Pseudoscorpion Genera on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pseudoscorpions, also known as false scorpions or book scorpions, are small, scorpion-like

Entomological Notes: Pseudoscorpion Fact Sheet

/ref> The largest known species is ''

The male produces a

The male produces a

The oldest known fossil pseudoscorpion, '' Dracochela deprehendor'' is known from

The oldest known fossil pseudoscorpion, '' Dracochela deprehendor'' is known from

Pseudoscorpions of the World

* Joseph C. Chamberlin (1931): ''The Arachnid Order Chelonethida''. Stanford University Publications in Biological Science. 7(1): 1–284. * Clarence Clayton Hoff (1958): List of the Pseudoscorpions of North America North of Mexico. ''American Museum Novitates''. 1875

PDF

* Max Beier (1967): Pseudoscorpione vom kontinentalen Südost-Asien. ''Pacific Insects'' 9(2): 341–369

PDF

* * P. D. Gabbutt (1970): Validity of Life History Analyses of Pseudoscorpions. ''Journal of Natural History'' 4: 1–15. * W. B. Muchmore (1982): ''Pseudoscorpionida''. In "Synopsis and Classification of Living Organisms." Vol. 2. Parker, S.P. * J. A. Coddington, S. F. Larcher & J. C. Cokendolpher (1990): ''The Systematic Status of Arachnida, Exclusive of Acari, in North America North of Mexico.'' In "Systematics of the North American Insects and Arachnids: Status and Needs." National Biological Survey 3. ''Virginia Agricultural Experiment Station, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University''. * Mark S. Harvey (1991): ''Catalogue of the Pseudoscorpionida.'' (edited by V . Mahnert). Manchester University Press, Manchester.

Video of Pseudoscorpions in Ireland

{{Authority control Extant Devonian first appearances

arachnid

Arachnids are arthropods in the Class (biology), class Arachnida () of the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, opiliones, harvestmen, Solifugae, camel spiders, Amblypygi, wh ...

s belonging to the order Pseudoscorpiones, also known as Pseudoscorpionida or Chelonethida.

Pseudoscorpions are generally beneficial to humans because they prey on clothes moth

Clothes moth or clothing moth is the common name for several species of moth considered to be pests, whose larvae eat animal fibres (hairs), including clothing and other fabrics.

These include:

* ''Tineola bisselliella'', the common clothes mot ...

larvae, carpet beetle larvae, booklice, ant

Ants are Eusociality, eusocial insects of the Family (biology), family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the Taxonomy (biology), order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from Vespoidea, vespoid wasp ancestors in the Cre ...

s, mite

Mites are small arachnids (eight-legged arthropods) of two large orders, the Acariformes and the Parasitiformes, which were historically grouped together in the subclass Acari. However, most recent genetic analyses do not recover the two as eac ...

s, and small flies

Flies are insects of the Order (biology), order Diptera, the name being derived from the Ancient Greek, Greek δι- ''di-'' "two", and πτερόν ''pteron'' "wing". Insects of this order use only a single pair of wings to fly, the hindwin ...

. They are common in many environments, but they are rarely noticed due to their small size. When people see pseudoscorpions, especially indoors, they often mistake them for tick

Ticks are parasitic arachnids of the order Ixodida. They are part of the mite superorder Parasitiformes. Adult ticks are approximately 3 to 5 mm in length depending on age, sex, and species, but can become larger when engorged. Ticks a ...

s or small spider

Spiders (order (biology), order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight limbs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude spider silk, silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and ran ...

s. Pseudoscorpions often carry out phoresis

Phoresis or phoresy is a temporary commensalistic relationship when an organism (a phoront or phoretic) attaches itself to a host organism solely for travel. It has been seen in ticks and mites since the 18th century, and in fossils 320 ...

, a form of commensalism

Commensalism is a long-term biological interaction (symbiosis) in which members of one species gain benefits while those of the other species neither benefit nor are harmed. This is in contrast with mutualism, in which both organisms benefit fr ...

in which one organism uses another for the purpose of transport.

Characteristics

Pseudoscorpions belong to the classArachnida

Arachnids are arthropods in the class Arachnida () of the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, harvestmen, camel spiders, whip spiders and vinegaroons.

Adult arachnids ...

. They are small arachnids with a flat, pear-shaped body, and pincer-like pedipalp

Pedipalps (commonly shortened to palps or palpi) are the secondary pair of forward appendages among Chelicerata, chelicerates – a group of arthropods including spiders, scorpions, horseshoe crabs, and sea spiders. The pedipalps are lateral to ...

s that resemble those of scorpion

Scorpions are predatory arachnids of the Order (biology), order Scorpiones. They have eight legs and are easily recognized by a pair of Chela (organ), grasping pincers and a narrow, segmented tail, often carried in a characteristic forward cur ...

s. They usually range from in length.Pennsylvania State University

The Pennsylvania State University (Penn State or PSU) is a Public university, public Commonwealth System of Higher Education, state-related Land-grant university, land-grant research university with campuses and facilities throughout Pennsyl ...

, DepartmentEntomological Notes: Pseudoscorpion Fact Sheet

/ref> The largest known species is ''

Garypus titanius

''Garypus titanius'', the giant pseudoscorpion, is the largest species of pseudoscorpion—small, scorpion-looking creatures—in the world. Critically endangered, it is restricted to Boatswain Bird Island, a small rocky island off Ascension Is ...

'' of Ascension Island

Ascension Island is an isolated volcanic island, 7°56′ south of the Equator in the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic Ocean. It is about from the coast of Africa and from the coast of South America. It is governed as part of the British Overs ...

at up to . Range is generally smaller at an average of .

A pseudoscorpion has eight legs with five to seven segments each; the number of fused segments is used to distinguish families and genera. They have two very long pedipalp

Pedipalps (commonly shortened to palps or palpi) are the secondary pair of forward appendages among Chelicerata, chelicerates – a group of arthropods including spiders, scorpions, horseshoe crabs, and sea spiders. The pedipalps are lateral to ...

s with palpal chelae

A chela ()also called a claw, nipper, or pinceris a pincer-shaped organ at the end of certain limbs of some arthropods. The name comes from Ancient Greek , through Neo-Latin '. The plural form is chelae. Legs bearing a chela are called chelipeds ...

(pincers), which strongly resemble the pincers found on a scorpion.

The pedipalps generally consist of an immobile "hand" and mobile "finger", the latter controlled by an adductor muscle. Members of the clade Iocheirata, which contains the majority of pseudoscorpions, are venom

Venom or zootoxin is a type of toxin produced by an animal that is actively delivered through a wound by means of a bite, sting, or similar action. The toxin is delivered through a specially evolved ''venom apparatus'', such as fangs or a sti ...

ous, with a venom gland and duct usually located in the mobile finger; the venom is used to immobilize the pseudoscorpion's prey. During digestion, pseudoscorpions exude a mildly corrosive fluid over the prey, then ingest the liquefied remains.

The abdomen, referred to as the opisthosoma

The opisthosoma is the posterior part of the body in some arthropods, behind the prosoma ( cephalothorax). It is a distinctive feature of the subphylum Chelicerata (arachnids, horseshoe crabs and others). Although it is similar in most respects ...

, is made up of twelve segments, each protected by sclerotized

Sclerosis (also sclerosus in the Latin names of a few disorders) is a hardening of tissue and other anatomical features. It may refer to:

* Sclerosis (medicine), a hardening of tissue

* in zoology, a process which forms sclerites, a hardened exo ...

plates (called tergite

A ''tergum'' (Latin for "the back"; : ''terga'', associated adjective tergal) is the Anatomical terms of location#Dorsal and ventral, dorsal ('upper') portion of an arthropod segment other than the head. The Anatomical terms of location#Anterior ...

s above and sternite

The sternum (: sterna) is the ventral portion of a segment of an arthropod thorax or abdomen.

In insects, the sterna are usually single, large sclerites, and external. However, they can sometimes be divided in two or more, in which case the su ...

s below). The abdomen is short and rounded at the rear, rather than extending into a segmented tail and stinger like true scorpions. The color of the body can be yellowish-tan to dark-brown, with the paired claws often a contrasting color. They may have two, four or no eyes.

Pseudoscorpions spin silk

Silk is a natural fiber, natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be weaving, woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is most commonly produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoon (silk), c ...

from a gland in their jaws to make disk-shaped cocoons for mating, molting, or waiting out cold weather, but they do not have book lungs

A book lung is a type of respiration organ used for atmospheric gas-exchange that is present in many arachnids, such as scorpions and spiders. Each of these organs is located inside an open, ventral-abdominal, air-filled cavity (atrium) and co ...

like true scorpions and the Tetrapulmonata

Tetrapulmonata is a Taxonomic rank, non-ranked Order (biology), supra-ordinal clade of arachnids. It is composed of the Extant taxon, extant orders Uropygi (whip scorpions), Schizomida (short-tailed whip scorpions), Amblypygi (tail-less whip scor ...

. Instead, they breathe exclusively through trachea

The trachea (: tracheae or tracheas), also known as the windpipe, is a cartilaginous tube that connects the larynx to the bronchi of the lungs, allowing the passage of air, and so is present in almost all animals' lungs. The trachea extends from ...

e, which open laterally through two pairs of spiracles on the posterior margins of the sternites of abdominal segments 3 and 4.

Behavior

The male produces a

The male produces a spermatophore

A spermatophore, from Ancient Greek σπέρμα (''spérma''), meaning "seed", and -φόρος (''-phóros''), meaning "bearing", or sperm ampulla is a capsule or mass containing spermatozoa created by males of various animal species, especiall ...

which is attached to the substrate and is picked up by the female. Members of the Cheliferoidea (Atemnidae, Cheliferidae, Chernetidae and Withiidae) have an elaborate mating dance, which ends with the male navigating the female over his spermatophore. In Cheliferidae, the male also uses his forelegs to open the female genital operculum, and after she has mounted the packet of sperm, assisting the spermatophore's entry by pushing it into her genital opening. Females in species that possess a spermatheca

The spermatheca (pronounced : spermathecae ), also called ''receptaculum seminis'' (: ''receptacula seminis''), is an organ of the female reproductive tract in insects, e.g. ants, bees, some molluscs, Oligochaeta worms and certain other in ...

(sperm storing organ) can store the sperm for a longer period of time before fertilizing the eggs, but species without the organ fertilize the eggs shortly after mating. The female carries the fertilized eggs in a brood pouch attached to her abdomen

The abdomen (colloquially called the gut, belly, tummy, midriff, tucky, or stomach) is the front part of the torso between the thorax (chest) and pelvis in humans and in other vertebrates. The area occupied by the abdomen is called the abdominal ...

.

Between 2 and 50 young are hatched in a single brood

Brood may refer to:

Nature

* Brood, a collective term for offspring

* Brooding, the incubation of bird eggs by their parents

* Bee brood, the young of a beehive

* Individual broods of North American periodical cicadas:

** Brood X, the largest br ...

, with more than one brood per year possible. The young go through three molts called the protonymph, deutonymph and tritonymph. The developing embryo and the protonymph, which remain attached to the mother, is nourished by a ‘milk’ produced by her ovary. Many species molt in a small, silken igloo that protects them from enemies during this vulnerable period.

After reaching adulthood they no longer molt, and will live for 2–3 years. They are active in the warm months of the year, overwintering in silken cocoons when the weather grows cold. Smaller species live in debris and humus

In classical soil science, humus is the dark organic matter in soil that is formed by the decomposition of plant and animal matter. It is a kind of soil organic matter. It is rich in nutrients and retains moisture in the soil. Humus is the Lati ...

. Some species are arboreal

Arboreal locomotion is the locomotion of animals in trees. In habitats in which trees are present, animals have evolved to move in them. Some animals may scale trees only occasionally (scansorial), but others are exclusively arboreal. The hab ...

, while others are phagophiles, eating parasites in an example of cleaning symbiosis

Cleaning is the process of removing unwanted substances, such as dirt, infectious agents, and other impurities, from an object or environment. Cleaning is often performed for beauty, aesthetic, hygiene, hygienic, Function (engineering), function ...

. Some species are phoretic

Phoresis or phoresy is a temporary Commensalism, commensalistic relationship when an organism (a phoront or phoretic) attaches itself to a host organism solely for travel. It has been seen in tick, ticks and mite, mites since the 18th century, ...

, others may sometimes be found feeding on mites under the wing covers of certain beetles.

Distribution

More than 3,300 species of pseudoscorpions are recorded in more than 430 genera, with more being discovered on a regular basis. They range worldwide, even in temperate to cold regions such asNorthern Ontario

Northern Ontario is a primary geographic and quasi-administrative region of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Ontario, the other primary region being Southern Ontario. Most of the core geographic region is located on p ...

and above the timberline in Wyoming's Rocky Mountains in the United States and the Jenolan Caves

The Jenolan Caves (Tharawal language, Tharawal: ''Binoomea'', ''Bindo'', ''Binda'') are limestone cave, limestone caves located within the Jenolan Karst Conservation Reserve in the Central Tablelands region, west of the Blue Mountains (New Sout ...

of Australia, but have their most dense and diverse populations in the tropics

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the equator, where the sun may shine directly overhead. This contrasts with the temperate or polar regions of Earth, where the Sun can never be directly overhead. This is because of Earth's ax ...

and subtropics, where they spread even to island territories such as the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; ) or Canaries are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean and the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, Autonomous Community of Spain. They are located in the northwest of Africa, with the closest point to the cont ...

, where around 25 endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

species have been found. There are also two endemic species on the Maltese Islands

The geography of Malta is dominated by water. Malta is an archipelago of coralline limestone, located in Europe, in the Mediterranean Sea, 81 kilometres south of Sicily, Italy,From Żebbuġ in Malta, coordinates: 36°04'48.2"N 14°15'06.7"E to Ca ...

. Species have been found under tree bark, in leaf and pine litter

Litter consists of waste products that have been discarded incorrectly, without consent, at an unsuitable location. The waste is objects, often man-made, such as aluminum cans, paper cups, food wrappers, cardboard boxes or plastic bottles, but ...

, in soil, in tree hollows

A tree hollow or tree hole is a semi-enclosed cavity which has naturally formed in the trunk or branch of a tree. They are found mainly in old trees, whether living or not. Hollows form in many species of trees. They are a prominent feature of n ...

, under stones, in caves such as the Movile Cave

Movile Cave () is a cave near Mangalia, Constanța County, Romania discovered in 1986 by Cristian Lascu during construction work a few kilometers from the Black Sea coast. It is notable for its unique subterranean groundwater ecosystem abund ...

, at the seashore in the intertidal zone, and within fractured rocks.

'' Chelifer cancroides'' is the species most commonly found in homes, where it is often observed in rooms with dusty books. There, the tiny animals () can find their food such as booklice and house dust mites

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air condi ...

. They enter homes by riding insects (phoresy

Phoresis or phoresy is a temporary commensalistic relationship when an organism (a phoront or phoretic) attaches itself to a host organism solely for travel. It has been seen in ticks and mites since the 18th century, and in fossils 320 ...

) larger than themselves, or are brought in with firewood.

Evolution

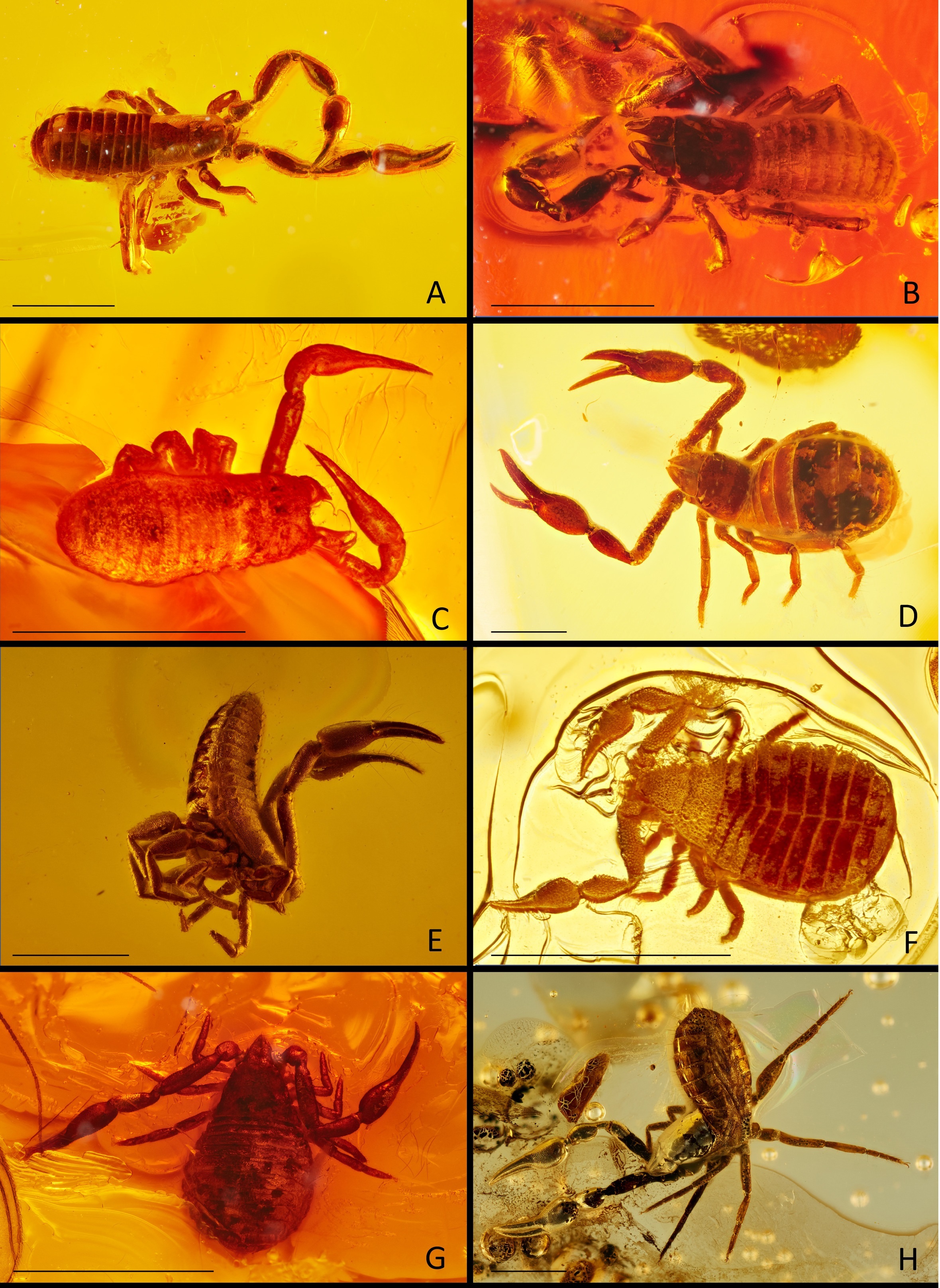

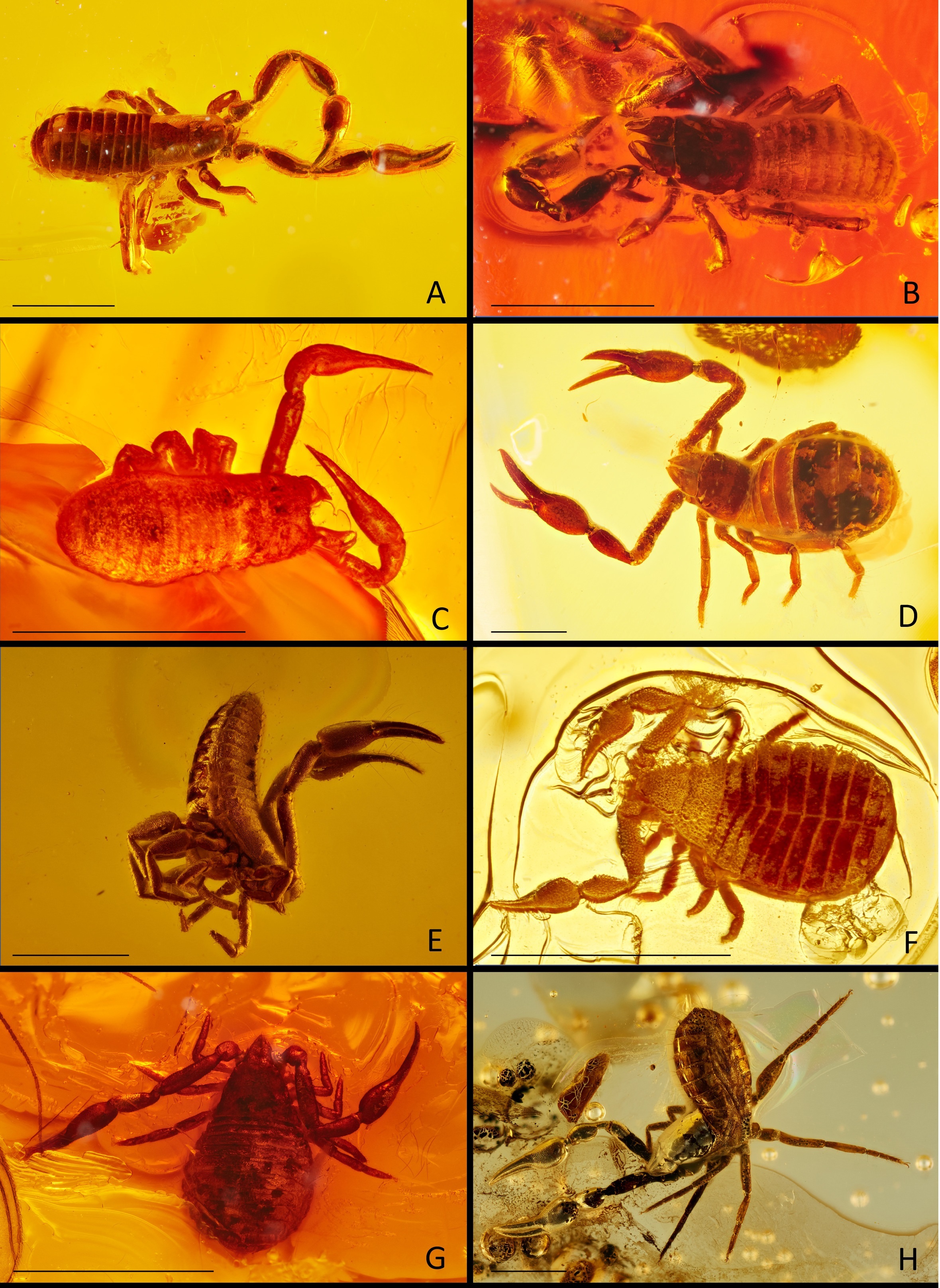

The oldest known fossil pseudoscorpion, '' Dracochela deprehendor'' is known from

The oldest known fossil pseudoscorpion, '' Dracochela deprehendor'' is known from cuticle

A cuticle (), or cuticula, is any of a variety of tough but flexible, non-mineral outer coverings of an organism, or parts of an organism, that provide protection. Various types of "cuticle" are non- homologous, differing in their origin, structu ...

fragments of nymphs found in the Panther Mountain Formation

The Panther Mountain Formation is a Formation (stratigraphy), geologic formation in New York (state), New York. It preserves fossils dating back to the Devonian Period (geology), period. It is located in the counties of Albany County, New York, ...

near Gilboa in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

, dating to the mid-Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a period (geology), geologic period and system (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era during the Phanerozoic eon (geology), eon, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the preceding Silurian per ...

, around 383 million years ago. It has all of the traits of a modern pseudoscorpion, indicating that the order evolved very early in the history of land animals. Its morphology suggests that it is more primitive than any living pseudoscorpion. As with most other arachnid orders, the pseudoscorpions have changed very little since they first appeared, retaining almost all the features of their original form. After the Devonian fossils, almost no other fossils of pseudoscorpions are known for over 250 million years until Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

fossils in amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin. Examples of it have been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since the Neolithic times, and worked as a gemstone since antiquity."Amber" (2004). In Maxine N. Lurie and Marc Mappen (eds.) ''Encyclopedia ...

, all belonging to modern families, suggesting that the major diversification of pseudoscorpions had already taken place by this time. The only fossil from this time gap is '' Archaeofeaella'' from the Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

of Ukraine, approximately 227 million years ago, which is suggested to be an early relative of the family Feaellidae.

Historical references

Pseudoscorpions were first described byAristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

, who probably found them among scrolls in a library where they would have been feeding on booklice. Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath who was active as a physicist ("natural philosopher"), astronomer, geologist, meteorologist, and architect. He is credited as one of the first scientists to investigate living ...

referred to a "Land-Crab" in his 1665 work ''Micrographia

''Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses. With Observations and Inquiries Thereupon'' is a historically significant book by Robert Hooke about his observations through various lenses. It wa ...

''. Another reference in the 1780s, when George Adams wrote of "a lobster-insect, spied by some labouring men who were drinking their porter

Porter may refer to:

Companies

* Porter Airlines, Canadian airline based in Toronto

* Porter Chemical Company, a defunct U.S. toy manufacturer of chemistry sets

* Porter Motor Company, defunct U.S. car manufacturer

* H.K. Porter, Inc., a locom ...

, and borne away by an ingenious gentleman, who brought it to my lodging."

Classification

The following taxon numbers are calculated as of the end of 2023. * Atemnidae Kishida, 1929 (21 genera, 194 species) * Bochicidae Chamberlin, 1930 (12 genera, 44 species) *Cheiridiidae

Cheiridiidae is a family of pseudoscorpions belonging to the order Pseudoscorpiones. It was described in 1894 by Danish zoologist Hans Jacob Hansen.

Genera:

* ''Apocheiridium'' Chamberlin, 1924

* ''Cheiridium'' Menge, 1855

* ''Cryptocheiridium'' ...

Hansen, 1894 (9 genera, 81 species)

* Cheliferidae Risso, 1827 (64 genera, 312 species)

*Chernetidae

Chernetidae is a family of pseudoscorpions, first described by Anton Menge in 1855.

Genera

, the ''World Pseudoscorpiones Catalog'' accepts the following 119 genera:

* '' Acanthicochernes'' Beier, 1964

* '' Acuminochernes'' Hoff, 1949

* '' Ade ...

Menge, 1855 (120 genera, 728 species)

*Chthoniidae

Chthoniidae is a family of pseudoscorpions within the superfamily Chthonioidea. The family contains more than 600 species in about 30 genera. Fossil species are known from Baltic, Dominican, and Burmese amber.Biology Catalog Chthoniidae now inc ...

Daday, 1888 (54 genera, 909 species)

* Feaellidae Ellingsen, 1906 (8 genus, 37 species)

* Garypidae Simon, 1879 (11 genera, 110 species)

* Garypinidae Daday, 1888 (21 genera, 94 species)

* Geogarypidae Chamberlin, 1930 (2 genera, 81 species)

* Gymnobisiidae Beier, 1947 (4 genera, 17 species)

* Hyidae Chamberlin, 1930 (2 genera, 41 species)

* Ideoroncidae Chamberlin, 1930 (15 genera, 86 species)

* Larcidae Harvey, 1992 (1 genus, 15 species)

* Menthidae Chamberlin, 1930 (5 genera, 12 species)

*Neobisiidae

Neobisiidae is a family of pseudoscorpions distributed throughout Africa, the Americas and Eurasia and consist of 748 species in 34 genera. Some species live in caves while some are surface-dwelling.

Characteristics

The body color ranges from re ...

Chamberlin, 1930 (34 genera, 748 species)

*Olpiidae

Olpiidae is a family of pseudoscorpions in the superfamily Garypoidea. It contains the following genera:

Distribution and Habitat

They occur in a wide variety of microhabitats, including litter, soil, moss, under stones or in decaying logs, an ...

Banks, 1895 (24 genera, 211 species)

* Parahyidae Harvey, 1992 (1 genus, 1 species)

* Pseudochiridiidae Chamberlin, 1923 (2 genera, 13 species)

* Pseudogarypidae Chamberlin, 1923 (2 genera, 12 species)

* Pseudotyrannochthoniidae Beier, 1932 (6 genera, 80 species)

*Sternophoridae

The Sternophoridae are a family of pseudoscorpions with about 20 described species in three genera. While ''Afrosternophorus'' is an Old World genus, found mainly in Australasia (with, despite its name, only one African species), the other two ge ...

Chamberlin, 1923 (3 genera, 21 species)

*Syarinidae

Syarinidae is a family of pseudoscorpions in the order Pseudoscorpiones. There are at least 20 genera and 110 described species in Syarinidae.

Genera

These 20 genera belong to the family Syarinidae:

* '' Aglaochitra'' J. C. Chamberlin, 1952

* ...

Chamberlin, 1930 (18 genera, 125 species)

* Withiidae Chamberlin, 1931 (37 genera, 170 species)

*† Dracochelidae Schawaller, Shear & Bonamo, 1991 (1 genus, 1 species)

Cladogram

After Benavides et al., 2019, with historic taxonomic groups from Harvey (1992).References

Further reading

* Mark Harvey (2011)Pseudoscorpions of the World

* Joseph C. Chamberlin (1931): ''The Arachnid Order Chelonethida''. Stanford University Publications in Biological Science. 7(1): 1–284. * Clarence Clayton Hoff (1958): List of the Pseudoscorpions of North America North of Mexico. ''American Museum Novitates''. 1875

* Max Beier (1967): Pseudoscorpione vom kontinentalen Südost-Asien. ''Pacific Insects'' 9(2): 341–369

* * P. D. Gabbutt (1970): Validity of Life History Analyses of Pseudoscorpions. ''Journal of Natural History'' 4: 1–15. * W. B. Muchmore (1982): ''Pseudoscorpionida''. In "Synopsis and Classification of Living Organisms." Vol. 2. Parker, S.P. * J. A. Coddington, S. F. Larcher & J. C. Cokendolpher (1990): ''The Systematic Status of Arachnida, Exclusive of Acari, in North America North of Mexico.'' In "Systematics of the North American Insects and Arachnids: Status and Needs." National Biological Survey 3. ''Virginia Agricultural Experiment Station, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University''. * Mark S. Harvey (1991): ''Catalogue of the Pseudoscorpionida.'' (edited by V . Mahnert). Manchester University Press, Manchester.

External links

* *Video of Pseudoscorpions in Ireland

{{Authority control Extant Devonian first appearances