Polk Administration on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The abolitionist Liberty party nominated Michigan's James G. Birney, while the

The abolitionist Liberty party nominated Michigan's James G. Birney, while the

Polk was inaugurated as the nation's 11th president on March 4, 1845, in a ceremony held on the East Portico of the

Polk was inaugurated as the nation's 11th president on March 4, 1845, in a ceremony held on the East Portico of the

Polk governed with the help of his cabinet, in which he placed great importance. The cabinet regularly met twice a week, and Polk and his six cabinet members discussed all major issues during these meetings.Merry, pg. 134–135 Despite his reliance on his cabinet, Polk involved himself in the minutiae of the various departments, especially regarding the military.Merry, pg. 269–270

In selecting a new cabinet, Polk generally heeded Jackson's advice to avoid individuals who were themselves interested in the presidency, though he chose to nominate Buchanan for the crucial and prestigious position of Secretary of State.Merry, pg. 114–117Seigenthaler, pp. 104–106 Polk respected Buchanan's opinion and Buchanan played an important role in Polk's presidency, but the two often clashed over foreign policy and appointments. Polk frequently considered dismissing Buchanan from office, as he suspected Buchanan of placing his own presidential aspirations above service to Polk, but Buchanan always managed to convince Polk of his loyalty.Merry, pg. 439–440

Polk put together an initial slate of cabinet choices that met with the approval of Andrew Jackson, who Polk met with in January 1845 for the last time, as Jackson died in June 1845.

Polk governed with the help of his cabinet, in which he placed great importance. The cabinet regularly met twice a week, and Polk and his six cabinet members discussed all major issues during these meetings.Merry, pg. 134–135 Despite his reliance on his cabinet, Polk involved himself in the minutiae of the various departments, especially regarding the military.Merry, pg. 269–270

In selecting a new cabinet, Polk generally heeded Jackson's advice to avoid individuals who were themselves interested in the presidency, though he chose to nominate Buchanan for the crucial and prestigious position of Secretary of State.Merry, pg. 114–117Seigenthaler, pp. 104–106 Polk respected Buchanan's opinion and Buchanan played an important role in Polk's presidency, but the two often clashed over foreign policy and appointments. Polk frequently considered dismissing Buchanan from office, as he suspected Buchanan of placing his own presidential aspirations above service to Polk, but Buchanan always managed to convince Polk of his loyalty.Merry, pg. 439–440

Polk put together an initial slate of cabinet choices that met with the approval of Andrew Jackson, who Polk met with in January 1845 for the last time, as Jackson died in June 1845.

The

The

Since the signing of the

Since the signing of the

In September 1847,

In September 1847,

Polk had been anxious to establish a territorial government for Oregon once the treaty was effective in 1846, but the matter became embroiled in the arguments over slavery, though few thought Oregon suitable for that institution. A bill to establish an Oregon territorial government passed the House after being amended to bar slavery; the bill died in the Senate when opponents ran out the clock on the congressional session. A resurrected bill, still barring slavery, again passed the House in January 1847, but it was not considered by the Senate before Congress adjourned in March. By the time Congress met again in December, California and New Mexico were in U.S. hands, and Polk in his annual message urged the establishment of territorial governments in California, New Mexico, and Oregon. The

Polk had been anxious to establish a territorial government for Oregon once the treaty was effective in 1846, but the matter became embroiled in the arguments over slavery, though few thought Oregon suitable for that institution. A bill to establish an Oregon territorial government passed the House after being amended to bar slavery; the bill died in the Senate when opponents ran out the clock on the congressional session. A resurrected bill, still barring slavery, again passed the House in January 1847, but it was not considered by the Senate before Congress adjourned in March. By the time Congress met again in December, California and New Mexico were in U.S. hands, and Polk in his annual message urged the establishment of territorial governments in California, New Mexico, and Oregon. The

Authoritative word of the discovery of gold in California did not arrive in Washington until after the 1848 election, by which time Polk was a lame duck. Polk was delighted by the discovery of gold, seeing it as validation of his stance on expansion, and he referred to the discovery several times in his final annual message to Congress that December. Shortly thereafter, actual samples of the California gold arrived, and Polk sent a special message to Congress on the subject. The message, confirming less authoritative reports, caused large numbers of people to move to California, both from the U.S. and abroad, thus helping to spark the

Authoritative word of the discovery of gold in California did not arrive in Washington until after the 1848 election, by which time Polk was a lame duck. Polk was delighted by the discovery of gold, seeing it as validation of his stance on expansion, and he referred to the discovery several times in his final annual message to Congress that December. Shortly thereafter, actual samples of the California gold arrived, and Polk sent a special message to Congress on the subject. The message, confirming less authoritative reports, caused large numbers of people to move to California, both from the U.S. and abroad, thus helping to spark the

Honoring his pledge to serve only one term, Polk declined to seek re-election in 1848. With Polk out of the race, the Democratic Party remained fractured along geographic lines.Merry, pg. 376–377 Polk privately favored Lewis Cass as his successor, but resisted becoming closely involved in the election. At the

Honoring his pledge to serve only one term, Polk declined to seek re-election in 1848. With Polk out of the race, the Democratic Party remained fractured along geographic lines.Merry, pg. 376–377 Polk privately favored Lewis Cass as his successor, but resisted becoming closely involved in the election. At the

Polk's historic reputation was largely formed by the attacks made on him in his own time. Whig politicians claimed that he was drawn from a well-deserved obscurity.

Polk's historic reputation was largely formed by the attacks made on him in his own time. Whig politicians claimed that he was drawn from a well-deserved obscurity.

online

* Devoti, John. "The patriotic business of seeking office: James K. Polk and the patronage" (PhD dissertation, Temple University; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2005. 3203004). * De Voto, Bernard. ''The Year of Decision: 1846''. Houghton Mifflin, 1943. * Eisenhower, John S. D. "The Election of James K. Polk, 1844". ''Tennessee Historical Quarterly''. 53.2 (1994): 74–87. ; popular. * Graff, Henry F., ed. ''The Presidents: A Reference History'' (3rd ed. 2002)

online

* Greenstein, Fred I. "The policy-driven leadership of James K. Polk: making the most of a weak presidency." ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 40#4 (2010), p. 725+

online

* Heidt, Stephen J. “Presidential Power and National Violence: James K. Polk’s Rhetorical Transfer of Savagery.” ''Rhetoric and Public Affairs'' 19#3 (2016), pp. 365–96

online

* Kornblith, Gary J. "Rethinking the Coming of the Civil War: a Counterfactual Exercise". ''Journal of American History'' 90.1 (2003): 76–105. . Asks what if Polk had not gone to war? * Leonard, Thomas. ''James K. Polk: A Clear and Unquestionable Destiny'' (Scholarly Resources Inc, 2001). * McCormac, Eugene Irving. ''James K. Polk: A Political Biography to the End of a Career, 1845–1849''. Univ. of California Press, 1922. (1995 reprint has .) hostile to Jacksonians * Merk, Frederick. ''Manifest Destiny and Mission in American History: A Reinterpretation'' (Vintage Books, 1966). * Morrison, Michael A. "Martin Van Buren, the Democracy, and the Partisan Politics of Texas Annexation". ''Journal of Southern History'' 61.4 (1995): 695–724. . Discusses the election of 1844. * Nau, Henry R. “James K. Polk: Manifest Destiny.” in ''Conservative Internationalism: Armed Diplomacy under Jefferson, Polk, Truman, and Reagan'' (Princeton University Press, 2013), pp. 110–46

online

* Nelson, Anna Louise Kasten. "The Secret Diplomacy of James K. Polk during the Mexican War, 1846–1847" PhD dissertation, The George Washington University; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1972. 7304017). * Palmer‐Mehta, Valerie. "Sarah Polk: Ideas of Her Own." in ''A Companion to First Ladies'' (2016): 159–175. * Paul; James C. N. ''Rift in the Democracy.'' (1951). on 1844 election * * Rowe, Christopher. "American society through the prism of the Walker Tariff of 1846." ''Economic Affairs'' 40.2 (2020): 180–197. * Ruiz, Ramon, ed. ''The Mexican War: Was it Manifest Destiny?'' (1963) excerpts from primary and secondary sources. * Schoenbeck, Henry Fred. "The economic views of James K. Polk as expressed in the course of his political career" (PhD dissertation, The University of Nebraska – Lincoln; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1951. DP13923). * Sellers, Charles. ''James K. Polk, Jacksonian, 1795–1843'' (1957

vol 1 online

and ''James K. Polk, Continentalist, 1843–1846''. (1966

vol 2 online

long scholarly biography * pp 195–290 * Smith, Justin Harvey. ''The War with Mexico, Vol 1.'' (2 vol 1919)

full text online

** Smith, Justin Harvey. ''The War with Mexico, Vol. 2''. (2 vol 1919)

full text online

Pulitzer prize; still a major standard source, * Weinberg, Albert. ''Manifest Destiny: A Study of Nationalist Expansionism in American History'' (1935

online

* Williams, Frank J. “James K. Polk.” in ''The Presidents and the Constitution: A Living History'', edited by Ken Gormley, NYU Press, 2016, pp. 149–58

online

* Winders, Richard Bruce. ''Mr. Polk's army: the American military experience in the Mexican war'' (Texas A&M University Press, 2001).

online

online vol 13, August 1847 to March 1848

* Polk, James K. ''The Diary of James K. Polk During His Presidency, 1845–1849'' edited by Milo Milton Quaife, 4 vols. 1910. Abridged version by Allan Nevins. 1929/

James K. Polk: A Resource Guide

from the

James K. Polk's Personal Correspondence

Shapell Manuscript Foundation

Extensive essay on James K. Polk and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady

from the

Inaugural Address of James K. Polk

from The Avalon Project at the

Biography of James K. Polk

from the official

President James K. Polk State Historic Site, Pineville, North Carolina

from a

"Life Portrait of James K. Polk"

from

James K. Polk

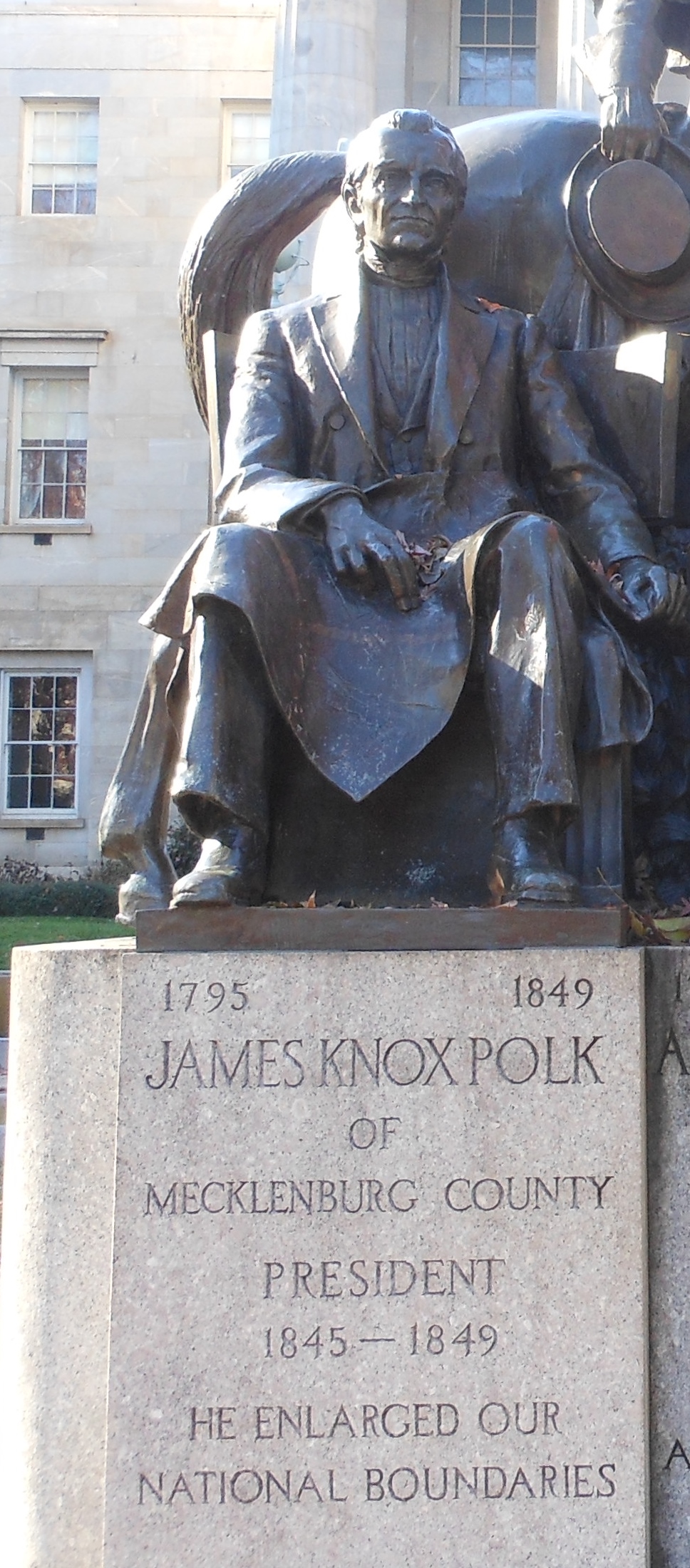

James Knox Polk (; November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. A protégé of Andrew Jackson and a member of the Democratic Party, he was an advocate of Jacksonian democracy and ...

served as the 11th president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

from March 4, 1845, to March 4, 1849. A Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (Cyprus) (DCY)

**Democratic Part ...

, Polk assumed office after defeating Whig Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

in the 1844 presidential election. Polk left office after one term, fulfilling a campaign pledge he made in 1844, and he was succeeded by Whig Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military officer and politician who was the 12th president of the United States, serving from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States ...

. A close ally of Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

, Polk's presidency reflected his adherence to the ideals of Jacksonian democracy

Jacksonian democracy, also known as Jacksonianism, was a 19th-century political ideology in the United States that restructured a number of federal institutions. Originating with the seventh U.S. president, Andrew Jackson and his supporters, i ...

and manifest destiny

Manifest destiny was the belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American pioneer, American settlers were destined to expand westward across North America, and that this belief was both obvious ("''m ...

.

Polk is regarded as the last effective pre-Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

president, having met during his four years in office every major domestic and foreign policy goal set during his campaign and the transition to his administration. Polk's presidency was particularly influential in U.S. foreign policy, and his presidency saw the last major expansions of the Contiguous United States

The contiguous United States, also known as the U.S. mainland, officially referred to as the conterminous United States, consists of the 48 adjoining U.S. states and the District of Columbia of the United States in central North America. The te ...

. When Mexico rejected the U.S. annexation of Texas

The Republic of Texas was annexed into the United States and admitted to the Union as the 28th state on December 29, 1845.

The Republic of Texas declared independence from the Republic of Mexico on March 2, 1836. It applied for annexatio ...

, Polk achieved a sweeping victory in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

, which resulted in the cession by Mexico of nearly the whole of what is now the American Southwest

The Southwestern United States, also known as the American Southwest or simply the Southwest, is a geographic and cultural list of regions of the United States, region of the United States that includes Arizona and New Mexico, along with adjacen ...

. He threatened war with Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

over control of the Oregon Country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long Oregon boundary dispute, dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been demarcat ...

, eventually reaching an agreement in which both nations agreed to partition the region at the 49th parallel.

Polk also accomplished his goals in domestic policy. He ensured a substantial reduction of tariff rates by replacing the "Black Tariff

The Tariff of 1842, or Black Tariff as it became known, was a protectionist tariff schedule adopted in the United States. It reversed the effects of the Compromise Tariff of 1833, which contained a provision that successively lowered the tarif ...

" with the Walker tariff of 1846, which pleased the less-industrialized states of his native Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, Dixieland, or simply the South) is List of regions of the United States, census regions defined by the United States Cens ...

by rendering less expensive both imported and, through competition, domestic goods. Additionally, he built an independent treasury system that lasted until 1913, oversaw the opening of the U.S. Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (USNA, Navy, or Annapolis) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy is the sec ...

and of the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

, the groundbreaking for the Washington Monument

The Washington Monument is an obelisk on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., built to commemorate George Washington, a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father of the United States, victorious commander-in-chief of the Continen ...

, and the issuance of the first United States postage stamp.

Polk did not closely involve himself in the 1848 presidential election, but his actions strongly affected the race. General Zachary Taylor, who had served in the Mexican–American War, won the Whig presidential nomination and defeated Polk's preferred candidate, Democratic Senator Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was a United States Army officer and politician. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He was also the 1 ...

. Scholars have ranked

A ranking is a relationship between a set of items, often recorded in a list, such that, for any two items, the first is either "ranked higher than", "ranked lower than", or "ranked equal to" the second. In mathematics, this is known as a weak ...

Polk favorably for his ability to promote, obtain support for, and achieve all of the major items on his presidential agenda. However, he has also been criticized for leading the country into war against Mexico and for exacerbating sectional divides. Polk has been called the "least known consequential president" of the United States.

1844 election

In the months leading up to the1844 Democratic National Convention

The 1844 Democratic National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held in Baltimore, Maryland from May 27 through 30. The convention nominated former Governor James K. Polk of Tennessee for president and former Senator George M. ...

, former President Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was the eighth president of the United States, serving from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as Attorney General o ...

was widely seen as the front-runner for the Democratic presidential nomination. Polk, who desired to be the party's vice-presidential nominee in the 1844 election,Merry p. 43-44 engaged in a delicate and subtle campaign to become Van Buren's running mate.Merry p. 50-53 The proposed annexation

Annexation, in international law, is the forcible acquisition and assertion of legal title over one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. In current international law, it is generally held t ...

of the Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas (), or simply Texas, was a country in North America that existed for close to 10 years, from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846. Texas shared borders with Centralist Republic of Mexico, the Republic of the Rio Grande, an ...

by President John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president of the United States, vice president in 1841. He was elected ...

upended the presidential race. Van Buren and the Whig frontrunner, Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

, opposed the annexation and a potential war with Mexico over the disputed territory, Polk and former President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

strongly supported the acquisition of the independent country. Disappointed by Van Buren's position, Jackson threw his support behind Polk for the nomination.

When the Democratic National Convention began on May 27, 1844, the key question was whether the convention would adopt a rule requiring the presidential nominee to receive the vote of two-thirds of the delegates. With the strong support of the Southern states, the two thirds-rule was passed by the convention, effectively ending the possibility of Van Buren's nomination due to the strong opposition he faced from an unyielding and significant minority of delegates.Merry, pg. 87–88 Van Buren won a majority on the first presidential ballot, but failed to win the necessary super-majority, and support for Van Buren faded on subsequent ballots. On the eighth presidential ballot, Polk won 44 of the 266 delegates, as support for all candidates other than Polk, Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was a United States Army officer and politician. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He was also the 1 ...

, and Van Buren dissipated.Merry, pg. 92–94 Following the eighth ballot, several delegates rose to speak in support of Polk's candidacy. Van Buren, then realizing that he had no chance of ever winning the 1844 presidential nomination, threw his support behind Polk, who won on the next ballot. In doing so, Polk became the first "dark horse

A dark horse is a previously lesser-known person, team or thing that emerges to prominence in a situation, especially in a competition involving multiple rivals, that is unlikely to succeed but has a fighting chance, unlike the underdog who is exp ...

" candidate ever to win a major U.S. political party's presidential nomination. After Senator Silas Wright

Silas Wright Jr. (May 24, 1795 – August 27, 1847) was an American attorney and Democratic politician. A member of the Albany Regency, he served as a member of the United States House of Representatives, New York State Comptroller, United Stat ...

, a close Van Buren ally, declined the vice presidential nomination, the convention nominated former Senator George M. Dallas of Pennsylvania as Polk's running mate.

After learning of his nomination, Polk promised to serve only one term, believing that this would help him win the support of Democratic leaders such as Cass, Wright, John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun (; March 18, 1782March 31, 1850) was an American statesman and political theorist who served as the seventh vice president of the United States from 1825 to 1832. Born in South Carolina, he adamantly defended American s ...

, Thomas Hart Benton, and James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

, all of whom had presidential aspirations.Merry, pp. 103–104 Further, he avoided taking a position on the protectionist

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. ...

Tariff of 1842

The Tariff of 1842, or Black Tariff as it became known, was a protectionist tariff schedule adopted in the United States. It reversed the effects of the Compromise Tariff of 1833, which contained a provision that successively lowered the tariff ...

, but appealed to the key state of Pennsylvania by using rhetoric favorable towards high tariffs.Merry, pg. 99–100 In New York, another key swing state, Polk's campaign was greatly aided by the gubernatorial candidacy of Wright, who managed to unite the factions of the New York Democratic Party.

The abolitionist Liberty party nominated Michigan's James G. Birney, while the

The abolitionist Liberty party nominated Michigan's James G. Birney, while the 1844 Whig National Convention

The 1844 Whig National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held on May 1, 1844, at Universalist Church in Baltimore, Maryland. It nominated the Whig Party's candidates for president and vice president in the 1844 election. The ...

nominated Henry Clay on the first ballot. Notwithstanding that Polk had been Speaker of the House of Representatives and governor of Tennessee, Whig speeches and editorials scorned Polk, mocking him with the chant "Who is James K. Polk?" in reference to Polk's relative obscurity compared to both Van Buren or Clay.Merry, pg. 96–97 The Whigs blanketed the nation with hundreds of thousands of anti-Polk tracts, accusing him of being a puppet of the " slaveocracy" and a radical who would destroy the United States over the annexation of Texas. Democrats like Robert Walker recast the issue of Texas annexation, arguing that Texas and as Oregon were rightfully American but had been lost during the Monroe administration. Walker further argued that Texas would provide a market for Northern goods and would allow for the "diffusion" of slavery, which in turn would lead to gradual emancipation. In response, Clay argued that the annexation of Texas would bring war with Mexico and increase sectional tensions.

Ultimately, Polk triumphed in an extremely close election, defeating Clay 170–105 in the Electoral College

An electoral college is a body whose task is to elect a candidate to a particular office. It is mostly used in the political context for a constitutional body that appoints the head of state or government, and sometimes the upper parliament ...

; the flip of just a few thousand voters in New York would have given the election to Clay. Birney won several thousand anti-annexation votes in New York, and his presence in the race may have cost Clay the election.

Inauguration

Polk was inaugurated as the nation's 11th president on March 4, 1845, in a ceremony held on the East Portico of the

Polk was inaugurated as the nation's 11th president on March 4, 1845, in a ceremony held on the East Portico of the United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called the Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the Seat of government, seat of the United States Congress, the United States Congress, legislative branch of the Federal government of the United States, federal g ...

. Chief Justice Roger Taney

Roger Brooke Taney ( ; March 17, 1777 – October 12, 1864) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the fifth chief justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 1864. Taney delivered the majority opin ...

administered the oath of office

An oath of office is an oath or affirmation a person takes before assuming the duties of an office, usually a position in government or within a religious body, although such oaths are sometimes required of officers of other organizations. Suc ...

. Polk's inauguration was the first presidential inauguration to be reported by telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

and shown in a newspaper illustration (in ''The Illustrated London News

''The Illustrated London News'', founded by Herbert Ingram and first published on Saturday 14 May 1842, was the world's first illustrated weekly news magazine. The magazine was published weekly for most of its existence, switched to a less freq ...

'').

Polk's inaugural address, written with the help of Amos Kendall

Amos Kendall (August 16, 1789 – November 12, 1869) was an American lawyer, journalist and politician. He rose to prominence as editor-in-chief of the ''Argus of Western America'', an influential newspaper in Frankfort, Kentucky, Frankfort, the ...

, was a message of hope and confidence. At 4,476 words, it is the second longest inaugural address, behind only that of William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was the ninth president of the United States, serving from March 4 to April 4, 1841, the shortest presidency in U.S. history. He was also the first U.S. president to die in office, causin ...

. In his inaugural address, Polk touched on the Jacksonian principles that had guided his political career and Democratic Party positions that would guide his administration. A major theme of the speech was the nation's westward expansion

The United States of America was formed after thirteen British colonies in North America declared independence from the British Empire on July 4, 1776. In the Lee Resolution, passed by the Second Continental Congress two days prior, the colon ...

. He detailed how important the addition of Texas to the Union was, and noted that Americans were moving into lands even further west (California and Oregon). He declared:

At the time that Polk became president, the nation's population had doubled every twenty years since the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

and had reached demographic parity with Britain.Merry, pg. 132–133 Polk's tenure saw continued technological improvements, including the expansion of railroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport using wheeled vehicles running in railway track, tracks, which usually consist of two parallel steel railway track, rails. Rail transport is one of the two primary means of ...

s and increased use of the telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

. These improved communications and growing demographics increasingly made the United States into a strong military power, and also stoked expansionism

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military Imperialism, empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established p ...

.

Administration

Cabinet

Polk governed with the help of his cabinet, in which he placed great importance. The cabinet regularly met twice a week, and Polk and his six cabinet members discussed all major issues during these meetings.Merry, pg. 134–135 Despite his reliance on his cabinet, Polk involved himself in the minutiae of the various departments, especially regarding the military.Merry, pg. 269–270

In selecting a new cabinet, Polk generally heeded Jackson's advice to avoid individuals who were themselves interested in the presidency, though he chose to nominate Buchanan for the crucial and prestigious position of Secretary of State.Merry, pg. 114–117Seigenthaler, pp. 104–106 Polk respected Buchanan's opinion and Buchanan played an important role in Polk's presidency, but the two often clashed over foreign policy and appointments. Polk frequently considered dismissing Buchanan from office, as he suspected Buchanan of placing his own presidential aspirations above service to Polk, but Buchanan always managed to convince Polk of his loyalty.Merry, pg. 439–440

Polk put together an initial slate of cabinet choices that met with the approval of Andrew Jackson, who Polk met with in January 1845 for the last time, as Jackson died in June 1845.

Polk governed with the help of his cabinet, in which he placed great importance. The cabinet regularly met twice a week, and Polk and his six cabinet members discussed all major issues during these meetings.Merry, pg. 134–135 Despite his reliance on his cabinet, Polk involved himself in the minutiae of the various departments, especially regarding the military.Merry, pg. 269–270

In selecting a new cabinet, Polk generally heeded Jackson's advice to avoid individuals who were themselves interested in the presidency, though he chose to nominate Buchanan for the crucial and prestigious position of Secretary of State.Merry, pg. 114–117Seigenthaler, pp. 104–106 Polk respected Buchanan's opinion and Buchanan played an important role in Polk's presidency, but the two often clashed over foreign policy and appointments. Polk frequently considered dismissing Buchanan from office, as he suspected Buchanan of placing his own presidential aspirations above service to Polk, but Buchanan always managed to convince Polk of his loyalty.Merry, pg. 439–440

Polk put together an initial slate of cabinet choices that met with the approval of Andrew Jackson, who Polk met with in January 1845 for the last time, as Jackson died in June 1845. Cave Johnson

Cave Johnson (January 11, 1793 – November 23, 1866) was an American politician who served the state of Tennessee as a Democratic congressman in the United States House of Representatives. Johnson was the 12th United States Postmaster Gener ...

, a close friend and ally of Polk, would be nominated for the position of Postmaster General. Though Polk was personally close with the incumbent Navy Secretary, John Y. Mason

John Young Mason (April 18, 1799October 3, 1859) was an attorney, planter, judge and politician from Virginia. Mason served in the U.S. House of Representatives after serving in both houses of the Virginia General Assembly, then became the Unit ...

, he replaced him after Jackson insisted that none of Tyler's cabinet be retained. In his place, Polk selected George Bancroft

George Bancroft (October 3, 1800 – January 17, 1891) was an American historian, statesman and Democratic Party (United States), Democratic politician who was prominent in promoting secondary education both in his home state of Massachusetts ...

, a historian who had played a crucial role in Polk's nomination. Polk also selected Senator Robert J. Walker

Robert James Walker (July 19, 1801November 11, 1869) was an American lawyer, economist and politician. An active member of the Democratic Party, he served as a member of the U.S. Senate from Mississippi from 1835 until 1845, as Secretary of t ...

of Mississippi as Attorney General.Merry, pg. 117–119

However, after news of Buchanan's selection for State was leaked, Vice President Dallas (an in-state rival of Buchanan) and a slew of Southerners insisted that Walker receive the higher position at Treasury.Merry, pg. 124–126 Polk instead chose to nominate Bancroft as a compromise at Treasury while nominating Mason as Attorney General and a New Yorker, William L. Marcy

William Learned Marcy (December 12, 1786July 4, 1857) was an American lawyer, politician, and judge who served as U.S. Senator, the eleventh Governor of New York, U.S. Secretary of War and the twenty-first U.S. Secretary of State. In the la ...

, as Secretary of War. Polk had intended the Marcy appointment to mollify Van Buren, but Van Buren was outraged at the move, in part due to Marcy's affiliation with the rival " Hunker" faction. Polk then further enraged Van Buren by finally choosing Walker for Treasury; Bancroft was shifted back to Navy Secretary.Merry, pg. 127

After the outbreak of the Mexican-American War, Polk shook up his cabinet, sending Bancroft to Great Britain as an ambassador, shifting Mason to his old position of Navy Secretary, and successfully nominating Nathan Clifford

Nathan Clifford (August 18, 1803 – July 25, 1881) was an American statesman, diplomat and jurist.

Clifford is one of the few people who have held a constitutional office in each of the three branches of the U.S. federal government. He ...

as Attorney General.Merry, pg. 282

Goals

According to a story told decades later by George Bancroft, Polk set four clearly defined goals for his administration:Merry, pg. 131–132 * Reestablish theIndependent Treasury System

The Independent Treasury was the system for managing the money supply of the United States federal government through the U.S. Treasury and its sub-treasuries, independently of the national banking and financial systems. It was created on August 6, ...

.

* Reduce tariffs

A tariff or import tax is a duty imposed by a national government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods or raw materials and is ...

.

* Acquire some or all of Oregon Country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long Oregon boundary dispute, dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been demarcat ...

.

* Acquire California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

and New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

from Mexico.

While his domestic aims represented continuity with past Democratic policies, successful completion of Polk's foreign policy goals would represent the first major American territorial gains since the Adams–Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty () of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Spanish Cession, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty,Weeks, p. 168. was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to ...

of 1819.

Judicial appointments

The 1844 death of Justice Henry Baldwin had created a vacancy on the Supreme Court, and Tyler's failure to fill the seat left a Supreme Court seat open when Polk took office. Polk's attempt to fill Baldwin's seat became embroiled in Pennsylvania politics and the efforts of factional leaders to secure the lucrative post of Collector of Customs for the Port of Philadelphia. As Polk sought to find his way through the minefield of Pennsylvania politics, a second position on the high court became vacant with the death, in September 1845, of JusticeJoseph Story

Joseph Story (September18, 1779September10, 1845) was an American lawyer, jurist, and politician who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1812 to 1845. He is most remembered for his opinions in ''Martin ...

; his replacement was expected to come from his native New England. Because Story's death had occurred while the Senate was not in session, Polk was able to make a recess appointment

In the United States, a recess appointment is an appointment by the President of the United States, president of a Officer of the United States, federal official when the United States Senate, U.S. Senate is in Recess (motion), recess. Under the ...

, choosing Senator Levi Woodbury

Levi Woodbury (December 22, 1789September 4, 1851) was an American attorney, jurist, and Democratic politician from New Hampshire. During a four-decade career in public office, Woodbury served as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the U ...

of New Hampshire, and when the Senate reconvened in December 1845, the Senate confirmed the appointment of Woodbury. Polk's initial nominee for Baldwin's seat, George W. Woodward, was rejected by the Senate in January 1846, in large part due to the opposition of Buchanan and Pennsylvania Senator Simon Cameron

Simon Cameron (March 8, 1799June 26, 1889) was an American businessman and politician who represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate and served as United States Secretary of War under President Abraham Lincoln at the start of the Ameri ...

.

Polk eventually offered Buchanan the open seat, but Buchanan, after some indecision, turned it down. Polk subsequently nominated Robert Cooper Grier

Robert Cooper Grier (March 5, 1794 – September 25, 1870) was an American jurist who served on the Supreme Court of the United States.

A Jacksonian Democrat from Pennsylvania who served from 1846 to 1870, Grier weighed in on some of the most i ...

, who won confirmation. Justice Woodbury served until his death in 1851, but Grier served until 1870. In the slavery case of ''Dred Scott v. Sandford

''Dred Scott v. Sandford'', 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that held the U.S. Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent, and therefore they ...

'' (1857), Grier wrote a concurring opinion stating that slaves were property and could not sue.

Polk appointed eight other federal judges, one to the United States Circuit Court of the District of Columbia

The United States Circuit Court of the District of Columbia (in case citations, C.C.D.C.) was a United States federal court which existed from 1801 to 1863. The court was created by the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801.

History

The D.C. ...

, and seven to various United States district court

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the United States federal judiciary, U.S. federal judiciary. There is one district court for each United States federal judicial district, federal judicial district. Each district cov ...

s.

Foreign affairs

Polk's main achievements in foreign policy were: * Oregon Boundary: Polk successfully resolved the long-standing dispute between the United States and Britain over the Oregon Country (modern-day Oregon, Washington, and parts of Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana). Through diplomatic negotiations, Washington and London agreed to the 49th parallel as the boundary line, securing American control over present-day Oregon and Washington. * Annexation of Texas: President Polk was a strong advocate for the annexation of Texas, which had been independent from Mexico in 1836. He successfully pushed for the admission of Texas as a state in 1845, expanding the territory of the United States and fulfilling a main goal ofmanifest destiny

Manifest destiny was the belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American pioneer, American settlers were destined to expand westward across North America, and that this belief was both obvious ("''m ...

.

* Victory against Mexico. The U.S. military, under Polk's direction, achieved a series of military victories without major defeats. This led to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. The Treaty secured vast territories for the United States, including California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Colorado and Wyoming. Acquisition of Texas and California were Polk's original goals.

*Reduction of Tariffs: Polk successfully advocated for the low tariffs. The Walker Tariff of 1846, named after Polk's Treasury Secretary Robert J. Walker, significantly reduced import duties. This policy change aimed to lower prices paid by American consumers.

The United States added more territory during the one term administration of President Polk than during any other president's administration.

Annexation of Texas

Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas (), or simply Texas, was a country in North America that existed for close to 10 years, from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846. Texas shared borders with Centralist Republic of Mexico, the Republic of the Rio Grande, an ...

had gained independence from Mexico following the Texas Revolution

The Texas Revolution (October 2, 1835 – April 21, 1836) was a rebellion of colonists from the United States and Tejanos (Hispanic Texans) against the Centralist Republic of Mexico, centralist government of Mexico in the Mexican state of ...

of 1836, and, partly because Texas had been settled by a large number of Americans, there was a strong sentiment in both Texas and the United States for the annexation of Texas by the United States. During the transition period after the 1844 election, President Tyler sought to complete the annexation of Texas. Lacking a two-thirds majority, an earlier treaty that would annex the republic was defeated in the Senate. Tyler proposed that Congress accomplish annexation through a joint resolution.Merry, pg. 120–124 Due to disagreements regarding the extension of slavery, Senator Benton of Missouri and Secretary of State Calhoun disagreed on the best way to annex Texas, and Polk became involved in negotiations to break the impasse. With Polk's help, the annexation resolution narrowly cleared the Senate.

In a surprise move two days before Polk's inauguration, Tyler extended to Texas a formal offer of annexation.Merry, pg. 127–128 Polk's first major decision in office was whether to recall Tyler's emissary to Texas, who bore an offer of annexation based on that act of Congress.Merry, pg. 136–137 Though it was within Polk's power to recall the messenger, he chose to allow the emissary to continue, with the hope that Texas would accept the offer. Polk also retained the United States Ambassador to Texas

The United States recognized the Republic of Texas, created by a new constitution on March 2, 1836, as a new independent nation and commissioned its first representative, Alcee La Branche as the chargé d'affaires in 1837. The U.S. never sent a ...

, Andrew Jackson Donelson

Andrew Jackson Donelson (August 25, 1799 – June 26, 1871) was an American diplomat and politician. He served in various positions as a Democrat and was the Know Nothing nominee for US vice president in 1856.

After the death of his father, Done ...

, who sought to convince the Texan leaders to accept annexation under the terms proposed by the Tyler administration.Merry, pg. 148–151 Though public sentiment in Texas favored annexation, some Texas leaders disliked the strict terms for annexation, which offered little leeway for negotiation and gave public lands to the federal government. Nonetheless, in July 1845, a convention in Austin, Texas

Austin ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Texas. It is the county seat and most populous city of Travis County, Texas, Travis County, with portions extending into Hays County, Texas, Hays and W ...

ratified the annexation of Texas. In December 1845, Polk signed a resolution annexing Texas, and Texas became the 28th state in the union. The annexation of Texas would lead to increased tensions with Mexico, which had never recognized Texan independence.

Partition of Oregon Country

Background

Since the signing of the

Since the signing of the Treaty of 1818

The Convention respecting fisheries, boundary and the restoration of slaves, also known as the London Convention, Anglo-American Convention of 1818, Convention of 1818, or simply the Treaty of 1818, is an international treaty signed in 1818 betw ...

, the largely unsettled Oregon Country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long Oregon boundary dispute, dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been demarcat ...

had been under the joint occupation and control of Great Britain and the United States. Previous U.S. administrations had offered to divide the region along the 49th parallel, which was not acceptable to Britain, as it had commercial interests along the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook language, Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin language, Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river headwater ...

.Merry, pp. 168–169 Britain's preferred partition, which would have awarded Puget Sound

Puget Sound ( ; ) is a complex estuary, estuarine system of interconnected Marine habitat, marine waterways and basins located on the northwest coast of the U.S. state of Washington (state), Washington. As a part of the Salish Sea, the sound ...

and all lands north of the Columbia River to Britain, was unacceptable to Polk. Edward Everett

Edward Everett (April 11, 1794 – January 15, 1865) was an American politician, Unitarian pastor, educator, diplomat, and orator from Massachusetts. Everett, as a Whig, served as U.S. representative, U.S. senator, the 15th governor of Mas ...

, President Tyler's minister to Britain, had informally proposed dividing the territory at the 49th parallel with the strategic Vancouver Island

Vancouver Island is an island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean and part of the Canadian province of British Columbia. The island is in length, in width at its widest point, and in total area, while are of land. The island is the largest ...

granted to the British. However, when the new British minister Richard Pakenham

Sir Richard Pakenham PC (19 May 1797 – 28 October 1868) was a British diplomat of Anglo-Irish background. He served as British Ambassador to the United States from 1843 until 1847, during which time he unsuccessfully worked to prevent t ...

arrived in Washington in 1844, he found that many Americans desired the entire territory. Oregon had not been a major issue in the 1844 election, but the recent heavy influx of settlers to the Oregon Country and the rising spirit of expansionism in the United States made a treaty with Britain more urgent.

Partition

Though both the British and the Americans sought an acceptable compromise regarding Oregon Country, each also saw the territory as an important geopolitical asset that would play a large part in determining the dominant power in North America. In his inaugural address, Polk announced that he viewed the American claim to the land as "clear and unquestionable", provoking threats of war from British leaders should Polk attempt to take control of the entire territory.Merry, pp. 170–171 Polk had refrained in his address from asserting a claim to the entire territory, which extended north to 54 degrees, 40 minutes north latitude, although the Democratic Party platform called for such a claim. Despite Polk's hawkish rhetoric, he viewed war with the British as unwise, and Polk and Buchanan opened up negotiations with the British.Merry, pp. 173–175 Like his predecessors, Polk again proposed a division along the 49th parallel, which was immediately rejected by Pakenham. Secretary of State Buchanan was wary of a two-front war with Mexico and Britain, but Polk was willing to risk war with both countries in pursuit of a favorable settlement.Merry, pp. 190–191 In his December 1845 annual message to Congress, Polk requested approval of giving Britain a one-year notice (as required in the Treaty of 1818) of his intention to terminate the joint occupancy of Oregon. In that message, he quoted from the Monroe Doctrine to denote America's intention of keeping European powers out, the first significant use of it since its origin in 1823. After much debate, Congress eventually passed the resolution in April 1846, attaching its hope that the dispute would be settled amicably. When the British Foreign Secretary,Lord Aberdeen

George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen (28 January 178414 December 1860), styled Lord Haddo from 1791 to 1801, was a British statesman, diplomat and landowner, successively a Tory, Conservative and Peelite politician and specialist in fo ...

, learned of the proposal rejected by Pakenham, Aberdeen asked the United States to re-open negotiations, but Polk was unwilling to do so unless a proposal was made by the British.Merry, pp. 196–197

With Britain moving towards free trade with the repeal of the Corn Laws, good trade relations with the United States were more important to Aberdeen than a distant territory. In February 1846, Polk allowed Buchanan to inform Louis McLane

Louis McLane (May 28, 1786 – October 7, 1857) was an American lawyer and politician from Wilmington, Delaware, Wilmington, in New Castle County, Delaware, and Baltimore, Baltimore, Maryland. He was a veteran of the War of 1812, a member of t ...

, the American ambassador to Britain, that Polk's administration would look favorably on a British proposal based around a division at the 49th parallel. In June 1846, Pakenham presented an offer to the Polk administration, calling for a boundary line at the 49th parallel, with the exception that Britain would retain all of Vancouver Island

Vancouver Island is an island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean and part of the Canadian province of British Columbia. The island is in length, in width at its widest point, and in total area, while are of land. The island is the largest ...

, and British subjects would be granted limited navigation rights on the Columbia River until 1859. Polk and most of his cabinet were prepared to accept the proposal, but Buchanan, in a reversal, urged that the United States seek control of all of the Oregon Territory.

After winning the reluctant approval of Buchanan, Polk submitted the full treaty to the Senate for ratification. The Senate ratified the Oregon Treaty

The Oregon Treaty was a treaty between the United Kingdom and the United States that was signed on June 15, 1846, in Washington, D.C. The treaty brought an end to the Oregon boundary dispute by settling competing American and British claims to ...

in a 41–14 vote, with opposition coming from those who sought the full territory. Polk's willingness to risk war with Britain had frightened many, but his tough negotiation tactics may have gained the United States concessions from the British (particularly regarding the Columbia River) that a more conciliatory president might not have won.Merry, pp. 266–267

Mexican–American War

Background

The United States had been the first country to recognize Mexico's independence following theMexican War of Independence

The Mexican War of Independence (, 16 September 1810 – 27 September 1821) was an armed conflict and political process resulting in Mexico's independence from the Spanish Empire. It was not a single, coherent event, but local and regional ...

, but relations between the two countries began to sour in the 1830s.Merry, pg. 184–186 In the 1830s and 1840s, the United States, like France and Britain, sought a reparations treaty with Mexico for various acts committed by Mexican citizens and authorities, including the seizure of American ships. Though the United States and Mexico had agreed to a joint board to settle the various claims prior to Polk's presidency, many Americans accused the Mexican government of acting in bad faith in settling the claims. For its part, Mexico believed that the United States sought to acquire Mexican territory, and believed that many Americans filed specious or exaggerated claims. The already-troubled Mexico–United States relations

Mexico and the United States have a complex history, with war in the 1840s and the subsequent American acquisition of more than 50% of former Mexican territory, including Texas, Arizona, California, and New Mexico. Pressure from Washington was on ...

were further inflamed by the possibility of the annexation of Texas, as Mexico still viewed Texas as an integral part of their republic.Merry, pg. 176–177 Additionally, Texas laid claim to all land north of the Rio Grande River

The Rio Grande ( or ) in the United States or the Río Bravo (del Norte) in Mexico (), also known as Tó Ba'áadi in Navajo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the Southwestern United States and in northern Me ...

, while Mexico argued that the more northern Nueces River

The Nueces River ( ; , ) is a river in the U.S. state of Texas, about long. It drains a region in central and southern Texas southeastward into the Gulf of Mexico. It is the southernmost major river in Texas northeast of the Rio Grande. ''Nu ...

was the proper Texan border.Merry, pg. 187 Though the United States had a population more than twice as numerous and an economy thirteen times greater than that of Mexico, Mexico was not prepared to give up its claim to Texas, even if it meant war.Merry, pg. 180

The Mexican province of Alta California

Alta California (, ), also known as Nueva California () among other names, was a province of New Spain formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but was made a separat ...

enjoyed a large degree of autonomy, and the central government neglected its defenses; a report from a French diplomat stated that "whatever nation chooses to send there a man-of-war

In Royal Navy jargon, a man-of-war (also man-o'-war, or simply man) was a powerful warship or frigate of the 16th to the 19th century, that was frequently used in Europe. Although the term never acquired a specific meaning, it was usually rese ...

and 200 men" could conquer California. Polk placed great value in the acquisition of California, which represented new lands to settle as well as a potential gateway to trade in Asia. He feared that the British or another European power would eventually establish control over California if it remained in Mexican hands. In late 1845, Polk sent diplomat John Slidell

John Slidell (1793July 9, 1871) was an American politician, lawyer, slaveholder, and businessman. Database at A native of New York, Slidell moved to Louisiana as a young man. He was a member of the Louisiana House of Representatives, U.S. House ...

to Mexico to win Mexico's acceptance of the Rio Grande border. Slidell was further authorized to purchase California for $20 million and New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

for $5 million. Polk also sent Lieutenant Archibald H. Gillespie

Major Archibald H. Gillespie (October 10, 1812 – August 16, 1873) was an officer in the United States Marine Corps during the Mexican–American War.

Biography

Born in New York City, Gillespie was commissioned in the Marine Corps in 1832. He ...

to California with orders to foment a pro-American rebellion that could be used to justify annexation of the territory.Merry, pg. 295–296

Outbreak of war

Following the Texan ratification of annexation in 1845, both Mexicans and Americans saw war as a likely possibility. Polk began preparations for a potential war, sending an army led by GeneralZachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military officer and politician who was the 12th president of the United States, serving from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States ...

into Texas.Merry, pg. 188–189 Taylor and Commodore David Conner of the U.S. Navy were both ordered to avoid provoking a war, but were authorized to respond to any Mexican breach of peace. Though Mexican President José Joaquín de Herrera

José Joaquín Antonio Florencio de Herrera y Ricardos (February 23, 1792 – February 10, 1854) was a Mexican statesman who served as president of Mexico three times (1844, 1844–1845 and 1848–1851), and as a general in the Mexican Army d ...

was open to negotiations, Slidell's ambassadorial credentials were refused by a Mexican council of government.Merry, pg. 209–210 In December 1845, Herrera's government collapsed largely due to his willingness to negotiate with the United States; the possibility of the sale of large portions of Mexico aroused anger among both Mexican elites and the broader populace.Merry, pg. 218–219

As successful negotiations with the unstable Mexican government appeared unlikely, Secretary of War Marcy ordered General Taylor to advance to the Rio Grande River. Polk began preparations to support a potential new government led by the exiled Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (21 February 1794 – 21 June 1876),Callcott, Wilfred H., "Santa Anna, Antonio Lopez De,''Handbook of Texas Online'' Retrieved 18 April 2017. often known as Santa Anna, wa ...

with the hope that Santa Anna would sell parts of California. Polk had been advised by Alejandro Atocha, an associate of Santa Anna, that only the threat of war would allow the Mexican government the leeway to sell parts of Mexico.Merry, pg. 238–240 In March 1846, Slidell finally left Mexico after the government refused his demand to be formally received.Merry, pg. 232–233 Slidell returned to Washington in May 1846, and gave his opinion that negotiations with the Mexican government were unlikely to be successful. Polk regarded the treatment of his diplomat as an insult and an "ample cause of war", and he prepared to ask Congress for a declaration of war.

Meanwhile, in late March 1846, General Taylor reached the Rio Grande, and his army camped across the river from Matamoros, Tamaulipas

Matamoros, officially known as Heroica Matamoros, is a city in the northeastern Mexican state of Tamaulipas, and the municipal seat of the homonymous municipality. It is on the southern bank of the Rio Grande, directly across the border from Bro ...

. In April, after Mexican general Pedro de Ampudia

Pedro Nolasco Martín José María de la Candelaria Francisco Javier Ampudia y Grimarest (January 30, 1805 – August 7, 1868) was born in Havana, Cuba, and served Mexico as a Northern army officer for most of his life. At various points he wa ...

demanded that Taylor return to the Nueces River, Taylor began a blockade of Matamoros.Merry, pg. 240–242 A skirmish on the northern side of the Rio Grande ended in the death or capture of dozens of American soldiers, and became known as the Thornton Affair

The Thornton Affair, also known as the Thornton Skirmish, Thornton's Defeat, or Rancho Carricitos, was a battle in 1846 between the military forces of the United States and Mexico west upriver from Zachary Taylor's camp along the Rio Grande ...

. While the administration was in the process of asking for a declaration of war, Polk received word of the outbreak of hostilities on the Rio Grande. In a message to Congress, Polk explained his decision to send Taylor to the Rio Grande, and stated that Mexico had invaded American territory by crossing the river.Merry, pg. 244–245 Polk contended that a state of war already existed, and he asked Congress to grant him the power to bring the war to a close. Polk's message was crafted to present the war as a just and necessary defense of the country against a neighbor that had long troubled the United States.Lee, pgs. 517–518 In his message, Polk noted that Slidell had gone to Mexico to negotiate a recognition of the Texas annexation, but did not mention that he also sought the purchase of California.

Some Whigs, such as Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

, challenged Polk's version of events. One Whig congressman declared "the river Nueces is the true western boundary of Texas. It is our own president who began this war. He has been carrying it on for months." Nonetheless, the House overwhelmingly approved of a resolution authorizing the president to call up fifty thousand volunteers.Merry, pg. 245–246 In the Senate, war opponents led by Calhoun also questioned Polk's version of events, but the House resolution passed the Senate in a 40–2 vote, marking the beginning of the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

.Merry, pg. 246–247 Many congressmen who were skeptical about the wisdom of going to war with Mexico feared that publicly opposing the war would cost them politically.

Early war

In May 1846, Taylor led U.S. forces in the inconclusiveBattle of Palo Alto

The Battle of Palo Alto () was the first major battle of the Mexican–American War and was fought on May 8, 1846, on disputed ground five miles (8 km) from the modern-day city of Brownsville, Texas. A force of some 3,700 Mexico, Mexican t ...

, the first major battle of the war. The next day, Taylor led the army to victory in the Battle of Resaca de la Palma

The Battle of Resaca de la Palma was one of the early engagements of the Mexican–American War, where the United States Army under General Zachary Taylor engaged the retreating forces of the Mexican ''Ejército del Norte'' ("Army of the Nor ...

, eliminating the possibility of a Mexican incursion into the United States. Taylor's force moved south towards Monterrey

Monterrey (, , abbreviated as MtY) is the capital and largest city of the northeastern Mexican state of Nuevo León. It is the ninth-largest city and the second largest metropolitan area, after Greater Mexico City. Located at the foothills of th ...

, which served as the capital of the province of Nuevo León

Nuevo León, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Nuevo León, is a Administrative divisions of Mexico, state in northeastern Mexico. The state borders the Mexican states of Tamaulipas, Coahuila, Zacatecas, and San Luis Potosí, San Luis ...

. In the September 1846 Battle of Monterrey

In the Battle of Monterrey (September 21–24, 1846) during the Mexican–American War, General Pedro de Ampudia and the Mexican Army of the North was defeated by the Army of Occupation, a force of United States Regulars, Volunteers, an ...

, Taylor defeated a Mexican force led by Ampudia, but allowed Ampudia's forces to withdraw, much to Polk's consternation.Merry, pg. 311–313

Meanwhile, Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as Commanding General of the United States Army from 1841 to 1861, and was a veteran of the War of 1812, American Indian Wars, Mexica ...

, the army's lone major general at the outbreak of the war, was offered the position of top commander in the war. Polk, War Secretary Marcy, and Scott agreed on a strategy in which the US would capture northern Mexico and then pursue a favorable peace settlement.Merry, pg. 256–257 However, Polk and Scott experienced mutual distrust from the beginning of their relationship, in part due to Scott's Whig affiliation and former rivalry with Andrew Jackson.Merry, pg. 253–254 Additionally, Polk sought to ensure that both Whigs and Democrats would serve in important positions in the war, and was offended when Scott suggested otherwise; Scott also angered Polk by opposing Polk's effort to increase the number of generals.Merry, pg. 258–259 Having been alienated from Scott, Polk ordered Scott to remain in Washington, leaving Taylor in command of Mexican operations.Merry, pg. 259–260 Polk also ordered Commodore Conner to allow Santa Anna to return to Mexico from his exile, and sent an army expedition led by Stephen W. Kearny towards Santa Fe.

While Taylor fought the Mexican army in east, U.S. forces took control of California and New Mexico. Army Captain John C. Frémont

Major general (United States), Major-General John Charles Frémont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was a United States Army officer, explorer, and politician. He was a United States senator from California and was the first History of the Repub ...

led settlers in Northern California in an attack on the Mexican garrison in Sonoma, beginning the Bear Flag Revolt

The California Republic, or Bear Flag Republic, was an List of historical unrecognized states#Americas, unrecognized breakaway state from Second Federal Republic of Mexico, Mexico, that existed from June 14, 1846 to July 9, 1846. It milita ...

.Merry, pg. 302–304 In August 1846, American forces under Kearny captured Santa Fe, capital of the province of New Mexico.Merry, pg. 293–294 He captured Santa Fe without firing a shot, as the Mexican Governor, Manuel Armijo

Manuel Armijo ( – 1853) was a New Mexican soldier and statesman who served three times as governor of New Mexico between 1827 and 1846. He was instrumental in putting down the Revolt of 1837; he led the military forces that captured the invad ...

, fled from the province.Merry, pg. 298–299 After establishing a provisional government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, a transitional government or provisional leadership, is a temporary government formed to manage a period of transition, often following state collapse, revoluti ...

in New Mexico, Kearny took a force west to aid in the conquest of California. After Kearny's departure, Mexicans and Puebloans

The Pueblo peoples are Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans in the Southwestern United States who share common agricultural, material, and religious practices. Among the currently inhabited Pueblos, Taos Pueblo, Taos, San Il ...

rebelled against the provisional government in the Taos Revolt

The Taos Revolt was a popular insurrection in January 1847 by Hispano and Pueblo allies against the United States' occupation of present-day northern New Mexico during the Mexican–American War. Provisional governor Charles Bent and severa ...

, but U.S. forces crushed the uprising. At roughly the same time that Kearny captured Santa Fe, Commodore Robert F. Stockton

Robert Field Stockton (August 20, 1795 – October 7, 1866) was a United States Navy commodore, notable in the capture of California during the Mexican–American War. He was a naval innovator and an early advocate for a propeller-driven, steam- ...

landed in Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

and proclaimed the capture of California. Californio

Californios (singular Californio) are Californians of Spaniards, Spanish descent, especially those descended from settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries before California was annexed by the United States. California's Spanish language in C ...

s rose up in rebellion against U.S. occupation, but Stockton and Kearny suppressed the revolt with a victory in the Battle of La Mesa

The Battle of La Mesa (also known as the Battle of Los Angeles) was the final battle of the California Campaign during the Mexican–American War, occurring on January 9, 1847, in present-day Vernon, California, the day after the Battle of Ri ...

. After the battle, Kearny and Frémont became embroiled in a dispute over the establishment of a government in California. The controversy between Frémont and Kearny led to a break between Polk and the powerful Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton, who was the father-in-law of Frémont.Merry, pg. 423–424

Growing domestic resistance

Whig opposition to the war grew after 1845, while some Democrats lost their initial enthusiasm. In August 1846, Polk asked Congress to appropriate $2 million in hopes of using that money as a down payment for the purchase of California in a treaty with Mexico.Merry, pg. 283–285 Polk's request ignited opposition to the war, as Polk had never before made public his desire to annex parts of Mexico (aside from lands claimed by Texas). A freshman Democratic Congressman,David Wilmot David Wilmot may refer to:

* David Wilmot (politician)

* David Wilmot (actor)

David Wilmot is an Ireland, Irish actor best known for his roles in ''Michael Collins (film), Michael Collins'' (1996), ''I Went Down'' (1997), ''Intermission (fil ...

of Pennsylvania, offered an amendment known as the Wilmot Proviso

The Wilmot Proviso was an unsuccessful 1846 proposal in the United States Congress to ban slavery in territory acquired from Mexico in the Mexican–American War. The conflict over the Wilmot Proviso was one of the major events leading to the ...

that would ban slavery in any newly acquired lands.Merry, pg. 286–289 The appropriations bill, including the Wilmot Proviso, passed the House with the support Northern Whigs and Northern Democrats, breaking the normal pattern of partisan division in congressional votes. Wilmot himself held anti-slavery views, but many pro-slavery Northern Democrats voted for the bill out of anger at Polk's perceived bias towards the South. The partition of Oregon, the debate over the tariff, and Van Buren's antagonism towards Polk all contributed to Northern anger. The appropriations bill, including the ban on slavery, was defeated in the Senate, but the Wilmot Proviso injected the slavery debate into national politics.

Polk's Democrats would pay a price for the resistance to the war and the growing issue of slavery, as Democrats lost control of the House in the 1846 elections. However, in early 1847, Polk was successful in passing a bill raising further regiments, and he also finally won approval for the money he wanted to use for the purchase of California.Merry, pg. 343–349

Late war

Santa Anna returned to Mexico City in September 1846, declaring that he would fight against the Americans.Merry, pg. 309–310 With the duplicity of Santa Anna now clear, and with the Mexicans declining his peace offers, Polk ordered an American landing inVeracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entit ...

, the most important Mexican port on the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

. As a march from Monterrey to Mexico City was implausible due to rough terrain, Polk had decided that a force would land in Veracruz and then march on Mexico City. Taylor was ordered to remain near Monterrey, while Polk reluctantly chose Winfield Scott to lead the attack on Veracruz.Merry, pg. 318-20 Though Polk continued to distrust Scott, Marcy and the other cabinet members prevailed on Polk to select the army's most senior general for the command.Seigenthaler, pg. 139–140

In March 1847, Polk learned that Taylor had ignored orders and had continued to march south, capturing the northern Mexican town of Saltillo

Saltillo () is the capital and largest city of the northeastern Mexican state of Coahuila and is also the municipal seat of the municipality of the same name. Mexico City, Monterrey, and Saltillo are all connected by a major railroad and high ...

.Merry, pg. 352–355 Taylor's army had repulsed a larger Mexican force, led by Santa Anna, in the February 1847 Battle of Buena Vista

The Battle of Buena Vista (February 22–23, 1847), known as the Battle of La Angostura in Mexico, and sometimes as Battle of Buena Vista/La Angostura, was a battle of the Mexican–American War. It was fought between U.S. forces, largely vol ...

. Taylor won acclaim for the result of the battle, but the theater remained inconclusive. Rather than pursuing Santa Anna's forces, Taylor withdrew back to Monterrey. Meanwhile, Scott landed in Veracruz and quickly won control of the city.Merry, pg. 358–359 Following the capture of Veracruz, Polk dispatched Nicholas Trist

Nicholas Philip Trist (June 2, 1800 – February 11, 1874) was an American lawyer, diplomat, planter, and businessman. Even though he had been dismissed by President James K. Polk as the negotiator with the Mexican government, he negotiated the T ...

, Buchanan's chief clerk, to negotiate a peace treaty with Mexican leaders. Trist was ordered to seek the cession of Alta California, New Mexico, and Baja California

Baja California, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Baja California, is a state in Mexico. It is the northwesternmost of the 32 federal entities of Mexico. Before becoming a state in 1952, the area was known as the North Territory of B ...