In the

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, the Electoral College is the group of presidential electors that is formed every four years for the sole purpose of voting for the

president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

and

vice president

A vice president or vice-president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vi ...

in the

presidential election. This process is described in

Article Two of the Constitution. The number of electors from each

state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

is equal to that state's

congressional delegation which is the number of

senators (two) plus the number of

Representatives for that state. Each state

appoints electors using legal procedures determined by its

legislature

A legislature (, ) is a deliberative assembly with the legal authority to make laws for a political entity such as a country, nation or city on behalf of the people therein. They are often contrasted with the executive and judicial power ...

.

Federal office holders, including senators and representatives, cannot be electors. Additionally, the

Twenty-third Amendment granted the federal

District of Columbia

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and Federal district of the United States, federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from ...

three electors (bringing the total number from 535 to 538). A

simple majority of electoral votes (270 or more) is required to elect the president and vice president. If no candidate achieves a majority, a

contingent election

In the United States, a contingent election is used to elect the president or vice president if no candidate receives a majority of the whole number of electors appointed. A presidential contingent election is decided by a special vote of th ...

is held by the

House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

, to elect the president, and by the

Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, to elect the vice president.

The states and the District of Columbia hold a statewide or district-wide popular vote on

Election Day in November to choose electors based upon how they have pledged to vote for president and vice president, with some state laws prohibiting

faithless elector

In the United States Electoral College, a faithless elector is an elector who does not vote for the candidates for U.S. President and U.S. Vice President for whom the elector had pledged to vote, and instead votes for another person for one or ...

s. All states except

Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

and

Nebraska

Nebraska ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Ka ...

use a

party block voting, or general ticket method, to choose their electors, meaning all their electors go to one winning ticket. Maine and Nebraska choose

one elector per congressional district and two electors for the

ticket with the highest statewide vote. The

electors meet and vote in December, and the

inaugurations of the president and vice president take place in January.

The merit of the electoral college system has been a matter of ongoing debate in the United States since its inception at the

Constitutional Convention in 1787, becoming more controversial by the latter years of the 19th century, up to the present day. More resolutions have been submitted to amend the Electoral College mechanism than any other part of the constitution.

An amendment that would have abolished the system was approved by the House in 1969, but failed to move past the Senate.

Supporters argue that it requires presidential candidates to have broad appeal across the country to win, while critics argue that it is not representative of the popular will of the nation. Winner-take-all systems, especially with representation not proportional to population, do not align with the principle of "

one person, one vote

"One man, one vote" or "one vote, one value" is a slogan used to advocate for the principle of equal representation in voting. This slogan is used by advocates of democracy and political equality, especially with regard to electoral reforms like ...

".

Critics object to the inequity that, due to the distribution of electors, individual citizens in states with

smaller populations have more voting power than those in larger states. Because the number of electors each state appoints is equal to the size of its congressional delegation, each state is entitled to at least three electors regardless of its population, and the

apportionment of the statutorily fixed number of the rest is only roughly proportional. This allocation has contributed to runners-up of the

nationwide popular vote being elected president in

1824

Events

January–March

* January 1 – John Stuart Mill begins publication of The Westminster Review. The first article is by William Johnson Fox

* January 8 – After much controversy, Michael Faraday is finally elected as a member of th ...

,

1876

Events

January

* January 1

** The Reichsbank opens in Berlin.

** The Bass Brewery Red Triangle becomes the world's first registered trademark symbol.

*January 27 – The Northampton Bank robbery occurs in Massachusetts.

February

* Febr ...

,

1888,

2000

2000 was designated as the International Year for the Culture of Peace and the World Mathematics, Mathematical Year.

Popular culture holds the year 2000 as the first year of the 21st century and the 3rd millennium, because of a tende ...

, and

2016. In addition, faithless electors may not vote in accord with their pledge.

A further objection is that

swing states receive the most attention from candidates.

By the end of the 20th century, electoral colleges had been abandoned by all other democracies around the world in favor of direct elections for an

executive president

An executive president is the head of state who exercises authority over the governance of that state, and can be found in presidential, semi-presidential, and parliamentary systems.

They contrast with figurehead presidents, common in most parlia ...

.

Procedure

Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the

United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, on March 4, 1789. Originally includi ...

directs each

state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

to appoint a number of electors equal to that state's congressional delegation (the number of members of the

House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

plus two

senators). The same clause empowers each

state legislature to determine the manner by which that state's electors are chosen but prohibits federal office holders from being named electors. Following the national presidential

election day on Tuesday after the first Monday in November,

[Statutes at Large, 28th Congress, 2nd Session]

p. 721

each state, and the federal district, selects its electors according to its laws. After a popular election, the states identify and record their appointed electors in a ''

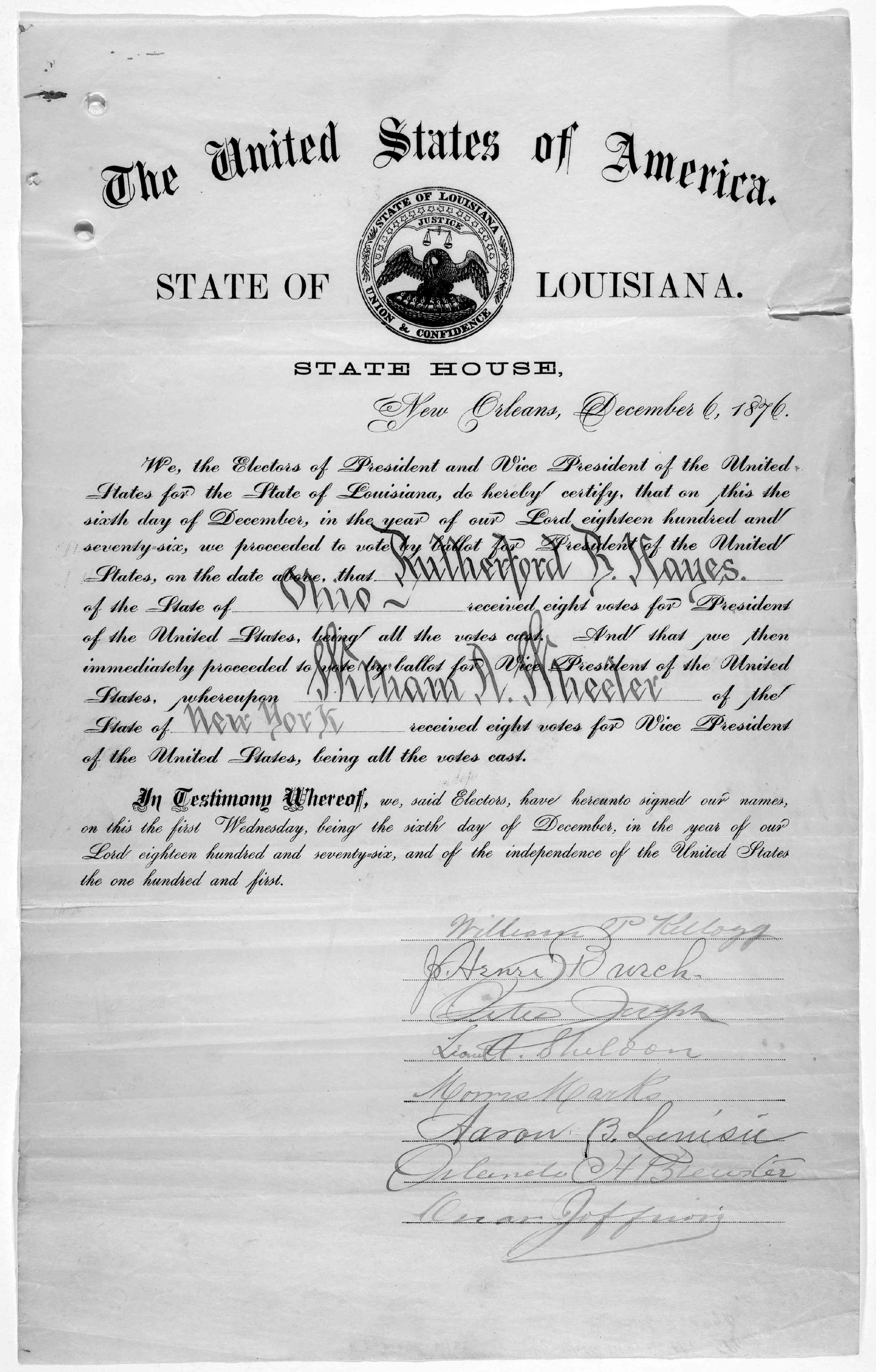

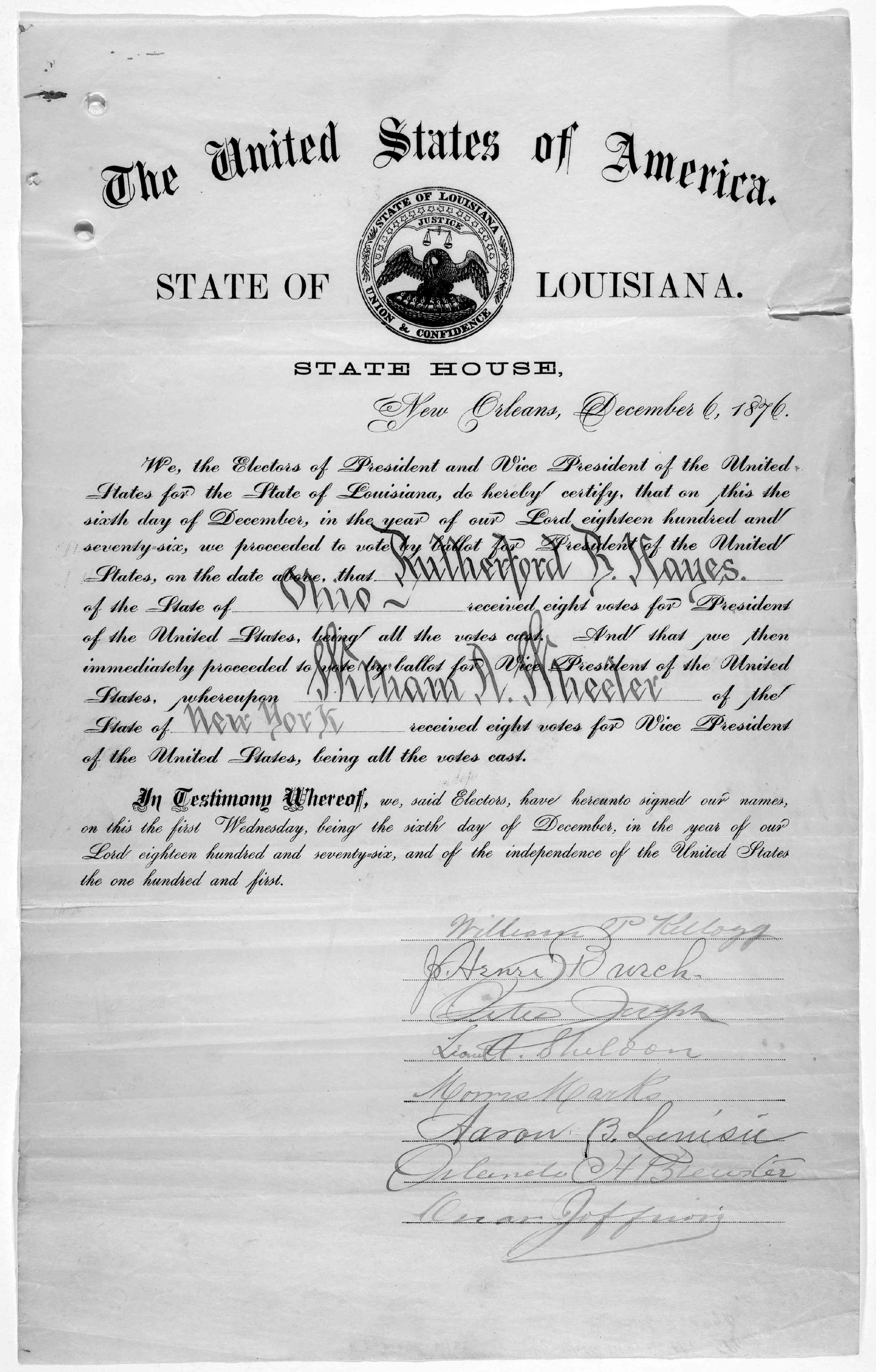

Certificate of Ascertainment'', and those appointed electors then meet in their respective jurisdictions and produce a ''Certificate of Vote'' for their candidate; both certificates are then sent to Congress to be opened and counted.

In 48 of the 50 states, state laws mandate that the winner of the

plurality of the statewide popular vote receives all of that state's electoral votes.

In

Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

and

Nebraska

Nebraska ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Ka ...

, two electoral votes are assigned in this manner, while the remaining electoral votes are allocated based on the plurality of votes in each of their

congressional districts. The federal district,

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, allocates its 3 electoral votes to the winner of its single district election. States generally require electors to pledge to vote for that state's winning ticket; to prevent electors from being

faithless electors, most states have adopted various laws to enforce the electors' pledge.

The electors of each state meet in their respective

state capital

Below is an index of pages containing lists of capital city, capital cities.

National capitals

*List of national capitals

*List of national capitals by latitude

*List of national capitals by population

*List of national capitals by area

*List of ...

on the first Tuesday after the second Wednesday of December, between December 14 and 20, to cast their votes.

The results are sent to and counted by the

Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

, where they are tabulated in the first week of January before a

joint meeting of the Senate and the House of Representatives, presided over by the current vice president, as president of the Senate.

Should a majority of votes not be cast for a candidate, a

contingent election

In the United States, a contingent election is used to elect the president or vice president if no candidate receives a majority of the whole number of electors appointed. A presidential contingent election is decided by a special vote of th ...

takes place: the House holds a presidential election session, where one vote is cast by each of the fifty states. The Senate is responsible for electing the vice president, with each senator having one vote. The elected president and vice president are

inaugurated on January 20.

Since 1964, there have been 538 electors. States select 535 of the electors, this number matches the aggregate total of their congressional delegations.

The additional three electors come from the

Twenty-third Amendment, ratified in 1961, providing that the district established pursuant to

Article I, Section 8, Clause 17 as the

seat of the federal government (namely,

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

) is entitled to the same number of electors as the least populous state. In practice, that results in Washington D.C. being entitled to three electors.

Background

The Electoral College was officially selected as the means of electing president towards the end of the Constitutional Convention, due to pressure from slave states wanting to increase their voting power, since they could count slaves as 3/5 of a person when allocating electors, and by small states who increased their power given the minimum of three electors per state.

The compromise was reached after other proposals, including a

direct election

Direct election is a system of choosing political officeholders in which the voters directly cast ballots for the persons or political party that they want to see elected. The method by which the winner or winners of a direct election are chosen ...

for president (as proposed by Hamilton among others), failed to get traction among slave states.

Steven Levitsky

Steven Robert Levitsky (born January 17, 1968) is an American political scientist and professor of government at Harvard University and a senior fellow for democracy at the Council on Foreign Relations. He is also a senior fellow at the Kette ...

and

Daniel Ziblatt describe it as "not a product of constitutional theory or farsighted design. Rather, it was adopted by default, after all other alternatives had been rejected."

In 1787, the

Constitutional Convention used the

Virginia Plan

The Virginia Plan (also known as the Randolph Plan or the Large-State Plan) was a proposed plan of government for the United States presented at the Constitutional Convention (United States), Constitutional Convention of 1787. The plan called fo ...

as the basis for discussions, as the Virginia proposal was the first. The Virginia Plan called for Congress to elect the president. Delegates from a majority of states agreed to this mode of election. After being debated, delegates came to oppose nomination by Congress for the reason that it could violate the separation of powers.

James Wilson then made a motion for electors for the purpose of choosing the president.

Later in the convention, a committee formed to work out various details. They included the mode of election of the president, including final recommendations for the electors, a group of people apportioned among the states in the same numbers as their representatives in Congress (the formula for which had been resolved in lengthy debates resulting in the

Connecticut Compromise

The Connecticut Compromise, also known as the Great Compromise of 1787 or Sherman Compromise, was an agreement reached during the Constitutional Convention of 1787 that in part defined the legislative structure and representation each state ...

and

Three-Fifths Compromise), but chosen by each state "in such manner as its Legislature may direct". Committee member

Gouverneur Morris

Gouverneur Morris ( ; January 31, 1752 – November 6, 1816) was an American statesman, a Founding Father of the United States, and a signatory to the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution. He wrote the Preamble to the ...

explained the reasons for the change. Among others, there were fears of "intrigue" if the president were chosen by a small group of men who met together regularly, as well as concerns for the independence of the president if he were elected by Congress.

Once the Electoral College had been decided on, several delegates (Mason, Butler, Morris, Wilson, and Madison) openly recognized its ability to protect the election process from cabal, corruption, intrigue, and faction. Some delegates, including James Wilson and James Madison, preferred popular election of the executive. Madison acknowledged that while a popular vote would be ideal, it would be difficult to get consensus on the proposal given the prevalence of

slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

in the South:

The convention approved the committee's Electoral College proposal, with minor modifications, on September 4, 1787. Delegates from states with smaller populations or limited land area, such as Connecticut, New Jersey, and Maryland, generally favored the Electoral College with some consideration for states. At the compromise providing for a runoff among the top five candidates, the small states supposed that the House of Representatives, with each state delegation casting one vote, would decide most elections.

In ''

The Federalist Papers

''The Federalist Papers'' is a collection of 85 articles and essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the collective pseudonym "Publius" to promote the ratification of the Constitution of the United States. The ...

'',

James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

explained his views on the selection of the president and the

Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

. In

Federalist No. 39, Madison argued that the Constitution was designed to be a mixture of

state-based and

population-based government.

Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

would have two houses: the state-based

Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

and the population-based

House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

. Meanwhile, the president would be elected by a mixture of the two modes.

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

in

Federalist No. 68, published on March 12, 1788, laid out what he believed were the key advantages to the Electoral College. The electors come directly from the people and them alone, for that purpose only, and for that time only. This avoided a party-run legislature or a permanent body that could be influenced by foreign interests before each election.

[Hamilton]

The Federalist Papers: No. 68

The Avalon Project, Yale Law School. viewed November 10, 2016. Hamilton explained that the election was to take place among all the states, so no corruption in any state could taint "the great body of the people" in their selection. The choice was to be made by a majority of the Electoral College, as majority rule is critical to the principles of

republican government

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy or electoral democracy, is a types of democracy, type of democracy where elected delegates Representation (politics), represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearl ...

. Hamilton argued that electors meeting in the state capitals were able to have information unavailable to the general public, in a time before telecommunications. Hamilton also argued that since no federal officeholder could be an elector, none of the electors would be beholden to any presidential candidate.

Another consideration was that the decision would be made without "tumult and disorder", as it would be a broad-based one made simultaneously in various locales where the decision makers could deliberate reasonably, not in one place where decision makers could be threatened or intimidated. If the Electoral College did not achieve a decisive majority, then the House of Representatives was to choose the president from among the top five candidates, ensuring selection of a presiding officer administering the laws would have both ability and good character. Hamilton was also concerned about somebody unqualified but with a talent for "low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity" attaining high office.

In the

Federalist No. 10, James Madison argued against "an interested and overbearing majority" and the "mischiefs of faction" in an

electoral system

An electoral or voting system is a set of rules used to determine the results of an election. Electoral systems are used in politics to elect governments, while non-political elections may take place in business, nonprofit organizations and inf ...

. He defined a faction as "a number of citizens whether amounting to a majority or minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community." A republican government (i.e.,

representative democracy

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy or electoral democracy, is a type of democracy where elected delegates represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern Western-style democracies func ...

, as opposed to

direct democracy

Direct democracy or pure democracy is a form of democracy in which the Election#Electorate, electorate directly decides on policy initiatives, without legislator, elected representatives as proxies, as opposed to the representative democracy m ...

) combined with the principles of

federalism

Federalism is a mode of government that combines a general level of government (a central or federal government) with a regional level of sub-unit governments (e.g., provinces, State (sub-national), states, Canton (administrative division), ca ...

(with distribution of voter rights and separation of government powers), would countervail against factions. Madison further postulated in the Federalist No.10 that the greater the population and expanse of the Republic, the more difficulty factions would face in organizing due to such issues as

sectionalism.

Although the United States Constitution refers to "Electors" and "electors", neither the phrase "Electoral College" nor any other name is used to describe the electors collectively. It was not until the early 19th century that the name "Electoral College" came into general usage as the collective designation for the electors selected to cast votes for president and vice president. The phrase was first written into federal law in 1845, and today the term appears in , in the section heading and in the text as "college of electors".

History

Original plan

Article II, Section 1, Clause 3 of the Constitution provided the original plan by which the electors voted for president. Under the original plan, each elector cast two votes for president; electors did not vote for vice president. Whoever received a majority of votes from the electors would become president, with the person receiving the second most votes becoming vice president.

According to Stanley Chang, the original plan of the Electoral College was based upon several assumptions and anticipations of the

Framers of the Constitution:

# Choice of the president should reflect the "sense of the people" at a particular time, not the dictates of a faction in a "pre-established body" such as Congress or the State legislatures, and independent of the influence of "foreign powers".

[Hamilton, Alexander]

"The Federalist Papers : No. 68"

''The Avalon Project,'' 2008. From the Lillian Goldman Law Library. Retrieved 22 Jan 2022.

# The choice would be made decisively with a "full and fair expression of the public will" but also maintaining "as little opportunity as possible to tumult and disorder".

# Individual electors would be elected by citizens on a district-by-district basis. Voting for president would include the widest electorate allowed in each state.

# Each presidential elector would exercise independent judgment when voting, deliberating with the most complete information available in a system that over time, tended to bring about a good administration of the laws passed by Congress.

# Candidates would not pair together on the same

ticket with assumed placements toward each office of president and vice president.

Election expert, William C. Kimberling, reflected on the original intent as follows:

"The function of the College of Electors in choosing the president can be likened to that in the Roman Catholic Church of the College of Cardinals

The College of Cardinals (), also called the Sacred College of Cardinals, is the body of all cardinals of the Catholic Church. there are cardinals, of whom are eligible to vote in a conclave to elect a new pope. Appointed by the pope, ...

selecting the Pope. The original idea was for the most knowledgeable and informed individuals from each State to select the president based solely on merit and without regard to State of origin or political party."

According to Supreme Court justice

Robert H. Jackson, in a dissenting opinion, the original intention of the framers was that the electors would not feel bound to support any particular candidate, but would vote their conscience, free of external pressure.

"No one faithful to our history can deny that the plan originally contemplated, what is implicit in its text, that electors would be free agents, to exercise an independent and nonpartisan judgment as to the men best qualified for the Nation's highest offices."

In support for his view, Justice Jackson cited

Federalist No. 68:

'It was desirable that the sense of the people should operate in the choice of the person to whom so important a trust was to be confided. This end will be answered by committing the right of making it, not to any pre-established body, but to men chosen by the people for the special purpose, and at the particular conjuncture... It was equally desirable, that the immediate election should be made by men most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station, and acting under circumstances favorable to deliberation, and to a judicious combination of all the reasons and inducements which were proper to govern their choice. A small number of persons, selected by their fellow citizens from the general mass, will be most likely to possess the information and discernment requisite to such complicated investigations.'

Philip J. VanFossen of

Purdue University

Purdue University is a Public university#United States, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in West Lafayette, Indiana, United States, and the flagship campus of the Purdue University system. The university was founded ...

explains that the original purpose of the electors was not to reflect the will of the citizens, but rather to "serve as a check on a public who might be easily misled."

Randall Calvert, the Eagleton Professor of Public Affairs and Political Science at

Washington University in St. Louis, stated, "At the framing the more important consideration was that electors, expected to be more knowledgeable and responsible, would actually do the choosing."

Constitutional expert Michael Signer explained that the electoral college was designed "to provide a mechanism where intelligent, thoughtful and statesmanlike leaders could deliberate on the winner of the popular vote and, if necessary, choose another candidate who would not put Constitutional values and practices at risk."

Robert Schlesinger, writing for

U.S. News and World Report, similarly stated, "The original conception of the Electoral College, in other words, was a body of men who could serve as a check on the uninformed mass electorate."

Breakdown and revision

In spite of Hamilton's assertion that electors were to be chosen by mass election, initially, state legislatures chose the electors in most of the states. States progressively changed to selection by popular election. In

1824

Events

January–March

* January 1 – John Stuart Mill begins publication of The Westminster Review. The first article is by William Johnson Fox

* January 8 – After much controversy, Michael Faraday is finally elected as a member of th ...

, there were six states in which electors were still legislatively appointed. By

1832, only

South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

had not transitioned. Since

1864

Events

January

* January 13 – American songwriter Stephen Foster ("Oh! Susanna", "Old Folks at Home") dies aged 37 in New York City, leaving a scrap of paper reading "Dear friends and gentle hearts". His parlor song "Beautiful Dream ...

(with the sole exception of newly admitted Colorado in 1876 for logistical reasons), electors in every state have been chosen based on a popular election held on

Election Day.

[ The popular election for electors means the president and vice president are in effect chosen through ]indirect election

An indirect election or ''hierarchical voting,'' is an election in which voters do not choose directly among candidates or parties for an office ( direct voting system), but elect people who in turn choose candidates or parties. It is one of the o ...

by the citizens.

The emergence of parties and campaigns

The framers of the Constitution did not anticipate political parties

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular area's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or p ...

.George Washington's Farewell Address

Washington's Farewell Address is a letter written by President of the United States, President George Washington as a Valediction, valedictory to "friends and fellow-citizens" after 20 years of public service to the United States. He wrote it ...

in 1796 included an urgent appeal to avert such parties. Neither did the framers anticipate candidates "running" for president. Within just a few years of the ratification of the Constitution, however, both phenomena became permanent features of the political landscape of the United States.

The emergence of political parties

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular area's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or p ...

and nationally coordinated election campaigns soon complicated matters in the elections of 1796

Events

January–March

* January 16 – The first Dutch (and general) elections are held for the National Assembly of the Batavian Republic. (The next Dutch general elections are held in 1888.)

* February 1 – The capital of Upper Can ...

and 1800

As of March 1 ( O.S. February 18), when the Julian calendar acknowledged a leap day and the Gregorian calendar did not, the Julian calendar fell one day further behind, bringing the difference to 12 days until February 28 ( O.S. February 16), ...

. In 1796, Federalist Party

The Federalist Party was a conservativeMultiple sources:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* and nationalist American political party and the first political party in the United States. It dominated the national government under Alexander Hamilton from 17 ...

candidate John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before Presidency of John Adams, his presidency, he was a leader of ...

won the presidential election. Finishing in second place was Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party (also referred to by historians as the Republican Party or the Jeffersonian Republican Party), was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early 1790s. It championed li ...

candidate Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

, the Federalists' opponent, who became the vice president. This resulted in the president and vice president being of different political parties.

In 1800, the Democratic-Republican Party again nominated Jefferson for president and also again nominated Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr Jr. (February 6, 1756 – September 14, 1836) was an American politician, businessman, lawyer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third vice president of the United States from 1801 to 1805 d ...

for vice president. After the electors voted, Jefferson and Burr were tied with one another with 73 electoral votes each. Since ballots did not distinguish between votes for president and votes for vice president, every ballot cast for Burr technically counted as a vote for him to become president, despite Jefferson clearly being his party's first choice. Lacking a clear winner by constitutional standards, the election had to be decided by the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

pursuant to the Constitution's contingency election provision.

Having already lost the presidential contest, Federalist Party representatives in the lame duck House session seized upon the opportunity to embarrass their opposition by attempting to elect Burr over Jefferson. The House deadlocked for 35 ballots as neither candidate received the necessary majority vote of the state delegations in the House (The votes of nine states were needed for a conclusive election.). On the 36th ballot, Delaware's lone Representative, James A. Bayard, made it known that he intended to break the impasse for fear that failure to do so could endanger the future of the Union. Bayard and other Federalists from South Carolina, Maryland, and Vermont abstained, breaking the deadlock and giving Jefferson a majority.

Responding to the problems from those elections, Congress proposed on December 9, 1803, and three-fourths of the states ratified by June 15, 1804, the Twelfth Amendment. Starting with the 1804 election, the amendment requires electors to cast separate ballots for president and vice president, replacing the system outlined in Article II, Section 1, Clause 3.

Evolution from unpledged to pledged electors

Some Founding Fathers hoped that each elector would be elected by the citizens of a district and that elector was to be free to ''analyze'' and ''deliberate'' regarding who is best suited to be president.

In Federalist No. 68 Alexander Hamilton described the Founding Fathers' view of how electors would be chosen:

However, when electors were pledged to vote for a specific candidate, the slate of electors chosen by the state were no longer free agents, independent thinkers, or deliberative representatives. They became, as Justice Robert H. Jackson wrote, "voluntary party lackeys and intellectual non-entities." According to Hamilton, writing in 1788, the selection of the president should be "made by men most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station f president"John Jay

John Jay (, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, diplomat, signatory of the Treaty of Paris (1783), Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served from 1789 to 1795 as the first chief justice of the United ...

's view that the electors' choices would reflect "discretion and discernment."

Reflecting on this original intention, a U.S. Senate report in 1826 critiqued the evolution of the system:

It was the intention of the Constitution that these electors should be an independent body of men, chosen by the people from among themselves, on account of their superior discernment, virtue, and information; and that this select body should be left to make the election ''according to their own will'', without the slightest control from the body of the people. That this intention has failed of its object in every election, is a fact of such universal notoriety that no one can dispute it. Electors, therefore, have not answered the design of their institution. They are not the independent body and superior characters which they were intended to be. They are not left to the exercise of their own judgment: on the contrary, they give their vote, or bind themselves to give it, according to the will of their constituents. They have degenerated into mere agents, in a case which requires no agency, and where the agent must be useless...

In 1833, Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story

Joseph Story (September18, 1779September10, 1845) was an American lawyer, jurist, and politician who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1812 to 1845. He is most remembered for his opinions in ''Martin ...

detailed how badly from the framers' intention the Electoral Process had been "subverted":

In no respect have the views of the framers of the constitution been so completely frustrated as relates to the independence of the electors in the electoral colleges. It is notorious, that the electors are now chosen wholly with reference to particular candidates, and are silently pledged to vote for them. Nay, upon some occasions the electors publicly pledge themselves to vote for a particular person; and thus, in effect, the whole foundation of the system, so elaborately constructed, is subverted.

Story observed that if an elector does what the framers of the Constitution expected him to do, he would be considered immoral:

So, that nothing is left to the electors after their choice, but to register votes, which are already pledged; and an exercise of an independent judgment would be treated, as a political usurpation, dishonorable to the individual, and a fraud upon his constituents.

Evolution to the general ticket

Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the Constitution states:

According to Hamilton, Madison and others, the original intent was that this would take place district by district.Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

in 1820, the rule stated "the people shall vote by ballot, on which shall be designated who is voted for as an Elector for the district." In other words, the name of a candidate for president was ''not'' on the ballot. Instead, citizens voted for their local elector.

Some state leaders began to adopt the strategy that the favorite partisan presidential candidate among the people in their state would have a much better chance if all of the electors selected by their state were sure to vote the same way—a "general ticket" of electors pledged to a party candidate.James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

and Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

, two of the most important architects of the Electoral College, saw this strategy being taken by some states, they protested strongly.

Evolution of selection plans

In 1789, the at-large popular vote, the winner-take-all method, began with Pennsylvania and Maryland. Massachusetts, Virginia and Delaware used a district plan by popular vote, and state legislatures chose in the five other states participating in the election (Connecticut, Georgia, New Hampshire, New Jersey, and South Carolina). New York, North Carolina and Rhode Island did not participate in the election. New York's legislature deadlocked over the method of choosing electors and abstained; North Carolina and Rhode Island had not yet ratified the Constitution.

By 1800, Virginia and Rhode Island voted at large; Kentucky, Maryland, and North Carolina voted popularly by district; and eleven states voted by state legislature. Beginning in 1804 there was a definite trend towards the winner-take-all system for statewide popular vote.[Presidential Elections 1789–1996. Congressional Quarterly, Inc. 1997, , pp. 9–10.]

By 1832, only South Carolina legislatively chose its electors, and it abandoned the method after 1860.

Correlation between popular vote and electoral college votes

Since the mid-19th century, when all electors have been popularly chosen, the Electoral College has elected the candidate who received the most (though not necessarily a majority) popular votes nationwide, except in four elections: 1876

Events

January

* January 1

** The Reichsbank opens in Berlin.

** The Bass Brewery Red Triangle becomes the world's first registered trademark symbol.

*January 27 – The Northampton Bank robbery occurs in Massachusetts.

February

* Febr ...

, 1888, 2000

2000 was designated as the International Year for the Culture of Peace and the World Mathematics, Mathematical Year.

Popular culture holds the year 2000 as the first year of the 21st century and the 3rd millennium, because of a tende ...

, and 2016

2016 was designated as:

* International Year of Pulses by the sixty-eighth session of the United Nations General Assembly.

* International Year of Global Understanding (IYGU) by the International Council for Science (ICSU), the Internationa ...

. A case has also been made that it happened in 1960. In 1824

Events

January–March

* January 1 – John Stuart Mill begins publication of The Westminster Review. The first article is by William Johnson Fox

* January 8 – After much controversy, Michael Faraday is finally elected as a member of th ...

, when there were six states in which electors were legislatively appointed, rather than popularly elected, the true national popular vote is uncertain. The electors in 1824 failed to select a winning candidate, so the matter was decided by the House of Representatives.

Three-fifths clause and the role of slavery

After the initial estimates agreed to in the original Constitution, Congressional and Electoral College reapportionment was made according to a decennial census to reflect population changes, modified by counting three-fifths of slaves. On this basis after the first census, the Electoral College still gave the free men of slave-owning states (but never slaves) extra power (Electors) based on a count of these disenfranchised people, in the choice of the U.S. president.

At the Constitutional Convention, the college composition, in theory, amounted to 49 votes for northern states (in the process of abolishing slavery) and 42 for slave-holding states (including Delaware). In the event, the first (i.e. 1788) presidential election lacked votes and electors for unratified Rhode Island (3) and North Carolina (7) and for New York (8) which reported too late; the Northern majority was 38 to 35. For the next two decades, the three-fifths clause led to electors of free-soil Northern states numbering 8% and 11% more than Southern states. The latter had, in the compromise, relinquished counting two-fifths of their slaves and, after 1810, were outnumbered by 15.4% to 23.2%.

While House members for Southern states were boosted by an average of , a free-soil majority in the college maintained over this early republic and Antebellum period. Scholars conclude that the three-fifths clause had low impact on sectional proportions and factional strength, until denying the North a pronounced supermajority, as to the Northern, federal initiative to abolish slavery. The seats that the South gained from such "slave bonus" were quite evenly distributed between the parties. In the First Party System (1795–1823), the Jefferson Republicans gained 1.1 percent more adherents from the slave bonus, while the Federalists lost the same proportion. At the Second Party System (1823–1837) the emerging Jacksonians gained just 0.7% more seats, versus the opposition loss of 1.6%.

The three-fifths slave-count rule is associated with three or four outcomes, 1792–1860:

* The clause, having reduced the South's power, led to John Adams's win in 1796 over Thomas Jefferson.

* In 1800, historian Garry Wills argues, Jefferson's victory over Adams was due to the slave bonus count in the Electoral College as Adams would have won if citizens' votes were used for each state. However, historian Sean Wilentz points out that Jefferson's purported "slave advantage" ignores an offset by electoral manipulation by anti-Jefferson forces in Pennsylvania. Wilentz concludes that it is a myth to say that the Electoral College was a pro-slavery ploy.

* In 1824, the presidential selection was passed to the House of Representatives, and John Quincy Adams was chosen over Andrew Jackson, who won fewer citizens' votes. Then Jackson won in 1828, but would have lost if the college were citizen-only apportionment. Scholars conclude that in the 1828 race, Jackson benefited materially from the Three-fifths clause by providing his margin of victory.

The first "Jeffersonian" and "Jacksonian" victories were of great importance as they ushered in sustained party majorities of several Congresses and presidential party eras.

Besides the Constitution prohibiting Congress from regulating foreign or domestic slave trade before 1808 and a duty on states to return escaped "persons held to service", legal scholar Akhil Reed Amar argues that the college was originally advocated by slaveholders as a bulwark to prop up slavery. In the Congressional apportionment provided in the text of the Constitution with its Three-Fifths Compromise estimate, "Virginia emerged as the big winner ithmore than a quarter of the otesneeded to win an election in the first round or Washington's first presidential election in 1788" Following the 1790 United States census, the most populous state was Virginia, with 39.1% slaves, or 292,315 counted three-fifths, to yield a calculated number of 175,389 for congressional apportionment.

"The "free" state of Pennsylvania had 10% more free persons than Virginia but got 20% fewer electoral votes."Eric Foner

Eric Foner (; born February 7, 1943) is an American historian. He writes extensively on American political history, the history of freedom, the early history of the Republican Party, African American biography, the American Civil War, Reconstr ...

agrees the Constitution's Three-Fifths Compromise gave protection to slavery.

Supporters of the College have provided many counterarguments to the charges that it defended slavery. Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

, the president who helped abolish slavery, won a College majority in 1860

Events

January

* January 2 – The astronomer Urbain Le Verrier announces the discovery of a hypothetical planet Vulcan (hypothetical planet), Vulcan at a meeting of the French Academy of Sciences in Paris, France.

* January 10 &ndas ...

despite winning 39.8% of citizen's votes. This, however, was a clear plurality of a popular vote divided among four main candidates.

Benner notes that Jefferson's first margin of victory would have been wider had the entire slave population been counted on a ''per capita'' basis.Gouverneur Morris

Gouverneur Morris ( ; January 31, 1752 – November 6, 1816) was an American statesman, a Founding Father of the United States, and a signatory to the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution. He wrote the Preamble to the ...

of Pennsylvania, who declared that such a system would lead to a "great evil of cabal and corruption," and Elbridge Gerry

Elbridge Gerry ( ; July 17, 1744 – November 23, 1814) was an American Founding Father, merchant, politician, and diplomat who served as the fifth vice president of the United States under President James Madison from 1813 until his death i ...

of Massachusetts, who called a national popular vote "radically vicious".Roger Sherman

Roger Sherman (April 19, 1721 – July 23, 1793) was an early American politician, lawyer, and a Founding Father of the United States. He is the only person to sign all four great state papers of the United States: the Continental Association, ...

of Connecticut, a state which had adopted a gradual emancipation law three years earlier, also criticized a national popular vote.[ Of like view was Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, a member of Adams' ]Federalist Party

The Federalist Party was a conservativeMultiple sources:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* and nationalist American political party and the first political party in the United States. It dominated the national government under Alexander Hamilton from 17 ...

, presidential candidate in 1800. He hailed from South Carolina and was a slaveholder.[ In ]1824

Events

January–March

* January 1 – John Stuart Mill begins publication of The Westminster Review. The first article is by William Johnson Fox

* January 8 – After much controversy, Michael Faraday is finally elected as a member of th ...

, Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

, a slaveholder from Tennessee, was similarly defeated by John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diploma ...

, a strong critic of slavery.[

]

Fourteenth Amendment

Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment requires a state's representation in the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

to be reduced if the state denies the right to vote to any male citizen aged 21 or older, unless on the basis of "participation in rebellion, or other crime". The reduction is to be proportionate to such people denied a vote. This amendment refers to "the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice President of the United States" (among other elections). It is the only part of the Constitution currently alluding to electors being selected by popular vote.

On May 8, 1866, during a debate on the Fourteenth Amendment, Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was an American politician and lawyer who served as a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, being one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Histo ...

, the leader of the Republicans in the House of Representatives, delivered a speech on the amendment's intent. Regarding Section 2, he said:

Federal law () implements Section 2's mandate.

Meeting of electors

Article II, Section 1, Clause 4 of the Constitution authorizes Congress to fix the day on which the electors shall vote, which must be the same day throughout the United States. And both Article II, Section 1, Clause 3 and the Twelfth Amendment that replaced it specifies that "the President of the Senate shall, in the presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the certificates and the votes shall then be counted."

In 1887, Congress passed the

Article II, Section 1, Clause 4 of the Constitution authorizes Congress to fix the day on which the electors shall vote, which must be the same day throughout the United States. And both Article II, Section 1, Clause 3 and the Twelfth Amendment that replaced it specifies that "the President of the Senate shall, in the presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the certificates and the votes shall then be counted."

In 1887, Congress passed the Electoral Count Act

The Electoral Count Act of 1887 (ECA) (, later codified at Title 3 of the United States Code, Title 3, Chapter 1) is a United States federal law that added to procedures set out in the Constitution of the United States for the counting of Uni ...

, now codified in Title 3, Chapter 1 of the United States Code, establishing specific procedures for the counting of the electoral votes. The law was passed in response to the disputed 1876 presidential election, in which several states submitted competing slates of electors. Among its provisions, the law established deadlines that the states must meet when selecting their electors, resolving disputes, and when they must cast their electoral votes.[

From 1948 to 2022, the date fixed by Congress for the meeting of the Electoral College was "on the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December next following their appointment". As of 2022, with the passing of "S.4573 - Electoral Count Reform and Presidential Transition Improvement Act of 2022", this was changed to be "on the first Tuesday after the second Wednesday in December next following their appointment".]Office of the Federal Register

The Office of the Federal Register is an office of the United States government within the National Archives and Records Administration.

The Office publishes the ''Federal Register'', ''Code of Federal Regulations'', '' Public Papers of the Presi ...

is charged with administering the Electoral College.contingent election

In the United States, a contingent election is used to elect the president or vice president if no candidate receives a majority of the whole number of electors appointed. A presidential contingent election is decided by a special vote of th ...

.

Modern mechanics

Summary

Even though the aggregate national popular vote is calculated by state officials, media organizations, and the Federal Election Commission

The Federal Election Commission (FEC) is an independent agency of the United States government that enforces U.S. campaign finance laws and oversees U.S. federal elections. Created in 1974 through amendments to the Federal Election Campaign ...

, the people only indirectly elect

An indirect election or ''hierarchical voting,'' is an election in which voters do not choose directly among candidates or parties for an office ( direct voting system), but elect people who in turn choose candidates or parties. It is one of the o ...

the president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

and vice president

A vice president or vice-president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vi ...

. The president and vice president of the United States are elected by the Electoral College, which consists of 538 electors from the fifty states and Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

Electors are selected state-by-state, as determined by the laws of each state. Since the 1824 election, the majority of states have chosen their presidential electors based on winner-take-all results in the statewide popular vote on Election Day.Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

and Nebraska

Nebraska ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Ka ...

are exceptions as both use the congressional district method, Maine since 1972 and in Nebraska since 1992.ballot

A ballot is a device used to cast votes in an election and may be found as a piece of paper or a small ball used in voting. It was originally a small ball (see blackballing) used to record decisions made by voters in Italy around the 16th cent ...

s list the names of the presidential and vice presidential candidates (who run on a ticket). The slate of electors that represent the winning ticket will vote for those two offices. Electors are nominated by the party and, usually, they vote for the ticket to which are promised.

Many states require an elector to vote for the candidate to which the elector is pledged, but some "faithless electors" have voted for other candidates or refrained from voting. A candidate must receive an absolute majority

A majority is more than half of a total; however, the term is commonly used with other meanings, as explained in the " Related terms" section below.

It is a subset of a set consisting of more than half of the set's elements. For example, if a gr ...

of electoral votes (currently 270) to win the presidency or the vice presidency. If no candidate receives a majority in the election for president or vice president, the election is determined via a contingency procedure established by the Twelfth Amendment. In such a situation, the House chooses one of the top three presidential electoral vote winners as the president, while the Senate chooses one of the top two vice presidential electoral vote winners as vice president.

Electors

Apportionment

A state's number of electors equals the number of representatives plus two electors for the senators the state has in the

A state's number of electors equals the number of representatives plus two electors for the senators the state has in the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

. Each state is entitled to at least one representative, the remaining number of representatives per state is apportioned based on their respective populations, determined every ten years by the United States census

The United States census (plural censuses or census) is a census that is legally mandated by the Constitution of the United States. It takes place every ten years. The first census after the American Revolution was taken in 1790 United States ce ...

. In summary, 153 electors are divided equally among the states and the District of Columbia (3 each), and the remaining 385 are assigned by an apportionment among states.

Under the Twenty-third Amendment, Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, is allocated as many electors as it would have if it were a state but no more electors than the least populous state. Because the least populous state (Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States, Western United States. It borders Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho t ...

, in the 2020 census) has three electors, D.C. cannot have more than three electors. Even if D.C. were a state, its population would entitle it to only three electors. Based on its population per electoral vote, D.C. has the third highest per capita Electoral College representation, after Wyoming and Vermont.

Currently, there are 538 electors, based on 435 representatives, 100 senators from the fifty states and three electors from Washington, D.C. The six states with the most electors are California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

(54), Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

(40), Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

(30), New York (28), Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

(19), and Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

(19). The District of Columbia and the six least populous states—Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

, Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

, North Dakota

North Dakota ( ) is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the indigenous Dakota people, Dakota and Sioux peoples. It is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north and by the U.S. states of Minneso ...

, South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state, state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Dakota people, Dakota Sioux ...

, Vermont

Vermont () is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, New York (state), New York to the west, and the Provinces and territories of Ca ...

, and Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States, Western United States. It borders Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho t ...

—have three electors each.

Nominations

The custom of allowing recognized political parties

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular area's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or p ...

to select a slate

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous, metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade, regional metamorphism. It is the finest-grained foliated metamorphic ro ...

of prospective electors developed early. In contemporary practice, each presidential-vice presidential ticket has an associated slate of potential electors. Then on Election Day, the voters select a ticket and thereby select the associated electors.[

Candidates for elector are nominated by state chapters of nationally oriented political parties in the months prior to Election Day. In some states, the electors are nominated by voters in primaries the same way other presidential candidates are nominated. In some states, such as ]Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

, and North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

, electors are nominated in party conventions. In Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

, the campaign committee of each candidate names their respective electoral college candidates, an attempt to discourage faithless elector

In the United States Electoral College, a faithless elector is an elector who does not vote for the candidates for U.S. President and U.S. Vice President for whom the elector had pledged to vote, and instead votes for another person for one or ...

s. Varying by state, electors may also be elected by state legislatures or appointed by the parties themselves.

Selection process

Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the Constitution requires each state legislature to determine how electors for the state are to be chosen, but it disqualifies any person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, from being an elector. Under Section3 of the Fourteenth Amendment, any person who has sworn an oath

Traditionally, an oath (from Old English, Anglo-Saxon ', also a plight) is a utterance, statement of fact or a promise taken by a Sacred, sacrality as a sign of Truth, verity. A common legal substitute for those who object to making sacred oaths ...

to support the United States Constitution in order to hold either a state or federal office, and later rebelled against the United States directly or by giving assistance to those doing so, is disqualified from being an elector. Congress may remove this disqualification by a two-thirds vote in each house.

All states currently choose presidential electors by popular vote. As of 2020, eight states name the electors on the ballot. Mostly, the "short ballot" is used. The short ballot displays the names of the candidates for president and vice president, rather than the names of prospective electors. Some states support voting for write-in candidate

A write-in candidate is a candidate whose name does not appear on the ballot but seeks election by asking voters to cast a vote for the candidate by physically writing in the person's name on the ballot. Depending on electoral law it may be poss ...

s. Those that do may require pre-registration of write-in candidacy, with designation of electors being done at that time. Since 1992, all but two states have followed the method of allocating electors by which every person named on the slate for the ticket winning the statewide popular vote are named as presidential electors.Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

and Nebraska

Nebraska ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Ka ...

are the only states not using this method.Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

previously upheld the power for a state to choose electors on the basis of congressional districts, holding that states possess plenary power

A plenary power or plenary authority is a complete and absolute power to take action on a particular issue, with no limitations. It is derived from the Latin language, Latin term .

United States

In United States constitutional law, plenary powe ...

to decide how electors are appointed in '' McPherson v. Blacker'', .

The Tuesday following the first Monday in November has been fixed as the day for holding federal elections, called the Election Day. After the election, each state prepares seven Certificates of Ascertainment, each listing the candidates for president and vice president, their pledged electors, and the total votes each candidacy received.mayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a Municipal corporation, municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilitie ...

of D.C.

Meetings

The Electoral College never meets as one body. Electors meet in their respective state capitals (electors for the District of Columbia meet within the District) on the same day (set by Congress as the Tuesday after the second Wednesday in December) at which time they cast their electoral votes on separate ballots for president and vice president.

The Electoral College never meets as one body. Electors meet in their respective state capitals (electors for the District of Columbia meet within the District) on the same day (set by Congress as the Tuesday after the second Wednesday in December) at which time they cast their electoral votes on separate ballots for president and vice president.New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

for example, the electors cast ballots by checking the name of the candidate on a pre-printed card. In North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

, the electors write the name of the candidate on a blank card. The tellers count the ballots and announce the result. The next step is the casting of the vote for vice president, which follows a similar pattern.

Under the Electoral Count Act (updated and codified in ), each state's electors must complete six certificates of vote. Each Certificate of Vote (or ''Certificate of the Vote'') must be signed by all of the electors and a certificate of ascertainment must be attached to each of the certificates of vote. Each Certificate of Vote must include the names of those who received an electoral vote for either the office of president or of vice president. The electors certify the Certificates of Vote, and copies of the certificates are then sent in the following fashion:

* One is sent by registered mail

Registered mail is a postal service in many countries which allows the sender proof of mailing via a receipt and, upon request, electronic verification that an article was delivered or that a delivery attempt was made. Depending on the country, ...

to the President of the Senate

President of the Senate is a title often given to the presiding officer of a senate. It corresponds to the Speaker (politics), speaker in some other assemblies.

The senate president often ranks high in a jurisdiction's Order of succession, succes ...

(who usually is the incumbent vice president of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest ranking office in the Executive branch of the United States government, executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks f ...

);

* Two are sent by registered mail to the Archivist of the United States;

* Two are sent to the state's secretary of state; and

* One is sent to the chief judge of the United States district court

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the United States federal judiciary, U.S. federal judiciary. There is one district court for each United States federal judicial district, federal judicial district. Each district cov ...

where those electors met.

A staff member of the president of the Senate collects the certificates of vote as they arrive and prepares them for the joint session of the Congress. The certificates are arranged—unopened—in alphabetical order and placed in two special mahogany boxes. Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

through Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

(including the District of Columbia

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and Federal district of the United States, federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from ...

) are placed in one box and Montana

Montana ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota to the east, South Dakota to the southeast, Wyoming to the south, an ...

through Wyoming