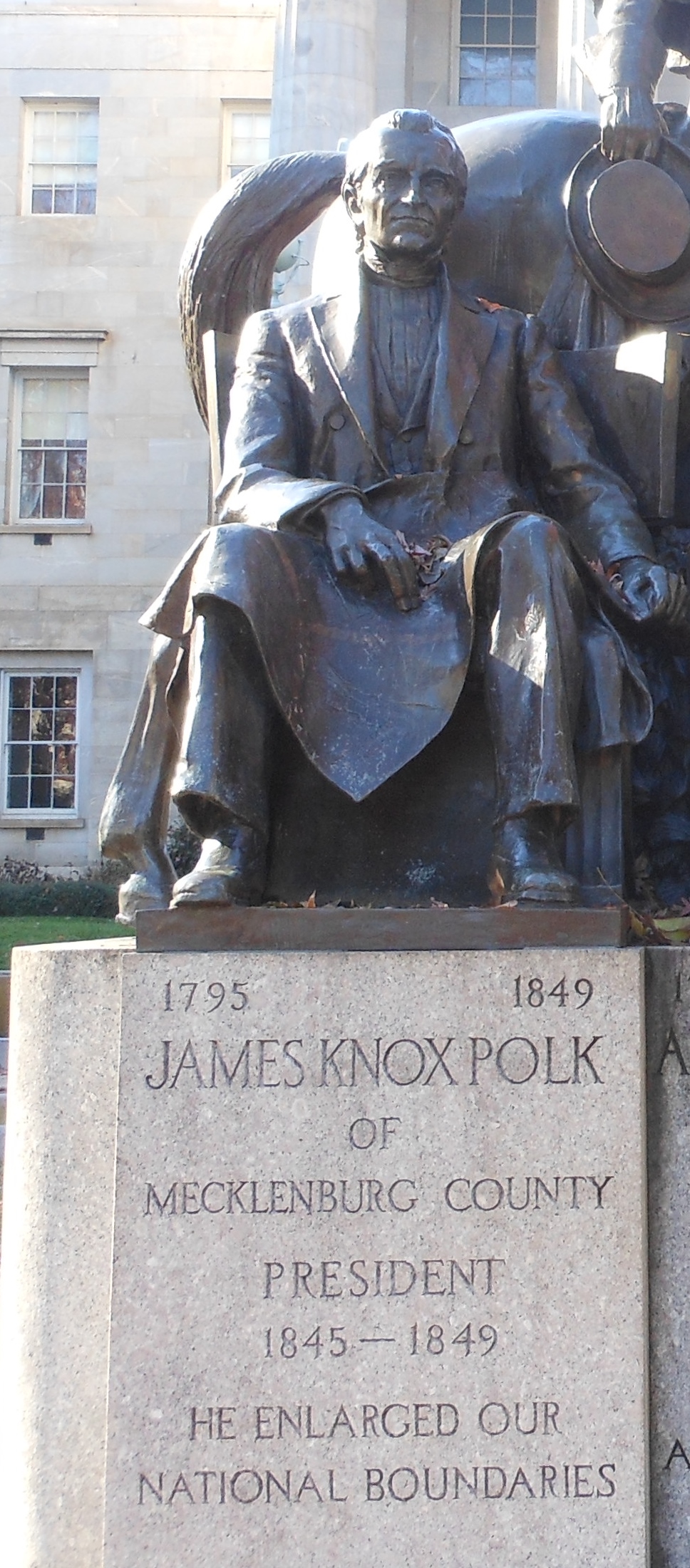

James Knox Polk (; November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

, serving from 1845 to 1849. A protégé of

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

and a member of the

Democratic Party, he was an advocate of

Jacksonian democracy

Jacksonian democracy, also known as Jacksonianism, was a 19th-century political ideology in the United States that restructured a number of federal institutions. Originating with the seventh U.S. president, Andrew Jackson and his supporters, i ...

and extending the territory of the United States. Polk led the U.S. into the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

, and after winning the war he

annexed

Annexation, in international law, is the forcible acquisition and assertion of legal title over one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. In current international law, it is generally held to ...

the

Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas (), or simply Texas, was a country in North America that existed for close to 10 years, from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846. Texas shared borders with Centralist Republic of Mexico, the Republic of the Rio Grande, an ...

, the

Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the United States, Union as the Oreg ...

, and the

Mexican Cession

The Mexican Cession () is the region in the modern-day Western United States that Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United S ...

.

After building a successful law practice in

Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

, Polk was elected to

its state legislature in 1823 and then to the

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

in 1825, becoming a strong supporter of Jackson. After serving as chairman of the

Ways and Means Committee

A ways and means committee is a government body that is charged with reviewing and making recommendations for government budgets. Because the raising of revenue is vital to carrying out governmental operations, such a committee is tasked with fi ...

, he became

Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hung ...

in 1835, the only person to serve both as Speaker and U.S. president. Polk left Congress to run for

governor of Tennessee

The governor of Tennessee is the head of government of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the commander-in-chief of the U.S. state, state's Tennessee Military Department, military forces. The governor is the only official in the Government of Tenne ...

, winning in 1839 but losing in 1841 and 1843. He was a

dark-horse candidate in the

1844 presidential election as the

Democratic Party nominee; he entered his party's convention as a potential nominee for vice president but emerged as a compromise to head the ticket when no presidential candidate could gain the necessary two-thirds majority. In the general election, Polk narrowly defeated

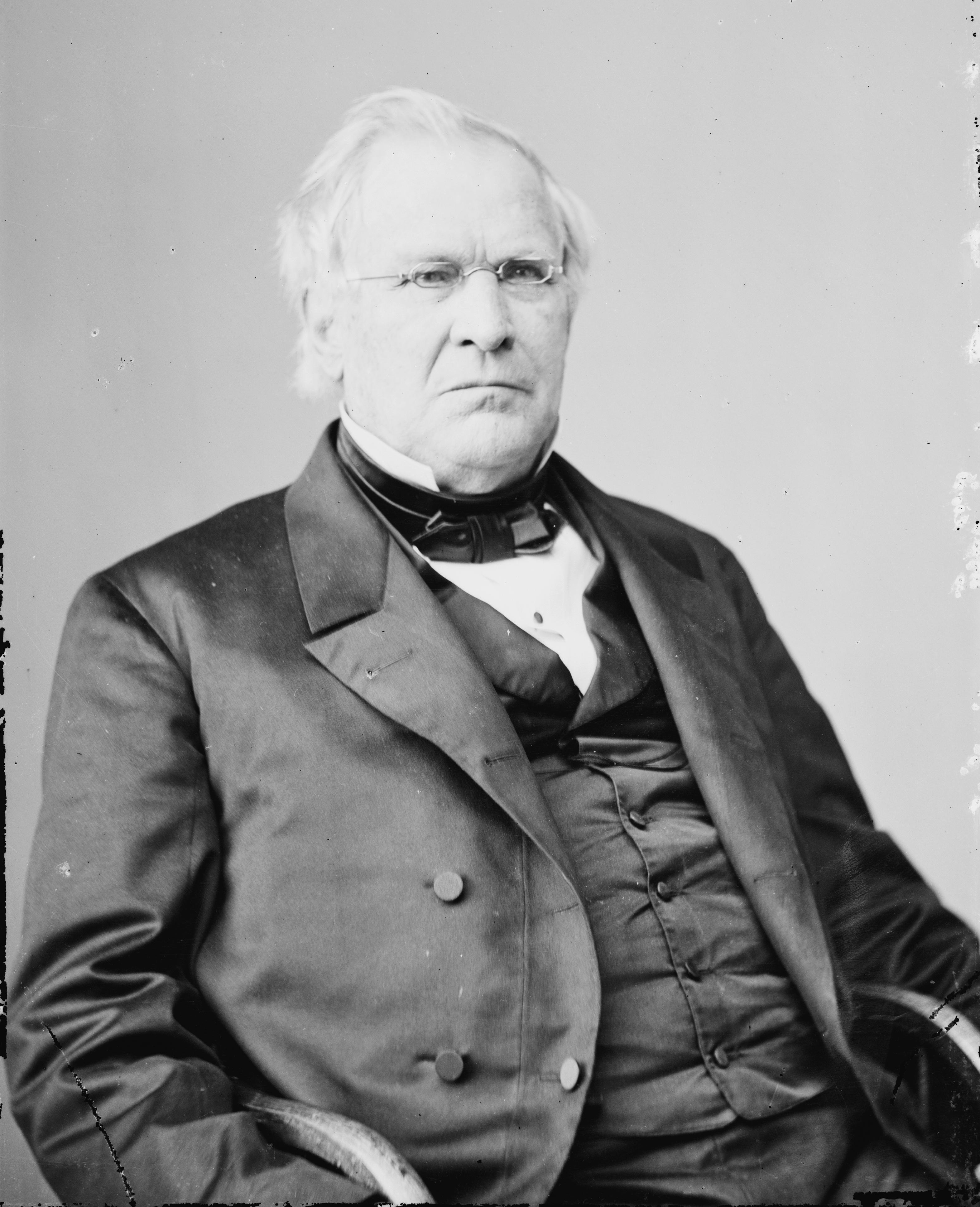

Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

of the

Whig Party and pledged to serve only one term.

After a negotiation fraught with the risk of war, Polk reached a settlement with

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

over the

disputed Oregon Country, with the territory for the most part divided along the

49th parallel. He oversaw victory in the Mexican–American War, resulting in

Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

's cession of the entire

American Southwest

The Southwestern United States, also known as the American Southwest or simply the Southwest, is a geographic and cultural list of regions of the United States, region of the United States that includes Arizona and New Mexico, along with adjacen ...

. He secured a substantial reduction of

tariff

A tariff or import tax is a duty (tax), duty imposed by a national Government, government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods ...

rates with the

Walker tariff of 1846. The same year, he achieved his other major goal, reestablishment of the

Independent Treasury

The Independent Treasury was the system for managing the money supply of the United States federal government through the U.S. Treasury and its sub-treasuries, independently of the national banking and financial systems. It was created on August 6, ...

system. True to his campaign pledge to serve one term (one of the few U.S. presidents to make and keep such a pledge), Polk left office in 1849 and returned to Tennessee, where he died of

cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

soon afterward.

Though he has become relatively obscure, scholars have

ranked

A ranking is a relationship between a set of items, often recorded in a list, such that, for any two items, the first is either "ranked higher than", "ranked lower than", or "ranked equal to" the second. In mathematics, this is known as a weak ...

Polk in the upper tier of U.S. presidents, mostly for his ability to promote and achieve the major items on his presidential agenda. At the same time, he has been criticized for leading the country into a war with Mexico that exacerbated

sectional divides. A property owner who used slave labor, he kept a plantation in

Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

and increased his slave ownership during his presidency. Polk's policy of territorial expansion saw the nation reach the Pacific coast and almost all its contiguous borders. He helped make the U.S. a nation poised to become a world power, but with divisions between

free and slave states gravely exacerbated, setting the stage for the

Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

.

Early life

James Knox Polk was born on November 2, 1795, in a log cabin in

Pineville, North Carolina

Pineville (; locally ) is a suburban town in the southernmost portion of Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, United States. Part of the Charlotte metropolitan area, it is situated in the Waxhaws region between Charlotte and Fort Mill. As of ...

.

[Borneman, pp. 4–6] He was the first of 10 children born into a family of farmers.

His mother Jane named him after her father, James Knox.

His father

Samuel Polk was a farmer, slaveholder, and surveyor of

Scots-Irish descent. The Polks had immigrated to America in the late 17th century, settling initially on the

Eastern Shore of Maryland

The Eastern Shore of Maryland is a part of the U.S. state of Maryland that lies mostly on the east side of the Chesapeake Bay. Nine counties are normally included in the region. The Eastern Shore is part of the larger Delmarva Peninsula that Ma ...

but later moving to south-central

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

and then to the Carolina hill country.

The Knox and Polk families were

Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

. While Polk's mother remained a devout Presbyterian, his father, whose own father

Ezekiel Polk

Ezekiel Polk (December 7, 1747 – August 31, 1824) was an American soldier, pioneer and the paternal grandfather of President James K. Polk.

Early life

Ezekiel Polk was born on December 7, 1747, the seventh of eight children born to William ...

was a

deist

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin term '' deus'', meaning "god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge and asserts that empirical reason and observation ...

, rejected dogmatic Presbyterianism. He refused to declare his belief in Christianity at his son's baptism, and the minister refused to baptize young James.

[Haynes, pp. 4–6.] Nevertheless, James' mother "stamped her rigid orthodoxy on James, instilling lifelong Calvinistic traits of self-discipline, hard work, piety,

individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

, and a belief in the imperfection of human nature", according to

James A. Rawley's ''

American National Biography

The ''American National Biography'' (ANB) is a 24-volume biographical encyclopedia set that contains about 17,400 entries and 20 million words, first published in 1999 by Oxford University Press under the auspices of the American Council of Lea ...

'' article.

In 1803, Ezekiel Polk led four of his adult children and their families to the

Duck River area in what is now

Maury County, Tennessee

Maury County ( ) is a county located in the U.S. state of Tennessee, in the Middle Tennessee region. As of the 2020 census, the population was 100,974. Its county seat is Columbia. Maury County is part of the Nashville-Davidson– Murfreesb ...

; Samuel Polk and his family followed in 1806. The Polk clan dominated politics in Maury County and in the new town of

Columbia. Samuel became a county judge, and the guests at his home included

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

, who had already served as a judge and in Congress. James learned from the political talk around the dinner table; both Samuel and Ezekiel were strong supporters of President

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

and opponents of the

Federalist Party

The Federalist Party was a conservativeMultiple sources:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* and nationalist American political party and the first political party in the United States. It dominated the national government under Alexander Hamilton from 17 ...

.

Polk suffered from frail health as a child, a particular disadvantage in a frontier society. His father took him to see prominent Philadelphia physician Dr.

Philip Syng Physick

Philip Syng Physick (July 7, 1768 – December 15, 1837) was an American physician and professor born in Philadelphia. He was the first professor of surgery and later of anatomy at the University of Pennsylvania medical school from 1805 to 1831 ...

for urinary stones. The journey was broken off by James's severe pain, and Dr.

Ephraim McDowell

Ephraim McDowell (November 11, 1771 – June 25, 1830) was an American physician and pioneer surgeon. The first person to successfully remove an ovarian tumor, he has been called "the father of ovariotomy" as well as founding father of abdomina ...

of

Danville, Kentucky

Danville is a list of Kentucky cities, home rule-class city and the county seat of Boyle County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 17,236 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Danville is the principal city of the Danville Micr ...

, operated to remove them. No anesthetic was available except brandy. The operation was successful, but it may have left James impotent or sterile, as he had no children. He recovered quickly and became more robust. His father offered to bring him into one of his businesses, but he wanted an education and enrolled at a Presbyterian academy in 1813.

[Borneman, p. 8] He became a member of the

Zion Church near his home in 1813 and enrolled in the Zion Church Academy. He then entered Bradley Academy in

Murfreesboro, Tennessee

Murfreesboro is a city in Rutherford County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. Its population was 165,430 according to the 2023 census estimate, up from 108,755 residents certified in 2010 United States census, 2010. Murfreesboro i ...

, where he proved a promising student.

[Borneman, p. 13][Leonard, p. 6]

In January 1816, Polk was admitted into the

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC, UNC–Chapel Hill, or simply Carolina) is a public university, public research university in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States. Chartered in 1789, the university first began enrolli ...

as a second-semester sophomore. The Polk family had connections with the university, then a small school of about 80 students; Samuel was its land agent in Tennessee and his cousin

William Polk was a trustee. Polk's roommate was

William Dunn Moseley

William Dunn Moseley (February 1, 1795January 4, 1863) was an American politician. Born in North Carolina, Moseley became a Democratic politician and served in the state senate.

Later he moved to Florida, which became a state in 1845. That y ...

, who became the first Governor of Florida. Polk joined the

Dialectic Society where he took part in debates, became its president, and learned the art of oratory.

In one address, he warned that some American leaders were flirting with

monarchical

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, reigns as head of state for the rest of their life, or until abdication. The extent of the authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutio ...

ideals, singling out

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

, a foe of Jefferson. Polk graduated with honors in May 1818.

[Borneman, pp. 8–9]

After graduation, Polk returned to

Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville, often known as Music City, is the capital and List of municipalities in Tennessee, most populous city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the county seat, seat of Davidson County, Tennessee, Davidson County in Middle Tennessee, locat ...

to study law under renowned trial attorney

Felix Grundy

Felix Grundy (September 11, 1777 – December 19, 1840) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 13th United States Attorney General. He also had served several terms as a congressman and as a U.S. senator from Tennessee. He ...

,

[Borneman, p. 10] who became his first mentor. On September 20, 1819, he was elected clerk of the

Tennessee State Senate

The Tennessee Senate is the upper house of the U.S. state of Tennessee's state legislature, which is known formally as the Tennessee General Assembly.

The Tennessee Senate has the power to pass resolutions concerning essentially any issue reg ...

, which then sat in Murfreesboro and to which Grundy had been elected.

[Borneman, p. 11] He was re-elected clerk in 1821 without opposition, and continued to serve until 1822. In June 1820, he was admitted to the Tennessee bar, and his first case was to defend his father against a public fighting charge; he secured his release for a one-dollar fine.

He opened an office in Maury County

and was successful as a lawyer, due largely to the many cases arising from the

Panic of 1819

The Panic of 1819 was the first widespread and durable financial crisis in the United States that slowed westward expansion in the Cotton Belt and was followed by a general collapse of the American economy that persisted through 1821. The Panic ...

, a severe depression. His law practice subsidized his political career.

[Leonard, p. 5]

Early political career

Tennessee state legislator

By the time the legislature adjourned its session in September 1822, Polk was determined to be a candidate for the

Tennessee House of Representatives

The Tennessee House of Representatives is the lower house of the Tennessee General Assembly, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Tennessee.

Constitutional requirements

According to the state constitution of 1870, this body is to consis ...

. The election was in August 1823, almost a year away, allowing him ample time for campaigning.

Already involved locally as a member of the

Masons, he was commissioned in the Tennessee militia as a captain in the cavalry regiment of the 5th Brigade. He was later appointed a colonel on the staff of Governor

William Carroll, and was afterwards often referred to as "Colonel".

[Seigenthaler, p. 25] Although many of the voters were members of the Polk clan, the young politician campaigned energetically. People liked Polk's oratory, which earned him the nickname "Napoleon of the Stump". At the polls, where Polk provided alcoholic refreshments for his voters, he defeated incumbent William Yancey.

[Borneman, p. 14]

Beginning in early 1822, Polk courted

Sarah Childress—they were engaged the following year and married on January 1, 1824, in Murfreesboro.

Educated far better than most women of her time, especially in frontier Tennessee, Sarah Polk was from one of the state's most prominent families.

During James's political career Sarah assisted her husband with his speeches, gave him advice on policy matters, and played an active role in his campaigns.

Rawley noted that Sarah Polk's grace, intelligence and charming conversation helped compensate for her husband's often austere manner.

Polk's first mentor was Grundy, but in the legislature, Polk came increasingly to oppose him on such matters as

land reform

Land reform (also known as agrarian reform) involves the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership, land use, and land transfers. The reforms may be initiated by governments, by interested groups, or by revolution.

Lan ...

, and came to support the policies of Andrew Jackson, by then a military hero for his victory at the

Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815, between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the Frenc ...

(1815). Jackson was a family friend to both the Polks and the Childresses—there is evidence Sarah Polk and her siblings called him "Uncle Andrew"—and James Polk quickly came to support his presidential ambitions for 1824. When the

Tennessee Legislature

The Tennessee General Assembly (TNGA) is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is a part-time bicameral legislature consisting of a Senate and a House of Representatives. The Speaker of the Senate carries the additional title ...

deadlocked on whom to elect as U.S. senator in 1823 (until 1913, legislators, not the people, elected senators), Jackson's name was placed in nomination. Polk broke from his usual allies, casting his vote for Jackson, who won. The Senate seat boosted Jackson's presidential chances by giving him current political experience to match his military accomplishments. This began an alliance that would continue until Jackson's death early in Polk's presidency.

Polk, through much of his political career, was known as "Young Hickory", based on the nickname for Jackson, "Old Hickory". Polk's political career was as dependent on Jackson as his nickname implied.

In the

1824 United States presidential election

Presidential elections were held in the United States from October 26 to December 2, 1824. Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay and William Crawford were the primary contenders for the presidency. The result of the election was in ...

, Jackson got the most electoral votes (he also led in the popular vote) but as he did not receive a majority in the

Electoral College

An electoral college is a body whose task is to elect a candidate to a particular office. It is mostly used in the political context for a constitutional body that appoints the head of state or government, and sometimes the upper parliament ...

, the election was thrown into the

U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Article One of th ...

, which chose Secretary of State

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diploma ...

, who had received the second-most of each. Polk, like other Jackson supporters, believed that Speaker of the House

Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

had traded his support as fourth-place finisher (the House may only choose from among the top three) to Adams in a

Corrupt Bargain

In American political jargon, corrupt bargain is a backdoor deal for or involving the U.S. presidency. Three events in particular in American political history have been called the corrupt bargain: the 1824 United States presidential election, ...

in exchange for being the new Secretary of State. Polk had in August 1824 declared his candidacy for the following year's election to the House of Representatives from

Tennessee's 6th congressional district

The 6th congressional district of Tennessee is a congressional district in Middle Tennessee.

It has been represented by Republican John Rose since January 2019.

Much of the sixth district is rural and wooded. It is spread across the geographic ...

.

[Borneman, p. 23] The district stretched from Maury County south to the Alabama line, and extensive electioneering was expected of the five candidates. Polk campaigned so vigorously that Sarah began to worry about his health. During the campaign, Polk's opponents said that at the age of 29 Polk was too young for the responsibility of a seat in the House, but he won the election with 3,669 votes out of 10,440 and took his seat in Congress later that year.

Jackson disciple

When Polk arrived in

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

for Congress's regular session in December 1825, he roomed in Benjamin Burch's boarding house with other Tennessee representatives, including

Sam Houston

Samuel Houston (, ; March 2, 1793 – July 26, 1863) was an American general and statesman who played a prominent role in the Texas Revolution. He served as the first and third president of the Republic of Texas and was one of the first two indi ...

. Polk made his first major speech on March 13, 1826, in which he said that the Electoral College should be abolished and that the president should be elected by popular vote.

[Borneman, p. 24] Remaining bitter at the alleged Corrupt Bargain between Adams and Clay, Polk became a vocal critic of the

Adams administration, frequently voting against its policies. Sarah Polk remained at home in Columbia during her husband's first year in Congress, but accompanied him to Washington beginning in December 1826; she assisted him with his correspondence and came to hear James's speeches.

Polk won re-election in 1827 and continued to oppose the Adams administration.

[Borneman, p. 26] He remained in close touch with Jackson, and when Jackson ran for president in

1828

Events

January–March

* January 4 – Jean Baptiste Gay, vicomte de Martignac succeeds the Jean-Baptiste de Villèle, Comte de Villèle, as Prime Minister of France.

* January 8 – The Democratic Party of the United States is organiz ...

, Polk was an advisor on his campaign. Following Jackson's victory over Adams, Polk became one of the new President's most prominent and loyal supporters. Working on Jackson's behalf, Polk successfully opposed federally-funded "

internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, can ...

" such as a proposed Buffalo-to-New Orleans road, and he was pleased by Jackson's

Maysville Road veto

The Maysville Road veto occurred on May 27, 1830, when United States President Andrew Jackson vetoed a bill that would allow the federal government to purchase stock in the Maysville, Washington, Paris, and Lexington Turnpike Road Company, which h ...

in May 1830, when Jackson blocked a bill to finance a road extension entirely within one state, Kentucky, deeming it unconstitutional. Jackson opponents alleged that the veto message, which strongly complained about Congress' penchant for passing

pork barrel

''Pork barrel'', or simply ''pork'', is a metaphor for allocating government spending to localized projects in the representative's district or for securing direct expenditures primarily serving the sole interests of the representative. The u ...

projects, was written by Polk, but he denied this, stating that the message was entirely the President's.

Polk served as Jackson's most prominent House ally in the "

Bank War

The Bank War was a political struggle that developed over the issue of rechartering the Second Bank of the United States (B.U.S.) during the presidency of Andrew Jackson (1829–1837). The affair resulted in the shutdown of the Bank and its repl ...

" that developed over Jackson's opposition to the re-authorization of the

Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Second Report on Public Credit, Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January ...

.

[Merry, pp. 42–43] The Second Bank, headed by

Nicholas Biddle of Philadelphia, not only held federal dollars but controlled much of the credit in the United States, as it could present currency issued by local banks for redemption in gold or silver. Some Westerners, including Jackson, opposed the Second Bank, deeming it a monopoly acting in the interest of Easterners. Polk, as a member of the

House Ways and Means Committee

A ways and means committee is a government body that is charged with reviewing and making recommendations for government budgets. Because the raising of revenue is vital to carrying out governmental operations, such a committee is tasked with fi ...

, conducted investigations of the Second Bank, and though the committee voted for a bill to renew the bank's charter (scheduled to expire in 1836), Polk issued a strong minority report condemning the bank. The bill passed Congress in 1832; however, Jackson vetoed it and Congress failed to override the veto. Jackson's action was highly controversial in Washington but had considerable public support, and he

won easy re-election in 1832.

Like most Southerners, Polk favored low tariffs on imported goods, and initially sympathized with

John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun (; March 18, 1782March 31, 1850) was an American statesman and political theorist who served as the seventh vice president of the United States from 1825 to 1832. Born in South Carolina, he adamantly defended American s ...

's opposition to the

Tariff of Abominations

The Tariff of 1828 was a very high protective tariff that became law in the United States on May 19, 1828. It was a bill designed to fail in Congress because it was seen by free trade supporters as hurting both industry and farming, but it pa ...

during the

Nullification Crisis of 1832–1833, but came over to Jackson's side as Calhoun moved towards advocating secession. Thereafter, Polk remained loyal to Jackson as the President sought to assert federal authority. Polk condemned secession and supported the

Force Bill

The Force Bill, formally titled "''An Act further to provide for the collection of duties on imports''", (1833), refers to legislation enacted by the 22nd U.S. Congress on March 2, 1833, during the nullification crisis.

Passed by Congress a ...

against South Carolina, which had claimed the authority to nullify federal tariffs. The matter was settled by Congress passing a

compromise tariff

The Tariff of 1833 (also known as the Compromise Tariff of 1833, ch. 55, ), enacted on March 2, 1833, was proposed by Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun as a resolution to the Nullification Crisis. Enacted under Andrew Jackson's presidency, it was ...

.

Ways and Means Chair and Speaker of the House

In December 1833, after being elected to a fifth consecutive term, Polk, with Jackson's backing, became the chairman of Ways and Means, a powerful position in the House.

[Borneman, p. 33] In that position, Polk supported Jackson's withdrawal of federal funds from the Second Bank. Polk's committee issued a report questioning the Second Bank's finances and another supporting Jackson's actions against it. In April 1834, the Ways and Means Committee reported a bill to regulate state deposit banks, which, when passed, enabled Jackson to deposit funds in

pet banks

Pet banks is a derogatory term for state banks selected by the U.S. Department of Treasury to receive surplus Treasury funds in 1833. Pet banks are sometimes confused with wildcat banks. Although the two are distinct types of institutions that ...

, and Polk got legislation passed to allow the sale of the government's stock in the Second Bank.

In June 1834,

Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hung ...

Andrew Stevenson

Andrew Stevenson (January 21, 1784 – January 25, 1857) was an American politician, lawyer and diplomat. He represented Richmond, Virginia in the Virginia House of Delegates and eventually became its speaker before being elected to the United ...

resigned from Congress to become

Minister to the United Kingdom.

[Borneman, p. 34] With Jackson's support, Polk ran for speaker against fellow Tennessean

John Bell, Calhoun disciple

Richard Henry Wilde

Richard Henry Wilde (September 24, 1789 – September 10, 1847) was a United States representative and lawyer from Georgia.

Biography

Wilde was born in Dublin, Ireland, in 1789 to Richard Wilde and Mary Newitt, but came to America at age eight ...

, and

Joel Barlow Sutherland of Pennsylvania. After ten ballots, Bell, who had the support of many opponents of the administration, defeated Polk. Jackson called in political debts to try to get Polk elected Speaker of the House at the start of the next Congress in December 1835, assuring Polk in a letter he meant him to burn that New England would support him for speaker. They were successful; Polk defeated Bell to take the speakership.

[Borneman, p. 35]

According to Thomas M. Leonard, "by 1836, while serving as Speaker of the House of Representatives, Polk approached the zenith of his congressional career. He was at the center of Jacksonian Democracy on the House floor, and, with the help of his wife, he ingratiated himself into Washington's social circles."

[Leonard, p. 23] The prestige of the speakership caused them to move from a boarding house to their own residence on Pennsylvania Avenue.

In the

1836 presidential election, Vice President

Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was the eighth president of the United States, serving from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as Attorney General o ...

, Jackson's chosen successor, defeated multiple

Whig candidates, including Tennessee Senator

Hugh Lawson White

Hugh Lawson White (October 30, 1773April 10, 1840) was an American politician during the first third of the 19th century. After filling in several posts particularly in Tennessee's judiciary and state legislature since 1801, thereunder as a Tenn ...

. Greater Whig strength in Tennessee helped White carry his state, though Polk's home district went for Van Buren. Ninety percent of Tennessee voters had supported Jackson in 1832, but many in the state disliked the destruction of the Second Bank, or were unwilling to support Van Buren.

As Speaker of the House, Polk worked for the policies of Jackson and later Van Buren. Polk appointed committees with Democratic chairs and majorities, including the New York radical

C. C. Cambreleng as the new Ways and Means chair, although he tried to maintain the speaker's traditional nonpartisan appearance. The two major issues during Polk's speakership were slavery and, after the

Panic of 1837

The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis in the United States that began a major depression (economics), depression which lasted until the mid-1840s. Profits, prices, and wages dropped, westward expansion was stalled, unemployment rose, and pes ...

, the economy. Polk firmly enforced the "

gag rule

A gag rule is a rule that limits or forbids the raising, consideration, or discussion of a particular topic, often but not always by members of a legislative or decision-making body. A famous example of gag rules is the series of rules concerni ...

", by which the House of Representatives would not accept or debate citizen petitions regarding slavery.

[Seigenthaler, pp. 57–61] This ignited fierce protests from John Quincy Adams, who was by then a congressman from Massachusetts and an abolitionist. Instead of finding a way to silence Adams, Polk frequently engaged in useless shouting matches, leading Jackson to conclude that Polk should have shown better leadership. Van Buren and Polk faced pressure to rescind the

Specie Circular

The Specie Circular is a United States presidential executive order issued by President Andrew Jackson on 11 July 1836 pursuant to the Coinage Act of 1834. It required payment for government land to be in gold and silver (specie). It was repe ...

, Jackson's 1836 order that payment for government lands be in gold and silver. Some believed this had led to the crash by causing a lack of confidence in paper currency issued by banks. Despite such arguments, with support from Polk and his cabinet, Van Buren chose to back the Specie Circular. Polk and Van Buren attempted to establish an Independent Treasury system that would allow the government to oversee its own deposits (rather than using pet banks), but the bill was defeated in the House.

It eventually passed in 1840.

Using his thorough grasp of the House's rules, Polk attempted to bring greater order to its proceedings. Unlike many of his peers, he never challenged anyone to a duel no matter how much they insulted his honor.

[Seigenthaler, p. 62] The economic downturn cost the Democrats seats, so that when he faced re-election as Speaker of the House in December 1837, he won by only 13 votes, and he foresaw defeat in 1839. Polk by then had presidential ambitions but was well aware that no Speaker of the House had ever become president (Polk is still the only one to have held both offices). After seven terms in the House, two as speaker, he announced that he would not seek re-election, choosing instead to run for Governor of Tennessee in the 1839 election.

Governor of Tennessee

In 1835, the Democrats had lost the governorship of Tennessee for the first time in their history, and Polk decided to return home to help the party. Tennessee was afire for White and Whiggism; the state had reversed its political loyalties since the days of Jacksonian domination. As head of the state Democratic Party, Polk undertook his first statewide campaign, He opposed Whig incumbent

Newton Cannon

Newton Cannon (May 22, 1781 – September 16, 1841) was an American politician who served as the eighth Governor of Tennessee from 1835 to 1839. He also served several terms in the United States House of Representatives, from 1814 to 1817, and fr ...

, who sought a third two-year term as governor. The fact that Polk was the one called upon to "redeem" Tennessee from the Whigs tacitly acknowledged him as head of the state Democratic Party.

Polk campaigned on national issues, whereas Cannon stressed state issues. After being bested by Polk in the early debates, the governor retreated to Nashville, the state capital, alleging important official business. Polk made speeches across the state, seeking to become known more widely than just in his native

Middle Tennessee

Middle Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of Tennessee that composes roughly the central portion of the state. It is delineated according to state law as 41 of the state's 95 counties. Middle Tennessee contains the state's capital an ...

. When Cannon came back on the campaign trail in the final days, Polk pursued him, hastening the length of the state to be able to debate the governor again. On Election Day, August 1, 1839, Polk defeated Cannon, 54,102 to 51,396, as the Democrats recaptured the state legislature and won back three congressional seats.

Tennessee's governor had limited power—there was no gubernatorial veto, and the small size of the state government limited any political patronage. But Polk saw the office as a springboard for his national ambitions, seeking to be nominated as Van Buren's vice presidential running mate at the

1840 Democratic National Convention in Baltimore in May. Polk hoped to be the replacement if Vice President

Richard Mentor Johnson

Richard Mentor Johnson (October 17, 1780 – November 19, 1850) was an American lawyer, military officer and politician who served as the ninth vice president of the United States from 1837 to 1841 under President Martin Van Buren. He is ...

was dumped from the ticket; Johnson was disliked by many Southern whites for fathering two daughters by a biracial mistress and attempting to introduce them into white society. Johnson was from Kentucky, so Polk's Tennessee residence would keep the New Yorker Van Buren's ticket balanced. The convention chose to endorse no one for vice president, stating that a choice would be made once the popular vote was cast. Three weeks after the convention, recognizing that Johnson was too popular in the party to be ousted, Polk withdrew his name. The Whig presidential candidate, General

William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was the ninth president of the United States, serving from March 4 to April 4, 1841, the shortest presidency in U.S. history. He was also the first U.S. president to die in office, causin ...

, conducted

a rollicking campaign with the motto "

Tippecanoe and Tyler Too

"Tippecanoe and Tyler Too", originally published as "Tip and Ty", is a campaign song of the Whig Party's Log Cabin Campaign in the 1840 United States presidential election. Its lyrics sang the praises of Whig candidates William Henry Harriso ...

", easily winning both the national vote and that in Tennessee. Polk campaigned in vain for Van Buren

[Leonard, p. 32] and was embarrassed by the outcome; Jackson, who had returned to his home,

the Hermitage, near Nashville, was horrified at the prospect of a Whig administration.

[Borneman, pp. 46–47] In the 1840 election, Polk received one vote from a

faithless elector

In the United States Electoral College, a faithless elector is an elector who does not vote for the candidates for U.S. President and U.S. Vice President for whom the elector had pledged to vote, and instead votes for another person for one or ...

in the

Electoral College

An electoral college is a body whose task is to elect a candidate to a particular office. It is mostly used in the political context for a constitutional body that appoints the head of state or government, and sometimes the upper parliament ...

's vote for vice president. Harrison's death after a month in office in 1841 left the presidency to Vice President

John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president of the United States, vice president in 1841. He was elected ...

, who soon broke with the Whigs.

Polk's three major programs during his governorship; regulating state banks, implementing state internal improvements, and improving education all failed to win the approval of the legislature.

[Seigenthaler, p. 66] His only major success as governor was his politicking to secure the replacement of Tennessee's two Whig U.S. senators with Democrats.

Polk's tenure was hindered by the continuing nationwide economic crisis that had followed the Panic of 1837 and which had caused Van Buren to lose the

1840 election.

Encouraged by the success of Harrison's campaign, the Whigs ran a freshman legislator from frontier

Wilson County,

James C. Jones against Polk in 1841. "Lean Jimmy" had proven one of their most effective gadflies against Polk, and his lighthearted tone at campaign debates was very effective against the serious Polk. The two debated the length of Tennessee, and Jones's support of distribution to the states of surplus federal revenues, and of a national bank, struck a chord with Tennessee voters. On election day in August 1841, Polk was defeated by 3,000 votes, the first time he had been beaten at the polls.

Polk returned to Columbia and the practice of law and prepared for a rematch against Jones in 1843, but though the new governor took less of a joking tone, it made little difference to the outcome, as Polk was beaten again, this time by 3,833 votes.

[Borneman, p. 64][Seigenthaler, p. 68] In the wake of his second statewide defeat in three years, Polk faced an uncertain political future.

[Merry, pp. 47–49]

Election of 1844

Democratic nomination

Despite his loss, Polk was determined to become the next

vice president of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest ranking office in the Executive branch of the United States government, executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks f ...

, seeing it as a path to the presidency.

[Merry, pp. 43–44] Van Buren was the frontrunner for the

1844

In the Philippines, 1844 had only 365 days, when Tuesday, December 31 was skipped as Monday, December 30 was immediately followed by Wednesday, January 1, 1845, the next day after. The change also applied to Caroline Islands, Guam, Marian ...

Democratic nomination, and Polk engaged in a careful campaign to become his running mate.

[Merry, pp. 50–53] The former president faced opposition from Southerners who feared his views on slavery, while his handling of the Panic of 1837—he had refused to rescind the Specie Circular—aroused opposition from some in the West (modern

Midwestern United States

The Midwestern United States (also referred to as the Midwest, the Heartland or the American Midwest) is one of the four census regions defined by the United States Census Bureau. It occupies the northern central part of the United States. It ...

) who believed his

hard money policies had hurt their section of the country.

[ Many Southerners backed Calhoun's candidacy, Westerners rallied around Senator ]Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was a United States Army officer and politician. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He was also the 1 ...

of Michigan, and former Vice President Johnson also maintained a strong following among Democrats.[ Jackson assured Van Buren by letter that Polk in his campaigns for governor had "fought the battle well and fought it alone". Polk hoped to gain Van Buren's support, hinting in a letter that a Van Buren/Polk ticket could carry Tennessee, but found him unconvinced.

The biggest political issue in the United States at that time was territorial expansion.]Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas (), or simply Texas, was a country in North America that existed for close to 10 years, from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846. Texas shared borders with Centralist Republic of Mexico, the Republic of the Rio Grande, an ...

had successfully revolted against Mexico in 1836. With the republic largely populated by American emigres, those on both sides of the Sabine River border between the U.S. and Texas deemed it inevitable that Texas would join the United States, but this would anger Mexico, which considered Texas a breakaway province, and threatened war if the United States annexed it. Jackson, as president, had recognized Texas independence, but the initial momentum toward annexation had stalled. Britain was seeking to expand her influence in Texas: Britain had abolished slavery, and if Texas did the same, it would provide a western haven for runaways to match one in the North. A Texas not in the United States would also stand in the way of what was deemed America's Manifest Destiny

Manifest destiny was the belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American pioneer, American settlers were destined to expand westward across North America, and that this belief was both obvious ("''m ...

to overspread the continent.

Clay was nominated for president by acclamation at the April 1844 Whig National Convention

The 1844 Whig National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held on May 1, 1844, at Universalist Church in Baltimore, Maryland. It nominated the Whig Party's candidates for president and vice president in the 1844 election. The ...

, with New Jersey's Theodore Frelinghuysen

Theodore Frelinghuysen (March 28, 1787April 12, 1862) was an American politician who represented New Jersey in the United States Senate. He was the Whig vice presidential nominee in the election of 1844, running on a ticket with Henry Clay.

...

his running mate. A Kentucky slaveholder at a time when opponents of Texas annexation

The Republic of Texas was annexation, annexed into the United States and Admission to the Union, admitted to the Union as the List of U.S. states by date of admission to the Union, 28th state on December 29, 1845.

The Republic of Texas Texas ...

argued that it would give slavery more room to spread, Clay sought a nuanced position on the issue. Jackson, who strongly supported a Van Buren/Polk ticket, was delighted when Clay issued a letter for publication in the newspapers opposing Texas annexation, only to be devastated when he learned Van Buren had done the same thing. Van Buren did this because he feared losing his base of support in the Northeast, but his supporters in the old Southwest

The "Old Southwest" is an informal name for the southwestern frontier territories of the United States from the American Revolutionary War , through the early 1800s, at which point the US had acquired the Louisiana Territory, pushing the sout ...

were stunned at his action. Polk, on the other hand, had written a pro-annexation letter that had been published four days before Van Buren's.[Leonard, pp. 36–37] Polk was at first startled, calling the plan "utterly abortive", but he agreed to accept it. Polk immediately wrote to instruct his lieutenants at the convention to work for his nomination as president.1844 Democratic National Convention

The 1844 Democratic National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held in Baltimore, Maryland from May 27 through 30. The convention nominated former Governor James K. Polk of Tennessee for president and former Senator George M. ...

in Baltimore, Gideon Johnson Pillow

Gideon Johnson Pillow (June 8, 1806October 8, 1878) was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army in the Western Theater of the American Civil War, having previously served as a general of United States Volunteers during the Mexican–Ame ...

, believed Polk could emerge as a compromise candidate. Publicly, Polk, who remained in Columbia during the convention, professed full support for Van Buren's candidacy and was believed to be seeking the vice presidency. Polk was one of the few major Democrats to have declared for the annexation of Texas.

The convention opened on May 27, 1844. A crucial question was whether the nominee needed two-thirds of the delegate vote, as had been the case at previous Democratic conventions, or merely a majority. A vote for two-thirds would doom Van Buren's candidacy due to opposition from southern delegates. With the support of the Southern states, the two-thirds rule was passed.[Merry, pp. 87–88] Van Buren won a majority on the first presidential ballot but failed to win the necessary two-thirds, and his support slowly faded.[ Cass, Johnson, Calhoun and ]James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

also received votes on the first ballot, and Cass took the lead on the fifth. After seven ballots, the convention remained deadlocked: Cass could not reach two-thirds, and Van Buren's supporters became discouraged about his chances. Delegates were ready to consider a new candidate who might break the stalemate.

When the convention adjourned after the seventh ballot, Pillow, who had been waiting for an opportunity to press Polk's name, conferred with George Bancroft

George Bancroft (October 3, 1800 – January 17, 1891) was an American historian, statesman and Democratic Party (United States), Democratic politician who was prominent in promoting secondary education both in his home state of Massachusetts ...

of Massachusetts, a politician and historian and longtime Polk correspondent, who had planned to nominate Polk for vice president. Bancroft had supported Van Buren's candidacy and was willing to see New York Senator Silas Wright

Silas Wright Jr. (May 24, 1795 – August 27, 1847) was an American attorney and Democratic politician. A member of the Albany Regency, he served as a member of the United States House of Representatives, New York State Comptroller, United Stat ...

head the ticket, but as a Van Buren loyalist, Wright would not consent. Pillow and Bancroft decided if Polk were nominated for president, Wright might accept the second spot. Before the eighth ballot, former Attorney General Benjamin F. Butler, head of the New York delegation, read a pre-written letter from Van Buren to be used if he could not be nominated, withdrawing in Wright's favor. But Wright (who was in Washington) had also entrusted a pre-written letter to a supporter, in which he refused to be considered as a presidential candidate, and stated in the letter that he agreed with Van Buren's position on Texas. Had Wright's letter not been read he most likely would have been nominated, but without him, Butler began to rally Van Buren supporters for Polk as the best possible candidate, and Bancroft placed Polk's name before the convention. On the eighth ballot, Polk received only 44 votes to Cass's 114 and Van Buren's 104, but the deadlock showed signs of breaking. Butler formally withdrew Van Buren's name, many delegations declared for the Tennessean, and on the ninth ballot, Polk received 233 ballots to Cass's 29, making him the Democratic nominee for president. The nomination was then made unanimous.telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

. Having declined by proxy an almost certain presidential nomination, Wright also refused the vice-presidential nomination. Senator Robert J. Walker

Robert James Walker (July 19, 1801November 11, 1869) was an American lawyer, economist and politician. An active member of the Democratic Party, he served as a member of the U.S. Senate from Mississippi from 1835 until 1845, as Secretary of t ...

of Mississippi, a close Polk ally, then suggested former senator George M. Dallas of Pennsylvania. Dallas was acceptable enough to all factions and gained the nomination on the third ballot. The delegates passed a platform and adjourned on May 30.

Many contemporary politicians, including Pillow and Bancroft, later claimed credit for getting Polk the nomination, but Walter R. Borneman

Walter R. Borneman (born January 5, 1952), is an American historian and lawyer. He is the author of well-known popular books on 18th and 19th century United States history.

Education

He received his B.A. in 1974 from Western State College of ...

felt that most of the credit was due to Jackson and Polk, "the two who had done the most were back in Tennessee, one an aging icon ensconced at the Hermitage and the other a shrewd lifelong politician waiting expectantly in Columbia". Whigs mocked Polk with the chant "Who is James K. Polk?", affecting never to have heard of him.[Merry, pp. 96–97] Though he had experience as Speaker of the House and Governor of Tennessee, all previous presidents had served as vice president, Secretary of State, or as a high-ranking general. Polk has been described as the first "dark horse

A dark horse is a previously lesser-known person, team or thing that emerges to prominence in a situation, especially in a competition involving multiple rivals, that is unlikely to succeed but has a fighting chance, unlike the underdog who is exp ...

" presidential nominee, although his nomination was less of a surprise than that of future nominees such as Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. A northern Democratic Party (United States), Democrat who believed that the Abolitionism in the United States, abolitio ...

or Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he was one of the most ...

. Despite his party's gibes, Clay recognized that Polk could unite the Democrats.[

]

General election

Rumors of Polk's nomination reached Nashville on June 4, much to Jackson's delight; they were substantiated later that day. The dispatches were sent on to Columbia, arriving the same day, and letters and newspapers describing what had happened at Baltimore were in Polk's hands by June 6. He accepted his nomination by letter dated June 12, alleging that he had never sought the office, and stating his intent to serve only one term. Wright was embittered by what he called the "foul plot" against Van Buren, and demanded assurances that Polk had played no part; it was only after Polk professed that he had remained loyal to Van Buren that Wright supported his campaign. Following the custom of the time that presidential candidates avoid electioneering or appearing to seek the office, Polk remained in Columbia and made no speeches. He engaged in extensive correspondence with Democratic Party officials as he managed his campaign. Polk made his views known in his acceptance letter and through responses to questions sent by citizens that were printed in newspapers, often by arrangement.

A potential pitfall for Polk's campaign was the issue of whether the tariff should be for revenue only, or with the intent to protect American industry. Polk finessed the tariff issue in a published letter. Recalling that he had long stated that tariffs should only be sufficient to finance government operations, he maintained that stance but wrote that within that limitation, government could and should offer "fair and just protection" to American interests, including manufacturers. He refused to expand on this stance, acceptable to most Democrats, despite the Whigs pointing out that he had committed himself to nothing. In September, a delegation of Whigs from nearby Giles County came to Columbia, armed with specific questions on Polk's views regarding the current tariff, the Whig-passed Tariff of 1842

The Tariff of 1842, or Black Tariff as it became known, was a protectionist tariff schedule adopted in the United States. It reversed the effects of the Compromise Tariff of 1833, which contained a provision that successively lowered the tariff ...

, and with the stated intent of remaining in Columbia until they got answers. Polk took several days to respond and chose to stand by his earlier statement, provoking an outcry in the Whig papers.

Another concern was the third-party candidacy of President Tyler, which might split the Democratic vote. Tyler had been nominated by a group of loyal officeholders. Under no illusions he could win, he believed he could rally states' rights supporters and populists to hold the balance of power in the election. Only Jackson had the stature to resolve the situation, which he did with two letters to friends in the Cabinet, that he knew would be shown to Tyler, stating that the President's supporters would be welcomed back into the Democratic fold. Jackson wrote that once Tyler withdrew, many Democrats would embrace him for his pro-annexation stance. The former president also used his influence to stop Francis Preston Blair

Francis Preston Blair Sr. (April 12, 1791 – October 18, 1876) was an American journalist, newspaper editor, and influential figure in national politics advising several U.S. presidents across party lines.

Blair was an early member of the D ...

and his ''Globe'' newspaper, the semi-official organ of the Democratic Party, from attacking Tyler. These proved enough; Tyler withdrew from the race in August.

Party troubles were a third concern. Polk and Calhoun made peace when a former South Carolina congressman, Francis Pickens visited Tennessee and came to Columbia for two days and to the Hermitage for sessions with the increasingly ill Jackson. Calhoun wanted the ''Globe'' dissolved, and that Polk would act against the 1842 tariff and promote Texas annexation. Reassured on these points, Calhoun became a strong supporter.

Polk was aided regarding Texas when Clay, realizing his anti-annexation letter had cost him support, attempted in two subsequent letters to clarify his position. These angered both sides, which attacked Clay as insincere. Texas also threatened to divide the Democrats sectionally, but Polk managed to appease most Southern party leaders without antagonizing Northern ones.[Merry, pp. 107–108] As the election drew closer, it became clear that most of the country favored the annexation of Texas, and some Southern Whig leaders supported Polk's campaign due to Clay's anti-annexation stance.[

] The campaign was vitriolic; both major party candidates were accused of various acts of malfeasance; Polk was accused of being both a duelist and a coward. The most damaging smear was the Roorback forgery; in late August an item appeared in an

The campaign was vitriolic; both major party candidates were accused of various acts of malfeasance; Polk was accused of being both a duelist and a coward. The most damaging smear was the Roorback forgery; in late August an item appeared in an abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

newspaper, part of a book detailing fictional travels through the South of a Baron von Roorback, an imaginary German nobleman. The Ithaca ''Chronicle'' printed it without labeling it as fiction, and inserted a sentence alleging that the traveler had seen forty slaves who had been sold by Polk after being branded with his initials. The item was withdrawn by the ''Chronicle'' when challenged by the Democrats, but it was widely reprinted. Borneman suggested that the forgery backfired on Polk's opponents as it served to remind voters that Clay too was a slaveholder. John Eisenhower

John Sheldon Doud Eisenhower (August 3, 1922 – December 21, 2013) was a United States Army officer, diplomat, and military historian. He was the second son of President Dwight D. Eisenhower and First Lady Mamie Eisenhower. His military ca ...

, in his journal article on the election, stated that the smear came too late to be effectively rebutted, and likely cost Polk Ohio. Southern newspapers, on the other hand, went far in defending Polk, one Nashville newspaper alleging that his slaves preferred their bondage to freedom. Polk himself implied to newspaper correspondents that the only slaves he owned had either been inherited or had been purchased from relatives in financial distress; this paternalistic image was also painted by surrogates like Gideon Pillow. This was not true, though not known at the time; by then he had bought over thirty slaves, both from relatives and others, mainly for the purpose of procuring labor for his Mississippi cotton plantation.

There was no uniform election day in 1844; states voted between November 1 and 12.[Borneman, p. 125] Polk won the election with 49.5% of the popular vote and 170 of the 275 electoral votes.[Merry, pp. 109–111] Becoming the first president elected despite losing his state of residence (Tennessee),[

]

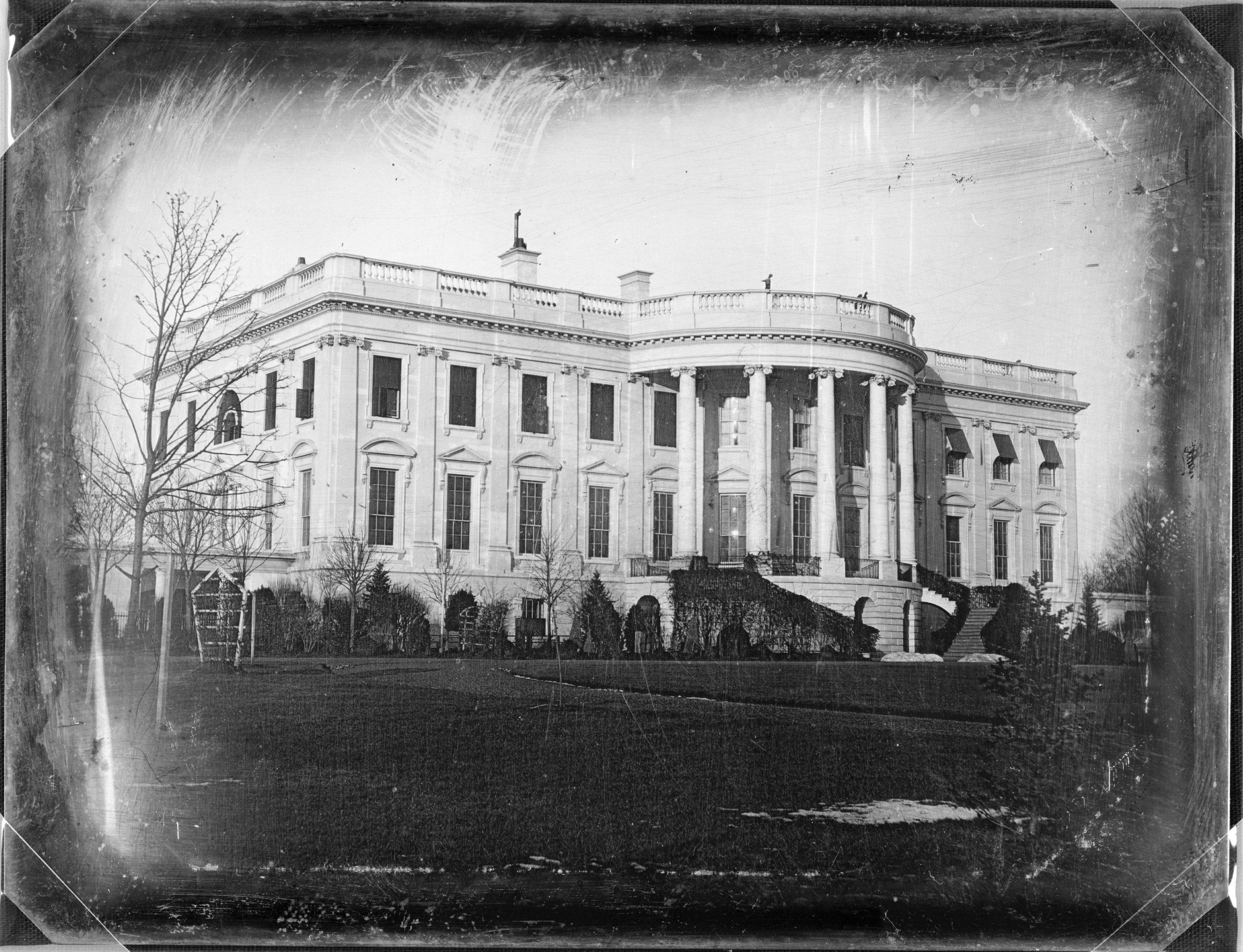

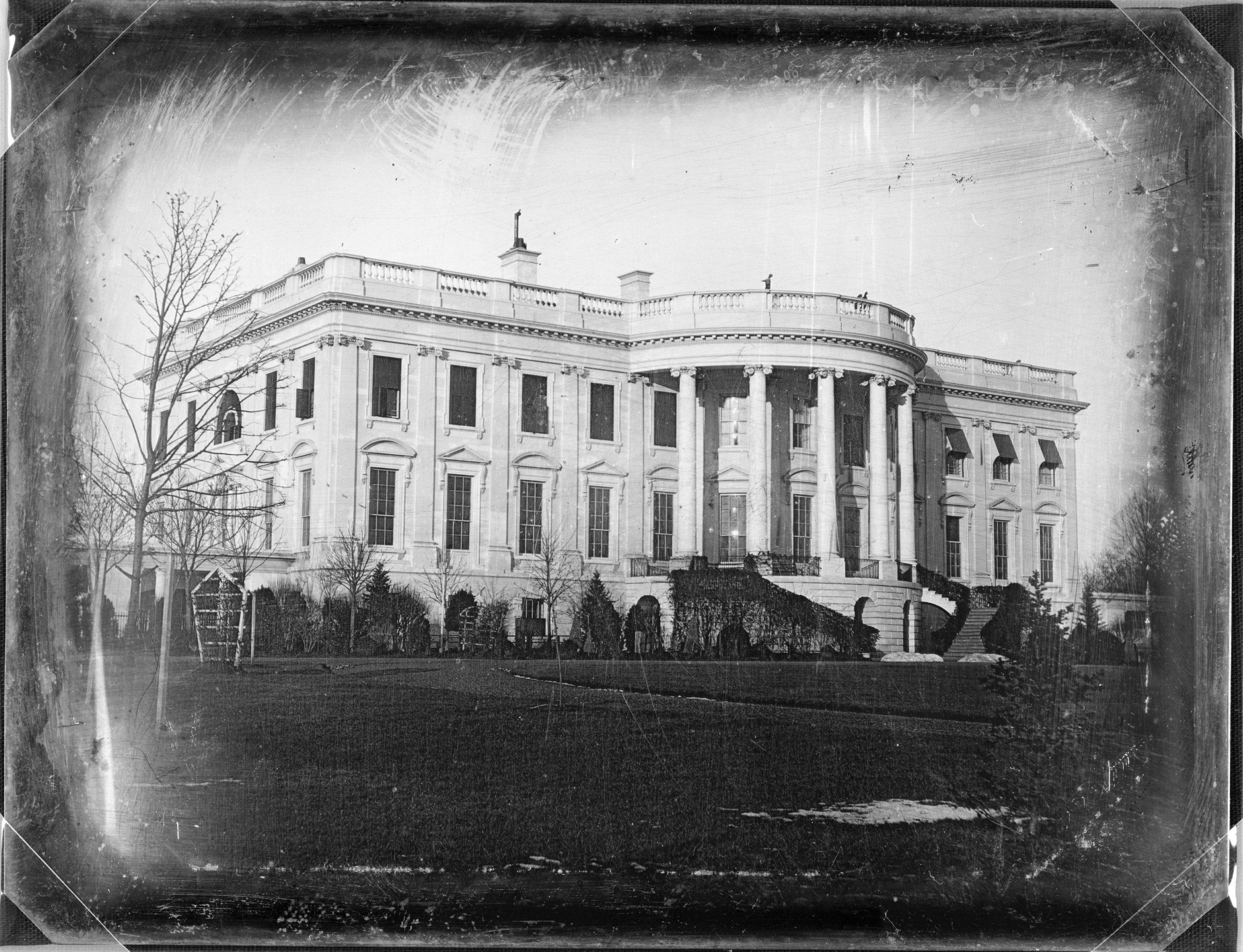

Presidency (1845–1849)

With a slender victory in the popular vote, but with a greater victory in the

With a slender victory in the popular vote, but with a greater victory in the Electoral College

An electoral college is a body whose task is to elect a candidate to a particular office. It is mostly used in the political context for a constitutional body that appoints the head of state or government, and sometimes the upper parliament ...

(170–105), Polk proceeded to implement his campaign promises. He presided over a country whose population had doubled every twenty years since the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

and which had reached demographic parity with Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

.[Merry, pp. 132–133] During Polk's tenure, technological advancements persisted, including the continued expansion of railroads and increased use of the telegraph.[ These improvements in communication encouraged a zest for ]expansionism

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military Imperialism, empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established p ...

.[ However, sectional divisions became worse during his tenure.

Polk set four clearly defined goals for his administration:][Merry, pp. 131–132]

* Reestablish the Independent Treasury System

The Independent Treasury was the system for managing the money supply of the United States federal government through the U.S. Treasury and its sub-treasuries, independently of the national banking and financial systems. It was created on August 6, ...

the Whigs had abolished the one created under Van Buren.

* Reduce tariffs

A tariff or import tax is a duty imposed by a national government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods or raw materials and is ...

.

* Acquire some or all of the Oregon Country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long Oregon boundary dispute, dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been demarcat ...

.

* Acquire California and its harbors from Mexico.

While his domestic aims represented continuity with past Democratic policies, successful completion of Polk's foreign policy goals would represent the first major American territorial gains since the Adams–Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty () of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Spanish Cession, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty,Weeks, p. 168. was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to ...

of 1819.[

]

Transition, inauguration and appointments

Polk formed a geographically balanced Cabinet.[Merry, pp. 112–113] He consulted Jackson and one or two other close allies, and decided that the large states of New York, Pennsylvania and Virginia should have representation in the six-member Cabinet, as should his home state of Tennessee. At a time when an incoming president might retain some or all of his predecessor's department heads, Polk wanted an entirely fresh Cabinet, but this proved delicate. Tyler's final Secretary of State was Calhoun, leader of a considerable faction of the Democratic Party, but, when approached by emissaries, he did not take offense and was willing to step down.James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

of Pennsylvania, whose ambition for the presidency was well-known, as Secretary of State.[Merry, pp. 114–117] Tennessee's Cave Johnson

Cave Johnson (January 11, 1793 – November 23, 1866) was an American politician who served the state of Tennessee as a Democratic congressman in the United States House of Representatives. Johnson was the 12th United States Postmaster Gener ...

, a close friend and ally of Polk, was nominated for the position of Postmaster General, with George Bancroft, the historian who had played a crucial role in Polk's nomination, as Navy Secretary. Polk's choices met with the approval of Andrew Jackson, with whom Polk met for the last time in January 1845, as Jackson died that June.[Merry, pp. 117–119]

Tyler's last Navy Secretary, John Y. Mason

John Young Mason (April 18, 1799October 3, 1859) was an attorney, planter, judge and politician from Virginia. Mason served in the U.S. House of Representatives after serving in both houses of the Virginia General Assembly, then became the Unit ...

of Virginia, Polk's friend since college days and a longtime political ally, was not on the original list. As Cabinet choices were affected by factional politics and President Tyler's drive to resolve the Texas issue before leaving office, Polk at the last minute chose Mason as Attorney General.[Bergeron, pp. 23–25] Polk also chose Mississippi Senator Walker as Secretary of the Treasury and New York's William Marcy as Secretary of War. The members worked well together, and few replacements were necessary. One reshuffle was required in 1846 when Bancroft, who wanted a diplomatic posting, became U.S. minister to Britain.

In his last days in office, President Tyler sought to complete the annexation of Texas. After the Senate had defeated an earlier treaty that required a two-thirds majority, Tyler urged Congress to pass a joint resolution, relying on its constitutional power to admit states.[Merry, pp. 120–124] There were disagreements about the terms under which Texas would be admitted and Polk became involved in negotiations to break the impasse. With Polk's help, the annexation resolution narrowly cleared the Senate.[ Tyler was unsure whether to sign the resolution or leave it for Polk and sent Calhoun to consult with Polk, who declined to give any advice. On his final evening in office, March 3, 1845, Tyler offered annexation to Texas according to the terms of the resolution.

Even before his inauguration, Polk wrote to Cave Johnson, "I intend to be President of the U.S." He would gain a reputation as a hard worker, spending ten to twelve hours at his desk, and rarely leaving Washington. Polk wrote, "No President who performs his duty faithfully and conscientiously can have any leisure. I prefer to supervise the whole operations of the government myself rather than intrust the public business to subordinates, and this makes my duties very great."]The Illustrated London News

''The Illustrated London News'', founded by Herbert Ingram and first published on Saturday 14 May 1842, was the world's first illustrated weekly news magazine. The magazine was published weekly for most of its existence, switched to a less freq ...

'').

In his inaugural address, delivered in a steady rain, Polk made clear his support for Texas annexation by referring to the 28 states of the U.S., thus including Texas. He proclaimed his fidelity to Jackson's principles by quoting his famous toast, "Every lover of his country must shudder at the thought of the possibility of its dissolution and will be ready to adopt the patriotic sentiment, 'Our Federal Union—it must be preserved.'" He stated his opposition to a national bank, and repeated that the tariff could include incidental protection. Although he did not mention slavery specifically, he alluded to it, decrying those who would tear down an institution protected by the Constitution.

Polk devoted the second half of his speech to foreign affairs, and specifically to expansion. He applauded the annexation of Texas, warning that Texas was no affair of any other nation, and certainly none of Mexico's. He spoke of the Oregon Country, and of the many who were migrating, pledging to safeguard America's rights there and to protect the settlers.

As well as appointing Cabinet officers to advise him, Polk made his sister's son, J. Knox Walker, his personal secretary

''Personal Secretary'' is a 1938 American comedy film directed by Otis Garrett and written by Betty Laidlaw, Robert Lively and Charles Grayson. The film stars William Gargan, Joy Hodges, Andy Devine, Ruth Donnelly, Samuel S. Hinds and Fran ...

, an especially important position because, other than his slaves, Polk had no staff at the White House. Walker, who lived at the White House with his growing family (two children were born to him while living there), performed his duties competently through his uncle's presidency. Other Polk relatives visited at the White House, some for extended periods.

Foreign policy

Partition of Oregon Country

Britain and the U.S. each derived claims to the Oregon Country from the voyages of explorers. Russia and Spain had waived their weak claims. Claims of the indigenous peoples of the region to their traditional lands were not a factor.

Rather than war over the distant and unsettled territory, Washington and London negotiated amicably. Previous U.S. administrations had offered to divide the region along the 49th parallel, which was not acceptable to Britain, as it had commercial interests along the Columbia River.

Rather than war over the distant and unsettled territory, Washington and London negotiated amicably. Previous U.S. administrations had offered to divide the region along the 49th parallel, which was not acceptable to Britain, as it had commercial interests along the Columbia River.[Merry, pp. 168–169] Britain's preferred partition was unacceptable to Polk, as it would have awarded Puget Sound

Puget Sound ( ; ) is a complex estuary, estuarine system of interconnected Marine habitat, marine waterways and basins located on the northwest coast of the U.S. state of Washington (state), Washington. As a part of the Salish Sea, the sound ...

and all lands north of the Columbia River to Britain, and Britain was unwilling to accept the 49th parallel extended to the Pacific, as it meant the entire opening to Puget Sound would be in American hands, isolating its settlements along the Fraser River

The Fraser River () is the longest river within British Columbia, Canada, rising at Fraser Pass near Blackrock Mountain (Canada), Blackrock Mountain in the Rocky Mountains and flowing for , into the Strait of Georgia just south of the City of V ...

.[

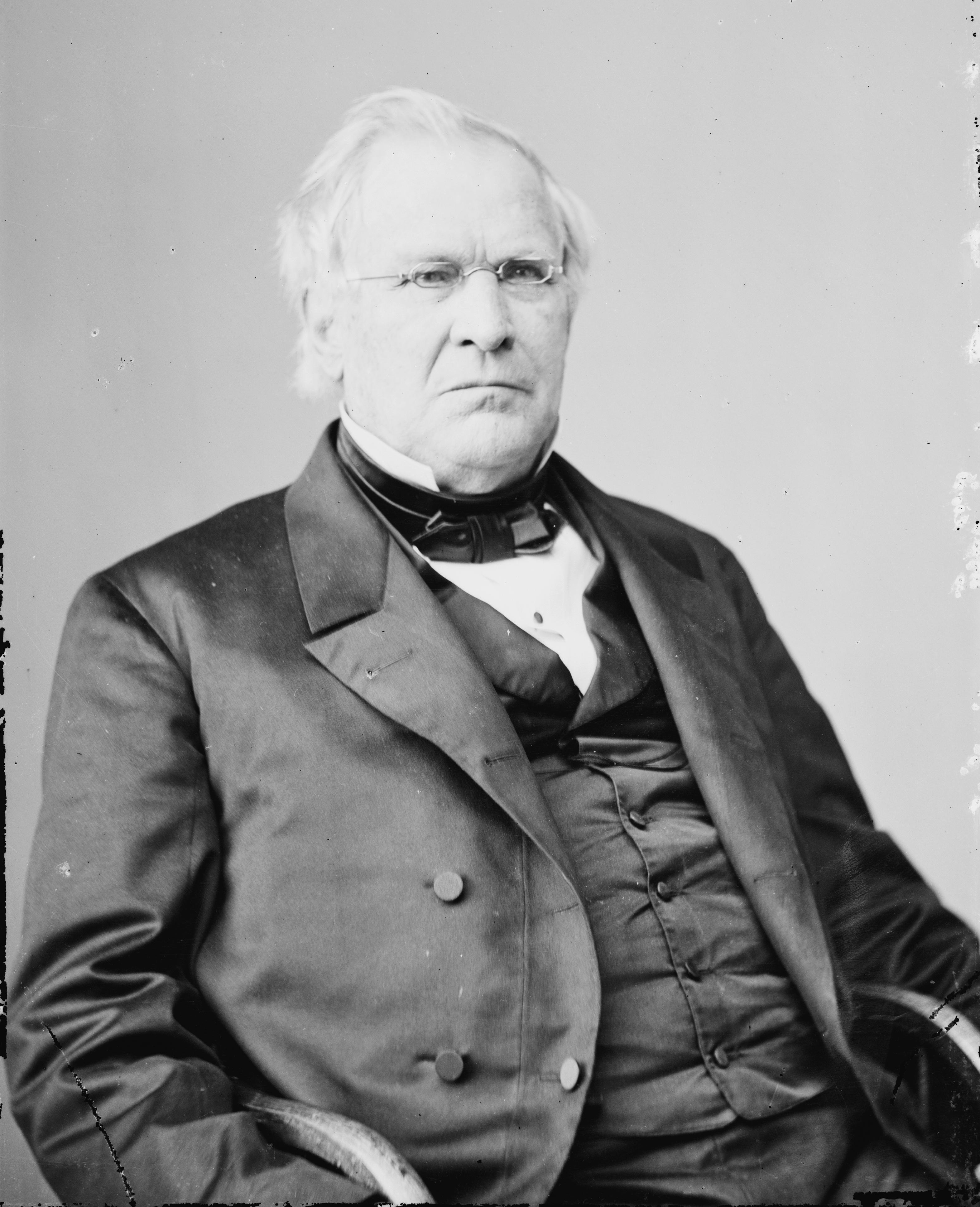

]Edward Everett

Edward Everett (April 11, 1794 – January 15, 1865) was an American politician, Unitarian pastor, educator, diplomat, and orator from Massachusetts. Everett, as a Whig, served as U.S. representative, U.S. senator, the 15th governor of Mas ...

, Tyler's minister in London, had informally proposed dividing the territory at the 49th parallel with the strategic Vancouver Island

Vancouver Island is an island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean and part of the Canadian province of British Columbia. The island is in length, in width at its widest point, and in total area, while are of land. The island is the largest ...

granted to the British, thus allowing an opening to the Pacific. But when the new British minister in Washington, Richard Pakenham

Sir Richard Pakenham PC (19 May 1797 – 28 October 1868) was a British diplomat of Anglo-Irish background. He served as British Ambassador to the United States from 1843 until 1847, during which time he unsuccessfully worked to prevent t ...

arrived in 1844 prepared to follow up, he found that many Americans desired the entire territory, which extended north to 54 degrees, 40 minutes north latitude. Oregon had not been a major issue in the 1844 election, but the heavy influx of settlers, mostly American, to the Oregon Country in 1845, and the rising spirit of expansionism in the U.S. as Texas and Oregon seized the public's eye, made a treaty with Britain more urgent. Many Democrats believed the U.S. should span from coast to coast, a philosophy called Manifest Destiny