RAF High Speed Flight on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The RAF High Speed Flight, sometimes known as '' 'The Flight' '', was a small

''Racing Campbells.'' Retrieved: 21 April 2012. The

''RAF History website.'' Retrieved: 12 March 2011.

'' RAF.'' Retrieved: 12 March 2011.

'' RAF.'' Retrieved: 12 March 2011. Rolls-Royce had now developed the supercharged R engine, giving Supermarine's designer R.J. Mitchell far more power for his new S.6 than the naturally aspirated Napier Lion VIIB of the S.5. Gloster's first racing monoplane, the Gloster VI, had stayed with the Lion, but was also now supercharged as the Lion VIID. S.6 ''N247'' came first, piloted by Waghorn, with Atcherley and ''N248'' disqualified for cutting inside a turn. The Gloster VI had been withdrawn before the race, but Stainforth used it to set a new speed record the following day.Vessey 1997 A record which soon fell in turn to one of the S.6s.

Under the rules of the Schneider Trophy, a third win would be an outright win in perpetuity. The official attitude after the 1929 victory was summed up by the Prime Minister

Under the rules of the Schneider Trophy, a third win would be an outright win in perpetuity. The official attitude after the 1929 victory was summed up by the Prime Minister

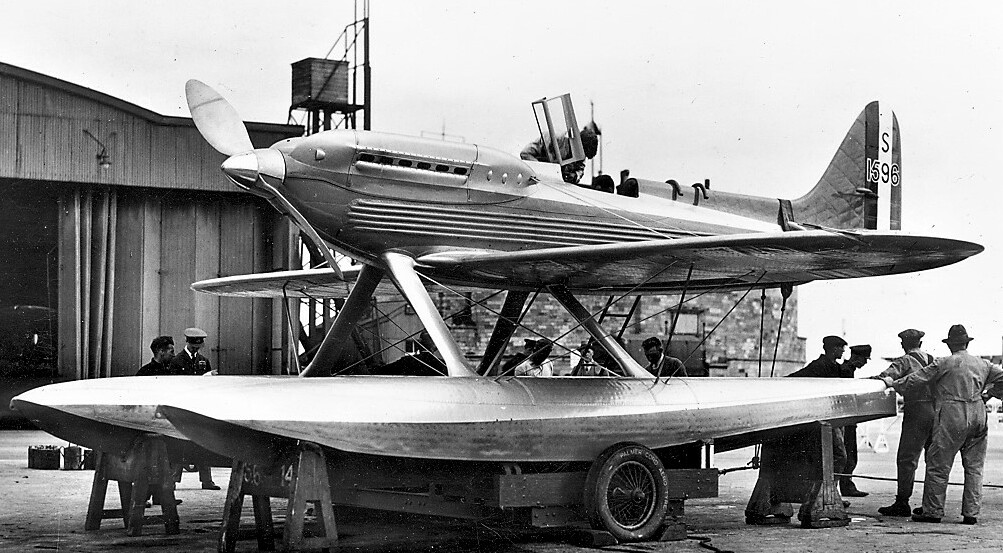

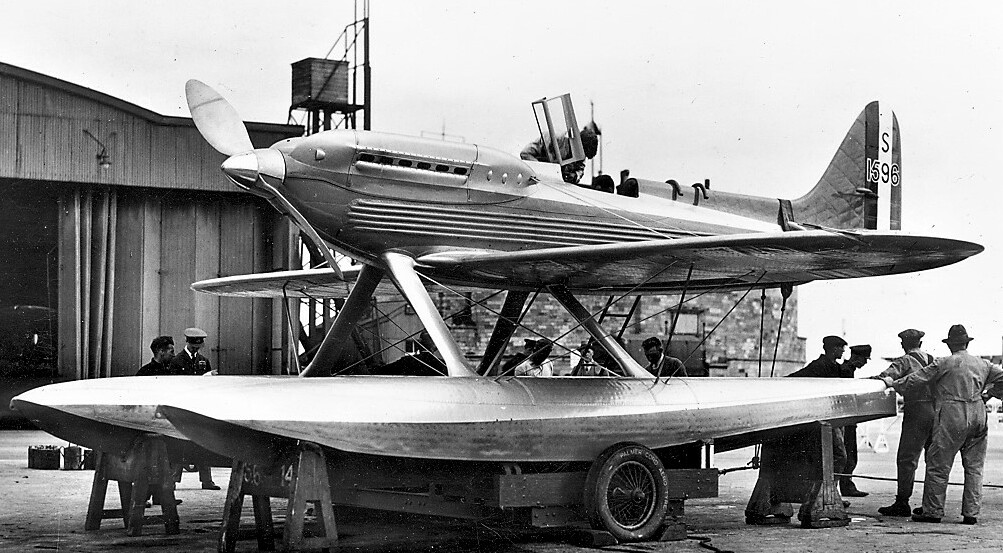

'' RAF''. Retrieved: 12 March 2011. Work then began on the record attempt, which suffered a setback when a minor accident led to ''S1596'' sinking. As a result, both the race and the record were flown by ''S1595'' (now in the The Flight was wound up within weeks of the 1931 victory, it having served its purpose.

The Flight was wound up within weeks of the 1931 victory, it having served its purpose.

In 1946 the High-Speed Flight was re-formed, to attempt the World Air Speed Record.

The Flight was under the command of Group Capt. E. M. Donaldson DSO, AFC and would include such notable pilots as Flt. Lt.

In 1946 the High-Speed Flight was re-formed, to attempt the World Air Speed Record.

The Flight was under the command of Group Capt. E. M. Donaldson DSO, AFC and would include such notable pilots as Flt. Lt. "A tentative record."

''Flight,'' 12 September 1946.

''Racing Ace - The Fights and Flights of 'Kink' Kinkead DSO DSC* DFC*''

Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword, 2011. . * Lewis, Peter. ''British Racing and Record-Breaking Aircraft.'' London: Putnam, 1970. . * Vessey, Alan. ''Napier Powered''(Images of England series). Stroud, UK: Tempus, 1997. .

{{DEFAULTSORT:High Speed Flight Raf Schneider Trophy Royal Air Force independent flights Military units and formations established in 1927

flight

Flight or flying is the motion (physics), motion of an Physical object, object through an atmosphere, or through the vacuum of Outer space, space, without contacting any planetary surface. This can be achieved by generating aerodynamic lift ass ...

of the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

(RAF) formed for the purpose of competing in the Schneider Trophy

The Coupe d'Aviation Maritime Jacques Schneider, also known as the Schneider Trophy, Schneider Prize or (incorrectly) the Schneider Cup is a trophy that was awarded first annually, and later biennially, to the winner of a race for seaplanes and ...

contest for racing

In sports, racing is a competition of speed, in which competitors try to complete a given task in the shortest amount of time. Typically this involves traversing some distance, but it can be any other task involving speed to reach a specific g ...

seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of takeoff, taking off and water landing, landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their tech ...

s during the 1920s. The flight was together only until the trophy was won outright, after which it was disbanded.

Background

In theSchneider Trophy

The Coupe d'Aviation Maritime Jacques Schneider, also known as the Schneider Trophy, Schneider Prize or (incorrectly) the Schneider Cup is a trophy that was awarded first annually, and later biennially, to the winner of a race for seaplanes and ...

race of 1926 both competing countries, Italy and the United States, had used military pilots. There had not been time to arrange a British team to compete. The British defeat of 1925 was held to be the result of technical inferiority and lack of organisation."Supermarine S.5: 1927 Schneider Trophy - Venice, Italy."''Racing Campbells.'' Retrieved: 21 April 2012. The

Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force and civil aviation that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the ...

therefore agreed to support a British team, with pilots drawn from the RAF, and so the High Speed Flight was formed at the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment

The Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment (MAEE) was a British military research and test organisation. It was originally formed as the Marine Aircraft Experimental Station in October 1918 at RAF Isle of Grain, a former Royal Naval Air Serv ...

Felixstowe

Felixstowe ( ) is a port town and civil parish in the East Suffolk District, East Suffolk district, in the county of Suffolk, England. The estimated population in 2017 was 24,521. The Port of Felixstowe is the largest Containerization, containe ...

in preparation for the 1927 race."Schneider Trophy: The 1927 Race."''RAF History website.'' Retrieved: 12 March 2011.

1927

For the 1927 competition, six aircraft, from three manufacturers, were taken toVenice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

: a pair of Supermarine S.5s, three Gloster IV

The Gloster IV was a single-engined biplane racing floatplane designed and produced by the British aviation manufacturer Gloster Aircraft Company.

In response to an order from the British Air Ministry for a high speed floatplane for the 1927 ra ...

s and a single Short Crusader

The Short Crusader also called the Short-Bristow Crusader and Short-Bristol Crusader was a British racing seaplane of the 1920s, built by Short Brothers to compete in the 1927 Schneider Trophy race.

Background

Although inline engines had a cle ...

. The Crusader was slower than the others, and was intended for training, but crashed on 11 September 1927. The cause was later identified as a control rigging error, following re-assembly after the journey from the UK to Venice.Lewis 1970

The Supermarine S.5s came in first and second, with neither the Gloster nor the three Italian aircraft completing the race. As the winning nation, the UK would host the following event. This was the last annual competition. Subsequently, the race was held on a biannual schedule, to allow more time for development between races.

1928

The High Speed Flight was disbanded after the race. TheTreasury

A treasury is either

*A government department related to finance and taxation, a finance ministry; in a business context, corporate treasury.

*A place or location where treasure, such as currency or precious items are kept. These can be ...

agreed to fund the aircraft for the next event but the Air Ministry objected initially to the use of serving pilots. This was sorted out and the High Speed Flight reformed. In March 1928, Samuel Kinkead

Samuel Marcus Kinkead DSO, DSC & Bar, DFC & Bar (25 February 1897 – 12 March 1928) was a South African fighter ace with 33 victories during the First World War. He went on to serve in southern Russia and the Middle East postwar.

Early lif ...

made an attempt on the air speed record using a Supermarine S5. At the approach to the start of the course, however, the aircraft plunged into the water, killing him."Schneider Trophy: The 1929 Race."'' RAF.'' Retrieved: 12 March 2011.

1929

The 1929 Trophy race was to be held atCowes

Cowes () is an England, English port, seaport town and civil parish on the Isle of Wight. Cowes is located on the west bank of the estuary of the River Medina, facing the smaller town of East Cowes on the east bank. The two towns are linked b ...

. With little money forthcoming from the Ministry aircraft and engine development had to be private ventures, with government money only being used to purchase the completed product. The costs of the 1927 and 1929 meetings was stated to be £196,000 and £220,000 respectively."Schneider Trophy: Build-up to the 1931 Race."'' RAF.'' Retrieved: 12 March 2011. Rolls-Royce had now developed the supercharged R engine, giving Supermarine's designer R.J. Mitchell far more power for his new S.6 than the naturally aspirated Napier Lion VIIB of the S.5. Gloster's first racing monoplane, the Gloster VI, had stayed with the Lion, but was also now supercharged as the Lion VIID. S.6 ''N247'' came first, piloted by Waghorn, with Atcherley and ''N248'' disqualified for cutting inside a turn. The Gloster VI had been withdrawn before the race, but Stainforth used it to set a new speed record the following day.Vessey 1997 A record which soon fell in turn to one of the S.6s.

1931

Under the rules of the Schneider Trophy, a third win would be an outright win in perpetuity. The official attitude after the 1929 victory was summed up by the Prime Minister

Under the rules of the Schneider Trophy, a third win would be an outright win in perpetuity. The official attitude after the 1929 victory was summed up by the Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British statesman and politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. The first two of his governments belonged to the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party, where he led ...

, "We are going to do our level best to win again."

However official support was withdrawn because of the need for economies following the Wall Street crash of October 1929. The Cabinet vetoed RAF involvement and Government funding in a sporting event. Trenchard's view that there was no advantage as aircraft development would continue whether or not the UK competed. The public however had other ideas and backed the idea of a national team. A wealthy benefactor, shipping heiress Lady Lucy Houston, offered to pay £100,000 towards its cost. With the financial burden removed, the Government allowed the RAF to compete again.

The delay in funding meant that there was no time to design a new aircraft to compete; instead, the S.6 design was modified: the output of the R engine was increased by 400 hp to 2,300 hp and the airframe was strengthened, producing S.6B. Two new aircraft were built to this specification and the two existing S.6s were upgraded and renamed S.6A.

In the event, the race itself was an anti-climax - no other countries entered a team. All that had to be done was for one of the aircraft from the flight to complete the course. The plan was thus to attempt to beat the previous race time with one of the S6.Bs, then to either go all-out for a new record attempt, or to use the S6.A to secure the Trophy.

The first goal was met according to plan; Flight Lieutenant Boothman, won in S.6B ''S1595'' at 340.08 mph, 12 mph faster than the 1929 time."The Inter-War Years: 1919–1939, Schneider Trophy: Report on the 1931 Race."'' RAF''. Retrieved: 12 March 2011. Work then began on the record attempt, which suffered a setback when a minor accident led to ''S1596'' sinking. As a result, both the race and the record were flown by ''S1595'' (now in the

Science Museum

A science museum is a museum devoted primarily to science. Older science museums tended to concentrate on static displays of objects related to natural history, paleontology, geology, Industry (manufacturing), industry and Outline of industrial ...

, London). The engines were swapped for this attempt though, from the "reliable" race tune to the ultimate performance "sprint" engine and its special fuel. Flight Lieutenant Stainforth then achieved a record of 407.5 mph, the first person to travel faster than 400 mph; "the mark that matters", in the words of Ernest Hives.Donne 1981 In comparison, land speed record

The land speed record (LSR) or absolute land speed record is the highest speed achieved by a person using a vehicle on land. By a 1964 agreement between the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA) and Fédération Internationale de M ...

s didn't achieve this for 15 years, until after the Second World War and John Cobb's Railton Mobil Special Railton may refer to:

* Railton (surname)

* Railton (car), a former marque of British automobiles

* Railton, Kentucky, a place in the US; see List of tornadoes in the Super Outbreak

* Railton, Tasmania, a town in Tasmania, Australia

See also

...

.

Aircraft operated

* 1927 ** Gloster I (training) ** Gloster IVB ** Supermarine S.5 **Short Crusader

The Short Crusader also called the Short-Bristow Crusader and Short-Bristol Crusader was a British racing seaplane of the 1920s, built by Short Brothers to compete in the 1927 Schneider Trophy race.

Background

Although inline engines had a cle ...

* 1929

** Gloster VI

** Supermarine S.6

* 1931

** Supermarine S.6A

** Supermarine S.6B

The Supermarine S.6B is a British racing seaplane developed by R.J. Mitchell for the Supermarine company to take part in the Schneider Trophy competition of 1931. The S.6B marked the culmination of Mitchell's quest to "perfect the design of ...

Post-war reformation

In 1946 the High-Speed Flight was re-formed, to attempt the World Air Speed Record.

The Flight was under the command of Group Capt. E. M. Donaldson DSO, AFC and would include such notable pilots as Flt. Lt.

In 1946 the High-Speed Flight was re-formed, to attempt the World Air Speed Record.

The Flight was under the command of Group Capt. E. M. Donaldson DSO, AFC and would include such notable pilots as Flt. Lt. Neville Duke

Neville Frederick Duke, (11 January 1922 – 7 April 2007) was a British test pilot and fighter ace of the Second World War. He was credited with the destruction of 27 enemy aircraft. After the war, Duke was acknowledged as one of the world's f ...

DSO, DFC, Wing Cdr. Roland Beamont DSO and Squadron Leader

Squadron leader (Sqn Ldr or S/L) is a senior officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many countries that have historical British influence.

Squadron leader is immediatel ...

W.A. Waterton AFC. Two Meteor IVs, ''EE549'' and ''EE550'', were prepared for the speed record attempts. Their modifications were small, the significant ones being a small uprating to the thrust of the Derwent engines, an aluminium cockpit hood as the normal Perspex hood was softening in the heat at over 600 mph.

The course was set out over 3-km between Littlehampton

Littlehampton is a town, seaside resort and civil parish in the Arun District of West Sussex, England. It lies on the English Channel on the eastern bank of the mouth of the River Arun. It is south south-west of London, west of Brighton and ...

and Worthing

Worthing ( ) is a seaside town and borough in West Sussex, England, at the foot of the South Downs, west of Brighton, and east of Chichester. With a population of 113,094 and an area of , the borough is the second largest component of the Br ...

; over five laps Donaldson achieved 616 mph; Waterton 614 mph.''Flight,'' 12 September 1946.

References

;Notes ;Bibliography * Donne, Michael. ''Leader of the Skies (Rolls-Royce 75th Anniversary)''. London: Frederick Muller, 1981. . * Lewis, Julian''Racing Ace - The Fights and Flights of 'Kink' Kinkead DSO DSC* DFC*''

Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword, 2011. . * Lewis, Peter. ''British Racing and Record-Breaking Aircraft.'' London: Putnam, 1970. . * Vessey, Alan. ''Napier Powered''(Images of England series). Stroud, UK: Tempus, 1997. .

External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:High Speed Flight Raf Schneider Trophy Royal Air Force independent flights Military units and formations established in 1927