Reginald John Pinney on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Major-General Sir Reginald John Pinney (2 August 1863 − 18 February 1943) was a

Reginald John Pinney was born on 2 August 1863 in

Reginald John Pinney was born on 2 August 1863 in

British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

officer who served as a brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military unit, military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute ...

and divisional commander on the Western Front during the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. While commanding a division at the Battle of Arras in 1917, he was immortalised as the "cheery old card" of Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Loraine Sassoon (8 September 1886 – 1 September 1967) was an English war poet, writer, and soldier. Decorated for bravery on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front, he became one of the leading poets of the First World ...

's poem " The General".

Pinney served in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

during the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

with the Royal Fusiliers

The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army in continuous existence for 283 years. It was known as the 7th Regiment of Foot until the Childers Reforms of 1881.

The regiment served in many war ...

, into which he had been commissioned in 1884, and at the outbreak of the First World War was given command of an infantry brigade sent to reinforce the Western Front in November 1914. He led it in the early part of 1915, taking heavy losses at the Battle of Neuve Chapelle

The Battle of Neuve Chapelle (10–13 March 1915) took place in the First World War in the Artois region of France. The attack was intended to cause a rupture in the German lines, which would then be exploited with a rush to the Aubers Ridge an ...

. That September he was given command of the 35th Division, a New Army division of " bantam" soldiers, which first saw action the following year at the Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme (; ), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and the French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place between 1 July and 18 Nove ...

; after three months in action, he was exchanged with the commander of the 33rd Division. He commanded the 33rd at Arras in 1917, with mixed results, and through the German spring offensive

The German spring offensive, also known as ''Kaiserschlacht'' ("Kaiser's Battle") or the Ludendorff offensive, was a series of German Empire, German attacks along the Western Front (World War I), Western Front during the World War I, First Wor ...

in 1918, where the division helped stabilise the defensive line after the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps

The Portuguese Expeditionary Corps (CEP, Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''Corpo Expedicionário Português'') was the main expeditionary force from Portugal that fought in the Western Front (World War I), Western Front, during World War I. Port ...

(CEP) was routed.

After the war, he retired to rural Dorset

Dorset ( ; Archaism, archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Somerset to the north-west, Wiltshire to the north and the north-east, Hampshire to the east, t ...

, where he served as a local justice of the peace, as High Sheriff for the county, and as a deputy lieutenant, before his death in 1943.

Early life and military career

Reginald John Pinney was born on 2 August 1863 in

Reginald John Pinney was born on 2 August 1863 in Clifton, Bristol

Clifton is an inner suburb of Bristol, England, and the name of one of the city's thirty-five Wards and electoral divisions of the United Kingdom, electoral wards. The Clifton ward also includes the areas of Cliftonwood and Hotwells. The easter ...

, the eldest son of the Reverend John Pinney, vicar of Coleshill, Warwickshire

Coleshill ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the North Warwickshire district of Warwickshire, England, taking its name from the River Cole, on which it stands. It had a population of 6,900 in the 2021 Census, and is situated east of Bi ...

, and his wife, Harriet. His paternal grandfather was Charles Pinney

Charles Pinney (29 April 179317 July 1867) was a British merchant and local politician in Bristol, England. He was a partner in a family business that ran sugar plantations in the West Indies and owned a number of slaves. Pinney was selected as m ...

, a prominent merchant and former mayor of Bristol,Foot (2006) whilst his maternal grandfather, John Wingfield-Digby, was a previous vicar of Coleshill;''Who Was Who'' an uncle, John Wingfield-Digby, would later be the Conservative MP for North Dorset

North Dorset was a local government district in Dorset, England, between 1974 and 2019. Its area was largely rural, but included the towns of Blandford Forum, Gillingham, Shaftesbury, Stalbridge and Sturminster Newton. Much of North Dorset wa ...

. John and Harriet Pinney had five more children, four sons and a daughter, before Harriet's death in 1877. At least one of Reginald's brothers, John, also passed into the armed forces

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a ...

, joining the Central India Horse

The Central India Horse (formerly the 21st King George V's Own Horse, also known as Beatson's Horse) was a regular cavalry regiment of the British Indian Army and is presently part of the Indian Army Armoured Corps.

Formation

The regiment was r ...

of the British Indian Army

The Indian Army was the force of British Raj, British India, until Indian Independence Act 1947, national independence in 1947. Formed in 1895 by uniting the three Presidency armies, it was responsible for the defence of both British India and ...

.

After four years at Winchester College

Winchester College is an English Public school (United Kingdom), public school (a long-established fee-charging boarding school for pupils aged 13–18) with some provision for day school, day attendees, in Winchester, Hampshire, England. It wa ...

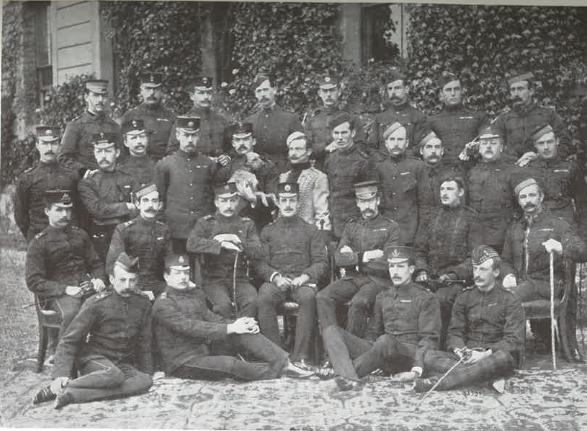

, Pinney entered the Royal Military College at Sandhurst in 1882. He passed out of the college and was appointed to the Royal Fusiliers

The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army in continuous existence for 283 years. It was known as the 7th Regiment of Foot until the Childers Reforms of 1881.

The regiment served in many war ...

(7th Foot), one of the oldest regiments in the British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

, as a lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

on 6 February 1884. He spent five years with his regiment before attending the Staff College, Camberley

Staff College, Camberley, Surrey, was a staff college for the British Army and the presidency armies of British India (later merged to form the Indian Army). It had its origins in the Royal Military College, High Wycombe, founded in 1799, which ...

from 1889 to 1890; after leaving Camberley, he was promoted to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

in December 1891. From 1896 to 1901 he served on the staff as the deputy assistant adjutant-general (DAAG) at Quetta

Quetta is the capital and largest city of the Pakistani province of Balochistan. It is the ninth largest city in Pakistan, with an estimated population of over 1.6 million in 2024. It is situated in the south-west of the country, lying in a ...

, in India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, with a promotion to major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

in December 1898. He married Hester Head in 1900; the couple had three sons and three daughters.

Pinney saw active service in the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

, arriving in South Africa in November 1901 to become second-in-command

Second-in-command (2i/c or 2IC) is a title denoting that the holder of the title is the second-highest authority within a certain organisation.

Usage

In the British Army or Royal Marines, the second-in-command is the deputy commander of a unit, f ...

of the 2nd Battalion, Royal Fusiliers (which had been there since the outbreak of the war in late 1899). He served with the battalion until the end of the war, which ended with the Peace of Vereeniging

The Treaty of Vereeniging was a peace treaty, signed on 31 May 1902, that ended the Second Boer War between the South African Republic and the Orange Free State on the one side, and the United Kingdom on the other.

This settlement provided ...

in June 1902. Four months later he left Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

on the SS ''Salamis'' with other officers and men of the battalion, arriving at Southampton

Southampton is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. It is located approximately southwest of London, west of Portsmouth, and southeast of Salisbury. Southampton had a population of 253, ...

in late October, when the battalion was posted to Aldershot

Aldershot ( ) is a town in the Rushmoor district, Hampshire, England. It lies on heathland in the extreme north-east corner of the county, south-west of London. The town has a population of 37,131, while the Farnborough/Aldershot built-up are ...

.

After his return he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and became commanding officer

The commanding officer (CO) or commander, or sometimes, if the incumbent is a general officer, commanding general (CG), is the officer in command of a military unit. The commanding officer has ultimate authority over the unit, and is usually give ...

(CO) of the 4th Battalion of his regiment, with a brevet promotion

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

to colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

in May 1906. He relinquished command of the battalion in May 1907 and then went on half-pay

Half-pay (h.p.) was a term used in the British Army and Royal Navy of the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries to refer to the pay or allowance an officer received when in retirement or not in actual service.

Past usage United Kingdom

In the E ...

, receiving a promotion to full colonel that November. He later took up the position of assistant adjutant general (AAG) in Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

in September 1909, taking over from Gerald Cuthbert

Major general (United Kingdom), Major General Gerald James Cuthbert, (12 September 1861 – 1 February 1931) was a British Army officer who commanded a battalion in the Second Boer War and a division in the First World War. Cuthbert joined ...

.

He held this posting until July 1913 when he was transferred back to England to command a reserve unit, the Devon and Cornwall Brigade of the Wessex Division

The 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division was an infantry division of Britain's Territorial Army (TA). The division was first formed in 1908, as the Wessex Division. During the First World War, it was broken-up and never served as a complete formati ...

, a formation of the part time Territorial Force

The Territorial Force was a part-time volunteer component of the British Army, created in 1908 to augment British land forces without resorting to conscription. The new organisation consolidated the 19th-century Volunteer Force and yeomanry in ...

(TF).

First World War

Brigade commander in France

Following the outbreak of theFirst World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in August 1914, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) of seven Regular Army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the following:

* a ...

divisions was mobilised for service in France. At the same time, the TF was activated to replace them for home defence duties. The BEF represented almost all the Regular units stationed in the United Kingdom, but only about half the strength of the Regular Army; the remainder was scattered in various stations around the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

, mainly in India and the Mediterranean. These units were withdrawn as quickly as they could be replaced by Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Associated with India

* of or related to India

** Indian people

** Indian diaspora

** Languages of India

** Indian English, a dialect of the English language

** Indian cuisine

Associated with indigenous peoples o ...

or Territorial units, and formed into new divisions to reinforce the BEF.

The Wessex Division—now numbered as the 43rd—had been assigned for duty in India to free up Regular units there, with its staff and support units held back to form the framework of the new 8th Division, which was formed from returning Regular battalions. As a result, Pinney, promoted in August to the temporary rank of brigadier general, was relieved from command of his Territorial brigade in October and assigned to command the newly formed 23rd Infantry Brigade, made up from three battalions that had been on garrison duty in Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

and one from Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

. The four battalions of Pinney's 23rd Brigade were the 2nd Cameronians, 2nd Devonshires, 2nd Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a Historic counties of England, former county in South East England, now mainly within Greater London. Its boundaries largely followed three rivers: the River Thames, Thames in the south, the River Lea, Le ...

and 2nd West Yorkshires; all from Malta bar the Devonshires in Egypt. All were Regular units, with very few reservists, but, having spent a long period in colonial stations, they were considered as only partially trained compared to the units serving with the BEF.

The 8th Division, under the command of Major-General Francis Davies, was sent to France in November; immediately after arrival, two battalions were deployed to hold a section of the front line for a week during the closing stages of the First Battle of Ypres

The First Battle of Ypres (, , – was a battle of the First World War, fought on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front around Ypres, in West Flanders, Belgium. The battle was part of the First Battle of Flanders, in which German A ...

. However, the brigade did not see its first major action under Pinney's command until 10 March 1915, when it was committed to action as part of the Battle of Neuve Chapelle

The Battle of Neuve Chapelle (10–13 March 1915) took place in the First World War in the Artois region of France. The attack was intended to cause a rupture in the German lines, which would then be exploited with a rush to the Aubers Ridge an ...

. Pinney's 23rd Brigade met heavy resistance when it began its attack, due to a failure by the divisional artillery to bombard a large section of the defenders' trenches; the 2nd Middlesex, making a frontal assault

A frontal assault is a military tactic which involves a direct, full-force attack on the front line of an enemy force, rather than to the flanks or rear of the enemy. It allows for a quick and decisive victory, but at the cost of subjecting the a ...

, were wiped out almost completely. The other lead battalion of the brigade, the 2nd Cameronians, was enfiladed from the undamaged sector and took heavy losses, losing almost all its officers and retreating in confusion. Pinney quickly learned of this—he was only two hundred yards from the front line—and decided to continue the attack. As he was not able to call for artillery support, the only possible approach was to send in the two reserve battalions. The second assault suffered heavy casualties at the outset, and quickly had to be called off when it was discovered that the corps artillery was about to fire on the positions being attacked; the Devonshires and West Yorkshires were withdrawn, having taken high casualties and achieved little. After this, the attack continued to bog down, and whilst there was some success elsewhere in the divisional sector, nothing more was achieved by 23rd Brigade. Following Neuve Chapelle, the brigade was reinforced with two battalions of the TF, the 1st/6th Cameronians and the 1st/7th Middlesex. At the Battle of Aubers

The Battle of Aubers (Battle of Aubers Ridge) was a British offensive on the Western Front on 9 May 1915 during the First World War. The battle was part of the British contribution to the Second Battle of Artois, a Franco-British offensive int ...

on 9 May, 23rd Brigade was held in reserve by 8th Division and so escaped the heavy casualties of the two attacking brigades. Around noon a scratch force of all available infantry was pushed forward by the divisional commander to support these two brigades, including some units of Pinney's brigade.

Divisional command

Pinney relinquished command of the brigade toTravers Clarke

Lieutenant General Sir Travers Edwards Clarke (6 April 1871 – 2 February 1962) was a British Army officer who served in the Second Boer War and the First World War. During the First World War, he held various staff positions; he was Quartermast ...

in late June, when he was promoted to major-general and returned to England to become general officer commanding

General officer commanding (GOC) is the usual title given in the armies of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth (and some other nations, such as Ireland) to a general officer who holds a command appointment.

Thus, a general might be the GOC ...

(GOC) of the newly formed 35th Division, a New Army volunteer division. The division was mainly drawn from industrial areas of Northern England

Northern England, or the North of England, refers to the northern part of England and mainly corresponds to the Historic counties of England, historic counties of Cheshire, Cumberland, County Durham, Durham, Lancashire, Northumberland, Westmo ...

, with a high proportion of " bantams", men who were under the normal regulation height of 5 ft 3 in (160 cm) for army service. Among the officers Pinney first encountered in the 35th was Captain Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence and the ...

, recently posted as brigade major

A brigade major was the chief of staff of a brigade in the British Army. They most commonly held the rank of major, although the appointment was also held by captains, and was head of the brigade's "G - Operations and Intelligence" section direct ...

of the 104th Infantry Brigade, who would later serve under him as the general staff officer, grade 2 (GSO2) in the 33rd Division.

The division was transferred to France in early 1916, in preparation for the summer offensive of that year. It moved into the line in February, and Pinney ordered a series of small raids in company or battalion strength through the following months. The 35th was deployed for the Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme (; ), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and the French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place between 1 July and 18 Nove ...

, assigned to XIII Corps in Fourth Army. It was held in reserve during the Battle of Albert, the opening phases of the attack in early July, but fought in the Battle of Bazentin Ridge

The Battle of Bazentin Ridge was part of the Battle of the Somme on the Western Front in France, during the First World War. On 14 July, the British Fourth Army (General Henry Rawlinson) made a dawn attack against the German 2nd Army (Gene ...

and the subsequent attacks on High Wood

The Attacks on High Wood, near Bazentin le Petit in the Somme ''département'' of northern France, took place between the British Fourth Army and the German 1st Army during the Battle of the Somme. After the Battle of Bazentin Ridge on 14 Ju ...

, where it took heavy casualties; in a week, one brigade lost a thousand men, a third of its strength. The division rested for a week in early August, but returned to the line almost immediately. At the end of the month, a badly planned and potentially suicidal attack on Falfemont Farm was cancelled by Pinney at the last minute when the "facts were pointed out" by Montgomery, and a new plan substituted; the attacking battalion took the farm with light casualties. Following this, it was withdrawn to a quiet sector of the line.

In September, Major-General Herman Landon, GOC of the neighbouring 33rd Division was relieved of his command. It was arranged that he would exchange with Pinney in the 35th Division, and the transfer was made on 23 September. The decision to rotate commanders appears to have been a desire to give Landon, four years older than Pinney, a less active command, as the 35th was occupying a relatively quiet sector; presumably, it was felt that Pinney was a more effective commander for an active division. When Pinney met the officers of one of his new battalions in early October 1916, they recorded that he seemed "pleasant and human", and "not too old".

However, some of his habits were unpopular; most gallingly to his men, he stopped the regular issue of rum in the division shortly after taking command, replacing it with tea instead. The infantry were greatly displeased, with one NCO describing him as "a bun-pinching crank, more suited to command of a Church Mission hut than troops". There was some justification to the jibe; as well as being teetotal, Pinney did not smoke, and was devoutly religious. The most lasting description of him was written in this period by Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Loraine Sassoon (8 September 1886 – 1 September 1967) was an English war poet, writer, and soldier. Decorated for bravery on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front, he became one of the leading poets of the First World ...

, then an officer in one of the 33rd's battalions, who used Pinney as the subject of his satirical poem " The General".

The 33rd was a New Army division of the same wave as the 35th, but it had lost its original New Army composition; by late 1916, it was composed equally of Territorial, Regular and New Army battalions. Rather than the 35th's bantams, the 33rd had originally been formed from "Pals battalion

The pals battalions of World War I were specially constituted battalions of the British Army comprising men who enlisted together in local recruiting drives, with the promise that they would be able to serve alongside their friends, neighbours an ...

s", units drawn from local communities so that men could serve alongside their friends and colleagues, and the Public Schools Battalions

The Public Schools Battalions were a group of Pals battalions of the British Army during World War I. They were raised in 1914 as part of Kitchener's Army and were originally recruited exclusively from former public schoolboys. When the battalions ...

, made up of former pupils of the elite public schools

Public school may refer to:

*Public school (government-funded), a no-fee school, publicly funded and operated by the government

*Public school (United Kingdom), certain elite fee-charging private schools in England and Wales

*Great Public Schools, ...

. Many of the initial units had been transferred out—or, in the case of the latter units, disbanded so that their men could be trained as officers—but a number of these close-knit units still remained in the division.

Following Pinney's arrival the division was withdrawn for two months to reorganise, missing the Battle of Flers-Courcelette

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force c ...

, and saw some fighting in the very end of the fighting on the Somme when a "pretentious" plan produced by the divisional command to capture a German trench system at night failed. In January 1917 Pinney was awarded a Companion of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by King George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. Recipients of the Order are usually senior British Armed Forces, military officers or senior Civil Service ...

(CB). The 33rd remained on the Somme front until March, when it was transferred to Amiens to participate in the Battle of Arras. Here, the division fought at the Second Battle of the Scarpe in late April, where it took 700 prisoners

A prisoner, also known as an inmate or detainee, is a person who is deprived of liberty against their will. This can be by confinement or captivity in a prison or physical restraint. The term usually applies to one serving a sentence in priso ...

but suffered heavy losses. This was followed by a series of attacks on the Hindenburg Line

The Hindenburg Line (, Siegfried Position) was a German Defense line, defensive position built during the winter of 1916–1917 on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front in France during the First World War. The line ran from Arras to ...

in late May, the first of which, on the night of 20 May, was masterminded by PinneyObituary in ''The Times'', 20 February 1943, p. 6—one observer noted that "his tail is right up over his back ... he was out for a gamble with his troops and he had it", though sadly added that despite its great success, he still refused to authorise an issue of rum. A second attack on 27 May was a complete failure; Pinney later explained the attack as having been a distraction in support of the coming Battle of Messines, an interpretation greeted with some cynicism by observers.

Following the fighting around Arras, the 33rd was moved to Nieuwpoort, Belgium

Nieuwpoort ( , ; ; ) is a City status in Belgium, city and Municipalities of Belgium, municipality located in Flemish Region, Flanders, one of the three regions of Belgium, in the province of West Flanders. The municipality comprises the town o ...

, as part of the build-up for the planned Operation Hush

Operation Hush was a British plan for amphibious landings on the Belgian coast in 1917 during the First World War. The landings were to be combined with an attack from Nieuwpoort and the Yser bridgehead, left over since the Battle of the Yser ...

, a breakthrough

Breakthrough or break through may refer to:

Arts Books

* ''Break Through'' (book), a 2007 book about environmentalism by Ted Nordhaus and Michael Shellenberger

* ''Break Through'' (play), a 2011 episodic play portraying scenes from LGBT life

* ...

along the coastal front coupled with an amphibious landing

Amphibious warfare is a type of offensive military operation that today uses naval ships to project ground and air power onto a hostile or potentially hostile shore at a designated landing beach. Through history the operations were conducted ...

behind German lines. After the operation was cancelled, the division remained at Niewpoort, where Pinney was hospitalised and temporarily relinquished command of the 33rd to Brigadier General Philip Wood

Brigadier-General Philip Richard Wood (February 1868 – 10 October 1945) was a senior British Army officer who briefly served as General Officer Commanding 33rd Division during the First World War.

Military career

Wood was commissioned into ...

. He remained in hospital for two months, during which time he missed heavy fighting by the 33rd at the Battle of Passchendaele

The Third Battle of Ypres (; ; ), also known as the Battle of Passchendaele ( ), was a campaign of the First World War, fought by the Allies of World War I, Allies against the German Empire. The battle took place on the Western Front (World Wa ...

. After the GOC VIII Corps 8th Corps, Eighth Corps, or VIII Corps may refer to:

* VIII Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French army during the Napoleonic Wars

* VIII Army Corps (German Confederation)

* VIII Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Arm ...

, Lieutenant General Aylmer Hunter-Weston

Lieutenant General Sir Aylmer Gould Hunter-Weston, (23 September 1864 – 18 March 1940) was a British Army officer who served in the First World War on the Western Front, at Gallipoli in 1915, and in the very early stages of the Somme Offensi ...

, had sacked the current divisional commander, Brigadier General Wood, for a perceived lack of aggression (unjustifiably, in Simon Robbins' view), Pinney returned to the division on 30 November, amid rumours that he had got the return posting through personal influence.

The division remained in reserve until April 1918, when German forces attacked as part of their spring offensive. During the Battle of the Lys, the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps

The Portuguese Expeditionary Corps (CEP, Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''Corpo Expedicionário Português'') was the main expeditionary force from Portugal that fought in the Western Front (World War I), Western Front, during World War I. Port ...

(CEP) was effectively wiped out, leaving a two-mile wide gap in the British lines. The 33rd was ordered into position, and Pinney personally commanded the divisional machine-gun battalion, which—with the assistance of various stragglers from retreating units—helped turn back a heavy German attack at the Battle of Hazebrouck on 12 and 13 April. For his service in April, Pinney, along with the commanders of the 12th

Twelfth can mean:

*The Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution

*The Twelfth, a Protestant celebration originating in Ireland

In mathematics:

* 12th, an ordinal number; as in the item in an order twelve places from the beginning, follo ...

, 55th and 61st divisions, was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB). The 33rd was used to train the U.S. 30th Division through the summer, but went over to the offensive

Offensive may refer to:

* Offensive (military), type of military operation

* Offensive, the former name of the Dutch political party Socialist Alternative

* Fighting words, spoken words which would have a tendency to cause acts of violence by the ...

in September, seeing action at the Battle of the St Quentin Canal

The Battle of St Quentin Canal was a pivotal battle of World War I that began on 29 September 1918 and involved British, Australian and American forces operating as part of the British Fourth Army under the overall command of General Sir Hen ...

, the Battle of Cambrai, and the Battle of the Selle

The Battle of the Selle (17–25 October 1918) took place between Allied forces and the German Army, fought during the Hundred Days Offensive of World War I.

Prelude

After the Second Battle of Cambrai, the Allies advanced almost and liberat ...

. At the Selle, Pinney organised a dawn attack with improvised bridges, allowing the 33rd to force a bridgehead

In military strategy, a bridgehead (or bridge-head) is the strategically important area of ground around the end of a bridge or other place of possible crossing over a body of water which at time of conflict is sought to be defended or taken over ...

and successfully clear the opposing bank in a short time.

The division finished the war, which ended due to the armistice of 11 November 1918

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed in a railroad car, in the Compiègne Forest near the town of Compiègne, that ended fighting on land, at sea, and in the air in World War I between the Entente and their las ...

, in the Sambre

The Sambre () is a river in northern France and in Wallonia, Belgium. It is a left-bank tributary of the Meuse, which it joins in the Wallonian capital Namur.

The source of the Sambre is near Le Nouvion-en-Thiérache, in the Aisne department. ...

valley, and began demobilisation

Demobilization or demobilisation (see spelling differences) is the process of standing down a nation's armed forces from combat-ready status. This may be as a result of victory in war, or because a crisis has been peacefully resolved and milita ...

. In February 1919, with the division mostly demobilised, Pinney retired from the army, aged fifty-five, after thirty-five years service.

Retirement

Following the end of his career in the army, Pinney took up residence at Racedown Manor, in the village of Broadwindsor,Dorset

Dorset ( ; Archaism, archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Somerset to the north-west, Wiltshire to the north and the north-east, Hampshire to the east, t ...

, where he lived the life of a retired country gentleman. He became a justice of the peace and deputy lieutenant for the county, and served as its high sheriff in 1923. He did not return to an active army post, though he was the colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

of his old regiment, the Royal Fusiliers, from 1924 until 1933, and was honorary colonel of the Dorsetshire Coast Brigade, Royal Garrison Artillery (appointed 31 March 1921) and of the 4th (Territorial

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, belonging or connected to a particular country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually a geographic area which has not been granted the powers of self-government, ...

) Battalion of the Dorsetshire Regiment

The Dorset Regiment was a line infantry regiment of the British Army in existence from 1881 to 1958, being the county regiment of Dorset. Until 1951, it was formally called the Dorsetshire Regiment, although usually known as "The Dorsets". In 19 ...

.

Pinney died at the age of 79 on 18 February 1943, survived by his wife and five of his children. All three of his sons served in the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

; his eldest son, Bernard, was killed in action in November 1941, commanding J Battery Royal Horse Artillery at Sidi Rezegh

Operation Crusader (18 November – 30 December 1941) was a military operation of the Western Desert campaign during World War II by the British Eighth Army (United Kingdom), Eighth Army (with Commonwealth, Indian and Allied contingents) agains ...

in North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

. His daughter Rachel

Rachel () was a Bible, Biblical figure, the favorite of Jacob's two wives, and the mother of Joseph (Genesis), Joseph and Benjamin, two of the twelve progenitors of the tribes of Israel. Rachel's father was Laban (Bible), Laban. Her older siste ...

was one of a group of women who, as "Ferguson's Gang

Ferguson's Gang, formed during a picnic at Tothill Fields in London in 1927, was an anonymous and somewhat enigmatic group that raised funds for the National Trust from 1930 to 1947.

The members hid their identities behind resplendent masks, punn ...

", hit the headlines in the interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) – from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

with masked appearances with bags of money to save properties for the National Trust. A scholarship fund, to provide access to higher education for the children of Dorset ex-servicemen, was established in Pinney's name in June 1943, and remains in existence.

Notes

References

* "Pinney, Maj.-Gen. Sir Reginald (John)", in * * * * * * * * * * * , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Pinney, Reginald 1863 births 1943 deaths British Army major generals British Army personnel of the Second Boer War British Army generals of World War I Deputy lieutenants of Dorset Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst Graduates of the Staff College, Camberley High sheriffs of Dorset Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath People educated at Winchester College Royal Fusiliers officers Military personnel from Bristol