Pollack Joke on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Polonophobia, also referred to as anti-Polonism, ( pl, Antypolonizm), and anti-Polish sentiment are terms for negative attitudes, prejudices, and actions against

Polonophobia, also referred to as anti-Polonism, ( pl, Antypolonizm), and anti-Polish sentiment are terms for negative attitudes, prejudices, and actions against

"THE CRYSTALLIZATION OF ETHNIC IDENTITY IN THE PROCESS OF MASS ETHNOPHOBIAS IN THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE. (The Second Half of the 19th Century)."

The CRN E-bookMatthew F. Jacobson,

Special Sorrows: The Diasporic Imagination of Irish, Polish, and Jewish ...

' Page 34, Social Science, Publisher: University of California Press, 2002; 340 pages. Historic actions inspired by anti-Polonism ranged from felonious acts motivated by hatred, to physical extermination of the Polish nation, the goal of which was to eradicate the Polish state. During World War II, when most of Polish society became the object of genocidal policies of Nazi Germany, anti-Polonism led to an unprecedented campaign of mass murder in German-occupied Poland. In the modern day, among those who often express their hostile attitude towards the Polish people are some

Anti-Polish rhetoric combined with the condemnation of Polish culture was most prominent in the 18th-century

Anti-Polish rhetoric combined with the condemnation of Polish culture was most prominent in the 18th-century  When Poland lost the last vestiges of its independence in 1795 and remained partitioned for 123 years, ethnic Poles were subjected to discrimination in two areas: the Germanisation under Prussian and later German rule, and

When Poland lost the last vestiges of its independence in 1795 and remained partitioned for 123 years, ethnic Poles were subjected to discrimination in two areas: the Germanisation under Prussian and later German rule, and

After Poland regained its independence as the Second Republic at the end of World War I, the question of new Polish borders could not have been easily settled against the will of her former long-term occupiers. Poles continued to be persecuted in the disputed territories, especially in

After Poland regained its independence as the Second Republic at the end of World War I, the question of new Polish borders could not have been easily settled against the will of her former long-term occupiers. Poles continued to be persecuted in the disputed territories, especially in  In the politics of inter-war Germany, anti-Polish feelings ran high.Gerhard L. Weinberg

In the politics of inter-war Germany, anti-Polish feelings ran high.Gerhard L. Weinberg

''Germany, Hitler, and World War II: essays in modern German and world history''

Cambridge University Press, 1995, page 42. The American historian Gerhard Weinberg observed that for many Germans in the Weimar Republic, "Poland was an abomination", Poles were "an East European species of cockroach", Poland was usually described as a ''Saisonstaat'' (a state for a season), and Germans used the phrase "Polish economy" (''polnische Wirtschaft'') for a situation of hopeless muddle. Weinberg noted that in the 1920s–30s, leading German politicians refused to accept Poland as a legitimate nation, and hoped instead to partition Poland, probably with the help of the Soviet Union. The British historian

Nazi propagandists stereotyped Poles as nationalists in order to portray Germans as victims and justify the

Nazi propagandists stereotyped Poles as nationalists in order to portray Germans as victims and justify the

Under

Under

JAKA „GAZETA”, TAKIE PRZEPROSINY...

, PolskieJutro, Number 243 January 2007/ref> alleging (as hearsay) that about 40 Jews were killed by a group of Polish insurgents during the 1944 Uprising. Unlike the book (later reprinted with factual corrections), the actual review by Cichy elicited protests, while selected fragments of his article were confirmed by three Polish historians. Prof.

''Sharing the Dream: White Males in Multicultural America''

Published 2004 by Continuum International Publishing Group, 448 pages. . Page 99. Since the late 1960s, Polish American organizations have made continuous effort to challenge the negative stereotyping of the Polish people once prevalent in American media. The Polish American Guardian Society has argued that NBC-TV used the tremendous power of TV to introduce and push subhuman intelligence jokes about Poles (that were worse than prior simple anti-immigrant jokes) using the repetitive big lie technique to degrade Poles. The play called “Polish Joke” by David Ives has resulted in a number of complaints by the Polonia in the US. The "Polish jokes" heard in the 1970s were particularly offensive, so much so that the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs approached the U.S. State Department about that, however unsuccessfully. The syndrome receded only after Cardinal

BBC News, 4 June 2008. Kawczynski voiced his criticism of the BBC in the House of Commons for "using the Polish community as a cat's paw to try to tackle the thorny issue of mass, unchecked immigration" only because against Poles "it's politically correct to do so." In 2009, the

Putin 'must end attacks on Poles' (Polish president calls on Putin to stop attacks on Poles in Moscow)

BBC News UK. Quote: '' "In my capacity as president of the Polish Republic – Kwaśniewski said in an official statement – I address, to the President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin, an appeal calling on the Russian authorities to undertake energetic action to identify and punish the organizers and perpetrators of the assaults."'' Retrieved 2 February 2013. An employee with the Polish embassy in Moscow was hospitalised in serious condition after being assaulted in broad daylight near the embassy by unidentified men. Three days later, another Polish diplomat was beaten up near the embassy. The following day the Moscow correspondent for the Polish daily ''Rzeczpospolita (newspaper), Rzeczpospolita'' was attacked and beaten up by a group of Russians. It is widely believed that the attacks were organized as revenge for the mugging of four Russian youth in a public park in Warsaw by a group of skinheads, several days earlier.

Polonophobia, also referred to as anti-Polonism, ( pl, Antypolonizm), and anti-Polish sentiment are terms for negative attitudes, prejudices, and actions against

Polonophobia, also referred to as anti-Polonism, ( pl, Antypolonizm), and anti-Polish sentiment are terms for negative attitudes, prejudices, and actions against Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in Ce ...

as an ethnic group, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

as their country, and their culture. These include ethnic prejudice

Ethnic hatred, inter-ethnic hatred, racial hatred, or ethnic tension refers to notions and acts of prejudice and hostility towards an ethnic group in varying degrees.

There are multiple origins for ethnic hatred and the resulting ethnic conflic ...

against Poles and persons of Polish descent, other forms of discrimination

Discrimination is the act of making unjustified distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong or are perceived to belong. People may be discriminated on the basis of race, gender, age, relig ...

, and mistreatment of Poles and the Polish diaspora.

This prejudice led to mass killings and genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Latin ...

or it was used to justify atrocities both before and during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, most notably by the German Nazis and Ukrainian nationalists

Ukrainian nationalism refers to the promotion of the unity of Ukrainians as a people and it also refers to the promotion of the identity of Ukraine as a nation state. The nation building that arose as nationalism grew following the French Revol ...

. While Soviet repressions and massacres of Polish citizens were ideologically motivated, the negative attitude of Soviet authorities to the Polish nation is well-attested.

Nazi Germany killed between 1.8 to 2.7 million ethnic Poles, 140,000 Poles were deported to Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

where at least half of them perished.

Anti-Polish sentiment includes stereotyping Poles as unintelligent and aggressive, as thugs, thieves, alcoholics, and anti-Semites.

Etymology

According to Adam Leszczynski, the term ''antypolonizm'' was coined by journalistEdmund Osmańczyk

Edmund Jan Osmańczyk (August 10, 1913, Deutsch Jägel, Lower Silesia, German Empire – October 4, 1989, Warsaw, People's Republic of Poland), was a Polish writer, author of ''Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements''.

...

in 1946. Osmańczyk condemned anti-Jewish violence in postwar Poland

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

, and concluded:

Features

Forms of hostility toward Poles and Polish culture include: * Organized persecution of the Poles as a nation or as an ethnic group; * A xenophobic dislikes of Poles, including Polish immigrants; * Cultural anti-Polish sentiment: a prejudice against Poles and Polish-speaking persons or their customs, language and education; *Stereotype

In social psychology, a stereotype is a generalized belief about a particular category of people. It is an expectation that people might have about every person of a particular group. The type of expectation can vary; it can be, for example ...

s about Poland and Polish people in the media and other forms of popular culture

Popular culture (also called mass culture or pop culture) is generally recognized by members of a society as a set of practices, beliefs, artistic output (also known as, popular art or mass art) and objects that are dominant or prevalent in a ...

.

A historic example of anti-Polish sentiment was ''polakożerstwo'' (in English, "the devouring of Poles") – a Polish term coined in the 19th century in relation to the dismemberment and annexation of Poland by Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

, the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

and Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

. ''Polakożerstwo'' described the forcible suppression of Polish culture, education and religion in historically Polish territories, and the gradual elimination of Poles from everyday life as well as from owning property. Anti-Polish policies were implemented by the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

under Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of J ...

, especially during the ''Kulturkampf

(, 'culture struggle') was the conflict that took place from 1872 to 1878 between the Catholic Church led by Pope Pius IX and the government of Prussia led by Otto von Bismarck. The main issues were clerical control of education and ecclesiastic ...

'', and enforced up to the end of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Organized persecution of Poles raged in the territories annexed by Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

, mainly under Tsar Nicholas II. Liudmila Gatagova"THE CRYSTALLIZATION OF ETHNIC IDENTITY IN THE PROCESS OF MASS ETHNOPHOBIAS IN THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE. (The Second Half of the 19th Century)."

The CRN E-bookMatthew F. Jacobson,

Special Sorrows: The Diasporic Imagination of Irish, Polish, and Jewish ...

' Page 34, Social Science, Publisher: University of California Press, 2002; 340 pages. Historic actions inspired by anti-Polonism ranged from felonious acts motivated by hatred, to physical extermination of the Polish nation, the goal of which was to eradicate the Polish state. During World War II, when most of Polish society became the object of genocidal policies of Nazi Germany, anti-Polonism led to an unprecedented campaign of mass murder in German-occupied Poland. In the modern day, among those who often express their hostile attitude towards the Polish people are some

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

n politicians and their far-right political parties who search for a new identity rooted in the defunct Russian Empire after the collapse of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

.

Anti-Polish stereotypes

In the Russian language, the term ''mazurik'' ( мазурик), a synonym for "pickpocket", "petty thief", literally means "little Masovian". The word is an example howVladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin; (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who holds the office of president of Russia. Putin has served continuously as president or prime minister since 1999: as prime min ...

's liberal use of colloquialisms has been gaining media attention from abroad.

The " Polish plumber" cliché may symbolize the threat of cheap labor from poorer European countries to "steal" low-paying jobs in wealthier parts of Europe. On the other hand, others associate it with affordability and dependability of European migrant workers.

Before the

Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of ...

, 1918

Anti-Polish rhetoric combined with the condemnation of Polish culture was most prominent in the 18th-century

Anti-Polish rhetoric combined with the condemnation of Polish culture was most prominent in the 18th-century Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

during the partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place toward the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland and Lithuania for 12 ...

. However, anti-Polish propaganda begins with the Teutonic Order

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians on ...

in the 14th century. It was a very important tool in the Order's attempt to conquer the Duchy of Lithuania which eventually failed because of Lithuania's Personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interlink ...

with the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland

The Crown of the Kingdom of Poland ( pl, Korona Królestwa Polskiego; Latin: ''Corona Regni Poloniae''), known also as the Polish Crown, is the common name for the historic Late Middle Ages territorial possessions of the King of Poland, includ ...

and the Christianization of Lithuania to Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. The first major thinker to openly call for the genocide of the Polish people was the 14th century German Dominican theologian Johannes von Falkenberg who on behalf of the Teutonic Order argued not only that Polish pagans should be killed, but that all Poles should be subject to genocide on the grounds that Poles were an inherently heretical race and that even the King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electable position in Europe (16t ...

, Jogaila a Christian convert, ought to be murdered. The assertion that Poles were heretical was largely politically motivated as the Teutonic Order desired to conquer Polish lands despite Christianity having become the dominant religion in Poland centuries prior.

Germany, becoming more and more permeated with Teutonic Prussianism, continued to pursue these tactics. For instance, David Blackbourn of Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

speaks of the scandalised writings of German intellectual Johann Georg Forster, who was granted a tenure at Vilnius University by the Polish Commission of National Education in 1784. Forster wrote of Poland's "backwardness" in a similar vein to "ignorance and barbarism" of southeast Asia. Such views were later repeated in the German ideas of Lebensraum

(, ''living space'') is a German concept of settler colonialism, the philosophy and policies of which were common to German politics from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901, '' lso in:' became a geopolitical goal of Imperi ...

and exploited by the Nazis. German academics between the 18th and 20th centuries attempted to project, in the difference between Germany and Poland, a "boundary between civilization and barbarism; high German Kultur and ''primitive Slavdom''" (1793 racist diatribe by J.C. Schulz republished by the Nazis in 1941). Prussian officials, eager to secure Polish partition, encouraged the view that the Poles were culturally inferior and in need of Prussian tutelage. Such racist texts, originally published from the 18th century onwards, were republished by the German Reich prior to and after its invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week aft ...

.

Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the Sil ...

of Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

nourished a particular hatred and contempt for the Polish people. Following his conquest of Poland, he compared the Poles to "Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

" of Canada. In his all-encompassing anti-Polish campaign, even the nobility of Polish background living in Prussia were obliged to pay higher taxes than those of German heritage. Polish monasteries were viewed as "lairs of idleness" and their property often seized by Prussian authorities. The prevalent Catholicism among Poles was stigmatised. The Polish language

Polish (Polish: ''język polski'', , ''polszczyzna'' or simply ''polski'', ) is a West Slavic language of the Lechitic group written in the Latin script. It is spoken primarily in Poland and serves as the native language of the Poles. In a ...

was persecuted at all levels.

After the Polish–Russian War in early 1600s, Poland was greatly antagonized by the Russians as the cause of chaos and tyranny in Russia. The future House of Romanov, who would found the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

after taken power from the Rurik dynasty

The Rurik dynasty ( be, Ру́рыкавічы, Rúrykavichy; russian: Рю́риковичи, Ryúrikovichi, ; uk, Рю́риковичі, Riúrykovychi, ; literally "sons/scions of Rurik"), also known as the Rurikid dynasty or Rurikids, was ...

, used a number of distortion activities, describing Poles as backward, cruel and heartless, praising the rebellion against Poles; and heavily centered around the Orthodox belief. When Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia or Tsardom of Rus' also externally referenced as the Tsardom of Muscovy, was the centralized Russian state from the assumption of the title of Tsar by Ivan IV in 1547 until the foundation of the Russian Empire by Peter I i ...

invaded Poland at the Russo-Polish war of 1650s, the Russians caused a number of atrocities, and destroyed most of Eastern Poland, sometimes joining destruction with its Ukrainian ally led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Bohdan Zynovii Mykhailovych Khmelnytskyi ( Ruthenian: Ѕѣнові Богданъ Хмелнiцкiи; modern ua, Богдан Зиновій Михайлович Хмельницький; 6 August 1657) was a Ukrainian military commander and ...

and the Swedes in the parallel Swedish invasion. The war was held as a Russian triumph for its attempt to destroy Poland.

Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

, which developed anti-Polish sentiment due to previous Polish–Swedish wars

The Polish–Swedish Wars were a series of wars between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Sweden. Broadly construed, the term refers to a series of wars between 1563 and 1721. More narrowly, it refers to particular wars between 1600 and ...

in hope to gain territorial and political influence, as well as dispute with the Polish Crown because of Sigismund III Vasa, launched an invasion known as the Deluge. Swedish invaders, joined force with Russian invaders in the east, together destroyed Poland and took away many of the Polish national treasures, as well as causing atrocities against Poles. The Poles were treated very brutally by Swedes, and as a result, Poland lost its wealth and was reduced in its development. Similar to Russia, Sweden hailed the destruction of Poland as a national triumph.

At 18th century, Russia as an empire attempted to make Poland disintegrate by using liberum veto, creating chaos and prevented reforms, as by Russian accords, was against the ideal of Imperial Russia's future plan to partition Poland. Russia often sent troops and carried out atrocities on Polish civilians. When Poland adopted its first ever Constitution of 3 May 1791, the first Constitution in Europe, Russia sent troops and brutally suppressed Polish people.

When Poland lost the last vestiges of its independence in 1795 and remained partitioned for 123 years, ethnic Poles were subjected to discrimination in two areas: the Germanisation under Prussian and later German rule, and

When Poland lost the last vestiges of its independence in 1795 and remained partitioned for 123 years, ethnic Poles were subjected to discrimination in two areas: the Germanisation under Prussian and later German rule, and Russification

Russification (russian: русификация, rusifikatsiya), or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians, whether involuntarily or voluntarily, give up their culture and language in favor of the Russian cultur ...

in the territories annexed by Imperial Russia

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the List of Russian monarchs, Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended th ...

.

Being a Pole under the Russian occupation was in itself almost culpable – wrote Russian historian Liudmila Gatagova. – "Practically all of the Russian government, bureaucracy, and society were united in one outburst against the Poles." – "Rumor mongers informed the population about an order that had supposedly been given to kill ..and take away their land." Polish culture

The culture of Poland ( pl, Kultura Polski ) is the product of its geography and distinct historical evolution, which is closely connected to an intricate thousand-year history. Polish culture forms an important part of western civilization and ...

and religion were seen as threats to Russian imperial ambitions. Tsarist Namestniks suppressed them on Polish lands by force. The Russian anti-Polish campaign, which included confiscation of Polish nobles' property, was waged in the areas of education, religion as well as language. Polish schools and universities were closed in a stepped-up campaign of russification. In addition to executions and mass deportations of Poles to Katorga

Katorga ( rus, ка́торга, p=ˈkatərɡə; from medieval and modern Greek: ''katergon, κάτεργον'', "galley") was a system of penal labor in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union (see Katorga labor in the Soviet Union). Prisoner ...

camps, Tsar Nicholas I

, house = Romanov-Holstein-Gottorp

, father = Paul I of Russia

, mother = Maria Feodorovna (Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Gatchina Palace, Gatchina, Russian Empire

, death_date =

...

established an occupation army at Poland's expense.

The fact that Poles, unlike the Russians, were overwhelmingly Roman Catholic gave impetus to their religious persecution. At the same time, with the emergence of Panslavist

Pan-Slavism, a movement which crystallized in the mid-19th century, is the political ideology concerned with the advancement of integrity and unity for the Slavic people. Its main impact occurred in the Balkans, where non-Slavic empires had rule ...

ideology, Russian writers accused the Polish nation of betraying their "Slavic family" because of their armed efforts aimed at winning independence. Hostility toward Poles was present in many of Russia's literary works and media of the time.

Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin (; rus, links=no, Александр Сергеевич ПушкинIn pre-Revolutionary script, his name was written ., r=Aleksandr Sergeyevich Pushkin, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈpuʂkʲɪn, ...

, together with three other poets, published a pamphlet called "On the Taking of Warsaw" to celebrate the crushing of the revolt

''The Revolt'' ( he, המרד), also published as ''Revolt'', ''The Revolt: Inside Story of the Irgun'' and ''The Revolt: the Dramatic Inside Story of the Irgun'', is a book about the militant Zionist organization Irgun Zvai Leumi, by one of it ...

. His contribution to the frenzy of anti-Polish writing comprised poems in which he hailed the capitulation of Warsaw as a new "triumph" of imperial Russia.

In Prussia and later in Germany, Poles were forbidden to build homes, and their properties were targeted for forced buy-outs financed by the Prussian and subsequent German governments. Bismarck described Poles, as animals (wolves), that "one shoots if one can" and implemented several harsh laws aimed at their expulsion from traditionally Polish lands. The Polish language was banned from public use, and ethnically Polish children punished at school for speaking Polish. Poles were subjected to a wave of forceful evictions (''Rugi Pruskie''). The German government financed and encouraged settlement of ethnic Germans into those areas aiming at their geopolitical germanisation. The Prussian Landtag passed laws against Catholics.

Toward the end of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

during Poland's fight for independence, Imperial Germany

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

made further attempts to take control over the territories of Congress Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It w ...

, aiming at ethnic cleansing of up to 3 million Jewish and Polish people which was meant to be followed by a new wave of settlement by ethnic Germans. In August 1914, the German imperial army destroyed the city of Kalisz, chasing out tens of thousands of its Polish citizens.

Interwar Period (1918–39)

After Poland regained its independence as the Second Republic at the end of World War I, the question of new Polish borders could not have been easily settled against the will of her former long-term occupiers. Poles continued to be persecuted in the disputed territories, especially in

After Poland regained its independence as the Second Republic at the end of World War I, the question of new Polish borders could not have been easily settled against the will of her former long-term occupiers. Poles continued to be persecuted in the disputed territories, especially in Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

. The German campaign of discrimination contributed to the Silesian Uprisings

The Silesian Uprisings (german: Aufstände in Oberschlesien, Polenaufstände, links=no; pl, Powstania śląskie, links=no) were a series of three uprisings from August 1919 to July 1921 in Upper Silesia, which was part of the Weimar Republic ...

, where Polish workers were openly threatened with losing their jobs and pensions if they voted for Poland in the Upper Silesia plebiscite

The Upper Silesia plebiscite was a plebiscite mandated by the Versailles Treaty and carried out on 20 March 1921 to determine ownership of the province of Upper Silesia between Weimar Germany and Poland. The region was ethnically mixed with bot ...

.

At the Versailles Peace Conference of 1919, British historian and politician Lewis Bernstein Namier, who served as part of the British delegation, was seen as one of the biggest enemies of the newly independent Polish state in the British political sphere and in the newly-independent Poland. Namier modified the previously-proposed Curzon line

The Curzon Line was a proposed demarcation line between the Second Polish Republic and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Soviet Union, two new states emerging after World War I. It was first proposed by George Curzon, 1st Marque ...

by detaching the city of Lwów

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukraine ...

from Poland with a version called Curzon Line "A". It was sent to Soviet diplomatic representatives for acceptance. The earlier compromised version of Curzon line which was debated at the Spa Conference of 1920

The Spa Conference was a meeting between the Supreme War Council and the government of the Weimar Republic in Spa, Belgium on 5–16 July 1920. The main topics were German disarmament, coal shipments to the Allies and war reparations.

Attendees

...

was renamed Curzon Line "B".

In the politics of inter-war Germany, anti-Polish feelings ran high.Gerhard L. Weinberg

In the politics of inter-war Germany, anti-Polish feelings ran high.Gerhard L. Weinberg''Germany, Hitler, and World War II: essays in modern German and world history''

Cambridge University Press, 1995, page 42. The American historian Gerhard Weinberg observed that for many Germans in the Weimar Republic, "Poland was an abomination", Poles were "an East European species of cockroach", Poland was usually described as a ''Saisonstaat'' (a state for a season), and Germans used the phrase "Polish economy" (''polnische Wirtschaft'') for a situation of hopeless muddle. Weinberg noted that in the 1920s–30s, leading German politicians refused to accept Poland as a legitimate nation, and hoped instead to partition Poland, probably with the help of the Soviet Union. The British historian

A. J. P. Taylor

Alan John Percivale Taylor (25 March 1906 – 7 September 1990) was a British historian who specialised in 19th- and 20th-century European diplomacy. Both a journalist and a broadcaster, he became well known to millions through his televis ...

wrote in 1945 that National Socialism was inevitable because the Germans wanted "to repudiate the equality with the peoples of (central and) eastern Europe which had then been forced upon them" after 1918.

During Stalin's Great Terror in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, a major ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

operation, known as the Polish Operation, took place from about 25 August 1937 through 15 November 1938. According to Soviet NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

archives, 111,091 Poles, and people accused of ties with Poland, were executed, and 28,744 were sentenced to Gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= was the government agency in ...

labor camp

A labor camp (or labour camp, see spelling differences) or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have many common aspects with slavery and with prisons (especi ...

s, for a total of 139,835 Polish victims. This number constitutes 10 per cent of the officially persecuted persons during the entire Yezhovshchina

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

period, with confirming NKVD documents. The prosecuted Polish families were accused of anti-Soviet activities.

Outside the Germans and Russians, the Lithuanians also developed a very strong anti-Polish hatred, partly due to historical grievances. For the Lithuanians, the Polish–Lithuanian War

The Polish–Lithuanian War (in Polish historiography, Polish–Lithuanian Conflict) was an undeclared war between newly-independent Lithuania and Poland following World War I, which happened mainly, but not only, in the Vilnius and Suwałki regi ...

of 1920, which costed the capital Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urb ...

to be on Polish hand, cemented anti-Polish sentiment. Virtually throughout the inter-war, anti-Polish had been omnipresent in Lithuania, and Polish minority in Lithuania faced a very harsh repression by the Lithuanian authorities. The 1938 Polish ultimatum to Lithuania

The 1938 Polish ultimatum to Lithuania was delivered to Lithuania by Poland on March 17, 1938. The Lithuanian government had steadfastly refused to have any diplomatic relations with Poland after 1920, protesting the annexation of the Vilnius R ...

led to the establishment of relations, but it remained extremely difficult as Lithuania still refused to accept Vilnius as part of Poland.

Ukrainians were also another people with strong anti-Polish hostility. The Polish–Ukrainian War of 1919 resulted in Ukraine crippled militarily and, though Poland did assist Ukraine in the eventual conflict against the Bolsheviks, but was unable to prevent an eventual occupation by the Soviets

Soviet people ( rus, сове́тский наро́д, r=sovyétsky naród), or citizens of the USSR ( rus, гра́ждане СССР, grázhdanye SSSR), was an umbrella demonym for the population of the Soviet Union.

Nationality policy in th ...

. This had led to enmity against Poland by Ukrainian nationalists, which resulted in the establishment of Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and the beginning of Ukrainian problem in Poland. Assassinations of Polish officials by Ukrainian nationalists became increasingly frequent from 1930s onward.

Invasion of Poland and World War II

Nazi propagandists stereotyped Poles as nationalists in order to portray Germans as victims and justify the

Nazi propagandists stereotyped Poles as nationalists in order to portray Germans as victims and justify the invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week aft ...

; the Gleiwitz incident was a Nazi false flag

A false flag operation is an act committed with the intent of disguising the actual source of responsibility and pinning blame on another party. The term "false flag" originated in the 16th century as an expression meaning an intentional misr ...

to show that Germany was under Polish attack, and the killing of Germans by Poles in ''Bromberger Blutsonntag

Bloody Sunday (german: Bromberger Blutsonntag; pl, Krwawa niedziela) was a sequence of violent events that took place in Bydgoszcz (german: Bromberg), a Polish city with a sizable German minority, between 3 and 4 September 1939, during the Germa ...

'' and elsewhere was inflated to 58,000 to increase German hatred of Poles and justify the killing of Polish civilians.

In October 1939, Directive No.1306 of Nazi Germany's Propaganda Ministry stated: "It must be made clear even to the German milkmaid that Polishness equals subhumanity. Poles, Jews and Gypsies are on the same inferior level... This should be brought home as a ''leitmotiv'', and from time to time, in the form of existing concepts such as 'Polish economy', 'Polish ruin' and so on, until everyone in Germany sees every Pole, whether farm worker or intellectual, as vermin."From Peace to War: Germany, Soviet Russia, and the World, 1939-1941 (1997), by Sheldon Dick ed. Bernd Wegner

Bernd Wegner (born 1949) is a German historian who specialises in military history and the history of Nazism. Since 1997 he has been professor of modern history at the Helmut Schmidt University in Hamburg, Germany.

Wegner is a contributor to th ...

, p.50

Historian Karol Karski

Karol Adam Karski (born 13 May 1966 in Warsaw) is a Polish politician, Quaestor of the European Parliament, and a former Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs. He holds a Doctor of Law degree from the University of Warsaw. Karski has taught at the Un ...

writes that before World War II the Soviet authorities carried out a discreditation campaign against the Poles and describes Stalin as Polonophobe.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

Poles became the subject of ethnic cleansing on an unprecedented scale, including: Nazi German genocide in General Government

The General Government (german: Generalgouvernement, pl, Generalne Gubernatorstwo, uk, Генеральна губернія), also referred to as the General Governorate for the Occupied Polish Region (german: Generalgouvernement für die be ...

, Soviet executions and mass deportations to Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

from Kresy, as well as massacres of Poles in Volhynia

The massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia ( pl, rzeź wołyńska, lit=Volhynian slaughter; uk, Волинська трагедія, lit=Volyn tragedy, translit=Volynska trahediia), were carried out in German-occupied Poland by the ...

, a campaign of ethnic cleansing carried out in today's western Ukraine by Ukrainian nationalists. Among the 100,000 people murdered in the '' Intelligenzaktion'' operations in 1939–1940, approximately 61,000 were members of the Polish intelligentsia. Millions of citizens of Poland, both ethnic Poles and Jews, died in German concentration camps such as Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

. Unknown numbers perished in Soviet "gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= was the government agency in ...

s" and political prisons.

Reprisals against partisan activities were brutal; on one occasion 1,200 Poles were murdered in retaliation for the death of one German officer and two German officials. In August 2009 the Polish Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) researchers estimated Poland's dead (including Polish Jews) at between 5.47 and 5.67 million (due to German actions) and 150,000 (due to Soviet), or around 5.62 and 5.82 million total.

Soviet policy following their 1939 invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week aft ...

in World War II was ruthless, and sometimes coordinated with the Nazis (see: Gestapo-NKVD Conferences). Elements of ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

included Soviet mass executions of Polish prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

in the Katyn Massacre

The Katyn massacre, "Katyń crime"; russian: link=yes, Катынская резня ''Katynskaya reznya'', "Katyn massacre", or russian: link=no, Катынский расстрел, ''Katynsky rasstrel'', "Katyn execution" was a series of m ...

and at other sites, and the exile of up to 1.5 million Polish citizens, including the intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the in ...

, academics, priests and Jewish Poles to forced-labor camps in Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

.

In German and Soviet war propaganda, Poles were mocked as inept for their military techniques in fighting the war. Nazi fake newsreels and forged pseudo-documentaries claimed that the Polish cavalry "bravely but futilely" charged German tanks in 1939, and that the Polish Air Force

The Polish Air Force ( pl, Siły Powietrzne, , Air Forces) is the aerial warfare branch of the Polish Armed Forces. Until July 2004 it was officially known as ''Wojska Lotnicze i Obrony Powietrznej'' (). In 2014 it consisted of roughly 16,425 mil ...

was wiped out on the ground on the opening day of the war. Neither tale was true (see: Myths of the Polish September Campaign). German propaganda staged a Polish cavalry charge in their 1941 reel called "Geschwader Lützow".

Ukrainian and Lithuanian nationalists utilized the increasing racial segregation to foment anti-Polonism. Followers of Stepan Bandera (also called Banderovites) committed genocide on Poles in Volhynia

Volhynia (also spelled Volynia) ( ; uk, Воли́нь, Volyn' pl, Wołyń, russian: Волы́нь, Volýnʹ, ), is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between south-eastern Poland, south-western Belarus, and western Ukraine. Th ...

at 1943. Lithuanian forces often clash with Polish forces throughout the World War II, and committed massacre on Poles with support from the Nazis.

Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence and t ...

often assigned blame to the failure of his operations, such as Operation Market Garden

Operation Market Garden was an Allies of World War II, Allied military operation during the World War II, Second World War fought in the Netherlands from 17 to 27 September 1944. Its objective was to create a Salient (military), salient into G ...

, to the Polish troops under his command. Poland's relationship with the USSR during World War II was complicated. The main western Allies, the United States and the United Kingdom, understood the importance of the Soviet Union in defeating Germany, to the point of refusing to condemn Soviet propaganda which vilified their Polish ally. The western Allies were even willing to help cover up the Soviet massacre at Katyn.

Zofia Kossak-Szczucka

Zofia Kossak-Szczucka ( (also Kossak-Szatkowska); 10 August 1889 – 9 April 1968) was a Polish writer and World War II resistance fighter. She co-founded two wartime Polish organizations: Front for the Rebirth of Poland and Żegota, set up t ...

, the Catholic co-founder of Zegota, the Polish resistance group which risked the German death penalty to save Jews, and who herself was sent to Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

, stereotyped Jews as haters of Poles even as she characterized Poles who remained silent in the face of the Holocaust as complicit:Post-war

Under

Under Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

, thousands of soldiers of Poland's underground eg. Home Army

The Home Army ( pl, Armia Krajowa, abbreviated AK; ) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) esta ...

(''Armia Krajowa

The Home Army ( pl, Armia Krajowa, abbreviated AK; ) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) esta ...

'') and returning veterans of the Polish Armed Forces that had served with the western Allies were imprisoned, tortured by Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

agents (see: W. Pilecki, Ł. Ciepliński) and murdered following staged trial

A show trial is a public trial in which the judicial authorities have already determined the guilt or innocence of the defendant. The actual trial has as its only goal the presentation of both the accusation and the verdict to the public so ...

s like the infamous Trial of the Sixteen in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

, Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. A similar fate awaited the " cursed soldiers". At least 40,000 members of Poland's Home Army were deported to Russia.

In Britain after 1945, the British populace accepted the Polish servicemen who chose not to return to a Poland ruled by the communist regime in their decision to stay on in Britain. The Poles resident in Britain served under British command during the war, but as soon as the Soviets began to make gains on the Eastern Front both public opinion and the government turned increasingly pro-Soviet. Socialist supporters of the Soviet Union made the Poles out to be "warmongers", "anti-Semites" and "fascists".The Poles in Britain 1940–2000 by Peter D. Stachura

Peter D. Stachura is a British historian, writer, lecturer and essayist. He was Professor of Modern European History at the University of Stirling and Director of its Centre for Research in Polish History. He has published extensively on the subj ...

, Page 52 After the war, the trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

s and Labour party played on the fears among the public of there not being enough jobs, food and housing to incite anti-Polish sentiments.

The myth that Poland had been conducting a genocide against ethnic Germans was invented in 1940 by German nationalist writer by embellishing the events of "Bloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday may refer to:

Historical events Canada

* Bloody Sunday (1923), a day of police violence during a steelworkers' strike for union recognition in Sydney, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia

* Bloody Sunday (1938), police violence agai ...

". In 1961, a book was published in Germany entitled ''Der Erzwungene Krieg'' (The Forced War) by the American historical writer and Holocaust denier David Hoggan

David Leslie Hoggan (March 23, 1923 – August 7, 1988) was an American professor of history, author of ''The Forced War: When Peaceful Revision Failed'' and other works in the German and English languages. He was antisemitic, maintained ...

, which argued that Germany did not commit aggression against Poland in 1939, but was instead the victim of an Anglo-Polish conspiracy against the ''Reich''. Reviewers have often noted that Hoggan seems to have an obsessive hostility towards the Poles. His claims included that the Polish government treated Poland's German minority far worse than the German government under Adolf Hitler treated its Jewish minority. In 1964, much controversy was created when two German right-wing extremist groups awarded Hoggan prizes. In the 1980s, the German philosopher and historian Ernst Nolte claimed that in 1939 Poland was engaged in a campaign of genocide against its ethnic German minority, and has strongly implied that the German invasion in 1939, and all of the subsequent German atrocities in Poland during World War II were in essence justified acts of retaliation.Evans, Richard J. ''In Hitler's Shadow'' New York: Pantheon Books, 1989 pages 56–57 Critics, such as the British historian Richard J. Evans

Sir Richard John Evans (born 29 September 1947) is a British historian of 19th- and 20th-century Europe with a focus on Germany. He is the author of eighteen books, including his three-volume ''The Third Reich Trilogy'' (2003–2008). Evans was ...

, have accused Nolte of distorting the facts, and have argued that in no way was Poland committing genocide against its German minority.

During the political transformation of the Soviet-controlled Eastern bloc in the 1980s, the traditional German anti-Polish feeling was again openly exploited in the East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

against Solidarność. This tactic had become especially apparent in the "rejuvenation of 'Polish jokes

A "Polish joke" is an English-language ethnic joke deriding Polish people, based on derogatory stereotypes. The "Polish joke" belongs in the category of conditional jokes, whose full understanding requires the audience to have prior knowledge of wh ...

,' some of which reminded listeners of the spread of such jokes under the Nazis."

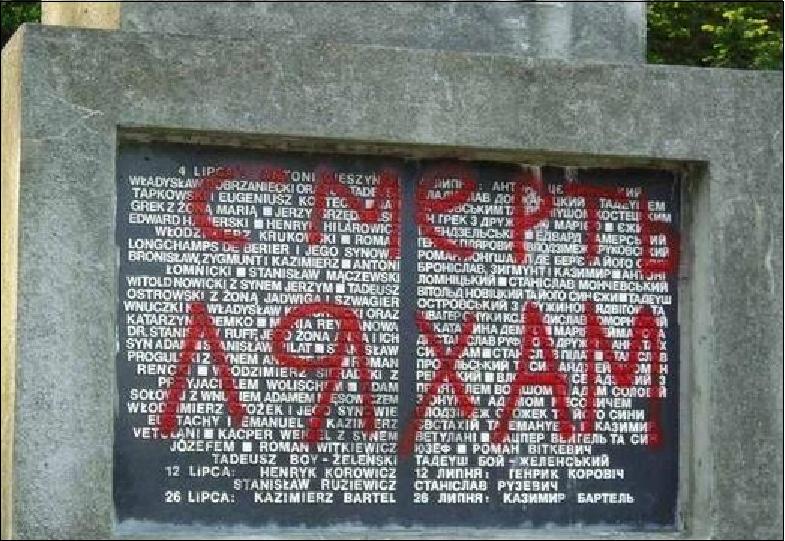

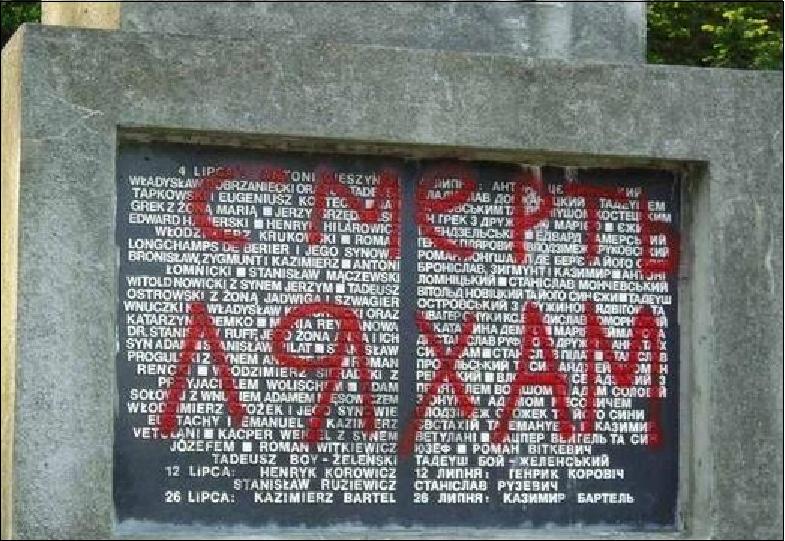

"Polish death camp" controversy

The expressions offensive to Poles are attributed to a number of non-Polish media in relation to . The most prominent is a continued reference by Western news media to "Polish death camps" and "Polish concentration camps". These phrases refer to the network of concentration camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland in order to facilitate the " Final Solution", but the wording suggests that the Polish people might have been involved. The PolishMinistry of Foreign Affairs In many countries, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the government department responsible for the state's diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral relations affairs as well as for providing support for a country's citizens who are abroad. The entit ...

, as well as Polish organizations around the world and all Polish government

The Government of Poland takes the form of a Unitary state, unitary Parliamentary republic, parliamentary Representative democracy, representative democratic republic, whereby the President of Poland, President is the head of state and the Prime ...

s since 1989, condemned the usage of such expressions, arguing that they suggest Polish responsibility for the camps. The American Jewish Committee

The American Jewish Committee (AJC) is a Jewish advocacy group established on November 11, 1906. It is one of the oldest Jewish advocacy organizations and, according to ''The New York Times'', is "widely regarded as the dean of American Jewish org ...

stated in its 30 January 2005, press release: "This is not a mere semantic matter. Historical integrity and accuracy hang in the balance.... Any misrepresentation of Poland's role in the Second World War, whether intentional or accidental, would be most regrettable and therefore should not be left unchallenged."

In Polish-Jewish relations

There is a stereotype that Jews are anti-Polish. CardinalJózef Glemp

Józef Glemp (18 December 192923 January 2013) was a Polish cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church. He was Archbishop of Warsaw from 1981 to 2006, and was elevated to the cardinalate in 1983.

Biography

Early life and ordination

Józef Glemp was ...

in his controversial and widely criticized speech delivered on 26 August 1989 (and retracted in 1991) argued that the outbursts of antisemitism are a "legitimate form of national self-defence against Jewish anti-Polonism." He "asked Jews who 'have great power over the mass media in many countries' to rein in their anti-Polonism because 'if there won't be anti-Polonism, there won't be such antisemitism among us'."

In November of the same year, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir

Yitzhak Shamir ( he, יצחק שמיר, ; born Yitzhak Yezernitsky; October 22, 1915 – June 30, 2012) was an Israeli politician and the seventh Prime Minister of Israel, serving two terms, 1983–1984 and 1986–1992. Before the establishment ...

said Poles “drink in (anti-Semitism) with their mother's milk.” Polish Prime Minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki said that “these blanket statements are the most destructive actions imaginable,” and that they “do irreparable harm” to people seeking Polish-Jewish reconciliation. Adam Michnik wrote for ''The New York Times'' that "almost all Poles react very sharply when confronted with the charge that Poles get their anti-Semitism 'with their mothers' milk'." Such verbal attacks – according to Michnik – are interpreted by anti-Semites as "proof of the international anti-Polish Jewish conspiracy".

In ''Rethinking Poles and Jews'', Robert Cherry and Annamaria Orla-Bukowska said that anti-Polonism and anti-Semitism remain "grotesquely twinned into our own time. We cannot combat the one without combating the other."

The term "anti-Polonism" is said to have been used for campaign purposes by political parties such as the League of Polish Families

The League of Polish Families (Polish: ''Liga Polskich Rodzin'', LPR) is a conservative political party in Poland, with many far-right elements in the past. The party's original ideology was that of the National Democracy movement which was heade ...

( pl, Liga Polskich Rodzin) or the defunct Self-Defence of the Republic of Poland ( pl, Samoobrona Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej) and organizations such as the Association against Anti-Polonism led by Leszek Bubel, leader of the Polish National Party

The Polish National Party ( pl, Polska Partia Narodowa) was a fringe nationalist and ultra-conservative political party in Poland led by Leszek Bubel. Its motto was: "I am Polish, therefore I have Polish obligations", as quoted after the Polish ...

and a former presidential candidate. Bubel was taken to court by a group of ten Polish intellectuals who filed a lawsuit against him for "violating the public good". Among the signatories were former Foreign Minister Władysław Bartoszewski and filmmaker Kazimierz Kutz.

According to Polish historian Joanna Michlic

Joanna Beata Michlic is a Polish social and cultural historian specializing in Polish-Jewish history and the Holocaust in Poland. An honorary senior research associate at the Centre for Collective Violence, Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Un ...

, the term is used in Poland also as an argument against the self-critical intellectuals who discuss Polish-Jewish relations, accusing them of "anti-Polish positions and interests." For example, historian Jan T. Gross

Jan Tomasz Gross (born 1947) is a Polish-American sociologist and historian. He is the Norman B. Tomlinson '16 and '48 Professor of War and Society, emeritus, and Professor of History, emeritus, at Princeton University.

Gross is the author o ...

has been accused of being anti-Polish when he wrote about crimes such as the Jedwabne pogrom. In her view, the charge is "not limited to arguments that can objectively be classified as anti-Polish—such as equating the Poles with the Nazis—but rather applied to any critical inquiry into the collective past. Moreover, anti-Polonism is equated with anti-Semitism."

For the 1994 anniversary of the Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising ( pl, powstanie warszawskie; german: Warschauer Aufstand) was a major World War II operation by the Polish resistance movement in World War II, Polish underground resistance to liberate Warsaw from German occupation. It occ ...

, a Polish ''Gazeta Wyborcza'' journalist, Michał Cichy, wrote a review of a collection of 1943 memoirs entitled ''Czy ja jestem mordercą?'' (''Am I a murderer?'') by Calel Perechodnik

Calel (Calek) Perechodnik (; 8 September 1916 – October 1944) was a diary, diarist who joined the Jewish Ghetto Police in the Otwock Ghetto during the Nazi German Occupation of Poland (1939–1945), occupation of Poland. His wartime diaries we ...

, a Jewish ghetto policeman from Otwock and member of the "Chrobry II Battalion

The Chrobry II Battalion was a unit, formally subordinate to the Polish Home Army (AK), which took part in the Warsaw Uprising. It was named after the Polish king Bolesław I Chrobry ("Chrobry" is old Polish for "valiant"Gunnar S. Paulsson, "Secr ...

", Romuald BuryJAKA „GAZETA”, TAKIE PRZEPROSINY...

, PolskieJutro, Number 243 January 2007/ref> alleging (as hearsay) that about 40 Jews were killed by a group of Polish insurgents during the 1944 Uprising. Unlike the book (later reprinted with factual corrections), the actual review by Cichy elicited protests, while selected fragments of his article were confirmed by three Polish historians. Prof.

Tomasz Strzembosz

Tomasz Strzembosz (11 September 1930 – 16 October 2004) was a Polish historian and writer who specialized in the World War II history of Poland. He was a professor at the Polish Academy of Sciences Institute of Political Studies, in Warsaw; an ...

accused Cichy of practicing a 'distinct type of racism,' and charged ''Gazeta Wyborcza'' editor Adam Michnik with 'cultivating a species of tolerance that is absolutely intolerant of antisemitism yet regards anti-Polonism and anti-goyism as something altogether natural'." Michnik responded to the controversy, praising the heroism of the AK by asking: "Is it an attack on Polish people when the past is being explored to seek the truth?". Cichy later apologized for the tone of his article.

Polish historian Adam Leszczyński

Adam Janusz Leszczyński (born 26 November 1975, Warsaw) is a Polish historian and journalist, associate professor at the Institute for Political Studies of the Polish Academy of Sciences.

Works

*''Skok w nowoczesność: Polityka wzrostu w krajac ...

states that "Antisemitism is an extensive doctrine with racist or religious grounds that led to the Holocaust. 'Antipolonism' is at best a generalized aversion to Poles."

"Polish jokes"

"Polish jokes" belong to a category of conditional jokes, meaning that their understanding requires knowledge of ''what a Polish joke is.'' Conditional jokes depend on the audience's ''affective'' preference—on their likes and dislikes. Though these jokes might be understood by many, their success depends entirely on the negative disposition of the listener. Presumably the first Polish jokes by German displaced persons fleeing war-torn Europe were brought to theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

in the late 1940s. These jokes were fueled by ethnic slurs disseminated by German National Socialist

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

propaganda, which attempted to justify the Nazis' murdering of Poles by presenting them as "''dreck''"—dirty, stupid and inferior. It is also possible that some early American '' Polack'' jokes from Germany were originally told before World War II in disputed border regions such as Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

.

There is debate as to whether the early "Polish jokes" brought to states such as Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

by German immigrants relate directly to the wave of American jokes of the early 1960s. A "provocative critique of previous scholarship on the subject" has been made by British writer Christie Davies

John Christopher Hughes "Christie" Davies (25 December 1941 – 26 August 2017) was a British sociologist, professor emeritus of sociology at the University of Reading, England, the author of many articles and books on criminology, the sociolog ...

in ''The Mirth of Nations'', which suggests that "Polish jokes" did not originate in Nazi Germany but much earlier, as an outgrowth of regional jokes rooted in "social class differences reaching back to the nineteenth century." According to Davies, American versions of Polish jokes are an unrelated "purely American phenomenon" and do not express the "historical Old World hatreds of the Germans for the Poles. However, Hollywood in the 1960s and 1970s imported the subhuman-intelligence jokes about Poles from old Nazi propaganda."

For decades, Polish Americans have been the subject of derogatory jokes originating in anti-immigrant stereotypes that had developed in the U.S. before the 1920s. During the Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place toward the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland and Lithuania for 12 ...

, Polish immigrants came to the United States in considerable numbers, fleeing mass persecution at home. They were taking the only jobs available to them, usually requiring physical labor. The same ethnic and job-related stereotypes persisted even as Polish Americans joined the middle class in the mid-20th century. "The constant derision, often publicly disseminated through the mass media, caused serious identity crises, feeling of inadequacy, and low self-esteem for many Polish Americans." In spite of the plight of Polish people under Cold War communism, negative stereotypes about Polish Americans endured.Dominic Pulera''Sharing the Dream: White Males in Multicultural America''

Published 2004 by Continuum International Publishing Group, 448 pages. . Page 99. Since the late 1960s, Polish American organizations have made continuous effort to challenge the negative stereotyping of the Polish people once prevalent in American media. The Polish American Guardian Society has argued that NBC-TV used the tremendous power of TV to introduce and push subhuman intelligence jokes about Poles (that were worse than prior simple anti-immigrant jokes) using the repetitive big lie technique to degrade Poles. The play called “Polish Joke” by David Ives has resulted in a number of complaints by the Polonia in the US. The "Polish jokes" heard in the 1970s were particularly offensive, so much so that the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs approached the U.S. State Department about that, however unsuccessfully. The syndrome receded only after Cardinal

Karol Wojtyła

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

was elected Pope, and Polish jokes became passé. Gradually, Americans have developed a more positive image of their Polish neighbors in the following decades.

In 2014, a German speaker joked during the European Aquatics Championships

The European Aquatics Championships is the continental Aquatics championship for Europe, which is organised by LEN—the governing body for aquatics in Europe. The Championships are currently held every two years (in even years); and since 2022, ...

that the Polish team would be coming back home in "our cars".

Today

United Kingdom

Since theEU enlargement

The European Union (EU) has expanded a number of times throughout its history by way of the accession of new member states to the Union. To join the EU, a state needs to fulfil economic and political conditions called the Copenhagen criteria ...

in 2004, where ten new countries joined in the single-largest expansion to date (Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

, Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The ...

, Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, a ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

, Latvia

Latvia ( or ; lv, Latvija ; ltg, Latveja; liv, Leţmō), officially the Republic of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Republika, links=no, ltg, Latvejas Republika, links=no, liv, Leţmō Vabāmō, links=no), is a country in the Baltic region of ...

, Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

, Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

, Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

and Slovenia

Slovenia ( ; sl, Slovenija ), officially the Republic of Slovenia (Slovene: , abbr.: ''RS''), is a country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the southeast, an ...

), the UK has experienced mass immigration from Poland (see Poles in the United Kingdom

British Poles, alternatively known as Polish British people or Polish Britons, are ethnic Poles who are citizens of the United Kingdom. The term includes people born in the UK who are of Polish descent and Polish-born people who reside in the UK ...

). It is estimated that the Polish British

British Poles, alternatively known as Polish British people or Polish Britons, are ethnic Poles who are citizens of the United Kingdom. The term includes people born in the UK who are of Polish descent and Polish-born people who reside in the UK ...

community has doubled in size since 2004; with Poland now having overtaken India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

as the largest foreign-born country of origin in 2015 (831,000 Poles to 795,000 Indian-born persons). Anti-Polish sentiment in the UK is often related to the issue of immigration. There have been some instances of anti-Polish sentiment and hostility towards Polish immigrants. The far-right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

British National Party argued for immigration from (Central and) Eastern Europe to be stopped and for Poles to be deported.

In 2007, Polish people living in London reported 42 ethnically motivated attacks against them, compared with 28 in 2004. The Conservative MP Daniel Kawczynski

Daniel Robert Kawczynski ( pl, Kawczyński, ; born 24 January 1972) is a British Conservative Party politician.

Kawczynski has served as Parliamentary Private Secretary at the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, a parliamentary ...

, of Polish origin himself, said that the increase in violence towards Poles is in part "a result of the media coverage by the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board ex ...

" whose reporters "won't dare refer to controversial immigration from other countries."BBC denies MP's anti-Polish claimBBC News, 4 June 2008. Kawczynski voiced his criticism of the BBC in the House of Commons for "using the Polish community as a cat's paw to try to tackle the thorny issue of mass, unchecked immigration" only because against Poles "it's politically correct to do so." In 2009, the

Federation of Poles in Great Britain

The Federation of Poles in Great Britain ( pl, Zjednoczenie Polskie w Wielkiej Brytanii) is a voluntary umbrella organisation established to promote the interests of Poles in the United Kingdom and to promote the history of Poland, history and cul ...

and the Polish Embassy in London with Barbara Tuge-Erecinska

Barbara may refer to:

People

* Barbara (given name)