Prussian Estates on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Prussian estates (, ) were representative bodies of

Google Print, p.18-19

/ref> but later becoming a

Google Print, pp. 21–24

/ref> The estates met on average four times per year, and discussed issues such as

Google Print, p. 339

/ref> At first, the estates opposed the Order passively, by denying requests for additional taxes and support in Order wars with Poland; by the 1440s Prussian estates acted openly in defiance of the Teutonic Order, rebelling against the knights and siding with Poland militarily (see Lizard Union,

Google Print, p.58

/ref> On 10 December 1525 at their session in Königsberg the Prussian estates established the

''Die Kirche in Klein Litauen''

(section: 2. Reformatorische Anfänge; ) on

''Lietuvos Evangelikų Liuteronų Bažnyčia''

retrieved on 28 August 2011.

The West and East Prussian Estates, separately (the latter gathering after 1772 representatives of newly formed

The West and East Prussian Estates, separately (the latter gathering after 1772 representatives of newly formed  When in 1813 the defeated and intimidated King Frederick William III, forced into a coalition with France from 1812,Ferdinand Pflug, "Aus den Zeiten der schweren Noth. Nr. 8. Der Landtag zu Königsberg und die Errichtung der Landwehr", in: ''

When in 1813 the defeated and intimidated King Frederick William III, forced into a coalition with France from 1812,Ferdinand Pflug, "Aus den Zeiten der schweren Noth. Nr. 8. Der Landtag zu Königsberg und die Errichtung der Landwehr", in: ''

Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

, first created by the Monastic state of Teutonic Prussia in the 14th century (around the 1370s)Daniel Stone, ''A History of Central Europe'', University of Washington Press, 2001, Google Print, p.18-19

/ref> but later becoming a

devolved

Devolution is the statutory delegation of powers from the central government of a sovereign state to govern at a subnational level, such as a regional or local level. It is a form of administrative decentralization. Devolved territories ...

legislature

A legislature (, ) is a deliberative assembly with the legal authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country, nation or city on behalf of the people therein. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial power ...

for Royal Prussia

Royal Prussia (; or , ) or Polish PrussiaAnton Friedrich Büsching, Patrick Murdoch. ''A New System of Geography'', London 1762p. 588/ref> (Polish: ; German: ) became a province of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, which was annexed follow ...

within the Kingdom of Poland

The Kingdom of Poland (; Latin: ''Regnum Poloniae'') was a monarchy in Central Europe during the Middle Ages, medieval period from 1025 until 1385.

Background

The West Slavs, West Slavic tribe of Polans (western), Polans who lived in what i ...

. They were at first composed of officials of six big cities of the region; Braunsberg (Braniewo), Culm (Chełmno), Elbing (Elbląg), Danzig (Gdańsk), Königsberg (Królewiec) and Thorn (Toruń). Later, representatives of other towns as well as nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally appointed by and ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. T ...

were also included.Karin Friedrich, ''The Other Prussia: Royal Prussia, Poland and Liberty, 1569-1772'', Cambridge University Press, 2006, Google Print, pp. 21–24

/ref> The estates met on average four times per year, and discussed issues such as

commerce

Commerce is the organized Complex system, system of activities, functions, procedures and institutions that directly or indirectly contribute to the smooth, unhindered large-scale exchange (distribution through Financial transaction, transactiona ...

and foreign relations

Foreign policy, also known as external policy, is the set of strategies and actions a State (polity), state employs in its interactions with other states, unions, and international entities. It encompasses a wide range of objectives, includ ...

.

Era of Teutonic Prussia

Originally, theTeutonic Order

The Teutonic Order is a religious order (Catholic), Catholic religious institution founded as a military order (religious society), military society in Acre, Israel, Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Order of Brothers of the German House of Sa ...

created the Estate to appease the local citizens, but over time the relations between the Order and the Estates grew strained, as the Order of knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

s treated the local population with contempt.

Different Prussian holders of the privilege of coinage (among them the Order and some cities), actually committed to issue a Prussian currency of standardised quality, had debased the coins and expanded their circulation in order to finance the wars between Poland and Teutonic Prussia. However, this expansion disturbed the equilibrium of coins circulated to the volume of contractual obligations, only coming down due to a harsh depreciation of all existing nominally fixed contractual obligations by inflating all other non-fixed prices measured by these coins, ending only once the purchasing power

Purchasing power refers to the amount of products and services available for purchase with a certain currency unit. For example, if you took one unit of cash to a store in the 1950s, you could buy more products than you could now, showing that th ...

of every extra issued coin equalled its material and production costs.

"Obligations would be retroactively changed if new coins, too plentifully issued, would be counted as equal to the old ones (1526, lines 307-310)." Thus a law was "passed by the Diet of Teutonic Prussia in 1418 (cf. Max Toeppen, 1878, 320seqq.), smartly regulating the fulfilment of old debts fixed in old currency by adding an agio when repaid by new coins." Thus creditors and recipients of nominally fixed revenues were not to lose by debasement-induced inflation.

As Prussia became increasingly tied economically and politically with Poland, and the wars became more and more devastating to the borderlands, and as the policies and attitude of the King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of Royal elections in Poland, free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electab ...

were more liberal towards the Prussian burghers and nobility than that of the Order, the rift between the Teutonic Knights and their subjects widened.

The Estates drifted towards the Kingdom of Poland

The Kingdom of Poland (; Latin: ''Regnum Poloniae'') was a monarchy in Central Europe during the Middle Ages, medieval period from 1025 until 1385.

Background

The West Slavs, West Slavic tribe of Polans (western), Polans who lived in what i ...

in their political alignment. Norman Housley noted that "The alienation of the Prussian Estates represented a massive political failure on the part of the Order".Norman Housley, ''The Later Crusades, 1274-1580: From Lyons to Alcazar'', Oxford University Press, 1992, Google Print, p. 339

/ref> At first, the estates opposed the Order passively, by denying requests for additional taxes and support in Order wars with Poland; by the 1440s Prussian estates acted openly in defiance of the Teutonic Order, rebelling against the knights and siding with Poland militarily (see Lizard Union,

Prussian Confederation

The Prussian Confederation (, ) was an organization formed on 21 February 1440 at Marienwerder (present-day Kwidzyn) by a group of 53 nobles and clergy and 19 cities in Prussia, to oppose the arbitrariness of the Teutonic Knights. It was based o ...

and the Thirteen Years' War).

Era of Ducal and Royal Prussia within Poland and Poland–Lithuania

The estates eventually became governed by the Kingdom of Poland. First the western part of Prussia, which became known asRoyal Prussia

Royal Prussia (; or , ) or Polish PrussiaAnton Friedrich Büsching, Patrick Murdoch. ''A New System of Geography'', London 1762p. 588/ref> (Polish: ; German: ) became a province of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, which was annexed follow ...

after the Second Peace of Thorn

The Peace of Thorn or Toruń of 1466, also known as the Second Peace of Thorn or Toruń (; ), was a peace treaty signed in the Hanseatic city of Thorn (Toruń) on 19 October 1466 between the Polish king Casimir IV Jagiellon and the Teutonic Knig ...

ended the Thirteen Years' War in 1466, and later the eastern lands, known as Ducal Prussia

The Duchy of Prussia (, , ) or Ducal Prussia (; ) was a duchy in the region of Prussia established as a result of secularization of the Monastic Prussia, the territory that remained under the control of the State of the Teutonic Order until t ...

, after the Prussian Homage

The Prussian Homage or Prussian Tribute (; ) was the formal investiture of Albert, Duke of Prussia ( 1490-1568), with his Duchy of Prussia as a fief of the Kingdom of Poland that took place on 10 April 1525 in the then capital of Kraków, Kin ...

in 1525, became part of the kingdom.Hajo Holborn, ''A History of Modern Germany: 1648-1840'', Princeton University Press, 1982, Google Print, p.58

/ref> On 10 December 1525 at their session in Königsberg the Prussian estates established the

Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

Church in Ducal Prussia by deciding the Church Order.Albertas Juška, ''Mažosios Lietuvos Bažnyčia XVI-XX amžiuje'', Klaipėda: 1997, pp. 742–771, here after the German translatio''Die Kirche in Klein Litauen''

(section: 2. Reformatorische Anfänge; ) on

''Lietuvos Evangelikų Liuteronų Bažnyčia''

retrieved on 28 August 2011.

Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

, then canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the material accepted as officially written by an author or an ascribed author

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western canon, th ...

of the Prince-Bishopric of Warmia

The Prince-Bishopric of Warmia (; ) was a semi-independent ecclesiastical state, ruled by the incumbent ordinary of the Warmia see and comprising one third of the then diocesan area. The Warmia see was a Prussian diocese under the jurisdictio ...

, addressed the Prussian estates with three memoranda, in fact little essays, on currency reform. Debasements continued to ruin Prussian finances, the groat had been debased by 1/5 to 1/6 of its prior bullion

Bullion is non-ferrous metal that has been refined to a high standard of elemental purity. The term is ordinarily applied to bulk metal used in the production of coins and especially to precious metals such as gold and silver. It comes from ...

content. In 1517, 1519 and again in 1526 he suggested to return to the law passed in 1418. However, especially the cities refused that. They had raised most of the funds for the warfares, and now lightened their debt burden by debasing their coins, thus passing on part of the burden to receivers of nominally fixed revenues, such as civic and ecclesiastical creditors and civic, feudal and ecclesiastical collectors of nominally fixed monetarised dues. So Copernicus' effort failed. At least the estates refused to peg the Prussian currency to the Polish (as proposed by Ludwig Dietz), which even suffered a worse debasement than the Prussian.

Under Polish sovereignty, Prussians, particularly those from Royal Prussia, saw their liberties confirmed and expanded; local cities prospered economically (Gdańsk

Gdańsk is a city on the Baltic Sea, Baltic coast of northern Poland, and the capital of the Pomeranian Voivodeship. With a population of 486,492, Data for territorial unit 2261000. it is Poland's sixth-largest city and principal seaport. Gdań ...

became the largest and richest city in the Commonwealth), and local nobility participated in the benefits of Golden Liberty

Golden Liberty (; , ), sometimes referred to as Golden Freedoms, Nobles' Democracy or Nobles' Commonwealth ( or ''Złota wolność szlachecka'') was a political system in the Kingdom of Poland (1385–1569), Kingdom of Poland and, after the Unio ...

, such as the right to elect the king. Royal Prussia, as a direct part of the Kingdom of Poland (and later Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

) had more influence on Polish politics and more privileges than Ducal Prussia, which remained a fief

A fief (; ) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form of feudal alle ...

(for example, while nobles from the Royal Prussia had their own sejmik

A sejmik (, diminutive of ''sejm'', occasionally translated as a ''dietine''; ) was one of various local parliaments in the history of Poland and history of Lithuania. The first sejmiks were regional assemblies in the Kingdom of Poland (before ...

s, Sejm

The Sejm (), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (), is the lower house of the bicameralism, bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of the Third Polish Republic since the Polish People' ...

and Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

representatives, those from the Duchy did not). Royal Prussia also had its own parliament, the Prussian

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, the House of Hohenzoll ...

'' Landesrat'', although it was partially incorporated into the Commonwealth Sejm after the Union of Lublin

The Union of Lublin (; ) was signed on 1 July 1569 in Lublin, Poland, and created a single state, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, one of the largest countries in Europe at the time. It replaced the personal union of the Crown of the Kingd ...

, it retained distinct features of Royal Prussia.

Era of the Kingdom of Prussia

With the power of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth waning from the mid-17th century onwards, the Prussian Estates drifted under the influence of theHohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern (, ; , ; ) is a formerly royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) German dynasty whose members were variously princes, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzollern, Brandenburg, Prussia, the German Empire, and Romania. ...

Electors of Brandenburg

This article lists the Margraves and Electors of Brandenburg during the time when Brandenburg was a constituent state of the Holy Roman Empire.

The Mark, or ''March'', of Brandenburg was one of the primary constituent states of the Holy Roman Emp ...

, who ruled Ducal Prussia in personal union with Brandenburg from 1618 (first the eastern Duchy of Prussia

The Duchy of Prussia (, , ) or Ducal Prussia (; ) was a duchy in the region of Prussia established as a result of secularization of the Monastic Prussia, the territory that remained under the control of the State of the Teutonic Order until t ...

, sovereign after the Treaty of Wehlau

The Treaty of Bromberg (, Latin: Pacta Bydgostensia) or Treaty of Bydgoszcz was a treaty between John II Casimir of Poland and Elector Frederick William of Brandenburg-Prussia that was ratified at Bromberg (Bydgoszcz) on 6 November 1657. The t ...

in 1657 and upgraded to the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (, ) was a German state that existed from 1701 to 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946. It played a signif ...

in 1701; then the western Royal Prussia, annexed to the former after the First Partition of Poland

The First Partition of Poland took place in 1772 as the first of three partitions that eventually ended the existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth by 1795. The growth of power in the Russian Empire threatened the Kingdom of Prussia an ...

in 1772). Under the Hohenzollerns' absolutist rule the power of the Estates increasingly diminished.

The West and East Prussian Estates, separately (the latter gathering after 1772 representatives of newly formed

The West and East Prussian Estates, separately (the latter gathering after 1772 representatives of newly formed East Prussia

East Prussia was a Provinces of Prussia, province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1772 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 1871); following World War I it formed part of the Weimar Republic's ...

, comprising the former Duchy of Prussia and the parts of former Royal Prussia west of the Vistula

The Vistula (; ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest in Europe, at in length. Its drainage basin, extending into three other countries apart from Poland, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra i ...

), again played a role in the transformation from feudal traditional agriculture to agricultural business. The Silesian Wars

The Silesian Wars () were three wars fought in the mid-18th century between Kingdom of Prussia, Prussia (under King Frederick the Great) and Habsburg monarchy, Habsburg Austria (under Empress Maria Theresa) for control of the Central European ...

of 1740-1763 had required high taxes, such that many Prussian tax-payers went into debt. Feudal manor estates were not free property sellable at the will of their holders or – in case of over-indebtedness – by way of execution prompted by the creditors of the holders. So the holders of feudal manor estates found it difficult to borrow against their estates. Therefore, in 1787 the West Prussia

The Province of West Prussia (; ; ) was a province of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and from 1878 to 1919. West Prussia was established as a province of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1773, formed from Royal Prussia of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonweal ...

n estates, and a year later the East Prussian estates, each took on the task of forming credit corporations: the Westpreussische Landschaft and the , respectively.

Members of the Estates, then by status mostly noble landed manor holders, and the circle of potential debtors were literally the same. In order to overcome the restrictions on selling manor estates to fulfil outstanding debts, the manor estate holders formed a corporation of mutually liable debtors. So solvent manor estate holders had to step in for over-indebted borrowers, thus transforming the manor estate holders into a corporation of collective liability. Covering over-indebted borrowers imposed hardship for the solvent manor-estate holders. This affected many opinions and even aroused appeals to abolish the feudal system of manor estate holding, while others demanded the re-establishment of pure feudalism without borrowing at all.

In the Napoleonic era

The Napoleonic era is a period in the history of France and history of Europe, Europe. It is generally classified as including the fourth and final stage of the French Revolution, the first being the National Assembly (French Revoluti ...

(ca 1799-1815) the East Prussian Estates gained some political influence again. King Frederick William III of Prussia

Frederick William III (; 3 August 1770 – 7 June 1840) was King of Prussia from 16 November 1797 until his death in 1840. He was concurrently Elector of Brandenburg in the Holy Roman Empire until 6 August 1806, when the empire was dissolved ...

needed to raise funds in order to pay the enormous French war contributions of thaler

A thaler or taler ( ; , previously spelled ) is one of the large silver coins minted in the states and territories of the Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburg monarchy during the Early Modern period. A ''thaler'' size silver coin has a diameter o ...

140 million imposed after Prussia's defeat of 1806, and making up about an annual pre-war budget of the government. In 1807 the East Prussian Estates made a political bargain on accepting the king as a member within their credit corporation with his royal East Prussian demesne

A demesne ( ) or domain was all the land retained and managed by a lord of the manor under the feudal system for his own use, occupation, or support. This distinguished it from land subinfeudation, sub-enfeoffed by him to others as sub-tenants. ...

s, to be encumbered as security for the Pfandbrief

The Pfandbrief (plural: Pfandbriefe), a mostly triple-A rated German bank debenture, has become the blueprint of many covered bond models in Europe and beyond. The Pfandbrief is collateralized by long-term assets such as property mortgages or pu ...

e to be issued in his favour, which he was to sell to investors, thus raising credit funds.

In return the Estates reached a wider representation of further parts of the population. The reformed body included two new groups:

* the East Prussian free peasants, called (holders of free estates according to Culm law

Kulm law, Culm law or Chełmno Law (; ; ) was a legal constitution for a municipal form of government used in several Central European cities in the Middle Ages and early modern period.

It was initiated on 28 December 1233 in the Monastic State o ...

) and forming a considerable group only in former Teutonic Prussia holding about a sixth of the arable East Prussian land, and

* non-noble holders of manor estates, who had meanwhile acquired 10% of the feudal land mostly by eventual, but complicated and – subject to government authorisation – purchases of manor estates from over-indebted noble landlords.

With representation in the estates the newly represented groups were also entitled to eventually raise credits, obliged to liability for credits of others, but simultaneously gained a say in the Estates assembly.

On 9 October 1807 the reforming Prussian minister Heinrich vom und zum Stein prompted Frederick William III to decree the October Edict (Edict concerning the relieved possession and the free usage of real estate anded propertyas well as the personal relations of the rural population) which generally transformed all kind of landholdings into free allodial

Allodial title constitutes ownership of real property (land, buildings, and fixtures) that is independent of any superior landlord. Allodial title is related to the concept of land held "in allodium", or land ownership by occupancy and defense ...

property.Peter Brandt in collaboration with Thomas Hofmann, ''Preußen: Zur Sozialgeschichte eines Staates''; eine Darstellung in Quellen, edited on behalf of Berliner Festspiele as catalogue to the exhibition on Prussia between 15 May and 15 November 1981, Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1981, (=Preußen; vol. 3), p. 82. This act enormously increased the amount of alienable real estate in Prussia apt to be pledged as security for credits, needed so much to pay the higher taxes in order to finance Napoléon's warfare through the compulsory war contributions to France. Serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

was thus also abolished.The 1.9 million farmers, who were personally free, but whose land was subject to soccage

Socage () was one of the feudal duties and land tenure forms in the English feudal system. It eventually evolved into the freehold tenure called "free and common socage", which did not involve feudal duties. Farmers held land in exchange for ...

, and the 2.5 million liberated serfs, now free peasants, had to redeem the former dues and soccage

Socage () was one of the feudal duties and land tenure forms in the English feudal system. It eventually evolved into the freehold tenure called "free and common socage", which did not involve feudal duties. Farmers held land in exchange for ...

by a payment in instalments to their former lords organised as of 1811 and mostly fulfilled until 1850, with a few cases lasting into the early 20th century. Cf. Peter Brandt in collaboration with Thomas Hofmann, ''Preußen: Zur Sozialgeschichte eines Staates''; eine Darstellung in Quellen, edited on behalf of Berliner Festspiele as catalogue to the exhibition on Prussia between 15 May and 15 November 1981, Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1981, (=Preußen; vol. 3), p. 103. Most remaining legal differences between the estates (classes) were abolished in 1810, when almost all Prussian subjects – former feudal lords, serf

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

s, burghers (city dwellers), free peasants, Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

s etc., turned into citizens of Prussia. The last excepted group - the Jews - became citizens in 1812.

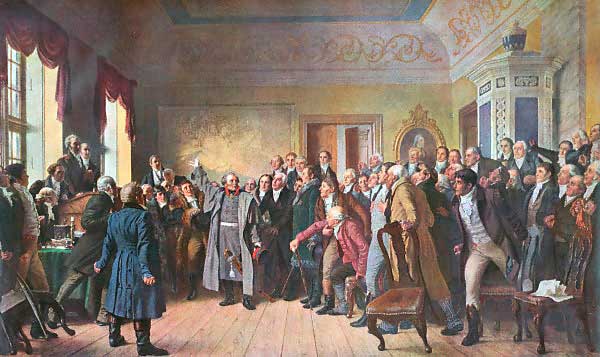

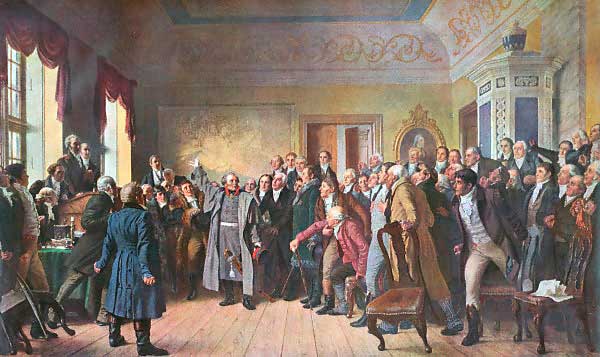

When in 1813 the defeated and intimidated King Frederick William III, forced into a coalition with France from 1812,Ferdinand Pflug, "Aus den Zeiten der schweren Noth. Nr. 8. Der Landtag zu Königsberg und die Errichtung der Landwehr", in: ''

When in 1813 the defeated and intimidated King Frederick William III, forced into a coalition with France from 1812,Ferdinand Pflug, "Aus den Zeiten der schweren Noth. Nr. 8. Der Landtag zu Königsberg und die Errichtung der Landwehr", in: ''Die Gartenlaube

(; ) was the first successful mass-circulation German newspaper and a forerunner of all modern magazines.Sylvia Palatschek: ''Popular Historiographies in the 19th and 20th Centuries'' (Oxford: Berghahn, 2010) p. 41 It was founded by publisher ...

'' (1863), Heft 3-4, pp. 44–56, here p. 44. refrained to take his chance to shake off the French supremacy in the wake of Napoleon's defeats in Russia, the East Prussian estates stole a march on the king. On 23 January Count Friedrich Ferdinand Alexander zu Dohna-Schlobitten

Friedrich Ferdinand Alexander zu Dohna-Schlobitten (29 March 1771 – 31 March 1831) was a Prussian politician.

Early life

Dohna-Schlobitten was born at Finckenstein (today Kamieniec, Poland) to Friedrich Alexander Burggraf und Graf zu Dohna-Sc ...

, president of the Estates assembly, called its members for 5 February 1813.Ferdinand Pflug, "Aus den Zeiten der schweren Noth. Nr. 8. Der Landtag zu Königsberg und die Errichtung der Landwehr", in: ''Die Gartenlaube

(; ) was the first successful mass-circulation German newspaper and a forerunner of all modern magazines.Sylvia Palatschek: ''Popular Historiographies in the 19th and 20th Centuries'' (Oxford: Berghahn, 2010) p. 41 It was founded by publisher ...

'' (1863), Heft 3–4, pp. 44–56, here p. 55.

After debating the appeal of Ludwig Yorck, illoyal and – therefore by Berlin – outlawed general of the Prussian auxiliary corps within Napoléon's army, to form a liberation army, which was widely agreed, on February 7 the East Prussian estates unanimously voted for financing, recruiting and equipping a militia army (Landwehr) of 20,000 men, plus 10,000 in reserve, out of their funds - following a proposal designed by Yorck, Clausewitz

Carl Philipp Gottlieb von Clausewitz ( , ; born Carl Philipp Gottlieb Clauswitz; 1 July 1780 – 16 November 1831) was a Prussian general and military theorist who stressed the "moral" (in modern terms meaning psychological) and political aspe ...

and Stein. The hesitant king could not stop this anymore, but only approve it (17 March 1813).

However, this civic act of initiating Prussia's participation in the liberation wars

Liberation or liberate may refer to:

Film and television

* ''Liberation'' (film series), a 1970–1971 series about the Great Patriotic War

* "Liberation" (''The Flash''), a TV episode

* "Liberation" (''K-9''), an episode

Gaming

* '' Liberati ...

did not meet with the gratitude of the monarch, who again and again procrastinated over his promise to introduce a parliament of genuine legislative competence for all the monarchy. Only in the wake of the Revolutions of 1848

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

did Prussia receive its first constitution providing for the Prussian Landtag

The Landtag of Prussia () was the representative assembly of the Kingdom of Prussia implemented in 1849, a bicameral legislature consisting of the upper House of Lords (''Herrenhaus'') and the lower House of Representatives (''Abgeordnetenhaus'') ...

as the parliament of the kingdom. It consisted of two chambers, the Herrenhaus (Prussian House of Lords

The Prussian House of Lords () in Berlin was the upper house of the Landtag of Prussia (), the parliament of Prussia from 1850 to 1918. Together with the lower house, the House of Representatives (), it formed the Prussian bicameral legislature ...

) and the Abgeordnetenhaus (House of Representatives).

In 1899, the Prussian Landtag moved into a new building consisting of a complex of two structures, one for the House of Lords ( used by the Bundesrat) in Leipziger Straße

Leipziger Straße, or Leipziger Strasse (see ß), is a major thoroughfare in the central Mitte district of Berlin, capital of Germany. It runs from Leipziger Platz, an octagonal square adjacent to Potsdamer Platz in the west, to Spittelmar ...

and one for the House of Representatives in Prinz-Albrecht-Straße, today's Niederkirchnerstraße

Niederkirchnerstraße, or Niederkirchnerstrasse (see ß; ), is a street in Berlin, Germany and was named after Käthe Niederkirchner. The thoroughfare was known as Prinz-Albrecht-Straße until 1951 but the name was changed by the East German go ...

.

The House of Lords was reorganised and renamed into the Staatsrat

The State Council of the German Democratic Republic ( German: ''Staatsrat der DDR'') was the standing organ of the People's Chamber and functioned as the collective head of state of the German Democratic Republic, most commonly referred to as E ...

(state council) of the Free State of Prussia

The Free State of Prussia (, ) was one of the States of the Weimar Republic, constituent states of Weimar Republic, Germany from 1918 to 1947. The successor to the Kingdom of Prussia after the defeat of the German Empire in World War I, it cont ...

after the abolition of the monarchy in 1918. Its members were representatives of the Provinces of Prussia

The Provinces of Prussia () were the main administrative divisions of Prussia from 1815 to 1946. Prussia's province system was introduced in the Prussian Reform Movement, Stein-Hardenberg Reforms in 1815, and were mostly organized from duchies an ...

. Konrad Adenauer

Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer (5 January 1876 – 19 April 1967) was a German statesman and politician who served as the first Chancellor of Germany, chancellor of West Germany from 1949 to 1963. From 1946 to 1966, he was the first leader of th ...

served as its president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

from 1921 to 1933.

Since 1993 the former House of Representatives building has served as the seat of the Abgeordnetenhaus von Berlin

The of Berlin (House of Representatives) () is the state parliament (''Landtag'') of Berlin, Germany according to the city-state's constitution. In 1993, the parliament moved from Rathaus Schöneberg to its present house on Niederkirchnerstraße ...

(House of Representatives of Berlin).

See also

*Sejm of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The General Sejm (, ) was the bicameral legislature of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was established by the Union of Lublin in 1569 following the merger of the legislatures of the two states, the Sejm of the Kingdom of Poland and the ...

* Christian Ludwig von Kalckstein

References

* ''Acten der Ständetage Preussens unter der Herrschaft des Deutschen Ordens'': 5 vols., Max Pollux Toeppen (ed.), Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, 1874–1886; reprint Aalen: Scientia, 1968–1974. . * ''Die preussischen Landtage während der Regentschaft des Markgrafen Georg Friedrich von Ansbach: nach den Landtagsakten dargestellt'', Max Pollux Toeppen (ed.), Allenstein: Königliches Gymnasium zu Hohenstein in Preußen, 1865 * Karol Górski, "Royal Prussian Estates in the Second Half of the Fifteenth Century and Their Relation to the Crown of Poland." in: ''Acta Poloniae Historica'', vol. 10 (1964), pp. 49–64 * Mallek, J., "A Political Triangle: Ducal Prussian Estates, Prussian Rulers and Poland; The Policy of the City of Koenigsberg versus Poland, 1525–1701", in: ''Parliaments Estate and Representation'', 1995, vol. 15; number COM, pp. 25–36 * Mallek, J., "The Royal Prussian estates and the Kingdom of Poland in the years 1454/1466–1569. Centralism and particularism in reciprocity", in: ''Parliaments Estate and Representation'', 2007, vol. 27, pp. 111–128 * Mallek, J., "The Prussian estates and the question of religious toleration, 1500–1800", in: ''Parliaments Estate and Representation'', 1999, vol. 19, pp. 65–72 * Max Pollux Toeppen, ''Die preussischen Landtage zunächst vor und nach dem Tode des Herzogs Albrecht'': 3 vols., Hohenstein: Königliches Gymnasium zu Hohenstein in Preußen, 1855Notes

{{reflist Historical legislatures in Germany Politics of Prussia