Reaction To Darwin's Theory on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The immediate reactions, from November 1859 to April 1861, to ''

On 10 February 1860 Huxley gave a lecture titled ''On Species and Races, and their Origin'' at the

On 10 February 1860 Huxley gave a lecture titled ''On Species and Races, and their Origin'' at the

From Hooker's account, Draper "droned on for an hour", then for half an hour "Soapy Sam" Wilberforce replied with the eloquence that had earned him his nickname. This time the climate of opinion had changed and the ensuing debate was more evenly matched, with Hooker being particularly successful in defence of Darwin's ideas. In response to what Huxley took as a jibe from Wilberforce as to whether it was on Huxley's grandfather's or grandmother's side that he was descended from an ape, Huxley made a reply which he later recalled as being that " f askedwould I rather have a miserable ape for a grandfather or a man highly endowed by nature and possessed of great means and influence and yet who employs these faculties and that influence for the mere purpose of introducing ridicule into a grave scientific discussion I unhesitatingly affirm my preference for the ape". No verbatim record was taken: eyewitness accounts exist, and vary somewhat.

From Hooker's account, Draper "droned on for an hour", then for half an hour "Soapy Sam" Wilberforce replied with the eloquence that had earned him his nickname. This time the climate of opinion had changed and the ensuing debate was more evenly matched, with Hooker being particularly successful in defence of Darwin's ideas. In response to what Huxley took as a jibe from Wilberforce as to whether it was on Huxley's grandfather's or grandmother's side that he was descended from an ape, Huxley made a reply which he later recalled as being that " f askedwould I rather have a miserable ape for a grandfather or a man highly endowed by nature and possessed of great means and influence and yet who employs these faculties and that influence for the mere purpose of introducing ridicule into a grave scientific discussion I unhesitatingly affirm my preference for the ape". No verbatim record was taken: eyewitness accounts exist, and vary somewhat.

William Whewell Quotes - 38 Science Quotes - Dictionary of Science Quotations and Scientist Quotes

Letter to James D, Forbes (24 Jul 1860)

On the secular cooling of the earth

, read 28 April 1862. ''Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh'', 23, 157–170.

pdf

*. Published anonymously. * * * * * * * * * *. Letter dated January 1861. * * *. The first edition was published in 1900. *. Published anonymously. *. Published anonymously. * * * * *. Published anonymously. *. Published anonymously. *. Published anonymously. *.

Darwin Online

Darwin's publications, private papers and bibliography, supplementary works including biographies, obituaries and reviews. For a comprehensive set of reviews of ''On the Origin of Species'' se

*

Darwin Correspondence Project

Text and notes for most of his letters.

Charles Darwin in the British horticultural press

- Occasional Papers from RHS Lindley Library, volume 3 July 2010 {{History of science Charles Darwin History of evolutionary biology Reception of works 1859 in science

On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

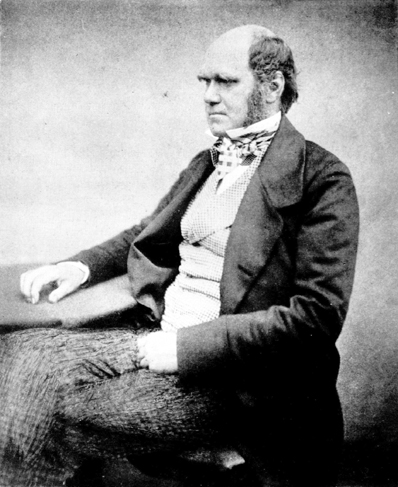

'', the book in which Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

described evolution by natural selection, included international debate, though the heat of controversy was less than that over earlier works such as ''Vestiges of Creation

''Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation'' is an 1844 work of speculative natural history and philosophy by Robert Chambers (publisher born 1802), Robert Chambers. Published anonymously in England, it brought together various ideas of stell ...

''. Darwin monitored the debate closely, cheering on Thomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist who specialized in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

's battles with Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

to remove clerical domination of the scientific establishment. While Darwin's illness kept him away from the public debates, he read eagerly about them and mustered support through correspondence.

Religious views were mixed, with the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

's scientific establishment reacting against the book, while liberal Anglicans strongly supported Darwin's natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

as an instrument of God's design. Religious controversy was soon diverted by the publication of ''Essays and Reviews

''Essays and Reviews'', published by John William Parker in March 1860, is a Broad church, broad-church volume of seven essays on Christianity. The topics covered the biblical research of the German critics, the evidence for Christianity, religio ...

'' and debate over the higher criticism

Historical criticism (also known as the historical-critical method (HCM) or higher criticism, in contrast to lower criticism or textual criticism) is a branch of criticism that investigates the origins of ancient texts to understand "the world b ...

.

The most famous confrontation took place at the public 1860 Oxford evolution debate

The 1860 Oxford evolution debate took place at the Oxford University Museum in Oxford, England, on 7 July 1860, seven months after the publication of Charles Darwin's ''On the Origin of Species''. Several prominent British scientists and philoso ...

during a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science

The British Science Association (BSA) is a Charitable organization, charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Scienc ...

, when the Bishop of Oxford

The Bishop of Oxford is the diocesan bishop of the Church of England Diocese of Oxford in the Province of Canterbury; his seat is at Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford. The current bishop is Steven Croft (bishop), Steven Croft, following the Confirm ...

Samuel Wilberforce

Samuel Wilberforce, Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (7 September 1805 – 19 July 1873) was an English bishop in the Church of England, and the third son of William Wilberforce. Known as "Soapy Sam", Wilberforce was one of the greatest public sp ...

argued against Darwin's explanation. In the ensuing debate Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

argued strongly in favor of Darwinian evolution. Thomas Huxley's support of evolution was so intense that the media and public nicknamed him "Darwin's bulldog". Huxley became the fiercest defender of the evolutionary theory on the Victorian stage. Both sides came away feeling victorious, but Huxley went on to depict the debate as pivotal in a struggle between religion and science and used ''Darwinism

''Darwinism'' is a term used to describe a theory of biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others. The theory states that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural sel ...

'' to campaign against the authority of the clergy in education, as well as daringly advocating the "Ape Origin of Man".

Background

Darwin's ideas developed rapidly after returning fromthe Voyage of the Beagle

''The Voyage of the Beagle'' is the title most commonly given to the book written by Charles Darwin and published in 1839 as his ''Journal and Remarks'', bringing him considerable fame and respect. This was the third volume of ''The Narrative ...

in 1836. By December 1838, he had developed the basic principles of his theory. At that time, ideas about the transmutation of species

The Transmutation of species and transformism are 18th and early 19th-century ideas about the change of one species into another that preceded Charles Darwin's theory of evolution through natural selection. The French ''Transformisme'' was a ter ...

were associated with radical political ideas of the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

and the French Revolution, and some people, such as Darwin's old instructor Robert Edmond Grant

Robert Edmond Grant MD FRCPEd FRS FRSE FZS FGS (11 November 1793 – 23 August 1874) was a British anatomist and zoologist.

Life

Grant was born at Argyll Square in Edinburgh (demolished to create Chambers Street), the son of Alexander Gra ...

had been ridiculed and marginalized by members of the scientific establishment such as Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

for advocating them. Darwin was conscious of the need to answer all likely objections before publishing. While he continued with research, he had an immense amount of work in hand analyzing and publishing findings from the Beagle expedition, and was repeatedly delayed by illness.

The Natural history, especially in Britain, at that time was dominated by proponents of natural theology

Natural theology is a type of theology that seeks to provide arguments for theological topics, such as the existence of a deity, based on human reason. It is distinguished from revealed theology, which is based on supernatural sources such as ...

, who saw their science as revealing God's plan, and many of whom, like Darwin's professors Adam Sedgwick

Adam Sedgwick FRS (; 22 March 1785 – 27 January 1873) was a British geologist and Anglican priest, one of the founders of modern geology. He proposed the Cambrian and Devonian period of the geological timescale. Based on work which he did ...

and John Stevens Henslow

John Stevens Henslow (6 February 1796 – 16 May 1861) was an English Anglican priest, botanist and geologist. He is best remembered as friend and mentor to Charles Darwin.

Early life

Henslow was born at Rochester, Kent, the son of a solicit ...

, were ordained clergy in the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

. Darwin found three close allies. The eminent geologist Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known today for his association with Charles ...

, whose books had influenced the young Darwin during the Voyage of the Beagle

''The Voyage of the Beagle'' is the title most commonly given to the book written by Charles Darwin and published in 1839 as his ''Journal and Remarks'', bringing him considerable fame and respect. This was the third volume of ''The Narrative ...

, befriended Darwin who he saw as a supporter of his ideas of gradual geological processes with continuing divine creation of species. By the 1840s Darwin became friends with the young botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker who had followed his father into the science, and after going on a survey voyage used his contacts to eventually find a position. In the 1850s Darwin met Thomas Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist who specialized in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

, an ambitious naturalist who had returned from a long survey trip but lacked the family wealth or contacts to find a career and who joined the progressive group around Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English polymath active as a philosopher, psychologist, biologist, sociologist, and anthropologist. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest", which he coined in '' ...

looking to make science a profession, freed from the clerics.

This was also a time of intense conflict over religious morality in England, where evangelicalism

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

led to increasing professionalism of clerics who had previously been expected to act as country gentlemen with wide interests, but now were seriously focussed on expanded religious duties. A new orthodoxy proclaimed the virtues of truth but also inculcated beliefs that the Bible should be read literally and that religious doubt was in itself sinful so should not be discussed. Science was also becoming professional and a series of discoveries cast doubt on literal interpretations of the Bible and the honesty of those denying the findings. A series of crises erupted with fierce debate and criticism over issues such as George Combe

George Combe (21 October 1788 – 14 August 1858) was a Scottish people, Scottish lawyer and a spokesman of the phrenology, phrenological movement for over 20 years. He founded the Edinburgh Phrenological Society in 1820 and wrote ''The Constitu ...

's '' The Constitution of Man'' and the anonymous ''Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation

''Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation'' is an 1844 work of speculative natural history and philosophy by Robert Chambers. Published anonymously in England, it brought together various ideas of stellar evolution with the progressive tra ...

'' which converted vast popular audiences to the belief that natural laws controlled the development of nature and society. German higher criticism

Historical criticism (also known as the historical-critical method (HCM) or higher criticism, in contrast to lower criticism or textual criticism) is a branch of criticism that investigates the origins of ancient texts to understand "the world b ...

questioned the Bible as a historical document in contrast to the evangelical creed that every word was divinely inspired. Dissident clergymen even began questioning accepted premises of Christian morality, and Benjamin Jowett

Benjamin Jowett (, modern variant ; 15 April 1817 – 1 October 1893) was an English writer and classical scholar. Additionally, he was an administrative reformer in the University of Oxford, theologian, Anglican cleric, and translator of Plato ...

's 1855 commentary on St. Paul brought a storm of controversy.

By September 1854 Darwin's other books reached a stage where he was able to turn his attention fully to ''Species'', and from this point he was working to publish his theory. On 18 June 1858 he received a parcel from Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was an English naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He independently conceived the theory of evolution through natural selection; his 1858 pap ...

enclosing about twenty pages describing an evolutionary mechanism that was similar to Darwin's own theory. Darwin put matters in the hands of his friends Lyell and Hooker, who agreed on a joint presentation to the Linnean Society

The Linnean Society of London is a learned society dedicated to the study and dissemination of information concerning natural history, evolution, and taxonomy. It possesses several important biological specimen, manuscript and literature collec ...

on 1 July 1858. Their papers were entitled, collectively, ''On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection

"On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection" is the title of a journal article, comprising and resulting from the joint presentation of two scientific papers to th ...

''.

Publication of ''The Origin of Species''

Darwin now worked on an "abstract" trimmed from his ''Natural Selection'' manuscript. The publisher John Murray agreed the title as '' On the Origin of Species through Natural Selection'' and the book went on sale to the trade on 22 November 1859. The stock of 1,250 copies was oversubscribed, and Darwin, still atIlkley

Ilkley is a spa town and civil parish in the City of Bradford in West Yorkshire, in Northern England. Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, Ilkley civil parish includes the adjacent village of Ben Rhydding and is a ward within ...

spa town

A spa town is a resort town based on a mineral spa (a developed mineral spring). Patrons visit spas to "take the waters" for their purported health benefits.

Thomas Guidott set up a medical practice in the English town of Bath, Somerset, Ba ...

, began corrections for a second edition. The novelist Charles Kingsley

Charles Kingsley (12 June 1819 – 23 January 1875) was a broad church priest of the Church of England, a university professor, social reformer, historian, novelist and poet. He is particularly associated with Christian socialism, the workin ...

, a Christian socialist country rector, sent him a letter of praise: "It awes me...if you be right I must give up much that I have believed", it was "just as noble a conception of Deity, to believe that He created primal forms capable of self development... as to believe that He required a fresh act of intervention to supply the lacunas which he himself had made." Darwin added these lines to the last chapter, with attribution to "a celebrated author and divine".

First reviews

The reviewers were less encouraging. Four days before publication, a review in the authoritative '' Athenaeum'' (by John Leifchild, published anonymously, as was the custom at that time) was quick to pick out the unstated implications of "men from monkeys" already controversial from '' Vestiges'', saw snubs to theologians, summing up Darwin's "creed" as man "was born yesterday – he will perish tomorrow" and concluded that "The work deserves attention, and will, we have no doubt, meet with it. Scientific naturalists will take up the author upon his own peculiar ground; and there will we imagine be a severe struggle for at least theoretical existence. Theologians will say—and they have a right to be heard—Why construct another elaborate theory to exclude Deity from renewed acts of creation? Why not at once admit that new species were introduced by the Creative energy of the Omnipotent? Why not accept direct interference, rather than evolutions of law, and needlessly indirect or remote action? Having introduced the author and his work, we must leave them to the mercies of the Divinity Hall, the College, the Lecture Room, and the Museum." At Ilkley, Darwin raged "But the manner in which he drags in immortality, & sets the Priests at me, & leaves me to their mercies, is base. He would on no account burn me; but he will get the wood ready and tell the black beasts how to catch me." Darwin sprained an ankle and his health worsened, as he wrote to friends it was "odious". By 9 December when Darwin leftIlkley

Ilkley is a spa town and civil parish in the City of Bradford in West Yorkshire, in Northern England. Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, Ilkley civil parish includes the adjacent village of Ben Rhydding and is a ward within ...

to come home, he had been told that Murray was organising a second run of 3,000 copies. Hooker had been "converted", Lyell was "absolutely gloating" and Huxley wrote "with such tremendous praise", advising that he was sharpening his "beak and claws" to disembowel "the curs who will bark and yelp".

First response

Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

had been the first to respond to the complimentary copies, courteously claiming that he had long believed that "existing influences" were responsible for the "ordained" birth of species. Darwin now had long talks with him, and told Lyell that "Under garb of great civility, he was inclined to be most bitter & sneering against me. Yet I infer from several expressions, that ''at bottom'' he goes immense way with us." Owen was furious at being included among those defending immutability of species, and in effect said that the book offered the best explanation "ever published of the manner of formation of species", though he did not agree with it in all respects. He still had the gravest doubts that transmutation would bestialise man. It appears that Darwin had assured Owen that he was looking at everything as resulting from designed laws, which Owen interpreted as showing a shared belief in "Creative Power".

Darwin had already made his views clearer to others, telling Lyell that if each step in evolution was providentially planned, the whole procedure would be a miracle and natural selection superfluous. He had also sent a copy to John Herschel

Sir John Frederick William Herschel, 1st Baronet (; 7 March 1792 – 11 May 1871) was an English polymath active as a mathematician, astronomer, chemist, inventor and experimental photographer who invented the blueprint and did botanical work. ...

, and on 10 December he told Lyell of having "heard by round about channel that Herschel says my Book "is the law of higgledy-piggledy".– What this exactly means I do not know, but it is evidently very contemptuous.– If true this is great blow & discouragement." Darwin subsequently corresponded with Herschel, and in January 1861 Herschel added a footnote to the draft of his ''Physical Geography'' which, while disparaging "the principle of arbitrary and casual variation and natural selection" as insufficient without "intelligent direction", said that "with some demur as to the genesis of man, we are far from disposed to repudiate the view taken of this mysterious subject in Mr. Darwin's book."

Geological time

It was known that thegeologic time scale

The geologic time scale or geological time scale (GTS) is a representation of time based on the rock record of Earth. It is a system of chronological dating that uses chronostratigraphy (the process of relating strata to time) and geochro ...

was "incomprehensibly vast", if unquantifiable. From 1848 Darwin discussed data with Andrew Ramsay, who had said "it is vain to attempt to measure the duration of even small portions of geological epochs." A chapter of Lyell's ''Principles of Geology

''Principles of Geology: Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth's Surface, by Reference to Causes Now in Operation'' is a book by the Scottish geologist Charles Lyell that was first published in 3 volumes from 1830 to 1833. ...

'' described the enormous amount of erosion involved in forming the Weald

The Weald () is an area of South East England between the parallel chalk escarpments of the North and the South Downs. It crosses the counties of Hampshire, Surrey, West Sussex, East Sussex, and Kent. It has three parts, the sandstone "High W ...

. To demonstrate the time available for natural selection to operate, Darwin drew on Lyell's example and Ramsay's data in chapter 9 of ''On the Origin of Species'' to estimate that erosion of the Weald's layered dome of Lower Cretaceous rocks "must have required 306,662,400 years; or say three hundred million years."

The "necessary corrections" Darwin made to his drafts for the second edition of the ''Origin'' were based on comments from others, particularly Lyell, and added a caveat suggesting a faster rate of erosion of the Weald: "perhaps it would be safer to allow two or three inches per century, and this would reduce the number of years to one hundred and fifty or one hundred million years." Copies of the second edition were advertised as ready on 24 December, in advance of official publication on 7 January 1860.

The '' Saturday Review'' of 24 December 1859 strongly criticised the methodology of Darwin's calculations. On 3 January 1860, Darwin wrote to Hooker about it: "Some of the remarks about the lapse of years are very good, & the Reviewer gives me some good & well deserved raps,—confound it I am sorry to confess the truth. But it does not at all concern main argument." A day later, he said to Lyell "You saw I suppose Saturday Review: argument confined to Geology, but has given me some perfectly just & severe raps on knuckles."

In the third edition published on 30 April 1861, Darwin cited the ''Saturday Review'' article as reason to remove his calculation altogether.

Friendly reviews

The December 1859 review in the British Unitarian ''National Review

''National Review'' is an American conservative editorial magazine, focusing on news and commentary pieces on political, social, and cultural affairs. The magazine was founded by William F. Buckley Jr. in 1955. Its editor-in-chief is Rich L ...

'' was written by Darwin's old friend William Carpenter, who was clear that only a world of "order, continuity, and progress" befitted an Omnipotent Deity and that "any theological objection" to a species of slug or a breed of dog deriving from a previous one was "simply absurd" dogma. He touched on human evolution, satisfied that the struggle for existence tended "inevitably... towards the progressive exaltation of the races engaged in it".

On Boxing Day

Boxing Day, also called as Offering Day is a holiday celebrated after Christmas Day, occurring on the second day of Christmastide (26 December). Boxing Day was once a day to donate gifts to those in need, but it has evolved to become a part ...

(26 December) ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' carried an anonymous review. The staff reviewer, "as innocent of any knowledge of science as a babe", gave the task to Huxley, leading Darwin to ask his friend how "did you influence Jupiter Olympus and make him give three and a half columns to pure science? The old fogies will think the world will come to an end." Darwin treasured the piece more than "a dozen reviews in common periodicals", but noted "Upon my life I am sorry for Owen... he will be so d—d savage, for credit given to any other man, I strongly suspect, is in his eyes so much credit robbed from him. Science is so narrow a field, it is clear there ought to be only one cock of the walk!".

Hooker also wrote a favourable review, which appeared at the end of December in the ''Gardener's Chronicle'' and treated the theory as an extension of horticultural lore.

Clerical concern, atheist enthusiasm

In his lofty position at the head of Natural History Collections at theBritish Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

, Owen received numerous complaints about the book. The Revd. Adam Sedgwick, geologist at the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

who had taken Darwin on his first geology field trip, could not see the point in a world without providence. The missionary David Livingstone

David Livingstone (; 19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, pioneer Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society, and an explorer in Africa. Livingstone was married to Mary Moffat Livings ...

could see no struggle for existence on the African plains. Jeffries Wyman at Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher lear ...

saw no truth in chance variations.

The most enthusiastic response came from atheists, with Hewett Watson

Hewett Cottrell Watson (9 May 1804 – 27 July 1881) was a phrenologist, botanist and evolutionary theorist. He was born in Firbeck, near Rotherham, Yorkshire, and died at Thames Ditton, Surrey.

Biography

Watson was the eldest son of Holland ...

hailing Darwin as the "greatest revolutionist in natural history of this century". The 68-year-old Robert Edmund Grant, who had shown him the study of invertebrates when Darwin was a student at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

and who was still teaching Lamarckian evolution weekly at University College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

, brought out a small book on classification dedicated to Darwin: "With one fell-sweep of the wand of truth, you have now scattered to the winds the pestilential vapours accumulated by 'species-mongers'."

Widespread interest

In January 1860, Darwin told Lyell of a reported incident at Waterloo Bridge Station: "I never till to day realised that it was getting widely distributed; for in a letter from a lady today to Emma, she says she heard a man enquiring for it at Railway Station!!! at Waterloo Bridge; & the Bookseller said that he had none till new Edit. was out.— The Bookseller said he had not read it but had heard it was a very remarkable book!!!"Asa Gray in the United States

In December 1859 thebotanist

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

Asa Gray

Asa Gray (November 18, 1810 – January 30, 1888) is considered the most important American botany, botanist of the 19th century. His ''Darwiniana'' (1876) was considered an important explanation of how religion and science were not necessaril ...

negotiated with a Boston publisher for publication of an authorised American version, however, he learnt that two New York publishing firms were already planning to exploit the absence of international copyright

A copyright is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the exclusive legal right to copy, distribute, adapt, display, and perform a creative work, usually for a limited time. The creative work may be in a literary, artistic, ...

to print ''Origin''. Darwin wrote in January, "I never dreamed of my Book being so successful with general readers: I believe I should have laughed at the idea of sending the sheets to America." and asked Gray to keep any profits. Gray managed to negotiate a 5 per cent royalty with Appleton's of New York, who got their edition out in mid January, and the other two withdrew. In a May letter Darwin mentioned a print run of 2,500 copies, but it is not clear if this was the first printing alone as there were four that year.

When sending his ''Historical preface'' and corrections for the American edition in February, Darwin thanked Asa Gray for his comments, as "a Review from a man, who is not an entire convert, if fair & moderately favourable, is in all respects the best kind of Review. About weak points I agree. The eye

An eye is a sensory organ that allows an organism to perceive visual information. It detects light and converts it into electro-chemical impulses in neurons (neurones). It is part of an organism's visual system.

In higher organisms, the ey ...

to this day gives me a cold shudder, but when I think of the fine known gradations, my reason tells me I ought to conquer the cold shudder." In April he continued, "It is curious that I remember well time when the thought of the eye made me cold all over, but I have got over this stage of the complaint, & now small trifling particulars of structure often make me very uncomfortable. The sight of a feather in a peacock's tail, whenever I gaze at it, makes me sick!" A month later Darwin emphasised that he was bewildered by the theological

Theology is the study of religious belief from a religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of an ...

aspects and "had no intention to write atheistically, ''but could not'' see, as plainly as others do, & as I shd wish to do, evidence of design & beneficence on all sides of us. There seems to me too much misery in the world. I cannot persuade myself that a beneficent and omnipotent God would have designedly created the Ichneumonidae with the express intention of their feeding within the living bodies of caterpillars" – expressing his particular revulsion at the Ichneumonidae

The Ichneumonidae, also known as ichneumon wasps, ichneumonid wasps, ichneumonids, or Darwin wasps, are a family of parasitoid wasps of the insect order Hymenoptera. They are one of the most diverse groups within the Hymenoptera with roughly 25 ...

family of parasitic wasps that lay their eggs in the larvae and pupae of other insects so that their parasitoid

In evolutionary ecology, a parasitoid is an organism that lives in close association with its host (biology), host at the host's expense, eventually resulting in the death of the host. Parasitoidism is one of six major evolutionarily stable str ...

young have a ready source of food. He therefore could not believe in the necessity of design, but rather than attributing the wonders of the universe to brute force was "inclined to look at everything as resulting from designed laws, with the details, whether good or bad, left to the working out of what we may call chance. Not that this notion at all satisfies me. I feel most deeply that the whole subject is too profound for the human intellect. A dog might as well speculate on the mind of Newton" – referring to Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

.

Erasmus and Martineau

Darwin's brotherErasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus ( ; ; 28 October c. 1466 – 12 July 1536), commonly known in English as Erasmus of Rotterdam or simply Erasmus, was a Dutch Christian humanist, Catholic priest and Catholic theology, theologian, educationalist ...

reported on 23 November that their cousin Henry Holland was reading the book and in "a dreadful state of indecision", sure that explaining the eye would be "utterly impossible", but after reading it "he hummed & hawed & perhaps it was partly conceivable". Erasmus himself thought it "the most interesting book I ever read", and sent a copy to his old flame Miss Harriet Martineau

Harriet Martineau (12 June 1802 – 27 June 1876) was an English social theorist.Hill, Michael R. (2002''Harriet Martineau: Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives'' Routledge. She wrote from a sociological, holism, holistic, religious and ...

who, at 58, was still reviewing from her home in the Lake District

The Lake District, also known as ''the Lakes'' or ''Lakeland'', is a mountainous region and National parks of the United Kingdom, national park in Cumbria, North West England. It is famous for its landscape, including its lakes, coast, and mou ...

. Martineau sent her thanks, adding that she had previously praised "the quality & conduct of your brother's mind, but it is an unspeakable satisfaction to see here the full manifestation of its earnestness & simplicity, its sagacity, its industry, & the patient power by wh. it has collected such a mass of facts, to transmute them by such sagacious treatment into such portentious knowledge. I shd. much like to know how large a proportion of our scientific men believe he has found a sound road."

Writing to her fellow Malthusian

Malthusianism is a theory that population growth is potentially exponential, according to the Malthusian growth model, while the growth of the food supply or other resources is linear, which eventually reduces living standards to the point of trig ...

(and atheist) George Holyoake

George Jacob Holyoake (13 April 1817 – 22 January 1906) was an English secularist, British co-operative movement, co-operator and newspaper editor. He coined the terms secularism in 1851 and "jingoism" in 1878. He edited a secularist paper, '' ...

she enthused, "What a book it is! – overthrowing (if true) revealed Religion on the one hand, & Natural (as far as Final Causes & Design are concerned) on the other. The range & mass of knowledge take away one's breath." To Fanny Wedgwood she wrote, "I rather regret that C.D. went out of his way two or three times to speak of "The Creator" in the popular sense of the First Cause.... His subject is the 'Origin of Species' & not the origin of Organisation; & it seems a needless mischief to have opened the latter speculation at all – There now! I have delivered my mind."

Clerical reaction

The Revd.Adam Sedgwick

Adam Sedgwick FRS (; 22 March 1785 – 27 January 1873) was a British geologist and Anglican priest, one of the founders of modern geology. He proposed the Cambrian and Devonian period of the geological timescale. Based on work which he did ...

had received his copy "with more pain than pleasure." Without Creation showing divine love, "humanity, to my mind, would suffer a damage that might brutalise it, and sink the human race..." He indicated that unless Darwin accepted God's revelation in nature and scripture, Sedgwick would not meet Darwin in heaven, a sentiment that upset Emma. The Revd. John Stevens Henslow

John Stevens Henslow (6 February 1796 – 16 May 1861) was an English Anglican priest, botanist and geologist. He is best remembered as friend and mentor to Charles Darwin.

Early life

Henslow was born at Rochester, Kent, the son of a solicit ...

, the botany professor whose natural history course Charles had joined thirty years earlier, gave faint praise to the ''Origin'' as "a stumble in the right direction" but distanced himself from its conclusions, "a question past our finding out..."

The Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

establishment predominantly opposed Darwin. Palmerston, who became Prime Minister in June 1859, mooted Darwin's name to Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

as a candidate for the Honours List with the prospect of a knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

hood. While Prince Albert

Prince Albert most commonly refers to:

*Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1819–1861), consort of Queen Victoria

*Albert II, Prince of Monaco (born 1958), present head of state of Monaco

Prince Albert may also refer to:

Royalty

* Alb ...

supported the idea, after the publication of the ''Origin'' Queen Victoria's ecclesiastical advisers, including the Bishop of Oxford

The Bishop of Oxford is the diocesan bishop of the Church of England Diocese of Oxford in the Province of Canterbury; his seat is at Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford. The current bishop is Steven Croft (bishop), Steven Croft, following the Confirm ...

Samuel Wilberforce

Samuel Wilberforce, Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (7 September 1805 – 19 July 1873) was an English bishop in the Church of England, and the third son of William Wilberforce. Known as "Soapy Sam", Wilberforce was one of the greatest public sp ...

, dissented and the request was denied. Some Anglicans were more in favour, and Huxley reported of Kingsley that "He is an excellent Darwinian to begin with, and told me a capital story of his reply to Lady Aylesbury who expressed astonishment at his favouring such a heresy – 'What can be more delightful to me Lady Aylesbury, than to know that your Ladyship & myself sprang from the same toad stool.' Whereby the frivolous old woman shut up, in doubt whether she was being chaffed or adored for her remark."

There was no official comment from the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Geography

* Vatican City, an independent city-state surrounded by Rome, Italy

* Vatican Hill, in Rome, namesake of Vatican City

* Ager Vaticanus, an alluvial plain in Rome

* Vatican, an unincorporated community in the ...

for several decades, but in 1860 a council of the German Catholic bishops pronounced that the belief that "man as regards his body, emerged finally from the spontaneous continuous change of imperfect nature to the more perfect, is clearly opposed to Sacred Scripture and to the Faith." This defined the range of official Catholic discussion of evolution, which has remained almost exclusively concerned with human evolution

''Homo sapiens'' is a distinct species of the hominid family of primates, which also includes all the great apes. Over their evolutionary history, humans gradually developed traits such as Human skeletal changes due to bipedalism, bipedalism, de ...

.

Huxley and Owen

On 10 February 1860 Huxley gave a lecture titled ''On Species and Races, and their Origin'' at the

On 10 February 1860 Huxley gave a lecture titled ''On Species and Races, and their Origin'' at the Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

, reviewing Darwin's theory with fancy pigeon

Fancy pigeon refers to any breed of domestic pigeon, which is a domesticated form of the wild rock dove (''Columba livia''). They are bred by pigeon fanciers for various traits relating to size, shape, color, and behavior, and often exhibited at pi ...

s on hand to demonstrate artificial selection

Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant ...

, as well as using the occasion to confront the clergy with his aim of wresting science from ecclesiastical control. He referred to Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

's persecution by the church, "the little Canutes of the hour enthroned in solemn state, bidding that great wave to stay, and threatening to check its beneficent progress." He hailed the ''Origin'' as heralding a "new Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

" in a battle against "those who would silence and crush" science, and called on the public to cherish Science and "follow her methods faithfully and implicitly in their application to all branches of human thought," for the future of England.

To Darwin such rhetoric was "time wasted" and on reflection he thought the lecture "an entire failure ''which'' gave no just idea of ''natural'' selection," but by March he was listing those on "our side" as against the "outsiders." His close allies were Hooker and Huxley, and in August he called Huxley his "good and kind agent for the propagation of the Gospel – i.e. the devil's gospel."

The position of Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

was unknown: when emphasising to a Parliamentary committee the need for a new Natural History museum, he pointed out that "The whole intellectual world this year has been excited by a book on the origin of species; and what is the consequence? Visitors come to the British Museum, and they say, 'Let us see all these varieties of pigeons: where is the tumbler, where is the pouter?' and I am obliged with shame to say, I can show you none of them..." As to showing you the varieties of those species, or of any of those phenomena that would aid one in getting at that mystery of mysteries, the origin of species, our space does not permit; but surely there ought to be a space somewhere, and, if not in the British Museum, where is it to be obtained?"

Huxley's April review in the ''Westminster Review

The ''Westminster Review'' was a quarterly United Kingdom, British publication. Established in 1823 as the official organ of the Philosophical Radicals, it was published from 1824 to 1914. James Mill was one of the driving forces behind the libe ...

'' included the first mention of the term "Darwinism

''Darwinism'' is a term used to describe a theory of biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others. The theory states that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural sel ...

" in the question, "What if the orbit of Darwinism should be a little too circular?" Darwin thought it a "brilliant review."

Overflowing the narrow bounds of purely scientific circles, the "species question" divides with Italy and the Volunteers the attention of general society. Everybody has read Mr. Darwin's book, or, at least, has given an opinion upon its merits or demerits; pietists, whether lay or ecclesiastic, decry it with the mild railing which sounds so charitable; bigots denounce it with ignorant invective; old ladies of both sexes consider it a decidedly dangerous book, and even savants, who have no better mud to throw, quote antiquated writers to show that its author is no better than an ape himself; while every philosophical thinker hails it as a veritable Whitworth gun in the armoury of liberalism; and all competent naturalists and physiologists, whatever their opinions as to the ultimate fate of the doctrines put forth, acknowledge that the work in which they are embodied is a solid contribution to knowledge and inaugurates a new epoch in natural history. – Thomas Huxley, 1860When Owen's own anonymous review of the ''Origin'' appeared in the April ''

Edinburgh Review

The ''Edinburgh Review'' is the title of four distinct intellectual and cultural magazines. The best known, longest-lasting, and most influential of the four was the third, which was published regularly from 1802 to 1929.

''Edinburgh Review'', ...

'' he praised himself and his own ''axiom of the continuous operation of the ordained becoming of living things'', and showed his anger at what he saw as Darwin's caricature of the creationist position and ignoring Owen's pre-eminence. To him, new species appeared at birth, not through natural selection. As well as attacking Darwin's "disciples" Hooker and Huxley, he thought that the book symbolised the sort of "abuse of science to which a neighbouring nation, some seventy years since, owed its temporary degradation." Darwin had Huxley and Hooker staying with him when he read it, and he wrote telling Lyell that it was "extremely malignant, clever & I fear will be very damaging. He is atrociously severe on Huxley's lecture, & very bitter against Hooker. So we three enjoyed it together: not that I really enjoyed it, for it made me uncomfortable for one night; but I have got quite over it today. It requires much study to appreciate all the bitter spite of many of the remarks against me; indeed I did not discover all myself.– It scandalously misrepresents many parts. .... It is painful to be hated in the intense degree with which Owen hates me." He commented to Henslow that "Owen is indeed very spiteful. He misrepresents & alters what I say very unfairly. .... The Londoners says he is mad with envy because my book has been talked about: what a strange man to be envious of a naturalist like myself, immeasurably his inferior!"

Geological time and Phillips

Darwin's had estimated that erosion of theWeald

The Weald () is an area of South East England between the parallel chalk escarpments of the North and the South Downs. It crosses the counties of Hampshire, Surrey, West Sussex, East Sussex, and Kent. It has three parts, the sandstone "High W ...

would take 300 million years, but in the second edition of ''On the Origin of Species'' published on 7 January 1860 he accepted that it would be safer to allow 150 million to 200 million years.

Geologists knew the earth was ancient, but had felt unable to put realistic figures on the duration of past geological changes. Darwin's book provided a new impetus to quantifying geological time. His most prominent critic, John Phillips, had investigated how temperatures increased with depth in the 1830s, and was convinced that, contrary to Lyell and Darwin's uniformitarianism

Uniformitarianism, also known as the Doctrine of Uniformity or the Uniformitarian Principle, is the assumption that the same natural laws and processes that operate in our present-day scientific observations have always operated in the universe in ...

, the Earth was cooling over the long term. Between 1838 and 1855 he tried various ways of quantifying the timing of stratified deposits, without success. On 17 February 1860, Phillips used his presidential address to the Geological Society of London

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe, with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

to accuse Darwin of "abuse of arithmetic". He said 300 million years was an "inconceivable number" and that, depending on assumptions, erosion of the Weald could have taken anything from 12,000 years to at most 1,332,000 years, well below Darwin's estimate. When giving the May 1860 Rede Lecture, Phillips produced his own first published estimates of the duration of the whole stratigraphic record, using rates of sedimentation to calculate it at around 96 million years.

Natural persecution

Most reviewers wrote with great respect, deferring to Darwin's eminent position in science though finding it hard to understand how natural selection could work without a divine selector. There were hostile comments, at the start of May he commented to Lyell that he had "received in a Manchester Newspaper a rather a good squib, showing that I have proved ' might is right', & therefore that Napoleon is right & every cheating Tradesman is also right". The '' Saturday Review'' reported that "The controversy excited by the appearance of Darwin's remarkable work on the ''Origin of Species'' has passed beyond the bounds of the study and lecture-room into the drawing-room and the public street." The older generation of Darwin's tutors were rather negative, and later in May he told his cousin Fox that "the attacks have been falling thick & heavy on my now case-hardened hide.— Sedgwick & Clarke opened regular battery on me lately at Cambridge Phil. Socy. & dear old Henslow defended me in grand style, saying that my investigations were perfectly legitimate." While defending Darwin's honest motives and belief that "he was exalting & not debasing our views of a Creator, in attributing to him a power of imposing laws on the Organic World by which to do his work, as effectually as his laws imposed upon the inorganic had done it in the Mineral Kingdom", Henslow had not disguised his own opinion that "Darwin has pressed his hypothesis too far". In June,Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

saw the book as a "bitter satire" that showed "a basis in natural science for class struggle in history", in which "Darwin recognizes among beasts and plants his English society".

Darwin remarked to Lyell, "I must be a very bad explainer... Several Reviews, & several letters have shown me too clearly how little I am understood. I suppose ''natural selection'' was bad term; but to change it now, I think, would make confusion worse confounded. Nor can I think of better; ''Natural preservation'' would not imply a preservation of particular varieties & would seem a truism; & would not bring man's & nature's selection under one point of view. I can only hope by reiterated explanations finally to make matter clearer." It was too illegible for Lyell, and Darwin later apologised "I am utterly ashamed & groan over my hand-writing. It was ''Natural Preservation''. Natural persecution is what the author ought to suffer."

Debate

''Essays and Reviews''

Around February 1860 liberal theologians entered the fray, when seven produced a manifesto titled ''Essays and Reviews

''Essays and Reviews'', published by John William Parker in March 1860, is a Broad church, broad-church volume of seven essays on Christianity. The topics covered the biblical research of the German critics, the evidence for Christianity, religio ...

''. These Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

s included Oxford professors, country clergymen, the headmaster of Rugby school

Rugby School is a Public school (United Kingdom), private boarding school for pupils aged 13–18, located in the town of Rugby, Warwickshire in England.

Founded in 1567 as a free grammar school for local boys, it is one of the oldest independ ...

and a layman. Their declaration that miracles were irrational stirred up unprecedented anger, drawing much of the fire away from Darwin. ''Essays'' sold 22,000 copies in two years, more than the ''Origin'' sold in twenty years, and sparked five years of increasingly polarised debate with books and pamphlets furiously contesting the issues.

The most scientific of the seven was the Reverend Baden Powell, who held the Savilian chair of geometry at the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

. Referring to "Mr Darwin's masterly volume" and restating his argument that God is a lawgiver, miracles break the lawful edicts issued at Creation, therefore belief in miracles is atheistic, he wrote that the book "must soon bring about an entire revolution in opinion in favour of the grand principle of the self-evolving powers of nature." He drew attacks, with Sedgwick accusing him of "greedily" adopting nonsense and Tory

A Tory () is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The To ...

reviews saying he was joining "the infidel party". He would have been on the platform at the British Association debate, facing the bishop, but died of a heart attack on 11 June.

The British Association debate

The most famous confrontation took place at a meeting of theBritish Association for the Advancement of Science

The British Science Association (BSA) is a Charitable organization, charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Scienc ...

in Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

on Saturday 30 June 1860. While there was no formal debate organised on the issue, Professor John William Draper

John William Draper (May 5, 1811 – January 4, 1882) was an English polymath: a scientist, philosopher, physician, chemist, historian and photographer. He is credited with pioneering portrait photography (1839–40) and producing the first deta ...

of New York University

New York University (NYU) is a private university, private research university in New York City, New York, United States. Chartered in 1831 by the New York State Legislature, NYU was founded in 1832 by Albert Gallatin as a Nondenominational ...

was to talk on Darwin and social progress at a routine "Botany and Zoology" meeting. The new museum hall was crowded with clergy, undergraduates, Oxford dons and gentlewomen anticipating that Samuel Wilberforce

Samuel Wilberforce, Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (7 September 1805 – 19 July 1873) was an English bishop in the Church of England, and the third son of William Wilberforce. Known as "Soapy Sam", Wilberforce was one of the greatest public sp ...

, the Bishop of Oxford, would speak to repeat the savage trouncing he had given in 1847 to the ''Vestiges'' published anonymously by Robert Chambers. Owen lodged with Wilberforce the night before, but Wilberforce would have been well prepared as he had just reviewed the ''Origin'' for the Tory ''Quarterly'' for a fee of ÂŁ60. Huxley was not going to wait for the meeting, but met Chambers who accused him of "deserting them" and changed his mind. Darwin was taking treatment at Dr. Lane's new hydropathic establishment at Sudbrooke Park, Petersham, near Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, a city in the United States

* Richmond, London, a town in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, England

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town ...

in Surrey.

From Hooker's account, Draper "droned on for an hour", then for half an hour "Soapy Sam" Wilberforce replied with the eloquence that had earned him his nickname. This time the climate of opinion had changed and the ensuing debate was more evenly matched, with Hooker being particularly successful in defence of Darwin's ideas. In response to what Huxley took as a jibe from Wilberforce as to whether it was on Huxley's grandfather's or grandmother's side that he was descended from an ape, Huxley made a reply which he later recalled as being that " f askedwould I rather have a miserable ape for a grandfather or a man highly endowed by nature and possessed of great means and influence and yet who employs these faculties and that influence for the mere purpose of introducing ridicule into a grave scientific discussion I unhesitatingly affirm my preference for the ape". No verbatim record was taken: eyewitness accounts exist, and vary somewhat.

From Hooker's account, Draper "droned on for an hour", then for half an hour "Soapy Sam" Wilberforce replied with the eloquence that had earned him his nickname. This time the climate of opinion had changed and the ensuing debate was more evenly matched, with Hooker being particularly successful in defence of Darwin's ideas. In response to what Huxley took as a jibe from Wilberforce as to whether it was on Huxley's grandfather's or grandmother's side that he was descended from an ape, Huxley made a reply which he later recalled as being that " f askedwould I rather have a miserable ape for a grandfather or a man highly endowed by nature and possessed of great means and influence and yet who employs these faculties and that influence for the mere purpose of introducing ridicule into a grave scientific discussion I unhesitatingly affirm my preference for the ape". No verbatim record was taken: eyewitness accounts exist, and vary somewhat.

Robert FitzRoy

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy (5 July 1805 – 30 April 1865) was an English officer of the Royal Navy, politician and scientist who served as the second governor of New Zealand between 1843 and 1845. He achieved lasting fame as the captain of ...

, who had been the captain of during Darwin's voyage, was there to present a paper on storms. During the debate FitzRoy, seen by Hooker as "a grey haired Roman nosed elderly gentleman", stood in the centre of the audience and "lifting an immense Bible first with both and afterwards with one hand over his head, solemnly implored the audience to believe God rather than man". As he admitted that the ''Origin of Species'' had given him "acutest pain" the crowd shouted him down.

Hooker's "blood boiled, I felt myself a dastard; now I saw my advantage–I swore to myself I would smite that Amalek

Amalek (; ) is described in the Hebrew Bible as the enemy of the nation of the Israelites. The name "Amalek" can refer to the descendants of Amalek, the grandson of Esau, or anyone who lived in their territories in Canaan, or North African descend ...

ite Sam hip and thigh", (he was invited up to the platform and) "there and then I smacked him amid rounds of applause... proceeded to demonstrate... that he could never have read your book... wound up with a very few observations on the...old and new hypotheses... Sam was shut up... and the meeting was dissolved forthwith leaving you arwin

The following is a list of recurring and minor characters in the List of Disney Channel series, Disney Channel Original Series ''The Suite Life of Zack & Cody''. These characters were regularly rotated, often disappearing for long periods during ...

master of the field after 4 hours battle."

Both sides came away claiming victory, with Hooker and Huxley each sending Darwin rather contradictory triumphant accounts. Supporters of Darwinism seized on this meeting as a sign that the idea of evolution could not be suppressed by authority, and would be defended vigorously by its advocates. Liberal clerics were also satisfied that literal belief in all aspects of the Bible was now questioned by science; they were sympathetic to some of the ideas in ''Essays and Reviews

''Essays and Reviews'', published by John William Parker in March 1860, is a Broad church, broad-church volume of seven essays on Christianity. The topics covered the biblical research of the German critics, the evidence for Christianity, religio ...

''. William Whewell

William Whewell ( ; 24 May 17946 March 1866) was an English polymath. He was Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. In his time as a student there, he achieved distinction in both poetry and mathematics.

The breadth of Whewell's endeavours is ...

wrote to his friend James David Forbes

James David Forbes (1809–1868) was a Scottish physicist and glaciologist who worked extensively on the conduction of heat and seismology. Forbes was a resident of Edinburgh for most of his life, educated at its University and a professor ...

that "Perhaps the Bishop was not prudent to venture into a field where no eloquence can supersede the need for precise knowledge. The young naturalists declared themselves in favour of Darwin’s views which tendency I saw already at Leeds two years ago. I am sorry for it, for I reckon Darwin’s book to be an utterly unphilosophical one.",Letter to James D, Forbes (24 Jul 1860)

Wilberforce's ''Quarterly'' review

In late July Darwin read Wilberforce's review in the ''Quarterly''. It used a 60-year-old parody from the '' Anti-Jacobin'' of the prose of Darwin's grandfatherErasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus ( ; ; 28 October c. 1466 – 12 July 1536), commonly known in English as Erasmus of Rotterdam or simply Erasmus, was a Dutch Christian humanist, Catholic priest and Catholic theology, theologian, educationalist ...

, implying old revolutionary sympathies. It argued that if "transmutations were actually occurring" this would be seen in rapidly reproducing invertebrates, and since it isn't, why think that "the favourite varieties of turnips are tending to become men". Darwin pencilled "rubbish" in the margin. To the statement about classification that "all creation is the transcript in matter of ideas eternally existing in the mind of the Most High!!", Darwin scribbled "mere words". At the same time, Darwin was willing to grant that Wilberforce's review was clever: he wrote to Hooker that "it picks out with skill all the most conjectural parts, and brings forward well all the difficulties. It quizzes me quite splendidly by quoting the 'Anti-Jacobin' against my Grandfather."

Wilberforce also attacked ''Essays and Reviews

''Essays and Reviews'', published by John William Parker in March 1860, is a Broad church, broad-church volume of seven essays on Christianity. The topics covered the biblical research of the German critics, the evidence for Christianity, religio ...

'' in the ''Quarterly Review

The ''Quarterly Review'' was a literary and political periodical founded in March 1809 by London publishing house John Murray. It ceased publication in 1967. It was referred to as ''The London Quarterly Review'', as reprinted by Leonard Scott, f ...

'', and in a letter to ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'', signed by the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

and 25 bishops, which threatened the theologians with the ecclesiastical courts. Darwin quoted a proverb: "A bench of bishops is the devil's flower garden", and joined others including Lyell, though not Hooker and Huxley, in signing a counter-letter supporting ''Essays and Reviews'' for trying to "establish religious teachings on a firmer and broader foundation". Despite this alignment of pro-evolution scientists and Unitarians with liberal churchmen, two of the authors were indicted for heresy and lost their jobs by 1862.

Geological time, Phillips and third edition

In October 1860, John Phillips published ''Life on the Earth, its origin and succession'', reiterating points from his Rede Lecture and disputing Darwin's arguments. He sent a copy to Darwin, who thanked him, though "sorry, but not surprised, to see that you are dead against me". On 20 November, Darwin told Lyell of his revisions for a third edition of the ''Origin'', including removing his estimate of the time it took for theWeald

The Weald () is an area of South East England between the parallel chalk escarpments of the North and the South Downs. It crosses the counties of Hampshire, Surrey, West Sussex, East Sussex, and Kent. It has three parts, the sandstone "High W ...

to erode: "The confounded Wealden calculation, to be struck out. & a note to be inserted to effect that I am convinced of its inaccuracy from Review in Saturday R. & from Phillips, as I see in Table of Contents that he attacks it." He later told Lyell that "Having burnt my own fingers so consumedly with the Wealden, I am fearful for you", and advised caution: "for Heaven-sake take care of your fingers; to burn them severely, as I have done, is very unpleasant." The third edition, as published on 30 April 1861, stated "The computation of time required for the denudation of the Weald omitted. I have been convinced of its inaccuracy in several respects by an excellent article in the 'Saturday Review,' Dec. 24, 1859."

''Natural History Review''

The '' Natural History Review'' was bought and refurbished by Huxley, Lubbock, Busk and other "plastically minded young men" – supporters of Darwin. The first issue in January 1861 carried Huxley's paper on man's relationship to apes, "showing up" Owen. Huxley cheekily sent a copy to Wilberforce.Darwin at home

As the battles raged, Darwin returned home from the spa to proceed with experiments onchloroform

Chloroform, or trichloromethane (often abbreviated as TCM), is an organochloride with the formula and a common solvent. It is a volatile, colorless, sweet-smelling, dense liquid produced on a large scale as a precursor to refrigerants and po ...

ing carnivorous sundew plants, looking over his ''Natural Selection'' manuscript and drafting two chapters on pigeon breeding that would eventually form part of ''The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication

''The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication'' is a book by Charles Darwin that was first published in January 1868.

A large proportion of the book contains detailed information on the domestication of animals and plants but it al ...

''. He wrote to Asa Gray

Asa Gray (November 18, 1810 – January 30, 1888) is considered the most important American botany, botanist of the 19th century. His ''Darwiniana'' (1876) was considered an important explanation of how religion and science were not necessaril ...

and used the example of fantail pigeons to argue against Gray's belief "that variation has been led along certain beneficial lines", with the implication of Creationism rather than Natural Selection.

Over the winter he organised a third edition of the ''Origin'', adding an introductory historical sketch. Asa Gray had published three supportive articles in the ''Atlantic Monthly

''The Atlantic'' is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher based in Washington, D.C. It features articles on politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.

It was founded in 1857 ...

''. Darwin persuaded Gray to publish them as a pamphlet, and was delighted when Gray came up with the title of ''Natural Selection Not Inconsistent with Natural Theology''. Darwin paid half the cost, imported 250 copies into Britain and as well as advertising it in periodicals and sending 100 copies out to scientists, reviewers, and theologians (including Wilberforce), he included in the ''Origin'' a recommendation for it, available to be purchased for 1s. 6d. from TrĂĽbner's in Paternoster Row.

The Huxleys became close family friends, frequently visiting Down House

Down House is the former home of the English Natural history, naturalist Charles Darwin and his family. It was in this house and garden that Darwin worked on his theory of evolution by natural selection, which he had conceived in London befor ...

. When their 3-year-old son died of scarlet fever they were badly affected. Henrietta Huxley brought their three infants to Down in March 1861 where Emma helped to console her, while Huxley continued with his working-men's lectures at the Royal School of Mines

The Royal School of Mines comprises the departments of Earth Science and Engineering, and Materials at Imperial College London. The Centre for Advanced Structural Ceramics and parts of the London Centre for Nanotechnology and Department of Bioe ...

, writing that "My working men stick with me wonderfully, the house fuller than ever, By next Friday evening they will all be convinced that they are monkeys."

Arguments with Owen

Huxley's arguments with Owen continued in the '' Athenaeum'' so that each Saturday Darwin could read the latest ripostes. Owen tried to smear Huxley by portraying him as an "advocate of man's origins from a transmuted ape", and one of his contributions was titled "Ape-Origin of Man as Tested by the Brain". This backfired, as Huxley had already delighted Darwin by speculating on "pithecoid man" – ape-like man, and was glad of the invitation to publicly turn the anatomy of brain structure into a question of human ancestry. He was determined to indict Owen for perjury, promising "before I have done with that mendacious humbug I will nail him out, like a kite to a barn door, an example to all evil doers." Darwin egged him on from Down, writing "Oh Lord what a thorn you must be in the poor dear man's side". Their campaign ran over two years and was devastatingly successful, with each "slaying" being followed by a recruiting drive for the Darwinian cause. The spite lingered. When Huxley joined the Zoological Society Council in 1861, Owen left, and in the following year Huxley moved to stop Owen from being elected to the Royal Society Council as "no body of gentlemen" should admit a member "guilty of wilful & deliberate falsehood." Lyell was troubled both by Huxley's belligerence and by the question of ape ancestry, but got little sympathy from Darwin who teased him that "''Our'' ancestor was an animal which breathed water, had a swim bladder, a great swimming tail, an imperfect skull, and undoubtedly was a hermaphrodite! Here is a pleasant genealogy for mankind." Lyell began work on a book examining human origins.Geological time: William Thomson (Lord Kelvin)

Like the geologist John Phillips, the physicist William Thomson (later ennobled as Baron Kelvin of Largs, thus becoming Lord Kelvin) had considered since the 1840s that the physics ofthermodynamics

Thermodynamics is a branch of physics that deals with heat, Work (thermodynamics), work, and temperature, and their relation to energy, entropy, and the physical properties of matter and radiation. The behavior of these quantities is governed b ...

required that the Earth was cooling from an initial molten state. This contradicted Lyell's uniformitarian

Uniformitarianism, also known as the Doctrine of Uniformity or the Uniformitarian Principle, is the assumption that the same natural laws and processes that operate in our present-day scientific observations have always operated in the universe in ...

concept of unchanging processes over deep geological time, which Darwin shared and had assumed would allow ample time for the slow process of natural selection.

In June 1861 Thomson asked Phillips how geologists felt about Darwin's "prodigious durations for geological epochs". and mentioned his own preliminary calculation that the Sun was 20 million years old, with the Earth at most 200 to 1,000 million years old. Phillips discussed his own published view that stratified rocks went back 96 million years, and dismissed Darwin's original estimate that the Weald

The Weald () is an area of South East England between the parallel chalk escarpments of the North and the South Downs. It crosses the counties of Hampshire, Surrey, West Sussex, East Sussex, and Kent. It has three parts, the sandstone "High W ...

had taken 300 million years to erode. In September 1861 Thomson produced a paper "On the age of the Sun's heat" which estimated that the Sun was between 100 and 500 million years old, and in 1862 he used assumptions on the rate of cooling from a molten condition to estimate the age of the Earth at 98 million years. The dispute continued for the rest of Darwin's life.Thomson, William. (1864).On the secular cooling of the earth

, read 28 April 1862. ''Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh'', 23, 157–170.

Continued debate