Red Fort Trials on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Indian National Army trials (also known as the INA trials and the Red Fort trials) was the

The Indian National Army trials (also known as the INA trials and the Red Fort trials) was the

However, the number of INA troops captured by Commonwealth forces by the end of the Burma Campaign made it necessary to take a selective policy to charge those accused of the worst allegations. The first of these was the joint trial of

However, the number of INA troops captured by Commonwealth forces by the end of the Burma Campaign made it necessary to take a selective policy to charge those accused of the worst allegations. The first of these was the joint trial of

"Many I.N.A. men already executed, Lucknow"

. ''The Hindustan Times'', 2 November 1945. URL accessed 11 August 2006 which only succeeded in causing further protests.

Letter from members of the Indian National Army Defence Committee to the Viceroy, 15 Oct 1945.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ina Trials

The Indian National Army trials (also known as the INA trials and the Red Fort trials) was the

The Indian National Army trials (also known as the INA trials and the Red Fort trials) was the British Indian

British Indians are citizens of the United Kingdom (UK) whose ancestral roots are from India.

Currently, the British Indian population exceeds 2 million people in the UK, making them the single largest Ethnic groups in the United Kingdo ...

trial by court-martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the arme ...

of a number of officers of the Indian National Army

The Indian National Army (INA, sometimes Second INA; ''Azad Hind Fauj'' ; 'Free Indian Army') was a Empire of Japan, Japanese-allied and -supported armed force constituted in Southeast Asia during World War II and led by Indian Nationalism#An ...

(INA) between November 1945 and May 1946, on various charges of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

, torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons including corporal punishment, punishment, forced confession, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimid ...

, murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification (jurisprudence), justification or valid excuse (legal), excuse committed with the necessary Intention (criminal law), intention as defined by the law in a specific jurisd ...

and abetment to murder, during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

in Poona

Pune ( ; , ISO 15919, ISO: ), previously spelled in English as Poona (List of renamed Indian cities and states#Maharashtra, the official name until 1978), is a city in the state of Maharashtra in the Deccan Plateau, Deccan plateau in Western ...

had announced that Congress would stand responsible for the trials. The committee formed for the defence of INA soldiers was formed by Congress Working Committee. It included Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

, Bhulabhai Desai

Bhulabhai Desai (13 October 1877 – 6 May 1946) was an Indian independence activist and acclaimed lawyer. He is well-remembered for his defence of the three Indian National Army soldiers accused of treason during World War II, and for attem ...

, Asaf Ali

Asaf Ali (11 May 1888 – 2 April 1953) was an Indian independence activist and noted lawyer. He was the first Indian Ambassador to the United States. He also served as the Governor of Odisha. Asaf Ali was born on 11 May 1888 AD in Seohara ...

, Tej Bahadur Sapru

Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru (8 December 1875 20 January 1949) was an Indian freedom fighter, lawyer, and politician. He was a key figure in India's struggle for independence, helping draft the Indian Constitution. He was the leader of the Liberal par ...

, Kailash Nath Katju

Kailash Nath Katju (17 June 1887 – 17 February 1968) was a prominent politician of India. He was the Governor of Odisha and West Bengal, the Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh, the Union Home Minister and the Union Defence Minister. He was ...

and others.

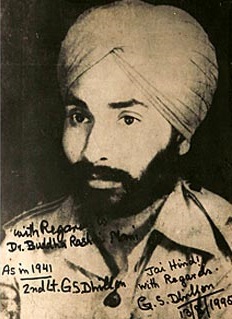

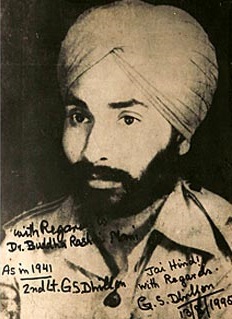

Initially, over 7,600 members of INA were set for trial but due to difficulty in proving their crimes the number of trials were significantly reduced. Approximately ten courts-martial were held. The first of these was the joint court-martial of Colonel Prem Sahgal, Colonel Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon

Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon (18 March 1914 – 6 February 2006) was an Indian military officer of the Indian National Army (INA). He faced charges of "waging war against His Majesty the King Emperor" due to his pivotal role in the Indian independen ...

, and Major-General Shah Nawaz Khan

Shāh (; ) is a royal title meaning "king" in the Persian language.Yarshater, Ehsa, ''Iranian Studies'', vol. XXII, no. 1 (1989) Though chiefly associated with the monarchs of Iran, it was also used to refer to the leaders of numerous Per ...

. The three had been officers in the British Indian Army

The Indian Army was the force of British Raj, British India, until Indian Independence Act 1947, national independence in 1947. Formed in 1895 by uniting the three Presidency armies, it was responsible for the defence of both British India and ...

and were taken prisoner

A prisoner, also known as an inmate or detainee, is a person who is deprived of liberty against their will. This can be by confinement or captivity in a prison or physical restraint. The term usually applies to one serving a Sentence (law), se ...

in Malaya

Malaya refers to a number of historical and current political entities related to what is currently Peninsular Malaysia in Southeast Asia:

Political entities

* British Malaya (1826–1957), a loose collection of the British colony of the Straits ...

, Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

and Burma

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and ha ...

. They had, alongside a large number of other troops and officers of the British Indian Army, joined the Indian National Army

The Indian National Army (INA, sometimes Second INA; ''Azad Hind Fauj'' ; 'Free Indian Army') was a Empire of Japan, Japanese-allied and -supported armed force constituted in Southeast Asia during World War II and led by Indian Nationalism#An ...

and later fought in Burma alongside the Japanese military

The are the military forces of Japan. Established in 1954, the JSDF comprises the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force, the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force, and the Japan Air Self-Defense Force. They are controlled by the Ministry of Defense w ...

under the Azad Hind

The Provisional Government of Free India or, more simply, Azad Hind, was a short-lived Japanese-controlled provisional government in India. It was established in Japanese occupied Singapore during World War II in October 1943 and has been con ...

. These three came to be the only defendants in the trials who were charged with "waging war against the King-Emperor" (the ''Indian Army Act, 1911

The Indian Army was the force of British India, until national independence in 1947. Formed in 1895 by uniting the three Presidency armies, it was responsible for the defence of both British India and the princely states, which could also have ...

'' did not provide for a separate charge for treason) as well as murder and abetment of murder. Those charged later only faced trial for torture and murder or abetment of murder.

The trials covered arguments based on military law

Military justice (or military law) is the body of laws and procedures governing members of the armed forces. Many nation-states have separate and distinct bodies of law that govern the conduct of members of their armed forces. Some states us ...

, constitutional law

Constitutional law is a body of law which defines the role, powers, and structure of different entities within a state, namely, the executive, the parliament or legislature, and the judiciary; as well as the basic rights of citizens and, in ...

, international law

International law, also known as public international law and the law of nations, is the set of Rule of law, rules, norms, Customary law, legal customs and standards that State (polity), states and other actors feel an obligation to, and generall ...

, and politics

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

. Historian Mithi Mukherjee has called the event of the trial "a key moment in the elaboration of an anticolonial critique of international law in India." As it was an army trial, Lt. Col. Horilal Varma Bar At Law & the then-Prime Minister of the Rampur State, along with Tej Bahadur Sapru, served as the lawyers for the defendants. These trials attracted much publicity, and public sympathy for the defendants, particularly as India was in the final stages of the Indian independence movement

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events in South Asia with the ultimate aim of ending British Raj, British colonial rule. It lasted until 1947, when the Indian Independence Act 1947 was passed.

The first nationalistic ...

. Outcry over the grounds of the trial, as well as a general emerging unease and unrest within the troops of the Raj, ultimately forced the then- Army Chief Field Marshal Claude Auchinleck

Field marshal (United Kingdom), Field Marshal Sir Claude John Eyre Auchinleck ( ) (21 June 1884 – 23 March 1981), was a British Indian Army commander who saw active service during the world wars. A career soldier who spent much of his militar ...

to commute the sentences of the three defendants in the first trial.

Indian National Army

Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

, as well as South East Asia, was a major refuge for Indian nationalists living in exile before the start of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

who formed strong proponents of militant nationalism and also influenced Japanese policy significantly. Although Japanese intentions and policies with regards to India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

were far from concrete at the start of the war, Japan had sent intelligence missions, notably under Major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

I Fujiwara, into South Asia even before the start of the World War II to garner support from the Malayan Sultans, the Burmese resistance and the Indian movement. These missions were successful in establishing contacts with Indian nationalists

Indian nationalism is an instance of civic nationalism. It is inclusive of all of the people of India, despite their diverse ethnic, linguistic and religious backgrounds. Indian nationalism can trace roots to pre-colonial India, but was f ...

in exile in Thailand

Thailand, officially the Kingdom of Thailand and historically known as Siam (the official name until 1939), is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. With a population of almost 66 million, it spa ...

and Malaya

Malaya refers to a number of historical and current political entities related to what is currently Peninsular Malaysia in Southeast Asia:

Political entities

* British Malaya (1826–1957), a loose collection of the British colony of the Straits ...

, supporting the establishment and organisation of the Indian Independence League

The Indian Independence League (also known as IIL) was a political organisation operated from the 1920s to the 1940s to organise those living outside British India into seeking the removal of British colonial rule over the region. Founded by In ...

.

At the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

in South East Asia, 70,000 Indian troops were stationed in Malaya. After the start of the war, Japan's Malayan Campaign

The Malayan campaign, referred to by Japanese sources as the , was a military campaign fought by Allies of World War II, Allied and Axis powers, Axis forces in British Malaya, Malaya, from 8 December 1941 – 15 February 1942 during the World War ...

had brought under her control considerable numbers of Indian prisoners of war, notably nearly 55,000 after the Fall of Singapore

The fall of Singapore, also known as the Battle of Singapore, took place in the South–East Asian theatre of the Pacific War. The Empire of Japan captured the British stronghold of Singapore, with fighting lasting from 8 to 15 February 1942. S ...

. The conditions in the Japanese prisoner of war camps were notorious and led to some of the troops deserting, when offered release by their captors, and forming a nationalist army. From these deserters, the First Indian National Army

The First Indian National Army (First INA) was the Indian National Army as it existed between February and December 1942. It was formed with Japanese aid and support after the Fall of Singapore and consisted of approximately 12,000 of the 40,0 ...

was formed under Mohan Singh Deb

Mohan Singh (3 January 1909 – 26 December 1989) was an Indian military officer and politician. He was a British Indian Army officer, and later member of the Indian Independence Movement, best known for founding and leading the Indian National ...

and received considerable Japanese aid and support. It was formally proclaimed in September 1942 and declared the subordinate military wing of the Indian Independence League

The Indian Independence League (also known as IIL) was a political organisation operated from the 1920s to the 1940s to organise those living outside British India into seeking the removal of British colonial rule over the region. Founded by In ...

in June that year. The unit was dissolved in December 1942 after apprehensions of Japanese motives with regards to the INA led to disagreements and distrust between Mohan Singh and INA leadership on one hand, and the League's leadership, most notable Rash Behari Bose

Rash Behari Bose (; 25 May 1886 – 21 January 1945) was an Indian revolutionary leader and freedom fighter who fought against the British Empire. He was one of the key organisers of the Ghadar Mutiny and founded the Indian Independence Lea ...

. The arrival of Subhas Bose in June 1943 saw the revival and reorganisation of the unit as the army of the Azad Hind

The Provisional Government of Free India or, more simply, Azad Hind, was a short-lived Japanese-controlled provisional government in India. It was established in Japanese occupied Singapore during World War II in October 1943 and has been con ...

government that was formed in October 1943. Within days of its proclamation in October 1943, the Azad Hind had been accorded recognition by Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, Fascist Italy

Fascist Italy () is a term which is used in historiography to describe the Kingdom of Italy between 1922 and 1943, when Benito Mussolini and the National Fascist Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictatorship. Th ...

, Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

, Thailand

Thailand, officially the Kingdom of Thailand and historically known as Siam (the official name until 1939), is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. With a population of almost 66 million, it spa ...

, Ba Maw's Burmese government, and some other Axis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics

*A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular:

** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system

*** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ...

-allied nations, as well as receiving felicitations and gifts from the government of neutral Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

and Irish republican

Irish republicanism () is the political movement for an Irish republic, void of any British rule. Throughout its centuries of existence, it has encompassed various tactics and identities, simultaneously elective and militant and has been both w ...

s who had left British rule in 1912. The Azad Hind government declared war on Britain and America in October 1943. In Nov 1943, Azad Hind had been given a limited form of governmental jurisdiction over the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, which had been captured by the Japanese navy

The , abbreviated , also simply known as the Japanese Navy, is the maritime warfare branch of the Japan Self-Defense Forces, tasked with the naval defense of Japan. The JMSDF was formed following the dissolution of the Imperial Japanese Navy ( ...

early on in the war. In the early part of 1944, INA forces were in action along with the Japanese forces in Imphal

Imphal (; , ) is the capital city of the Indian state of Manipur. The metropolitan centre of the city contains the ruins of Kangla Palace (officially known as Kangla Fort), the royal seat of the former Kingdom of Manipur, surrounded by a ...

and Kohima area against Commonwealth forces, and later fell back with the retreating Japanese forces after the failed campaign. In early 1945, the INA's troops were committed against the successful Allied Burma Campaign

The Burma campaign was a series of battles fought in the British colony of British rule in Burma, Burma as part of the South-East Asian theatre of World War II. It primarily involved forces of the Allies of World War II, Allies (mainly from ...

. Most of the INA troops were captured, defected or fell otherwise into British hands during the Burma campaign by end of March that year and by the time Rangoon

Yangon, formerly romanized as Rangoon, is the capital of the Yangon Region and the largest city of Myanmar. Yangon was the List of capitals of Myanmar, capital of Myanmar until 2005 and served as such until 2006, when the State Peace and Dev ...

fell in May 1945, the INA had more or less ceased to exist although some activities continued until Singapore was recaptured.

At the conclusion of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the government of British India brought some of the captured INA soldiers to trial on treason charges. The prisoners would potentially face the death penalty, life imprisonment or a fine as punishment if found guilty.

Early trials

By 1943 and 1944,courts martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the arme ...

were taking place in India of former personnel of the British Indian Army

The Indian Army was the force of British Raj, British India, until Indian Independence Act 1947, national independence in 1947. Formed in 1895 by uniting the three Presidency armies, it was responsible for the defence of both British India and ...

who were captured fighting in INA ranks or working in support of the INA's subversive activities. These did not receive any publicity or political sympathies and support until much later. The charges in these earlier trials were of "Committing a civil offence contrary to the Section 41 of the Indian Army Act,1911 or the Section 41 of the Burma Army Act" with the offence specified as "Waging War against the King" contrary to the Section 121 of the Indian Penal Code

The Indian Penal Code (IPC) was the official criminal code of the Republic of India, inherited from British India after independence. It remained in force until it was repealed and replaced by the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) in December 2023 ...

and the Burma Penal Code as relevant.

With the release of Sarat Chandra Bose

Sarat Chandra Bose (6 September 1889 – 20 February 1950) was an Indian barrister and independence activist.

Early life

He was born to Janakinath Bose (father) and Prabhabati Devi in Cuttack, Odisha on 6 September 1889. The family origina ...

on 14 September 1945, the trials began to take an organised form.

Public trials

However, the number of INA troops captured by Commonwealth forces by the end of the Burma Campaign made it necessary to take a selective policy to charge those accused of the worst allegations. The first of these was the joint trial of

However, the number of INA troops captured by Commonwealth forces by the end of the Burma Campaign made it necessary to take a selective policy to charge those accused of the worst allegations. The first of these was the joint trial of Shah Nawaz Khan

Shāh (; ) is a royal title meaning "king" in the Persian language.Yarshater, Ehsa, ''Iranian Studies'', vol. XXII, no. 1 (1989) Though chiefly associated with the monarchs of Iran, it was also used to refer to the leaders of numerous Per ...

, Prem Sahgal and Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon

Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon (18 March 1914 – 6 February 2006) was an Indian military officer of the Indian National Army (INA). He faced charges of "waging war against His Majesty the King Emperor" due to his pivotal role in the Indian independen ...

, followed by the trials of Abdul Rashid, Shinghara Singh, Fateh Khan, Captain Malik Munawar Khan Awan

Malik Munawar Khan Awan () was a Major rank officer in the Pakistan Army, whose career had begun in the British Indian Army and included spells in the Imperial Japanese Army and the revolutionary Indian National Army that fought against the All ...

, Captain Allah Yar Khan, and several other commissioned officers of the INA. The decision was made to hold a public trial, as opposed to the earlier trials, and given the political importance and significance of the trials, the decision was made to hold these at the Red Fort

The Red Fort, also known as Lal Qila () is a historic Mughal Empire, Mughal fort in Delhi, India, that served as the primary residence of the Mughal emperors. Emperor Shah Jahan commissioned the construction of the Red Fort on 12 May 1639, fo ...

. Also, due to the complexity of the case, the provision was made under the Indian Army Act rule 82(a) for counsels to appear for defence and prosecution. The then Advocate General of India, Sir Naushirwan P Engineer was appointed the counsel for Prosecution.

INA Defence committee

TheIndian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

made the release of the three defendants an important political issue during the agitation for independence of 1945–6. The INA Defence Committee was a committee established by the Indian National Congress in 1945 to defend those officers of the Indian National Army who were to be charged during the INA trials. Additional responsibilities of the committee also came to be the co-ordination of information on INA troops held captive, as well as arranging for relief for troops after the war. The committee declared the formation of the Congress' defence team for the INA and included Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

, Tej Bahadur Sapru, Bhulabhai Desai, R.B. Badri Das, Asaf Ali

Asaf Ali (11 May 1888 – 2 April 1953) was an Indian independence activist and noted lawyer. He was the first Indian Ambassador to the United States. He also served as the Governor of Odisha. Asaf Ali was born on 11 May 1888 AD in Seohara ...

, Kanwar Sir Dalip Singh, Kailash Nath Katju

Kailash Nath Katju (17 June 1887 – 17 February 1968) was a prominent politician of India. He was the Governor of Odisha and West Bengal, the Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh, the Union Home Minister and the Union Defence Minister. He was ...

, Bakshi Sir Tek Chand, P.N. Sen, Inder Deo Dua, Shiv Kumar Shastri, Ranbeer Chand Soni, Rajinder Narayan, Sultan Yar Khan, Narayan Andley and J.K. Khanna.

The first trial

The first trial, that of Shah Nawaz Khan, Gurubaksh Singh Dhillon and Prem Sahgal was held between November and December 1945 against the backdrop ofgeneral elections in India

India has a parliamentary system as defined by its constitution, with power distributed between the union government and the states. India's democracy is the largest democracy in the world.

The President of India is the ceremonial head of ...

with the Attorney General of India, Noshirwan P. Engineer as the chief prosecutor and two dozen counsel for the defence, led by Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru and fronted by Lt. Col Horilal Varma Bar At Law All three of the accused were charged with "waging war against the king contrary to section 121 of the Indian Penal Code". In addition, charges of murder were leveled against Dhillon and of abetment to murder against Khan and Sahgal. The defendants were Punjabis

The Punjabis (Punjabi language, Punjabi: ; ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ; romanised as Pañjābī) are an Indo-Aryan peoples, Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group associated with the Punjab region, comprising areas of northwestern India and eastern Paki ...

who came from three different religions – one Hindu

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

, one Sikh

Sikhs (singular Sikh: or ; , ) are an ethnoreligious group who adhere to Sikhism, a religion that originated in the late 15th century in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, based on the revelation of Guru Nanak. The term ''Si ...

, and one Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

– but all three elected to be defended by the defence committee set up by the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

.

Second trial

These were the trials of Captain Abdul Rashid, Captain Shinghara Singh Mann, Captain Munawar Khan, Captain Allah Yar Khan, Lieutenant Fateh Khan and some other officers. Shangara Singh was awarded the Sardar-e-Jung, the second-highest decoration bestowed by Azad Hind government for valour in combat, and the Vir-e-Hind medal. Subhas Chandra Bose himself gave Singh Mann his medals in Rangoon. He was captured by the British and held in a prison in Multan from January 1945 to February 1946. After his release, he returned to his family in the Punjab. In 1959, he settled in Vadodara, Gujarat, where he remained as of 2001. He died aged 113. Though Captain Allah Yar Khan and few of his coompanions were listed as POWs but in fact they escaped into jungle surrounding Singapore, fearing torture at the hands of the Japanese soldiers. They survived in jungle hunting and stalking on Japanese supply until October 1943 when they joined the second INA raised under Subhas Chandra Bose. At the time of trial, Captain Khan was under treatment at India-based General Hospital in Bangalore. In the wake of unrest over the charges of treason and glorification of INA soldiers in the first trial, the charges of treason was dropped. However, these officers were cashiered from army with rank reduction from the date of grant of emergency commission. The site of trial was also moved from the Red Fort to an adjoining building.Consequences of the trials

Beyond the concurrent campaigns of noncooperation and nonviolent protest, this spread to include mutinies and wavering support within the British Indian Army. This movement marked the last major campaign in which the forces of the Congress and the Muslim League aligned together; the Congresstricolor

A triband is a vexillological style which consists of three stripes arranged to form a flag. These stripes may be two or three colours, and may be charged with an emblem in the middle stripe. Not all tribands are tricolour flags, which requires t ...

and the green flag of the League were flown together at protests. In spite of this aggressive and widespread opposition, the court martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the mili ...

was carried out and all three defendants were sentenced to deportation for life. This sentence, however, was never carried out, as the immense public pressure of the demonstrations forced Claude Auchinleck

Field marshal (United Kingdom), Field Marshal Sir Claude John Eyre Auchinleck ( ) (21 June 1884 – 23 March 1981), was a British Indian Army commander who saw active service during the world wars. A career soldier who spent much of his militar ...

, Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army, to release all three defendants. A slogan popular during this time was, "Laal quile se aayi aawaz, Sahgal, Dhillon, Shahnawaaz". ()

During the trial, mutiny broke out in the Royal Indian Navy, incorporating ships and shore establishments of the RIN throughout India from Karachi

Karachi is the capital city of the Administrative units of Pakistan, province of Sindh, Pakistan. It is the List of cities in Pakistan by population, largest city in Pakistan and 12th List of largest cities, largest in the world, with a popul ...

to Bombay

Mumbai ( ; ), also known as Bombay ( ; its official name until 1995), is the capital city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Maharashtra. Mumbai is the financial centre, financial capital and the list of cities i ...

and from Vizag

Visakhapatnam (; List of renamed places in India, formerly known as Vizagapatam, and also referred to as Vizag, Visakha, and Waltair) is the largest and most populous metropolitan city in the States and union territories of India, Indian stat ...

to Calcutta

Kolkata, also known as Calcutta (List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, its official name until 2001), is the capital and largest city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal. It lies on the eastern ba ...

. The most significant if disconcerting factor for the Raj was the significant militant public support that it received. At some places, NCOs in the British Indian Army

The Indian Army was the force of British Raj, British India, until Indian Independence Act 1947, national independence in 1947. Formed in 1895 by uniting the three Presidency armies, it was responsible for the defence of both British India and ...

started ignoring orders from British superiors. In Madras

Chennai, also known as Madras ( its official name until 1996), is the capital and largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost state of India. It is located on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal. According to the 2011 Indian ce ...

and Pune

Pune ( ; , ISO 15919, ISO: ), previously spelled in English as Poona (List of renamed Indian cities and states#Maharashtra, the official name until 1978), is a city in the state of Maharashtra in the Deccan Plateau, Deccan plateau in Western ...

, the British garrisons had to face revolts within the ranks of the British Indian Army.

Another Army mutiny took place at Jabalpur during the last week of February 1946, soon after the Navy mutiny at Bombay, which were both suppressed. It lasted about one week. After the mutiny, about 45 persons were tried by court martial. 41 were sentenced to varying terms of imprisonment or dismissal. In addition, a large number were discharged on administrative grounds. While the participants of the Naval Mutiny were given the freedom fighters' pension, the Jabalpur mutineers got nothing. They even lost their service pension.

Most of the INA soldiers were set free after cashiering

Cashiering (or degradation ceremony), generally within military forces, is a ritual dismissal of an individual from some position of responsibility for a breach of discipline.

Etymology

From the Flemish (to dismiss from service; to discard ...

and forfeiture of pay and allowance.

Lord Louis Mountbatten

Admiral of the Fleet Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (born Prince Louis of Battenberg; 25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979), commonly known as Lord Mountbatten, was a British statesman, Royal Navy off ...

, the head of Southeast Asia Command, ordered the INA memorial to its fallen soldiers to be demolished when Singapore was recaptured in 1945. It has been suggested by some historians that Mountbatten's decision to demolish the INA memorial was part of a larger effort to prevent the spread of the socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

ideals of the INA in the political atmosphere of the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

and the decolonisation of Asia

The decolonisation of Asia was the gradual growth of independence movements in Asia, leading ultimately to the retreat of foreign powers and the creation of several nation-states in the region.

Background

The decline of Spain and Portugal i ...

. In 1995, the National Heritage Board of Singapore marked the place as a historical site. A Cenotaph

A cenotaph is an empty grave, tomb or a monument erected in honor of a person or group of people whose remains are elsewhere or have been lost. It can also be the initial tomb for a person who has since been reinterred elsewhere. Although t ...

has since been erected at the site where the memorial once stood.

After the war ended, the story of the INA and the Free India Legion was seen as so inflammatory that, fearing mass revolts and uprisings—not just in India, but across its empire—the British government forbade the BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

from broadcasting their story. However, the stories of the trials at the Red Fort

The Red Fort, also known as Lal Qila () is a historic Mughal Empire, Mughal fort in Delhi, India, that served as the primary residence of the Mughal emperors. Emperor Shah Jahan commissioned the construction of the Red Fort on 12 May 1639, fo ...

filtered through. Newspapers reported at the time of the trials that some of the INA soldiers held at Red Fort had been executed,. ''The Hindustan Times'', 2 November 1945. URL accessed 11 August 2006

In popular culture

The 2017 period drama film '' Raag Desh'' is based on the INA trials.See also

*Indian National Army

The Indian National Army (INA, sometimes Second INA; ''Azad Hind Fauj'' ; 'Free Indian Army') was a Empire of Japan, Japanese-allied and -supported armed force constituted in Southeast Asia during World War II and led by Indian Nationalism#An ...

* INA Defence Committee, the legal defence team for the INA formed by the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

in 1945.

* Shah Nawaz Khan

Shāh (; ) is a royal title meaning "king" in the Persian language.Yarshater, Ehsa, ''Iranian Studies'', vol. XXII, no. 1 (1989) Though chiefly associated with the monarchs of Iran, it was also used to refer to the leaders of numerous Per ...

, Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon

Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon (18 March 1914 – 6 February 2006) was an Indian military officer of the Indian National Army (INA). He faced charges of "waging war against His Majesty the King Emperor" due to his pivotal role in the Indian independen ...

and Prem Kumar Sahgal

Lieutenant colonel Prem Kumar Sahgal (25 March 1917 – 17 October 1992) was an Indian Army officer in the British Indian Army. After becoming a Japanese prisoner of war, he served as an officer in the Indian National Army, which was led by Su ...

, defendants in the first INA trial.

* Malik Munawar Khan Awan

Malik Munawar Khan Awan () was a Major rank officer in the Pakistan Army, whose career had begun in the British Indian Army and included spells in the Imperial Japanese Army and the revolutionary Indian National Army that fought against the All ...

, who commanded the 2nd INA Guerrilla Battalion during the Battle of Imphal.

* Habib-ur-Rehman, Subhas Chandra Bose's chief of staff.

* Lakshmi Sahgal

Lakshmi Sahgal () (born Lakshmi Swaminathan; 24 October 1914 – 23 July 2012) was an Indian politician and activist. She was a revolutionary of the Indian independence movement, an officer of the Indian National Army, and the Minister of Women ...

, who commanded the Rani of Jhansi Regiment

The Rani of Jhansi Regiment was the women's regiment of the Indian National Army, the armed force formed by Indian nationalists in 1942 in Southeast Asia with the aim of overthrowing the British Raj in colonial India, with Japanese assistance. ...

and was also the minister in charge of women's affairs in the Azad Hind

The Provisional Government of Free India or, more simply, Azad Hind, was a short-lived Japanese-controlled provisional government in India. It was established in Japanese occupied Singapore during World War II in October 1943 and has been con ...

government.

* Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

References

Letter from members of the Indian National Army Defence Committee to the Viceroy, 15 Oct 1945.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ina Trials

INA trial

The Indian National Army trials (also known as the INA trials and the Red Fort trials) was the British Indian trial by court-martial of a number of officers of the Indian National Army (INA) between November 1945 and May 1946, on various charges ...

Indian independence movement

History of the Indian Army

Military of British India

Court-martial cases

1945 in India

1946 in India

Aftermath of World War II

Treason trials

Indian military scandals