Qantsi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A drinking horn is the

A drinking horn is the

Both in the Greek and the Scythian sphere, vessels of clay or metal shaped like horns were used alongside actual horns from an early time.

A Late Archaic (ca. 480 BC)

Both in the Greek and the Scythian sphere, vessels of clay or metal shaped like horns were used alongside actual horns from an early time.

A Late Archaic (ca. 480 BC)

Drinking horns are attested from Viking Age Scandinavia. In the ''Prose Edda'', Thor drank from a horn that unbeknown to him contained all the seas, and in the process he scared Útgarða-Loki and his kin by managing to drink a conspicuous part of its content. They also feature in ''Beowulf'', and fittings for drinking horns were also found at the Sutton Hoo burial site. Carved horns are mentioned in ''Guðrúnarkviða II'', a poem composed about 1000 AD and preserved in the ''Poetic Edda'':

''Beowulf'' (493ff.) describes the serving of mead in carved horns.

Horn fragments of Viking Age drinking horns are only rarely preserved, showing that both cattle and goat horns were in use. However, the number of decorative metal horn terminals and horn mounts recovered archaeologically show that the drinking horn was much more widespread than the small number of preserved horns would otherwise indicate.

Most Viking Age drinking horns were probably from domestic cattle, holding rather less than half a litre. The significantly larger aurochs horns of the Sutton Hoo burial would have been the exception.

Drinking horns are attested from Viking Age Scandinavia. In the ''Prose Edda'', Thor drank from a horn that unbeknown to him contained all the seas, and in the process he scared Útgarða-Loki and his kin by managing to drink a conspicuous part of its content. They also feature in ''Beowulf'', and fittings for drinking horns were also found at the Sutton Hoo burial site. Carved horns are mentioned in ''Guðrúnarkviða II'', a poem composed about 1000 AD and preserved in the ''Poetic Edda'':

''Beowulf'' (493ff.) describes the serving of mead in carved horns.

Horn fragments of Viking Age drinking horns are only rarely preserved, showing that both cattle and goat horns were in use. However, the number of decorative metal horn terminals and horn mounts recovered archaeologically show that the drinking horn was much more widespread than the small number of preserved horns would otherwise indicate.

Most Viking Age drinking horns were probably from domestic cattle, holding rather less than half a litre. The significantly larger aurochs horns of the Sutton Hoo burial would have been the exception.

The "Oldenburg horn" was made in 1474/75 by German artisans for Christian I of Denmark when he visited Cologne to reconcile Charles the Bold of Burgundy. It is made of silver and gilt, richly ornamented with the coats of arms of Burgundy and Denmark. The horn has its name from being kept in the Schloss Oldenburg, Oldenburg family castle for two centuries before being moved to its present location in Copenhagen. It became associated in legend with count Otto I of Oldenburg, who was supposed to have received it from a fairy woman in 980.

Drinking horns remained in use for ceremonial purposes throughout the Early Modern period. A magnificent drinking horn was made for the showpiece of the Amsterdam Guild of Arquebusiers by Amsterdam jeweller Arent Coster in 1547, now kept in the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum.

In 17th to 18th century Scotland, a distinct type of drinking horn develops.

One aurochs drinking horn still preserved in Dunvegan Castle on the Isle of Skye in Scotland. It was only produced before guests, and the drinker in using it, twisted his arms round its spines, and turning his mouth towards the right shoulder, was expected to drain it off.

German Renaissance and Baroque horns often were lavishly decorated with silverwork.

One such example is depicted in a 1653 painting by Willem Kalf, known as ''Still Life with Drinking Horn''.

The "Oldenburg horn" was made in 1474/75 by German artisans for Christian I of Denmark when he visited Cologne to reconcile Charles the Bold of Burgundy. It is made of silver and gilt, richly ornamented with the coats of arms of Burgundy and Denmark. The horn has its name from being kept in the Schloss Oldenburg, Oldenburg family castle for two centuries before being moved to its present location in Copenhagen. It became associated in legend with count Otto I of Oldenburg, who was supposed to have received it from a fairy woman in 980.

Drinking horns remained in use for ceremonial purposes throughout the Early Modern period. A magnificent drinking horn was made for the showpiece of the Amsterdam Guild of Arquebusiers by Amsterdam jeweller Arent Coster in 1547, now kept in the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum.

In 17th to 18th century Scotland, a distinct type of drinking horn develops.

One aurochs drinking horn still preserved in Dunvegan Castle on the Isle of Skye in Scotland. It was only produced before guests, and the drinker in using it, twisted his arms round its spines, and turning his mouth towards the right shoulder, was expected to drain it off.

German Renaissance and Baroque horns often were lavishly decorated with silverwork.

One such example is depicted in a 1653 painting by Willem Kalf, known as ''Still Life with Drinking Horn''.

Lavishly decorated drinking horns in the Baroque, Baroque style, some imitating cornucopias, some made from ivory, including gold, silver and Vitreous enamel, enamel decorations continued to be produced as luxury items

in 19th to early 20th century Austrian Empire, imperial Austria and German Empire, Germany.

Also in the 19th century, drinking horns inspired by the Romanticism, Romantic Viking revival were made for German Studentenverbindung, student corps for ritual drinking.

In the context of Romanticism, a ceremonial drinking horn with decorations depicting the story of the Mead of Poetry was given to Swedish poet Erik Gustaf Geijer by his students in 1817, now in the Private Collection of Johan Paues, Stockholm.

Lavishly decorated drinking horns in the Baroque, Baroque style, some imitating cornucopias, some made from ivory, including gold, silver and Vitreous enamel, enamel decorations continued to be produced as luxury items

in 19th to early 20th century Austrian Empire, imperial Austria and German Empire, Germany.

Also in the 19th century, drinking horns inspired by the Romanticism, Romantic Viking revival were made for German Studentenverbindung, student corps for ritual drinking.

In the context of Romanticism, a ceremonial drinking horn with decorations depicting the story of the Mead of Poetry was given to Swedish poet Erik Gustaf Geijer by his students in 1817, now in the Private Collection of Johan Paues, Stockholm.

Ram or goat drinking horns, known as ''kantsi (horn), kantsi'', remain an important accessory in the culture of ritual Toast (honor), toasting in

Skythisches Gold in griechischem Stil

Bonn (2013), "Trinkhörner und Rhyta", pp. 25–49.

Viking Answer Lady: Alcoholic Beverages and Drinking Customs of the Viking Age

{{DEFAULTSORT:Drinking Horn Archaeological artefact types Drinkware, Horns Drinking culture, Horns Articles containing video clips Drinking horns, *

A drinking horn is the

A drinking horn is the horn

Horn may refer to:

Common uses

* Horn (acoustic), a tapered sound guide

** Horn antenna

** Horn loudspeaker

** Vehicle horn

** Train horn

*Horn (anatomy), a pointed, bony projection on the head of various animals

* Horn (instrument), a family ...

of a bovid

The Bovidae comprise the family (biology), biological family of cloven-hoofed, ruminant mammals that includes Bos, cattle, bison, Bubalina, buffalo, antelopes (including Caprinae, goat-antelopes), Ovis, sheep and Capra (genus), goats. A member o ...

used as a cup

A cup is an open-top vessel (container) used to hold liquids for drinking, typically with a flattened hemispherical shape, and often with a capacity of about . Cups may be made of pottery (including porcelain), glass, metal, wood, stone, pol ...

. Drinking horns are known from Classical Antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

, especially the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

. They remained in use for ceremonial purposes throughout the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

and the Early Modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

in some parts of Europe, notably in Germanic Europe, and in the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

. Drinking horns remain an important accessory in the culture of ritual toasting in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

in particular, where they are known by the local name of ''kantsi''.

Cups made from glass, metal, pottery, and in the shape of drinking horns are also known since antiquity. The ancient Greek term for a drinking horn was simply ''keras

Keras is an open-source library that provides a Python interface for artificial neural networks. Keras was first independent software, then integrated into the TensorFlow library, and later added support for more. "Keras 3 is a full rewrite o ...

'' (plural ''kerata'', "horn"). To be distinguished from the drinking-horn proper is the ''rhyton

A ''rhyton'' (: ''rhytons'' or, following the Greek plural, ''rhyta'') is a roughly conical container from which fluids were intended to be drunk or to be poured in some ceremony such as libation, or merely at table; in other words, a cup. A ...

'' (plural ''rhyta''), a drinking-vessel made very loosely in the shape of a horn, sometimes with an outlet at the pointed end.

Antiquity

Both in the Greek and the Scythian sphere, vessels of clay or metal shaped like horns were used alongside actual horns from an early time.

A Late Archaic (ca. 480 BC)

Both in the Greek and the Scythian sphere, vessels of clay or metal shaped like horns were used alongside actual horns from an early time.

A Late Archaic (ca. 480 BC) Attic red-figure vase

Red-figure pottery () is a style of ancient Greek pottery in which the background of the pottery is painted black while the figures and details are left in the natural red or orange color of the clay.

It developed in Athens around 520 BC and rem ...

shows Dionysus

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, myth, Dionysus (; ) is the god of wine-making, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, festivity, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, and theatre. He was also known as Bacchus ( or ; ...

and a satyr

In Greek mythology, a satyr (, ), also known as a silenus or ''silenos'' ( ), and sileni (plural), is a male List of nature deities, nature spirit with ears and a tail resembling those of a horse, as well as a permanent, exaggerated erection. ...

each holding a drinking horn.

During Classical Antiquity, the Thracians

The Thracians (; ; ) were an Indo-European languages, Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Southeast Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied the area that today is shared betwee ...

and Scythians

The Scythians ( or ) or Scyths (, but note Scytho- () in composition) and sometimes also referred to as the Pontic Scythians, were an Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Eastern Iranian languages, Eastern Iranian peoples, Iranian Eurasian noma ...

in particular were known for their custom of drinking from horns (archaeologically, the Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

"Thraco-Cimmerian" horizon).

Xenophon's account of his dealings with the Thracian leader Seuthes II, Seuthes suggests that drinking horns were integral part of the drinking ''kata ton Thrakion nomon'' ("after the Thracian fashion").

Diodorus gives an account of a feast prepared by the Getic chief Dromichaites for Lysimachus and selected captives, and the Getians' use of drinking vessels made from horn and wood is explicitly stated.

The Scythian elite also used horn-shaped ''rhyta'' made entirely from precious metal. A notable example is the 5th century BC gold-and-silver ''rhython'' in the shape of a Pegasus which was found in 1982 in Ulyap, Republic of Adygea, Adygea, now at the Museum of Oriental Art in Moscow.

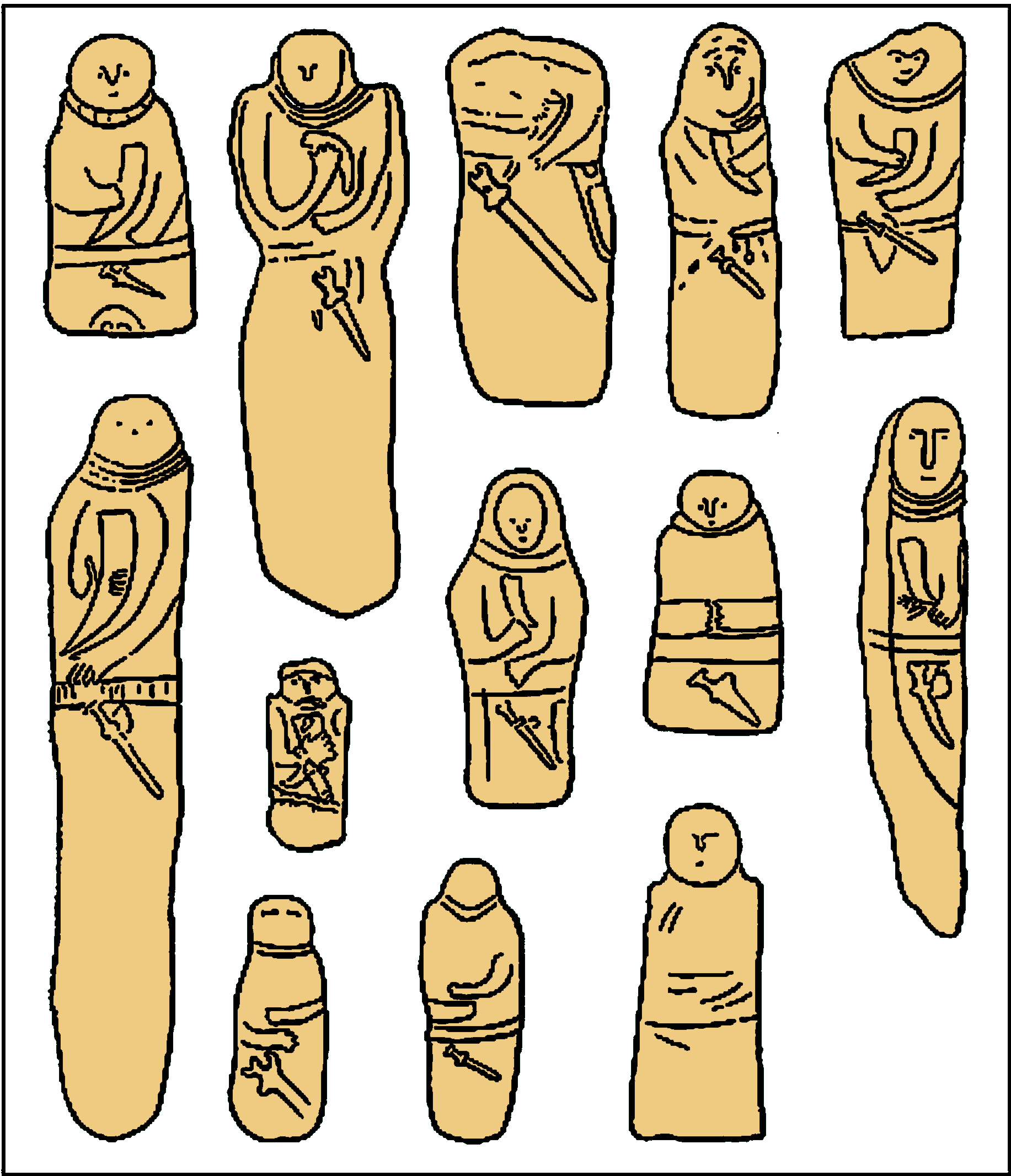

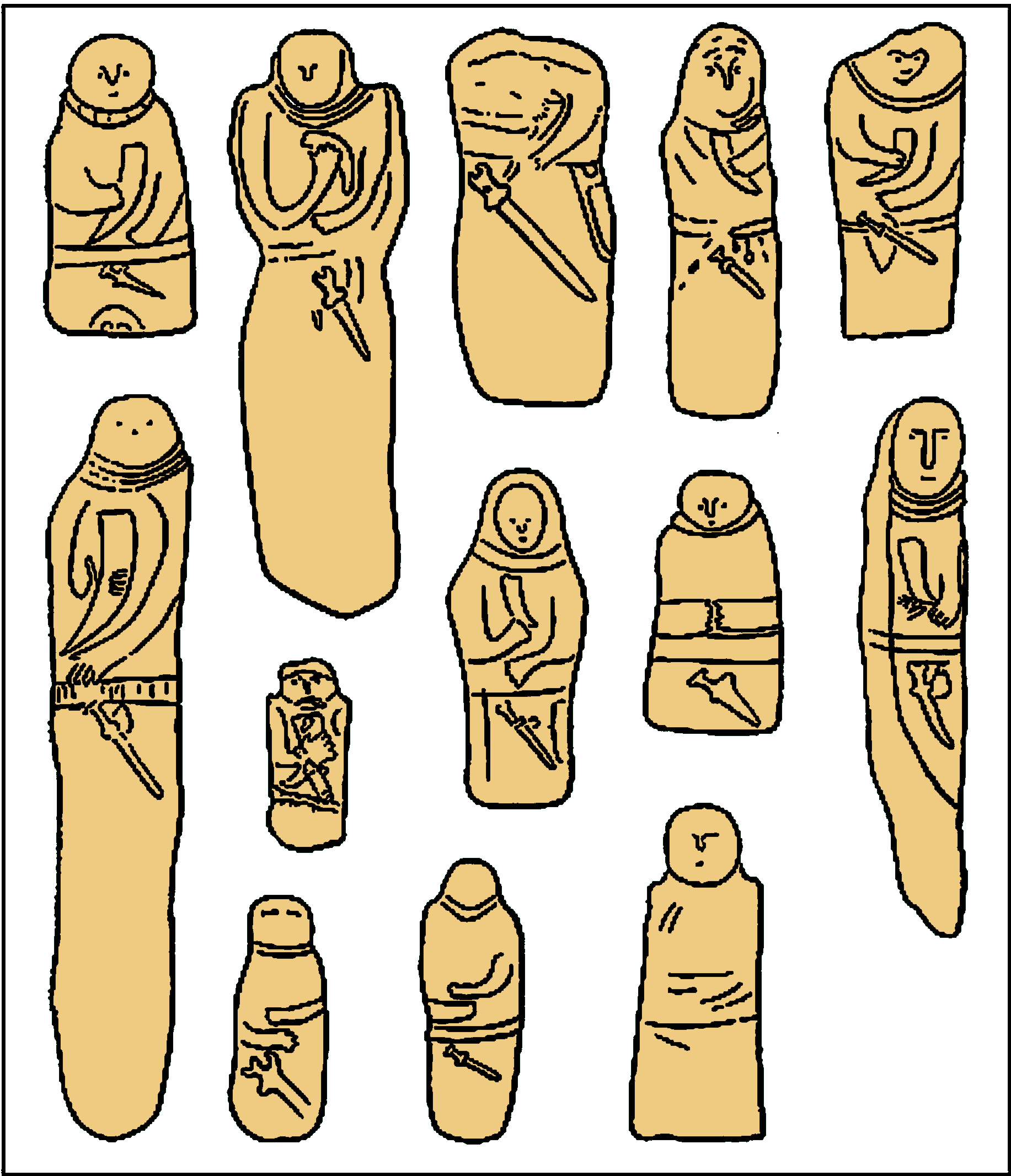

M.I. Maksimova (1956) in an archaeological survey of Scythian drinking horns distinguished two basic types (excluding vessels of clearly foreign origin), a strongly curved type, and a slender type with only slight curvature; the latter type was identified as based on auroch's horns by Maksimova (1956:221). This typology became standard in Soviet-era archaeology.

There are a few artistic representation of Scythians actually drinking from horns from the rim (rather than from the horn's point as with ''rhyta''). The oldest remains of drinking horns or ''rhyta'' known from Scythian burials are dated to the 7th century BC, reflecting Scythian contact with oriental culture during their raids of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Assyrian Empire at that time. After these early specimens, there is a gap with only sparse evidence of Scythian drinking horns during the 6th century.

Drinking horns re-appear in the context of Pontic burials in the 5th century BC: these are the specimens classified as Scythian drinking horns by Maksimova (1956). The 5th-century BC practice of depositing drinking horns with precious metal fittings as grave goods for deceased warriors appears to originate in the Kuban region. In the 4th century BC, the practice spreads throughout the Pontic Steppe. Rhyta, mostly of Achaemenid or Thracian import, continue to be found in Scythian burials, but they are now clearly outnumbered by Scythian drinking horns proper.

Around the midpoint of the 4th century BC, a new type of solid silver drinking horn with strong curvature appears. While the slightly curving horn type is found throughout the Pontic Steppe, specimens of the new type have not been found in the Kuban area. The custom of depositing drinking horns as grave goods begins to subside towards the end of the 4th century BC.

The depiction of drinking horns on kurgan stelae appears to follow a slightly different chronology, with the earliest examples dated to the 6th century BC, and a steep increase in frequency during the 5th, but becoming rare by the 4th century (when actual deposits of drinking horns become most frequent). In the Crimean peninsula, such depictions appear somewhat later, from the 5th century BC, but then more frequently than elsewhere.

Scythian drinking horns have been found almost exclusively in warrior burials. This has been taken as strongly suggesting an association of the drinking horn with the

Scythian cult of kingship and warrior ethos. In the influential interpretation due to Michael Rostovtzeff, M. I. Rostovtzeff (1913), the Scythian ruler received the drinking horn from a deity as a symbol of his investiture. This interpretation is based on a number of depictions of a Scythian warrior drinking from a horn standing or kneeling next to a seated woman. Rolle (1980) interpreted the woman not as a goddess but as a high-ranking Scythian woman performing a ritual office.

Krausse (1996) interpreted the same scenes as depicting a marriage ceremony, with

the man drinking from the horn as part of an oath ritual comparable to the scenes of Scythian warriors jointly drinking from a horn in an oath of blood brotherhood.

The Scythian drinking horns are clearly associated with the consumption of History of wine#Antiquity, wine.

The drinking horn reached Central Europe with the Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

, in the wider context of "Thraco-Cimmerian" cultural transmission. A number of early Celts, Celtic (Hallstatt culture) specimens are known, notably the remains of a huge gold-banded horn found at the Hochdorf Chieftain's Grave, Hochdorf burial.

Krauße (1996) examines the spread of the "fashion" of drinking horns (''Trinkhornmode'') in prehistoric Europe, assuming it reached the eastern prehistoric Balkans, Balkans from Scythia around 500 BC. It is more difficult to assess the role of plain animal horns as everyday drinking vessels, because these decay without a trace, while the metal fittings of the ceremonial drinking horns of the elite are preserved archaeologically.

Julius Caesar has a description of Gauls, Gaulish use of aurochs drinking horns (''cornu urii'') in ''Commentarii de Bello Gallico'' 6.28:

:''„Amplitudo cornuum et figura et species multum a nostrorum boum cornibus differt. Haec studiose conquisita ab labris argento circumcludunt atque in amplissimis epulis pro poculis utuntur.“''

:"The [Gaulish] horns in size, shape, and kind are very different from those of our cattle. They are much sought-after, their rim fitted with silver, and they are used at great feasts as drinking vessels."

Migration period

The Germanic peoples of the Migration period imitated glass drinking horns from Roman models. One fine 5th century Merovingian example found at Bingerbrück, Rhineland-Palatinate made from olive green glass is kept at the British Museum. Some of the skills of the Roman glass-makers survived in Lombards, Lombardic Italy, exemplified by a blue glass drinking-horn from Sutri, also in the British Museum. The two Golden Horns of Gallehus, Gallehus Horns (early 5th century), made from some 3 kg of gold and electrum each, are usually interpreted as drinking horns, although some scholars point out that it cannot be ruled out that they may have been intended as blowing horns. After the discovery of the first of these horns in 1639, Christian IV of Denmark by 1641 did refurbish it into a usable drinking horn, adding a rim, extending its narrow end and closing it up with a screw-on pommel. These horns are the most spectacular known specimens of Germanic Iron Age drinking horns, but they were lost in 1802 and are now only known from 17th to 18th century drawings. Some notable examples of drinking horns of Dark Ages Europe were made of the horns of the aurochs, the wild ancestor of domestic cattle which became extinct in the 17th century. These horns were carefully dressed up and their edges lipped all round with silver. The remains of a notable example were recovered from the Sutton Hoo burial. The British Museum also has a fine pair of 6th century Anglo-Saxons, Anglo-Saxon drinking horns, made from Aurochs horns with silver-gilt mounts, recovered from the Taplow Barrow, princely burial at Taplow, Buckinghamshire. Numerous pieces of elaborate drinking equipment have been found in female graves in all pagan Germanic societies, beginning in the Germanic Roman Iron Age and spanning a full millennium, into the Viking Age.Viking Age

Drinking horns are attested from Viking Age Scandinavia. In the ''Prose Edda'', Thor drank from a horn that unbeknown to him contained all the seas, and in the process he scared Útgarða-Loki and his kin by managing to drink a conspicuous part of its content. They also feature in ''Beowulf'', and fittings for drinking horns were also found at the Sutton Hoo burial site. Carved horns are mentioned in ''Guðrúnarkviða II'', a poem composed about 1000 AD and preserved in the ''Poetic Edda'':

''Beowulf'' (493ff.) describes the serving of mead in carved horns.

Horn fragments of Viking Age drinking horns are only rarely preserved, showing that both cattle and goat horns were in use. However, the number of decorative metal horn terminals and horn mounts recovered archaeologically show that the drinking horn was much more widespread than the small number of preserved horns would otherwise indicate.

Most Viking Age drinking horns were probably from domestic cattle, holding rather less than half a litre. The significantly larger aurochs horns of the Sutton Hoo burial would have been the exception.

Drinking horns are attested from Viking Age Scandinavia. In the ''Prose Edda'', Thor drank from a horn that unbeknown to him contained all the seas, and in the process he scared Útgarða-Loki and his kin by managing to drink a conspicuous part of its content. They also feature in ''Beowulf'', and fittings for drinking horns were also found at the Sutton Hoo burial site. Carved horns are mentioned in ''Guðrúnarkviða II'', a poem composed about 1000 AD and preserved in the ''Poetic Edda'':

''Beowulf'' (493ff.) describes the serving of mead in carved horns.

Horn fragments of Viking Age drinking horns are only rarely preserved, showing that both cattle and goat horns were in use. However, the number of decorative metal horn terminals and horn mounts recovered archaeologically show that the drinking horn was much more widespread than the small number of preserved horns would otherwise indicate.

Most Viking Age drinking horns were probably from domestic cattle, holding rather less than half a litre. The significantly larger aurochs horns of the Sutton Hoo burial would have been the exception.

Medieval to Early Modern period

Drinking horns were the ceremonial drinking vessel for those of high status all through the medieval period References to drinking horns in medieval literature include the Arthurian tale of Caradoc and the Middle English romance of King Horn. The Bayeux Tapestry (1070s) shows a scene of feasting before Harold Godwinson embarks for Normandy. Five figures are depicted as sitting at a table in the upper story of a building, three of them holding drinking horns. Most Norwegian drinking horns preserved from the Middle Ages have ornamented metal mountings, while the horns themselves are smooth and unornamented. Carvings in the horns themselves are also known, but these appear relatively late, and are of a comparative simplicity that classifies them as folk art. Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, Corpus Christi College of Cambridge University has a large aurochs drinking horn, allegedly predating the College's foundation in the 14th century, which is still drunk from at College feasts.Modern period

Lavishly decorated drinking horns in the Baroque, Baroque style, some imitating cornucopias, some made from ivory, including gold, silver and Vitreous enamel, enamel decorations continued to be produced as luxury items

in 19th to early 20th century Austrian Empire, imperial Austria and German Empire, Germany.

Also in the 19th century, drinking horns inspired by the Romanticism, Romantic Viking revival were made for German Studentenverbindung, student corps for ritual drinking.

In the context of Romanticism, a ceremonial drinking horn with decorations depicting the story of the Mead of Poetry was given to Swedish poet Erik Gustaf Geijer by his students in 1817, now in the Private Collection of Johan Paues, Stockholm.

Lavishly decorated drinking horns in the Baroque, Baroque style, some imitating cornucopias, some made from ivory, including gold, silver and Vitreous enamel, enamel decorations continued to be produced as luxury items

in 19th to early 20th century Austrian Empire, imperial Austria and German Empire, Germany.

Also in the 19th century, drinking horns inspired by the Romanticism, Romantic Viking revival were made for German Studentenverbindung, student corps for ritual drinking.

In the context of Romanticism, a ceremonial drinking horn with decorations depicting the story of the Mead of Poetry was given to Swedish poet Erik Gustaf Geijer by his students in 1817, now in the Private Collection of Johan Paues, Stockholm.Ram or goat drinking horns, known as ''kantsi (horn), kantsi'', remain an important accessory in the culture of ritual Toast (honor), toasting in

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

.

During a formal dinner (''supra'') Georgians propose a toast, led by a toastmaster (''tamada'') who sets the topic of each round of toasting. Toasts are made with either wine or brandy; toasting with beer is considered an insult.

In Swiss culture, a large drinking horn together with a wreath of oak leaves is the traditional prize for the winning team of a Hornussen tournament.

Modern-day Asatru adherents use drinking horns for Blóts (sacrificial rituals) and sumbels (feasts).

See also

* Blowing horn * Fairy cup legend * Cornucopia * Powder horn * Qanci * Rhyton * Sumbel *Notes

References

* Enright, Michael J. ''Lady With a Mead Cup: Ritual Prophecy and Lordship in the European Warband from La Tène to the Viking Age''. Dublin: Four Courts Press. 1996. * V.I. Evison, ''Germanic glass drinking horns'', Journal of Glass Studies-1, 17 (1975) * Dirk Krausse, ''Hochdorf, Bd.3, Das Trinkservice und Speiseservice aus dem späthallstattzeitlichen Fürstengrab von Eberdingen-Hochdorf'', Theiss (1996), . * Hagen, Ann.'' A Second Handbook of Anglo-Saxon Food and Drink: Production and Distribution''. Hockwold cum Wilton, Norfolk, UK: Anglo-Saxon Books. 1995. * Magerøy, Ellen Marie. "Carving: Bone, Horn, and Walrus Tusk" in ''Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopedia''. Phillip Pulsiano et al., eds. Garland Reference Library of the Humanities 934. New York: Garland. 1993. pp. 66–71. * Wieland, AnjaSkythisches Gold in griechischem Stil

Bonn (2013), "Trinkhörner und Rhyta", pp. 25–49.

External links

Viking Answer Lady: Alcoholic Beverages and Drinking Customs of the Viking Age

{{DEFAULTSORT:Drinking Horn Archaeological artefact types Drinkware, Horns Drinking culture, Horns Articles containing video clips Drinking horns, *