Quasi War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Quasi-War was an undeclared war from 1798 to 1800 between the

France accepted these acts on the basis of "benevolent neutrality". They interpreted this as allowing French

France accepted these acts on the basis of "benevolent neutrality". They interpreted this as allowing French

Since

Since

From the perspective of the U.S. Navy, the Quasi-War consisted of a series of ship-to-ship actions in U.S. coastal waters and the Caribbean; one of the first was the Capture of ''La Croyable'' on 7 July 1798 by outside Egg Harbor, New Jersey. On 20 November, a pair of French

From the perspective of the U.S. Navy, the Quasi-War consisted of a series of ship-to-ship actions in U.S. coastal waters and the Caribbean; one of the first was the Capture of ''La Croyable'' on 7 July 1798 by outside Egg Harbor, New Jersey. On 20 November, a pair of French

"Selected Bibliography of The Quasi-War with France"

compiled by the

"The XYZ Affair and the Quasi-War with France, 1798–1800"

"U.S. treaties and federal legal documents re 'Quasi-War with France 1791–1800'", compiled by the Lillian Goldman Law Library of Yale Law School

{{DEFAULTSORT:Quasi-War 1798 in France 1798 in the United States 1799 in France 1799 in the United States 1800 in France 1800 in the United States 18th century in France 18th century in the United States Conflicts in 1798 Conflicts in 1799 Conflicts in 1800 Presidency of John Adams United States Marine Corps in the 18th and 19th centuries Wars involving France Wars involving the United States

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

and the French First Republic

In the history of France, the First Republic (), sometimes referred to in historiography as Revolutionary France, and officially the French Republic (), was founded on 21 September 1792 during the French Revolution. The First Republic lasted un ...

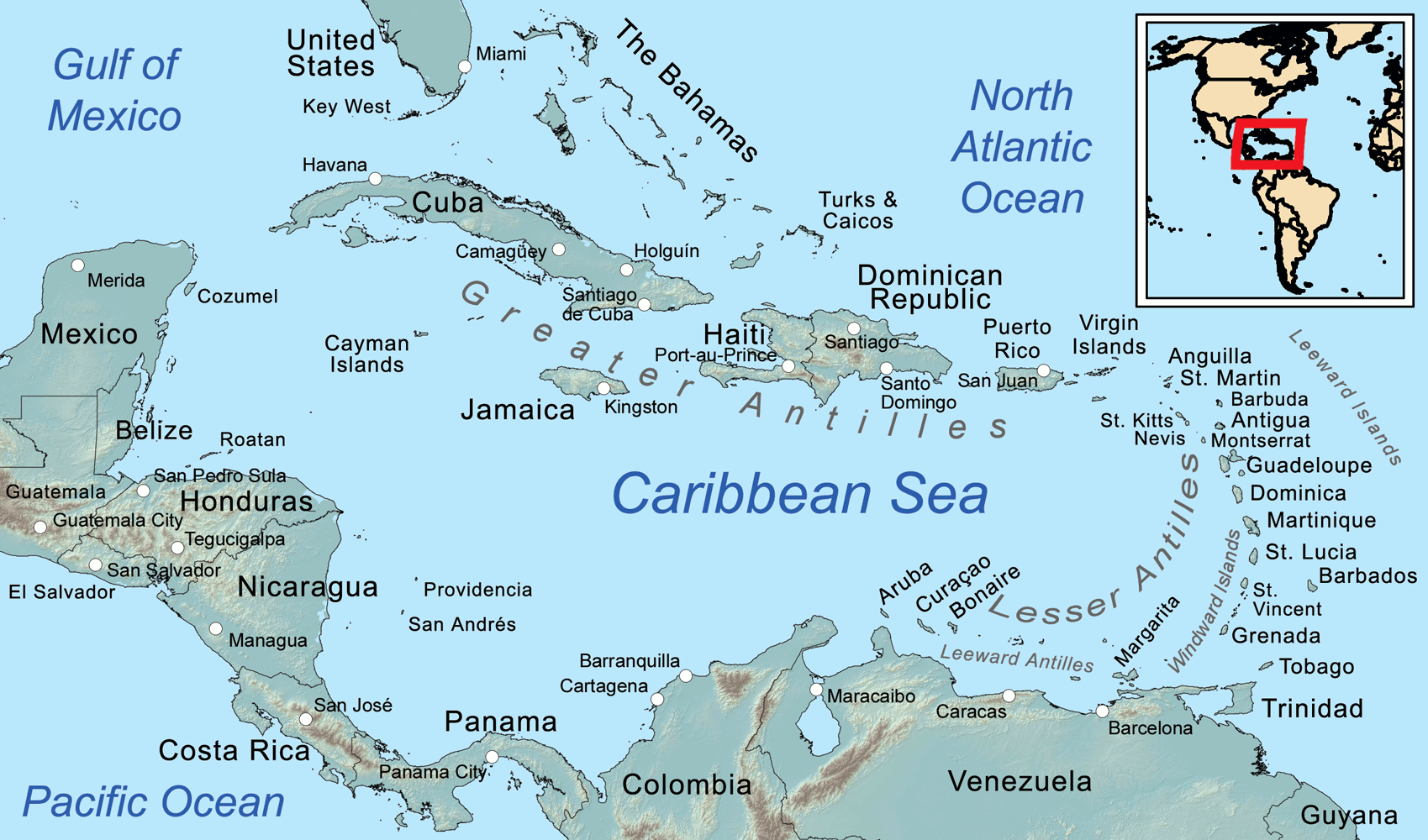

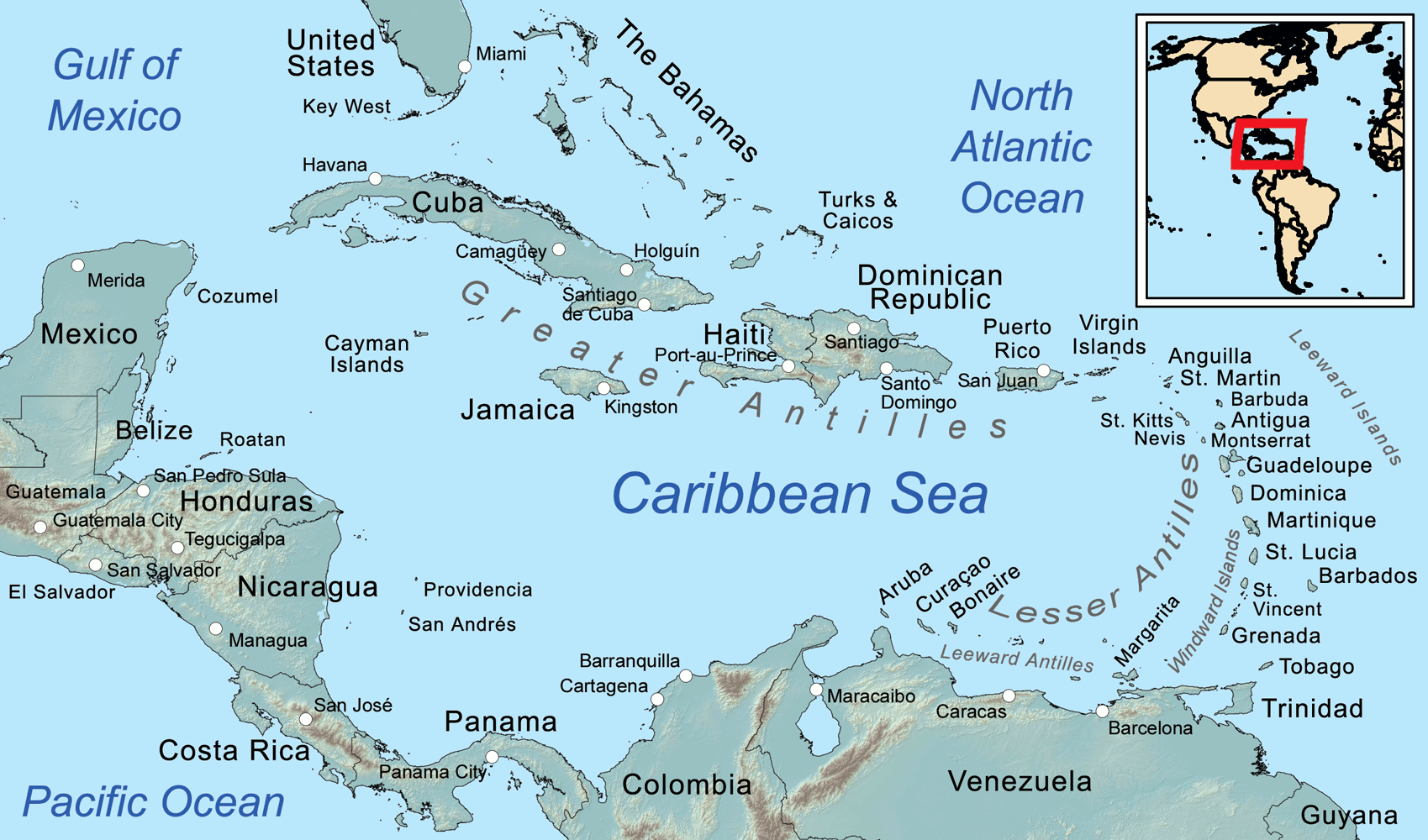

. It was fought almost entirely at sea, primarily in the Caribbean

The Caribbean ( , ; ; ; ) is a region in the middle of the Americas centered around the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, mostly overlapping with the West Indies. Bordered by North America to the north, Central America ...

and off the East Coast of the United States

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, the Atlantic Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard, is the region encompassing the coast, coastline where the Eastern United States meets the Atlantic Ocean; it has always pla ...

, with minor actions in the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

and Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

.

In 1793, Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

unilaterally suspended repayment of French loans from the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

, and in 1794 signed the Jay Treaty

The Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America, commonly known as the Jay Treaty, and also as Jay's Treaty, was a 1794 treaty between the United States and Great Britain that averted ...

with Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

. Then engaged in the 1792 to 1797 War of the First Coalition

The War of the First Coalition () was a set of wars that several European powers fought between 1792 and 1797, initially against the Constitutional Cabinet of Louis XVI, constitutional Kingdom of France and then the French First Republic, Frenc ...

, France retaliated by seizing U.S. ships trading with Great Britain. When diplomacy failed to resolve these issues, in October 1796 French privateer

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign o ...

s began attacking all merchant ships in U.S. waters, regardless of nationality.

Spending cuts following the end of the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

left the U.S. unable to mount an effective response, and within a year over 316 American ships had been captured. In March 1798, Congress reconstituted the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

, and in July authorized the use of force against France. By 1799, losses had been significantly reduced through informal cooperation with the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

, whereby merchant ships from both nations were allowed to join each other's convoys.

The replacement of the French First Republic by the Consulate

A consulate is the office of a consul. A type of mission, it is usually subordinate to the state's main representation in the capital of that foreign country (host state), usually an embassy (or, only between two Commonwealth countries, a ...

in November 1799 led to the Convention of 1800

The Convention of 1800, also known as the Treaty of Mortefontaine (French: ''Traité de Mortefontaine''), was signed on September 30, 1800, by the United States and France. The difference in name was due to congressional sensitivity at entering i ...

, which ended the war. The right of Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

to authorize military action without a formal declaration of war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the public signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national gov ...

was later confirmed by the Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

. This ruling formed the basis of many similar actions since, including U.S. participation in the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

and the Gulf War

, combatant2 =

, commander1 =

, commander2 =

, strength1 = Over 950,000 soldiers3,113 tanks1,800 aircraft2,200 artillery systems

, page = https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GAOREPORTS-PEMD-96- ...

in the 20th century.

Background

Under the 1778 Treaty of Alliance, theUnited States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

had agreed to protect the French West Indies

The French West Indies or French Antilles (, ; ) are the parts of France located in the Antilles islands of the Caribbean:

* The two overseas departments of:

** Guadeloupe, including the islands of Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Les Saintes, Ma ...

in return for French support in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

. Because the treaty had no termination date, France claimed this obligation included supporting them against Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

and the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

during the 1792-1797 War of the First Coalition

The War of the First Coalition () was a set of wars that several European powers fought between 1792 and 1797, initially against the Constitutional Cabinet of Louis XVI, constitutional Kingdom of France and then the French First Republic, Frenc ...

. Despite popular enthusiasm for the French Revolution, there was little support for this in Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

. Neutrality allowed New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

shipowners to earn huge profits evading the British blockade of French ports, while the Southern planter class

The planter class was a Racial hierarchy, racial and socioeconomic class which emerged in the Americas during European colonization of the Americas, European colonization in the early modern period. Members of the class, most of whom were settle ...

feared the example set by France's abolition of slavery in 1794.

In 1793, Congress suspended repayment of French loans incurred during the Revolutionary War, arguing the execution of Louis XVI

Louis XVI, former Bourbon King of France since the Proclamation of the abolition of the monarchy, abolition of the monarchy, was publicly executed on 21 January 1793 during the French Revolution at the ''Place de la Révolution'' in Paris. At Tr ...

and establishment of the French First Republic

In the history of France, the First Republic (), sometimes referred to in historiography as Revolutionary France, and officially the French Republic (), was founded on 21 September 1792 during the French Revolution. The First Republic lasted un ...

rendered existing agreements void. They further argued American military obligations under the Treaty of Alliance applied only to a "defensive conflict" and thus did not apply, since France had declared war on Britain and the Dutch Republic. To ensure the U.S. did not become involved, Congress passed the Neutrality Act of 1794

The Neutrality Act of 1794 was a Law of the United States#Federal law, United States law which made it illegal for a United States citizen to wage war against any country at peace with the United States. The Act declares in part:

If any person ...

, while President George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

issued an executive order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of the ...

forbidding American merchant ship

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are ...

s from arming themselves.

France accepted these acts on the basis of "benevolent neutrality". They interpreted this as allowing French

France accepted these acts on the basis of "benevolent neutrality". They interpreted this as allowing French privateers

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign o ...

to enter U.S. ports, and to sell captured British ships in American prize court

A prize court is a court (or even a single individual, such as an ambassador or consul) authorized to consider whether prizes have been lawfully captured, typically whether a ship has been lawfully captured or seized in time of war or under the te ...

s, but not vice versa. However, the U.S. viewed it as the right to provide the same privileges to both. These differences were further exacerbated in November 1794 when the U.S. and Britain signed the Jay Treaty

The Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America, commonly known as the Jay Treaty, and also as Jay's Treaty, was a 1794 treaty between the United States and Great Britain that averted ...

. By resolving outstanding issues from the American Revolution, it led to a rapid expansion of trade between the two countries. Between 1794 and 1801, American exports to Britain nearly tripled in value, from US$33 million to $94 million.

In late 1796, French privateers began seizing American ships trading with the British, helped by the almost complete lack of a United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

. Their last warship had been sold in 1785, leaving only a small flotilla belonging to the United States Revenue Cutter Service and a few neglected coastal forts. From October 1796 to June 1797, French vessels captured 316 ships, 6% of the entire American merchant fleet, causing losses of $12 to $15 million. On 2 March 1797, the French Directory

The Directory (also called Directorate; ) was the system of government established by the Constitution of the Year III, French Constitution of 1795. It takes its name from the committee of 5 men vested with executive power. The Directory gov ...

issued a decree permitting the seizure of any neutral shipping without a ''role d'equipage'' listing the nationalities of each crewman. Since American ships rarely carried such documents, France had effectively initiated a commerce war.

Diplomatic efforts to resolve the conflict ended in the 1797 dispute known as the XYZ Affair

The XYZ Affair was a political and diplomatic episode in 1797 and 1798, early in the presidency of John Adams, involving a confrontation between the History of the United States (1789–1849), United States and French First Republic, Republican ...

. However, the hostilities created support for establishing a limited naval force, and on 18 June, President John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before Presidency of John Adams, his presidency, he was a leader of ...

appointed Benjamin Stoddert the first Secretary of the Navy

The Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department within the United States Department of Defense. On March 25, 2025, John Phelan was confirm ...

. On 7 July 1798, Congress approved the use of force against French warships in American waters, but wanted to ensure conflict did not escalate beyond these limits. As a result, it was called a "limited" or "Quasi-War", and led to political debate over whether it was constitutional. A series of rulings by the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all Federal tribunals in the United States, U.S. federal court cases, and over Stat ...

confirmed the ability of the U.S. to conduct undeclared wars, or "police action

In security studies and international relations, a police action is a military action undertaken without a formal declaration of war. In the 21st century, the term has been largely supplanted by " counter-insurgency". Since World War II, formal ...

s".

Forces and strategy

ships of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which involved the two column ...

were expensive to build and required highly specialised construction facilities, in 1794 Congress compromised by ordering six large frigates. By 1798, the first three were nearly complete and on 16 July 1798, additional funding was approved for the , , and , plus the frigates and . The provision of naval stores and equipment by the British allowed these to be built relatively quickly, and all saw action during the war.

These vessels were enhanced by so-called "subscription ships", privately funded vessels provided by individual cities. They included five frigates, among them the , commanded by Stephen Decatur

Commodore (United States), Commodore Stephen Decatur Jr. (; January 5, 1779 – March 22, 1820) was a United States Navy officer. He was born on the eastern shore of Maryland in Worcester County, Maryland, Worcester County. His father, Ste ...

, and four merchantmen converted into sloops. Primarily intended to attack foreign shipping, they earned huge profits for their owners; the captured over 80 enemy vessels, including the French corvette .

With most of the French fleet confined to Europe by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

, Secretary Stoddert was able to focus resources on eliminating the few vessels that evaded the blockade and reached the Caribbean. The U.S. also needed convoy protection, and while there was no formal agreement with the British, considerable co-operation took place at a local level. The two navies shared a signal system, and allowed their merchantmen to join each other's convoys, most of which were provided by the British, who had four to five times more escorts available.

This freed the U.S. Navy to concentrate on French privateers, most of which had very shallow draft

Draft, the draft, or draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a v ...

and were armed with a maximum of twenty guns. Operating from French and Spanish bases in the Caribbean, particularly Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe is an Overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands—Basse-Terre Island, Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Guadeloupe, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galant ...

, they made opportunistic attacks on passing ships, before escaping back into port. To counter those tactics, the U.S. used similarly sized vessels from the Revenue Cutter Service, as well as commissioning their own privateers. The first American ship to see action was the , a converted East Indiaman

East Indiamen were merchant ships that operated under charter or licence for European trading companies which traded with the East Indies between the 17th and 19th centuries. The term was commonly used to refer to vessels belonging to the Bri ...

with 26 guns, but most were far smaller.

The revenue cutter

A cutter is any of various types of watercraft. The term can refer to the rig (sail plan) of a sailing vessel (but with regional differences in definition), to a governmental enforcement agency vessel (such as a coast guard or border force cut ...

, commanded by Edward Preble, made two cruises to the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

and captured ten prizes. Preble turned command of ''Pickering'' over to Benjamin Hillar, who captured the much larger and more heavily armed French privateer ''lEgypte Conquise'' after a nine-hour battle. In September 1800, the ''Pickering'' and her entire crew were lost at sea in a storm. Preble next commanded the frigate , which he sailed around Cape Horn

Cape Horn (, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which is Águila Islet), Cape Horn marks the nor ...

into the Pacific to protect U.S. merchantmen in the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies) is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The ''Indies'' broadly referred to various lands in Eastern world, the East or the Eastern Hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainl ...

. He recaptured several U.S. ships that had been seized by French privateers.

The first significant study of the war was written by U.S. naval historian Gardner W. Allen in 1909, and focused exclusively on ship-to-ship actions. This is how the conflict is generally remembered in the U.S., but historian Michael Palmer argues American naval operations cannot be assessed in isolation. When operating in the Caribbean

Significant naval actions

From the perspective of the U.S. Navy, the Quasi-War consisted of a series of ship-to-ship actions in U.S. coastal waters and the Caribbean; one of the first was the Capture of ''La Croyable'' on 7 July 1798 by outside Egg Harbor, New Jersey. On 20 November, a pair of French

From the perspective of the U.S. Navy, the Quasi-War consisted of a series of ship-to-ship actions in U.S. coastal waters and the Caribbean; one of the first was the Capture of ''La Croyable'' on 7 July 1798 by outside Egg Harbor, New Jersey. On 20 November, a pair of French frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and maneuvera ...

s, ''Insurgente'' and ''Volontaire'', captured the schooner , commanded by Lieutenant William Bainbridge

Commodore William Bainbridge (May 7, 1774July 27, 1833) was a United States Navy officer. During his long career in the young American navy he served under six presidents beginning with John Adams and is notable for his many victories at sea. ...

; ''Retaliation'' was recaptured on 28 June 1799.

On 9 February 1799, the frigate captured the French Navy's frigate ''L'Insurgente''. By 1 July, under the command of Decatur, had been refitted and repaired and embarked on her mission to patrol the South Atlantic coast and West Indies in search of French ships which were preying on American merchant vessels.

In the action of 1 January 1800, an American merchant convoy escorted by fought off an attack by 14 French privateer barges in the Gulf of Gonâve. On 1 February, ''Constellation'' severely damaged the French frigate ''La Vengeance'' off the coast of Saint Kitts

Saint Kitts, officially Saint Christopher, is an island in the West Indies. The west side of the island borders the Caribbean Sea, and the eastern coast faces the Atlantic Ocean. Saint Kitts and the neighbouring island of Nevis constitute one ...

, while suffering serious damage itself. Silas Talbot led a naval expedition during the Battle of Puerto Plata Harbor in early May, capturing a Spanish army controlled coastal fort and a French corvette. When French troops occupied Curaçao in July, and bombarded French positions on the island and landed marines to support the local Dutch troops before the French withdrew. On 12 October, the frigate ''Boston'' captured the corvette . Knox, 1939, vol 1

On 25 October, defeated the French brig

A brig is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square rig, square-rigged. Brigs originated in the second half of the 18th century and were a common type of smaller merchant vessel or warship from then until the l ...

''Flambeau'' near Dominica

Dominica, officially the Commonwealth of Dominica, is an island country in the Caribbean. It is part of the Windward Islands chain in the Lesser Antilles archipelago in the Caribbean Sea. The capital, Roseau, is located on the western side of t ...

. ''Enterprise'' also captured eight privateers and freed eleven U.S. merchant ships from captivity, while ''Experiment'' captured the French privateers ''Deux Amis'' and ''Diane'' and liberated numerous American merchant ships. Although U.S. military losses were light, the French had seized over 2,000 American merchant ships by the time the war ended.

Conclusion of hostilities

It has been suggested that since the war was primarily driven by domestic political considerations, neither side was able to identify what a successful resolution entailed. This was enhanced by the tendency of individual commanders to pursue their own objectives, and on the American side, focusing on ship to ship actions rather than overall strategy. In any event, by late 1800 U.S. and British naval operations, combined with a more conciliatory diplomatic stance by the new French government, had significantly reduced privateer activity. TheConvention of 1800

The Convention of 1800, also known as the Treaty of Mortefontaine (French: ''Traité de Mortefontaine''), was signed on September 30, 1800, by the United States and France. The difference in name was due to congressional sensitivity at entering i ...

, signed on 30 September, ended the Quasi-War. It affirmed the rights of Americans as neutrals upon the sea and abrogated the 1778 French alliance, but failed to provide compensation for the alleged $20 million in American economic losses. While the agreement ensured the U.S. remained neutral during the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

, it failed to resolve the underlying tensions with warring European nations, which led to the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

.

See also

* List of wars between democracies * Franco-American relationsFootnotes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * A history of the use of the term "Quasi-War" in the years after 1800. * * * * * Nash, Howard Pervear. ''The Forgotten Wars: The Role of the US Navy in the Quasi War with France and the Barbary Wars 1798–1805'' (AS Barnes, 1968) * * *External links

"Selected Bibliography of The Quasi-War with France"

compiled by the

United States Army Center of Military History

The United States Army Center of Military History (CMH) is a directorate within the United States Army Training and Doctrine Command. The Institute of Heraldry remains within the Office of the Administrative Assistant to the Secretary of the Arm ...

* U.S. Department of Stat"The XYZ Affair and the Quasi-War with France, 1798–1800"

"U.S. treaties and federal legal documents re 'Quasi-War with France 1791–1800'", compiled by the Lillian Goldman Law Library of Yale Law School

{{DEFAULTSORT:Quasi-War 1798 in France 1798 in the United States 1799 in France 1799 in the United States 1800 in France 1800 in the United States 18th century in France 18th century in the United States Conflicts in 1798 Conflicts in 1799 Conflicts in 1800 Presidency of John Adams United States Marine Corps in the 18th and 19th centuries Wars involving France Wars involving the United States