Pietists on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pietism (), also known as Pietistic Lutheranism, is a movement within

In

In

The direct originator of the movement was Philipp Spener. Born at Rappoltsweiler in Alsace, now in France, on 13 January 1635, trained by a devout godmother who used books of devotion like Arndt's ''True Christianity'', Spener was convinced of the necessity of a moral and religious reformation within German Lutheranism. He studied theology at

The direct originator of the movement was Philipp Spener. Born at Rappoltsweiler in Alsace, now in France, on 13 January 1635, trained by a devout godmother who used books of devotion like Arndt's ''True Christianity'', Spener was convinced of the necessity of a moral and religious reformation within German Lutheranism. He studied theology at

In 1686 Spener accepted an appointment to the court-chaplaincy at

In 1686 Spener accepted an appointment to the court-chaplaincy at

As a distinct movement, Pietism had its greatest strength by the middle of the 18th century; its very individualism in fact helped to prepare the way for the Enlightenment (''Aufklärung''), which took the church in an altogether different direction. Yet some claim that Pietism contributed largely to the revival of Biblical studies in Germany and to making religion once more an affair of the heart and of life and not merely of the intellect.

It likewise gave a new emphasis to the role of the laity in the church. Rudolf Sohm claimed that "It was the last great surge of the waves of the ecclesiastical movement begun by the

As a distinct movement, Pietism had its greatest strength by the middle of the 18th century; its very individualism in fact helped to prepare the way for the Enlightenment (''Aufklärung''), which took the church in an altogether different direction. Yet some claim that Pietism contributed largely to the revival of Biblical studies in Germany and to making religion once more an affair of the heart and of life and not merely of the intellect.

It likewise gave a new emphasis to the role of the laity in the church. Rudolf Sohm claimed that "It was the last great surge of the waves of the ecclesiastical movement begun by the  In the middle of the 19th century,

In the middle of the 19th century,

online review

* Shantz, Douglas H. ''An Introduction to German Pietism: Protestant Renewal at the Dawn of Modern Europe''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013. * Stoeffler, F. Ernest. ''The Rise of Evangelical Pietism''. Studies in the History of Religion 9. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1965. * Stoeffler, F. Ernest. ''German Pietism During the Eighteenth Century''. Studies in the History of Religion 24. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1973. * Stoeffler, F. Ernest. ed.: ''Continental Pietism and Early American Christianity''. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1976. * Winn, Christian T. et al. eds. ''The Pietist Impulse in Christianity''. Pickwick, 2012. * Yoder, Peter James.

'' University Park: PSU Press, 2021.

Im Auftrag der Historischen Kommission zur Erforschung des Pietismus herausgegeben von Martin Brecht, Klaus Deppermann, Ulrich Gäbler und Hartmut Lehmann

(English: On behalf of the Historical Commission for the Study of pietism edited by Martin Brecht, Klaus Deppermann, Ulrich Gaebler and Hartmut Lehmann) ** ''Band 1:'' Der Pietismus vom siebzehnten bis zum frühen achtzehnten Jahrhundert. In Zusammenarbeit mit Johannes van den Berg, Klaus Deppermann, Johannes Friedrich Gerhard Goeters und Hans Schneider hg. von Martin Brecht. Goettingen 1993. / 584 p. ** ''Band 2:'' Der Pietismus im achtzehnten Jahrhundert. In Zusammenarbeit mit Friedhelm Ackva, Johannes van den Berg, Rudolf Dellsperger, Johann Friedrich Gerhard Goeters, Manfred Jakubowski-Tiessen, Pentii Laasonen, Dietrich Meyer, Ingun Montgomery, Christian Peters, A. Gregg Roeber, Hans Schneider, Patrick Streiff und Horst Weigelt hg. von Martin Brecht und Klaus Deppermann. Goettingen 1995. / 826 p. ** ''Band 3:'' Der Pietismus im neunzehnten und zwanzigsten Jahrhundert. In Zusammenarbeit mit Gustav Adolf Benrath, Eberhard Busch, Pavel Filipi, Arnd Götzelmann, Pentii Laasonen, Hartmut Lehmann, Mark A. Noll, Jörg Ohlemacher, Karl Rennstich und Horst Weigelt unter Mitwirkung von Martin Sallmann hg. von Ulrich Gäbler. Goettingen 2000. / 607 p. ** ''Band 4:'' Glaubenswelt und Lebenswelten des Pietismus. In Zusammenarbeit mit Ruth Albrecht, Martin Brecht, Christian Bunners, Ulrich Gäbler, Andreas Gestrich, Horst Gundlach, Jan Harasimovicz, Manfred Jakubowski-Tiessen, Peter Kriedtke, Martin Kruse, Werner Koch, Markus Matthias, Thomas Müller Bahlke, Gerhard Schäfer (†), Hans-Jürgen Schrader, Walter Sparn, Udo Sträter, Rudolf von Thadden, Richard Trellner, Johannes Wallmann und Hermann Wellenreuther hg. von Hartmut Lehmann. Goettingen 2004. / 709 p.

New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, Vol. IX: Pietism

After Three Centuries – The Legacy of Pietism by E.C. Fredrich

Literary Landmarks of Pietism by Martin O. Westerhaus

Pietism's World Mission Enterprise by Ernst H. Wendland

Old Apostolic Lutheran Church of America

The Evangelical Pietist Church of Chatfield

{{Authority control Christian terminology Christian theological movements 17th-century Lutheranism 18th-century Lutheranism Laestadianism Lutheran revivals Lutheran theology Methodism

Lutheranism

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

that combines its emphasis on biblical doctrine with an emphasis on individual piety

Piety is a virtue which may include religious devotion or spirituality. A common element in most conceptions of piety is a duty of respect. In a religious context, piety may be expressed through pious activities or devotions, which may vary amon ...

and living a holy Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

life.

Although the movement is aligned with Lutheranism, it has had a tremendous impact on Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

worldwide, particularly in North America and Europe. Pietism originated in modern Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

in the late 17th century with the work of Philipp Spener, a Lutheran theologian whose emphasis on personal transformation through spiritual rebirth and renewal, individual devotion, and piety laid the foundations for the movement. Although Spener did not directly advocate the quietistic, legalistic, and semi-separatist practices of Pietism, they were more or less involved in the positions he assumed or the practices which he encouraged.

Pietism spread from Germany to Switzerland, the rest of German-speaking Europe, and to Scandinavia and the Baltics, where it was heavily influential, leaving a permanent mark on the region's dominant Lutheranism, with figures like Hans Nielsen Hauge

Hans Nielsen Hauge (3 April 1771 – 29 March 1824) was a 19th-century Norwegian Lutheran lay minister, spiritual leader, business entrepreneur, social reformer and author. He led a noted Pietism revival known as the Haugean movement. Hauge is al ...

in Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

, Peter Spaak and Carl Olof Rosenius in Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

, Katarina Asplund in Finland

Finland, officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It borders Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bothnia to the west and the Gulf of Finland to the south, ...

, and Barbara von Krüdener in the Baltics, and to the rest of Europe. It was further taken to North America, primarily by German and Scandinavian immigrants. There, it influenced Protestants of other ethnic and other (non-Lutheran) denominational backgrounds, contributing to the 18th-century foundation of evangelicalism

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

, an interdenominational

Ecumenism ( ; alternatively spelled oecumenism)also called interdenominationalism, or ecumenicalismis the concept and principle that Christians who belong to different Christian denominations should work together to develop closer relationships ...

movement within Protestantism that today has some 300 million followers.

In the middle of the 19th century, Lars Levi Laestadius

Lars Levi Laestadius (; 10 January 1800 – 21 February 1861) was a Swedish Sami writer, ecologist, mythologist, and ethnographer as well as a pastor and administrator of the Swedish state Lutheran church in Lapland who founded the Laestadi ...

spearheaded a Pietist revival in Scandinavia that upheld what came to be known as Laestadian Lutheran theology, which is adhered to today by the Laestadian Lutheran Churches as well as by several congregations within other mainstream Lutheran Churches, such as the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland

The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland (; ) is a national church of Finland. It is part of the Lutheranism, Lutheran branch of Christianity. The church has a legal position as a national church in the country, along with the Orthodox Church o ...

. The Eielsen Synod and Association of Free Lutheran Congregations are Pietist Lutheran bodies that emerged in the Pietist Lutheran movement in Norway, which was spearheaded by Hans Nielsen Hauge

Hans Nielsen Hauge (3 April 1771 – 29 March 1824) was a 19th-century Norwegian Lutheran lay minister, spiritual leader, business entrepreneur, social reformer and author. He led a noted Pietism revival known as the Haugean movement. Hauge is al ...

. In 1900, the Church of the Lutheran Brethren was founded and it adheres to Pietist Lutheran theology, emphasizing a personal conversion experience. The Ethiopian Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus, a Lutheran denomination with a largely Pietistic following with some Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

and Pentecostal

Pentecostalism or classical Pentecostalism is a movement within the broader Evangelical wing of Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes direct personal experience of God in Christianity, God through Baptism with the Holy Spirit#Cl ...

influence and primarily based in Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

and among the Ethiopian diaspora

There are over 2.5 million Ethiopians abroad, primarily inhabited in North America, Europe, the Middle East and Australia. In U.S, there are 250,000 to one million diaspora and 16,347 in the Netherlands according to the Dutch Central Statistics ...

, is the largest individual member Lutheran denomination within the Lutheran World Federation

The Lutheran World Federation (LWF; ) is a global Communion (religion), communion of national and regional Lutheran denominations headquartered in the Ecumenical Centre in Geneva, Switzerland. The federation was founded in the Swedish city of L ...

.

Whereas Pietistic Lutherans stayed within the Lutheran tradition, adherents of a related movement known as Radical Pietism

Radical Pietism are those Ecclesiastical separatism, Christian churches who decided to break with denominational Lutheranism in order to emphasize certain teachings regarding holy living. Radical Pietists contrast with Church Pietists, who chose t ...

believed in separating from the established Lutheran Churches. Some of the theological tenets of Pietism also influenced other traditions of Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

, inspiring the Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

priest John Wesley

John Wesley ( ; 2 March 1791) was an English cleric, Christian theology, theologian, and Evangelism, evangelist who was a principal leader of a Christian revival, revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism. The societies ...

to begin the Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a Protestant Christianity, Christian Christian tradition, tradition whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother ...

movement and Alexander Mack

Alexander Mack ( 27 July 1679 – 19 January 1735) was a German clergyman and the leader and first Minister (Christianity), minister of the Schwarzenau Brethren (or Schwarzenau Brethren, German Baptists) in the Schwarzenau, Kreis Siegen-Wi ...

to begin the Anabaptist

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek language, Greek : 're-' and 'baptism'; , earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. ...

Schwarzenau Brethren

The Schwarzenau Brethren, the German Baptist Brethren, Dunkers, Dunkard Brethren, Tunkers, or sometimes simply called the German Baptists, are an Anabaptist group that dissented from Roman Catholic, Lutheran and Reformed European state churches ...

movement.

The word ''pietism'' (in lower case spelling) is also used to refer to an "emphasis on devotional experience and practices", or an "affectation of devotion", "pious sentiment, especially of an exaggerated or affected nature", not necessarily connected with Lutheranism or even Christianity.

Beliefs

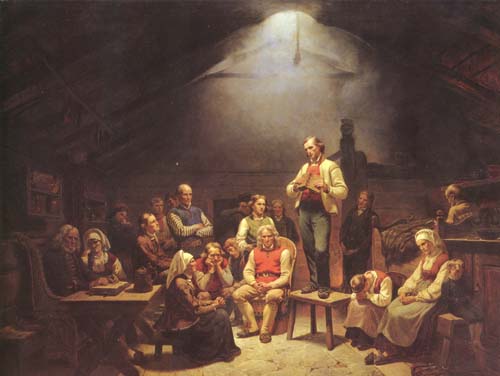

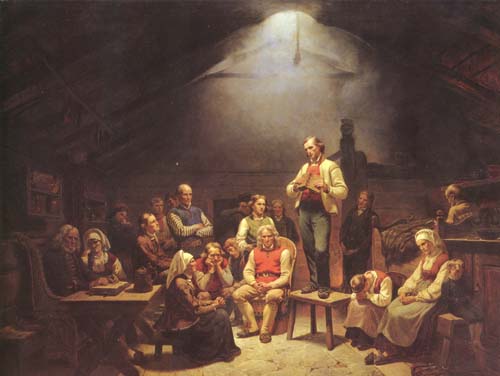

Pietistic Lutherans meet together inconventicle

A conventicle originally meant "an assembly" and was frequently used by ancient writers to mean "a church." At a semantic level, ''conventicle'' is a Latinized synonym of the Greek word for ''church'', and references Jesus' promise in Matthew 18: ...

s, "apart from Divine Service in order to mutually encourage piety". They believe "that any true Christian could point back in his or her life to an inner struggle with sin that culminated in a crisis and ultimately a decision to start a new, Christ-centered life." Pietistic Lutherans emphasize following "biblical divine commands of believers to live a holy life and to strive for holy living, or sanctification

Sacred describes something that is dedicated or set apart for the service or worship of a deity; is considered worthy of spiritual respect or devotion; or inspires awe or reverence among believers. The property is often ascribed to objects ( ...

".

By country

Germany

Pietism did not die out in the 18th century, but was alive and active in the American (German Evangelical Church Society of the West, based in Gravois, Missouri, later German Evangelical Synod of North America and still later theEvangelical and Reformed Church

The Evangelical and Reformed Church (E&R) was a Protestant Christian denomination in the United States. It was formed in 1934 by the merger of the Reformed Church in the United States (RCUS) with the Evangelical Synod of North America (ESNA). ...

, a precursor of the United Church of Christ

The United Church of Christ (UCC) is a socially liberal mainline Protestant Christian denomination based in the United States, with historical and confessional roots in the Congregational, Restorationist, Continental Reformed, and Lutheran t ...

.) The church president from 1901 to 1914 was a pietist named Jakob Pister. Some vestiges of Pietism were still present in 1957 at the time of the formation of the United Church of Christ. In the 21st century Pietism is still alive in groups inside the Evangelical Church in Germany

The Evangelical Church in Germany (, EKD), also known as the Protestant Church in Germany, is a federation of twenty Lutheranism, Lutheran, Continental Reformed Protestantism, Reformed, and united and uniting churches, United Protestantism in Ger ...

. These groups are called and emerged in the second half of the 19th century in the so-called .

The 19th century saw a revival of confessional Lutheran doctrine, known as the neo-Lutheran movement. This movement focused on a reassertion of the identity of Lutherans as a distinct group within the broader community of Christians

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the world. The words '' Christ'' and ''C ...

, with a renewed focus on the Lutheran Confessions as a key source of Lutheran doctrine. Associated with these changes was a renewed focus on traditional doctrine and liturgy, which paralleled the growth of Anglo-Catholicism

Anglo-Catholicism comprises beliefs and practices that emphasise the Catholicism, Catholic heritage (especially pre-English Reformation, Reformation roots) and identity of the Church of England and various churches within Anglicanism. Anglo-Ca ...

in England.

Scandinavia

Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

, Pietistic Lutheranism became popular in 1703. There, the faithful were organized into conventicles

A conventicle originally meant "an assembly" and was frequently used by ancient writers to mean "a church." At a semantic level, ''conventicle'' is a Latinized synonym of the Greek word for ''church'', and references Jesus' promise in Matthew 18: ...

that "met for prayer and Bible reading".

Pietistic Lutheranism entered Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

in the 1600s after the writings of Johann Arndt, Philipp Jakob Spener, and August Hermann Francke became popular. Pietistic Lutheranism gained patronage under Archbishop Erik Benzelius, who encouraged the Pietistic Lutheran practices.

Laestadian Lutheranism, a form of Pietistic Lutheranism, continues to flourish in Scandinavia, where Church of Sweden

The Church of Sweden () is an Evangelical Lutheran national church in Sweden. A former state church, headquartered in Uppsala, with around 5.5 million members at year end 2023, it is the largest Christian denomination in Sweden, the largest List ...

priest Lars Levi Laestadius

Lars Levi Laestadius (; 10 January 1800 – 21 February 1861) was a Swedish Sami writer, ecologist, mythologist, and ethnographer as well as a pastor and administrator of the Swedish state Lutheran church in Lapland who founded the Laestadi ...

spearheaded the revival in the 19th century.

History

Forerunners

As the forerunners of the Pietists in the strict sense, certain voices had been heard bewailing the shortcomings of the church and advocating a revival of practical and devout Christianity. Amongst them were the Christian mysticJakob Böhme

Jakob Böhme (; ; 24 April 1575 – 17 November 1624) was a German philosopher, Christian mysticism, Christian mystic, and Lutheran Protestant Theology, theologian. He was considered an original thinker by many of his contemporaries within the L ...

(Behmen); Johann Arndt, whose work, ''True Christianity'', became widely known and appreciated; Heinrich Müller, who described the font

In metal typesetting, a font is a particular size, weight and style of a ''typeface'', defined as the set of fonts that share an overall design.

For instance, the typeface Bauer Bodoni (shown in the figure) includes fonts " Roman" (or "regul ...

, the pulpit

A pulpit is a raised stand for preachers in a Christian church. The origin of the word is the Latin ''pulpitum'' (platform or staging). The traditional pulpit is raised well above the surrounding floor for audibility and visibility, accesse ...

, the confessional

A confessional is a box, cabinet, booth, or stall where the priest from some Christian denominations sits to hear the confessions of a penitent's sins. It is the traditional venue for the sacrament in the Roman Catholic Church and the Luther ...

, and the altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religion, religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, Church (building), churches, and other places of worship. They are use ...

as "the four dumb idols of the Lutheran Church"; the theologian Johann Valentin Andrea, court chaplain of the Landgrave of Hesse; Schuppius, who sought to restore the Bible to its place in the pulpit; and Theophilus Grossgebauer (d. 1661) of Rostock

Rostock (; Polabian language, Polabian: ''Roztoc''), officially the Hanseatic and University City of Rostock (), is the largest city in the German States of Germany, state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and lies in the Mecklenburgian part of the sta ...

, who from his pulpit and by his writings raised what he called "the alarm cry of a watchman in Sion".

Founding

The direct originator of the movement was Philipp Spener. Born at Rappoltsweiler in Alsace, now in France, on 13 January 1635, trained by a devout godmother who used books of devotion like Arndt's ''True Christianity'', Spener was convinced of the necessity of a moral and religious reformation within German Lutheranism. He studied theology at

The direct originator of the movement was Philipp Spener. Born at Rappoltsweiler in Alsace, now in France, on 13 January 1635, trained by a devout godmother who used books of devotion like Arndt's ''True Christianity'', Spener was convinced of the necessity of a moral and religious reformation within German Lutheranism. He studied theology at Strasbourg

Strasbourg ( , ; ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est Regions of France, region of Geography of France, eastern France, in the historic region of Alsace. It is the prefecture of the Bas-Rhin Departmen ...

, where the professors at the time (and especially Sebastian Schmidt) were more inclined to "practical" Christianity than to theological disputation. He afterwards spent a year in Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

, and was powerfully influenced by the strict moral life and rigid ecclesiastical discipline prevalent there, and also by the preaching and the piety of the Waldensian professor Antoine Leger and the converted Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

preacher Jean de Labadie.

During a stay in Tübingen

Tübingen (; ) is a traditional college town, university city in central Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is situated south of the state capital, Stuttgart, and developed on both sides of the Neckar and Ammer (Neckar), Ammer rivers. about one in ...

, Spener read Grossgebauer's ''Alarm Cry'', and in 1666 he entered upon his first pastoral charge at Frankfurt

Frankfurt am Main () is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 773,068 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the List of cities in Germany by population, fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located in the forela ...

with a profound opinion that the Christian life within Evangelical Lutheranism was being sacrificed to zeal for rigid Lutheran orthodoxy. Pietism, as a distinct movement in the German Church, began with religious meetings at Spener's house (''collegia pietatis'') where he repeated his sermons, expounded passages of the New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

, and induced those present to join in conversation on religious questions. In 1675, Spener published his ''Pia desideria'' or ''Earnest Desire for a Reform of the True Evangelical Church'', the title giving rise to the term "Pietists". This was originally a pejorative term given to the adherents of the movement by its enemies as a form of ridicule, like that of "Methodists" somewhat later in England.

In ''Pia desideria'', Spener made six proposals as the best means of restoring the life of the church:

# The earnest and thorough study of the Bible in private meetings, ''ecclesiolae in ecclesia'' ("little churches within the church")

# The Christian priesthood being universal, the laity should share in the spiritual government of the church

# A knowledge of Christianity must be attended by the practice of it as its indispensable sign and supplement

# Instead of merely didactic, and often bitter, attacks on the heterodox and unbelievers, a sympathetic and kindly treatment of them

# A reorganization of the theological training of the universities, giving more prominence to the devotional life

# A different style of preaching, namely, in the place of pleasing rhetoric, the implanting of Christianity in the inner or new man, the soul of which is faith, and its effects the fruits of life

This work produced a great impression throughout Germany. While large numbers of orthodox Lutheran theologians and pastors were deeply offended by Spener's book, many other pastors immediately adopted Spener's proposals.

Early leaders

In 1686 Spener accepted an appointment to the court-chaplaincy at

In 1686 Spener accepted an appointment to the court-chaplaincy at Dresden

Dresden (; ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; , ) is the capital city of the States of Germany, German state of Saxony and its second most populous city after Leipzig. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, 12th most p ...

, which opened to him a wider though more difficult sphere of labor. In Leipzig

Leipzig (, ; ; Upper Saxon: ; ) is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Saxony. The city has a population of 628,718 inhabitants as of 2023. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, eighth-largest city in Ge ...

, a society of young theologians was formed under his influence for the learned study and devout application of the Bible. Three magistrates belonging to that society, one of whom was August Hermann Francke

August Hermann Francke (; 22 March 1663 – 8 June 1727) was a German Lutheran clergyman, theologian, philanthropist, and Biblical scholar. His evangelistic fervour and pietism got him expelled as lecturer from the universities of Dresden and ...

, subsequently the founder of the famous orphanage at Halle (1695), commenced courses of expository lectures on the Scriptures of a practical and devotional character, and in the German language

German (, ) is a West Germanic language in the Indo-European language family, mainly spoken in Western Europe, Western and Central Europe. It is the majority and Official language, official (or co-official) language in Germany, Austria, Switze ...

, which were zealously frequented by both students and townsmen. The lectures aroused the ill-will of the other theologians and pastors of Leipzig, and Francke and his friends left the city, and with the aid of Christian Thomasius

Christian Thomasius (; 1 January 1655 – 23 September 1728) was a German jurist and philosopher.

Biography

He was born in Leipzig and was educated by his father, Jakob Thomasius (1622–1684), at that time a junior lecturer in Leipzig Univer ...

and Spener founded the new University of Halle

Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (), also referred to as MLU, is a public research university in the cities of Halle and Wittenberg. It is the largest and oldest university in the German state of Saxony-Anhalt. MLU offers German and i ...

. The theological chairs in the new university were filled in complete conformity with Spener's proposals. The main difference between the new Pietistic Lutheran school and the orthodox Lutherans arose from the Pietists' conception of Christianity as chiefly consisting in a change of heart and consequent holiness of life. Orthodox Lutherans rejected this viewpoint as a gross simplification, stressing the need for the church and for sound theological underpinnings.

Spener died in 1705, but the movement, guided by Francke and fertilized from Halle, spread through the whole of Middle and North Germany. Among its greatest achievements, apart from the philanthropic institutions founded at Halle, were the revival of the Moravian Church

The Moravian Church, or the Moravian Brethren ( or ), formally the (Latin: "Unity of the Brethren"), is one of the oldest Protestant denominations in Christianity, dating back to the Bohemian Reformation of the 15th century and the original ...

in 1727 by Count von Zinzendorf, formerly a pupil in Francke's School for Young Noblemen in Halle, and the establishment of Protestant missions. In particular, Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg (10 July 1682 – 23 February 1719) became the first Pietist missionary to India.

Spener stressed the necessity of a new birth and separation of Christians from the world (see Asceticism

Asceticism is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from worldly pleasures through self-discipline, self-imposed poverty, and simple living, often for the purpose of pursuing Spirituality, spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world ...

). Many Pietists maintained that the new birth always had to be preceded by agonies of repentance, and that only a regenerated theologian could teach theology. The whole school shunned all common worldly amusements, such as dancing, the theatre, and public games. Some believe this led to a new form of justification by works. Its ''ecclesiolae in ecclesia'' also weakened the power and meaning of church organization. These Pietistic attitudes caused a counter-movement at the beginning of the 18th century; one leader was Valentin Ernst Löscher, superintendent at Dresden.

Establishment reaction

Authorities within state-endorsed Churches were suspicious of pietist doctrine which they often viewed as a social danger, as it "seemed either to generate an excess of evangelical fervor and so disturb the public tranquility or to promote a mysticism so nebulous as to obscure the imperatives of morality. A movement which cultivated religious feeling almost as an end itself". While some pietists (such as Francis Magny) held that "mysticism and the moral law went together", for others (like his pupil Françoise-Louise de la Tour) "pietist mysticism did less to reinforce the moral law than to take its place… the principle of 'guidance by inner light' was often a signal to follow the most intense of her inner sentiments… the supremacy of feeling over reason". Religious authorities could bring pressure on pietists, such as when they brought some of Magny's followers before the localconsistory

Consistory is the anglicized form of the consistorium, a council of the closest advisors of the Roman emperors. It can also refer to:

*A papal consistory, a formal meeting of the Sacred College of Cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church

*Consistor ...

to answer questions about their unorthodox views or when they banished Magny from Vevey

Vevey (; ; ) is a town in Switzerland in the Vaud, canton of Vaud, on the north shore of Lake Leman, near Lausanne. The German name Vivis is no longer commonly used.

It was the seat of the Vevey (district), district of the same name until 200 ...

for heterodoxy in 1713. Likewise, pietism challenged the orthodoxy via new media and formats: Periodical journals gained importance versus the former pasquills and single thesis, traditional disputation

Disputation is a genre of literature involving two contenders who seek to establish a resolution to a problem or establish the superiority of something. An example of the latter is in Sumerian disputation poems.

In the scholastic system of e ...

was replaced by competitive debating, which tried to gain new knowledge instead of defending orthodox scholarship.

Hymnody

Later history

As a distinct movement, Pietism had its greatest strength by the middle of the 18th century; its very individualism in fact helped to prepare the way for the Enlightenment (''Aufklärung''), which took the church in an altogether different direction. Yet some claim that Pietism contributed largely to the revival of Biblical studies in Germany and to making religion once more an affair of the heart and of life and not merely of the intellect.

It likewise gave a new emphasis to the role of the laity in the church. Rudolf Sohm claimed that "It was the last great surge of the waves of the ecclesiastical movement begun by the

As a distinct movement, Pietism had its greatest strength by the middle of the 18th century; its very individualism in fact helped to prepare the way for the Enlightenment (''Aufklärung''), which took the church in an altogether different direction. Yet some claim that Pietism contributed largely to the revival of Biblical studies in Germany and to making religion once more an affair of the heart and of life and not merely of the intellect.

It likewise gave a new emphasis to the role of the laity in the church. Rudolf Sohm claimed that "It was the last great surge of the waves of the ecclesiastical movement begun by the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

; it was the completion and the final form of the Protestantism created by the Reformation. Then came a time when another intellectual power took possession of the minds of men." Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (; 4 February 1906 – 9 April 1945) was a German Lutheran pastor, neo-orthodox theologian and anti-Nazi dissident who was a key founding member of the Confessing Church. His writings on Christianity's role in the s ...

of the German Confessing Church

The Confessing Church (, ) was a movement within German Protestantism in Nazi Germany that arose in opposition to government-sponsored efforts to unify all of the Protestant churches into a single pro-Nazi German Evangelical Church. See dro ...

framed the same characterization in less positive terms when he called Pietism the last attempt to save Christianity as a religion: Given that for him religion was a negative term, more or less an opposite to revelation

Revelation, or divine revelation, is the disclosing of some form of Religious views on truth, truth or Knowledge#Religion, knowledge through communication with a deity (god) or other supernatural entity or entities in the view of religion and t ...

, this constitutes a rather scathing judgment. Bonhoeffer denounced the basic aim of Pietism, to produce a "desired piety" in a person, as unbiblical.

Pietism is considered the major influence that led to the creation of the " Evangelical Church of the Union" in Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

in 1817. The King of Prussia ordered the Lutheran and Reformed churches in Prussia to unite; they took the name "Evangelical" as a name both groups had previously identified with. This union movement spread through many German lands in the 1800s. Pietism, with its looser attitude toward confessional theology, had opened the churches to the possibility of uniting. The unification of the two branches of German Protestantism sparked the Schism of the Old Lutherans. Many Lutherans, called Old Lutherans

Old Lutherans were German Lutherans in the Kingdom of Prussia, especially in the Province of Silesia, who refused to join the Prussian Union of churches in the 1830s and 1840s. Prussia's king, Frederick William III, was determined to unify th ...

formed free church

A free church is any Christian denomination that is intrinsically separate from government (as opposed to a state church). A free church neither defines government policy, nor accept church theology or policy definitions from the government. A f ...

es or emigrated to the United States and Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

, where they formed bodies that would later become the Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod

The Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod (LCMS), also known as the Missouri Synod, is an orthodox, traditional confessional Lutheran Christian denomination, denomination in the United States. With 1.7 million members as of 2022 it is the second-l ...

and the Lutheran Church of Australia, respectively. (Many immigrants to America, who agreed with the union movement, formed German Evangelical Lutheran and Reformed congregations, later combined into the Evangelical Synod of North America, which is now a part of the United Church of Christ

The United Church of Christ (UCC) is a socially liberal mainline Protestant Christian denomination based in the United States, with historical and confessional roots in the Congregational, Restorationist, Continental Reformed, and Lutheran t ...

.)

In the middle of the 19th century,

In the middle of the 19th century, Lars Levi Laestadius

Lars Levi Laestadius (; 10 January 1800 – 21 February 1861) was a Swedish Sami writer, ecologist, mythologist, and ethnographer as well as a pastor and administrator of the Swedish state Lutheran church in Lapland who founded the Laestadi ...

spearheaded a Pietist revival in Scandinavia that upheld what came to be known as Laestadian Lutheran theology, which is heralded today by the Laestadian Lutheran Church as well as by several congregations within mainstream Lutheran Churches, such as the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland

The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland (; ) is a national church of Finland. It is part of the Lutheranism, Lutheran branch of Christianity. The church has a legal position as a national church in the country, along with the Orthodox Church o ...

and the Church of Sweden

The Church of Sweden () is an Evangelical Lutheran national church in Sweden. A former state church, headquartered in Uppsala, with around 5.5 million members at year end 2023, it is the largest Christian denomination in Sweden, the largest List ...

. After encountering a Sami

Acronyms

* SAMI, ''Synchronized Accessible Media Interchange'', a closed-captioning format developed by Microsoft

* Saudi Arabian Military Industries, a government-owned defence company

* South African Malaria Initiative, a virtual expertise ne ...

woman who experienced a conversion, Laestadius had a similar experience that "transformed his life and defined his calling". As such, Laestadius "spend the rest of his life advancing his idea of Lutheran pietism, focusing his energies on marginalized groups in the northernmost regions of the Nordic countries". Laestadius called on his followers to embrace their Lutheran identity and as a result, Laestadian Lutherans have remained a part of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland

The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland (; ) is a national church of Finland. It is part of the Lutheranism, Lutheran branch of Christianity. The church has a legal position as a national church in the country, along with the Orthodox Church o ...

, the national Church

A national church is a Christian church associated with a specific ethnic group or nation state. The idea was notably discussed during the 19th century, during the emergence of modern nationalism.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, in a draft discussing ...

in that country, with some Laestadian Lutherans being consecrated as bishop

A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of Episcopal polity, authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of di ...

s. In the United States, Laestadian Lutheran Churches were formed for Laestadian Pietists. Laestadian Lutherans observe the Lutheran sacraments, holding classical Lutheran theology on infant baptism

Infant baptism, also known as christening or paedobaptism, is a Christian sacramental practice of Baptism, baptizing infants and young children. Such practice is done in the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches, va ...

and the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist

The real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, sometimes shortened Real Presence'','' is the Christian doctrine that Jesus Christ is present in the Eucharist, not merely symbolically or metaphorically, but in a true, real and substantial way.

T ...

, and also heavily emphasize Confession

A confession is a statement – made by a person or by a group of people – acknowledging some personal fact that the person (or the group) would ostensibly prefer to keep hidden. The term presumes that the speaker is providing information that ...

. Uniquely, Laestadian Lutherans "discourage watching television, attending movies, dancing, playing card games or games of chance, and drinking alcoholic beverages", as well as avoiding birth control – Laestadian Lutheran families usually have four to ten children. Laestadian Lutherans gather in a central location for weeks at a time for summer revival services in which many young adults find their future spouses.

R. J. Hollingdale, who translated Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philology, classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche bec ...

's '' Thus Spake Zarathustra'' into English, argued that a number of the themes of the work (especially ''amor fati

is a Latin phrase that may be translated as "love of fate" or "love of one's fate". It is used to describe an attitude in which one sees everything that happens in one's life, including suffering and loss, as good or, at the very least, necessa ...

'') originated in the Lutheran Pietism of Nietzsche's childhood – Nietzsche's father, Carl Ludwig Nietzsche, was a Lutheran pastor who supported the Pietist movement.

In 1900, the Church of the Lutheran Brethren was founded and it adheres to Pietist Lutheran theology, emphasizing a personal conversion experience.

Pietistic Lutheran denominations

Pietistic Lutheranism influenced existing Lutheran denominations such as theChurch of Norway

The Church of Norway (, , , ) is an Lutheranism, evangelical Lutheran denomination of Protestant Christianity and by far the largest Christian church in Norway. Christianity became the state religion of Norway around 1020, and was established a ...

and many Pietistic Lutherans have remained in them, though other Pietistic Lutherans have established their own Synods too. In the middle of the 19th century, Lars Levi Laestadius

Lars Levi Laestadius (; 10 January 1800 – 21 February 1861) was a Swedish Sami writer, ecologist, mythologist, and ethnographer as well as a pastor and administrator of the Swedish state Lutheran church in Lapland who founded the Laestadi ...

spearheaded a Pietist revival in Scandinavia that upheld what came to be known as Laestadian Lutheran theology, which is adhered to today by the Laestadian Lutheran Churches as well as by several congregations within other mainstream Lutheran Churches, such as the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland

The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland (; ) is a national church of Finland. It is part of the Lutheranism, Lutheran branch of Christianity. The church has a legal position as a national church in the country, along with the Orthodox Church o ...

. The Eielsen Synod and Association of Free Lutheran Congregations are Pietist Lutheran bodies that emerged in the Pietist Lutheran movement in Norway, which was spearheaded by Hans Nielsen Hauge

Hans Nielsen Hauge (3 April 1771 – 29 March 1824) was a 19th-century Norwegian Lutheran lay minister, spiritual leader, business entrepreneur, social reformer and author. He led a noted Pietism revival known as the Haugean movement. Hauge is al ...

. In 1900, the Church of the Lutheran Brethren was founded and it adheres to Pietist Lutheran theology, emphasizing a personal conversion experience.

Cross-denominational influence

Radical Pietism

Radical Pietism are thoseChristian Churches

In ecclesiology, the Christian Church is what different Christian denominations conceive of as being the true body of Christians or the original institution established by Jesus Christ. "Christian Church" has also been used in academia as a syn ...

who decided to break with denominational Lutheranism

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

in order to emphasize certain teachings regarding holy living. Churches in the Radical Pietist movement include the Mennonite Brethren Church

The Mennonite Brethren Church is an evangelical Mennonite Anabaptist movement with congregations.

History

The conference was established among Plautdietsch-speaking Russian Mennonites in 1860. During the 1850s, some Mennonites were influenced by ...

, Community of True Inspiration

The Community of True Inspiration, also known as the True Inspiration Congregations, Inspirationalists, and the Amana Church Society) is a Radical Pietist group of Christians descending from settlers of German, Swiss, and Austrian descent who se ...

(Inspirationalists), the Baptist General Conference

Converge, formerly the Baptist General Conference (BGC) and Converge Worldwide, is a Baptist Christian denomination in the United States. It is affiliated with the Baptist World Alliance and the National Association of Evangelicals. The headquart ...

, members of the International Federation of Free Evangelical Churches

International Federation of Free Evangelical Churches (IFFEC) is an international federation of evangelical free churches that trace their roots to the Radical Pietist movement (which split off/diverged from Pietistic Lutheranism). The member f ...

(such as the Evangelical Covenant Church

The Evangelical Covenant Church (ECC) is an evangelical denomination with Pietism, Pietist Lutheran roots. The Christian denomination, denomination has 129,015 members in 878 congregations and an average worship attendance of 219,000 people in th ...

and the Evangelical Free Church

The Evangelical Free Church of America (EFCA) is an evangelical Christian denomination in the Radical Pietistic tradition. The EFCA was formed in 1950 from the merger of the Swedish Evangelical Free Church and the Norwegian-Danish Evangelical F ...

), the Templers, the River Brethren

The River Brethren are a group of historically related Anabaptist Christian denominations originating in 1770, during the Radical Pietist movement among German colonists in Pennsylvania. In the 17th century, Mennonite refugees from Switzerl ...

(inclusive of the Brethren in Christ Church, the Calvary Holiness Church, the Old Order River Brethren and the United Zion Church), as well as the Schwarzenau Brethren

The Schwarzenau Brethren, the German Baptist Brethren, Dunkers, Dunkard Brethren, Tunkers, or sometimes simply called the German Baptists, are an Anabaptist group that dissented from Roman Catholic, Lutheran and Reformed European state churches ...

(that include Old Order groups such as the Old Brethren German Baptist, Conservative groups such as the Dunkard Brethren Church

The Dunkard Brethren Church is a Conservative Anabaptist denomination of the Schwarzenau Brethren tradition, which organized in 1926 when they withdrew from the Church of the Brethren in the United States.

The Dunkard Brethren Church observes ...

, and mainline groups such as the Church of the Brethren

The Church of the Brethren is an Anabaptist Christian denomination in the Schwarzenau Brethren tradition ( "Schwarzenau New Baptists") that was organized in 1708 by Alexander Mack in Schwarzenau, Germany during the Radical Pietist revival. ...

).

Influence on the Methodists

As with Moravianism, Pietism was a major influence onJohn Wesley

John Wesley ( ; 2 March 1791) was an English cleric, Christian theology, theologian, and Evangelism, evangelist who was a principal leader of a Christian revival, revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism. The societies ...

and others who began the Methodist movement

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a Protestant Christian tradition whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother Charles Wesley were also significa ...

in 18th-century Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

. John Wesley was influenced significantly by Moravians

Moravians ( or Colloquialism, colloquially , outdated ) are a West Slavs, West Slavic ethnic group from the Moravia region of the Czech Republic, who speak the Moravian dialects of Czech language, Czech or Czech language#Common Czech, Common ...

(e.g., Zinzendorf, Peter Boehler) and Pietists connected to Francke and Halle Pietism. The fruit of these Pietist influences can be seen in the modern American Methodists, especially those who are aligned with the Holiness movement

The Holiness movement is a Christianity, Christian movement that emerged chiefly within 19th-century Methodism, and to a lesser extent influenced other traditions such as Quakers, Quakerism, Anabaptism, and Restorationism. Churches aligned with ...

.

Influence on religion in America

Pietism had an influence on religion in America, as many German immigrants settled in Pennsylvania, New York, and other areas. Its influence can be traced in certain sectors ofEvangelicalism

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

. Balmer says that:

Evangelicalism itself, I believe, is a quintessentially North American phenomenon, deriving as it did from the confluence of Pietism,Presbyterianism Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ..., and the vestiges ofPuritanism The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should .... Evangelicalism picked up the peculiar characteristics from each strain – warmhearted spirituality from the Pietists (for instance), doctrinal precisionism from the Presbyterians, and individualistic introspection from the Puritans – even as the North American context itself has profoundly shaped the various manifestations of evangelicalism: fundamentalism, neo-evangelicalism, the holiness movement, Pentecostalism, thecharismatic movement The charismatic movement in Christianity is a movement within established or mainstream denominations to adopt beliefs and practices of Charismatic Christianity, with an emphasis on baptism with the Holy Spirit, and the use of spiritual gift ..., and various forms of African-American and Hispanic evangelicalism.

Influence on science

The Merton Thesis is an argument about the nature of earlyexperimental science

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome occurs when ...

proposed by Robert K. Merton. Similar to Max Weber

Maximilian Carl Emil Weber (; ; 21 April 186414 June 1920) was a German Sociology, sociologist, historian, jurist, and political economy, political economist who was one of the central figures in the development of sociology and the social sc ...

's famous claim on the link between Protestant ethic and the capitalist economy

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by a n ...

, Merton argued for a similar positive correlation

In statistics, correlation or dependence is any statistical relationship, whether causal or not, between two random variables or bivariate data. Although in the broadest sense, "correlation" may indicate any type of association, in statistics ...

between the rise of Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

Pietism and early experimental science.Sztompka, 2003 The Merton Thesis has resulted in continuous debates.Cohen, 1990

Impact on party voting in United States and Great Britain

In the United States, Richard L. McCormick says, "In the nineteenth century voters whose religious heritage was pietistic or evangelical were prone to support the Whigs and, later, the Republicans." Paul Kleppner generalizes, "the more pietistic the group's outlook the more intensely Republican its partisan affiliation." McCormick notes that the key link between religious values and politics resulted from the "urge of evangelicals and Pietists to 'reach out and purge the world of sin'". Pietism became influential among Scandinavian Lutherans; additionally it affected other denominations in the United States, such as the Northern Methodists, Northern Baptists,Congregationalists

Congregationalism (also Congregational Churches or Congregationalist Churches) is a Reformed Christian (Calvinist) tradition of Protestant Christianity in which churches practice congregational government. Each congregation independently a ...

, Presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

, Disciples of Christ

The Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) is a mainline Protestant Christian denomination in the United States and Canada. The denomination started with the Restoration Movement during the Second Great Awakening, first existing during the 19th ...

, and some smaller groups. The great majority were based in the northern states; some of these groups in the South would rather support the Democrats.

In England in the late 19th and early 20th century, the Nonconformist Protestant denominations, such as the Methodists, Baptists and Congregationalists, formed the base of the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

. David Hempton states, "The Liberal Party was the main beneficiary of Methodist political loyalties."

See also

*Amana Colonies

The Amana Colonies are seven villages on located in Iowa County in east-central Iowa, United States: Amana (or Main Amana, German: ''Haupt-Amana''), East Amana, High Amana, Middle Amana, South Amana, West Amana, and Homestead. The villag ...

* Adolf Köberle

* Catholic Charismatic Renewal

* Church of the Brethren

The Church of the Brethren is an Anabaptist Christian denomination in the Schwarzenau Brethren tradition ( "Schwarzenau New Baptists") that was organized in 1708 by Alexander Mack in Schwarzenau, Germany during the Radical Pietist revival. ...

* Erik Pontoppidan

* Evangelical Covenant Church

The Evangelical Covenant Church (ECC) is an evangelical denomination with Pietism, Pietist Lutheran roots. The Christian denomination, denomination has 129,015 members in 878 congregations and an average worship attendance of 219,000 people in th ...

* Evangelical Free Church of America

* Friedrich Christoph Oetinger

* Friedrich Hölderlin

Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin (, ; ; 20 March 1770 – 7 June 1843) was a Germans, German poet and philosopher. Described by Norbert von Hellingrath as "the most German of Germans", Hölderlin was a key figure of German Romanticis ...

* Johann Georg Rapp

* Hans Adolph Brorson

* Harmony Society

* Henric Schartau

* Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

* Knightly Piety Knightly Piety refers to a specific strand of Christian belief espoused by knights during the Middle Ages. The term comes from ''Ritterfrömmigkeit'', coined by Adolf Waas in his book ''Geschichte der Kreuzzüge''. Many scholars debate the importanc ...

* Johann Albrecht Bengel

* Johann Konrad Dippel

* Johannes Kelpius

* Mission Covenant Church of Sweden

* Templers (religious believers)

The German Templer Society, also known as Templers, is a Radical Pietist group that emerged in Germany during the mid-nineteenth century, the two founders, Christoph Hoffmann and Georg David Hardegg, arriving in Haifa, Palestine, in October 1868 ...

* '' Theologia Germanica''

* Wesleyanism

Wesleyan theology, otherwise known as Wesleyan–Arminian theology, or Methodist theology, is a theological tradition in Protestant Christianity based upon the ministry of the 18th-century evangelical reformer brothers John Wesley and Charles W ...

References

* See: "Six Principles of Pietism", based on Philip Jacob Spener's six proposals http://www.miamifirstbrethren.org/about-us * *Further reading

* Brown, Dale: ''Understanding Pietism'', rev. ed. Nappanee, IN: Evangel Publishing House, 1996. * Brunner, Daniel L. ''Halle Pietists in England: Anthony William Boehm and the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge''. Arbeiten zur Geschichte des Pietismus 29. Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, 1993. * Gehrz, Christopher and Mark Pattie III. ''The Pietist Option: Hope for the Renewal of Christianity''. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 2017. * Olson, Roger E., Christian T. Collins Winn. ''Reclaiming Pietism: Retrieving an Evangelical Tradition'' (Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2015). xiii + 190 pponline review

* Shantz, Douglas H. ''An Introduction to German Pietism: Protestant Renewal at the Dawn of Modern Europe''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013. * Stoeffler, F. Ernest. ''The Rise of Evangelical Pietism''. Studies in the History of Religion 9. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1965. * Stoeffler, F. Ernest. ''German Pietism During the Eighteenth Century''. Studies in the History of Religion 24. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1973. * Stoeffler, F. Ernest. ed.: ''Continental Pietism and Early American Christianity''. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1976. * Winn, Christian T. et al. eds. ''The Pietist Impulse in Christianity''. Pickwick, 2012. * Yoder, Peter James.

'' University Park: PSU Press, 2021.

Older works

* Joachim Feller, Sonnet. In: ''Luctuosa desideria Quibus'' ��''Martinum Bornium prosequebantur Quidam Patroni, Praeceptores atque Amici''. Lipsiae 689 pp. �� (Facsimile in: Reinhard Breymayer (Ed.): ''Luctuosa desideria''. Tübingen 2008, pp. 24–25.) Here for the first time the newly detected source. – Less exactly cf. Martin Brecht: ''Geschichte des Pietismus'', vol. I, p. 4. * Johann Georg Walch, ''Historische und theologische Einleitung in die Religionsstreitigkeiten der evangelisch-lutherischen Kirche'' (1730); * Friedrich August Tholuck, ''Geschichte des Pietismus und des ersten Stadiums der Aufklärung'' (1865); * Heinrich Schmid, ''Die Geschichte des Pietismus'' (1863); * Max Goebel, ''Geschichte des christlichen Lebens in der Rheinisch-Westfälischen Kirche'' (3 vols., 1849–1860). The subject is dealt with at length in * Isaak August Dorner's and W Gass's ''Histories of Protestant theology''. Other works are: * Heinrich Heppe, ''Geschichte des Pietismus und der Mystik in der reformierten Kirche'' (1879), which is sympathetic; * Albrecht Ritschl, ''Geschichte des Pietismus'' (5 vols., 1880–1886), which is hostile; and * Eugen Sachsse, ''Ursprung und Wesen des Pietismus'' (1884). See also * Friedrich Wilhelm Franz Nippold's article in ''Theol. Stud. und Kritiken'' (1882), pp. 347?392; * Hans von Schubert, ''Outlines of Church History'', ch. xv. (Eng. trans., 1907); and * Carl Mirbt's article, "Pietismus," in Herzog-Hauck's ''Realencyklopädie für prot. Theologie u. Kirche'', end of vol. xv. The most extensive and current edition on Pietism is the four-volume edition in German, covering the entire movement in Europe and North America * Geschichte des Pietismus (GdP)Im Auftrag der Historischen Kommission zur Erforschung des Pietismus herausgegeben von Martin Brecht, Klaus Deppermann, Ulrich Gäbler und Hartmut Lehmann

(English: On behalf of the Historical Commission for the Study of pietism edited by Martin Brecht, Klaus Deppermann, Ulrich Gaebler and Hartmut Lehmann) ** ''Band 1:'' Der Pietismus vom siebzehnten bis zum frühen achtzehnten Jahrhundert. In Zusammenarbeit mit Johannes van den Berg, Klaus Deppermann, Johannes Friedrich Gerhard Goeters und Hans Schneider hg. von Martin Brecht. Goettingen 1993. / 584 p. ** ''Band 2:'' Der Pietismus im achtzehnten Jahrhundert. In Zusammenarbeit mit Friedhelm Ackva, Johannes van den Berg, Rudolf Dellsperger, Johann Friedrich Gerhard Goeters, Manfred Jakubowski-Tiessen, Pentii Laasonen, Dietrich Meyer, Ingun Montgomery, Christian Peters, A. Gregg Roeber, Hans Schneider, Patrick Streiff und Horst Weigelt hg. von Martin Brecht und Klaus Deppermann. Goettingen 1995. / 826 p. ** ''Band 3:'' Der Pietismus im neunzehnten und zwanzigsten Jahrhundert. In Zusammenarbeit mit Gustav Adolf Benrath, Eberhard Busch, Pavel Filipi, Arnd Götzelmann, Pentii Laasonen, Hartmut Lehmann, Mark A. Noll, Jörg Ohlemacher, Karl Rennstich und Horst Weigelt unter Mitwirkung von Martin Sallmann hg. von Ulrich Gäbler. Goettingen 2000. / 607 p. ** ''Band 4:'' Glaubenswelt und Lebenswelten des Pietismus. In Zusammenarbeit mit Ruth Albrecht, Martin Brecht, Christian Bunners, Ulrich Gäbler, Andreas Gestrich, Horst Gundlach, Jan Harasimovicz, Manfred Jakubowski-Tiessen, Peter Kriedtke, Martin Kruse, Werner Koch, Markus Matthias, Thomas Müller Bahlke, Gerhard Schäfer (†), Hans-Jürgen Schrader, Walter Sparn, Udo Sträter, Rudolf von Thadden, Richard Trellner, Johannes Wallmann und Hermann Wellenreuther hg. von Hartmut Lehmann. Goettingen 2004. / 709 p.

External links

New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, Vol. IX: Pietism

After Three Centuries – The Legacy of Pietism by E.C. Fredrich

Literary Landmarks of Pietism by Martin O. Westerhaus

Pietism's World Mission Enterprise by Ernst H. Wendland

Old Apostolic Lutheran Church of America

The Evangelical Pietist Church of Chatfield

{{Authority control Christian terminology Christian theological movements 17th-century Lutheranism 18th-century Lutheranism Laestadianism Lutheran revivals Lutheran theology Methodism