Red Barn Murder on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

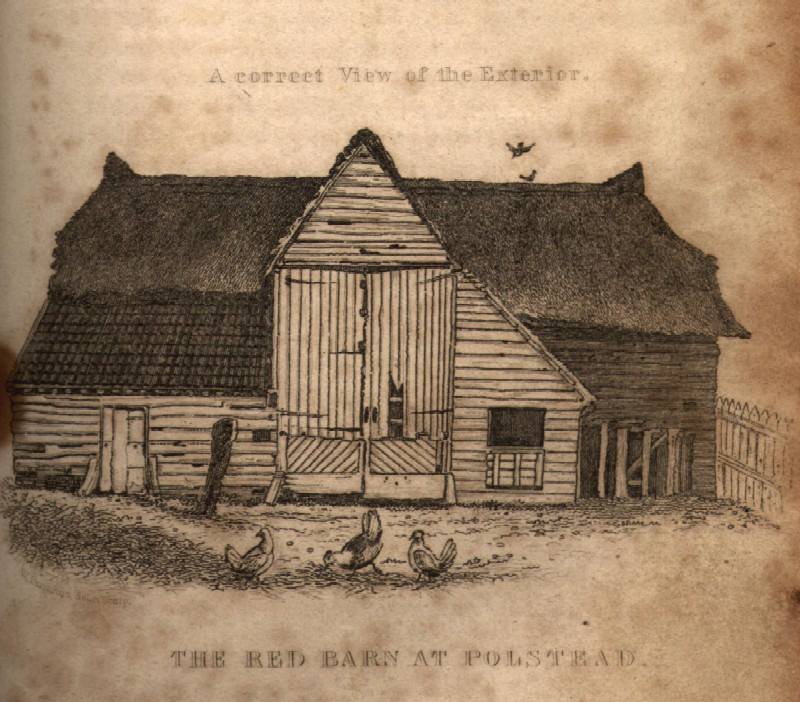

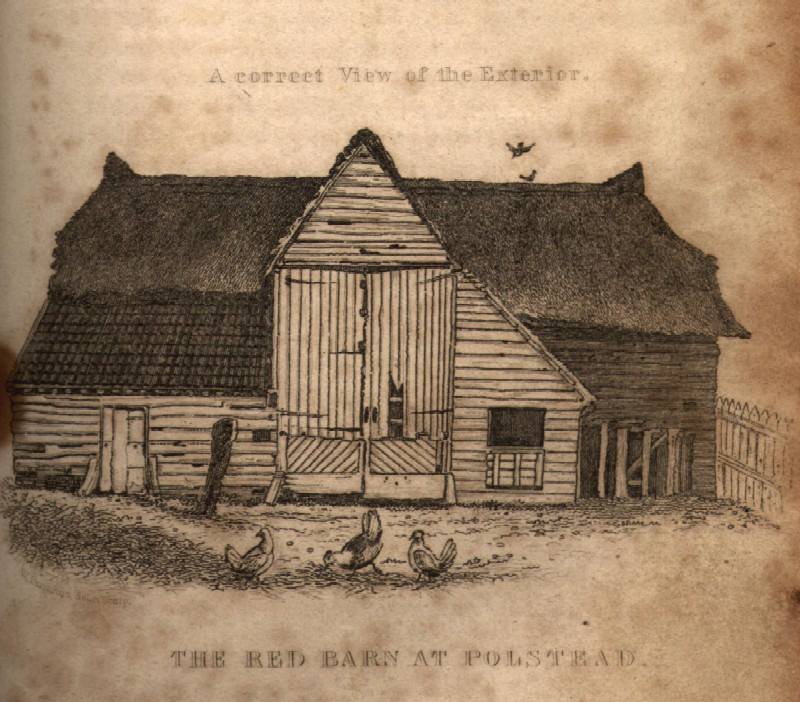

The Red Barn Murder was an 1827 murder in Polstead,

The Red Barn Murder was an 1827 murder in Polstead,

Maria Marten (born 24 July 1801) was the daughter of Thomas Marten, a

Maria Marten (born 24 July 1801) was the daughter of Thomas Marten, a  Shortly after Corder left the Martens' cottage, Marten set out to meet him at the Red Barn, which was situated on Barnfield Hill, about half a mile from the cottage. This was the last time that she was seen alive. Corder also disappeared, but later turned up and claimed that Marten was in Ipswich, or some other place nearby, and that he could not yet bring her back as his wife for fear of provoking the anger of his friends and relatives. The pressure on Corder to produce his wife eventually forced him to leave the area. He wrote letters to Marten's family claiming that they were married and living on the

Shortly after Corder left the Martens' cottage, Marten set out to meet him at the Red Barn, which was situated on Barnfield Hill, about half a mile from the cottage. This was the last time that she was seen alive. Corder also disappeared, but later turned up and claimed that Marten was in Ipswich, or some other place nearby, and that he could not yet bring her back as his wife for fear of provoking the anger of his friends and relatives. The pressure on Corder to produce his wife eventually forced him to leave the area. He wrote letters to Marten's family claiming that they were married and living on the

Corder was easily discovered, as Ayres, the constable in Polstead, was able to obtain his old address from a friend. Ayres was assisted by James Lea, an officer of the London police who later led the investigation into "

Corder was easily discovered, as Ayres, the constable in Polstead, was able to obtain his old address from a friend. Ayres was assisted by James Lea, an officer of the London police who later led the investigation into "

Corder was taken back to Suffolk, where he was tried at Shire Hall,

Corder was taken back to Suffolk, where he was tried at Shire Hall,

On 11 August 1828, Corder was taken to the

On 11 August 1828, Corder was taken to the  Several copies of Corder's

Several copies of Corder's

Plays were being performed while Corder was still awaiting trial, and an anonymous author published a melodramatic version of the murder after the execution, a precursor of the Newgate novels which quickly became best-sellers. The Red Barn Murder was a popular subject, along with the story of

Plays were being performed while Corder was still awaiting trial, and an anonymous author published a melodramatic version of the murder after the execution, a precursor of the Newgate novels which quickly became best-sellers. The Red Barn Murder was a popular subject, along with the story of  Pieces of the rope which was used to hang Corder sold for a

Pieces of the rope which was used to hang Corder sold for a

Account of the case in The Newgate Calendar

{{DEFAULTSORT:Red Barn Murder 1827 in England 1827 murders in the United Kingdom 19th century in Suffolk Violence against women in England Murder in Suffolk Polstead Murder trials in the United Kingdom 19th-century trials Uxoricides Deaths by firearm in England

The Red Barn Murder was an 1827 murder in Polstead,

The Red Barn Murder was an 1827 murder in Polstead, Suffolk

Suffolk ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East of England and East Anglia. It is bordered by Norfolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Essex to the south, and Cambridgeshire to the west. Ipswich is the largest settlement and the county ...

, England. A young woman, Maria Marten, was shot dead by her lover William Corder at the Red Barn, a local landmark. The two had arranged to meet before eloping to Ipswich

Ipswich () is a port town and Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in Suffolk, England. It is the county town, and largest in Suffolk, followed by Lowestoft and Bury St Edmunds, and the third-largest population centre in East Anglia, ...

. Corder sent letters to Marten's family claiming that she was well, but after her stepmother spoke of having dreamed that Maria had been murdered, her body was discovered in the barn the next year.

Corder was located in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, where he had married. He was returned to Suffolk and found guilty of murder in a well-publicised trial. In 1828, he was hanged

Hanging is killing a person by suspending them from the neck with a noose or ligature strangulation, ligature. Hanging has been a standard method of capital punishment since the Middle Ages, and has been the primary execution method in numerou ...

at Bury St Edmunds

Bury St Edmunds (), commonly referred to locally as ''Bury,'' is a cathedral as well as market town and civil parish in the West Suffolk District, West Suffolk district, in the county of Suffolk, England.OS Explorer map 211: Bury St. Edmunds an ...

in an execution witnessed by a huge crowd. The story provoked numerous newspaper articles, songs and plays. The village where the crime had taken place became a tourist attraction and the barn was stripped by souvenir hunters. Plays, ballads and songs about the murder remained popular throughout the next century and continue to be performed today.

Murder

Maria Marten (born 24 July 1801) was the daughter of Thomas Marten, a

Maria Marten (born 24 July 1801) was the daughter of Thomas Marten, a molecatcher

A molecatcher (also called a mowdy-catcher) is a person who traps or kills mole (animal), moles in places where they are considered a nuisance to crops, lawns, sportsfields or gardens.

History of molecatching Roman times

Excavations of Ancient ...

from Polstead in Suffolk

Suffolk ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East of England and East Anglia. It is bordered by Norfolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Essex to the south, and Cambridgeshire to the west. Ipswich is the largest settlement and the county ...

. In March 1826, when she was aged 24, Marten formed a relationship with 22-year-old William Corder. Marten was an attractive woman and relationships with men from the neighbourhood had already resulted in two children. One child belonging to Corder's older brother Thomas died as an infant, but the other, Thomas Henry, was still alive at the time Corder met Marten. Thomas Henry's father, Peter Matthews, did not marry Marten but regularly sent money to provide for the child.

Corder (born c. 1803) was the son of a local farmer and had a reputation as something of a fraud

In law, fraud is intent (law), intentional deception to deprive a victim of a legal right or to gain from a victim unlawfully or unfairly. Fraud can violate Civil law (common law), civil law (e.g., a fraud victim may sue the fraud perpetrato ...

ster and ladies' man. He was known as "Foxey" at school because of his sly manner. Corder once fraudulently sold his father's pigs, although his father had settled the matter without involving the law, but Corder had not changed his behaviour. He later obtained money by passing a forged

Forging is a manufacturing process involving the shaping of metal using localized compression (physics), compressive forces. The blows are delivered with a hammer (often a power hammer) or a die (manufacturing), die. Forging is often classif ...

cheque

A cheque (or check in American English) is a document that orders a bank, building society, or credit union, to pay a specific amount of money from a person's account to the person in whose name the cheque has been issued. The person writing ...

for £93 and had helped local thief Samuel "Beauty" Smith steal a pig from a neighbouring village. When Smith was questioned by the local constable

A constable is a person holding a particular office, most commonly in law enforcement. The office of constable can vary significantly in different jurisdictions. ''Constable'' is commonly the rank of an officer within a police service. Other peo ...

over the theft, he made a prophetic statement concerning Corder: "I'll be damned if he will not be hung some of these days." Corder had been sent to London in disgrace after his fraudulent sale of the pigs, but he was recalled to Polstead when his brother Thomas drowned attempting to cross a frozen pond.Brewers pp. 168–69 Corder's father and three brothers all died within eighteen months of each other and only he remained to run the farm with his mother.

Corder wished to keep his relationship with Marten a secret, but she gave birth to their child in 1827 at age 25 and was apparently keen that she and Corder should marry. The child died (later reports suggested that he/she may have been murdered), but Corder apparently still intended to marry Marten. That summer, in the presence of Marten's stepmother, Ann, Corder suggested that she meet him at the Red Barn, from where he proposed that they elope to Ipswich

Ipswich () is a port town and Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in Suffolk, England. It is the county town, and largest in Suffolk, followed by Lowestoft and Bury St Edmunds, and the third-largest population centre in East Anglia, ...

. He claimed that he had heard rumours that the parish officers were going to prosecute

A prosecutor is a legal representative of the prosecution in states with either the adversarial system, which is adopted in common law, or inquisitorial system, which is adopted in Civil law (legal system), civil law. The prosecution is the ...

Marten for having bastard children.

Corder initially suggested that they elope on the evening of Wednesday, 16 May 1827, but later decided to delay until the following evening. On 17 May, he was again delayed; his brother falling ill is mentioned as the reason in some sources, although most claim that all his brothers were dead by this time. On Friday, 18 May, Corder appeared at the Martens' cottage during the day and, according to Ann, told her stepdaughter that they had to leave at once, as he had heard that the local constable had obtained a warrant to prosecute her (no warrant had been obtained, but it is not known if Corder was lying or was mistaken). Marten was worried that she could not leave in broad daylight, but Corder told her that she should dress in men's clothing so as to avert suspicion, and he would carry her things to the Red Barn and change before they continued on to Ipswich.

Shortly after Corder left the Martens' cottage, Marten set out to meet him at the Red Barn, which was situated on Barnfield Hill, about half a mile from the cottage. This was the last time that she was seen alive. Corder also disappeared, but later turned up and claimed that Marten was in Ipswich, or some other place nearby, and that he could not yet bring her back as his wife for fear of provoking the anger of his friends and relatives. The pressure on Corder to produce his wife eventually forced him to leave the area. He wrote letters to Marten's family claiming that they were married and living on the

Shortly after Corder left the Martens' cottage, Marten set out to meet him at the Red Barn, which was situated on Barnfield Hill, about half a mile from the cottage. This was the last time that she was seen alive. Corder also disappeared, but later turned up and claimed that Marten was in Ipswich, or some other place nearby, and that he could not yet bring her back as his wife for fear of provoking the anger of his friends and relatives. The pressure on Corder to produce his wife eventually forced him to leave the area. He wrote letters to Marten's family claiming that they were married and living on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight (Help:IPA/English, /waɪt/ Help:Pronunciation respelling key, ''WYTE'') is an island off the south coast of England which, together with its surrounding uninhabited islets and Skerry, skerries, is also a ceremonial county. T ...

, and he gave various excuses for her lack of communication: she was unwell, she had hurt her hand or the letter must have been lost.

Suspicion continued to grow, and Marten's stepmother began talking of dreams that Maria had been murdered and buried in the Red Barn. On 19 April 1828, she persuaded her husband to go to the Red Barn and dig in one of the grain storage bins. He quickly uncovered the remains of his daughter buried in a sack. She was badly decomposed but still identifiable. An inquest

An inquest is a judicial inquiry in common law jurisdictions, particularly one held to determine the cause of a person's death. Conducted by a judge, jury, or government official, an inquest may or may not require an autopsy carried out by a cor ...

was carried out at the Cock Inn at Polstead (which still stands today), where Marten was formally identified by her sister (also named Ann) from some physical characteristics. Her hair and some clothing were recognisable, and she was known to be missing a tooth which was also absent from the jawbone of the corpse. Evidence was uncovered to implicate Corder in the crime: his green handkerchief was discovered around the body's neck.

Capture

Corder was easily discovered, as Ayres, the constable in Polstead, was able to obtain his old address from a friend. Ayres was assisted by James Lea, an officer of the London police who later led the investigation into "

Corder was easily discovered, as Ayres, the constable in Polstead, was able to obtain his old address from a friend. Ayres was assisted by James Lea, an officer of the London police who later led the investigation into "Spring-heeled Jack

Spring-heeled Jack was an entity in English folklore of the Victorian era. The first claimed sighting of Spring-heeled Jack was in 1837. Later sightings were reported all over the United Kingdom and were especially prevalent in suburban Lond ...

". They tracked Corder to Everley Grove House, a boarding house

A boarding house is a house (frequently a family home) in which lodging, lodgers renting, rent one or more rooms on a nightly basis and sometimes for extended periods of weeks, months, or years. The common parts of the house are maintained, and ...

for ladies in Brentford

Brentford is a suburban town in West (London sub region), West London, England and part of the London Borough of Hounslow. It lies at the confluence of the River Brent and the River Thames, Thames, west of Charing Cross.

Its economy has dive ...

. He was running the boarding house with his new wife Mary Moore, whom he had met through a lonely hearts advertisement that he had placed in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' (which had received more than 100 replies). Judith Flanders states in her 2011 book that Corder had also placed advertisements in the '' Morning Herald'' and ''The Sunday Times

''The Sunday Times'' is a British Sunday newspaper whose circulation makes it the largest in Britain's quality press market category. It was founded in 1821 as ''The New Observer''. It is published by Times Newspapers Ltd, a subsidiary of N ...

''. He received more than forty replies from the ''Morning Herald'' and 53 from ''The Sunday Times'' that he never picked up. These letters were subsequently published by George Foster in 1828.

Lea managed to gain entry under the pretext that he wished to board his daughter there, and he surprised Corder in the parlour. Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy (2 June 1840 – 11 January 1928) was an English novelist and poet. A Literary realism, Victorian realist in the tradition of George Eliot, he was influenced both in his novels and in his poetry by Romanticism, including the poetry ...

noted the ''Dorset County Chronicle''s report of his capture:

Lea took Corder to one side and informed him of the charges, but he denied all knowledge of both Marten and the crime. A search of the house uncovered a pair of pistol

A pistol is a type of handgun, characterised by a gun barrel, barrel with an integral chamber (firearms), chamber. The word "pistol" derives from the Middle French ''pistolet'' (), meaning a small gun or knife, and first appeared in the Englis ...

s supposedly bought on the day of the murder; some letters from a Mr. Gardener, which may have contained warnings about the discovery of the crime; and a passport

A passport is an official travel document issued by a government that certifies a person's identity and nationality for international travel. A passport allows its bearer to enter and temporarily reside in a foreign country, access local aid ...

from the French ambassador, evidence which suggested that Corder may have been preparing to flee.

Trial

Corder was taken back to Suffolk, where he was tried at Shire Hall,

Corder was taken back to Suffolk, where he was tried at Shire Hall, Bury St Edmunds

Bury St Edmunds (), commonly referred to locally as ''Bury,'' is a cathedral as well as market town and civil parish in the West Suffolk District, West Suffolk district, in the county of Suffolk, England.OS Explorer map 211: Bury St. Edmunds an ...

. The trial started on 7 August 1828, having been put back several days because of the interest which the case had generated. The hotels in Bury St Edmunds began to fill up from as early as 21 July, and admittance to the court was by ticket only because of the large numbers who wanted to view the trial. Despite this, the judge and court officials still had to push their way bodily through the crowds that had gathered around the door. The judge was the Chief Baron of the Exchequer

The Chief Baron of the Exchequer was the first "baron" (meaning judge) of the English Exchequer of Pleas. "In the absence of both the Treasurer of the Exchequer or First Lord of the Treasury, and the Chancellor of the Exchequer, it was he who pres ...

, William Alexander, who was unhappy with the coverage given to the case by the press "to the manifest detriment of the prisoner at the bar." ''The Times'', nevertheless, congratulated the public for showing good sense in aligning themselves against Corder, who entered a plea of not guilty.

Marten's exact cause of death could not be established. It was thought that a sharp instrument had been plunged into her eye socket, possibly Corder's short sword, but this wound could have been caused by her father's spade when he was exhuming the body. Strangulation

Strangling or strangulation is compression of the neck that may lead to unconsciousness or death by causing an increasingly hypoxic state in the brain by restricting the flow of oxygen through the trachea. Fatal strangulation typically occurs ...

could not be ruled out, as Corder's handkerchief had been discovered around her neck; to add to the confusion, the wounds to her body suggested that she had been shot. The indictment

An indictment ( ) is a formal accusation that a person has committed a crime. In jurisdictions that use the concept of felonies, the most serious criminal offense is a felony; jurisdictions that do not use that concept often use that of an ind ...

charged Corder with "murdering Maria Marten, by feloniously and wilfully shooting her with a pistol through the body, and likewise stabbing her with a dagger." To avoid any chance of a mistrial

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribunal, ...

, Corder was indicted

An indictment ( ) is a formal accusation that a person has committed a crime. In jurisdictions that use the concept of felonies, the most serious criminal offense is a felony; jurisdictions that do not use that concept often use that of an indi ...

on nine charges, including one of forgery.

Marten's stepmother was called to give evidence of the events of the day of Maria's disappearance and her later dreams. Thomas Marten then told the court how he had dug up his daughter, and Maria's 10-year-old brother George revealed that he had seen Corder with a loaded pistol before the alleged murder and had later seen him walking from the barn with a pickaxe

A pickaxe, pick-axe, or pick is a generally T-shaped hand tool used for Leverage (mechanics), prying. Its head is typically metal, attached perpendicularly to a longer handle, traditionally made of wood, occasionally metal, and increasingly ...

. Lea gave evidence concerning Corder's arrest and the objects found during the search of his house. The prosecution suggested that Corder had never wanted to marry Maria Marten, but that her knowledge of some of his criminal dealings had given her a hold over him, and that his theft of the money sent by her child's father had been a source of tension between them.

Corder then gave his own version of the events. He admitted to being in the barn with Marten, but said that he had left after they argued. He claimed that he heard a pistol shot while he was walking away, and that he ran back to the barn to find her dead with one of his pistols beside her. Corder pleaded with the jury to give him the benefit of the doubt, but after they retired, it took them only thirty-five minutes to return with a guilty verdict. Baron Alexander sentenced Corder to hang and afterwards be dissected:

Corder spent the next three days in prison agonising over whether to confess to the crime and make a clean breast of his sins before God. He finally confessed after entreaties from his wife, several meetings with the prison chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secular institution (such as a hospital, prison, military unit, intellige ...

and pleas from both his warder and John Orridge, the governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

of the prison. Corder strongly denied stabbing Marten, claiming that he had shot her in the eye after they argued.

Execution and dissection

On 11 August 1828, Corder was taken to the

On 11 August 1828, Corder was taken to the gallows

A gallows (or less precisely scaffold) is a frame or elevated beam, typically wooden, from which objects can be suspended or "weighed". Gallows were thus widely used to suspend public weighing scales for large and heavy objects such as sa ...

in Bury St Edmunds, apparently too weak to stand without support. He was hanged shortly before noon in front of a large crowd; one newspaper claimed that there were 7,000 spectators, another as many as 20,000. At the prompting of Orridge, just before the hood was drawn over his head, Corder said:

Corder's body was cut down after an hour by the hangman, John Foxton, who claimed his trousers and stockings according to his rights. The body was taken back to the courtroom at Shire Hall, where it was slit open along the abdomen to expose the muscles. The crowds were allowed to file past until six o'clock, when the doors were shut. According to the ''Norwich and Bury Post'', over 5,000 people queued to see the body.

The following day, the dissection and post-mortem

An autopsy (also referred to as post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death ...

were carried out in front of an audience of students from Cambridge University

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

and physicians. Reports circulated around Bury St Edmunds that a "galvanic battery" had been brought from Cambridge, and it is likely that the group experimented with galvanism

Galvanism is a term invented by the late 18th-century physicist and chemist Alessandro Volta to refer to the generation of electric current by chemical action. The term also came to refer to the discoveries of its namesake, Luigi Galvani, specifi ...

on the body; a battery was attached to Corder's limbs to demonstrate the contraction of the muscles. The sternum

The sternum (: sternums or sterna) or breastbone is a long flat bone located in the central part of the chest. It connects to the ribs via cartilage and forms the front of the rib cage, thus helping to protect the heart, lungs, and major bl ...

was opened and the internal organs examined. There was some discussion as to whether the cause of death was suffocation

Asphyxia or asphyxiation is a condition of deficient supply of oxygen to the body which arises from abnormal breathing. Asphyxia causes generalized hypoxia, which affects all the tissues and organs, some more rapidly than others. There are m ...

; it was reported that Corder's chest was seen to rise and fall for several minutes after he had dropped, and it was thought probable that pressure on the spinal cord

The spinal cord is a long, thin, tubular structure made up of nervous tissue that extends from the medulla oblongata in the lower brainstem to the lumbar region of the vertebral column (backbone) of vertebrate animals. The center of the spinal c ...

had killed him. The skeleton was to be reassembled after the dissection and it was not possible to examine the brain, so the surgeons contented themselves with a phrenological examination of Corder's skull. The skull was asserted to be profoundly developed in the areas of "secretiveness, acquisitiveness, destructiveness, philoprogenitiveness, and imitativeness" with little evidence of "benevolence or veneration".Gatrell pp. 256–57 The bust of Corder held by Moyse's Hall Museum in Bury St Edmunds is an original made by Childs of Bungay as a tool for the study of Corder's phrenology.

death mask

A death mask is a likeness (typically in wax or plaster cast) of a person's face after their death, usually made by taking a cast or impression from the corpse. Death masks may be mementos of the dead or be used for creation of portraits. The m ...

were made and replicas are held at Moyse's Hall Museum and in the dungeons of Norwich Castle

Norwich Castle is a medieval royal fortification in the city of Norwich, in the English county of Norfolk. William the Conqueror (1066–1087) ordered its construction in the aftermath of the Norman Conquest of England. The castle was used as a ...

. His widow advertised for sale the glasses he purportedly wore at the trial and a snuff box with Marten's likeness. Artefacts from the trial, some of which were in Corder's possession, are also held at the museum. Corder's skin was tanned by surgeon George Creed and used to bind an account of the murder. The book, together with another also part bound using Corder's skin, is on display at Moyse's Hall Museum. In 2025, a second book, was discovered at Moyse's Hall Museum; this copy, donated decades ago, utilized Corder's skin in the binding and the edges.

Corder's skeleton was reassembled, exhibited and used as a teaching aid in the West Suffolk Hospital. The skeleton was put on display in the Hunterian Museum

The Hunterian is a complex of museums located in and operated by the University of Glasgow in Glasgow, Scotland. It is the oldest museum in Scotland. It covers the Hunterian Museum, the Hunterian Art Gallery, the Mackintosh House, the Zoology M ...

in the Royal College of Surgeons of England

The Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCS England) is an independent professional body and registered charity that promotes and advances standards of surgery, surgical care for patients, and regulates surgery and dentistry in England and Wa ...

, where it hung beside that of Jonathan Wild

Jonathan Wild, also spelled Wilde (1682 or 1683 – 24 May 1725), was an English thief-taker and a major figure in London's criminal underworld, notable for operating on both sides of the law, posing as a public-spirited vigilante entitled th ...

. In 2004, Corder's bones were removed and cremated

Cremation is a method of Disposal of human corpses, final disposition of a corpse through Combustion, burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India, Nepal, and ...

.

Rumours

After the trial, doubts were raised about both the story of Ann Marten's dreams and the fate of Corder and Maria Marten's child. Ann was only a year older than Maria, and it was suggested that she and Corder had been having an affair and that the two had planned the murder to dispose of Maria so that it could continue without hindrance. Ann's dreams had started only a few days after Corder married Moore, and it was suggested that jealousy was the motive for revealing the body's resting place and that the dreams were a simple subterfuge. Further rumours circulated about the death of Corder and Marten's child. Both claimed that they had taken their dead child to be buried in Sudbury, but no records of this could be discovered and no trace was found of the child's burial site. In his written confession, Corder admitted that he and Marten had argued on the day of the murder over the possibility of the burial site being discovered. In 1967,Donald McCormick

George Donald King McCormick (11 December 1911 – 2 January 1998) was a British Journalism, journalist and popular historian, who also wrote under the pseudonym Richard Deacon.

After working for Naval Intelligence during the Second World War, ...

wrote ''The Red Barn Mystery'', which brought out a connection between Corder and forger and supposed serial killer

A serial killer (also called a serial murderer) is a person who murders three or more people,An offender can be anyone:

*

*

*

*

* (This source only requires two people) with the killings taking place over a significant period of time in separat ...

Thomas Griffiths Wainewright

Thomas Griffiths Wainewright (October 179417 August 1847) was an English artist, author and suspected serial killer. He gained a reputation as a profligate and a dandy, and in 1837, was transported to the penal colony of Van Diemen's Land (now th ...

when the former was in London. According to McCormick, Caroline Palmer, an actress who was appearing frequently in a melodrama

A melodrama is a Drama, dramatic work in which plot, typically sensationalized for a strong emotional appeal, takes precedence over detailed characterization. Melodrama is "an exaggerated version of drama". Melodramas typically concentrate on ...

based on the Red Barn case and had been researching the murder, concluded that Corder may have not killed Marten, but that a local gypsy

{{Infobox ethnic group

, group = Romani people

, image =

, image_caption =

, flag = Roma flag.svg

, flag_caption = Romani flag created in 1933 and accepted at the 1971 World Romani Congress

, po ...

woman might have been the killer. However, McCormick's research has been brought into question on other police- and crime-related stories, and this information has not been generally accepted.

Popular interest

The case had all the elements to ignite a fervent popular interest: the wicked squire and the poor girl, the proverbial murder scene, the supernatural element of the stepmother's prophetic dreams, the detective work by Ayres and Lea (who later became the single character "Pharos Lee" in stage versions of the events) and Corder's new life which was the result of a lonely hearts advertisement. As a consequence, the case created its own small industry. Plays were being performed while Corder was still awaiting trial, and an anonymous author published a melodramatic version of the murder after the execution, a precursor of the Newgate novels which quickly became best-sellers. The Red Barn Murder was a popular subject, along with the story of

Plays were being performed while Corder was still awaiting trial, and an anonymous author published a melodramatic version of the murder after the execution, a precursor of the Newgate novels which quickly became best-sellers. The Red Barn Murder was a popular subject, along with the story of Jack Sheppard

John Sheppard (4 March 1702 – 16 November 1724), nicknamed "Honest Jack", was a notorious English thief and prison escapee of early 18th-century London.

Born into a poor family, he was apprenticed as a carpenter, but began committing thef ...

and other highwaymen, thieves and murderers, for penny gaffs, cheap plays performed in the back rooms of public houses. James Catnach sold more than a million broadsides (sensationalist

In journalism and mass media, sensationalism is a type of editorial tactic. Events and topics in news stories are selected and worded to excite the greatest number of readers and viewers. This style of news reporting encourages biased or emotiona ...

single sheet newspapers) which gave details of Corder's confession and execution, and included a sentimental ballad

A ballad is a form of verse, often a narrative set to music. Ballads were particularly characteristic of the popular poetry and song of Great Britain and Ireland from the Late Middle Ages until the 19th century. They were widely used across Eur ...

supposedly written by Corder himself (though more likely to have been the work of Catnach or somebody in his employ). It was one of at least five ballads about the crime that appeared directly following the execution.

Many different versions of the events were set down and distributed due to the excitement around the trial and the public demand for entertainments based on the murder, making it hard for modern readers to discern fact from melodramatic embellishment. Good official records exist from the trial, and the best record of the events surrounding the case is generally considered to be that of James Curtis, a journalist who spent time with Corder and two weeks in Polstead interviewing those concerned. He was apparently so connected with the case that a newspaper artist who was asked to produce a picture of the accused man drew a likeness of Curtis instead of Corder.

Pieces of the rope which was used to hang Corder sold for a

Pieces of the rope which was used to hang Corder sold for a guinea

Guinea, officially the Republic of Guinea, is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Guinea-Bissau to the northwest, Senegal to the north, Mali to the northeast, Côte d'Ivoire to the southeast, and Sier ...

each. Part of his scalp with an ear still attached was displayed in a shop on Oxford Street

Oxford Street is a major road in the City of Westminster in the West End of London, running between Marble Arch and Tottenham Court Road via Oxford Circus. It marks the notional boundary between the areas of Fitzrovia and Marylebone to t ...

. A lock of Marten's hair sold for two guineas. Polstead became a tourist venue, with visitors travelling from as far afield as Ireland;Mackay p. 700 Curtis estimated that 200,000 people visited Polstead in 1828 alone. The Red Barn and the Martens' cottage excited particular interest. The barn was stripped for souvenir

A souvenir ( French for 'a remembrance or memory'), memento, keepsake, or token of remembrance is an object a person acquires for the memories the owner associates with it. A souvenir can be any object that can be collected or purchased and trans ...

s, down to the planks being removed from the sides, broken up and sold as toothpicks. It was slated to be demolished after the trial, but it was left standing and eventually burned down in 1842. Even Marten's gravestone in the churchyard of St Mary's, Polstead, was eventually chipped away to nothing by souvenir hunters; only a sign on the shed now marks the approximate place where it stood, although her name is given to Marten's Lane in the village. Pottery models and sketches were sold and songs were composed, including one quoted in the Vaughan Williams

Ralph Vaughan Williams ( ; 12 October 1872– 26 August 1958) was an English composer. His works include operas, ballets, chamber music, secular and religious vocal pieces and orchestral compositions including nine symphonies, written over ...

opera '' Hugh the Drover'' and '' Five Variants of Dives and Lazarus''.

Corder's skeleton was put on display in a glass case in the West Suffolk Hospital, and apparently was rigged with a mechanism that made its arm point to the collection box when approached. Eventually, the skull was removed by Dr. John Kilner, who wanted to add it to his extensive collection of Red Barn memorabilia. After a series of unfortunate events, Kilner became convinced that the skull was cursed and handed it on to a friend named Hopkins. Further disasters plagued both men, and they finally paid for the skull to be given a Christian burial in an attempt to lift the supposed curse.

Interest in the case did not quickly fade. The play ''Maria Marten, or The Murder in the Red Barn'' existed in various anonymous versions; it was a sensational hit throughout the mid-19th century and may have been the most performed play of the time. Victorian fairground peep show

A peep show, peepshow, or, a peep booth is a presentation of a live sex show or pornographic film which is viewed through a viewing slot.

Several historical media provided voyeuristic entertainment through hidden erotic imagery. Before the devel ...

s were forced to add extra apertures for their viewers when exhibiting their shows of the murder. The plays of the Victorian era tended to portray Corder as a cold-blooded monster and Marten as the innocent whom he preyed upon; her reputation and her children by other fathers were airbrushed out, and Corder was made into an older man.Richards p. 136 Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

published an account of the murder in his magazine ''All the Year Round

''All the Year Round'' was a British weekly literary magazine founded and owned by Charles Dickens, published between 1859 and 1895 throughout the United Kingdom. Edited by Dickens, it was the direct successor to his previous publication '' Ho ...

'' after initially rejecting it because he felt the story to be too well known and the account of the stepmother's dreams rather far-fetched.

Folk song

The folk song "Maria Martin" or "The Murder of Maria Martin" ( Roud 215) tells the story of the murder. TheLincolnshire

Lincolnshire (), abbreviated ''Lincs'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands and Yorkshire and the Humber regions of England. It is bordered by the East Riding of Yorkshire across the Humber estuary to th ...

folk singer Joseph Taylor sang a fragment of the song to Percy Grainger

Percy Aldridge Grainger (born George Percy Grainger; 8 July 188220 February 1961) was an Australian-born composer, arranger and pianist who moved to the United States in 1914 and became an American citizen in 1918. In the course of a long and ...

in 1908. Grainger recorded the performance on a wax cylinder

Phonograph cylinders (also referred to as Edison cylinders after its creator Thomas Edison) are the earliest commercial medium for recording and reproducing sound. Commonly known simply as "records" in their heyday (c. 1896–1916), a name which ...

, which has been digitised and can be heard via the British Library Sound Archive

The British Library Sound Archive, formerly the British Institute of Recorded Sound; also known as the National Sound Archive (NSA), in London, England is among the largest collections of recorded sound in the world, including music, spoken word ...

website. Taylor sings the following lyrics, to the tune of Dives and Lazarus:

:''Several other versions of the song were recorded, including one from Billy List of Brundish, Suffolk, which can also be heard on the British Library Sound Archive website. These recordings appear to be based on popular versions printed on broadsides in the mid-19th century.'"If you'll meet me at the Red Barn as sure as I have life'' :''I will take you to Ipswich Town and there make you my wife."'' :''This lad went home and fetched his gun, his pick-axe and his spade.'' :''He went unto the Red Barn and there he dug her grave.'' :''With her heart so light she thought no harm, to meet her love did go'' :''He murdered her all in the barn and he laid her body low''

Twentieth century

Public fascination continued into the 20th century with five film versions, including '' Maria Marten, or The Murder in the Red Barn'' (1935) starring Tod Slaughter, and theBBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

drama ''Maria Marten'' (1980), with Pippa Guard in the title role. The story has been dramatised for radio a number of times, including two radio dramas by Slaughter (one broadcast on the BBC Regional Programme

The BBC Regional Programme was a radio service which was on the air from 9 March 1930 – replacing a number of earlier BBC local stations between 1922 and 1924 – until 1 September 1939 when it was subsumed into the BBC Home Service, two day ...

in 1934, and one broadcast on the BBC Home Service

The BBC Home Service was a national and regional radio station that broadcast from 1939 until 1967, when it was replaced by BBC Radio 4.

History

1922–1939: Interwar period

Between the early 1920s and the outbreak of World War II, the BBC ...

in 1939), a fictionalised account of the murder produced in 1953 for the CBS

CBS Broadcasting Inc., commonly shortened to CBS (an abbreviation of its original name, Columbia Broadcasting System), is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the CBS Entertainme ...

radio series ''Crime Classics

''Crime Classics'' is a United States radio docudrama which aired as a sustaining series over CBS Radio from June 15, 1953, to June 30, 1954.

Production

Produced and directed by radio actor and director Elliott Lewis, the program was a hist ...

'', entitled "The Killing Story of William Corder and the Farmer's Daughter" and "Hanging Fire", a BBC ''Monday Play'' by Lisa Evans broadcast in 1990 telling the story of the events leading up to the murder as seen through the eyes of Marten's sister Ann. Christopher Bond wrote ''The Mysterie of Maria Marten and the Murder in the Red Barn'' in 1991, a melodramatic stage version with some political and folk-tale elements. The folk singer Shirley Collins

Shirley Elizabeth Collins MBE (born 5 July 1935) is an English folk singer who was a significant contributor to the British Folk Revival of the 1960s and 1970s. She often performed and recorded with her sister Dolly, whose accompaniment on ...

and the Albion Country Band recorded a song in 1971 entitled "Murder of Maria Marten" on their album '' No Roses''. A part of the song is performed by Florence Pugh

Florence Pugh ( ; born 3 January 1996) is an English actress. Her accolades include a British Independent Film Award, in addition to nominations for an Academy Award and three BAFTA Awards.

After making her acting debut in the drama film ' ...

in the 2018 television dramatisation of John le Carré

David John Moore Cornwell (19 October 193112 December 2020), better known by his pen name John le Carré ( ), was a British author, best known for his espionage novels, many of which were successfully adapted for film or television. A "sophist ...

's '' The Little Drummer Girl''.

See also

* Greenbrier Ghost, an American murder case in which the murderer was allegedly revealed by the victim's ghost *Anthropodermic bibliopegy

Anthropodermic bibliopegy is the practice of binding books in human skin. , The Anthropodermic Book Project has examined 31 out of 50 books in public institutions supposed to have anthropodermic bindings, of which 18 have been confirmed as huma ...

Notes

a. Moore's first name is occasionally reported as Maria but an inscription in Corder's journal and later reports make it clear she was called Mary. The initial newspaper reports said that she had seen Corder's advertisement in a pastry shop window. Whether this is true or not is unknown, but Corder had certainly received replies for his advertisement in ''The Times'', a number of which can be found in Curtis' account of the case. b. The account of the case bound in Corder's tanned skin is held at Moyse's Hall Museum and contains a hand-written account of a witticism on the inside cover: on the night of the execution, during a performance of ''Macbeth

''The Tragedy of Macbeth'', often shortened to ''Macbeth'' (), is a tragedy by William Shakespeare, estimated to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the physically violent and damaging psychological effects of political ambiti ...

'' at Drury Lane, when the line "Is execution done on Cawdor?" was spoken, a man shouted from the gallery "Yes! – He was hung this morning at Bury"

c. Accounts of how many were sold vary but are consistently quoted as either 1,160,000 or 1,600,000. Catnach claimed it had sold over 1,650,000.

d. In November 2007 a report of a fire that nearly destroyed Marten's cottage was on the front page of the ''East Anglian Daily Times''. Firefighters saved 80% of the thatched roof at Marten's former home after a chimney fire threatened the "iconic Suffolk cottage", now run as a bed and breakfast

A bed and breakfast (typically shortened to B&B or BnB) is a small lodging establishment that offers overnight accommodation and breakfast. In addition, a B&B sometimes has the hosts living in the house.

''Bed and breakfast'' is also used to ...

.

e. In Britain the script was submitted to the British Board of Film Censors who passed it on the condition that the execution scene was cut. The scene was filmed anyway, but the Board demanded it be removed before the film was passed. In the U.S., scenes emphasising Maria's pregnancy, and featuring the words ''slut'' and ''wench'' were cut, and the scene of her burial shortened. Virginia and Ohio made further cuts to the versions they approved for distribution.Slide p. 103

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

*Account of the case in The Newgate Calendar

{{DEFAULTSORT:Red Barn Murder 1827 in England 1827 murders in the United Kingdom 19th century in Suffolk Violence against women in England Murder in Suffolk Polstead Murder trials in the United Kingdom 19th-century trials Uxoricides Deaths by firearm in England