Philhellene on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Philhellenism ("the love of Greek culture") was an intellectual movement prominent mostly at the turn of the 19th century. It contributed to the sentiments that led Europeans such as

In antiquity, the term ''philhellene'' ("the admirer of Greeks and everything Greek"), from the (, from ''φίλος'' - ''philos'', "friend", "lover" + ''Ἕλλην'' - ''Hellen'', "Greek") was used to describe both non-Greeks who were fond of ancient Greek culture and Greeks who patriotically upheld their culture. The Liddell-Scott Greek-English Lexicon defines 'philhellene' as "fond of the Hellenes, mostly of foreign princes, as Amasis; of Parthian kings .. also of Hellenic tyrants, as Jason of Pherae and generally of Hellenic (Greek) patriots. According to

In antiquity, the term ''philhellene'' ("the admirer of Greeks and everything Greek"), from the (, from ''φίλος'' - ''philos'', "friend", "lover" + ''Ἕλλην'' - ''Hellen'', "Greek") was used to describe both non-Greeks who were fond of ancient Greek culture and Greeks who patriotically upheld their culture. The Liddell-Scott Greek-English Lexicon defines 'philhellene' as "fond of the Hellenes, mostly of foreign princes, as Amasis; of Parthian kings .. also of Hellenic tyrants, as Jason of Pherae and generally of Hellenic (Greek) patriots. According to

In

In

File:Une Assemblée d’Officiers Européens, accourus au secours de la Grèce en 1822.jpg, Depiction of Philhellenes in Greece in 1822

File:Zografos-Makriyannis 24 I Ellas evgomonousa List of Philhellenes.jpg, List of philhellenes who contributed during the

Paul Cartledge, Clare College Cambridge, "The Greeks and Anthropology"

in ''Classics Ireland'' 2 (Dublin 1995) *

''Graecomania and Philhellenism''

Terence J. B Spencer, 1973. ''Fair Greece! Sad relic: Literary philhellenism from Shakespeare to Byron''

* Caroline Winterer, 2002. ''The Culture of Classicism: Ancient Greece and Rome in American Intellectual Life, 1780–1910''. Johns Hopkins University Press.

{{Cultural appreciation Admiration of foreign cultures Ancient Greece studies Greek nationalism Theories of aesthetics Politics of the Greek War of Independence

Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824) was an English poet. He is one of the major figures of the Romantic movement, and is regarded as being among the greatest poets of the United Kingdom. Among his best-kno ...

, Charles Nicolas Fabvier and Richard Church to advocate for Greek independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. In 1826, the Greeks were assisted ...

from the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

.

The later 19th-century European philhellenism was largely to be found among the Classicists. The study of it falls under Classical Reception Studies

Classical reception studies is the study of how the classical world, especially Ancient Greek literature and Latin literature, have been received since antiquity. It is the study of the portrayal and representation of the ancient world from ancien ...

and is a continuation of the Classical tradition.

Antiquity

In antiquity, the term ''philhellene'' ("the admirer of Greeks and everything Greek"), from the (, from ''φίλος'' - ''philos'', "friend", "lover" + ''Ἕλλην'' - ''Hellen'', "Greek") was used to describe both non-Greeks who were fond of ancient Greek culture and Greeks who patriotically upheld their culture. The Liddell-Scott Greek-English Lexicon defines 'philhellene' as "fond of the Hellenes, mostly of foreign princes, as Amasis; of Parthian kings .. also of Hellenic tyrants, as Jason of Pherae and generally of Hellenic (Greek) patriots. According to

In antiquity, the term ''philhellene'' ("the admirer of Greeks and everything Greek"), from the (, from ''φίλος'' - ''philos'', "friend", "lover" + ''Ἕλλην'' - ''Hellen'', "Greek") was used to describe both non-Greeks who were fond of ancient Greek culture and Greeks who patriotically upheld their culture. The Liddell-Scott Greek-English Lexicon defines 'philhellene' as "fond of the Hellenes, mostly of foreign princes, as Amasis; of Parthian kings .. also of Hellenic tyrants, as Jason of Pherae and generally of Hellenic (Greek) patriots. According to Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; ; 355/354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian. At the age of 30, he was elected as one of the leaders of the retreating Ancient Greek mercenaries, Greek mercenaries, the Ten Thousand, who had been ...

, an honorable Greek should also be a philhellene.

Some examples:

* Evagoras of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

and Philip II were both called ''"philhellenes"'' by Isocrates

Isocrates (; ; 436–338 BC) was an ancient Greek rhetorician, one of the ten Attic orators. Among the most influential Greek rhetoricians of his time, Isocrates made many contributions to rhetoric and education through his teaching and writte ...

*The early rulers of the Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire (), also known as the Arsacid Empire (), was a major Iranian political and cultural power centered in ancient Iran from 247 BC to 224 AD. Its latter name comes from its founder, Arsaces I, who led the Parni tribe ...

, starting with Mithridates I (), used the title of philhellenes on their coins, which was a political act done in order to establish friendly relations with their Greek subjects.

*Following the example of the Parthians, Tigranes

Tigranes (, ) is the Greek rendering of the Old Iranian name ''*Tigrāna''. This was the name of a number of historical figures, primarily kings of Armenia.

The name of Tigranes, which was theophoric in nature, was uncommon during the Achae ...

adopted the title of Philhellene (''friend of the Greeks''). The layout of his capital Tigranocerta was an example of Greek architecture

Ancient Greek architecture came from the Greeks, or Hellenes, whose culture flourished on the Greek mainland, the Peloponnese, the Aegean Islands, and in colonies in Anatolia and Italy for a period from about 900 BC until the 1st century AD, w ...

.

Roman philhellenes

The literate upper classes ofAncient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

were increasingly Hellenized in their culture during the 3rd century BC.A. Wardman, 1976. ''Rome's debt to Greece''.

Among Romans the career of Titus Quinctius Flamininus

Titus Quinctius Flamininus (229 – 174 BC) was a Roman politician and general instrumental in the Roman conquest of Greece.

Family background

Flamininus belonged to the minor patrician ''gens'' Quinctia. The family had a glorious place in ...

(died 174 BC), who appeared at the Isthmian Games

Isthmian Games or Isthmia (Ancient Greek: Ἴσθμια) were one of the Panhellenic Games of Ancient Greece, and were named after the Isthmus of Corinth, where they were held. As with the Nemean Games, the Isthmian Games were held both the year be ...

in Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

in 196 BC and proclaimed the freedom of the Greek states, was fluent in Greek, stood out, according to Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding i ...

, as a great admirer of Greek culture

The culture of Greece has evolved over thousands of years, beginning in Minoan and later in Mycenaean Greece, continuing most notably into Classical Greece, while influencing the Roman Empire and its successor the Byzantine Empire. Other cultu ...

. The Greeks hailed him as their liberator. There were some Romans during the late Republic, who were distinctly anti-Greek, resenting the increasing influence of Greek culture on Roman life, an example being the Roman Censor, Cato the Elder

Marcus Porcius Cato (, ; 234–149 BC), also known as Cato the Censor (), the Elder and the Wise, was a Roman soldier, Roman Senate, senator, and Roman historiography, historian known for his conservatism and opposition to Hellenization. He wa ...

and Cato the Younger, who lived during the "Greek invasion" of Rome but towards the later years of his life he eventually became a philhellene after his stay in Rhodes.

The lyric poet Quintus Horatius Flaccus

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 BC – 27 November 8 BC),Suetonius, Life of Horace commonly known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman Lyric poetry, lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Oc ...

, often anglicized as Horace, was another philhellene. He is notable for his words, "Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit et artis intulit agresti Latio" (Conquered Greece took captive her savage conqueror and brought her arts into rustic Latium), meaning that after the conquest of Greece the defeated Greeks created a cultural hegemony over the Romans.

Horace's contemporary lyric poets, Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

and Ovid

Publius Ovidius Naso (; 20 March 43 BC – AD 17/18), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a younger contemporary of Virgil and Horace, with whom he i ...

, both produced magnum opuses (the Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan War#Sack of Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Ancient Rome ...

and the Metamorphoses

The ''Metamorphoses'' (, , ) is a Latin Narrative poetry, narrative poem from 8 Common Era, CE by the Ancient Rome, Roman poet Ovid. It is considered his ''Masterpiece, magnum opus''. The poem chronicles the history of the world from its Cre ...

, respectively) which were substantially founded upon Hellenic references and culture. Additionally, Virgil's Eclogues

The ''Eclogues'' (; , ), also called the ''Bucolics'', is the first of the three major works of the Latin poet Virgil.

Background

Taking as his generic model the Greek bucolic poetry of Theocritus, Virgil created a Roman version partly by o ...

were inspired by Theocritus

Theocritus (; , ''Theokritos''; ; born 300 BC, died after 260 BC) was a Greek poet from Sicily, Magna Graecia, and the creator of Ancient Greek pastoral poetry.

Life

Little is known of Theocritus beyond what can be inferred from his writings ...

' earlier pastoral poetry

The pastoral genre of literature, art, or music depicts an idealised form of the shepherd's lifestyle – herding livestock around open areas of land according to the seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. The target aud ...

in his idylls. The Aeneid, Virgil's story of Rome's founding myth, notably shares several similarities with Homer's earlier epics, particularly the Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; ) is one of two major epics of ancient Greek literature attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest surviving works of literature and remains popular with modern audiences. Like the ''Iliad'', the ''Odyssey'' is divi ...

, one of which being both his epic and the Odyssey follow a demigod

A demigod is a part-human and part-divine offspring of a deity and a human, or a human or non-human creature that is accorded divine status after death, or someone who has attained the "divine spark" (divine illumination). An immortality, immor ...

protagonist's military voyage after the Trojan War. It also was influenced by Homer's Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

; for example, the ekphrasis

Ekphrasis or ecphrasis (from the Greek) is a rhetorical device indicating the written description of a work of art. It is a vivid, often dramatic, verbal description of a visual work of art, either real or imagined. Thus, "an ekphrastic poem ...

of Achilles

In Greek mythology, Achilles ( ) or Achilleus () was a hero of the Trojan War who was known as being the greatest of all the Greek warriors. The central character in Homer's ''Iliad'', he was the son of the Nereids, Nereid Thetis and Peleus, ...

' divine shield from his mother, Thetis

Thetis ( , or ; ) is a figure from Greek mythology with varying mythological roles. She mainly appears as a sea nymph, a goddess of water, and one of the 50 Nereids, daughters of the ancient sea god Nereus.

When described as a Nereid in Cl ...

, was mirrored by the ekphrasis of Aeneas' divine shield from his mother, Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is often called Earth's "twin" or "sister" planet for having almost the same size and mass, and the closest orbit to Earth's. While both are rocky planets, Venus has an atmosphere much thicker ...

. Ovid's work was perhaps even more influenced by ancient Greek culture than Virgil; his Metamorphoses were inspired by the Greek epic tradition

A tradition is a system of beliefs or behaviors (folk custom) passed down within a group of people or society with symbolic meaning or special significance with origins in the past. A component of cultural expressions and folklore, common e ...

and metamorphosis poetry in the Hellenistic tradition, and its content was derived to a large extent from Greek myth

Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of ancient Greek folklore, today absorbed alongside Roman mythology into the broader designation of classical mythology. These stories concern the ancien ...

and folklore, including the Trojan War. Ovid's treatment of Greek myths was so impactful for later Philhellenism, especially during the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

, that the well-known versions of some myths are actually Ovid's versions (e.g. Echo and Narcissus). Soon after these writers, other Roman lyric poets such as Lucan

Marcus Annaeus Lucanus (3 November AD 39 – 30 April AD 65), better known in English as Lucan (), was a Roman poet, born in Corduba, Hispania Baetica (present-day Córdoba, Spain). He is regarded as one of the outstanding figures of the Imper ...

(inspired by Greek epics with his Pharsalia

''De Bello Civili'' (; ''On the Civil War''), more commonly referred to as the ''Pharsalia'' (, neuter plural), is a Latin literature, Roman Epic poetry, epic poem written by the poet Lucan, detailing the Caesar's civil war, civil war between Ju ...

) or Persius

Aulus Persius Flaccus (; 4 December 3424 November 62 AD) was a Roman poet and satirist of Etruscan origin. In his works, poems and satire, he shows a Stoic wisdom and a strong criticism for what he considered to be the stylistic abuses of his ...

(heavily inspired by Horace with his ''Life'') continued to exhibit strong interests and admirations for Greek literary, artistic, and religious culture.

Roman emperors known for their philhellenism include Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68) was a Roman emperor and the final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 until his ...

, Hadrian

Hadrian ( ; ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. Hadrian was born in Italica, close to modern Seville in Spain, an Italic peoples, Italic settlement in Hispania Baetica; his branch of the Aelia gens, Aelia '' ...

, Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus ( ; ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 and a Stoicism, Stoic philosopher. He was a member of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty, the last of the rulers later known as the Five Good Emperors ...

and Julian the Apostate

Julian (; ; 331 – 26 June 363) was the Caesar of the West from 355 to 360 and Roman emperor from 361 to 363, as well as a notable philosopher and author in Greek. His rejection of Christianity, and his promotion of Neoplatonic Hellenism ...

.

Modern times

In the period of political reaction and repression after the fall ofNapoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

, when the liberal-minded, educated and prosperous middle and upper classes of European societies found the Romantic nationalism

Romantic nationalism (also national romanticism, organic nationalism, identity nationalism) is the form of nationalism in which the state claims its political legitimacy as an organic consequence of the unity of those it governs. This includes ...

of 1789–1792 repressed by the restoration of absolute monarchy at home, the idea of the re-creation of a Greek state on the very territories that were sanctified by their view of Antiquity—which was reflected even in the furnishings of their own parlors and the contents of their bookcases—offered an ideal, set at a romantic distance. Under these conditions, the Greek uprising constituted a source of inspiration and expectations that could never actually be fulfilled, disappointing what Paul Cartledge

Paul Anthony Cartledge (born 24 March 1947)"CARTLEDGE, Prof. Paul Anthony", ''Who's Who 2010'', A & C Black, 2010online edition/ref> is a British ancient historian and academic. From 2008 to 2014 he was the A. G. Leventis Professor of Greek ...

called "the Victorian self-identification with the Glory that was Greece". American higher education was fundamentally transformed by the rising admiration of and identification with ancient Greece in the 1830s and afterward.

Another popular subject of interest in Greek culture

The culture of Greece has evolved over thousands of years, beginning in Minoan and later in Mycenaean Greece, continuing most notably into Classical Greece, while influencing the Roman Empire and its successor the Byzantine Empire. Other cultu ...

at the turn of the 19th century was the shadowy Scythian

The Scythians ( or ) or Scyths (, but note Scytho- () in composition) and sometimes also referred to as the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic people who had migrated during the 9th to 8th centuries BC fr ...

philosopher Anacharsis

Anacharsis (; ) was a Scythian prince and philosopher of uncertain historicity who lived in the 6th century BC.

Life

Anacharsis was the brother of the Scythian king Saulius, and both of them were the sons of the previous Scythian king, Gnurus ...

, who lived in the 6th century BC. The new prominence of Anacharsis was sparked by Jean-Jacques Barthélemy's fanciful '' Travels of Anacharsis the Younger in Greece'' (1788), a learned imaginary travel journal

The genre of travel literature or travelogue encompasses outdoor literature, guide books, nature writing, and travel memoirs.

History

Early examples of travel literature include the ''Periplus of the Erythraean Sea'' (generally considered a 1s ...

, one of the first historical novels

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which a fictional plot takes place in the Setting (narrative), setting of particular real past events, historical events. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literatur ...

, which a modern scholar has called "the encyclopedia of the new cult of the antique" in the late 18th century. It had a high impact on the growth of philhellenism in France: the book went through many editions, was reprinted in the United States and was translated into German and other languages. It later inspired European sympathy for the Greek War of Independence and spawned sequels and imitations throughout the 19th century.

In

In German culture

The culture of Germany has been shaped by its central position in Europe and a history spanning over a millennium. Characterized by significant contributions to art, music, philosophy, science, and technology, German culture is both diverse and ...

the first phase of philhellenism can be traced in the careers and writings of Johann Joachim Winckelmann

Johann Joachim Winckelmann ( ; ; 9 December 17178 June 1768) was a German art historian and archaeologist. He was a pioneering Hellenism (neoclassicism), Hellenist who first articulated the differences between Ancient Greek art, Greek, Helleni ...

, one of the inventors of art history, Friedrich August Wolf, who inaugurated modern Homeric scholarship

Homeric scholarship is the study of any Homeric topic, especially the two large surviving Epic poetry, epics, the ''Iliad'' and ''Odyssey''. It is currently part of the academic discipline of classical studies. The subject is one of the oldest in ...

with his ''Prolegomena ad Homerum'' (1795) and the enlightened bureaucrat Wilhelm von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Christian Karl Ferdinand von Humboldt (22 June 1767 – 8 April 1835) was a German philosopher, linguist, government functionary, diplomat, and founder of the Humboldt University of Berlin. In 1949, the university was named aft ...

. It was also in this context that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

and Friedrich Hölderlin

Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin (, ; ; 20 March 1770 – 7 June 1843) was a Germans, German poet and philosopher. Described by Norbert von Hellingrath as "the most German of Germans", Hölderlin was a key figure of German Romanticis ...

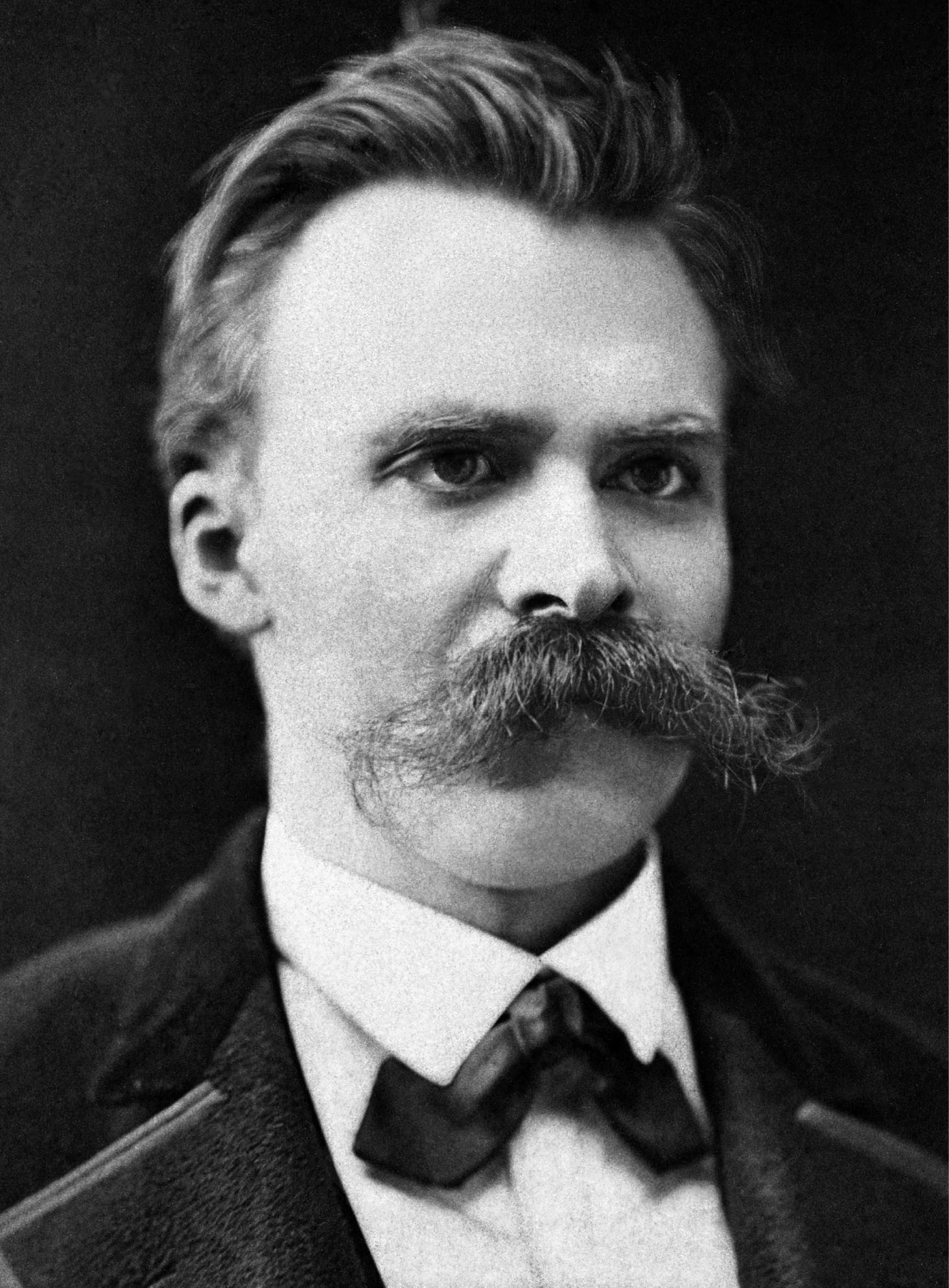

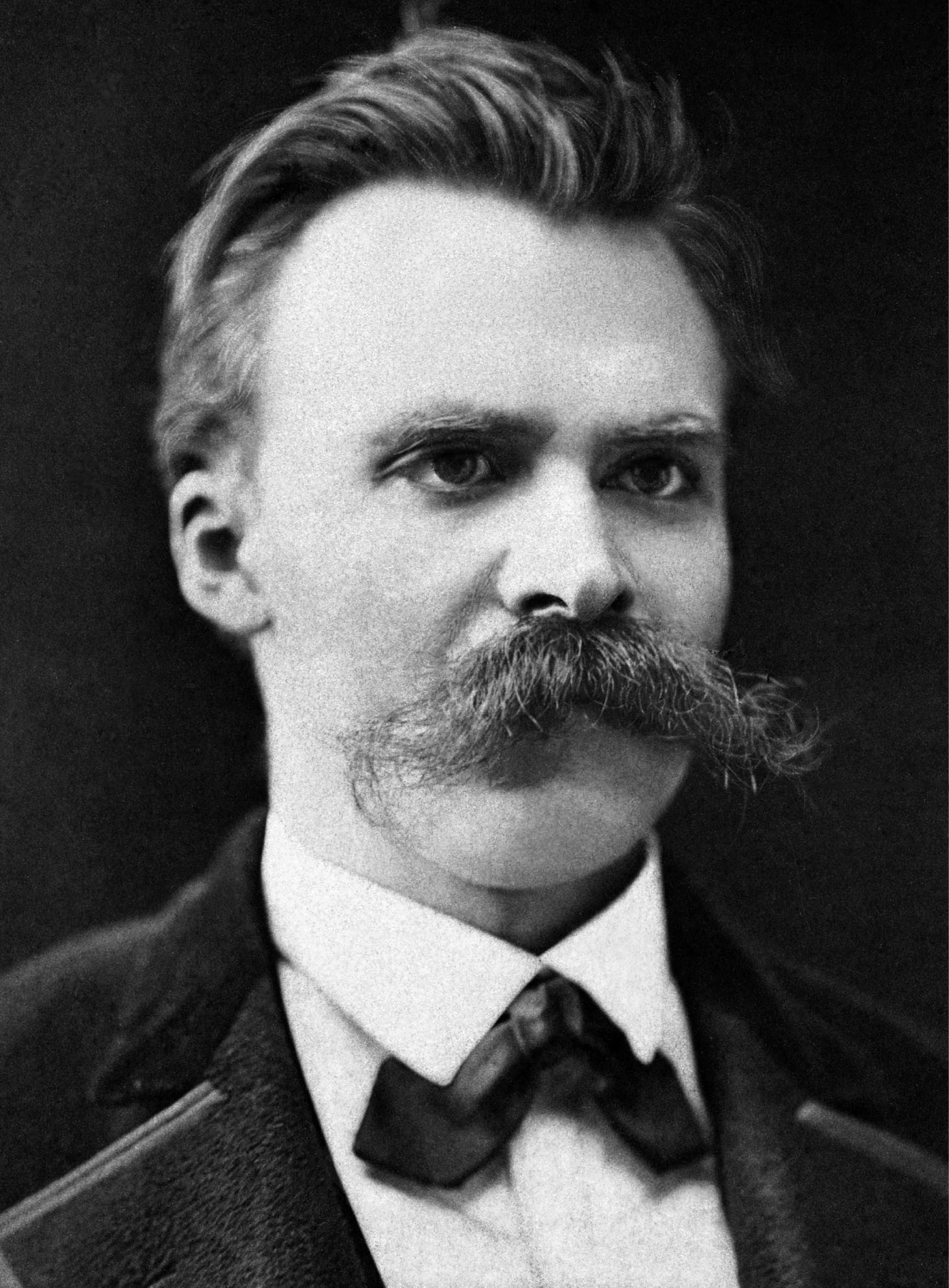

were to compose poetry and prose in the field of literature, elevating Hellenic themes in their works. One of the most renowned German philhellenes of the 19th century was Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philology, classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche bec ...

. In the German states, the private obsession with ancient Greece took public forms, institutionalizing an elite philhellene ethos

''Ethos'' is a Greek word meaning 'character' that is used to describe the guiding beliefs or ideals that characterize a community, nation, or ideology; and the balance between caution and passion. The Greeks also used this word to refer to the ...

through the '' Gymnasium'', to revitalize German education at home, and providing on two occasions high-minded philhellene German princes ignorant of modern-day Greek realities, to be Greek sovereigns.

During the later 19th century the new studies of archaeology and anthropology began to offer a quite separate view of ancient Greece, which had previously been experienced second-hand only through Greek literature

Greek literature () dates back from the ancient Greek literature, beginning in 800 BC, to the modern Greek literature of today.

Ancient Greek literature was written in an Ancient Greek dialect, literature ranges from the oldest surviving wri ...

, Greek sculpture and architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and construction, constructi ...

. Twentieth-century heirs of the 19th-century view of an unchanging, immortal quality of "Greekness" are typified in J. C. Lawson's ''Modern Greek Folklore and Ancient Greek Religion'' (1910) or R. and E. Blum's ''The Dangerous Hour: The lore of crisis and mystery in rural Greece'' (1970).

According to the Classicist Paul Cartledge

Paul Anthony Cartledge (born 24 March 1947)"CARTLEDGE, Prof. Paul Anthony", ''Who's Who 2010'', A & C Black, 2010online edition/ref> is a British ancient historian and academic. From 2008 to 2014 he was the A. G. Leventis Professor of Greek ...

, they "represent this ideological construction of Greekness as an essence, a Classicizing essence to be sure, impervious to such historic changes as that from paganism

Paganism (, later 'civilian') is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Christianity, Judaism, and Samaritanism. In the time of the ...

to Orthodox Christianity

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pag ...

, or from subsistence peasant agriculture to more or less internationally market-driven capitalist farming."

The Philhellenic movement led to the introduction of Classics

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

or ''Classical studies'' as a key element in education, introduced in the Gymnasien in Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

. In England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

the main proponent of Classics in schools was Thomas Arnold

Thomas Arnold (13 June 1795 – 12 June 1842) was an English educator and historian. He was an early supporter of the Broad Church Anglican movement. As headmaster of Rugby School from 1828 to 1841, he introduced several reforms that were widel ...

, headmaster at Rugby School

Rugby School is a Public school (United Kingdom), private boarding school for pupils aged 13–18, located in the town of Rugby, Warwickshire in England.

Founded in 1567 as a free grammar school for local boys, it is one of the oldest independ ...

.

Nikos Dimou's ''The Misfortune to be Greek'' argues that the Philhellenes' expectation for the modern Greek people

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Cyprus, southern Albania, Anatolia, parts of Italy and Egypt, and to a lesser extent, other countries surrounding the Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea. They also f ...

to live up to their ancestors' allegedly glorious past has always been a burden upon the Greeks themselves. In particular, Western Philhellenism focused exclusively on the heritage of Classical Greece, while negating or rejecting the heritage of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

and the Greek Orthodox Church

Greek Orthodox Church (, , ) is a term that can refer to any one of three classes of Christian Churches, each associated in some way with Christianity in Greece, Greek Christianity, Antiochian Greek Christians, Levantine Arabic-speaking Christian ...

, which for the Greek people are at least as important.

Art

Philhellenism also created a renewed interest in the artistic movement ofNeoclassicism

Neoclassicism, also spelled Neo-classicism, emerged as a Western cultural movement in the decorative arts, decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that drew inspiration from the art and culture of classical antiq ...

, which idealized fifth-century Classical Greek art and architecture, very much at second hand, through the writings of the first generation of art historians, like Johann Joachim Winckelmann

Johann Joachim Winckelmann ( ; ; 9 December 17178 June 1768) was a German art historian and archaeologist. He was a pioneering Hellenism (neoclassicism), Hellenist who first articulated the differences between Ancient Greek art, Greek, Helleni ...

and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (; ; 22 January 1729 – 15 February 1781) was a German philosopher, dramatist, publicist and art critic, and a representative of the Enlightenment era. His plays and theoretical writings substantially influenced the dev ...

.

The groundswell of the Philhellenic movement was result of two generations of intrepid artists and amateur treasure-seekers, from Stuart and Revett, who published their measured drawings as ''The Antiquities of Athens'' and culminating with the removal of sculptures from Aegina

Aegina (; ; ) is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina (mythology), Aegina, the mother of the mythological hero Aeacus, who was born on the island and became its king.

...

and the Parthenon

The Parthenon (; ; ) is a former Ancient Greek temple, temple on the Acropolis of Athens, Athenian Acropolis, Greece, that was dedicated to the Greek gods, goddess Athena. Its decorative sculptures are considered some of the high points of c ...

(the Elgin Marbles

The Elgin Marbles ( ) are a collection of Ancient Greek sculptures from the Parthenon and other structures from the Acropolis of Athens, removed from Ottoman Greece in the early 19th century and shipped to Britain by agents of Thomas Bruce, 7 ...

), works that inspired the British Philhellenes, many of whom, however, deplored their removal.

Greek War of Independence and later

Many well-known philhellenes supported the Greek Independence Movement such as Shelley,Thomas Moore

Thomas Moore (28 May 1779 – 25 February 1852), was an Irish writer, poet, and lyricist who was widely regarded as Ireland's "National poet, national bard" during the late Georgian era. The acclaim rested primarily on the popularity of his ''I ...

, Leigh Hunt

James Henry Leigh Hunt (19 October 178428 August 1859), best known as Leigh Hunt, was an English critic, essayist and poet.

Hunt co-founded '' The Examiner'', a leading intellectual journal expounding radical principles. He was the centre ...

, Cam Hobhouse, Walter Savage Landor

Walter Savage Landor (30 January 177517 September 1864) was an English writer, poet, and activist. His best known works were the prose ''Imaginary Conversations,'' and the poem "Rose Aylmer," but the critical acclaim he received from contempora ...

and Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 4 February Dual dating, 1747/8 Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. 5 February 1748 Old Style and New Style dates, N.S.– 6 June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of mo ...

.

Some, notably Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824) was an English poet. He is one of the major figures of the Romantic movement, and is regarded as being among the greatest poets of the United Kingdom. Among his best-kno ...

, even took up arms to join the Greek revolutionaries. Many more financed the revolution or contributed through their artistic work.

Throughout the 19th century, philhellenes continued to support Greece politically and militarily. For example, Ricciotti Garibaldi

Ricciotti Garibaldi (24 February 1847 – 17 July 1924) was an Italian soldier, the fourth son of Giuseppe Garibaldi and Anita Garibaldi.

Biography

Born in Montevideo, he was named in honour of who had been executed during the failed expeditio ...

led a volunteer expedition (''Garibaldini'') in the Greco-Turkish War of 1897

The Greco-Turkish War of 1897 or the Ottoman-Greek War of 1897 ( or ), also called the Thirty Days' War and known in Greece as the Black '97 (, ''Mauro '97'') or the Unfortunate War (), was a war fought between the Kingdom of Greece and the O ...

.Gilles Pécout, "Philhellenism in Italy: political friendship and the Italian volunteers in the Mediterranean in the nineteenth century", ''Journal of Modern Italian Studies'' 9:4:405–427 (2004) A group of Garibaldini, headed by the Greek poet Lorentzos Mavilis, fought also with the Greek side during the Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans, Balkan states in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan states of Kingdom of Greece (Glücksburg), Greece, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Montenegro, M ...

.

Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. In 1826, the Greeks were assisted ...

( National Historical Museum). The first two columns from the left are the names of those having died.

File:Dupre-Salona-1821.jpg, Louis Dupré's depiction of Greek irregulars hoisting the flag at Salona

Salona (, ) was an ancient city and the capital of the Roman province of Dalmatia and near to Split, in Croatia. It was one of the largest cities of the late Roman empire with 60,000 inhabitants. It was the last residence of the final western ...

File:Panagiotis Kefalas by Hess.jpg, ''Panagiotis Kephalas plants the flag of liberty upon the walls of Tripolizza'' ( Siege of Tripolitsa)" by Peter von Hess

File:Pushkin Alexander, 1826 by Vivien.jpg, Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin () was a Russian poet, playwright, and novelist of the Romantic era.Basker, Michael. Pushkin and Romanticism. In Ferber, Michael, ed., ''A Companion to European Romanticism''. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005. He is consid ...

File:Athens, George Gordon Byron 02.JPG, A statue of Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824) was an English poet. He is one of the major figures of the Romantic movement, and is regarded as being among the greatest poets of the United Kingdom. Among his best-kno ...

in Athens

File:Santorre di Santarosa.jpg, Annibale Santorre di Rossi de Pomarolo, Count of Santarosa

Santorre Annibale De Rossi di Pomerolo, Count of Santa Rosa (born 18 November 1783, Saviglianodied 8 May 1825, Sphacteria) was an Italian insurgent and leader in Italy's revival ('' Risorgimento'').

250px, left, Statue of Santarosa in Saviglia ...

File:Karl von Normann-Ehrenfels.jpg, Karl von Normann-Ehrenfels

File:Portrait de Charles Nicolas Fabvier.jpg, Charles Nicolas Fabvier

File:Rosaroll, Giuseppe.jpg, Giuseppe Rosaroll

File:Ricciotti Garibaldi.jpg, Ricciotti Garibaldi

Ricciotti Garibaldi (24 February 1847 – 17 July 1924) was an Italian soldier, the fourth son of Giuseppe Garibaldi and Anita Garibaldi.

Biography

Born in Montevideo, he was named in honour of who had been executed during the failed expeditio ...

File:Peppino Garibaldi.jpg, Giuseppe Garibaldi II

File:Henry Morgenthau crop.jpg, Henry Morgenthau Sr.

File:David Lloyd George.jpg, David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

Notable 20th- and 21st-century philhellenes

*Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

, a German-born theoretical physicist widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest physicists of all time

* Stephen Fry

Sir Stephen John Fry (born 24 August 1957) is an English actor, broadcaster, comedian, director, narrator and writer. He came to prominence as a member of the comic act Fry and Laurie alongside Hugh Laurie, with the two starring in ''A Bit of ...

, English actor and writer

* Giuseppe Garibaldi II, Italian soldier and revolutionary, grandson of Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as (). In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as () or (). 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, revolutionary and republican. H ...

and son of Ricciotti Garibaldi

* Ricciotti Garibaldi

Ricciotti Garibaldi (24 February 1847 – 17 July 1924) was an Italian soldier, the fourth son of Giuseppe Garibaldi and Anita Garibaldi.

Biography

Born in Montevideo, he was named in honour of who had been executed during the failed expeditio ...

, Italian soldier, son of Giuseppe Garibaldi

* David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister Advice (constitutional law), advises the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign on the exercise of much of the Royal prerogative ...

* Boris Johnson

Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson (born 19 June 1964) is a British politician and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 2019 to 2022. He wa ...

, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

* Dilys Powell

Elizabeth Dilys Powell (20 July 1901 – 3 June 1995) was a British film critic and travel writer who contributed to ''The Sunday Times'' for more than 50 years. Powell was known for her receptiveness to cultural change in the cinema and coin ...

, film critic, author of several books about Greece, and president of the Classical Association

The Classical Association (CA) is an educational organisation which aims to promote and widen access to the study of Classics, classical subjects in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1903, the Classical Association supports and advances classical ...

1966–1967

* Gough Whitlam

Edward Gough Whitlam (11 July 191621 October 2014) was the 21st prime minister of Australia, serving from December 1972 to November 1975. To date the longest-serving federal leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP), he was notable for being ...

, 21st Prime Minister of Australia

The prime minister of Australia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Australia. The prime minister is the chair of the Cabinet of Australia and thus the head of the Australian Government, federal executive government. Under the pr ...

* Christopher Hitchens

Christopher Eric Hitchens (13 April 1949 – 15 December 2011) was a British and American author and journalist. He was the author of Christopher Hitchens bibliography, 18 books on faith, religion, culture, politics, and literature. He was born ...

, British-American author and journalist

See also

*Laconophilia

Laconophilia is love or admiration of Sparta and of the Spartan culture or constitution. The term derives from Laconia, the part of the Peloponnesus where the Spartans lived.

Admirers of the Spartans typically praise their valour and success in ...

Notes

References

Paul Cartledge, Clare College Cambridge, "The Greeks and Anthropology"

in ''Classics Ireland'' 2 (Dublin 1995) *

Further reading

* Thomas Cahill, ''Sailing the Wine-Dark Sea: Why the Greeks Matter'' (Nan A. Talese, 2003) * Stella Ghervas, « Le philhellénisme d'inspiration conservatrice en Europe et en Russie », in ''Peuples, Etats et nations dans le Sud-Est de l'Europe'', (Bucarest, Ed. Anima, 2004.) * Stella Ghervas, « Le philhellénisme russe : union d'amour ou d'intérêt? », in ''Regards sur le philhellénisme'', (Genève, Mission permanente de la Grèce auprès de l'ONU, 2008). * Stella Ghervas, ''Réinventer la tradition. Alexandre Stourdza et l'Europe de la Sainte-Alliance'' (Paris, Honoré Champion, 2008). * Konstantinou, Evangelos''Graecomania and Philhellenism''

European History Online

European History Online (''Europäische Geschichte Online, EGO'') is an academic website that publishes articles on the history of Europe between the period of 1450 and 1950 according to the principle of open access.

Organisation

EGO is issued ...

, Mainz: Institute of European History

The Leibniz Institute of European History (IEG) in Mainz, Germany, is an independent, public research institute that carries out and promotes historical research on the foundations of Europe in the early and late Modern period. Though autonomous i ...

, 2010, retrieved: December 17, 2012.

* Emile Malakis, ''French travellers in Greece (1770–1820): An early phase of French Philhellenism''

* Suzanne L. Marchand, 1996. ''Down from Olympus : Archaeology and Philhellenism in Germany, 1750–1970''

* M. Byron Raizis, 1971. ''American poets and the Greek revolution, 1821–1828;: A study in Byronic philhellenism'' (Institute of Balkan Studies)

Terence J. B Spencer, 1973. ''Fair Greece! Sad relic: Literary philhellenism from Shakespeare to Byron''

* Caroline Winterer, 2002. ''The Culture of Classicism: Ancient Greece and Rome in American Intellectual Life, 1780–1910''. Johns Hopkins University Press.

External links

{{Cultural appreciation Admiration of foreign cultures Ancient Greece studies Greek nationalism Theories of aesthetics Politics of the Greek War of Independence