Philip Jaffe on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

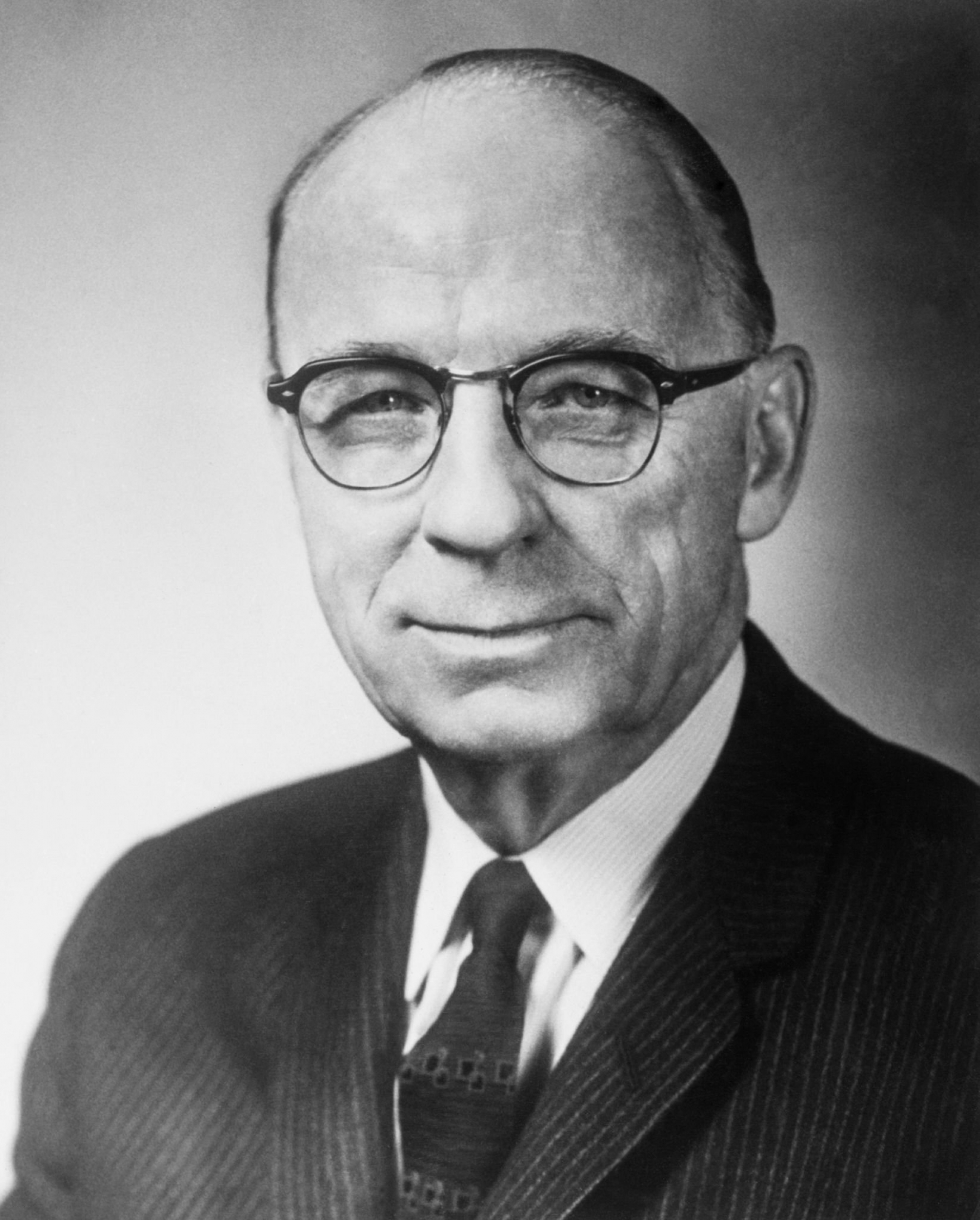

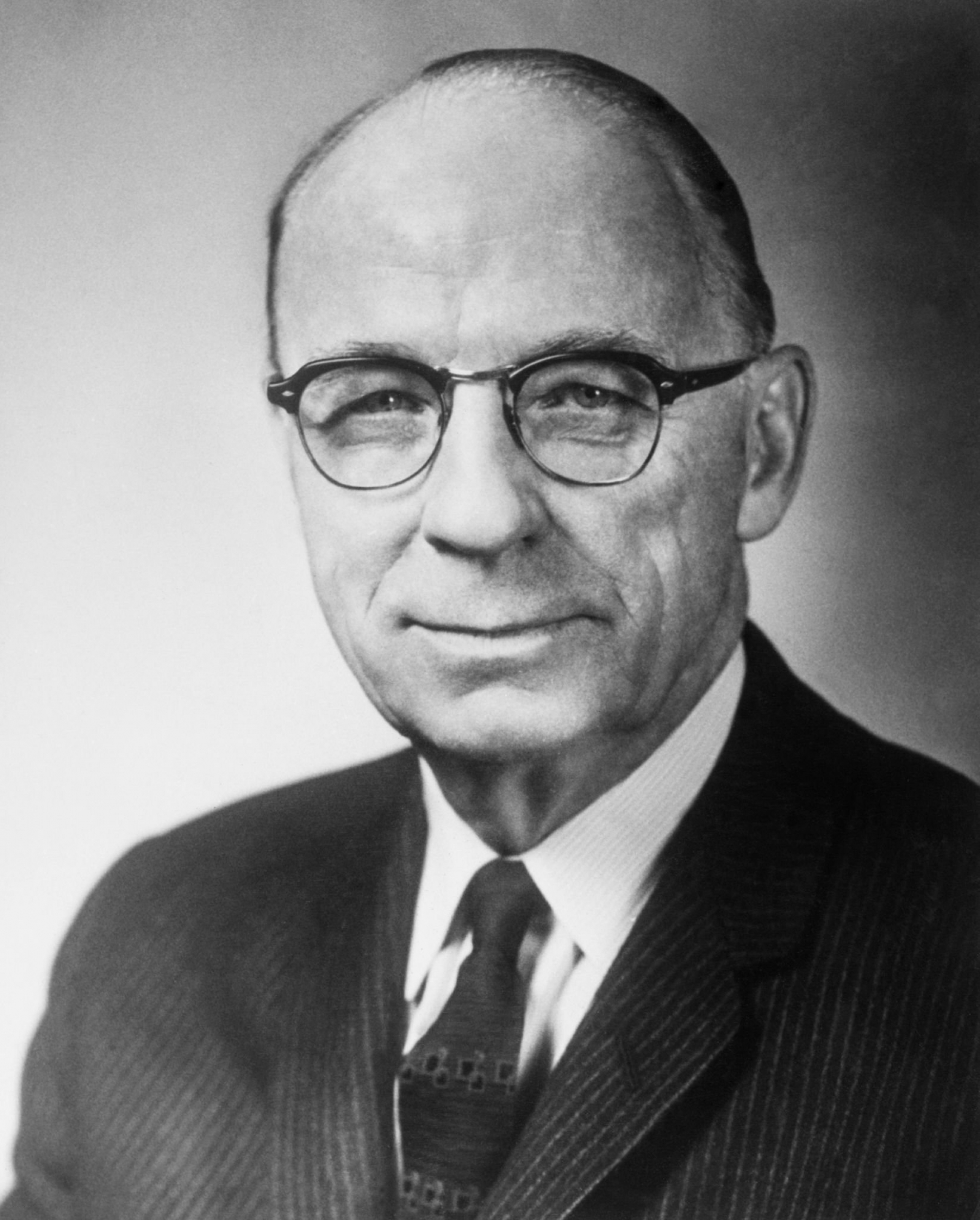

Philip Jacob Jaffe (March 20, 1895 – December 10, 1980) was a communist American businessman, editor and author. He was born in Ukraine and moved to New York City as a child. He became the owner of a profitable greeting card company. In the 1930s Jaffe became interested in Communism and edited two journals associated with the

Philip Jaffe was born in Mogileb near

Philip Jaffe was born in Mogileb near

In 1929 Jaffe met Chi Ch'ao-ting (Ji Chaoding), who had married Jaffe's cousin, Harriet Levine, in 1927. Chi had just returned from Moscow, where he had been a translator for the Chinese delegation to the 6th congress of the

In 1929 Jaffe met Chi Ch'ao-ting (Ji Chaoding), who had married Jaffe's cousin, Harriet Levine, in 1927. Chi had just returned from Moscow, where he had been a translator for the Chinese delegation to the 6th congress of the

By 1945 ''Amerasia'' had a circulation of about 2,000 and was published on an irregular schedule.

Roughly one third of the copies went to government offices. In 1945 an official noticed a long and almost verbatim quote in ''Amerasia'' from a secret

By 1945 ''Amerasia'' had a circulation of about 2,000 and was published on an irregular schedule.

Roughly one third of the copies went to government offices. In 1945 an official noticed a long and almost verbatim quote in ''Amerasia'' from a secret

“Economic Provincialism and American Far Eastern Policy”

''

New Frontiers in Asia: A Challenge to the West

'. New York:

The Rise and Fall of American Communism

'. Horizon Press, 1975. . 236 pages. * ''The Amerasia Case from 1945 to the Present''. New York: Philip J. Jaffe, 1979. 64 pages.

Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library

Emory University

Philip J. Jaffe papers, 1936-1980

{{DEFAULTSORT:Jaffe, Philip Jacob 1895 births 1980 deaths 20th-century American non-fiction writers American communists American people of Ukrainian-Jewish descent American political writers American male non-fiction writers Polytechnic Institute of New York University alumni Emigrants from the Russian Empire to the United States 20th-century American male writers

Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA (CPUSA), officially the Communist Party of the United States of America, also referred to as the American Communist Party mainly during the 20th century, is a communist party in the United States. It was established ...

. He is known for the 1945 ''Amerasia'' affair, in which the FBI found classified documents in the offices of his ''Amerasia

''Amerasia'' was a journal of Far Eastern affairs best known for the 1940s "Amerasia Affair" in which several of its staff and their contacts were suspected of espionage and charged with unauthorized possession of government documents.

Publicat ...

'' magazine that had been given to him by State Department employee John S. Service. He received a minimal sentence due to OSS/FBI bungling of the investigation, but there were continued reviews of the affair by Congress into the 1950s. He later wrote about the rise and decline of the Communist Party in the USA.

Career

Background

Philip Jaffe was born in Mogileb near

Philip Jaffe was born in Mogileb near Poltava

Poltava (, ; , ) is a city located on the Vorskla, Vorskla River in Central Ukraine, Central Ukraine. It serves as the administrative center of Poltava Oblast as well as Poltava Raion within the oblast. It also hosts the administration of Po ...

, Russian Empire on March 20, 1895.

His father, Morris Jaffe, was a Russian-speaking Jewish lumberjack. Morris moved to the United States in 1904, temporarily leaving his family in Ekaterinoslav

Dnipro is Ukraine's fourth-largest city, with about one million inhabitants. It is located in the eastern part of Ukraine, southeast of the Ukrainian capital Kyiv on the Dnieper River, Dnipro River, from which it takes its name. Dnipro is t ...

, where Philip attended a Jewish school and experienced a pogrom in 1905. His father, who had found work as a plasterer, sent for Philip and his mother to join him in the Lower East Side

The Lower East Side, sometimes abbreviated as LES, is a historic neighborhood in the southeastern part of Manhattan in New York City. It is located roughly between the Bowery and the East River from Canal to Houston streets. Historically, it w ...

of New York City. Jaffe reached New York City in 1906 with his mother and three younger siblings. Jaffe attended Townsend Harris Hall, a very selective three-year secondary school, graduating in 1913. Jaffe studied electrical engineering at Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute

The New York University Tandon School of Engineering (commonly referred to as Tandon) is the engineering and applied sciences school of New York University. Tandon is the second oldest private engineering and technology school in the United St ...

for a year, then in 1914 transferred to City College of New York

The City College of the City University of New York (also known as the City College of New York, or simply City College or CCNY) is a Public university, public research university within the City University of New York (CUNY) system in New York ...

. He met Jay Lovestone

Jay Lovestone (15 December 1897 – 7 March 1990) was an American activist. He was at various times a member of the Socialist Party of America, a leader of the Communist Party USA, leader of a small oppositionist party, an anti-Communist and Cen ...

, who would become General Secretary of the Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA (CPUSA), officially the Communist Party of the United States of America, also referred to as the American Communist Party mainly during the 20th century, is a communist party in the United States. It was established ...

(CPUSA). He was suspended for low grades, and for a short period studied at Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

.

Career

After dropping out of university, Jaffe worked for the garment industry Board of Control, then found work as a messenger for Alexander Newmark, who ran a classified advertisement agency and was active in the Socialist Party. In 1915 Jaffe joined theSocialist Party of America

The Socialist Party of America (SPA) was a socialist political party in the United States formed in 1901 by a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party of America ...

. Philip was briefly in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

in October–November 1918. After being discharged he enrolled at Columbia again, studying during the day and continuing to work for Newmark at night. He earned a bachelor's degree at Columbia in 1920 and a master's in English literature in 1921. He had been offered a teaching position at the University of Wisconsin

A university () is an institution of tertiary education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase , which roughly means "community of teachers and scholars". Uni ...

when Agnes relapsed and had to return to the sanatorium. Jaffe went back into business and entered a partnership with Wallace Brown, a stationery distributor. Jaffe became a US citizen on May 4, 1923. The partners fell out, and Jaffe took full control of the Wallace Brown Corporation. It diversified into selling greeting cards via mail order and using housewives to sell the cards door to door, and by the early 1930s was a profitable business.

Early political activity

In 1929 Jaffe met Chi Ch'ao-ting (Ji Chaoding), who had married Jaffe's cousin, Harriet Levine, in 1927. Chi had just returned from Moscow, where he had been a translator for the Chinese delegation to the 6th congress of the

In 1929 Jaffe met Chi Ch'ao-ting (Ji Chaoding), who had married Jaffe's cousin, Harriet Levine, in 1927. Chi had just returned from Moscow, where he had been a translator for the Chinese delegation to the 6th congress of the Communist International

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internationa ...

. He had settled in New York City and had joined the Chinese Bureau of the CPUSA. Chi introduced Jaffe to communism and sparked his interest in China. Jaffe joined the International Labor Defense

The International Labor Defense (ILD) (1925–1947) was a legal advocacy organization established in 1925 in the United States as the American section of the Comintern's International Red Aid network. The ILD defended Sacco and Vanzetti, was active ...

(ILD) in 1931 at Chi's urging, and contributed to the ILD journal ''Labor Defender''. During the 1930s Chi Ch'ao-ting was a graduate student at Columbia University, studying economics. He was influenced by the German Communist emigre Karl August Wittfogel

Karl August Wittfogel (; 6 September 1896 – 25 May 1988) was a German-American playwright, historian, and sinologist. He was originally a Marxist and an active member of the Communist Party of Germany, but after the Second World War, he was ...

. Chi's 1936 dissertation on ''Key Economic Areas in Chinese History'' won the Seligman Economics Prize.

From 1933 until 1945 Jaffe was known as president of a successful company who was also an editor, lecturer, member of the board of various companies and respected by academics and government officials. He was prominent in left-wing political circles and associated with the CPUSA although never a member. He was a close friend of Communists such as the party leader Earl Browder

Earl Russell Browder (May 20, 1891 – June 27, 1973) was an American politician, spy for the Soviet Union, communist activist and leader of the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA). Browder was the General Secretary of the CP ...

, and linked with groups connected to the CPUSA such as the China Aid Society

The China Aid Society was organized by a group of progressive Koreans in the United States after Japan invaded China in 1937. It advocated anti-Japanese political action in the US, helped refugees from the Japanese invasion and supported Korean gu ...

, the League of Soviet American Friendship, and the American Friends of the Chinese People (AFCP).

Jaffe attended the first meeting of the AFCP in May 1933. He later wrote, "Except for me, all those present were obviously Communist Party members. Nevertheless, or perhaps because of this, soon after the meeting I became the Executive Secretary ... and editor of its organ ''China Today''." According to Jaffe, from its first publication dated September 7, 1933, the magazine consisted mainly of "rewrites of material (we) received on rice paper from the Chinese Communist Party

The Communist Party of China (CPC), also translated into English as Chinese Communist Party (CCP), is the founding and One-party state, sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Founded in 1921, the CCP emerged victorious in the ...

underground in Shanghai

Shanghai, Shanghainese: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: is a direct-administered municipality and the most populous urban area in China. The city is located on the Chinese shoreline on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the ...

." The three editors were Jaffe, who wrote under the pseudonym J.W. Phillips, Chi Ch'ao-ting, who mainly used the name Hansu Chan, and T. A. Bisson, who wrote as Frederick Spencer. Chi was a friend of K. P. Chen

Kwang Pu Chen (; 1880 – July 1976) was a Shanghai-based Chinese banker and State Councillor. He was the founder of the first modern Chinese savings bank, the Shanghai Commercial and Savings Bank, the Shanghai Commercial Bank, a travel agen ...

and through him later gained inside information about the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT) is a major political party in the Republic of China (Taiwan). It was the one party state, sole ruling party of the country Republic of China (1912-1949), during its rule from 1927 to 1949 in Mainland China until Retreat ...

. Jaffe collaborated with his friend Frederick Vanderbilt Field

Frederick Vanderbilt Field (April 13, 1905 – February 1, 2000) was an American leftist political activist, political writer and a great-great-grandson of railroad tycoon Cornelius "Commodore" Vanderbilt, disinherited by his wealthy relatives fo ...

to set up the journal ''Amerasia

''Amerasia'' was a journal of Far Eastern affairs best known for the 1940s "Amerasia Affair" in which several of its staff and their contacts were suspected of espionage and charged with unauthorized possession of government documents.

Publicat ...

'' in 1937 as a more moderate and less openly Communist successor to ''China Today''. However, Jaffe continued to present the Communist party line in ''Amerasia''.

After launching ''Amerasia'', in April 1937 Jaffe and his wife left for a four-month visit to the Far East. In Beijing they connected with T.A. Bisson, who had won a Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship to study there. They found a small group of Westerners interested in the Chinese Communist movement including Edgar Snow

Edgar Parks Snow (July 19, 1905 – February 15, 1972) was an American journalist known for his books and articles on communism in China and the Chinese Communist Revolution. He was the first Western journalist to give an account of the history of ...

and his wife Helen (Peggy), Owen Lattimore

Owen Lattimore (July 29, 1900 – May 31, 1989) was an American Orientalist and writer. He was an influential scholar of China and Central Asia, especially Mongolia. Although he never earned a college degree, in the 1930s he was editor of '' Pac ...

and Karl August Wittfogel

Karl August Wittfogel (; 6 September 1896 – 25 May 1988) was a German-American playwright, historian, and sinologist. He was originally a Marxist and an active member of the Communist Party of Germany, but after the Second World War, he was ...

. Snow had arranged for Lattimore, Bisson and Wittfogel to visit Yan'an

Yan'an; ; Chinese postal romanization, alternatively spelled as Yenan is a prefecture-level city in the Shaanbei region of Shaanxi Province of China, province, China, bordering Shanxi to the east and Gansu to the west. It administers several c ...

, headquarters of the Communists. Wittfogel dropped out of the expedition and the Jaffes replaced him, leaving on May 17, 1937. The Jaffe party arrived in Yan'an in mid-June in a 1924 Chevrolet with a Scandinavian driver. There they met Agnes Smedley

Agnes Smedley (February 23, 1892 – May 6, 1950) was an American journalist, writer and activist who supported the Indian Independence Movement and the Chinese Communist Revolution. Raised in a poverty-stricken miner's family in Missouri and Col ...

and Peggy Snow, and talked with the Communist party leaders Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

, Zhu De

Zhu De; (1 December 1886 – 6 July 1976) was a Chinese general, military strategist, politician and revolutionary in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Zhu was born into poverty in 1886 in Sichuan. He was adopted by a wealthy uncle at ...

and Zhou Enlai

Zhou Enlai ( zh, s=周恩来, p=Zhōu Ēnlái, w=Chou1 Ên1-lai2; 5 March 1898 – 8 January 1976) was a Chinese statesman, diplomat, and revolutionary who served as the first Premier of the People's Republic of China from September 1954 unti ...

. Huang Hua

Huang Hua (; ; January 25, 1913 – November 24, 2010) was a senior Chinese Communist revolutionary, politician, and diplomat. He served as Foreign Minister of China from 1976 to 1982, and concurrently as Vice Premier from 1980 to 1982. He was ...

, who interpreted for them, was later the Chinese Foreign Minister. Jaffe probed Mao's commitment and fidelity to the party line.

His report on the visit appeared in ''The New Masses

''New Masses'' (1926–1948) was an American Marxist magazine closely associated with the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). It was the successor to both '' The Masses'' (1911–1917) and ''The Liberator'' (1918–1924). ''New Masses'' was later merge ...

'', the CPUSA organ.

In August 1940 ''Amerasia'' published an article by Lattimore in which he predicted that China would win the Sino-Japanese War and would evict the colonial powers from their concessions in China. In turn Indochina, Indonesia, Malaya and India would seek and gain independence from the European colonial powers. Lattimore concluded, "What America must decide is whether to back a Japan that is bound to lose, or a China that is bound to win."

''Amerasia'' affair

By 1945 ''Amerasia'' had a circulation of about 2,000 and was published on an irregular schedule.

Roughly one third of the copies went to government offices. In 1945 an official noticed a long and almost verbatim quote in ''Amerasia'' from a secret

By 1945 ''Amerasia'' had a circulation of about 2,000 and was published on an irregular schedule.

Roughly one third of the copies went to government offices. In 1945 an official noticed a long and almost verbatim quote in ''Amerasia'' from a secret Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the first intelligence agency of the United States, formed during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines ...

(OSS) report. In March 1945 the OSS sent agents to search the ''Amerasia'' office for documents. Five OSS agents burgled the office, found hundreds of stolen government documents and took samples. Most of the documents seemed to have come via the United States Department of State

The United States Department of State (DOS), or simply the State Department, is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy of the United State ...

. When the OSS told the State Department of their findings, they called in the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

(FBI), which began an investigation in mid-March.

The FBI watched Jaffe and the ''Amerasia'' office for nearly three months. The voluminous FBI reports on the surveillance include data from wiretaps, hidden microphones and physical observations. On April 20, 1945, John S. Service of the State Department gave Jaffe a document at the Statler Hotel

The Statler Hotel company was one of the United States' early chains of hotels catering to traveling businessmen and tourists. It was founded by Ellsworth Milton (E. M.) Statler in Buffalo, New York.

Early ventures

In 1901, Buffalo hosted the ...

in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

The FBI report of their hidden microphone recording of this meeting said, "Service ... apparently gave Jaffe a document which dealt with matters the ationalistChinese had furnished to the United States government in confidence. Service stated that the person with whom he was associated in China would 'get his neck pretty badly wrung' if the information got out." Service later said he thought Jaffe was just a journalist, and let him have some memos he had written while in China about the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT) is a major political party in the Republic of China (Taiwan). It was the one party state, sole ruling party of the country Republic of China (1912-1949), during its rule from 1927 to 1949 in Mainland China until Retreat ...

forces and the Communists.

On June 6, 1945, FBI agents arrested Jaffe, his co-editor Kate Louise Mitchell, the journalist Mark Gayn, John Service and Emmanuel Sigurd Larsen of the State Department, and Andrew Roth of the Office of Naval Intelligence

The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) is the military intelligence agency of the United States Navy. Established in 1882 primarily to advance the Navy's modernization efforts, it is the oldest member of the U.S. Intelligence Community and serv ...

, and seized the ''Amerasia'' papers, including many government documents. The charge was espionage based on possession of classified government documents concerning US policy in China. However, the OSS had burgled the ''Amerasia'' office and the homes of several of the accused, so the evidence was tainted. A grand jury decided there was insufficient basis for criminal charges against Mitchell, Gayn and Service. The jury said the papers Service had given to Jaffe were not classified. Jaffe, Roth and Larsen were indicted for stealing, receiving or concealing Government documents, but not for espionage. The court hearing was held quietly on a Saturday morning. Jaffe pleaded guilty and was fined $2,500, an amount he paid immediately. Larsen was later fined $500, which was paid by Jaffe, and the charges against Roth were dropped.

The ''Amerasia'' case was reviewed in 1946 by a House Judiciary subcommittee chaired by representative Sam Hobbs

Samuel Francis Hobbs (October 5, 1887 – May 31, 1952) was a United States Representative from Alabama.

Biography

Born in Selma, Alabama, Hobbs attended the public schools, Callaway's Preparatory School, Marion (Alabama) Military Institut ...

. The FBI and Department of Justice tried to cover up the mistakes which had led to most charges being dropped. Senator Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican Party (United States), Republican United States Senate, U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death at age ...

revived interest in the case as part of his campaign against Communists in the State Department. In 1950 the case was investigated by the Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee on the Investigation of Loyalty of State Department Employees. Republican Senators including Bourke B. Hickenlooper

Bourke Blakemore Hickenlooper (July 21, 1896 – September 4, 1971), was an American politician and member of the Republican Party, first elected to statewide office in Iowa as lieutenant governor, then 29th Governor of Iowa, then US Senator.

...

claimed that the Administration had been covering up the ''Amerasia'' case, and the documents contained important secret information.

Assistant Attorney General James M. Mclnerney downplayed their importance and said "Hickenlooper is '100% wrong.. The records were declassified and the Justice Department delivered 1,260 documents to the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee in 1956 and 1957.

Later years

Jaffe and Field were among the founders of theCommittee for a Democratic Far Eastern Policy

The Committee for a Democratic Far Eastern Policy (CDFEP) was an organization that was active in 1945–52 in opposing US support for the Kuomintang government in China.

History

The CDFEP was founded in August 1945, towards the end of World War I ...

in August 1945, which opposed the policy of Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

's administration to support Chiang Kai-shek and his Kuomintang government in China. ''Amerasia'', losing money and subject to mounting attacks by anti-communist agitators, closed down in 1947. The final issue consisted entirely of Jaffe's article ''America: The Uneasy Victor.'' Jaffe said he now supported Truman for President, alienating many former friends who followed the CPUSA line and supported Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was the 33rd vice president of the United States, serving from 1941 to 1945, under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He served as the 11th U.S. secretary of agriculture and the 10th U.S ...

. Jaffe's company would gross $5–6 million per year at its peak in the late 1940s and early 1950s. In the late 1940s both Jaffe and Field severed their connections with the CPUSA and its associated organizations.

In 1947 his translation of Chiang Kai-shek's manifesto, ''China's Destiny'' was published together with his own critical commentary on the text.

In 1950, when asked in a congressional hearing whether he had traveled to China and had known Owen Lattimore and other figures, Jaffe claimed his privilege under the Fifth Amendment and was cited for contempt. During the peak of McCarthyism in 1951–52 the Tydings Committee

The Subcommittee on the Investigation of Loyalty of State Department Employees, more commonly referred to as the Tydings Committee, was a subcommittee authorized by in February 1950 to look into charges by Joseph R. McCarthy that he had a list of ...

subpoenaed Jaffe, and subsequently charged him with contempt of Congress, but Jaffe avoided any further punishment. Service asked that the Tydings hearings be open to the press and public. He told the committee in detail of his friendly relations with Jaffe, and said he had loaned Jaffe nine or ten memos he had written which were "factual in nature and did not contain discussion of United States political or military policy." He said he had probably been indiscreet but was certainly not guilty of treason, and was neither a Communist nor a Communist sympathizer.

After his acquittal by the Tydings committee the FBI interviewed Jaffe at length four times. On September 26, 1954, the day before a grand jury investigating Field was due to adjourn after finding nothing significant, Walter Winchell

Walter Winchell (April 7, 1897 – February 20, 1972) was a syndicated American newspaper gossip columnist and radio news commentator. Originally a vaudeville performer, Winchell began his newspaper career as a Broadway reporter, critic and c ...

claimed on the radio that Jaffe had made "a sensational statement to the FBI." Jaffe had in fact said nothing, but the grand jury voted to indict Field the next day.

Although the ''Amerasia'' case remained controversial in the academic world and in politics, Jaffe gradually faded from public attention. Browder, the Jaffes and some others continued to meet and discuss politics in a group called the "Koffee Klatsch" until Browder's death in 1973. Jaffe wrote a book, ''The Rise and Fall of American Communism'' (1975), in which he drew on his access through Browder to the party's internal discussions and memos. He wrote an autobiography, "Odyssey of a Fellow Traveler," completed in 1978 but never published. Jaffe wrote in it, "As I 'look back on us', I recognize that many still romanticize the radicalism of the thirties without acknowledging its absurdities, illusions and self-deceptions."

Private life and death

In 1918, Jaffe married Agnes Newmark (born September 25, 1898). Agnes was found to have tuberculosis a few months after the wedding, and spent three years in a sanitarium. They had no children. Philip Jaffe died age 85 on December 10, 1980, in New York City.Legacy

Jaffe assembled a large collection of material about communism, civil rights, pacifist movements, labor, and the Third World. He was particularly interested in Communism in the Soviet Union, China, India, Southeast Asia and the United States. 15,000 items were acquired by the Harry Ransom Center of theUniversity of Texas at Austin

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, or Texas) is a public university, public research university in Austin, Texas, United States. Founded in 1883, it is the flagship institution of the University of Texas System. With 53,082 stud ...

in 1960.

Emory University

Emory University is a private university, private research university in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. It was founded in 1836 as Emory College by the Methodist Episcopal Church and named in honor of Methodist bishop John Emory. Its main campu ...

in Atlanta holds his main archive. York University

York University (), also known as YorkU or simply YU), is a public university, public research university in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It is Canada's third-largest university, and it has approximately 53,500 students, 7,000 faculty and staff, ...

of Toronto, Canada, acquired material from Jaffe's collection in 1970. This consists of minutes of the Political Committee, Central Executive Committee, and Secretariat of the Workers' (Communist) Party of the United States for 1926–29.

Bibliography

Articles

* “The Rise and Fall of Earl Browder”. ''Survey'' (Spring 1972), pp. 14–65.“Economic Provincialism and American Far Eastern Policy”

''

Science & Society

''Science & Society: A Journal of Marxist Thought and Analysis'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal of Marxist scholarship. It covers economics, philosophy of science, historiography, women's studies, literature, the arts, and other soc ...

'', Vol. 5, No. 4 (Fall 1941), pp. 289–309.

Books

* ''Discussion of a Plan for an American Loan to Industrialize China''.New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

: Amerasia

''Amerasia'' was a journal of Far Eastern affairs best known for the 1940s "Amerasia Affair" in which several of its staff and their contacts were suspected of espionage and charged with unauthorized possession of government documents.

Publicat ...

, 1938. 8 pages.

* New Frontiers in Asia: A Challenge to the West

'. New York:

A. A. Knopf

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. () is an American publishing house that was founded by Blanche Knopf and Alfred A. Knopf Sr. in 1915. Blanche and Alfred traveled abroad regularly and were known for publishing European, Asian, and Latin American writers ...

, 1945. 388 pages.

**Reprinted by Read Books, 2007.

* The Rise and Fall of American Communism

'. Horizon Press, 1975. . 236 pages. * ''The Amerasia Case from 1945 to the Present''. New York: Philip J. Jaffe, 1979. 64 pages.

Contributions

*Notes

References

External sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * Includes quotations from Jaffe's ''The Amerasia Case From 1945 to the Present'' (1979) * * * * * * * * *External links

Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library

Emory University

Philip J. Jaffe papers, 1936-1980

{{DEFAULTSORT:Jaffe, Philip Jacob 1895 births 1980 deaths 20th-century American non-fiction writers American communists American people of Ukrainian-Jewish descent American political writers American male non-fiction writers Polytechnic Institute of New York University alumni Emigrants from the Russian Empire to the United States 20th-century American male writers