Pocahontas (video Game) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pocahontas (, ; born Amonute, also known as Matoaka and Rebecca Rolfe; 1596 – March 1617) was a Native American woman belonging to the

''True Relation''

, p. 93. In a 1616 letter, Smith again described her as she was in 1608, but this time as "a child of twelve or thirteen years of age".Smith. Pocahontas was the daughter of

"Cooking in Early Virginia Indian Society"Encyclopedia Virginia

. Retrieved February 27, 2011. In his account, Strachey describes Pocahontas as a child visiting the fort at Jamestown and playing with the young boys; she would "get the boys forth with her into the marketplace and make them wheel, falling on their hands, turning up their heels upwards, whom she would follow and wheel so herself, naked as she was, all the fort over".Strachey, ''Historie'', p. 65

Historian William Stith claimed that "her real name, it seems, was originally Matoax, which the Native Americans carefully concealed from the English and changed it to Pocahontas, out of a superstitious fear, lest they, by the knowledge of her true name, should be enabled to do her some hurt." According to

"Pocahontas (d. 1617)"Encyclopedia Virginia

. Retrieved February 24, 2011. In his ''A Map of Virginia'', John Smith explained how matrilineal inheritance worked among the Powhatans:

pp. 114, 174. but not all writers are convinced, some suggesting the absence of certain corroborating evidence.Price, pp. 243–244 Early histories did establish that Pocahontas befriended Smith and the colonists. She often went to the settlement and played games with the boys there. When the colonists were starving, "every once in four or five days, Pocahontas with her attendants brought mithso much provision that saved many of their lives that else for all this had starved with hunger." As the colonists expanded their settlement, the Powhatans felt that their lands were threatened, and conflicts arose again. In late 1609, an injury from a

"Pocahontas (d. 1617)"Encyclopedia Virginia

. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

With Spelman's help translating, Argall pressured Iopassus to assist in Pocahontas' capture by promising an alliance with the colonists against the Powhatans. Iopassus, with the help of his wives, tricked Pocahontas into boarding Argall's ship, ''

During her stay at Henricus, Pocahontas met

During her stay at Henricus, Pocahontas met

One goal of the London Company was to convert Native Americans to Christianity, and they saw an opportunity to promote further investment with the conversion of Pocahontas and her marriage to Rolfe, all of which also helped end the First Anglo-Powhatan War. The company decided to bring Pocahontas to England as a symbol of the tamed

One goal of the London Company was to convert Native Americans to Christianity, and they saw an opportunity to promote further investment with the conversion of Pocahontas and her marriage to Rolfe, all of which also helped end the First Anglo-Powhatan War. The company decided to bring Pocahontas to England as a symbol of the tamed

File:00OPocahontas.jpg, Pocahontas commemorative postage stamp of 1907

File:Pocahontas, daughter of Powhatan, and wife of John Rolfe, photo takes at Jamestown, Virginia.jpg, Statue in

After her death, increasingly fanciful and romanticized representations were produced about Pocahontas, in which she and Smith are frequently portrayed as romantically involved. Contemporaneous sources substantiate claims of their friendship but not romance. The first claim of their romantic involvement was in John Davis' ''Travels in the United States of America'' (1803).

Rayna Green has discussed the similar fetishization that Native and Asian women experience. Both groups are viewed as "exotic" and "submissive", which aids their dehumanization. Also, Green touches on how Native women had to either "keep their exotic distance or die," which is associated with the widespread image of Pocahontas trying to sacrifice her life for John Smith.

Cornel Pewewardy writes, "In Pocahontas, Indian characters such as Grandmother Willow, Meeko, and Flit belong to the

After her death, increasingly fanciful and romanticized representations were produced about Pocahontas, in which she and Smith are frequently portrayed as romantically involved. Contemporaneous sources substantiate claims of their friendship but not romance. The first claim of their romantic involvement was in John Davis' ''Travels in the United States of America'' (1803).

Rayna Green has discussed the similar fetishization that Native and Asian women experience. Both groups are viewed as "exotic" and "submissive", which aids their dehumanization. Also, Green touches on how Native women had to either "keep their exotic distance or die," which is associated with the widespread image of Pocahontas trying to sacrifice her life for John Smith.

Cornel Pewewardy writes, "In Pocahontas, Indian characters such as Grandmother Willow, Meeko, and Flit belong to the

Pocahontas: Schauspiel mit Gesang, in fünf Akten (A Play with Songs, in five Acts)

' by Johann Wilhelm Rose (1784) *''Captain Smith and the Princess Pocahontas'' (1806) *

The first settlers of Virginia : an historical novel

' New York : Printed for I. Riley and Co. 1806 *

Pocahontas

relates her history and is the title work of her 1841 collection of poetry.

"Powhatan (d. 1618)"Encyclopedia Virginia

Retrieved February 18, 2011. * Kupperman, Karen Ordahl. ''Indians and English: Facing Off in Early America''. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000. * Lemay, J.A. Leo. ''Did Pocahontas Save Captain John Smith?'' Athens, Georgia: The University of Georgia Press, 1992 * Price, David A. ''Love and Hate in Jamestown''. New York: Vintage, 2003. * Purchas, Samuel. ''Hakluytus Posthumus or Purchas His Pilgrimes''. 1625. Repr. Glasgow: James MacLehose, 1905–1907. vol. 19 * Rolfe, John. Letter to Thomas Dale. 1614. Repr. in ''Jamestown Narratives'', ed. Edward Wright Haile. Champlain, VA: Roundhouse, 1998 * Rolfe, John. Letter to Edwin Sandys. June 8, 1617

Repr. in ''The Records of the Virginia Company of London''

ed. Susan Myra Kingsbuy. Washington: US Government Printing Office, 1906–1935. Vol. 3 * Rountree, Helen C. (November 3, 2010)

"Divorce in Early Virginia Indian Society"Encyclopedia Virginia

Retrieved February 18, 2011. * Rountree, Helen C. (November 3, 2010)

"Early Virginia Indian Education"Encyclopedia Virginia

Retrieved February 27, 2011. * Rountree, Helen C. (November 3, 2010)

"Uses of Personal Names by Early Virginia Indians"Encyclopedia Virginia

Retrieved February 18, 2011. * Rountree, Helen C. (December 8, 2010)

"Pocahontas (d. 1617)"Encyclopedia Virginia

Retrieved February 18, 2011. * Smith, John

''A True Relation of such Occurrences and Accidents of Noate as hath Hapned in Virginia''

!---This is Smith's spelling, not a typo!--->, 1608. Repr. in ''The Complete Works of John Smith (1580–1631)''. Ed. Philip L. Barbour. Chapel Hill: University Press of Virginia, 1983. Vol. 1 * Smith, John.

A Map of Virginia

', 1612. Repr. in ''The Complete Works of John Smith (1580–1631)'', Ed. Philip L. Barbour. Chapel Hill: University Press of Virginia, 1983. Vol. 1 * Smith, John. Letter to Queen Anne. 1616. Repr. a

1997, Accessed April 23, 2006. * Smith, John. ''

Captain John Smith

Project Gutenberg Text, accessed July 4, 2006 * Woodward, Grace Steele. ''Pocahontas''. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1969.

Captain John Smith

Project Gutenberg Text, accessed July 4, 2006 * Warner, Charles Dudley, ''The Story of Pocahontas'', 1881. Repr. i

The Story of Pocahontas

Project Gutenberg Text, accessed July 4, 2006 * Woodward, Grace Steele. ''Pocahontas''. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1969. or * * ''Pocahontas, Alias Matoaka, and Her Descendants Through Her Marriage at Jamestown, Virginia, in April 1614, with John Rolfe, Gentleman'', Wyndham Robertson, Printed by J. W. Randolph & English, Richmond, Va., 1887

Pocahontas: Her Life and Legend

– National Park Service – Historic Jamestowne

''The Story of Virginia: An American Experience''. Virginia Historical Society.

''The Story of Virginia: An American Experience''. Virginia Historical Society.

''Virtual Jamestown''

Includes text of many original accounts

"The Pocahontas Archive"

a comprehensive bibliography of texts about Pocahontas

On this day in history: Pocahontas marries John Rolfe

History.com * Michals, Debra

"Pocahontas"

National Women's History Museum. 2015. {{DEFAULTSORT:Pocahontas 1590s births 1617 deaths 17th-century American people 17th-century American women 17th-century Native American people 17th-century Native American women Immigrants to the Kingdom of England Bolling family (Virginia) Converts to Protestantism from pagan religions Kidnapped American children Native American Christians Pamunkey people People from colonial Virginia People from Jamestown, Virginia People of the Powhatan Confederacy Rolfe family (Virginia)

Powhatan people

Powhatan people () are Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands who belong to member tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy, or Tsenacommacah. They are Algonquian peoples whose historic territories were in eastern Virginia.

Their Powhata ...

, notable for her association with the colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

. She was the daughter of Wahunsenacawh

Powhatan (), whose proper name was Wahunsenacawh (alternately spelled Wahunsenacah, Wahunsunacock, or Wahunsonacock), was the leader of the Powhatan, an alliance of Algonquian-speaking Native Americans living in Tsenacommacah, in the Tidewat ...

, the paramount chief of a network of tributary tribes in the Tsenacommacah

Tsenacommacah (pronounced in English; also written Tscenocomoco, Tsenacomoco, Tenakomakah, Attanoughkomouck, and Attan-Akamik) is the name given by the Powhatan people to their native homeland, the area encompassing all of Tidewater Virginia ...

(known in English as the Powhatan Confederacy), encompassing the Tidewater region

Tidewater is a region in the Atlantic Plains of the United States located east of the Atlantic Seaboard fall line (the natural border where the tidewater meets with the Piedmont region) and north of the Deep South. The term "tidewater" can be ...

of what is today the U.S. state of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

.

Pocahontas was captured and held for ransom by English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Culture, language and peoples

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

* ''English'', an Amish ter ...

colonists during hostilities in 1613. During her captivity, she was encouraged to convert to Christianity

Conversion to Christianity is the religious conversion of a previously non-Christian person that brings about changes in what sociologists refer to as the convert's "root reality" including their social behaviors, thinking and ethics. The sociol ...

and was baptized

Baptism (from ) is a Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by sprinkling or pouring water on the head, or by immersing in water either partially or completely, traditionally three ...

under the name Rebecca. She married the tobacco planter John Rolfe

John Rolfe ( – March 1622) was an English explorer, farmer and merchant. He is best known for being the husband of Pocahontas and the first settler in the colony of Virginia to successfully cultivate a tobacco crop for export.

He played a ...

in April 1614 at the age of about 17 or 18, and she bore their son, Thomas Rolfe

Thomas Rolfe (January 30, 1615 – ) was the only child of Pocahontas and her English husband, John Rolfe. His maternal grandfather was Chief Powhatan, the leader of the Powhatan tribe in Virginia.

Early life

Thomas Rolfe was born in the English ...

, in January 1615.

In 1616, the Rolfes travelled to London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, where Pocahontas was presented to English society as an example of the " civilized savage" in hopes of stimulating investment in Jamestown. On this trip, she may have met Squanto

Tisquantum (; 1585 (±10 years?) – November 30, 1622 Old Style, O.S.), more commonly known as Squanto (), was a member of the Patuxet tribe of Wampanoags, best known for being an early liaison between the Native American population in Southe ...

, a Patuxet

The Patuxet were a Native American band of the Wampanoag tribal confederation. They lived primarily in and around modern-day Plymouth, Massachusetts, and were among the first Native Americans encountered by European settlers in the region in the ...

man from New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

. Pocahontas became a celebrity, was elegantly fêted, and attended a masque

The masque was a form of festive courtly entertainment that flourished in 16th- and early 17th-century Europe, though it was developed earlier in Italy, in forms including the intermedio (a public version of the masque was the pageant). A mas ...

at Whitehall Palace

The Palace of Whitehall – also spelled White Hall – at Westminster was the main residence of the English monarchs from 1530 until 1698, when most of its structures, with the notable exception of Inigo Jones's Banqueting House of 1622, ...

. In 1617, the Rolfes intended to sail for Virginia, but Pocahontas died at Gravesend

Gravesend is a town in northwest Kent, England, situated 21 miles (35 km) east-southeast of Charing Cross (central London) on the Bank (geography), south bank of the River Thames, opposite Tilbury in Essex. Located in the diocese of Roche ...

, Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

, England, of unknown causes, aged 20 or 21. She was buried in St George's Church, Gravesend

St George's Church, Gravesend, is a Grade II*-listed Anglican church dedicated to Saint George the patriarch of England, which is situated near the foot of Gravesend High Street in the Borough of Gravesham. It serves as Gravesend's parish chu ...

; her grave's exact location is unknown because the church was rebuilt after being destroyed by a fire.

Numerous places, landmarks, and products in the United States have been named after Pocahontas. Her story has been romanticized over the years, many aspects of which are fictional. Many of the stories told about her by the English explorer John Smith have been contested by her documented descendants.Price, pp. 243–244 She is a subject of art, literature, and film. Many famous people have claimed to be among her descendants, including members of the First Families of Virginia

The First Families of Virginia, or FFV, are a group of early settler families who became a socially and politically dominant group in the British Colony of Virginia and later the Commonwealth of Virginia. They descend from European colonists who ...

, First Lady Edith Wilson

Edith Wilson ( Bolling, formerly Galt; October 15, 1872 – December 28, 1961) was First Lady of the United States from 1915 to 1921 as the second wife of President Woodrow Wilson. She married the widower Wilson in December 1915, during his firs ...

, American actor Glenn Strange

George Glenn Strange (August 16, 1899 – September 20, 1973) was an American actor who appeared in hundreds of Western (genre), Western films. He played Sam Noonan, the bartender on Columbia Broadcasting System, CBS's ''Gunsmoke'' televisio ...

, and astronomer Percival Lowell

Percival Lowell (; March 13, 1855 – November 12, 1916) was an American businessman, author, mathematician, and astronomer who fueled speculation that there were canals on Mars, and furthered theories of a ninth planet within the Solar System ...

.

Early life

Pocahontas's birth year is unknown, but some historians estimate it to have been around 1596. In ''A True Relation of Virginia'' (1608), the English explorer John Smith described meeting Pocahontas in the spring of 1608 when she was "a child of ten years old".Smith''True Relation''

, p. 93. In a 1616 letter, Smith again described her as she was in 1608, but this time as "a child of twelve or thirteen years of age".Smith. Pocahontas was the daughter of

Chief Powhatan

Powhatan (), whose proper name was Wahunsenacawh (alternately spelled Wahunsenacah, Wahunsunacock, or Wahunsonacock), was the leader of the Powhatan, an alliance of Algonquian-speaking Native Americans living in Tsenacommacah, in the Tidewat ...

, paramount chief of Tsenacommacah

Tsenacommacah (pronounced in English; also written Tscenocomoco, Tsenacomoco, Tenakomakah, Attanoughkomouck, and Attan-Akamik) is the name given by the Powhatan people to their native homeland, the area encompassing all of Tidewater Virginia ...

, an alliance of about thirty Algonquian-speaking groups and petty chiefdoms in the Tidewater region

Tidewater is a region in the Atlantic Plains of the United States located east of the Atlantic Seaboard fall line (the natural border where the tidewater meets with the Piedmont region) and north of the Deep South. The term "tidewater" can be ...

of the present-day U.S. state of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

. Her mother's name and origin are unknown, but she was probably of lowly status. English adventurer Henry Spelman

Sir Henry Spelman (c. 1562 – October 1641) was an English antiquary, noted for his detailed collections of medieval records, in particular of church councils.

Life

Spelman was born in Congham, Norfolk, the eldest son of Henry Spelman (d. 1 ...

had lived among the Powhatan people

Powhatan people () are Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands who belong to member tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy, or Tsenacommacah. They are Algonquian peoples whose historic territories were in eastern Virginia.

Their Powhata ...

as an interpreter, and he noted that, when one of the paramount chief's many wives gave birth, she was returned to her place of origin and supported there by the paramount chief until she found another husband. However, little is known about Pocahontas's mother, and it has been theorized that she died in childbirth. The Mattaponi Reservation people are descendants of the Powhatans, and their oral tradition claims that Pocahontas's mother was the first wife of Powhatan and that Pocahontas was named after her.

Names

According to colonistWilliam Strachey

William Strachey (4 April 1572 – buried 16 August 1621) was an English writer whose works are among the primary sources for the early history of the English colonisation of North America. He is best remembered today as the eye-witness reporter ...

, "Pocahontas" was a childhood nickname meaning "little wanton". Some interpret the meaning as "playful one".Rountree, Helen C. (November 3, 2010)"Cooking in Early Virginia Indian Society"

. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

anthropologist

An anthropologist is a scientist engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropologists study aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms, values ...

Helen C. Rountree, Pocahontas revealed her secret name to the colonists "only after she had taken another religious – baptismal – name" of Rebecca.

Title and status

Pocahontas is frequently viewed as a princess in popular culture. In 1841, William Watson Waldron ofTrinity College, Dublin

Trinity College Dublin (), officially titled The College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity of Queen Elizabeth near Dublin, and legally incorporated as Trinity College, the University of Dublin (TCD), is the sole constituent college of the Univ ...

, published ''Pocahontas, American Princess: and Other Poems'', calling her "the beloved and only surviving daughter of the king". She was her father's "delight and darling", according to colonist Captain Ralph Hamor

Ralph Hamor, Jr. ( - ) was one of the original colonists to settle in Virginia, and author of ''A True Discourse of the Present State of Virginia'', which he wrote upon returning to London in 1615.

Spellings of his first and last name vary; alter ...

, but she was not in line to inherit a position as a ''weroance

Weroance ( e:ɹoanzor e:ɹoansor [we:ɹoəns">e:ɹoans">e:ɹoanzor [we:ɹoansor [we:ɹoəns is an Algonquian word meaning leader or commander among the Powhatan">Algonquian languages">Algonquian word meaning leader or commander among the Powha ...

'', sub-chief, or ''mamanatowick'' (paramount chief). Instead, Powhatan's brothers and sisters and his sisters' children all stood in line to succeed him.Rountree, Helen C. (January 25, 2011)"Pocahontas (d. 1617)"

. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

Interactions with the colonists

John Smith

Pocahontas is most famously linked to colonist John Smith, who arrived in Virginia with 100 other settlers in April 1607. The colonists built a fort on a marshy peninsula on the James River, and had numerous encounters over the next several months with the people of Tsenacommacah – some of them friendly, some hostile. A hunting party led by Powhatan's close relative Opechancanough captured Smith in December 1607 while he was exploring on theChickahominy River

The Chickahominy is an U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed April 1, 2011 river in eastern Virginia. The river, which serves as the eastern border of Charles City County, Vir ...

and brought him to Powhatan's capital at Werowocomoco

Werowocomoco was a village that served as the headquarters of Chief Powhatan, a Virginia Algonquian political and spiritual leader. The name ''Werowocomoco'' comes from the Powhatan ''werowans'' ('' weroance''), meaning "leader" in English; a ...

. In his 1608 account, Smith describes a great feast followed by a long talk with Powhatan. He does not mention Pocahontas in relation to his capture, and claims that they first met some months later. Margaret Huber suggests that Powhatan was attempting to bring Smith and the other colonists under his own authority. He offered Smith rule of the town of Capahosic, which was close to his capital at Werowocomoco, as he hoped to keep Smith and his men "nearby and better under control".

In 1616, Smith wrote a letter to Queen Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I. She was List of Scottish royal consorts, Queen of Scotland from their marriage on 20 August 1589 and List of English royal consorts, Queen of Engl ...

, the wife of King James, in anticipation of Pocahontas' visit to England. In this new account, his capture included the threat of his own death: "at the minute of my execution, she hazarded the beating out of her own brains to save mine; and not only that but so prevailed with her father, that I was safely conducted to Jamestown." He expanded on this in his 1624 '' Generall Historie'', published seven years after the death of Pocahontas. He explained that he was captured and taken to the paramount chief where "two great stones were brought before Powhatan: then as many as could layd hands on him mith dragged him to them, and thereon laid his head, and being ready with their clubs, to beate out his braines, Pocahontas the Kings dearest daughter, when no intreaty could prevaile, got his head in her armes, and laid her owne upon his to save him from death."

Karen Ordahl Kupperman

Karen Ordahl Kupperman (born 23 April 1939) is an American historian who specializes in colonial history in the Atlantic world of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Biography

Karen Ordahl Kupperman was born in Devils Lake, North Dakota on ...

suggests that Smith used such details to embroider his first account, thus producing a more dramatic second account of his encounter with Pocahontas as a heroine worthy of Queen Anne's audience. She argues that its later revision and publication was Smith's attempt to raise his own stock and reputation, as he had fallen from favor with the London Company

The Virginia Company of London (sometimes called "London Company") was a division of the Virginia Company with responsibility for colonizing the east coast of North America between latitudes 34° and 41° N.

History Origins

The territory ...

which had funded the Jamestown enterprise. Anthropologist Frederic W. Gleach suggests that Smith's second account was substantially accurate but represents his misunderstanding of a three-stage ritual intended to adopt him into the confederacy,Karen Ordahl Kupperman, ''Indians and English''pp. 114, 174. but not all writers are convinced, some suggesting the absence of certain corroborating evidence.Price, pp. 243–244 Early histories did establish that Pocahontas befriended Smith and the colonists. She often went to the settlement and played games with the boys there. When the colonists were starving, "every once in four or five days, Pocahontas with her attendants brought mithso much provision that saved many of their lives that else for all this had starved with hunger." As the colonists expanded their settlement, the Powhatans felt that their lands were threatened, and conflicts arose again. In late 1609, an injury from a

gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

explosion forced Smith to return to England for medical care and the colonists told the Powhatans that he was dead. Pocahontas believed that account and stopped visiting Jamestown but learned that Smith was living in England when she traveled there with her husband John Rolfe

John Rolfe ( – March 1622) was an English explorer, farmer and merchant. He is best known for being the husband of Pocahontas and the first settler in the colony of Virginia to successfully cultivate a tobacco crop for export.

He played a ...

.

Capture

Pocahontas' capture occurred in the context of the First Anglo-Powhatan War, a conflict between the Jamestown settlers and the Natives which began late in the summer of 1609. In the first years of war, the colonists took control of the James River, both at its mouth and at the falls. In the meantime, CaptainSamuel Argall

Sir Samuel Argall ( or 1580 – ) was an English sea captain, navigator, and Deputy-Governour of Virginia, an English colony.

As a sea captain, in 1609, Argall was the first to determine a shorter northern route from England across the Atlan ...

pursued contacts with Native tribes in the northern portion of Powhatan's paramount chiefdom. The Patawomeck

The Patawomeck are a Native American tribe based in Stafford County, Virginia, along the Potomac River. ''Patawomeck'' is another spelling of Potomac.

The Patawomeck Indian Tribe of Virginia is a state-recognized tribe in Virginia that identif ...

s lived on the Potomac River

The Potomac River () is in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and flows from the Potomac Highlands in West Virginia to Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography D ...

and were not always loyal to Powhatan, and living with them was Henry Spelman, a young English interpreter. In March 1613, Argall learned that Pocahontas was visiting the Patawomeck village of Passapatanzy and living under the protection of the ''weroance'' Iopassus (also known as Japazaws).Rountree, Helen C. (December 8, 2010)"Pocahontas (d. 1617)"

. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

Treasurer

A treasurer is a person responsible for the financial operations of a government, business, or other organization.

Government

The treasury of a country is the department responsible for the country's economy, finance and revenue. The treasure ...

'', and held her for ransom

Ransom refers to the practice of holding a prisoner or item to extort money or property to secure their release. It also refers to the sum of money paid by the other party to secure a captive's freedom.

When ransom means "payment", the word ...

, demanding the release of colonial prisoners held by her father and the return of various stolen weapons and tools. Powhatan returned the prisoners but failed to satisfy the colonists with the number of weapons and tools that he returned. A long standoff ensued, during which the colonists kept Pocahontas captive.

During the year-long wait, Pocahontas was held at the English settlement of Henricus

The "Citie of Henricus"—also known as Henricopolis, Henrico Town or Henrico—was a settlement in Virginia founded by Sir Thomas Dale in 1611 as an alternative to the swampy and dangerous area around the original English settlement at James ...

in present-day Chesterfield County, Virginia

Chesterfield County is a County (United States), county located just south of Richmond, Virginia, Richmond in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia. The county's borders are primarily defined by the James River to the north an ...

. Little is known about her life there, although colonist Ralph Hamor

Ralph Hamor, Jr. ( - ) was one of the original colonists to settle in Virginia, and author of ''A True Discourse of the Present State of Virginia'', which he wrote upon returning to London in 1615.

Spellings of his first and last name vary; alter ...

wrote that she received "extraordinary courteous usage" (meaning she was treated well).Hamor, ''True Discourse'', p. 804. Linwood "Little Bear" Custalow refers to an oral tradition which claims that Pocahontas was rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault involving sexual intercourse, or other forms of sexual penetration, carried out against a person without consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or against a person ...

d; Helen Rountree counters that "other historians have disputed that such oral tradition survived and instead argue that any mistreatment of Pocahontas would have gone against the interests of the English in their negotiations with Powhatan. A truce had been called, the Indians still far outnumbered the English, and the colonists feared retaliation." At this time, Henricus minister Alexander Whitaker

Alexander Whitaker (1585–1616) was an English Anglican theologian who settled in North America in Virginia Colony in 1611 and established two churches near the Jamestown colony. He was also known as "The Apostle of Virginia" by contemporaries ...

taught Pocahontas about Christianity and helped her improve her English. Upon her baptism, she took the Christian name "Rebecca".

In March 1614, the stand-off escalated to a violent confrontation between hundreds of colonists and Powhatan men on the Pamunkey River

The Pamunkey River is a tributary of the York River, about long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed April 1, 2011 in eastern Virginia in the United States. Via the York Ri ...

, and the colonists encountered a group of senior Native leaders at Powhatan's capital of Matchcot. The colonists allowed Pocahontas to talk to her tribe when Powhatan arrived, and she reportedly rebuked him for valuing her "less than old swords, pieces, or axes". She said that she preferred to live with the colonists "who loved her".

Possible first marriage

Mattaponi tradition holds that Pocahontas' first husband was Kocoum, brother of the Patawomeck ''weroance'' Japazaws, and that Kocoum was killed by the colonists after his wife's capture in 1613. Today's Patawomecks believe that Pocahontas and Kocoum had a daughter named Ka-Okee who was raised by the Patawomecks after her father's death and her mother's abduction. Kocoum's identity, location, and very existence have been widely debated among scholars for centuries; the only mention of a "Kocoum" in any English document is a brief statement written about 1616 by William Strachey that Pocahontas had been living married to a "private captaine called Kocoum" for two years. Pocahontas married John Rolfe in 1614, and no other records even hint at any previous husband, so some have suggested that Strachey was mistakenly referring to Rolfe himself, with the reference being later misunderstood as one of Powhatan's officers.Marriage to John Rolfe

During her stay at Henricus, Pocahontas met

During her stay at Henricus, Pocahontas met John Rolfe

John Rolfe ( – March 1622) was an English explorer, farmer and merchant. He is best known for being the husband of Pocahontas and the first settler in the colony of Virginia to successfully cultivate a tobacco crop for export.

He played a ...

. Rolfe's English-born wife Sarah Hacker and child Bermuda had died on the way to Virginia after the wreck of the ship ''Sea Venture

''Sea Venture'' was a seventeenth-century English sailing ship, part of the Third Supply mission flotilla to the Jamestown Colony in 1609. She was the 300 ton flagship of the London Company. During the voyage to Virginia, ''Sea Venture'' encount ...

'' on the Summer Isles, now known as Bermuda

Bermuda is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. The closest land outside the territory is in the American state of North Carolina, about to the west-northwest.

Bermuda is an ...

. He established the Virginia plantation Varina Farms

Varina Farms, also known as Varina Plantation or Varina Farms Plantation or Varina on the James, is a plantation established in the 17th century on the James River about south of Richmond, Virginia. An property was listed on the National Regis ...

, where he cultivated a new strain of tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

. Rolfe was a pious man and agonized over the potential moral repercussions of marrying a heathen, though in fact Pocahontas had accepted the Christian faith and taken the baptismal name Rebecca. In a long letter to the governor requesting permission to wed her, he expressed his love for Pocahontas and his belief that he would be saving her soul. He wrote that he was:

The couple were married on April 5, 1614, by chaplain Richard Buck

Richard Thomas Buck (born 14 November 1986 in Grimsby, Lincolnshire) is a former British sprinter who specialised in the 400 metres event. He is from York, and trains in Loughborough. Buck's current club is City of York A.C. (formerly Nestlé ...

, probably at Jamestown. For two years they lived at Varina Farms, across the James River from Henricus. Their son, Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

, was born in January 1615.

The marriage created a climate of peace between the Jamestown colonists and Powhatan's tribes; it endured for eight years as the "Peace of Pocahontas". In 1615, Ralph Hamor wrote, "Since the wedding we have had friendly commerce and trade not only with Powhatan but also with his subjects round about us." The marriage was controversial in the English court at the time because "a commoner" had "the audacity" to marry a "princess".

England

One goal of the London Company was to convert Native Americans to Christianity, and they saw an opportunity to promote further investment with the conversion of Pocahontas and her marriage to Rolfe, all of which also helped end the First Anglo-Powhatan War. The company decided to bring Pocahontas to England as a symbol of the tamed

One goal of the London Company was to convert Native Americans to Christianity, and they saw an opportunity to promote further investment with the conversion of Pocahontas and her marriage to Rolfe, all of which also helped end the First Anglo-Powhatan War. The company decided to bring Pocahontas to England as a symbol of the tamed New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

"savage" and the success of the Virginia colony, and the Rolfes arrived at the port of Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

on June 12, 1616. The family journeyed to London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

by coach, accompanied by eleven other Powhatans including a holy man named Tomocomo

Uttamatomakkin (known as Tomocomo for short) was a Powhatan holy man who accompanied Pocahontas when she was taken to London in 1616.Dale, Thomas. Letter to Sir Ralph Winwood. 3 June 1616. Repr. in Jamestown Narratives, ed. Edward Wright Haile. Ch ...

. John Smith was living in London at the time while Pocahontas was in Plymouth, and she learned that he was still alive.Smith, ''General History''. p. 261. Smith did not meet Pocahontas, but he wrote to Queen Anne urging that Pocahontas be treated with respect as a royal visitor. He suggested that, if she were treated badly, her "present love to us and Christianity might turn to... scorn and fury", and England might lose the chance to "rightly have a Kingdom by her means".

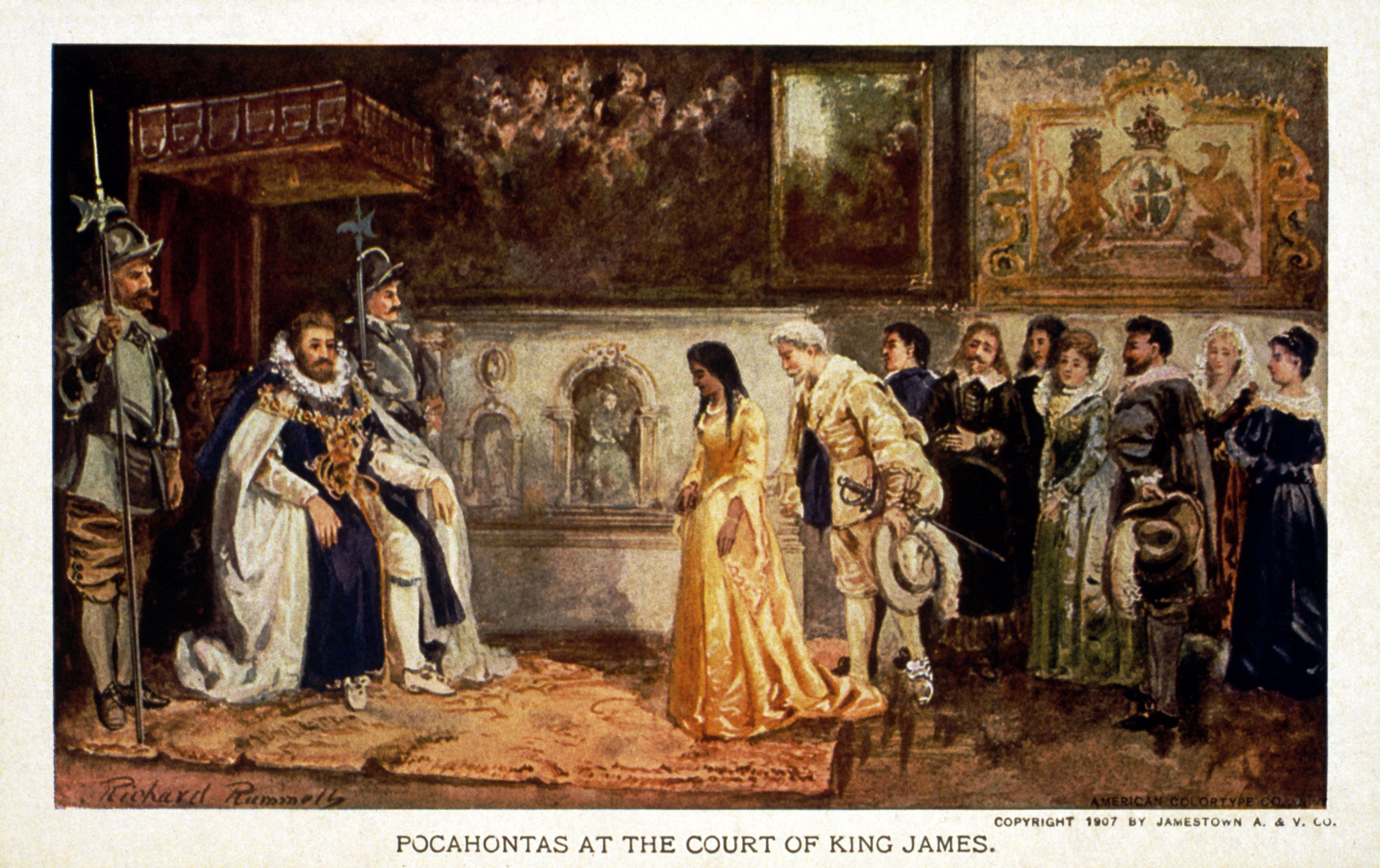

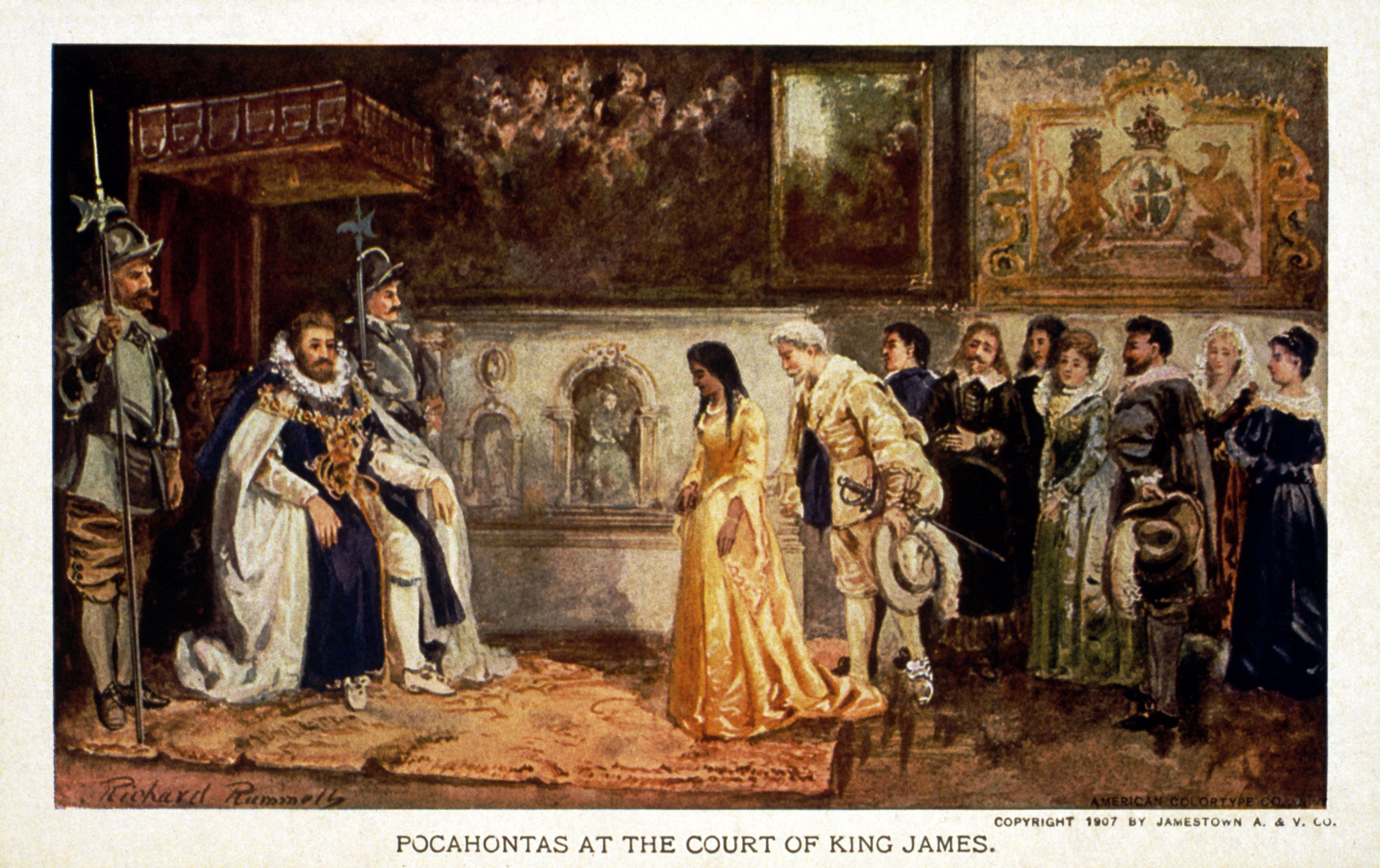

Pocahontas was entertained at various social gatherings. On January 5, 1617, she and Tomocomo were brought before King James at the old Banqueting House

The Banqueting House, on Whitehall in the City of Westminster, central London, is the grandest and best-known survivor of the architectural genre of banqueting houses, constructed for elaborate entertaining. It is the only large surviving comp ...

in the Palace of Whitehall

The Palace of Whitehall – also spelled White Hall – at Westminster was the main residence of the English monarchs from 1530 until 1698, when most of its structures, with the notable exception of Inigo Jones's Banqueting House of 1622, ...

at a performance of Ben Jonson

Benjamin Jonson ( 11 June 1572 – ) was an English playwright, poet and actor. Jonson's artistry exerted a lasting influence on English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours; he is best known for the satire, satirical ...

's masque ''The Vision of Delight

''The Vision of Delight'' was a Jacobean era masque written by Ben Jonson. It was most likely performed on Twelfth Night, 6 January 1617 in the Banqueting House at Whitehall Palace, and repeated on 19 January that year.

''The Vision of Deligh ...

''. According to Smith, the king was so unprepossessing that neither Pocahontas nor Tomocomo realized whom they had met until it was explained to them afterward.

Pocahontas was not a princess in Powhatan culture, but the London Company presented her as one to the English public because she was the daughter of an important chief. The inscription on a 1616 engraving of Pocahontas reads "MATOAKA ALS REBECCA FILIA POTENTISS : PRINC : POWHATANI IMP:VIRGINIÆ", meaning "Matoaka, alias Rebecca, daughter of the most powerful prince of the Powhatan Empire of Virginia". Many English at this time recognized Powhatan as the ruler of an empire, and presumably accorded to his daughter what they considered appropriate status. Smith's letter to Queen Anne refers to "Powhatan their chief King". Cleric and travel writer Samuel Purchas

Samuel Purchas ( – 1626) was an England, English Anglican cleric who published several volumes of reports by travellers to foreign countries.

Career

Purchas was born at Thaxted, Essex, England, Essex, son of a yeoman. He graduated from St J ...

recalled meeting Pocahontas in London, noting that she impressed those whom she met because she "carried her selfe as the daughter of a king".Purchas, ''Hakluytus Posthumus''. Vol. 19 p. 118. When he met her again in London, Smith referred to her deferentially as a "King's daughter".

Pocahontas was apparently treated well in London. At the masque, her seats were described as "well placed" and, according to Purchas, London's Bishop John King "entertained her with festival state and pomp beyond what I have seen in his greate hospitalitie afforded to other ladies".

Not all the English were so impressed, however. Helen C. Rountree claims that there is no contemporaneous evidence to suggest that Pocahontas was regarded in England "as anything like royalty," despite the writings of John Smith. Rather, she was considered to be something of a curiosity, according to Rountree, who suggests that she was merely "the Virginian woman" to most Englishmen.

Pocahontas and Rolfe lived in the suburb of Brentford

Brentford is a suburban town in West (London sub region), West London, England and part of the London Borough of Hounslow. It lies at the confluence of the River Brent and the River Thames, Thames, west of Charing Cross.

Its economy has dive ...

, Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a Historic counties of England, former county in South East England, now mainly within Greater London. Its boundaries largely followed three rivers: the River Thames, Thames in the south, the River Lea, Le ...

, for some time, as well as at Rolfe's family home at Heacham

Heacham is a large village in West Norfolk, England, overlooking The Wash. It lies between King's Lynn, to the south, and Hunstanton, about to the north. It has been a seaside resort for over a century and a half.

History

There is evidence of ...

, Norfolk

Norfolk ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in England, located in East Anglia and officially part of the East of England region. It borders Lincolnshire and The Wash to the north-west, the North Sea to the north and eas ...

. In early 1617, Smith met the couple at a social gathering and wrote that, when Pocahontas saw him, "without any words, she turned about, obscured her face, as not seeming well contented," and was left alone for two or three hours. Later, they spoke more; Smith's record of what she said to him is fragmentary and enigmatic. She reminded him of the "courtesies she had done," saying, "you did promise Powhatan what was yours would be his, and he the like to you." She then discomfited him by calling him "father", explaining that Smith had called Powhatan "father" when he was a stranger in Virginia, "and by the same reason so must I do you". Smith did not accept this form of address because, he wrote, Pocahontas outranked him as "a King's daughter". Pocahontas then said, "with a well-set countenance":

Finally, Pocahontas told Smith that she and her tribe had thought him dead, but her father had told Tomocomo to seek him "because your countrymen will lie much".

Death

In March 1617, Rolfe and Pocahontas boarded a ship to return to Virginia, but they had sailed only as far asGravesend

Gravesend is a town in northwest Kent, England, situated 21 miles (35 km) east-southeast of Charing Cross (central London) on the Bank (geography), south bank of the River Thames, opposite Tilbury in Essex. Located in the diocese of Roche ...

on the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, s ...

when Pocahontas became gravely ill. She was taken ashore, where she died from unknown causes, aged approximately 21 and "much lamented". According to Rolfe, she declared that "all must die"; for her, it was enough that her child lived. Speculated causes of her death include pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

, smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

, tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

, hemorrhagic dysentery ("the Bloody flux") and poisoning.

Pocahontas's funeral took place on March 21, 1617, in the parish of St George's Church, Gravesend

St George's Church, Gravesend, is a Grade II*-listed Anglican church dedicated to Saint George the patriarch of England, which is situated near the foot of Gravesend High Street in the Borough of Gravesham. It serves as Gravesend's parish chu ...

. Her grave is thought to be underneath the church's chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the Choir (architecture), choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may termi ...

, though that church was destroyed in a fire in 1727 and its exact site is unknown. Since 1958 she has been commemorated by a life-sized bronze statue in St. George's churchyard, a replica of the 1907 Jamestown sculpture by the American sculptor William Ordway Partridge

William Ordway Partridge (April 11, 1861 – May 22, 1930) was an American sculptor, teacher and author. Among his best-known works are the Shakespeare Monument in Chicago, the equestrian statue of General Grant in Brooklyn, the ''Pietà'' at St ...

.

Legacy

Pocahontas and John Rolfe had a son,Thomas Rolfe

Thomas Rolfe (January 30, 1615 – ) was the only child of Pocahontas and her English husband, John Rolfe. His maternal grandfather was Chief Powhatan, the leader of the Powhatan tribe in Virginia.

Early life

Thomas Rolfe was born in the English ...

, born in January 1615. Thomas and his wife, Jane Poythress, had a daughter, Jane Rolfe

Jane Rolfe (October 10, 1650 – January 27, 1676) was the granddaughter of Pocahontas and English colonist John Rolfe (credited with introducing a strain of tobacco for export by the struggling Virginia Colony).

Her husband was Colonel Robert B ...

, who was born in Varina, in present-day Henrico County, Virginia

Henrico County , officially the County of Henrico, is a County (United States), county located in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population wa ...

, on October 10, 1650.John Frederick Dorman, ''Adventurers of Purse and Person'', 4th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 23–36. Jane married Robert Bolling

Robert Bolling (December 26, 1646July 17, 1709) was an English-born merchant, planter and politician. and the founder of the Bolling family of Virginia, one of the First Families of Virginia, with at least fifteen descendants (including two of h ...

of present-day Prince George County, Virginia

Prince George County is a county located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 43,010. Its county seat is Prince George.

Prince George County is located within the Greater Richmond Region of the U.S. sta ...

. Their son, John Bolling

John Bolling (January 27, 1676April 20, 1729) was an American merchant, planter, politician and military officer in the colony of Virginia, who served several terms in the House of Burgesses, all representing Henrico County. The earliest of four ...

, was born in 1676. John Bolling married Mary Kennon and had six surviving children, each of whom married and had surviving children.

In 1907, Pocahontas was the first Native American to be honored on a U.S. stamp. She was a member of the inaugural class of Virginia Women in History

Virginia Women in History was an annual program sponsored by the Library of Virginia that honored Virginia women, living and dead, for their contributions to their community, region, state, and nation. The program began in 2000 under the aegis of t ...

in 2000. In July 2015, the Pamunkey

The Pamunkey Indian Tribe is a federally recognized tribe of Pamunkey people in Virginia. They control the Pamunkey Indian Reservation in King William County, Virginia. Historically, they spoke the Pamunkey language.

They are one of 11 Native ...

Native tribe became the first federally recognized tribe

A federally recognized tribe is a Native American tribe recognized by the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs as holding a government-to-government relationship with the US federal government. In the United States, the Native American tribe ...

in the state of Virginia; they are descendants of the Powhatan chiefdom, of which Pocahontas was a member. Pocahontas is the twelfth great-grandmother of the American actor Edward Norton

Edward Harrison Norton (born August 18, 1969) is an American actor, producer, director, and screenwriter. After graduating from Yale College in 1991 with a degree in history, he worked for a few months in Japan before moving to New York City ...

.

Image gallery

Jamestown, Virginia

The Jamestown settlement in the Colony of Virginia was the first permanent British colonization of the Americas, English settlement in the Americas. It was located on the northeast bank of the James River, about southwest of present-day Willia ...

File:Pocahontas Statue at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.jpg, Statue by Joseph Mozier

File:Seal of Henrico County, Virginia.png, Likeness of Pocahontas on the seal of Henrico County, Virginia

Henrico County , officially the County of Henrico, is a County (United States), county located in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population wa ...

File:Pochahontas1616.jpg, A painting of Pocahontas in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC

Cultural representations

After her death, increasingly fanciful and romanticized representations were produced about Pocahontas, in which she and Smith are frequently portrayed as romantically involved. Contemporaneous sources substantiate claims of their friendship but not romance. The first claim of their romantic involvement was in John Davis' ''Travels in the United States of America'' (1803).

Rayna Green has discussed the similar fetishization that Native and Asian women experience. Both groups are viewed as "exotic" and "submissive", which aids their dehumanization. Also, Green touches on how Native women had to either "keep their exotic distance or die," which is associated with the widespread image of Pocahontas trying to sacrifice her life for John Smith.

Cornel Pewewardy writes, "In Pocahontas, Indian characters such as Grandmother Willow, Meeko, and Flit belong to the

After her death, increasingly fanciful and romanticized representations were produced about Pocahontas, in which she and Smith are frequently portrayed as romantically involved. Contemporaneous sources substantiate claims of their friendship but not romance. The first claim of their romantic involvement was in John Davis' ''Travels in the United States of America'' (1803).

Rayna Green has discussed the similar fetishization that Native and Asian women experience. Both groups are viewed as "exotic" and "submissive", which aids their dehumanization. Also, Green touches on how Native women had to either "keep their exotic distance or die," which is associated with the widespread image of Pocahontas trying to sacrifice her life for John Smith.

Cornel Pewewardy writes, "In Pocahontas, Indian characters such as Grandmother Willow, Meeko, and Flit belong to the Disney

The Walt Disney Company, commonly referred to as simply Disney, is an American multinational mass media and entertainment industry, entertainment conglomerate (company), conglomerate headquartered at the Walt Disney Studios (Burbank), Walt Di ...

tradition of familiar animals. In so doing, they are rendered as cartoons, certainly less realistic than Pocahontas and John Smith; In this way, Indians remain marginal and invisible, thereby ironically being 'strangers in their own lands' – the shadow Indians. They fight desperately on the silver screen in defense of their asserted rights, but die trying to kill the white hero or save the Indian woman."

Stage

*Pocahontas: Schauspiel mit Gesang, in fünf Akten (A Play with Songs, in five Acts)

' by Johann Wilhelm Rose (1784) *''Captain Smith and the Princess Pocahontas'' (1806) *

James Nelson Barker

James Nelson Barker (June 17, 1784 – March 9, 1858) was an American soldier, playwright and politician. He rose to the rank of major in the Army during the War of 1812, wrote ten plays, and was mayor of Philadelphia.

Early life

Barker was born ...

's ''The Indian Princess; or, La Belle Sauvage'' (1808)

* George Washington Parke Custis

George Washington Parke Custis (April 30, 1781 – October 10, 1857) was an American antiquarian, author, playwright, and slave owner. He was a veteran of the War of 1812. His father John Parke Custis served in the American Revolution wi ...

, ''Pocahontas; or, The Settlers of Virginia'' (1830)

* John Brougham

John Brougham (9 May 1814 – 7 June 1880) was an Irish and American actor, dramatist, poet, theatre manager, and author. As an actor and dramatist he had most of his career in the United States, where he was celebrated for his portrayals of com ...

's production of the burlesque '' Po-ca-hon-tas, or The Gentle Savage'' (1855)

* Brougham's burlesque revised for London as ''La Belle Sauvage'', opening at St James's Theatre, November 27, 1869

* Sydney Grundy

Sydney Grundy (23 March 1848 – 4 July 1914) was an English dramatist. Most of his works were adaptations of European plays, and many became successful enough to tour throughout the English-speaking world. He is, however, perhaps best remembe ...

's ''Pocahontas'', a comic opera, music by Edward Solomon

Edward Solomon (25 July 1855 – 22 January 1895) was an English composer, conductor, orchestrator and pianist. He died at age 39 by which time he had written dozens of works produced for the stage, including several for the D'Oyly Carte Ope ...

, which opened at the Empire Theatre in London on December 26, 1884, and ran for just 24 performances with Lillian Russell

Lillian Russell (born Helen Louise Leonard; December 4, 1860 or 1861 – June 6, 1922) was an American actress and singer. She became one of the most famous actresses and singers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, praised for her beaut ...

in the title role and C. Hayden Coffin in his stage debut in the piece, taking the role of Captain Smith for the final six nights

* ''Miss Pocahontas'' (Broadway musical), Lyric Theatre, New York City, October 28, 1907

* ''Pocahontas'' ballet by Elliot Carter Jr., Martin Beck Theatre, New York City, May 24, 1939

* ''Pocahontas'' musical by Kermit Goell, Lyric Theatre, West End, London, November 14, 1963

Stamps

* TheJamestown Exposition

The Jamestown Exposition, also known as the Jamestown Ter-Centennial Exposition of 1907, was one of the many world's fairs and expositions that were popular in the United States in the early part of the 20th century. Commemorating the 300th anni ...

was held in Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk ( ) is an independent city (United States), independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. It had a population of 238,005 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of cities in Virginia, third-most populous city ...

from April 26 to December 1, 1907, to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the Jamestown settlement, and three commemorative postage stamps were issued in conjunction with it. The five-cent stamp portrays Pocahontas, modeled from Simon van de Passe's 1616 engraving. About 8 million were issued.

Film

Pocahontas had renewed popularity within the media after the release of the Pocahontas Disney film in 1995. Pocahontas is depicted as a "noble, romanticsavage

Savage may refer to:

* Savage (pejorative term), a derogatory term to describe a member of a people the speaker regards as primitive and uncivilized

Arts and entertainment Fictional characters

* Bill Savage, in the 2000 AD ''Invasion!'' ...

–an innocent, one with nature, and inherently good" person, despite her being a Native woman only perpetuates the "single image mainstream society has of Natives as gentle, traditional, and stuck in the past."

Films about Pocahontas include:

* ''Pocahontas

Pocahontas (, ; born Amonute, also known as Matoaka and Rebecca Rolfe; 1596 – March 1617) was a Native American woman belonging to the Powhatan people, notable for her association with the colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. S ...

'' (1910), a Thanhouser Company silent short drama

* ''Pocahontas and John Smith'' (1924), a silent film directed by Bryan Foy

Bryan Foy (December 8, 1896 – April 20, 1977) was an American film producer and film director, director. He produced more than 200 films between 1924 and 1963. He also directed 41 films between 1923 and 1934. He headed the B picture unit a ...

* ''Captain John Smith and Pocahontas

''Captain John Smith and Pocahontas '' is a 1953 American historical western film directed by Lew Landers. The distributor was United Artists. It stars Anthony Dexter, Jody Lawrance and Alan Hale.

While most scenes were filmed in Virginia's Blu ...

'' (1953), directed by Lew Landers and starring Jody Lawrance as Pocahontas

* ''Pocahontas

Pocahontas (, ; born Amonute, also known as Matoaka and Rebecca Rolfe; 1596 – March 1617) was a Native American woman belonging to the Powhatan people, notable for her association with the colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. S ...

'' (1994), a Japanese animated production from Jetlag Productions directed by Toshiyuki Hiruma Takashi

* '' Pocahontas: The Legend'' (1995), a Canadian film based on her life

* ''Pocahontas

Pocahontas (, ; born Amonute, also known as Matoaka and Rebecca Rolfe; 1596 – March 1617) was a Native American woman belonging to the Powhatan people, notable for her association with the colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. S ...

'' (1995), a Walt Disney Company

The Walt Disney Company, commonly referred to as simply Disney, is an American multinational mass media and entertainment industry, entertainment conglomerate (company), conglomerate headquartered at the Walt Disney Studios (Burbank), Walt Di ...

animated feature, one of the ''Disney Princess

''Disney Princess'', also called the ''Princess Line'', is a media franchise and toy line owned by the Walt Disney Company. Created by Disney Consumer Products chairman Andy Mooney, the franchise features a lineup of female protagonists who hav ...

'' films, and the most well known adaptation of the Pocahontas story. The film presents a fictional romantic affair between Pocahontas and John Smith, in which Pocahontas teaches Smith respect for nature. Irene Bedard

Irene Bedard (born July 22, 1967) is an American actress, who has played mostly Native American lead roles in a variety of films. She is perhaps best known for the role of Suzy Song in the 1998 film '' Smoke Signals'', an adaptation of a Sherm ...

voiced and provided the physical model for the title character.

* '' Pocahontas II: Journey to a New World'' (1998), a direct-to-video Disney sequel depicting Pocahontas falling in love with John Rolfe and traveling to England

* ''The New World'' (2005), film directed by Terrence Malick

Terrence Frederick Malick (; born November 30, 1943) is an American filmmaker. Malick began his career as part of the New Hollywood generation of filmmakers and received awards at the Cannes Film Festival, Berlin International Film Festival, and ...

and starring Q'orianka Kilcher

Q'orianka Waira Qoiana Kilcher (; born February 11, 1990) is an American actress. Her best known film roles are Pocahontas in Terrence Malick's 2005 film '' The New World'', and Kaiulani in '' Princess Kaiulani'' (2009). In 2020, she starred i ...

as Pocahontas

* ''Pocahontas: Dove of Peace'' (2016), a docudrama produced by Christian Broadcasting Network

The Christian Broadcasting Network (CBN) is an American Christian media production and distribution organization. Founded in 1960 by Pat Robertson, it produces the long-running TV series ''The 700 Club'', co-produces the ongoing ''Superbook (198 ...

Literature

* *The first settlers of Virginia : an historical novel

' New York : Printed for I. Riley and Co. 1806 *

Lydia Sigourney

Lydia Huntley Sigourney (September 1, 1791 – June 10, 1865), Lydia Howard Huntley, was an American poet, author, and publisher during the early and mid 19th century. She was commonly known as the "Sweet Singer of Hartford, Connecticut, Hartfor ...

's long poePocahontas

relates her history and is the title work of her 1841 collection of poetry.

Art

* Simon van de Passe's engraving of 1616 * ''The abduction of Pocahontas'' (1619), a narrative engraving byJohann Theodor de Bry

Johann Theodor de Bry (1561 – 31 January 1623) was an engraver and publisher.

Biography

De Bry was born in Strasbourg, the elder son and pupil of Dirk de Bry. He greatly assisted his father in works such as, the ''Florilegium novum'', which ...

* William Ordway Partridge

William Ordway Partridge (April 11, 1861 – May 22, 1930) was an American sculptor, teacher and author. Among his best-known works are the Shakespeare Monument in Chicago, the equestrian statue of General Grant in Brooklyn, the ''Pietà'' at St ...

's bronze statue (1922) of Pocahontas in Jamestown, Virginia

The Jamestown settlement in the Colony of Virginia was the first permanent British colonization of the Americas, English settlement in the Americas. It was located on the northeast bank of the James River, about southwest of present-day Willia ...

; a replica (1958) stands in the grounds of St George's Church, Gravesend

St George's Church, Gravesend, is a Grade II*-listed Anglican church dedicated to Saint George the patriarch of England, which is situated near the foot of Gravesend High Street in the Borough of Gravesham. It serves as Gravesend's parish chu ...

* ''Baptism of Pocahontas

The United States Capitol building features a central Rotunda (architecture), rotunda below the United States Capitol dome, Capitol dome. Built between 1818 and 1824, the rotunda has been described as the United States Capitol, Capitol's "symboli ...

'' (1840), a painting by John Gadsby Chapman

John Gadsby Chapman (December 3, 1808 – November 28, 1889) was an American artist famous for ''Baptism of Pocahontas'', which was commissioned by the United States Congress and hangs in the United States Capitol rotunda.

Life and career

...

which hangs in the rotunda of the United States Capitol Building

The United States Capitol, often called the Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the seat of the United States Congress, the legislative branch of the federal government. It is located on Capitol Hill at the eastern end of the National Mall in ...

Others

*Lake Matoaka

Lake Matoaka is a mill pond on the campus of the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, located in the College Woods. Originally known both as Rich Neck Pond for the surrounding Rich Neck Plantation and Ludwell's Mill Pond for Phil ...

, an 18th-century mill pond

A mill pond (or millpond) is a body of water used as a reservoir for a water-powered mill.

Description

Mill ponds were often created through the construction of a mill dam or weir (and mill stream) across a waterway.

In many places, the co ...

on the campus of the College of William & Mary

The College of William & Mary (abbreviated as W&M) is a public university, public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia, United States. Founded in 1693 under a royal charter issued by King William III of England, William III and Queen ...

renamed for Pocahontas's Powhatan name in the 1920s

* The , a ''Barbarossa''-class ocean liner seized by the U.S. and used as a transport during the First World War

* The , name of three vessels including one that Virginia Ferry Corporation completed in 1940 for Little Creek–Cape Charles Ferry, sold to Cape May–Lewes Ferry

The Cape May–Lewes Ferry is a ferry system on the East Coast of the United States that traverses a crossing of the Delaware Bay connecting North Cape May, New Jersey with Lewes, Delaware. The ferry constitutes a portion of U.S. Route 9 and ...

in 1963, and renamed as the SS ''Delaware'', operating from 1964 to 1974

* The

* The ''Pocahontas

Pocahontas (, ; born Amonute, also known as Matoaka and Rebecca Rolfe; 1596 – March 1617) was a Native American woman belonging to the Powhatan people, notable for her association with the colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. S ...

'' – a passenger train of the Norfolk and Western Railway

The Norfolk and Western Railway , commonly called the N&W, was a US class I railroad, formed by more than 200 railroad mergers between 1838 and 1982. It was headquartered in Roanoke, Virginia, for most of its existence. Its motto was "Precisio ...

, running from Norfolk, Virginia to Cincinnati, Ohio

* The minor planet 4487 Pocahontas

See also

*La Malinche

Marina () or Malintzin (; 1500 – 1529), more popularly known as La Malinche (), was a Nahua woman from the Mexican Gulf Coast, who became known for contributing to the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire (1519–1521), by acting as an int ...

– a Nahua

The Nahuas ( ) are a Uto-Nahuan ethnicity and one of the Indigenous people of Mexico, with Nahua minorities also in El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. They comprise the largest Indigenous group in Mexico, as well as ...

woman from the Mexican Gulf Coast, who played a major role in the Spanish-Aztec War as an interpreter for the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca (December 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions o ...

* List of kidnappings

The following is a list of kidnappings summarizing the events of each case, including instances of celebrity abductions, claimed hoaxes, suspected kidnappings, extradition abductions, and mass kidnappings.

By date

* List of kidnappings befo ...

* Mary Kittamaquund

Mary Kittamaquund (c. 1634 – c. 1654 or 1700) was a Piscataway woman who played a role in the establishment of the Maryland colony. The daughter of the Piscataway chieftain Kittamaquund, she was sent by her father as an adoptee to be raised ...

– daughter of a Piscataway Piscataway may refer to:

*Maryland (place)

**Piscataway, Maryland, an unincorporated community

** Piscataway Creek, Maryland

** Piscataway Park, historical park at the mouth of Piscataway Creek

** Siege of Piscataway, siege of Susquehannock fort sou ...

chief in colonial Maryland

* Sedgeford Hall Portrait – once thought to represent Pocahontas and Thomas Rolfe but now believed to depict the wife (Pe-o-ka) and son of Seminole Chief Osceola

Osceola (1804 – January 30, 1838, Vsse Yvholv in Muscogee language, Creek, also spelled Asi-yahola), named Billy Powell at birth, was an influential leader of the Seminole people in Florida. His mother was Muscogee, and his great-grandfa ...

* The True Story of Pocahontas: The Other Side of History

References

Bibliography

* Argall, Samuel. Letter to Nicholas Hawes. June 1613. Repr. in ''Jamestown Narratives'', ed. Edward Wright Haile. Champlain, VA: Roundhouse, 1998. * Bulla, Clyde Robert. "Little Nantaquas." In ''Pocahontas and The Strangers'', ed Scholastic Inc., New York. 1971. * Custalow, Linwood "Little Bear" and Daniel, Angela L. "Silver Star." ''The True Story of Pocahontas'', Fulcrum Publishing, Golden, Colorado 2007, . * Dale, Thomas. Letter to 'D.M.' 1614. Repr. in ''Jamestown Narratives'', ed. Edward Wright Haile. Champlain, VA: Roundhouse, 1998. * Dale, Thomas. Letter to Sir Ralph Winwood. June 3, 1616. Repr. in ''Jamestown Narratives'', ed. Edward Wright Haile. Champlain, VA: Roundhouse, 1998. * Fausz, J. Frederick. "An 'Abundance of Blood Shed on Both Sides': England's First Indian War, 1609–1614". ''The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography'' 98:1 (January 1990), pp. 3–56. * Gleach, Frederic W. ''Powhatan's World and Colonial Virginia''. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997. * Hamor, Ralph. ''A True Discourse of the Present Estate of Virginia''. 1615. Repr. in ''Jamestown Narratives'', ed. Edward Wright Haile. Champlain, VA: Roundhouse, 1998. * Herford, C.H. and Percy Simpson, eds. ''Ben Jonson'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1925–1952). * Huber, Margaret Williamson (January 12, 2011)"Powhatan (d. 1618)"

Retrieved February 18, 2011. * Kupperman, Karen Ordahl. ''Indians and English: Facing Off in Early America''. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000. * Lemay, J.A. Leo. ''Did Pocahontas Save Captain John Smith?'' Athens, Georgia: The University of Georgia Press, 1992 * Price, David A. ''Love and Hate in Jamestown''. New York: Vintage, 2003. * Purchas, Samuel. ''Hakluytus Posthumus or Purchas His Pilgrimes''. 1625. Repr. Glasgow: James MacLehose, 1905–1907. vol. 19 * Rolfe, John. Letter to Thomas Dale. 1614. Repr. in ''Jamestown Narratives'', ed. Edward Wright Haile. Champlain, VA: Roundhouse, 1998 * Rolfe, John. Letter to Edwin Sandys. June 8, 1617

Repr. in ''The Records of the Virginia Company of London''

ed. Susan Myra Kingsbuy. Washington: US Government Printing Office, 1906–1935. Vol. 3 * Rountree, Helen C. (November 3, 2010)

"Divorce in Early Virginia Indian Society"

Retrieved February 18, 2011. * Rountree, Helen C. (November 3, 2010)

"Early Virginia Indian Education"

Retrieved February 27, 2011. * Rountree, Helen C. (November 3, 2010)

"Uses of Personal Names by Early Virginia Indians"

Retrieved February 18, 2011. * Rountree, Helen C. (December 8, 2010)

"Pocahontas (d. 1617)"

Retrieved February 18, 2011. * Smith, John

''A True Relation of such Occurrences and Accidents of Noate as hath Hapned in Virginia''

!---This is Smith's spelling, not a typo!--->, 1608. Repr. in ''The Complete Works of John Smith (1580–1631)''. Ed. Philip L. Barbour. Chapel Hill: University Press of Virginia, 1983. Vol. 1 * Smith, John.

A Map of Virginia

', 1612. Repr. in ''The Complete Works of John Smith (1580–1631)'', Ed. Philip L. Barbour. Chapel Hill: University Press of Virginia, 1983. Vol. 1 * Smith, John. Letter to Queen Anne. 1616. Repr. a

1997, Accessed April 23, 2006. * Smith, John. ''

The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles

''The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles'' (often abbreviated to ''The Generall Historie'') is a book written by Captain John Smith, first published in 1624. The book is one of the earliest, if not the earliest, hi ...

''. 1624. Repr. in ''Jamestown Narratives'', ed. Edward Wright Haile. Champlain, VA: Roundhouse, 1998.

* Spelman, Henry. ''A Relation of Virginia''. 1609. Repr. in ''Jamestown Narratives'', ed. Edward Wright Haile. Champlain, VA: Roundhouse, 1998.

* Strachey, William. ''The Historie of Travaile into Virginia Brittania''. c. 1612. Repr. London: Hakluyt Society

The Hakluyt Society is a text publication society, founded in 1846 and based in London, England, which publishes scholarly editions of primary records of historic voyages, travels and other geographical material. In addition to its publishin ...

, 1849.

* Symonds, William. ''The Proceedings of the English Colonie in Virginia''. 1612. Repr. in ''The Complete Works of Captain John Smith''. Ed. Philip L. Barbour. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986. Vol. 1

*

* Waldron, William Watson. ''Pocahontas, American Princess: and Other Poems''. New York: Dean and Trevett, 1841

* Warner, Charles Dudley. ''Captain John Smith'', 1881. Repr. iCaptain John Smith

Project Gutenberg Text, accessed July 4, 2006 * Woodward, Grace Steele. ''Pocahontas''. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1969.

Further reading

* Barbour, Philip L. ''Pocahontas and Her World''. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1970. * Neill, Rev. Edward D. ''Pocahontas and Her Companions''. Albany: Joel Munsell, 1869. * Price, David A. ''Love and Hate in Jamestown''. Alfred A. Knopf, 2003 * Rountree, Helen C. ''Pocahontas's People: The Powhatan Indians of Virginia Through Four Centuries''. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1990. * Strong, Pauline Turner. ''Animated Indians: Critique and Contradiction in Commodified Children's Culture''. Cultural Anthology, Vol. 11, No. 3 (Aug. 1996), pp. 405–424 * Sandall, Roger. 2001 ''The Culture Cult: Designer Tribalism and Other Essays'' * Townsend, Camilla. ''Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma''. New York: Hill and Wang, 2004. * Warner, Charles Dudley, ''Captain John Smith'', 1881. Repr. iCaptain John Smith

Project Gutenberg Text, accessed July 4, 2006 * Warner, Charles Dudley, ''The Story of Pocahontas'', 1881. Repr. i

The Story of Pocahontas

Project Gutenberg Text, accessed July 4, 2006 * Woodward, Grace Steele. ''Pocahontas''. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1969. or * * ''Pocahontas, Alias Matoaka, and Her Descendants Through Her Marriage at Jamestown, Virginia, in April 1614, with John Rolfe, Gentleman'', Wyndham Robertson, Printed by J. W. Randolph & English, Richmond, Va., 1887

External links

Pocahontas: Her Life and Legend

– National Park Service – Historic Jamestowne

''The Story of Virginia: An American Experience''. Virginia Historical Society.

''The Story of Virginia: An American Experience''. Virginia Historical Society.

''Virtual Jamestown''

Includes text of many original accounts

"The Pocahontas Archive"

a comprehensive bibliography of texts about Pocahontas

On this day in history: Pocahontas marries John Rolfe

History.com * Michals, Debra

"Pocahontas"

National Women's History Museum. 2015. {{DEFAULTSORT:Pocahontas 1590s births 1617 deaths 17th-century American people 17th-century American women 17th-century Native American people 17th-century Native American women Immigrants to the Kingdom of England Bolling family (Virginia) Converts to Protestantism from pagan religions Kidnapped American children Native American Christians Pamunkey people People from colonial Virginia People from Jamestown, Virginia People of the Powhatan Confederacy Rolfe family (Virginia)