

, de Beauvoir’s seminal work “The Second Sex” remains a cornerstone of feminist theory. Her lectures at Reid Hall explored themes of existentialism, ethics, and gender.

* Michel Ciment: A distinguished cinema critic and editor of the magazine “Positif,” Ciment’s contributions to film criticism are widely recognized. His sessions at Reid Hall often focused on the analysis of cinematic art and its cultural impact.

* Edwy Plenel

Hervé Edwy Plenel (; born 31 August 1952) is a French far-left political journalist.

Biography

Early life

Plenel spent his childhood in Martinique and his youth in Algiers, Algeria. He studied at the Institut d'Études Politiques de Paris.

Ca ...

: Former editor-in-chief

An editor-in-chief (EIC), also known as lead editor or chief editor, is a publication's editorial leader who has final responsibility for its operations and policies. The editor-in-chief heads all departments of the organization and is held accoun ...

of “Le Monde” and co-founder of the investigative journal “Mediapart,” Plenel is a prominent figure in French journalism

Journalism is the production and distribution of reports on the interaction of events, facts, ideas, and people that are the "news of the day" and that informs society to at least some degree of accuracy. The word, a noun, applies to the journ ...

. His talks at Reid Hall addressed issues of media, politics, and social justice.

Reid Hall continues to serve as a vibrant center for academic and cultural activities, fostering dialogue and collaboration among scholars, students, and intellectuals from around the world.

History

Porcelain factory

Reid Hall's origins date to the mid-eighteenth century, when it served as aporcelain

Porcelain (), also called china, is a ceramic material made by heating Industrial mineral, raw materials, generally including kaolinite, in a kiln to temperatures between . The greater strength and translucence of porcelain, relative to oth ...

factory

A factory, manufacturing plant or production plant is an industrial facility, often a complex consisting of several buildings filled with machinery, where workers manufacture items or operate machines which process each item into another. Th ...

and warehouse. By 1799, the building was purchased by two French brothers by the name of Dagoty, who succeeded in converting the building to one of the largest and most successful porcelain factories in France. By 1812, the Dagoty brothers had over a hundred workers in their employ and built an additional three warehouses and four storerooms, one of which was richly ornamented with mirrors and decorative shelves. Their porcelain was not only popular in the dining rooms of the local bourgeoisie, but was also purchased for such residences as the castle of Compiègne

Compiègne (; ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Oise Departments of France, department of northern France. It is located on the river Oise (river), Oise, and its inhabitants are called ''Compiégnois'' ().

Administration

Compiègne is t ...

, the palace of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines, Yvelines Department of Île-de-France, Île-de-France region in Franc ...

, and the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American Founding Father of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. He was the last Founding Father to serve as presiden ...

, who was then the President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

, commissioned a Dagoty china

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

service featuring an American eagle

Eagle is the common name for the golden eagle, bald eagle, and other birds of prey in the family of the Accipitridae. Eagles belong to several groups of Genus, genera, some of which are closely related. True eagles comprise the genus ''Aquila ( ...

motif for use at official state dinners.

Keller Institute

In 1834, the site became the home of the Keller Institute, a boarding school led by aSwiss

Swiss most commonly refers to:

* the adjectival form of Switzerland

* Swiss people

Swiss may also refer to: Places

* Swiss, Missouri

* Swiss, North Carolina

* Swiss, West Virginia

* Swiss, Wisconsin

Other uses

* Swiss Café, an old café located ...

Protestant Educator Jean-Jacques Keller. It was the first Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

school established in France since the revocation of the Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was an edict signed in April 1598 by Henry IV of France, King Henry IV and granted the minority Calvinism, Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was predominantl ...

in 1685, whose student body came from the home of bourgeois Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

, or French Protestants, and wealthy expatriate

An expatriate (often shortened to expat) is a person who resides outside their native country.

The term often refers to a professional, skilled worker, or student from an affluent country. However, it may also refer to retirees, artists and ...

s. Students included André Gide

André Paul Guillaume Gide (; 22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951) was a French writer and author whose writings spanned a wide variety of styles and topics. He was awarded the 1947 Nobel Prize in Literature. Gide's career ranged from his begi ...

, who attended the Institute in 1886, an experience that he later described in his writings.

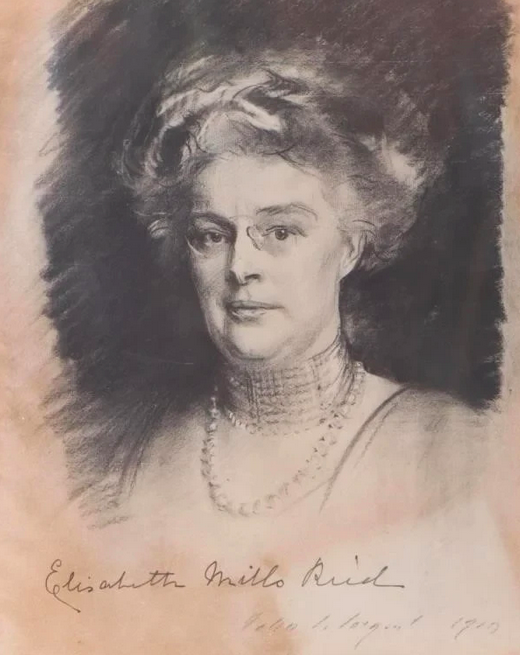

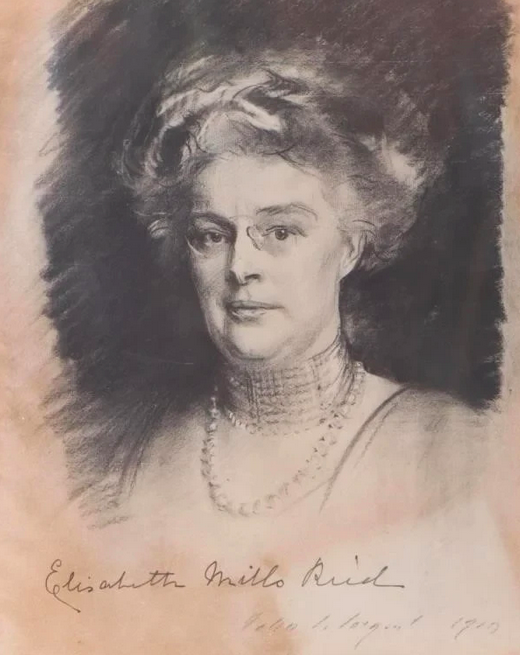

Elizabeth Mills Reid

By 1893, The Keller Institute was forced to close its doors, and the complex was purchased by the

By 1893, The Keller Institute was forced to close its doors, and the complex was purchased by the philanthropist

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives for the public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private good, focusing on material ...

and social activist Elizabeth Mills Reid, whose father, Darius O. Mills, had been president of the Bank of California

The Bank of California was opened in San Francisco, California, on July 4, 1864, by William Chapman Ralston and Darius Ogden Mills. It was the first commercial bank in the Western United States, and considered instrumental in developing the Amer ...

, and whose husband was the American plenipotentiary

A ''plenipotentiary'' (from the Latin ''plenus'' "full" and ''potens'' "powerful") is a diplomat who has full powers—authorization to sign a treaty or convention on behalf of a sovereign. When used as a noun more generally, the word can als ...

minister to Paris, Whitelaw Reid

Whitelaw Reid (October 27, 1837 – December 15, 1912) was an American politician, diplomat and newspaper editor, as well as the author of ''Ohio in the War'', a popular work of history.

After assisting Horace Greeley as editor of the ''New-Yo ...

. Mrs. Reid then established the American Girls' Club in Paris in hopes of providing artistic and academic opportunities to young American women living in Paris. The success of the club allowed Reid to expand the complex to include a neighboring building and its courtyard.Mariea Caudill Dennison, Woman's Art Journal"The American Girls' Club in Paris: The Propriety and Imprudence of Art Students, 1890-1914" Vol. 26, No. 1 (Spring - Summer, 2005), pp. 32-37

World War I hospital

At the outbreak ofWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the property was converted into a hospital, and its classrooms were used to house wounded soldiers. The complex saw a number of new buildings constructed at this time to provide more adequated facilities for the enormous number of casualties

A casualty (), as a term in military usage, is a person in military service, combatant or non-combatant, who becomes unavailable for duty due to any of several circumstances, including death, injury, illness, missing, capture or desertion.

In c ...

being cared for by the American Red Cross

The American National Red Cross is a Nonprofit organization, nonprofit Humanitarianism, humanitarian organization that provides emergency assistance, disaster relief, and disaster preparedness education in the United States. Clara Barton founded ...

. After the war's end, the site remained in the hands of the American Red Cross until 1922.

Academic rebirth

In 1922, Reid began converting the complex to house a center for advanced and university studies for American women. Reid Hall became important to American women's academics inWestern Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

, and grew along with Franco-American artistic activity in the Montparnasse quarter during the inter-war period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

, with visits and lectures being provided by influential neighbors including Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein (February 3, 1874 – July 27, 1946) was an American novelist, poet, playwright, and art collector. Born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania (now part of Pittsburgh), and raised in Oakland, California, Stein moved to Paris in 1903, and ...

and Nadia Boulanger

Juliette Nadia Boulanger (; 16 September 188722 October 1979) was a French music teacher, conductor and composer. She taught many of the leading composers and musicians of the 20th century, and also performed occasionally as a pianist and organis ...

. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Reid Hall became a refuge, first for Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Polish people, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

* Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin ...

university women, then for Belgian teachers, and later for the women students of the Ecole Normale Superieure de Sèvres. After the war, the property was converted once again to a university center, this time with a coeducational

Mixed-sex education, also known as mixed-gender education, co-education, or coeducation (abbreviated to co-ed or coed), is a system of education where males and females are educated together. Whereas single-sex education was more common up to ...

student body. The Sweet Briar College Junior Year in France and others were based at Reid Hall. Elizabeth Mill Reid's daughter in law (and former social secretary) Helen Rogers Reid continued to own the property but in 1964 she gave the property to Columbia University. In September 2018, Reid Hall welcomed the Institute for Ideas and Imagination, an initiative launched by Columbia's President, Lee Bollinger

Lee Carroll Bollinger (born April 30, 1946) is an American attorney and educator who served as the 19th president of Columbia University from 2002 to 2023 and as the 12th president of the University of Michigan from 1996 to 2002.

Bollinger is c ...

. The combination of the Center and the Institute, bring to Reid Hall the significant resources provided by Columbia faculty, students, and administration.

References

External links

Official Reid Hall website

{{Coord, 48.8419, 2.3317, type:landmark_region:FR, display=title Office buildings in Paris Columbia University campus Buildings and structures in the 6th arrondissement of Paris