Popish plot on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Popish Plot was a fictitious conspiracy invented by Titus Oates that between 1678 and 1681 gripped the kingdoms of

The Popish Plot was a fictitious conspiracy invented by Titus Oates that between 1678 and 1681 gripped the kingdoms of

Image:Popish Plot Playcard1.jpg, Informer William Bedloe

Image:Popish Plot Playcard2.jpg, Titus Oates uncovers the supposed plot

Image:Popish Plot Playcard3.jpg, Magistrate Edmund Berry Godfrey with Oates

Image:Popish Plot Playcard4.jpg, William Brooks,

1903 Duckworth and Company edition

at

Nathaniel Reading

{{Authority control Anti-Catholicism in the United Kingdom Anti-Catholicism in England Anti-Catholicism in Scotland Anti-Catholicism in Wales Charles II of England Conspiracy theories involving Catholics Impeachment in the United Kingdom Impeachment trials

The Popish Plot was a fictitious conspiracy invented by Titus Oates that between 1678 and 1681 gripped the kingdoms of

The Popish Plot was a fictitious conspiracy invented by Titus Oates that between 1678 and 1681 gripped the kingdoms of England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

and Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

in anti-Catholic hysteria. Oates alleged that there was an extensive Catholic conspiracy to assassinate Charles II, accusations that led to the show trial

A show trial is a public trial in which the guilt (law), guilt or innocence of the defendant has already been determined. The purpose of holding a show trial is to present both accusation and verdict to the public, serving as an example and a d ...

s and executions of at least 22 men and precipitated the Exclusion Bill Crisis. During this tumultuous period, Oates weaved an intricate web of accusations, fueling public fears and paranoia. However, as time went on, the lack of substantial evidence and inconsistencies in Oates's testimony began to unravel the plot. Eventually, Oates himself was arrested and convicted for perjury, exposing the fabricated nature of the conspiracy.

Background

Development of English anti-Catholicism

The fictitious Popish Plot must be understood against the background of theEnglish Reformation

The English Reformation began in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away first from the authority of the pope and bishops Oath_of_Supremacy, over the King and then from some doctrines and practices of the Catholic Church ...

and the subsequent development of a strong anti-Catholic nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

sentiment among the mostly Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

population of England.

The English Reformation

The English Reformation began in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away first from the authority of the pope and bishops Oath_of_Supremacy, over the King and then from some doctrines and practices of the Catholic Church ...

began in 1533, when King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disagreement w ...

(1509–1547) sought an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine,

historical Spanish: , now: ; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England as the Wives of Henry VIII, first wife of King Henry VIII from their marr ...

to marry Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 – 19 May 1536) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the Wives of Henry VIII, second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and execution, by beheading ...

. As the Pope

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

would not grant this, Henry broke away from Rome and took control of the Church in England. Later, he had the monasteries dissolved, causing opposition in the still largely Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

nation. Under Henry's son Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. The only surviving son of Henry VIII by his thi ...

(1547–1553), the Church of England was transformed into a strictly Protestant body, with many remnants of Catholicism suppressed. Edward was succeeded by his half-sister Mary I of England

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain as the wife of King Philip II from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She made vigorous ...

(1553–1558), daughter of Henry VIII and Catherine. She was a Catholic and returned the Church in England to union with the Holy See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

. Mary tainted her policy with two unpopular actions: she married her cousin, King Philip II of Spain

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an Absolute monarchy, absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted Government, governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a Constitutional monarchy, ...

, where the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a Catholic Inquisitorial system#History, judicial procedure where the Ecclesiastical court, ecclesiastical judges could initiate, investigate and try cases in their jurisdiction. Popularly it became the name for various med ...

continued, and had 300 Protestants burned at the stake, causing many Englishmen to associate Catholicism with the involvement of foreign powers and religious persecution.

Mary was succeeded by her Protestant half-sister, Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

(1558–1603), who again broke away from Rome and suppressed Catholicism. Elizabeth and later Protestant monarchs caused to be hanged and mutilated hundreds of Catholic priests and laymen. This, and her dubious legitimacy – she was the daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn – led to Catholic powers not recognising her as queen and favouring her next relative, the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

. Elizabeth's reign saw Catholic rebellions like the Rising of the North (1569) as well as intrigues like the Ridolfi Plot (1571) and the Babington Plot

The Babington Plot was a plan in 1586 to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I, a Protestantism, Protestant, and put Mary, Queen of Scots, her Catholic Church, Catholic cousin, on the English throne. It led to Mary's execution, a result of a letter s ...

(1586), both intending to kill Elizabeth and replace her with Mary under a Spanish invasion. Three popes issued bulls judging Elizabeth, giving grounds to suspect English Catholics' loyalty. Following the Babington Plot, Mary was beheaded in 1587. This – and Elizabeth's support of the Dutch Revolt

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt (; 1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Reformation, centralisation, exc ...

in the Spanish Netherlands

The Spanish Netherlands (; ; ; ) (historically in Spanish: , the name "Flanders" was used as a '' pars pro toto'') was the Habsburg Netherlands ruled by the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs from 1556 to 1714. They were a collection of States of t ...

– triggered Philip II of Spain's attempted invasion with the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (often known as Invincible Armada, or the Enterprise of England, ) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by Alonso de Guzmán, Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aristocrat without previous naval ...

(1588). This reinforced English resentment of Catholics, while the Armada's failure convinced many Englishmen that God was on the Protestant side.

Anti-Catholic sentiment reached new heights in 1605 after the failed Gunpowder Plot

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in earlier centuries often called the Gunpowder Treason Plot or the Jesuit Treason, was an unsuccessful attempted regicide against James VI and I, King James VI of Scotland and I of England by a group of English ...

. Catholic conspirators attempted to topple the Protestant reign of King James I by exploding a bomb during the King's opening of parliament. The plot was thwarted when Guy Fawkes, who was in charge of the explosives, was discovered the night before. The magnitude of the plot, meant to kill the leading government figures in one stroke, convinced many Englishmen that Catholics were murderous conspirators who would stop at nothing to have their way, laying the groundwork for future allegations.

Anti-Catholicism in the 17th century

Anti-Catholic sentiment was a constant factor in how England perceived the events of the following decades: theThirty Years War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine, or disease, whil ...

(1618–1648) was seen as an attempt by the Catholic Habsburgs to exterminate German Protestantism. Under the early Stuart Kings, fears of Catholic conspiracies were rampant and the policies of Charles I – especially his church policies, which had a decidedly high church

A ''high church'' is a Christian Church whose beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, Christian liturgy, liturgy, and Christian theology, theology emphasize "ritual, priestly authority, ndsacraments," and a standard liturgy. Although ...

bent – were seen as pro-Catholic and likely induced by a Catholic conspiracy headed by Charles' Catholic queen, Henrietta Maria of France

Henrietta Maria of France ( French: ''Henriette Marie''; 25 November 1609 – 10 September 1669) was Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland from her marriage to King Charles I on 13 June 1625 until his execution on 30 January 1649. She was ...

. This, together with accounts of Catholic atrocities in Ireland in 1641, helped trigger the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

(1642–1649), which led to the abolition of the monarchy and a decade of Puritan rule tolerating most forms of Protestantism, but not Catholicism. The restoration of the monarchy in 1660 under King Charles II brought a reaction against all religious dissenters outside the established Church of England. Catholics still suffered under popular hostility and legal discrimination.

Anti-Catholic hysteria flared up lightly during the reign of Charles II, which saw disasters such as the Great Plague of London (1665) and the Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Wednesday 5 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old London Wall, Roman city wall, while also extendi ...

(1666). Vague rumours blamed the fire on arson by Catholics and especially Jesuits

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

. Kenyon remarks, "At Coventry

Coventry ( or rarely ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands (county), West Midlands county, in England, on the River Sherbourne. Coventry had been a large settlement for centurie ...

, the townspeople were possessed by the idea that the papists were about to rise and cut their throats ... A nationwide panic seemed likely, and as homeless refugees poured out from London into the countryside, they took with them stories of a kind which were to be familiar enough in 1678 and 1679."

Anti-Catholicism was fueled by doubts about the religious allegiance of the King, who had been supported by the Catholic powers during his exile, and had married a Portuguese Catholic princess, Catherine of Braganza

Catherine of Braganza (; 25 November 1638 – 31 December 1705) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England, List of Scottish royal consorts, Scotland and Ireland during her marriage to Charles II of England, King Charles II, which la ...

. Charles formed an alliance with the leading Catholic power France against the Protestant Netherlands. Furthermore, Charles' brother and heir presumptive, James, Duke of York

James II and VII (14 October 1633 – 16 September 1701) was King of England and Monarchy of Ireland, Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II of England, Charles II, on 6 February 1 ...

, had embraced Catholicism, although his brother forbade him to make any public avowal. In 1672, Charles issued the Royal Declaration of Indulgence, in which he suspended all penal laws against Catholics and other religious dissenters. This fueled Protestant fears of increasing Catholic influence in England, and led to conflict with parliament during the 1670s. In December 1677 an anonymous pamphlet (possibly by Andrew Marvell) spread alarm in London by accusing the Pope of plotting to overthrow the lawful government of England.

Events

Beginnings

The fictitious Popish Plot unfolded in a very peculiar fashion. Oates and Israel Tonge, a fanatically anti-Catholic clergyman (who was widely believed to be insane), had written a large manuscript that accused theCatholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

authorities of approving the assassination of Charles II. The Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

s in England were to carry out the task. The manuscript also named nearly 100 Jesuits and their supporters who were supposedly involved in this assassination plot; nothing in the document was ever proven to be true.

Oates slipped a copy of the manuscript into the wainscot of a gallery in the house of the physician

A physician, medical practitioner (British English), medical doctor, or simply doctor is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through the Medical education, study, Med ...

Sir Richard Barker, with whom Tonge was living. The following day Tonge claimed to find the manuscript and showed it to an acquaintance, Christopher Kirkby, who was shocked and decided to inform the King. Kirkby was a chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a graduated scientist trained in the study of chemistry, or an officially enrolled student in the field. Chemists study the composition of ...

and a former assistant in Charles' scientific experiments, and Charles prided himself on being approachable to the general public. On 13 August 1678, whilst Charles was out walking in St. James's Park, the chemist informed him of the plot. Charles was dismissive but Kirkby stated that he knew the names of assassins who planned to shoot the King and, if that failed, the Queen's physician, Sir George Wakeman, would poison him. When the King demanded proof, the chemist offered to bring Tonge who knew of these matters personally. The King did agree to see both Kirkby and Tonge that evening, when he gave them a short audience. At this stage, he was already sceptical, but he was apparently not ready to rule out the possibility that there might be a plot of some sort (otherwise, Kenyon argues, he would not have given these two very obscure men a private audience). Charles told Kirkby to present Tonge to Thomas Osborne, Lord Danby, Lord High Treasurer, then the most influential of the King's ministers. Tonge then lied to Danby, saying that he had found the manuscript but did not know the author.

Investigations

As Kenyon points out, the government took seriously even the remotest hint of a threat to the King's life or well-being – in the previous spring a Newcastle housewife had been investigated by the Secretary of State simply for saying that "the King gets the curse of many good and faithful wives such as myself for his bad example". Danby, who seems to have believed in the Plot, advised the King to order an investigation. Charles II denied the request, maintaining that the entire affair was absurd. He told Danby to keep the events secret so as not to put the idea of regicide into people's minds. However, word of the manuscript spread to the Duke of York, who publicly called for an investigation into the matter. Even Charles admitted that given the sheer number of allegations, he could not say positively that none of them was true, and reluctantly agreed. During the investigation, Oates' name arose. From the first, the King was convinced that Oates was a liar, and Oates did not help his case by claiming to have met the regent ofSpain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, Don John of Austria. Questioned by the King, who had met Don John in Brussels

Brussels, officially the Brussels-Capital Region, (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) is a Communities, regions and language areas of Belgium#Regions, region of Belgium comprising #Municipalit ...

in 1656, it became obvious that Oates had no idea what he looked like. The King had a long and frank talk with Paul Barillon, the French ambassador, in which he made it clear that he did not believe that there was a word of truth in the plot, and that Oates was "a wicked man"; but that by now he had come round to the view that there must be an investigation, particularly with Parliament about to reassemble.

On 6 September Oates was summoned before the magistrate Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey to swear an oath prior to his testimony before the King. Oates claimed he had been at a Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

meeting held at the White Horse Tavern in the Strand, London, on April 24, 1678. According to Oates, the purpose of that meeting was to discuss the assassination of Charles II. The meeting discussed a variety of methods which included: stabbing by Irish ruffians, shooting by two Jesuit soldiers, or poisoning by the Queen's physician, Sir George Wakeman.

Oates and Tonge were brought before the Privy Council later that month, and the Council interrogated Oates for several hours; Tonge, who was generally believed to be mad, was simply laughed at, but Oates made a much better impression on the council. On 28 September Oates made 43 allegations against various members of Catholic religious order

A religious order is a subgroup within a larger confessional community with a distinctive high-religiosity lifestyle and clear membership. Religious orders often trace their lineage from revered teachers, venerate their Organizational founder, ...

s – including 541 Jesuits – and numerous Catholic nobles. He accused Sir George Wakeman and Edward Colman, the secretary to Mary of Modena Duchess of York, of planning the assassination. Colman was found to have corresponded with the French Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

Fr Ferrier, confessor to Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

, outlining his grandiose schemes for obtaining a dissolution of the present Parliament, in the hope of its replacement by a new and pro-French Parliament; in the wake of this revelation he was condemned to death for treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

. Wakeman was later acquitted. Despite Oates' unsavoury reputation, the councillors were impressed by his confidence, his grasp of detail and his remarkable memory. A turning point came when he was shown five letters, supposedly written by well-known priests and giving details of the plot, which he was suspected of forging: Oates "at a single glance" named each of the alleged authors. At this the council were "amazed" and began to give much greater credence to the plot; apparently it did not occur to them that Oates' ability to recognise the letters made it ''more'' likely, rather than less, that he had forged them.

Others Oates accused included Dr. William Fogarty, Archbishop Peter Talbot of Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

, Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys ( ; 23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English writer and Tories (British political party), Tory politician. He served as an official in the Navy Board and Member of Parliament (England), Member of Parliament, but is most r ...

and John Belasyse, 1st Baron Belasyse. The list grew to 81 accusations. Oates was given a squad of soldiers and he began to round up Jesuits.

Godfrey's murder

The allegations gained little credence until the murder of Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey, a magistrate and strong supporter of Protestantism, to whom Oates had made his first depositions. His disappearance on 12 October 1678, the finding of his mutilated body on 17 October, and the subsequent failure to solve his murder sent the Protestant population into an uproar. He had been strangled and run through with his own sword. Many of his supporters blamed the murder on Catholics. As Kenyon commented, "Next day, the 18th, James wrote to William of Orange that Godfrey's death was already 'laid against the Catholics', and even he, never the most realistic of men, feared that 'all these things happening together will cause a great flame in the Parliament'." The Lords asked King Charles to banish all Catholics from a radius of around London, which Charles granted on 30 October 1678, but it was too late because London was already in a panic, which was long remembered as "Godfrey's autumn". Oates seized on Godfrey's murder as proof that the plot was true. The murder of Godfrey and the discovery of Edward Coleman's letters provided a solid basis of facts for the lies of Oates and the other informers who followed him. Oates was called to testify before the House of Lords and theHouse of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

on 23 October 1678. He testified that he had seen a number of contracts signed by the Superior General of the Jesuits. The contracts appointed officers that would command an army of Catholic supporters to kill Charles II and establish a Catholic monarch. To this day, no one is certain who killed Sir Edmund Godfrey, and most historians regard the mystery as insoluble. Oates' associate William Bedloe denounced the silversmith Miles Prance, who in turn named three working men, Berry, Green and Hill, who were tried, convicted and executed in February 1679; but it rapidly became clear that they were completely innocent, and that Prance, who had been subjected to torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons including corporal punishment, punishment, forced confession, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimid ...

, named them simply to gain his freedom (Kenyon suggests that he may have chosen men against whom he had a personal grudge, or he may simply have chosen them because they were the first Catholic acquaintances of his who came to mind).

The Plot before Parliament

King Charles, aware of the unrest, returned to London and summonedParliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

. He remained unconvinced by Oates' accusations, but Parliament and public opinion forced him to order an investigation. Parliament truly believed that this plot was real, declaring, "This House is of opinion that there hath been and still is a damnable and hellish plot contrived and carried out by the popish recusants for assigning and murdering the King." Tonge was called to testify on 25 October 1678 where he gave evidence on the Great Fire and, later, rumours of another similar plot. On 1 November, both Houses ordered an investigation in which a Frenchman, Choqueux, was discovered to be storing gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

in a house nearby. This caused a panic, until it was discovered that he was simply the King's firework maker.

Trial of the Five Catholic Lords

Oates became more daring and accused five Catholic lords ( William Herbert, 1st Marquess of Powis, William Howard, 1st Viscount Stafford, Henry Arundell, 3rd Baron Arundell of Wardour, William Petre, 4th Baron Petre and John Belasyse, 1st Baron Belasyse) of involvement in the plot. The King dismissed the accusations as absurd, pointing out that Belasyse was so afflicted withgout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of pain in a red, tender, hot, and Joint effusion, swollen joint, caused by the deposition of needle-like crystals of uric acid known as monosodium urate crysta ...

that he could hardly stand, while Arundell and Stafford, who had not been on speaking terms for 25 years, were most unlikely to be intriguing together; but Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury had the lords arrested and sent to the Tower on 25 October 1678. Seizing upon the anti-Catholic tide, Shaftesbury publicly demanded that the King's brother, James, be excluded from the royal succession, prompting the Exclusion crisis. On 5 November 1678, people burned effigies of the Pope

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

instead of those of Guy Fawkes. At the end of the year, the parliament passed a bill, a second Test Act, excluding Catholics from membership of both Houses (a law not repealed until 1829).

On 1 November 1678, the House of Commons resolved to proceed by impeachment against "the five popish lords". On 23 November all Arundell's papers were seized and examined by the Lords' committee; on 3 December the five peers were arraigned for high treason; and on 5 December the Commons announced the impeachment of Arundell. A month later Parliament was dissolved, and the proceedings were interrupted. In March 1679, it was resolved by both houses that the dissolution had not invalidated the motions for the impeachment. On 10 April 1679 Arundell and three of his companions (Belasyse was too ill to attend) were brought to the House of Lords to put in pleas against the articles of impeachment. Arundell complained of the uncertainty of the charges, and implored the peers to have them "reduced to competent certainty" but on 24 April this plea was voted irregular, and on 26 April the prisoners were again brought to the House of Lords and ordered to amend their pleas. Arundell replied by briefly declaring himself not guilty.

The impeachment trial was fixed for 13 May, but a quarrel between the two houses as to points of procedure, and the legality of admitting the bishops as judges in a capital trial, followed by a dissolution, delayed its commencement until 30 November 1680. On that day it was decided to proceed first against Lord Stafford, who was condemned to death on 7 December and beheaded on 29 December. His trial, compared to the other Plot trials, was reasonably fair, but as in all cases of alleged treason at that date the absence of defence counsel was a fatal handicap (this was finally remedied in 1695), and while Oates' credit had been seriously damaged, the evidence of the principal prosecution witnesses, Turberville and Dugdale, struck even fair-minded observers like John Evelyn as being credible enough. Stafford, denied the services of counsel, failed to exploit several inconsistencies in Tuberville's testimony, which a good lawyer might have turned to his client's advantage.

On 30 December, the evidence against Arundell and his three fellow prisoners was ordered to be in readiness, but their public proceedings stopped. In fact, the death of William Bedloe left the prosecution in serious difficulties, since one protection for a person accused of treason, that there must be two eyewitnesses to an overt act of treason, was observed scrupulously, and only Oates claimed to have any hard evidence against the remaining Lords. Lord Petre died in the Tower in 1683. His companions remained there until 12 February 1684 when an appeal to the Court of King's Bench

The Court of King's Bench, formally known as The Court of the King Before the King Himself, was a court of common law in the English legal system. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century from the '' curia regis'', the King's Bench initi ...

to release them on bail was successful. On 21 May 1685 Arundell, Powis, and Belasyse came to the House of Lords to present petitions for the annulling of the charges and on the following day the petitions were granted. On 1 June 1685, their liberty was formally assured on the ground that the witnesses against them had perjured themselves, and on 4 June the bill of attainder

A bill of attainder (also known as an act of attainder, writ of attainder, or bill of pains and penalties) is an act of a legislature declaring a person, or a group of people, guilty of some crime, and providing for a punishment, often without a ...

against Stafford was reversed.

Height of the hysteria

On 24 November 1678, Oates claimed the Queen was working with the King's physician to poison him and enlisted the aid of "Captain" William Bedloe, a notorious member of the London underworld. The King personally interrogated Oates, caught him out in a number of inaccuracies and lies, and ordered his arrest. However, a few days later, with the threat of constitutional crisis, Parliament forced the release of Oates. Hysteria continued: Roger North wrote that it was as though "the very Cabinet of Hell has been opened". Noblewomen carried firearms if they had to venture outdoors at night. Houses were searched for hidden guns, mostly without any significant result. Some Catholic widows tried to ensure their safety by marryingAnglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

widowers. The House of Commons was searched – without result – in the expectation of a second Gunpowder Plot

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in earlier centuries often called the Gunpowder Treason Plot or the Jesuit Treason, was an unsuccessful attempted regicide against James VI and I, King James VI of Scotland and I of England by a group of English ...

.

Anyone even suspected of being Catholic was driven out of London and forbidden to be within of the city. William Staley, a young Catholic banker, made a drunken threat against the King; within 10 days he was tried, convicted of plotting treason and executed. In calmer times, Staley's offence would probably have resulted in him being bound over, a mild punishment. Oates, for his part, received a state apartment in Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London, England. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It ...

and an annual allowance. He soon presented new allegations, claiming assassins intended to shoot the King with silver bullets so the wound would not heal. The public invented their own stories, including a tale that the sound of digging had been heard near the House of Commons and rumours of a French invasion on the Isle of Purbeck

The Isle of Purbeck is a peninsula in Dorset, England. It is bordered by water on three sides: the English Channel to the south and east, where steep cliffs fall to the sea; and by the marshy lands of the River Frome, Dorset, River Frome and Poo ...

. The evidence of Oates and Bedloe was supplemented by other informers; some like Thomas Dangerfield, were notorious criminals, but others like Stephen Dugdale, Robert Jenison and Edward Turberville were men of good social standing who from motives of greed or revenge denounced innocent victims, and by their apparently plausible evidence made the Plot seem more credible. Dugdale in particular made such a good initial impression that even the King for the first time "began to think that there might be somewhat in the Plot".

Waning of the hysteria

However, public opinion began to turn against Oates. As Kenyon points out, the steady protestations of innocence by all of those who were executed eventually took hold in the public mind. Outside London, the priests who died were almost all venerable and popular members of the community, and there was widespread public horror at their executions. Even Lord Shaftesbury came to regret the executions and is said to have quietly ordered the release of particular priests, whose families he knew. Accusations of plotting inYorkshire

Yorkshire ( ) is an area of Northern England which was History of Yorkshire, historically a county. Despite no longer being used for administration, Yorkshire retains a strong regional identity. The county was named after its county town, the ...

(the "Barnbow Plot"), where prominent local Catholics like Sir Thomas Gascoigne, 2nd Baronet were accused of signing "the Bloody Oath of Secrecy", were unsuccessful because their Protestant neighbours (who sat on the juries) refused to convict them. A grand jury at Westminster rejected the plotting charge against Sir John Fitzgerald, 2nd Baronet in 1681. Judges gradually began to take a more impartial line, ruling that it was not treason for a Catholic to advocate the conversion of England to the old faith, nor to give financial support to religious houses (the latter was a criminal offence, just not treason). The supposed plot gained some credence in Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

, where the two Catholic Archbishops, Plunkett and Talbot, were the principal victims, but not in Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

.

Having had at least twenty-two innocent men executed (the last being Oliver Plunkett, the Catholic Archbishop of Armagh on 1 July 1681), Chief Justice William Scroggs began to declare people innocent and the King began to devise countermeasures. The King, who was notably tolerant of religious differences and generally inclined to clemency, was embittered at the number of innocent men he had been forced to condemn; possibly thinking of the Indemnity and Oblivion Act 1660 ( 12 Cha. 2. c. 11), under which he had pardoned many of his former opponents in 1660, he remarked that his people had never previously had cause to complain of his mercy. At the trial of Sir George Wakeman, and several priests who were tried with him, Scroggs virtually ordered the jury to acquit all of them, and despite public uproar, the King made it clear that he approved of Scroggs' conduct. On 31 August 1681, Oates was told to leave his apartments in Whitehall, but remained undeterred and even denounced the King and the Duke of York. He was arrested for sedition

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech or organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, establ ...

, sentenced to a fine of £100,000 and thrown into prison.

When James II acceded to the throne in 1685 he had Oates tried on two charges of perjury. The Bench which tried him was presided over by the formidable George Jeffreys, 1st Baron Jeffreys, who conducted the trial in such a manner that Oates had no hope of acquittal, and the jury brought in the expected guilty verdict. The death penalty was not available for perjury and Oates was sentenced to be stripped of clerical dress, whipped through London twice, and imprisoned for life and pilloried every year (the penalties were so severe that it has been argued that Jeffreys was trying to kill Oates by ill-treatment). Oates spent the next three years in prison. At the accession of William of Orange and Mary in 1689, he was pardoned and granted a pension of £260 a year, but his reputation did not recover. The pension was suspended, but in 1698 was restored and increased to £300 a year. Oates died on 12 or 13 July 1705, quite forgotten by the public which had once called him a hero.

Of the other informers, James II was content merely to fine Miles Prance for his perjury, on the grounds that he was a Catholic and had been coerced by threats of torture into informing. Thomas Dangerfield was subjected to the same savage penalties as Oates; on returning from his first session in the pillory

The pillory is a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, used during the medieval and renaissance periods for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse. ...

, Dangerfield died of an eye injury after a scuffle with the barrister Robert Francis, who was hanged for his murder. Bedloe, Turbervile and Dugdale had all died of natural causes while the Plot was still officially regarded as true.

Long-term effects

TheSociety of Jesus

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rome. It was founded in 1540 ...

suffered the most between 1678 and 1681. During this period, nine Jesuits

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

were executed and twelve died in prison. Three other deaths were attributable to the hysteria. They also lost Combe in Herefordshire

Herefordshire ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England, bordered by Shropshire to the north, Worcestershire to the east, Gloucestershire to the south-east, and the Welsh ...

, which was the Jesuit headquarters for south Wales. A quote from French Jesuit Claude de la Colombière highlights the plight of the Jesuits during this time period. He comments, "The name of the Jesuit is hated above all else, even by priests both secular and regular, and by the Catholic laity as well, because it is said that the Jesuits have caused this raging storm, which is likely to overthrow the whole Catholic religion".

Other Catholic religious orders

A religious order is a subgroup within a larger confessional community with a distinctive high-religiosity lifestyle and clear membership. Religious orders often trace their lineage from revered teachers, venerate their founders, and have a d ...

such as the Carmelites, Franciscans

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor being the largest conte ...

, and the Benedictines

The Benedictines, officially the Order of Saint Benedict (, abbreviated as O.S.B. or OSB), are a mainly Christian mysticism, contemplative Christian monasticism, monastic Religious order (Catholic), order of the Catholic Church for men and f ...

were also affected by the hysteria. They were no longer permitted to have more than a certain number of members or missions within England. John Kenyon points out that European religious orders throughout the Continent were affected since many of them depended on the alms of the English Catholic community for their existence. Many Catholic priests

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particular, ...

were arrested and tried because the Privy Council wanted to make sure to catch all of those who might possess information about the supposed plot.

The hysteria had serious consequences for ordinary British Catholics as well as priests. On 30 October 1678, a proclamation was made that required all Catholics who were not tradesmen or property owners to leave London and Westminster. They were not to enter a twelve-mile (c.19 km) radius of the city without special permission. Throughout this period Catholics were subject to fines, harassment and imprisonment. It was not until the early 19th century that most of the anti-Catholic legislation was removed by the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829; anti-Catholic sentiment remained even longer among politicians and the general populace, although the Gordon Riots of 1780 made it clear to sensible observers that Catholics were far more likely to be the victims of violence than its perpetrators.

Gallery of playing cards

Alderman

An alderman is a member of a Municipal government, municipal assembly or council in many jurisdictions founded upon English law with similar officials existing in the Netherlands (wethouder) and Belgium (schepen). The term may be titular, denotin ...

of Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

Image:Popish Plot Playcard5.jpg, Thomas Pickering, Benedictine monk

Image:Popish Plot Playcard6.jpg, Nathaniel Reading in Pillory

The pillory is a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, used during the medieval and renaissance periods for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse. ...

Image:Popish Plot Playcard7.jpg, Edward Colman

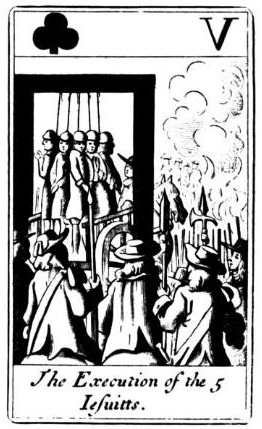

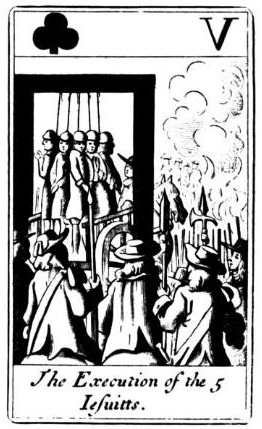

Image:Popish Plot Playcard8.jpg, The execution of the five Jesuits

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

See also

* A Ballad upon the Popish Plot * " A True Narrative of the Horrid Hellish Popish Plot" * Anti-Catholicism * Crypto-papismReferences

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * Reprinted by Phoenix Press, 2000, * * * * * Th1903 Duckworth and Company edition

at

Google Books

Google Books (previously known as Google Book Search, Google Print, and by its code-name Project Ocean) is a service from Google that searches the full text of books and magazines that Google has scanned, converted to text using optical charac ...

.

*

*

External links

Nathaniel Reading

{{Authority control Anti-Catholicism in the United Kingdom Anti-Catholicism in England Anti-Catholicism in Scotland Anti-Catholicism in Wales Charles II of England Conspiracy theories involving Catholics Impeachment in the United Kingdom Impeachment trials