William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

, serving from 1897 until

his assassination in 1901. A member of the

Republican Party, he led a realignment that made Republicans

largely dominant in the industrial states and nationwide for decades. McKinley successfully led the U.S. in the

Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

and oversaw a period of

American expansionism

Manifest destiny was the belief in the 19th-century United States that American settlers were destined to expand westward across North America, and that this belief was both obvious ("''manifest''") and certain ("''destiny''"). The belief ...

, with the annexations of

Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; ) is an island U.S. state, state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two Non-contiguous United States, non-contiguous U.S. states (along with Alaska), it is the only sta ...

,

Puerto Rico

; abbreviated PR), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, is a Government of Puerto Rico, self-governing Caribbean Geography of Puerto Rico, archipelago and island organized as an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territo ...

,

Guam

Guam ( ; ) is an island that is an Territories of the United States, organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. Guam's capital is Hagåtña, Guam, Hagåtña, and the most ...

, the

Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

, and

American Samoa

American Samoa is an Territories of the United States, unincorporated and unorganized territory of the United States located in the Polynesia region of the Pacific Ocean, South Pacific Ocean. Centered on , it is southeast of the island count ...

.

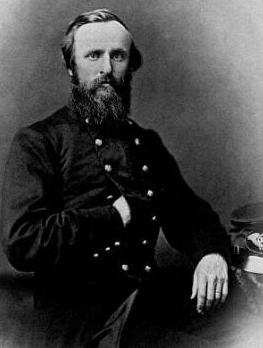

McKinley was the last president to have served in the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

; he was the only one to begin his service as an

enlisted man and ended it as a

brevet major. After the war, he settled in

Canton, Ohio

Canton () is a city in Stark County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of cities in Ohio, eighth-most populous city in Ohio, with a population of 70,872 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. The Canton–Massillo ...

, where he practiced law and married

Ida Saxton. In 1876, McKinley was elected to Congress, where he became the Republican expert on the

protective tariff

Protective tariffs are tariffs that are enacted with the aim of protecting a domestic industry. They aim to make imported goods cost more than equivalent goods produced domestically, thereby causing sales of domestically produced goods to rise, ...

, believing

protectionism

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations ...

would bring prosperity. His 1890

McKinley Tariff

The Tariff Act of 1890, commonly called the McKinley Tariff, was an act of the United States Congress framed by then-Representative William McKinley, that became law on October 1, 1890. The tariff raised the average duty on imports to almost 50% ...

was highly controversial and, together with a

Democratic redistricting aimed at

gerrymandering

Gerrymandering, ( , originally ) defined in the contexts of Representative democracy, representative electoral systems, is the political manipulation of Boundary delimitation, electoral district boundaries to advantage a Political party, pa ...

him out of office, led to his defeat in the

Democratic landslide of 1890. He was elected

governor of Ohio

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the type of political region or polity, a ''governor'' ma ...

in 1891 and 1893, steering a moderate course between capital and labor interests.

McKinley

secured the Republican nomination for president in 1896 amid a deep economic depression and defeated his Democratic rival

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator, and politician. He was a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running three times as the party' ...

after a

front porch campaign

A front porch campaign is a low-key electoral campaign used in American politics in which the candidate remains close to or at home where they issue written statements and give speeches to supporters who come to visit. The candidate largely doe ...

in which he advocated "

sound money

In macroeconomics, hard currency, safe-haven currency, or strong currency is any globally traded currency that serves as a reliable and stable store of value. Factors contributing to a currency's ''hard'' status might include the stability and r ...

" (the gold standard unless altered by international agreement) and promised that high tariffs would restore prosperity.

McKinley's presidency saw rapid economic growth. He rejected

free silver in favor of keeping the nation on the

gold standard

A gold standard is a backed currency, monetary system in which the standard economics, economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the ...

, and raised

protective tariff

Protective tariffs are tariffs that are enacted with the aim of protecting a domestic industry. They aim to make imported goods cost more than equivalent goods produced domestically, thereby causing sales of domestically produced goods to rise, ...

s, signing the

Dingley Tariff of 1897 to protect manufacturers and factory workers from foreign competition and securing the passage of the

Gold Standard Act of 1900.

McKinley's foreign policy emulated the era's

overseas imperialism of the

great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power ...

s in

Oceania

Oceania ( , ) is a region, geographical region including Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Outside of the English-speaking world, Oceania is generally considered a continent, while Mainland Australia is regarded as its co ...

,

Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

, and the

Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere, located south of the Gulf of Mexico and southwest of the Sargasso Sea. It is bounded by the Greater Antilles to the north from Cuba ...

. The United States

annexed

Annexation, in international law, is the forcible acquisition and assertion of legal title over one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. In current international law, it is generally held to ...

the independent

Republic of Hawaii

The Republic of Hawaii (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ''Lepupalika o Hawaii'' epupəˈlikə o həˈvɐjʔi was a short-lived one-party state in Hawaii, Hawaii between July 4, 1894, when the Provisional Government of Hawaii had Black Week (H ...

in 1898, and it became the

Territory of Hawaii

The Territory of Hawaii or Hawaii Territory (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ''Panalāʻau o Hawaiʻi'') was an organized incorporated territories of the United States, organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from Apri ...

in 1900. McKinley hoped to persuade

Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

to grant independence to rebellious

Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

without conflict. Still, when negotiations failed, he requested and signed Congress's declaration of war to begin the Spanish-American War of 1898, in which the United States saw a quick and decisive victory. As part of

the peace settlement, Spain turned over to the United States its main overseas colonies of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines, while Cuba was promised independence but remained under the control of the United States Army until May 20, 1902. In the Philippines,

a pro-independence rebellion began; it was eventually suppressed. McKinley acquired what is now American Samoa when his administration partitioned the

Samoan Islands

The Samoan Islands () are an archipelago covering in the central Pacific Ocean, South Pacific, forming part of Polynesia and of the wider region of Oceania. Political geography, Administratively, the archipelago comprises all of the Samoa, Indep ...

with the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and the

German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

in the

Tripartite Convention

The Tripartite Convention of 1899 concluded the Second Samoan Civil War, resulting in the formal partition of the Samoan archipelago into a German colony and a United States territory.

Forerunners to the Tripartite Convention of 1899 were the ...

, during a period of warming ties between the UK and US known as the

Great Rapprochement

The Great Rapprochement was the convergence of diplomatic, political, military, and economic objectives of the United States and Great Britain from 1895 to 1915, the two decades before American entry into World War I as an ally against Germany. ...

.

McKinley defeated Bryan again in the

1900 presidential election in a campaign focused on

imperialism

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of Power (international relations), power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power (diplomatic power and cultura ...

,

protectionism

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations ...

, and free silver. His second term ended early when he was shot on September 6, 1901, by

Leon Czolgosz

Leon Frank Czolgosz ( ; ; May 5, 1873 – October 29, 1901) was an American wireworker and Anarchism, anarchist who assassination of William McKinley, assassinated President of the United States, United States president William McKinley on Septe ...

, an

anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

. McKinley died eight days later and was succeeded by Vice President

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

. Historians regard McKinley's 1896 victory as a

realigning election

A political realignment is a set of sharp changes in party-related ideology, issues, leaders, regional bases, demographic bases, and/or the structure of powers within a government. In the fields of political science and political history, this is ...

in which

the political stalemate of the post-Civil War era gave way to the Republican-dominated

Fourth Party System

The Fourth Party System was the political party system in the United States from about 1896 to 1932 that was dominated by the Republican Party, except the 1912 split in which Democrats captured the White House and held it for eight years.

Am ...

, beginning with the

Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (1890s–1920s) was a period in the United States characterized by multiple social and political reform efforts. Reformers during this era, known as progressivism in the United States, Progressives, sought to address iss ...

. The United States retains control over the major territories McKinley annexed, aside from the Philippines which became

independent in 1946.

Early life and family

William McKinley Jr. was born in 1843 in

Niles, Ohio

Niles is a city in Trumbull County, Ohio, United States. The population was 18,443 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Located at the confluence of the Mahoning River and Mosquito Creek Lake, Mosquito Creek, Niles is a suburb in the Ma ...

, the seventh of nine children of

William McKinley Sr. and Nancy (née Allison) McKinley. The McKinleys were of

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Culture, language and peoples

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

* ''English'', an Amish ter ...

and

Scots-Irish descent and had settled in western Pennsylvania in the 18th century. Their immigrant ancestor was David McKinley, born in

Dervock

Dervock ( or ''Dairbheog'') is a small village and townland (of 132 acres) in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It is about 3.5 miles (6 km) northeast of Ballymoney, on the banks of the River Bush. It is situated in the civil parish of D ...

, County Antrim, in present-day

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

. William McKinley Sr. was born in Pennsylvania, in

Pine Township, Mercer County.

The family moved to Ohio when the senior McKinley was a boy, settling in

New Lisbon (now Lisbon). He met Nancy Allison there, and they married later. The Allison family was of mostly English descent and among Pennsylvania's earliest settlers. The family trade on both sides was iron making. McKinley senior operated

foundries

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals pr ...

throughout Ohio, in New Lisbon, Niles,

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, and finally

Canton

Canton may refer to:

Administrative divisions

* Canton (administrative division), territorial/administrative division in some countries

* Township (Canada), known as ''canton'' in Canadian French

Arts and entertainment

* Canton (band), an It ...

. The McKinley household was, like many from Ohio's

Western Reserve

The Connecticut Western Reserve was a portion of land claimed by the Colony of Connecticut and later by the state of Connecticut in what is now mostly the northeastern region of Ohio. Warren, Ohio was the Historic Capital in Trumbull County. T ...

, steeped in

Whiggish and

abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

sentiment, the latter based on the family's staunch

Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a Protestant Christianity, Christian Christian tradition, tradition whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother ...

beliefs.

The younger William also followed in the Methodist tradition, becoming active in

the local Methodist church at the age of sixteen. He was a lifelong pious Methodist.

In 1852, the family moved from Niles to Poland, Ohio, so that their children could attend its better schools. Graduating from

Poland Seminary

Poland Seminary, originally Poland Academy, was a name used for a series of schools operated in Poland, Ohio.

First academy

The original Poland Academy was created in 1830 by a Presbyterian minister named Bradley (first name unknown), in a room o ...

in 1859, McKinley enrolled the following year at

Allegheny College

Allegheny College is a private liberal arts college in Meadville, Pennsylvania, United States. Founded in 1815, Allegheny is the oldest college in continuous existence under the same name west of the Allegheny Mountains. It is a member of the G ...

in

Meadville, Pennsylvania

Meadville is a city in Crawford County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. The population was 13,050 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census. The first permanent settlement in Northwestern Pennsylvania, Meadville is withi ...

. He was an honorary member of the

Sigma Alpha Epsilon

Sigma Alpha Epsilon () is a North American Greek-letter social college fraternity. It was founded at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, on March 9, 1856.Baird, William Raimond, ed. (1905).Baird's Manual of American College Fratern ...

fraternity. He remained at Allegheny for one year, returning home in 1860 after becoming ill and depressed. He also studied at Mount Union College, now the

University of Mount Union

The University of Mount Union is a private liberal arts university in Alliance, Ohio, United States. Founded in 1846, the university was affiliated with the Methodist Church until 2019. It had an enrollment of 2,100 students as of 2023.

History ...

, in

Alliance, Ohio

Alliance is a city in Stark County, Ohio, United States. The population was 21,672 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. It was established in 1854 by the merger of three smaller communities and was a manufacturing and railroad hub in t ...

, where he later served as a member of the board of trustees. Although his health recovered, family finances declined, and McKinley was unable to return to Allegheny. He began working as a postal clerk and later took a job teaching at a school near Poland, Ohio.

Civil War

Western Virginia and Antietam

When the Confederate states seceded and the American Civil War began in 1861, thousands of men in Ohio volunteered for service. Among them were McKinley and his cousin William McKinley Osbourne, who enlisted as privates in the newly formed Poland Guards in June 1861. The men left for

Columbus

Columbus is a Latinized version of the Italian surname "''Colombo''". It most commonly refers to:

* Christopher Columbus (1451–1506), the Italian explorer

* Columbus, Ohio, the capital city of the U.S. state of Ohio

* Columbus, Georgia, a city i ...

where they were consolidated with other small units to form the

23rd Ohio Infantry

The 23rd Ohio Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment in the Union Army during much of the American Civil War. It served in the Eastern Theater in a variety of campaigns and battles, and is remembered with a stone memorial on the Antietam Na ...

.

The men were unhappy to learn that, unlike Ohio's earlier volunteer regiments, they would not be permitted to elect their officers; these would be designated by Ohio's governor,

William Dennison. Dennison appointed Colonel

William Rosecrans

William Starke Rosecrans (September 6, 1819March 11, 1898) was an American inventor, coal-oil company executive, diplomat, politician, and U.S. Army officer. He gained fame for his role as a Union general during the American Civil War. He was ...

as the commander of the regiment, and the men began training on the outskirts of Columbus. McKinley quickly took to the soldier's life: he wrote a series of letters to his hometown newspaper extolling

the army and the

Union cause. Delays in issuance of uniforms and weapons again brought the men into conflict with their officers, but

Major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was the 19th president of the United States, serving from 1877 to 1881.

Hayes served as Cincinnati's city solicitor from 1858 to 1861. He was a staunch Abolitionism in the Un ...

convinced them to accept what the government had issued them; his style in dealing with the men impressed McKinley, beginning an association and friendship that would last until Hayes's death in 1893.

After a month of training, McKinley and the 23rd Ohio, now led by Colonel

Eliakim P. Scammon, set out for western Virginia (today part of West Virginia) in July 1861 as a part of the

Kanawha Division

The Kanawha Division was a Union Army division (military), division which could trace its origins back to a brigade originally commanded by Jacob D. Cox. This division served in western Virginia and Maryland and was at times led by such famous pe ...

. McKinley initially thought Scammon was a

martinet

The martinet () is a punitive device traditionally used in France and other parts of Europe. The word also has other usages, described below.

Object

A martinet is a short, scourge-like (multi-tail) type of whip made of a wooden handle of about ...

, but when the regiment entered battle, he came to appreciate the value of their relentless drilling. Their first contact with the enemy came in September when they drove back Confederate troops at

Carnifex Ferry in present-day West Virginia. Three days after the battle, McKinley was assigned to duty in the

brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military unit, military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute ...

quartermaster

Quartermaster is a military term, the meaning of which depends on the country and service. In land army, armies, a quartermaster is an officer who supervises military logistics, logistics and requisitions, manages stores or barracks, and distri ...

office, where he worked both to supply his regiment, and as a clerk. In November, the regiment established winter quarters near

Fayetteville (today in West Virginia). McKinley spent the winter substituting for a commissary

sergeant

Sergeant (Sgt) is a Military rank, rank in use by the armed forces of many countries. It is also a police rank in some police services. The alternative spelling, ''serjeant'', is used in The Rifles and in other units that draw their heritage f ...

who was ill, and in April 1862 he was promoted to that rank. The regiment resumed its advance that spring with Hayes in command (Scammon led the brigade) and fought several minor engagements against the rebel forces.

That September, McKinley's regiment was called east to reinforce General

John Pope's

Army of Virginia

The Army of Virginia was organized as a major unit of the Union Army and operated briefly and unsuccessfully in 1862 in the American Civil War. It should not be confused with its principal opponent, the Confederate Army of ''Northern'' Virginia ...

at the

Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confederate ...

. Delayed in passing through Washington, D.C., the 23rd Ohio did not arrive in time for the battle but joined the

Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the primary field army of the Union army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the Battle of ...

as it hurried north to cut off Robert E. Lee's

Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was a field army of the Confederate States Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most often arrayed agains ...

as it advanced into Maryland. The 23rd was the first regiment to encounter the Confederates at the

Battle of South Mountain

The Battle of South Mountain, known in several early Southern United States, Southern accounts as the Battle of Boonsboro Gap, was fought on September 14, 1862, as part of the Maryland campaign of the American Civil War. Three pitched battles ...

on September 14. After severe losses, Union forces drove back the Confederates and continued to

Sharpsburg, Maryland, where they engaged Lee's army at the

Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam ( ), also called the Battle of Sharpsburg, particularly in the Southern United States, took place during the American Civil War on September 17, 1862, between Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virgi ...

, one of the bloodiest battles of the war. The 23rd was in the thick of the fighting at Antietam, and McKinley came under heavy fire when bringing rations to the men on the line. McKinley's regiment suffered many casualties, but the Army of the Potomac was victorious, and the Confederates retreated into Virginia. McKinley's regiment was detached from the Army of the Potomac and returned by train to western Virginia.

Shenandoah Valley and promotion

While the regiment went into winter quarters near

Charleston, Virginia (present-day West Virginia), McKinley was ordered back to Ohio with some other sergeants to recruit fresh troops. When they arrived in Columbus, Governor

David Tod

David Tod (February 21, 1805 – November 13, 1868) was an American politician and industrialist from the U.S. state of Ohio. As the 25th governor of Ohio, Tod gained recognition for his forceful and energetic leadership during the American Civil ...

surprised McKinley with a commission as

second lieutenant in recognition of his service at Antietam. McKinley and his comrades saw little action until July 1863, when the division skirmished with

John Hunt Morgan

John Hunt Morgan (June 1, 1825September 4, 1864) was a Confederate general in the American Civil War. In April 1862, he raised the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry Regiment, fought at Shiloh, and then launched a costly raid in Kentucky, which encouraged Br ...

's cavalry at the

Battle of Buffington Island

The Battle of Buffington Island, also known as the St. Georges Creek Skirmish, was an American Civil War engagement in Meigs County, Ohio, and Jackson County, West Virginia, on July 19, 1863, during Morgan's Raid. The largest battle in Ohio d ...

. Early in 1864, the Army command structure in West Virginia was reorganized, and the division was assigned to

George Crook

George R. Crook (September 8, 1828 – March 21, 1890) was a career United States Army officer who served in the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. He is best known for commanding U.S. forces in the Geronimo Campaign, 1886 campaign that ...

's

Army of West Virginia

The Army of West Virginia served in the Union Army during the American Civil War and was the primary field army of the Department of West Virginia. It campaigned primarily in West Virginia, Southwest Virginia and in the Shenandoah Valley. It is no ...

. They soon resumed the offensive, marching into southwestern Virginia to destroy salt and lead mines used by the enemy. On May 9, the army engaged Confederate troops at

Cloyd's Mountain, where the men charged the enemy entrenchments and drove the rebels from the field. McKinley later said the combat there was "as desperate as any witnessed during the war". Following the rout, the Union forces destroyed Confederate supplies and skirmished with the enemy again successfully.

McKinley and his regiment moved to the

Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the eastern panhandle of West Virginia in the United States. The Valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the east ...

as the armies broke from winter quarters to

resume hostilities. Crook's corps was attached to

Major General David Hunter

David Hunter (July 21, 1802 – February 2, 1886) was an American military officer. He served as a Union general during the American Civil War. He achieved notability for his unauthorized 1862 order (immediately rescinded) emancipating slaves ...

's

Army of the Shenandoah and soon back in contact with Confederate forces, capturing

Lexington, Virginia

Lexington is an Independent city (United States)#Virginia, independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia, United States. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 7,320. It is the county seat of Rockbridge County, Virg ...

, on June 11. They continued south toward

Lynchburg, tearing up railroad track as they advanced. Hunter believed the troops at Lynchburg were too powerful, however, and the brigade returned to West Virginia. Before the army could make another attempt, Confederate General

Jubal Early

Jubal Anderson Early (November 3, 1816 – March 2, 1894) was an American lawyer, politician and military officer who served in the Confederate States Army during the Civil War. Trained at the United States Military Academy, Early resigned his ...

's raid into Maryland forced their recall to the north.

Early's army surprised them at

Kernstown on July 24, where McKinley came under heavy fire and the army was defeated. Retreating into Maryland, the army was reorganized again: Major General

Philip Sheridan

Philip Henry Sheridan (March 6, 1831 – August 5, 1888) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close association with General-i ...

replaced Hunter, and McKinley, who had been promoted to

captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

after the battle, was transferred to General Crook's staff. By August, Early was retreating south in the valley, with Sheridan's army in pursuit. They fended off a Confederate assault at

Berryville, where McKinley had a horse shot out from under him, and advanced to

Opequon Creek

Opequon Creek (historically also Opecken) is an approximately 35 mile U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed August 15, 2011 tributary stream of the Potomac River. It flows into ...

, where they broke the enemy lines and pursued them farther south. They followed up the victory with another at

Fisher's Hill on September 22 and were engaged once more at

Cedar Creek on October 19. After initially falling back from the Confederate advance, McKinley helped to rally the troops and turn the tide of the battle.

After Cedar Creek, the army stayed in the vicinity through election day, when McKinley cast his first presidential ballot, for the incumbent Republican,

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

. The next day, they moved north up the valley into winter quarters near Kernstown. In February 1865, Crook was captured by Confederate raiders. Crook's capture added to the confusion as the army was reorganized for the spring campaign, and McKinley served on the staffs of four different generals over the next fifteen days—Crook,

John D. Stevenson,

Samuel S. Carroll

Samuel Sprigg "Red" Carroll (September 21, 1832 – January 28, 1893) was a career officer in the United States Army who rose to the rank of brigadier general of the Union during the American Civil War. The Maryland native was most known fo ...

, and

Winfield S. Hancock. Finally assigned to Carroll's staff again, McKinley acted as the general's first and only

adjutant

Adjutant is a military appointment given to an Officer (armed forces), officer who assists the commanding officer with unit administration, mostly the management of “human resources” in an army unit. The term is used in French-speaking armed ...

.

Lee and his army

surrendered to

General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

a few days later, effectively ending the war. McKinley joined a

Freemason

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

lodge (later renamed after him) in

Winchester, Virginia

Winchester is the northwesternmost Administrative divisions of Virginia#Independent cities, independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia, United States. It is the county seat of Frederick County, Virginia, Frederi ...

, before he and Carroll were transferred to Hancock's First Veterans Corps in Washington. Just before the war's end, McKinley received his final promotion, a

brevet commission as major. In July, the Veterans Corps was mustered out of service, and McKinley and Carroll were relieved of their duties. Carroll and Hancock encouraged McKinley to apply for a place in the peacetime army, but he declined and returned to Ohio the following month.

McKinley, along with Samuel M. Taylor and James C. Howe, co-authored and published a twelve-volume work, ''Official Roster of the Soldiers of the State of Ohio in the War of the Rebellion, 1861–1866'', published in 1886.

Legal career and marriage

After the war ended in 1865, McKinley decided on a career in the law and began

studying

Learning is the process of acquiring new understanding, knowledge, behaviors, skills, values, attitudes, and preferences. The ability to learn is possessed by humans, non-human animals, and some machines; there is also evidence for some kind ...

in the office of an attorney in

Poland, Ohio

Poland is a village (United States)#Ohio, village in eastern Mahoning County, Ohio, United States. The population was 2,463 at the 2020 United States census. A suburb about south of Youngstown, Ohio, Youngstown, it is part of the Mahoning Vall ...

. The following year, he continued his studies by attending

Albany Law School

Albany Law School is a private law school in Albany, New York. It was founded in 1851 and is the oldest independent law school in the nation. It is accredited by the American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary ...

in New York state. After studying there for less than a year, McKinley returned home and in March 1867 was

admitted to the bar

An admission to practice law is acquired when a lawyer receives a license to practice law. In jurisdictions with two types of lawyer, as with barristers and solicitors, barristers must gain admission to the bar whereas for solicitors there are dist ...

in

Warren, Ohio

Warren is a city in Trumbull County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. The population was 39,201 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Located along the Mahoning River, Warren lies approximately northwest of Youngstown, Ohio, Y ...

.

That same year, he moved to Canton, the county seat of

Stark County, Ohio

Stark County is a county located in the northeastern part of U.S. state of Ohio. As of the 2020 census, the population was 374,853. Its county seat is Canton. The county was created in 1808 and organized the next year. It is named for John S ...

, and set up a small office. He soon formed a partnership with George W. Belden, an experienced lawyer and former judge. His practice was successful enough for him to buy a block of buildings on Main Street in Canton, which provided him with a small but consistent rental income for decades.

When his Army friend Rutherford B. Hayes was nominated for governor in 1867, McKinley made speeches on his behalf in Stark County, his first foray into politics. The county was closely divided between

Democrats and

Republicans

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

, but Hayes carried it that year in his statewide victory. In 1869, McKinley ran for the office of

prosecuting attorney

A prosecutor is a legal representative of the prosecution in states with either the adversarial system, which is adopted in common law, or inquisitorial system, which is adopted in civil law. The prosecution is the legal party responsible ...

of Stark County, an office that had historically been held by Democrats, and was unexpectedly elected. When McKinley ran for re-election in 1871, the Democrats nominated

William A. Lynch, a prominent local lawyer, and McKinley was defeated by 143 votes.

As McKinley's professional career progressed, so too did his social life blossom: he wooed

Ida Saxton, a daughter of a prominent Canton family. They were married on January 25, 1871, in the newly built First Presbyterian Church of Canton. Ida soon joined her husband's Methodist church. Their first child, Katherine, was born on Christmas Day 1871. A second daughter, Ida, followed in 1873 but died the same year. McKinley's wife descended into a deep depression at her baby's death and her health, never robust, declined. Two years later, Katherine died of

typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often th ...

. Ida never recovered from their daughters' deaths, and the McKinleys had no more children. Ida McKinley developed

epilepsy

Epilepsy is a group of Non-communicable disease, non-communicable Neurological disorder, neurological disorders characterized by a tendency for recurrent, unprovoked Seizure, seizures. A seizure is a sudden burst of abnormal electrical activit ...

around the same time and depended strongly on her husband's presence. He remained a devoted husband and tended to his wife's medical and emotional needs for the rest of his life.

Ida insisted that her husband continue his increasingly successful career in law and politics. He attended the state Republican convention that nominated Hayes for a third term as governor in 1875, and campaigned again for his old friend in the election that fall. The next year, McKinley undertook a high-profile case defending a

group of striking coal miners, who were arrested for rioting after a clash with

strikebreaker

A strikebreaker (sometimes pejoratively called a scab, blackleg, bootlicker, blackguard or knobstick) is a person who works despite an ongoing strike. Strikebreakers may be current employees ( union members or not), or new hires to keep the orga ...

s. Lynch, McKinley's opponent in the 1871 election, and his partner,

William R. Day

William Rufus Day (April 17, 1849 – July 9, 1923) was an American diplomat and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1903 to 1922. Prior to his service on the Supreme Court, Day served as Uni ...

, were the opposing counsel, and the mine owners included

Mark Hanna

Marcus Alonzo Hanna (September 24, 1837 – February 15, 1904) was an American businessman and Republican politician who served as a United States Senator from Ohio as well as chairman of the Republican National Committee. A friend and ...

, a

Cleveland

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is situated across the Canada–U.S. maritime border and approximately west of the Ohio-Pennsylvania st ...

businessman. Taking the case ''

pro bono

( English: 'for the public good'), usually shortened to , is a Latin phrase for professional work undertaken voluntarily and without payment. The term traditionally referred to provision of legal services by legal professionals for people who a ...

,'' McKinley

was successful in getting all but one of the miners acquitted. The case raised McKinley's standing among laborers, a crucial part of the Stark County electorate, and also introduced him to Hanna, who would become his strongest backer in years to come.

McKinley's good standing with labor became useful that year as he campaigned for the Republican nomination for

Ohio's 17th congressional district. Delegates to the county conventions thought he could attract

blue-collar

A blue-collar worker is a person who performs manual labor or skilled trades. Blue-collar work may involve skilled or unskilled labor. The type of work may involve manufacturing, retail, warehousing, mining, carpentry, electrical work, custodia ...

voters, and in August 1876, McKinley was nominated. By that time, Hayes had been nominated for president, and McKinley campaigned for him while running his own congressional campaign. Both were successful. McKinley, campaigning mostly on his support for a

protective tariff

Protective tariffs are tariffs that are enacted with the aim of protecting a domestic industry. They aim to make imported goods cost more than equivalent goods produced domestically, thereby causing sales of domestically produced goods to rise, ...

, defeated the Democratic nominee,

Levi L. Lamborn, by 3,300 votes. Hayes won

a hotly disputed election to reach the presidency. McKinley's victory came at a personal cost: his income as a congressman would be half of what he earned as a lawyer.

Rising politician (1877–1895)

Spokesman for protection

McKinley took his congressional seat in October 1877, when President Hayes summoned Congress into special session. With the Republicans in the minority, McKinley was given unimportant committee assignments, which he undertook conscientiously. McKinley's friendship with Hayes did McKinley little good on

Capitol Hill

Capitol Hill is a neighborhoods in Washington, D.C., neighborhood in Washington, D.C., located in both the Northeast, Washington, D.C., Northeast and Southeast, Washington, D.C., Southeast quadrants. It is bounded by 14th Street SE & NE, F S ...

, as the president was not well regarded by many leaders there. The young congressman broke with Hayes on the question of the currency, but it did not affect their friendship. The United States had effectively been placed on the

gold standard

A gold standard is a backed currency, monetary system in which the standard economics, economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the ...

by the

Coinage Act of 1873

The Coinage Act of 1873 or Mint Act of 1873 was a general revision of laws relating to the Mint of the United States. By ending the right of holders of silver bullion to have it coined into standard silver dollars, while allowing holders of g ...

; when silver prices dropped significantly, many sought to make silver again a legal tender, equally with gold. Such a course would be inflationary, but advocates argued that the economic benefits of the increased

money supply

In macroeconomics, money supply (or money stock) refers to the total volume of money held by the public at a particular point in time. There are several ways to define "money", but standard measures usually include currency in circulation (i ...

would be worth the inflation; opponents warned that "

free silver" would not bring the promised benefits and would harm the United States in international trade. McKinley voted for the

Bland–Allison Act

The Bland–Allison Act, also referred to as the Grand Bland Plan of 1878, was an act of the United States Congress requiring the U.S. Treasury to buy a certain amount of silver and put it into circulation as silver dollars. Though the bill was ...

of 1878, which mandated large government purchases of silver for striking into money, and also joined the large majorities in each house that overrode Hayes's veto of the legislation. In so doing, McKinley voted against the position of the House Republican leader,

James Garfield

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 1881 until Assassination of James A. Garfield, his death in September that year after being shot two months ea ...

, a fellow Ohioan and his friend.

From his first term in Congress, McKinley was a strong advocate of protective tariffs. The primary intention of such imposts was not to raise revenue, but to allow American manufacturing to develop by giving it a price advantage in the domestic market over foreign competitors. McKinley biographer

Margaret Leech noted that Canton had become prosperous as a center for the manufacture of farm equipment because of

protection

Protection is any measure taken to guard something against damage caused by outside forces. Protection can be provided to physical objects, including organisms, to systems, and to intangible things like civil and political rights. Although ...

, and that this may have helped form his political views. McKinley introduced and supported bills that raised protective tariffs, and opposed those that lowered them or imposed tariffs simply to raise revenue. Garfield's election as president in 1880 created a vacancy on the

House Ways and Means Committee

A ways and means committee is a government body that is charged with reviewing and making recommendations for government budgets. Because the raising of revenue is vital to carrying out governmental operations, such a committee is tasked with fi ...

; McKinley was selected to fill it, gaining a spot on the most powerful committee after only two terms.

McKinley increasingly became a significant figure in national politics. In 1880, he served a brief term as Ohio's representative on the

Republican National Committee

The Republican National Committee (RNC) is the primary committee of the Republican Party of the United States. Its members are chosen by the state delegations at the national convention every four years. It is responsible for developing and pr ...

. In 1884, he was elected a delegate to

that year's Republican convention, where he served as chair of the Committee on Resolutions and won plaudits for his handling of the convention when called upon to preside. By 1886, McKinley, Senator

John Sherman

John Sherman (May 10, 1823October 22, 1900) was an American politician from Ohio who served in federal office throughout the Civil War and into the late nineteenth century. A member of the Republican Party, he served in both houses of the U. ...

, and Governor

Joseph B. Foraker

Joseph Benson Foraker (July 5, 1846 – May 10, 1917) was an American politician of the Republican Party who served as the 37th governor of Ohio from 1886 to 1890 and as a United States senator from Ohio from 1897 until 1909.

Foraker was ...

were considered the leaders of the Republican party in Ohio. Sherman, who had helped to found the Republican Party, ran three times for the Republican nomination for president in the 1880s, each time failing, while Foraker began a meteoric rise in Ohio politics early in the decade. Hanna, once he entered public affairs as a political manager and generous contributor, supported Sherman's ambitions, as well as those of Foraker. The latter relationship broke off at the

1888 Republican National Convention

The 1888 Republican National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held at the Auditorium Theatre in Chicago, Illinois, on June 19–25, 1888. It resulted in the nomination of former United States Senate, Senator Benjamin Harrison of ...

, where McKinley, Foraker, and Hanna were all delegates supporting Sherman. Convinced Sherman could not win, Foraker threw his support to

Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

Senator

James G. Blaine

James Gillespie Blaine (January 31, 1830January 27, 1893) was an American statesman and Republican politician who represented Maine in the United States House of Representatives from 1863 to 1876, serving as speaker of the U.S. House of Rep ...

, the unsuccessful Republican 1884 presidential nominee. When Blaine said he was not a candidate, Foraker returned to Sherman, but the nomination went to former

Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

senator

Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was the 23rd president of the United States, serving from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia—a grandson of the ninth president, William Henry Harrison, and a ...

, who was elected president. In the bitterness that followed the convention, Hanna abandoned Foraker. For the rest of McKinley's life, the Ohio Republican Party was divided into two factions, one aligned with McKinley, Sherman, and Hanna, and the other with Foraker. Hanna came to admire McKinley and became a friend and close adviser to him. Although Hanna remained active in business and in promoting other Republicans, in the years after 1888, he spent an increasing amount of time boosting McKinley's political career.

In 1889, with the Republicans in the majority, McKinley sought election as

Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hung ...

. He failed to gain the post, which went to

Thomas B. Reed of

Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

; however, Speaker Reed appointed McKinley chairman of the Ways and Means Committee. The Ohioan guided the

McKinley Tariff

The Tariff Act of 1890, commonly called the McKinley Tariff, was an act of the United States Congress framed by then-Representative William McKinley, that became law on October 1, 1890. The tariff raised the average duty on imports to almost 50% ...

of 1890 through Congress; although McKinley's work was altered through the influence of special interests in the Senate, it imposed a number of protective tariffs on foreign goods.

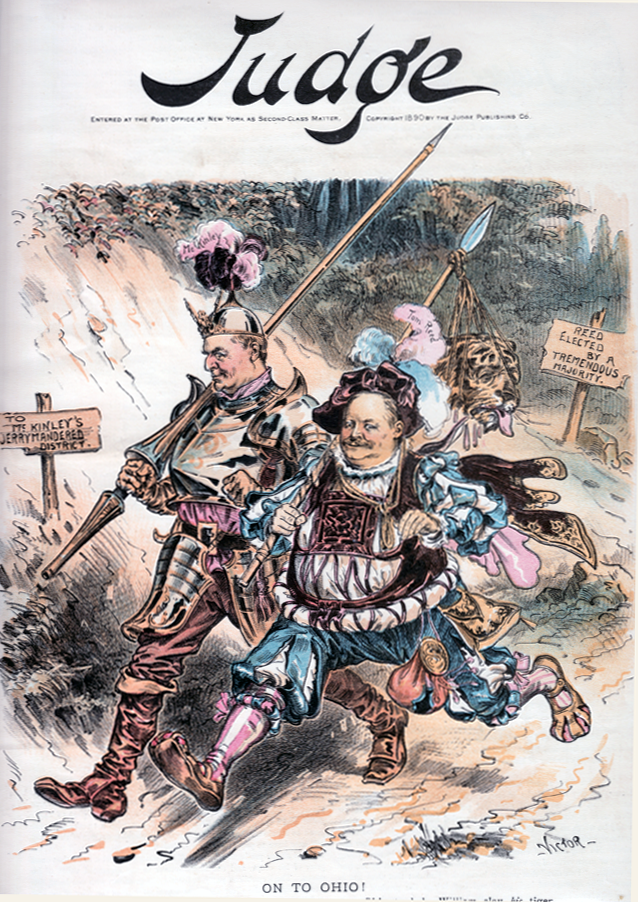

Gerrymandering and defeat for re-election

Recognizing McKinley's potential, the Democrats, whenever they controlled the Ohio legislature, sought to

gerrymander

Gerrymandering, ( , originally ) defined in the contexts of Representative democracy, representative electoral systems, is the political manipulation of Boundary delimitation, electoral district boundaries to advantage a Political party, pa ...

or redistrict him out of office. In 1878, McKinley was redistricted to the

16th congressional district; he won anyway, causing Hayes to exult, "Oh, the good luck of McKinley! He was gerrymandered out and then beat the gerrymander! We enjoyed it as much as he did." After the 1882 election, McKinley was unseated on an election contest by a near party-line House vote. Out of office, he was briefly depressed by the setback, but soon vowed to run again. The Democrats again redistricted Stark County for the 1884 election; McKinley was returned to Congress anyway.

For 1890, the Democrats gerrymandered McKinley one final time, placing Stark County in the same district as one of the strongest pro-Democrat counties,

Holmes

Holmes may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Holmes (surname), a list of people and fictional characters

** Sherlock Holmes, a fictional detective

* Holmes (given name), a list of people

* Gordon Holmes, a penname used by Louis Trac ...

, populated by solidly Democratic

Pennsylvania Dutch

The Pennsylvania Dutch (), also referred to as Pennsylvania Germans, are an ethnic group in Pennsylvania in the United States, Ontario in Canada, and other regions of both nations. They largely originate from the Palatinate (region), Palatina ...

. Based on past results, Democrats thought the new boundaries should produce a Democratic majority of 2,000 to 3,000. The Republicans could not reverse the gerrymander, as legislative elections would not be held until 1891, but they could throw all their energies into the district. The McKinley Tariff was a main theme of the Democratic campaign nationwide, and there was considerable attention paid to McKinley's race. The Republican Party sent its leading orators to Canton, including Blaine (then

Secretary of State), Speaker Reed, and President Harrison. The Democrats countered with their best spokesmen on tariff issues. McKinley tirelessly stumped his new district, reaching out to its 40,000 voters to explain that his tariff:

Democrats ran a strong candidate in former lieutenant governor

John G. Warwick. To drive their point home, they hired young partisans to pretend to be peddlers, who went door to door offering 25-cent tinware to housewives for 50 cents, explaining the rise in prices was due to the McKinley Tariff. In the end, McKinley lost by 300 votes, but the Republicans won a statewide majority and claimed a moral victory.

Governor of Ohio (1892–1896)

Even before McKinley completed his term in Congress, he met with a delegation of Ohioans urging him to run for governor. Governor

James E. Campbell

James Edwin Campbell (July 7, 1843 – December 18, 1924) was an American attorney and Democratic politician from Ohio. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1884 to 1889 and as the 38th governor of Ohio from 1890 to 189 ...

, a Democrat, who had defeated Foraker in 1889, was to seek re-election in 1891. The Ohio Republican party remained divided, but McKinley quietly arranged for Foraker to nominate him at the 1891 state Republican convention, which chose McKinley by acclamation. The former congressman spent much of the second half of 1891 campaigning against Campbell, beginning in his birthplace of Niles. Hanna, however, was little seen in the campaign; he spent much of his time raising funds for the election of legislators pledged to vote for Sherman in the 1892 senatorial election (state legislators still elected US Senators). McKinley won the 1891 election by some 20,000 votes; the following January, Sherman, with considerable assistance from Hanna, turned back a challenge by Foraker to win the legislature's vote for another term in the US Senate.

Ohio's governor had relatively little power—for example, he could recommend legislation, but not veto it—but with Ohio a key

swing state

In United States politics, a swing state (also known as battleground state, toss-up state, or purple state) is any state that could reasonably be won by either the Democratic or Republican candidate in a statewide election, most often refe ...

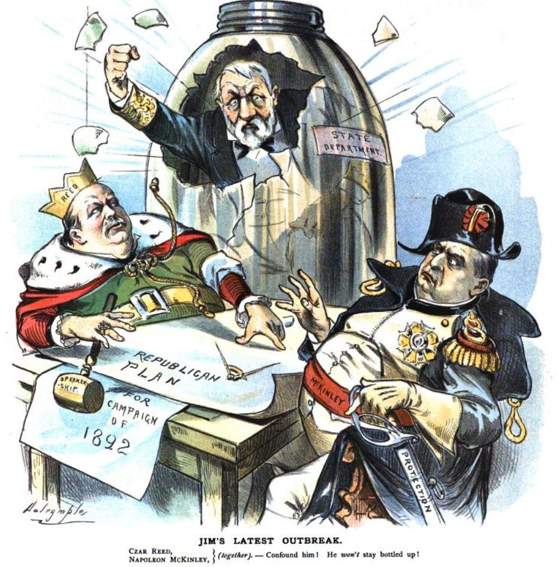

, its governor was a major figure in national politics. Although McKinley believed that the health of the nation depended on that of business, he was evenhanded in dealing with labor. He procured legislation that set up an arbitration board to settle work disputes and obtained passage of a law that fined employers who fired workers for belonging to a union.

President Harrison had proven unpopular; there were divisions even within the Republican party as the year 1892 began and Harrison began his re-election drive. Although no declared Republican candidate opposed Harrison, many Republicans were ready to dump the president from the ticket if an alternative emerged. Among the possible candidates spoken of were McKinley, Reed, and the aging Blaine. Fearing that the Ohio governor would emerge as a candidate, Harrison's managers arranged for McKinley to be permanent chairman of

the convention in

Minneapolis

Minneapolis is a city in Hennepin County, Minnesota, United States, and its county seat. With a population of 429,954 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the state's List of cities in Minnesota, most populous city. Locat ...

, requiring him to play a public, neutral role. Hanna established an unofficial McKinley headquarters near the convention hall, though no active effort was made to convert delegates to McKinley's cause. McKinley objected to delegate votes being cast for him; nevertheless he finished second, behind the renominated Harrison, but ahead of Blaine, who had sent word he did not want to be considered. Although McKinley campaigned loyally for the Republican ticket, Harrison was defeated by former President Cleveland in

the November election. In the wake of Cleveland's victory, McKinley was seen by some as the likely Republican candidate in 1896.

Soon after Cleveland's return to office, hard times struck the nation with the

Panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States. It began in February 1893 and officially ended eight months later. The Panic of 1896 followed. It was the most serious economic depression in history until the Great Depression of ...

. A businessman in

Youngstown

Youngstown is a city in Mahoning County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of municipalities in Ohio, 11th-most populous city in Ohio with a population of 60,068 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. The Mahoning ...

, Robert Walker, had lent money to McKinley in their younger days; in gratitude, McKinley had often guaranteed Walker's borrowings for his business. The governor had never kept track of what he was signing; he believed Walker a sound businessman. In fact, Walker had deceived McKinley, telling him that new notes were actually renewals of matured ones. Walker was ruined by the recession; McKinley was called upon for repayment in February 1893. The total owed was over $100,000 (equivalent to $ million in ) and a despairing McKinley initially proposed to resign as governor and earn the money as an attorney. Instead, McKinley's wealthy supporters, including Hanna and Chicago publisher

H. H. Kohlsaat, became trustees of a fund from which the notes would be paid. Both William and Ida McKinley placed their property in the hands of the fund's trustees (who included Hanna and Kohlsaat), and the supporters raised and contributed a substantial sum of money. All of the couple's property was returned to them by the end of 1893, and when McKinley, who had promised eventual repayment, asked for the list of contributors, it was refused him. Many people who had suffered in the hard times sympathized with McKinley, whose popularity grew. He was easily re-elected in November 1893, receiving the largest percentage of the vote of any Ohio governor since the Civil War.

McKinley campaigned widely for Republicans in the 1894 midterm congressional elections; many party candidates in districts where he spoke were successful. His political efforts in Ohio were rewarded with the election in November 1895 of a Republican successor as governor,

Asa Bushnell, and a Republican legislature that elected Foraker to the Senate. McKinley supported Foraker for the Senate and Bushnell (who was of Foraker's faction) for governor; in return, the new senator-elect agreed to back McKinley's presidential ambitions. With party peace in Ohio assured, McKinley turned to the national arena.

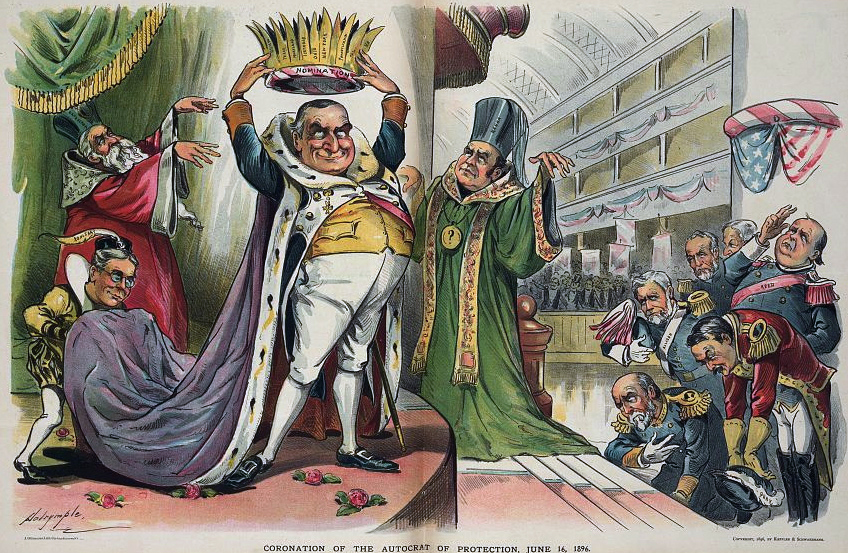

Election of 1896

Obtaining the nomination

It is unclear when William McKinley began to seriously prepare a run for president. As McKinley biographer

Kevin Phillips notes, "No documents, no diaries, no confidential letters to Mark Hanna (or anyone else) contain his secret hopes or veiled stratagems." From the beginning, McKinley's preparations had the participation of Hanna, whose biographer William T. Horner noted, "What is certainly true is that in 1888 the two men began to develop a close working relationship that helped put McKinley in the White House." Sherman did not run for president again after 1888, and so Hanna could support McKinley's ambitions for that office wholeheartedly.

Backed by Hanna's money and organizational skills, McKinley quietly built support for a presidential bid through 1895 and early 1896. When other contenders such as Speaker Reed and

Iowa

Iowa ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the upper Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west; Wisconsin to the northeast, Ill ...

Senator

William B. Allison

William Boyd Allison (March 2, 1829 – August 4, 1908) was an American politician. An early leader of the Iowa Republican Party, he represented northeastern Iowa in the United States House of Representatives before representing his state in t ...

sent agents outside their states to organize Republicans in support of their candidacies, they found that Hanna's agents had preceded them. According to historian Stanley Jones in his study of the 1896 election:

Hanna, on McKinley's behalf, met with the eastern Republican

political boss

In the politics of the United States of America, a boss is a person who controls a faction or local branch of a political party. They do not necessarily hold public office themselves; most historical bosses did not, at least during the times of th ...

es, such as

Thomas Platt of New York and Senator

Matthew Quay

Matthew Stanley Quay (; September 30, 1833May 28, 1904) was an American politician of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party who represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate from 1887 until 1899 and from 1901 until his ...

of Pennsylvania, who were willing to guarantee McKinley's nomination in exchange for promises regarding patronage and offices. McKinley, however, was determined to obtain the nomination without making deals, and Hanna accepted that decision. Many of their early efforts were focused on the South; Hanna obtained a vacation home in southern Georgia where McKinley visited and met with Republican politicians from the region. McKinley needed 453½ delegate votes to gain the nomination; he gained nearly half that number from the South and

border states. Platt lamented in his memoirs, "

anna

Anna may refer to:

People Surname and given name

* Anna (name)

Mononym

* Anna the Prophetess, in the Gospel of Luke

* Anna of East Anglia, King (died c.654)

* Anna (wife of Artabasdos) (fl. 715–773)

* Anna (daughter of Boris I) (9th–10th c ...

had the South practically solid before some of us awakened."

Quay and Platt still hoped to deny McKinley a first-ballot majority at

the convention by boosting support for local

favorite son

Favorite son (or favorite daughter) is a political term referring to a presidential candidate, either one that is nominated by a state but considered a nonviable candidate or a politician whose electoral appeal derives from their native state, r ...

candidates such as Quay himself, New York Governor (and former vice president)

Levi P. Morton

Levi Parsons Morton (May 16, 1824 – May 16, 1920) was the 22nd vice president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He also served as List of ambassadors of the United States to France, United States ambassador to France, as a United States H ...

, and Illinois Senator

Shelby Cullom

Shelby Moore Cullom (November 22, 1829 – January 28, 1914) was an American politician who served in the United States House of Representatives, the United States Senate and as the 17th Governor of Illinois. He was Illinois's longest serving s ...

. Delegate-rich Illinois proved a crucial battleground, as McKinley supporters, such as Chicago businessman (and future vice president)

Charles G. Dawes, sought to elect delegates pledged to vote for McKinley at the national convention in St. Louis. Cullom proved unable to stand against McKinley despite the support of local Republican machines; at the state convention at the end of April, McKinley completed a near-sweep of Illinois' delegates. Former president Harrison had been deemed a possible contender if he entered the race; when Harrison made it known he would not seek a third nomination, the McKinley organization took control of Indiana with a speed Harrison privately found unseemly. Morton operatives who journeyed to Indiana sent word back that they had found the state alive for McKinley. Wyoming Senator

Francis Warren wrote, "The politicians are making a hard fight against him, but if the masses could speak, McKinley is the choice of at least 75% of the entire

ody of Ody may refer to:

*Ody, a kind of sampy, magical amulets in Madagascar

*Ody Abbott (1888–1933), American baseball player

*Ody Alfa (born 1999), Nigerian footballer

*Ody J. Fish (1925–2007), American politician

*Ody Koopman (1902–1949), Dutch ...

Republican voters in the Union".

By the time the national convention began in

St. Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

on June 16, 1896, McKinley had an ample majority of delegates. The former governor, who remained in Canton, followed events at the convention closely by telephone, and was able to hear part of Foraker's speech nominating him over the line. When Ohio was reached in the roll call of states, its votes gave McKinley the nomination, which he celebrated by hugging his wife and mother as his friends fled the house, anticipating the first of many crowds that gathered at the Republican candidate's home. Thousands of partisans came from Canton and surrounding towns that evening to hear McKinley speak from his front porch. The convention nominated Republican National Committee vice chairman

Garret Hobart

Garret Augustus Hobart (June 3, 1844 – November 21, 1899) was an American businessman and politician who was the 24th vice president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his death in 1899, under President William McKinley. A mem ...

of New Jersey for vice president, a choice actually made, by most accounts, by Hanna. Hobart, a wealthy lawyer, businessman, and former state legislator, was not widely known, but as Hanna biographer

Herbert Croly

Herbert David Croly (January 23, 1869 – May 17, 1930) was an intellectual leader of the progressive movement as an editor, political philosopher and a co-founder of the magazine ''The New Republic'' in early twentieth-century America. His polit ...

pointed out, "if he did little to strengthen the ticket he did nothing to weaken it".

General election campaign

Before the Republican convention, McKinley had been a "straddle bug" on the currency question, favoring moderate positions on silver such as accomplishing

bimetallism

Bimetallism, also known as the bimetallic standard, is a monetary standard in which the value of the monetary unit is defined as equivalent to certain quantities of two metals, typically gold and silver, creating a fixed Exchange rate, rate of ...

by international agreement. In the final days before the convention, McKinley decided, after hearing from politicians and businessmen, that the platform should endorse the gold standard, though it should allow for bimetallism through coordination with other nations. Adoption of the platform caused some western delegates, led by Colorado Senator

Henry M. Teller, to walk out of the convention. However, compared with the Democrats, Republican divisions on the issue were small, especially as McKinley promised future concessions to silver advocates.

The bad economic times had continued and strengthened the hand of forces for

free silver. The issue bitterly divided the Democratic Party; President Cleveland firmly supported the gold standard, but an increasing number of rural Democrats wanted silver, especially in the South and West. The silverites took control of the

1896 Democratic National Convention

The 1896 Democratic National Convention, held at the Chicago Coliseum from July 7 to July 11, was the scene of William Jennings Bryan's nomination as the Democratic presidential candidate for the 1896 U.S. presidential election.

At age 36 ...

and chose

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator, and politician. He was a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running three times as the party' ...

for president; he had electrified the delegates with his

Cross of Gold speech

The Cross of Gold speech was delivered by William Jennings Bryan, a former United States United States House of Representatives, Representative from Nebraska, at the 1896 Democratic National Convention, Democratic National Convention in Chicag ...

. Bryan's financial radicalism shocked bankers—they thought his inflationary program would bankrupt the railroads and ruin the economy. Hanna approached them for support for his strategy to win the election, and they gave $3.5 million for speakers and over 200 million pamphlets advocating the Republican position on the money and tariff questions.

Bryan's campaign had at most an estimated $500,000. With his eloquence and youthful energy his major assets in the race, Bryan decided on a

whistle-stop political tour by train on an unprecedented scale. Hanna urged McKinley to match Bryan's tour with one of his own; the candidate declined on the grounds that the Democrat was a better

stump speaker: "I might just as well set up a trapeze on my front lawn and compete with some professional athlete as go out speaking against Bryan. I have to ''think'' when I speak." Instead of going to the people, McKinley would remain at home in Canton and allow the people to come to him; according to historian R. Hal Williams in his book on the 1896 election, "it was, as it turned out, a brilliant strategy. McKinley's '

Front Porch Campaign

A front porch campaign is a low-key electoral campaign used in American politics in which the candidate remains close to or at home where they issue written statements and give speeches to supporters who come to visit. The candidate largely doe ...

' became a legend in American political history."

McKinley made himself available to the public every day except Sunday, receiving delegations from the front porch of his home. The railroads subsidized the visitors with low excursion rates—the pro-silver

Cleveland ''Plain Dealer'' disgustedly stated that going to Canton had been made "cheaper than staying at home". Delegations marched through the streets from the railroad station to McKinley's home on North Market Street. Once there, they crowded close to the front porch—from which they surreptitiously whittled souvenirs—as their spokesman addressed McKinley. The candidate then responded, speaking on campaign issues in a speech molded to suit the interest of the delegation. The speeches were carefully scripted to avoid extemporaneous remarks; even the spokesman's remarks were approved by McKinley or a representative. This was done as the candidate feared an offhand comment by another that might rebound on him, as

had happened to Blaine in 1884.

Most Democratic newspapers refused to support Bryan, the major exception being the New York ''Journal'', controlled by

William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American newspaper publisher and politician who developed the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His extravagant methods of yellow jou ...

, whose fortune was based on silver mines. In biased reporting and through the sharp cartoons of

Homer Davenport

Homer Calvin Davenport (March 8, 1867 – May 2, 1912) was a political cartoonist and writer from the United States. He is known for drawings that satirized figures of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, most notably Ohio Senator Mark Hanna. Al ...

, Hanna was viciously characterized as a

plutocrat, trampling on labor. McKinley was drawn as a child, easily controlled by big business. Even today, these depictions still color the images of Hanna and McKinley: one as a heartless businessman, the other as a creature of Hanna and others of his ilk.

The Democrats had pamphlets too, though not as many. Jones analyzed how voters responded to the education campaigns of the two parties:

McKinley always thought of himself as a tariff man and expected that the monetary issues would fade away in a month. He was mistaken, silver and gold dominated the campaign.

The battleground proved to be the Midwest—the South and most of the West were conceded to Bryan—and the Democrat spent much of his time in those crucial states. The Northeast was considered most likely safe for McKinley after the early-voting states of Maine and

Vermont

Vermont () is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, New York (state), New York to the west, and the Provinces and territories of Ca ...