Racial Integrity Act on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In 1924, the

In 1924, the

Racial Integrity Laws (1924–1930)

''Encyclopedia Virginia'' . The act, an outgrowth of

''First People: The Early Indians of Virginia'', Dept. of Historic Resources, State of Virginia, accessed 14 April 2010 The club was founded in Virginia by John Powell of

The Racial Integrity Act was subject to the Pocahontas Clause (or Pocahontas Exception), which allowed people with claims of no more than 1/16 American Indian ancestry to still be considered white, despite the otherwise unyielding climate of one-drop rule politics. The exception regarding the American Indian blood quantum was included as an amendment to the original Act in response to concerns of Virginia elites, including many of the

The Racial Integrity Act was subject to the Pocahontas Clause (or Pocahontas Exception), which allowed people with claims of no more than 1/16 American Indian ancestry to still be considered white, despite the otherwise unyielding climate of one-drop rule politics. The exception regarding the American Indian blood quantum was included as an amendment to the original Act in response to concerns of Virginia elites, including many of the

"Sterilization Act of 1924" by N. Antonios at the Embryo Project Encyclopedia

Virginia's Indian People

Eugenics archive

"HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION NO. 607, Expressing the General Assembly's regret for Virginia's experience with eugenics", Feb 14, 2001

* Racial Integrity Act of 1924, Original Text

"Harry H. Laughlin"

''Model Eugenical Sterilization Law'', Harvard University

by Joe Heim, ''Washington Post'' March 20, 2017

by Joe Heim, ''Washington Post'', July 1, 2015 {{Authority control 1924 in American law 1924 in Virginia Legal history of Virginia Race legislation in the United States Interracial marriage in the United States Marriage law in the United States Repealed United States legislation African-American segregation in the United States Native American segregation in the United States African-American history of Virginia Anti-black racism in Virginia Anti-Indigenous racism in Virginia Native American history of Virginia Pocahontas Marriage in Virginia White nationalism in Virginia

In 1924, the

In 1924, the Virginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, the oldest continuous law-making body in the Western Hemisphere, and the first elected legislative assembly in the New World. It was established on July 30, ...

enacted the Racial Integrity Act. The act reinforced racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, ...

by prohibiting interracial marriage

Interracial marriage is a marriage involving spouses who belong to different "Race (classification of human beings), races" or Ethnic group#Ethnicity and race, racialized ethnicities.

In the past, such marriages were outlawed in the United Sta ...

and classifying

Classification is the activity of assigning objects to some pre-existing classes or categories. This is distinct from the task of establishing the classes themselves (for example through cluster analysis). Examples include diagnostic tests, identif ...

as "white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wa ...

" a person "who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian".Brendan WolfeRacial Integrity Laws (1924–1930)

''Encyclopedia Virginia'' . The act, an outgrowth of

eugenicist

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetics, genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human Phenotype, phenotypes by ...

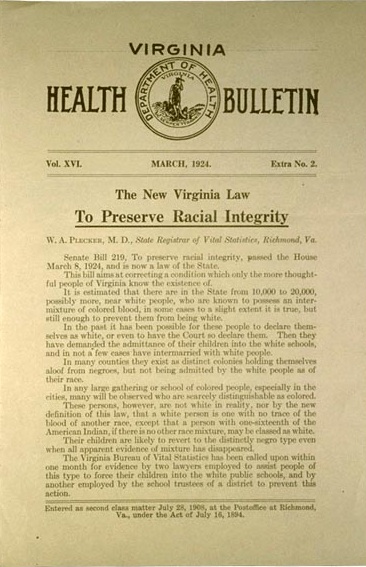

and scientific racist propaganda, was pushed by Walter Plecker, a white supremacist

White supremacy is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White supremacy has roots in the now-discredited doctrine ...

and eugenicist who held the post of registrar of the Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

Bureau of Vital Statistics.

The Racial Integrity Act required that all birth certificate

A birth certificate is a vital record that documents the Childbirth, birth of a person. The term "birth certificate" can refer to either the original document certifying the circumstances of the birth or to a certified copy of or representation ...

s and marriage certificate

A marriage certificate (colloquially marriage lines) is an official statement that two people are married. In most jurisdictions, a marriage certificate is issued by a government official only after the civil registration of the marriage.

In s ...

s in Virginia to include the person's race as either "white" or "colored

''Colored'' (or ''coloured'') is a racial descriptor historically used in the United States during the Jim Crow era to refer to an African American. In many places, it may be considered a slur.

Dictionary definitions

The word ''colored'' wa ...

". The Act classified all non-whites, including Native Americans, as "colored". The act was part of a series of "racial integrity laws" enacted in Virginia to reinforce racial hierarchies and prohibit the mixing of races; other statutes included the Public Assemblages Act of 1926 (which required the racial segregation of all public meeting areas) and a 1930 act that defined any person with even a trace of sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lie south of the Sahara. These include Central Africa, East Africa, Southern Africa, and West Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the list of sovereign states and ...

n ancestry as black

Black is a color that results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without chroma, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness.Eva Heller, ''P ...

(thus codifying the so-called " one-drop rule").

In 1967, the Act was officially overturned by the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

in their ruling ''Loving v. Virginia

''Loving v. Virginia'', 388 U.S. 1 (1967), was a landmark civil rights decision of the U.S. Supreme Court that ruled that the laws banning interracial marriage violate the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to ...

''. In 2001, the Virginia General Assembly passed a resolution that condemned the Act for its "use as a respectable, 'scientific' veneer to cover the activities of those who held blatantly racist views".

History leading to the laws' passage: 1859–1924

In the 1920s, Virginia's registrar of statistics, Walter Ashby Plecker, was allied with the newly founded Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America in persuading theVirginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, the oldest continuous law-making body in the Western Hemisphere, and the first elected legislative assembly in the New World. It was established on July 30, ...

to pass the Racial Integrity Law of 1924."Modern Indians A.D. 1800-Present"''First People: The Early Indians of Virginia'', Dept. of Historic Resources, State of Virginia, accessed 14 April 2010 The club was founded in Virginia by John Powell of

Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, a city in the United States

* Richmond, London, a town in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, England

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town ...

in the fall of 1922; within a year the club for white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wa ...

males had more than 400 members and 31 posts in the state.

In 1923, the Anglo-Saxon Club founded two posts in Charlottesville

Charlottesville, colloquially known as C'ville, is an independent city in Virginia, United States. It is the seat of government of Albemarle County, which surrounds the city, though the two are separate legal entities. It is named after Quee ...

, one for the town and one for students at the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia, United States. It was founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson and contains his The Lawn, Academical Village, a World H ...

. A major goal was to end "amalgamation" by interracial marriage

Interracial marriage is a marriage involving spouses who belong to different "Race (classification of human beings), races" or Ethnic group#Ethnicity and race, racialized ethnicities.

In the past, such marriages were outlawed in the United Sta ...

. Members also claimed to support Anglo-Saxon ideas of fair play. Later that fall, a state convention of club members was to be held in Richmond.

The Virginia assembly's 21st-century explanation for the laws summarizes their development:

The now-discreditedIn the following five decades, other states followed Indiana's example by implementing the eugenic laws.pseudoscience Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable cl ...ofeugenics Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human phenotypes by inhibiting the fer ...was based on theories first propounded inEngland England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...byFrancis Galton Sir Francis Galton (; 16 February 1822 – 17 January 1911) was an English polymath and the originator of eugenics during the Victorian era; his ideas later became the basis of behavioural genetics. Galton produced over 340 papers and b ..., the cousin and disciple of famed biologistCharles Darwin Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci .... The goal of the "science" of eugenics was to improve the human race by eliminating what the movement's supporters consideredhereditary Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic inform ...disorders or flaws throughselective breeding Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant m ...and social engineering. The eugenics movement proved popular in theUnited States The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ..., withIndiana Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...enacting the nation's first eugenics-based sterilization law in 1907.

Wisconsin

Wisconsin ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest of the United States. It borders Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake Michigan to the east, Michig ...

was the first state to enact legislation that required the medical certification of persons who applied for marriage licenses. The law that was enacted in 1913 generated attempts at similar legislation in other states.

Anti-miscegenation laws

Anti-miscegenation laws are laws that enforce racial segregation at the level of marriage and intimate relationships by criminalizing interracial marriage sometimes, also criminalizing sex between members of different races.

In the United Stat ...

, banning interracial marriage between whites and non-whites, had existed long before the emergence of eugenics. First enacted during the colonial era when slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

had become essentially a racial caste

A caste is a Essentialism, fixed social group into which an individual is born within a particular system of social stratification: a caste system. Within such a system, individuals are expected to marry exclusively within the same caste (en ...

, such laws were in effect in Virginia and in much of the United States until the 1960s.

The first law banning all marriage between whites and blacks was enacted in the colony of Virginia

The Colony of Virginia was a British Empire, British colonial settlement in North America from 1606 to 1776.

The first effort to create an English settlement in the area was chartered in 1584 and established in 1585; the resulting Roanoke Colo ...

in 1691. This example was followed by Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

(in 1692) and several of the other Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were the British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America which broke away from the British Crown in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and joined to form the United States of America.

The Thirteen C ...

. By 1913, 30 out of the then 48 states (including all Southern states) enforced such laws.

The Pocahontas exception

The Racial Integrity Act was subject to the Pocahontas Clause (or Pocahontas Exception), which allowed people with claims of no more than 1/16 American Indian ancestry to still be considered white, despite the otherwise unyielding climate of one-drop rule politics. The exception regarding the American Indian blood quantum was included as an amendment to the original Act in response to concerns of Virginia elites, including many of the

The Racial Integrity Act was subject to the Pocahontas Clause (or Pocahontas Exception), which allowed people with claims of no more than 1/16 American Indian ancestry to still be considered white, despite the otherwise unyielding climate of one-drop rule politics. The exception regarding the American Indian blood quantum was included as an amendment to the original Act in response to concerns of Virginia elites, including many of the First Families of Virginia

The First Families of Virginia, or FFV, are a group of early settler families who became a socially and politically dominant group in the British Colony of Virginia and later the Commonwealth of Virginia. They descend from European colonists who ...

, who had always claimed descent from Pocahontas

Pocahontas (, ; born Amonute, also known as Matoaka and Rebecca Rolfe; 1596 – March 1617) was a Native American woman belonging to the Powhatan people, notable for her association with the colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. S ...

with pride, but now worried that the new legislation would jeopardize their status. The exception stated:

It shall thereafter be unlawful for any white person in this State to marry any save a white person, or a person with no other admixture of blood than white and American Indian. For the purpose of this act, the term "white person" shall apply only to the person who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian; but persons who have one-sixteenth or less of the blood of the American Indian and have no other non-Caucasic blood shall be deemed to be white persons.While definitions of "Indian", "colored", and variations of these were established and altered throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, this was the first direct case of whiteness itself being defined officially.

Enforcement

Once these laws were passed, Plecker was in the position to enforce them. Governor E. Lee Trinkle, a year after signing the act, asked Plecker to ease up on the Indians and not "embarrass them any more than possible." Plecker responded, "I am unable to see how it is working any injustice upon them or humiliation for our office to take a firm stand against their intermarriage with white people, or to the preliminary steps of recognition as Indians with permission to attend white schools and to ride in white coaches." Unsatisfied with the "Pocahontas Exception", eugenicists introduced an amendment to narrow loopholes to the Racial Integrity Act. This was considered by the Virginia General Assembly in February 1926, but it failed to pass. If adopted, the amendment would have reclassified thousands of "white" people as "colored" by more strictly implementing the "one-drop rule" of ancestry as applied to American Indian ancestry. Plecker reacted strongly to the Pocahontas Clause with fierce concerns of the white race being "swallowed up by the quagmire of mongrelization", particularly after marriage cases like that of the Johns and Sorrels, in which the women of these couples argued that the family members listed as "colored" had actually been Native American because of historically unclear categorizing.Implementation and consequences: 1924–1979

The combined effect of these two laws adversely affected the continuity of Virginia's American Indian tribes. The Racial Integrity Act called for only two racial categories to be recorded on birth certificates, rather than the traditional six: "white" and "colored" (which now included Indian and all discernible mixed-race persons).Fiske, Part 1 The effects were quickly seen. In 1930, theUS census

The United States census (plural censuses or census) is a census that is legally mandated by the Constitution of the United States. It takes place every ten years. The first census after the American Revolution was taken in 1790 under Secretar ...

for Virginia recorded 779 Indians; by 1940, that number had been reduced to 198. In effect, Indians were being erased as a group from official records.

In addition, as Plecker admitted, he enforced the Racial Integrity Act extending far beyond his jurisdiction in the segregated society.Fiske, Part 2 For instance, he pressured school superintendents to exclude mixed-race

The term multiracial people refers to people who are mixed with two or more

races and the term multi-ethnic people refers to people who are of more than one ethnicities. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mul ...

(then called mulatto

( , ) is a Race (human categorization), racial classification that refers to people of mixed Sub-Saharan African, African and Ethnic groups in Europe, European ancestry only. When speaking or writing about a singular woman in English, the ...

) children from white schools. Plecker ordered the exhumation

Burial, also known as interment or inhumation, is a method of final disposition whereby a dead body is placed into the ground, sometimes with objects. This is usually accomplished by excavating a pit or trench, placing the deceased and object ...

of dead people of "questionable ancestry" from white cemeteries to be reinterred elsewhere.

Indians reclassified as colored

As registrar, Plecker directed the reclassification of nearly all Virginia Indians as ''colored'' on their birth and marriage certificates. Consequently, two or three generations of Virginia Indians had their ethnic identity altered on these public documents. Fiske reported that Plecker's tampering with the vital records of the Virginia Indian tribes made it impossible for descendants of six of the eight tribes recognized by the state to gain federal recognition, because they could no longer prove their American Indian ancestry by documented historical continuity.Involuntary sterilization

Historians have not estimated the impact of the miscegenation laws. There are records, however, of the number of people who were involuntarily sterilized during the years these two laws were in effect. Of the involuntary sterilizations reported in the United States prior to 1957, Virginia was second, having sterilized a total of 6,683 persons (California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

was first, having sterilized 19,985 people without their consent). Many more women than men were sterilized: 4,043 to 2,640. Of those, 2,095 women were sterilized under the category of "Mentally Ill"; and 1,875 under the category "Mentally Deficient". The remainder were for "Other" reasons. Other states reported involuntary sterilizations of similar numbers of people as Virginia.

Leaders target persons of color

The intention to control or reduce ethnic minorities, especiallyNegro

In the English language, the term ''negro'' (or sometimes ''negress'' for a female) is a term historically used to refer to people of Black people, Black African heritage. The term ''negro'' means the color black in Spanish and Portuguese (from ...

es, can be seen in writings by some leaders in the eugenics movement:

In an 1893 "open letter" published in the ''Virginia Medical Monthly'', Hunter Holmes McGuire, aIn 1935, a decade after the passage of Virginia's eugenics laws, Plecker wrote to Walter Gross, director ofRichmond Richmond most often refers to: * Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada * Richmond, California, a city in the United States * Richmond, London, a town in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, England * Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town ...physician A physician, medical practitioner (British English), medical doctor, or simply doctor is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through the Medical education, study, Med ...and president of theAmerican Medical Association The American Medical Association (AMA) is an American professional association and lobbying group of physicians and medical students. This medical association was founded in 1847 and is headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. Membership was 271,660 ..., asked for "some scientific explanation of the sexual perversion in the Negro of the present day." McGuire's correspondent,Chicago Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...physician G. Frank Lydston, replied that African-American men raped white women because of " reditary influences descending from the uncivilized ancestors of our Negroes." Lydston suggested as a solution to perform surgicalcastration Castration is any action, surgery, surgical, chemical substance, chemical, or otherwise, by which a male loses use of the testicles: the male gonad. Surgical castration is bilateral orchiectomy (excision of both testicles), while chemical cas ..., which "prevents the criminal from perpetuating his kind.

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

's Bureau of Human Betterment and Eugenics. Plecker described Virginia's racial purity

The term racial hygiene was used to describe an approach to eugenics in the early 20th century, which found its most extensive implementation in Nazi Germany (Nazi eugenics). It was marked by efforts to avoid miscegenation, analogous to an animal ...

laws and requested to be put on Gross' mailing list. Plecker commented upon the Third Reich's sterilization of 600 children in the Rhineland

The Rhineland ( ; ; ; ) is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly Middle Rhine, its middle section. It is the main industrial heartland of Germany because of its many factories, and it has historic ties to the Holy ...

(the so-called Rhineland Bastards, who were born of German women by black French colonial fathers): "I hope this work is complete and not one has been missed. I sometimes regret that we have not the authority to put some measures in practice in Virginia."

Despite lacking the statutory authority to sterilize black, mulatto, and American Indian children simply because they were "colored", a small number of Virginia eugenicists in key positions found other ways to achieve that goal. The Sterilization Act gave State institutions, including hospitals, psychiatric institutions and prisons, the statutory authority to sterilize persons deemed to be " feebleminded" — a highly subjective criterion.

Joseph DeJarnette

Joseph Spencer DeJarnette (September 29, 1866 – September 3, 1957) was the director of Western State Hospital (located in Staunton, Virginia) from 1905 to November 15, 1943. He was a vocal proponent of racial segregation and eugenics, speci ...

, director of the Western State Hospital in Staunton, Virginia

Staunton ( ) is an independent city (United States), independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 25,750. In Virginia, independent cities a ...

, was a leading advocate of eugenics. DeJarnette was unsatisfied with the pace of America's eugenics sterilization programs. In 1938, he wrote:

Germany in six years has sterilized about 80,000 of her unfit while the United States — with approximately twice the population — has only sterilized about 27,869 in the past 20 years. ... The fact that there are 12,000,000 defectives in the US should arouse our best endeavors to push this procedure to the maximum ... The Germans are beating us at our own game.By "12 million defectives" (a tenth of the population), DeJarnette was almost certainly referring to ethnic minorities, as there have never been 12 million mental patients in the United States. According to

historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human species; as well as the ...

Gregory M. Dorr, the University of Virginia School of Medicine

The University of Virginia School of Medicine (UVA SOM or more commonly known as UVA Medicine) is the graduate medical school of the University of Virginia. The school's facilities are on the University of Virginia grounds adjacent to The Lawn, ...

(UVA) became "an epicenter of eugenical thought" that was "closely linked with the national movement." One of UVA's leading eugenicists, Harvey Ernest Jordan, PhD was promoted to dean of medicine in 1939 and served until 1949. He was in a position to shape the opinion and practice of Virginia physicians for several decades. This excerpt from a 1934 UVA student paper indicates one student's thoughts: "In Germany, Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

has decreed that about 400,000 persons be sterilized. This is a great step in eliminating the racial deficients."

The racial effects of the program in Virginia can be seen by the disproportionately high number of black and American Indian women who were given forced sterilizations after coming to a hospital for other reasons, such as childbirth. Doctors sometimes sterilized the women without their knowledge or consent in the course of other surgery.

Responses to the Racial Integrity Act

In the early 20th century, persons of color in everyday southern society feared to voice their opinions due to severe oppression. Magazines such as the '' Richmond Planet'' offered the black community a voice and the opportunity to have their concerns heard. ''The Richmond Planet'' made a difference in society by openly expressing the opinions of persons of color in society. After the passing of the Racial Integrity Act of 1924 the ''Richmond Planet'' published the article "Race Amalgamation Bill Being Passed in Va. Legislature. Much Discussion Here on race Integrity and Mongrelization ... Bill Would Prohibit Marriage of Whites and Non-whites ..."Skull of Bones" Discusses race question." The journalist opened the article with Racial Integrity Act and gave a brief synopsis of the act. Then followed statements from the creators of the Racial Integrity Act, John Powell and Earnest S. Cox. Mr. Powell believed that the Racial Integrity Act was needed as "maintenance of the integrity of the white race to preserve its superior blood" and Cox believed in what he called "the great man concept" which means that if the races were to intersect that it would lower the rate of great white men in the world. He defended his position by saying that non-whites would agree with his ideology:The sane and educated Negro does not want social equality ... They do not want intermarriage or social mingling any more than does the average American white man wants it. They have race pride as well as we. They want racial purity as much as we want it. There are both sides to the question and to form an unbiased opinion either way requires a thorough study of the matter on both sides.

Carrie Buck and the Supreme Court

Racial minorities were not the only people affected by these laws. About 4,000poor white

Poor White is a sociocultural classification used to describe economically disadvantaged Whites in the English-speaking world, especially White Americans with low incomes.

In the United States, Poor White is the historical classification f ...

Virginians were involuntarily sterilized by government order. When Laughlin testified before the Virginia assembly in support of the Sterilization Act in 1924, he argued that the "shiftless, ignorant, and worthless class of anti-social whites of the South", created social problems for "normal" people. He said, "The multiplication of these 'defective delinquents' could only be controlled by restricting their procreation".

Carrie Buck was the most widely known white victim of Virginia's eugenics laws. She was born in Charlottesville to Emma Buck. After her birth, Carrie was placed with foster parents, John and Alice Dobbs. She attended public school until the sixth grade. After that, she continued to live with the Dobbses, and did domestic work in the home.

Carrie became pregnant when she was 17, as a result of being rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault involving sexual intercourse, or other forms of sexual penetration, carried out against a person without consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or against a person ...

d by the nephew of her foster parents. To hide the act, on January 23, 1924, Carrie's foster parents committed the girl to the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded

The Virginia State Colony for the Epileptics and Feeble Minded was a state run institution for those considered to be “Feeble-minded, Feeble minded” or those with severe mental impairment. The colony opened in 1910 near Lynchburg, Virginia, i ...

on the grounds of feeblemindedness, incorrigible behavior, and promiscuity

Promiscuity is the practice of engaging in sexual activity frequently with different partners or being indiscriminate in the choice of sexual partners. The term can carry a moral judgment. A common example of behavior viewed as promiscuous by man ...

. They did not tell the court the true cause of her pregnancy. On March 28, 1924, Buck gave birth to a daughter, whom she named Vivian. Since Carrie had been declared mentally incompetent to raise her child, her former foster parents adopted the baby.

On September 10, 1924, Albert Sidney Priddy, superintendent of the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded and a eugenicist, filed a petition with his board of directors to sterilize Carrie Buck, an 18-year-old patient. He claimed she had a mental age of 9. Priddy said that Buck represented a genetic threat to society. While the litigation was making its way through the court system, Priddy died and his successor, James Hendren Bell, came on the case.

When the directors issued an order for the sterilization of Buck, her guardian appealed the case to the Circuit Court

Circuit courts are court systems in several common law jurisdictions. It may refer to:

* Courts that literally sit 'on circuit', i.e., judges move around a region or country to different towns or cities where they will hear cases;

* Courts that s ...

of Amherst County. It sustained the decision of the board. The case then moved to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, where it was upheld. It was appealed to the US Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all Federal tribunals in the United States, U.S. federal court cases, and over Stat ...

in '' Buck v. Bell'', which upheld the order.

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (March 8, 1841 – March 6, 1935) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, U.S. Supreme Cou ...

wrote the ruling. He argued the interest of "public welfare" outweighed the interest of individuals in bodily integrity

Bodily integrity is the inviolability of the physical body and emphasizes the importance of personal autonomy, self-ownership, and self-determination of human beings over their own bodies. In the field of human rights, violation of the bodily int ...

:

We have seen more than once that the public welfare may call upon the best citizens for their lives. It would be strange if it could not call upon those who already sap the strength of the State for these lesser sacrifices, often not felt to be such by those concerned, in order to prevent our being swamped with incompetence. It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind. The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes.Holmes concluded his argument with the phrase: "Three generations of imbeciles are enough". Carrie Buck was paroled from the Virginia Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-Minded shortly after she was sterilized. Under the same statute, her mother and three-year-old daughter were also sterilized without their consent. In 1932, her daughter Vivian Buck died of "enteric

colitis

Colitis is swelling or inflammation

Inflammation (from ) is part of the biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants. The five cardinal signs are heat, pain, redness, swelling, and ...

".

When hospitalized for appendicitis

Appendicitis is inflammation of the Appendix (anatomy), appendix. Symptoms commonly include right lower abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fever and anorexia (symptom), decreased appetite. However, approximately 40% of people do not have these t ...

, Doris Buck, Carrie's younger sister, was sterilized without her knowledge or consent. Never told that the operation had been performed, Doris Buck married and with her husband tried to have children. It was not until 1980 that she was told the reason for her inability to get pregnant.

Carrie Buck went on to marry William Eagle. They were married for 25 years until his death. Scholars and reporters who visited Buck in the aftermath of the Supreme Court case reported that she appeared to be a woman of normal intelligence.

The effect of the US Supreme Court's ruling in ''Buck v. Bell'' was to legitimize eugenic sterilization laws in the country. While many states already had sterilization laws on their books, most except for California had used them erratically and infrequently. After ''Buck v. Bell'', dozens of states added new sterilization statutes, or updated their laws. They passed statutes that more closely followed the Virginia statute upheld by the Court.

Supreme Court, repeals and apology: 1967–2002

On June 12, 1967, the US Supreme Court ruled in ''Loving v. Virginia

''Loving v. Virginia'', 388 U.S. 1 (1967), was a landmark civil rights decision of the U.S. Supreme Court that ruled that the laws banning interracial marriage violate the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to ...

'' that the portion of the Racial Integrity Act that criminalized marriages between "whites" and "nonwhites" was found to be contrary to the guarantees of equal protection of citizens under the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment (Amendment XIV) to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments. Considered one of the most consequential amendments, it addresses Citizenship of the United States ...

. In 1975, the Virginia General Assembly repealed the remainder of the Racial Integrity Act. In 1979, it repealed the Sterilization Act. In 2001, the General Assembly overwhelmingly passed a bill (HJ607ER) to express the assembly's profound regret for its role in the eugenics movement. On May 2, 2002, Governor Mark R. Warner issued a statement also expressing "profound regret for the commonwealth's role in the eugenics movement," specifically naming Virginia's 1924 compulsory sterilization

Compulsory sterilization, also known as forced or coerced sterilization, refers to any government-mandated program to involuntarily sterilize a specific group of people. Sterilization removes a person's capacity to reproduce, and is usually do ...

legislation.

See also

*Anti-miscegenation laws in the United States

In the United States, many U.S. states historically had anti-miscegenation laws which prohibited interracial marriage and, in some states, interracial sexual relations. Some of these laws predated the establishment of the United States, and som ...

* '' Buck v. Bell'' (1927)

* Eugenics in the United States

Eugenics, the set of beliefs and practices which aims at improving the Genetics, genetic quality of the human population, played a significant role in the history and culture of the United States from the late 19th century into the mid-20th c ...

* Immorality Act

Immorality Act was the title of two acts of the Parliament of South Africa which prohibited, amongst other things, sexual relations between white people and people of other races. The first Immorality Act, of 1927, prohibited sex outside of marri ...

* Virginia Sterilization Act of 1924

References

External links

"Sterilization Act of 1924" by N. Antonios at the Embryo Project Encyclopedia

Virginia's Indian People

Eugenics archive

"HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION NO. 607, Expressing the General Assembly's regret for Virginia's experience with eugenics", Feb 14, 2001

* Racial Integrity Act of 1924, Original Text

"Harry H. Laughlin"

''Model Eugenical Sterilization Law'', Harvard University

by Joe Heim, ''Washington Post'' March 20, 2017

by Joe Heim, ''Washington Post'', July 1, 2015 {{Authority control 1924 in American law 1924 in Virginia Legal history of Virginia Race legislation in the United States Interracial marriage in the United States Marriage law in the United States Repealed United States legislation African-American segregation in the United States Native American segregation in the United States African-American history of Virginia Anti-black racism in Virginia Anti-Indigenous racism in Virginia Native American history of Virginia Pocahontas Marriage in Virginia White nationalism in Virginia