Prehistoric Cyprus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Prehistoric Period is the oldest part of Cypriot history. This article covers the period 11,000 to 800 BC and ends immediately before the documented history of Cyprus begins.

The Prehistoric Period is the oldest part of Cypriot history. This article covers the period 11,000 to 800 BC and ends immediately before the documented history of Cyprus begins.

In the 6th millennium BC, the aceramic Choirokoitia culture (

In the 6th millennium BC, the aceramic Choirokoitia culture (

The Late Cypriot (LC) IIC (1300–1200 BC) was a time of local prosperity. Cities were rebuilt on a rectangular grid plan, like Enkomi, where the town gates now correspond to the grid axes and numerous grand buildings front the street system or newly founded. Great official buildings (constructed from

The Late Cypriot (LC) IIC (1300–1200 BC) was a time of local prosperity. Cities were rebuilt on a rectangular grid plan, like Enkomi, where the town gates now correspond to the grid axes and numerous grand buildings front the street system or newly founded. Great official buildings (constructed from

''Cydonia'', The Modern Antiquarian, Jan. 23, 2008

/ref> New burial customs with rock-cut chamber tombs having a long "dromos" (a ramp leading gradually towards the entrance) along with new religious beliefs speak in favour of the arrival of people from the Aegean. The same view is supported by the introduction of the safety pin that denotes a new fashion in dressing and also by a name scratched on a bronze skewer from Paphos and dating between 1050–950 BC. Foundations myths documented by classical authors connect the foundation of numerous Cypriot towns with immigrant Greek heroes in the wake of the

During the

During the

Archaeology and history of Cyprus

* Deneia Bronze Age potter

Ancient History of Cyprus, by Cypriot government

. {{Europe topic , Prehistory of Prehistoric Cyprus,

The Prehistoric Period is the oldest part of Cypriot history. This article covers the period 11,000 to 800 BC and ends immediately before the documented history of Cyprus begins.

The Prehistoric Period is the oldest part of Cypriot history. This article covers the period 11,000 to 800 BC and ends immediately before the documented history of Cyprus begins.

Paleolithic

Prior to the arrival of humans in Cyprus, only four terrestrial mammal species were present on the islands, including the Cypriot pygmy hippopotamus and the Cyprus dwarf elephant, which were much smaller than their mainland ancestors as a result ofinsular dwarfism

Insular dwarfism, a form of phyletic dwarfism, is the process and condition of large animals evolving or having a reduced body size when their population's range is limited to a small environment, primarily islands. This natural process is disti ...

. The ancestors of these species arrived on Cyprus at least 200,000 years ago, with the other species being the genet '' Genetta plesictoides'' and the still living Cypriot mouse. The earliest humans to inhabit Cyprus were hunter gatherers who arrived on the island around 13–12,000 years ago (11–10,000 BC), with some of the oldest well-dated sites being Aetokremnos

Aetokremnos is a rock shelter near Limassol on the southern coast of Cyprus. It is widely considered to host some of the oldest evidence of human habitation of Cyprus, dating to around 12,000 years ago. It is situated on a steep cliff site c. abo ...

on the south coast, which is suggested to show evidence of hunting of the dwarf hippopotamus and dwarf elephant, and the inland site of Roudias in southeast Cyprus. These hunter-gatherers are suggested to have originated from the Natufian culture

The Natufian culture ( ) is an archaeological culture of the late Epipalaeolithic Near East in West Asia from 15–11,500 Before Present. The culture was unusual in that it supported a sedentism, sedentary or semi-sedentary population even befor ...

of the neighbouring Levant. The last records of the endemic mammals other than the mouse date to shortly after human settlement. The hunter gatherers later introduced wild boar

The wild boar (''Sus scrofa''), also known as the wild swine, common wild pig, Eurasian wild pig, or simply wild pig, is a Suidae, suid native to much of Eurasia and North Africa, and has been introduced to the Americas and Oceania. The speci ...

to the island around 12,000 years ago, likely to act as a source of food.

Neolithic

Aceramic Neolithic

The oldest evidence ofNeolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

settlement is dated to 8800–8600 BC. The first settlers were already agriculturalists ( PPNB), but did not yet produce pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other raw materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. The place where such wares are made by a ''potter'' is al ...

(aceramic Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

). They introduced the dog, sheep, goats and maybe cattle and pigs as well as numerous wild animals like foxes (''Vulpes vulpes'') and Persian fallow deer

The Persian fallow deer (''Dama mesopotamica'') is a deer species once native to all of the Middle East, but currently only living in Iran and Israel. It was reintroduced in Israel. It has been listed as endangered on the IUCN Red List since 2008 ...

(''Dama mesopotamica'') that were previously unknown on the island. The PPNB settlers built round houses with floors made of terrazzo

Terrazzo is a composite material, poured in place or precast, which is used for floor and wall treatments. It consists of chips of marble, quartz, granite, glass, or other suitable material, poured with a cementitious binder (for chemical bind ...

of burned lime (e.g. Kastros, Shillourokambos, Tenta) and cultivated einkorn and emmer. Pig, sheep, goat and cattle were kept, but remained morphologically wild. Evidence for cattle (attested at Shillourokambos) is rare and when they apparently died out in the course of the 8th millennium they were not reintroduced until the early Bronze Age.

In the 6th millennium BC, the aceramic Choirokoitia culture (

In the 6th millennium BC, the aceramic Choirokoitia culture (Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

I) was characterized by round houses (tholoi), stone vessels and an economy based on sheep

Sheep (: sheep) or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are a domesticated, ruminant mammal typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus '' Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to d ...

, goat

The goat or domestic goat (''Capra hircus'') is a species of Caprinae, goat-antelope that is mostly kept as livestock. It was domesticated from the wild goat (''C. aegagrus'') of Southwest Asia and Eastern Europe. The goat is a member of the ...

s and pigs

The pig (''Sus domesticus''), also called swine (: swine) or hog, is an omnivorous, domesticated, even-toed, hoofed mammal. It is named the domestic pig when distinguishing it from other members of the genus '' Sus''. Some authorities cons ...

. The daily life of the people in those Neolithic villages was spent in farming, hunting, animal husbandry and the lithic industry, while homesteaders (likely women) were engaged in spindling and weaving cloths, in addition to their probable participation in other activities. The lithic industry was the most individual feature of this aceramic culture and innumerable stone vessels made of grey andesite

Andesite () is a volcanic rock of intermediate composition. In a general sense, it is the intermediate type between silica-poor basalt and silica-rich rhyolite. It is fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic in texture, and is composed predomina ...

have been discovered during excavations. The houses had a foundation of river pebbles, the remainder of the building was constructed in mudbrick. Sometimes several round houses were joined together to form a kind of compound. Some of these houses reach a diameter of up to 10 m. Inhumation burials are located inside the houses.

Water wells discovered by archaeologists in western Cyprus are believed to be among the oldest in the world, dated at 9,000 to 10,500 years old, putting them in the Stone Age

The Stone Age was a broad prehistory, prehistoric period during which Rock (geology), stone was widely used to make stone tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years and ended b ...

. They are said to show the sophistication of early settlers, and their heightened appreciation for the environment.

Plant remains indicate the cultivation of cereal

A cereal is a grass cultivated for its edible grain. Cereals are the world's largest crops, and are therefore staple foods. They include rice, wheat, rye, oats, barley, millet, and maize ( Corn). Edible grains from other plant families, ...

s, lentil

The lentil (''Vicia lens'' or ''Lens culinaris'') is an annual plant, annual legume grown for its Lens (geometry), lens-shaped edible seeds or ''pulses'', also called ''lentils''. It is about tall, and the seeds grow in Legume, pods, usually w ...

s, bean

A bean is the seed of some plants in the legume family (Fabaceae) used as a vegetable for human consumption or animal feed. The seeds are often preserved through drying (a ''pulse''), but fresh beans are also sold. Dried beans are traditi ...

s, pea

Pea (''pisum'' in Latin) is a pulse or fodder crop, but the word often refers to the seed or sometimes the pod of this flowering plant species. Peas are eaten as a vegetable. Carl Linnaeus gave the species the scientific name ''Pisum sativum' ...

s and a kind of plum

A plum is a fruit of some species in Prunus subg. Prunus, ''Prunus'' subg. ''Prunus'.'' Dried plums are often called prunes, though in the United States they may be labeled as 'dried plums', especially during the 21st century.

Plums are ...

called Bullace. Remains of the following animal species were recovered during excavations: Persian fallow deer

The Persian fallow deer (''Dama mesopotamica'') is a deer species once native to all of the Middle East, but currently only living in Iran and Israel. It was reintroduced in Israel. It has been listed as endangered on the IUCN Red List since 2008 ...

, goat

The goat or domestic goat (''Capra hircus'') is a species of Caprinae, goat-antelope that is mostly kept as livestock. It was domesticated from the wild goat (''C. aegagrus'') of Southwest Asia and Eastern Europe. The goat is a member of the ...

, sheep

Sheep (: sheep) or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are a domesticated, ruminant mammal typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus '' Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to d ...

, mouflon

The mouflon (''Ovis gmelini'') is a wild sheep native to Cyprus, and the Caspian region, including eastern Turkey, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Iran. It is also found in parts of Europe. It is thought to be the ancestor of all modern domest ...

and pig. More remains indicate Red deer

The red deer (''Cervus elaphus'') is one of the largest deer species. A male red deer is called a stag or Hart (deer), hart, and a female is called a doe or hind. The red deer inhabits most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Ir ...

, Roe deer, a kind of horse and a kind of dog but no cattle as yet.

Life expectancy seems to have been short; the average age at death appears to have been about 34 years, and there was a high infant mortality rate.

In 2004, the remains of an 8-month-old cat

The cat (''Felis catus''), also referred to as the domestic cat or house cat, is a small domesticated carnivorous mammal. It is the only domesticated species of the family Felidae. Advances in archaeology and genetics have shown that the ...

were discovered buried with its human owner at a Neolithic archeological site in Cyprus. The grave is estimated to be 9,500 years old, predating Egyptian civilization and pushing back the earliest known feline-human association significantly.

Ceramic Neolithic

The aceramic civilisation of Cyprus came to an end quite abruptly around 6000 BC. It was probably followed by a vacuum of almost 1,500 years until around 4500 BC when one sees the emergence of Neolithic II (CeramicNeolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

).

At this time newcomers arrived in Cyprus introducing a new Neolithic era. The main settlement that embodies most of the characteristics of the period is Sotira near the south coast of Cyprus. The following ceramic Sotira phase (Neolithic II) has monochrome vessels with combed decoration. It had nearly fifty houses, usually having a single room that had its own hearth, benches, platforms and partitions that provided working places. The houses were on the main free-standing, with relatively thin walls and tended to be square with rounded corners. The sub-rectangular houses had two or three rooms. In Khirokitia, the remains of the Sotira phase overlay the aceramic remains. There are Sotira-ceramics in the earliest levels of Erimi as well. In the North of the island, the ceramic levels of Troulli may be synchronous with Sotira in the South.

The Late Neolithic is characterised by a red-on white ware. The late Neolithic settlement of Kalavassos-Pamboules has sunken houses.

Chalcolithic

The Neolithic culture was destroyed by an earthquake c. 3800 BC. In the society that emerged there are no overt signs of newcomers but signs of continuity, therefore despite the violent natural catastrophe, there is an internal evolution that is formalised around 3500 BC with appearance of the first metalwork and the beginning of theChalcolithic

The Chalcolithic ( ) (also called the Copper Age and Eneolithic) was an archaeological period characterized by the increasing use of smelted copper. It followed the Neolithic and preceded the Bronze Age. It occurred at different periods in di ...

(copper and stone) period that lasted until about 2500/2300 BC. Very few chisels, hooks and jewellery of pure copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

have survived, but in one example there is a minimal presence of tin, something which may support contact with Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, where copper-working was established earlier.

During the Chalcolithic period changes of major importance took place along with technological and artistic achievements, especially towards its end. The presence of a stamp seal

__NOTOC__

The stamp seal (also impression seal) is a common seal die, frequently carved from stone, known at least since the 6th millennium BC (Halaf culture) and probably earlier. The dies were used to impress their picture or inscription int ...

and the size of the houses that was not uniform, both hint at property rights and social hierarchy. The same story is supported by the burials because some of them were deposited in pits without grave goods and some in shaft graves with relatively rich furniture, both being indications of wealth accumulation by certain families and social differentiation.

The Eneolithic or Chalcolithic

The Chalcolithic ( ) (also called the Copper Age and Eneolithic) was an archaeological period characterized by the increasing use of smelted copper. It followed the Neolithic and preceded the Bronze Age. It occurred at different periods in di ...

period is divided into the Erimi (Chalcolithic I) and Ambelikou/Ayios Georghios (Chalcolithic II) phases.

The type site

In archaeology, a type site (American English) or type-site (British English) is the site used to define a particular archaeological culture or other typological unit, which is often named after it. For example, discoveries at La Tène and H ...

of the Neolithic I period is Erimi on the South coast of the island. The ceramic is characterised by red-on white pottery with linear and floral designs. Stone (steatite) and clay figurines with spread arms are common. In Erimi, a copper chisel has been found, this is the oldest copper find in Cyprus so far. Otherwise, copper is still rare. Another important Chalcolithic site is Lempa (Lemba).

The Chalcolithic period did not come to an end at the same time throughout Cyprus, and lingered in the Paphos

Paphos, also spelled as Pafos, is a coastal city in southwest Cyprus and the capital of Paphos District. In classical antiquity, two locations were called Paphos: #Old Paphos, Old Paphos, today known as Kouklia, and #New Paphos, New Paphos. It i ...

area until the arrival of the Bronze Age.

Bronze Age

Early Bronze Age

The new era was introduced by people from Anatolia who came to Cyprus about 2400 BC. The newcomers are identified archaeologically because of a distinct material culture, known as the Philia Culture. This was the earliest manifestation of the Bronze Age. Philia sites are found in most parts of the island. As the newcomers knew how to work with copper they soon moved to the so-called copperbelt of the island, that is the foothills of the Troodos Mountains. This movement reflects the increased interest in the raw material that was going to be so closely connected with Cyprus for several centuries afterwards. The Philia phase of the Bronze Age (or Philia phases) saw a rapid transformation of technology and economy. Rectilinear buildings made of mud-brick, the plough, the warp-weighted loom and clay pot stands are among the characteristic introductions. Cattle were reintroduced, together with the donkey. The succeeding Early Bronze Age is divided into three general phases (Early Cypriot I - III) - a continuous process of development and population increase. Marki Alonia is the best excavated settlement of this period. Marki Alonia and Sotira Kaminoudhia are excavated settlements. Many cemeteries are known, the most important of which is Bellapais Vounous on the North coast.Middle Bronze Age

The Middle Bronze Age, which follows the Early Bronze Age (1900–1600 BC), is a relatively short period and its earlier part is marked by peaceful development. The Middle Bronze Age is known from several excavated settlements: Marki Alonia, Alambra Mouttes and Pyrgos Mavroraki. These give evidence of economy and architecture of the period. From Alambra and Marki in central Cyprus we know that the houses were rectangular with many rooms, with lanes allowing people to move freely in the community. At the end of the Middle Bronze Age,fortress

A fortification (also called a fort, fortress, fastness, or stronghold) is a military construction designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from L ...

es were built in various places, a clear indication of unrest, although the cause is uncertain.

The most important cemeteries are at Bellapais, Lapithos, Kalavasos and Deneia. An extensive collection of Bronze Age pottery can be seen online from the cemeteries at Deneia.

The up to now oldest copper workshops have been excavated at Pyrgos-Mavroraki, 90 km southwest of Nicosia

Nicosia, also known as Lefkosia and Lefkoşa, is the capital and largest city of Cyprus. It is the southeasternmost of all EU member states' capital cities.

Nicosia has been continuously inhabited for over 5,500 years and has been the capi ...

. Cyprus was known as '' Alashiya'', the name is preserved in Egyptian, Hittite, Assyrian and Ugaritic documents. The first recorded name of a Cypriot king is ''Kushmeshusha'', as appears on letters sent to Ugarit in the 13th century BC.

Late Bronze Age

The beginning of the Late Bronze Age does not differ from the closing years of the previous period. Unrest, tension and anxiety mark all these years, probably because of some sort of engagement with theHyksos

The Hyksos (; Egyptian language, Egyptian ''wikt:ḥqꜣ, ḥqꜣ(w)-wikt:ḫꜣst, ḫꜣswt'', Egyptological pronunciation: ''heqau khasut'', "ruler(s) of foreign lands"), in modern Egyptology, are the kings of the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt ( ...

, who ruled Egypt at this time but were expelled from there in the mid-1500s BC. Soon afterwards peaceful conditions prevailed in the Eastern Mediterranean that witnessed a flowering of trade relations and the growing of urban centres. Chief among them was Enkomi, near modern Famagusta

Famagusta, also known by several other names, is a city located on the eastern coast of Cyprus. It is located east of the capital, Nicosia, and possesses the deepest harbour of the island. During the Middle Ages (especially under the maritime ...

, though several other harbour towns also sprang up along the southern coast of Cyprus. Around 1500 BC, Thutmose III

Thutmose III (variously also spelt Tuthmosis or Thothmes), sometimes called Thutmose the Great, (1479–1425 BC) was the fifth pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt. He is regarded as one of the greatest warriors, military commanders, and milita ...

claimed Cyprus and imposed a tax on the island.

Literacy was introduced to Cyprus with the Cypro-Minoan syllabary, a derivation from Cretan Linear A

Linear A is a writing system that was used by the Minoans of Crete from 1800 BC to 1450 BC. Linear A was the primary script used in Minoan palaces, palace and religious writings of the Minoan civilization. It evolved into Linear B, ...

. It was first used in early phases of the late Bronze Age (LCIB, 14th century BC) and continued in use for c. 400 years into the LC IIIB, maybe up to the second half of the 11th century BC. It likely evolved into the Cypriot syllabary

The Cypriot or Cypriote syllabary (also Classical Cypriot Syllabary) is a syllabary, syllabic script used in Iron Age Cyprus, from about the 11th to the 4th centuries BCE, when it was replaced by the Greek alphabet. It has been suggested that t ...

.

The Late Cypriot (LC) IIC (1300–1200 BC) was a time of local prosperity. Cities were rebuilt on a rectangular grid plan, like Enkomi, where the town gates now correspond to the grid axes and numerous grand buildings front the street system or newly founded. Great official buildings (constructed from

The Late Cypriot (LC) IIC (1300–1200 BC) was a time of local prosperity. Cities were rebuilt on a rectangular grid plan, like Enkomi, where the town gates now correspond to the grid axes and numerous grand buildings front the street system or newly founded. Great official buildings (constructed from ashlar

Ashlar () is a cut and dressed rock (geology), stone, worked using a chisel to achieve a specific form, typically rectangular in shape. The term can also refer to a structure built from such stones.

Ashlar is the finest stone masonry unit, a ...

-masonry

Masonry is the craft of building a structure with brick, stone, or similar material, including mortar plastering which are often laid in, bound, and pasted together by mortar (masonry), mortar. The term ''masonry'' can also refer to the buildin ...

) point to increased social hierarchisation and control. Some of these buildings contain facilities for processing and storing olive oil

Olive oil is a vegetable oil obtained by pressing whole olives (the fruit of ''Olea europaea'', a traditional Tree fruit, tree crop of the Mediterranean Basin) and extracting the oil.

It is commonly used in cooking for frying foods, as a cond ...

, like at Maroni-Vournes and "building X" at Kalavassos-Ayios Dhimitrios. Other ashlar-buildings are known from Palaeokastro. A Sanctuary with a horned altar constructed from ashlar-masonry has been found at Myrtou-Pigadhes, other temples have been located at Enkomi, Kition and Kouklia

Kouklia (, ) is a village in the Paphos District, about east from the city of Paphos on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus. The village is built in the area of "Palaepaphos" () (Paphos#Old Paphos, Old Paphos), mythical birthplace of Aphrodite, G ...

(Palaepaphos). Both the regular layout of the cities and the new masonry techniques find their closest parallels in Syria, especially in Ugarit

Ugarit (; , ''ủgrt'' /ʾUgarītu/) was an ancient port city in northern Syria about 10 kilometers north of modern Latakia. At its height it ruled an area roughly equivalent to the modern Latakia Governorate. It was discovered by accident in 19 ...

(modern Ras Shamra

Ugarit (; , ''ủgrt'' /ʾUgarītu/) was an ancient port city in northern Syria about 10 kilometers north of modern Latakia. At its height it ruled an area roughly equivalent to the modern Latakia Governorate. It was discovered by accident in 19 ...

).

Rectangular corbelled tombs point to close contacts with Syria and Canaan (probably around the emergence of ancient Israelites) as well. The practice of writing spread, and tablets in the Cypro-Minoan script have been found on the mainland as well (Ras Shamra). Ugaritic texts from Ras Shamra and Enkomi mention "Ya", the Assyrian name of Cyprus, that thus seems to have been in use already in the late Bronze Age.

Cyprus was, at some times, a part of the Hittite empire

The Hittites () were an Anatolian peoples, Anatolian Proto-Indo-Europeans, Indo-European people who formed one of the first major civilizations of the Bronze Age in West Asia. Possibly originating from beyond the Black Sea, they settled in mo ...

but was a client state and as such was not invaded but rather merely part of the empire by association and governed by the ruling kings of Ugarit.Thomas, Carol G. & Conant, C.: ''The Trojan War'', pages 121-122. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005. , 9780313325267. As such Cyprus was essentially "left alone with little intervention in Cypriot affairs". However, during the reign of Tudhaliya IV the island was briefly invaded by the Hittites for either reasons of securing the copper resource or as a way of preventing piracy. Shortly afterwards the island had to be reconquered again by his son Suppiluliuma II, around 1200 BC. Some towns (Enkomi, Kition, Palaeokastro and Sinda) show traces of destruction at the end of LC IIC. Originally, two waves of destruction, c. 1230 BC by the Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples were a group of tribes hypothesized to have attacked Ancient Egypt, Egypt and other Eastern Mediterranean regions around 1200 BC during the Late Bronze Age. The hypothesis was proposed by the 19th-century Egyptology, Egyptologis ...

and 1190 BC by Aegean refugees

A refugee, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), is a person "forced to flee their own country and seek safety in another country. They are unable to return to their own country because of feared persecution as ...

, or 1190 and 1179 BC according to Paul Aström had been proposed. Some smaller settlements (Ayios Dhimitrios and Kokkinokremnos

Pyla-Kokkinokremos () (red cliff)Excerpt of wall mounted text in exhibit room number 2 at Larnaca District Museum was a Late Bronze Age settlement on Cyprus, abandoned after a brief occupation.

History

The site of Pyla-Kokkinokremos, located on ...

) were abandoned but do not show traces of destruction.

The years of peace that brought about such a flowering of culture and civilisation did not last. During these years Cyprus reached unprecedented heights in prosperity and it played a rather neutral role in the differences of her powerful neighbours.

Rich finds from this period testify to a vivid commerce with other countries. We have jewellery

Jewellery (or jewelry in American English) consists of decorative items worn for personal adornment such as brooches, ring (jewellery), rings, necklaces, earrings, pendants, bracelets, and cufflinks. Jewellery may be attached to the body or the ...

and other precious objects from the Aegean along with pottery that prove the close connections of the two areas, though finds coming from Near East

The Near East () is a transcontinental region around the Eastern Mediterranean encompassing the historical Fertile Crescent, the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and coastal areas of the Arabian Peninsula. The term was invented in the 20th ...

ern countries are also plentiful.

In the later phase of the late Bronze Age (LCIIIA, 1200–1100 BC) great amounts of "Mycenaean" IIIC:1b pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other raw materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. The place where such wares are made by a ''potter'' is al ...

were produced locally. New architectural features include Cyclopean walls

Cyclopean masonry is a type of stonework found in Mycenaean architecture, built with massive limestone boulders, roughly fitted together with minimal clearance between adjacent stones and with clay mortar or no use of mortar. The boulders typi ...

, found on the Greek mainland as well and a certain type of rectangular stepped capitals, endemic on Cyprus. Chamber tombs are given up in favour of shaft graves.

Cyprus was settled by Mycenaean Greeks by the end of the Bronze Age, beginning the Hellenization of the island. Large amounts of IIIC:1b pottery are found in Palestine during this period as well. There are finds that show close connections to Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

as well. In Hala Sultan Tekke Egyptian pottery has been found, among them wine jugs bearing the cartouche

upalt=A stone face carved with coloured hieroglyphics. Two cartouches - ovoid shapes with hieroglyphics inside - are visible at the bottom., Birth and throne cartouches of Pharaoh KV17.html" ;"title="Seti I, from KV17">Seti I, from KV17 at the ...

of Seti I

Menmaatre Seti I (or Sethos I in Greek language, Greek) was the second pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt during the New Kingdom of Egypt, New Kingdom period, ruling or 1290 BC to 1279 BC. He was the son of Ramesses I and Sitre, and th ...

and fish bones of the Nile perch

The Nile perch (''Lates niloticus''), also known as the African snook, Goliath perch, African barramundi, Goliath barramundi, Giant lates or the Victoria perch, is a species of freshwater fish in family Latidae of order Perciformes. It is wides ...

.

Another Greek wave of colonization is believed to have taken place in the following century (LCIIIB, 1100–1050), indicated, among other things, by a new type of graves (long dromoi) and Mycenean influences in pottery decoration.

Most authors claim that the Cypriot city kingdoms, first described in written sources in the 8th century BC were already founded in the 11th century BC. Other scholars see a slow process of increasing social complexity between the 12th and the 8th centuries, based on a network of chiefdoms. In the 8th century (geometric period) the number of settlements increases sharply and monumental tombs, like the 'Royal' tombs of Salamis appear for the first time. This could be a better indication for the appearance of the Cypriot kingdoms. This period shows the appearance of large urban centers.

Iron Age

TheIron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

follows the Submycenean period (1125–1050 BC) or Late Bronze Age and is divided into the:

* Geometric 1050–700 BC

* Archaic 700–525 BC

In the ensuing Early Iron Age Cyprus becomes predominantly Greek. Pottery shapes and decoration show a marked Aegean inspiration although Oriental ideas creep in from time to time. Pottery types also appear from other Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

cultures as evidenced from in archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

recovery on Cyprus of pottery from Cydonia, a powerful urban center of ancient Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

.C. Michael Hogan''Cydonia'', The Modern Antiquarian, Jan. 23, 2008

/ref> New burial customs with rock-cut chamber tombs having a long "dromos" (a ramp leading gradually towards the entrance) along with new religious beliefs speak in favour of the arrival of people from the Aegean. The same view is supported by the introduction of the safety pin that denotes a new fashion in dressing and also by a name scratched on a bronze skewer from Paphos and dating between 1050–950 BC. Foundations myths documented by classical authors connect the foundation of numerous Cypriot towns with immigrant Greek heroes in the wake of the

Trojan War

The Trojan War was a legendary conflict in Greek mythology that took place around the twelfth or thirteenth century BC. The war was waged by the Achaeans (Homer), Achaeans (Ancient Greece, Greeks) against the city of Troy after Paris (mytho ...

. For example, Teucer

In Greek mythology, Teucer (; , also Teucrus, Teucros or Teucris), was the son of King Telamon of Salamis Island and his second wife Hesione, daughter of King Laomedon of Troy. He fought alongside his half-brother, Ajax the Great, Ajax, in the ...

, the brother of Aias was supposed to have founded Salamis, and the Arcadian Agapenor of Tegea to have replaced the native ruler Kinyras and to have founded Paphos

Paphos, also spelled as Pafos, is a coastal city in southwest Cyprus and the capital of Paphos District. In classical antiquity, two locations were called Paphos: #Old Paphos, Old Paphos, today known as Kouklia, and #New Paphos, New Paphos. It i ...

. Some scholars see this a memory of a Greek colonisation already in the 11th century. In the 11th-century tomb 49 from Palaepaphos-Skales three bronze obeloi with inscriptions in Cypriot syllabic script have been found, one of which bears the name of Opheltas. This is the first indication of Greek language

Greek (, ; , ) is an Indo-European languages, Indo-European language, constituting an independent Hellenic languages, Hellenic branch within the Indo-European language family. It is native to Greece, Cyprus, Italy (in Calabria and Salento), south ...

use on the island, although it is written in the Cypriot syllabary that remained in use down to the 3rd century BC.

Cremation as a burial rite is seen as a Greek introduction as well. The first cremation burial in Bronze vessels has been found at Kourion-Kaloriziki, tomb 40, dated to the first half of the 11th century (LCIIIB). The shaft grave contained two bronze rod tripod stands, the remains of a shield, and a golden sceptre as well. Formerly seen as the Royal grave of first Argive founders of Kourion, it is now interpreted as the tomb of a native Cypriote or a Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

n prince. The cloisonné

Cloisonné () is an ancient technology, ancient technique for decorating metalwork objects with colored material held in place or separated by metal strips or wire, normally of gold. In recent centuries, vitreous enamel has been used, but inla ...

enamelling of the sceptre head with the two falcons surmounting it has no parallels in the Aegean, but shows a strong Egyptian influence.

In the 8th century, numerous Phoenician colonies

Colonies in antiquity were post-Iron Age city-states founded from a mother-city or metropolis rather than from a territory-at-large. Bonds between a colony and its metropolis often remained close, and took specific forms during the period of clas ...

were founded, like Kart-Hadasht ('New Town'), present day Larnaca

Larnaca, also spelled Larnaka, is a city on the southeast coast of Cyprus and the capital of the Larnaca District, district of the same name. With a district population of 155.000 in 2021, it is the third largest city in the country after Nicosi ...

and Salamis. The oldest cemetery of Salamis has indeed produced children's burials in Canaanite jars, clear indication of Phoenician presence already in the LCIIIB (11th century). Similar jar burials have been found in cemeteries in Kourion-Kaloriziki and Palaepaphos-Skales near Kouklia. In Skales, many Levantine imports and Cypriote imitations of Levantine forms have been found and point to a Phoenician expansion even before the end of the 11th century.

The 8th century BC saw a marked increase of wealth in Cyprus. Communications to the east and west were on the ascent and this created a prosperous society. Testifying to this wealth are the so-called royal tombs of Salamis, which, although plundered, produced a truly royal abundance of wealth. Sacrifices of horses, bronze tripods and huge cauldrons decorated with sirens, griffins etc., chariots with all their ornamentation and the horses' gear, ivory beds and thrones exquisitely decorated were all deposited into the tombs' "dromoi" for the sake of their masters.

The late 8th century is the time of the spreading of the Homeric poems, the "Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

" and the "Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; ) is one of two major epics of ancient Greek literature attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest surviving works of literature and remains popular with modern audiences. Like the ''Iliad'', the ''Odyssey'' is divi ...

". Funerary customs at Salamis and elsewhere were greatly influenced by these poems. The deceased were given skewers and firelogs in order to roast their meat, a practice found in contemporary Argos and Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

, recalling the similar gear of Achilles

In Greek mythology, Achilles ( ) or Achilleus () was a hero of the Trojan War who was known as being the greatest of all the Greek warriors. The central character in Homer's ''Iliad'', he was the son of the Nereids, Nereid Thetis and Peleus, ...

when he entertained other Greek heroes in his tent. Honey and oil, described by Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

as offerings to the dead are also found at Salamis, and the flames of fire that consumed the deceased were quenched with wine as it happened to Patroclus

In Greek mythology, Patroclus (generally pronounced ; ) was a Greek hero of the Trojan War and an important character in Homer's ''Iliad''. Born in Opus, Patroclus was the son of the Argonaut Menoetius. When he was a child, he was exiled from ...

' body after it was given to the flames. The hero's ashes were gathered carefully wrapped into a linen cloth and put into a golden urn.

At Salamis the ashes of the deceased are also wrapped into a cloth and deposited into a bronze cauldron.

The Prehistoric Period came to an end with the writing of the first works that still survive, first by the Assyrians

Assyrians (, ) are an ethnic group indigenous to Mesopotamia, a geographical region in West Asia. Modern Assyrians share descent directly from the ancient Assyrians, one of the key civilizations of Mesopotamia. While they are distinct from ot ...

, then by Greeks and Romans.

Genetic studies

Neolithic Cyprus

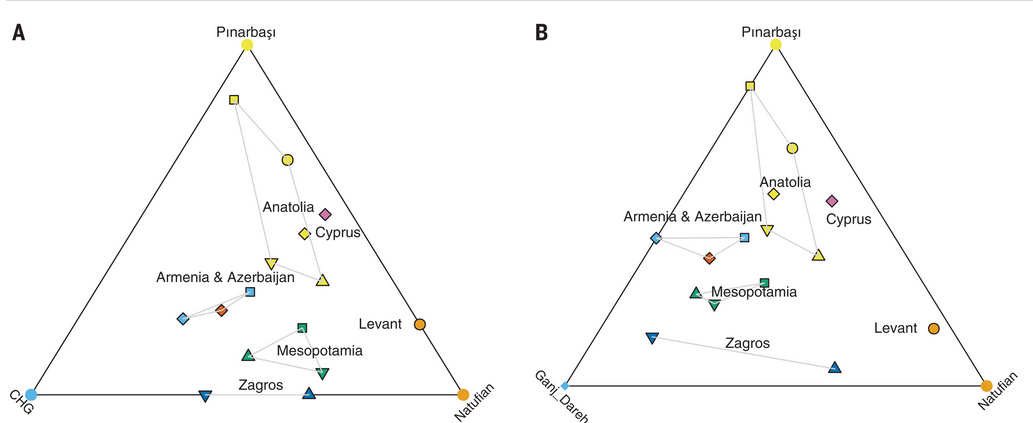

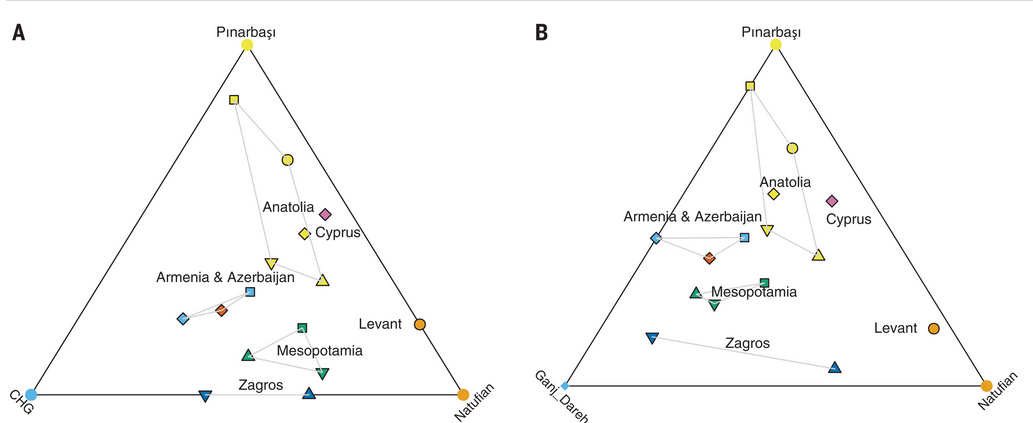

In theirarchaeogenetics

Archaeogenetics is the study of ancient DNA using various molecular genetic methods and DNA resources. This form of genetic analysis can be applied to human, animal, and plant specimens. Ancient DNA can be extracted from various fossilized spec ...

study, Lazaridis et al. (2022) carried out principal components analysis (PCA), projecting the ancient individuals onto the variation of present-day West Eurasians. They discovered that Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

Cypriots genetically clustered with Neolithic Anatolians. Two main clusters emerge: an “Eastern Mediterranean” Anatolian/Levantine cluster that also includes the geographically intermediate individuals from Cyprus, and an “inland” Zagros-Caucasus-Mesopotamia-Armenia-Azerbaijan cluster. There is structure within these groupings. Anatolian individuals group with each other and with those from Cyprus, whereas Levantine individuals are distinct.

During the

During the Neolithic era

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

the highest proportion of Anatolian Neolithic-related ancestry is observed in Neolithic Anatolian populations as well as Neolithic Aegeans and the early farmers of Cyprus. The high Anatolian-related ancestry in Cyprus revealed by their model and subsequent analyses sheds light on debates about the origins of the people who spread Pre-Pottery Neolithic

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN) represents the early Neolithic in the Near East, dating to years ago, (10000 – 6500 BCE).Richard, Suzanne ''Near Eastern archaeology'' Eisenbrauns; illustrated edition (1 Aug 2004) p.24/ref> It succeeds the ...

culture to Cyprus. Parallels in subsistence, technology, settlement organization, and ideological indicators suggest close contacts between Pre-Pottery Neolithic B

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) is part of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, a Neolithic culture centered in upper Mesopotamia and the Levant, dating to years ago, that is, 8800–6500 BC. It was Type site, typed by British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon ...

people in Cyprus and on the mainland, but the geographic source of the Cypriot Pre-Pottery Neolithic

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN) represents the early Neolithic in the Near East, dating to years ago, (10000 – 6500 BCE).Richard, Suzanne ''Near Eastern archaeology'' Eisenbrauns; illustrated edition (1 Aug 2004) p.24/ref> It succeeds the ...

populations has been unclear, with many possible points of origin. An inland Middle Euphrates

The Euphrates ( ; see #Etymology, below) is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of West Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia (). Originati ...

source has been suggested on the basis of architectural and artifactual similarities. However, the faunal record at Cypriot Pre-Pottery Neolithic B

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) is part of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, a Neolithic culture centered in upper Mesopotamia and the Levant, dating to years ago, that is, 8800–6500 BC. It was Type site, typed by British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon ...

sites and the use of Anatolian obsidian as raw material suggest linkages with Central and Southern Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, and the genetic data increase the weight of evidence in favor of this scenario of a primary source in Anatolia.

See also

* Cyprus dwarf hippopotamus * Cyprus dwarf elephantReferences

Bibliography

* Bernard Knapp, A. ''Prehistoric and Protohistoric Cyprus''. Oxford University Press, 2008. * Clarke, Joanne, with contributions by Carole McCartney and Alexander Wasse. ''On the Margins of Southwest Asia: Cyprus during the 6th to 4th Millennia BC''. * Gitin S., A. Mazar, E. Stern (eds.), Mediterranean Peoples in Transition, Thirteenth to Early Tenth Centuries BCE (Jerusalem, Israel exploration Society 1998). Late Bronze Age and transition to the Iron Age. * Muhly J. D. ''The role of the Sea People in Cyprus during the LCIII period''. In: V. Karageorghis/J. D. Muhly (eds), ''Cyprus at the close of the Bronze Age (Nicosia 1984)'', 39–55. End of Bronze Age * * Swiny, Stuart (2001) ''Earliest Prehistory of Cyprus'', American School of Oriental Research * Tatton-Brown, Veronica. ''Cyprus BC, 7000 Years of History'' (London, British Museum 1979). * Webb J. M. and D. Frankel, ''Characterising the Philia facies''. Material culture, chronology and the origins of the Bronze Age in Cyprus. American Journal of Archaeology 103, 1999, 3-43.External links

Archaeology and history of Cyprus

* Deneia Bronze Age potter

Ancient History of Cyprus, by Cypriot government

. {{Europe topic , Prehistory of Prehistoric Cyprus,

Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...