Polish Messianism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of philosophy in Poland parallels the evolution of

The formal history of

The formal history of  From the beginning of the fifteenth century, Polish philosophy, centered at Kraków University, pursued a normal course. It no longer harbored exceptional thinkers such as Vitello, but it did feature representatives of all wings of mature

From the beginning of the fifteenth century, Polish philosophy, centered at Kraków University, pursued a normal course. It no longer harbored exceptional thinkers such as Vitello, but it did feature representatives of all wings of mature

The spirit of

The spirit of  Generally speaking, though, Poland remained Aristotelian. Sebastian Petrycy of

Generally speaking, though, Poland remained Aristotelian. Sebastian Petrycy of  A star among the pleiade of progressive

A star among the pleiade of progressive  The Polish

The Polish

This empiricist and positivist Enlightenment philosophy produced several outstanding Polish thinkers. Although active in the reign of Stanisław August Poniatowski, they published their chief works only after the loss of the

This empiricist and positivist Enlightenment philosophy produced several outstanding Polish thinkers. Although active in the reign of Stanisław August Poniatowski, they published their chief works only after the loss of the

For a generation, between the age of the French Enlightenment and that of the Polish national

For a generation, between the age of the French Enlightenment and that of the Polish national

File:Andrej Tavianski. Андрэй Тавянскі (V. Vańkovič, 1820-40).jpg, Andrzej Towiański

File:Jozef Maria Hoëné-Wronski--Laurent-Charles Maréchal mg 9487.jpg, Józef Maria Hoene-Wroński

File:Jozef Goluchowski 1851-1862 (1045790) (cropped).jpg, Józef Gołuchowski

File:Adam Mickiewicz według dagerotypu paryskiego z 1842 roku.jpg, Adam Mickiewicz

File:Juliusz Słowacki.PNG, Juliusz Słowacki

File:Portrait of Józef Kremer by Maksymilian Fajans. Cropped..jpg, Józef Kremer

File:Zygmunt Krasinski (78590058) (cropped).jpg, Zygmunt Krasiński

File:Karol Libelt.jpg, Karol Libelt

File:HadziewiczRafal-PortretMichalaWiszniewskiego.jpg, Michał Wiszniewski

File:Bronisław Trętowski (!) portrait by Regulski.jpg, Bronisław Trentowski

File:August Cieszkowski.PNG, August Cieszkowski

File:AleksanderSwietochowski.jpg, Aleksander Świętochowski

File:AdolfDygasinski.jpg, Adolf Dygasiński

File:Julian Ochorowicz (cropped).jpg,

File:Wincenty Lutosławski (cropped).jpg, Wincenty Lutosławski

File:Kazimierz Twardowski 1933.jpg, Kazimierz Twardowski

File:Edward Abramowski (1868-1918).jpgEdward Abramowski

File:Leon Petrazycki ii.jpg, Leon Petrażycki

File:Brzozowski Stanisław.jpg, Stanisław Brzozowski (writer), Stanisław Brzozowski

File:Witkacy Roman Ingarden 1937.jpg,

10 Polish Philosophers that Changed the Way We Think

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20160312013857/http://segr-did2.fmag.unict.it/~polphil/PolHome.html Polish Philosophy Page] {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Philosophy In Poland History of philosophy, Poland History of Poland by topic, Philosophy Polish Enlightenment Polish philosophy, History Polish positivists

philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

in general.

Overview

Polish philosophy drew upon the broader currents of European philosophy, and in turn contributed to their growth. Some of the most momentous Polish contributions came, in the thirteenth century, from the Scholastic philosopher and scientistVitello

Vitello (; ; – 1280/1314) was a Polish friar, theologian, natural philosopher and an important figure in the history of philosophy in Poland.

Name

Vitello's name varies with some sources. In earlier publications he was quoted as Erazmus Ciol ...

, and, in the sixteenth century, from the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

.

Subsequently, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

partook in the intellectual ferment of the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

, which for the multi-ethnic Commonwealth ended not long after the 1772-1795 partitions and political annihilation that would last for the next 123 years, until the collapse of the three partitioning empires in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

.

The period of Messianism

Messianism is the belief in the advent of a messiah who acts as the savior of a group of people. Some religions also have messianism-related concepts. Religions with a messiah concept include Hinduism (Kalki), Judaism ( Mashiach), Christianity ( ...

, between the November 1830 and January 1863 Uprisings, reflected European Romantic and Idealist

Idealism in philosophy, also known as philosophical realism or metaphysical idealism, is the set of metaphysical perspectives asserting that, most fundamentally, reality is equivalent to mind, spirit, or consciousness; that reality is entir ...

trends, as well as a Polish yearning for political resurrection

Resurrection or anastasis is the concept of coming back to life after death. Reincarnation is a similar process hypothesized by other religions involving the same person or deity returning to another body. The disappearance of a body is anothe ...

. It was a period of maximalist metaphysical systems.

The collapse of the January 1863 Uprising prompted an agonizing reappraisal of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

's situation. Poles gave up their earlier practice of "measuring their resources by their aspirations" and buckled down to hard work and study. " Positivist", wrote the novelist Bolesław Prus

Aleksander Głowacki (20 August 1847 – 19 May 1912), better known by his pen name Bolesław Prus (), was a Polish journalist, novelist, a leading figure in the history of Polish literature and philosophy, and a distinctive voice in world ...

' friend, Julian Ochorowicz

Julian Leopold Ochorowicz (Polish pronunciation: ; outside Poland also known as Julien Ochorowitz; Radzymin, 23 February 1850 – 1 May 1917, Warsaw) was a Polish philosopher, psychologist, inventor (precursor of radio and television), poet, pub ...

, was "anyone who bases assertions on verifiable evidence; who does not express himself categorically about doubtful things, and does not speak at all about those that are inaccessible."

The twentieth century brought a new quickening to Polish philosophy. There was growing interest in western philosophical currents. Rigorously-trained Polish philosophers made substantial contributions to specialized fields—to psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

, the history of philosophy

The history of philosophy is the systematic study of the development of philosophical thought. It focuses on philosophy as rational inquiry based on argumentation, but some theorists also include myth, religious traditions, and proverbial lor ...

, the theory of knowledge

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowledg ...

, and especially mathematical logic

Mathematical logic is the study of Logic#Formal logic, formal logic within mathematics. Major subareas include model theory, proof theory, set theory, and recursion theory (also known as computability theory). Research in mathematical logic com ...

. Tatarkiewicz, ''Zarys...'', p. 32. Jan Łukasiewicz

Jan Łukasiewicz (; 21 December 1878 – 13 February 1956) was a Polish logician and philosopher who is best known for Polish notation and Łukasiewicz logic. His work centred on philosophical logic, mathematical logic and history of logi ...

gained world fame with his concept of many-valued logic

Many-valued logic (also multi- or multiple-valued logic) is a propositional calculus in which there are more than two truth values. Traditionally, in Aristotle's Term logic, logical calculus, there were only two possible values (i.e., "true" and ...

and his "Polish notation

Polish notation (PN), also known as normal Polish notation (NPN), Łukasiewicz notation, Warsaw notation, Polish prefix notation, Eastern Notation or simply prefix notation, is a mathematical notation in which Operation (mathematics), operator ...

." Alfred Tarski

Alfred Tarski (; ; born Alfred Teitelbaum;School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews ''School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews''. January 14, 1901 – October 26, 1983) was a Polish-American logician ...

's work in truth theory

Truth or verity is the property of being in accord with fact or reality.Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionarytruth, 2005 In everyday language, it is typically ascribed to things that aim to represent reality or otherwise correspond to it, such as ...

won him world renown.

After World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, for over four decades, world-class Polish philosophers and historians of philosophy such as Władysław Tatarkiewicz

Władysław Tatarkiewicz (; 3 April 1886 – 4 April 1980) was a Polish philosopher, historian of philosophy, historian of art, esthetician, and ethicist.

Early life and education

Tatarkiewicz began his higher education at Warsaw University ...

continued their work, often in the face of adversities occasioned by the dominance of a politically enforced official philosophy. The phenomenologist Roman Ingarden

Roman Witold Ingarden (5 February 1893 – 14 June 1970) was a Polish philosopher who worked in aesthetics, ontology, and phenomenology.

Before World War II, Ingarden published his works mainly in the German language and in books and newspapers ...

did influential work in esthetics and in a Husserl

Edmund Gustav Albrecht Husserl (; 8 April 1859 – 27 April 1938) was an Austrian-German philosopher and mathematician who established the school of phenomenology.

In his early work, he elaborated critiques of historicism and of psychologism in ...

-style metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

; his student Karol Wojtyła

Pope John Paul II (born Karol Józef Wojtyła; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 16 October 1978 until his death in 2005.

In his youth, Wojtyła dabbled in stage acting. H ...

acquired a unique influence on the world stage as Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II (born Karol Józef Wojtyła; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 16 October 1978 until Death and funeral of Pope John Paul II, his death in 2005.

In his you ...

.

Scholasticism

The formal history of

The formal history of philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

in Poland may be said to have begun in the fifteenth century, following the revival of the University of Kraków by King Władysław II Jagiełło

Jogaila (; 1 June 1434), later Władysław II Jagiełło (),Other names include (; ) (see also Names and titles of Władysław II Jagiełło) was Grand Duke of Lithuania beginning in 1377 and starting in 1386, becoming King of Poland as well. ...

in 1400.Tatarkiewicz, ''Zarys...'', p. 5.

The true beginnings of Polish philosophy, however, reach back to the thirteenth century and Vitello

Vitello (; ; – 1280/1314) was a Polish friar, theologian, natural philosopher and an important figure in the history of philosophy in Poland.

Name

Vitello's name varies with some sources. In earlier publications he was quoted as Erazmus Ciol ...

(c. 1230 – c. 1314), a Silesia

Silesia (see names #Etymology, below) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at 8, ...

n born to a Polish mother and a Thuringia

Thuringia (; officially the Free State of Thuringia, ) is one of Germany, Germany's 16 States of Germany, states. With 2.1 million people, it is 12th-largest by population, and with 16,171 square kilometers, it is 11th-largest in area.

Er ...

n settler, a contemporary of Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

who had spent part of his life in Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

at centers of the highest intellectual culture. In addition to being a philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, he was a scientist

A scientist is a person who Scientific method, researches to advance knowledge in an Branches of science, area of the natural sciences.

In classical antiquity, there was no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, philosophers engag ...

who specialized in optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of optical instruments, instruments that use or Photodetector, detect it. Optics usually describes t ...

. His famous treatise, ''Perspectiva'', while drawing on the Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

''Book of Optics

The ''Book of Optics'' (; or ''Perspectiva''; ) is a seven-volume treatise on optics and other fields of study composed by the medieval Arab scholar Ibn al-Haytham, known in the West as Alhazen or Alhacen (965–c. 1040 AD).

The ''Book ...

'' by Alhazen

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham ( Latinized as Alhazen; ; full name ; ) was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the princ ...

, was unique in Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

literature, and in turn helped inspire Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (; or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the Scholastic accolades, scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English polymath, philosopher, scientist, theologian and Franciscans, Franciscan friar who placed co ...

's best work, Part V of his ''Opus maius'', "On Perspectival Science," as well as his supplementary treatise ''On the Multiplication of Vision''. Vitello's ''Perspectiva'' additionally made important contributions to psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

: it held that vision

Vision, Visions, or The Vision may refer to:

Perception Optical perception

* Visual perception, the sense of sight

* Visual system, the physical mechanism of eyesight

* Computer vision, a field dealing with how computers can be made to gain und ...

''per se'' apprehends only color

Color (or colour in English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth English; American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, see spelling differences) is the visual perception based on the electromagnetic spectrum. Though co ...

s and light

Light, visible light, or visible radiation is electromagnetic radiation that can be visual perception, perceived by the human eye. Visible light spans the visible spectrum and is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400– ...

while all else, particularly the distance and size of objects, is established by means of association and unconscious deduction.

Vitello's concept of being

Existence is the state of having being or reality in contrast to nonexistence and nonbeing. Existence is often contrasted with essence: the essence of an entity is its essential features or qualities, which can be understood even if one do ...

was one rare in the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, neither Augustinian as among conservatives nor Aristotelian as among progressives, but Neoplatonist

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

. It was an emanationist concept that held radiation

In physics, radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or a material medium. This includes:

* ''electromagnetic radiation'' consisting of photons, such as radio waves, microwaves, infr ...

to be the prime characteristic of being, and ascribed to radiation the nature of light

Light, visible light, or visible radiation is electromagnetic radiation that can be visual perception, perceived by the human eye. Visible light spans the visible spectrum and is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400– ...

. This "metaphysic of light" inclined Vitello to optical

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultravio ...

research, or perhaps ''vice versa'' his optical studies led to his metaphysic

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of h ...

.

According to the Polish historian of philosophy, Władysław Tatarkiewicz

Władysław Tatarkiewicz (; 3 April 1886 – 4 April 1980) was a Polish philosopher, historian of philosophy, historian of art, esthetician, and ethicist.

Early life and education

Tatarkiewicz began his higher education at Warsaw University ...

, no Polish philosopher since Vitello has enjoyed so eminent a European standing as this thinker who belonged, in a sense, to the prehistory

Prehistory, also called pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the first known use of stone tools by hominins million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use ...

of Polish philosophy.Tatarkiewicz, ''Zarys...'', p. 6.

From the beginning of the fifteenth century, Polish philosophy, centered at Kraków University, pursued a normal course. It no longer harbored exceptional thinkers such as Vitello, but it did feature representatives of all wings of mature

From the beginning of the fifteenth century, Polish philosophy, centered at Kraków University, pursued a normal course. It no longer harbored exceptional thinkers such as Vitello, but it did feature representatives of all wings of mature Scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and Ca ...

, ''via antiqua'' as well as ''via moderna''.

The first of these to reach Kraków was ''via moderna'', then the more widespread movement in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

.Tatarkiewicz, ''Historia filozofii'', vol. 1, p. 311. In physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

, logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

and ethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

, Terminism (Nominalism

In metaphysics, nominalism is the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels. There are two main versions of nominalism. One denies the existence of universals—that which can be inst ...

) prevailed in Kraków, under the influence of the French Scholastic, Jean Buridan

Jean Buridan (; ; Latin: ''Johannes Buridanus''; – ) was an influential 14thcentury French scholastic philosopher.

Buridan taught in the faculty of arts at the University of Paris for his entire career and focused in particular on logic and ...

(died c. 1359), who had been rector of the University of Paris

The University of Paris (), known Metonymy, metonymically as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, from 1150 to 1970, except for 1793–1806 during the French Revolution. Emerging around 1150 as a corporation associated wit ...

and an exponent of views of William of Ockham

William of Ockham or Occam ( ; ; 9/10 April 1347) was an English Franciscan friar, scholastic philosopher, apologist, and theologian, who was born in Ockham, a small village in Surrey. He is considered to be one of the major figures of medie ...

. Buridan had formulated the theory

A theory is a systematic and rational form of abstract thinking about a phenomenon, or the conclusions derived from such thinking. It involves contemplative and logical reasoning, often supported by processes such as observation, experimentation, ...

of "'' impetus''"—the force

In physics, a force is an influence that can cause an Physical object, object to change its velocity unless counterbalanced by other forces. In mechanics, force makes ideas like 'pushing' or 'pulling' mathematically precise. Because the Magnitu ...

that causes a body, once set in motion

In physics, motion is when an object changes its position with respect to a reference point in a given time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed, and frame of reference to an o ...

, to persist in motion—and stated that impetus is proportional to the speed

In kinematics, the speed (commonly referred to as ''v'') of an object is the magnitude of the change of its position over time or the magnitude of the change of its position per unit of time; it is thus a non-negative scalar quantity. Intro ...

of, and amount of matter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic pa ...

comprising, a body: Buridan thus anticipated Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

and Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

. His theory of impetus was momentous in that it also explained the motions of celestial bodies

An astronomical object, celestial object, stellar object or heavenly body is a naturally occurring physical entity, association, or structure that exists within the observable universe. In astronomy, the terms ''object'' and ''body'' are of ...

without resort to the spirits—''"intelligentiae"''—to which the Peripatetics

The Peripatetic school ( ) was a philosophical school founded in 335 BC by Aristotle in the Lyceum in ancient Athens. It was an informal institution whose members conducted philosophical and scientific inquiries. The school fell into decline after ...

(followers of Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

) had ascribed those motions. At Kraków

, officially the Royal Capital City of Kraków, is the List of cities and towns in Poland, second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city has a population of 804,237 ...

, physics was now expounded by (St.) Jan Kanty (1390–1473), who developed this concept of "impetus."

A general trait of the Kraków Scholastics was a provlivity for compromise

To compromise is to make a deal between different parties where each party gives up part of their demand. In arguments, compromise means finding agreement through communication, through a mutual acceptance of terms—often involving variations fr ...

—for reconciling Nominalism

In metaphysics, nominalism is the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels. There are two main versions of nominalism. One denies the existence of universals—that which can be inst ...

with the older tradition. For example, the Nominalist, Benedict Hesse, while in principle accepting the theory of impetus, did not apply it to the heavenly spheres.

In the second half of the fifteenth century, at Kraków, ''via antiqua'' became dominant. Nominalism

In metaphysics, nominalism is the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels. There are two main versions of nominalism. One denies the existence of universals—that which can be inst ...

retreated, and the old Scholasticism triumphed.

In this period, Thomism

Thomism is the philosophical and theological school which arose as a legacy of the work and thought of Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), the Dominican philosopher, theologian, and Doctor of the Church.

In philosophy, Thomas's disputed ques ...

had its chief center at Cologne

Cologne ( ; ; ) is the largest city of the States of Germany, German state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with nearly 1.1 million inhabitants in the city pr ...

, whence it influenced Kraków. Cologne, formerly the home ground of Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus ( 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great, Albert of Swabia, Albert von Bollstadt, or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop, considered one of the great ...

, had preserved Albert's mode of thinking. Thus the Cologne philosophers formed two wings, the Thomist and Albertist, and even Cologne's Thomists showed Neoplatonist

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

traits characteristic of Albert, affirming emanation Emanation may refer to:

*Emanation (chemistry), a dated name for the chemical element radon

*Emanation From Below, a concept in Slavic religion

*Emanation in the Eastern Orthodox Church, a belief found in Neoplatonism

*Emanation of the state, a lega ...

, a hierarchy

A hierarchy (from Ancient Greek, Greek: , from , 'president of sacred rites') is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) that are represented as being "above", "below", or "at the same level as" one another. Hierarchy ...

of being

Existence is the state of having being or reality in contrast to nonexistence and nonbeing. Existence is often contrasted with essence: the essence of an entity is its essential features or qualities, which can be understood even if one do ...

, and a metaphysic

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of h ...

of light

Light, visible light, or visible radiation is electromagnetic radiation that can be visual perception, perceived by the human eye. Visible light spans the visible spectrum and is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400– ...

.

The chief Kraków adherents of the Cologne-style Thomism included Jan of Głogów (c. 1445 – 1507) and Jakub of Gostynin (c. 1454 – 1506). Another, purer teacher of Thomism was Michał Falkener of Wrocław

Wrocław is a city in southwestern Poland, and the capital of the Lower Silesian Voivodeship. It is the largest city and historical capital of the region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the Oder River in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Eu ...

(c. 1450 – 1534).

Almost at the same time, Scotism

Scotism is the philosophical school and theological system named after John Duns Scotus, a 13th-century Scottish philosopher-theologian. The word comes from the name of its originator, whose ''Opus Oxoniense'' was one of the most important ...

appeared in Poland, having been brought from Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

first by Michał Twaróg of Bystrzyków

Michał Twaróg of Bystrzyków (; ) (c. 1450–1520) was a Polish philosopher and theologian of the early 16th century.

Life

Michał Twaróg studied at Paris in 1473–77, during the period when, following the anathematization of the Nominalists ...

(c. 1450 – 1520). Twaróg had studied at Paris in 1473–77, in the period when, following the anathema

The word anathema has two main meanings. One is to describe that something or someone is being hated or avoided. The other refers to a formal excommunication by a Christian denomination, church. These meanings come from the New Testament, where a ...

tization of the Nominalist

In metaphysics, nominalism is the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels. There are two main versions of nominalism. One denies the existence of universals—that which can be inst ...

s (1473), the Scotist school was there enjoying its greatest triumphs. A prominent student of Twaróg's, Jan of Stobnica Jan of Stobnica (ca. 1470 - 1530), was a Polish philosopher, scientist and geographer of the early 16th century.

Life

Jan was born in Stopnica, and was educated at the Jagiellonian University (Kraków Academy), where he taught as professor betwee ...

(c. 1470 – 1519), was already a moderate Scotist who took account of the theories of the Ockhamists, Thomist

Thomism is the philosophical and theological school which arose as a legacy of the work and thought of Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), the Dominican philosopher, theologian, and Doctor of the Church.

In philosophy, Thomas's disputed questions ...

s and Humanists

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" has ...

.Tatarkiewicz, ''Zarys...'', p. 7.

When Nominalism

In metaphysics, nominalism is the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels. There are two main versions of nominalism. One denies the existence of universals—that which can be inst ...

was revived in western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

at the turn of the sixteenth century, particularly thanks to Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples

Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples (; Latinized as Jacobus Faber Stapulensis; c. 1455 – c. 1536) was a French theologian and a leading figure in French humanism. He was a precursor of the Protestant movement in France. The "d'Étaples" was not par ...

(''Faber Stapulensis''), it presently reappeared in Kraków

, officially the Royal Capital City of Kraków, is the List of cities and towns in Poland, second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city has a population of 804,237 ...

and began taking the upper hand there once more over Thomism

Thomism is the philosophical and theological school which arose as a legacy of the work and thought of Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), the Dominican philosopher, theologian, and Doctor of the Church.

In philosophy, Thomas's disputed ques ...

and Scotism

Scotism is the philosophical school and theological system named after John Duns Scotus, a 13th-century Scottish philosopher-theologian. The word comes from the name of its originator, whose ''Opus Oxoniense'' was one of the most important ...

. It was reintroduced particularly by Lefèvre's pupil, Jan Szylling, a native of Kraków who had studied at Paris in the opening years of the sixteenth century. Another follower of Lefèvre's was Grzegorz of Stawiszyn Grzegorz of Stawiszyn (; 1481–1540) was a Polish people, Polish philosopher and theologian. He was Rector (academia), Rector of the Jagiellonian University, University of Kraków in 1538–1540.

Biography

Grzegorz was born in Stawiszyn in 1481. H ...

, a Kraków professor who, beginning in 1510, published the Frenchman's works at Kraków.

Thus Poland had made her appearance as a separate philosophical center only at the turn of the fifteenth century, at a time when the creative period of Scholastic philosophy had already passed. Throughout the fifteenth century, Poland harbored all the currents of Scholasticism. The advent of Humanism

Humanism is a philosophy, philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and Agency (philosophy), agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The me ...

in Poland would find a Scholasticism more vigorous than in other countries. Indeed, Scholasticism would survive the 16th and 17th centuries and even part of the 18th at Kraków

, officially the Royal Capital City of Kraków, is the List of cities and towns in Poland, second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city has a population of 804,237 ...

and Wilno Universities and at numerous Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

, Dominican and Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent Religious institute, religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor bei ...

colleges.

To be sure, in the sixteenth century, with the arrival of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

, Scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and Ca ...

would enter upon a decline; but during the 17th century's Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also sometimes called the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to, and as an alternative to or from similar insights as, the Protestant Reformations at the time. It w ...

, and even into the early 18th century, Scholasticism would again become Poland's chief philosophy.

Renaissance

Humanism

Humanism is a philosophy, philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and Agency (philosophy), agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The me ...

, which had reached Poland by the middle of the fifteenth century, was not very "philosophical." Rather, it lent its stimulus to linguistic

Linguistics is the scientific study of language. The areas of linguistic analysis are syntax (rules governing the structure of sentences), semantics (meaning), Morphology (linguistics), morphology (structure of words), phonetics (speech sounds ...

studies, political

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

thought, and scientific

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

research. But these manifested a philosophical attitude different from that of the previous period.

Empirical

Empirical evidence is evidence obtained through sense experience or experimental procedure. It is of central importance to the sciences and plays a role in various other fields, like epistemology and law.

There is no general agreement on how t ...

natural science

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

had flourished at Kraków

, officially the Royal Capital City of Kraków, is the List of cities and towns in Poland, second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city has a population of 804,237 ...

as early as the fifteenth century, side by side with speculative philosophy. The most perfect product of this blossoming was Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

(1473–1543, ). He was not only a scientist but a philosopher. According to Tatarkiewicz, he may have been the greatest—in any case, the most renowned—philosopher that Poland ever produced. He drew the inspiration for his cardinal discovery from philosophy; he had become acquainted through Marsilio Ficino

Marsilio Ficino (; Latin name: ; 19 October 1433 – 1 October 1499) was an Italian scholar and Catholic priest who was one of the most influential humanist philosophers of the early Italian Renaissance. He was an astrologer, a reviver of Neo ...

with the philosophies of Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

and the Pythagoreans

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek co ...

; and through the writings of the philosophers Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

and Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

he had learned about the ancients who had declared themselves in favor of the Earth's movement.

Copernicus may also have been influenced by Kraków philosophy: during his studies there, Terminist physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

had been taught, with special emphasis on "'' impetus''." His own thinking was guided by philosophical considerations. He arrived at the heliocentric

Heliocentrism (also known as the heliocentric model) is a Superseded theories in science#Astronomy and cosmology, superseded astronomical model in which the Earth and Solar System, planets orbit around the Sun at the center of the universe. His ...

thesis (as he was to write in a youthful treatise) "''ratione postea equidem sensu''": it was not observation

Observation in the natural sciences is an act or instance of noticing or perceiving and the acquisition of information from a primary source. In living beings, observation employs the senses. In science, observation can also involve the percep ...

but the discovery of a logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

al contradiction

In traditional logic, a contradiction involves a proposition conflicting either with itself or established fact. It is often used as a tool to detect disingenuous beliefs and bias. Illustrating a general tendency in applied logic, Aristotle's ...

in Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

's system, that served him as a point of departure that led to the new astronomy. In his dedication to Pope Paul III

Pope Paul III (; ; born Alessandro Farnese; 29 February 1468 – 10 November 1549) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 October 1534 to his death, in November 1549.

He came to the papal throne in an era follo ...

, he submitted his work for judgment by "philosophers."Tatarkiewicz, ''Zarys...'', p. 9.

In its turn, Copernicus' theory transformed man's view of the structure of the universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents. It comprises all of existence, any fundamental interaction, physical process and physical constant, and therefore all forms of matter and energy, and the structures they form, from s ...

, and of the place held in it by the earth and by man, and thus attained a far-reaching philosophical importance.

Copernicus was involved not only in natural science

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

and natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

but also—by his postulation of a quantity theory of money

The quantity theory of money (often abbreviated QTM) is a hypothesis within monetary economics which states that the general price level of goods and services is directly proportional to the amount of money in circulation (i.e., the money supply) ...

and of "Gresham's law

In economics, Gresham's law is a monetary principle stating that "bad money drives out good". For example, if there are two forms of commodity money in circulation, which are accepted by law as having similar face value, the more valuable commo ...

" (in the year, 1519, of Thomas Gresham

Sir Thomas Gresham the Elder (; c. 151921 November 1579) was an English merchant and financier who acted on behalf of King Edward VI (1547–1553) and Edward's half-sisters, queens Mary I (1553–1558) and Elizabeth I (1558–1603). In 1565 Gr ...

's birth)—in the philosophy of man.

In the early sixteenth century, Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

, who had become a model for philosophy in Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, especially in Medicean Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

, was represented in Poland in some ways by Adam of Łowicz, author of ''Conversations about Immortality''.

Generally speaking, though, Poland remained Aristotelian. Sebastian Petrycy of

Generally speaking, though, Poland remained Aristotelian. Sebastian Petrycy of Pilzno

Pilzno is a town in Poland, in Subcarpathian Voivodeship, in Dębica County. It had 4,943 inhabitants as of 2018.

Notable residents

* Karol Irzykowski (1873–1944), writer and literary critic

* Sebastian Petrycy (1554–1626), a Polish ph ...

(1554–1626) laid stress, in the theory of knowledge

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowledg ...

, on experiment

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome occurs whe ...

and induction; and in psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

, on feeling

According to the '' APA Dictionary of Psychology'', a feeling is "a self-contained phenomenal experience"; feelings are "subjective, evaluative, and independent of the sensations, thoughts, or images evoking them". The term ''feeling'' is closel ...

and will

Will may refer to:

Common meanings

* Will and testament, instructions for the disposition of one's property after death

* Will (philosophy), or willpower

* Will (sociology)

* Will, volition (psychology)

* Will, a modal verb - see Shall and will

...

; while in politics

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

he preached democratic ideas. Petrycy's central feature was his linking of philosophical theory with the requirements of practical national life. In 1601–18, a period when translation

Translation is the communication of the semantics, meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The English la ...

s into modern language

A modern language is any human language that is currently in use as a native language. The term is used in language education to distinguish between languages which are used for day-to-day communication (such as French and German) and dead clas ...

s were still rarities, he accomplished Polish translations of Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's practical works. With Petrycy, vernacular

Vernacular is the ordinary, informal, spoken language, spoken form of language, particularly when perceptual dialectology, perceived as having lower social status or less Prestige (sociolinguistics), prestige than standard language, which is mor ...

Polish philosophical terminology

Terminology is a group of specialized words and respective meanings in a particular field, and also the study of such terms and their use; the latter meaning is also known as terminology science. A ''term'' is a word, Compound (linguistics), com ...

began to develop not much later than did the French and German.

Yet another Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

current, the new Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy that flourished in ancient Greece and Rome. The Stoics believed that the universe operated according to reason, ''i.e.'' by a God which is immersed in nature itself. Of all the schools of ancient ...

, was represented in Poland by Jakub Górski (c. 1525 – 1585), author of a famous ''Dialectic'' (1563) and of many works in grammar

In linguistics, grammar is the set of rules for how a natural language is structured, as demonstrated by its speakers or writers. Grammar rules may concern the use of clauses, phrases, and words. The term may also refer to the study of such rul ...

, rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

, theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

and sociology

Sociology is the scientific study of human society that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of Interpersonal ties, social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. The term sociol ...

. He tended toward eclecticism

Eclecticism is a conceptual approach that does not hold rigidly to a single paradigm or set of assumptions, but instead draws upon multiple theories, styles, or ideas to gain complementary insights into a subject, or applies different theories i ...

, attempting to reconcile the Stoics

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy that flourished in ancient Greece and Rome. The Stoics believed that the universe operated according to reason, ''i.e.'' by a God which is immersed in nature itself. Of all the schools of ancient ...

with Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

.Tatarkiewicz, ''Zarys...'', p. 10.

A later, purer representative of Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy that flourished in ancient Greece and Rome. The Stoics believed that the universe operated according to reason, ''i.e.'' by a God which is immersed in nature itself. Of all the schools of ancient ...

in Poland was Adam Burski (c. 1560 – 1611), author of a ''Dialectica Ciceronis'' (1604) boldly proclaiming Stoic sensualism

In epistemology, sensualism is a doctrine whereby sensations and perception are the basic and most important form of true cognition. It may oppose abstract ideas.

This ideogenetic question was long ago put forward in Greek philosophy (Stoicism, ...

and empiricism

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological view which holds that true knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience and empirical evidence. It is one of several competing views within epistemology, along ...

and—before Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...

—urging the use of inductive method.

political

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

philosophers during the Polish Renaissance was Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski (1503–72), who advocated on behalf of equality

Equality generally refers to the fact of being equal, of having the same value.

In specific contexts, equality may refer to:

Society

* Egalitarianism, a trend of thought that favors equality for all people

** Political egalitarianism, in which ...

for all before the law, the accountability of monarch

A monarch () is a head of stateWebster's II New College Dictionary. "Monarch". Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. Life tenure, for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest ...

and government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

to the nation, and social assistance for the weak and disadvantaged. His chief work was ''De Republica emendanda'' (On Reform of the Republic, 1551–54).

Another notable political thinker was Wawrzyniec Grzymała Goślicki (1530–1607), best known in Poland and abroad for his book ''De optimo senatore'' (The Accomplished Senator, 1568). It propounded the view—which for long got the book banned in England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, as subversive of monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, reigns as head of state for the rest of their life, or until abdication. The extent of the authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutio ...

—that a ruler may legitimately govern only with the sufferance of the people.

After the first decades of the 17th century, the war

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or between such organi ...

s, invasion

An invasion is a Offensive (military), military offensive of combatants of one geopolitics, geopolitical Legal entity, entity, usually in large numbers, entering territory (country subdivision), territory controlled by another similar entity, ...

s and internal dissensions that beset the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

, brought a decline in philosophy. If in the ensuing period there was independent philosophical thought, it was among the religious dissenter

A dissenter (from the Latin , 'to disagree') is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc. Dissent may include political opposition to decrees, ideas or doctrines and it may include opposition to those things or the fiat of ...

s, particularly the Polish Arians

Arianism (, ) is a Christological doctrine which rejects the traditional notion of the Trinity and considers Jesus to be a creation of God, and therefore distinct from God. It is named after its major proponent, Arius (). It is considered h ...

,Tatarkiewicz, ''Zarys...'', p. 11. also known variously as Antitrinitarian

Nontrinitarianism is a form of Christianity that rejects the orthodox Christian theology of the Trinity—the belief that God is three distinct hypostases or persons who are coeternal, coequal, and indivisibly united in one being, or essence ...

s, Socinian

Socinianism ( ) is a Nontrinitarian Christian belief system developed and co-founded during the Protestant Reformation by the Italian Renaissance humanists and theologians Lelio Sozzini and Fausto Sozzini, uncle and nephew, respectively.

I ...

s, and Polish Brethren—forerunners of the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

and American Socinians, Unitarians and Deist

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin term '' deus'', meaning "god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge and asserts that empirical reason and observation ...

s who were to figure prominently in the intellectual and political currents of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

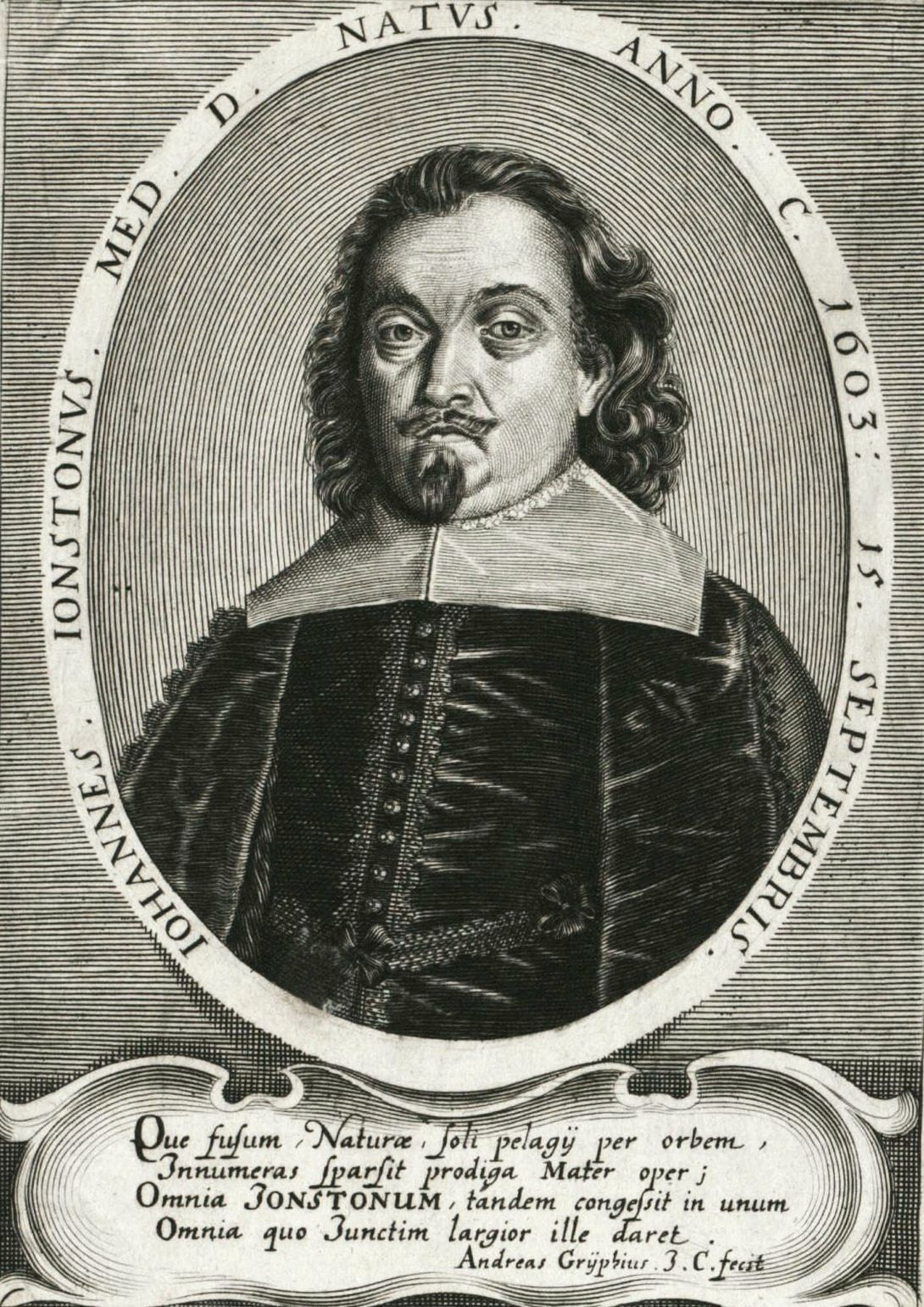

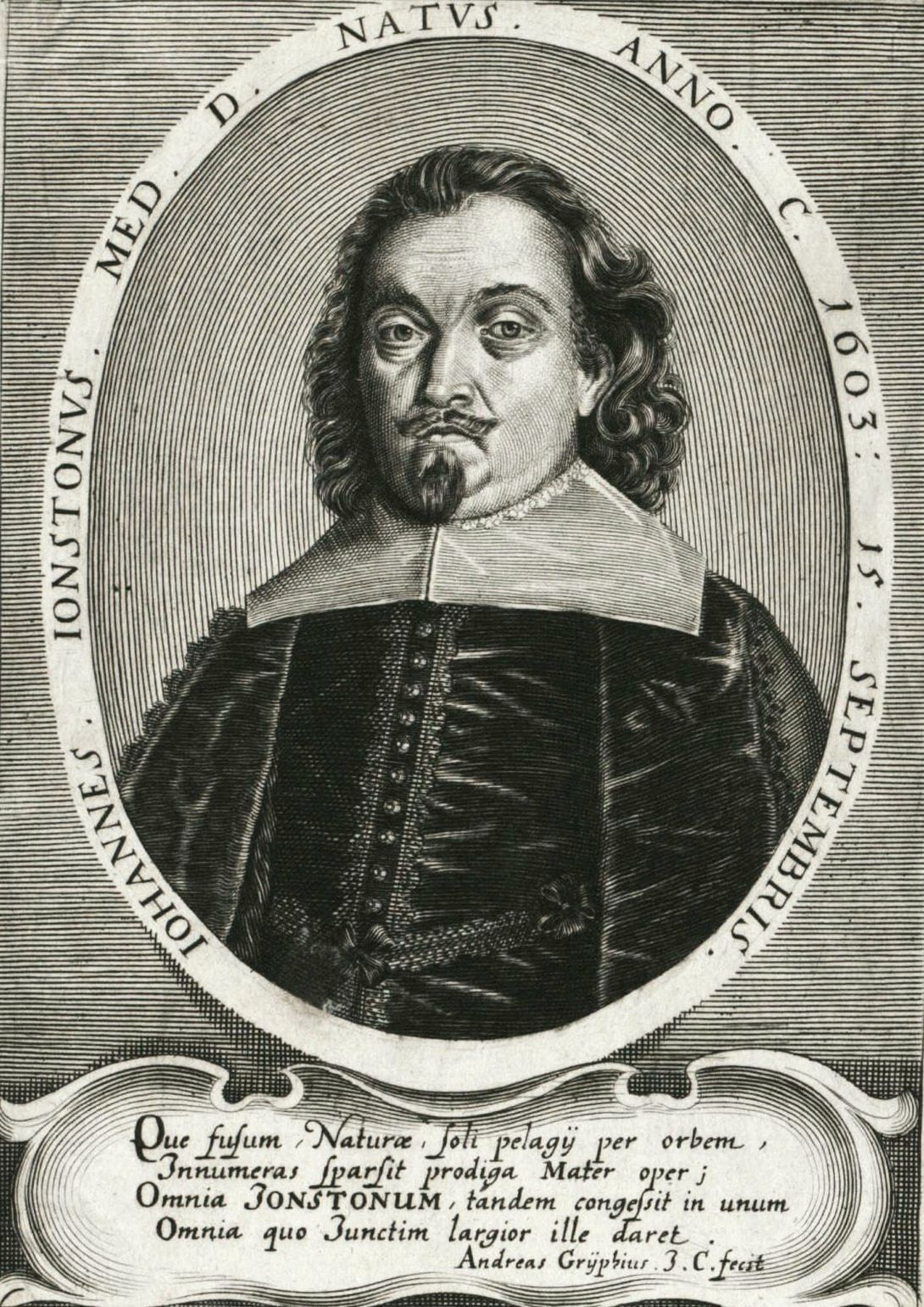

The Polish

The Polish dissenter

A dissenter (from the Latin , 'to disagree') is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc. Dissent may include political opposition to decrees, ideas or doctrines and it may include opposition to those things or the fiat of ...

s created an original ethical

Ethics is the philosophical study of moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches include normative ethics, applied e ...

theory radically condemning evil and violence

Violence is characterized as the use of physical force by humans to cause harm to other living beings, or property, such as pain, injury, disablement, death, damage and destruction. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines violence a ...

. Centers of intellectual life such as that at Leszno

Leszno (, , ) is a historic city in western Poland, seat of Leszno County within the Greater Poland Voivodeship. It is the seventh-largest city in the province with an estimated population of 62,200, as of 2021.

Leszno is a former residential cit ...

hosted notable thinkers such as the Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus

*Czech (surnam ...

pedagogue

Pedagogy (), most commonly understood as the approach to teaching, is the theory and practice of learning, and how this process influences, and is influenced by, the social, political, and psychological development of learners. Pedagogy, taken ...

, Jan Amos Komensky (Comenius), and the Pole, Jan Jonston

John Jonston or Johnston (; or or ; 15 September 1603– ) was a Polish scholar and physician, descended from Scottish nobility and closely associated with the Polish magnate Leszczyński family.

Life

Jonston was born in Szamotuły, the s ...

. Jonston was tutor and physician to the Leszczyński

The House of Leszczyński ( , ; plural: Leszczyńscy, feminine form: Leszczyńska) was a prominent Polish noble family. They were magnates in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and later became the royal family of Poland.

History

The Leszczy� ...

family, a devotee of Bacon and experimental knowledge, and author of ''Naturae constantia'', published in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , ; ; ) is the capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, largest city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It has a population of 933,680 in June 2024 within the city proper, 1,457,018 in the City Re ...

in 1632, whose geometrical

Geometry (; ) is a branch of mathematics concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. Geometry is, along with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. A mathematician w ...

method and naturalistic, almost pantheistic

Pantheism can refer to a number of Philosophy, philosophical and Religion, religious beliefs, such as the belief that the universe is God, or panentheism, the belief in a non-corporeal divine intelligence or God out of which the universe arise ...

concept of the world may have influenced Benedict Spinoza.

The Leszczyński

The House of Leszczyński ( , ; plural: Leszczyńscy, feminine form: Leszczyńska) was a prominent Polish noble family. They were magnates in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and later became the royal family of Poland.

History

The Leszczy� ...

family itself would produce an 18th-century Polish-Lithuanian king, Stanisław Leszczyński

Stanisław I Leszczyński (Stanisław Bogusław; 20 October 1677 – 23 February 1766), also Anglicized and Latinized as Stanislaus I, was twice King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, and at various times Prince of Deux-Ponts, Duk ...

(1677–1766; reigned in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

1704–11 and again 1733–36), "''le philosophe bienfaisant''" ("the beneficent philosopher")—in fact, an independent thinker whose views on culture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

were in advance of Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Republic of Geneva, Genevan philosopher (''philosophes, philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment through ...

's, and who was the first to introduce into Polish intellectual life on a large scale the French influences that were later to become so strong.

In 1689, in an exceptional miscarriage of justice, a Polish ex-Jesuit philosopher, Kazimierz Łyszczyński

Kazimierz Łyszczyński (; 4 March 1634 – 30 March 1689), also known in English as Casimir Liszinski, was a nobleman, philosopher, and soldier in the ranks of the Sapieha family, who was accused, tried, and executed for atheism in 1689.

For ...

, author of a manuscript treatise, ''De non existentia Dei'' (On the Non-existence of God), was accused of atheism by a priest who was his debtor, was convicted, and was executed in most brutal fashion.

Enlightenment

After a decline of a century and a half, in the mid-18th century, Polish philosophy began to revive. The hub of this movement wasWarsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

. While Poland's capital then had no institution of higher learning, neither were those of Kraków

, officially the Royal Capital City of Kraków, is the List of cities and towns in Poland, second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city has a population of 804,237 ...

, Zamość

Zamość (; ; ) is a historical city in southeastern Poland. It is situated in the southern part of Lublin Voivodeship, about from Lublin, from Warsaw. In 2021, the population of Zamość was 62,021.

Zamość was founded in 1580 by Jan Zamoyski ...

or Wilno

Vilnius ( , ) is the capital of and List of cities in Lithuania#Cities, largest city in Lithuania and the List of cities in the Baltic states by population, most-populous city in the Baltic states. The city's estimated January 2025 population w ...

any longer agencies of progress. The initial impetus for the revival came from religious thinkers: from members of the Piarist and other teaching orders. A leading patron of the new ideas was Bishop

A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of Episcopal polity, authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of di ...

Andrzej Stanisław Załuski.

Scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and Ca ...

, which until then had dominated Polish philosophy, was followed by the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

. Initially the major influence was Christian Wolff (philosopher), Christian Wolff and, indirectly, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

's Royal elections in Poland, elected king, August III the Saxon, and the relations between Poland and her neighbor, Saxony, heightened the Germany, German Sphere of influence, influence. Wolff's doctrine was brought to Warsaw in 1740 by the Theatine, Portalupi; from 1743, its chief Polish champion was Wawrzyniec Mitzler de Kolof (1711–78), court physician to August III.

Under the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

's last king, Stanisław August Poniatowski (reigned 1764–95), the Polish Enlightenment was radicalized and came under French influence. The philosophical foundation of the movement ceased to be the Rationalist doctrine of Wolff and became the Sensationalism, Sensualism of Étienne Bonnot de Condillac, Condillac. This spirit pervaded Poland's Commission of National Education, which completed the reforms begun by the Piarist priest, Stanisław Konarski. The commission's members were in touch with the French Encyclopedists and Freethought, freethinkers, with Jean le Rond d'Alembert, d'Alembert and Condorcet, Étienne Bonnot de Condillac, Condillac and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Rousseau. The commission abolished school instruction in theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

, even in philosophy.

This empiricist and positivist Enlightenment philosophy produced several outstanding Polish thinkers. Although active in the reign of Stanisław August Poniatowski, they published their chief works only after the loss of the

This empiricist and positivist Enlightenment philosophy produced several outstanding Polish thinkers. Although active in the reign of Stanisław August Poniatowski, they published their chief works only after the loss of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

's independence in 1795. The most important of these figures were Jan Śniadecki, Stanisław Staszic and Hugo Kołłątaj.

Another adherent of this empirical Enlightenment philosophy was the minister of education under the Duchy of Warsaw and under the Congress Poland established by the Congress of Vienna, Stanisław Kostka Potocki (1755–1821). In some places, as at Krzemieniec and its Lyceum in southeastern Poland, this philosophy was to survive well into the nineteenth century. Although a belated philosophy from a western perspective, it was at the same time the philosophy of the future. This was the period between Jean le Rond d'Alembert, d'Alembert and Auguste Comte, Comte; and even as this variety of positivism was temporarily fading in the West, it was carrying on in Poland.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, as Immanuel Kant's fame was spreading over the rest of Europe, in Poland the Enlightenment philosophy was still in full flower. Kantism found here a hostile soil. Even before Kant had been understood, he was condemned by the most respected writers of the time: by Jan Śniadecki, Stanisław Staszic, Staszic, Hugo Kołłątaj, Kołłątaj, Tadeusz Czacki, later by Anioł Dowgird (1776–1835). Jan Śniadecki warned against this "fanatical, dark and apocalyptic mind," and wrote: "To revise John Locke, Locke and Étienne Bonnot de Condillac, Condillac, to desire ''a priori'' knowledge of things that human nature can grasp only by their consequences, is a lamentable aberration of mind."

Jan Śniadecki's younger brother, however, Jędrzej Śniadecki, was the first respected Polish scholar to declare (1799) for Kant. And in applying Kantian ideas to the natural sciences, he did something new that would not be undertaken until much later by Johannes Peter Müller, Johannes Müller, Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz and other famous scientists of the nineteenth century.

Another Polish proponent of Kantism was Józef Kalasanty Szaniawski (1764–1843), who had been a student of Kant's at Königsberg. But, having accepted the fundamental points of the critical theory of knowledge, he still hesitated between Kant's metaphysical agnosticism and the new metaphysics of Idealism. Thus this one man introduced to Poland both the antimetaphysical Kant and the post-Kantian metaphysics.

In time, Kant's foremost Polish sympathizer would be Feliks Jaroński (1777–1827), who lectured at Kraków in 1809–18. Still, his Kantian sympathies were only partial and this half-heartedness was typical of Polish Kantism generally. In Poland there was no actual Kantian period.

metaphysic

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of h ...

, the Scottish philosophy of Scottish School of Common Sense, common sense became the dominant outlook in Poland. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Scottish School of Common Sense held sway in most European countries—in Britain till mid-century, and nearly as long in France. But in Poland, from the first, the Scottish philosophy fused with Kantism, in this regard anticipating the West.

The Kantian and Scottish ideas were united in typical fashion by Jędrzej Śniadecki (1768–1838). The younger brother of Jan Śniadecki, Jędrzej was an illustrious scientist, biologist and physician, and the more creative mind of the two. He had been educated at the universities of Kraków

, officially the Royal Capital City of Kraków, is the List of cities and towns in Poland, second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city has a population of 804,237 ...

, Padua and Edinburgh and was from 1796 a professor at Wilno, where he held a chair of chemistry and pharmacy. He was a foe of metaphysics