Reagan's Foreign Policies on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Although Pakistan was ruled by

Although Pakistan was ruled by

Upon becoming president, Reagan moved quickly to undermine Soviet efforts to support the government of Afghanistan, as the Soviet Army had entered that country at Kabul's request in 1979.

Islamic mujahideen guerrillas were covertly supported and trained, and backed in their

Upon becoming president, Reagan moved quickly to undermine Soviet efforts to support the government of Afghanistan, as the Soviet Army had entered that country at Kabul's request in 1979.

Islamic mujahideen guerrillas were covertly supported and trained, and backed in their

The primary U.S. interest in the

The primary U.S. interest in the

Reagan had close friendships with many political leaders across the globe, especially Margaret Thatcher in Britain, and

Reagan had close friendships with many political leaders across the globe, especially Margaret Thatcher in Britain, and

When the

When the

The attempts of certain members of the White House national security staff to circumvent Congressional proscription of covert military aid to the Contras ultimately resulted in the Iran-Contra Affair.

Two members of administration, National Security Advisor (United States), National Security Advisor John Poindexter and Col. Oliver North worked through CIA and military channels to sell arms to the Iranian government and give the profits to the contra guerillas in Nicaragua, who were engaged in a bloody civil war. Both actions were contrary to acts of United States Congress, Congress. Reagan professed ignorance of the plot, but admitted that he had supported the initial sale of arms to Iran, on the grounds that such sales were supposed to help secure the release of Americans being held hostage by the Iranian-backed Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Reagan quickly called for the appointment of an Office of the Independent Counsel, Independent Counsel to investigate the wider scandal; the resulting Tower Commission report found that the President was guilty of the scandal, only in that his lax control of his own staff resulted in the arms sales. (The report also revealed that U.S. officials helped Khomeini identify and purge communists within the Iranian government.) The failure of these scandals to have a lasting impact on Reagan's reputation led Representative Patricia Schroeder to dub him the "Teflon President", a term that has been occasionally attached to later Presidents and their scandals. Ten officials in the Reagan administration were convicted, and others were forced to resign. Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger was indicted for perjury and later received a presidential pardon from George H.W. Bush, days before the trial was to begin. In 2006, historians ranked the Iran-Contra affair as the ninth-worst mistake by a U.S. president.

The attempts of certain members of the White House national security staff to circumvent Congressional proscription of covert military aid to the Contras ultimately resulted in the Iran-Contra Affair.

Two members of administration, National Security Advisor (United States), National Security Advisor John Poindexter and Col. Oliver North worked through CIA and military channels to sell arms to the Iranian government and give the profits to the contra guerillas in Nicaragua, who were engaged in a bloody civil war. Both actions were contrary to acts of United States Congress, Congress. Reagan professed ignorance of the plot, but admitted that he had supported the initial sale of arms to Iran, on the grounds that such sales were supposed to help secure the release of Americans being held hostage by the Iranian-backed Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Reagan quickly called for the appointment of an Office of the Independent Counsel, Independent Counsel to investigate the wider scandal; the resulting Tower Commission report found that the President was guilty of the scandal, only in that his lax control of his own staff resulted in the arms sales. (The report also revealed that U.S. officials helped Khomeini identify and purge communists within the Iranian government.) The failure of these scandals to have a lasting impact on Reagan's reputation led Representative Patricia Schroeder to dub him the "Teflon President", a term that has been occasionally attached to later Presidents and their scandals. Ten officials in the Reagan administration were convicted, and others were forced to resign. Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger was indicted for perjury and later received a presidential pardon from George H.W. Bush, days before the trial was to begin. In 2006, historians ranked the Iran-Contra affair as the ninth-worst mistake by a U.S. president.

The Reagan administration strengthened the alliance with Saudi Arabia as it kept the commitment to defend the Kingdom. The "special relationship" between Riyadh and Washington really began to flourish after 1981, as the Saudis turned to the Reagan administration to safeguard their orders of advanced weapons. Saudi Arabia was part of the

The Reagan administration strengthened the alliance with Saudi Arabia as it kept the commitment to defend the Kingdom. The "special relationship" between Riyadh and Washington really began to flourish after 1981, as the Saudis turned to the Reagan administration to safeguard their orders of advanced weapons. Saudi Arabia was part of the

"Former Leader of Guatemala Is Guilty of Genocide Against Mayan Group"

''The New York Times''. (Retrieved 5-20-13). In the case of the Falklands War in 1982, the Reagan administration faced competing obligations to both sides, bound to the United Kingdom as a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and to Argentina by the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance (the "Rio Pact"). However, the North Atlantic Treaty only obliges the signatories to support each other if an attack occurred in Europe or North America north of the Tropic of Cancer, and the Rio Pact only obliges the U.S. to intervene if the territory of one of the signatories was attacked—the UK never attacked Argentine territory. As the conflict developed, the Reagan administration tilted its support towards Britain.

Undermining the hostile regime in Nicaragua was a high priority for Reagan. He described Nicaragua under the Sandinista National Liberation Front as "a Soviet ally on the American mainland". In a public address in March 1986, Reagan stated that "Using Nicaragua as a base, the Soviets and Cubans can become the dominant power in the crucial corridor between North and South America."

The Reagan administration lent logistical, financial, and military United States and state-sponsored terrorism#The Contras, support to the Contras, based in neighboring Honduras, who waged a guerrilla warfare, guerrilla insurgency in an effort to topple the Sandinista government of Nicaragua (which was headed by Daniel Ortega). This support was funneled through the CIA to the rebels, and continued right through Reagan's period in office. The scorched earth tactics of the Contras were condemned for their brutality by several historians.

In 1983, the

Undermining the hostile regime in Nicaragua was a high priority for Reagan. He described Nicaragua under the Sandinista National Liberation Front as "a Soviet ally on the American mainland". In a public address in March 1986, Reagan stated that "Using Nicaragua as a base, the Soviets and Cubans can become the dominant power in the crucial corridor between North and South America."

The Reagan administration lent logistical, financial, and military United States and state-sponsored terrorism#The Contras, support to the Contras, based in neighboring Honduras, who waged a guerrilla warfare, guerrilla insurgency in an effort to topple the Sandinista government of Nicaragua (which was headed by Daniel Ortega). This support was funneled through the CIA to the rebels, and continued right through Reagan's period in office. The scorched earth tactics of the Contras were condemned for their brutality by several historians.

In 1983, the

BBC, March 24, 2002. Retrieved July 16, 2008. Reagan's policy has been criticized due to the human rights abuses proven repeatedly to be perpetrated by El Salvadoran security force with

United States invasion of Grenada, The invasion of the Caribbean island Grenada in 1983, ordered by President Reagan, was the first major foreign event of the administration, as well as the first major operation conducted by the military since the Vietnam War. President Reagan justified the invasion by claiming that the cooperation of the island with communist Cuba posed a threat to the United States, and stated the invasion was a response to the illegal overthrow and execution of Grenadian Prime Minister Maurice Bishop, himself a communist, by another faction of communists within his government. After the start of planning for the invasion, the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) appealed to the United States, Barbados, and Jamaica, among other nations, for assistance. The US invasion was poorly done, for it took over 10,000 U.S. forces eight days of fighting, suffering nineteen fatalities and 116 injuries, fighting against several hundred lightly armed policemen and Cuban construction workers. Governor-General of Grenada, Grenada's Governor-General, Paul Scoon, announced the resumption of the constitution and appointed a new government, and U.S. forces withdrew that December.

While the invasion enjoyed public support in the United States it was criticized by the United Kingdom, Canada and the United Nations General Assembly as "a flagrant violation of international law". The date of the invasion is now a national holiday in Grenada, called Thanksgiving Day#Grenada, Thanksgiving Day.

United States invasion of Grenada, The invasion of the Caribbean island Grenada in 1983, ordered by President Reagan, was the first major foreign event of the administration, as well as the first major operation conducted by the military since the Vietnam War. President Reagan justified the invasion by claiming that the cooperation of the island with communist Cuba posed a threat to the United States, and stated the invasion was a response to the illegal overthrow and execution of Grenadian Prime Minister Maurice Bishop, himself a communist, by another faction of communists within his government. After the start of planning for the invasion, the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) appealed to the United States, Barbados, and Jamaica, among other nations, for assistance. The US invasion was poorly done, for it took over 10,000 U.S. forces eight days of fighting, suffering nineteen fatalities and 116 injuries, fighting against several hundred lightly armed policemen and Cuban construction workers. Governor-General of Grenada, Grenada's Governor-General, Paul Scoon, announced the resumption of the constitution and appointed a new government, and U.S. forces withdrew that December.

While the invasion enjoyed public support in the United States it was criticized by the United Kingdom, Canada and the United Nations General Assembly as "a flagrant violation of international law". The date of the invasion is now a national holiday in Grenada, called Thanksgiving Day#Grenada, Thanksgiving Day.

At first glance, it appeared that the U.S. had military treaty obligations to both parties in the war, bound to the United Kingdom as a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and to Argentina by the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance, known as the "Rio Pact". However, the North Atlantic Treaty only obliges the signatories to support if the attack occurs in Europe or North America north of the Tropic of Cancer, and the Rio Pact only obliges the U.S. to intervene if one of the adherents to the treaty is attacked—the UK never attacked Argentina, only Argentine forces on British territory.

In March, Secretary of State Alexander Haig directed the US Ambassador to Argentina Harry W. Shlaudeman to warn the Argentine government away from any invasion. President Reagan requested assurances from Galtieri against an invasion and offered the services of his vice president,

At first glance, it appeared that the U.S. had military treaty obligations to both parties in the war, bound to the United Kingdom as a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and to Argentina by the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance, known as the "Rio Pact". However, the North Atlantic Treaty only obliges the signatories to support if the attack occurs in Europe or North America north of the Tropic of Cancer, and the Rio Pact only obliges the U.S. to intervene if one of the adherents to the treaty is attacked—the UK never attacked Argentina, only Argentine forces on British territory.

In March, Secretary of State Alexander Haig directed the US Ambassador to Argentina Harry W. Shlaudeman to warn the Argentine government away from any invasion. President Reagan requested assurances from Galtieri against an invasion and offered the services of his vice president,

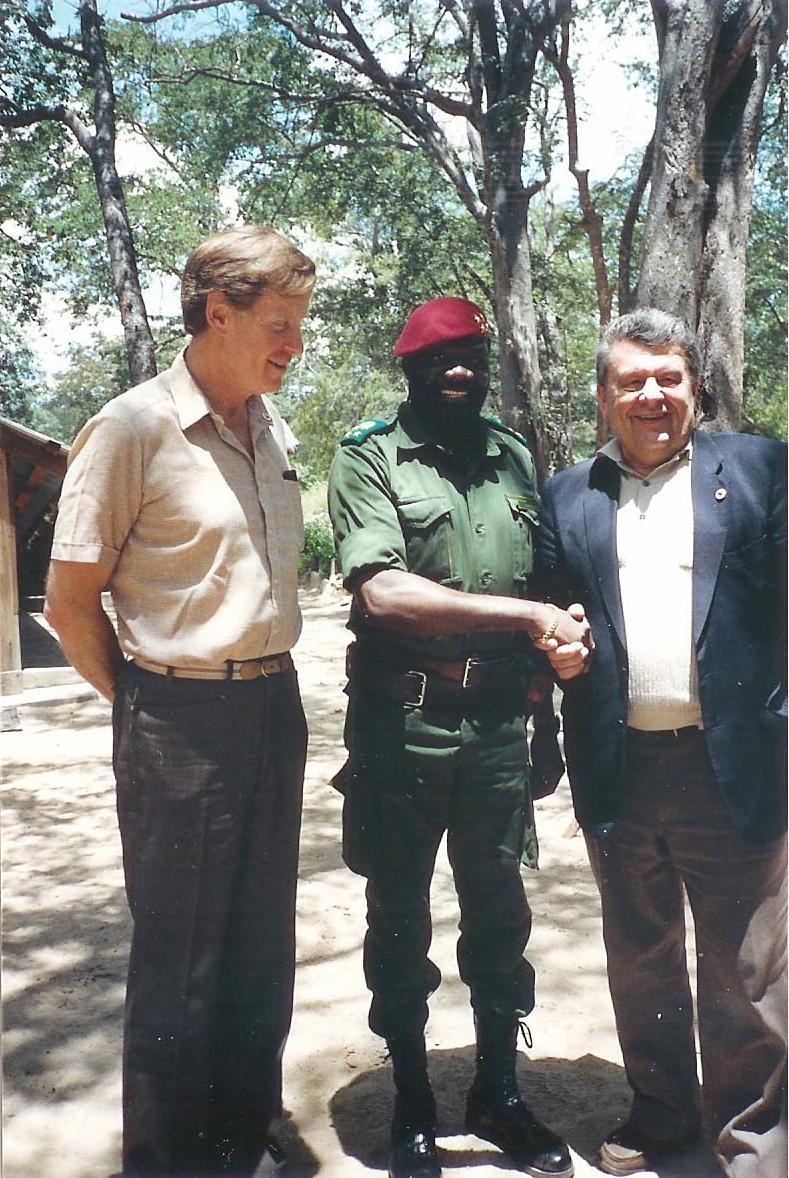

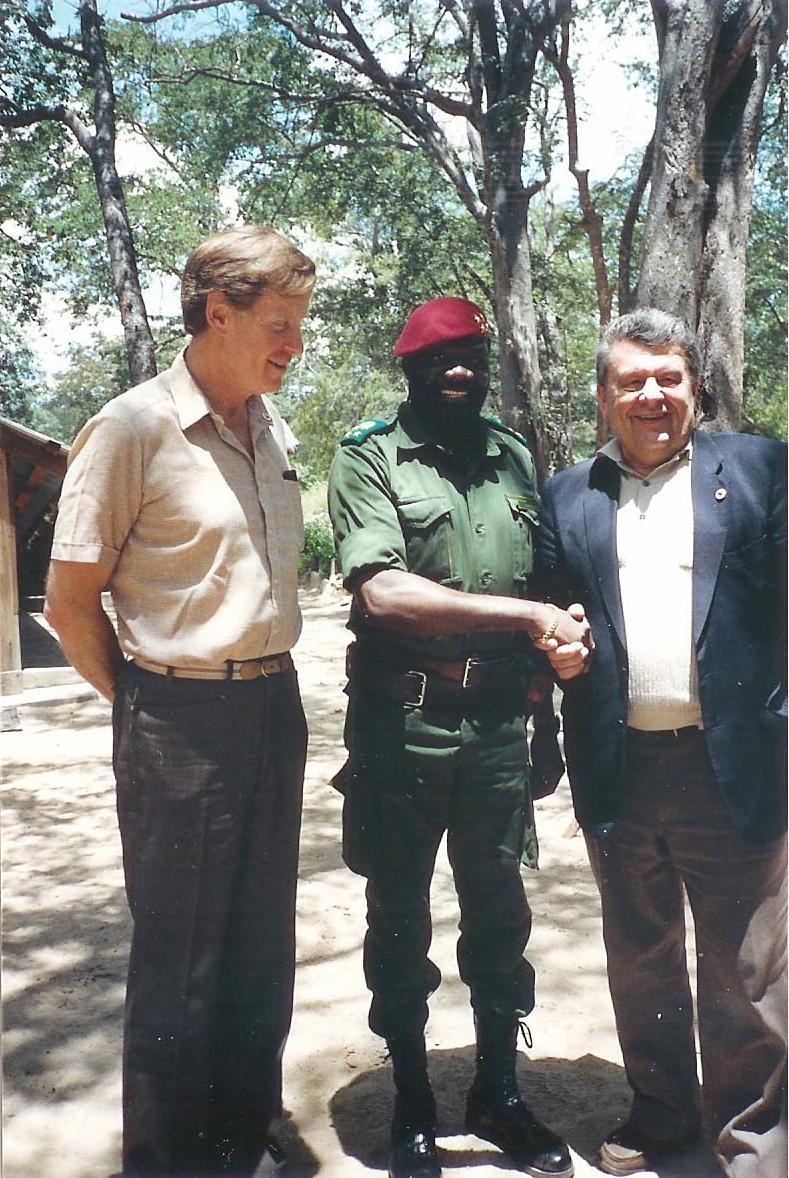

War between western supported movements and the communist MPLA government in Angola, and Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces, Cuban and South African Defence Force, South African military intervention there, led to a decades-long Angolan Civil War, civil war that cost up to one million lives. The Reagan administration offered covert aid to the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), a group of anti-communist and pro capitalist fighters led by Jonas Savimbi, whose attacks were backed by South Africa and the US. Dr. Peter Hammond, a Christian missionary who lived in Angola at the time, recalled:

Human rights observers have accused the MPLA of "genocidal atrocities", "systematic extermination", "war crimes" and "crimes against humanity". The MPLA held blatantly rigged elections in 1992, which were rejected by eight opposition parties. An official observer wrote that there was little UN supervision, that 500,000 UNITA voters were disenfranchised and that there were 100 clandestine polling stations. UNITA sent peace negotiators to the capital, where the MPLA murdered them, along with 20,000 UNITA members. Savimbi was still ready to continue the elections. The MPLA then massacred tens of thousands of UNITA and National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) voters nationwide.

Savimbi was strongly supported by

War between western supported movements and the communist MPLA government in Angola, and Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces, Cuban and South African Defence Force, South African military intervention there, led to a decades-long Angolan Civil War, civil war that cost up to one million lives. The Reagan administration offered covert aid to the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), a group of anti-communist and pro capitalist fighters led by Jonas Savimbi, whose attacks were backed by South Africa and the US. Dr. Peter Hammond, a Christian missionary who lived in Angola at the time, recalled:

Human rights observers have accused the MPLA of "genocidal atrocities", "systematic extermination", "war crimes" and "crimes against humanity". The MPLA held blatantly rigged elections in 1992, which were rejected by eight opposition parties. An official observer wrote that there was little UN supervision, that 500,000 UNITA voters were disenfranchised and that there were 100 clandestine polling stations. UNITA sent peace negotiators to the capital, where the MPLA murdered them, along with 20,000 UNITA members. Savimbi was still ready to continue the elections. The MPLA then massacred tens of thousands of UNITA and National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) voters nationwide.

Savimbi was strongly supported by

The Hill (newspaper), The Hill, April 14, 2017 Previously, the U.S. spent over a billion dollars in humanitarian relief funding for the crisis starting in 1918 and also recognized the Armenian "genocide" in a statement to the International Court of Justice in 1951.

''Los Angeles Times'', April 12, 1985

''The New York Times'', May 6, 1985 The Kolmeshohe cemetery included graves of 49 Nazi Waffen-SS soldiers. Reagan and West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl planned to lay a wreath in the cemetery "in a spirit of reconciliation, in a spirit of forty years of peace, in a spirit of economic and military compatibility.""Ronald Reagan Administration: The Bitburg Controversy"

Jewish Virtual Library, 2008 Reagan had declined to visit any concentration camps during the visit because he thought it would "send the wrong signal" to the German people and was "unnecessary". This led to protest and condemnation by Jewish groups, veterans, United States Congress, Congress, and the Anti-Defamation League. Politicians, veterans, and Jewish demonstrators from the United States, France, Britain, West Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Israel, and other countries protested the Reagan's visit. Due to the Bitburg controversy, Reagan did end up visiting the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp during his trip. During the visit Reagan honored Anne Frank but also stated, "The evil world of Nazism turned all values upside down. Nevertheless, we can mourn the German war dead today as human beings, crushed by a vicious ideology." Leading up to the visit, U.S. president

''The Washington Post'', April 29, 1985 ''The New York Times'' reported in 1985, "White House aides have acknowledged that (Reagan's) Bitburg visit is probably the biggest fiasco of Mr. Reagan's Presidency." They described Reagan's decision to go through with the Bitburg visit was a "blunder", and one of the few times that Reagan lost a confrontation in the court of public opinion.

Jewish Telegraphic Agency, April 25, 1985 The convention was created "in response to the Nazi atrocities against the Jews". The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and the textbook of Oxford University Human Rights explained the sudden ratification as a direct response to the Bitburg controversy and an attempt for Reagan to "make amends" for the visit."Human Rights: Politics and Practice (3rd edn)"

Oxford University Press, 2016"Turning a Blind Eye by Laura Secor"

''The New York Times'', April 14, 2002 This "gesture of concession to public outrage" was undermined by "a number of provisions immunizing the U.S. against the possibility of ever being charged with genocide.""The United States and the Genocide Convention" by William Korey

Cambridge University Press, September 28, 2012 The U.S. ratification included so many treaty reservations "that the convention would not meaningfully bind the United States to much of anything" and the ratification was described as substantially "meaningless". The vote to ratify the treaty in the Senate was 83 in favor, 11 against and 6 not voting. The U.S. was the 98th country to ratify the Genocide Convention. The U.S. had previously refused to become a party from 1948 to 1985 because it was "nervous about its own record on race": U.S. Southern senators worried "that Jim Crow laws could constitute genocide under the Convention".

Yale Journal of International Law, April 14, 2002 Then on January 18, 1985, the United States notified the ICJ that it would no longer participate in the Nicaragua v. United States proceedings. On June 27, 1986, the ICJ ruled that U.S. support to the contras in Nicaragua was illegal, and demanded that the U.S. pay reparations to the Sandinistas. Reagan's State Department said "the United States rejected the Court's verdict, and said the ICJ was not equipped to judge complex international military issues." Finally, and most significantly, on October 7, 1985, the United States terminated its acceptance of the ICJ's compulsory jurisdiction. The decision was critiqued by ''The New York Times'' as "damaging our foreign policy interests, undermining our legitimacy as a voice for morality, eroding the rule of law in international relations.""Reagan's World-Court Error"

by Paul Simon (politician), Paul Simon. ''The New York Times'', October 16, 1985

online

* Brown, Archie. ''The Human Factor: Gorbachev, Reagan and Thatcher, and the End of the Cold War'' (Oxford UP, 2020). * Busch, Andrew E. "Ronald Reagan and the Defeat of the Soviet Empire" in ''Presidential Studies Quarterly''. 27#3 (1997). pp. 451+ * Cohen, Stephen Philip. "The Reagan Administration and India". in ''The Hope and the Reality'' (Routledge, 2019) pp. 139–153. * Coleman, Bradley Lynn, and Kyle Longley, eds. ''Reagan and the World: Leadership and National Security, 1981–1989'' (2017) 13 essays by scholars

excerpt

* Crandall, Russell. ''The Salvador Option: The United States in El Salvador, 1977–1992'' (Cambridge University Press, 2016). * Downing, Taylor. ''1983: Reagan, Andropov, and a World on the Brink'' (Hachette UK, 2018). * Dobson, Alan P. "The Reagan administration, economic warfare, and starting to close down the cold war". ''Diplomatic History'' 29.3 (2005): 531–556. * Dujmovic, Nicholas. "Reagan, Intelligence, Casey, and the CIA: A Reappraisal", ''International Journal of Intelligence & Counterintelligence'' (2013) 26#1 pp. 1–30. * Draper, Theodore. '' A Very Thin Line: The Iran-Contra Affair'' (1991). * Dunn, Peter M. ed. ''American Intervention In Grenada: The Implications Of Operation "Urgent Fury"'' (2019) * Esno, Tyler. "Reagan's Economic War on the Soviet Union", ''Diplomatic History'' (2018) 42#2 281–304

Reagan’s Economic War on the Soviet Union

* Fitzgerald, Frances. ''Way Out There in the Blue: Reagan, Star Wars and the End of the Cold War''. political history of S.D.I. (2000). * Ford, Christopher A. and Rosenberg, David A. "The Naval Intelligence Underpinnings of Reagan's Maritime Strategy". ''Journal of Strategic Studies'' (2): 379–409. Argues Reagan applied naval might against Soviet weaknesses. It involved a large naval buildup and aggressive exercises near the USSR; it targeted their strategic missile submarines. American intelligence helped Washington to revise its strategy of military operations. * Gaddis, John Lewis. ''Strategies of Containment: A Critical Appraisal of American National Security Policy During the Cold War'' (2nd ed. 2005), pp 342–79. * Green, Michael J. ''By More Than Providence: Grand Strategy and American Power in the Asia Pacific Since 1783'' (Columbia UP, 2017) pp 327–428

online

* Goodhart, Michael. ''Human Rights: Politics and Practice'' (3rd edn). Oxford University Press, 2016. * Haftendorn, Helga and Jakob Schissler, eds. ''The Reagan Administration: A Reconstruction of American Strength?'' Berlin: Walter de Guyer, 1988. by European scholars * Inboden, William. ''The Peacemaker: Ronald Reagan, the Cold War, and the World on the Brink'' (Penguin Random House, 2022

two scholarly book reviews online

* Inboden, William. "Grand Strategy and Petty Squabbles: The Paradox of the Reagan National Security Council", in ''The Power of the Past: History and Statecraft'', ed. by Hal Brands and Jeremi Suri. (Brookings Institution Press, 2016), pp 151–80. * Kane, N. Stephen. ''Selling Reagan's Foreign Policy: Going Public vs. Executive Bargaining'' (Lexington Books, 2018). * * Knopf, Jeffrey W. "Did Reagan Win the Cold War?" ''Strategic Insights'', 3#8 (August 2004

online

* Kyvig, David. ed. ''Reagan and the World'' (1990), scholarly essays on foreign policy. * La Barca, Giuseppe. ''International Trade under President Reagan: US Trade Policy in the 1980s'' (Bloomsbury, 2023). * Laham, Nicholas. ''Crossing the Rubicon: Ronald Reagan and US Policy in the Middle East'' (2018). * Leffler, Melvyn P. "Ronald Reagan and the Cold War: What Mattered Most" ''Texas National Security Review'' (2018) 1#3 (May 2018

online

* Lucas, Scott, and Robert Pee. "Re-evaluating democracy promotion: the Reagan administration, allied authoritarian states, and regime change". ''Journal of Cold War Studies'' (2020). * Mann, James. ''The Rebellion of Ronald Reagan: A History of the End of the Cold War'' (Penguin, 2010) * Melanson, Richard A. ''American Foreign Policy Since the Vietnam War: The Search for Consensus from Nixon to Clinton'' (2015). * Pach, Chester. "The Reagan Doctrine: Principle, Pragmatism, and Policy". ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' (2006) 36#1 75–88. Reagan declared in 1985 that the U.S. should not "break faith" with anti-Communist resistance groups. However, his policies varied as differences in local conditions and US security interests produced divergent policies toward "freedom fighters" in Afghanistan, Nicaragua, Mozambique, Angola, and Cambodia. * Pee, Robert, and William Michael Schmidli, eds. ''The Reagan Administration, the Cold War, and the Transition to Democracy Promotion'' (Springer, 2018). * Ratnesar, Romesh. ''Tear Down This Wall: A City, a President, and the Speech that Ended the Cold War'' (2009) * Schmidt, Werner. "Ronald Reagan and his Rhetoric in Foreign Policy". in ''The Reagan Administration'' (De Gruyter, 2019) pp. 77–88. * Schmertz, Eric J. et al. eds. ''Ronald Reagan and the World'' (1997) articles by scholars and officeholders. * Schweizer, Peter. ''Reagan's War: The Epic Story of His Forty Year Struggle and Final Triumph Over Communism'' (2002) * Service, Robert. ''The End of the Cold War: 1985-1991'' (2015

excerpt

* Søndergaard, Rasmus Sinding. ''Reagan, Congress, and Human Rights: Contesting Morality in US Foreign Policy'' (Cambridge University Press, 2020). * Travis, Philip W. ''Reagan's War on Terrorism in Nicaragua: The Outlaw State'' (2016) * Velasco, Jesús. ''Neoconservatives in U.S. Foreign Policy Under Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush: Voices Behind the Throne'' (Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2010) * Walker, Thomas W., et al. ''Reagan Versus the Sandinistas: The Undeclared War On Nicaragua'' (Routledge, 2019). * Wallison, Peter J. ''Ronald Reagan: The Power of Conviction and the Success of His Presidency''. Westview Press, 2003. 282 pp. * Wills, David C. ''The First War on Terrorism: Counter-Terrorism Policy during the Reagan Administration''. (2004). * Wilson, James Graham. ''The Triumph of Improvisation: Gorbachev's Adaptability, Reagan's Engagement, and the End of the Cold War'' (2014) * Wilson, James Graham. "How Grand Was Reagan's Strategy, 1976–1984?" ''Diplomacy and Statecraft''. 18#4. (2007). 773–803. * Wormann, Claudia. "Reconstruction of Economic Strength? The (Foreign) Economic Policy of the Reagan Administration". in ''The Reagan Administration'' (De Gruyter, 2019) pp. 51–74

online

online

* Salla; Michael E. and Ralph Summy, eds. ''Why the Cold War Ended: A Range of Interpretations'' (Greenwood Press. 1995). * Schulzinger, Robert D. "Complaints, Self-justifications, and Analysis: The Historiography of American Foreign Relations since 1969." ''Diplomatic History'' 15.2 (1991): 245-264. * Siekmeier, James F. "The Iran–Contra Affair." in ''A Companion to Ronald Reagan'' (2015): 321-338. * Wilson, James Graham. "The Reagan Administration and the World, 1981–1988". in ''A Companion to US Foreign Relations: Colonial Era to the Present'' (2020): 1068–1082. * Witham, Nick. "Confronting a 'crisis in historical perspective': Walter LaFeber, Gabriel Kolko and the functions of revisionist historiography during the Reagan era." ''Left History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Historical Inquiry and Debate'' 15.1 (2010): 65-86.

U.S. State Department Office of the Historian: Reagan's Foreign Policy.U.S. Policy Towards the Contras

from th

Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

The Reagan Files: Collection of thousands of top-secret documents from the Reagan administration.

{{Foreign policy of U.S. presidents Presidency of Ronald Reagan History of the foreign relations of the United States Foreign policy by government, Reagan, Ronald United States foreign policy, Reagan, Ronald administration Foreign policy by United States presidential administration, Reagan, Ronald Public policy of the Reagan administration, Foreign policy Articles containing video clips

American foreign policy

The officially stated goals of the foreign policy of the United States of America, including all the bureaus and offices in the United States Department of State, as mentioned in the ''Foreign Policy Agenda'' of the Department of State, are ...

during the presidency of Ronald Reagan

Ronald Reagan's tenure as the 40th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1981, and ended on January 20, 1989. Reagan, a Republican from California, took office following his landslide victory over ...

(1981–1989) focused heavily on the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

which shifted from détente to confrontation. The Reagan administration pursued a policy of rollback

In political science, rollback is the strategy of forcing a change in the major policies of a state, usually by replacing its ruling regime. It contrasts with containment, which means preventing the expansion of that state; and with détente, ...

with regards to communist regimes. The Reagan Doctrine

The Reagan Doctrine was a United States foreign policy strategy implemented by the administration of President Ronald Reagan to overwhelm the global influence of the Soviet Union in the late Cold War. As stated by Reagan in his State of the Unio ...

operationalized these goals as the United States offered financial, logistical, training, and military equipment to anti-communist opposition in Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

, Angola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola, is a country on the west-Central Africa, central coast of Southern Africa. It is the second-largest Portuguese-speaking world, Portuguese-speaking (Lusophone) country in both total area and List of c ...

, and Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

. He expanded support to anti-communist movements in Central and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

.

Reagan's foreign policy also saw major shifts with regards to the Middle East. US intervention in the Lebanese Civil War

The Lebanese Civil War ( ) was a multifaceted armed conflict that took place from 1975 to 1990. It resulted in an estimated 150,000 fatalities and led to the exodus of almost one million people from Lebanon.

The religious diversity of the ...

was halted as Reagan ordered an evacuation of troops following the 1983 Marine Corps Barracks Attack. The 1979 Iran hostage crisis in Tehran strained relations with Iran and during the Iran-Iraq War, the administration publicly supported Iraq and sold weapons to Saddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein (28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician and revolutionary who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 1979 until Saddam Hussein statue destruction, his overthrow in 2003 during the 2003 invasion of Ira ...

.

Anti-communism was at the forefront with Reagan's Latin American foreign policy and the US supported forces fighting communist insurgencies or governments. As his administration progressed, opposition to continued US aid for these groups began to gather steam in Congress. Eventually, Congress forbade any US financial or material aid to certain anti-communist groups, among them the Contras

In the history of Nicaragua, the Contras (Spanish: ''La contrarrevolución'', the counter-revolution) were the right-wing militias who waged anti-communist guerilla warfare (1979–1990) against the Marxist governments of the Sandinista Na ...

in Nicaragua. In response, the Reagan administration facilitated covert arms sales to Iran and used the proceeds to fund Latin American anti-communists. The fallout from the Iran-Contra affair dominated Reagan's second term in office.

His policies are credited to have helped weaken the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and its control over Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP), formally the Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance (TFCMA), was a Collective security#Collective defense, collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Polish People's Republic, Poland, between the Sovi ...

countries. Although scholars have pushed back against giving Reagan the lion's share of the credit. Western confrontation combined with the Soviet Union's mishandling of domestic affairs lead to its weakening and ultimate dissolution. In 1989, after Reagan left office the Revolutions of 1989 saw Eastern European countries overthrow their communist regimes. Following the Soviet Union's dissolution in 1991 the United States emerged as the world's sole superpower and Reagan's successor George H.W. Bush sought to improve relations with former communist regimes in Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

.

Appointments

Eastern Europe and the USSR

Reagan had close friendships with key political leaders across the globe, especially the two strong conservativesMargaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013), was a British stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of th ...

in Britain, and Brian Mulroney

Martin Brian Mulroney (March 20, 1939 – February 29, 2024) was a Canadian lawyer, businessman, and politician who served as the 18th prime minister of Canada from 1984 to 1993.

Born in the eastern Quebec city of Baie-Comeau, Mulroney studi ...

in Canada. He and Thatcher provided mutual support in terms of fighting liberalism, reducing the welfare state, and confronting the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

in what turned out to be the final years of the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

.

Reagan ultimately departed from the historical policy of détente

''Détente'' ( , ; for, fr, , relaxation, paren=left, ) is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The diplomacy term originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsucces ...

with the Soviet Union, which had been followed after World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

by consecutive U.S. presidents, including Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

, Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. (born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was the 38th president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, Ford assumed the p ...

, and Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

. The Reagan administration implemented a new policy towards the Soviet Union, detailed in NSDD-32, a National Security Decisions Directive, to begin confronting the Soviet Union on three fronts: decreasing Soviet access to high technology and diminishing their resources, including depressing the value of Soviet commodities on the world market; to (also) increase American defense expenditures to strengthen the U.S. negotiating position; and to force the Soviets to devote more of their economic resources to defense. The massive American military build-up was the most visible.

Reagan supported anti-communist groups around the world. In a policy known as the "Reagan Doctrine

The Reagan Doctrine was a United States foreign policy strategy implemented by the administration of President Ronald Reagan to overwhelm the global influence of the Soviet Union in the late Cold War. As stated by Reagan in his State of the Unio ...

", his administration promised aid and counterinsurgency assistance to right-wing repressive regimes, such as the Marcos dictatorship in the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

, the South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

n apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

government, and the Hissène Habré

Hissène Habré (Arabic: ''Ḥusaīn Ḥabrī'', Chadian Arabic: ; ; 13 August 1942 – 24 August 2021), also spelled Hissen Habré, was a Chadian politician and convicted war criminal who served as the 5th president of Chad from 1982 unt ...

dictatorship in Chad

Chad, officially the Republic of Chad, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of North Africa, North and Central Africa. It is bordered by Libya to Chad–Libya border, the north, Sudan to Chad–Sudan border, the east, the Central Afric ...

, as well as to guerrilla movements opposing governments linked to the Soviet Union, such as the Contras

In the history of Nicaragua, the Contras (Spanish: ''La contrarrevolución'', the counter-revolution) were the right-wing militias who waged anti-communist guerilla warfare (1979–1990) against the Marxist governments of the Sandinista Na ...

in Nicaragua, the Mujahideen in Afghanistan, and the UNITA in Angola. During the Soviet–Afghan War

The Soviet–Afghan War took place in the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan from December 1979 to February 1989. Marking the beginning of the 46-year-long Afghan conflict, it saw the Soviet Union and the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic o ...

, Reagan deployed the CIA's Special Activities Division

The Special Activities Center (SAC) is the center of the United States Central Intelligence Agency responsible for covert operations. The unit was named Special Activities Division (SAD) prior to a 2015 reorganization. Within SAC there are at le ...

(SAD) Paramilitary Officers to train, equip, and lead the Mujahideen forces against the Soviet Army. Although the CIA (in general) and U.S. Congressman Charlie Wilson from Texas have received most of the attention, the key architect of this strategy was Michael G. Vickers, a young Paramilitary Officer. President Reagan's Covert Action program has been given credit for assisting in ending the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. When the Polish government suppressed the Solidarity

Solidarity or solidarism is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. True solidarity means moving beyond individual identities and single issue politics ...

movement in late 1981, Reagan imposed economic sanctions on the People's Republic of Poland

The Polish People's Republic (1952–1989), formerly the Republic of Poland (1947–1952), and also often simply known as Poland, was a country in Central Europe that existed as the predecessor of the modern-day democratic Republic of Poland. ...

.

In its national security policies, the administration Reagan administration revived the B-1 bomber program in 1981 that had been canceled by the Carter administration

Jimmy Carter's tenure as the List of presidents of the United States, 39th president of the United States began with Inauguration of Jimmy Carter, his inauguration on January 20, 1977, and ended on January 20, 1981. Carter, a Democratic Party ...

, continued secret development of the B-2 Spirit

The Northrop B-2 Spirit, also known as the Stealth Bomber, is an American Heavy bomber, heavy strategic bomber, featuring low-observable stealth aircraft, stealth technology designed to penetrator (aircraft), penetrate dense anti-aircraft war ...

that Carter intended to replace the B-1, and began production of the MX "Peacekeeper" missile. In response to Soviet deployment of the RSD-10 Pioneer

The RSD-10 ''Pioneer'' ( tr.: ''raketa sredney dalnosti (RSD) "Pioner"''; ) was an intermediate-range ballistic missile with a nuclear warhead, deployed by the Soviet Union from 1976 to 1988. It carried GRAU designation 15Ж45 (''15Zh45''). ...

and in accordance with NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

's double-track decision, the administration deployed Pershing II

The Pershing II Weapon System was a solid-fueled two-stage medium-range ballistic missile designed and built by Martin Marietta to replace the Pershing 1a Field Artillery Missile System as the United States Army's primary nuclear-capable thea ...

missiles in West Germany to gain a stronger bargaining position to eventually eliminate that entire class of nuclear weapons. His position was that if the Soviets did not remove the RSD-10 missiles (without a concession from the US), America would simply introduce the Pershing II missiles for a stronger bargaining position, and both missiles would be eliminated.

One of Reagan's proposals was the Strategic Defense Initiative

The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) was a proposed missile defense system intended to protect the United States from attack by ballistic nuclear missiles. The program was announced in 1983, by President Ronald Reagan. Reagan called for a ...

(SDI). He believed this defense shield could make nuclear war impossible, but the unlikelihood that the technology could ever work led opponents to dub SDI "Star Wars". Critics of the SDI believed that the technological objective was unattainable, that the attempt would likely accelerate the arms race

An arms race occurs when two or more groups compete in military superiority. It consists of a competition between two or more State (polity), states to have superior armed forces, concerning production of weapons, the growth of a military, and ...

, and that the extraordinary expenditures amounted to a military-industrial boondoggle. Supporters responded that the SDI gave the President a stronger bargaining position. Indeed, Soviet leaders became genuinely concerned.

Reagan believed that the American economy was on the move again while the Soviet economy had become stagnant. For a while, the Soviet decline was masked by high prices for Soviet oil exports, but that crutch collapsed in the early-1980s. In November 1985, the oil price was $30/barrel for crude, and in March 1986, it had fallen to only $12.

Reagan's militant rhetoric inspired dissidents in the Soviet Empire, but also startled allies and alarmed critics. In a famous address to the National Association of Evangelicals

The National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) is an American association of Evangelical Christian denominations, organizations, schools, churches, and individuals, member of the World Evangelical Alliance. The association represents more than ...

on March 8, 1983, he called the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

an " evil empire" that would be consigned to the "ash heap of history

The phrase "ash heap of history", is a derogatory metaphoric reference to oblivion of things no longer relevant.

In 1887 the English essayist Augustine Birrell (1850–1933) coined the term in his series of essays, "Obiter Dicta": ''that great ...

". After Soviet fighters downed Korean Airlines Flight 007 on September 1, 1983, he labeled the act an "act of barbarism ... finhuman brutality". Reagan's description of the Soviet Union as an "evil empire" drew the wrath of some as provocative, but his description was staunchly defended by his conservative supporters. Michael Johns of The Heritage Foundation

The Heritage Foundation (or simply Heritage) is an American Conservatism in the United States, conservative think tank based in Washington, D.C. Founded in 1973, it took a leading role in the conservative movement in the 1980s during the Presi ...

prominently defended Reagan in a '' Policy Review'' article, "Seventy Years of Evil", in which he identified 208 alleged acts of evil by the Soviet Union since the Bolshevik Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of two revolutions in Russia in 1917. It was led by Vladimir L ...

in 1917.

On March 3, 1983, Reagan predicted that communism would collapse: "I believe that communism is another sad, bizarre chapter in human history whose—last pages even now are being written", he said. He elaborated on June 8, 1982, to the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of ...

. Reagan argued that the Soviet Union was in deep economic crisis and stated that the Soviet Union "runs against the tide of history by denying human freedom and human dignity to its citizens."

This was before Gorbachev rose to power in 1985. Reagan later wrote in his autobiography

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life, providing a personal narrative that reflects on the author's experiences, memories, and insights. This genre allows individuals to share thei ...

'' An American Life'' that he "did not see the profound changes that would occur in the Soviet Union after Gorbachev rose to power." To confront the Soviet Union's serious economic problems, Gorbachev implemented bold new policies for economic liberalisation and openness called ''glasnost

''Glasnost'' ( ; , ) is a concept relating to openness and transparency. It has several general and specific meanings, including a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information and the inadmissi ...

'' and ''perestroika

''Perestroika'' ( ; rus, перестройка, r=perestrojka, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg, links=no) was a political reform movement within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s, widely associ ...

''.

End of Cold War

Reagan relaxed his aggressive rhetoric toward the Soviet Union after Gorbachev became General Secretary of the Soviet Politburo in 1985, and took on a position of negotiating. In turn, the Soviets reversed their hostile view of Reagan and began negotiating in earnest. The Soviet Union was in deep economic trouble, and could no longer afford an increasingly expensive Cold War. The military consumed as much as 25% of the Soviet Union's gross national product at the expense ofconsumer goods

A final good or consumer good is a final product ready for sale that is used by the consumer to satisfy current wants or needs, unlike an intermediate good, which is used to produce other goods. A microwave oven or a bicycle is a final good.

W ...

and investment in civilian sectors.(LaFeber 2002, 332) But the size of the Soviet Armed Forces

The Armed Forces of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, also known as the Armed Forces of the Soviet Union, the Red Army (1918–1946) and the Soviet Army (1946–1991), were the armed forces of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republi ...

was not necessarily the result of a simple action-reaction arms race with the United States. Instead, Soviet spending on the arms race

An arms race occurs when two or more groups compete in military superiority. It consists of a competition between two or more State (polity), states to have superior armed forces, concerning production of weapons, the growth of a military, and ...

and other Cold War commitments can be understood as both a cause and effect of the deep-seated structural problems in the Soviet system, which accumulated at least a decade of economic stagnation during the Brezhnev years. Soviet investment in the defense sector was not necessarily driven by military necessity, but in large part by the interests of massive party and state bureaucracies dependent on the sector for their own power and privileges.

By the time Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

had ascended to power in 1985, the Soviets suffered from an economic growth rate close to zero percent, combined with a sharp fall in hard currency

In macroeconomics, hard currency, safe-haven currency, or strong currency is any globally traded currency that serves as a reliable and stable store of value. Factors contributing to a currency's ''hard'' status might include the stability and ...

earnings as a result of the downward slide in world oil prices

The price of oil, or the oil price, generally refers to the spot price of a barrel () of benchmark crude oil—a reference price for buyers and sellers of crude oil such as West Texas Intermediate (WTI), Brent Crude, Dubai Crude, OPE ...

in the 1980s; petroleum exports made up around 60 percent of the Soviet Union's total export earnings. To restructure the Soviet economy before it collapsed, Gorbachev announced an agenda of rapid reform, based upon what he called ''perestroika

''Perestroika'' ( ; rus, перестройка, r=perestrojka, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg, links=no) was a political reform movement within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s, widely associ ...

'', meaning "restructuring", and ''glasnost

''Glasnost'' ( ; , ) is a concept relating to openness and transparency. It has several general and specific meanings, including a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information and the inadmissi ...

'', meaning "liberalization" and "openness". Reform required Gorbachev to redirect the country's resources from costly Cold War military commitments to more profitable areas in the civilian sector. As a result, Gorbachev offered major concessions to the United States on the levels of conventional forces, nuclear weapons, and policy in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

.

Many U.S.-based Sovietologists and administration officials doubted that Gorbachev was serious about winding down the arms race, but Reagan recognized the real change in the direction of the Soviet leadership, and shifted to skillful diplomacy to personally push Gorbachev further with his reforms.

Reagan sincerely believed that if he could persuade the Soviets to simply look at the prosperous American economy, they too would embrace free markets

In economics, a free market is an economic market (economics), system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of ...

and a free society.

At a speech given at the Berlin Wall

The Berlin Wall (, ) was a guarded concrete Separation barrier, barrier that encircled West Berlin from 1961 to 1989, separating it from East Berlin and the East Germany, German Democratic Republic (GDR; East Germany). Construction of the B ...

on the city's 750th birthday, Reagan pushed Gorbachev further in front of 20,000 onlookers: "General Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, if you seek liberalization: Come here to this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!" The last sentence became "the four most famous words of Ronald Reagan's Presidency". Reagan later said that the "forceful tone" of his speech was influenced by hearing before his speech that those on the East side of the wall attempting to hear him had been kept away by police. The Soviet news agency wrote that Reagan's visit was "openly provocative, war-mongering".

The east–west tensions that had reached intense new heights earlier in the decade rapidly subsided through the mid-to-late 1980s. In 1988, the Soviets officially declared that they would no longer intervene in the affairs of allied states in Eastern Europe. In 1989, Soviet forces withdrew from Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

.

Reagan's Secretary of State George P. Shultz, a former economics professor, privately instructed Gorbachev on free market economics. At Gorbachev's request, Reagan gave a speech on free markets at Moscow University.

When Reagan visited Moscow, he was viewed as a celebrity by the Soviets. A journalist

A journalist is a person who gathers information in the form of text, audio or pictures, processes it into a newsworthy form and disseminates it to the public. This is called journalism.

Roles

Journalists can work in broadcast, print, advertis ...

asked the president if he still considered the Soviet Union the evil empire. "No", he replied, "I was talking about another time, another era."

In his autobiography ''An American Life'', Reagan expressed his optimism about the new direction they charted, his warm feelings for Gorbachev, and his concern for Gorbachev's safety because Gorbachev pushed reforms so hard. "I was concerned for his safety", Reagan wrote. "I've still worried about him. How hard and fast can he push reforms without risking his life?" Events would unravel far beyond what Gorbachev originally intended.

Soviet Union's collapse

According toDavid Remnick

David J. Remnick (born October 29, 1958) is an American journalist, writer, and editor. He won a Pulitzer Prize in 1994 for his book '' Lenin's Tomb: The Last Days of the Soviet Empire'', and is also the author of ''Resurrection'' and ''King of t ...

in his book '' Lenin's Tomb: The Last Days of the Soviet Empire'', Gorbachev's perestroika

''Perestroika'' ( ; rus, перестройка, r=perestrojka, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg, links=no) was a political reform movement within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s, widely associ ...

and glasnost

''Glasnost'' ( ; , ) is a concept relating to openness and transparency. It has several general and specific meanings, including a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information and the inadmissi ...

reforms opened the Pandora's box of freedom. Once the people benefited from the reforms, they wanted more. "Once the regime eased up enough to permit a full-scale examination of the Soviet past", Remnick wrote, "radical change was inevitable. Once the System showed itself for what it was and had been, it was doomed."

In December 1989, Gorbachev and George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushBefore the outcome of the 2000 United States presidential election, he was usually referred to simply as "George Bush" but became more commonly known as "George H. W. Bush", "Bush Senior," "Bush 41," and even "Bush th ...

declared the Cold War officially over at a summit meeting in Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

. The Soviet alliance system was by then on the brink of collapse, and the Communist regimes of the Warsaw Pact were losing power. On March 11, 1990 Lithuania

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, P ...

, led by newly elected Vytautas Landsbergis

Vytautas Landsbergis (; born 18 October 1932) is a Lithuanian politician and former Member of the European Parliament. He was the first Speaker of Reconstituent Seimas of Lithuania after its independence declaration from the Soviet Union. He ...

, declared independence from the Soviet Union. The gate to the Berlin Wall was opened and Gorbachev approved. Gorbachev proposed to President George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushBefore the outcome of the 2000 United States presidential election, he was usually referred to simply as "George Bush" but became more commonly known as "George H. W. Bush", "Bush Senior," "Bush 41," and even "Bush th ...

massive troop reductions in Eastern Europe. In the USSR itself, Gorbachev tried to reform the party to destroy resistance to his reforms, but, in doing so, ultimately weakened the bonds that held the state and union together. By February 1990, the Communist Party was forced to surrender its 73-year-old monopoly on state power. Soviet hardliners rebelled and staged a coup against Gorbachev, but it failed. Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin (1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician and statesman who served as President of Russia from 1991 to 1999. He was a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) from 1961 to ...

rallied Russians in the street while Gorbachev was held hostage. By December 1991, the union-state had dissolved, breaking the USSR up into fifteen separate independent states. Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin (1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician and statesman who served as President of Russia from 1991 to 1999. He was a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) from 1961 to ...

became leader of the new Russia.

In her eulogy to Ronald Reagan at his funeral, former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013), was a British stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of th ...

, whom Reagan worked very closely with during his tenure in office, said, "Others hoped, at best, for an uneasy cohabitation with the Soviet Union; he won the Cold War — not only without firing a shot, but also by inviting enemies out of their fortress and turning them into friends. ... Yes, he did not shrink from denouncing Moscow's 'evil empire.' But he realized that a man of goodwill might nonetheless emerge from within its dark corridors. So the President resisted Soviet expansion and pressed down on Soviet weakness at every point until the day came when communism began to collapse beneath the combined weight of these pressures and its own failures. And when a man of goodwill did emerge from the ruins, President Reagan stepped forward to shake his hand and to offer sincere cooperation."

For his role, Gorbachev received the first Ronald Reagan Freedom Award, as well as the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

.

Asia

China

Reagan had been a prominent spokesman on behalf ofTaiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

in the political arena, but his advisors convinced him to announce in his 1980 campaign that he would continue the opening to China. Haig argued strenuously that the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

could be a major ally against the Soviet Union. Beijing refused to accept any two-China policy but agreed to postpone any showdown. As President, Reagan issued the " Six Assurances" to Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

and a joint communique with the PRC reaffirming the one-China policy

''One China'' is a phrase describing the relationship between the People's Republic of China (PRC) based on mainland China, and the Republic of China (ROC) based on the Taiwan Area. "One China" asserts that there is only one ''de jure'' C ...

. As the Cold War wound down during Reagan's second term, and Shultz replaced Haig, the need for China as an ally faded away. Shultz focused much more on economic trade with Japan. Beijing

Beijing, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's List of national capitals by population, most populous national capital city as well as ...

warmly welcomed the president when he visited in 1984.

In commercial space travel, Reagan backed a plan which allowed American satellites to be exported and launched on China's Long March rockets. This was criticized by Bill Nelson

Clarence William Nelson II (born September 29, 1942) is an American politician, attorney, and former astronaut who served from 2001 to 2019 as a United States Senate, United States senator from Florida and from 2021 to 2025 as the Administrator ...

, then a Florida representative, as delaying U.S.'s own commercial space development, while industry leaders criticized the idea of a nation-state competing with private entities in the rocketry market. The China satellite export deal continued through Bush and Clinton administrations.

Japan

Trade issues with Japan dominated relationships, especially the threat that American automobile and high tech industries would be overwhelmed. After 1945, the U.S. produced about 75 percent of world's auto production. In 1980, the U.S. was overtaken by Japan and then became world's leader again in 1994. In 2006, Japan narrowly passed the U.S. in production and held this rank until 2009, when China took the top spot with 13.8 million units. Japan's economic miracle emerged from a systematic program of subsidized investment in strategic industries—steel, machinery, electronics, chemicals, autos, shipbuilding, and aircraft. During Reagan's first term, Japanese government and private investors owned a third of the debt sold by theUS Treasury

The Department of the Treasury (USDT) is the national treasury and finance department of the federal government of the United States. It is one of 15 current U.S. government departments.

The department oversees the Bureau of Engraving and ...

, providing Americans with hard currency used to buy Japanese goods. In March 1985 the Senate voted 92–0 in favor of a Republican resolution that condemned Japan's trade practices as "unfair" and called on President Reagan to curb Japanese imports. In 1981, Japanese automakers entered into the "voluntary export restraint

A voluntary export restraint (VER) or voluntary export restriction is a self-imposed, voluntary restriction implemented by an exporting country, on the volume of its exports to another country. This can be negotiated between governments, or with ...

" limiting the number of autos that they could export to the U.S. to 1.68 million per year.

Although the main current of the Reagan administration was anti-communism, Michael J. Heale argued that popular fears of Japan amounted to another "Yellow Peril

The Yellow Peril (also the Yellow Terror, the Yellow Menace, and the Yellow Specter) is a Racism, racist color terminology for race, color metaphor that depicts the peoples of East Asia, East and Southeast Asia as an existential danger to the ...

". By 1990, Japan had eclipsed the Soviet Union as "the greatest perceived threat" in opinion polls.

Pakistan and India

Although Pakistan was ruled by

Although Pakistan was ruled by Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq

Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq (12 August 192417 August 1988) was a Pakistani military officer and statesman who served as the sixth president of Pakistan from 1978 until Death of Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, his death in an airplane crash in 1988. He also se ...

and his military dictatorship (1978–1988), it was an important ally against Soviet efforts to take control of Afghanistan. Reagan's new priorities enabled the effective effort by Congressman Charles Wilson (D-TX), aided by Joanne Herring, and CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

Afghan Desk Chief Gust Avrakotos to increase the funding for Operation Cyclone

Operation Cyclone was the code name for the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) program to arm and finance the Afghan mujahideen in Afghanistan from 1979 to 1992, prior to and during the military intervention by the USSR in support ...

. Congress passed a six-year $3.2 billion programme of economic and military assistance, plus secret to the Afghan resistance sent through Pakistan. American officials visited the country on a routine basis, bolstering the Zia regime and weakening Pakistan's liberals, socialists, communists, and democracy advocates. General Akhtar Abdur Rahman of ISI and William Casey

William Joseph Casey (March 13, 1913 – May 6, 1987) was an American lawyer who was the Director of Central Intelligence from 1981 to 1987. In this capacity he oversaw the entire United States Intelligence Community and personally directed the ...

of CIA worked together in harmony, and in an atmosphere of mutual trust. Reagan sold Pakistan attack helicopters, self-propelled howitzers, armoured personnel carriers, 40 F-16 Fighting Falcon

The General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon is an American single-engine supersonic Multirole combat aircraft, multirole fighter aircraft originally developed by General Dynamics for the United States Air Force (USAF). Designed as an air superio ...

warplanes, nuclear technology, naval warships, and intelligence equipment and training.

Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and stateswoman who served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India from 1966 to 1977 and again from 1980 un ...

returned to power in India in 1980 and relations were slow to improve. India gave tacit support to the USSR in the Soviet invasion and occupation of Afghanistan. New Delhi sounded out Washington on the purchase of a range of American defence technology, including F-5 aircraft, super computers, night vision goggles and radars. In 1984 Washington approved the supply of selected technology to India including gas turbines for naval frigates and engines for prototypes for India's light combat aircraft. There were also unpublicised transfers of technology, including the engagement of an American company, Continental Electronics

Continental Electronics is an American manufacturer of broadcast and military radio transmitters, based in Dallas, Texas. Although Continental today is best known for its FM, shortwave, and military VLF transmitters, Continental is most signific ...

, to design and build a new VLF communications station at Tirunelveli

Tirunelveli (), also known as Nellai and historically (during British rule) as Tinnevelly, is a major city in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. It is the administrative headquarters of the Tirunelveli District. It is the fourth-largest munici ...

, Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is the southernmost States and union territories of India, state of India. The List of states and union territories of India by area, tenth largest Indian state by area and the List of states and union territories of Indi ...

. However, by the late 1980s there was a significant effort by both countries to improve relations.

Afghanistan

Upon becoming president, Reagan moved quickly to undermine Soviet efforts to support the government of Afghanistan, as the Soviet Army had entered that country at Kabul's request in 1979.

Islamic mujahideen guerrillas were covertly supported and trained, and backed in their

Upon becoming president, Reagan moved quickly to undermine Soviet efforts to support the government of Afghanistan, as the Soviet Army had entered that country at Kabul's request in 1979.

Islamic mujahideen guerrillas were covertly supported and trained, and backed in their jihad

''Jihad'' (; ) is an Arabic word that means "exerting", "striving", or "struggling", particularly with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it encompasses almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with God in Islam, God ...

against the occupying Soviets by the CIA. The agency sent billions of dollars in military aid to the guerrillas, in what came to be known as "Charlie Wilson's War".

One of the CIA's longest and most expensive covert operations was the supplying of billions of dollars in arms to the Afghan mujahideen militants. The CIA provided assistance to the fundamentalist insurgents through the Pakistani ISI in a program called Operation Cyclone

Operation Cyclone was the code name for the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) program to arm and finance the Afghan mujahideen in Afghanistan from 1979 to 1992, prior to and during the military intervention by the USSR in support ...

. Somewhere between $2–$20 billion in U.S. funds were funneled into the country to equip troops with weapons.

With U.S. and other funding, the ISI armed and trained over 100,000 insurgents. On July 20, 1987, the withdrawal of Soviet troops from the country was announced pursuant to the negotiations that led to the Geneva Accords of 1988, with the last Soviets leaving on February 15, 1989.

The early foundations of al-Qaeda

, image = Flag of Jihad.svg

, caption = Jihadist flag, Flag used by various al-Qaeda factions

, founder = Osama bin Laden{{Assassinated, Killing of Osama bin Laden

, leaders = {{Plainlist,

* Osama bin Lad ...

were allegedly built in part on relationships and weaponry that came from the billions of dollars in U.S. support for the Afghan mujahideen during the war to expel Soviet forces from that country. However, these allegations

In law, an allegation is a claim of an unproven fact by a party in a pleading, charge, or defense. Until they can be proved, allegations remain merely assertions.

Types of allegations Marital allegations

There are also marital allegations: m ...

are rejected by Steve Coll ("If the CIA did have contact with bin Laden during the 1980s and subsequently covered it up, it has so far done an excellent job"), Peter Bergen

Peter Lampert Bergen (born December 12, 1962) is an American journalist, documentary producer, historian, and author, best known for his work on national security and counterterrorism. He has written or edited ten books—three of which were ...

("The theory that bin Laden was created by the CIA is invariably advanced as an axiom with no supporting evidence"), and Jason Burke

Jason Burke (born 1970) is a British journalist and the author of several non-fiction books. he was a correspondent covering Africa for ''The Guardian'', based in Johannesburg, having previously been based in New Delhi as the same paper's South ...

("It is often said that bin Laden was funded by the CIA. This is not true, and, indeed, would have been impossible given the structure of funding that General Zia ul–Haq, who had taken power in Pakistan in 1977, had set up").

Cambodia

Reagan sought to apply theReagan Doctrine

The Reagan Doctrine was a United States foreign policy strategy implemented by the administration of President Ronald Reagan to overwhelm the global influence of the Soviet Union in the late Cold War. As stated by Reagan in his State of the Unio ...

of aiding anti-Soviet resistance movements abroad to Cambodia

Cambodia, officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. It is bordered by Thailand to the northwest, Laos to the north, and Vietnam to the east, and has a coastline ...

, which was under Vietnamese occupation after having ousted Pol Pot

Pol Pot (born Saloth Sâr; 19 May 1925 – 15 April 1998) was a Cambodian politician, revolutionary, and dictator who ruled the communist state of Democratic Kampuchea from 1976 until Cambodian–Vietnamese War, his overthrow in 1979. During ...

's communist Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge is the name that was popularly given to members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK), and by extension to Democratic Kampuchea, which ruled Cambodia between 1975 and 1979. The name was coined in the 1960s by Norodom Sihano ...

regime which had perpetrated the Cambodian genocide

The Cambodian genocide was the systematic persecution and killing of Cambodian citizens by the Khmer Rouge under the leadership of Pol Pot. It resulted in the deaths of 1.5 to 2 million people from 1975 to 1979, nearly 25% of Cambodia's populati ...

. The Vietnamese had installed the communist PRK government led by Salvation Front dissident Heng Samrin

Heng Samrin (; born 25 May 1934) is a Cambodian politician who served as the President of the National Assembly of Cambodia (2006–2023). Between 1979 and 1992, he was the '' de facto'' leader of the Hanoi-backed People's Republic of Kampuchea ...

. The largest resistance movement fighting the PRK government was largely made up of members of the China-backed former Khmer Rouge regime, whose human rights record was among the worst of the 20th century.

Therefore, Reagan authorized the covert provision of aid to smaller Cambodian resistance movements, referred to collectively as the "non-communist resistance" (NCR) and including the partisans of Norodom Sihanouk

Norodom Sihanouk (; 31 October 192215 October 2012) was a member of the House of Norodom, Cambodian royal house who led the country as Monarchy of Cambodia, King, List of heads of state of Cambodia, Chief of State and Prime Minister of Cambodi ...

and a coalition called the Khmer People's National Liberation Front

The Khmer People's National Liberation Front (KPNLF, ) was a political front organized in 1979 in opposition to the Vietnamese-installed People's Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) regime in Cambodia. The 200,000 Vietnamese troops supporting the PRK, as ...

(KPNLF) then run by Son Sann

Son Sann (, ; 5 October 191119 December 2000) was a Cambodian politician and anti-communist resistance leader who served as the 22nd Prime Minister of Cambodia (1967–68) and later as President of the National Assembly (1993). A devout ...