Presidential Assassination Attempts on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The assassination of James A. Garfield took place at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station in Washington, D.C., at 9:20 AM on Saturday, July 2, 1881, less than four months after he took office. As the president was arriving at the train station, writer and lawyer Charles J. Guiteau shot him twice with a .442 Webley British Bull Dog revolver; one bullet grazed the president's shoulder, and the other pierced his back. For the next eleven weeks, Garfield endured the pain and suffering from having been shot, before he died on September 19, 1881, at 10:35 PM, of complications caused by

The assassination of James A. Garfield took place at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station in Washington, D.C., at 9:20 AM on Saturday, July 2, 1881, less than four months after he took office. As the president was arriving at the train station, writer and lawyer Charles J. Guiteau shot him twice with a .442 Webley British Bull Dog revolver; one bullet grazed the president's shoulder, and the other pierced his back. For the next eleven weeks, Garfield endured the pain and suffering from having been shot, before he died on September 19, 1881, at 10:35 PM, of complications caused by

The assassination of president

The assassination of president

The assassination of United States president

The assassination of United States president

On March 30, 1981, as

On March 30, 1981, as

* January 30, 1835: Just outside the Capitol Building, a house painter named Richard Lawrence attempted to shoot President

* January 30, 1835: Just outside the Capitol Building, a house painter named Richard Lawrence attempted to shoot President

* February 15, 1933: Seventeen days before Roosevelt's first presidential inauguration, Giuseppe Zangara fired five shots at Roosevelt in

* February 15, 1933: Seventeen days before Roosevelt's first presidential inauguration, Giuseppe Zangara fired five shots at Roosevelt in

''Tri-City Herald'', December 1, 1972, accessed December 11, 2012 * November 1, 1950: Two Puerto Rican pro-independence activists, Oscar Collazo and Griselio Torresola, attempted to kill President Truman at the

* Mid-August 1974: Muharem Kurbegovic, also known as The Alphabet Bomber, said in a message that he was going to come to Washington, D.C., and throw a nerve gas bomb at President Gerald Ford, then just ten days into his presidency. Within one day, the

* Mid-August 1974: Muharem Kurbegovic, also known as The Alphabet Bomber, said in a message that he was going to come to Washington, D.C., and throw a nerve gas bomb at President Gerald Ford, then just ten days into his presidency. Within one day, the

Assassination

Assassination is the willful killing, by a sudden, secret, or planned attack, of a personespecially if prominent or important. It may be prompted by political, ideological, religious, financial, or military motives.

Assassinations are orde ...

attempts and plots on the president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

have been numerous, ranging from the early 19th century to the present day. This article lists assassinations and assassination attempts on incumbent and former presidents and presidents-elect, but not on those who had not yet been elected president. Four sitting U.S. presidents have been killed: Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

(1865

Events

January

* January 4 – The New York Stock Exchange opens its first permanent headquarters at 10-12 Broad near Wall Street, in New York City.

* January 13 – American Civil War: Second Battle of Fort Fisher – Unio ...

), James A. Garfield ( 1881), William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

( 1901), and John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

(1963

Events January

* January 1 – Bogle–Chandler case: Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation scientist Dr. Gilbert Bogle and Mrs. Margaret Chandler are found dead (presumed poisoned), in bushland near the Lane Cove ...

). Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

(1981

Events January

* January 1

** Greece enters the European Economic Community, predecessor of the European Union.

** Palau becomes a self-governing territory.

* January 6 – A funeral service is held in West Germany for Nazi Grand Admiral ...

) and Donald Trump (2024) are the only two presidents who have survived assassination attempts. Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

(1912

This year is notable for Sinking of the Titanic, the sinking of the ''Titanic'', which occurred on April 15.

In Albania, this leap year runs with only 353 days as the country achieved switching from the Julian to Gregorian Calendar by skippin ...

) and Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who is the 47th president of the United States. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 45 ...

(2024

The year saw the list of ongoing armed conflicts, continuation of major armed conflicts, including the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Myanmar civil war (2021–present), Myanmar civil war, the Sudanese civil war (2023–present), Sudane ...

) are the only two former presidents to have been injured in an assassination attempt, both while campaigning for reelection; the former lost and the latter won.

Many assassination attempts, both successful and unsuccessful, were motivated by a desire to change the policy of the American government.. Not all such attacks, however, had political reasons. Many other attackers had questionable mental stability, and a few were judged legally insane

The insanity defense, also known as the mental disorder defense, is an affirmative defense by excuse in a criminal case, arguing that the defendant is not responsible for their actions due to a psychiatric disease at the time of the criminal act ...

. Historian James W. Clarke suggests that most assassination attempters have been sane and politically motivated, whereas the Department of Justice's legal manual claims that a large majority have been insane. Some assassins, especially mentally ill ones, acted solely on their own, whereas those pursuing political agendas have more often found supporting conspirators. Most assassination plotters were arrested and punished by execution or lengthy detention in a prison or insane asylum.

The fact that the successor of a removed president is the vice president

A vice president or vice-president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vi ...

, and all vice presidents since Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

have shared the president's political party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular area's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific political ideology, ...

affiliation, may discourage such attacks, at least for policy reasons, even in times of partisan strife. The third person in line, the Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hung ...

, as outlined in the Presidential Succession Act

The United States Presidential Succession Act is a federal statute establishing the presidential line of succession. Article II, Section 1, Clause 6 of the United States Constitution authorizes Congress to enact such a statute:

Congress ha ...

, is often of the opposing party, however.

Threats of violence against the president are often made for rhetorical or humorous effect without serious intent, while ''credibly'' threatening the president of the United States has been a federal felony

A felony is traditionally considered a crime of high seriousness, whereas a misdemeanor is regarded as less serious. The term "felony" originated from English common law (from the French medieval word "''félonie''") to describe an offense that r ...

since 1917.

Presidents assassinated

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

, the 16th president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

, was the first U.S. president to be assassinated (but not the first to die in office). The assassination took place on Good Friday

Good Friday, also known as Holy Friday, Great Friday, Great and Holy Friday, or Friday of the Passion of the Lord, is a solemn Christian holy day commemorating the crucifixion of Jesus and his death at Calvary (Golgotha). It is observed during ...

, April 14, 1865, at Ford's Theatre

Ford's Theatre is a theater located in Washington, D.C., which opened in 1863. The theater is best known for being the site of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. On the night of April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth entered the theater box where ...

in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, at about 10:15 PM. The assassin, John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, assassinated United States president Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. A member of the p ...

, was a well-known actor and a Confederate sympathizer from Maryland; though he never joined the Confederate Army

The Confederate States Army (CSA), also called the Confederate army or the Southern army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fi ...

, he had contacts within the Confederate Secret Service. In 1864, Booth formulated a plan (very similar to one of Thomas N. Conrad previously authorized by the Confederacy) to kidnap Lincoln in exchange for the release of Confederate prisoners. After attending an April 11, 1865 speech in which Lincoln promoted voting rights for African Americans, Booth decided to assassinate the president instead. Learning that the president would be attending Ford's Theatre, Booth planned with co-conspirators to assassinate Lincoln at the theater. The conspiracy also included assassinating Vice President

A vice president or vice-president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vi ...

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

in Kirkwood House, where Johnson lived while Vice President, and Secretary of State William H. Seward at Seward's house. On April 14, 1865, Lincoln attended the play ''Our American Cousin

''Our American Cousin'' is a three-act play by English playwright Tom Taylor. It is a farce featuring awkward, boorish American Asa Trenchard, who is introduced to his aristocratic English relatives when he goes to England to claim the family e ...

'' at Ford's Theatre

Ford's Theatre is a theater located in Washington, D.C., which opened in 1863. The theater is best known for being the site of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. On the night of April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth entered the theater box where ...

. As the president sat in his state box in the balcony watching the play with his wife Mary and two guests, Major Henry Rathbone and Rathbone's fiancée Clara Harris

Clara Hamilton Harris (September 9, 1834 – December 25, 1883) was an American socialite. She and her then fiancé, and future husband, Henry Rathbone, were the guests of President Abraham Lincoln the night he was shot at Ford's Theat ...

, Booth entered the box and shot Lincoln in the back of the head, with a .44-caliber Derringer pistol, mortally wounding him and rendering him unconscious immediately. Booth stabbed Rathbone as Rathbone came at him, and escaped also stabbing orchestra leader William Withers Jr.. Lincoln was taken across the street to the Petersen House

The Petersen House is a 19th-century Federal architecture, federal style row house in the United States in Washington, D.C., located at 516 10th Street NW, several blocks east of the White House. It is known for being the house where President o ...

, where he remained in a coma

A coma is a deep state of prolonged unconsciousness in which a person cannot be awakened, fails to Nociception, respond normally to Pain, painful stimuli, light, or sound, lacks a normal Circadian rhythm, sleep-wake cycle and does not initiate ...

for nine hours, before he died at 7:22 AM on April 15. Lincoln was succeeded by Vice President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. The 16th vice president, he assumed the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a South ...

.

Beyond Lincoln's death, the plot failed: Seward was only wounded, and Johnson's would-be attacker did not follow through. After being on the run for 12 days, Booth was tracked down and found on April 26, 1865, by Union Army soldiers at a farm in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

, some south of Washington. After refusing to surrender, Booth was shot and mortally wounded by Union cavalryman Boston Corbett. Eight other conspirators were later convicted for their roles in the conspiracy; four were hanged and four received life sentences.

James A. Garfield

The assassination of James A. Garfield took place at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station in Washington, D.C., at 9:20 AM on Saturday, July 2, 1881, less than four months after he took office. As the president was arriving at the train station, writer and lawyer Charles J. Guiteau shot him twice with a .442 Webley British Bull Dog revolver; one bullet grazed the president's shoulder, and the other pierced his back. For the next eleven weeks, Garfield endured the pain and suffering from having been shot, before he died on September 19, 1881, at 10:35 PM, of complications caused by

The assassination of James A. Garfield took place at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station in Washington, D.C., at 9:20 AM on Saturday, July 2, 1881, less than four months after he took office. As the president was arriving at the train station, writer and lawyer Charles J. Guiteau shot him twice with a .442 Webley British Bull Dog revolver; one bullet grazed the president's shoulder, and the other pierced his back. For the next eleven weeks, Garfield endured the pain and suffering from having been shot, before he died on September 19, 1881, at 10:35 PM, of complications caused by iatrogenic infections

Iatrogenesis is the causation of a disease, a harmful complication, or other ill effect by any medical activity, including diagnosis, intervention, error, or negligence."mwod:iatrogenic, Iatrogenic", ''Merriam-Webster.com'', Merriam-Webster, I ...

, which were contracted by the doctors' relentless probing of his wound with unsterilized fingers and instruments; he had survived for a total of 79 days after being shot. Garfield was succeeded by Vice President Chester A. Arthur.

Guiteau was immediately arrested. After a highly publicized trial lasting from November 14, 1881, to January 25, 1882, he was found guilty and sentenced to death. A subsequent appeal was rejected, and he was executed by hanging

Hanging is killing a person by suspending them from the neck with a noose or ligature strangulation, ligature. Hanging has been a standard method of capital punishment since the Middle Ages, and has been the primary execution method in numerou ...

on June 30, 1882, in the District of Columbia

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and Federal district of the United States, federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from ...

. Guiteau was assessed during his trial and autopsy as mentally unbalanced or suffering from the effects of neurosyphilis

Neurosyphilis is the infection of the central nervous system by '' Treponema pallidum'', the bacterium that causes the sexually transmitted infection syphilis. In the era of modern antibiotics, the majority of neurosyphilis cases have been report ...

. He claimed to have shot Garfield out of disappointment at being passed over for appointment as Ambassador to France. He attributed the president's victory in the election to a speech he wrote in support of Garfield.

William McKinley

The assassination of president

The assassination of president William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

took place at 4:07 PM on Friday, September 6, 1901, at the Temple of Music in Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is a Administrative divisions of New York (state), city in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York and county seat of Erie County, New York, Erie County. It lies in Western New York at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of ...

. McKinley, attending the Pan-American Exposition

The Pan-American Exposition was a world's fair held in Buffalo, New York, United States, from May 1 through November 2, 1901. The fair occupied of land on the western edge of what is now Delaware Park–Front Park System, Delaware Park, extending ...

, was shot twice in the abdomen at close range by Leon Czolgosz

Leon Frank Czolgosz ( ; ; May 5, 1873 – October 29, 1901) was an American wireworker and Anarchism, anarchist who assassination of William McKinley, assassinated President of the United States, United States president William McKinley on Septe ...

, an anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

, who was armed with a .32-caliber Iver Johnson "Safety Automatic" revolver

A revolver is a repeating handgun with at least one barrel and a revolving cylinder containing multiple chambers (each holding a single cartridge) for firing. Because most revolver models hold six cartridges before needing to be reloaded, ...

that was concealed underneath a handkerchief; the first bullet ricocheted off either a button or an award medal on McKinley's jacket and lodged in his sleeve; the second shot pierced his stomach. James Benjamin Parker, who had been standing behind the assassin in line, was the first to grab Czolgosz and the revolver. Other individuals jumped in and the group subdued Czolgosz before he could fire a third shot. They beat Czolgosz severely until McKinley was able to order the beating to stop. Although McKinley initially appeared to be recovering in the week after, his condition rapidly declined due to gangrene

Gangrene is a type of tissue death caused by a lack of blood supply. Symptoms may include a change in skin color to red or black, numbness, swelling, pain, skin breakdown, and coolness. The feet and hands are most commonly affected. If the ga ...

setting in around his wounds and he died on September 14, 1901, at 2:15 AM. McKinley was succeeded by Vice President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

.

On September 24, after a two-day trial, in which the defendant refused to defend himself, Czolgosz was convicted and later sentenced to death. He was executed by the electric chair

The electric chair is a specialized device used for capital punishment through electrocution. The condemned is strapped to a custom wooden chair and electrocuted via electrodes attached to the head and leg. Alfred P. Southwick, a Buffalo, New Yo ...

in Auburn Prison on October 29, 1901. Czolgosz's actions were politically motivated, although it remains unclear what outcome, if any, he believed the shooting would yield.

Following President McKinley's assassination, Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

directed the Secret Service

A secret service is a government agency, intelligence agency, or the activities of a government agency, concerned with the gathering of intelligence data. The tasks and powers of a secret service can vary greatly from one country to another. For i ...

to protect the president of the United States as part of its mandate.

John F. Kennedy

The assassination of United States president

The assassination of United States president John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

took place at 12:30 PM on Friday, November 22, 1963, in Dallas, Texas

Dallas () is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the most populous city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the List of Texas metropolitan areas, most populous metropolitan area in Texas and the Metropolitan statistical area, fourth-most ...

, during a presidential motorcade

A motorcade, or autocade, is a procession of motor vehicles. Uses can include ceremonial processions for funerals or demonstrations, but can also be used to provide security while transporting a very important person. The American presidenti ...

in Dealey Plaza. Kennedy was riding with his wife Jacqueline, Texas Governor John Connally

John Bowden Connally Jr. (February 27, 1917June 15, 1993) was an American politician who served as the 39th governor of Texas from 1963 to 1969 and as the 61st United States secretary of the treasury from 1971 to 1972. He began his career as a Hi ...

, and Connally's wife Nellie when he was fatally shot; he was hit once in the back, the bullet

A bullet is a kinetic projectile, a component of firearm ammunition that is shot from a gun barrel. They are made of a variety of materials, such as copper, lead, steel, polymer, rubber and even wax; and are made in various shapes and constru ...

exiting via his throat, and once in the head. Governor Connally was seriously wounded, and bystander James Tague received a minor facial injury from a small piece of curbstone that had fragmented after it was struck by one of the bullets. The motorcade rushed to Parkland Memorial Hospital, where Kennedy was declared dead at 1:00 PM. Kennedy was succeeded by Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

.

After a 6.5×52mm Carcano Model 38 rifle

A rifle is a long gun, long-barreled firearm designed for accurate shooting and higher stopping power, with a gun barrel, barrel that has a helical or spiralling pattern of grooves (rifling) cut into the bore wall. In keeping with their focus o ...

was found on the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository

The Texas School Book Depository, later known as the Dallas County Administration Building and now "The Sixth Floor Museum", is a seven-floor building facing Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas. The building was Lee Harvey Oswald's vantage point du ...

, depository worker Lee Harvey Oswald

Lee Harvey Oswald (October 18, 1939 – November 24, 1963) was a U.S. Marine veteran who assassinated John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, on November 22, 1963.

Oswald was placed in juvenile detention at age 12 for truan ...

, a former U.S. Marine

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines or simply the Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is responsible for conducting expeditionar ...

and American defector was arrested and charged by the Dallas Police Department

The Dallas Police Department, established in 1881, is the principal law enforcement agency serving the city of Dallas, Texas.

Organization

The department is headed by a chief of police who is appointed by the city manager who, in turn, is hir ...

for the assassination and for the murder of Dallas policeman J. D. Tippit, who was shot dead in a residential neighborhood in the Oak Cliff

Oak Cliff is an area of Dallas, Texas, United States that was formerly a separate town in Dallas County; established in 1887 and annexed by Dallas in 1903, Oak Cliff has retained a distinct neighborhood identity as one of Dallas' older establ ...

section of Dallas less than an hour after the assassination. On Sunday, November 24, while being transferred from the city jail to the county jail, Oswald was shot and mortally wounded in the basement of Dallas Police Department

The Dallas Police Department, established in 1881, is the principal law enforcement agency serving the city of Dallas, Texas.

Organization

The department is headed by a chief of police who is appointed by the city manager who, in turn, is hir ...

Headquarters by Dallas nightclub owner Jack Ruby

Jack Leon Ruby (born Jacob Leon Rubenstein; March 25, 1911January 3, 1967) was an American nightclub owner who murdered Lee Harvey Oswald on November 24, 1963, two days after Oswald assassinated President John F. Kennedy.

Born in Chicago, R ...

. Oswald died at Parkland Hospital. Ruby was convicted of Oswald's murder, albeit his conviction was later overturned on appeal. He died in 1967 while awaiting a new trial, his motivation remains unknown.

In 1964, the Warren Commission

The President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, known unofficially as the Warren Commission, was established by President of the United States, President Lyndon B. Johnson through on November 29, 1963, to investigate the A ...

concluded that Kennedy and Tippit were killed by Oswald, that Oswald had acted entirely alone in both murders, and that Ruby had acted alone in killing Oswald. The commission's findings have been supported by some writers but also challenged by various critics who hypothesize that there was a conspiracy surrounding the Kennedy assassination.

Incumbent presidents wounded

Ronald Reagan

On March 30, 1981, as

On March 30, 1981, as Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

was returning to his limousine

A limousine ( or ), or limo () for short, is a large, chauffeur-driven luxury vehicle with a partition between the driver compartment and the passenger compartment which can be operated mechanically by hand or by a button electronically. A luxu ...

after speaking at the Washington Hilton hotel, John Hinckley Jr. fired six shots from a .22 caliber Röhm RG-14 revolver

A revolver is a repeating handgun with at least one barrel and a revolving cylinder containing multiple chambers (each holding a single cartridge) for firing. Because most revolver models hold six cartridges before needing to be reloaded, ...

. Reagan was seriously wounded when one bullet ricocheted off the side of the presidential limousine and hit him in the left underarm, breaking a rib, puncturing a lung, and causing serious internal bleeding

Internal bleeding (also called internal haemorrhage) is a loss of blood from a blood vessel that collects inside the body, and is not usually visible from the outside. It can be a serious medical emergency but the extent of severity depends on b ...

. Although "close to death" upon arrival at George Washington University Hospital, Reagan was stabilized in the emergency room, and then underwent emergency exploratory surgery. He was released from the hospital on April 11. Besides Reagan, White House press secretary

The White House press secretary is a senior White House official whose primary responsibility is to act as spokesperson for the executive branch of the United States federal government, especially with regard to the president, senior aides and ...

James Brady, Secret Service agent Tim McCarthy

Timothy J. McCarthy (born June 20, 1949) is an American retired police officer and special agent of the U.S. Secret Service. He is best known for defending then-president Ronald Reagan during the assassination attempt on Reagan's life on Marc ...

, and police officer Thomas Delahanty were also wounded. All three survived, but Brady suffered brain damage and was permanently disabled; Brady died in 2014 as a result of his injuries.

Hinckley was immediately arrested, and said he had wanted to kill Reagan to impress actress Jodie Foster

Alicia Christian "Jodie" Foster (born November 19, 1962) is an American actress and filmmaker. Foster started her career as a child actor before establishing herself as leading actress in film. She has received List of awards and nominations re ...

. He was deemed mentally ill and confined to an institution. Hinckley was released from institutional psychiatric care on September 10, 2016.

Former presidents wounded

Theodore Roosevelt

Three-and-a-half years after he left office,Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

ran in the 1912 presidential election as a member of the Bull Moose Party

The Progressive Party, popularly nicknamed the Bull Moose Party, was a Third party (U.S. politics), third party in the United States formed in 1912 by former president Theodore Roosevelt after he lost the 1912 Republican Party presidential prim ...

. While campaigning in Milwaukee

Milwaukee is the List of cities in Wisconsin, most populous city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. Located on the western shore of Lake Michigan, it is the List of United States cities by population, 31st-most populous city in the United States ...

, Wisconsin, on October 14, 1912, John Schrank, a saloon-keeper from New York who had been stalking him for weeks, shot Roosevelt once in the chest with a .38-caliber Colt Police Positive Special. The 50-page text of his campaign speech titled " Progressive Cause Greater Than Any Individual", folded over twice in Roosevelt's breast pocket, and a metal glasses case slowed the bullet, saving his life. Schrank was immediately disarmed, captured, and might have been lynched had Roosevelt not shouted for Schrank to remain unharmed. Roosevelt assured the crowd he was all right, then ordered police to take charge of Schrank and to make sure no violence was done to him.

Roosevelt, as an experienced hunter and anatomist, correctly concluded that since he was not coughing blood, the bullet had not reached his lung, and he declined suggestions to go to the hospital immediately. Instead, he delivered his scheduled speech with blood seeping into his shirt. He spoke for 84 minutes before completing his speech and accepting medical attention. His opening comments to the gathered crowd were, "Ladies and gentlemen, I don't know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot, but it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose." Afterwards, probes and an x-ray showed that the bullet had lodged in Roosevelt's chest muscle, but did not penetrate the pulmonary pleurae

The pleurae (: pleura) are the two flattened closed sacs filled with pleural fluid, each ensheathing each lung and lining their surrounding tissues, locally appearing as two opposing layers of serous membrane separating the lungs from the medias ...

. Doctors concluded that it would be less dangerous to leave it in place than to attempt to remove it, and the bullet remained in Roosevelt's body for the remainder of his life. He spent two weeks recuperating before returning to the campaign trail. Despite his tenacity, Roosevelt ultimately lost his bid for reelection to the Democratic candidate Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

.

At Schrank's trial, the would-be assassin claimed that William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

had visited him in a dream and told him to avenge his assassination by killing Roosevelt. He was found legally insane

The insanity defense, also known as the mental disorder defense, is an affirmative defense by excuse in a criminal case, arguing that the defendant is not responsible for their actions due to a psychiatric disease at the time of the criminal act ...

and was institutionalized until his death in 1943.

Donald Trump

On July 13, 2024, then former presidentDonald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who is the 47th president of the United States. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 45 ...

, and the Republican Party's presumptive nominee

Preselection is the process by which a candidate is selected, usually by a political party, to contest an election for political office. It is also referred to as candidate selection. It is a fundamental function of political parties. The presel ...

in the presidential election that year, was shot at while addressing a campaign rally

A political campaign is an organized effort which seeks to influence the decision making progress within a specific group. In democracies, political campaigns often refer to electoral campaigns, by which representatives are chosen or referen ...

near Butler, Pennsylvania

Butler is a city in Butler County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. It is north of Pittsburgh and part of the Greater Pittsburgh region. As of the 2020 census, the population was 13,502.

Butler is named after Major General ...

. Shortly after Trump began addressing the rally, 20-year-old Thomas Matthew Crooks fired eight rounds with an AR-15–style rifle from the roof of a building located around from the stage. Crooks also killed audience member Corey Comperatore and critically injured two other audience members. Crooks was shot and killed by the U.S. Secret Service's counter-sniper team. Trump was hit by a bullet wounding his right ear and he took cover on the floor of the podium, where he was shielded by Secret Service personnel. After agents helped him to his feet, Trump emerged with blood on his ear and face. He then either mouthed or shouted the words "Fight! Fight! Fight!" The images of a bloodied Trump pumping his fist in the air, with an American flag

The national flag of the United States, often referred to as the American flag or the U.S. flag, consists of thirteen horizontal Bar (heraldry), stripes, Variation of the field, alternating red and white, with a blue rectangle in the Canton ( ...

in the background, were widely praised as iconic and historically significant. Trump was escorted off-stage and taken to a nearby hospital before being released in stable condition a few hours later. He would later go on to win the election.

, an investigation by the FBI has been underway. Crooks's motivation remains unknown.

Other attacks, assassination attempts, and plots

Andrew Jackson

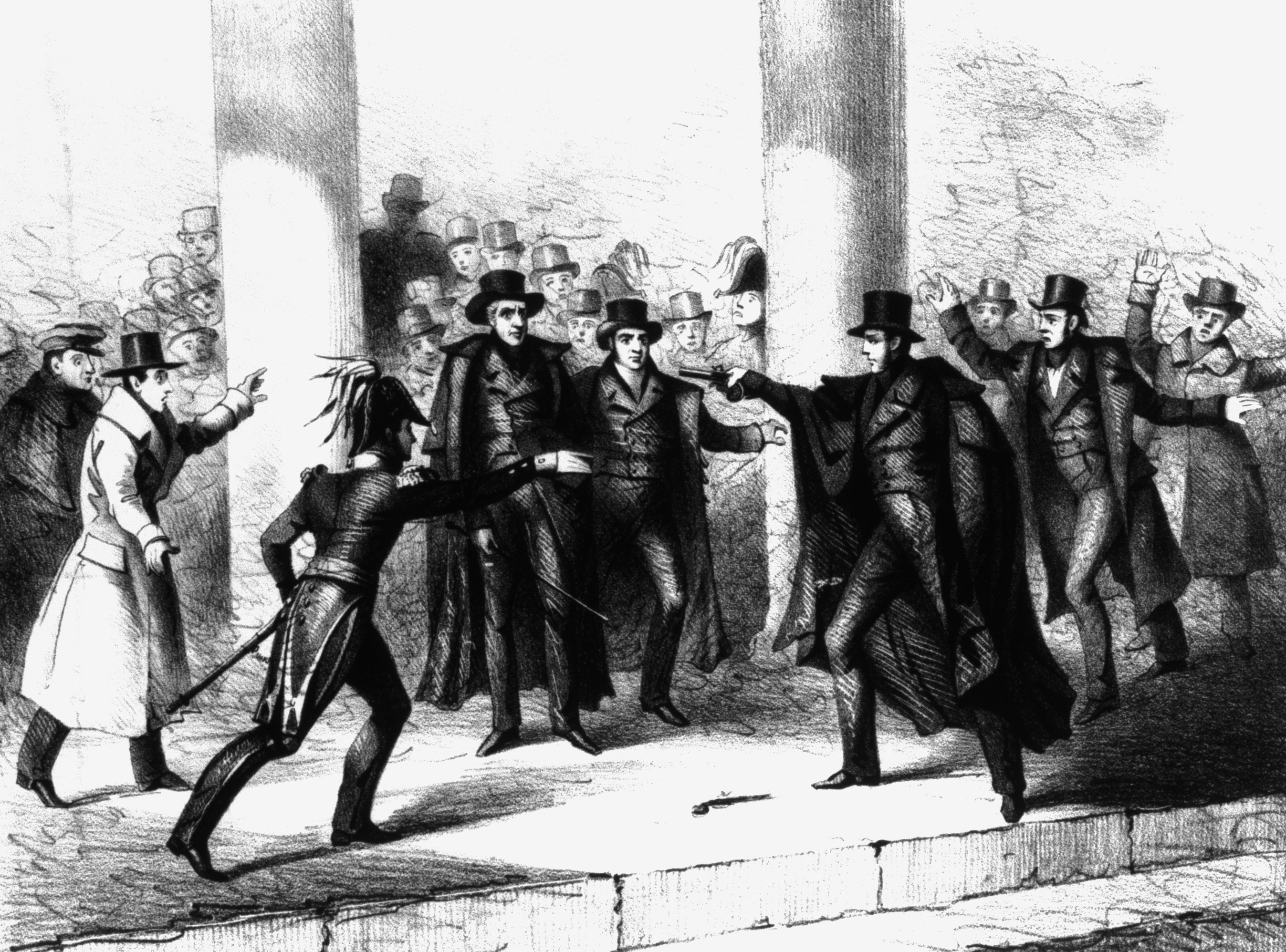

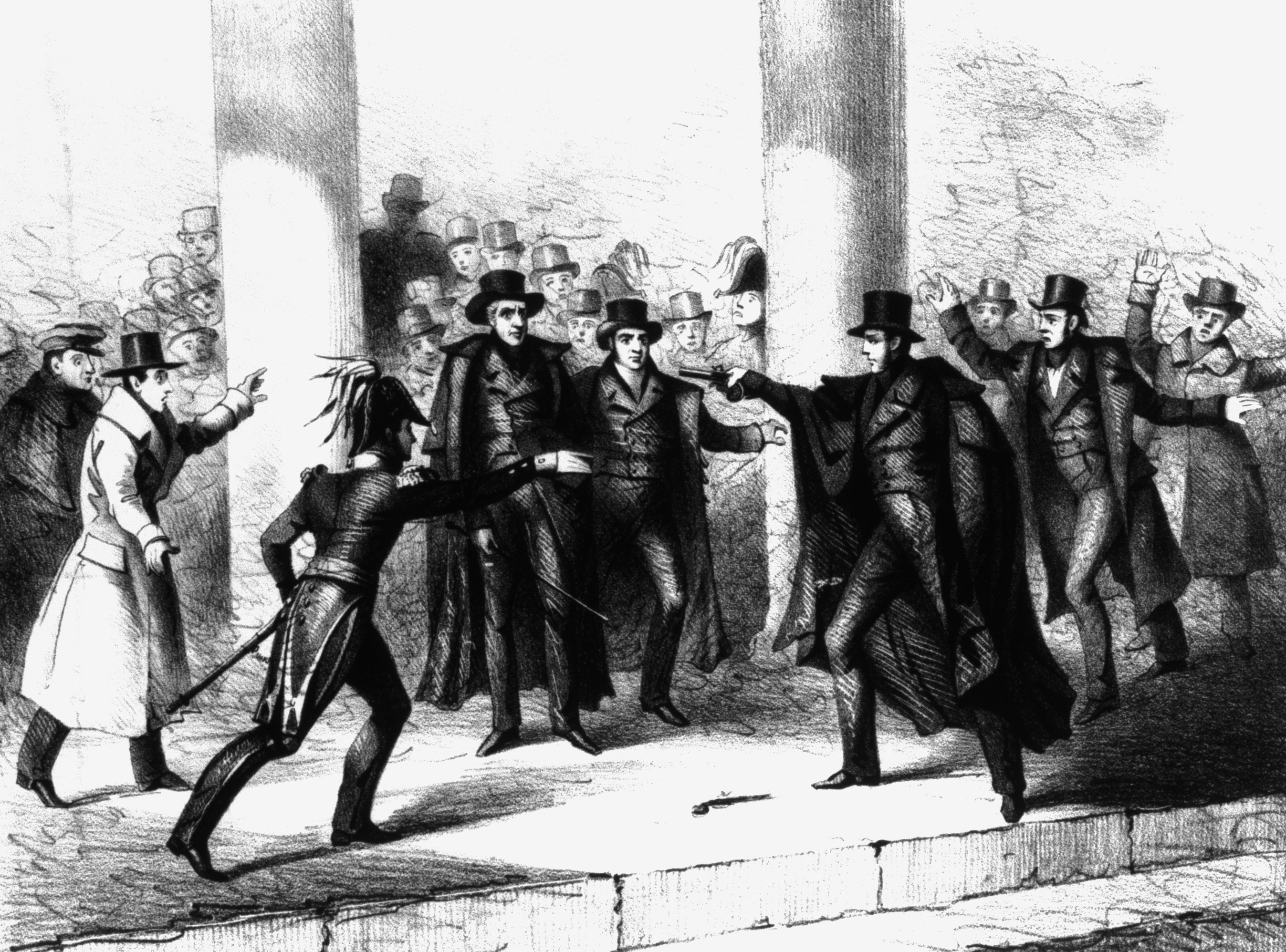

* January 30, 1835: Just outside the Capitol Building, a house painter named Richard Lawrence attempted to shoot President

* January 30, 1835: Just outside the Capitol Building, a house painter named Richard Lawrence attempted to shoot President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

with two pistols, both of which misfired. Later somebody tried the two pistols and both worked fine. Lawrence was apprehended after Jackson beat him severely with his cane. Lawrence was found not guilty by reason of insanity and confined to a mental institution until his death in 1861.

Abraham Lincoln

* February 23, 1861:President-elect

An ''officer-elect'' is a person who has been elected to a position but has not yet been installed. Notably, a president who has been elected but not yet installed would be referred to as a ''president-elect'' (e.g. president-elect of the Un ...

Lincoln passed through Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the List of United States ...

amid threats of the Baltimore Plot, an alleged conspiracy by Confederate sympathizers in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

to assassinate Lincoln en route to his inauguration

In government and politics, inauguration is the process of swearing a person into office and thus making that person the incumbent. Such an inauguration commonly occurs through a formal ceremony or special event, which may also include an inau ...

. Allan Pinkerton's National Detective Agency played a key role in protecting the president-elect by managing Lincoln's security throughout the journey. Although scholars debate whether the threat was real, Lincoln and his advisers took action to ensure his safe passage through Baltimore.

* December 1863: Confederate agent Godfrey Joseph Hyams claimed in 1865 that in December 1863 he had been recruited by Luke P. Blackburn into a plot to infect Northern cities with yellow fever by distributing clothes from patients infected with the disease throughout the target cities. Hyams also alleged that Blackburn had told him to deliver a batch of contaminated clothes to the White House to infect President Lincoln, but he had disobeyed this order. Unknown at the time was the fact that yellow fever is spread by mosquito

Mosquitoes, the Culicidae, are a Family (biology), family of small Diptera, flies consisting of 3,600 species. The word ''mosquito'' (formed by ''Musca (fly), mosca'' and diminutive ''-ito'') is Spanish and Portuguese for ''little fly''. Mos ...

bites and not by touch, so any such plot was doomed to failure. Blackburn stood trial after Hyams went public with his allegations but was acquitted.

* August 1864: A lone rifle shot fired by an unknown sniper missed Lincoln's head by inches (passing through his hat) as he rode in the late evening, unguarded, north from the White House to the Soldiers' Home (his regular retreat where he would work and sleep before returning to the White House the following morning). Near 11:00 PM, Private John W. Nichols of the Pennsylvania 150th Volunteers, the sentry on duty at the gated entrance to the Soldiers' Home grounds, heard the rifle shot and moments later saw the president riding toward him "bareheaded". Lincoln described the matter to Ward Lamon, his old friend and loyal bodyguard.

* April 1865: On April 1, Confederate agent Thomas F. Harney was dispatched from Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, a city in the United States

* Richmond, London, a town in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, England

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town ...

to Washington, D.C., on a mission to decapitate the United States government by killing President Lincoln and his cabinet. The plan was that Harney would blow up the White House after gaining access via a secret underground entrance. Union troops were tipped off about the plot by Confederate soldier William H. Snyder and Harney was arrested en route to Washington on April 10.

* April 11, 1865: John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, assassinated United States president Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. A member of the p ...

, who would make a successful attempt on Lincoln's life three days later, attended Lincoln's final public address in Washington, D.C., with his future co-conspirators David Herold

David Edgar Herold (June 16, 1842 – July 7, 1865) was an American pharmacist's assistant and accomplice of John Wilkes Booth in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865. After the shooting, Herold accompanied Booth to the home o ...

and Lewis Powell. During the speech, Booth became enraged when Lincoln expressed his support for granting voting rights to former slaves and ordered Powell to shoot Lincoln. Powell ultimately decided against it for fear of the crowd, but Booth vowed to "put him through" and formulated a plan to kill Lincoln which came to fruition on April 14.

William Howard Taft

* 1909:William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

and Porfirio Díaz

José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori (; ; 15 September 1830 – 2 July 1915) was a General (Mexico), Mexican general and politician who was the dictator of Mexico from 1876 until Mexican Revolution, his overthrow in 1911 seizing power in a Plan ...

planned a summit in El Paso

El Paso (; ; or ) is a city in and the county seat of El Paso County, Texas, United States. The 2020 United States census, 2020 population of the city from the United States Census Bureau, U.S. Census Bureau was 678,815, making it the List of ...

, Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

, and Ciudad Juárez

Ciudad Juárez ( , ; "Juárez City"), commonly referred to as just Juárez (Lipan language, Lipan: ''Tsé Táhú'ayá''), is the most populous city in the Administrative divisions of Mexico, Mexican state of Chihuahua (state), Chihuahua. It was k ...

, Chihuahua, a historic first meeting between a U.S. president and a Mexican president and also the first time an American president would cross the border into Mexico. Díaz requested the meeting to show U.S. support for his planned eighth run as president, and Taft agreed to support Díaz in order to protect the several billion dollars of American capital then invested in Mexico. Both sides agreed that the disputed Chamizal strip connecting El Paso to Ciudad Juárez would be considered neutral territory with no flags present during the summit, but the meeting focused attention on this territory and resulted in assassination threats and other serious security concerns. The Texas Rangers, 4,000 U.S.

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 contiguous ...

and Mexican troops, U.S. Secret Service agents, FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

agents, and U.S. Marshals were all called in to provide security. An additional 250-member private security detail led by Frederick Russell Burnham

Major (rank), Major Frederick Russell Burnham Distinguished Service Order, DSO (May 11, 1861 – September 1, 1947) was an American scout and world-traveling adventurer. He is known for his service to the British South Africa Company and to t ...

, the celebrated scout, was hired by John Hays Hammond

John Hays Hammond (March 31, 1855 – June 8, 1936) was an American mining engineer, diplomat, and philanthropist. He amassed a sizable fortune before the age of 40. An early advocate of deep mining, Hammond was given complete charge of Cecil R ...

. Hammond was a close friend of Taft from Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

and a former candidate for U.S. vice president in the 1908 presidential election who, along with his business partner Burnham, held considerable mining interests in Mexico. On October 16, the day of the summit, Burnham and Private C.R. Moore, a Texas Ranger, discovered 52-year-old Julius Bergerson holding a concealed palm pistol standing at the El Paso Chamber of Commerce building along the procession route. Burnham and Moore captured and disarmed Bergerson within only a few feet (around one meter) of Taft and Díaz.

* 1910: President Taft visited his aunt, Delia Torrey, in Millbury, Massachusetts. Torrey later reported receiving a stranger who allegedly overheard an assassination plot in Boston, Massachusetts

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

. Before leaving nearby Worcester, Massachusetts

Worcester ( , ) is the List of municipalities in Massachusetts, second-most populous city in the U.S. state of Massachusetts and the list of United States cities by population, 113th most populous city in the United States. Named after Worcester ...

by train, he threatened Torrey, who claimed the stranger "did not want anything to get into the papers, and if it did he would come back and kill me." Torrey reported the plot to the local police, who shared the allegation with the Worcester Police and the Secret Service. The man was never identified.

Herbert Hoover

* November 19, 1928: President-elect Hoover embarked on a ten-nation "goodwill tour" of Central and South America. While he was crossing theAndes Mountains

The Andes ( ), Andes Mountains or Andean Mountain Range (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long and wide (widest between 18°S ...

from Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

, an assassination plot by Argentine

Argentines, Argentinians or Argentineans are people from Argentina. This connection may be residential, legal, historical, or cultural. For most Argentines, several (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their ...

anarchists was thwarted. The group was led by Severino Di Giovanni, who planned to blow up his train as it crossed the Argentinian central plain. The plotters had an itinerary but the bomber was arrested before he could place the explosives on the rails. Hoover professed unconcern, tearing off the front page of a newspaper that revealed the plot and explaining, "It's just as well that Lou shouldn't see it," referring to his wife. His complimentary remarks on Argentina were well received in both the host country and in the press.

Franklin D. Roosevelt

* February 15, 1933: Seventeen days before Roosevelt's first presidential inauguration, Giuseppe Zangara fired five shots at Roosevelt in

* February 15, 1933: Seventeen days before Roosevelt's first presidential inauguration, Giuseppe Zangara fired five shots at Roosevelt in Miami

Miami is a East Coast of the United States, coastal city in the U.S. state of Florida and the county seat of Miami-Dade County, Florida, Miami-Dade County in South Florida. It is the core of the Miami metropolitan area, which, with a populat ...

, Florida. Zangara's shots missed the president-elect, but Zangara did mortally wound Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

Mayor Anton Cermak

Anton Joseph Cermak (May 9, 1873 – March 6, 1933) was an American politician who served as the 44th Mayor of Chicago from April 7, 1931, until his death in 1933. He was killed by Giuseppe Zangara, whose likely target was President-elec ...

and injured four other people. Zangara pleaded guilty to the murder of Cermak and was executed in the electric chair on March 20, 1933. It has never been conclusively determined who was Zangara's target, but most assumed at first that he had been shooting at the president-elect. Another theory is that the attempt may have been ordered by the imprisoned Al Capone

Alphonse Gabriel Capone ( ; ; January 17, 1899 – January 25, 1947), sometimes known by the nickname "Scarface", was an American organized crime, gangster and businessman who attained notoriety during the Prohibition era as the co-foun ...

, and that Cermak, who had led a crackdown on the Chicago Outfit

The Chicago Outfit, also known as the Outfit, the Chicago Mafia, the Chicago Mob, the Chicago crime family, the South Side Gang or the Organization, is an Italian Americans, Italian American American Mafia, Mafia crime family based in Chicago, I ...

and Chicago organized crime more generally, was the true target.

* 1943: Soviet NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (, ), abbreviated as NKVD (; ), was the interior ministry and secret police of the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946. The agency was formed to succeed the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) se ...

claimed to have discovered a Nazi German

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictat ...

Waffen-SS

The (; ) was the military branch, combat branch of the Nazi Party's paramilitary ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscr ...

plan to assassinate Roosevelt, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, and Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

at the Tehran Conference

The Tehran Conference (codenamed Eureka) was a strategy meeting of the Allies of World War II, held between Joseph Stalin, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill from 28 November to 1 December 1943. It was the first of the Allied World Wa ...

.

Harry S. Truman

* Mid-1947: During the Jewish insurgency in Palestine before the formation of theState of Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

, the Zionist paramilitary organization Lehi was alleged to have sent a number of letter bombs addressed to the president and high-ranking staff at the White House. At the time, the incident was not publicized, but Truman's daughter Margaret Truman

Mary Margaret Truman Daniel (February 17, 1924 – January 29, 2008) was an American classical soprano, actress, journalist, radio and television personality, writer, and New York socialite. She was the only child of President Harry S. Truman a ...

disclosed the alleged incident in her biography of Truman published in 1972; the allegation was previously disclosed in a memoir by Ira R. T. Smith, who worked in the mail room. According to Truman, the Secret Service was alerted by British intelligence after similar letters had been sent to high-ranking British officials and Lehi claimed credit; the mail room of the White House intercepted the letters intended for President Truman and the Secret Service defused them.AP, "Jews Sent Truman Letter Bombs, Book Tells"''Tri-City Herald'', December 1, 1972, accessed December 11, 2012 * November 1, 1950: Two Puerto Rican pro-independence activists, Oscar Collazo and Griselio Torresola, attempted to kill President Truman at the

Blair House

Blair House, also known as The President's Guest House, is an official residence in Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States. The President's Guest House has been called "the world's most exclusive hotel" because it is primarily used ...

, where Truman was living while the White House was undergoing major renovations. In the attack, Torresola injured White House policeman Joseph Downs and mortally wounded White House policeman Leslie Coffelt. Coffelt returned fire, killing Torresola with a shot to the head. Collazo wounded an officer before being shot in the stomach. Collazo survived with serious injuries; Coffelt died of his wounds 4 hours later in a hospital. Truman was not harmed, but he was placed at a huge risk. Collazo was convicted in a federal trial and received the death sentence. Truman commuted Collazo's death sentence to life in prison. In 1979, President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

further commuted Collazo's sentence to time served.

John F. Kennedy

* December 11, 1960: While vacationing inPalm Beach, Florida

Palm Beach is an incorporated town in Palm Beach County, Florida, United States. Located on a barrier island in east-central Palm Beach County, the town is separated from West Palm Beach, Florida, West Palm Beach and Lake Worth Beach, Florida, ...

, President-elect John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

was threatened by Richard Paul Pavlick, a 73-year-old former postal worker driven by hatred of Catholics. Pavlick intended to crash his dynamite

Dynamite is an explosive made of nitroglycerin, sorbents (such as powdered shells or clay), and Stabilizer (chemistry), stabilizers. It was invented by the Swedish people, Swedish chemist and engineer Alfred Nobel in Geesthacht, Northern German ...

-laden 1950 Buick

Buick () is a division (business), division of the Automotive industry in the United States, American automobile manufacturer General Motors (GM). Started by automotive pioneer David Dunbar Buick in 1899, it was among the first American automobil ...

into Kennedy's vehicle, but he changed his mind after seeing Kennedy's wife and daughter bid him goodbye. Pavlick was arrested four days later by the Secret Service after being stopped for a driving violation; police found the dynamite in his car and arrested him. On January 27, 1961, Pavlick was committed to the United States Public Health Service

The United States Public Health Service (USPHS or PHS) is a collection of agencies of the Department of Health and Human Services which manages public health, containing nine out of the department's twelve operating divisions. The assistant s ...

mental hospital in Springfield, Missouri

Springfield is the List of cities in Missouri, third most populous city in the U.S. state of Missouri and the county seat of Greene County, Missouri, Greene County. The city's population was 169,176 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 censu ...

, then was indicted for threatening Kennedy's life seven weeks later. Charges against Pavlick were dropped on December 2, 1963, ten days after Kennedy's assassination in Dallas. Judge Emett Clay Choate ruled that Pavlick was unable to distinguish between right and wrong in his actions, but kept him in the mental hospital. The federal government also dropped charges in August 1964, and Pavlick was eventually released from the New Hampshire State Hospital

The New Hampshire State Hospital was originally constructed in 1842 in Concord, New Hampshire, Concord, New Hampshire, as the seventeenth mental institution in the country and the seventh in New England to cater to the state's mentally ill pop ...

on December 13, 1966.

Richard Nixon

* April 13, 1972: Arthur Bremer carried a firearm to a motorcade inOttawa

Ottawa is the capital city of Canada. It is located in the southern Ontario, southern portion of the province of Ontario, at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the cor ...

, Canada, intending to shoot Nixon, but the president's car went by too fast for Bremer to get a good shot. The next day, Bremer thought he saw Nixon's car outside of the Centre Block

The Centre Block () is the main building of the Parliament of Canada, Canadian parliamentary complex on Parliament Hill, in Ottawa, Ontario, containing the House of Commons of Canada, House of Commons and Senate of Canada, Senate chambers, as we ...

, but it had disappeared by the time he could retrieve his gun from his hotel room. A month later, Bremer instead shot and seriously injured the governor of Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

, George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who was the 45th and longest-serving governor of Alabama (1963–1967; 1971–1979; 1983–1987), and the List of longest-serving governors of U.S. s ...

, who was paralyzed

Paralysis (: paralyses; also known as plegia) is a loss of motor function in one or more muscles. Paralysis can also be accompanied by a loss of feeling (sensory loss) in the affected area if there is sensory damage. In the United States, r ...

from the waist down until his death in 1998. Three other people were wounded. Bremer served 35 years in prison.

* February 22, 1974: Samuel Byck planned to kill Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as the 36th vice president under P ...

by crashing a commercial airliner into the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

. He hijacked a DC-9 at Baltimore-Washington International Airport after killing a Maryland Aviation Administration

The Maryland Aviation Administration (MAA) is a state agency of Maryland and an airport authority under the jurisdiction of the Maryland Department of Transportation. The agency owns and operates Baltimore/Washington International Airport (BWI) a ...

police officer, and was told that it could not take off with the wheel blocks still in place. After he shot both pilots (one later died), an officer named Charles 'Butch' Troyer shot Byck through the plane's door window. He survived long enough to kill himself by shooting.

Gerald Ford

* Mid-August 1974: Muharem Kurbegovic, also known as The Alphabet Bomber, said in a message that he was going to come to Washington, D.C., and throw a nerve gas bomb at President Gerald Ford, then just ten days into his presidency. Within one day, the

* Mid-August 1974: Muharem Kurbegovic, also known as The Alphabet Bomber, said in a message that he was going to come to Washington, D.C., and throw a nerve gas bomb at President Gerald Ford, then just ten days into his presidency. Within one day, the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA; ) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and ...

, the U.S. Secret Service, and other law enforcement agencies, working out of the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

basement, identified Kurbegovich; he was arrested on August 20. The group had identified his Yugoslav origins, using a CIA voice analysis of his tapes, with court records of the cases handled by his first targets—the judge and the police commissioners—triangulating his identity. Kurbegovic was arrested in 1974 and was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1980.

* September 5, 1975: On the northern grounds of the California State Capitol

The California State Capitol is the seat of the California state government, located in Sacramento, the state capital of California. The building houses the chambers of the California State Legislature, made up of the Assembly and the Senat ...

in Sacramento, Lynette "Squeaky" Fromme, a follower of Charles Manson

Charles Milles Manson (; November 12, 1934 – November 19, 2017) was an American criminal, cult leader, and musician who led the Manson Family, a cult based in California in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Some cult members committed a Manson ...

, drew a Colt M1911 .45-caliber pistol on Ford when he reached to shake her hand in a crowd. She had four cartridges in the pistol's magazine

A magazine is a periodical literature, periodical publication, print or digital, produced on a regular schedule, that contains any of a variety of subject-oriented textual and visual content (media), content forms. Magazines are generally fin ...

but none in the chamber, and as a result, the gun did not fire. She was quickly restrained by Secret Service agent Larry Buendorf. Fromme was sentenced to life in prison, but was released from custody on August 14, 2009 (two years and eight months after Ford's natural death in 2006).

* September 22, 1975: In San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, California, only 17 days after Fromme's attempt, Sara Jane Moore fired a revolver at Ford from away. A bystander, Oliver Sipple, grabbed Moore's arm and the shot missed Ford, striking a building wall and slightly injuring taxi driver John Ludwig. Moore was tried and convicted in federal court, and sentenced to prison for life. She was paroled from a federal prison on December 31, 2007, after serving more than 30 years—one year and five days after Ford's natural death.

The two assassination attempts on Gerald Ford in September 1975 are the only two known cases of women attempting to assassinate an American president.

George H. W. Bush

* April 13, 1993: According to Kuwaiti authorities, and an FBI investigation fourteen Kuwaiti and Iraqi men believed to be working forSaddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein (28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician and revolutionary who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 1979 until Saddam Hussein statue destruction, his overthrow in 2003 during the 2003 invasion of Ira ...

smuggled bombs into Kuwait

Kuwait, officially the State of Kuwait, is a country in West Asia and the geopolitical region known as the Middle East. It is situated in the northern edge of the Arabian Peninsula at the head of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to Iraq–Kuwait ...

, planning to assassinate former President George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushBefore the outcome of the 2000 United States presidential election, he was usually referred to simply as "George Bush" but became more commonly known as "George H. W. Bush", "Bush Senior," "Bush 41," and even "Bush th ...

by a car bomb

A car bomb, bus bomb, van bomb, lorry bomb, or truck bomb, also known as a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED), is an improvised explosive device designed to be detonated in an automobile or other vehicles.

Car bombs can be roug ...

during his visit to Kuwait University

Kuwait University (, abbreviated as Kuniv) is a public university located in Kuwait City, Kuwait.

History

Kuwait University (KU), (in Arabic: جامعة الكويت), was established in October 1966 under Act N. 29/1966. The university was of ...

three months after he had left office in January 1993. The former president was on a visit to Kuwait in 1993 to commemorate the coalition's victory over Iraq in the Persian Gulf War when Kuwaiti officials claimed to have foiled an alleged assassination plot and arrested the suspects. At the time the former president was accompanied by his wife, two of his sons, former Secretary of State James Baker

James Addison Baker III (born April 28, 1930) is an American attorney, diplomat and statesman. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as the 10th White House chief of staff and 67th United States secretary ...

, former Chief of Staff John Sununu, and former Treasury Secretary Nicholas Brady. Of the 17 people Kuwaiti authorities arrested, two suspects, Wali Abdelhadi Ghazali, and Raad Abdel-Amir al-Assadi, retracted their confessions at the trial, claiming that they were coerced. A Kuwaiti court convicted all but one of the defendants. Then-president Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician and lawyer who was the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, ...

responded by launching a cruise missile attack on an Iraqi intelligence building in the Mansour district

Al-Mansour or just Mansour () is one of the nine administrative districts in Baghdad, administrative districts in Baghdad, Iraq. It is in western Baghdad and is bounded on the east by Karkh, al-Karkh district in central Baghdad, to the north by K ...

of Baghdad

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

. The plot was used as one of the justifications for the Iraq Resolution

The Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002,George, who had succeeded Clinton as president, authorizing the 2003 U.S. invasion of the country. An analysis by the CIA's Counterterrorism Center concludes the assassination plot was likely fabricated by Kuwaiti authorities; however, at the time the FBI established that the plot had been directed by the Iraqi Intelligence Service (IIS), and the CIA had received information suggesting that Saddam Hussein had authorized the assassination attempt to get revenge against the U.S., to punish Kuwait for working with the U.S., and to keep other Arab states for intervening in Iraq any further. The day before the attack, on April 12, 1993, the then U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. and future 64th U.S. secretary of state,

"Court Sentences Man to 40 Years For Trying to Kill the President,"

June 30, 1995, ''

CNN, October 24, 2018

* September 15, 2024: 58-year-old Ryan Wesley Routh was spotted by a

* September 15, 2024: 58-year-old Ryan Wesley Routh was spotted by a

Volume 1

an

Volume 2

* * * * * * * {{Lists of US Presidents and Vice Presidents

Madeleine Albright

Madeleine Jana Korbel Albright (born Marie Jana Körbelová, later Korbelová; May 15, 1937 – March 23, 2022) was an American diplomat and political science, political scientist who served as the 64th United States Secretary of State, United S ...

, went before the U.N. Security Council to present evidence of the Iraqi plot with the hope of gaining international support.

Bill Clinton

* January 21, 1994: Ronald Gene Barbour, a retired military officer and freelance writer, plotted to kill Clinton while the president was jogging. Barbour returned to Florida a week later without having fired the shots at the president, who was on a state visit to Russia. Barbour was sentenced to five years in prison and was released in 1998. * October 29, 1994: Francisco Martin Duran fired at least 29 shots with a 7.62×39mm SKSsemi-automatic rifle

A semi-automatic rifle is a type of rifle that fires a single round each time the Trigger (firearms), trigger is pulled while automatically loading the next Cartridge (firearms), cartridge. These rifles were developed Pre-World War II, and w ...

at the White House from a fence overlooking the North Lawn, thinking that Clinton was among the men in dark suits standing there (Clinton was inside). Three tourists, Harry Rakosky, Ken Davis and Robert Haines, tackled Duran before he could injure anyone. Found to have a suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death.

Risk factors for suicide include mental disorders, physical disorders, and substance abuse. Some suicides are impulsive acts driven by stress (such as from financial or ac ...

note in his pocket, Duran was sentenced to 40 years in prison.Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American not-for-profit organization, not-for-profit news agency headquartered in New York City.

Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association, and produces news reports that are dist ...

:"Court Sentences Man to 40 Years For Trying to Kill the President,"

June 30, 1995, ''

New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'', retrieved July 14, 2024

* November 1994: Osama bin Laden

Osama bin Laden (10 March 19572 May 2011) was a militant leader who was the founder and first general emir of al-Qaeda. Ideologically a pan-Islamist, Bin Laden participated in the Afghan ''mujahideen'' against the Soviet Union, and support ...

recruited Ramzi Yousef, the mastermind of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing

The 1993 World Trade Center bombing was a terrorist attack carried out by Ramzi Yousef and associates against the United States on February 26, 1993, when a van bomb detonated below the North Tower of the World Trade Center complex in Manhat ...

, to attempt to assassinate Clinton. However, Yousef decided that security would be too effective and decided to target Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II (born Karol Józef Wojtyła; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 16 October 1978 until Death and funeral of Pope John Paul II, his death in 2005.

In his you ...

instead.

* November 24, 1996: During his visit to the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation

Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC ) is an inter-governmental forum for 21 member economy , economies in the Pacific Rim that promotes free trade throughout the Asia-Pacific region. Following the success of Association of Southeast Asia ...

(APEC) forum in Manila, Clinton's motorcade was rerouted before it was to drive over a bridge. Secret Service officers had intercepted a message suggesting that an attack was imminent, and Lewis Merletti, the director of the Secret Service, ordered the motorcade to be re-routed. An intelligence team later discovered a bomb under the bridge. Subsequent U.S. investigation "revealed that he plotwas masterminded by a Saudi terrorist living in Afghanistan named Osama bin Laden

Osama bin Laden (10 March 19572 May 2011) was a militant leader who was the founder and first general emir of al-Qaeda. Ideologically a pan-Islamist, Bin Laden participated in the Afghan ''mujahideen'' against the Soviet Union, and support ...

".

* October 2018: A package containing a pipe bomb

A pipe bomb is an improvised explosive device (IED) that uses a tightly sealed section of pipe filled with an explosive material. The containment provided by the pipe means that simple low explosives can be used to produce a relatively larg ...

addressed to his wife Hillary Clinton

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, lawyer and diplomat. She was the 67th United States secretary of state in the administration of Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, a U.S. senator represent ...

and sent to their home in Chappaqua, New York

Chappaqua ( ) is a hamlet and census-designated place in the town of New Castle, in northern Westchester County, New York, United States. It is approximately north of New York City. The hamlet is served by the Chappaqua station of the Metr ...

, was intercepted by the Secret Service. It was one of several mailed to other Democratic leaders in the same week, including former president Barack Obama