Rediscovery Of Sargon II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sargon II acceded to the throne of the

Sargon II acceded to the throne of the

Mesopotamia was long ignored by western archaeologists. Unlike other ancient civilizations, Assyria and other Mesopotamian civilizations left no magnificent ruins above ground; all that remained to see were huge grass-covered mounds in the plains which travellers at times believed to simply be natural features of the landscape. Such scant remains did not fit well with the European idea of ancient great cities, with stone columns and great sculptures like those of Greece and Persia. In the early 19th century, European explorers and archaeologists first began to investigate the ancient mounds, though early archaeologists were chiefly interested in confirming Biblical truth through their excavations rather than spending time on new interpretations of the evidence they discovered. The early excavations were in large part inspired by archaeologcial finds of the British business agent

Mesopotamia was long ignored by western archaeologists. Unlike other ancient civilizations, Assyria and other Mesopotamian civilizations left no magnificent ruins above ground; all that remained to see were huge grass-covered mounds in the plains which travellers at times believed to simply be natural features of the landscape. Such scant remains did not fit well with the European idea of ancient great cities, with stone columns and great sculptures like those of Greece and Persia. In the early 19th century, European explorers and archaeologists first began to investigate the ancient mounds, though early archaeologists were chiefly interested in confirming Biblical truth through their excavations rather than spending time on new interpretations of the evidence they discovered. The early excavations were in large part inspired by archaeologcial finds of the British business agent

Shortly after the finds at Dur-Sharrukin were publicized, the German Assyriologist Isidore Löwenstern was the first to suggest that the city had been constructed by the Sargon briefly mentioned in the Bible, though he also identified Sargon with Esarhaddon. Löwenstern's identification, published in 1845, was more of a bizarre accident than thorough scholarship. Löwenstern worked two years before cuneiform was deciphered and based his identification primarily on a relief from Dur-Sharrukin depicting a seaside city under Assyrian attack. In the inscription accompanying the relief, Löwenstern erroneously read

Shortly after the finds at Dur-Sharrukin were publicized, the German Assyriologist Isidore Löwenstern was the first to suggest that the city had been constructed by the Sargon briefly mentioned in the Bible, though he also identified Sargon with Esarhaddon. Löwenstern's identification, published in 1845, was more of a bizarre accident than thorough scholarship. Löwenstern worked two years before cuneiform was deciphered and based his identification primarily on a relief from Dur-Sharrukin depicting a seaside city under Assyrian attack. In the inscription accompanying the relief, Löwenstern erroneously read

Sargon II

Sargon II (, meaning "the faithful king" or "the legitimate king") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 722 BC to his death in battle in 705. Probably the son of Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727), Sargon is generally believed to have be ...

ruled the Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to dominate the ancient Near East and parts of South Caucasus, Nort ...

from 722 to 705 BC as one of its most successful kings. In his final military campaign, Sargon was killed in battle in the south-eastern Anatolian region Tabal and the Assyrian army was unable to retrieve his body, which meant that he could not undergo the traditional royal Assyrian burial. In ancient Mesopotamia, not being buried was believed to condemn the dead to becoming a hungry and restless ghost for eternity. As a result, the Assyrians believed that Sargon must have committed some grave sin in order to suffer this fate. His son and successor Sennacherib

Sennacherib ( or , meaning "Sin (mythology), Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 705BC until his assassination in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is one of the most famous A ...

(), convinced of Sargon's sin, consequently spent much effort to distance himself from his father and to rid the empire from his work and imagery. Sennacherib's efforts led to Sargon only rarely being mentioned in later texts. When modern Assyriology

Assyriology (from Greek , ''Assyriā''; and , ''-logia''), also known as Cuneiform studies or Ancient Near East studies, is the archaeological, anthropological, historical, and linguistic study of the cultures that used cuneiform writing. The fie ...

took form in Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

in the 18th century, historians mainly followed the writings of classical Greco-Roman authors and the descriptions of Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , ''māt Aššur'') was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization that existed as a city-state from the 21st century BC to the 14th century BC and eventually expanded into an empire from the 14th century BC t ...

in the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

. '' Shalmaneser V Shalmaneser V (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "Salmānu is foremost"; Biblical Hebrew: ) was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 727 BC to his deposition and death in 722 BC. Though Shalmaneser V's brief reign is poorly known from conte ...

and identifying Sargon as an alternate name for one of the more well-known kings.

After centuries of Sargon being forgotten, there were important developments in Assyriology in the 19th century and the traditional reconstruction of Assyrian history became increasingly challenged in the scholarly community. In 1825, Ernst Friedrich Karl Rosenmüller was the first to recognize Sargon, based solely on the name's single appearance in the Bible, as a distinct king. Though there was some further scholarly support during the years that followed, the most significant developments came after the ruins of Sargon's ancient capital city, . '' Shalmaneser V Shalmaneser V (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "Salmānu is foremost"; Biblical Hebrew: ) was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 727 BC to his deposition and death in 722 BC. Though Shalmaneser V's brief reign is poorly known from conte ...

Dur-Sharrukin

Dur-Sharrukin (, "Fortress of Sargon"; , Syriac Language, Syriac: ܕܘܪ ܫܪܘ ܘܟܢ), present day Khorsabad, was the Assyrian capital in the time of Sargon II of Assyria. Khorsabad is a village in northern Iraq, 15 km northeast of Mosul. ...

, were discovered by Paul-Émile Botta in 1843. Before the cuneiform

Cuneiform is a Logogram, logo-Syllabary, syllabic writing system that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Near East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. Cuneiform script ...

inscriptions were deciphered in 1847 it was impossible to identify the builder of the city. In 1845, Isidore Löwenstern was the first to suggest Sargon as the builder; though Löwenstern's analysis had little scientific basis, his conclusion was by coincidence correct. Sargon was securely identified as the builder of Dur-Sharrukin by Adrien Prévost de Longpérier in 1847, after the inscriptions had been deciphered. Sargon was despite this not immediately recognized as a distinct king, with some still preferring to view him as the same person as one of the more well-established kings. Works published in the 1850s and 1860s, most prominently publications by Edward Hincks, Austen Henry Layard

Sir Austen Henry Layard (; 5 March 18175 July 1894) was an English Assyriologist, traveller, cuneiformist, art historian, draughtsman, collector, politician and diplomat. He was born to a mostly English family in Paris and largely raised in It ...

and George Smith, slowly turned Sargon into a textbook entity. In 1886, he received his own entry in the Ninth edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica and by the beginning of the 20th century he was as well-accepted and recognized as any of the other great Neo-Assyrian kings.

Background

Sargon's death and its implications

Sargon II acceded to the throne of the

Sargon II acceded to the throne of the Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to dominate the ancient Near East and parts of South Caucasus, Nort ...

in 722 BC. By the time of his death in 705, he had ruled the empire with remarkable success for 17 years. Sargon significantly expanded the empire's borders, defeated its most prominent enemies and founded a new capital city named after himself, Dur-Sharrukin

Dur-Sharrukin (, "Fortress of Sargon"; , Syriac Language, Syriac: ܕܘܪ ܫܪܘ ܘܟܢ), present day Khorsabad, was the Assyrian capital in the time of Sargon II of Assyria. Khorsabad is a village in northern Iraq, 15 km northeast of Mosul. ...

. His final military campaign, directed to the notoriously difficult to control region of Tabal in southeastern Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, ended in disaster as the Assyrian camp was attacked by Gurdî of Kulumma and Sargon was killed in the fighting, with the soldiers unable to retrieve his body.

Sargon's legacy in ancient Assyria was severely damaged by the manner of his death; his battlefield death and the inability to recover his body was a major psychological blow for the empire. The ancient Assyrians believed that unburied dead became ghosts (''eṭemmu'') that could come back and haunt the living; these ghosts were further believed to have a miserable existence, being constantly hungry and restless. Sargon's son and successor, Sennacherib

Sennacherib ( or , meaning "Sin (mythology), Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 705BC until his assassination in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is one of the most famous A ...

() was horrified by Sargon's death and believed that he must have committed some unforgivable sin which made the gods abandon him, perhaps that he had offended Babylon's god upon his capture of that city in 710. As a consequence of the theological implications of Sargon's death, Sennacherib did everything he could to distance himself from his father and never wrote or built anything in his memory; he transferred the capital to Nineveh

Nineveh ( ; , ''URUNI.NU.A, Ninua''; , ''Nīnəwē''; , ''Nīnawā''; , ''Nīnwē''), was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul (itself built out of the Assyrian town of Mepsila) in northern ...

and worked to rid the empire of Sargon's imagery and works. Images Sargon had created at the temple in Assur were for instance made invisible through raising the level of the courtyard.

Sargon in ancient sources

Due to Sennacherib's efforts, Sargon is scarcely mentioned in ancient sources. He was mentioned as an ancestor in the inscriptions of some later Assyrian kings, such as his grandsonEsarhaddon

Esarhaddon, also spelled Essarhaddon, Assarhaddon and Ashurhaddon (, also , meaning " Ashur has given me a brother"; Biblical Hebrew: ''ʾĒsar-Ḥaddōn'') was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 681 to 669 BC. The third king of the S ...

(681–669 BC), his great-grandson Shamash-shum-ukin (668–648 BC in Babylonia) and his great-great-grandson Sinsharishkun

Sîn-šar-iškun ( or , meaning " Sîn has established the king")' was the penultimate king of Assyria, reigning from the death of his brother and predecessor Aššur-etil-ilāni in 627 BC to his own death at the Fall of Nineveh in 612 BC.

S ...

(627–612 BC). Ancient Assyria fell in the late 7th century BC, a little less than a century after Sargon's death. Because cuneiform was not decoded by modern researchers until the middle of the 19th century, these references confirming Sargon's existence could not be read by authors and scholars for many centuries following Assyria's fall.

The local population of northern Mesopotamia never forgot ancient Assyria or its most prominent rulers. That Sargon was remembered in some capacity in Mesopotamia comes from scant later Aramaic

Aramaic (; ) is a Northwest Semitic language that originated in the ancient region of Syria and quickly spread to Mesopotamia, the southern Levant, Sinai, southeastern Anatolia, and Eastern Arabia, where it has been continually written a ...

-language sources. According to the 6th-century AD '' History of Karka'', twelve of the then contemporary noble families of Karka (ancient Arrapha) were descendants of ancient Assyrian nobility, explicitly noted as living there in the "time of Sargon". The personal name Sargon also survived, with there for instance being records of a priest at Mardin

Mardin (; ; romanized: ''Mārdīn''; ; ) is a city and seat of the Artuklu District of Mardin Province in Turkey. It is known for the Artuqids, Artuqid architecture of its old city, and for its strategic location on a rocky hill near the Tigris ...

in the 8th century AD called ''Sarguno''. These scant sources had little impact on later scholarship in Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

, where knowledge of Assyria was mainly derived from the writings of classical Greek and Latin authors as well as the accounts of the Assyrian Empire in the Bible.

Though some Assyrian kings, such as Sennacherib and Esarhaddon, are mentioned in multiple places in the Bible, Sargon's name appears only once (Isaiah

Isaiah ( or ; , ''Yəšaʿyāhū'', "Yahweh is salvation"; also known as Isaias or Esaias from ) was the 8th-century BC Israelite prophet after whom the Book of Isaiah is named.

The text of the Book of Isaiah refers to Isaiah as "the prophet" ...

20.1) and he is unmentioned in Classical sources. Early Assyriologists were puzzled by the appearance of the name Sargon in the Bible and tended to identify it as a second name of one of the better known kings, typically Shalmaneser V

Shalmaneser V (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "Salmānu is foremost"; Biblical Hebrew: ) was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 727 BC to his deposition and death in 722 BC. Though Shalmaneser V's brief reign is poorly known from conte ...

, Sennacherib or Esarhaddon. Sargon is recorded in Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

's 2nd century AD Canon of Kings The Canon of Kings was a dated list of kings used by ancient astronomers as a convenient means to date astronomical phenomena, such as eclipses. For a period, the Canon was preserved by the astronomer Claudius Ptolemy, and is thus known sometimes ...

as one of the rulers of Babylon, though under the Greek name ''Arkeanos''. Though scholars found it difficult to identify ''Arkeanos'', it was not the only name in the Canon of Kings at the time unsupported by other known sources. Various explanations were proposed for the identity of ''Arkeanos''; as late as 1857, Maximilian Wolfgang Duncker

Maximilian Wolfgang Duncker (15 October 1811 – 21 July 1886) was a German historian and politician.

Life

Duncker was born in Berlin, Province of Brandenburg, as the eldest son of the publisher Karl Duncker. He studied at the universities of ...

suggested identifying ''Arkeanos'' as a brother of Sennacherib and a vassal ruler of Babylonia.

Rediscovery of Dur-Sharrukin

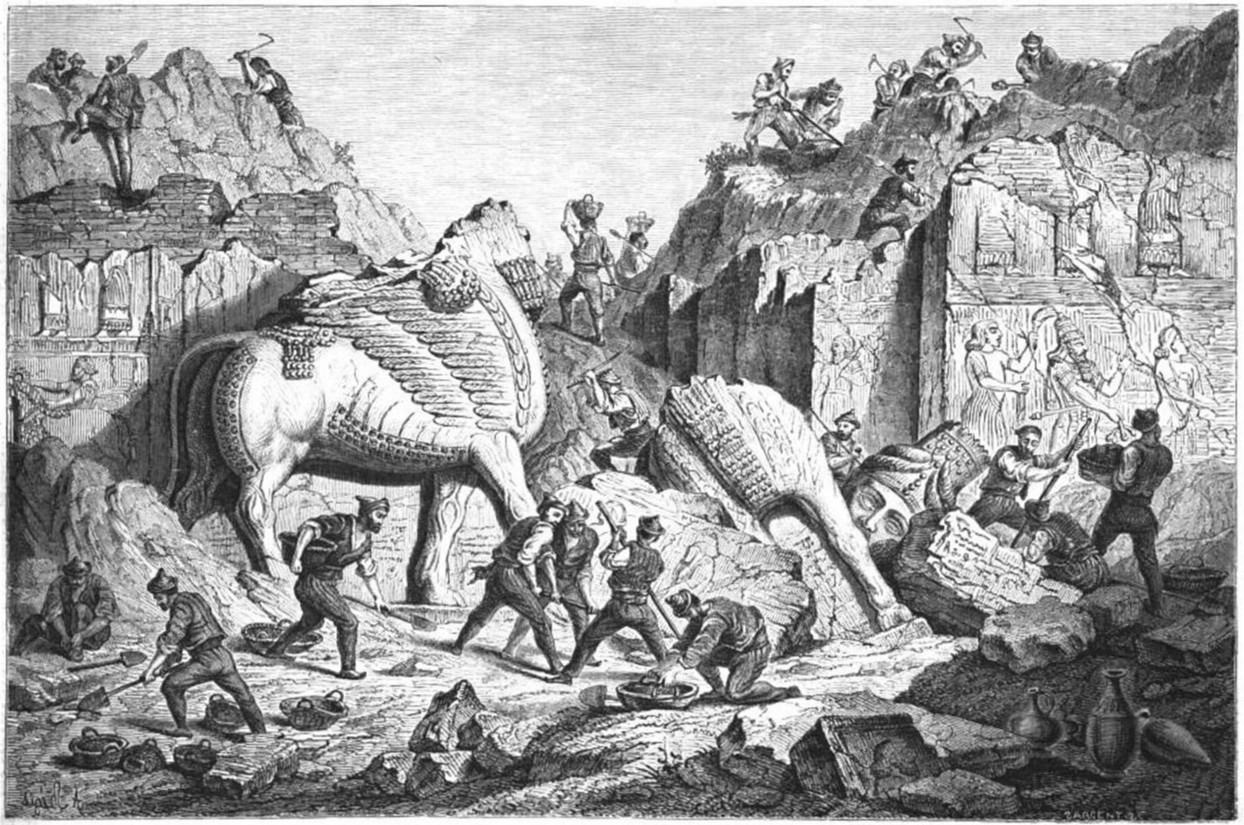

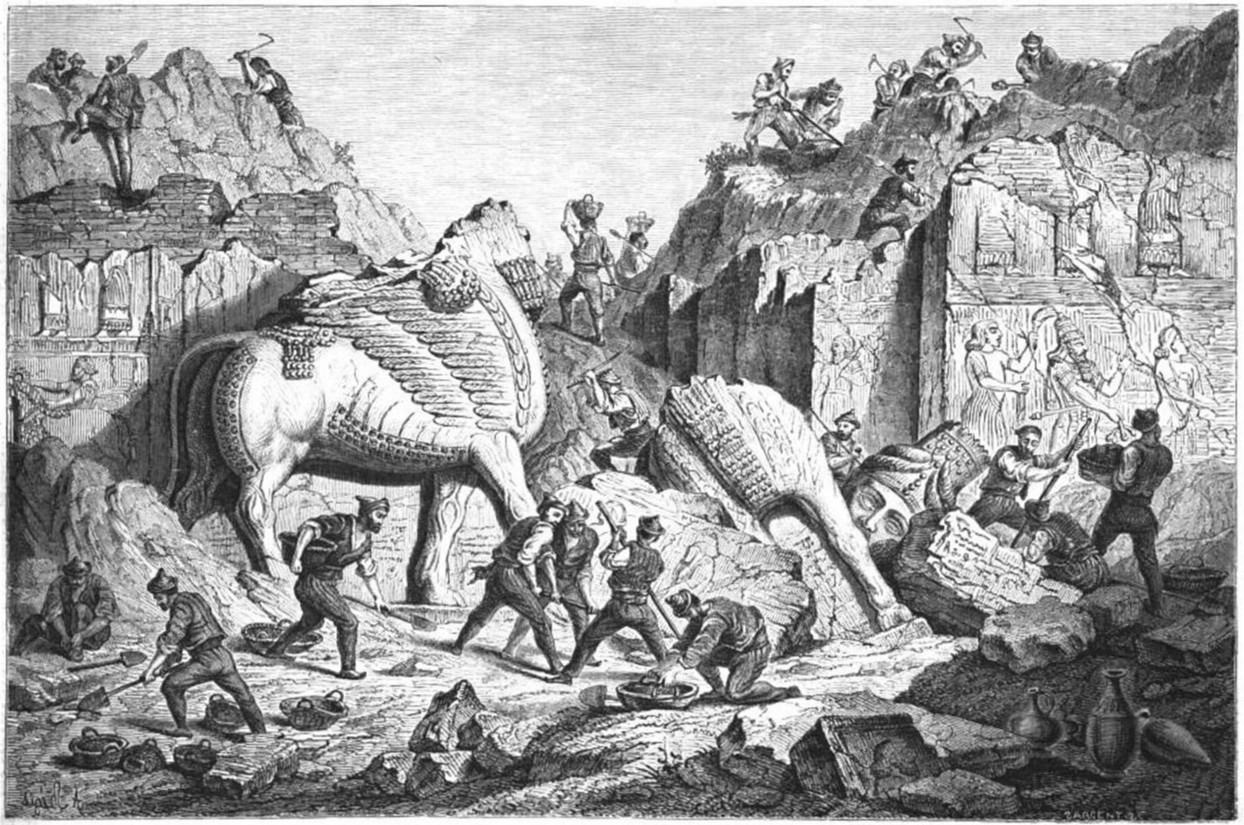

Mesopotamia was long ignored by western archaeologists. Unlike other ancient civilizations, Assyria and other Mesopotamian civilizations left no magnificent ruins above ground; all that remained to see were huge grass-covered mounds in the plains which travellers at times believed to simply be natural features of the landscape. Such scant remains did not fit well with the European idea of ancient great cities, with stone columns and great sculptures like those of Greece and Persia. In the early 19th century, European explorers and archaeologists first began to investigate the ancient mounds, though early archaeologists were chiefly interested in confirming Biblical truth through their excavations rather than spending time on new interpretations of the evidence they discovered. The early excavations were in large part inspired by archaeologcial finds of the British business agent

Mesopotamia was long ignored by western archaeologists. Unlike other ancient civilizations, Assyria and other Mesopotamian civilizations left no magnificent ruins above ground; all that remained to see were huge grass-covered mounds in the plains which travellers at times believed to simply be natural features of the landscape. Such scant remains did not fit well with the European idea of ancient great cities, with stone columns and great sculptures like those of Greece and Persia. In the early 19th century, European explorers and archaeologists first began to investigate the ancient mounds, though early archaeologists were chiefly interested in confirming Biblical truth through their excavations rather than spending time on new interpretations of the evidence they discovered. The early excavations were in large part inspired by archaeologcial finds of the British business agent Claudius Rich

Claudius James Rich (28 March 1787 – 5 October 1821) was a British Assyriologist, business agent, traveller and antiquarian scholar.

Biography

Rich was born near Dijon "of a good family", but passed his childhood at Bristol. Early on, he deve ...

at the site of Nineveh in 1820. After Rich's findings, Julius von Mohl, secretary of the French Société Asiatique

The Société Asiatique (, ) is a French learned society dedicated to the study of Asia. It was founded in 1822 with the mission of developing and diffusing knowledge of Asia. Its boundaries of geographic interest are broad, ranging from the Mag ...

, persuaded the French authorities to create the position of a French consul in Mosul

Mosul ( ; , , ; ; ; ) is a major city in northern Iraq, serving as the capital of Nineveh Governorate. It is the second largest city in Iraq overall after the capital Baghdad. Situated on the banks of Tigris, the city encloses the ruins of the ...

, and to start excavations at Nineveh. The first consul to be appointed was Paul-Émile Botta in 1841.

Using funds secured by Mohl, Botta conducted extensive excavations at Nineveh. Because the ruins of the ancient city were hidden very deep below layers upon layers of later settlement and agricultural activities, Botta never reached them. At the same time as the excavation project at Nineveh failed to conjure up anything of note, the ruins of Dur-Sharrukin were rediscovered by chance. After Botta heard from the locals in 1843 that some finds had been made at the village of Khorsabad

Dur-Sharrukin (, "Fortress of Sargon"; , Syriac: ܕܘܪ ܫܪܘ ܘܟܢ), present day Khorsabad, was the Assyrian capital in the time of Sargon II of Assyria. Khorsabad is a village in northern Iraq, 15 km northeast of Mosul. The great city ...

, 20 kilometers to the northeast, Botta transferred his efforts there. Through excavations headed by Botta and his associate Victor Place, the ruins of Sargon's ancient palace were quickly discovered. Botta did not know what he had found given that cuneiform had not yet been decoded, and simply referred to the site as a "monument" in his writings. The great works of art found at Dur-Sharrukin included great reliefs and stone ''lamassu

''Lama'', ''Lamma'', or ''Lamassu'' (Cuneiform: , ; Sumerian language, Sumerian: lammař; later in Akkadian language, Akkadian: ''lamassu''; sometimes called a ''lamassuse'') is an Mesopotamia, Assyrian protective deity.

Initially depicted as ...

s''. The discovery was swiftly communicated in scholarly circles by Mohl in Paris. In 1847, the first ever exhibition on Assyrian sculptures was held in the Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is a national art museum in Paris, France, and one of the most famous museums in the world. It is located on the Rive Droite, Right Bank of the Seine in the city's 1st arrondissement of Paris, 1st arron ...

, composed of finds from Sargon's palace. After returning to Europe in the late 1840s, Botta compiled an elaborate report on the findings, complete with numerous drawings of the reliefs made by the artist Eugène Flandin

Jean-Baptiste Eugène Napoléon Flandin (15 August 1809 in Naples – 29 September 1889 in Tours), French orientalist, painter, archaeologist, and politician. Flandin's archeological drawings and some of his military paintings are valued mor ...

. The report, published in 1849, showcased the majesty of Assyrian art and architecture and garnered exceptional interest. Under Botta and Place, virtually the entire palace was excavated, as were portions of the surrounding town.

Academic developments

Sargon in early scholarship

Dependent on classical and Biblical information, early Assyriologists reconstructed the line of Assyrian kings as beginning with the legendaryNinus

Ninus (), according to Greek historians writing in the Hellenistic period and later, was the founder of Nineveh (also called Νίνου πόλις "city of Ninus" in Greek), ancient capital of Assyria. The figure or figures with which he correspon ...

and Semiramis

Semiramis (; ''Šammīrām'', ''Šamiram'', , ''Samīrāmīs'') was the legendary Lydian- Babylonian wife of Onnes and of Ninus, who succeeded the latter on the throne of Assyria, according to Movses Khorenatsi. Legends narrated by Diodorus ...

in the 28th century BC, followed by a long gap where no rulers were known, and resuming with Pul, Tiglath-Pileser, Shalmaneser, Sennacherib, Esarhaddon and finally Sardanapalus

According to the Greek writer Ctesias, Sardanapalus ( ; ), sometimes spelled Sardanapallus (), was the last king of Assyria, although in fact Aššur-uballiṭ II (612–605 BC) holds that distinction.

Ctesias' book ''Persica'' is lost, but we ...

, under whom the Assyrian Empire fell. Ninus and Semiramis were sometimes omitted given that scholars doubted the historicity of their legend, but the sequence from Pul onwards was produced identically by virtually all scholars in the 18th century. As mentioned, Sargon's name appearing only once in the Bible led scholars to identify the name as a secondary name of one of the more well-known kings; among others, Campegius Vitringa and Humphrey Prideaux

Humphrey Prideaux (3 May 1648 – 1 November 1724) was a Cornish churchman and orientalist, Dean of Norwich from 1702. His sympathies inclined to Low Churchism in religion and to Whiggism in politics.

Life

The third son of Edmond Prideaux, he ...

identified Sargon with Shalmaneser, Robert Lowth

Robert Lowth ( ; 27 November 1710 – 3 November 1787) was an English clergyman and academic who served as the Bishop of Oxford, Bishop of St Davids, Professor of Poetry and the author of one of the most influential

textbooks of Englis ...

identified Sargon with Sennacherib, and Perizonius

Perizonius (or Accinctus) was the name of Jakob Voorbroek (26 October 1651 – 6 April 1715), a Dutch people, Dutch classical scholar, who was born at Appingedam in Groningen (province), Groningen.

He was the son of Anton Perizonius (1626– ...

and Johann David Michaelis

Johann David Michaelis (27 February 1717 – 22 August 1791) was a German biblical scholar and teacher. He was member of a family that was committed to solid discipline in Hebrew and the cognate languages, which distinguished the University of ...

identified Sargon with Esarhaddon.

In the early 19th century, the straightforward academic vision of Assyria based primarily on the Bible began to be increasingly challenged. Particularly in German scholarship, the first half of the 19th century saw some historians suggesting that Sargon was a distinct historical king. The first historian to do so was Ernst Friedrich Karl Rosenmüller in 1825, who placed Sargon as Tiglath-Pileser's successor. Sargon was also counted as a distinct king by Wilhelm Gesenius

Heinrich Friedrich Wilhelm Gesenius (3 February 178623 October 1842) was a German orientalist, lexicographer, Christian Hebraist, Lutheran theologian, Biblical scholar and critic.

Biography

Gesenius was born at Nordhausen. In 1803 he bec ...

in 1828, August Wilhelm Knobel

August Wilhelm Karl Knobel (7 February 1807 – 25 May 1863) was a German Protestant theologian born in Dębinka, Lubusz Voivodeship, Tzschecheln near Sorau, Niederlausitz.

From 1826 he studied philosophy, philology and theology at the Univer ...

in 1837, Heinrich Ewald

Georg Heinrich August Ewald (16 November 1803 – 4 May 1875) was a German orientalist, Protestant theologian, and Biblical exegete. He studied at the University of Göttingen. In 1827 he became extraordinary professor there, in 1831 ordinary pr ...

in 1847 and Georg Benedikt Winer in 1849; he was sometimes placed after Tiglath-Pileser and sometimes after Shalmaneser.

Dur-Sharrukin and cuneiform

Shortly after the finds at Dur-Sharrukin were publicized, the German Assyriologist Isidore Löwenstern was the first to suggest that the city had been constructed by the Sargon briefly mentioned in the Bible, though he also identified Sargon with Esarhaddon. Löwenstern's identification, published in 1845, was more of a bizarre accident than thorough scholarship. Löwenstern worked two years before cuneiform was deciphered and based his identification primarily on a relief from Dur-Sharrukin depicting a seaside city under Assyrian attack. In the inscription accompanying the relief, Löwenstern erroneously read

Shortly after the finds at Dur-Sharrukin were publicized, the German Assyriologist Isidore Löwenstern was the first to suggest that the city had been constructed by the Sargon briefly mentioned in the Bible, though he also identified Sargon with Esarhaddon. Löwenstern's identification, published in 1845, was more of a bizarre accident than thorough scholarship. Löwenstern worked two years before cuneiform was deciphered and based his identification primarily on a relief from Dur-Sharrukin depicting a seaside city under Assyrian attack. In the inscription accompanying the relief, Löwenstern erroneously read Ashdod

Ashdod (, ; , , or ; Philistine language, Philistine: , romanized: *''ʾašdūd'') is the List of Israeli cities, sixth-largest city in Israel. Located in the country's Southern District (Israel), Southern District, it lies on the Mediterranean ...

, a city mentioned in conjunction with Sargon in the Book of Isaiah. Löwenstern isolated the signs he believed to represent the king's name and, based on their resemblance to Hebrew characters, thought they spelled ''rsk'', which he interpreted as ''Sarak'', further interpreted as a version of Sargon. Though this analysis was wrong at every step, Löwenstern was by coincidence correct that the royal name in the inscription was Sargon.

After the decipherment of cuneiform in 1847, the French archaeologist Adrien Prévost de Longpérier in the same year confirmed that the name of the builder of Dur-Sharrukin was Sargon. This reading was also supported somewhat reluctantly by the British orientalist Henry Rawlinson in 1850, although Rawlinson still considered Sargon and Shalmaneser to be one and the same. Though some proponents of the traditional chronology of kings would remain undecided on the historicity of Sargon, translations of the inscriptions found at Dur-Sharrukin and further exhibitions of finds at the Louvre had made Sargon a textbook entity by the 1860s.

An anonymous article in the Eighth edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica (1853) played a large part in Sargon's recognition since it argued for the king's independent existence. The Irish Assyriologist Edward Hincks was one of the first to attempt to synchronize the Assyrian and Babylonian kings based on both biblical tradition and cuneiform sources; his 1854 work, popularized by Rawlinson in 1862, counted Sargon as a distinct king. Several scholars at around this time also began supporting Sargon's existence. Also important was an essay published by the British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard

Sir Austen Henry Layard (; 5 March 18175 July 1894) was an English Assyriologist, traveller, cuneiformist, art historian, draughtsman, collector, politician and diplomat. He was born to a mostly English family in Paris and largely raised in It ...

in 1858, wherein he argued on the basis of translated inscriptions that Sargon succeeded Shalmaneser and preceded Sennacherib. Another highly important work was published by the English Assyriologist George Smith in 1869, in which he reconstructed Sargon's reign through inscriptions, economical documents and administrative texts.

By 1886, there was no longer any dispute surrounding Sargon's existence; in that year Sargon received his own entry in the Ninth edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica. In 1901, the British Assyriologist Archibald Sayce

Archibald Henry Sayce (25 September 18454 February 1933) was a pioneer British Assyriologist and linguist, who held a chair as Professor of Assyriology at the University of Oxford from 1891 to 1919. He was able to write in at least twenty anci ...

wrote an extensive entry on Sargon's reign. Sayce's essay contained no mention of the previous disputes surrounding Sargon's identity and existence, demonstrating that he by this time was as accepted and recognized as any of the other great Neo-Assyrian kings. In the century following Sayce's essay, further studies turned Sargon into a very well-known Assyrian king. Through the large amount of sources left behind from his time, he is today better known than many of his predecessors and successors.

See also

* ''Damnatio memoriae

() is a modern Latin phrase meaning "condemnation of memory" or "damnation of memory", indicating that a person is to be excluded from official accounts. Depending on the extent, it can be a case of historical negationism. There are and have b ...

''

* Historical revisionism

In historiography, historical revisionism is the reinterpretation of a historical account. It usually involves challenging the orthodox (established, accepted or traditional) scholarly views or narratives regarding a historical event, timespa ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{refend Sargon II Historical revisionism Assyriology