Philip VI Of France on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Philip VI (; 1293 – 22 August 1350), called the Fortunate (), the Catholic (''le Catholique'') and of Valois (''de Valois''), was the first

In 1328, Philip's cousin Charles IV of France died without a son, leaving his widow Jeanne of Évreux pregnant. Philip was one of the two chief claimants to the throne of France. The other was King

In 1328, Philip's cousin Charles IV of France died without a son, leaving his widow Jeanne of Évreux pregnant. Philip was one of the two chief claimants to the throne of France. The other was King

Philip entered the Hundred Years' War in a position of comparative strength.

Philip entered the Hundred Years' War in a position of comparative strength.

After the defeat at Crécy and loss of Calais, the Estates of France refused to raise money for Philip, halting his plans to counter-attack by invading England. In 1348 the

After the defeat at Crécy and loss of Calais, the Estates of France refused to raise money for Philip, halting his plans to counter-attack by invading England. In 1348 the

king of France

France was ruled by monarchs from the establishment of the kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Clovis I, king of the Fra ...

from the House of Valois, reigning from 1328 until his death in 1350. Philip's reign was dominated by the consequences of a succession dispute. When King Charles IV of France died in 1328, his nearest male relative was his sororal nephew, Edward III of England

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after t ...

, but the French nobility preferred Charles's paternal cousin, Philip of Valois.

At first, Edward seemed to accept Philip's succession, but he pressed his claim to the throne of France after a series of disagreements with Philip. The result was the beginning of the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy ...

in 1337.

After initial successes at sea, Philip's navy was annihilated at the Battle of Sluys in 1340, ensuring that the war would occur on the continent. The English took another decisive advantage at the Battle of Crécy (1346), while the Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

struck France, further destabilising the country.

In 1349, Philip bought the Province of Dauphiné from its ruined ruler, the Dauphin Humbert II, and entrusted the government of this province to his grandson, Prince Charles. Philip VI died in 1350 and was succeeded by his son John II.

Early life

Little is recorded about Philip's childhood and youth, in large part because he was of minor royal birth. Philip's father,Charles, Count of Valois

Charles, Count of Valois (12 March 1270 – 16 December 1325), was a member of the House of Capet and founder of the House of Valois, which ruled over France from 1328. He was the fourth son of King Philip III of France and Isabella o ...

, was the younger brother of King Philip IV of France

Philip IV (April–June 1268 – 29 November 1314), called Philip the Fair (), was King of France from 1285 to 1314. Jure uxoris, By virtue of his marriage with Joan I of Navarre, he was also King of Navarre and Count of Champagne as Philip&n ...

. Charles had striven throughout his life to gain the throne for himself but was never successful. He died in 1325, leaving his eldest son Philip as heir to the counties of Anjou, Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

, and Valois.Elizabeth Hallam and Judith Everard, ''Capetian France 987–1328'', 2nd edition, (Pearson Education Limited, 2001), 366.

Accession to the throne

In 1328, Philip's cousin Charles IV of France died without a son, leaving his widow Jeanne of Évreux pregnant. Philip was one of the two chief claimants to the throne of France. The other was King

In 1328, Philip's cousin Charles IV of France died without a son, leaving his widow Jeanne of Évreux pregnant. Philip was one of the two chief claimants to the throne of France. The other was King Edward III of England

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after t ...

, who was Charles's nephew and closest male relative, being the son of Charles's sister Isabella of France. The Estates General had decided 12 years earlier that women could not inherit the throne of France. The question arose as to whether Isabella should have been able to transmit a claim that she herself did not possess. Jonathan Sumption, ''The Hundred Years War: Trial by Battle'', Vol. I, (Faber & Faber, 1990), 106–107. The assemblies of the French barons and prelates and the University of Paris

The University of Paris (), known Metonymy, metonymically as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, from 1150 to 1970, except for 1793–1806 during the French Revolution. Emerging around 1150 as a corporation associated wit ...

decided that males who derive their right to inheritance through their mother should be excluded according to Salic law

The Salic law ( or ; ), also called the was the ancient Frankish Civil law (legal system), civil law code compiled around AD 500 by Clovis I, Clovis, the first Frankish King. The name may refer to the Salii, or "Salian Franks", but this is deba ...

. As Philip was the eldest grandson of Philip III of France through the male line, he became regent instead of Edward, who was a maternal grandson of Philip IV and great-grandson of Philip III.

During the period in which Queen Jeanne was waiting to deliver her child, Philip of Valois rose to the regency with support of the French magnates, following the pattern set up by his cousin, Philip V of France, who succeeded to the throne over his niece Joan. Philip formally held the regency from 9 February until 1 April 1328. On 1 April, Jeanne of Évreux gave birth to a daughter named Blanche, following which Philip was proclaimed king. He was crowned at the Cathedral in Reims on 29 May 1328. After his elevation to the throne, Philip sent the Abbot of Fécamp, Pierre Roger, to summon Edward III of England to pay homage for the duchy of Aquitaine

The Duchy of Aquitaine (, ; , ) was a historical fiefdom located in the western, central, and southern areas of present-day France, south of the river Loire. The full extent of the duchy, as well as its name, fluctuated greatly over the centuries ...

and Gascony

Gascony (; ) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part of the combined Province of Guyenne and Gascon ...

.Jonathan Sumption, ''The Hundred Years War: Trial by Battle'', 109-110. After a subsequent second summons from Philip, Edward finally arrived at the Cathedral of Amiens on 6 June 1329 and worded his vows in such a way to cause more disputes in later years.

The dynastic change had another consequence: Charles IV had also been King of Navarre

This is a list of the kings and queens of kingdom of Pamplona, Pamplona, later kingdom of Navarre, Navarre. Pamplona was the primary name of the kingdom until its union with Kingdom of Aragon, Aragon (1076–1134). However, the territorial desig ...

, but, unlike the crown of France, the crown of Navarre was not subject to Salic law. Philip VI was neither an heir nor a descendant of Joan I of Navarre, whose inheritance (the kingdom of Navarre

Navarre ( ; ; ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre, is a landlocked foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, bordering the Basque Autonomous Community, La Rioja, and Aragon in Spain and New Aquitaine in France. ...

, as well as the counties of Champagne

Champagne (; ) is a sparkling wine originated and produced in the Champagne wine region of France under the rules of the appellation, which demand specific vineyard practices, sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within it, spe ...

, Troyes

Troyes () is a Communes of France, commune and the capital of the Departments of France, department of Aube in the Grand Est region of north-central France. It is located on the Seine river about south-east of Paris. Troyes is situated within ...

, Meaux, and Brie) had been in personal union with the crown of France for almost fifty years and had long been administered by the same royal machinery established by King Philip IV, the father of French bureaucracy. These counties were closely entrenched in the economic and administrative entity of the crown lands of France, being located adjacent to Île-de-France

The Île-de-France (; ; ) is the most populous of the eighteen regions of France, with an official estimated population of 12,271,794 residents on 1 January 2023. Centered on the capital Paris, it is located in the north-central part of the cou ...

. Philip, however, was not entitled to that inheritance; the rightful heiress was the surviving daughter of his cousin King Louis X, the future Joan II of Navarre, the heir general of Joan I of Navarre. Navarre thus passed to Joan II, with whom Philip struck a deal regarding the counties in Champagne: she received vast lands in Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

(adjacent to the fief in Évreux that her husband Philip III of Navarre owned) as compensation, and he kept Champagne as part of the French crown lands.

Reign

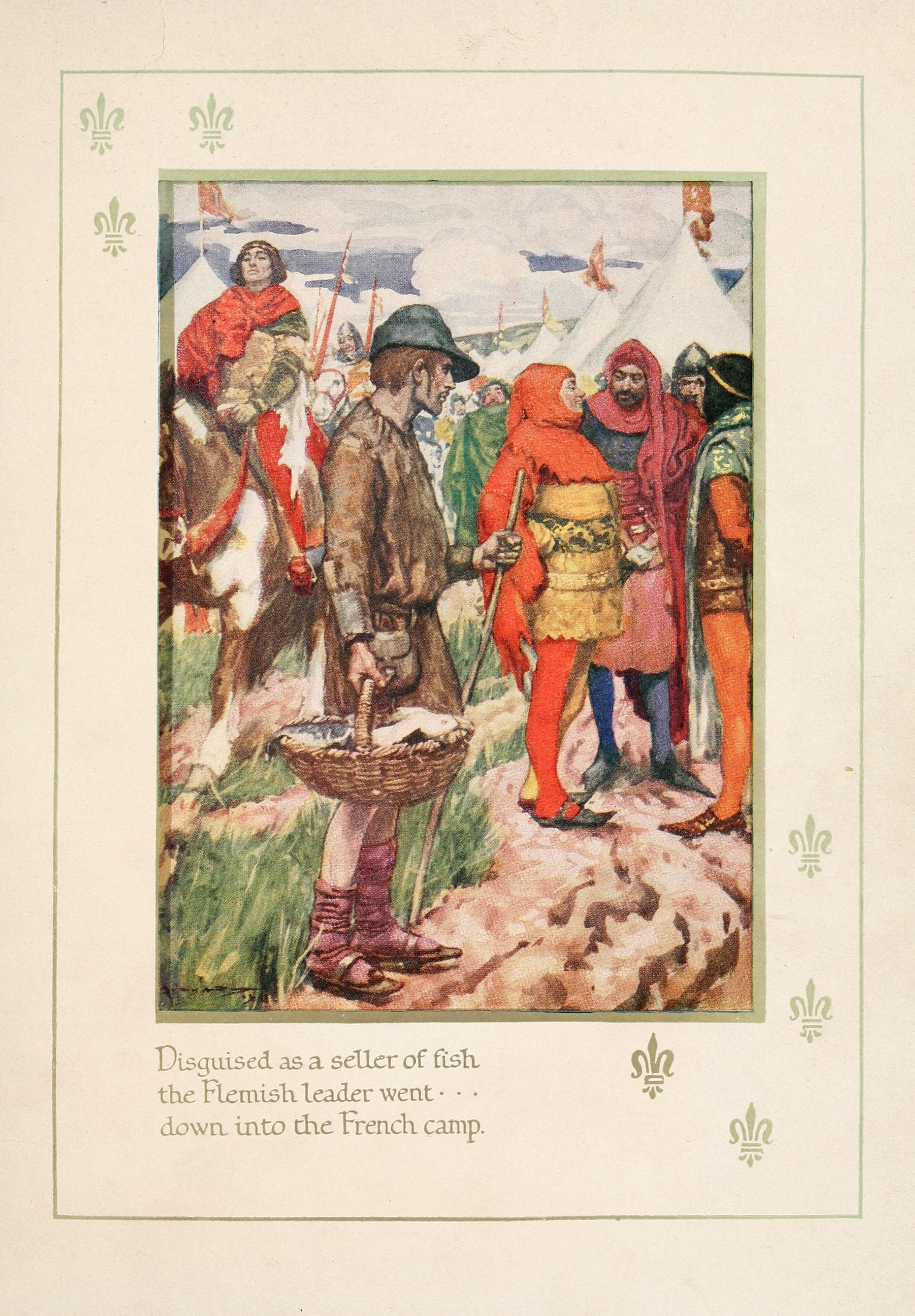

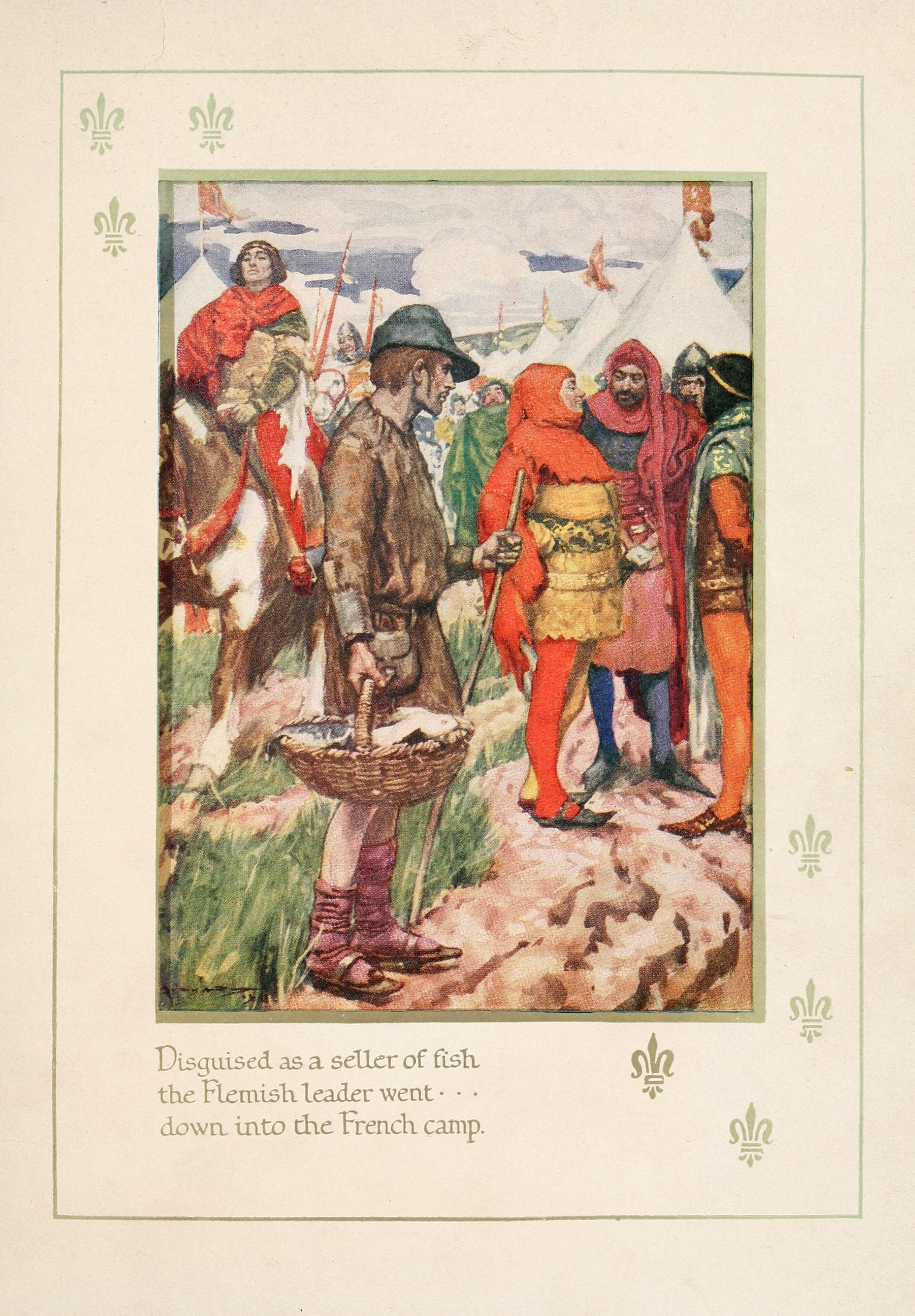

Philip's reign was plagued with crises, although it began with a military success inFlanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

at the Battle of Cassel (August 1328), where Philip's forces re-seated Louis I, Count of Flanders, who had been unseated by a popular revolution.Kelly DeVries, ''Infantry Warfare in the Early Fourteenth Century'', (The Boydell Press, 1996), 102. Philip's wife, the able Joan the Lame Joan the Lame may refer to:

* Joan of Penthièvre, Duchess of Brittany

* Joan of Burgundy, Queen of France

* Joan of France, Duchess of Berry, Queen of France

{{disambiguation, tndis ...

, gave the first of many demonstrations of her competence as regent in his absence.

Philip initially enjoyed relatively amicable relations with Edward III, and they planned a crusade together in 1332, which was never executed. However, the status of the Duchy of Aquitaine

The Duchy of Aquitaine (, ; , ) was a historical fiefdom located in the western, central, and southern areas of present-day France, south of the river Loire. The full extent of the duchy, as well as its name, fluctuated greatly over the centuries ...

remained a sore point, and tension increased. Philip provided refuge for David II of Scotland

David II (5 March 1324 – 22 February 1371) was King of Scotland from 1329 until his death in 1371. Upon the death of his father, Robert the Bruce, David succeeded to the throne at the age of five and was crowned at Scone in November 1331, be ...

in 1334 and declared himself champion of his interests, which enraged Edward. By 1336, they were enemies, although not yet openly at war.

Philip successfully prevented an arrangement between the Avignon papacy

The Avignon Papacy (; ) was the period from 1309 to 1376 during which seven successive popes resided in Avignon (at the time within the Kingdom of Arles, part of the Holy Roman Empire, now part of France) rather than in Rome (now the capital of ...

and Holy Roman Emperor Louis IV, although in July 1337 Louis concluded an alliance with Edward III. The final breach with England came when Edward offered refuge to Robert III of Artois

Robert III of Artois (1287 – between 6 October & 20 November 1342) was a French nobleman of the House of Artois. He was the Lord of Conches-en-Ouche, of Château de Domfront, Domfront, and of Mehun-sur-Yèvre, and in 1309 he received as appan ...

, formerly one of Philip's trusted advisers,Jonathan Sumption, ''The Hundred Years War:Trial by Battle'', 171–172. after Robert committed forgery to try to obtain an inheritance. As relations between Philip and Edward worsened, Robert's standing in England strengthened. On 26 December 1336, Philip officially demanded the extradition of Robert to France. On 24 May 1337, Philip declared that Edward had forfeited Aquitaine for disobedience and for sheltering the "king's mortal enemy", Robert of Artois. Thus began the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy ...

, complicated by Edward's renewed claim to the throne of France in retaliation for the forfeiture of Aquitaine.

Hundred Years' War

Philip entered the Hundred Years' War in a position of comparative strength.

Philip entered the Hundred Years' War in a position of comparative strength. France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

was richer and more populous than England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

and was at the height of its medieval glory. The opening stages of the war, accordingly, were largely successful for the French.

At sea, French privateers raided and burned towns and shipping all along the southern and southeastern coasts of England. The English made some retaliatory raids, including the burning of a fleet in the harbour of Boulogne-sur-Mer

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; ; ; or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Hauts-de-France, Northern France. It is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Pas-de-Calais. Boul ...

,Jonathan Sumption, ''The Hundred Years War:Trial by Battle'', 320–328. but the French largely had the upper hand. With his sea power established, Philip gave orders in 1339 to begin assembling a fleet off the Zeeland

Zeeland (; ), historically known in English by the Endonym and exonym, exonym Zealand, is the westernmost and least populous province of the Netherlands. The province, located in the southwest of the country, borders North Brabant to the east ...

coast at Sluys. In June 1340, however, in the bitterly fought Battle of Sluys, the English attacked the port and captured or destroyed the ships there, ending the threat of an invasion.

On land, Edward III largely concentrated upon Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

and the Low Countries

The Low Countries (; ), historically also known as the Netherlands (), is a coastal lowland region in Northwestern Europe forming the lower Drainage basin, basin of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and consisting today of the three modern "Bene ...

, where he had gained allies through diplomacy and bribery. A raid in 1339 (the first '' chevauchée'') into Picardy

Picardy (; Picard language, Picard and , , ) is a historical and cultural territory and a former regions of France, administrative region located in northern France. The first mentions of this province date back to the Middle Ages: it gained it ...

ended ignominiously when Philip wisely refused to give battle. Edward's slender finances would not permit him to play a waiting game, and he was forced to withdraw into Flanders and return to England to raise more money. In July 1340, Edward returned and mounted the siege of Tournai. By September 1340, Edward was in financial distress, hardly able to pay or feed his troops, and was open to dialogue.Jonathan Sumption, ''The Hundred Years War:Trial by Battle'', 354–359. After being at Bouvines for a week, Philip was finally persuaded to send Joan of Valois, Countess of Hainaut, to discuss terms to end the siege. On 23 September 1340, a nine-month truce was reached.

So far, the war had gone quite well for Philip and the French. While often stereotyped as chivalry-besotted and incompetent, Philip and his men had in fact carried out a successful Fabian strategy against the debt-plagued Edward and resisted the chivalric blandishments of single combat or a combat of two hundred knights that he offered. In 1341, the War of the Breton Succession

The War of the Breton Succession (, ) or Breton Civil War was a conflict between the Counts of Blois and the Montfort of Brittany, Montforts of Brittany for control of the Duchy of Brittany, then a fief of the Kingdom of France. It was fou ...

allowed the English to place permanent garrisons in Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

. However, Philip was still in a commanding position: during negotiations arbitrated by the pope in 1343, he refused Edward's offer to end the war in exchange for the Duchy of Aquitaine

The Duchy of Aquitaine (, ; , ) was a historical fiefdom located in the western, central, and southern areas of present-day France, south of the river Loire. The full extent of the duchy, as well as its name, fluctuated greatly over the centuries ...

in full sovereignty.

The next attack came in 1345, when the Earl of Derby overran the Agenais (lost twenty years before in the War of Saint-Sardos) and took Angoulême

Angoulême (; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Engoulaeme''; ) is a small city in the southwestern French Departments of France, department of Charente, of which it is the Prefectures of France, prefecture.

Located on a plateau overlooking a meander of ...

, while the forces in Brittany under Sir Thomas Dagworth also made gains. The French responded in the spring of 1346 with a massive counterattack against Aquitaine

Aquitaine (, ; ; ; ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne (), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former Regions of France, administrative region. Since 1 January 2016 it has been part of the administ ...

, where an army under John, Duke of Normandy, besieged Derby at Aiguillon. On the advice of Godfrey Harcourt (like Robert III of Artois

Robert III of Artois (1287 – between 6 October & 20 November 1342) was a French nobleman of the House of Artois. He was the Lord of Conches-en-Ouche, of Château de Domfront, Domfront, and of Mehun-sur-Yèvre, and in 1309 he received as appan ...

, a banished French nobleman), Edward sailed for Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

instead of Aquitaine. As Harcourt predicted, the Normans

The Normans (Norman language, Norman: ''Normaunds''; ; ) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norsemen, Norse Viking settlers and locals of West Francia. The Norse settlements in West Franc ...

were ill-prepared for war, and many of the fighting men were at Aiguillon. Edward sacked and burned the country as he went, taking Caen and advancing as far as Poissy and then retreating before the army Philip had hastily assembled at Paris. Slipping across the Somme, Edward drew up to give battle at Crécy.

Close behind him, Philip had planned to halt for the night and reconnoitre the English position before giving battle the next day. However, his troops were disorderly, and the roads were jammed by the rear of the army coming up and the local peasantry, which furiously called for vengeance on the English. Finding them hopeless to control, he ordered a general attack as evening fell. Thus began the Battle of Crécy. When it was done, the French army had been annihilated and a wounded Philip barely escaped capture. Fortune had turned against the French.

The English seized and held the advantage. Normandy called off the siege of Aiguillon and retreated northward, while Sir Thomas Dagworth captured Charles of Blois in Brittany. The English army pulled back from Crécy to mount the siege of Calais; the town held out stubbornly, but the English were determined, and they easily supplied across the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

. Philip led out a relieving army in July 1347, but unlike the Siege of Tournai, it was now Edward who had the upper hand. With the plunder of his Norman expedition and the reforms he had executed in his tax system, he could hold to his siege lines and await an attack that Philip dared not deliver. It was Philip who marched away in August, and the city capitulated shortly thereafter.

Final years

After the defeat at Crécy and loss of Calais, the Estates of France refused to raise money for Philip, halting his plans to counter-attack by invading England. In 1348 the

After the defeat at Crécy and loss of Calais, the Estates of France refused to raise money for Philip, halting his plans to counter-attack by invading England. In 1348 the Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

struck France and in the next few years killed one-third of the population, including Queen Joan. The resulting labour shortage caused inflation to soar, and the king attempted to fix prices, further destabilising the country. His second marriage to his son's betrothed Blanche of Navarre alienated his son and many nobles from the king.

Philip's last major achievement was the acquisition of the Dauphiné

The Dauphiné ( , , ; or ; or ), formerly known in English as Dauphiny, is a former province in southeastern France, whose area roughly corresponded to that of the present departments of Isère, Drôme and Hautes-Alpes. The Dauphiné was ...

and the territory of Montpellier

Montpellier (; ) is a city in southern France near the Mediterranean Sea. One of the largest urban centres in the region of Occitania (administrative region), Occitania, Montpellier is the prefecture of the Departments of France, department of ...

in the Languedoc

The Province of Languedoc (, , ; ) is a former province of France.

Most of its territory is now contained in the modern-day region of Occitanie in Southern France. Its capital city was Toulouse. It had an area of approximately .

History

...

in 1349. At his death in 1350, France was very much a divided country filled with social unrest. Philip VI died at Coulombes Abbey, Eure-et-Loir

Eure-et-Loir (, locally: ) is a French department, named after the Eure and Loir rivers. It is located in the region of Centre-Val de Loire. In 2019, Eure-et-Loir had a population of 431,575.Saint Denis Basilica, though his

viscera

In a multicellular organism, an organ is a collection of tissues joined in a structural unit to serve a common function. In the hierarchy of life, an organ lies between tissue and an organ system. Tissues are formed from same type cells to a ...

were buried separately at the now demolished church of Couvent des Jacobins in Paris. He was succeeded by his first son by Joan of Burgundy, who became John II.

Marriages and children

Philip married twice. In July 1313, he marriedJoan the Lame Joan the Lame may refer to:

* Joan of Penthièvre, Duchess of Brittany

* Joan of Burgundy, Queen of France

* Joan of France, Duchess of Berry, Queen of France

{{disambiguation, tndis ...

(), daughter of Robert II, Duke of Burgundy, and Agnes of France, the youngest daughter of King Louis IX of France. She was thus Philip's first cousin once removed. The couple had the following children:

# King John II of France (26 April 1319 – 8 April 1364)Marguerite Keane, ''Material Culture and Queenship in 14th-century France'', (Brill, 2016), 17.

# Marie of France (1326 – 22 September 1333), who died aged only seven, but was already married to John of Brabant, the son and heir of John III, Duke of Brabant; no issue.

# Louis (born and died 17 January 1329).

# Louis (8 June 1330 – 23 June 1330)

# A son ohn?(born and died 2 October 1333).

# A son (28 May 1335), stillborn

# Philip of Orléans (1 July 1336 – 1 September 1375), Duke of Orléans

# Joan (born and died November 1337)

# A son (born and died summer 1343)

After Joan died in 1349, Philip married Blanche of Navarre, daughter of Queen Joan II of Navarre and Philip III of Navarre, on 11 January 1350. They had one daughter:

* Joan (Blanche) of France (May 1351 – 16 September 1371), who was intended to marry John I of Aragon, but who died during the journey.

By an unknown woman he had:

* Jean d'Armagnac (died after 1350), a knight

By his mistress, Beatrice de la Berruère, he had another son:

*Thomas de la Marche (1318–1361), bâtarde de France

In fiction

Philip is a character in ''Les Rois maudits'' ('' The Accursed Kings''), a series of French historical novels by Maurice Druon. He was portrayed by Benoît Brione in the 1972 French miniseries adaptation of the series, and by Malik Zidi in the 2005 adaptation.References

Sources

* * , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Philip 06 Of France 1293 births 1350 deaths 13th-century French people 14th-century kings of France 14th-century French people 14th-century peers of France Captains General of the Church Counts of Anjou Counts of Valois Heirs presumptive to the French throne House of Valois People from Eure-et-Loir People of the Hundred Years' War Burials at the Basilica of Saint-Denis 14th-century regents