Philolaos on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Philolaus (; , ''Philólaos''; )

was a Greek

Pythagoras and his earliest successors do not appear to have committed any of their doctrines to writing. According to Porphyrius (Vit. Pyth. p. 40)

Pythagoras and his earliest successors do not appear to have committed any of their doctrines to writing. According to Porphyrius (Vit. Pyth. p. 40)

Philolaus argued at the foundation of everything is the part played by the ideas of limit and the unlimited. One of the first declarations in the work of Philolaus was that all things in the universe result from a combination of the unlimited and the limiting; for if all things had been unlimited, nothing could have been the object of knowledge. Limiters and unlimiteds are combined in a harmony (''harmonia''):

Robert Scoon explained Philolaus' universe in 1922:

The book by Philolaus begins with the following:

According to Stobaeus, Philolaus did away with the ideas of fixed direction in space and developed one of the first non-geocentric views of the universe and in his new way of thinking, the universe revolved around a

Philolaus argued at the foundation of everything is the part played by the ideas of limit and the unlimited. One of the first declarations in the work of Philolaus was that all things in the universe result from a combination of the unlimited and the limiting; for if all things had been unlimited, nothing could have been the object of knowledge. Limiters and unlimiteds are combined in a harmony (''harmonia''):

Robert Scoon explained Philolaus' universe in 1922:

The book by Philolaus begins with the following:

According to Stobaeus, Philolaus did away with the ideas of fixed direction in space and developed one of the first non-geocentric views of the universe and in his new way of thinking, the universe revolved around a

The Counter-Earth

''. Osirus, vol. 11. Saint Catherines Press, 1954. p. 267-294 Nearly two-thousand years later,

Pythagorean

Pythagorean, meaning of or pertaining to the ancient Ionian mathematician, philosopher, and music theorist Pythagoras, may refer to:

Philosophy

* Pythagoreanism, the esoteric and metaphysical beliefs purported to have been held by Pythagoras

* Ne ...

and pre-Socratic

Pre-Socratic philosophy, also known as early Greek philosophy, is ancient Greek philosophy before Socrates. Pre-Socratic philosophers were mostly interested in cosmology, the beginning and the substance of the universe, but the inquiries of the ...

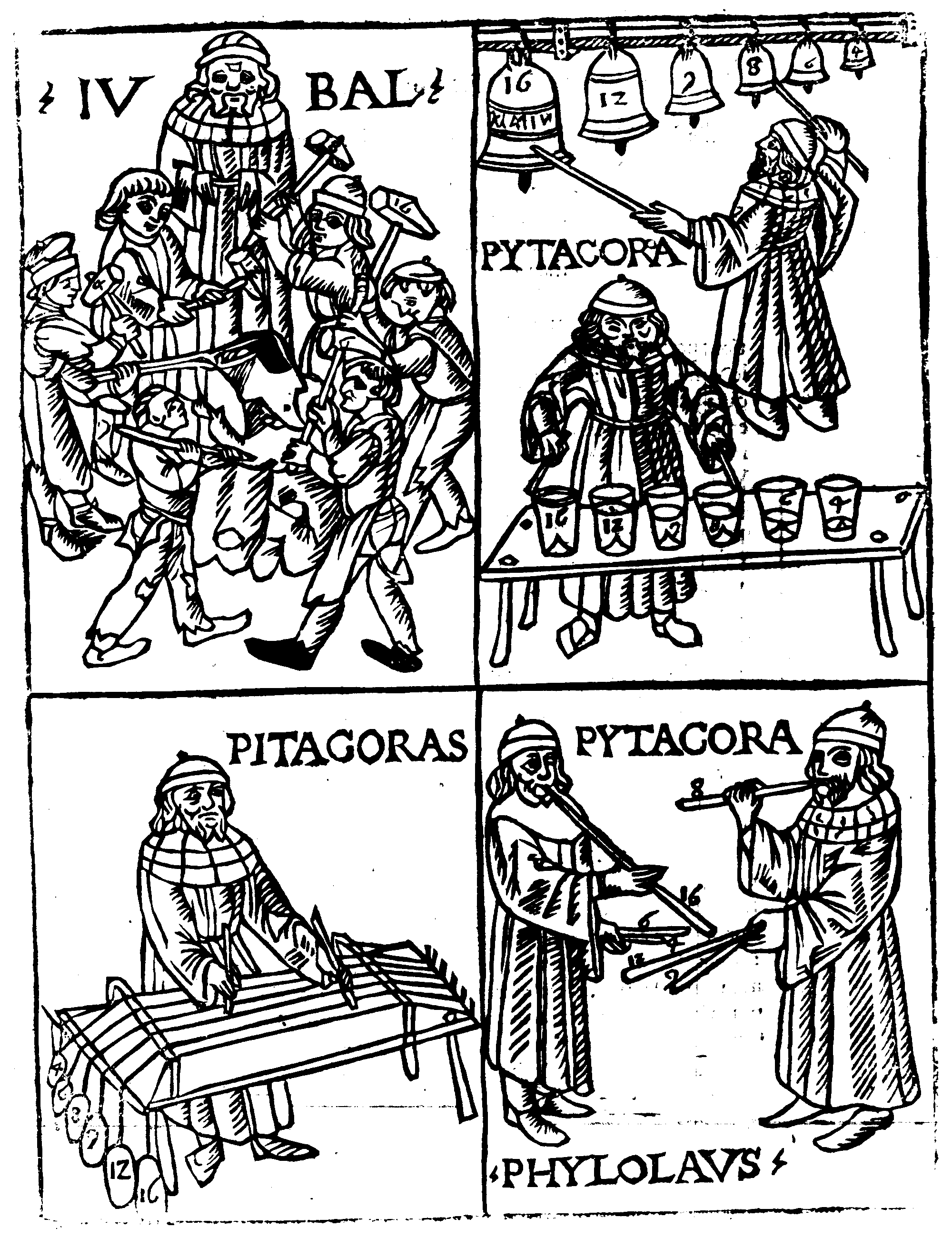

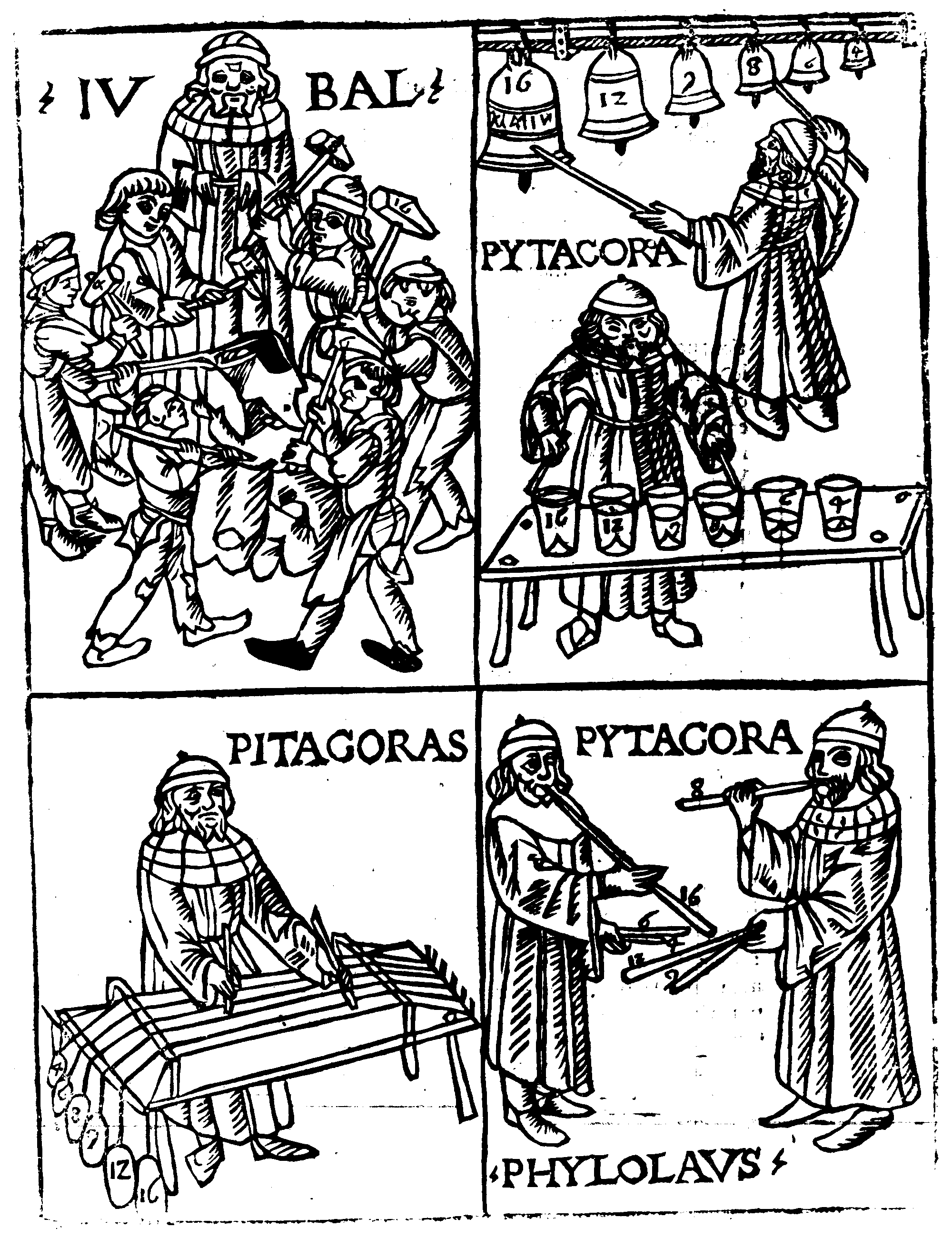

philosopher. He was born in a Greek colony in Italy and migrated to Greece. Philolaus has been called one of three most prominent figures in the Pythagorean tradition and the most outstanding figure in the Pythagorean school. Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos (; BC) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher, polymath, and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His political and religious teachings were well known in Magna Graecia and influenced the philosophies of P ...

developed a school of philosophy that was dominated by both mathematics and mysticism. Most of what is known today about the Pythagorean astronomical system is derived from Philolaus's views. He may have been the first to write about Pythagorean doctrine. According to , who cites Nicomachus

Nicomachus of Gerasa (; ) was an Ancient Greek Neopythagorean philosopher from Gerasa, in the Roman province of Syria (now Jerash, Jordan). Like many Pythagoreans, Nicomachus wrote about the mystical properties of numbers, best known for his ...

, Philolaus was the successor of Pythagoras.

He argued that at the foundation of everything is the part played by the limiting and limitless, which combine in a harmony. With his assertions that the Earth was not the center of the universe (geocentrism

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, a ...

), he is credited with the earliest known discussion of concepts in the development of heliocentrism

Heliocentrism (also known as the heliocentric model) is a superseded astronomical model in which the Earth and planets orbit around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed t ...

, the theory that the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

is not the center of the Universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents. It comprises all of existence, any fundamental interaction, physical process and physical constant, and therefore all forms of matter and energy, and the structures they form, from s ...

, but rather that the Sun is. Philolaus discussed a Central Fire

An astronomical system positing that the Earth, Moon, Sun, and planets revolve around an unseen "Central Fire" was developed in the fifth century BC and has been attributed to the Pythagorean philosopher Philolaus. The system has been called "the ...

as the center of the universe and that spheres (including the Sun) revolved around it.

Biography

Various reports give the birthplace of Philolaus as either Croton, Tarentum, orMetapontum

Metapontum or Metapontium () was an ancient city of Magna Graecia, situated on the gulf of Taranto, Tarentum, between the river Bradanus and the Casuentus (modern Basento). It was distant about 20 km from Heraclea (Lucania), Heraclea and 40 ...

—all part of Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia refers to the Greek-speaking areas of southern Italy, encompassing the modern Regions of Italy, Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania, and Sicily. These regions were Greek colonisation, extensively settled by G ...

(the name of the coastal areas of Southern Italy

Southern Italy (, , or , ; ; ), also known as () or (; ; ; ), is a macroregion of Italy consisting of its southern Regions of Italy, regions.

The term "" today mostly refers to the regions that are associated with the people, lands or cultu ...

on the Tarentine Gulf that were colonized

475px, Map of the year each country achieved List of sovereign states by date of formation, independence.

Colonization (British English: colonisation) is a process of establishing occupation of or control over foreign territories or peoples f ...

extensively by Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

settlers). It is most likely that he came from Croton. He migrated to Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

, perhaps while fleeing the second burning of the Pythagorean meeting-place around 454 BC.

According to Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

's ''Phaedo

''Phaedo'' (; , ''Phaidōn'') is a dialogue written by Plato, in which Socrates discusses the immortality of the soul and the nature of the afterlife with his friends in the hours leading up to his death. Socrates explores various arguments fo ...

'', he was the instructor of Simmias and Cebes

Cebes of Thebes (, ''gen''.: Κέβητος; Debra Nails, (2002), ''The people of Plato: a prosopography of Plato and other Socratics'', page 82.) was an Ancient Greek philosopher from Thebes remembered as a disciple of Socrates.

Life

Cebes was a ...

at Thebes Thebes or Thebae may refer to one of the following places:

*Thebes, Egypt, capital of Egypt under the 11th, early 12th, 17th and early 18th Dynasties

*Thebes, Greece, a city in Boeotia

*Phthiotic Thebes

Phthiotic Thebes ( or Φθιώτιδες Θ ...

, around the time the ''Phaedo'' takes place, in 399 BC. That would make him a contemporary of Socrates

Socrates (; ; – 399 BC) was a Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher from Classical Athens, Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and as among the first moral philosophers of the Ethics, ethical tradition ...

, and would agree with the statement that Philolaus and Democritus

Democritus (, ; , ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, Thrace, Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an ...

were contemporaries.

The writings of much later writers are the sources of further reports about his life. They are scattered and of dubious value in reconstructing his life. Apparently, he lived for some time at Heraclea, where he was the pupil of Aresas

Aresas () of Lucania, and probably of Croton in Magna Graecia, was the head of the Pythagorean school, and the sixth head of the school in succession from Pythagoras himself. Diodorus of Aspendus was one of his students. He lived around the 4th or ...

, or (as Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

calls him) Arcesus. Diogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; , ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Little is definitively known about his life, but his surviving book ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal source for the history of ancient Greek ph ...

is the only authority for the claim that shortly after the death of Socrates, Plato traveled to Italy where he met with Philolaus and Eurytus

Eurytus, Eurytos (; Ancient Greek: Εὔρυτος) or Erytus (Ἔρυτος) is the name of several characters in Greek mythology, and of at least one historical figure.

Mythological

*Eurytus, one of the Giants, sons of Gaia, killed by Dionys ...

. The pupils of Philolaus were said to have included Xenophilus Xenophilus or Xenophilos may refer to:

*Xenophilus (5th century BC), playwright who won the Lenaia with a comedy

* Xenophilus (philosopher) (4th century BC), Pythagorean philosopher and music theorist

* Xenophilus (phrourarch) (4th century BC), Ma ...

, Phanto, Echecrates In ancient Greece, Echecrates () was the name of the following men:

*Echecrates of Thessaly, a military officer of Ptolemy IV Philopator, documented around 219–217 BC.

*A son of Demetrius the Fair (c. 285–250 BC) by Olympias of Larissa, and brot ...

, Diocles, and Polymnastus.

As to his death, Diogenes Laërtius reports a dubious story that Philolaus was put to death at Croton on account of being suspected of wanting to be the tyrant;

a story which Diogenes Laërtius even chose to put into verse.

Writings

Pythagoras and his earliest successors do not appear to have committed any of their doctrines to writing. According to Porphyrius (Vit. Pyth. p. 40)

Pythagoras and his earliest successors do not appear to have committed any of their doctrines to writing. According to Porphyrius (Vit. Pyth. p. 40) Lysis

Lysis ( ; from Greek 'loosening') is the breaking down of the membrane of a cell, often by viral, enzymic, or osmotic (that is, "lytic" ) mechanisms that compromise its integrity. A fluid containing the contents of lysed cells is called a ...

and Archippus

Archippus (; Ancient Greek: Ἄρχιππος, "master of the horse") was an early Christian believer mentioned briefly in the New Testament epistles of Philemon and Colossians.

Role in the New Testament

In Paul's letter to Philemon (), Archi ...

collected in a written form some of the principal Pythagorean doctrines, which were handed down as heirlooms in their families, under strict injunctions that they should not be made public. But amid the different and inconsistent accounts of the matter, the first publication of the Pythagorean doctrines is pretty uniformly attributed to Philolaus.

In one source, Diogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; , ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Little is definitively known about his life, but his surviving book ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal source for the history of ancient Greek ph ...

speaks of Philolaus composing one book,Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 85 but elsewhere he speaks of three books, as do Aulus Gellius

Aulus Gellius (c. 125after 180 AD) was a Roman author and grammarian, who was probably born and certainly brought up in Rome. He was educated in Athens, after which he returned to Rome. He is famous for his ''Attic Nights'', a commonplace book, ...

and Iamblichus

Iamblichus ( ; ; ; ) was a Neoplatonist philosopher who determined a direction later taken by Neoplatonism. Iamblichus was also the biographer of the Greek mystic, philosopher, and mathematician Pythagoras. In addition to his philosophical co ...

. It might have been one treatise divided into three books. Plato is said to have procured a copy of his book. Later, it was claimed that Plato composed much of his '' Timaeus'' based upon the book by Philolaus.

One of the works of Philolaus was called ''On Nature''. It seems to be the same work that Stobaeus

Joannes Stobaeus (; ; 5th-century AD), from Stobi in Macedonia (Roman province), Macedonia, was the compiler of a valuable series of extracts from Greek authors. The work was originally divided into two volumes containing two books each. The tw ...

calls ''On the World'' and from which he has preserved a series of passages. Other writers refer to a work entitled ''Bacchae'', which may have been another name for the same work, and which may originate from Arignote

Arignote or Arignota (; , ''Arignṓtē''; fl. c. ) was a Pythagorean philosopher from Croton, Magna Graecia, or from Samos. She was known as a student of Pythagoras and TheanoSuda, ''Arignote'' and, according to some traditions, their daughter ...

. However, it has been mentioned that Proclus

Proclus Lycius (; 8 February 412 – 17 April 485), called Proclus the Successor (, ''Próklos ho Diádokhos''), was a Greek Neoplatonist philosopher, one of the last major classical philosophers of late antiquity. He set forth one of th ...

describes the ''Bacchae'' as a book for teaching theology by means of mathematics. It appears, in fact, from this, as well as from the extant fragments, that the first book of the work contained a general account of the origin and arrangement of the universe. The second book appears to have been an exposition of the nature of numbers, which in the Pythagorean theory are the essence and source of all things.

He composed a work on the Pythagorean philosophy in three books, which Plato is said to have procured at the cost of 100 minae

The Ministry of Environment and Energy (, MINAE) is a ministry or department of the government of Costa Rica.

Agencies

*SINAC - National System of Conservation Areas

*DGGM - Geology and Mining General Directorate

*SETENA - National Technical ...

through Dion of Syracuse

Dion (; ; 408–354 BC), tyrant of Syracuse in Magna Graecia, was the son of Hipparinus, and brother-in-law of Dionysius I of Syracuse. A disciple of Plato, he became Dionysius I's most trusted minister and adviser. However, his great wealth, ...

, who purchased it from Philolaus, who was at the time in deep poverty. Other versions of the story represent Plato as purchasing it himself from Philolaus or his relatives when in Sicily. Out of the materials which he derived from these books Plato is said to have composed his ''Timaeus''. But in the age of Plato the leading features of the Pythagorean doctrines had long ceased to be a secret; and if Philolaus taught the Pythagorean doctrines at Thebes Thebes or Thebae may refer to one of the following places:

*Thebes, Egypt, capital of Egypt under the 11th, early 12th, 17th and early 18th Dynasties

*Thebes, Greece, a city in Boeotia

*Phthiotic Thebes

Phthiotic Thebes ( or Φθιώτιδες Θ ...

, he was hardly likely to feel much reluctance in publishing them; and amid the conflicting and improbable accounts preserved in the authorities above referred to, little more can be regarded as trustworthy, except that Philolaus was the first who published a book on the Pythagorean doctrines, and that Plato read and made use of it.

Historians from the ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'', Chapter ''Philolaus' Book: Genuine Fragments and Testimonia'', noted the following:

Philosophy

Philolaus argued at the foundation of everything is the part played by the ideas of limit and the unlimited. One of the first declarations in the work of Philolaus was that all things in the universe result from a combination of the unlimited and the limiting; for if all things had been unlimited, nothing could have been the object of knowledge. Limiters and unlimiteds are combined in a harmony (''harmonia''):

Robert Scoon explained Philolaus' universe in 1922:

The book by Philolaus begins with the following:

According to Stobaeus, Philolaus did away with the ideas of fixed direction in space and developed one of the first non-geocentric views of the universe and in his new way of thinking, the universe revolved around a

Philolaus argued at the foundation of everything is the part played by the ideas of limit and the unlimited. One of the first declarations in the work of Philolaus was that all things in the universe result from a combination of the unlimited and the limiting; for if all things had been unlimited, nothing could have been the object of knowledge. Limiters and unlimiteds are combined in a harmony (''harmonia''):

Robert Scoon explained Philolaus' universe in 1922:

The book by Philolaus begins with the following:

According to Stobaeus, Philolaus did away with the ideas of fixed direction in space and developed one of the first non-geocentric views of the universe and in his new way of thinking, the universe revolved around a hypothetical astronomical object

Various unknown astronomical objects have been hypothesized throughout recorded history. For example, in the 5th century BCE, the philosopher Philolaus defined a hypothetical astronomical object which he called the " Central Fire", around whic ...

he called the Central Fire

An astronomical system positing that the Earth, Moon, Sun, and planets revolve around an unseen "Central Fire" was developed in the fifth century BC and has been attributed to the Pythagorean philosopher Philolaus. The system has been called "the ...

.

In Philolaus's system a sphere of the fixed star

A star is a luminous spheroid of plasma (physics), plasma held together by Self-gravitation, self-gravity. The List of nearest stars and brown dwarfs, nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night sk ...

s, the five planet

A planet is a large, Hydrostatic equilibrium, rounded Astronomical object, astronomical body that is generally required to be in orbit around a star, stellar remnant, or brown dwarf, and is not one itself. The Solar System has eight planets b ...

s, the Sun

The Sun is the star at the centre of the Solar System. It is a massive, nearly perfect sphere of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core, radiating the energy from its surface mainly as visible light a ...

, Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It Orbit of the Moon, orbits around Earth at Lunar distance, an average distance of (; about 30 times Earth diameter, Earth's diameter). The Moon rotation, rotates, with a rotation period (lunar ...

, and Earth, all moved around a Central Fire. According to Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

, writing in ''Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

'', Philolaus added a tenth unseen body, he called Counter-Earth

The Counter-Earth is a : Hypothetical bodies of the Solar System, hypothetical body of the Solar System that orbits on the other side of the Solar System from Earth. A Counter-Earth or ''Antichthon'' () was hypothesized by the pre-Socratic philoso ...

, as without it there would be only nine revolving bodies, and the Pythagorean number theory

Number theory is a branch of pure mathematics devoted primarily to the study of the integers and arithmetic functions. Number theorists study prime numbers as well as the properties of mathematical objects constructed from integers (for example ...

required a tenth. However, Greek scholar George Burch asserts his belief that Aristotle was lampooning Philolaus's addition.

The system that Philolaus described predated the idea of spheres by hundreds of years, however.Burch, George Bosworth. The Counter-Earth

''. Osirus, vol. 11. Saint Catherines Press, 1954. p. 267-294 Nearly two-thousand years later,

Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

would mention in ''De revolutionibus

''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium'' (English translation: ''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres'') is the seminal work on the heliocentric theory of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) of the Polish Renaissance. The book ...

'' that Philolaus already knew about the Earth's revolution around a central fire.

It has been pointed out, however, that Stobaeus betrays a tendency to confound the dogmas of the early Ionian philosophers, and in his accounts, he occasionally mixes up Platonism with Pythagoreanism.

See also

*Alcmaeon of Croton

Alcmaeon of Croton (; , ''Alkmaiōn'', ''gen''.: Ἀλκμαίωνος; fl. 5th century BC) was an early Greek medical writer and philosopher-scientist. He has been described as one of the most eminent natural philosophers and medical theorists ...

*Apeiron

''Apeiron'' (; ) is a Greek word meaning '(that which is) unlimited; boundless; infinite; indefinite' from ''a-'' 'without' and ''peirar'' 'end, limit; boundary', the Ionic Greek form of ''peras'' 'end, limit, boundary'.

Origin of everything

...

*Nicomachus

Nicomachus of Gerasa (; ) was an Ancient Greek Neopythagorean philosopher from Gerasa, in the Roman province of Syria (now Jerash, Jordan). Like many Pythagoreans, Nicomachus wrote about the mystical properties of numbers, best known for his ...

*Parmenides

Parmenides of Elea (; ; fl. late sixth or early fifth century BC) was a Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic ancient Greece, Greek philosopher from Velia, Elea in Magna Graecia (Southern Italy).

Parmenides was born in the Greek colony of Veli ...

* ''Protrepticus'' (Aristotle)

*Pythagoreans

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek co ...

Notes

References

Other sources

*External links

* * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Philolaus 5th-century BC Greek philosophers Ancient Greek physicists Ancient Greek political refugees Ancient Thebes, Greece Presocratic philosophers Pythagoreans of Magna Graecia Ancient Crotonians 470s BC births 380s BC deaths 5th-century BC Greek mathematicians 4th-century BC Greek mathematicians