Pro-Administration on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Federalist Party was a conservativeMultiple sources:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* and nationalist American political party and the first political party in the United States. It dominated the national government under

Upon taking office in 1789, President Washington nominated his wartime chief of staff

Upon taking office in 1789, President Washington nominated his wartime chief of staff  Hamilton proposed to fund the national and state debts, and Madison and John J. Beckley began organizing a party to oppose it. This " Anti-Administration" faction became what is now called the

Hamilton proposed to fund the national and state debts, and Madison and John J. Beckley began organizing a party to oppose it. This " Anti-Administration" faction became what is now called the

Massachusetts and Connecticut remained the party strongholds. Historian Richard J. Purcell explains how well organized the party was in Connecticut:

The Federalists were conscious of the need to boost voter identification with their party. Elections remained of central importance, but the rest of the political calendar was filled with celebrations, parades, festivals, and visual sensationalism. The Federalists employed multiple festivities, exciting parades, and even quasi-religious pilgrimages and "sacred" days that became incorporated into the

The Federalists were conscious of the need to boost voter identification with their party. Elections remained of central importance, but the rest of the political calendar was filled with celebrations, parades, festivals, and visual sensationalism. The Federalists employed multiple festivities, exciting parades, and even quasi-religious pilgrimages and "sacred" days that became incorporated into the

online

* * Dauer, Manning J. ''The Adams Federalists'' (1953

online

* Dougherty, Keith L. (2020) "TRENDS: Creating Parties in Congress: The Emergence of a Social Network." ''Political Research Quarterly'' 73.4 (2020): 759–773

online

* Elkins, Stanley; McKitrick, Eric (1990). ''The Age of Federalism: The Early American Republic, 1788-1800''. A major scholarly survey

Online free

* Ferling, John. ''John Adams: A Life'' (1992). * * Formisano, Ronald P. (2001). "State Development in the Early Republic" in Shafer, Boyd; Badger, Anthony (eds.). ''Contesting Democracy: Substance and Structure in American Political History, 1775–2000''. pp. 7–35. * Goodman, Paul, ed. ''The Federalists vs. the Jeffersonian Republicans'' (1977

online

short excerpts by leading historians * Hartog, Jonathan J. Den (2015). ''Patriotism and Piety: Federalist Politics and Religious Struggle in the New American Nation''. University of Virginia Press. 280 pp. * Hickey, Donald R (1978). "Federalist Party Unity and the War of 1812". ''Journal of American Studies''. 12#1 pp. 23–39. * Jensen, Richard (2000). "Federalist Party" in ''Encyclopedia of Third Parties''. M. E. Sharpe. * Kerber, Linda K. ''Federalists in dissent; imagery and ideology in Jeffersonian America'' (1970

online

* Kohn, Richard H. ''Eagle and sword : the Federalists and the creation of the military establishment in America, 1783-1802'' (1975

online

* Lampi, Philip J. (2013). "The Federalist Party Resurgence, 1808–1816: Evidence from the New Nation Votes Database". ''Journal of the Early Republic''. 33#2. pp. 255–281

Summary online

* * * Mason, Matthew (March 2009). "Federalists, Abolitionists, and the Problem of Influence". ''American Nineteenth Century History''. 10. pp. 1–27. * Scholarl

online free

* * * * Detailed political history of the 1790s. * General survey. * Stoltz III, Joseph F., “'It Taught Our Enemies a Lesson' The Battle of New Orleans and the Republican Destruction of the Federalist Party", ''Tennessee Historical Quarterly'' 71 (Summer 2012), 112–27. Heavily illustrated * Theriault, Sean M. (2006). "Party Politics during the Louisiana Purchase". ''Social Science History''. 30(2). pp. 293–324. . * Viereck, Peter (1956, 2006) ''Conservative Thinkers from John Adams to Winston Churchill''. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. * Waldstreicher, David. "The Nationalization and Racialization of American Politics: 1790–1840" in Shafer, Boyd; Badger, Anthony (eds.) (2001). ''Contesting Democracy: Substance and Structure in American Political History, 1775–2000''. pp. 37–83. * White, Leonard D. ''The Federalists: a study in administrative history'' (1948

online

the Federalists as government administrators and bureaucrats. * Wood, Gordon S. (2009). ''Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789–1815''

excerpt

online

* Morison, Samuel Eliot. ''Harrison Gray Otis, 1765–1848: The Urbane Federalist'' (1969) on Massachusett

online

* Pasler, Rudolph J., and Margaret C. Pasler. ''The New Jersey Federalists'' (1975

online

* Phillips, Ulrich B. "The South Carolina Federalists, I" ''American Historical Review'' 14#3 (1909), pp. 529–43

online

** "The South Carolina Federalists, II". ''American Historical Review;; 14#4 (1909), pp. 731–43

online

* * Rose, Lisle A. ''Prologue to democracy: The Federalists in the South, 1789-1800'' (1968

online

* Tinkcom, Harry Marlin. ''The Republicans and Federalists in Pennsylvania, 1790-1801: a study in national stimulus and local response'' (1950

online

online

* Pasley, Jeffrey L. '' 'The Tyranny of Printers': Newspaper Politics in the Early American Republic'' (2003

online

* Rollins, Richard. ''The Long Journey of Noah Webster'' (1980); Webster was an important Federalist editor. * Rudanko, Juhani. "" his most unnecessary, unjust, and disgraceful war": Attacks on the Madison Administration in Federalist newspapers during the War of 1812." ''Journal of historical pragmatics'' 12.1-2 (2011): 82-103.

online

* Smith, Steven Carl. '' 'A Rash, Thoughtless, and Imprudent Young Man': John Ward Fenno and the Federalist Literary Network." ''Literature in the Early American Republic'' 6 (2014): 1+ . *

online

primary sources on foreign policy

A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns 1787–1825

Pro-Administration Party ideology over time

Federalist Party ideology over time

{{Authority control 1789 establishments in the United States 1824 disestablishments in the United States American nationalist parties Defunct political parties in the United States Defunct conservative parties in the United States Political parties established in 1789 Political parties disestablished in 1824 Right-wing politics in the United States Conservative parties in the United States Confederation period Conservative liberal parties National conservative parties

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

from 1789 to 1801. The party was defeated by the Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party (also referred to by historians as the Republican Party or the Jeffersonian Republican Party), was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early 1790s. It championed li ...

in 1800, and it became a minority party while keeping its stronghold in New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

. It made a brief resurgence by opposing the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

, then collapsed with its last presidential candidate in 1816. Remnants lasted for a few years afterwards.

The party appealed to businesses who favored banks, national over state government, and manufacturing an army and navy. In world affairs, the party preferred Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

and strongly opposed involvement in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

The French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (sometimes called the Great French War or the Wars of the Revolution and the Empire) were a series of conflicts between the French and several European monarchies between 1792 and 1815. They encompas ...

. The party favored centralization, federalism

Federalism is a mode of government that combines a general level of government (a central or federal government) with a regional level of sub-unit governments (e.g., provinces, State (sub-national), states, Canton (administrative division), ca ...

, modernization, industrialization, and protectionism.

The Federalists called for a strong national government that promoted economic growth and fostered friendly relationships with Great Britain in opposition to Revolutionary France. The Federalist Party came into being between 1789 and 1790 as a national coalition of bankers and businessmen in support of Hamilton's fiscal policies. These supporters worked in every state to build an organized party committed to a fiscally sound and nationalistic government. The only Federalist president was John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before Presidency of John Adams, his presidency, he was a leader of ...

. George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

was broadly sympathetic to the Federalist program, but he remained officially non-partisan during his entire presidency. The Federalist Party controlled the national government until 1801, when it was overwhelmed by the Democratic-Republican opposition led by President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

.

Federalist policies called for a national bank, tariffs, and good relations with Great Britain as expressed in the Jay Treaty

The Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America, commonly known as the Jay Treaty, and also as Jay's Treaty, was a 1794 treaty between the United States and Great Britain that averted ...

negotiated in 1794. Hamilton developed the concept of implied powers and successfully argued the adoption of that interpretation of the Constitution. The Democratic-Republicans led by Jefferson denounced most of the Federalist policies, especially the bank and implied powers, and vehemently attacked the Jay Treaty as a sell-out of American interests to Britain. The Jay Treaty passed and the Federalists won most of the major legislative battles in the 1790s. They held a strong base in the nation's cities and in New England. They factionalized when President Adams secured peace with France, to the anger of Hamilton's larger faction. The Jeffersonians won the presidential election of 1800, and the Federalists never returned to power. They recovered some strength through their intense opposition to the War of 1812, but they practically vanished during the Era of Good Feelings

The Era of Good Feelings marked a period in the political history of the United States that reflected a sense of national purpose and a desire for unity among Americans in the aftermath of the War of 1812. The era saw the collapse of the Fe ...

that followed the end of the war in 1815.

The Federalists left a lasting legacy in the form of a strong federal government. After losing executive power, they decisively shaped Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

policy for another three decades through Chief Justice John Marshall

John Marshall (September 24, 1755July 6, 1835) was an American statesman, jurist, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth chief justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remai ...

.

Background

The term "Federalist

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters call themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of deep ...

" was previously used to refer to a somewhat different coalition of nationalists led by Washington, which advocated replacing the weaker national government under the Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation, officially the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, was an agreement and early body of law in the Thirteen Colonies, which served as the nation's first Constitution, frame of government during the Ameri ...

with a new Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

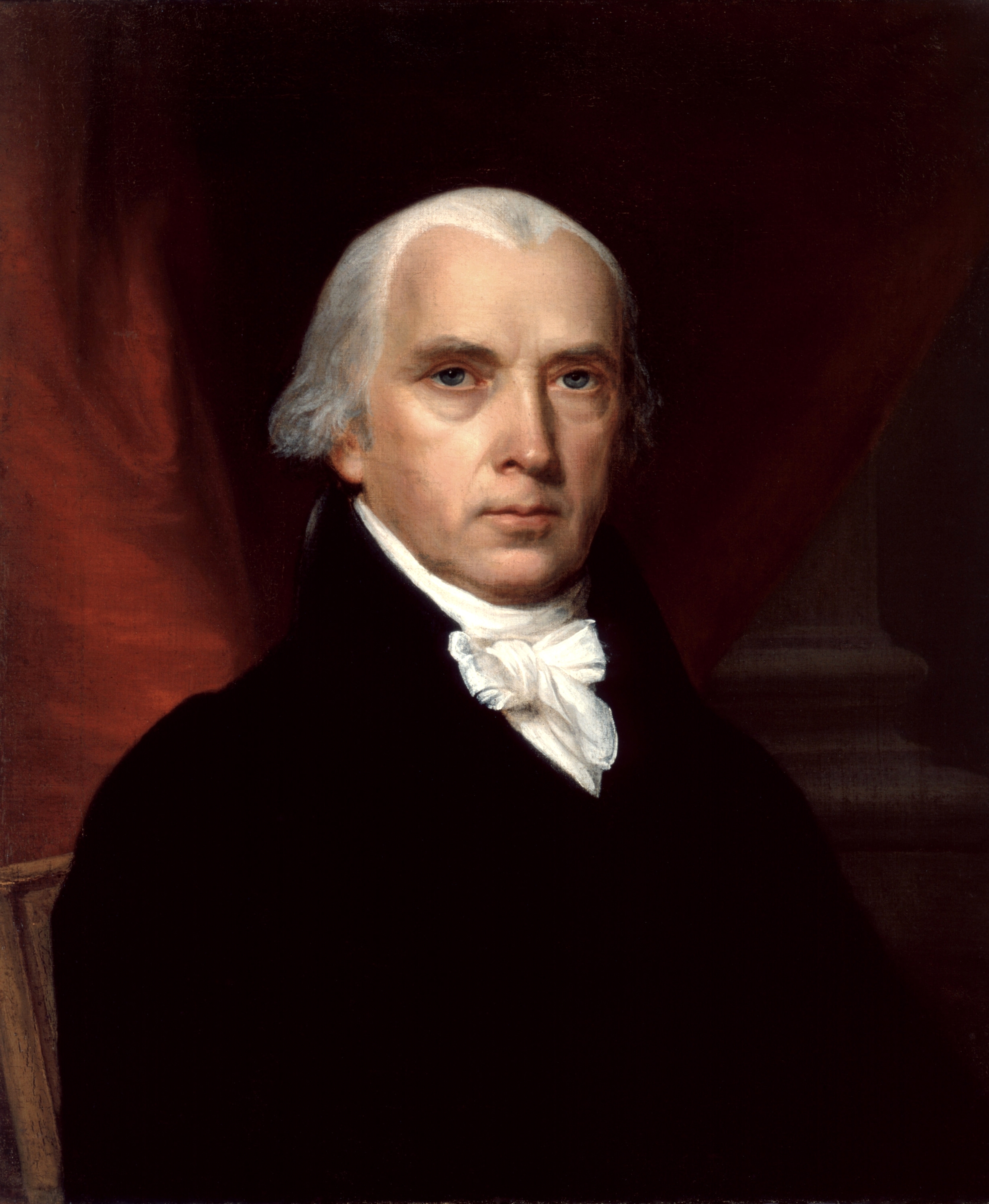

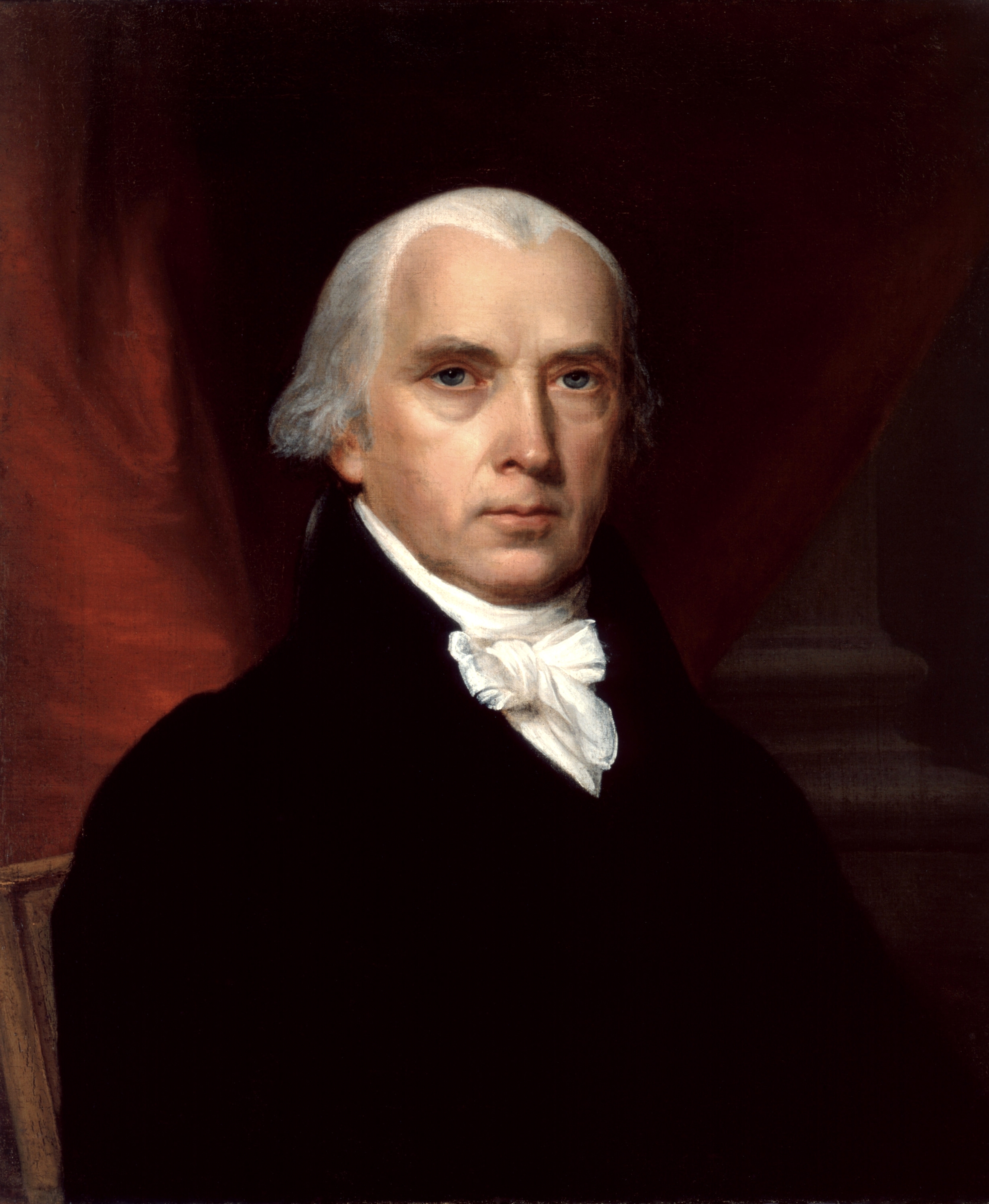

in 1789. This early coalition included Hamilton and James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

.

The Federalists of this time were rivaled by the Anti-Federalists

The Anti-Federalists were a late-18th-century political movement that opposed the creation of a stronger U.S. federal government and which later opposed History of the United States Constitution#1788 ratification, the ratification of the 1787 Uni ...

, who opposed the ratification of the Constitution and objected to creating a stronger central government. The critiques of the Constitution raised by the Anti-Federalists influenced the creation of the Bill of Rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pri ...

. Federalists responded to these objections by promising to add a bill of rights as amendments to the Constitution to satisfy these concerns, which aided in securing acceptance and ratification of the Constitution by the states. The new United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

, initially with a Federalist majority, submitted to the states a series of amendments to guarantee specific freedoms and rights; once ratified, these would become the first ten amendments to the Constitution.

History

Origins (1789–1792)

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

to the new office of Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

. Hamilton wanted a strong national government with financial credibility, and he proposed the ambitious Hamiltonian economic program

In United States history, the Hamiltonian economic program was the set of measures that were proposed by American Founding Father and first Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton in four notable reports and implemented by Congress during ...

that involved the assumption of the state debts incurred during the American Revolution. This created a national debt and the means to pay it off, and it set up a national bank along with tariffs, with James Madison playing major roles in the program. Parties were considered to be divisive and harmful to republicanism, and no similar parties existed anywhere in the world.Chambers, William Nisbet (1963). ''Political Parties in a New Nation''.

By 1789, Hamilton started building a nationwide coalition (a "Pro-Administration" faction), realizing the need for vocal political support in the states. He formed connections with like-minded nationalists and used his network of treasury agents to link together friends of the government, especially merchants and bankers, in the new nation's dozen major cities. His attempts to manage politics in the national capital to get his plans through Congress brought strong responses across the country. In the process, what began as a capital faction soon assumed status as a national faction and then as the new Federalist Party. The Federalist Party supported Hamilton's vision of a strong centralized government and agreed with his proposals for a national bank and heavy government subsidies. In foreign affairs, they supported neutrality in the war between France and Great Britain.

Hamilton proposed to fund the national and state debts, and Madison and John J. Beckley began organizing a party to oppose it. This " Anti-Administration" faction became what is now called the

Hamilton proposed to fund the national and state debts, and Madison and John J. Beckley began organizing a party to oppose it. This " Anti-Administration" faction became what is now called the Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party (also referred to by historians as the Republican Party or the Jeffersonian Republican Party), was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early 1790s. It championed li ...

, led by Madison and Thomas Jefferson. This party attracted many Anti-Federalists who were wary of a centralized government.

Rise (1793–1796)

By the early 1790s, newspapers started calling Hamilton supporters "Federalists" and their opponents "Republicans", "Jeffersonians", or "Democratic-Republicans". Jefferson's supporters usually called themselves "Republicans" and their party the "Republican Party". The Federalist Party became popular with businessmen and New Englanders, as Republicans were mostly farmers who opposed a strong central government. Cities were usually Federalist strongholds, whereas frontier regions were heavily Republican. TheCongregationalists

Congregationalism (also Congregational Churches or Congregationalist Churches) is a Reformed Christian (Calvinist) tradition of Protestant Christianity in which churches practice congregational government. Each congregation independently a ...

of New England and the Episcopalians in the larger cities supported the Federalists, while other minority denominations tended toward the Republican camp. Urban Catholics were generally Federalists.

The state networks of both parties began to operate in 1794 or 1795, and patronage became a factor. The winner-takes-all election system opened a wide gap between winners, who got all the patronage, and losers who got none. Hamilton had many lucrative Treasury jobs to dispense—there were 1,700 of them by 1801. Jefferson had one part-time job in the State Department, which he gave to journalist Philip Freneau

Philip Morin Freneau (January 2, 1752 – December 18, 1832) was an American poet, nationalist, polemicist, sea captain and early American newspaper editor sometimes called the "Poet of the American Revolution". Through his Philadelphia-b ...

to attack the Federalists. In New York, George Clinton won the election for governor and used the vast state patronage fund to help the Republican cause.

Washington tried and failed to moderate the feud between his two top cabinet members.Miller, ''The Federalist Era 1789–1801'' (1960). He was re-elected without opposition in 1792

Events

January–March

* January 9 – The Treaty of Jassy ends the Russian Empire's war with the Ottoman Empire over Crimea.

* January 25 – The London Corresponding Society is founded.

* February 18 – Thomas Holcrof ...

. The Democratic-Republicans nominated New York's Governor Clinton to replace Federalist John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before Presidency of John Adams, his presidency, he was a leader of ...

as vice president, but Adams won. The balance of power in Congress was close, with some members still undecided between the parties. In early 1793, Jefferson secretly prepared resolutions introduced by Virginia Congressman William Branch Giles

William Branch Giles (August 12, 1762December 4, 1830) was an American statesman, long-term United States Senate, Senator from Virginia, and the List of governors of Virginia, 24th Governor of Virginia. He served in the United States House of R ...

designed to repudiate Hamilton and weaken the Washington Administration. Hamilton defended his administration of the nation's complicated financial affairs, which none of his critics could decipher until the arrival in Congress of Republican Albert Gallatin

Abraham Alfonse Albert Gallatin (January 29, 1761 – August 12, 1849) was a Genevan-American politician, diplomat, ethnologist, and linguist. Often described as "America's Swiss Founding Father", he was a leading figure in the early years ...

in 1793.

Federalists counterattacked by claiming that the Hamiltonian program had restored national prosperity, as shown in one 1792 anonymous newspaper essay:

To what physical, moral, or political energy shall this flourishing state of things be ascribed? There is but one answer to these inquiries: Public credit is restored and established. The general government, by uniting and calling into action the pecuniary resources of the states, has created a new capital stock of several millions of dollars, which, with that before existing, is directed into every branch of business, giving life and vigor to industry in its infinitely diversified operation. The enemies of the general government, the funding act and the National Bank may bellow tyranny, aristocracy, and speculators through the Union and repeat the clamorous din as long as they please; but the actual state of agriculture and commerce, the peace, the contentment and satisfaction of the great mass of people, give the lie to their assertions.Jefferson wrote on 12 February 1798:

French Revolution

The French Revolution and the subsequent war between royalist Britain and republican France decisively shaped American politics in 1793–1800 and threatened to entangle the country in wars that "mortally threatened its very existence". The French revolutionaries guillotined KingLouis XVI

Louis XVI (Louis-Auguste; ; 23 August 1754 – 21 January 1793) was the last king of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. The son of Louis, Dauphin of France (1729–1765), Louis, Dauphin of France (son and heir- ...

in January 1793, and subsequently declared war on Britain. The French king had been decisive in helping the United States achieve independence, but now he was dead and many of the pro-American aristocrats in France were exiled or executed. Federalists warned that American republicans threatened to replicate the horrors of the French Revolution and successfully mobilized most conservatives and many clergymen. The Republicans, some of whom had been strong Francophiles, responded with support even through the Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (French: ''La Terreur'', literally "The Terror") was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the French First Republic, First Republic, a series of massacres and Capital punishment in France, nu ...

, when thousands were guillotined, though it was at this point that many began backing away from their pro-France leanings. Many of those executed had been friends of the United States, such as the Comte D'Estaing

Jean Baptiste Charles Henri Hector, Count of Estaing (24 November 1729 – 28 April 1794) was a French military officer and writer. He began his service as a soldier in the War of the Austrian Succession, briefly spending time as a prisoner of wa ...

, whose fleet had fought alongside the Americans in the Revolution ( Lafayette had already fled into exile, and Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In ...

went to prison in France). The republicans denounced Hamilton, Adams and even Washington as friends of Britain, as secret monarchists

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. C ...

, aristocrats

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense economic, political, and social influence. In Western Christian co ...

and as enemies of the republican values. The level of rhetoric reached a fever pitch.Smelser, "The Jacobin Phrenzy: Federalism and the Menace of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity," ''Review of Politics'' 13 (1951) 457–82.

In 1793, Paris sent a new minister, Edmond-Charles Genêt

Edmond-Charles Genêt (January 8, 1763July 14, 1834), also known as Citizen Genêt, was the French envoy to the United States appointed by the Girondins during the French Revolution. His actions on arriving in the United States led to a major po ...

(known as ''Citizen Genêt''), who systematically mobilized pro-French sentiment and encouraged Americans to support France's war against Britain and Spain. Genêt funded local Democratic-Republican Societies that attacked Federalists. He hoped for a favorable new treaty and for repayment of the debts owed to France. Acting aggressively, Genêt outfitted privateer

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign o ...

s that sailed with American crews under a French flag and attacked British shipping. He tried to organize expeditions of Americans to invade Spanish Louisiana and Spanish Florida. When Secretary of State Jefferson told Genêt he was pushing American friendship past the limit, Genêt threatened to go over the government's head and rouse public opinion on behalf of France. Even Jefferson agreed this was blatant foreign interference in domestic politics. Genêt's extremism seriously embarrassed the Jeffersonians and cooled popular support for promoting the French Revolution and getting involved in its wars. Recalled to Paris for execution, Genêt kept his head and instead went to New York, where he became a citizen and married the daughter of Governor Clinton. Jefferson left office, ending the coalition cabinet and allowing the Federalists to dominate.

The Jay Treaty

The Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America, commonly known as the Jay Treaty, and also as Jay's Treaty, was a 1794 treaty between the United States and Great Britain that averted ...

battle in 1794–1795 was the effort by Washington, Hamilton and John Jay

John Jay (, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, diplomat, signatory of the Treaty of Paris (1783), Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served from 1789 to 1795 as the first chief justice of the United ...

to resolve numerous difficulties with Britain. Some of these issues dated to the Revolution, such as boundaries, debts owed in each direction and the continued presence of British forts in the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from part of the unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolution. Established ...

. In addition, the United States hoped to open markets in the British Caribbean and end disputes stemming from the naval war between Britain and France. Most of all the goal was to avert a war with Britain—a war opposed by the Federalists, that some historians claim the Jeffersonians wanted.

As a neutral party, the United States argued it had the right to carry goods anywhere it wanted. The British nevertheless seized American ships carrying goods from the French West Indies

The French West Indies or French Antilles (, ; ) are the parts of France located in the Antilles islands of the Caribbean:

* The two overseas departments of:

** Guadeloupe, including the islands of Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Les Saintes, Ma ...

. The Federalists favored Britain in the war and by far most of America's foreign trade was with Britain, hence a new treaty was called for. The British agreed to evacuate the western forts, open their West Indies ports to American ships, allow small vessels to trade with the French West Indies and set up a commission that would adjudicate American claims against Britain for seized ships and British claims against Americans for debts incurred before 1775. One possible alternative was war with Britain, a war that the United States was ill-prepared to fight.

The Republicans wanted to pressure Britain to the brink of war (and assumed that the United States could defeat a weak Britain). Therefore, they denounced the Jay Treaty as an insult to American prestige, a repudiation of the American-French alliance of 1777 and a severe shock to Southern planters who owed those old debts and who would now be never compensated for their escaped slaves who fled to British lines for their freedom. Republicans protested against the treaty and organized their supporters. The Federalists realized they had to mobilize their popular vote, so they mobilized their newspapers, held rallies, counted votes and especially relied on the prestige of President Washington. The contest over the Jay Treaty marked the first flowering of grassroots political activism in the United States, directed and coordinated by two national parties. Politics was no longer the domain of politicians as every voter was called on to participate. The new strategy of appealing directly to the public worked for the Federalists as public opinion shifted to support the Jay Treaty. The Federalists controlled the Senate and they ratified it by exactly the necessary two-thirds vote vote (20–10) in 1795. However, the Republicans did not give up and public opinion swung toward the Republicans after the Treaty fight and in the South the Federalists lost most of the support they had among planters.

Whiskey Rebellion

Theexcise tax

file:Lincoln Beer Stamp 1871.JPG, upright=1.2, 1871 U.S. Revenue stamp for 1/6 barrel of beer. Brewers would receive the stamp sheets, cut them into individual stamps, cancel them, and paste them over the Bunghole, bung of the beer barrel so when ...

of 1791 caused grumbling from the frontier including threats of tax resistance

Tax resistance is the refusal to pay tax because of opposition to the government that is imposing the tax, or to government policy, or as opposition to taxation in itself. Tax resistance is a form of direct action and, if in violation of the ta ...

. Corn, the chief crop on the frontier, was too bulky to ship over the mountains to market unless it was first distilled into whiskey. This was profitable as the United States population consumed per capita relatively large quantities of liquor. After the excise tax, the backwoodsmen complained the tax fell on them rather than on the consumers. Cash poor, they were outraged that they had been singled out to pay off the "financiers and speculators" back in the East and to pay the salaries of the federal revenue officers who began to swarm the hills looking for illegal stills.

Insurgents in western Pennsylvania shut the courts and hounded federal officials, but Jeffersonian leader Albert Gallatin

Abraham Alfonse Albert Gallatin (January 29, 1761 – August 12, 1849) was a Genevan-American politician, diplomat, ethnologist, and linguist. Often described as "America's Swiss Founding Father", he was a leading figure in the early years ...

mobilized the western moderates and thus forestalled a serious outbreak. Washington, seeing the need to assert federal supremacy, called out 13,000 state militia and marched toward Washington, Pennsylvania

Washington, also known as Little Washington to distinguish it from the District of Columbia, is a city in Washington County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. The population was 13,176 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 censu ...

to suppress this Whiskey Rebellion

The Whiskey Rebellion (also known as the Whiskey Insurrection) was a violent tax protest in the United States beginning in 1791 and ending in 1794 during the presidency of George Washington. The so-called "whiskey tax" was the first tax impo ...

. The rebellion evaporated in late 1794 as Washington approached, personally leading the army (only two sitting Presidents have directly led American military forces, Washington during the Whiskey Rebellion and Madison in an attempt to save the White House during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

). The rebels dispersed and there was no fighting. Federalists were relieved that the new government proved capable of overcoming rebellion while Republicans, with Gallatin their new hero, argued there never was a real rebellion and the whole episode was manipulated in order to accustom Americans to a standing army

A standing army is a permanent, often professional, army. It is composed of full-time soldiers who may be either career soldiers or conscripts. It differs from army reserves, who are enrolled for the long term, but activated only during wars ...

.

Angry petitions flowed in from three dozen Democratic-Republican Societies created by Citizen Genêt. Washington attacked the societies as illegitimate and many disbanded. Federalists now ridiculed Republicans as "democrats" (meaning in favor of mob rule

Mob rule or ochlocracy or mobocracy is a pejorative term describing an oppressive majoritarian form of government controlled by the common people through the intimidation of authorities. Ochlocracy is distinguished from democracy or similarl ...

) or "Jacobins

The Society of the Friends of the Constitution (), renamed the Society of the Jacobins, Friends of Freedom and Equality () after 1792 and commonly known as the Jacobin Club () or simply the Jacobins (; ), was the most influential List of polit ...

" (a reference to the Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (French: ''La Terreur'', literally "The Terror") was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the French First Republic, First Republic, a series of massacres and Capital punishment in France, nu ...

in France).

Washington refused to run for a third term, establishing a two-term precedent that was to stand until 1940 and eventually to be enshrined in the Constitution as the 22nd Amendment. He warned in his Farewell Address against involvement in European wars and lamented the rising north–south sectionalism and party spirit in politics that threatened national unity: The party spirits serves always to distract the Public Councils, and enfeeble the Public Administration. It agitates the Community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms; kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection. It opens the door to foreign influence and corruption, which find a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passions. Thus the policy and the will of one country are subjected to the policy and will of another.Washington never considered himself a member of any party, but broadly supported most Federalist policies.

Adams's administration (1797–1800)

Hamilton distrusted Vice President Adams—who felt the same way about Hamilton—but was unable to block his claims to the succession. The election of 1796 was the first partisan affair in the nation's history and one of the more scurrilous in terms of newspaper attacks. Adams swept New England and Jefferson the South, with the middle states leaning to Adams. Adams was the winner by a margin of threeelectoral votes

An electoral college is a body whose task is to elect a candidate to a particular office. It is mostly used in the political context for a constitutional body that appoints the head of state or government, and sometimes the upper parliamenta ...

and Jefferson, as the runner-up, became vice president under the system set out in the Constitution prior to the ratification of the 12th Amendment.

The Federalists were strongest in New England, but also had strengths in the middle states. They elected Adams as president in 1796, when they controlled both houses of Congress, the presidency, eight state legislatures and ten governorships.

Foreign affairs continued to be the central concern of American politics, for the war raging in Europe threatened to drag in the United States. Historian Sarah Kreps in 2018 argues the Federalist faction led by President Adams during the 1798 Quasi-War could correspond to "today's right-of-center party."

The new president was a loner, who made decisions without consulting Hamilton or other "High Federalists". Benjamin Franklin once quipped that Adams was a man always honest, often brilliant and sometimes mad. Adams was popular among the Federalist rank and file, but had neglected to build state or local political bases of his own and neglected to take control of his own cabinet. As a result, his cabinet answered more to Hamilton than to himself. Hamilton was especially popular because he rebuilt the Army—and had commissions to give out.

Alien and Sedition Acts

After an American delegation was insulted in Paris in theXYZ affair

The XYZ Affair was a political and diplomatic episode in 1797 and 1798, early in the presidency of John Adams, involving a confrontation between the History of the United States (1789–1849), United States and French First Republic, Republican ...

(1797), public opinion ran strongly against the French. An undeclared "Quasi-War

The Quasi-War was an undeclared war from 1798 to 1800 between the United States and the French First Republic. It was fought almost entirely at sea, primarily in the Caribbean and off the East Coast of the United States, with minor actions in ...

" with France from 1798 to 1800 saw each side attacking and capturing the other's shipping. It was called "quasi" because there was no declaration of war, but escalation was a serious threat. At the peak of their popularity, the Federalists took advantage by preparing for an invasion by the French Army. To silence Administration critics, the Federalists passed the Alien and Sedition Acts

The Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 were a set of four United States statutes that sought, on national security grounds, to restrict immigration and limit 1st Amendment protections for freedom of speech. They were endorsed by the Federalist Par ...

in 1798. The Alien Act empowered the President to deport such aliens as he declared to be dangerous. The Sedition Act made it a crime to print false, scandalous and malicious criticisms of the federal government, but it conspicuously failed to criminalize criticism of Vice President Thomas Jefferson.

Several Republican newspaper editors were convicted under the Act and fined or jailed and three Democratic-Republican newspapers were shut down. In response, Jefferson and Madison secretly wrote the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions

The Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions were political statements drafted in 1798 and 1799 in which the Kentucky and Virginia legislatures took the position that the federal Alien and Sedition Acts were unconstitutional. The resolutions argued ...

passed by the two states' legislatures that declared the Alien and Sedition Acts unconstitutional and insisted the states had the power to nullify federal laws.

Undaunted, the Federalists created a navy

A navy, naval force, military maritime fleet, war navy, or maritime force is the military branch, branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral z ...

, with new frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and maneuvera ...

s; and a large new army, with Washington in nominal command and Hamilton in actual command. To pay for it all, they raised taxes on land, houses and slaves, leading to serious unrest. In one part of Pennsylvania, the Fries' Rebellion broke out, with people refusing to pay the new taxes. John Fries was sentenced to death for treason, but received a pardon from Adams. In the elections of 1798, the Federalists did very well, but this issue started hurting the Federalists in 1799. Early in 1799, Adams decided to free himself from Hamilton's overbearing influence, stunning the country and throwing his party into disarray by announcing a new peace mission to France. The mission eventually succeeded, the "Quasi-War" ended and the new army was largely disbanded. Hamiltonians called Adams a failure while Adams fired Hamilton's supporters still in the cabinet.

Hamilton and Adams intensely disliked one another, and the Federalists split between supporters of Hamilton (''High Federalists'') and supporters of Adams. Hamilton became embittered over his loss of political influence and wrote a scathing criticism of Adams' performance as president in an effort to throw Federalist support to Charles Cotesworth Pinckney

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney (February 25, 1746 – August 16, 1825) was an American statesman, military officer and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as List of ambassadors of the United States to France, United S ...

. Inadvertently, this split the Federalists and helped give the victory to Jefferson.Manning Dauer, ''The Adams Federalists'' (Johns Hopkins UP, 1953).

Election of 1800

Adams's peace moves proved popular with the Federalist rank and file and he seemed to stand a good chance of re-election in 1800. If theThree-Fifths Compromise

The Three-fifths Compromise, also known as the Constitutional Compromise of 1787, was an agreement reached during the 1787 United States Constitutional Convention over the inclusion of slaves in counting a state's total population. This count ...

had not been enacted, he most likely would have won reelection since many Federalist legislatures removed the right to select electors from their constituents in fear of a Democratic victory. Jefferson was again the opponent and Federalists pulled out all stops in warning that he was a dangerous revolutionary, hostile to religion, who would weaken the government, damage the economy and get into war with Britain. Many believed that if Jefferson won the election, it would be the end of the newly formed United States. The Republicans crusaded against the Alien and Sedition laws as well as the new taxes and proved highly effective in mobilizing popular discontent.

The election hinged on New York as its electors were selected by the legislature

A legislature (, ) is a deliberative assembly with the legal authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country, nation or city on behalf of the people therein. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial power ...

and given the balance of North and South, they would decide the presidential election. Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr Jr. (February 6, 1756 – September 14, 1836) was an American politician, businessman, lawyer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third vice president of the United States from 1801 to 1805 d ...

brilliantly organized his forces in New York City in the spring elections for the state legislature. By a few hundred votes, he carried the city—and thus the state legislature—and guaranteed the election of a Republican president. As a reward, he was selected by the Republican caucus

A caucus is a group or meeting of supporters or members of a specific political party or movement. The exact definition varies between different countries and political cultures.

The term originated in the United States, where it can refer to ...

in Congress as their vice-presidential candidate. Alexander Hamilton, knowing the election was lost anyway, went public with a sharp attack on Adams that further divided and weakened the Federalists.

Members of the Republican Party planned to vote evenly for Jefferson and Burr because they did not want for it to seem as if their party was divided. The party took the meaning literally and Jefferson and Burr tied in the election with 73 electoral votes. This sent the election to the House of Representatives to break the tie. The Federalists had enough weight in the House to swing the election in either direction. Many would rather have seen Burr in the office over Jefferson, but Hamilton, who had a strong dislike of Burr, threw his political weight behind Jefferson. During the election, neither Jefferson nor Burr attempted to swing the election in the House of Representatives. Jefferson remained at Monticello to oversee the laying of bricks to a section of his home. Jefferson allowed for his political beliefs and other ideologies to filter out through letters to his contacts. Thanks to Hamilton's support, Jefferson would win the election and Burr would become his vice president.

The 1800 election marked the first time power had been transferred between opposing political parties, an act that occurred remarkably without bloodshed. Though there had been strong words and disagreements, contrary to the Federalists fears, there was no war and no ending of one-government system to let in a new one. His patronage policy was to let the Federalists disappear through attrition. Those Federalists such as John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diploma ...

(John Adams' own son) and Rufus King

Rufus King (March 24, 1755April 29, 1827) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father, lawyer, politician, and diplomat. He was a delegate from Massachusetts to the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convent ...

willing to work with him were rewarded with senior diplomatic posts, but there was no punishment of the opposition.

Collapse (1801–1806)

Jefferson had a very successful first term, typified by theLouisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase () was the acquisition of the Louisiana (New France), territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. This consisted of most of the land in the Mississippi River#Watershed, Mississipp ...

, which was supported by Hamilton, but opposed by most Federalists at the time as unconstitutional. Some Federalist leaders ( Essex Junto) began courting Jefferson's vice president and Hamilton's nemesis Aaron Burr in an attempt to swing New York into an independent confederation with the New England states, which along with New York were supposed to secede from the United States after Burr's election to Governor. However, Hamilton's influence cost Burr the governorship of New York, a key in the Essex Junto's plan, just as Hamilton's influence had cost Burr the presidency nearly four years before. Hamilton's thwarting of Aaron Burr's ambitions for the second time was too much for Burr to bear. Hamilton had known of the Essex Junto (whom Hamilton now regarded as apostate Federalists) and Burr's plans and opposed them vehemently. This opposition by Hamilton would lead to his fatal duel with Burr in July 1804.

The thoroughly disorganized Federalists hardly offered any opposition to Jefferson's reelection in 1804 and Federalists seemed doomed. Jefferson had taken away most of their patronage, including federal judgeships. The party now controlled only five state legislatures and seven governorships. After again losing the presidency in 1804, the party was now down to three legislatures and five governorships (four in New England). Their majorities in Congress were long gone, dropping in the Senate from 23 in 1796, and 21 in 1800 to only six in 1804. In New England and in some districts in the middle states, the Federalists clung to power, but the tendency from 1800 to 1812 was steady slippage almost everywhere as the Republicans perfected their organization and the Federalists tried to play catch-up. Some younger leaders tried to emulate the Democratic-Republican tactics, but their overall disdain of democracy along with the upper class bias of the party leadership eroded public support. In the South, the Federalists steadily lost ground everywhere.

The Federalists continued for several years to be a major political party in New England and the Northeast, but never regained control of the presidency or the Congress. With the death of Washington and Hamilton and the retirement of Adams, the Federalists were left without a strong leader as Chief Justice John Marshall

John Marshall (September 24, 1755July 6, 1835) was an American statesman, jurist, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth chief justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remai ...

stayed out of politics. However, a few younger leaders did appear, notably Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the 14th and 19th United States Secretary of State, U.S. secretary o ...

. Federalist policies favored factories, banking and trade over agriculture and therefore became unpopular in the growing Western states. They were increasingly seen as aristocratic and unsympathetic to democracy. In the South, the party had lingering support in Maryland, but elsewhere was crippled by 1800 and faded away by 1808.Google BooksMassachusetts and Connecticut remained the party strongholds. Historian Richard J. Purcell explains how well organized the party was in Connecticut:

It was only necessary to perfect the working methods of the organized body of office-holders who made up the nucleus of the party. There were the state officers, the assistants, and a large majority of the Assembly. In every county there was a sheriff with his deputies. All of the state, county, and town judges were potential and generally active workers. Every town had several justices of the peace, school directors and, in Federalist towns, all the town officers who were ready to carry on the party's work. Every parish had a "standing agent", whose anathemas were said to convince at least ten voting deacons. Militia officers, state's attorneys, lawyers, professors and schoolteachers were in the van of this "conscript army". In all, about a thousand or eleven hundred dependent officer-holders were described as the inner ring which could always be depended upon for their own and enough more votes within their control to decide an election. This was the Federalist machine.After 1800, the major Federalist role came in the judiciary. Although Jefferson managed to repeal the

Judiciary Act of 1801

The Midnight Judges Act (also known as the Judiciary Act of 1801; , and officially An act to provide for the more convenient organization of the Courts of the United States) expanded the federal judiciary of the United States. The act was supporte ...

and thus dismissed many lower-level Federalist federal judges, the effort to impeach Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase

Samuel Chase (April 17, 1741 – June 19, 1811) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father of the United States, signer of the Continental Association and United States Declaration of Independence as a representative of Maryla ...

in 1804 failed. Led by the last great Federalist, John Marshall as Chief Justice from 1801 to 1835, the Supreme Court carved out a unique and powerful role as the protector of the Constitution and promoter of nationalism.

Revival (1807–1815)

Embargo Act

As the wars in Europe intensified, the United States became increasingly involved. The Federalists restored some of their strength by leading the anti-war opposition to Jefferson and Madison between 1807 and 1814. President Jefferson imposed an embargo on Britain in 1807 as theEmbargo Act of 1807

The Embargo Act of 1807 was a general trade embargo on all foreign nations that was enacted by the United States Congress. Much broader than the ineffectual 1806 Non-importation Act, it represented an escalation of attempts to persuade Br ...

prevented all American ships from sailing to a foreign port. The idea was that the British were so dependent on American supplies that they would come to terms. For 15 months, the Embargo wrecked American export businesses, largely based in the Boston-New York region, causing a sharp depression in the Northeast. Evasion was common and Jefferson and Treasury Secretary Gallatin responded with tightened police controls more severe than anything the Federalists had ever proposed. Public opinion was highly negative and a surge of support breathed fresh life into the Federalist Party.

As Jefferson refrained from seeking a third term, the Republicans nominated Madison for the presidency in 1808. Meeting in the first-ever national convention, Federalists considered the option of nominating Jefferson's Vice President George Clinton (who represented a different Clintonian party faction from New York, had run for the Republican candidacy in 1804 and had not wanted to become vice president) as their own candidate, but balked at working with him and again chose Charles Cotesworth Pinckney

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney (February 25, 1746 – August 16, 1825) was an American statesman, military officer and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as List of ambassadors of the United States to France, United S ...

, their 1804 candidate. Madison lost New England excluding Vermont, but swept the rest of the country and carried a Republican Congress. Madison dropped the Embargo, opened up trade again and offered a carrot and stick approach. If either France or Britain agreed to stop their violations of American neutrality, the United States would cut off trade with the other country. Tricked by French Emperor Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

into believing France had acceded to his demands, Madison turned his wrath on Britain and the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

began. Young Daniel Webster, running for Congress from New Hampshire in 1812, first gained overnight fame with his anti-war speeches.

War of 1812

The nation was at war during the 1812 presidential election and war was the burning issue. Opposition to the war was strong in traditional Federalist strongholds in New England and New York, where the party made a comeback in the elections of 1812 and 1814. In their second national convention in 1812, the Federalists, now the peace party, nominatedDeWitt Clinton

DeWitt Clinton (March 2, 1769February 11, 1828) was an American politician and Naturalism (philosophy), naturalist. He served as a United States Senate, United States senator, as the mayor of New York City, and as the sixth governor of New York. ...

, the dissident Republican Mayor of New York City

The mayor of New York City, officially mayor of the City of New York, is head of the executive branch of the government of New York City and the chief executive of New York City. The Mayoralty in the United States, mayor's office administers all ...

and an articulate opponent of the war, who had followed his uncle George Clinton as the leader of the Clintonian faction after his death. Madison ran for reelection promising a relentless war against Britain and an honorable peace. Clinton, denouncing Madison's weak leadership and incompetent preparations for war, could count on New England and New York. To win, he needed the middle states and there the campaign was fought out. Those states were competitive and had the best-developed local parties and most elaborate campaign techniques, including nominating conventions and formal party platform

A political party platform (American English), party program, or party manifesto (preferential term in British and often Commonwealth English) is a formal set of principal goals which are supported by a political party or individual candidate, t ...

s. The Tammany Society in New York City highly favored Madison and the Federalists finally adopted the club idea in 1808. Their Washington Benevolent Societies were semi-secret membership organizations which played a critical role in every northern state as they held meetings and rallies and mobilized Federalist votes. New Jersey went for Clinton, but Madison carried Pennsylvania and thus was reelected with 59% of the electoral votes. However, the Federalists gained 14 seats in Congress.

The War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

went poorly for the Americans for two years. Even though Britain was concentrating its military efforts on its war with Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

, the United States still failed to make any headway on land and was effectively blockaded at sea by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

. The British raided and burned Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

in 1814 and sent a force to capture New Orleans.

The war was especially unpopular in New England. The New England economy was highly dependent on trade and the British blockade threatened to destroy it entirely. In 1814, the British Navy finally managed to enforce their blockade on the New England coast, so the Federalists of New England sent delegates to the Hartford Convention

The Hartford Convention was a series of meetings from December 15, 1814, to January 5, 1815, in Hartford, Connecticut, United States, in which New England leaders of the Federalist Party met to discuss their grievances concerning the ongoing War ...

in December 1814.

During the proceedings of the Hartford Convention, secession from the Union was discussed, though the resulting report listed a set of grievances against the Democratic-Republican federal government and proposed a set of Constitutional amendments to address these grievances. They demanded financial assistance from Washington to compensate for lost trade and proposed constitutional amendments requiring a two-thirds vote in Congress before an embargo could be imposed, new states admitted, or war declared. It also indicated that if these proposals were ignored, then another convention should be called and given "such powers and instructions as the exigency of a crisis may require". The Federalist Massachusetts Governor had already secretly sent word to England to broker a separate peace accord. Three Massachusetts "ambassadors" were sent to Washington to negotiate on the basis of this report.

By the time the Federalist "ambassadors" got to Washington, the war was over and news of Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

's stunning victory in the Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815, between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the Frenc ...

had raised American morale immensely. The "ambassadors" hastened back to Massachusetts, but not before they had done fatal damage to the Federalist Party. The Federalists were thereafter associated with the disloyalty and parochialism of the Hartford Convention and destroyed as a political force. Across the nation, Republicans used the great victory at New Orleans to ridicule the Federalists as cowards, defeatists and secessionists. Pamphlets, songs, newspaper editorials, speeches and entire plays on the Battle of New Orleans drove home the point.

Decline (1816–1828)

The Federalists fielded their last presidential candidate,Rufus King

Rufus King (March 24, 1755April 29, 1827) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father, lawyer, politician, and diplomat. He was a delegate from Massachusetts to the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convent ...

in 1816. With the party's passing, partisan hatreds and newspaper feuds declined and the nation entered the "Era of Good Feelings

The Era of Good Feelings marked a period in the political history of the United States that reflected a sense of national purpose and a desire for unity among Americans in the aftermath of the War of 1812. The era saw the collapse of the Fe ...

". Federalism in states like Massachusetts gradually blended into the conservative wing of the Democratic-Republicans. In the 1824 presidential election, New Englanders from both parties supported Adams, a native of the region. However, a few old Federalist leaders, who never forgave Adams for abandoning them, formed a ticket of unpledged elector

In United States presidential elections, an unpledged elector is a person nominated to stand as an elector but who has not pledged to support any particular presidential or vice presidential candidate, and is free to vote for any candidate when el ...

s with radical Democratic-Republicans. This ticket was overwhelmingly defeated and likely would have voted for Crawford.

Following 1824, no Federalist ran for governor of any state and most left for the National Republicans. After the dissolution of the final Federalist congressional caucus in 1825, the last traces of Federalist activity came in Delaware and Massachusetts local politics in the late 1820s. In other states there still technically existed Federalists (for example James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

) but they were engaged in patronage with either Jackson or Adams. In Massachusetts, the Federalist Party ceased to function as a state organization in 1825, surviving only as a local Boston group for the next three years. In Delaware, the Federalist Party lasted until 1826 and controlled the Delaware House of Representatives

The Delaware State House of Representatives is the lower house of the Delaware General Assembly, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Delaware. It is composed of 41 Representatives from an equal number of constituencies, each of whom is ...

. When Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the 14th and 19th United States Secretary of State, U.S. secretary o ...

, representative of Boston, resigned in 1827 to run for U.S. Senator, a caucus of Federalists met in Boston to nominate his replacement. A young William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was an Abolitionism in the United States, American abolitionist, journalist, and reformism (historical), social reformer. He is best known for his widely read anti-slavery newspaper ''The ...

persuaded the caucus to choose the Federalist Harrison Gray Otis, who ultimately declined. The caucus then nominated the Anti-Jacksonian Benjamin Gorham, their original choice.

In the 1828 presidential election, the Federalists were used as a scapegoat in Boston. The Democratic Boston ''Statesman'' accused Adams of being a secret Hartford Federalist attempting to revive the "reign of terror" under his father. Adams responded by accusing the old Hartford Federalists of treason and attempting to dissolve the union to form their own confederation. The ''Jackson Republican'', an ally of the Statesman and founded by former Federalist Theodore Lyman II, implicated Webster among the old Federalists Adams intended to impugn, leading to a libel suit. As a protest against Adams, several "Federal young men" who had been supporting Adams nominated a Federalist ticket of presidential electors. This ticket, headed by Otis and William Prescott Jr. and including three other members of the Hartford Convention, garnered a pitiful 156 votes in Boston and none elsewhere in the state. As with the previous election, Adams swept the city and state.

That ticket, according to the best of knowledge of Samuel Eliot Morison

Samuel Eliot Morison (July 9, 1887 – May 15, 1976) was an American historian noted for his works of maritime history and American history that were both authoritative and popular. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard University in 1912, and tau ...

, was "the last ticket ever voted for that bore the name of the once powerful party of Washington and Hamilton."

Ideology and policies

Federalism

Fisher Ames (1758–1808) of Massachusetts ranks as one of the more influential figures of his era. Ames led Federalist ranks in the House of Representatives. His acceptance of theBill of Rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pri ...

garnered support in Massachusetts for the new Constitution. His greatest fame came as an orator who defined the principles of the Federalist Party and the follies of the Republicans. Ames offered one of the first great speeches in American Congressional history when he spoke in favor of the Jay Treaty

The Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America, commonly known as the Jay Treaty, and also as Jay's Treaty, was a 1794 treaty between the United States and Great Britain that averted ...

. Ames was part of Hamilton's faction and cautioned against the excesses of democracy unfettered by morals and reason: "Popular reason does not always know how to act right, nor does it always act right when it knows". He warned his countrymen of the dangers of flattering demagogues, who incite dis-union and lead their country into bondage: "Our country is too big for union, too sordid for patriotism, too democratic for liberty. What is to become of it, He who made it best knows. Its vice will govern it, by practising upon its folly. This is ordained for democracies".

Intellectually, Federalists were profoundly devoted to liberty

Liberty is the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority on one's way of life, behavior, or political views. The concept of liberty can vary depending on perspective and context. In the Constitutional ...

. As Samuel Eliot Morison

Samuel Eliot Morison (July 9, 1887 – May 15, 1976) was an American historian noted for his works of maritime history and American history that were both authoritative and popular. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard University in 1912, and tau ...

explained, they believed that liberty is inseparable from union, that men are essentially unequal, that ''vox populi'' ("voice of the people") is seldom if ever ''vox Dei'' ("the voice of God") and that sinister outside influences are busy undermining American integrity. British historian Patrick Allitt concludes that Federalists promoted many positions that would form the baseline for later American conservatism, including the rule of law under the Constitution, republican government, peaceful change through elections, stable national finances, credible and active diplomacy and protection of wealth.

In terms of "classical conservatism", the Federalists had no truck with European-style aristocracy, monarchy, or established religion. Historian John P. Diggins says: "Thanks to the framers, American conservatism began on a genuinely lofty plane. James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, John Marshall, John Jay, James Wilson, and, above all, John Adams aspired to create a republic in which the values so precious to conservatives might flourish: harmony, stability, virtue, reverence, veneration, loyalty, self-discipline, and moderation. This was classical conservatism in its most authentic expression".

Federalists led the successful battles to abolish the international slave trade in New York City and the battle to abolish slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

in the state of New York. The Federalists' approach to nationalism was coined "open" nationalism in that it creates space for minority groups to have a voice in government. Many Federalists also created space for women to have a significant political role, which was not evident on the Democratic-Republican side.

The Federalists were dominated by businessmen and merchants in the major cities who supported a strong national government. The party was closely linked to the modernizing, urbanizing, financial policies of Alexander Hamilton. These policies included the funding of the national debt and also assumption of state debts incurred during the Revolutionary War, the incorporation of a national Bank of the United States, the support of manufactures and industrial development, and the use of a tariff to fund the Treasury. While it has long been accepted that commercial groups are in support of the Federalists and agrarian groups are in support of the Democratic-Republicans, recent studies have shown that support for Federalists was also evident in agrarian groups. In foreign affairs, the Federalists opposed the French Revolution, engaged in the "Quasi War

The Quasi-War was an undeclared war from 1798 to 1800 between the United States and the French First Republic. It was fought almost entirely at sea, primarily in the Caribbean and off the East Coast of the United States, with minor actions in ...

" (an undeclared naval war) with France in 1798–99, sought good relations with Britain and sought a strong army and navy. Ideologically, the controversy between Democratic-Republicans and Federalists stemmed from a difference of principle and style. In terms of style, the Federalists feared mob rule, thought an educated elite should represent the general populace in national governance and favored national power over state power. Democratic-Republicans distrusted Britain, bankers, merchants and did not want a powerful national government. The Federalists, notably Hamilton, were distrustful of "the people", the French and the Republicans. In the end, the nation synthesized the two positions, adopting representative democracy and a strong nation state. Just as importantly, American politics by the 1820s accepted the two-party system whereby rival parties stake their claims before the electorate and the winner takes control of majority in state legislatures and the Congress and gains governorships and the presidency.

As time went on, the Federalists lost appeal with the average voter and were generally not equal to the tasks of party organization; hence they grew steadily weaker as the political triumphs of the Democratic-Republican Party grew. For economic and philosophical reasons, the Federalists tended to be pro-British—the United States engaged in more trade with Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

than with any other country—and vociferously opposed Jefferson's Embargo Act of 1807 and the seemingly deliberate provocation of war with Britain by the Madison Administration. During "Mr. Madison's War", as they called it, the Federalists made a temporary comeback. However, they lost all their gains and more during the patriotic euphoria that followed the war. The membership was aging rapidly, but a few young men from New England did join the cause, most notably Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the 14th and 19th United States Secretary of State, U.S. secretary o ...

.

After 1816, the Federalists had no national power base apart from John Marshall

John Marshall (September 24, 1755July 6, 1835) was an American statesman, jurist, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth chief justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remai ...

's Supreme Court. They had some local support in New England, New York, eastern Pennsylvania, Maryland and Delaware. After the collapse of the Federalist Party in the course of the 1824 presidential election, most surviving Federalists (including Daniel Webster) joined former Democratic-Republicans like Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

to form the National Republican Party

The National Republican Party, also known as the Anti-Jacksonian Party or simply Republicans, was a political party in the United States which evolved from a conservative-leaning faction of the Democratic-Republican Party that supported John ...

, which was soon combined with other anti-Jackson groups to form the Whig Party in 1833. By then, nearly all remaining Federalists joined the Whigs. However, some former Federalists like James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

, Louis McLane

Louis McLane (May 28, 1786 – October 7, 1857) was an American lawyer and politician from Wilmington, Delaware, Wilmington, in New Castle County, Delaware, and Baltimore, Baltimore, Maryland. He was a veteran of the War of 1812, a member of t ...

and Roger B. Taney

Roger Brooke Taney ( ; March 17, 1777 – October 12, 1864) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the fifth Chief Justice of the United States, chief justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 186 ...

became Jacksonian Democrats.