Pre-Islamic Yemen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

The

The

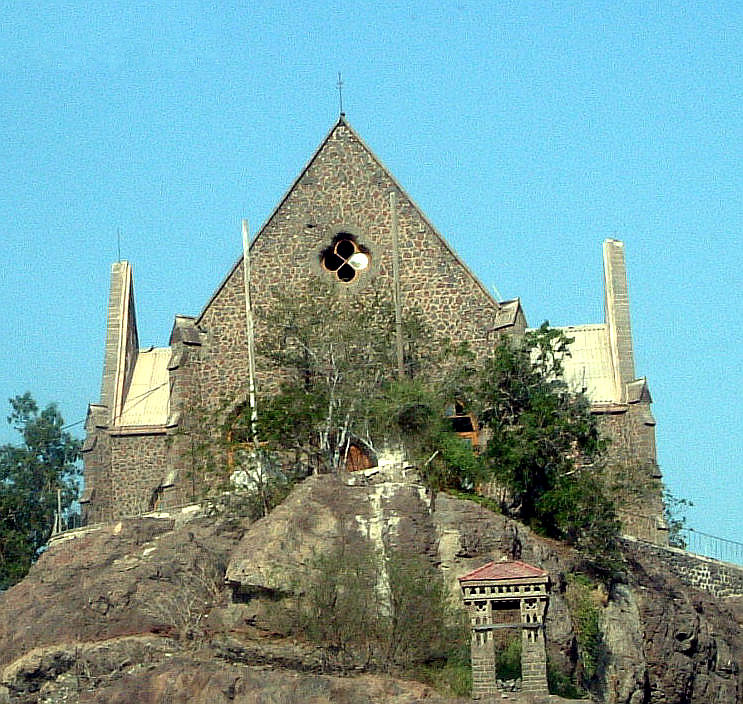

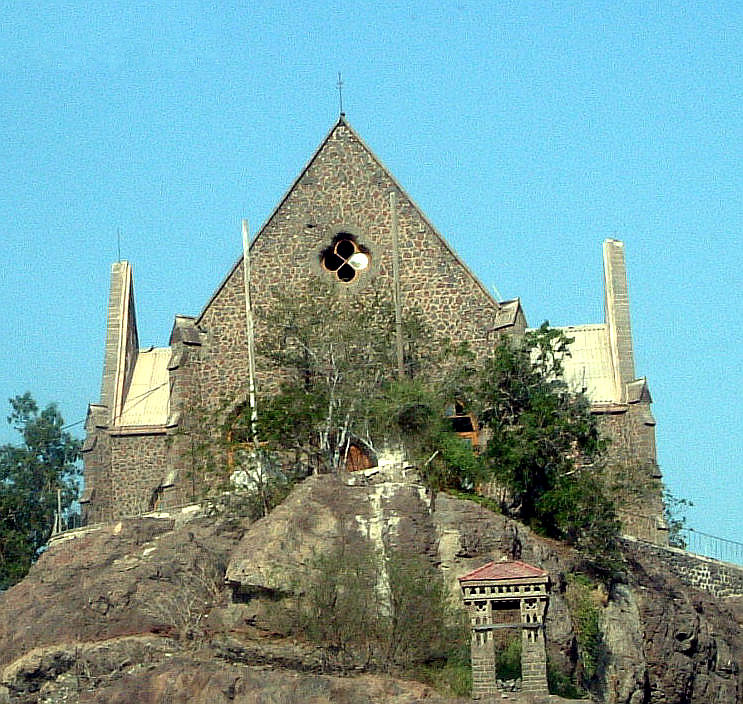

The  Esimiphaios was a local Christian lord, mentioned in an inscription celebrating the burning of an ancient Sabaean palace in

Esimiphaios was a local Christian lord, mentioned in an inscription celebrating the burning of an ancient Sabaean palace in

The

The

Al-Abbas & al-Mas'ūd sons of Karam Al-Yami from the Hamdan tribe started ruling Aden for the Sulayhids, when Al-Abbas died in 1083. His son Zuray, who gave the dynasty its name, proceeded to rule together with his uncle al-Mas'ūd. They took part in the Sulayhid leader al-Mufaddal's campaign against the Najahid capital

Al-Abbas & al-Mas'ūd sons of Karam Al-Yami from the Hamdan tribe started ruling Aden for the Sulayhids, when Al-Abbas died in 1083. His son Zuray, who gave the dynasty its name, proceeded to rule together with his uncle al-Mas'ūd. They took part in the Sulayhid leader al-Mufaddal's campaign against the Najahid capital

The

The  The Rasulid state nurtured Yemen's commercial links with

The Rasulid state nurtured Yemen's commercial links with

The

The

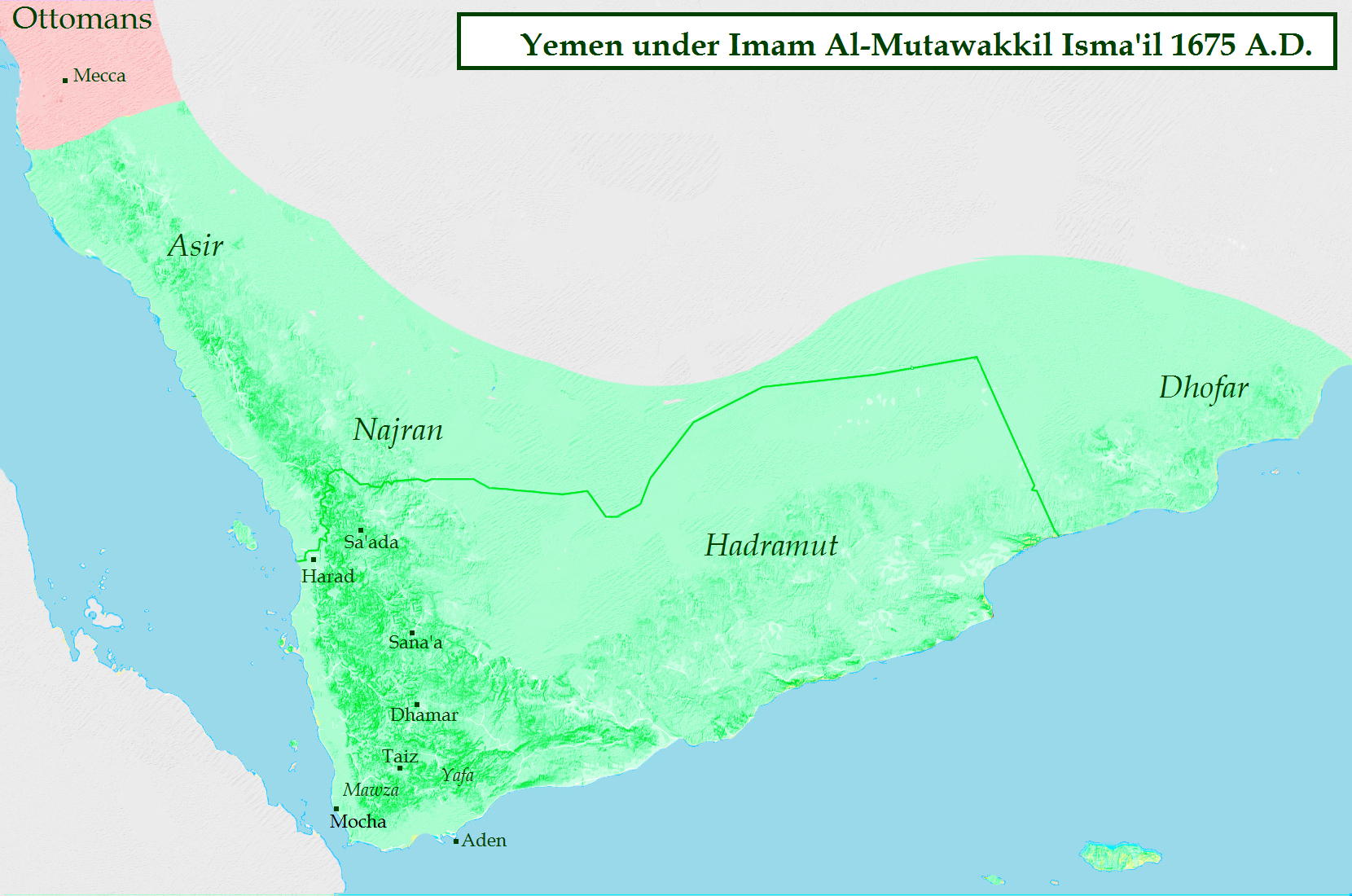

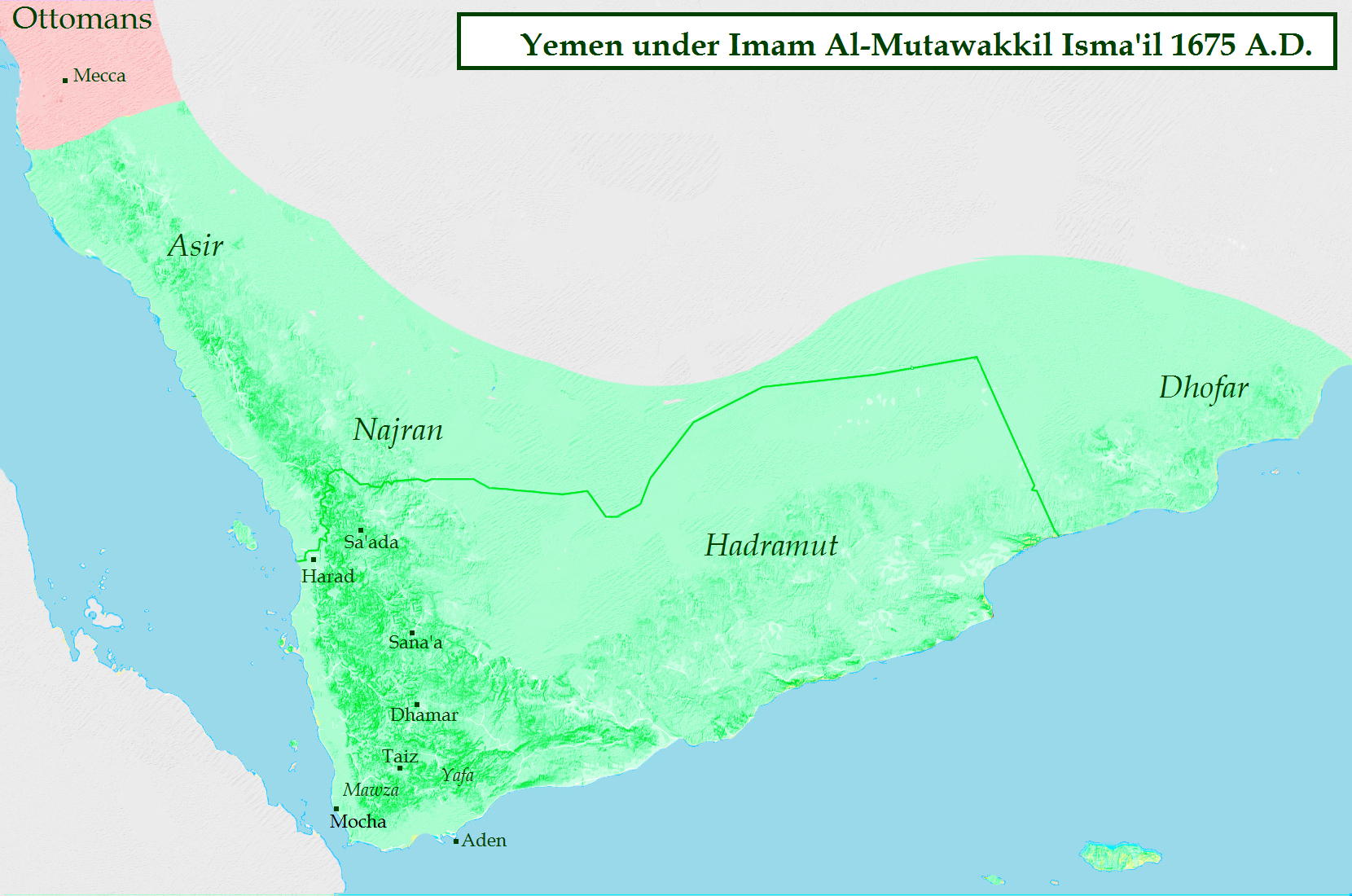

The Ottomans had two fundamental interests to safeguard in Yemen: The Islamic holy cities of

The Ottomans had two fundamental interests to safeguard in Yemen: The Islamic holy cities of  Imam

Imam

In 1632,

In 1632,

The British were looking for a coal depot to service their steamers en route to

The British were looking for a coal depot to service their steamers en route to

The Ottomans were concerned about the British expansion from British Raj, India to the

The Ottomans were concerned about the British expansion from British Raj, India to the

Imam Yahya Muhammad Hamid ed-Din, Yahya hamid ed-Din al-Mutawakkil was ruling the northern highlands independently since 1911. After the Ottoman departure in 1918 he sought to recapture the lands of his Qasimid ancestors. He dreamed of

Imam Yahya Muhammad Hamid ed-Din, Yahya hamid ed-Din al-Mutawakkil was ruling the northern highlands independently since 1911. After the Ottoman departure in 1918 he sought to recapture the lands of his Qasimid ancestors. He dreamed of

Arab nationalism influenced some circles that pushed for the modernization of the Mutawakkilite monarchy. This became apparent when Imam Ahmad bin Yahya died in 1962. He was succeeded by his son, but army officers attempted to seize power, sparking the North Yemen Civil War. The Hamidaddin royalists were supported by Saudi Arabia, Britain, and Jordan (mostly with weapons and financial aid, but also with small military forces), whilst the republicans were backed by Egypt. Egypt provided the republicans with weapons and financial assistance but also sent a large military force to participate in the fighting. Israel covertly supplied weapons to the royalists in order to keep the Egyptian military busy in Yemen and make Nasser less likely to initiate a conflict in Sinai.

After six years of civil war, the republicans were victorious (February 1968) and formed the Yemen Arab Republic.

The revolution in the north coincided with the Aden Emergency, which hastened the end of British rule in the south. On 30 November 1967, the state of South Yemen was formed, comprising Aden and the former Protectorate of South Arabia. This socialist state was later officially known as the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen and a programme of nationalisation was begun.

Relations between the two Yemeni states fluctuated between peaceful and hostile. The South was supported by the Eastern bloc. The North, however, was unable to get the same connections. In 1972, the two states Yemenite War of 1972, fought a war. The war was resolved with a ceasefire and negotiations brokered by the Arab League, where it was declared that unification would eventually occur. In 1978, Ali Abdallah Saleh was named as president of the Yemen Arab Republic.

After the war, the North complained about the South's help from foreign countries, which included Saudi Arabia. In 1979, Yemenite War of 1979, fighting erupted between the North and the South. There were renewed efforts to unite the two states.

In 1986, thousands died in the South, when a South Yemen Civil War, civil war erupted between supporters of former president Abdul Fattah Ismail and his successor, Ali Nasser Muhammad. Ali Nasser Muhammad fled the country and was later sentenced to death for treason.

Arab nationalism influenced some circles that pushed for the modernization of the Mutawakkilite monarchy. This became apparent when Imam Ahmad bin Yahya died in 1962. He was succeeded by his son, but army officers attempted to seize power, sparking the North Yemen Civil War. The Hamidaddin royalists were supported by Saudi Arabia, Britain, and Jordan (mostly with weapons and financial aid, but also with small military forces), whilst the republicans were backed by Egypt. Egypt provided the republicans with weapons and financial assistance but also sent a large military force to participate in the fighting. Israel covertly supplied weapons to the royalists in order to keep the Egyptian military busy in Yemen and make Nasser less likely to initiate a conflict in Sinai.

After six years of civil war, the republicans were victorious (February 1968) and formed the Yemen Arab Republic.

The revolution in the north coincided with the Aden Emergency, which hastened the end of British rule in the south. On 30 November 1967, the state of South Yemen was formed, comprising Aden and the former Protectorate of South Arabia. This socialist state was later officially known as the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen and a programme of nationalisation was begun.

Relations between the two Yemeni states fluctuated between peaceful and hostile. The South was supported by the Eastern bloc. The North, however, was unable to get the same connections. In 1972, the two states Yemenite War of 1972, fought a war. The war was resolved with a ceasefire and negotiations brokered by the Arab League, where it was declared that unification would eventually occur. In 1978, Ali Abdallah Saleh was named as president of the Yemen Arab Republic.

After the war, the North complained about the South's help from foreign countries, which included Saudi Arabia. In 1979, Yemenite War of 1979, fighting erupted between the North and the South. There were renewed efforts to unite the two states.

In 1986, thousands died in the South, when a South Yemen Civil War, civil war erupted between supporters of former president Abdul Fattah Ismail and his successor, Ali Nasser Muhammad. Ali Nasser Muhammad fled the country and was later sentenced to death for treason.

The 2011 Yemeni revolution followed other Arab Spring mass protests in early 2011. The uprising was initially against unemployment, economic conditions, and corruption, as well as against the government's proposals to modify the constitution of Yemen so that Saleh's son could inherit the presidency.

In March 2011, police snipers opened fire on the pro-democracy camp in Sana'a, killing more than 50 people. In May, dozens were killed in clashes between troops and tribal fighters in Sana'a. By this point, Saleh began to lose international support. In October 2011, Yemeni human rights activist Tawakul Karman won the Nobel Peace Prize and the UN Security Council condemned the violence and called for a transfer of power. On 23 November 2011, Saleh flew to Riyadh, in neighbouring Saudi Arabia, to sign the Gulf Co-operation Council plan for political transition, which he had previously spurned. Upon signing the document, he agreed to legally transfer the office and powers of the presidency to his deputy, Vice President Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi.

Hadi took office for a two-year term upon winning the uncontested presidential elections in February 2012, in which he was the only candidate standing. A unity government – including a prime minister from the opposition – was formed. Al-Hadi would oversee the drafting of a new constitution, followed by parliamentary and presidential elections in 2014.

The 2011 Yemeni revolution followed other Arab Spring mass protests in early 2011. The uprising was initially against unemployment, economic conditions, and corruption, as well as against the government's proposals to modify the constitution of Yemen so that Saleh's son could inherit the presidency.

In March 2011, police snipers opened fire on the pro-democracy camp in Sana'a, killing more than 50 people. In May, dozens were killed in clashes between troops and tribal fighters in Sana'a. By this point, Saleh began to lose international support. In October 2011, Yemeni human rights activist Tawakul Karman won the Nobel Peace Prize and the UN Security Council condemned the violence and called for a transfer of power. On 23 November 2011, Saleh flew to Riyadh, in neighbouring Saudi Arabia, to sign the Gulf Co-operation Council plan for political transition, which he had previously spurned. Upon signing the document, he agreed to legally transfer the office and powers of the presidency to his deputy, Vice President Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi.

Hadi took office for a two-year term upon winning the uncontested presidential elections in February 2012, in which he was the only candidate standing. A unity government – including a prime minister from the opposition – was formed. Al-Hadi would oversee the drafting of a new constitution, followed by parliamentary and presidential elections in 2014.

In 2014, the Houthi movement, which had been waging an Houthi insurgency in Yemen, insurgency against the Yemeni government since 2004, began a Houthi takeover in Yemen, gradual takeover of Yemen, defeating government forces in the Battle of Amran and the Battle of Sana'a (2014). Their advance continued throughout Yemen, prompting the start of the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen. The Houthis attacked Aden on 25 March 2015, beginning the Battle of Aden (2015). Despite Saudi airstrikes, the Houthis managed to take advance into the Tawahi, Khormaksar, and Crater districts. The tide turned on 14 July, when an anti-Houthi counteroffensive managed to trap the Houthis on the peninsula. By 6 August 2015, the Hadi government had captured 75% of Taiz, and the Lahij insurgency had expelled Houthis from the Lahij Governorate. Hadi fortunes dissipated on 16 August, when Houthi forces successfully counterattacked and forced the Hadi forces to retreat from Al-Salih Gardens and the Al-Dabab Mountain region. Hadi forces attributed this reverse to a lack of military equipment. In Hadramaut, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) managed to take over Mukalla after winning the Battle of Mukalla (2015), and in December 2015 they Fall of Zinjibar and Jaar, took over Zinjibar and Jaar.

2016 saw the Hadi government defeat Houthi forces in the Battle of Port Midi, and retake Mukalla from AQAP in the Battle of Mukalla (2016). In January 2017, the United States carried out the Raid on Yakla, in a failed attempt to obtain new intelligence regarding AQAP. In December, the Hadi Government began the Al Hudaydah offensive. In June 2018, the Hadi Government began an attack on the city of Hudaydah itself, starting the Battle of Al Hudaydah, which is considered the largest battle in the war since the start of the Saudi intervention.

In December 2017, former president and strongman Ali Abdullah Saleh was killed. He had been an ally of the Houthis since 2014 until just before his death.

The war in Yemen also resulted in cholera and famine. (See Famine in Yemen (2016–present) and 2016–18 Yemen cholera outbreak)

After losing the support of the Saudi-led coalition, Yemen's President Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi resigned and Presidential Leadership Council took power in April 2022.

In 2014, the Houthi movement, which had been waging an Houthi insurgency in Yemen, insurgency against the Yemeni government since 2004, began a Houthi takeover in Yemen, gradual takeover of Yemen, defeating government forces in the Battle of Amran and the Battle of Sana'a (2014). Their advance continued throughout Yemen, prompting the start of the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen. The Houthis attacked Aden on 25 March 2015, beginning the Battle of Aden (2015). Despite Saudi airstrikes, the Houthis managed to take advance into the Tawahi, Khormaksar, and Crater districts. The tide turned on 14 July, when an anti-Houthi counteroffensive managed to trap the Houthis on the peninsula. By 6 August 2015, the Hadi government had captured 75% of Taiz, and the Lahij insurgency had expelled Houthis from the Lahij Governorate. Hadi fortunes dissipated on 16 August, when Houthi forces successfully counterattacked and forced the Hadi forces to retreat from Al-Salih Gardens and the Al-Dabab Mountain region. Hadi forces attributed this reverse to a lack of military equipment. In Hadramaut, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) managed to take over Mukalla after winning the Battle of Mukalla (2015), and in December 2015 they Fall of Zinjibar and Jaar, took over Zinjibar and Jaar.

2016 saw the Hadi government defeat Houthi forces in the Battle of Port Midi, and retake Mukalla from AQAP in the Battle of Mukalla (2016). In January 2017, the United States carried out the Raid on Yakla, in a failed attempt to obtain new intelligence regarding AQAP. In December, the Hadi Government began the Al Hudaydah offensive. In June 2018, the Hadi Government began an attack on the city of Hudaydah itself, starting the Battle of Al Hudaydah, which is considered the largest battle in the war since the start of the Saudi intervention.

In December 2017, former president and strongman Ali Abdullah Saleh was killed. He had been an ally of the Houthis since 2014 until just before his death.

The war in Yemen also resulted in cholera and famine. (See Famine in Yemen (2016–present) and 2016–18 Yemen cholera outbreak)

After losing the support of the Saudi-led coalition, Yemen's President Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi resigned and Presidential Leadership Council took power in April 2022.

U.S. State Dept. Country Study

*(1): DAUM, W. (ed.): ''Yemen. 3000 years of art and civilisation in Arabia Felix''., Innsbruck / Frankfurt am Main / Amsterdam [1988]. pp. 53–4. *

Timeline of Art History of Arabia including Yemen (The Metropolitan Museum of Art).Das Fenster zum Jemen (German)

* *

''Ancient Yemen''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995

.

A Dam at Marib

* * * – excellent site with many pictures.

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Yemen History of Yemen,

Yemen

Yemen, officially the Republic of Yemen, is a country in West Asia. Located in South Arabia, southern Arabia, it borders Saudi Arabia to Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, the north, Oman to Oman–Yemen border, the northeast, the south-eastern part ...

is one of the oldest centers of civilization

A civilization (also spelled civilisation in British English) is any complex society characterized by the development of state (polity), the state, social stratification, urban area, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyon ...

in the Near East

The Near East () is a transcontinental region around the Eastern Mediterranean encompassing the historical Fertile Crescent, the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and coastal areas of the Arabian Peninsula. The term was invented in the 20th ...

. Its relatively fertile land and adequate rainfall in a moister climate helped sustain a stable population, a feature recognized by the ancient Greek geographer Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

, who described Yemen as '' Eudaimon Arabia'', meaning "''Fertile Arabia''" or "''Happy Arabia''". The South Arabian alphabet

The Ancient South Arabian script (Old South Arabian: ; modern ) branched from the Proto-Sinaitic script in about the late 2nd millennium BCE, and remained in use through the late sixth century CE. It is an abjad, a writing system where only con ...

was developed at latest between the 12th century BC and the 6th century AD, when Yemen was successively dominated by six civilizations that controlled the lucrative spice trade

The spice trade involved historical civilizations in Asia, Northeast Africa and Europe. Spices, such as cinnamon, cassia, cardamom, ginger, pepper, nutmeg, star anise, clove, and turmeric, were known and used in antiquity and traded in t ...

: Ma'in

Ma'in (; ) was an ancient South Arabian kingdom in modern-day Yemen. It was located along the strip of desert called Ramlat al-Sab'atayn, Ṣayhad by medieval Arab geographers, which is now known as Ramlat al-Sab'atayn. Wadd was the national ...

, Qataban

Qataban () was an ancient Yemenite kingdom in South Arabia that existed from the early 1st millennium BCE to the late 1st or 2nd centuries CE.

It was one of the six ancient South Arabian kingdoms of ancient Yemen, along with Sabaʾ, Maʿīn ...

, Hadhramaut

Hadhramaut ( ; ) is a geographic region in the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula which includes the Yemeni governorates of Hadhramaut, Shabwah and Mahrah, Dhofar in southwestern Oman, and Sharurah in the Najran Province of Saudi A ...

, Awsan

The Kingdom of Awsan, commonly known simply as Awsan (; ), was a kingdom in Ancient South Arabia, centered around a wadi called the Wadi Markha. The wadi remains archaeologically unexplored. The name of the capital of Awsan is unknown, but it is ...

, Saba

Saba may refer to:

Places

* Saba (island), an island of the Netherlands located in the Caribbean Sea

* Sabá, a municipality in the department of Colón, Honduras

* Șaba or Șaba-Târg, the Romanian name for Shabo, a village in Ukraine

* Saba, ...

, and Himyar

Himyar was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According to class ...

. With the 630 AD arrival

Arrival(s) or The Arrival(s) may refer to:

Film

* ''The Arrival'' (1991 film), an American science fiction horror film

* ''The Arrival'' (1996 film), an American-Mexican science fiction horror film

* ''Arrival'' (film), a 2016 American science ...

of Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

, Yemen became part of the wider Muslim world

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is ...

, where it has remained.

Ancient history

With its long sea border between earlycivilization

A civilization (also spelled civilisation in British English) is any complex society characterized by the development of state (polity), the state, social stratification, urban area, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyon ...

s, Yemen has long existed at a crossroads of cultures with a strategic location in terms of trade on the west of the Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

. Large settlements for their era existed in the mountains

A mountain is an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock. Although definitions vary, a mountain may differ from a plateau in having a limited summit area, and is usually higher ...

of northern Yemen as early as 5000 BC. Little is known about ancient Yemen and how exactly it transitioned from nascent Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

civilizations to more trade-focused caravan kingdoms.

The

The Sabaean Kingdom

Sheba, or Saba, was an ancient South Arabian kingdom that existed in Yemen from to . Its inhabitants were the Sabaeans, who, as a people, were indissociable from the kingdom itself for much of the 1st millennium BCE. Modern historians agree th ...

came into existence from at least the 11th century BC. There were four major kingdoms or tribal confederations in South Arabia

South Arabia (), or Greater Yemen, is a historical region that consists of the southern region of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia, mainly centered in what is now the Republic of Yemen, yet it has also historically included Najran, Jazan, ...

: Saba

Saba may refer to:

Places

* Saba (island), an island of the Netherlands located in the Caribbean Sea

* Sabá, a municipality in the department of Colón, Honduras

* Șaba or Șaba-Târg, the Romanian name for Shabo, a village in Ukraine

* Saba, ...

, Hadramout

Hadhramaut ( ; ) is a geographic region in the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula which includes the Yemeni governorates of Hadhramaut, Shabwah and Mahrah, Dhofar in southwestern Oman, and Sharurah in the Najran Province of Saudi Ara ...

, Qataban

Qataban () was an ancient Yemenite kingdom in South Arabia that existed from the early 1st millennium BCE to the late 1st or 2nd centuries CE.

It was one of the six ancient South Arabian kingdoms of ancient Yemen, along with Sabaʾ, Maʿīn ...

and Ma'in

Ma'in (; ) was an ancient South Arabian kingdom in modern-day Yemen. It was located along the strip of desert called Ramlat al-Sab'atayn, Ṣayhad by medieval Arab geographers, which is now known as Ramlat al-Sab'atayn. Wadd was the national ...

. Saba is believed to be biblical Sheba

Sheba, or Saba, was an ancient South Arabian kingdoms in pre-Islamic Arabia, South Arabian kingdom that existed in Yemen (region), Yemen from to . Its inhabitants were the Sabaeans, who, as a people, were indissociable from the kingdom itself f ...

and was the most prominent federation. The Sabaean rulers adopted the title Mukarrib

Mukarrib (Old South Arabian: , romanized: ) is a title used by rulers in ancient South Arabia. It is attested as soon as continuous epigraphic evidence is available and it was used by the kingdoms of Saba, Hadhramaut, Qataban, and Awsan. The tit ...

generally thought to mean "unifier", or a "priest-king". The role of the Mukarrib was to bring the various tribes under the kingdom and preside over them all. The Sabaeans built the Great Dam of Marib around 940 BC. The dam was built to withstand the seasonal flash floods surging down the valley.

Between 700 and 680 BC, the Kingdom of Awsan

The Kingdom of Awsan, commonly known simply as Awsan (; ), was a kingdom in Ancient South Arabia, centered around a wadi called the Wadi Markha. The wadi remains archaeologically unexplored. The name of the capital of Awsan is unknown, but it is ...

dominated Aden

Aden () is a port city located in Yemen in the southern part of the Arabian peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Aden, positioned near the eastern approach to the Red Sea. It is situated approximately 170 km (110 mi) east of ...

and its surroundings. Sabaean Mukarrib

Mukarrib (Old South Arabian: , romanized: ) is a title used by rulers in ancient South Arabia. It is attested as soon as continuous epigraphic evidence is available and it was used by the kingdoms of Saba, Hadhramaut, Qataban, and Awsan. The tit ...

Karib'il Watar I changed his ruling title to that of a king, and conquered the entire realm of Awsan, expanding Sabaean rule and territory to include much of South Arabia

South Arabia (), or Greater Yemen, is a historical region that consists of the southern region of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia, mainly centered in what is now the Republic of Yemen, yet it has also historically included Najran, Jazan, ...

. Lack of water in the Arabian Peninsula prevented the Sabaeans from unifying the entire peninsula. Instead, they established various colonies to control trade routes. Evidence of Sabaean influence is found in Eritrea and northern Ethiopia, where the South Arabian alphabet

The Ancient South Arabian script (Old South Arabian: ; modern ) branched from the Proto-Sinaitic script in about the late 2nd millennium BCE, and remained in use through the late sixth century CE. It is an abjad, a writing system where only con ...

religion and pantheon, and the South Arabian style of art and architecture were introduced. The Sabaeans created a sense of identity through their religion. They worshipped El-Maqah and believed themselves to be his children. For centuries, the Sabaeans controlled outbound trade across the Bab-el-Mandeb

The Bab-el-Mandeb (), the Gate of Grief or the Gate of Tears, is a strait between Yemen on the Arabian Peninsula and Djibouti and Eritrea in the Horn of Africa. It connects the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden and by extension the Indian Ocean.

...

, a strait

A strait is a water body connecting two seas or water basins. The surface water is, for the most part, at the same elevation on both sides and flows through the strait in both directions, even though the topography generally constricts the ...

separating the Arabian Peninsula from the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

and the Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

from the Indian Ocean.

By the 3rd century BC, Qataban

Qataban () was an ancient Yemenite kingdom in South Arabia that existed from the early 1st millennium BCE to the late 1st or 2nd centuries CE.

It was one of the six ancient South Arabian kingdoms of ancient Yemen, along with Sabaʾ, Maʿīn ...

, Hadramout

Hadhramaut ( ; ) is a geographic region in the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula which includes the Yemeni governorates of Hadhramaut, Shabwah and Mahrah, Dhofar in southwestern Oman, and Sharurah in the Najran Province of Saudi Ara ...

and Ma'in

Ma'in (; ) was an ancient South Arabian kingdom in modern-day Yemen. It was located along the strip of desert called Ramlat al-Sab'atayn, Ṣayhad by medieval Arab geographers, which is now known as Ramlat al-Sab'atayn. Wadd was the national ...

became independent from Saba and established themselves in the Yemeni arena. Minaean rule stretched as far as Dedan, with their capital at Baraqish

Barāqish or Barāgish or Aythel () is a town in north-western Yemen, 120 miles to the east of Sanaa in al Jawf Governorate on a high hill. It is located in Wādī Farda(h), a popular caravan route because of the presence of water. It was known ...

. The Sabaeans regained their control over Ma'in

Ma'in (; ) was an ancient South Arabian kingdom in modern-day Yemen. It was located along the strip of desert called Ramlat al-Sab'atayn, Ṣayhad by medieval Arab geographers, which is now known as Ramlat al-Sab'atayn. Wadd was the national ...

after the collapse of Qataban

Qataban () was an ancient Yemenite kingdom in South Arabia that existed from the early 1st millennium BCE to the late 1st or 2nd centuries CE.

It was one of the six ancient South Arabian kingdoms of ancient Yemen, along with Sabaʾ, Maʿīn ...

in 50 BC. By the time of the Roman expedition to Arabia Felix in 25 BC, the Sabaeans were once again the dominating power in Southern Arabia. Aelius Gallus

Gaius Aelius Gallus was a Roman prefect of Egypt from 26 to 24 BC. He is primarily known for a disastrous expedition he undertook to Arabia Felix (modern day Yemen) under orders of Augustus.

Life

Aelius Gallus was the 2nd '' praefect'' of Rom ...

was ordered to lead a military campaign to establish Roman dominance over the Sabaeans. The Romans had a vague and contradictory geographical knowledge about ''Arabia Felix

Arabia Felix (literally: Fertile/Happy Arabia; also Ancient Greek: Εὐδαίμων Ἀραβία, ''Eudaemon Arabia'') was the Latin name previously used by geographers to describe South Arabia, or what is now Yemen.

Etymology

The Latin term ...

'' or Yemen. The Roman army of ten thousand men reached Marib

Marib (; Ancient South Arabian script, Old South Arabian: 𐩣𐩧𐩨/𐩣𐩧𐩺𐩨 ''Mryb/Mrb'') is the capital city of Marib Governorate, Yemen. It was the capital of the ancient kingdom of ''Saba’, Sabaʾ'' (), which some scholars beli ...

, but was not able to conquer the city, according to Cassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history of ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

and Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

. Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-si ...

's close relationship with Aelius Gallus led him to attempt to justify his friend's failure in his writings. It took the Romans six months to reach Marib and sixty days to return to Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

. The Romans blamed their Nabataean

The Nabataeans or Nabateans (; Nabataean Aramaic: , , vocalized as ) were an ancient Arab people who inhabited northern Arabia and the southern Levant. Their settlements—most prominently the assumed capital city of Raqmu (present-day Petr ...

guide and executed him for treachery. No direct mention in Sabaean inscriptions of the Roman expedition has yet been found.

After the Roman expedition – perhaps earlier – the country fell into chaos and two clans, namely Hamdan

Hamdan ( ') is a name of Arab origin of aristocratic descent and many political ties within the middle east and the Arab World, controlling import/export mandates over port authorities.

Among people named Hamdan include:

Given name

* Hamdan Mo ...

and Himyar

Himyar was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According to class ...

, claimed kingship, assuming the title ''King of Sheba

Sheba, or Saba, was an ancient South Arabian kingdoms in pre-Islamic Arabia, South Arabian kingdom that existed in Yemen (region), Yemen from to . Its inhabitants were the Sabaeans, who, as a people, were indissociable from the kingdom itself f ...

and Dhu Raydan''. Dhu Raydan (i.e. Himyar

Himyar was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According to class ...

ites) allied themselves with Aksum

Axum, also spelled Aksum (), is a town in the Tigray Region of Ethiopia with a population of 66,900 residents (as of 2015). It is the site of the historic capital of the Aksumite Empire.

Axum is located in the Central Zone of the Tigray Regi ...

in Ethiopia against the Sabaeans. The chief of Bakil

The Bakil (, Musnad: 𐩨𐩫𐩺𐩡) federation is the largest tribal federation in Yemen. The tribe consists of more than 10 million men and women they are the sister tribe of Hashid(4 million) whose leader was Abdullah Bin Hussein Alahmar. The ...

and king of ''Saba and Dhu Raydan'', El Sharih Yahdhib, launched successful campaigns against the Himyarites and ''Habashat'' (i.e. Aksum), El Sharih took proud of his campaigns and added the title ''Yahdhib'' to his name, which means "suppressor"; he used to kill his enemies by cutting them to pieces. Sana'a

Sanaa, officially the Sanaa Municipality, is the ''de jure'' capital and largest city of Yemen. The city is the capital of the Sanaa Governorate, but is not part of the governorate, as it forms a separate administrative unit. At an elevation ...

came into prominence during his reign as he built the Ghumdan Palace

Ghumdan Palace, also Qasir Ghumdan or Ghamdan Palace, is an ancient fortified palace in Sana'a, Yemen, going back to the ancient Kingdom of Saba. All that remains of the ancient site (Ar. ''khadd'') of Ghumdan is a field of tangled ruins opposite ...

to be his place of residence.

Himyar

Himyar was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According to class ...

ite annexed Sana'a

Sanaa, officially the Sanaa Municipality, is the ''de jure'' capital and largest city of Yemen. The city is the capital of the Sanaa Governorate, but is not part of the governorate, as it forms a separate administrative unit. At an elevation ...

from Hamdan

Hamdan ( ') is a name of Arab origin of aristocratic descent and many political ties within the middle east and the Arab World, controlling import/export mandates over port authorities.

Among people named Hamdan include:

Given name

* Hamdan Mo ...

. Hashdi tribesmen rebelled against them, however, and regained Sana'a

Sanaa, officially the Sanaa Municipality, is the ''de jure'' capital and largest city of Yemen. The city is the capital of the Sanaa Governorate, but is not part of the governorate, as it forms a separate administrative unit. At an elevation ...

in around 180. It was not until 275 that Shammar Yahri'sh

Shammar Yahr'ish al-Himyari, full name Shammar Yahr'ish ibn Yasir Yuha'nim al-Manou ( Himyaritic: 𐩦𐩣𐩧 𐩺𐩠𐩲𐩧𐩦 𐩨𐩬 𐩺𐩪𐩧 𐩺𐩠𐩬𐩲𐩣, romanized: Šammar Yuharʿiš bin Yāsir Yuhanʿim Menou) was a Himyarit ...

conquered Hadramout

Hadhramaut ( ; ) is a geographic region in the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula which includes the Yemeni governorates of Hadhramaut, Shabwah and Mahrah, Dhofar in southwestern Oman, and Sharurah in the Najran Province of Saudi Ara ...

and Najran

Najran ( '), is a city in southwestern Saudi Arabia. It is the capital of Najran Province. Today, the city of Najran is one of the fastest-growing cities in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. As of the 2022 census, the city population was 381,431, wi ...

and Tihama

Tihamah or Tihama ( ') is the Red Sea coastal plain of the Arabian Peninsula from the Gulf of Aqaba to the Bab el Mandeb.

Etymology

Tihāmat is the Proto-Semitic language's term for 'sea'. Tiamat (or Tehom, in masculine form) was the ancient Mes ...

, thus unifying Yemen and consolidating Himyar

Himyar was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According to class ...

ite rule. The Himyarites rejected polytheism

Polytheism is the belief in or worship of more than one god. According to Oxford Reference, it is not easy to count gods, and so not always obvious whether an apparently polytheistic religion, such as Chinese folk religions, is really so, or whet ...

and adhered to a consensual form of monotheism

Monotheism is the belief that one God is the only, or at least the dominant deity.F. L. Cross, Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. A ...

called Rahmanism. In 354, Roman Emperor Constantius II

Constantius II (; ; 7 August 317 – 3 November 361) was Roman emperor from 337 to 361. His reign saw constant warfare on the borders against the Sasanian Empire and Germanic peoples, while internally the Roman Empire went through repeated civ ...

sent an embassy headed by Theophilos the Indian

Theophilos the Indian, also known as Theophilus Indus () (died 364), also called "the Ethiopian", was an Aetian or Heteroousian bishop who fell alternately in and out of favor with the court of the Roman emperor Constantius II. He is mentioned in ...

to convert the Himyarites to Christianity. According to Philostorgius

Philostorgius (; 368 – c. 439 AD) was an Anomoean Church historian of the 4th and 5th centuries.

Very little information about his life is available. He was born in Borissus, Cappadocia to Eulampia and Carterius, and lived in Constantinopl ...

, the mission was resisted by local Jews. Several inscriptions have been found in Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

and Sabaean praising the ruling house in Jewish terms for ''helping and empowering the People of Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

''.

According to Islamic traditions, King As'ad The Perfect mounted a military expedition to support the Jews of Yathrib

Medina, officially al-Madinah al-Munawwarah (, ), also known as Taybah () and known in pre-Islamic times as Yathrib (), is the capital of Medina Province (Saudi Arabia), Medina Province in the Hejaz region of western Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, ...

. Abu Karib As'ad, as known from the inscriptions, led a military campaign to central Arabia or Najd

Najd is a Historical region, historical region of the Arabian Peninsula that includes most of the central region of Saudi Arabia. It is roughly bounded by the Hejaz region to the west, the Nafud desert in Al-Jawf Province, al-Jawf to the north, ...

to support the vassal Kinda

Kinda or Kindah may refer to:

People

Given name

* Kinda Alloush (born 1982), Syrian actress

* Kinda El-Khatib (born 1996 or 1997), Lebanese activist

Surname

* Chris Kinda (born 1999), Namibian para-athlete

* Gadi Kinda (1994–2025), ...

against the Lakhmids

The Lakhmid kingdom ( ), also referred to as al-Manādhirah () or as Banū Lakhm (), was an Arab kingdom that was founded and ruled by the Lakhmid dynasty from to 602. Spanning Eastern Arabia and Sawad, Southern Mesopotamia, it existed as a d ...

. However, no direct reference to Judaism or Yathrib

Medina, officially al-Madinah al-Munawwarah (, ), also known as Taybah () and known in pre-Islamic times as Yathrib (), is the capital of Medina Province (Saudi Arabia), Medina Province in the Hejaz region of western Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, ...

was discovered from his lengthy reign. Abu Karib As'ad died in 445, having reigned for almost 50 years. By 515, Himyar became increasingly divided along religious lines and a bitter conflict between different factions paved the way for an Aksumite

The Kingdom of Aksum, or the Aksumite Empire, was a kingdom in East Africa and South Arabia from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, based in what is now northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, and spanning present-day Djibouti and Sudan. Emerging ...

intervention. The last Himyarite king Mu'di Karab Ya'fir was supported by Aksum against his Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

rivals. Mu'di Karab was Christian and launched a campaign against the Lakhmids

The Lakhmid kingdom ( ), also referred to as al-Manādhirah () or as Banū Lakhm (), was an Arab kingdom that was founded and ruled by the Lakhmid dynasty from to 602. Spanning Eastern Arabia and Sawad, Southern Mesopotamia, it existed as a d ...

in Southern Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

, with the support of other Arab allies of The Byzantine Empire. The Lakhmids

The Lakhmid kingdom ( ), also referred to as al-Manādhirah () or as Banū Lakhm (), was an Arab kingdom that was founded and ruled by the Lakhmid dynasty from to 602. Spanning Eastern Arabia and Sawad, Southern Mesopotamia, it existed as a d ...

were a Bulwark of Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, which was intolerant to a proselytizing religion like Christianity.

After the death of Ma'adikarib Ya'fur around 521 AD, a Himyarite Jewish warlord

Warlords are individuals who exercise military, Economy, economic, and Politics, political control over a region, often one State collapse, without a strong central or national government, typically through informal control over Militia, local ...

called Dhu Nuwas

Dhū Nuwās (), real name Yūsuf Asʾar Yathʾar ( Musnad: 𐩺𐩥𐩪𐩰 𐩱𐩪𐩱𐩧 𐩺𐩻𐩱𐩧, ''Yws¹f ʾs¹ʾr Yṯʾr''), Yosef Nu'as (), or Yūsuf ibn Sharhabil (), also known as Masruq in Syriac, and Dounaas () in Medieval G ...

rose to power. He began a campaign of violence against Christians under his control. Dhu Nawas executed Byzantine traders, converted the church in Zafar into a synagogue, and killed its priests, among other acts of conquest. He marched toward the port city of Mocha

Mocha may refer to:

Places

* Mokha, a city in Yemen

* Mocha Island, an island in Biobío Region, Chile

* Mocha, Chile, a town in Chile

* Mocha, Ecuador, a city in Ecuador

* Mocha Canton, a government subdivision in Ecuador

* Mocha, a segmen ...

, killing 14,000 and capturing 11,000. Then he settled a camp in Bab-el-Mandeb

The Bab-el-Mandeb (), the Gate of Grief or the Gate of Tears, is a strait between Yemen on the Arabian Peninsula and Djibouti and Eritrea in the Horn of Africa. It connects the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden and by extension the Indian Ocean.

...

to prevent aid flowing from Aksum. At the same time, Yousef sent an army under the command of another Jewish warlord, Sharahil Yaqbul, to Najran

Najran ( '), is a city in southwestern Saudi Arabia. It is the capital of Najran Province. Today, the city of Najran is one of the fastest-growing cities in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. As of the 2022 census, the city population was 381,431, wi ...

. Sharahil had reinforcements from the Bedouins of the Kinda

Kinda or Kindah may refer to:

People

Given name

* Kinda Alloush (born 1982), Syrian actress

* Kinda El-Khatib (born 1996 or 1997), Lebanese activist

Surname

* Chris Kinda (born 1999), Namibian para-athlete

* Gadi Kinda (1994–2025), ...

and Madh'hij

Madhḥij () is a large Qahtanite Arab tribal confederation. It is located in south and central Arabia. This confederation participated in the early Muslim conquests and was a major factor in the conquest of the Persian empire and the Byzantine ...

tribes, eventually wiping out the Christian community in Najran by means of execution and forced conversion

Forced conversion is the adoption of a religion or irreligion under duress. Someone who has been forced to convert to a different religion or irreligion may continue, covertly, to adhere to the beliefs and practices which were originally held, w ...

to Judaism. Blady speculates that he was likely motivated by stories about Byzantine violence against Byzantine Jewish communities in his decision to begin his campaign of state violence against Christians existing within his territory.;

Christian sources portray Dhu Nuwas as a Jewish zealot, while Islamic traditions say that he marched around 20,000 Christians into trenches filled with flaming oil, burning them alive. Himyarite inscriptions attributed to Dhu Nuwas himself show great pride in killing 27,000, enslaving 20,500 Christians in Ẓafār and Najran

Najran ( '), is a city in southwestern Saudi Arabia. It is the capital of Najran Province. Today, the city of Najran is one of the fastest-growing cities in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. As of the 2022 census, the city population was 381,431, wi ...

and killing 570,000 beasts of burden belonging to them as a matter of imperial policy. It is reported that Byzantium Emperor Justin I

Justin I (; ; 450 – 1 August 527), also called Justin the Thracian (; ), was Roman emperor from 518 to 527. Born to a peasant family, he rose through the ranks of the army to become commander of the imperial guard and when Emperor Anastasi ...

sent a letter to the Aksumite King Kaleb, pressuring him to "...attack the abominable Hebrew." A military alliance of Byzantine, Aksumite, and Arab Christians successfully defeated Dhu Nuwas around 525–527 AD and a client Christian king was installed on the Himyarite throne. Esimiphaios was a local Christian lord, mentioned in an inscription celebrating the burning of an ancient Sabaean palace in

Esimiphaios was a local Christian lord, mentioned in an inscription celebrating the burning of an ancient Sabaean palace in Marib

Marib (; Ancient South Arabian script, Old South Arabian: 𐩣𐩧𐩨/𐩣𐩧𐩺𐩨 ''Mryb/Mrb'') is the capital city of Marib Governorate, Yemen. It was the capital of the ancient kingdom of ''Saba’, Sabaʾ'' (), which some scholars beli ...

to build a church on its ruins. Three new churches were built in Najran alone. Many tribes did not recognize Esimiphaios's authority. Esimiphaios was displaced in 531 by a warrior named Abraha

Abraha ( Ge’ez: አብርሃ) (also spelled Abreha, died presumably 570 CE) was an Aksumite military leader who controlled the Kingdom of Himyar (modern-day Yemen) and a large part of Arabia for over 30 years in the 6th century. Originally ...

, who refused to leave Yemen and declared himself an independent king of Himyar

Himyar was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According to class ...

. Emperor Justinian I

Justinian I (, ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was Roman emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign was marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovatio imperii'', or "restoration of the Empire". This ambition was ...

sent an embassy to Yemen. He wanted the officially ''Christian'' Himyar

Himyar was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According to class ...

ites to use their influence on the tribes in inner Arabia to launch military operations against Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

. Justinian I

Justinian I (, ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was Roman emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign was marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovatio imperii'', or "restoration of the Empire". This ambition was ...

bestowed the ''dignity of king'' upon the Arab sheikh

Sheikh ( , , , , ''shuyūkh'' ) is an honorific title in the Arabic language, literally meaning "elder (administrative title), elder". It commonly designates a tribal chief or a Muslim ulama, scholar. Though this title generally refers to me ...

s of Kinda and Ghassan

The Ghassanids, also known as the Jafnids, were an Arab tribe. Originally from South Arabia, they migrated to the Levant in the 3rd century and established what would eventually become a Christian kingdom under the aegis of the Byzantine Empir ...

in central and north Arabia. From early on, Roman and Byzantine policy was to develop close links with the powers of the coast of the Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

. They were successful in converting Aksum

Axum, also spelled Aksum (), is a town in the Tigray Region of Ethiopia with a population of 66,900 residents (as of 2015). It is the site of the historic capital of the Aksumite Empire.

Axum is located in the Central Zone of the Tigray Regi ...

and influencing their culture. The results with regard to Yemen were rather disappointing.

A Kindite prince called ''Yazid bin Kabshat'' rebelled against Abraha

Abraha ( Ge’ez: አብርሃ) (also spelled Abreha, died presumably 570 CE) was an Aksumite military leader who controlled the Kingdom of Himyar (modern-day Yemen) and a large part of Arabia for over 30 years in the 6th century. Originally ...

and his Arab Christian allies. A truce was reached once The Great Dam of Marib had suffered a breach. Abraha

Abraha ( Ge’ez: አብርሃ) (also spelled Abreha, died presumably 570 CE) was an Aksumite military leader who controlled the Kingdom of Himyar (modern-day Yemen) and a large part of Arabia for over 30 years in the 6th century. Originally ...

died around 555–565 AD; no reliable sources regarding his death are available. The Sasanid empire

The Sasanian Empire (), officially Eranshahr ( , "Empire of the Iranians"), was an Iranian empire that was founded and ruled by the House of Sasan from 224 to 651. Enduring for over four centuries, the length of the Sasanian dynasty's reign ...

annexed Aden

Aden () is a port city located in Yemen in the southern part of the Arabian peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Aden, positioned near the eastern approach to the Red Sea. It is situated approximately 170 km (110 mi) east of ...

around 570. Under their rule, most of Yemen enjoyed great autonomy except for Aden

Aden () is a port city located in Yemen in the southern part of the Arabian peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Aden, positioned near the eastern approach to the Red Sea. It is situated approximately 170 km (110 mi) east of ...

and Sana'a

Sanaa, officially the Sanaa Municipality, is the ''de jure'' capital and largest city of Yemen. The city is the capital of the Sanaa Governorate, but is not part of the governorate, as it forms a separate administrative unit. At an elevation ...

. This era marked the collapse of ancient South Arabian civilization, since the greater part of the country was under several independent clans until the arrival of Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

in 630.

Middle Ages

Advent of Islam and the three Dynasties

Prophet Muhammad

In Islam, Muhammad () is venerated as the Seal of the Prophets who transmitted the Quran, eternal word of God () from the Angels in Islam, angel Gabriel () to humans and jinn. Muslims believe that the Quran, the central religious text of Isl ...

sent his cousin Ali

Ali ibn Abi Talib (; ) was the fourth Rashidun caliph who ruled from until his assassination in 661, as well as the first Shia Imam. He was the cousin and son-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Born to Abu Talib ibn Abd al-Muttalib an ...

to Sana'a

Sanaa, officially the Sanaa Municipality, is the ''de jure'' capital and largest city of Yemen. The city is the capital of the Sanaa Governorate, but is not part of the governorate, as it forms a separate administrative unit. At an elevation ...

and its surroundings around 630. At the time, Yemen was the most advanced region in Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

. The Banu Hamdan

Banu Hamdan (; Ancient South Arabian script, Musnad: 𐩠𐩣𐩵𐩬) is an ancient, large, and prominent Arab tribe in northern Yemen.

Origins and location

The Hamdan stemmed from the eponymous progenitor Awsala (nickname Hamdan) whose descent ...

confederation were among the first to accept Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

. Mohammed

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monotheistic teachings of Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, ...

sent Muadh ibn Jabal

Muʿādh ibn Jabal (; 603 – 639) was a (companion) of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Muadh was an of the Banu Khazraj tribe and compiled the Quran with five companions while Muhammad was still alive. He acquired a reputation for knowledge.

Mu ...

as well to Al-Janad in present-day Taiz

Taiz () is a city in southwestern Yemen. It is located in the Yemeni highlands, near the port city of Mocha on the Red Sea, at an elevation of about above sea level. It is the capital of Taiz Governorate. As of 2023, the city has an estimated p ...

, and dispatched letters to various tribal leaders. The reason behind this was the division among the tribes and the absence of a strong central authority in Yemen during the days of the prophet. Major tribes, including Himyar

Himyar was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According to class ...

, sent delegations to Medina

Medina, officially al-Madinah al-Munawwarah (, ), also known as Taybah () and known in pre-Islamic times as Yathrib (), is the capital of Medina Province (Saudi Arabia), Medina Province in the Hejaz region of western Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, ...

during the ''Year of delegations'' around 630–631. Several Yemenis had already accepted Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

, including Ammar ibn Yasir

Ammar ibn Yasir (; July 657 C.E.) was a ''Sahabi'' (Companion) of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, and a commander in the early Muslim conquests. His parents, Sumayya and Yasir ibn Amir, were the first martyrs of the Ummah. Ammar converted to I ...

, Al-Ala'a Al-Hadrami

Al-Ala al-Hadrami (; died 635–636 or 641–642) was an early Muslim commander and the tax collector of Bahrayn (eastern Arabia) under the Islamic prophet Muhammad in and Bahrayn's governor in 632–636 and 637–638 under caliphs Abu Bakr () ...

, Miqdad ibn Aswad

Al-Miqdad ibn Amr al-Bahrani (), better known as al-Miqdad ibn al-Aswad al-Kindi () or simply Miqdad, was one of the Sahabah, companions of the Islamic Muhammad, prophet Muhammad. His Kunya (Arabic), kunya was Abu Ma'bad (). Miqdad was born in ...

, Abu Musa Ashaari

Abu Musa Abd Allah ibn Qays al-Ash'ari (), better known as Abu Musa al-Ash'ari () (died c. 662 or 672) was a companion of Muhammad and an important figure in early Islamic history. He was at various times governor of Basra and Kufa and was involv ...

and Sharhabeel ibn Hasana. A man named 'Abhala ibn Ka'ab Al-Ansi expelled the remaining Persians and claimed to be a prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divinity, divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings ...

of Rahman. He was assassinated by a Yemeni of Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

origin called Fayruz al-Daylami

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Fayrūz al-Daylamī al-Himyarī (, Persian: فیروز دیلمی, ''Firuz the Daylamite'') was a Persian companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

Biography

Fayruz al-Daylami, also spelt Firuz al-Daylami, belonged to the desce ...

. Christians, who were mainly staying in Najran

Najran ( '), is a city in southwestern Saudi Arabia. It is the capital of Najran Province. Today, the city of Najran is one of the fastest-growing cities in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. As of the 2022 census, the city population was 381,431, wi ...

along with Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, agreed to pay Jizya

Jizya (), or jizyah, is a type of taxation levied on non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Sharia, Islamic law. The Quran and hadiths mention jizya without specifying its rate or amount,Sabet, Amr (2006), ''The American Journal of Islamic Soc ...

, although some Jews converted to Islam, such as Wahb ibn Munabbih

Wahb ibn Munabbih () was a Yemenite Muslim traditionist of Dhamar (two days' journey from Sana'a) in Yemen. He was a member of Banu Alahrar (Sons of the free people), a Yemeni of Persian origin.

He is counted among the Tabi‘in and a narrato ...

and Ka'ab al-Ahbar

Kaʿb al-Aḥbār (, full name Abū Isḥāq Kaʿb ibn Maniʿ al-Ḥimyarī () was a 7th-century Yemenite Jew from the Arab tribe of "Dhī Raʿīn" () who converted to Islam. He was considered to be the earliest authority on Israiliyyat and ...

.

The country was stable during the Rashidun Caliphate

The Rashidun Caliphate () is a title given for the reigns of first caliphs (lit. "successors") — Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali collectively — believed to Political aspects of Islam, represent the perfect Islam and governance who led the ...

. Yemeni tribes played a pivotal role in the Islamic conquests of Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

, Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

, the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

, Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, North Africa, Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

and Andalusia

Andalusia ( , ; , ) is the southernmost autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain, located in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, in southwestern Europe. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomou ...

. Yemeni tribes that settled in Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

, contributed significantly to the solidification of Umayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate or Umayyad Empire (, ; ) was the second caliphate established after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. Uthman ibn Affan, the third of the Rashidun caliphs, was also a membe ...

rule, especially during the reign of Marwan I

Marwan ibn al-Hakam ibn Abi al-As ibn Umayya (; 623 or 626April/May 685), commonly known as MarwanI, was the fourth Umayyad Caliphate, Umayyad caliph, ruling for less than a year in 684–685. He founded the Marwanid ruling house of the Umayyad ...

. Powerful Yemenite tribes like Kindah

Kinda or Kindah may refer to:

People

Given name

* Kinda Alloush (born 1982), Syrian actress

* Kinda El-Khatib (born 1996 or 1997), Lebanese activist

Surname

* Chris Kinda (born 1999), Namibian para-athlete

* Gadi Kinda (1994–2025), Isr ...

were on his side during the Battle of Marj Rahit. Several emirates led by people of Yemeni descent were established in North Africa and Andalusia

Andalusia ( , ; , ) is the southernmost autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain, located in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, in southwestern Europe. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomou ...

. Effective control over entire Yemen was not achieved by the Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate or Umayyad Empire (, ; ) was the second caliphate established after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. Uthman ibn Affan, the third of the Rashidun caliphs, was also a member o ...

. Imam

Imam (; , '; : , ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Islam, Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a prayer leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Salah, Islamic prayers, serve as community leaders, ...

Abd Allah ibn Yahya was elected in 745 to lead the Ibāḍī movement in Hadramawt

Hadhramaut ( ; ) is a geographic region in the South Arabia, southern part of the Arabian Peninsula which includes the Yemeni Governorates of Yemen, governorates of Hadhramaut, Shabwah Governorate, Shabwah and Al Mahrah Governorate, Mahrah, D ...

and Oman

Oman, officially the Sultanate of Oman, is a country located on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia and the Middle East. It shares land borders with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. Oman’s coastline ...

. He expelled the Umayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate or Umayyad Empire (, ; ) was the second caliphate established after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. Uthman ibn Affan, the third of the Rashidun caliphs, was also a membe ...

governor from Sana'a

Sanaa, officially the Sanaa Municipality, is the ''de jure'' capital and largest city of Yemen. The city is the capital of the Sanaa Governorate, but is not part of the governorate, as it forms a separate administrative unit. At an elevation ...

and captured Mecca

Mecca, officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, is the capital of Mecca Province in the Hejaz region of western Saudi Arabia; it is the Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow valley above ...

and Medina

Medina, officially al-Madinah al-Munawwarah (, ), also known as Taybah () and known in pre-Islamic times as Yathrib (), is the capital of Medina Province (Saudi Arabia), Medina Province in the Hejaz region of western Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, ...

in 746.Andrew Rippin ''The Islamic World'' p. 237 Routledge, 23 October 2013 Ibn Yahya, known by his nickname ''Talib al-Haqq'' (Seeker of the Truth), established the first Ibadi

Ibadism (, ) is a school of Islam concentrated in Oman established from within the Kharijites. The followers of the Ibadi sect are known as the Ibadis or, as they call themselves, The People of Truth and Integrity ().

Ibadism emerged around 6 ...

state in the history of Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

but was killed in Taif

Taif (, ) is a city and governorate in Mecca Province in Saudi Arabia. Located at an elevation of in the slopes of the Hijaz Mountains, which themselves are part of the Sarat Mountains, the city has a population of 563,282 people in 2022, mak ...

in around 749.

Muhammad ibn Ziyad founded the Ziyadid dynasty

The Ziyadid dynasty () was a Muslim dynasty that ruled western Yemen from 819 until 1018 from the capital city of Zabid. It was the first dynastic regime to wield power over the Yemeni lowland after the introduction of Islam in about 630.

Est ...

in Tihama

Tihamah or Tihama ( ') is the Red Sea coastal plain of the Arabian Peninsula from the Gulf of Aqaba to the Bab el Mandeb.

Etymology

Tihāmat is the Proto-Semitic language's term for 'sea'. Tiamat (or Tehom, in masculine form) was the ancient Mes ...

around 818; the state stretched from Haly (In present-day Saudi Arabia) to Aden

Aden () is a port city located in Yemen in the southern part of the Arabian peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Aden, positioned near the eastern approach to the Red Sea. It is situated approximately 170 km (110 mi) east of ...

. They nominally recognized the Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate or Abbasid Empire (; ) was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib (566–653 CE), from whom the dynasty takes ...

but were in fact ruling independently from their capital in Zabid

Zabid () (also spelled Zabīd, Zabeed and Zebid) is a town with an urban population of around 52,590 people, located on Yemen's western coastal plain. It is one of the oldest towns in Yemen, and has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1993. Ho ...

.Paul Wheatley. (2001). ''The Places Where Men Pray Together: Cities in Islamic Lands, Seventh Through the Tenth Centuries''. p. 128. University of Chicago Press The history of this dynasty is obscure; they never exercised control over the highlands and Hadramawt

Hadhramaut ( ; ) is a geographic region in the South Arabia, southern part of the Arabian Peninsula which includes the Yemeni Governorates of Yemen, governorates of Hadhramaut, Shabwah Governorate, Shabwah and Al Mahrah Governorate, Mahrah, D ...

, and did not control more than a coastal strip of the Yemen (Tihama

Tihamah or Tihama ( ') is the Red Sea coastal plain of the Arabian Peninsula from the Gulf of Aqaba to the Bab el Mandeb.

Etymology

Tihāmat is the Proto-Semitic language's term for 'sea'. Tiamat (or Tehom, in masculine form) was the ancient Mes ...

) bordering the Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

. A Himyar

Himyar was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According to class ...

ite clan called the Yufirids The Yuʿfirids () were an Islamic Himyarite dynasty that held power in the highlands of Yemen from 847 to 997. The name of the family is often incorrectly rendered as "Yafurids". They nominally acknowledged the suzerainty of the Abbasids, Abbasid ca ...

established their rule over the highlands from Saada

Saada (), located in the northwest of Yemen, is the capital and largest city of the governorate bearing the same name, as well as the administrative seat of the eponymous district. The city lies in the Serat (Sarawat) mountains at an altitude o ...

to Taiz

Taiz () is a city in southwestern Yemen. It is located in the Yemeni highlands, near the port city of Mocha on the Red Sea, at an elevation of about above sea level. It is the capital of Taiz Governorate. As of 2023, the city has an estimated p ...

, while Hadramawt

Hadhramaut ( ; ) is a geographic region in the South Arabia, southern part of the Arabian Peninsula which includes the Yemeni Governorates of Yemen, governorates of Hadhramaut, Shabwah Governorate, Shabwah and Al Mahrah Governorate, Mahrah, D ...

was an Ibadi

Ibadism (, ) is a school of Islam concentrated in Oman established from within the Kharijites. The followers of the Ibadi sect are known as the Ibadis or, as they call themselves, The People of Truth and Integrity ().

Ibadism emerged around 6 ...

stronghold and rejected all allegiance to the Abbasids in Baghdad

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

. By virtue of its location, the Ziyadid dynasty

The Ziyadid dynasty () was a Muslim dynasty that ruled western Yemen from 819 until 1018 from the capital city of Zabid. It was the first dynastic regime to wield power over the Yemeni lowland after the introduction of Islam in about 630.

Est ...

of Zabid

Zabid () (also spelled Zabīd, Zabeed and Zebid) is a town with an urban population of around 52,590 people, located on Yemen's western coastal plain. It is one of the oldest towns in Yemen, and has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1993. Ho ...

developed a special relationship with Abyssinia

Abyssinia (; also known as Abyssinie, Abissinia, Habessinien, or Al-Habash) was an ancient region in the Horn of Africa situated in the northern highlands of modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea.Sven Rubenson, The survival of Ethiopian independence, ...

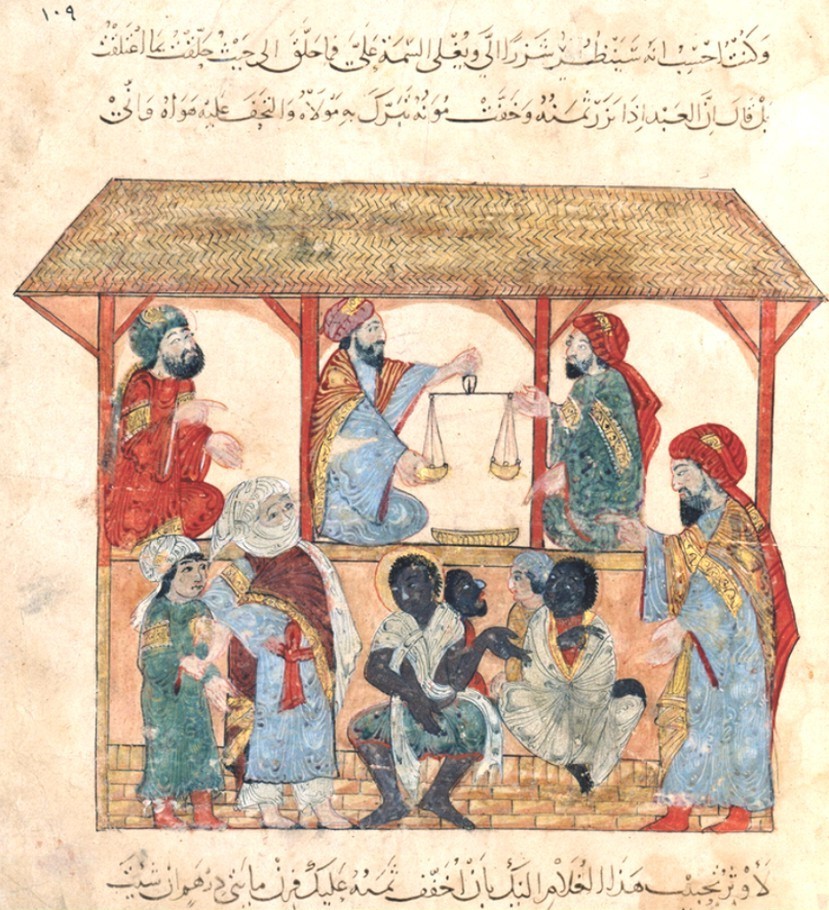

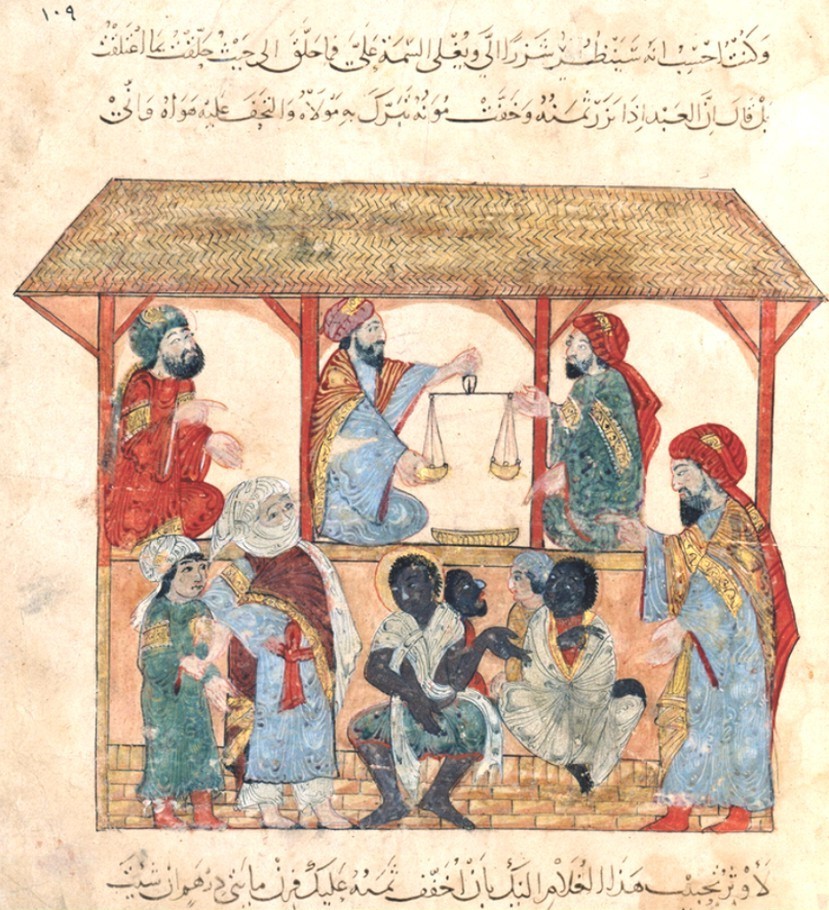

. The chief of the Dahlak islands exported slaves as well as amber and leopard hides to the then ruler of Yemen.

The first Zaidi imam

Imam (; , '; : , ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Islam, Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a prayer leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Salah, Islamic prayers, serve as community leaders, ...

, Yahya ibn al-Husayn Yahya may refer to:

* Yahya (name), a common Arabic male given name

* Yahya (Zaragoza), 11th-century ruler of Zaragoza

* Yahya of Antioch / Yahya ibn Sa'id al-Antaki / Yaḥya ibn Saʿīd al-Anṭākī, 11th century Christian Arabic historian.

* ...

, arrived to Yemen in 893. He was the founder of the Zaidi imamate in 897. He was a religious cleric and judge who was invited to come to Saada

Saada (), located in the northwest of Yemen, is the capital and largest city of the governorate bearing the same name, as well as the administrative seat of the eponymous district. The city lies in the Serat (Sarawat) mountains at an altitude o ...

from Medina

Medina, officially al-Madinah al-Munawwarah (, ), also known as Taybah () and known in pre-Islamic times as Yathrib (), is the capital of Medina Province (Saudi Arabia), Medina Province in the Hejaz region of western Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, ...

to arbitrate tribal disputes. Imam Yahya persuaded local tribesmen to follow his teachings. The sect slowly spread across the highlands, as the tribes of Hashid

The Hashid (; Musnad: 𐩢𐩦𐩵𐩣) is a tribal confederation in Yemen. It is the second or third largest – after Bakil and, depending on sources, Madh'hij

and Bakil

The Bakil (, Musnad: 𐩨𐩫𐩺𐩡) federation is the largest tribal federation in Yemen. The tribe consists of more than 10 million men and women they are the sister tribe of Hashid(4 million) whose leader was Abdullah Bin Hussein Alahmar. The ...

, later known as ''the twin wings of the imamate'', accepted his authority. Yahya established his influence in Saada

Saada (), located in the northwest of Yemen, is the capital and largest city of the governorate bearing the same name, as well as the administrative seat of the eponymous district. The city lies in the Serat (Sarawat) mountains at an altitude o ...

and Najran

Najran ( '), is a city in southwestern Saudi Arabia. It is the capital of Najran Province. Today, the city of Najran is one of the fastest-growing cities in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. As of the 2022 census, the city population was 381,431, wi ...

; he also tried to capture Sana'a

Sanaa, officially the Sanaa Municipality, is the ''de jure'' capital and largest city of Yemen. The city is the capital of the Sanaa Governorate, but is not part of the governorate, as it forms a separate administrative unit. At an elevation ...

from the Yufirids The Yuʿfirids () were an Islamic Himyarite dynasty that held power in the highlands of Yemen from 847 to 997. The name of the family is often incorrectly rendered as "Yafurids". They nominally acknowledged the suzerainty of the Abbasids, Abbasid ca ...

in 901, but he failed miserably. In 904, the newly established Isma'ili

Ismailism () is a branch of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor (Imamate in Nizari doctrine, imām) to Ja'far al-Sadiq, wherein they differ from the ...

followers invaded Sana'a

Sanaa, officially the Sanaa Municipality, is the ''de jure'' capital and largest city of Yemen. The city is the capital of the Sanaa Governorate, but is not part of the governorate, as it forms a separate administrative unit. At an elevation ...

. The Yufirid emir As'ad ibn Ibrahim retreated to Al-Jawf Al-Jawf or Al-Jouf ( ' ) may refer to:

* Al-Jawf Province, region and administrative province of Saudi Arabia

* Al Jawf Governorate, a governorate of Yemen

* Al Jawf, Libya

Al Jawf ( ') is a town in southeastern Libya, the capital of the Kufra D ...

, and between 904 and 913, Sana'a was conquered no less than 20 times by Isma'ilis and Yufirids The Yuʿfirids () were an Islamic Himyarite dynasty that held power in the highlands of Yemen from 847 to 997. The name of the family is often incorrectly rendered as "Yafurids". They nominally acknowledged the suzerainty of the Abbasids, Abbasid ca ...

. As'ad ibn Ibrahim regained Sana'a

Sanaa, officially the Sanaa Municipality, is the ''de jure'' capital and largest city of Yemen. The city is the capital of the Sanaa Governorate, but is not part of the governorate, as it forms a separate administrative unit. At an elevation ...

in 915. The country was in turmoil as Sana'a

Sanaa, officially the Sanaa Municipality, is the ''de jure'' capital and largest city of Yemen. The city is the capital of the Sanaa Governorate, but is not part of the governorate, as it forms a separate administrative unit. At an elevation ...

became a battlefield for the three dynasties as well as independent tribes.

The Yufirid emir Abdullah ibn Qahtan attacked and burned Zabid

Zabid () (also spelled Zabīd, Zabeed and Zebid) is a town with an urban population of around 52,590 people, located on Yemen's western coastal plain. It is one of the oldest towns in Yemen, and has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1993. Ho ...

in 989, severely weakening the Ziyadid dynasty

The Ziyadid dynasty () was a Muslim dynasty that ruled western Yemen from 819 until 1018 from the capital city of Zabid. It was the first dynastic regime to wield power over the Yemeni lowland after the introduction of Islam in about 630.

Est ...

. The Ziyadid monarchs lost effective power after 989, or even earlier than that. Meanwhile, a succession of slaves held power in Zabid