Phillips Andover Academy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Phillips Academy (also known as PA, Phillips Academy Andover, or simply Andover) is a

After a period of decline, Cecil Bancroft (h. 1873–1901), Alfred Stearns (h. 1903–33), and Claude Fuess (h. 1933–48) led Andover through a long era of expansion that transformed Andover into one of the largest and richest prep schools in the United States. Bancroft improved Andover's academic reputation; he reformed the curriculum to the expectations of college presidents and visited the English public schools to learn about best practices in Europe. Aided by a "sink-or-swim" policy of expelling underperforming or undisciplined students, the academy was able to place a majority of its students at Yale, Harvard, or Princeton (64% in 1931 and 74% in 1937). Enrollment, which had fallen from 396 students in 1855 to 177 in 1877, rebounded to roughly 400 by 1901 and passed 700 in 1937.

After a period of decline, Cecil Bancroft (h. 1873–1901), Alfred Stearns (h. 1903–33), and Claude Fuess (h. 1933–48) led Andover through a long era of expansion that transformed Andover into one of the largest and richest prep schools in the United States. Bancroft improved Andover's academic reputation; he reformed the curriculum to the expectations of college presidents and visited the English public schools to learn about best practices in Europe. Aided by a "sink-or-swim" policy of expelling underperforming or undisciplined students, the academy was able to place a majority of its students at Yale, Harvard, or Princeton (64% in 1931 and 74% in 1937). Enrollment, which had fallen from 396 students in 1855 to 177 in 1877, rebounded to roughly 400 by 1901 and passed 700 in 1937. To compete with newer, fully residential boarding schools, the headmasters built new on-campus housing and modernized the academic facilities, a process that took over a generation to complete. Shortly after taking over, Bancroft recognized that Andover's historical reliance on local families for student housing was hurting its reputation. By 1901 Andover provided housing for approximately one-third of boarders; by 1929 all boarders could finally live on campus. Much of this expansion was funded by banker Thomas Cochran '90, a partner at

To compete with newer, fully residential boarding schools, the headmasters built new on-campus housing and modernized the academic facilities, a process that took over a generation to complete. Shortly after taking over, Bancroft recognized that Andover's historical reliance on local families for student housing was hurting its reputation. By 1901 Andover provided housing for approximately one-third of boarders; by 1929 all boarders could finally live on campus. Much of this expansion was funded by banker Thomas Cochran '90, a partner at  During this period, Andover was a primarily white and Protestant institution, although its expanding scholarship program and occasional steps toward racial integration made it relatively diverse by New England boarding school standards. The share of scholarship boys steadily increased from 10% in 1901 to roughly 25% in 1944. Andover was one of the first New England boarding schools to accept black students, starting in the 1850s.Allis, p. 287. However, it had just five black students when Bancroft died in 1901, and black representation actually declined under Bancroft's successors: only four African-Americans attended Andover between 1911 and 1934. The academy admitted more Jewish students but capped their numbers at roughly 5% of the student body. Andover was also one of the first American schools to educate Chinese students, participating in the 1872–1881 Chinese Educational Mission; one student,

During this period, Andover was a primarily white and Protestant institution, although its expanding scholarship program and occasional steps toward racial integration made it relatively diverse by New England boarding school standards. The share of scholarship boys steadily increased from 10% in 1901 to roughly 25% in 1944. Andover was one of the first New England boarding schools to accept black students, starting in the 1850s.Allis, p. 287. However, it had just five black students when Bancroft died in 1901, and black representation actually declined under Bancroft's successors: only four African-Americans attended Andover between 1911 and 1934. The academy admitted more Jewish students but capped their numbers at roughly 5% of the student body. Andover was also one of the first American schools to educate Chinese students, participating in the 1872–1881 Chinese Educational Mission; one student,

Phillips Academy follows a trimester program, where a school year is divided into three terms lasting around ten weeks each. With 232 teaching faculty, a 7:1 student-faculty ratio, and an average class size of 13, Andover is able to offer 300 courses and a faculty-guided independent research option. Courses may last one, two, or three terms. Although Andover helped create the

Phillips Academy follows a trimester program, where a school year is divided into three terms lasting around ten weeks each. With 232 teaching faculty, a 7:1 student-faculty ratio, and an average class size of 13, Andover is able to offer 300 courses and a faculty-guided independent research option. Courses may last one, two, or three terms. Although Andover helped create the

The academy's dormitories vary in size from as few as four to as many as 40 students, and are organized into five "clusters" of roughly 220 students and 40 faculty affiliates each. Many social events are organized through the cluster system, including orientation, study breaks, and snacks. None of the original dormitory buildings remain; the oldest dorm is Blanchard House, built in 1789.

Two dormitory names carry on the Andover Theological Seminary tradition: America House, where the song ''

The academy's dormitories vary in size from as few as four to as many as 40 students, and are organized into five "clusters" of roughly 220 students and 40 faculty affiliates each. Many social events are organized through the cluster system, including orientation, study breaks, and snacks. None of the original dormitory buildings remain; the oldest dorm is Blanchard House, built in 1789.

Two dormitory names carry on the Andover Theological Seminary tradition: America House, where the song ''

The Addison Gallery of American Art is an art museum donated by Thomas Cochran in memory of Keturah Addison Cobb, the mother of his friend Zaidee Cobb Bliss. It is open to the public, and underwent a $30 million renovation and expansion from 2008 to 2010.

The gallery's permanent collection includes Winslow Homer's ''Eight Bells'', along with work by

The Addison Gallery of American Art is an art museum donated by Thomas Cochran in memory of Keturah Addison Cobb, the mother of his friend Zaidee Cobb Bliss. It is open to the public, and underwent a $30 million renovation and expansion from 2008 to 2010.

The gallery's permanent collection includes Winslow Homer's ''Eight Bells'', along with work by

Athletic competition has long been a part of the Phillips Academy tradition. As early as 1805, some form of "football" was being played on campus; that year, Eliphalet Pearson's son Henry wrote that "I cannot write a long letter as I am very tired after having played at football all this afternoon." (The first game of what is now known as

Athletic competition has long been a part of the Phillips Academy tradition. As early as 1805, some form of "football" was being played on campus; that year, Eliphalet Pearson's son Henry wrote that "I cannot write a long letter as I am very tired after having played at football all this afternoon." (The first game of what is now known as  Today, Andover is an athletic powerhouse among New England private schools. Andover athletes have won over 110 New England championships in the last three decades. Some teams have even competed internationally; for example, the boys' crew has competed at England's

Today, Andover is an athletic powerhouse among New England private schools. Andover athletes have won over 110 New England championships in the last three decades. Some teams have even competed internationally; for example, the boys' crew has competed at England's

File:George_H._W._Bush_presidential_portrait_(cropped).jpg, President

Andover has educated two U.S. presidents (

"The WASP ascendancy"

, "...In 1930, eight private schools accounted for nearly one-third of Yale freshman: Andover (74), Exeter (54), Hotchkiss (42), St. Paul's (24), Choate (19), Lawrenceville (19), Hill (17) and Kent (14) ...". Accessed June 26, 2013. An account in ''

''This Side of Paradise''

, "...There were Andover and Exeter with their memories of New England dead—large, college-like democracies ...". Accessed June 21, 2013. * The Marvel Cinematic Universe references the school as being Tony Stark's high school from years 1977-1984 before continuing on to MIT

online

* McLachlan, James. ''American Boarding Schools: A Historical Study'' (1970

online

* *

private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* "In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorded ...

, co-educational

Mixed-sex education, also known as mixed-gender education, co-education, or coeducation (abbreviated to co-ed or coed), is a system of education where males and females are educated together. Whereas single-sex education was more common up to ...

college-preparatory school

A college-preparatory school (often shortened to prep school, preparatory school, college prep school or college prep academy) is a type of secondary school. The term refers to state school, public, Independent school, private independent or p ...

for boarding and day

A day is the time rotation period, period of a full Earth's rotation, rotation of the Earth with respect to the Sun. On average, this is 24 hours (86,400 seconds). As a day passes at a given location it experiences morning, afternoon, evening, ...

students located in Andover, Massachusetts

Andover is a town in Essex County, Massachusetts, United States. It was Settler, settled in 1642 and incorporated in 1646."Andover" in ''Encyclopedia Britannica, The New Encyclopædia Britannica''. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 15th ed. ...

, a suburb of Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

. The academy enrolls approximately 1,150 students in grades 9 through 12, including postgraduate

Postgraduate education, graduate education, or graduate school consists of academic or professional degrees, certificates, diplomas, or other qualifications usually pursued by post-secondary students who have earned an undergraduate (bachelor' ...

students. It is part of the Eight Schools Association and the Ten Schools Admission Organization.

Founded in 1778, Andover is one of the oldest high schools in the United States. It has educated a distinguished list of notable alumni through its history, including American presidents George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushBefore the outcome of the 2000 United States presidential election, he was usually referred to simply as "George Bush" but became more commonly known as "George H. W. Bush", "Bush Senior," "Bush 41," and even "Bush th ...

and George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

, Bill Belichick, foreign heads of state, members of Congress, five Nobel laureates

The Nobel Prizes (, ) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make outstanding contributions in th ...

and six Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, military decoration and is awarded to recognize American United States Army, soldiers, United States Navy, sailors, Un ...

recipients.

Andover admits students on a need-blind basis and provides financial aid covering 100% of students' demonstrated financial need. 47% of Andover students receive financial aid.

History

Revolutionary-era beginnings

Phillips Academy is the oldest incorporated academy in the United States. It was established in 1778 by Samuel Phillips Jr., a local businessman who hoped to educateCalvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

students for the ministry.

The American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

had caused significant upheaval to education in New England, and Phillips Academy filled part of that gap. (For example, Boston Latin School

The Boston Latin School is a Magnet school, magnet Latin schools, Latin Grammar schools, grammar State school, state school in Boston, Massachusetts. It has been in continuous operation since it was established on April 23, 1635. It is the old ...

shut down during the war because its headmaster John Lovell, a Loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

, fled to British Canada after the fall of Boston in 1776.) The founders of Phillips Academy were strongly associated with the Patriot cause. Samuel Phillips and Eliphalet Pearson (later Andover's first head of school) manufactured gunpowder for the Continental Army, and the founders attempted to stock Andover's library with books confiscated from Loyalist families who had fled New England.

Several prominent Revolutionary figures maintained links with the academy, including George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

(who personally visited the academy while president in 1789; eight of his nephews and grandnephews attended Andover), John Hancock

John Hancock ( – October 8, 1793) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father, merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot (American Revolution), Patriot of the American Revolution. He was the longest-serving Presi ...

(who signed the academy's articles of incorporation), and Paul Revere

Paul Revere (; December 21, 1734 O.S. (January 1, 1735 N.S.)May 10, 1818) was an American silversmith, military officer and industrialist who played a major role during the opening months of the American Revolutionary War in Massachusetts, ...

(who designed the academy seal). Revere's design of the academy seal incorporated a beehive, crops, the sun, and the academy's two mottos: ''Non Sibi'' ("not for oneself") and ''Finis Origine Pendet'' ("the end depends upon the beginning"). Other mottos include ''Youth from Every Quarter'' and ''Knowledge and Goodness'', two paraphrases from the academy constitution.

In 1828, all-boys Phillips Academy was joined by a sister school, Abbot Academy. Abbot was one of the first secondary schools for girls in New England. Although the academies had neighboring campuses in the town of Andover, their administrations sought to limit and regulate contact between the student bodies. The two academies merged in 1973.

Calvinist roots and Exeter rivalry

Phillips Academy's traditional rival isPhillips Exeter Academy

Phillips Exeter Academy (often called Exeter or PEA) is an Independent school, independent, co-educational, college-preparatory school in Exeter, New Hampshire. Established in 1781, it is America's sixth-oldest boarding school and educates an es ...

, which was established three years later in Exeter, New Hampshire

Exeter is a New England town, town in Rockingham County, New Hampshire, United States. Its population was 16,049 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, up from 14,306 at the 2010 census. Exeter was the county seat until 1997, when county ...

, by Samuel Phillips' uncle John Phillips. Andover and Exeter's sports teams have played each other since 1861, and the football teams have met nearly every year since 1878, making Andover-Exeter one of the nation's oldest high school football rivalries.

From 1808 to 1907, Phillips Academy shared its campus with the Andover Theological Seminary

Andover Theological Seminary (1807–1965) was a Congregationalist seminary founded in 1807 and originally located in Andover, Massachusetts on the campus of Phillips Academy.

From 1908 to 1931, it was located at Harvard University in Cambrid ...

, which was founded by orthodox Calvinists

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Christian, Presbyterian, ...

who had fled Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

after it appointed a liberal Unitarian theology professor. The Phillips family financially backed the seminary, and the two institutions shared a board of directors.

Andover's commitment to orthodox theology helped fuel the Exeter rivalry. Exeter was more welcoming to Unitarians or at least less religious; for example, unlike Andover, its academy constitution did not compel Exeter to teach the doctrine of justification by faith alone. As such, Exeter tended to send its students to Unitarian Harvard. Andover steered its students to Yale

Yale University is a private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States, and one of the nine colonial colleges ch ...

, which was more hospitable to Calvinists. This was due in part to the conservative influence of the seminary (whose endowment and facilities were superior to the academy's), and in other part to the fact that Andover's constitution explicitly required Andover to profess and teach Calvinist theology. The constitution also required all teachers and trustees to be Protestants, although Andover no longer enforces this restriction.

Certain New England families were drawn to Andover's reputation for theological conservatism. In the 1880s, the bulk of Andover students came from Congregationalist (mainly Calvinist) and Presbyterian households, and the academy enrolled "almost no" Unitarians or Methodists. However, by the 1900s, Calvinism was no longer popular in New England, and Andover Theological Seminary was facing declining enrollment. In 1907, the seminary reconciled with Harvard and returned to Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

.

Today, Andover and Exeter are now both nonsectarian institutions, and the rivalry no longer carries religious overtones.

Revival as college-preparatory institution

After a period of decline, Cecil Bancroft (h. 1873–1901), Alfred Stearns (h. 1903–33), and Claude Fuess (h. 1933–48) led Andover through a long era of expansion that transformed Andover into one of the largest and richest prep schools in the United States. Bancroft improved Andover's academic reputation; he reformed the curriculum to the expectations of college presidents and visited the English public schools to learn about best practices in Europe. Aided by a "sink-or-swim" policy of expelling underperforming or undisciplined students, the academy was able to place a majority of its students at Yale, Harvard, or Princeton (64% in 1931 and 74% in 1937). Enrollment, which had fallen from 396 students in 1855 to 177 in 1877, rebounded to roughly 400 by 1901 and passed 700 in 1937.

After a period of decline, Cecil Bancroft (h. 1873–1901), Alfred Stearns (h. 1903–33), and Claude Fuess (h. 1933–48) led Andover through a long era of expansion that transformed Andover into one of the largest and richest prep schools in the United States. Bancroft improved Andover's academic reputation; he reformed the curriculum to the expectations of college presidents and visited the English public schools to learn about best practices in Europe. Aided by a "sink-or-swim" policy of expelling underperforming or undisciplined students, the academy was able to place a majority of its students at Yale, Harvard, or Princeton (64% in 1931 and 74% in 1937). Enrollment, which had fallen from 396 students in 1855 to 177 in 1877, rebounded to roughly 400 by 1901 and passed 700 in 1937. To compete with newer, fully residential boarding schools, the headmasters built new on-campus housing and modernized the academic facilities, a process that took over a generation to complete. Shortly after taking over, Bancroft recognized that Andover's historical reliance on local families for student housing was hurting its reputation. By 1901 Andover provided housing for approximately one-third of boarders; by 1929 all boarders could finally live on campus. Much of this expansion was funded by banker Thomas Cochran '90, a partner at

To compete with newer, fully residential boarding schools, the headmasters built new on-campus housing and modernized the academic facilities, a process that took over a generation to complete. Shortly after taking over, Bancroft recognized that Andover's historical reliance on local families for student housing was hurting its reputation. By 1901 Andover provided housing for approximately one-third of boarders; by 1929 all boarders could finally live on campus. Much of this expansion was funded by banker Thomas Cochran '90, a partner at J. P. Morgan

John Pierpont Morgan Sr. (April 17, 1837 – March 31, 1913) was an American financier and investment banker who dominated corporate finance on Wall Street throughout the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. As the head of the banking firm that ...

who had no children and wanted to make Andover "the most beautiful school in America." Cochran donated roughly $10 million to Andover (approximately $181 million in February 2024 dollars); for reference, when he died his estate was probated at $3 million. In 1928, as many as 15,000 people visited Andover's campus to hear President Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States, serving from 1923 to 1929. A Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer from Massachusetts, he previously ...

deliver the keynote address at Andover's 150th anniversary celebration, a speech that Cochran had arranged. During this period, Andover was a primarily white and Protestant institution, although its expanding scholarship program and occasional steps toward racial integration made it relatively diverse by New England boarding school standards. The share of scholarship boys steadily increased from 10% in 1901 to roughly 25% in 1944. Andover was one of the first New England boarding schools to accept black students, starting in the 1850s.Allis, p. 287. However, it had just five black students when Bancroft died in 1901, and black representation actually declined under Bancroft's successors: only four African-Americans attended Andover between 1911 and 1934. The academy admitted more Jewish students but capped their numbers at roughly 5% of the student body. Andover was also one of the first American schools to educate Chinese students, participating in the 1872–1881 Chinese Educational Mission; one student,

During this period, Andover was a primarily white and Protestant institution, although its expanding scholarship program and occasional steps toward racial integration made it relatively diverse by New England boarding school standards. The share of scholarship boys steadily increased from 10% in 1901 to roughly 25% in 1944. Andover was one of the first New England boarding schools to accept black students, starting in the 1850s.Allis, p. 287. However, it had just five black students when Bancroft died in 1901, and black representation actually declined under Bancroft's successors: only four African-Americans attended Andover between 1911 and 1934. The academy admitted more Jewish students but capped their numbers at roughly 5% of the student body. Andover was also one of the first American schools to educate Chinese students, participating in the 1872–1881 Chinese Educational Mission; one student, Liang Cheng

Liang Cheng (November 30, 1864 – February 3, 1917), courtesy name Liang Chentung, also known as Liang Pi Yuk, and later as Chentung Liang Cheng, was a Chinese ambassador to the United States during the Qing dynasty. He was primarily respons ...

, later became the Chinese ambassador to the United States.

In the 1930s, Andover participated in the International Schoolboy Fellowship, a cultural exchange program between U.S. boarding schools, British public schools, and Nazi boarding schools. As U.S.-Germany relations deteriorated, Andover terminated the arrangement in 1939 at the State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or simply the State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs o ...

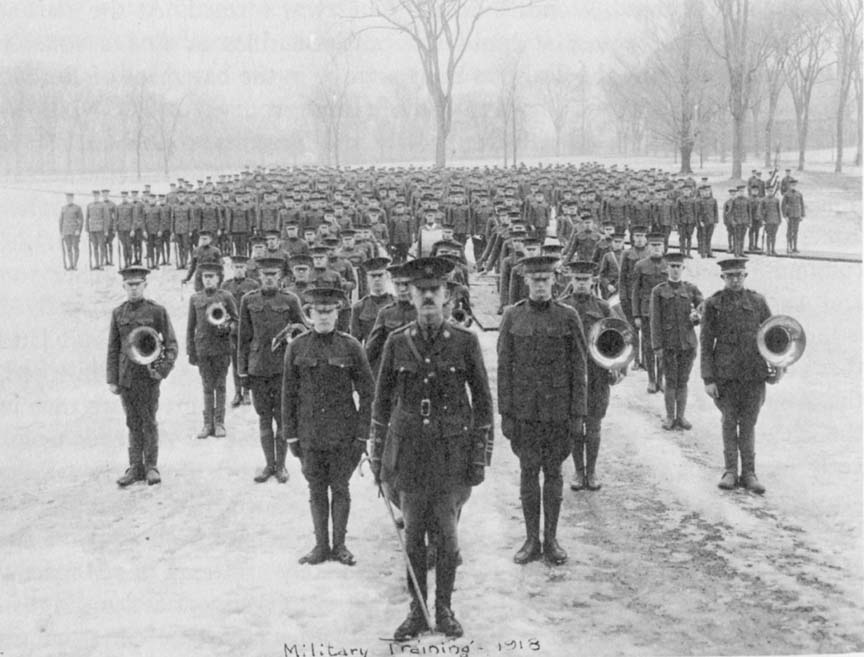

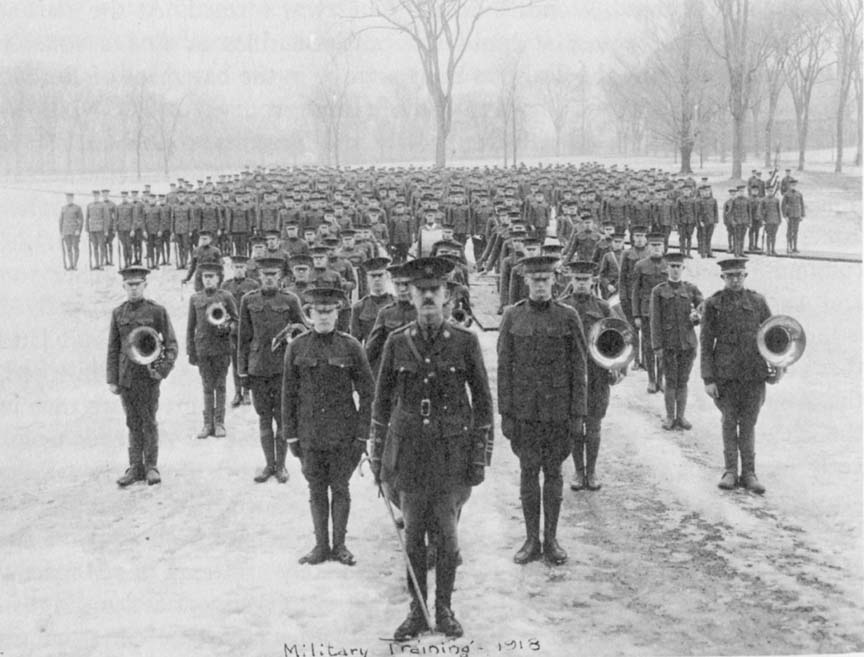

's request.Allis, p. 479. Following America's entry into World War II, over 3,000 Andover graduates participated in the war effort in some capacity, with 142 deaths.

Post-war to present

John Kemper (h. 1948–71) updated the curriculum and improved salaries and benefits for faculty members. Under his leadership, Andover co-authored a study on high school students' preparation for college coursework, which led to the creation of theAdvanced Placement

Advanced Placement (AP) is a program in the United States and Canada created by the College Board. AP offers undergraduate university-level curricula and examinations to high school students. Colleges and universities in the US and elsewhere ...

program. Although tightening academic standards at elite universities and increased competition from public schools caused Andover's college placement record to decline significantly during Kemper's administration—the proportion of graduates attending Yale, Harvard, or Princeton fell to 55% in 1953 and 33% in 1967—nearly every major boarding school endured similar declines during this period.

Like many other boarding school administrators, Kemper and his successors also sought to democratize the campus. Andover began to admit more black students in the 1950s and 1960s, but progress was slow; by 1978, 6% of the student body was black or Hispanic. Andover abolished secret societies in 1949, although one society still exists. It also abolished mandatory attendance at religious services in the early 1970s. Phillips Academy became co-educational in 1973, when it merged with its sister school Abbot Academy.

During this period, Andover also began coordinating policy with other large and wealthy secondary schools. In 1952, the Ten Schools Admission Organization began coordinating outreach to potential applicants and streamlining the admissions process. After Kemper's retirement, Andover became a founding member of the Eight Schools Association, an informal group of headmasters of large boarding schools that began meeting in the 1970s and formalized in 2006.

Raynard S. Kington has been Head of School since 2019. He was previously the president of Grinnell College

Grinnell College ( ) is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Grinnell, Iowa, United States. It was founded in 1846 when a group of Congregationalism in the United States, Congregationalis ...

in Iowa. The previous Head of School was law professor (and 1990 Exeter graduate) John Palfrey

John Gorham Palfrey VII (born 1972) is an American educator, scholar, and law professor. His areas of focus include emerging media, Internet censorship, Internet freedom, online Transparency (social), transparency and accountability, and child sa ...

, who left Andover to take over the MacArthur Foundation

The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation is a private foundation that makes grants and impact investments to support non-profit organizations in approximately 117 countries around the world. It has an endowment of $7.6 billion and ...

. The academy is supervised by a board of trustees, all of whom are alumni except the Head of School. It is accredited by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges

The New England Association of Schools and Colleges, Inc. (NEASC ) is an American educational organization that accredits private and public secondary schools (high schools and technical/career institutions), primarily in New England. It also ...

.

Admissions and student body

Admission policies

Phillips Academy is one of the most selective boarding schools in the United States, especially in light of its size. In 2016, four boarding schools had an acceptance rate lower than 15%, and Andover was larger than the other three put together. The acceptance rate normally hovers around 13%, but during theCOVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic (also known as the coronavirus pandemic and COVID pandemic), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), began with an disease outbreak, outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, in December ...

, it fell to 9% in 2022.

Andover has practiced need-blind admission

Need-blind admission in the United States refers to a College admissions in the United States, college admission policy that does not take into account an applicant's financial status when deciding whether to accept them. This approach typically re ...

since 2007. It also offers financial aid that covers 100% of demonstrated financial need for every admitted student. To recruit U.S. students from "historically underrepresented" backgrounds, Andover pays for certain prospective financial aid applicants and their guardians to visit the campus during the admissions process.

About one of every eight Andover students (12.9%) has a parent who attended Andover, and at least one out of every five Andover students has a sibling who attended Andover.

Student body

Andover enrolls a student body that is more racially diverse than Massachusetts, although the numbers vary significantly depending on whether respondents are permitted to identify as two or more races. The academy reports that 59% of students identify as people of color. For the 2021–2022 school year, Andover reported that 36.5% of its students were white, 33.0% were Asian, 10.2% were black, 10.5% were Hispanic, 0.5% were Native American/Alaska Native, and 9.3% were multiracial. The survey in question did not allow Andover to identify one student in multiple categories. By contrast, a March 2023 survey conducted by Andover's student newspaper (to which 81.0% of the student body responded) found that 50.2% of Andover students identified as white, 42.9% as Asian (including 25.8% as Asian Americans), 13.4% as black (including 8.6% as African American), 10.9% as Hispanic or Latino, 1.4% as Native American/Alaska Native, and 1.3% as Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. This survey allowed students to identify with multiple categories. The percentage of black students represents a significant increase from 2021, when 10.4% of students identified as black and 6.8% as African American. Andover enrolls a large international student population, representing approximately 15% of the student body. In March 2024, Andover enrolled 184 international students, of whom 55 were U.S. citizens living abroad. Conversely, a quarter of the student body lives off campus in neighboring communities. The student body is relatively affluent and politically liberal. As of March 2023, 95.4% of Andover students have at least one parent who graduated from college, and 46.8% of students have family household incomes over $250,000/year, compared to the 11.3% of students with family household incomes under $100,000/year (another 22.9% do not know their family income). 38.8% of students identified as liberal, 13.3% as independent, 8.6% as conservative, and 8.0% as either communist or socialist (another 26.5% were unsure as to their political affiliation). 21.6% of students identified as agnostic and 21.1% as atheist, compared to 22.5% who identified as "Christian", 16.9% as Catholic, and 5.4% as Protestant (students could select multiple choices). In addition, 6.4% of students identified as ethnically Jewish and 5.3% as religiously Jewish.Academics

Curriculum

Advanced Placement

Advanced Placement (AP) is a program in the United States and Canada created by the College Board. AP offers undergraduate university-level curricula and examinations to high school students. Colleges and universities in the US and elsewhere ...

program, the academy de-emphasized AP classes in the 21st century, citing a desire to maintain curricular flexibility and independence.

Andover does not rank students. It calculates GPA using a 6.0 scale instead of the usual 4.0 scale, where a 6 is considered outstanding, a 5 is an honors grade, and a 2 is a passing grade. A March 2023 student survey found that the average GPA was 5.41; it was 5.18 in 2018.

Andover also runs a five-week summer session for approximately 600 students entering grades 8-12, which dates back to 1942.

Test scores

Andover does not publicly report its students' standardized test scores, explaining that many colleges adopted test-optional admission policies during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Class of 2019's average combinedSAT

The SAT ( ) is a standardized test widely used for college admissions in the United States. Since its debut in 1926, its name and Test score, scoring have changed several times. For much of its history, it was called the Scholastic Aptitude Test ...

score was 1460 (720 reading, 740 math), and its average combined ACT score was 31.1.

Grade levels

In the 2022–23 school year, Andover enrolled 214 freshmen (in academy jargon, "juniors"), 276 sophomores ("lowers"), 311 juniors ("uppers"), and 348 seniors and postgraduates ("seniors" and "PGs"), for a total enrollment of 1,149 students.Facilities

The old core of Phillips Academy's campus is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as part of the Academy Hill Historic District. It includes the historic campuses of Phillips Academy, Abbot Academy, and Andover Theological Seminary, the latter of which sold its buildings to Phillips Academy when it left Andover in 1907. In the 1920s and 1930s, Andover added new buildings around this campus core, including the administrative building, library, dining hall, art gallery, chapel, math building, and dormitories. Many of the buildings were named after notable Americans, some (but not all) of whom attended Andover. Portions of Andover's campus were laid out byFrederick Law Olmsted

Frederick Law Olmsted (April 26, 1822 – August 28, 1903) was an American landscape architect, journalist, Social criticism, social critic, and public administrator. He is considered to be the father of landscape architecture in the U ...

, designer of Central Park

Central Park is an urban park between the Upper West Side and Upper East Side neighborhoods of Manhattan in New York City, and the first landscaped park in the United States. It is the List of parks in New York City, sixth-largest park in the ...

. Beginning in 1891, Olmsted and his architectural firm advised Andover on campus design; this relationship would continue for the next five decades.

Notable academic facilities

* George Washington Hall hosts the school's administrative offices and the Drama and Art Departments. It also hosts the school post office, locker rooms, and Day Student Lounge. It was built in 1926. * Bulfinch Hall hosts the English Department. It was built in 1819 and renovated in 2012. It was named after architectCharles Bulfinch

Charles Bulfinch (August 8, 1763 – April 15, 1844) was an early American architect, and has been regarded by many as the first American-born professional architect to practice.Baltzell, Edward Digby. ''Puritan Boston & Quaker Philadelphia''. Tra ...

, who taught the hall's architect Asher Benjamin.

* Pearson Hall hosts the Classics Department. It was built in 1817. It was formerly the chapel of Andover Theological Seminary.

* Morse Hall hosts the Math Department, the student radio station

Radio broadcasting is the broadcasting of audio (sound), sometimes with related metadata, by radio waves to radio receivers belonging to a public audience. In terrestrial radio broadcasting the radio waves are broadcast by a land-based rad ...

, some student publications, and the Community and Multicultural Development department. It was built in the 1920s/1930s. It was named after Samuel Morse

Samuel Finley Breese Morse (April 27, 1791 – April 2, 1872) was an American inventor and painter. After establishing his reputation as a portrait painter, Morse, in his middle age, contributed to the invention of a Electrical telegraph#Morse ...

'05, who invented the telegraph and Morse code

Morse code is a telecommunications method which Character encoding, encodes Written language, text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code i ...

.

* Gelb Science Center hosts the Science Department and an observatory. It was built in 2004. It was named after donor Richard L. Gelb '41, the heir to the Clairol

Clairol is the American personal care-product division of company Wella, specializing in hair coloring and hair care. Clairol was founded in 1931 by Americans Joan Gelb and her husband Lawrence M. Gelb, with business partner and lifelong frien ...

hair care company.

* Oliver Wendell Holmes Library (OWHL) houses over 80,000 books and contains classroom space. It was built in 1929 and renovated in 1987 and 2019. It is named after Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. '25, the poet and physician. Built in the Georgian Revival architectural style, it has been modernized over the years and now contains a silent study room and a makerspace.

Student facilities

* Cochran Chapel hosts religious services and the philosophy, religious studies, and community service departments. It is the only building on campus named for the Cochran family, who built much of the modern-day Andover campus. * Paresky Commons is the dining hall. Designed by Charles Platt in theColonial Revival

The Colonial Revival architectural style seeks to revive elements of American colonial architecture.

The beginnings of the Colonial Revival style are often attributed to the Centennial Exhibition of 1876, which reawakened Americans to the arch ...

style, it opened in 1930 and was extensively renovated in 2007, after which it was renamed in honor of donor David Paresky '56. Commons earned LEED

Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) is a Green building certification systems, green building certification program used worldwide. Developed by the non-profit U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC), it includes a set of rating ...

Silver certification in 2011. Since its opening, the individual grade levels have generally occupied their own sections of the dining hall.

* Cochran Wildlife Sanctuary covers 65 acres and contains the Log Cabin, a place for student groups to hold meetings and sleep-overs.

* Rebecca M. Sykes Wellness Center offers physical and mental health facilities.

* Andover has two athletic centers: the 98,000-square-foot Snyder Center and the 70,000-square-foot Pan Athletic Center.

America

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

'' was penned by a seminarian, and Stowe House, the former residence of writer Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe (; June 14, 1811 – July 1, 1896) was an American author and Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and wrote the popular novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (185 ...

. Stowe's husband Calvin taught at the seminary from 1852 to 1864, and Stowe used her first royalty check from ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two Volume (bibliography), volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans ...

'' to renovate the building. The house was moved to its current location on Bartlet Street in 1929.

The academy also operates the Andover Inn, which has 30 guest rooms and various event spaces. Designed by Sidney Wagner, the three-story Georgian style

Georgian architecture is the name given in most English-speaking countries to the set of architectural styles current between 1714 and 1830. It is named after the first four British monarchs of the House of Hanover, George I, George II, Ge ...

building overlooks a pond. It was built in 1930 and was most recently renovated in 2023. It replaced another inn that had been operating on the same site since 1888.

Museums

The Addison Gallery of American Art is an art museum donated by Thomas Cochran in memory of Keturah Addison Cobb, the mother of his friend Zaidee Cobb Bliss. It is open to the public, and underwent a $30 million renovation and expansion from 2008 to 2010.

The gallery's permanent collection includes Winslow Homer's ''Eight Bells'', along with work by

The Addison Gallery of American Art is an art museum donated by Thomas Cochran in memory of Keturah Addison Cobb, the mother of his friend Zaidee Cobb Bliss. It is open to the public, and underwent a $30 million renovation and expansion from 2008 to 2010.

The gallery's permanent collection includes Winslow Homer's ''Eight Bells'', along with work by John Singleton Copley

John Singleton Copley (July 3, 1738 – September 9, 1815) was an Anglo-American painter, active in both colonial America and England. He was believed to be born in Boston, Province of Massachusetts Bay, to Richard and Mary Singleton Copley ...

, Benjamin West

Benjamin West (October 10, 1738 – March 11, 1820) was a British-American artist who painted famous historical scenes such as ''The Death of Nelson (West painting), The Death of Nelson'', ''The Death of General Wolfe'', the ''Treaty of Paris ( ...

, Thomas Eakins

Thomas Cowperthwait Eakins (; July 25, 1844 – June 25, 1916) was an American Realism (visual arts), realist painter, photographer, sculptor, and fine arts educator. He is widely acknowledged to be one of the most important American artist ...

, James McNeill Whistler

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (; July 10, 1834July 17, 1903) was an American painter in oils and watercolor, and printmaker, active during the American Gilded Age and based primarily in the United Kingdom. He eschewed sentimentality and moral a ...

, Frederic Remington

Frederic Sackrider Remington (October 4, 1861 – December 26, 1909) was an American painter, illustrator, sculptor, and writer who specialized in the genre of Western American Art. His works are known for depicting the Western United Sta ...

, George Bellows

George Wesley Bellows (August 12 or August 19, 1882 – January 8, 1925) was an American realism, American realist painting, painter, known for his bold depictions of urban life in New York City. He became, according to the Columbus Museum of Art ...

, Edward Hopper

Edward Hopper (July 22, 1882 – May 15, 1967) was an American realism painter and printmaker. He is one of America's most renowned artists and known for his skill in depicting modern American life and landscapes.

Born in Nyack, New York, to a ...

, Georgia O'Keeffe, Jackson Pollock

Paul Jackson Pollock (; January 28, 1912August 11, 1956) was an American painter. A major figure in the abstract expressionist movement, Pollock was widely noticed for his "Drip painting, drip technique" of pouring or splashing liquid household ...

, Frank Stella

Frank Philip Stella (May 12, 1936 – May 4, 2024) was an American painter, sculptor, and printmaker, noted for his work in the areas of minimalism and post-painterly abstraction. He lived and worked in New York City for much of his career befor ...

, and Andrew Wyeth

Andrew Newell Wyeth ( ; July 12, 1917 – January 16, 2009) was an American visual artist and one of the best-known American artists of the middle 20th century. Though he considered himself to be an "abstractionist," Wyeth was primarily a realis ...

. The museum also features collections in American photography and decorative arts, with silver

Silver is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag () and atomic number 47. A soft, whitish-gray, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and reflectivity of any metal. ...

and furniture

Furniture refers to objects intended to support various human activities such as seating (e.g., Stool (seat), stools, chairs, and sofas), eating (table (furniture), tables), storing items, working, and sleeping (e.g., beds and hammocks). Furnitur ...

dating back to precolonial America and a collection of colonial model ships. The gallery also features rotating exhibitions.

The Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology was founded in 1901. The academy bills it as "one of the nation's major repositories of Native American archaeological collections." Unlike the Addison Gallery, the Peabody Institute is accessible to researchers, public schools, and visitors only by appointment.

The collection includes materials from the Northeast, Southeast, Midwest, Southwest, Mexico and the Arctic, and range from Paleo Indian (more than 10,000 years ago) to the present day. Since the early 1990s, the museum has been at the forefront of compliance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), Pub. L. 101-601, 25 U.S.C. 3001 et seq., 104 Stat. 3048, is a United States federal law enacted on November 16, 1990.

The Act includes three major sets of provisions. The "re ...

.

Extracurriculars

Phillips Academy's extracurricular activities include music ensembles, a campus newspaper, an Internet radio station (formerly broadcasting as WPAA), and a debate club. Andover's weekly student newspaper, ''The Phillipian'', claims to have been publishing since 1857. If true, it would be the nation's oldest secondary school newspaper, ahead of Exeter's '' The Exonian''. However, the official school history questioned the 1857 date, noting that no further issues were published until 1878, the same year ''The Exonian'' began publishing. According to the ''Phillipian'' website, the newspaper is "entirely uncensored and student run." The Philomathean Society is the nation's second-oldest high school debating society, after Exeter's Daniel Webster Debate Society. Andover students operate the Phillips Academy Poll, the first public opinion poll to be conducted by high school students. In 2022, the poll was featured by Boston Channel 7 News and ''The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. It was founded on February 21, 1925, by Harold Ross and his wife Jane Grant, a reporter for ''The New York T ...

'', among others, after releasing polling results for the 2022 midterm elections. The original pollsters graduated in 2023, and the current status of the poll is unknown.

Athletics

History

Athletic competition has long been a part of the Phillips Academy tradition. As early as 1805, some form of "football" was being played on campus; that year, Eliphalet Pearson's son Henry wrote that "I cannot write a long letter as I am very tired after having played at football all this afternoon." (The first game of what is now known as

Athletic competition has long been a part of the Phillips Academy tradition. As early as 1805, some form of "football" was being played on campus; that year, Eliphalet Pearson's son Henry wrote that "I cannot write a long letter as I am very tired after having played at football all this afternoon." (The first game of what is now known as American football

American football, referred to simply as football in the United States and Canada and also known as gridiron football, is a team sport played by two teams of eleven players on a rectangular American football field, field with goalposts at e ...

was played in 1869, and resembled association football more than gridiron football.) Andover participated in the first-ever high school football game, playing Adams Academy in 1875. The school organized an athletics department in 1903 with the objective of "Athletics for All".Harrison, Fred H., ''Athletics for All: Physical Education and Athletics at Phillips Academy, Andover, 1778–1978'' (Andover, Ma.: 1983) Today, Andover is an athletic powerhouse among New England private schools. Andover athletes have won over 110 New England championships in the last three decades. Some teams have even competed internationally; for example, the boys' crew has competed at England's

Today, Andover is an athletic powerhouse among New England private schools. Andover athletes have won over 110 New England championships in the last three decades. Some teams have even competed internationally; for example, the boys' crew has competed at England's Henley Royal Regatta

Henley Royal Regatta (or Henley Regatta, its original name pre-dating Royal patronage) is a Rowing (sport), rowing event held annually on the River Thames by the town of Henley-on-Thames, England. It was established on 26 March 1839. It diffe ...

.

Andover is not part of any formal athletic conference, but through its membership of the Eight Schools Association, it participates in certain ESA-specific athletic contests. In postseason play, Andover's teams compete in playoffs organized by the New England Preparatory School Athletic Council.

Sports

Andover offers 29 interscholastic programs and 44 intramural or instructional programs, includingfencing

Fencing is a combat sport that features sword fighting. It consists of three primary disciplines: Foil (fencing), foil, épée, and Sabre (fencing), sabre (also spelled ''saber''), each with its own blade and set of rules. Most competitive fe ...

, tai chi

is a Chinese martial art. Initially developed for combat and self-defense, for most practitioners it has evolved into a sport and form of exercise. As an exercise, tai chi is performed as gentle, low-impact movement in which practitioners ...

, figure skating

Figure skating is a sport in which individuals, pairs, or groups perform on figure skates on ice. It was the first winter sport to be included in the Olympic Games, with its introduction occurring at the Figure skating at the 1908 Summer Olympi ...

, and yoga

Yoga (UK: , US: ; 'yoga' ; ) is a group of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines that originated with its own philosophy in ancient India, aimed at controlling body and mind to attain various salvation goals, as pra ...

.

Fall athletic offerings

* Crew

A crew is a body or a group of people who work at a common activity, generally in a structured or hierarchy, hierarchical organization. A location in which a crew works is called a crewyard or a workyard. The word has nautical resonances: the ta ...

(instructional)

* Cross country

* Dance

Dance is an The arts, art form, consisting of sequences of body movements with aesthetic and often Symbol, symbolic value, either improvised or purposefully selected. Dance can be categorized and described by its choreography, by its repertoir ...

(Ballet, Modern, Hip-Hop; Beg–Adv levels)

* Fencing

Fencing is a combat sport that features sword fighting. It consists of three primary disciplines: Foil (fencing), foil, épée, and Sabre (fencing), sabre (also spelled ''saber''), each with its own blade and set of rules. Most competitive fe ...

(instructional)

* Field hockey

Field hockey (or simply referred to as hockey in some countries where ice hockey is not popular) is a team sport structured in standard hockey format, in which each team plays with 11 players in total, made up of 10 field players and a goalk ...

* Skating

Skating involves any sports or recreational activity which consists of traveling on surfaces or on ice using skates, and may refer to:

Ice skating

*Ice skating, moving on ice by using ice skates

**Figure skating, a sport in which individuals, ...

(instructional)

* FIT (Fundamentals In Training)

* Football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kick (football), kicking a football (ball), ball to score a goal (sports), goal. Unqualified, football (word), the word ''football'' generally means the form of football t ...

* Gunga FIT ("extreme" version of FIT)

* Outdoor Pursuits (S&R)

* Pilates

Pilates (; ) is a type of mind-body exercise developed in the early 20th century by German physical trainer Joseph Pilates, after whom it was named. Pilates called his method "Contrology". Pilates uses a combination of around 50 repetitive e ...

* SLAM (instructional heerleading

* Soccer

Association football, more commonly known as football or soccer, is a team sport played between two teams of 11 Football player, players who almost exclusively use their feet to propel a Ball (association football), ball around a rectangular f ...

* Soccer

Association football, more commonly known as football or soccer, is a team sport played between two teams of 11 Football player, players who almost exclusively use their feet to propel a Ball (association football), ball around a rectangular f ...

(intramural)

* Squash (instructional)

* Swimming

Swimming is the self-propulsion of a person through water, such as saltwater or freshwater environments, usually for recreation, sport, exercise, or survival. Swimmers achieve locomotion by coordinating limb and body movements to achieve hydrody ...

(instructional)

* Tennis

Tennis is a List of racket sports, racket sport that is played either individually against a single opponent (singles (tennis), singles) or between two teams of two players each (doubles (tennis), doubles). Each player uses a tennis racket st ...

(instructional)

* Volleyball

Volleyball is a team sport in which two teams of six players are separated by a net. Each team tries to score points by grounding a ball on the other team's court under organized rules. It has been a part of the official program of the Summ ...

(girls')

* Volleyball

Volleyball is a team sport in which two teams of six players are separated by a net. Each team tries to score points by grounding a ball on the other team's court under organized rules. It has been a part of the official program of the Summ ...

(instructional)

* Water polo

Water polo is a competitive sport, competitive team sport played in water between two teams of seven players each. The game consists of four quarters in which the teams attempt to score goals by throwing the water polo ball, ball into the oppo ...

(boys')

* Yoga

Yoga (UK: , US: ; 'yoga' ; ) is a group of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines that originated with its own philosophy in ancient India, aimed at controlling body and mind to attain various salvation goals, as pra ...

* Zumba

Winter athletic offerings

* Basketball

Basketball is a team sport in which two teams, most commonly of five players each, opposing one another on a rectangular Basketball court, court, compete with the primary objective of #Shooting, shooting a basketball (ball), basketball (appro ...

* Basketball (intramural)

* Dance (Ballet, Modern, Hip-Hop; Beg–Adv levels)

* FIT (Fundamentals In Training)

* Gunga FIT ("extreme" version of FIT)

* Hockey

''Hockey'' is a family of List of stick sports, stick sports where two opposing teams use hockey sticks to propel a ball or disk into a goal. There are many types of hockey, and the individual sports vary in rules, numbers of players, apparel, ...

* Hockey (intramural)

* Indoor cycling

Indoor cycling, often called spinning, is a form of exercise with classes focusing on endurance, strength, intervals, high intensity (race days) and recovery, and involves using a special stationary exercise bicycle with a weighted flywheel in a c ...

(instructional/cycling pre-season)

* Indoor track

* Junior Basketball (intramural)

* Nordic skiing

Nordic skiing encompasses the various types of skiing in which the toe of the ski boot is fixed to the binding in a manner that allows the heel to rise off the ski, unlike alpine skiing, where the boot is attached to the ski from toe to heel. Re ...

* Outdoor Pursuits (S&R)

* Recreational cross-country skiing

Cross-country skiing is a form of skiing whereby skiers traverse snow-covered terrain without use of ski lifts or other assistance. Cross-country skiing is widely practiced as a sport and recreational activity; however, some still use it as a m ...

* SLAM (Spirit Leaders heerleading

* Squash

* Squash (intramural)

* Swimming

Swimming is the self-propulsion of a person through water, such as saltwater or freshwater environments, usually for recreation, sport, exercise, or survival. Swimmers achieve locomotion by coordinating limb and body movements to achieve hydrody ...

and diving

Diving most often refers to:

* Diving (sport), the sport of jumping into deep water

* Underwater diving, human activity underwater for recreational or occupational purposes

Diving or Dive may also refer to:

Sports

* Dive (American football), ...

* Wrestling

Wrestling is a martial art, combat sport, and form of entertainment that involves grappling with an opponent and striving to obtain a position of advantage through different throws or techniques, within a given ruleset. Wrestling involves di ...

* Yoga

* Zumba

Spring athletic offerings

* Baseball

Baseball is a bat-and-ball games, bat-and-ball sport played between two team sport, teams of nine players each, taking turns batting (baseball), batting and Fielding (baseball), fielding. The game occurs over the course of several Pitch ...

* Crew

* Cycling

Cycling, also known as bicycling or biking, is the activity of riding a bicycle or other types of pedal-driven human-powered vehicles such as balance bikes, unicycles, tricycles, and quadricycles. Cycling is practised around the world fo ...

* Dance (Ballet, Modern, Hip-Hop; Beg–Adv levels)

* Fencing (instructional)

* FIT (Fundamentals In Training)

* Golf

Golf is a club-and-ball sport in which players use various Golf club, clubs to hit a Golf ball, ball into a series of holes on a golf course, course in as few strokes as possible.

Golf, unlike most ball games, cannot and does not use a standa ...

* Gunga FIT ("extreme" version of FIT)

* Lacrosse

Lacrosse is a contact team sport played with a lacrosse stick and a lacrosse ball. It is the oldest organized sport in North America, with its origins with the indigenous people of North America as early as the 12th century. The game w ...

* Outdoor Pursuits (S&R)

* Pilates

* Softball

Softball is a Variations of baseball, variation of baseball, the difference being that it is played with a larger ball, on a smaller field, and with only underhand pitches (where the ball is released while the hand is primarily below the ball) ...

* Squash (instructional)

* Swimming (instructional)

* Tennis

* Tennis (intramural)

* Track

* Ultimate Frisbee

* Ultimate Frisbee (intramural)

* Volleyball (boys')

* Water polo (girls')

* Yoga

Finances

Endowment and expenses

As of September 2024, Phillips Academy'sfinancial endowment

A financial endowment is a legal structure for managing, and in many cases indefinitely perpetuating, a pool of Financial instrument, financial, real estate, or other investments for a specific purpose according to Donor intent, the will of its fo ...

was $1.41 billion. In its Internal Revenue Service

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is the revenue service for the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, which is responsible for collecting Taxation in the United States, U.S. federal taxes and administerin ...

filings for the 2021–22 school year, the academy reported $110.2 million in program service expenses and $22.9 million in grants (primarily student financial aid

Student financial aid (or student financial support, or student aid) is financial support given to individuals who are furthering their education. Student financial aid can come in a number of forms, including scholarships, Grant (money), grants, ...

).

The academy conducted a "record-setting" fundraising campaign from 2017 to 2023, raising $408.9 million. The campaign added over $103 million to the academy's financial aid endowment and raised $121 million to upgrade health, dormitory, library, music, and athletic facilities.

Tuition and financial aid

In the 2024–25 school year, Phillips Academy charged boarding students $73,780 and day students $57,190, of which financial aid covers approximately $58,000 for boarding students. The academy has aneed-blind admission

Need-blind admission in the United States refers to a College admissions in the United States, college admission policy that does not take into account an applicant's financial status when deciding whether to accept them. This approach typically re ...

policy, and 47% of students receive financial aid. The academy also commits to meet 100% of each admitted student's demonstrated financial need, as determined by the academy's financial aid department.

In the twenty-first century, tuition charges at Phillips Academy have significantly increased. In the 2018–19 academic year, Phillips Academy charged boarding students $55,800 and day students $43,300, placing it among the most expensive boarding schools in the world.

Controversies

In 2013, Phillips Academy drew national attention for apparent bias against girls and women, as highlighted by a low number of girls in student leadership. Reports in 2016 and 2017 identified several former teachers who had engaged in inappropriate sexual contact with students in the past. The academy hired an independent law firm to investigate allegations of misconduct, and the head of school,John Palfrey

John Gorham Palfrey VII (born 1972) is an American educator, scholar, and law professor. His areas of focus include emerging media, Internet censorship, Internet freedom, online Transparency (social), transparency and accountability, and child sa ...

, and the head of the Board of Trustees, Peter Currie, sent an email to the Andover community stating that such transgressions must not recur.

In 2020, an Instagram

Instagram is an American photo sharing, photo and Short-form content, short-form video sharing social networking service owned by Meta Platforms. It allows users to upload media that can be edited with Social media camera filter, filters, be ...

account, @blackatandover, began circulating stories from anonymous current and former Black-identifying students, many of whom detailed personal experiences with racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one Race (human categorization), race or ethnicity over another. It may also me ...

at Phillips Academy. Several individuals raised concerns about Phillips Academy's disciplinary system, including perceived racial disparities in outcomes, a perceived emphasis on punishment over restorative justice

Restorative justice is a community-based approach to justice that aims to repair the harm done to victims, offenders and communities. In doing so, restorative justice practitioners work to ensure that offenders take responsibility for their ac ...

, and an apparent lack of due process

Due process of law is application by the state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to a case so all legal rights that are owed to a person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual p ...

in discipline procedure outlined by the student handbook. The @blackatandover account was reported on by ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'', prompting academy officials to form an "Anti-Racism Task Force", which released a final report in March 2022.

Notable alumni

George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushBefore the outcome of the 2000 United States presidential election, he was usually referred to simply as "George Bush" but became more commonly known as "George H. W. Bush", "Bush Senior," "Bush 41," and even "Bush th ...

File:George-W-Bush.jpeg, President George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

File:Josiah Quincy 1772-1864.jpg, Josiah Quincy III

Josiah Quincy III (; February 4, 1772 – July 1, 1864) was an American educator and political figure. He was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives (1805–1813), mayor of Boston (1823–1828), and President of Harvard University (182 ...

File:BurroughsEdgarRice.jpg, Edgar Rice Burroughs

Edgar Rice Burroughs (September 1, 1875 – March 19, 1950) was an American writer, best known for his prolific output in the adventure, science fiction, and fantasy genres. Best known for creating the characters Tarzan (who appeared in ...

File:Jessica_Livingston_in_2007.jpg, Jessica Livingston

File:Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr 1859-cropped.jpg, Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.

File:Humphrey Bogart publicity.jpg, Humphrey Bogart

Humphrey DeForest Bogart ( ; December 25, 1899 – January 14, 1957), nicknamed Bogie, was an American actor. His performances in classic Hollywood cinema made him an American cultural icon. In 1999, the American Film Institute selected Bogart ...

File:Jack Lemmon - 1968.jpg, Jack Lemmon

John Uhler Lemmon III (February 8, 1925 – June 27, 2001) was an American actor. Considered proficient in both dramatic and comic roles, he was known for his anxious, middle-class everyman screen persona in comedy-drama films. He received num ...

File:Bill Belichick 2012 Shankbone.JPG, Bill Belichick

File:Lachlan Murdoch in May 2013.jpg, Lachlan Murdoch

Lachlan Keith Murdoch (; born 8 September 1971) is a British and Australian businessman and mass media heir. He is the son of the media Business magnate, tycoon Rupert Murdoch. He is the executive chairman of Nova Entertainment, chairman of N ...

George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushBefore the outcome of the 2000 United States presidential election, he was usually referred to simply as "George Bush" but became more commonly known as "George H. W. Bush", "Bush Senior," "Bush 41," and even "Bush th ...

and George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

), a Supreme Court justice (William Henry Moody

William Henry Moody (December 23, 1853 – July 2, 1917) was an American politician and jurist who held positions in all three branches of the Government of the United States. He represented parts of Essex County, Massachusetts, Essex Count ...

), six Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, military decoration and is awarded to recognize American United States Army, soldiers, United States Navy, sailors, Un ...

recipients (Civil War: 2; Spanish–American War: 1; World War II: 2; Korean War: 1), five Nobel laureates

The Nobel Prizes (, ) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make outstanding contributions in th ...

(making it one of only four secondary schools in the world to have educated five or more Nobel Prize winners), as well as winners of Tony, Grammy

The Grammy Awards, stylized as GRAMMY, and often referred to as The Grammys, are awards presented by The Recording Academy of the United States to recognize outstanding achievements in music. They are regarded by many as the most prestigious a ...

, Emmy

The Emmy Awards, or Emmys, are an extensive range of awards for artistic and technical merit for the television industry. A number of annual Emmy Award ceremonies are held throughout the year, each with their own set of rules and award catego ...

and Academy Awards

The Academy Awards, commonly known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit in film. They are presented annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) in the United States in recognition of excellence in ...

. It has educated numerous billionaires, including venture capitalist Tim Draper; private equity pioneer Ted Forstmann; oil heir and environmental philanthropist Ed Bass

Edward Perry "Ed" Bass (born September 10, 1945) is an American businessman, financier, philanthropist and environmentalist who lives in Fort Worth, Texas. He financed the Biosphere 2, Biosphere 2 project, an artificial closed ecological s ...

; Rahim Al-Hussaini Aga Khan V, 50th Imam of the Ismaili Muslims, and media heir Lachlan Murdoch

Lachlan Keith Murdoch (; born 8 September 1971) is a British and Australian businessman and mass media heir. He is the son of the media Business magnate, tycoon Rupert Murdoch. He is the executive chairman of Nova Entertainment, chairman of N ...

.

Other notable alumni

* Alexander Trowbridge, U.S. Secretary of Commerce * Anjali Sud, American Businesswoman, CEO ofTubi

Tubi (stylized as tubi) is an American over-the-top ad-supported streaming television service owned by Fox Corporation since 2020. The service was launched on April 1, 2014, and is based in Los Angeles, California. In 2023, Tubi, Credible L ...

*Benjamin Spock

Benjamin McLane Spock (May 2, 1903–March 15, 1998), widely known as Dr. Spock, was an American pediatrician, Olympian athlete and left-wing political activist. His book '' Baby and Child Care'' (1946) is one of the best-selling books of ...

, pediatrician

* Bill Drayton, social entrepreneur

* Bill Veeck, owner of the Chicago White Sox

The Chicago White Sox are an American professional baseball team based in Chicago. The White Sox compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) American League Central, Central Division. The club plays its ...

and Cleveland Indians

The Cleveland Guardians are an American professional baseball team based in Cleveland. The Guardians compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) American League Central, Central Division. Since , the team ...

* Buzz Bissinger, journalist

* Carl Andre, artist

*Julia Alvarez

Julia Alvarez (born March 27, 1950) is an American New Formalist poet, novelist, and essayist. She rose to prominence with the novels '' How the García Girls Lost Their Accents'' (1991), ''In the Time of the Butterflies'' (1994), and ''Yo! ...

, writer

* Charles Ruff, White House Counsel to Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician and lawyer who was the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, ...

*Chris Hughes

Christopher Hughes (born November 26, 1983) is an American entrepreneur and author who co-founded and served as spokesman for the online social directory and networking site Facebook until 2007. He was the publisher and editor-in-chief of ''The ...

, co-founder of Facebook

Facebook is a social media and social networking service owned by the American technology conglomerate Meta Platforms, Meta. Created in 2004 by Mark Zuckerberg with four other Harvard College students and roommates, Eduardo Saverin, Andre ...

* Christopher Wray, Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation

* David B. Birney, Union General during the Civil War

*David Graeber

David Rolfe Graeber (; February 12, 1961 – September 2, 2020) was an American and British anthropologist, Left-wing politics, left-wing and anarchism, anarchist social and political activist. His influential work in Social anthropology, social ...

, anthropologist and activist

*Edgar Rice Burroughs

Edgar Rice Burroughs (September 1, 1875 – March 19, 1950) was an American writer, best known for his prolific output in the adventure, science fiction, and fantasy genres. Best known for creating the characters Tarzan (who appeared in ...

, author known for creating Tarzan of the Apes

''Tarzan of the Apes'' is a 1912 novel by American writer Edgar Rice Burroughs, and the first in the Tarzan series. The story was first printed in the pulp magazine '' The All-Story'' in October 1912 before being released as a novel in June 191 ...

and John Carter of Mars

John Carter of Mars is a fictional Virginian soldier who acts as the initial protagonist of the Barsoom stories by Edgar Rice Burroughs. A veteran of the American Civil War, he is transported to the planet Mars, called Barsoom by its inhabit ...

;

* Bill Belichick, coach for the New England Patriots

The New England Patriots are a professional American football team based in the Greater Boston area. The Patriots compete in the National Football League (NFL) as a member of the American Football Conference (AFC) AFC East, East division. The Pa ...

and recipient of eight Super Bowl

The Super Bowl is the annual History of the NFL championship, league championship game of the National Football League (NFL) of the United States. It has served as the final game of every NFL season since 1966 NFL season, 1966 (with the excep ...

rings

*Humphrey Bogart

Humphrey DeForest Bogart ( ; December 25, 1899 – January 14, 1957), nicknamed Bogie, was an American actor. His performances in classic Hollywood cinema made him an American cultural icon. In 1999, the American Film Institute selected Bogart ...

, an Academy Award-winning actor considered to be one of the greatest stars of American cinema

* Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, an early feminist and social reformer

* Francis Cabot Lowell, instrumental figure in the American Industrial Revolution and namesake of Lowell, Massachusetts

Lowell () is a city in Massachusetts, United States. Alongside Cambridge, Massachusetts, Cambridge, it is one of two traditional county seat, seats of Middlesex County, Massachusetts, Middlesex County. With an estimated population of 115,554 in ...

* George Church, geneticist

*Harlan Cleveland

Harlan Cleveland (January 19, 1918 – May 30, 2008) was an American diplomat, educator, and author. He served as Lyndon B. Johnson's U.S. Ambassador to NATO from 1965 to 1969, and earlier as U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for International ...

, U.S. Ambassador to NATO

* Heather Mac Donald, political commentator

* Henry L. Stimson, U.S. Secretary of State and Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

* Hiram Bingham III, Governor of Connecticut